Abstract

Aim

To assess the prevalence of sexual difficulties and related distress, the association between sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance, and to establish whether sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance are moderated by relationship satisfaction.

Methods

This study included a sample of 4160 adults aged 18–89 years enrolled from a randomly selected web panel of 11,685 Norwegians.

Results

Sexual difficulties were particularly common among adults aged <30 years. In men and women, lack of interest in sex and general sexual distress were associated with more sexual avoidance. The association between lack of sexual interest and sexual avoidance was, however, buffered by relationship satisfaction. Climaxing too early was related to less sexual avoidance in both genders. Yet for men, this association was only significant among those with lower relationship satisfaction.

Conclusion

The findings underline the important links among specific sexual difficulties, sexual distress, and the frequency of avoiding sexual activity.

Keywords: Sexual problems, sexual difficulties, sexual distress, sexual avoidance, relationship satisfaction

Introduction

Sexual difficulties throughout the life course are encountered by many men and women worldwide (Christensen et al., 2011; Hendrickx et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2013; Peixoto & Nobre, 2015; Træen & Stigum, 2010). In a large population-based survey of 16–74 year-old people from Great Britain, 42% of men and 51% of women reported having experienced at least one sexual problem lasting 3 months or longer in the previous year (Mitchell et al., 2013). In a Norwegian sample of 18–67 year-old adults, the most common sexual problem reported by men was premature ejaculation, while reduced sexual desire was most prevalent among women (Træen & Stigum, 2010). Although many studies have reported a general increase in the occurrence of sexual difficulties with age (Laumann et al., for the GSSAB Investigator’s Group, 2005; Lee et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2013; Schick et al., 2010; Træen & Stigum, 2010), the reported distress over sexual difficulties seems to be lower among older than younger adults (Corona et al., 2010; Hendrickx et al., 2015; Shifren et al., 2008; Træen et al., 2017). For instance, in a cross-European survey of Norwegian, Danish, Belgic, and Portuguese adults aged 60–75 years (Graham et al., 2020; Hald et al., 2019), many men and women experienced sexual difficulties, but substantial proportion reported no or only mild distress about these difficulties.

Both sexual difficulties and related distress have previously been shown to have associations with negative outcomes, such as lower quality of life (Laumann et al., 1999; Ventegodt, 1998), and lower sexual satisfaction (Hendrickx et al., 2016; Træen & Stigum, 2010). We know, however, surprisingly little about how specific sexual difficulties, and distress related to those difficulties, are associated with the frequency of avoiding sex with one’s partner. Sexual avoidance is a severely understudied concept. Thus, below we will conceptualize sexual avoidance, outline a theoretical framework to situate the study objectives, and review the current literature on sexual avoidance.

Conceptualizing sexual avoidance

Actively avoiding sex indirectly refers to rejecting a partner’s desire for sex, for example, by avoiding entering into situations that could lead to sex (e.g. going to bed earlier or later, being busy with something) and by reducing physical intimacy (e.g. touching, hugging, cuddling, kissing) (Frost & Donovan, 2021; Hinchliff et al., 2012; Træen, 2008). When actively avoiding sexual activity, the individual prevents direct rejection of his/her partner, prevents the loss of personal control, and prevents disappointing his/her partner (Hinchliff et al., 2012). However, sexual avoidance may also be a response to previous rejection, where the individual avoids initiating sex as a means to prevent further rejection (Frost & Donovan, 2021). As both rejecting and being rejected are associated with a range of negative feelings (e.g. guilt, worry, self-blame, anger, sadness, feeling hurt, and sexual inadequacy) (Frost & Donovan, 2021; Træen, 2008), sexual avoidance may function as a self-protecting strategy (Hinchliff et al., 2012). Under some circumstances, this strategy may be successful; however, it is generally assumed to be problematic as it perpetuates the problem rather than solving it (Mitchell et al., 2011).

According to Barlow’s (1986) theory, sexual avoidance is not only a key consequence of sexual difficulties, but also an important factor in maintaining sexual function problems. Barlow’s model of sexual dysfunction (Barlow, 1986; Wiegel et al., 2007) may provide some explanations on the links between sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance. According to this model, individuals with reduced sexual function enter a sexual encounter with adverse emotions, expectancies, and fears of failure. Negative affect and expectations make the individual focus on nonsexual stimuli. These nonsexual distractions during sex are assumed to intensify anxiety and sustain low arousal, which in turn maintains poor sexual function and subsequently leads to sexual avoidance. Accordingly, more frequent sexual avoidance may imply that previous dysfunctional sexual performance has increased the sensitivity for cues related to anxious apprehension and strengthened the link between sexual situations, negative affect, and poor performance expectancy. As avoidance of sexual activity is likely to increase anxiety for unintentionally having provoked a sexual situation, this coping strategy also inhibits new learning experiences and maintains a negative feedback loop (Barlow, 1986; Stephenson & Meston, 2015; Wiegel et al., 2007). Barlow’s model appears to overlap with Basson’s (2001, 2002) alternative female response cycle. According to Basson, a woman’s positive sexual response cycle is easily weakened or disrupted. Specifically, low sexual desire due to sexual pain can give rise to decreased emotional intimacy, negative outcome expectancies, and feelings of inadequacy, which in turn can lead to the avoidance of being sexually motivated and stimulated.

Sexual difficulties, distress related to sexual difficulties, and sexual avoidance

While there is considerable literature on sexual difficulties and dysfunctions, few empirical studies have explored sexual avoidance (Carvalheira et al., 2020; Stephenson, 2020). In a multi-national study of adults aged 60–75 years from four European countries distressing sexual problems were significantly associated with avoidance of sexual interaction among aging men and women (Carvalheira et al., 2020). A Flemish study compared men and women with distressing sexual difficulties to those reporting non-distressing sexual difficulties. The group experiencing distress was more likely to report frequent sexual avoidance due to their sexual difficulties than the group not experiencing distress (Hendrickx et al., 2016). Furthermore, an online survey of 158 men with sexual problems in the US found significant associations between sexual distress, sexual desire, erectile function, premature ejaculation, and sexual avoidance (Stephenson, 2020). While the European and Flemish studies investigated the link between overall distress related to sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance, Stephenson also explored the association between specific sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance. However, the study was limited to a small sample of men with self-assessed impaired sexual function.

Aims

Based on the theoretical and empirical review two central literature gaps can be identified. First, sexual avoidance is a highly understudied concept (Carvalheira et al., 2020; Stephenson, 2020). Accordingly, little empirical attention has been directed to the association between sexual difficulties, distress related to sexual difficulties, and sexual avoidance (Stephenson, 2020). This is problematic as both Barlow’s (1986) model of sexual dysfunction and Basson’s (2001, 2002) alternative female response cycle point to a vicious cycle between sexual impairment and sexual avoidance.

Second, research to date has only focused on the direct link between sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance, and not on potential factors that may buffer a negative loop between sexual impairment and sexual avoidance. We believe that a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between specific sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance will help to identify couples who might benefit from clinical interventions and inform future research on sexual health promotion. In this context, it may be of interest to investigate the role of relationship quality as a potential moderator between sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance. High relationship quality seems inevitably intertwined with open communication (Mitchell et al., 2011), which in the context of sexual impairment, facilitates the adaptation and evolvement of mutual sexual scripts (Kleinplatz & Diamond, 2014; Mitchell et al., 2011). Thus, within highly satisfying relationships, sexual avoidance may be used less often as a strategy to deal with sexual difficulties. This assumption is consistent with the findings of previous research involving older European adults (Carvalheira et al., 2020), which found a significant association between relationship satisfaction and sexual avoidance. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have assessed whether relationship satisfaction moderates the association between specific sexual difficulties and the frequency of sexual avoidance.

Using data from a national web panel survey among Norwegians 18–89 years, the current study examines three specific research questions:

RQ1: What are the prevalence rates of sexual difficulties and associated distress in Norwegian men and women in different age groups?

RQ2: What are the association between specific sexual difficulties, distress related to those difficulties, and the frequency of avoiding sex with one’s partner in men and women?

RQ3: Does relationship satisfaction buffer the association between specific sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance, if any association was found?

Methods

Participants

Approximately 40,000 Norwegians aged above 15 years are registered as members of Kantar’s Gallup Web Panel (https://www.galluppanelet.no/). These members are not able to recruit themselves, but are randomly recruited based on telephonic interviews. The Web Panel members are representative of the internet population in Norway, which refers to 98% of the population with access to the internet (see http://www.medienorge.uib.no/english/). All survey participation is voluntary. Members of Kantar’s Gallup Web Panel are guaranteed safety and anonymity. Kantar operates with small incentives (e.g. lotteries) to stimulate participation, however, not large enough to be the main motivation to participate in a survey. All ethical guidelines developed for market- and poll organization surveys are guaranteed.

In March 2020, potential participants were recruited via e-mail to obtain a randomly selected sample of 11,685 Norwegians registered in Kantar’s Gallup Panel. A total of 4160 men and women aged 18–89 years did fill out the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 35.6%. Fifty-one percent of the respondents completed the survey on their mobile devices.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

As shown in Table 1, 47.6% of the participants were women, and 52.4% were men. Twelve participants checked the box “other.” As Kantar registered several social background characteristics of their Web Panel members (e.g., sex, age, occupations, etc.), 9 of those 12 participants were classified as women and three were classified as men. The mean age of men was 48.4 years (SD 17.1 years), while the mean age of women was 44.4 years (SD 16.8 years). The proportions of participants who identified as heterosexual were 93.5%, 2.6% identified homosexual/lesbian, 3.3% bisexual/pansexual, and 0.6% as asexual. The majority of men and women reported some higher education, with 41.4% reporting a short university education, and 22.8% reporting a long university education. While only 16.3% lived in rural areas, 56.8% reported that they lived in urban areas. More than six in ten (63.4%) reported living with a partner, 25.4% reported being unmarried, 8.4% were separated or divorced, and 2.8% had become a widow/widower.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample (percent).

| All | Men | Women | p | Norwaya | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 52.4 | 47.6 | ||||

| n = | 4160 | 2181 | 1979 | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Rural | 16.3 | 17.8 | 14.7 | <.001 | ||

| Small town | 26.8 | 28.1 | 25.4 | |||

| Urban/city | 56.8 | 54.1 | 59.9 | |||

| n = | 4141 | 2172 | 1969 | |||

| Level of education | ||||||

| 6–8 years of school | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.4 | <.001 | ||

| 9–10 years of school | 4.6 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 25.8 | ||

| 12–13 years of school | 30.4 | 31.9 | 28.7 | 40,1 | ||

| Bachelor degree or the like | 41.4 | 39.2 | 43.8 | 24.1 | ||

| Master degree, PhD or the like | 22.8 | 22.4 | 23.2 | 10.0 | ||

| n = | 4140 | 2170 | 1970 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Unmarried | 25.4 | 25.3 | 25.6 | <.001 | ||

| Separated/divorced | 8.4 | 7.0 | 10.0 | |||

| Widow/widower | 2.8 | 2.1 | 3.5 | |||

| Married/cohabitant/registered partnership | 63.4 | 65.7 | 61.0 | |||

| n = | 4160 | 2181 | 1979 | |||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Homosexual/lesbian | 2.6 | 3.9 | 1.2 | < .001 | ||

| Heterosexual | 93.5 | 92.7 | 94.3 | |||

| Bisexual/pansexual | 3.3 | 2.8 | 3.8 | |||

| Asexual | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | |||

| Other | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | |||

| n = | 4081 | 2140 | 1941 | |||

Note. Chi-square test of differences for gender.

aCentral Bureau of Statistics 2018, persons 16 years and over.

Measures

The questionnaire, which incorporated 88 items, was based on existing Norwegian and Nordic studies (Kvalem et al., 2014; Lewin et al., 2000; Træen et al., 2016; Træen & Stigum, 2010; Træen et al., 2019), the German Health and Sexuality Survey (GeSiD; https://gesid.eu/studie/), and the British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3; Mitchell et al., 2012). In some cases, the original item was slightly adapted in wording. Indicators of sexual difficulties and associated distress were taken from the Natsal-SF tool (https://www.natsal.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-11/final-questionnaire_technical-report-appendix-b.pdf), a reliable and valid measure of sexual function (Mitchell et al., 2012). The single-item measures assessing the frequency of sexual avoidance and relationship satisfaction came from the GeSiD questionnaire, a revised version of a survey that was extensively pretested during a pilot study of 1155 individuals (Matthiesen et al., 2021). Items on sociodemographic characteristics were taken from the Healthy Sexual Aging project (Træen et al., 2019), and the GeSiD. The age was indicated by year of birth and subsequently recoded into four age groups 1 = 18–29 years, 2 = 30–44 years, 3 = 45–59 years, and 4 = ≥60 years. The four categories were chosen to ensure an approximate equal number of respondents in each group: <30 (n = 882), 30–44 (n = 1225), 45–59 (n = 965), and ≥60 years (n = 1088).

Sexual orientation was indexed via the following item: “Do you currently regard yourself as”: where the given responses were 1 = homosexual/lesbian, 2 = heterosexual, 3 = bisexual/pansexual, 4 = asexual, and 5 = other.

Marital status was assessed by asking, “What is your marital status?” The response categories were 1 = unmarried, 2 = separated/divorced, 3 = widow/widower, and 4 = married/cohabitant/registered partnership.

Education level was assessed as the highest level of formal completed education. The response categories were 1 = primary school (6–8 years at school), 2 = lower secondary school (9–10 years at school), 3 = higher secondary school, high school (12–13 years at school), 4 = college, lower university level (Bachelor degree level or similar), and 5 = higher university level (Master degree, PhD level or similar).

Relationship satisfaction was assessed by a one-item indicator: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your current relationship?” The response options were evaluated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all satisfied to 7 = completely satisfied.

Sexual avoidance was measured by asking: “Have you during the last 12 months deliberately avoided having sex with your partner?” The response options were 1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = occasionally, 4 = often, and 5 = very often. Both measures were taken from the German GeSid survey (https://gesid.eu/studie/).

Sexual difficulties and related distress were adapted from the British Natsal-3 survey (https://www.natsal.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-11/final-questionnaire_technical-report-appendix-b.pdf) by asking “In the last year, have you experienced any of the following for a period of three months or longer?” This was followed by seven options for different sexual difficulties: “lacked interest in having sex,” “lacked enjoyment in sex,” “felt anxious during sex,” “felt no excitement or arousal during sex,” “did not reach climax (experienced an orgasm) or took a long time to reach climax despite feeling excited/aroused,” “reached climax more quickly than I would have liked,” “if men: had trouble getting or maintaining an erection,” and “if women: had an uncomfortably dry vagina.” For each problem, the response options were “yes” or “no.” If participant responded with a “yes,” they were asked to indicate how much distress the problem had caused them (“no distress,” “mild distress,” “moderate distress,” or “severe distress”).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform chi-square analyses, bivariate analyses, and multiple regression analyses. Missing data were generally <5% across the included variables. The question assessing sexual difficulties and distress specifies a time period over the previous 12 months, and for this reason only respondents who had had at least one sex partner in the same period were included in the analysis of sexual difficulties, sexual distress, and sexual avoidance. Only respondents who reported a sexual problem were asked to respond to questions about their level of distress about that sexual problem.

To test for moderation, Hayes’ PROCESS, a macro for SPSS (v3), was used (Hayes, 2018). Once we established evidence that the association between sexual difficulty and sexual avoidance was dependent on relationship satisfaction, inferential tests were conducted to probe the interaction at different values of the moderator. As the moderator was highly skewed, we chose values at the 16th, 50th, and 84th percentiles, followed by an inference to test whether the conditional effects were statistically different from zero at the chosen values (Hayes, 2018; Hayes & Rockwood, 2017). Cases that were missing data for any of the variables in the moderation models were excluded from the analysis (Hayes, 2018).

Results

Prevalence rates of sexual difficulties and associated distress

As shown in Table 2, the most frequently reported sexual problems among men were trouble getting or maintaining an erection (20.3%), lack of interest in having sex (19.9%), inability to climax or taking a long time to reach climax despite feeling excited (19.8%), reaching climax more quickly than the respondent would have liked (19.5%), feeling no excitement or arousal during sex (9.1%), lacked enjoyment in sex (8.6%), and feelings of anxiety during sex (4.0%).

Table 2.

Percent sexually active men and women who have experienced sexual problems for a period of three months or longer in the last year.

| Men % |

Women % |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | <30 | 30–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | p | All | <30 | 30–44 | 45–59 | 60+ | p | |

| Lacked interest in sex | 19.9 | 23.6 | 24.2 | 13.9 | 17.7 | .002 | 36.7 | 38.3 | 40.3 | 37.5 | 23.1 | .001 |

| Lacked enjoyment in sex | 8.6 | 19.0 | 9.7 | 4.7 | 3.6 | .000 | 16.1 | 20.8 | 17.3 | 9.8 | 13.4 | .000 |

| Felt anxious during sex | 4.0 | 8.3 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 1.2 | .000 | 6.5 | 13.9 | 5.3 | 2.0 | 1.1 | .000 |

| No excitement or arousal during sex | 9.1 | 17.8 | 9.9 | 7.2 | 3.9 | .000 | 16.0 | 21.3 | 17.9 | 11.5 | 7.5 | .000 |

| No climax/orgasm took a long | 19.8 | 27.3 | 17.9 | 16.1 | 21.0 | .160 | 29.3 | 40.1 | 31.2 | 19.9 | 16.7 | .000 |

| Reached a climax/orgasm too quickly | 19.5 | 28.5 | 21.8 | 18.6 | 10.5 | .000 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 4.3 | .677 |

| Erectile difficulties | 20.3 | 21.5 | 13.9 | 21.7 | 27.3 | .000 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Vaginal dryness | – | – | – | – | – | – | 18.0 | 20.6 | 13.3 | 17.9 | 24.2 | .261 |

| n = | 1411 | 242 | 476 | 360 | 333 | 1323 | 389 | 452 | 296 | 186 | ||

Note. Testing for age (continuous) by applying independent two-tailed t-test for each sexual problem (e.g., experienced erectile difficulties for a period of three months or longer in the last year versus not). Missing values excluded.

The most commonly reported problems among men according to age were premature ejaculation (<30 years, 28.5%); lack of sexual interest (30–44 years, 24.2%); and trouble getting or maintaining an erection, which increased with increasing age (45–59 years, 21.7%; ≥60 years, 27.3%). The percentage of men reporting sexual difficulties decreased with increasing age, with the exception of men reporting erectile difficulties; this value increased from 21.5% among men aged <30 years to 27.3% among respondents aged ≥60 years.

The most frequently reported sexual problems among women were lack of interest in having sex (36.7%), inability to climax or taking a long time to climax despite feeling excited (29.3%), vaginal discomfort and dryness (18.0%), lack of enjoyment in sex (16.1%), feeling no excitement or arousal during sex (16.0%), anxiety during sex (6.5%), and reaching a climax more quickly than the respondent would have liked (3.6%). The most commonly reported problems among women according to age were: not having an orgasm (<30 years, 40.1%); lack of sexual interest (30–44 years, 40.3%; 45–59 years, 37.5%); and vaginal discomfort and dryness (≥60 years, 24.2%). Except for lubrication difficulties and reaching a climax too quickly, all listed sexual difficulties were more frequently reported by women <30 years of age (see Table 2).

The percentage of men (67.4%) and women (66.6%) who reported at least one sexual difficulty was highest among respondents <30 years, and lowest among men aged 45–59 years (50.0%) and women aged ≥60 years (53.8%). Most respondents reported having or 1–2 difficulties (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Accumulated number of sexual problems among of men and women who have had sexual activity in the past year and experienced sexual problems for a period of 3 months or longer in the last year, by age group.

| Men |

Women |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 30 years |

30–44 years |

45–59 years |

60+ years |

p | < 30 years |

30–44 years |

45–59 years |

60+ years |

p | |||||||||

| % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | |||

| Accumulated number of sexual problems | .000 | .000 | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 32.6 | (79) | 48.5 | (231) | 50.0 | (180) | 40.5 | (135) | 33.4 | (130) | 39.8 | (180) | 44.6 | (132) | 46.2 | (86) | ||

| 1 | 29.3 | (71) | 23.9 | (114) | 29.2 | (105) | 39.3 | (131) | 23.7 | (92) | 27.0 | (122) | 28.0 | (83) | 31.7 | (59) | ||

| 2 | 14.9 | (36) | 14.7 | (70) | 10.8 | (39) | 15.6 | (52) | 16.7 | (65) | 13.5 | (61) | 15.2 | (45) | 11.8 | (22) | ||

| 3 | 12.4 | (30) | 6.7 | (32) | 6.9 | (25) | 3.9 | (13) | 11.1 | (43) | 9.3 | (42) | 7.4 | (22) | 7.5 | (14) | ||

| 4 | 7.4 | (18) | 3.4 | (16) | 2.5 | (9) | 0.3 | (1) | 9.3 | (36) | 6.2 | (28) | 3.7 | (11) | 1.6 | (3) | ||

| 5 | 1.2 | (3) | 1.7 | (8) | 0.6 | (2) | – | (−) | 3.9 | (15) | 2.9 | (13) | 0.7 | (2) | 0.5 | (1) | ||

| 6 | 0.8 | (2) | 0.4 | (2) | – | (−) | 0.3 | (1) | 2.1 | (8) | 1.1 | (5) | 0.3 | (1) | 0.5 | (1) | ||

| 7 | 1.2 | (3) | 0.6 | (3) | – | (−) | – | (−) | – | (−) | 0.2 | (1) | – | (−) | – | (−) | ||

| Percent with at least one sexual problem | 67.4 | 51.5 | 50.0 | 59.5 | .000 | 66.6 | 60.2 | 55.4 | 53.8 | .005 | ||||||||

| (n =) | 242 | 476 | 360 | 333 | 389 | 452 | 296 | 186 | ||||||||||

Note. Chi-square test of differences among age groups. Missing values excluded. Range 0–7 (lacked interest in having sex, lacked enjoyment in sex, felt anxious during sex, felt no excitement or arousal during sex, did not reach a climax (experience an orgasm) or took a long time to reach a climax despite feeling excited, reached a climax (experienced an orgasm) more quickly than you would like, had trouble getting or keeping an erection if men and vaginal dryness if women).

About half of the men and 44% of women who reported sexual difficulties were not or only mildly distressed about these difficulties (Table 4). Orgasmic difficulties (no climax/took too long to climax/climaxing too early) were the least distressing, with the majority of men (65.9–66.7%) and women (68.7–83.3%) reporting no or only mild distress. However, moderate or severe distress was most often reported for erectile difficulties in men (69.0%), and for lubrication difficulties in women (66.5%). Moderate or severe distress was also relatively common among men and women who felt no excitement or arousal during sex (54.8% and 60.9%, respectively).

Table 4.

Levels of distress among of men and women who have had sexual activity with at least one person in the past year and experienced sexual problems for a period of three months or longer in the last year (percent, (n)).

| Men % (n) |

Women % (n) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No or mild distress | Moderate distress | Severe distress | No or mild distress | Moderate distress | Severe distress | |

| Lacked interest in sex | 57.0 (158) | 36.8 (102) | 6.1 (17) | 43.8 (208) | 43.4 (206) | 12.8 (61) |

| Lacked enjoyment in sex | 55.3 (198) | 37.7 (135) | 7.0 (25) | 45.4 (248) | 41.0 (224) | 13.6 (74) |

| No excitement or arousal during sex | 45.2 (57) | 39.7 (50) | 15.1 (19) | 39.0 (82) | 39.0 (82) | 21.9 (46) |

| No climax/orgasm took a long | 66.7 (184) | 30.4 (84) | 2.9 (8) | 68.7 (261) | 26.3 (100) | 5.0 (19) |

| Reached a climax/orgasm too quickly | 65.9 (180) | 27.1 (74) | 7.0 (19) | 83.3 (40) | 14.6 (7) | 2.1 (1) |

| Erectile difficulitesa/vaginal drynessb | 31.0 (88) | 48.2 (137) | 20.8 (59) | 33.5 (79) | 41.5 (98) | 25.0 (59) |

| Distress over at least one sexual problem | 49.4 (383) | 37.7 (292) | 12.9 (100) | 44.0 (342) | 37.3 (290) | 18.7 (145) |

aMen.

bWomen.

Overall, there were no significant age trends in sexual distress across the groups, with the exception of men, who reported moderate to severe distress related to a lack sexual interest more commonly with increasing age (not shown in Table 4).

Association between sexual difficulties, distress, and sexual avoidance

Table 5 shows the association between frequency of avoiding sex during the previous year and specific sexual difficulties, and perceived distress related to sexual difficulties among adults who had sexual activity with at least one person in the preceding year. Lack of interest in having sex was related to avoiding sexual activity with one’s partner in both men (β = .31; p < .001) and women (β = .22; p < .001); compared to men and women who did not lack interest in sex over 3 months or longer in the previous year, those who did report a lack of sexual interest were more frequently avoiding sex. Similarly, lack of enjoyment in sexual activities was significantly related to sexual avoidance, but only among women (β = .16; p < .001); women who reported a lack of enjoyment during sex were more likely to avoid sexual activity during the preceding year. However, experiencing an orgasm more quickly than one would like was negatively associated with sexual avoidance among men and women (β = −.16; p < .001; β = −.08; p =.018, respectively). Specifically, those who reported difficulties with climaxing too early were less likely to avoid sexual activity with their partner.

Table 5.

Frequency of avoiding sex during the past year among men and women who have had sexual activity with at least one person in the past year, by specific sexual difficulties, and perceived distress over sexual difficulties.

| Frequency of avoiding sex in the past year | Men (n = 644) |

Women (n = 650) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | b | SE | β | |

| Lacked interest in sex | .66 | .08 | .31*** | .49 | .09 | .22*** |

| Lacked enjoyment during sex | .19 | .11 | .06 | .40 | .10 | .16*** |

| No excitement/arousal | .11 | .11 | .04 | .03 | .10 | .01 |

| No climax/took too long | .02 | .08 | .01 | −.15 | .08 | −.07 |

| Climax too early | −.34 | .08 | −.16*** | −.38 | .16 | −.08* |

| Erection problemsa/Vaginal drynessb | −.15 | .09 | −.07 | −.12 | .09 | −.05 |

| Perceived distress over sexual problems | .15 | .05 | .13*** | .29 | .05 | .26*** |

| R2 | .20 | .23 | ||||

Note: Multiple regression analysis showing the unstandardized regression coefficients (b), standard errors (SE), standardized coefficient (β), and multiple correlations squared (R2).

a = men; b = women.

*p <.05, ***p <.001.

Finally, perceived distress about sexual problems was significantly related to sexual avoidance among men (β = .13; p = .001) and women (β = .26; p < .001); compared to those with only low levels of “overall sexual distress” (composite variable of distress related to all sexual difficulties), those with high levels of reported distress related to sexual problems avoided sexual activities with their partner.

Does relationship satisfaction moderate the association between sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance?

To examine the possibility that the association between specific sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance varies with relationship satisfaction, we conducted a test of moderation between each sexual difficulty and relationship satisfaction. We found evidence of an interaction effect between relationship satisfaction and lack of interest in having sex among men (b = −.13; 95% CI [−.233, −.032]) and women (b = −.11; 95% CI [−.211, −.011]), relationship satisfaction, and lack of enjoyment during sex in men (b = −.17; 95% CI [−.331, −.002]), and relationship satisfaction and experiencing an orgasm more quickly than one would like in men (b = .17; 95% CI [.062, .285]) (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Interaction between relationship satisfaction and specific sexual difficulties on frequency of avoiding sex during the past year among men and women who have had sexual activity with at least one person in the past year (controlling for agec).

| Frequency of avoiding sex in the past year | Men (n = 1171) |

Women (n = 1068) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | p | b | SE | p | |

| Lacked interest in sex*RS | −.13 | .05 | .010 | −.11 | .05 | .030 |

| Lacked enjoyment during sex*RS | −.17 | .08 | .047 | −.02 | .06 | .784 |

| No excitement/arousal | .08 | .08 | .318 | .03 | .06 | .586 |

| No climax/took too long*RS | .11 | .06 | .058 | .09 | .06 | .129 |

| Climax too early*RS | .17 | .06 | .002 | .07 | .22 | .764 |

| Erection problemsa *RS/vaginal drynessb *RS | .05 | .06 | .449 | .06 | .07 | .332 |

Note: RS: relationship satisfaction; b: unstandardized path coefficients; SE: standard error.

aMen.

bWomen.

cContinuous.

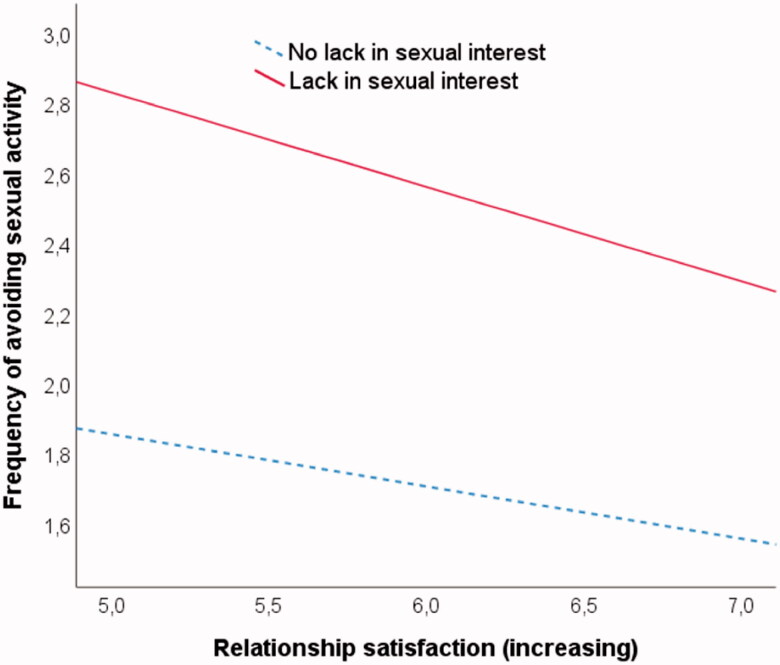

As depicted in Figure 1, increased relationship satisfaction was related to less sexual avoidance for both those who reported a lack of sexual interest and those who did not. Despite this, the gap between sexual avoidance in those lacking interest in sex and those not lacking interest in sex was greatest at lower relationship satisfaction. With higher levels of relationship satisfaction, the gap became smaller.

Figure 1.

Interaction between lacking interest in sex and relationship satisfaction predicting sexual avoidance in men and women.

The pick-a-point approach was applied to compare three levels of relationship satisfaction (25th, 50th, and 84th percentiles) (Hayes, 2018). The association between lack of interest in having sex and sexual avoidance was statistically significant at all levels, but the size of the link became weaker with increasing relationship satisfaction in men (16th = .90, 95% CI [.751, 1.040]; 50th = .76, 95% CI [.635, .891]; 84th = .63, 95% CI [.451, .810]) and women (16th = .93, 95% CI [.775, 1.079]; 50th = .82, 95% CI [.700, .931]; 84th = .70, 95% CI [.551, .858]). The relationship between lack of enjoyment during sex and avoiding sexual activity in men displayed a similar pattern, as the association became weaker with increasing relationship satisfaction (16th = .57, 95% CI [.353, .784]; 50th = .40, 95% CI [.187, .617]; 84th = .24, 95% CI [−.080, .552]). However, the moderating effect became non-significant at relatively high relationship satisfaction (84th percentile).

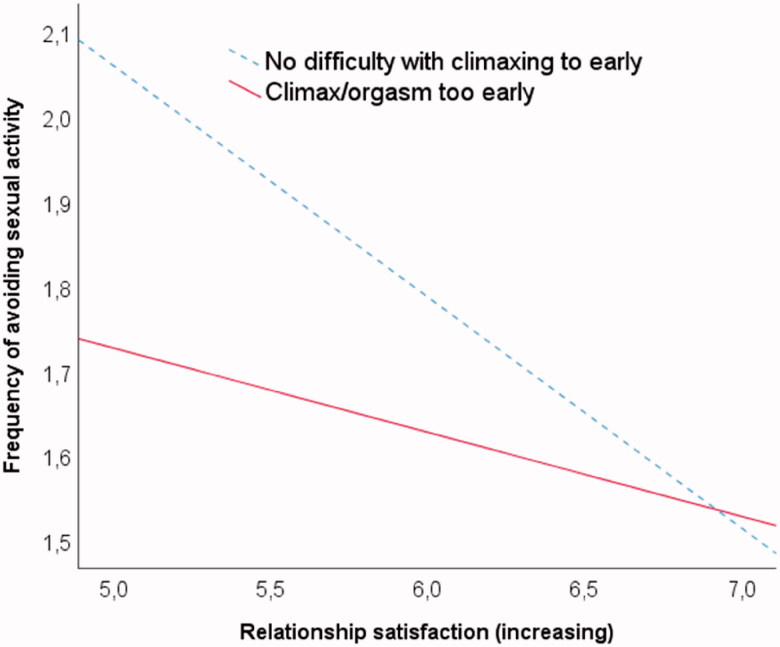

Similar to other sexual difficulties, increased relationship satisfaction was associated with a decrease in sexual avoidance for people who climaxed too early and those who did not. However, those with no difficulty were more likely to avoid sexual activity than those who reported climaxing too early, when relationship satisfaction was low. With increasing relationship satisfaction, the gap between the two groups diminished; no gap was noted with regard to high relationship satisfaction (completely satisfied).

Probing the interaction showed that the association between climaxing too early and sexual avoidance became non-significant with relatively high relationship satisfaction (16th = −.33, 95% CI [−.496, −.171]; 50th = −.16, 95% CI [−.291, −.029]; 84th = .01, 95% CI [−.168, .195]). Therefore, greater relationship satisfaction is associated with a weaker association between climaxing and avoiding sexual activity in men (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interaction between climaxing too early and relationship satisfaction predicting sexual avoidance in men.

Discussion

In the current study, we found a relatively high prevalence of sexual difficulties among men and women <30 years, with approximately two out of three respondents reporting at least one sexual difficulty lasting 3 months or longer in the previous year. Surprisingly, many older adults reported no sexual difficulties. The level of distress associated with sexual difficulties was generally low in all groups. While orgasmic difficulties were reported to be the least distressing, vaginal dryness in women and erectile difficulties in men were considered the most distressing. Both lack of interest in sex and general distress related to sexual difficulties increased the frequency of avoiding sexual activity among men and women. However, the relationship between lack of sexual interest and sexual avoidance was buffered by the quality of the relationship. Climaxing too early resulted in a decrease in sexual avoidance among men and women. Yet, for men, this association became weaker with increasing relationship satisfaction.

In assessing the prevalence rates of sexual difficulties and associated distress in Norwegian men and women in different age groups (research question 1), one surprising finding was the high percentage of respondents reporting sexual difficulties in the youngest age group, specifically, reduced sexual interest and desire. Previous studies have shown that reduced sexual desire in young women may be related to physical, psychological, and sexual trauma, mental health, illness and drug use, relationship problems, pain during intercourse, and a range of contextual factors (Becker et al., 1986; De Silva, 2001; Mitchell et al., 2013; Shifren et al., 2008; Sims & Meana, 2010; Træen, 2008; Ventegodt, 1998). The high prevalence of sexual difficulties among younger men and women may also be interpreted in light of the contemporary cultural and social context. According to Elias (1978) the development of European societies is a continuous process of civilization. He discovered differences not only in attitudes and behaviors but also in mentalities and described the process of civilization in three different phases. Lyttkens (1989) further developed this theory, claiming that a fourth phase (the age of social competence) of the civilization process emerged between the First and Second World Wars. Individuals in this phase are self-disciplined and the value of self-realization is emphasized. Lyttkens also uses the term “social competence” to describe a social interaction technique that is typical of our time. Social competence is visible in many areas of our social lives, including the ways in which sexuality is handled. Sexual behavior is a social behavior; therefore, a goal is to prove that one is a socially competent sexual practitioner. This is reflected in the media, such as magazines and newspapers, which place great emphasis on how we can improve ourselves as sexual partners. In contemporary society, sexuality has become an area of social competence, where individuals strive to be seen as sexually competent actors. What was previously a private sphere of sexual secrets is revealed in public on a daily basis. Information and messages of encouragement such as sex makes you happy and that sex is something you should have often – and regularly, delight all media (Træen, 2008). This may put the young individual under pressure to perform sexually and may increase awareness of sexual difficulties, particularly in the youngest age groups.

The percentage of respondents reporting sexual difficulties in the oldest age group was lower in this study than in recent studies (Graham et al., 2020; Hald et al., 2019); this was unexpected. The results from this study were derived from a web panel sample. Members of the Gallup Panel are supposed to be representative of Norway’s Internet population, that is, 98% of the population with access to the internet. However, there may be a response bias among respondents >60 years of age. Of the men in this age group, 25% had an MA level and 41% had a BA level of education. The corresponding figures among women were 19% and 56%, respectively. This means that the level of education among respondents aged ≥60 years in this sample was much higher than that in the general population. This may explain the lower proportion of older respondents reporting sexual difficulties in this study compared to that in other studies involving questions using the same phrasing (Graham et al., 2020; Hald et al., 2019). Another explanation for the lower proportion of sexual difficulties among respondents aged ≥60 years may be a selection problem arising from oversampling of individuals with no difficulties. Overall, the degree of distress related to sexual difficulties was generally low, which has also been previously reported (Hald et al., 2019; Hendrickx et al., 2016; Graham et al., 2020; Mitchell et al., 2013; Santos-Iglesias et al., 2016).

Pertaining research question 2, assessing the relationship between specific sexual difficulties, distress related to sexual difficulties, and the frequency of avoiding sexual activity with one’s partner, we found that distress about sexual difficulties increased the likelihood of avoiding sexual activity in both men and women. This finding is consistent with those of recent research (Carvalheira et al., 2020; Hendrickx et al., 2016; Stephenson, 2020), Moreover, valid with Barlow’s model (Barlow, 1986; Wiegel et al., 2007), some sexual difficulties were associated with sexual avoidance. In particular, lack of interest in having sex and lack of enjoyment during sex (solely in men) were significantly associated with more frequent sexual avoidance. These difficulties may be experienced as more psychological, intentional and under one’s control (e.g. “I don’t want to…ergo it’s my fault”). The lack of interest in sex/enjoyment may, to a greater extent, be attributed to internal causes, which in turn may elicit more negative feelings (e.g. guilt, shame) (Træen et al., 2007), and subsequent avoidance. If the cause of sexual difficulty is considered physical, it seems easier to externalize it (e.g. “I am not able to…ergo it’s less my fault”) and to seek professional help (Mitchell et al., 2011). The important link between sexual interest/desire and sexual avoidance has also been supported by Stephenson (2020), who found that compared to other sexual difficulties (erectile function, premature ejaculation), the lack of sexual desire was the most important predictor of sexual avoidance.

In contrast to previous work (Stephenson, 2020), we found a reverse relationship between climaxing too early and avoiding sexual activity, where climaxing too early was related to less sexual avoidance in both men and women. One possible explanation is that climaxing too early is not necessarily perceived as problematic, and as such do not hamper a couples’ sexual relationship. The fact that “climaxing to early” is not considered as a problem is also reflected in that eight in 10 women (83%) and two in three men (66%) were not or only mildly distressed about this. This explanation collaborates previous research validating the Natsal-SF. Mitchell et al. (2012) found that among all Natsal-SF items “reached a climax more quickly than you would like” was the only item performing poorly. The authors suggested that participants may answer “yes” to this item, not because they actually consider their function as problematic or poor, but because extending orgasm is perceived as an ideal. Although experiencing an orgasm more quickly than one would like decreased the likelihood of avoiding sexual activity, this association was only significant among men with lower relationship satisfaction. Not recognizing premature ejaculation as a problem seems to be particularly true in the context of lower relationship satisfaction. The fact that climaxing to early is not a common difficulty among women, and seldom perceived as problematic, may explain why relationship satisfaction had no influence on the association between climaxing to early and sexual avoidance in women.

Finally, we were interested in whether relationship satisfaction may buffer the association between specific sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance (research question 3). As expected, high relationship satisfaction buffered the link between lacking interest in sex and the likelihood of engaging in sexual avoidance. This is consistent with the findings from a qualitative study investigating coping strategies in the context of sexual difficulties (Mitchell et al., 2011), which showed that relationship context, such as a strong relationship, partners’ positive reaction to the impairment, and a flexible concept of “good-enough sex,” were central aspects facilitating positive adjustment to sexual difficulties. In a strong and positive relationship, there are other important aspects that buffer the detrimental impact of the impairment, thereby assisting positive coping strategies. High relationship satisfaction also served as an important motive for confronting sexual problems (Mitchell et al., 2011), which is in sharp contrast to an avoidance-based approach. These implications are consistent with those of previous studies demonstrating important interconnections between the quality of the relationship, communication, emotional connectedness, and sexual avoidance (Carvalheira et al., 2020; Frost & Donovan, 2021; Gillespie, 2017).

Limitations

Over the years, there has been a substantial decrease in the response rates for Norwegian sexual behavior surveys (63% in 1987, 48% in 1992, 38% in 1997, 34% in 2002, and 23% in 2008 (Træen & Stigum, 2010). Although, the response rate in this survey was relatively low (36%), it was higher than that in the 2008 survey. As all analyses are based on cross-sectional data, inferences about the causal direction of the association between specific sexual difficulties, sexual distress, and sexual avoidance are not warranted. As the amount of explained variance in the models establishing evidence of an interaction effect was modest (10–23%, dependent on the respective sexual difficulty), there is reason to believe that there are other, unmeasured relationship variables that might be significant to understand the association between sexual impairment and sexual avoidance. The quality of the couple communication and level of perceived discrepancy in sexual interest, are likely important characteristics that may affect the frequency of avoiding sexual interactions. The role of these relationship factors remain to be explored in future research. Finally, although it is quite common to choose values of the moderator relying on conventions, such as using values at the mean and ±1 standard deviation, or at the 16th, 50th, and 84th percentiles, these values are arbitrary and depend on sample characteristics, limiting the generalizability of the probing exercise across samples (Hayes & Rockwood, 2017).

Conclusions

Our findings expanded on those reported by previous studies by showing that specific sexual difficulties were related to sexual avoidance in both men and women. Moreover, our results highlight the importance of relationship satisfaction in view of sexual impairment, expanding Barlow’s (1986) model by including relationship satisfaction as a mechanism buffering the association between specific sexual difficulties and sexual avoidance.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the University of Oslo.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper

References

- Barlow, D. H. (1986). Causes of sexual dysfunction: The role of anxiety and cognitive interference. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 140–148. 10.1037/0022-006X.54.2.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson, R. (2001). Human sex-response cycles. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 27(1), 33–43. 10.1080/00926230152035831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson, R. (2002). Women's sexual desire—Disordered or misunderstood? Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 28(1), 17–28. 10.1080/00926230252851168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J. V., Skinner, L. J., Abel, G. G., & Cichon, J. (1986). Level of postassault sexual functioning in rape and incest victims. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 15, 37–49. 10.1007/BF01542303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalheira, A. A., Štulhofer, A., Graham, C., & Træen, B. (2020). Predictors and correlates of sexual avoidance among partnered older adults in Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and Portugal. European Journal of Ageing, 17(2), 175–184. 10.1007/s10433-019-00540-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, B. S., Grønbaek, M., Osler, M., Pedersen, B. V., Graugaard, C., & Frisch, M. (2011). Sexual dysfunctions and difficulties in Denmark: Prevalence and associated sociodemographic factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(1), 121–132. 10.1007/s10508-010-9599-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona, G., Lee, D. M., Forti, G., O’Connor, D. B., Maggi, M., O’Neill, T. W., Pendleton, N., Bartfai, G., Boonen, S., Casanueva, F. F., Finn, J. D., Giwercman, A., Han, T. S., Huhtaniemi, I. T., Kula, K., Lean, M. E. J., Punab, M., Silman, A. J., Vanderschueren, D., … Study, G. (2010). Age-related changes in general and sexual health in middle-aged and older men: Results from the European male ageing study (EMAS). The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(4), 1362–1380. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01601.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, P. (2001). Impact of trauma on sexual functioning and sexual relationships. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 16 (3), 269–278. 10.1080/14681990123900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elias, N. (1978). The civilizing process. Vol I. The history of manners. Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, R., & Donovan, C. (2021). A qualitative exploration of the distress experienced by long-term heterosexual couples when women have low sexual desire. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 36(1), 22–45. 10.1080/14681994.2018.1549360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, B. J. (2017). Sexual synchronicity and communication among partnered older adults. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(5), 441–455. 10.1080/0092623X.2016.1182826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C., Štulhofer, A., Lange, T., Hald, G. M., Carvalheira, A. A., Enzlin, P., & Træen, B. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of sexual difficulties and associated distress among partnered, sexually active older women in Norway, Denmark, Belgium and Portugal. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 2951–2961. 10.1007/s10508-020-01742-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hald, G. M., Graham, C., Štulhofer, A., Carvalheira, A. A., Janssen, E., & Træen, B. (2019). Prevalence of sexual problems and associated distress in aging men across 4 European countries. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16 (8), 1212–1225. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. (2nd ed.). New The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx, L., Gijs, L., & Enzlin, P. (2015). Age-related prevalence rates of sexual difficulties, sexual dysfunctions, and sexual distress in heterosexual women: Results from an online survey in Flanders. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 424–435. 10.1111/jsm.12725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx, L., Gijs, L., & Enzlin, P. (2016). Sexual difficulties and associated sexual distress in Flanders (Belgium): A representative population-based survey study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(4), 650–668. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliff, S., Gott, M., & Wylie, K. (2012). A qualitative study of heterosexual women's attempts to renegotiate sexual relationships in the context of severe sexual problems. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(5), 1253–1261. 10.1007/s10508-012-9903-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinplatz, P. J., & Diamond, L. M., (2014). Sexual diversity. In. Tolman D. L., Diamond L. M., J. A., Bauermeister, George W. H., Pfaus J. G., & Ward L. M. (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology. Vol. 1. Person-based approaches (pp. 245–267). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14193-009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kvalem, I. L., Træen, B., Lewin, B., & Stulhofer, A. (2014). Self-perceived effects of Internet pornography use, genital appearance satisfaction, and sexual self-esteem among young Scandinavian adults. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 8(4), Article 4. 10.5817/CP2014-4-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann, E. O., Nicolosi, A., Glasser, D. B., Paik, A., Gingell, C., Moreira, E., & Wang, T, for the GSSAB Investigators’ Group. (2005). Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 years: Prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. International Journal of Impotence Research, 17(1), 39–57. 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., & Rosen, R. C. (1999). Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281(6), 537–544. 10.1001/jama.281.6.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D. M., Nazroo, J., O'Connor, D. B., Blake, M., & Pendleton, N. (2016). Sexual health and well-being among older men and women in England: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 133–144. 10.1007/s10508-014-0465-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, B., Fugl-Meyer, K., Helmius, G., Lalos, A., & Månsson, S. A. (2000). Sex in Sweden. On the Swedish sexual life. The National Institute of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Lyttkens, L. (1989). Den disiplinerade människan [The disciplined human being]. Almena Förlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Matthiesen, S., Pietras, L., Bode, H., Cholmakow-Bodechtel, C., Cerwenka, S., Pfister, M., von Rüden, U., Steinacker, G., Wiessner, C., Briken, P., & Dekker, A. (2021). Methodology of the German National Sex Survey – GeSiD (German Health and Sexuality Survey). The Journal of Sex Research, 1–11. 10.1080/00224499.2021.1875188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, K. R., King, M., Nazareth, I., & Wellings, K. (2011). Managing sexual difficulties: A qualitative investigation of coping strategies. Journal of Sex Research, 48(4), 325–333. 10.1080/00224499.2010.494332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, K. R., Mercer, C. H., Ploubidis, G. B., Jones, K. G., Datta, J., Field, N., Copas, A. J., Tanton, C., Erens, B., Sonnenberg, P., Clifton, S., Macdowall, W., Phelps, A., Johnson, A. M., & Wellings, K. (2013). Sexual function in Britain: Findings form the third national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles (Natsal-3). The Lancet, 382(9907), 1817–1829. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, K. R., Ploubidis, G. B., Datta, J., & Wellings, K. (2012). The Natsal-SF: A validated measure of sexual function for use in community surveys. European Journal of Epidemiology, 27(6), 409–418. 10.1007/s10654-012-9697-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto, M. M., & Nobre, P. (2015). Prevalence and sociodemographic predictors of sexual problems in Portugal: A population-based study with women aged 18 to 79 years. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(2), 169–180. 10.1080/0092623X.2013.842195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Iglesias, P., Byers, E. S., & Moglia, R. (2016). Sexual well-being of older men and women. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 25(2), 86–98. 10.3138/cjhs.252-A4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., Middlestadt, S. E., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). Sexual behaviors, condom use, and sexual health of Americans over 50: Implications for sexual health promotion for older adults. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(5), 315–329. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifren, J. L., Monz, B. U., Russo, P. A., Segreti, A., & Johannes, C. B. (2008). Sexual problems and distress in United States women: Prevalence and correlates. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 112, 970–978. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181898cdb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims, K. E., & Meana, M. (2010). Why did passion wane? A qualitative study of married women’s attributions for declines in sexual desire. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 36 (4), 360–380. 10.1080/0092623X.2010.498727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, K. R. (2020). Exploring the role of sexual avoidance in male sexual dysfunction. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(4), 522–533. 10.1080/00224499.2019.1663480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, K. R., & Meston, C. M. (2015). Why is impaired sexual function distressing to women? The primacy of pleasure in female sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(3), 728–737. 10.1111/jsm.12804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Træen, B. (2008). When sex becomes a duty. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 23(1), 61–84. 10.1080/14681990701724758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Træen, B., Hald, G. M., Graham, C., Enzlin, P., Janssen, E., Kvalem, I. L., Carvalheira, A. A., & Štulhofer, A. (2017). Sexuality in older adults (65+)—An overview of the literature, Part 1: Sexual function and its difficulties. International Journal of Sexual Health, 29 (1), 1–10. 10.1080/19317611.2016.1224286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Træen, B., Martinussen, M., Öberg, K., & Kavli, H. (2007). Reduced sexual interest in a random sample of Norwegian couples. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 22(3), 303–322. 10.1080/14681990701381203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Træen, B., Samuelsen, S. O., & Roen, K. (2016). Sexual debut ages in heterosexual, lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults in Norway. Sexuality & Culture, 20 (3), 699–716. 10.1007/s12119-016-9353-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Træen, B., & Stigum, H. (2010). Sexual problems in 18-67-year-old Norwegians. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(5), 445–456. 10.1177/1403494810371245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Træen, B., Stulhofer, A., Janssen, E., Carvalheira, A. A., Hald, G. M., Lange, T., & Graham, C. (2019). Sexual activity and sexual satisfaction among older adults in four European countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(3), 815–829. 10.1007/s10508-018-1256-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventegodt, S. (1998). Sex and the quality of life in Denmark. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 27(3), 295–307. 10.1023/A:1018655219133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegel, M., Scepkowski, L. A., & Barlow, D. H. (2007). Cognitive affective processes in sexual arousal and sexual dysfunction. In Janssen E. (Ed.), The psychophysiology of sex (pp. 143–165). Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]