Abstract

Background

There is an ongoing controversy about women’s sexuality and the existence of different orgasms. The debate is tilted toward anatomical and physiological evidence, which often leaves subjective experiences out of the picture. The aim of the current mixed-methods study was to capture women’s accounts of their experiences of orgasmic states.

Methods

As part of a larger online survey, 513 women (M = 25.89 years, SD = 5.60) from a community sample filled in open-ended questions on their experience of different kinds of orgasms. Additionally, women rated semantic differentials with bipolar adjectives characterizing vaginal and clitoral orgasms. A sub-sample of n = 257 women (50%) had experienced both, vaginal and clitoral orgasms and rated both separately on the semantic differential.

Results

Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed significant differences in that clitoral orgasms were, amongst others, rated as sharper, easier, and more controllable, while vaginal orgasms were rated as wilder, deeper, more pulsating, and extending. In open-ended questions, women talked about various other orgasmic experiences, such as mixed clitoral/vaginal orgasms, whole body, cervical, anal, or mental orgasms. Some women were uncertain about their orgasmic experiences.

Conclusion

It is time to integrate anatomical, psychophysiological, and experiential data and conclude that either “all clitoral” or “clitoral and vaginal” falls short to do justice to the complexity of women’s orgasms. Understanding and defining these various types of orgasms and allowing for the apparent diversity to have its place in research and in social discourse is a task for future research and pleasure-positive sex education to increase pleasure literacy.

Keywords: Orgasm, women, semantic differential, mixed-methods, pleasure literacy

Introduction

For centuries up until this day, there is an ongoing controversy about women’s sexuality and the existence of different types of orgasms (Jannini et al., 2012).

First of all, experiencing any orgasm at all during partnered sex does not seem to be a given for women in heterosexual encounters. In a large US sample with adults, heterosexual women were the least likely to report they usually or always orgasmed when sexually intimate (65%) similar to bisexual women (66%). This is in contrast with orgasmic experiences during partnered sexual activities reported by lesbian women (86%), gay men (89%), or heterosexual men (95%) (Frederick et al., 2018). Thus, being more knowledgeable about women’s orgasms may provide a better starting point to close this “orgasm gap”.

If women do experience orgasmic pleasure, scientists disagree on whether these orgasmic experiences may be seen as distinct phenomena or not. There is a continuing debate to date whether all orgasms are related to the clitoris or whether orgasms unrelated to the clitoris exist. On the one hand, based on anatomical observations, some researchers argue that the clitoris and vagina could be seen as an anatomical and functional unit that is activated by vaginal penetration (Jannini et al., 2012; O’Connell et al., 2005). Moreover, ultrasound during coital activity of only one couple demonstrated that stimulation of the vagina was simultaneously a stimulation of the internal clitoral structures (Buisson et al., 2010).

However, when looking at functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), clitoral, vaginal, and cervical self-stimulation activated specific sensory cortical regions in the medial paracentral lobule suggesting that there may be the potential for experiencing different kinds of orgasms (Komisaruk et al., 2011).1 Additionally, the cervix is innervated by the vagus nerve which the clitoris is not (Komisaruk et al., 2004). Cervical stimulation itself may be a second intravaginal trigger of orgasm independent of clitoral stimulation (Pfaus et al., 2016). Adding to anatomical evidence, it becomes evident that women differentiate in their subjective experience of orgasms. In women’s more anecdotal self-reports, orgasms attained by clitoral stimulation have been described as localized (Jannini et al., 2012), sharp, bursting, electrical, short-lasting (Sayin, 2017), and superficial (Palmer, 2014). On the contrary, orgasms related to vaginal stimulation have been described as more diffuse (Clifford, 1978), longer-lasting (Sayin, 2017), deep (Butler, 1976; Palmer, 2014), throbbing, generally stronger (Mah & Binik, 2002) and more psychologically satisfying (Sayin, 2017). Beyond the discussion surrounding vaginal and clitoral orgasms, researchers need to keep in mind the existence of other types of orgasms, like nonsexual orgasms from dreams during sleep, breastfeeding, exercise, and even non-genital stimulation (Herbenick et al., 2018; Komisaruk & Whipple, 2011; Levin, 2015) or Tantric orgasms (Lousada & Angel, 2011). When dealing with women’s orgasms, women’s experiences of different qualities of orgasms are disregarded by some scientists as “anecdotal” (Mah & Binik, 2005, p. 187). Others demand to leave “artificial discussions on the unnecessary separation of the orgasmic focus, that is clitoral vs. vaginal” (O’Connell et al., 2005, p. 1194) behind.

The oversimplified reduction of orgasmic experiences being “all clitoral,” a view held by some researchers who likely intended to reduce the pressure on women with difficulties experiencing certain or any types of orgasm, has consequences that clinicians and researchers need to take into account. The power of definition should not be underestimated. Feminist critique posits that medical “experts” hold great power in defining sexual norms that shape women’s experiences (Cacchioni, 2007). We need to be aware that sexuality is socioculturally produced, and that the institutional level provides the framework for sexual experiences through the dissemination of scientific knowledge about sexual physiology and responsiveness, or clinical knowledge surrounding sexual function/disfunction, as well as through the sex education systems in place or the media more generally (Frith, 2013). More scholarly attention is needed to increase the evidence-based wealth of knowledge for experts to draw on.

It is therefore time to listen to and grant credibility to women’s accounts of their experiences of orgasmic pleasure, which are quite often neglected in the research on women’s sexuality. For instance, in a study on the erogenous zone in the vagina known as Gräfenberg-spot or area (G-spot/G-area), over 1800 women were asked whether they thought they had a G-area. Even though 56% self-reported having a G-area, the authors described the women’s subjective experience of having a G-area as a “secondary pseudo-phenomenon” (Burri et al., 2010, p. 1). Instead of dismissing these experiences, researchers should strive to uncover alternative explanations for such differences between women by incorporating women’s learning history regarding their own sexual perceptions.

For instance, Sexocorporel, a mode of sexual therapy, suggest that the ability to perceive sexual pleasure may be acquired through practice and somatic learning (Bischof, 2012). This sensory learning occurs at first during a woman’s self-discovery and optimally continues with a partner the woman can trust. This learning does not occur as naturally for girls as it does for boys, because the female genital organs, compared to the male genital organs, are more tucked away, hidden, and well protected inside the body. Thus, playful self-experimenting not only of the outer genital area but of the vagina and cervix are important in getting to know oneself and allow for the establishment of neurological representation in the somatosensory cortex (Nemati & Weitkamp, 2020). A lack of this sensory learning may potentially explain the lack of pleasurable experiences from vaginal touch or intercourse that some women describe. As Pfaus et al. state: “The erotic body map a woman possesses is not etched in stone, but rather is an ongoing process of experience, discovery, and construction” (2016, p. 13). The differences between and within women depend on the unique distribution of sensory nerves in the external glans of the clitoris, around the posterior clitoral complex and cervix, and the connection to the nerves that transmit those sensations into the spinal cord and/or directly to brain. Moreover, differences may be due to a woman’s relative experience with sensory stimulation of some or all of those regions being associated with orgasm (Pfaus et al., 2016) and also whether these experiences were pleasurable or traumatic. Thus, knowing one’s body and being able to tune into the awareness of bodily sensations and pleasurable experiences may be linked to the experience of various kinds of orgasmic states as well.

To conclude, it is time to turn to women themselves and ask them about their experiences and take these accounts seriously. From a feminist standpoint epistemology, we would like to include the devalued and disregarded voices of women themselves into the discourse (Harding, 1991). We adopted a phenomenological approach to focus on the subjective experience of women and acknowledge the enormous variability in individuals’ intimate and sexual experiences and their interpretations of these experiences (Frost et al., 2013).

Additionally, to quantifiably capture possible differences in experiences with clitoral and vaginal orgasms, we adapted the technique of the semantic differential (Osgood et al., 1957). The semantic differential was developed to assess and quantify the “meaning” of various concepts. The semantic differential provides study participants with a concept and a set of bipolar adjectival scales on which they have to rate the concept (Osgood et al., 1957).

We carried out a mixed-methods study and asked a community sample of women to rate the orgasms they experience on a semantic differential for various types of orgasms separately. Our research questions are the following: (1) Do women differentiate between different kinds of orgasms? (2) Are clitoral and vaginal orgasms characterized differently on a semantic differential? (3) What kind of orgasmic experiences do women describe? (4) Are clitoral, vaginal, or other types of orgasms described differently and distinctly?

Methods

We conducted a mixed-method study using an online survey to collect data from adult women from the general population. Following a convergent design of multi-method analysis, a comparison approach (“joint display”) was chosen to integrate quantitative and qualitative findings into the discussion (Johnson & Christensen, 2017; Kuckartz, 2019). The quantitative and qualitative results were studied first independently with later integration regarding similarities and differences (Kuckartz, 2019). The findings presented here were part of a larger study.

Sample

The convenience sample consisted of 513 women. The sample was somewhat diverse but primarily consisted of educated, young, heterosexual women, who were mostly in a monogamous relationship and never married. See Table 1 for sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N = 513).

| Variable | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age |

25.89 (5.60) |

18–56 |

| |

n

|

% |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 434 | 85 |

| Bisexual | 53 | 10 |

| Pansexual | 11 | 2 |

| Lesbian | 8 | 2 |

| Other | 7 | 1 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Monogamous relationship | 355 | 69 |

| Single | 131 | 26 |

| Open relationship | 19 | 4 |

| Polyamorous relationship | 4 | 1 |

| Other | 4 | 1 |

| Children | ||

| Yes | 46 | 9 |

| No | 462 | 91 |

| Sexual assault experience | ||

| Yes | 104 | 20 |

| No | 395 | 77 |

| No answer | 14 | 3 |

| Education | ||

| High school | 199 | 39 |

| Higher education | 76 | 15 |

| University/technical college | 235 | 46 |

| Other | 3 | 1 |

| Nationality | ||

| Swiss | 441 | 86 |

| German | 25 | 5 |

| Austrian | 15 | 3 |

| Other | 32 | 6 |

| Practicing religion | ||

| Not religious | 273 | 53 |

| A little religious | 154 | 30 |

| Moderately religious | 60 | 12 |

| Very religious | 18 | 4 |

| Highly religious | 8 | 2 |

Procedure

We collected data via an anonymous online survey in January 2021 that was advertised on social media (Instagram and Facebook) and distributed through mailing lists of the Universities of Zurich and Bern. When clicking on the link, participants received information about the study and gave their informed consent before starting the survey. Inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 18 years, sufficient knowledge of German, born with unambiguous female sexual genitalia, and having been sexually active in the past three months (masturbation and/or sexual intercourse). The survey took ∼35 min to complete. Of 844 participants who began the survey, 514 participants completed it (62%). This completion rate was comparable with response rates from other studies on sexual behavior (Fenton et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2016). We excluded one participant who did not meet the inclusion criteria (self-identified as male gender), resulting in a total sample of 513 women. Participants received university credits, if eligible, or were entered into a prize draw for a book voucher. The Institutional Ethical Review Board of the University of Zurich approved the procedure of the present study.

Measures

Participants completed items related to their sociodemographic background, medical history, questions on orgasm experience, semantic differential items to assess the quality of the different orgasms, as well as questionnaires on their sexual function, sexual self-esteem, and mental health symptoms. Participants also answered qualitative open-format questions on orgasm experience and their ability to differentiate between various orgasmic experiences. To avoid misunderstandings and provide a common ground, we showed participants schematic drawings of women’s genital anatomy, before asking anatomy related questions. Since colloquial differentiation of orgasms is mostly “clitoral,” “vaginal,” “cervical,” and “anal,” we followed this nomenclature in the study and added explicit definitions of “clitoral” and “vaginal” as vaginally activated orgasms (Jannini et al., 2012). We report only measures here that were relevant to the current research questions.

Semantic differential

After indicating which type of orgasm participants feel they had previously experienced in their life (vaginal, clitoral, or hard to differentiate), they filled in the semantic differential for each type of orgasm they indicated. The semantic differential was created based on an extensive list of adjectives related to female orgasm experience compiled from existing literature (Arcos-Romero et al., 2018, 2019; Arcos-Romero & Sierra, 2019; Levin, 2004; Mah & Binik, 2002, 2005; Palmer, 2014; Rowland et al., 2020). A total of 297 adjectives were extracted, checked for doubles, and translated into German. Two hundred and sixty-nine phrases were excluded due to a lack of suitability or content overlap with other adjectives. In the next step, adjectives were paired with a polar opposite. Based on this list, twenty-eight adjective pairs were selected based on differentiation and non-repetition. In the survey, participants were asked to rate on a five-point Likert scale, which adjective best described the orgasm they experienced (for instance, “paralyzing - - - - - activating”).

Data analysis

To test differences in women’s ratings on the semantic differential, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for dependent samples was carried out for each item separately and for only those women that reported they had previously experienced both a “clitoral” and a “vaginal” orgasm. We refrained from using repeated measures analyses of variance because of the ordinal scale nature of the items.

For the qualitative analysis, we applied Qualitative Content Analysis (Mayring, 2014) with an explorative/inductive and a descriptive/deductive focus: Inductive categories were formulated by the first author working with the material and guided by the research questions of what types of orgasms women described, how they described these experiences, preferred stimulation to orgasm, and context to orgasm. The content-analytical units were defined as clear semantic elements in the text. Because of the large quantity of material, we relied on inductive category assignment which means that only those parts of the material relevant to a specific research question are considered (Mayring, 2014). The deductively formulated category system consisted of a case by case rating on whether the particular woman (a) experienced orgasm at all, (b) differentiated herself between different kinds of orgasms, (c) felt unsure about her differentiation, or (d) did not differentiate between different kinds of orgasms in her accounts. To be rated as differentiating between at least two kinds of orgasmic experiences, the accounts needed to contain explications of qualitative differences of the orgasmic experiences. Merely mentioning differences in terms of intensity did not suffice for this category to be selected. When coding data for the question of different types of orgasms, we only coded those phrases, for which women explicitly named a type of orgasm (for instance “nipple orgasm”). In some instances, women described a form of orgasm without explicitly naming it. For consistency and stringency, those phrases were not coded, even if in some cases the coders might have been able to infer what the women were talking about.

As suggested (Mayring, 2014), we revised the coding guideline and rules after 235 cases (46%), at which point no new categories were found. The final coding guideline was then applied in full for the complete material in the final step. The coding guideline comprised anchor examples and descriptions for each code. Coding was carried out by the first author and a postgraduate student. The first author created the coding guideline and subsequently trained the postgraduate student. They coded three cases together, and after further practice, they coded three cases independently and subsequently discussed their dis-/agreements. Almost half of the cases were coded by both coders (n = 235, 46%). For these, interrater reliability was very good with κn = .97 (Brennan & Prediger, 1981; Kuckartz, 2019).

Results

Differentiation of orgasm types

The question, whether women differentiate between orgasm types, was assessed in two ways: through direct reports as well as the qualitative analyses of the individual accounts of orgasmic experiences. When asked directly, n = 11 women (2%) reported never having an orgasm. Of those with orgasm experience, one-fifth of women (n = 99) said they were not able to differentiate between different orgasmic experiences. A minority said they were able to differentiate 1–25% of orgasms (n = 39, 8%), n = 62 women (12%) differentiated 26–50% of the times, n = 79 women (15%) differentiated 51–75% of the times. Two hundred and twenty-three women (44%) stated they were able to differentiate their orgasmic experiences 76–100% of the time.

Based on the deductive coding of the qualitative accounts, a slightly different picture emerged: in 59% of women’s accounts no clear differentiation between different kinds of orgasmic experiences was visible (n = 295 of 498 women who answered the open-ended questions on orgasm or spoke about their lack of orgasm experience in the comments section). Around a third of women (34%, n = 167) differentiated at least between two types of orgasmic experiences. In the accounts of about 4% of women (n = 20), some degree of uncertainty regarding orgasm differentiation was noticeable. These women seemed unsure whether they were able to experience different kinds of orgasms. In the open-ended questions, only four women (<1%) reported either never experiencing an orgasm or being unsure whether their experience could be defined as a “proper” orgasm (participant No. 210, aged 19, self-identified heterosexual). These women shared this information in the open comment section. Several accounts (2%, n = 12) were not classifiable primarily due to their exceedingly short descriptions that were difficult to understand, which made them impossible to code.

Women were also asked which orgasms they had difficulties discriminating. Here, some women (n = 11) said they did not have any difficulties discriminating between different kinds of orgasms (“I think they are all very easy to distinguish.” No. 741, aged 29, pansexual). Other women (n = 84) reported feelings of uncertainty in terms of their ability to differentiate mostly between clitoral and vaginal but also between vaginal and anal, or vaginal and cervical orgasms (“I suspect [the best orgasm] is the cervical, but I’m not sure if I’m confusing it with the vaginal. The cervical one is much deeper, almost in the uterus. The vaginal one is about a finger’s width inside the vagina.” No. 611, aged 24, heterosexual). Quite often, women reported that simultaneous clitoral and vaginal stimulation led to orgasmic experiences that seemed hard to differentiate. Some questioned their experiences, doubting whether they experienced another kind of orgasm other than what was familiar to them: “I think I’ve only experienced a clitoral orgasm so far. Once I had a very intense one and at first, I was unsure if it might have been a vaginal orgasm as well. But in retrospect, I think it wasn’t” (No. 664, aged 25, heterosexual). This uncertainty seemed to be fueled by an experiential overlap of simultaneous stimulation of different body parts, a lack of trust in their own experiences, but also preconceptions adopted from social discourse, as one woman described: “I think I know that there are no different orgasms. A colleague told me this who does a lot of research and seems to know a lot about the subject, so I believe her” (No. 629, aged 24, heterosexual). This uncertainty was also visible when women talked about their experiences of whole-body orgasms. These accounts were quite regularly paired with some form of doubt: “It’s quite possible that I’ve had a full body orgasm before but didn’t effectively register it as such” (No. 727, aged 24, heterosexual).

It is worth mentioning here, that some women openly shared that they were not sure whether their experience would count as an orgasm: “I’m not quite sure, I do reach a certain climax, but if this is that orgasm that everyone thinks is so fantastic, then I’m a bit confused as to why people think sex is so great” (No. 232, aged 22, asexual).

Semantic differential between reported experiences of clitoral and vaginal orgasms

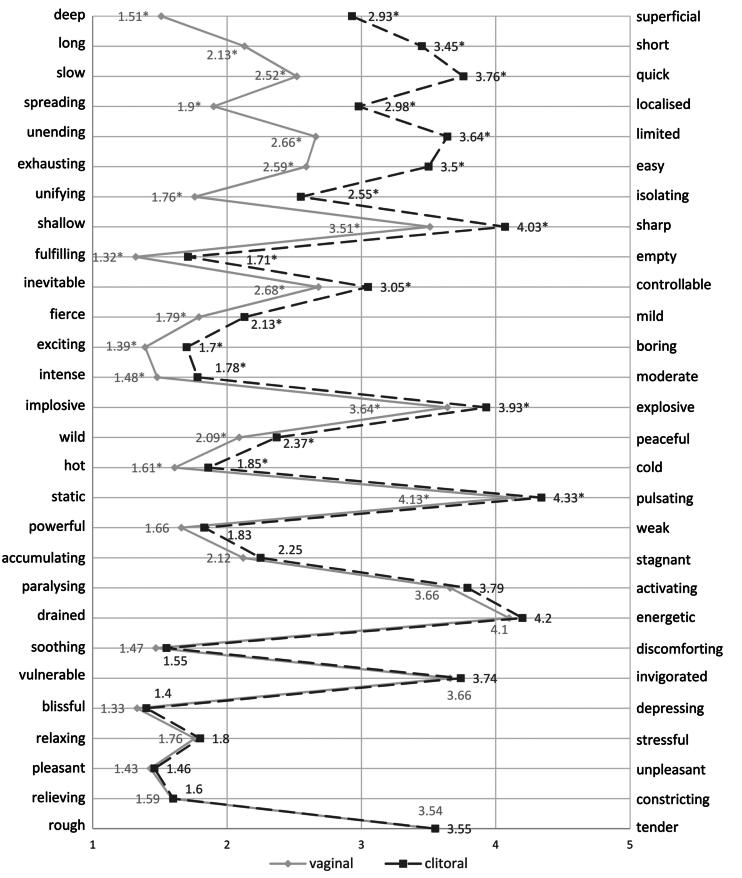

A sub-sample of n = 257 women (50%) experienced both vaginal and clitoral orgasms, who subsequently rated each experience on the semantic differential (see Figure 1). A Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed significant differences in 17 of the 28 adjectives (61%). While clitoral orgasms were rated as more superficial, easier, and more controllable, vaginal orgasms were described as deeper, longer, more unifying, and exhausting. No differences between orgasms were visible in terms of the experience being (amongst others) pleasant, powerful, blissful, soothing, as well as energetic.

Figure 1.

Semantic differential for experiences of clitoral and vaginal orgasms (mean values). Note. n = 257; *p ≤ .05.

Kinds of orgasmic experiences and their different qualities

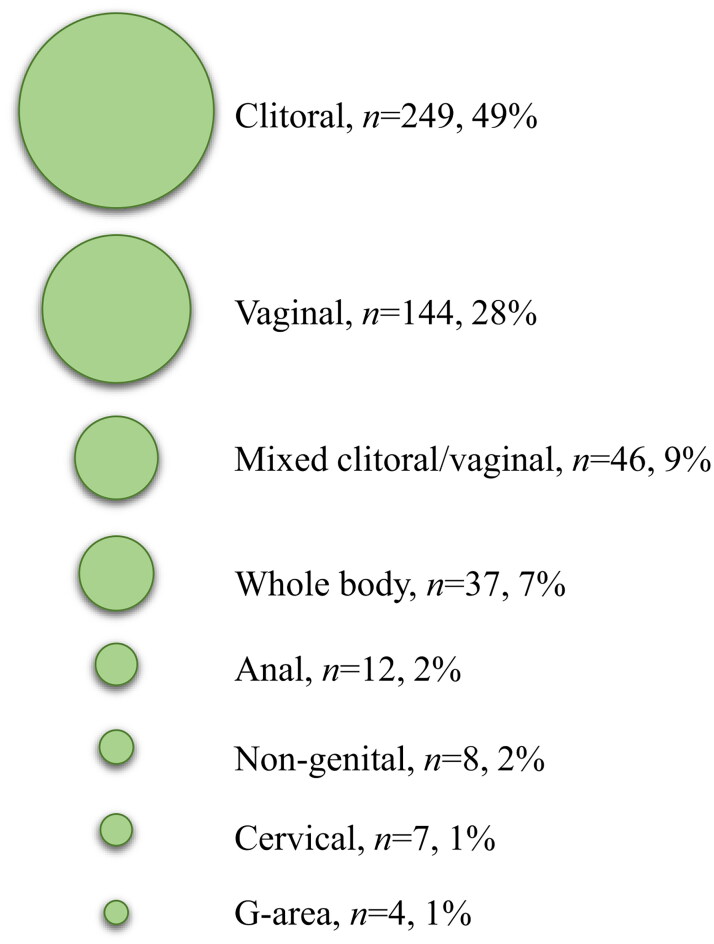

Overall, women described a variety of orgasmic experiences quite often focusing on the area of stimulation or sensual experience as the defining characteristic of the orgasm classification. See Figure 2 for an overview of the frequencies of different orgasmic experiences. Common across reported orgasmic experiences were intense feelings of ecstasy, happiness, relaxation, liberation, or that it felt like an explosion. On a physical level, women felt pulsations, tingling, contractions, and waves spreading across the whole body, as well as warmth and tension. Interestingly, even though there was this common ground for orgasmic experiences, some descriptors coincided more with certain orgasmic experiences than others, which hints at potential distinct experiences.

Figure 2.

Overview of frequencies of different orgasmic experiences mentioned by participants.

Clitoral orgasms

The most prevalent orgasmic experiences were the clitoral orgasms (n = 249). Even though the clitoral orgasmic experiences were described as pleasurable, oftentimes the accounts of clitoral orgasms were downgraded, as if clitoral orgasms were lacking or not as special. Some disappointment was identified in the accounts of some women. For example, one woman said: “[I] only know the clitoral orgasm” (No. 557, aged 25, heterosexual), another referred to it as a “lack of an alternative” (No. 561, aged 30, heterosexual). More positively, the clitoral orgasm was labeled as a reliable companion, and viewed as easier to reach and more controllable than other kinds of orgasms: “The clitoral orgasm is the most pleasurable for me because I know what I like and how I like it, so I’m more likely to orgasm and have a sense of achievement” (No. 733, aged 26, heterosexual).

Clitoral orgasms were described as explosive, coming in waves, and leading to relaxation. One woman compared the feeling with sneezing or being pushed over a cliff: “A clitoral orgasm feels tingly, like before a sneeze, just pleasant, like being pushed over a cliff and not being able to do anything about it. Very relaxing afterward and yet spreading out in waves” (No. 594, aged 27, heterosexual). The degree of intensity varied, for some clitoral orgasms were overwhelming experiences, for others, they felt more shallow and shorter when compared to vaginal orgasms. For instance, “Clitoral orgasm feels like heat to me. At first only in the intimate area and then in the whole body. The feeling is very short and is not always there. Sometimes it is only in the intimate area and not very strong. It feels like tension and from one moment to the next it goes away and it’s over” (No. 421, aged 25, heterosexual). Still, no general preference for any type of orgasm was identified. Some women explicitly stated they preferred clitoral orgasms over vaginal orgasms while others emphasized the opposite.

One woman stressed an important point in the open comments section at the end of the survey. She felt the semantic differential did not capture her experience well, writing “this part [of the survey] does not represent my experience well because my clitoral orgasms are also very different. Short, long, fierce, weak, energizing, tiring, etc.” (No. 794, aged 29, heterosexual). This diversity was noticeable in other accounts as well. One woman described her clitoral orgasms ranging “from very short and almost disappointing to long and all-consuming” (No. 550, aged 22, bisexual).

When dealing with the complexity of orgasmic experiences the reduction to “orgasm x is felt like this,” is tempting but artificial. This points not only to the uniqueness of individual experiences but also to intraindividual heterogeneity.

Mixed clitoral and vaginal orgasms

Several women (n = 46) said the simultaneous stimulation of clitoris and vagina led to more intense feelings when they orgasmed than clitoral stimulation alone. Here, it seemed not so much a different quality but rather a different degree of intensity: “I feel pure clitoral orgasms as rather short and superficial waves. Clitoral and vaginal combined orgasms feel much more intense, longer and ‘fuller’ for me. More fulfilling somehow” (No. 745, aged 38, heterosexual). In some cases, orgasms appeared to occur that may be termed as “whole-body orgasms.” For instance, one woman described her experience of clitoral, vaginal, and mixed orgasms: “Clitoral feels superficial. So sharp. Vaginal runs deeper through me and I would basically call it more beautiful than the external ones. But the best is the combination of both. It’s a huge explosion and lasts the longest. My whole body orgasms. Hard to describe” (No. 814, aged 34, heterosexual). Another woman experienced squirting during the mixed orgasm: “Enormously overwhelming wave of lust, shaking, shuddering, in 1/10 cases squirting” (No. 564, aged 25, heterosexual). Interestingly, some women emphasized that the mixed orgasm was the only type of orgasm they experienced.

Vaginal orgasms

About a third of the women described experiencing vaginal orgasms (n = 144). Vaginal orgasms were quite often compared with clitoral orgasms and described as longer in duration, more intense, deeper, less local, less controllable but more complete. Also, vaginal orgasms were often described as more difficult to reach, needing the right position, the right (manual) stimulation, and not being stuck in the mind too much. Moreover, taking time for stimulation, long “foreplay,” and feeling close to the partner were mentioned. Additionally, vaginal orgasms seemed to be related to more feelings of connectedness with the partner and for some an increased level of emotional involvement. One woman, for instance, mentioned feelings of vulnerability after the vaginal orgasm: “A tornado, completely detached and total tension, ending in pleasant emptiness and vulnerability” (No. 568, aged 29, heterosexual).

The relative effort and scarcity of vaginal orgasms seemed to make them more valuable for some women: “More difficult to achieve, but all the more beautiful to experience. Feels longer and more intense than the clitoral orgasm. The warmth and the feeling of happiness comes from deep inside” (No. 185, aged 37, heterosexual). Again, there was variety in how women described the vaginal orgasm. For some it was “fireworks” (No. 196, aged 19, heterosexual), for others, vaginal orgasm was “not that spectacular” (No. 247, aged 20, heterosexual) or “like you have to pee” (No. 249, aged 21, bisexual).

Similar to the clitoral orgasms, there seemed to be intraindividual variance in the experience of vaginal orgasms, as well. One woman differentiated vaginal orgasms in terms of the intensity using the metaphor of flight altitudes: “Within the vaginal, I distinguish between heights of flying. There are short and flat, high but short and concise, but also extended medium-high or really great, distinct long high flights “(No. 804, aged 35, heterosexual).

G-area orgasms

A small number of women (n = 4) reported orgasms that they described as originating from their “G-spot”. One woman explained: “Vaginal/G-spot: During penetrative sex with a penis or toy, triggered by penetration, even better with vibration, warm rising sensation from the lower abdomen, rising tension from the pelvis, possibly combined with squirting” (No. 52, aged 24, bisexual). Some women reported squirting alongside their G-area orgasms.

Cervical orgasms

Only n = 7 women mentioned the experience of cervical orgasms. One woman described it as “much deeper inside, almost in the uterus” (No. 611, aged 24, heterosexual). Unfortunately, descriptions were not as extensive as they were for other orgasms. Only one woman elaborated on her experience, describing it as conquering a hill: “Orgasm was never too strong, not too intense, quite calm. Found it pleasurable, relaxing […]. I felt it as if my body sensation went up a hill, and then very quietly crossing it and bringing me back to bed. Slope was somehow controlled” (No. 575, aged 29, heterosexual).

Anal orgasms

Like the cervical orgasm, only few women reported experiencing anal orgasms (n = 12). Those who elaborated more on this experience described the anal orgasm as lasting “an incredibly long time” (No. 108, aged 21, bisexual) being more stretched out: “a little like a long but by no means high wave” (No. 550, aged 22, bisexual). The women emphasized the intensity and a feeling of surrender, as one woman said: “I find anal orgasms to be the strongest and lasting the longest […] The high flying/floating feeling is not there, but a deep and very intimate feeling of letting go/relaxation is” (No. 606, aged 27, heterosexual).

Whole-body orgasms

Thirty-seven women reported experiencing whole-body orgasms. Quite often they uttered a degree of uncertainty on whether their experiences met the criteria to count as “full” whole-body orgasms. At the same time, in these descriptions, women used the most superlatives and described whole-body orgasms as “the most fulfilling, in total relaxation and surrender” (No. 351, aged 25, heterosexual). Also, here women mentioned out of body experiences, like for instance: “I saw stars, my whole body went completely numb, my brain completely relaxed, and I no longer knew where I was, who I was, or why” (No. 575, aged 29, heterosexual). Additionally, whole-body orgasms were described as energizing: “You feel it everywhere and it gives you so much energy. I experience it exclusively during intense and prolonged sex” (No. 191, aged 20, heterosexual). As seen in the last quote, the journey toward a whole-body orgasm appeared to need time and intensive “foreplay.” Additionally, the women mentioned a certain degree of feeling close and connected to the partner as a prerequisite to be able to surrender to the experience: “Whole-body orgasms I only encounter when I have a certain emotional bond with my partner” (No. 247, aged 20, heterosexual). Compared to other orgasms, women mentioned intense positive feelings alongside the orgasmic experience: “makes me happy and in love” (No. 677, aged 29, heterosexual).

Other non-genital orgasms

Eight women reported orgasmic experiences from non-genital area stimulation alone. To illustrate this, one woman said: “I have had orgasms by stimulating my neck, earlobe or breasts. It was incredible” (No. 195, aged 27, heterosexual). One woman wrote about a sexual experience while consuming MDMA (3,4-Methyl-enedioxy-methamphetamine), a psychoactive drug, where she orgasmed multiple times without any physical stimulation at all (No. 482, aged 37, heterosexual). A few women experienced orgasms without any stimulation (or substance use) at all. Some women (n = 6) reported experiencing orgasms during their sleep as part of a dream without any prior physical stimulation: “Lower body slight trembling, feeling of being tipsy and disorientation when waking up, starting the day with a smile, as if wrapped in cotton candy” (No. 587, aged 29, pansexual). Another woman described her “sleep orgasms” as “by far the strongest of all” (No. 367, aged 25, bisexual).

Further findings

In addition to the different orgasmic experiences outlined above, some women chose their own labels for their experiences “I distinguish for myself between a deeper and a more superficial orgasm” (No. 666, aged 30, heterosexual) or “I distinguish between small and big orgasms” (No. 707, aged 25, heterosexual). Whether those differentiations refer to different kinds of clitoral complex orgasms or for example cervical orgasms remain open to for interpretation.

Beyond the differentiation of anatomical types of orgasms, some women stressed the varying experiences regarding masturbation and partnered sex. For instance, “I only experience [vaginal orgasms] in constellations of two (with a partner)” (No. 399, aged 27, heterosexual). Interestingly, women also explicitly referred to types of orgasms they did not experience but would want to experience, with a sense of regret (“Unfortunately, I only know clitoral orgasms, so I would be curious to know what a vaginal orgasm feels like” No. 763, aged 19, heterosexual) or with curiosity (“I would like to give them all a try” No. 773, aged 22, heterosexual).

It is worth noting that some women emphasized that they enjoyed sex regardless of whether they experienced an orgasm: “Orgasm is more the icing on the cake. The best orgasm is not the vaginal or clitoral or full body or anything else but the best orgasm is when the sex before was already a good mix of tenderness and lust and power. When the chemistry is right, you have fun, you feel your body strongly and you can share these feelings with your partner through body language” (No. 142, aged 24, heterosexual). To conclude, the notion of pleasure and joy was visible in many accounts of orgasmic experiences. One woman stressed the pleasure and joy sexual activities brought to her life, not preferring one orgasmic experience over the other: “I like all forms. Each type has its charm” (No. 52, aged 24, bisexual).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to capture women’s accounts of their experiences of orgasmic pleasure. Using mixed-methods, we asked a community sample of women to describe their orgasmic experiences and subsequently rate them on a semantic differential.

A major finding of the present study was the considerable variability in women’s ability to experience various types of orgasms and their ability to differentiate between them. This large variety points to the uniqueness of women’s anatomical features and/or learning histories (Bischof, 2012; Nemati & Weitkamp, 2020; Pfaus et al., 2016). Interestingly, the mode of data collection led to different answers in terms of the reported ability to differentiate between different kinds of orgasms. More women reported they were able to differentiate at least some of the time when asked in a closed question format, compared with the answers the women gave in the open question format. Our qualitative analysis may have been more conservative because we did not ask for different types of orgasms specifically but left the description and naming of the orgasmic experiences deliberately up to the women. This may not have covered all experiences spontaneously or in detail. In future research qualitative questions could be phrased more specifically focusing on the ability to differentiate.

Mirroring findings from earlier studies the semantic differential of those women who differentiated between clitoral and vaginal orgasms, show that these types of orgasms are qualitatively different experiences in over half of the presented adjective pairs (Clifford, 1978; Jannini et al., 2012; Mah & Binik, 2002; Sayin, 2017). While there seem to be distinct differences an overlap between experiential qualities was also identified. Not surprisingly, both kinds of orgasmic states were experienced as pleasant and blissful, but also as powerful. A certain degree of experiential overlap is to be expected considering the general notion that orgasmic experiences are at least in some form positive or ecstatic. This pattern of differences and overlaps fits well with the ongoing discussion in the field neither proving nor disproving either side of the “all clitoral” vs. “clitoral and vaginal” debate. More comprehensive and integrating theories are needed to do justice to the various orgasmic experiences women describe, or to better include those women who are able to differentiate and those who cannot.

To complement this quantitative analysis, the qualitative analyses provided more detail on the quality of different orgasmic experiences. Women described various kinds of orgasmic experiences besides a clitoral orgasm. For some descriptions, the distinction between clitoral complex orgasms seemed quite clear, for instance, whole body, cervical, anal, or nipple orgasm which have been described in the literature as well (Komisaruk & Whipple, 2011). Other descriptions might fit into the picture of clitoral complex orgasms, for instance, when women referred to mixed clitoral/vaginal orgasms, which are discussed in more detail below.

In terms of the quality of the experiences, some distinct patterns became visible. With vaginal and cervical orgasms, women reported deeper emotional reactions when compared to clitoral orgasms. Different levels of connectedness and taking time with the partner permeated the accounts, whereby vaginal, cervical, and whole-body orgasms were described in this way more than clitoral orgasms. Clitoral orgasms seemed to be reliable sources of quick stress relief independent from a partner (for instance, through masturbation).

Even though certain characteristics appeared to be related more to certain types of orgasms (e.g., vaginal orgasms were rated as deeper and longer), in quite a few cases, it was not possible to derive the type of orgasm based on the description alone (for instance, “fireworks”, “like an explosion” would show up in descriptions of vaginal or clitoral orgasms). Furthermore, there was great variability in intensity and quality within one type of orgasm. Clitoral orgasms were described ranging from short and superficial to intense out of body experiences. This lack of clear-cut boundaries poses a challenge to reductionist simplifications of orgasmic experiences and must be addressed in future research.

Besides some clearer distinctions, at the same time, an overlap between descriptions of types of orgasms was visible. On the one hand, descriptions of vaginal and clitoral orgasms were quite similar at times, on the other hand, women often referred to mixed orgasms implicitly referring to the locality of stimulation; quite often this meant an orgasm elicited from simultaneous clitoral and vaginal stimulation. Such mixed orgasmic experiences were described as more intense than clitoral stimulation alone. Considering these descriptions in isolation, they seem to fit well with the hypothesis that the clitoris and vagina form a functional unit (Jannini et al., 2012; O’Connell et al., 2005). Thus, the clitoral complex may be relevant for a considerable number of orgasmic experiences in women through internal and external genital stimulation.

Nevertheless, some orgasmic experiences clearly occurred without clitoral involvement like cervical orgasms, which are linked to vagal nerve stimulation (Komisaruk et al., 2004). Even though only few women reported cervical orgasms in this sample, the “cervix is an erotogenic organ and should be respected as such” (Goldstein & Komisaruk, 2020, p. 1). Whole body orgasmic states were also described. These have not yet received the deserved scholarly attention beyond anecdotal or conceptual descriptions, for instance by Lousada and Angel (2011) linking these experiences back to Daoist and Tantric sexual practices. Furthermore, women reported anoreceptive orgasmic experiences. To date, there is little research on women’s anal orgasms. In a mixed methods study on heterosexual anoreceptive intercourse, some women reported that they gained pleasure from this practice similar to the descriptions in our study (“Anal pleasure is something I feel in my whole body, while vaginal pleasure is more localized,” p. 1059; Štulhofer & Ajduković, 2013). Unfortunately, the authors asked about pleasure but not about orgasmic experiences (Štulhofer & Ajduković, 2013). Other orgasmic experiences beyond the clitoral complex were described by some of the study participants, like nipple orgasms, orgasms from dreams. Research into these experiences is scarce beyond anecdotal descriptions (Herbenick et al., 2018; Levin, 2015) and have been compiled by Komisaruk and Whipple (2011). Even though these are experienced only by a minority of women (and potentially men), systematic investigations into these fascinating human phenomena are overdue. To quote Komisaruk and Whipple: “…just as pain is not restricted to any one part of the body, neither is pleasure” (2011, p. 368). To summarize, from the women’s accounts it becomes clear that the current reductionism referring to orgasms as “all clitoral” falls short of doing justice to the diversity of reported experiences. Future research funding and efforts are needed to put more emphases on the uniqueness and variety of women’s experiences, their associated individual learning histories, and neurophysiological features.

Some women reported “squirting” or “ejaculating” as a part of their orgasmic experiences. Recently, squirting and female ejaculation have been distinguished as two distinct events (Pastor & Chmel, 2022). Squirting seems to consist of a larger amount of water-like fluid expelled from the urethra. Whereas, female ejaculation is described as a small amount of thicker, milky fluid originating from the prostatic glands. However, in our study, the women did not make this distinction. Based on the content of their accounts (“Incredibly great, but it makes a huge mess.” No. 775, aged 38, bisexual), it can be assumed that the women referred to what is now termed squirting.

Turning back to the results of the qualitative analyses, study participants used a mixture of implicit definitions of orgasms. For instance, orgasms by area of stimulation (stimulation of clitoris leading to orgasms that are termed as “clitoral”) or orgasm by body part where orgasmic sensations are experienced (“whole body”). The women themselves did not explicitly follow the clear distinction that, for instance, Jannini et al. (2012) introduced into the discourse with a focus on stimulation source as the defining characteristic of the type of orgasm. Thus, we refrained from using more specific terminology (like clitorally-stimulated orgasm) but followed the terms used by study participants.

In our sample, the number of women who have never experienced an orgasm was quite low when compared to other studies. A Danish study reported 6% of women meeting diagnostic criteria for anorgasmia (Christensen et al., 2011) and an earlier review, reported 16–25% of anorgasmia in Western samples (Lewis et al., 2010). It is important to keep in mind that anorgasmia is defined as a reduced intensity, delay, infrequency, or absence of orgasm for at least six months and be experienced as distressing (APA, 2013) which is quite different from never having experienced an orgasm. The low number of reported difficulties with orgasm in the current sample could also be due to a potential selection bias, where women refrained from participating in a study on their sexuality when they felt lacking in terms of orgasmic experiences. Nevertheless, it is highly relevant to map the large variety of women’s experiences including those who do not experience orgasms, who nonetheless may have satisfying sex lives anyway regardless.

A similar but distinct facet that needs more scientific and societal attention was the reported uncertainty regarding some women’s orgasmic experiences. For men’s orgasms, there seems to be a common albeit simplified understanding that the orgasm is marked by ejaculation. For women, this is not as straightforward without such overt signs. The experience of an orgasm of low intensity may not always be recognizable for women. Due to this, one might pose the question: “How do they come to know that what they are experiencing is an orgasm?” (Frith, 2013, p. 504). Women’s orgasms appear to have a cultural competency component, wherein women need some kind of knowledge that enables women to “know” what an orgasm is and to “recognize” it in themselves and others (Jackson & Scott, 2007, p. 107). This uncertainty surrounding orgasmic experiences appears to be quite prevalent. In a study on female undergraduate students in the 1970s, 25% of women were not sure whether they experienced an orgasm (Clifford, 1978). Likewise, in a more recent study, 25% of women selected “not sure” or “probably do not experience orgasm” when asked about their confidence and whether they had ever experienced an orgasm (Prause et al., 2016). The question remains, what would be beneficial for women to increase their certainty about having/not having an orgasm? Potential avenues to tackle this question could be, for instance, (1) to broaden the definition of orgasmic experiences, (2) to depict more diversity of orgasmic experiences in the media, (3) to encourage women to trust their subjective experiences and thereby empowering them to claim these experiences independent of any narrative of dysfunction, or (4) teach pleasure-positive sex education that encourages women to explore their bodies to increase body awareness (Schiftan, 2021). These claims may be subsumed with the term pleasure literacy, which forms a complementary facet to current definitions of sexual pleasure (Global Advisory Board for Sexual Health and Wellbeing, 2016). Pleasure literacy encompasses (a) being knowledgeable about potential ways of experiencing erotic pleasure and (b) having the body awareness to be able to feel what is pleasurable at the moment and what is not.

It is important to note, we are not interested in increasing pressure on women to feel lacking in yet another area if they are not experiencing vaginal, cervical, or other types of orgasms. Every woman is different, based on many different influencing factors. We do not want to create a hierarchy of orgasms. However, we would like to enrich the mostly physiological debate surrounding female orgasms, by elevating the voices of women by capturing their subjective experiences and by possibly educating them about the potential to experience sexual pleasure and satisfaction, thus increasing their pleasure literacy.

Thus, social sexual scripts around orgasm should be studied objectively for their impact on orgasm, in addition to a woman’s embodied genital and pleasurable self-knowledge. At the same time, social activists and clinicians need to broaden the availability of sexual scripts and ways for women to give meaning to their individual embodied experiences. Scholars need to be aware of how social definitions of orgasms have real consequences for women’s sexual experiences (Jackson & Scott, 2007). Furthermore, future research should focus on disentangling the interwoven cultural scripts and the embodied experience (Frost et al., 2013).

Limitations and strengths

The results of the current mixed-methods study are limited in important ways. The first limitation concerns the mode of data collection. Even though the online format might have helped in retrieving honest accounts less tainted by social desirability or impression management compared with face-to-face interviews, the fact that participants had to type their answers in manually may have hindered more detailed descriptions. However, compared with other open-ended questions of the questionnaire battery (for instance, on pornography consumption), answers on orgasm experience seemed more extensive and motivated. A second limitation is the use of a non-validated item list which we created for this study. Even though item compilation was based on published findings of qualities of orgasmic experiences, scale validity was not tested. Another limitation worth mentioning is the lack of generalizability. The sample was on average younger and more educated than the average population and based in the Western world leaving women beyond the WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) population out of the picture yet again (Henrich et al., 2010). Nonetheless, it may be assumed with some confidence that variances in terms of experiences of pleasure and orgasm are virtually certain (The Kinsey Institute, 2020). Additionally, participating in an online study on sexuality would have created a selection bias toward women interested in sexual topics and willing to share their experiences. Thus, we may underestimate women who have not experienced orgasmic states or who feel uncertain about their experiences.

This mixed-methods study has several notable strengths that highlight the added value of the results to the research field. We asked the women themselves about their experiences and included a large sample. The mixed-methods approach allowed for quantitative analyses in parallel with multifaceted qualitative accounts.

In the future, scholarly attention could focus in greater detail on which specific type of stimulation is more enjoyable and leads to orgasms more easily and whether these orgasmic experiences differed across demographic and relationship experiences similar to Kontula and Miettinen (2016).

To conclude, it is time to integrate anatomical, psychophysiological, and experiential data and conclude that an either “all clitoral” or “clitoral and vaginal” falls short to do justice to the complexity of women’s orgasms. Even though there are anatomical and experiential overlaps involved in genital orgasms, a considerable number of women experiences and differentiates between different qualities of orgasms termed as “clitoral” and “vaginal” as well as describing other non-genital orgasms. Understanding and defining these types of orgasms and allowing for the apparent diversity to have its place in research and in social discourse is a task for future research and pleasure-positive sex education to increase pleasure literacy.

Note

Interestingly, the women’s nipple self-stimulation activated their genital sensory region as well.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Author. [Google Scholar]

- Arcos-Romero, A. I., Granados, R., & Sierra, J. C. (2019). Relationship between orgasm experience and sexual excitation: Validation of the model of the subjective orgasm experience. International Journal of Impotence Research, 31(4), 282–287. 10.1038/s41443-018-0095-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcos-Romero, A. I., Moyano, N., & Sierra, J. C. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Orgasm Rating Scale in context of sexual relationship in a Spanish sample. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(5), 741–749. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcos-Romero, A. I., & Sierra, J. C. (2019). Factorial invariance, differential item functioning, and norms of the Orgasm Rating Scale. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 19(1), 57–66. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof, K. (2012). Sexocorporel in the promotion of sexual pleasure. In Kontula, O. (Ed.), Pleasure and Health (proceedings of the Nordic Association for Clinical Sexology) (p. 59–68). Finnish Association for Sexology. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, R. L., & Prediger, D. J. (1981). Coefficient kappa: Some uses, misuses, and alternatives. Educational and psychological measurement, 41(3), 687–699. [Google Scholar]

- Buisson, O., Foldes, P., Jannini, E., & Mimoun, S. (2010). Coitus as revealed by ultrasound in one volunteer couple. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(8), 2750–2754. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burri, A. V., Cherkas, L., & Spector, T. D. (2010). Genetic and environmental influences on self-reported G-spots in women: A twin study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(5), 1842–1852. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, C. A. (1976). New data about female sexual response. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 2(1), 40–46. 10.1080/00926237608407071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacchioni, T. (2007). Heterosexuality and “the labour of love”: A contribution to recent debates on female sexual dysfunction. Sexualities, 10(3), 299–320. 10.1177/1363460707078320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, B. S., Grønbaek, M., Osler, M., Pedersen, B. V., Graugaard, C., & Frisch, M. (2011). Sexual dysfunctions and difficulties in Denmark: Prevalence and associated sociodemographic factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(1), 121–132. 10.1007/s10508-010-9599-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, R. E. (1978). Subjective sexual experience in college women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 7(3), 183–197. 10.1007/BF01542378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, K. A., Johnson, A. M., McManus, S., & Erens, B. (2001). Measuring sexual behaviour: Methodological challenges in survey research. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 77(2), 84–92. 10.1136/sti.77.2.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, D. A., John, H. K. S., Garcia, J. R., & Lloyd, E. A. (2018). Differences in orgasm frequency among gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual men and women in a U.S. national sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 273–288. 10.1007/s10508-017-0939-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith, H. (2013). Labouring on orgasms: Embodiment, efficiency, entitlement and obligations in heterosex. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(4), 494–510. 10.1080/13691058.2013.767940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost, D. M., McClelland, S. I., Clark, J. B., & Boylan, E. A. (2013). Phenomenological research methods in the psychological study of sexuality. In Tolman D. L. & Diamond L. M. (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology, Vol. 1: Person-based approaches (Vol. 1, pp. 121–141). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14193-006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Global Advisory Board for Sexual Health and Wellbeing (2016). Working definition of sexual pleasure. http://www.gab-shw.org/our-work/working-definition-of-sexualpleasure/

- Goldstein, I., & Komisaruk, B. R. (2020). Is evidence based on what we know or do not know? Secrets of the cervix. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 8(1), 1–2. 10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. (1991). Whose science/whose knowledge? Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbenick, D., Barnhart, K., Beavers, K., & Fortenberry, D. (2018). Orgasm range and variability in humans: A content analysis. 30(2), 195–209. International Journal of Sexual Health. 10.1080/19317611.2018.1491920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S., & Scott, S. (2007). Faking like a woman? Towards an interpretive theorization of sexual pleasure. Body & Society, 13(2), 95–116. 10.1177/1357034X07077777 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jannini, E. A., Rubio-Casillas, A., Whipple, B., Buisson, O., Komisaruk, B. R., & Brody, S. (2012). Female orgasm(s): One, two, several. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(4), 956–965. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. B. (2017). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitatice, and mixed approaches (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Komisaruk, B. R., & Whipple, B. (2011). Non-genital orgasms. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 26, 356–372. 10.1080/14681994.2011.649252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Komisaruk, B. R., Whipple, B., Crawford, A., Liu, W. C., Kalnin, A., & Mosier, K. (2004). Brain activation during vaginocervical self-stimulation and orgasm in women with complete spinal cord injury: FMRI evidence of mediation by the vagus nerves. Brain Research, 1024(1–2), 77–88. 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komisaruk, B. R., Wise, N., Frangos, E., Liu, W. C., Allen, K., & Brody, S. (2011). Women’s clitoris, vagina, and cervix mapped on the sensory cortex: FMRI evidence. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8, 2822–2830. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02388.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontula, O., & Miettinen, A. (2016). Determinants of female sexual orgasms. Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology, 6(1), 31624. 10.3402/snp.v6.31624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. (2019). Qualitative text analysis: A systematic approach. In Compendium for early career researchers in mathematics education (pp. 181–197). Springer Nature Switzerland AG. 10.1007/978-3-030-15636-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D. M., Nazroo, J., O’Connor, D. B., Blake, M., & Pendleton, N. (2016). Sexual health and well-being among older men and women in England: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 133–144. 10.1007/s10508-014-0465-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, R. J. (2004). An orgasm is… who defines what an orgasm is? Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 19(1), 101–107. 10.1080/14681990410001641663 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, R. J. (2015). Recreation and procreation: A critical view of sex in the human female: Recreational and procreational sex. Clinical Anatomy, 28(3), 339–354. 10.1002/ca.22495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R. W., Fugl-Meyer, K. S., Corona, G., Hayes, R. D., Laumann, E. O., Moreira, E. D., Rellini, A. H., & Segraves, T. (2010). Definitions/epidemiology/risk factors for sexual dysfunction. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(4), 1598–1607. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lousada, M., & Angel, E. (2011). Tantric orgasm: Beyond Masters and Johnson. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 26, 389–402. 10.1080/14681994.2011.647903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mah, K., & Binik, Y. M. (2002). Do all orgasms feel alike? Evaluating a two‐dimensional model of the orgasm experience across gender and sexual context. The Journal of Sex Research, 39(2), 104–113. 10.1080/00224490209552129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah, K., & Binik, Y. M. (2005). Are orgasms in the mind or the body? Psychosocial versus physiological correlates of orgasmic pleasure and satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 31(3), 187–200. 10.1080/00926230590513401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis. Social Science Open Access Repository. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

- Nemati, A.-L. J., & Weitkamp, K. (2020). The female orgasmic state and the different dimensions of the female sexual experience: Lessons learned from expert interviews. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 1–24. 10.1080/14681994.2020.1789089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, H. E., Sanjeevan, K. V., & Hutson, J. M. (2005). Anatomy of the clitoris. Journal of Urology, 174(4 Part 1), 1189–1195. 10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957). The measurement of meaning. University of Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C. F. (2014). Comparing orgasm descriptions between the sexes. Eastern Kentucky University. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/303

- Pastor, Z., & Chmel, R. (2022). Female ejaculation and squirting as similar but completely different phenomena: A narrative review of current research. Clinical Anatomy, 35(5), 616–625. 10.1002/ca.23879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaus, J. G., Quintana, G. R., Mac Cionnaith, C., & Parada, M. (2016). The whole versus the sum of some of the parts: Toward resolving the apparent controversy of clitoral versus vaginal orgasms. Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology, 6(1), 32578. 10.3402/snp.v6.32578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prause, N., Kuang, L., Lee, P., & Miller, G. (2016). Clitorally stimulated orgasms are associated with better control of sexual desire, and not associated with depression or anxiety, compared with vaginally stimulated orgasms. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13, 1676–1685. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, D. L., Hevesi, K., Conway, G. R., & Kolba, T. N. (2020). Relationship between masturbation and partnered sex in women: Does the former facilitate, inhibit, or not affect the latter? The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(1), 37–47. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayin, H. Ü. (2017). Female orgasmic consciousness: New horizons. SexuS Journal, 2(4), 117–145. [Google Scholar]

- Schiftan, D. (2021). Coming soon: Great orgasms and better sex at your fingertips. Greystone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Štulhofer, A., & Ajduković, D. (2013). A mixed-methods exploration of women’s experiences of anal intercourse: Meanings related to pain and pleasure. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(6), 1053–1062. 10.1007/s10508-012-0068-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Kinsey Institute (2020). Continuum Complete International Encyclopedia of Sexuality (CCIES). https://kinseyinstitute.org/collections/archival/ccies.php