Abstract

Objective

To review the literature that has examined stigma in relation to the design, impact, and ways web apps can alleviate or aggravate sexual health-related stigma.

Methods

Six databases were searched and 17 studies met the inclusion criteria.

Results

While two studies were randomized controlled trials, most studies were descriptive or qualitative. Stigma may be alleviated in web apps through sharing stigma-related experiences, receiving emotional support, and providing anonymous virtual connections Yet, stigma may be aggravated by implied disclosure, inappropriate content, and stigma by association.

Conlcusions

While web apps were able to address stigma to some extent, some strategies employed inadvertently aggravated stigma.

Keywords: Web applications, sexual health-related conditions, public stigma, internalized stigma, mobile apps

Introduction

The growth of web-based applications, henceforth called web apps, such as websites, mobile apps, and social networking sites, has fundamentally changed the way health information is accessed, analyzed, and utilized (Guse et al., 2012). Recent estimates indicate that half of all adults across Europe and the United States, and approximately 70% of all Canadians rely on digital technologies for health-related information before visiting a health professional (Beck et al., 2014; Hesse et al., 2010; Statistics Canada, 2013; Tonsaker et al., 2014). The number of people utilizing technology-based interventions may be greater for sexual health problems that are often perceived as embarrassing, stigmatizing, and difficult to discuss (Berger et al., 2005; Redston et al., 2018). The accessibility, anonymity, and confidentiality of web apps present an incredible opportunity for developing health interventions for people who are otherwise disconnected from conventional health services (Broaddus et al., 2015). More particularly, the privacy and anonymity of web apps may be appealing to people who may experience stigma deriving from a sexual health-related condition (Magee et al., 2012). According to Goffman, stigma dates back to the Greeks and is defined as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting and reduces a person from a whole and a usual person to a tainted and discredited one” (Goffman, 1963). More recently, stigma researchers have identified two main types of stigma: public/enacted stigma and internalized stigma. Public or enacted stigma is the implicit and/or explicit negative reaction toward people with a condition that is considered by some members of society to be abnormal, while internalized stigma generally consists of individuals’ personalized acceptance of stigma as part of their value system and self-concept (Bos et al., 2013; Fuster-Ruizdeapodaca et al., 2014). Modified labeling theory offers a useful framework for explaining the relationship between public/enacted stigma and internalized stigma. According to this theory, when a person is publicly labeled with a stigmatized attribute, such attributes become salient to the person and he/she could internalize the stigmatizing ideas (Link, 1987). The individual may then withdraw socially because they expect others to reject them based on their attributes (Rosenfield, 1997). According to modified labeling theory, public stigma perpetuates internalized stigma.

Although both types of stigma affect people with sexual health-related conditions, internalized stigma is the most challenging form of stigma to be addressed in the context of sexual health (Hood & Friedman, 2011). This can be attributed to the fact that, unlike public stigma, the hidden feelings of shame, blame, and guilt that accompany people with sexual health-related conditions are not immediately apparent, and therefore, may be difficult to directly address. Indeed, people with sexual health-related conditions may be harboring feelings of anxiety, depression, isolation, and hopelessness in anticipation of a possible (accidental) disclosure of status. As Goffman (1963, p. 87) argued, people who live with invisible marks of stigma may ultimately “pay a high psychological price, a very high level of anxiety, in living a life that can be collapsed at any moment” if their status is revealed.

Due to the effect of stigma on peoples’ lives, web apps may be used as plausible alternatives to the predominantly conventional-based onsite services such as sexual health or STI clinics, school health programs on STI, and sexual health campaign programs at designated locations. As web apps are increasingly designed to complement, and in some cases replace, face-to-face services (Jones & Lacroix, 2012), many posit that web apps may have an inherent benefit of assuaging public stigma and possibly reducing internalized stigma among people living with sexual health-related conditions. Indeed, various technology-based interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing sexual health-related stigma by promoting virtual connections, improving peoples’ knowledge and coping skills, and eventually reducing or completely removing the need for people to attend sexual health clinics in-person (Chaudoir et al., 2012; Kerr et al., 2015).

Although web apps are recognized as important tools for promoting engagement in care and potentially alleviating the stigma of sexual health-related conditions (Wadham et al., 2019), limited published research exists on the relationship between stigma and the design and impact of web apps on sexual health-related conditions. Therefore, it is not known whether current sexual health-related web apps would indeed alleviate stigma or may inadvertently exacerbate stigma. The design of sexual health-related apps is important because the issues of stigma, shame, and embarrassment are major concerns among people with sexual health-related conditions, yet very little consideration is given to addressing these concerns during technology design (Baker et al., 2002). Almost all sexual health web apps are designed by software engineers and human-factor specialists for whom technical considerations such as usability and functionality have been the most paramount considerations (Vaes, 2019). However, it has been demonstrated that emotional design considerations including shame and stigma may be critical to a product's success than its utilitarian features (Norman, 2004).

The purpose of this review was to explore, identify, and summarize the current state of the literature that has examined stigma in relation to the design and impact of web apps on sexual health conditions and the ways web apps can alleviate or aggravate stigma. The research questions that guided this review were: 1) What is the state of the literature on stigma in relation to the design of sexual health-related web apps?, 2) What is the impact of web apps on sexual health-related stigma?, and 3) How do web apps alleviate or aggravate sexual health-related stigma?. By “design”, we mean the main features or characteristics of web apps that are employed to address stigma, and “impact” indicates the effect web apps have on alleviating or perpetuating stigma (public/enacted or internalized). We focused on web apps because they: 1) have a standalone user interface that facilitates user interaction, 2) could enable people to access and share information both publicly and anonymously, and 3) can be used to obtain information anytime and anywhere. Text messaging was excluded because it does not have a user interface with a specific focus, is not anonymous, and typically does not provide users with specific information/feedback in a given time.

Materials and method

Given that the use of web apps for alleviating sexual health-related stigma is a relatively new area with scarce research evidence, a scoping review methodology was considered suitable for identifying and mapping the key concepts and issues. The review followed the methodology of Arksey and O’Malley (2005) by: 1) Identifying the research question; 2) Identifying the relevant studies; 3) Selecting the relevant studies; 4) Charting the data; and 5) Collating, summarizing, and reporting results. While Arksey and O’Malley suggested a possible phase of consultation with a core group to whom the topic is of interest, we omitted that phase because we plan to carry out consultation in a future study. The research questions provided the roadmap for the subsequent stages of the review.

Search strategy (identifying the studies)

Due to the multidisciplinary nature of the topic, we examined a variety of information sources in medicine, nursing, allied sciences, computer science/engineering, and psychology. Six electronic databases including CINAHL, PubMed, Embase, Compendex Engineering Village, Medline, and PsychINFO were searched for literature up to April 25, 2021. We identified gray literature by searching up to ten pages of Google and Google Scholar each, however, only 7 pages were retrieved for Google. An additional manual search was conducted by reviewing reference lists of included articles to identify relevant publications that were not returned through the database searches. The search strategy was developed by two authors (AA, LC) and the related search terms were divided into three categories comprising digital health/eHealth, stigma, and sexual health.

In line with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for scoping reviews, we outlined the population, concepts, and context to guide our search strategy. The population for our study includes people of all age groups and sexual identities who use sexual health technologies. The concept includes stigma, sexual health-related conditions, and web apps. Context includes original research articles using surveys, experimental, observational, and qualitative designs as well as review articles such as scoping reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses conducted in all settings across the globe. With the JBI framework as a guide, we used a different combination of search terms for each database to ensure the search results reflected the population, concepts, and context of our topic. Given that web apps and sexual health-related conditions are sometimes inconsistently defined, we used broader search terms that would maximize a full scope of articles returned in each domain. The search strategy includes (sex* edu*cation/OR sexuality/OR sex* health OR sexually transmitted disease/Infect* OR sexual dysfunction/OR sexual behavior/behavior) AND (Internet OR web* OR app* OR internet searching OR web development OR worldwide web OR eHealth OR mHealth OR telehealth OR telenursing OR ubiquitous health OR digital health OR Website OR web technology OR informatics) AND (Stigma* OR Social Stigma* OR, de-stigma* OR stereotype). Where possible, database-specific terms including CINAHL headings and MeSH headings in PubMed were used to supplement the search terms.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For the purpose of this review, web apps include digital technologies such as websites, mobile apps, and patient portals that people use to access and share information. Sexual health-related conditions include sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (e.g., HIV/AIDS, genital herpes, gonorrhea, and chlamydia) as well as conditions/disorders that affect sexual health functioning (e.g., endometriosis, infertility, sexual dysfunctions). Articles were included if they, 1) were focused on patient-facing web apps, 2) were web interventions designed for alleviating stigma OR described stigma management strategies OR described how stigma impacted the use of web apps, 3) were original studies with empirical data, and 4) were web apps that have a user-interface specifically designed for sexual health-related conditions. Articles were excluded if they, 1) were web apps that involved only text messaging, 2) were web apps that focused on changing the behavior of health professionals or healthcare institutions, 3) not available in English, and 4) theory papers, review papers, posters, and abstracts. All retrieved articles were screened based on the title, followed by abstract screening, and finally, full-text review.

Data extraction and categorization

General and specific information from the included articles was extracted and summarized using a spreadsheet to categorize and compare studies and to identify related themes. Information extracted included title of the article, year of publication, authors’ names, geographical location, research methodology, type of web app, type of sexual health-related condition, sample size, study purpose, and main findings/conclusion. To answer the research questions, two reviewers (AA, LC) independently screened the papers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and highlighted patterns across each paper. Following JBI methods of qualitative synthesis and qualitative content analysis described by Elo and colleagues (Elo et al., 2014; Elo & Kyngäs, 2008), codes were inductively generated and assigned to the highlighted text, and initial categories related to our research questions began to emerge. Related categories were clustered into initial themes and then again into major themes that represented a slightly higher level of abstraction of the narrative in each paper. The categories and the grouping into themes were reviewed by all authors and revised through ongoing team discussions.

Results

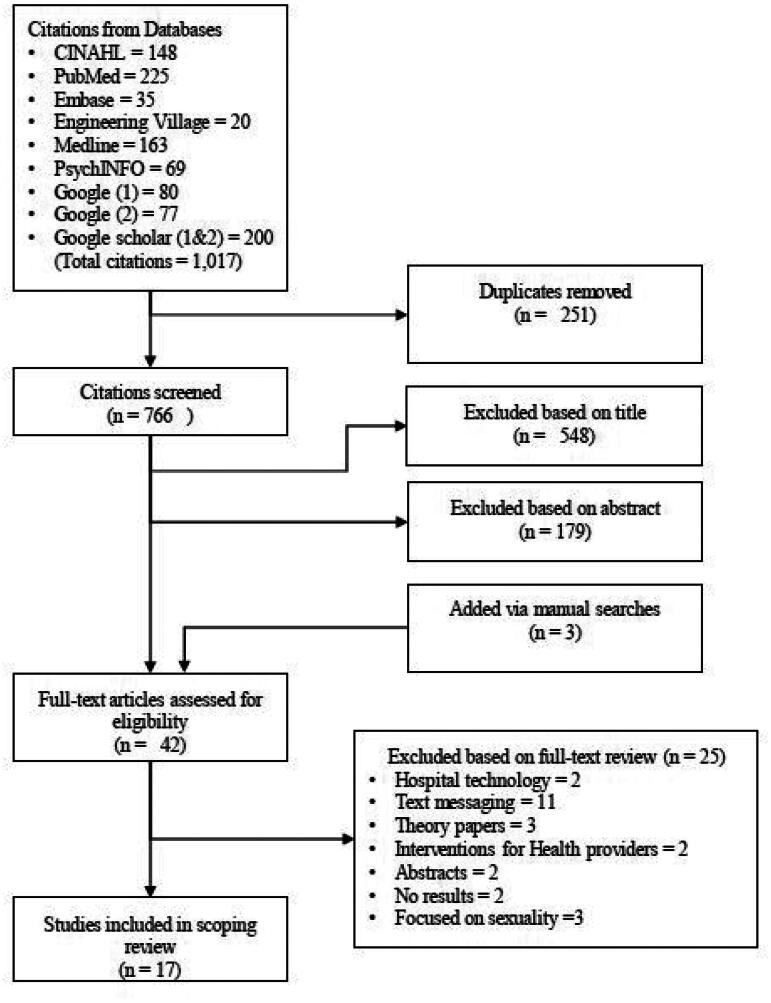

The search strategy yielded 1,017 articles, and all were exported to Endnote X9 (Clarivate™, 2020) software. Google and Google Scholar results were manually added. Endnote was used to remove 251 duplicates. Five hundred and forty-eight (548) articles were removed based on title screening, and 179 were removed based on an abstract review. This resulted in 39 articles that received a full-text review. A manual search of the reference lists of the articles that received full-text review added three articles that were not returned by the search strategy. Thus, a full-text review was conducted on 42 articles. Twenty-five articles were excluded because they did not fully meet the inclusion criteria. Seventeen articles were included in the review. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

Summary of study characteristics

The 17 studies were original peer-reviewed research articles, published between 2012 and 2019. Ten studies used qualitative data collection methods including focus group discussions (3), interviews (2), needs assessment interviews (1), and analysis of participants’ posts in online forums (4). Three studies used quantitative methods, including randomized control designs (2) and a cross-sectional design (1), and four (4) studies used mixed-method designs. Measurement instruments used in the quantitative studies were largely researcher-developed survey tools. The validity and reliability of these instruments were not reported. The participants in the studies were mostly younger than 30 years old, with sample sizes ranging from 31 to 935. Most studies were from the United States (10). Other countries of origin were Canada (2), Australia (2), United Kingdom (1), China (1), and Russia (1). The findings revealed that the use of web apps for sexual health-related stigma was solely focused on the stigma of STIs. No study was found that utilized web technologies in addressing the stigma of disorders that affects sexual functioning including sexual dysfunctions and endometriosis. Six studies were explicitly focused on HIV/AIDS, one on genital herpes, and ten were related to general sexual health and combined STIs (e.g., HIV/AIDS, genital herpes, gonorrhea, and chlamydia). Among ten studies, five were explicitly focused on STIs among people who also identified as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, or Queer (LGBTQ). Only two studies used a theoretical model of stigma to guide the research: Kang and An (2013) used a theoretical model of stigma to guide their study design, while Noltensmeyer et al. (2016) used a theoretical model of stigma as an approach to design the technology. Only two studies reported on the design and development process of web apps (Klein & Lomonaco, 2016; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016). Table 1 shows the details of each study.

Table 1.

Study characteristics, impact on stigma, and corresponding themes.

| Author/Year/Country | Objective/interventions (if relevant) | Method | Sample & Sample size | Findings/Conclusion | Impact of web apps on stigma | Theme |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharing Stigma Post | Content Display | Disclosure | |||||||

| 1 | Bauermeister et al. (2019), USA | To determine if engagement in stigma-related discussions in online forums changes stigma over time. | Baseline, Follow-up surveys & analysis of forum post | 238 YBMSM aged 18–30 years | YBMSM who discussed experiencing HIV stigma in the forums reported decreased stigma over time. Those whose posts indicate anticipated stigma reported an increase in stigma over time | Public; Reduced | X | ||

| 2 | Chen et al. (2019) China | To examine the influence of perceived threats on seeking social support among gay men living with HIV. | Content analysis of “Weibo” post | 133 gay men with HIV | Perceived threat was a motivation to seek online support. However, people who experienced high perceived stigma and perceived severity of HIV reported posting more emotional support seeking messages | General; No Change | X | X | |

| 3 | Israel et al. (2019), USA | To develop and test the efficacy of an online intervention to reduce internalized stigma among bisexual adults with STIs. | Randomized control design | 702 bisexual adults with STI | Internalized binegativity and internalize stigma were reduced in the intervention group compared to the control group. The intervention reduced anticipated stigma in the intervention group | Internal; Reduced | |||

| 4 | Dudina and Tsareva (2018), Russia | How people living with HIV/AIDS discuss status disclosure in online platforms in the context of stigmatization. | Analysis of forum post and follow-up interview | Unspecified | Online communities were related to disclosure and HIV stigmatization. differences in how newly diagnosed and those who live with HIV for a long time react to and manage stigma in online spaces | Public; Worsened | X | X | |

| 5 | Karamouzian et al. (2018), Canada | Compared how stigma differs between online vs. face-to-face and how each mode reduced/exacerbated stigma. | Semi-structured exploratory interviews | 71 youth aged 15–24 years | Online testing can potentially ameliorate experiences of external stigma. Internalized stigma, exacerbated by internal feelings of shame around STIs continues to persist. | Improved Public, not Internal | X | ||

| 6 | Flickinger et al. (2018), USA | To determine whether online discussions of stigma change the stigma levels of people living with HIV at baseline and after 12-months. | Analysis of messaging boards & stigma scores. | 77 &1834 stigma-related posts | People who posted stigma-related content were more likely to show reduced stigma levels after 12 months of follow-up. | Public; Reduced | X | ||

| 7 | Ho et al. (2017), USA | To examine how stigma is perpetuated on HIV testing websites and how it differs based on the levels of online monitoring | Analysis of online post | 210 threads and 319 post | Users largely displayed self-stigmatizing attitudes toward HIV testing in online forums. | Public; Worsened | X | ||

| 8 | Klein and Lomonaco (2016), USA | To develop an HIV digital health program for managing stigma in MSM. | Surveys and focus group discussions | 61 HIV care providers and black MSM | Stigma prevention/management and a safe space/forums for people with STI were the main factors that inform the design of the technology. | General; No Change | X | ||

| 9 | Noltensmeyer et al. (2016), USA | To use a stigma management theory to develop a web-based sexuality education and stigma management program. | Questionnaire and interviews | 171 University student Missouri | People who publicly challenge stigma were less likely to accept that they have a stigmatizing attribute. Individuals who challenge public stigma have greater self-efficacy in practicing safe sex. | Public; Reduced | X | ||

| 10 | Payton and Kvasny (2016), USA | To understand the technology affordance associated with the HIV prevention and stigma awareness website | Focus group discussions | 60 female black students | Students largely expressed concerns about stigma by association, their personal reputations, online social capital resulting in accidental disclosure of status | General; Worsened | X | X | |

| 11 | Witzel et al. (2016), UK | Evaluate how users’ privacy concerns influence their engagement with sexual health programs on Facebook | Semi-structured phone interview | 40 black African gay or bisexual men | Safety concerns, implied disclosure, and stigma by association were identified as barriers to using sexual health-related websites. | General; Worsened | X | X | |

| 12 | Christensen et al. (2013). USA | Test the effectiveness of shame and stigma-reducing video game intervention | Randomized control design | 935 MSM | MSM in the “SOLVE” intervention reported more reduction in shame and stigma over three months than the control group. | Internal; Reduced | |||

| 13 | Kang and An (2013), USA | To evaluate whether drug prescription websites for stigmatized medical conditions contained stigma-reducing components | Content Analysis of websites | 88 drug websites ( e.g HIV, herpes, chlamydia) | Websites for drug prescription on stigmatized conditions are underutilized in disseminating stigma-reducing information, as half of the websites did not contain any stigma alleviating element. | General; No Change | X | ||

| 14 | Byron et al (2013), Australia | To examine the potential for sexual health information on social media | Focus group discussions | 22 people aged 16–22 | Fear of stigma and privacy concerns were raised. The use of humorous videos were noted as the best way to avoid stigma | No reported impact | X | X | |

| 15 | Davis et al. (2012) Canada | Understand young people's views on how sexual health websites can address stigma | Interviews and focus group discussions | 31 young people in Vancouver | More explicit content elicited negative responses from participants and many reacted negatively seeing sexual health information presented callously or crudely. | General; Worsened | X | X | |

| 16 | Magee et al. (2012), USA | Explore aspects of the internet for sexual health information, how the internet may reduce/ exacerbate stigma | Interviews and surveys | 32 LGBTQ people aged 16–24 years | The main reason for not using online health information includes the stigma associated with being caught accessing sexual health information/ stigma by association | General; Worsened | X | X | X |

| 17 | Shearer et al. (2012), Australia | Apply destigmatizing strategies in online video content and examine success in creating destigmatizing messages. | Thematic content analysis of 103 videos | 103 videos | Five destigmatizing strategies were identified in the videos. Humorous messages were found to aggravate stigma | Public; Worsened | X | X | |

Note YBMSM: Young Black Men who Sleep with Men; MSM: Men who Sleep with Men; LGBTQ: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer.

Research question 1: what is the state of the literature on stigma and the design of web apps?

The studies involved varying web apps including websites (10 studies), websites integrated with social media (4), mobile app (1), YouTube (1), and a gaming website (1). Digital platforms such as “Get Yourself Tested” (https://www.cdc.gov/std/sam/gyt/default.htm) and “It Starts With Me” (https://itstartswithme.com/) are specific examples of web apps that were analyzed by studies to understand how their design can address sexual health-related stigma (Karamouzian et al., 2018; Witzel et al., 2016). The main strategies to address stigma in eight of the studies involved mostly interactive features, and educational content. For instance, the studies reported that interactive features including messaging boards and patient forums enable users to access information, express stigma-related concerns, and engage with their peers for social support as ways of addressing sexual health-related stigma (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Dudina & Tsareva, 2018; Flickinger et al., 2018; Ho et al., 2017; Israel et al., 2019; Karamouzian et al., 2018; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016; Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Witzel et al., 2016). Two studies explored healthcare providers' interactions with web app users (Ho et al., 2017; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016), while one study provided participants an opportunity for engagement through customized avatars deployed via a gaming technology (Christensen et al., 2013). Other studies were based on social media platforms integrated with humorous videos and messaging boards/forums as a way of addressing stigma among young people (Byron et al., 2013; Witzel et al., 2016). However, in web apps that used social media platforms, the messaging boards and forums were viewed by participants as non-secure, non-anonymous, and could potentially result in accidental disclosure of status (Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Witzel et al., 2016). Five of the studies were based on educational websites that only enabled users to access information on various stigma management strategies without the ability for interpersonal engagement or interaction (Davis et al., 2012; Israel et al., 2019; Kang & An, 2013; Magee et al., 2012; Shearer et al., 2012). While educational messages may provide credible and reliable information on web apps, how those messages were crafted to specifically address stigma was not explicitly examined in any of the studies. The majority of the studies were centered on web apps that were used in various ways to connect and engage with others through online discussion threads, messaging boards, online forums, and for forming online community support groups. Although the main purpose of the web apps analyzed in the studies was meant to manage sexual health-related conditions and address stigma, only four studies explicitly mentioned stigma management strategies for addressing sexual health-related stigma (Davis et al., 2012; Kang & An, 2013; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016; Shearer et al., 2012). Other studies recommended other strategies such as testimonials and conveying sexual health-related information in a humorous manner as ways of controlling the public narratives that surround sexual health-related conditions (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Dudina & Tsareva, 2018; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016; Shearer et al., 2012).

Research question 2: what is the impact of web apps on sexual health-related stigma?

Addressing/alleviating stigma

Nine studies reported on how web apps either have a positive or a negative impact on sexual health-related stigma. Among the nine studies, six were focused on addressing public stigma (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Dudina & Tsareva, 2018; Flickinger et al., 2018; Ho et al., 2017; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016; Shearer et al., 2012), two focused on addressing internalized stigma (Christensen et al., 2013; Israel et al., 2019), while one study was meant for addressing both internalized and public stigma (Karamouzian et al., 2018). Three of the studies that focused on public stigma were found to have a positive impact by showing some reduced levels of stigma (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Flickinger et al., 2018; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016), while three studies found that the web apps inadvertently worsened public stigma (Dudina & Tsareva, 2018; Ho et al., 2017; Shearer et al., 2012). Two studies that had a focus on internalized stigma also had a positive impact by showing some marginal reduction in internalized feelings of shame and stigma (Christensen et al., 2013; Israel et al., 2019). One study (Karamouzian et al., 2018) found a reduction in public stigma, but not internalized stigma. The other 8 studies were focused on stigma in general, and four of these studies reported a negative impact on stigma (Davis et al., 2012; Magee et al., 2012; Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Witzel et al., 2016), while four reported no impact (Byron et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2019; Kang & An, 2013; Klein & Lomonaco, 2016).

Among the studies that were focused on public stigma, two sought participants’ views on how web apps could alleviate or might aggravate stigma (Karamouzian et al., 2018; Shearer et al., 2012a), while the other four investigated only how web apps could alleviate stigma but did not evaluate how web apps might aggravate stigma. Interestingly, many of the studies that focused on public stigma also happened to be web apps that enabled people to connect online through forums and messaging boards. In summary, six studies had a positive impact on stigma, four reported no change, while seven studies however reported an increase in stigma attributed to web design. See Table 1 for a summary of the impact of web apps on stigma.

Research question 3: how do web apps alleviate or aggravate stigma?

Three overarching themes were identified that represented ways in which web apps may alleviate or aggravate stigma. These include sharing stigma-related experiences via web apps (9 studies), the display of appropriate/inappropriate sexual health-related content (7 studies), and implied disclosure/stigma-by-association (8 studies). The studies were not mutually exclusive to the themes as most studies addressed more than one thematic area. Table 1 shows a summary of the articles together with their respective themes.

Sharing stigma-related experiences via web apps

Nine studies (53%) reported on how the use of web apps functionalities such as online forums, message boards, and the expression of stigma-related experiences or stigma management strategies on web apps could address/aggravate stigma (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Byron et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2019; Dudina & Tsareva, 2018; Flickinger et al., 2018; Ho et al., 2017; Magee et al., 2012; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016; Payton & Kvasny, 2016). This theme is directly related to how the various web apps were used to connect people online. Three studies reported that engaging in online forums and messaging boards could address stigma by promoting virtual connections and boosting emotional support while allowing people affected by similar conditions to engage in anonymous discussions on stigma-related concerns (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Magee et al., 2012; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016). Chen et al. (2019) specifically indicated how people who have high perceived threats and high perceived stigma were likely to post emotional-support-seeking messages on web apps as a way of addressing the threats and stigma inherent in HIV. According to Noltensmeyer et al. (2016), emotional support and anonymous virtual connections are essential in managing sexual health-related stigma for people who may be worried about stigma in onsite spaces. Aside from connecting people through forums and messaging boards, three studies also reported that sharing testimonials, documentaries, and biographies of well-known people via web apps could reduce internalized feelings of stigma and promote a sense of shared experiences (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Dudina & Tsareva, 2018; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016). Although testimonials have been recommended, no studies were located that empirically evaluated how and if the integration of these stories reduced stigma.

While sharing supportive messages via online forums and messaging boards can promote engagement in care, four studies argued that stigmatizing behaviors can still occur in online forums despite these forums tending to be relatively anonymous (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Flickinger et al., 2018; Ho et al., 2017; Magee et al., 2012). These studies reported on how sharing experiences, testimonials, or stories via web apps may give people the chance to share negative expressions and promote online bullying that could eventually (re)produce, perpetuate, and exacerbate stigma. Magee et al. (2012) for instance argued that the face-to-face stigma people experience could be transferred into online spaces. The potential for re-stigmatization was noted to be particularly common in web apps with social media platforms because the mere act of “liking” or “sharing” web content could expose someone to ridicule or online bullying (Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Witzel et al., 2016).

Display of appropriate/inappropriate sexual health-related content

Seven articles highlighted how the display of positive or negative sexual-health related content could alleviate or aggravate stigma, respectively (Davis et al., 2012; Karamouzian et al., 2018; Klein & Lomonaco, 2016; Magee et al., 2012; Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Shearer et al., 2012; Witzel et al., 2016). The studies specifically indicated how inappropriate or vulgar images such as explicit medicalized images, sexualized images of people kissing, or messages such as having “having a fuck buddy” or other sexualized body diagrams on web apps could potentially aggravate stigma. While the intent of displaying explicit sexual images may be to communicate in a way that resonates with the target users, it is important to note that such efforts could inadvertently (re)produce and perpetuate stigma among users who may find such content undesirable (Davis et al., 2012).

Some studies further reported on how some web interventions employ stigmatizing/embarrassing images and messages in a satirical or ironic format (Witzel et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2012), and how some interventions use humor in a stigmatizing manner to convey sexual health information (Shearer et al., 2012). According to these studies, such strategies may not only fail to resonate with the intended users but may reintroduce stigma and stifle general care and prevention efforts. Three studies reported that the use of sexually explicit images or satirical messages could aggravate internalized feelings of stigma and could further widen the barriers to the use of web apps (Davis et al., 2012; Magee et al., 2012; Shearer et al., 2012). Despite the possibility of explicit images to exacerbate stigma, Kang and An (2013) suggested that web apps that displayed biological organs, and symbolic medical diagrams of disease conditions in a positive manner may have the potential of addressing stigma. However, the impact of the display of such images was not explicitly measured in any of the included studies.

Implied disclosure and stigma-by-association

A theme identified in eight of the studies related to how web apps could lead to accidental/implied disclosure of status and the likelihood of stigma-by-association (Byron et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2019; Davis et al., 2012; Dudina & Tsareva, 2018; Magee et al., 2012; Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Shearer et al., 2012; Witzel et al., 2016). Participants were generally concerned about the potential for, and experiences of stigma based on their engagement with web apps. For instance, Witzel et al. (2016) and Byron et al. (2013) indicated that using a sexual health-related web app could be interpreted by others as having the condition – a form of stigma generally referred to as stigma-by-association. The act of stigmatizing people by mere usage of a web app could further increase privacy concerns among users of web apps. This stigma-by-association may not only worsen stigma but could further limit the use of web apps by both people with and without the condition (Witzel et al., 2016). While accidental disclosure and stigma-by-association could occur in all apps that enable people to connect online, it was more of a concern to participants using web apps that did not permit anonymization, including social media platforms (Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Witzel et al., 2016). Stigma via accidental disclosure may be higher on social media platforms because social media sites may be more “porous” or non-secure than web apps designed solely for a specific condition (Byron et al., 2013).

Discussion

This review focused on studies that explored stigma in relation to the design and impact of sexual health-related web apps on stigma. The results suggest that although many web apps are designed to manage and address sexual health-related stigma, such platforms may also perpetuate stigma through sharing stigma-related experiences, displaying inappropriate sexual health content, accidental disclosure of status, and stigma-by-association.

Web app strategies and stigma

Although the main purpose of the studies was to address sexual health-related stigma, many of the studies did not report on any specific strategies that could have been taken to address stigma via web interfaces. Instead, the main web strategies for addressing stigma tend to be largely technical considerations such as web forums, messaging boards, and tailored educational content. Few studies reported on web apps that specifically adopted an anti-stigma approach in designing the user interfaces (Kang & An, 2013; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016). This suggests that many web interventions do not adopt anti-stigma-specific strategies in their approach despite stigma-reduction being a major concern.

Proper integration of the various web strategies on web apps may help address stigma. According to Bauermeister et al. (2019), web forums and messaging boards, when properly integrated with appropriate educational content in web apps could be very helpful in managing the stigma of conditions such as HIV/AIDS. The integration of patient forums and messaging boards in the various web apps could also be beneficial to people who may otherwise be disconnected from, or unwilling to use conventional health services (Broaddus et al., 2015). However, other studies suggest that such design features could inadvertently foment stigma among its users, especially when the people’s identity or status are accidentally disclosed via such forums (Dudina & Tsareva, 2018; Flickinger et al., 2018; Ho et al., 2017; Magee et al., 2012; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016; Payton & Kvasny, 2016). Furthermore, other studies relied on or evaluated web apps that used educational information, integrated with online engagement as the main strategies of addressing stigma. While this could promote understanding of the disease condition while ensuring emotional support, the content could also aggravate internalized stigma if not properly designed or displayed on the web app. In other words, educational content, if not properly conveyed on web platforms may rather foment instead of addressing stigma.

One important strategy for addressing stigma was through the use of an online community of support groups. For instance, web apps that support online collaboration offer an opportunity for like-minded people who might experience stigma in conventional health contexts (e.g., attending an HIV clinic) to form online community support groups and offer emotional supports to members (Kang & An, 2013; Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Witzel et al., 2016). Although the details of the online community support groups were beyond the focus of this review, the use of patient forums and messaging boards as a form of stigma management strategy was evident in eight of the studies (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Dudina & Tsareva, 2018; Flickinger et al., 2018; Ho et al., 2017; Israel et al., 2019; Karamouzian et al., 2018; Noltensmeyer et al., 2016; Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Witzel et al., 2016). Despite the importance of support groups in web platforms, the sensitive nature of sexual health issues may also raise privacy and security concerns among people who engage in online activities. According to Kim et al. (2018), this form of engagement may further inhibit what people are willing to discuss or disclose on online platforms.

The impact of web apps on sexual health-related stigma

Some of the studies suggest that web apps with combined educational and engagement/online connectivity functions were successful to some extent in addressing public stigma (Noltensmeyer et al., 2016; Shearer et al., 2012). Only three studies evaluated web apps that were focused on internalized stigma. Two out of the three studies found a marginal reduction in internalized feelings of shame and stigma (Christensen et al., 2013; Israel et al., 2019). Although few web apps might have been developed for addressing internalized stigma, the results demonstrate a significant positive impact of web apps on internalized stigma. This suggests that web apps may be a favorable platform for addressing the internalized feelings of shame, blame, and guilt that may accompany people with sexual health-related conditions.

Overall, the findings show that studies that demonstrated a reduction in some levels of stigma were largely limited to web apps that promote two-way communication through online collaboration functions such as discussion boards and patient forums (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Christensen et al., 2013; Flickinger et al., 2018; Karamouzian et al., 2018). Standalone educational web apps (i.e., apps without forums, messaging boards, or patient portals) may have a limited capacity to engage people because of their general unidirectional nature. Findings from the studies in this review suggest that apps without two-way communication could perpetuate internalized stigma through an inappropriate choice of words and images in their content design (Davis et al., 2012; Shearer et al., 2012). For instance, Davis et al. (2012) specifically reported how explicit or vulgar sexual images and words such as sexualized images and derogatory statements on web apps could aggravate sexual health-related stigma and deter potential users. In effect, the way words, images, and videos are used to convey a sexual health message in a web app could in itself amplify sexual health-related stigma. This is not to suggest that sexual images or videos would automatically aggravate stigma. On the contrary, sexual images and videos that conform to socially acceptable norms may assuage internalized stigma, as people are more likely to view images that are socially acceptable to them (Hood & Friedman, 2011). The use of socially acceptable images may address stigma because according to Rüsch et al. (2005), understanding the causes of disease as biological processes depicted via images may help reduce the blame and shame associated with such conditions.

Health providers’ moderation of web apps

While online collaboration functions may enable people to connect with others virtually, professional moderation and links to health professionals in forums and messaging boards remained largely missing in the majority of the apps analyzed by the studies. Only Noltensmeyer et al. (2016) recommended some professional moderation of messaging boards. The involvement of healthcare professionals as web moderators may mitigate bullying and online stigmatization by peers, regulate the posting of misleading information, and offer additional stigma management strategies to people most vulnerable to online stigmatization (Bauermeister et al., 2019; Flickinger et al., 2018). More specifically, healthcare professional moderation may improve online discourse by allowing users to discuss negative emotions more candidly, and mitigate issues in web apps that participants viewed as insecure and non-anonymous (Payton & Kvasny, 2016; Wadden et al., 2020; Witzel et al., 2016). However, many of the studies analyzed in this review did not involve or consider health provider moderators on the web apps. Despite the benefits of provider moderation, the “presence” of providers may also inhibit participants’ expressions in forums. In a worst-case scenario, provider moderation may prevent the use of web technologies because of the “discomfort” with relaying information to unknown health providers and the limitations of computer-mediated communication channels including misrepresentation by unscrupulous people (Van Uden-Kraan et al., 2008; Witzel et al., 2016).

Recommended design considerations to address stigma

The limitations of web apps in alleviating stigma suggest that web developers need to adopt design strategies that can guarantee the safety of the user in online spaces. Web designers may consider integrating online support groups and social networking functionalities that facilitate anonymous identification with the stigmatized group, promote social identification and social support. Social identification and social support are particularly important because they are hypothesized to increase resistance to stigma and the rejection of negative stereotypes (Crabtree et al., 2010). It has also been demonstrated that online support groups provide opportunities that facilitate social support from a network of people living with sexual health-related conditions as well as empowering them to reject and overcome stigma (Heijnders & Van Der Meij, 2006; Lee & Craft, 2002). Furthermore, strategies including testimonials or humorous stories of well-known people on web apps could help change the public narrative and people’s attitudes toward sexual health-related stigma (Heijnders & Van Der Meij, 2006). Also, as many people may resort to web apps for fear of being stigmatized in healthcare settings (Arkell et al., 2006; Nyblade et al., 2019), providing credible, reliable, and accurate health information may also dispel the myths and misconceptions that often fuels sexual health-related stigma, promote trust, normalize, and destigmatize such conditions (Hirsch et al., 2017; Kwakernaak et al., 2019; Meisenbach, 2010; Sbaffi & Rowley, 2017). These strategies were particularly emphasized in studies that analyzed web apps that relied predominantly on educational content. More importantly, strategies that ensure appealing and comfortable web content are needed to alleviate internalized stigma. This means the framing of sexual health language including the use of nonsensational language and images, and non-embarrassing content should be considered when designing web-based interventions (Davis et al., 2012). These strategies may prevent depicting sexual health-related conditions in a negative, flattering manner on digital platforms (Davidson & Wallack, 2004; Smith, 2007).

While these strategies might have already been adopted or recommended by some of the studies reviewed, there is little empirical evidence to support or refute their use. Therefore, further studies are needed to examine how the integration and use of these design considerations on web apps could address sexual health-related stigma.

Limitations of scoping review

Studies were limited to English language publications. Given that stigma is context-specific (Link & Phelan, 2001), studies that were not in English, yet could be quite relevant to this review, might have been excluded. Also, conference abstracts that might be relevant to the topic may have been excluded. Finally, as web interventions for sexual health stigma are still in their infancy, many interventions may not yet have been published or evaluated.

Quality of the studies

While it is beyond the expectations of a scoping review to examine study quality, the wide variety of study designs demonstrates that this is an emerging topic. Despite showing results for improved or worsened levels of stigma in six studies, only two of the studies were based on randomized control trials (Christensen et al., 2013; Israel et al., 2019). The rest were based on either self-report or an analysis of stigma-related posts on web platforms – methods that are at the bottom of the evidence hierarchy. Therefore, although participants or the web-related forum posts might have revealed some level of stigma reduction or worsening of stigma, such findings may be subject to study biases. Secondly, most of the claims made with regards to stigma-reducing components on various web platforms were subjected to little empirical evaluation. Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain whether such strategies will indeed address stigma when implemented on web apps. Due to the weaknesses of the studies, further studies are needed to empirically test the effectiveness of the stigma-reduction claims made in the studies before a conclusion can be drawn on their effectiveness in addressing stigma.

Conclusion

The review revealed that web apps with online collaboration functions such as patient forums and messaging boards provide an opportunity to alleviate public stigma by promoting engagement in care and offering emotional support to people living with sexual health-related conditions. Two web apps demonstrated a modest reduction in internalized stigma. Educational web apps without online collaboration functions may inadvertently provoke stigma by exposing users to inappropriate sexual health-related content or by accidentally disclosing their (supposed) sexual health conditions. These findings have considerable implications for how sexual health-related technologies could be designed and deployed to reduce stigma. Web content that inadvertently exacerbates stigma, including the use of profane language should be minimized (Davis et al., 2012). The design of web apps should include appropriate content that is thoughtfully displayed to be less stigmatizing to users. The use of appropriate sexual content and how that content is displayed could have a de-stigmatizing effect on people with sexual health-related conditions.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Designing For People NSERC CREATE program at the University of British Columbia.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors are solely responsible for the content and writing of the manuscript.

References

- Arkell, J., Osborn, D. P. J., Ivens, D., & King, M. B. (2006). Factors associated with anxiety in patients attending a sexually transmitted infection clinic: Qualitative survey. International Journal of STD and AIDS, 17(5), 299–303. 10.1258/095646206776790097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, K., Greenberg, S., & Gutwin, C. (2002). Empirical development of a heuristic evaluation methodology for shared workspace groupware [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. 10.1145/587091.587093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister, J. A., Muessig, K. E., LeGrand, S., Flores, D. D., Choi, S. K., Dong, W., Sallabank, G., & Hightow-Weidman, L. B. (2019). HIV and sexuality stigma reduction through engagement in online forums: Results from the HealthMPowerment intervention. AIDS and Behavior, 23(3), 742–752. 10.1007/s10461-018-2256-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, F., Richard, J. B., Nguyen-Thanh, V., Montagni, I., Parizot, I., & Renahy, E. (2014). Use of the internet as a health information resource among French young adults: Results from a nationally representative survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(5), e128. 10.2196/jmir.2934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M., Wagner, T. H., & Baker, L. C. (2005). Internet use and stigmatized illness. Social Science and Medicine, 61(8), 1821–1827. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos, A. E. R., Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., & Stutterheim, S. E. (2013). Stigma: Advances in theory and research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), 1–9. 10.1080/01973533.2012.746147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broaddus, M. R., Marsch, L. A., & Fisher, C. B. (2015). Risks and benefits of text-message-delivered and small-group-delivered sexual health interventions among African American women in the midwestern United States. Ethics and Behavior, 25(2), 146–168. 10.1080/10508422.2014.948957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byron, P., Albury, K., & Evers, C. (2013). It would be weird to have that on facebook”: Young people’s use of social media and the risk of sharing sexual health information. Reproductive Health Matters, 21(41), 35–44. 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41686-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir, S. R., Norton, W. E., Earnshaw, V. A., Moneyham, L., Mugavero, M. J., & Hiers, K. M. (2012). Coping with HIV stigma: Do proactive coping and spiritual peace buffer the effect of stigma on depression? AIDS and Behavior, 16(8), 2382–2391. 10.1007/s10461-011-0039-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., Guo, Y., & Shi, J. (2019). Social support seeking on social media among Chinese gay men living with HIV/AIDS: The role of perceived threat. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, 25(7), 655–659. 10.1089/tmj.2018.0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J. L., Miller, L. C., Appleby, P. R., Corsbie-Massay, C., Godoy, C. G., Marsella, S. C., & Read, S. J. (2013). Reducing shame in a game that predicts HIV risk reduction for young adult MSM: A randomized trial delivered nationally over the Web. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16, 18716. 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, J. W., Haslam, S. A., Postmes, T., & Haslam, C. (2010). Mental health support groups, stigma, and self-esteem: Positive and negative implications of group identification. Journal of Social Issues, 66(3), 553–569. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01662.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, A. E., & Wallack, L. (2004). A content analysis of sexually transmitted diseases in the print news media. Journal of Health Communication, 9(2), 111–117. 10.1080/10810730490425268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, W. M., Shoveller, J. A., Oliffe, J. L., & Gilbert, M. (2012). Young people’s perspectives on the use of reverse discourse in web-based sexual-health interventions. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 14(9), 1065–1079. 10.1080/13691058.2012.714800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudina, V., & Tsareva, A. (2018). Studying stigmatization and status disclosure among people living with HIV/AIDS in Russia through online health communities. SpringerLink. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1), 215824401452263. 10.1177/2158244014522633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flickinger, T. E., DeBolt, C., Xie, A., Kosmacki, A., Grabowski, M., Waldman, A. L., Reynolds, G., Conaway, M., Cohn, W. F., Ingersoll, K., & Dillingham, R. (2018). Addressing stigma through a virtual community for people living with HIV: A mixed methods study of the positivelinks mobile health intervention. AIDS and Behavior, 22(10), 3395–3406. 10.1007/s10461-018-2174-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster-Ruizdeapodaca, M. J., Molero, F., Holgado, F. P. a., & Mayordomo, S. (2014). Enacted and internalized stigma and quality of life among people with HIV: The role of group identity. Quality of Life Research , 23(7), 1967–1975. 10.1007/s11136-014-0653-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. (1963). Ch. 1 Stigma and social identity. In Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. 10.4319/lo.2013.58.2.0489; Simon and Schuster [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guse, K., Levine, D., Martins, S., Lira, A., Gaarde, J., Westmorland, W., & Gilliam, M. (2012). Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: A systematic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(6), 535–543. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnders, M., & Van Der Meij, S. (2006). The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(3), 353–363. 10.1080/13548500600595327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, B. W., Moser, R. P., & Rutten, L. J. (2010). Surveys of physicians and electronic health information. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(9), 859–860. 10.1056/NEJMc0909595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M., Aggarwal, S., Barker, C., Davis, C. J., & Duffy, J. M. N. (2017). Googling endometriosis: A systematic review of information available on the Internet. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 216(5), 451.e1–458.e1. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.11.1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C. L. L., Pan, W., & Taylor, L. D. (2017). Stigma of HIV testing on online HIV forums: Self-stigma and the unspoken. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 55(12), 34–43. 10.3928/02793695-20170905-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood, J. E., & Friedman, A. L. (2011). Unveiling the hidden epidemic: A review of stigma associated with sexually transmissible infections. Sexual Health, 8(2), 159. 10.1071/SH10070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel, T., Choi, A. Y., Goodman, J. A., Matsuno, E., Lin, Y. J., Kary, K. G., & Merrill, C. R. S. (2019). Reducing internalized binegativity: Development and efficacy of an online intervention. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(2), 149–159. 10.1037/sgd0000314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R., & Lacroix, L. J. (2012). Streaming weekly soap opera video episodes to smartphones in a randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV risk in young urban African American/black women. AIDS and Behavior, 16(5), 1341–1358. 10.1007/s10461-012-0170-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H., & An, S. (2013). How direct-to-consumer drug websites convey disease information: Analysis of stigma-reducing components. Journal of Health Communication, 18(12), 1477–1491. 10.1080/10810730.2013.798378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamouzian, M., Knight, R., Davis, W. M., Gilbert, M., & Shoveller, J. (2018). Stigma associated with sexually transmissible infection testing in an online testing environment: Examining the perspectives of youth in Vancouver, Canada. Sexual Health, 15(1), 46. 10.1071/SH17089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, J. C., Valois, R. F., Diclemente, R. J., Carey, M. P., Stanton, B., Romer, D., Fletcher, F., Farber, N., Brown, L. K., Vanable, P. A., Salazar, L. F., Juzang, I., & Fortune, T. (2015). The effects of a mass media HIV-risk reduction strategy on HIV-related stigma and knowledge among African American adolescents. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 29(3), 150–156. 10.1089/apc.2014.0207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., Gambino, A., Sundar, S. S., Rosson, M. B., Aritajati, C., Ge, J., & Fanning, C. (2018). Interface cues to promote disclosure and build community: An experimental test of crowd and connectivity cues in an online sexual health forum. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 2(CSCW), 1–18. 10.1145/3274359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, C., & Lomonaco, C. (2016). Real talk: Developing a computer-delivered sexual health program for black men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 28(6), 455–471. 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.6.455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwakernaak, J., Eekhof, J. A. H., De Waal, M. W. M., Barenbrug, E. A. M., & Chavannes, N. H. (2019). Patients’ use of the internet to find reliable medical information about minor ailments: Vignette-based experimental study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(11), e12278. 10.2196/12278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. D., Craft, E. A. (2002). Protecting one’s self from a stigmatized disease… once one has it. Deviant Behavior, 23(3), 267–299. 10.1080/016396202753561248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Link, B. G. (1987). Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review, 52(1), 96. 10.2307/2095395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magee, J. C., Bigelow, L., DeHaan, S., & Mustanski, B. S. (2012). Sexual health information seeking online: A mixed-methods study among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young people. Health Education and Behavior, 39(3), 276–289. 10.1177/1090198111401384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisenbach, R. J. (2010). Stigma management communication: A theory and agenda for applied research on how individuals manage moments of stigmatized identity. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 38(3), 268–292. 10.1080/00909882.2010.490841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noltensmeyer, C. J., Peters, S., Meisenbach, R. J., & Eastman-Mueller, H. P. (2016). Managing sexual health and related stigma through electronic learning environments. In Health Communication and Mass Media: An Integrated Approach to Policy and Practice, CDC 2009 (pp. 65–80). 10.4324/9781315586335. Routledge [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. A. (2004). Emotional design. Ubiquity, 2004(January), 1–1. 10.1145/985600.966013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nyblade, L., Stockton, M. A., Giger, K., Bond, V., Ekstrand, M. L., Lean, R. M., Mitchell, E. M. H., Nelson, L. R. E., Sapag, J. C., Siraprapasiri, T., Turan, J., & Wouters, E. (2019). Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 25. 10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payton, F. C., & Kvasny, L. (2016). Online HIV awareness and technology affordance benefits for black female collegians - maybe not: The case of stigma. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 23(6), 1121–1126. 10.1093/jamia/ocw017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redston, S., de Botte, S., & Smith, C. (2018). Resolving embarrassing medical conditions with online health information. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 114, 101–105. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield, S. (1997). Labeling mental illness: The effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. American Sociological Review, 62(4), 660. 10.2307/2657432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch, N., Angermeyer, M. C., & Corrigan, P. W. (2005). Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry, 20(8), 529–539. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbaffi, L., & Rowley, J. (2017). Trust and credibility in web-based health information: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(6), e218. 10.2196/jmir.7579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer, L. S., Simmons, L., Mindel, A., Stanberry, L. R., & Rosenthal, S. L. (2012). Reducing the stigma of herpes simplex virus infection: Lessons from an online video contest. Sexual Health, 9(5), 438–444. 10.1071/SH11188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. (2007). Media depictions of health topics: Challenge and stigma formats. Journal of Health Communication, 12(3), 233–249. 10.1080/10810730701266273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2013). Canadian internet use survey, 2012. The Daily. [Google Scholar]

- Tonsaker, T., Bartlett, G., & Trpkov, C. (2014). Health information on the Internet: Gold mine or minefield? Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien; 60(5), 407–408 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaes, K. (August 2019). Design for Empowerment, the Stigma-Free Design Toolkit. In Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (pp. 1012-1030). Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- van Uden-Kraan, C. F., Drossaert, C. H. C., Taal, E., Lebrun, C. E. I., Drossaers-Bakker, K. W., Smit, W. M., Seydel, E. R., & van de Laar, M. A. F. J. (2008). Coping with somatic illnesses in online support groups: Do the feared disadvantages actually occur? Computers in Human Behavior, 24(2), 309–324. 10.1016/j.chb.2007.01.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden, D., August, T., Li, Q., & Althoff, T. (2020). The effect of moderation on online mental health conversations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.09225. [Google Scholar]

- Wadham, E., Green, C., Debattista, J., Somerset, S., & Sav, A. (2019). New digital media interventions for sexual health promotion among young people: A systematic review. Sexual Health.16(2), 101-123 10.1071/SH18127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, T. C., Guise, A., Nutland, W., & Bourne, A. (2016). It Starts with Me: Privacy concerns and stigma in the evaluation of a Facebook health promotion intervention. Sexual Health, 13(3), 228. 10.1071/SH15231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]