Abstract

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is a curriculum-based process that is inclusive to gender and sexual orientation. We used the attitude toward homosexuality scale and the single category implicit association test (SC-IAT) to measure differences between explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexuality between migrant children with 6 years CSE learning experience (experimental group, N = 70) and those without (control group, N = 80). We found that the experimental group had more positive explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexuality than the control group. In conclusion, CSE is a useful process for improving the explicit and implicit attitudes of migrant children toward homosexuality.

Keywords: Comprehensive sexuality education, homosexuality, explicit attitude, implicit attitude, SC-IAT

Introduction

Since the criminal and psychiatric categorization of homosexuality1 was revoked, public attitudes have become slightly more positive and tolerant toward it (Altemeyer, 2001; Donaldson et al., 2017; Gerhards, 2010; Hadler, 2012; Park & Rhead, 2013; Youn, 2018). However, in China, public attitudes remain largely negative (Tang et al., 2016; Wei & Liu, 2019). A brief review of data from the 2010 China Comprehensive Social Survey (CGSS) shows that in response to a question regarding whether the homosexual sex is acceptable, 82.27% of 11,783 Chinese people (aged 17–96 years) stated “it is always unacceptable” while only 0.53% stated that “it is completely acceptable” (Tang et al., 2016). Wei and Liu (2019) surveyed 732 Chinese students from 29 provinces and found that the vast majority of Chinese schools are unfriendly toward homosexual and other sexual minority students. Tong, an institution that serves homosexual individuals in China, surveyed 3,452 Chinese homosexual students and found that 40.64% had suffered school bullying based on sexual orientation (Tong, 2016). Another study surveyed 992 Chinese homosexual individuals and found that 80% of participants considered themselves disadvantaged in society while 40% had suffered prejudice and unfair treatment in different situations (Li et al., 2014).

The influence of homophobia

Prejudice can predict the occurrence of discriminatory behaviors (Fiske, 1998), and accordingly, negative attitudes toward homosexuality tend to intensify homophobic sentiment on school campuses and increase the frequency of school bullying based on sexual orientation (Espelage et al., 2018; van der Star et al., 2021). In China, homosexual students are widely subjected to school violence and bullying (Wang et al., 2020; Wei & Liu, 2015). Bullying can have serious and long-term effects on students (Demol et al., 2021; Jantzer et al., 2021; Smith & Reidy, 2021) and studies suggest that the effects of violence and bullying based on discrimination and prejudice are considerably more serious (Albaladejo-Blázquez et al., 2019; Myers et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2012). First, negative effects on school achievement have been observed. Homosexual students who have been subjected to school violence tend to avoid bullying through absenteeism and pretending to be ill (Rivers, 2000). Second, violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity can cause great harm to physical and mental health. Homosexual students who have experienced school violence either on the Internet or in face-to-face situations are more likely to commit suicide and experience higher levels of depression (Heiden-Rootes et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2011; Sinclair et al., 2012; Smith & Reidy, 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Wei & Liu, 2015) and to engage in risky behaviors (Martin-Storey & Benner, 2019; Poteat et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2012). Moreover, homophobia not only has a negative impact on homosexual students but also on those who are heterosexual. Homophobic name-calling among teenagers is also a predictor of depressive symptoms and substance use by heterosexual students (Rinehart et al., 2020). As well as being the perpetrators of homophobic bullying, heterosexuals can also become victims. Experiencing homophobic bullying is thus a predictor of heterosexual student anxiety (Poteat et al., 2011) and a risk factor for suicide (Parent et al., 2019). Therefore, it is necessary to intervene in negative attitudes toward homosexuality with effective methods that can limit negative behaviors and their serious effects.

The decriminalization of homosexuality in China was marked by the removal of “hooligan crime” from the criminal law in 1997. Further, in 2001, the Chinese Society of Psychiatry revised the Chinese Criteria of Mental Disorders, which de-pathologized homosexuality. In Mainland China, there are no laws or policies specifically related to homosexual individuals, and the topic of sexual orientation is absent from the 19 curriculum standards in compulsory education (Guo & Liu, 2021).

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is a course that comprises appropriate attitudes with regard to sexual orientation and homosexuality, and aims to educates and empowers youth with positive effects. Sexuality education is an important part of the curriculum with legal status in China. In 1988, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China issued the Notice of the CPC Central Committee on the Reforming and Strengthening of Moral Education in Primary and Secondary Schools, stating the necessity of carrying out physical and mental health education for middle school students. In 2011, the State Council of China issued The National Program of Action for Child Development in China (2011–2020) that clearly proposed to integrate sexual and reproductive health education into the compulsory education curriculum system. Therefore, sexuality education is both legal and valued in China (Liu & Yuan, 2017).

Comprehensive sexuality education

This research focuses on the intervention effect of CSE on students’ negative attitudes toward homosexuality. CSE is a process of teaching and studying based on a curriculum that explores the meaning of sexuality from cognitive, emotional, physical, and social dimensions. By emphasizing the values of inclusion, respect, equality, empathy, responsibility, and reciprocity (inextricably linked to human rights), CSE is designed to equip children and young people with knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values to ensure their health, well-being, and dignity (UNESCO, 2018). Specifically, CSE helps students to master communication skills, develop empathy, form respectful sexual and social relations (which enables them to think about how their choices affect themselves as well as others), and improve their physical and mental health. Accordingly, CSE comprises eight key concepts: (1) relationships; (2) values, rights, culture, and sexuality; (3) understanding gender; (4) violence and staying safe; (5) skills for health and well-being; (6) the human body and development; (7) sexuality and sexual behavior; and 8) sexual and reproductive health. Content related to homosexuality is covered in reference to all eight concepts and addresses key issues related to basic rights; for example: “stigmatization and discrimination based on sexual orientation are manifestations of a lack of respect, which will endanger the well-being of others and are violations of their human rights;” “there are many types of family structures and marriages (such as homosexual couples);” and “homophobia harms the LGBT community”.

Some sexuality education has already been delivered based on the CSE guidelines. Many studies have confirmed the positive effect of school-based sexuality education in China. In terms of knowledge, school-based sexuality education can significantly enhance Chinese students’ knowledge of sexual health (Andres et al., 2021; Chi et al., 2015; Lai et al., 2015; Liu & Liu, 2019a; Sa et al., 2021). With regard to attitudes, sexuality education can reduce gender stereotyping (Liu & Liu, 2019a; Sa et al., 2021) and weaken prejudice against AIDS patients (Liu & Liu, 2019b) among Chinese primary students. At the behavioral level, sexuality education can increase the frequency of healthy behaviors among migrant children (Lai et al., 2015) and weaken inner group preferences of primary school students in social decision-making, which is related to the presence of fairness and trust (Su et al., 2020). Besides these benefits, CSE may have a much greater impact on helping children to appreciates the values of tolerance, diversity, respect, equality, empathy, responsibility and reciprocity (UNESCO, 2018).

Studies have found that school-based sexuality education and sexual diversity courses can effectively reduce Chinese heterosexual students’ negative explicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals (Chi et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2019). One US-based study suggests that school-based CSE can reduce the frequency of verbal assaults against homosexual individuals in high schools and increase the likelihood of bystanders intervening when witnessing homosexual students being verbally assaulted (Baams et al., 2017).

However, some shortcomings in the evaluation of sexuality education remain. One shortcoming comes from the limitation of research sampling. Most studies have focused on middle school or university students, while few have studied students in primary school (Haberland & Rogow, 2015; Sa et al., 2021), even though it is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of CSE is a primary school context. First, studies have found that homosexual teenagers “come out” much younger, and that homophobic behaviors of heterosexual students are expressed at a younger age (Poteat & Russell, 2013; Robinson et al., 2013). Second, school violence and bullying are increasing in middle school settings (Birkett et al., 2009; Hymel & Swearer, 2015), and students in adolescence generally exhibit stronger biases and more frequent homophobic behaviors (Birkett et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2013). Therefore, interventions to address homophobic attitudes and behaviors need to start before this period. The current research studied migrant children. Household registration system in China makes it difficult for migrants to access many important welfare supports. Migrant children in China are more likely to face low socioeconomic status, poor social support, and fewer educational resources (Zhang et al., 2017). Previous research found that lower network information accessibility and lower socioeconomic status is a predictor of negative attitudes toward homosexuality (Tang et al., 2016). Accordingly, it will be valuable if the intervention effect can be determined among migrant children.

Another shortcoming stems from the intervention method. Some sexuality education interventions only focus on certain topics of CSE, such as adolescent health, AIDS, or physical development, and intervention strategies are based on short courses or lectures. We assume that it is valuable to evaluate long-term, comprehensive and systematic sexuality education interventions on attitudes toward homosexual individuals.

Explicit attitude, implicit attitude, and their measurement

According to the model of dual attitudes (Fazio & Towles-Schwen, 1999), attitudes can be divided into explicit (which are conscious) and implicit (which can be automatically activated but are subconscious). Implicit attitudes are habitual and automatic and are reflected in an individual’s default reactions when encountering a phenomenon. Explicit attitudes are more likely to be influenced by other factors such as individual will or social approval effects, resulting in a fake form of positivity (Hebert et al., 1995; Randall & Fernandes, 1991; Tan et al., 2021). Previous studies on explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexuality show that they do not always change at the same time (Banse et al., 2001). These studies are consistent with the dual attitudes model, which argues that when an attitude changes, the new attitude overrides the older one rather than replacing it (Wilson et al., 2000). Thus, only focusing on explicit attitudes on CSE evaluations that measure improvements in attitudes toward homosexual individuals is unilateral and may exaggerate its utility. Therefore, it is of practical and theoretical significance to explore whether education can improve students’ implicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals.

Most previous studies on school-based CSE designed to change negative attitudes toward homosexuality only measure the explicit attitude of participants with questionnaires or measure their implicit attitude using the implicit association test (IAT). The IAT is a classic test that measures the strength of association between different conceptions and evaluations (Greenwald et al., 1998). When using the IAT to measure individuals’ implicit attitude toward homosexuality, participants are required to categorize pictures of homosexuality and heterosexuality and different evaluations. If participants complete the task quicker with the pairing (heterosexual pictures + good words/homosexual pictures + bad words) compared to the paring (heterosexual pictures + bad words/homosexual pictures + good words), this suggests that participants have an implicit preference for people who are heterosexual rather than people who are homosexual individuals. In such a scenario, it is hard to distinguish whether the results are due to a negative attitude toward homosexuality or to a neutral attitude toward homosexuality and positive one toward heterosexuality. Thus, a limit is that the IAT can only measure the relative strengths of paired associations rather than a single association with a specific attitude object. The single category IAT (SC-IAT) is a variant of the IAT (Karpinski & Steinman, 2006) that only requires participants responses to a specific attitude object and different evaluations. By using the SC-IAT to measure implicit attitude toward homosexuality, we can obtain a clearer understanding of individual attitude. In addition, compared to the IAT, the SC-IAT requires less practise and critical trials and takes less time to measure. In general, we consider the SC-IAT to be more suitable for our study.

Research purpose and hypothesis

The purpose of this study is to explore whether CSE can improve primary students’ explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals. The main hypothesis of this study is as follows: Compared to individuals who have never received CSE, primary school students who have received six years of CSE have a higher level of sexual knowledge and hold more positive explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexuality.

Methods

Participants

Our participants comprised 150 primary school sixth-grade students from two schools in Beijing (aged 11–14 years, M = 12.44 ± 0.68, 73 boys). Students from the first school (the experimental group) had received six years of CSE courses (N = 70, aged 11–14 years, M = 12.28 ± 0.65, 29 boys). Students from the control group were from another school and had no CSE learning experience (N = 80, aged 11–14 years, M = 12.58 ± 0.68, 44 boys). The two groups were matched in terms of age (t (138) = −2.63, p = .010), grade, sex (χ2 = 2.75, p > .05) and school performance. For the question: “Have you ever discussed the topic of homosexuality with your parents?” there was no significant difference between two groups (experimental group Nyes = 18, control group Nyes = 12; χ2 = 3.24, p > .05), which suggests that participants’ attitudes toward homosexuality at both schools were likely to be little influenced by discussing the issue and related topics with their parents.

The experimental school had been conducting CSE teaching experiments since 2007. Despite the absence of relevant courses in the control school, the head teachers from both schools exhibited positive attitudes toward the implementation of CSE, helping avoid potential bias. The other school characteristics displayed no difference between the two schools. The schools are only 500 m apart and the operating conditions, teacher constitutions, teacher qualifications, teaching equipment, and educational philosophies of both schools are basically the same. A survey of 160 sixth-grade students from both schools (experimental school: N = 78; control school: N = 82) showed that both schools’ students were migrant children with non-Beijing registered permanent residence. Most were an only child (percentage for only children: experimental school 84.1%, control school 71.9%). Most of their parents were migrant workers educated to high school level or less (percentage for fathers with high school or less education: experimental school 95.1%, control school 83.1%, χ2 = 3.19, p > .05; percentage for mothers with high school or less education: experimental school 96.3%, control school, 87.7%, χ2 = 0.75, p > .05) and had similar socio-economic status (SES) (t(159) = −1.86, p = .065). Thus, the two groups in our study exhibited a high degree of homogeneity and comparability.

All the experimental materials had been reviewed by the ethics review committee. All participants and their legal guardians signed informed consent forms and received gifts in the form of stationery, pencils, and pens for their participation.

CSE intervention

The CSE intervention in this study was based on a systematic curriculum development process comprising six steps: curriculum design, textbook writing, teacher training, teaching practice, effect evaluation and feedback, and revision. First, the project team developed a curriculum based on the Health Education Guidelines for Primary and Middle School developed by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in December 2008 and the International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education published by UNESCO in 2009. To enhance understanding in Chinese language and culture, the project team changed the names of some key concepts. For example, “relationship” was adjusted to “family and friends.” Second, the project team wrote the textbook Cherishing Life-Sexual Health Education Textbook for Students in Primary School. In this step, the project team designed outlines and knowledge points, compiled text and illustration, conducted pilot reading and revising. Third, during the seven years of curriculum development, a number of sexuality education teachers received ongoing training. The fourth step involved teaching practice in a pilot school. Participatory teaching (specific activities included telling stories, role-playing, conducting research, and discussing) was the main method used. During the teaching process, the project team observed each lesson to better review and adjust the design of curriculum. The fifth step comprised effect evaluation and feedback. Quantitative and qualitative research methods were used to assess educational outcomes and feedback. The last step involved revision. After making necessary revisions, all the former steps were repeated, thus creating an iterative process. Before commencing with the present study, this curriculum development involved three rounds of teaching experiments.

In the current study, the experimental group was offered CSE courses based on Cherishing Life–Sexuality Education for Primary School Students (Cherishing Life) teaching materials (Liu, 2017). The Cherishing Life textbook series included 12 textbooks covering the first to sixth grades with one book used per semester. Six units were taught per school year. The first semester was divided into three units (Family and Friends, Life Skills, Gender and Rights), while the second semester covered another three units (Human Development, Sexuality and Healthy Behavior, Sexual and Reproductive Health). Each unit included two topics, and the whole set covered 72 topics with one lesson dedicated to each topic. Every CSE course teacher from the experimental school group received training from us (including lectures, teaching seminars, and discussions) to ensure that each teacher developed a good understanding of CSE and its teaching objectives.

Diversity in gender and sexual orientation is a major topic of CSE that focuses on the key values of “equality, respect, tolerance, and diversity.” Corresponding courses focus on diversity in gender and sexual orientation in reference to values, rights, and interpersonal relationships to achieve the following educational objectives: developing a basic knowledge of diversity in sexual orientation; rejecting discrimination and bullying based on gender, gender expression, and sexual orientation; and adopting effective strategies to avoid or stop such forms of discrimination and bullying.

Of the 72 topics included in CSE courses, 28 focus on diversity in gender and sexual orientation across different grades. Their specific focus and content are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Topics Related to Diversity of Gender and Sexual Orientations in CSE Course.

| Grade | Topic | Main contents | Class hour |

|---|---|---|---|

| The first semester of first grade | Sex | Both boys and girls are blessed; boys and girls are equal; boys and girls respect each other | 1 |

| The first semester of second grade | Family is the harbor of love | There are different types of families; every family member is precious; family members share happiness and sorrow together | 1 |

| Peer influence | We are good friends; the positive influence of peers; the negative influence of peers | 1 | |

| Gender equality | Gender equality in family life; gender equality in peer relationship; gender equality in career choice | 1 | |

| The second semester of second grade | Diversity and equality | Everyone is unique; everyone is equal | 1 |

| The first semester of third grade | Tolerance, acceptance, and respect | Tolerance is a virtue; acceptance is generosity; respect is a culture | 1 |

| Gender | Traditional gender expectations are behind the time; the modern gender expectations are diverse; to advocate gender equality | 1 | |

| The second semester of third grade | Puberty is here | Important sighs of the onset of puberty; psychological changes in puberty; interpersonal changes in puberty; happy puberty | 1 |

| Confusions in puberty | Confusions about physical changes; confusions about psychological and interpersonal changes; to ask for help and solve the confusions | 1 | |

| The first semester of fourth grade | To listen, express and empathize | Listen carefully; express confidently; develop empathy | 1 |

| Children’s rights | Children’s rights to survival, development, protection, and participation | 1 | |

| Children’s sexual rights | Children’s rights to sexual health, sex education, and privacy | 1 | |

| The second semester of fourth grade | Appearance and body image | Appearance is affected by genetics, environment, and lifestyle; a person’s value is not determined by appearance; different times and cultures pursue different beauty | 1 |

| Physical attention and contact | Acceptable physical attention and contact; constrained physical attention and contact; to refuse constrained physical attention and contact | 1 | |

| The sex germination of puberty | What is the sex germination of puberty; the performance of sex germination of puberty; how to treat sex germination of puberty properly | 1 | |

| Sex fantasies and dreams in puberty | Sex fantasies in puberty; sex dreams in adolescent | 1 | |

| To prevent and deal with STIs | To cut off the transmission of STIs; improve the ability to deal with STIs | 1 | |

| The first semester of fifth grade | Eliminate discrimination | What is discrimination; harm of discrimination; ways of dealing with discrimination; ways of fighting against discrimination | 1 |

| Learning to refuse | To say “No” firmly; giving reasons for saying “No”; matching word to the deed; to ask trusted adults for help | 1 | |

| Prevention of child sexual abuse | To identifying child sexual abuse; to be alert to potential perpetrators of child sexual abuse; to stay away from dangerous situations of child sexual abuse | 1 | |

| The second semester of fifth grade | Masturbation | Masturbation is normal; masturbation is private; keep body out of harm when masturbating | 1 |

| Romance in puberty | Emotions in puberty; love is a beautiful emotion; Love needs learning | 1 | |

| Prevention and response to HIV and AIDS | To block the transmission of HIV and AIDS; to improve the ability to prevent HIV and AIDS; to respect the rights of people living with HIV and AIDS and prevent the discrimination against them | 1 | |

| The first semester of sixth grade | Understanding marriage | Learn about marriage; to promote freedom of marriage; to insist on equality between men and women; unlawful marriage | 1 |

| Understanding values | What are values; values influence attitudes; values influence behaviors | 1 | |

| Sexual orientation | Types of sexual orientation; the rights of persons with different sexual orientations; fair treatment of people with different sexual orientations | 1 | |

| The first semester of sixth grade | Healthy sexual behavior | What is sexual behavior; responsible sexual behavior; sexual intercourse requires preparation for growth | 1 |

| Prevention of teenage pregnancy | Methods of contraception; how to use condoms correctly; contraception is a shared responsibility of both men and women | 1 |

Materials

SC-IAT test materials

Target images

We created artificial legal Chinese marriage registration photos for use as our target images. Different faces were collected online and randomly combined into pairs. Seven target images of gay men and lesbian women were separately synthesized using Photoshop.

Target words

We selected 40 positive words and 40 negative words from the Chinese syllabus for primary schools and created a five-point scale for our online test. Twelve college students majoring in Chinese education were recruited to evaluate the positive and negative words. The 21 most positive words (e.g., happy, brave, friendly) and 21 most negative words (e.g., selfish, cruel, mean) were chosen as experimental materials.

The SC-IAT test

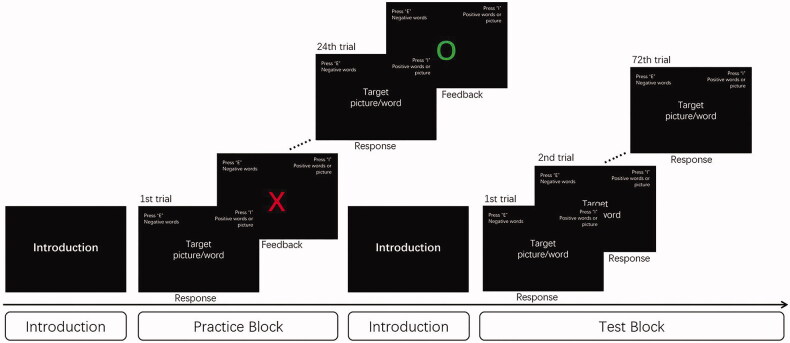

Based on Karpinski and Steinman (2006) standard procedure, the gay men SC-IAT and lesbian women SC-IAT were programmed by Inquisit4. The SC-IAT required participants to classify target images and words referring to different attributes. Each procedure involved two stages, with each comprising 24 practice trials and 72 test trials. The process used for the gay men SC-IAT is shown in Table 2. Figure 1 illustrates each stage of gay men SC-IAT. In the practice blocks, participants were given feedback on the accuracy of their responses for 150 ms after they gave their answer. The participants were reminded to respond faster if more than 1500 ms had passed. No feedback was provided in the formal test block. The target images, positive words, and negative words were presented in a 7:7:10 ratio in the first stage and in a 7:10:7 ratio in the second stage to prevent reaction bias. The participants’ response accuracy levels and reaction times were recorded.

Table 2.

The Mode of Gay Men SC-IAT.

| Stage | Block | Trials | Function | Right-key response | Left-key response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 24 | Practice | Positive words & Target images of gay men | Negative words |

| 2 | 72 | Test | Positive words & Target images of gay men | Negative words | |

| 2 | 3 | 24 | Practice | Positive words | Negative words & target images of gay men |

| 4 | 72 | Test | Positive words | Negative words & target images of gay men |

Figure 1.

An example of gay men SC-IAT compatible stage.

Explicit attitude measures

We used the attitude toward homosexuality scale (AHS) to evaluate the participants’ explicit attitudes, which was suitable for a Chinese social and cultural context (Yu et al., 2010). The AHS was developed and tested with college participants. Guo et al. (2019) modified some items of the AHS and used the new AHS to evaluate 12-year-old participants’ explicit attitudes. The results suggested the new AHS had acceptable reliability and validity for 12-year-old participants. The new AHS adopted a five-point scoring method and included 20 items, including 10 items focusing on lesbian women and 10 focusing on gay men. Participants were asked to rate their agreement or disagreement with the statements; for example, “I do not feel uncomfortable if my teacher is gay man” (1 = extremely disagree to 5 = extremely agree). The scale’s Cronbach’s α was measured as 0.92. Higher scores denoted more positive attitudes toward homosexuality.

CSE questionnaire

We used the CSE questionnaire (a Chinese paper-and-pencil test) to test participants’ sexual knowledge (Su et al., 2020). The questionnaire comprised 82 items, including 35 single choice and 47 true/false items which was designed for primary students from 9 to 12 years old. One point was given for each correct answer for a maximum score of 82. Higher scores indicated a stronger understanding of sexual knowledge. The questionnaire addressed 10 dimensions: family and marriage, life skills, rights, self-protection, reproductive organs, hygiene and health, adolescent development, sexual behaviors, HIV, and reproduction and contraception. The CSE questionnaire had acceptable reliability and validity (Liu & Liu, 2019a, 2019b; Su et al., 2020).

The CSE questionnaire’s Cronbach’s α was measured as 0.84.

Procedure

The participants took the implicit attitude test first. Presentation sequences of the gay men or lesbian women SC-IATs and the different stages of each SC-IAT procedure were balanced to eliminate the effects of the experimental sequence on the experimental results. One SC-IAT test took approximately 5 min to complete. To avoid the influence of explicit attitude on the implicit attitude survey, participants completed the attitude toward homosexuality scale after completing two SC-IAT procedures. To ensure sufficient rest for participants, the CSE questionnaire test was arranged after the explicit and implicit attitudes tests. The researchers collected the questionnaire data immediately after each student had independently completed the survey.

Data analysis

The D-score algorithm for the SC-IAT was modeled on the work of Karpinski and Steinman (2006). For each SC-IAT programme, we excluded participants with accuracy scores of less than 80%. Responses given in either less than 350 ms or more than 1500 ms were also eliminated as well as non-responses. Error responses were replaced with the average reaction time of the given block plus a penalty of 400 ms. Thus, the gay men SC-IAT and lesbian women SC-IAT D-scores were collected to represent the participants’ implicit attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women. We considered the gay men and lesbian women SC-IATs as a whole and recalculated the accuracy. Then we carried out the same elimination and calculated a D-score for homosexuality. The D-score value suggested either positive or negative association with the corresponding group.

We used SPSS 22.0 to analyze the data, which included the participants’ general demographic characteristics, CSE questionnaire scores, and explicit and implicit attitudes. Mean and standard deviation values were used to describe the participants overall. Since a multivariable model required the participants to meet multiple filters at the same time (each test must be completed and each SC-IAT accuracy need to greater than 80%), it would lead to a large amount of elimination. Besides both explicit and implicit attitude scores had potential collinearity problems due to the calculation method. The explicit attitude score toward homosexuality was sum of the scores of explicit attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women. The D-score for homosexuality was derived from recalculating the gay men and lesbian women SC-IAT. Thus, attitude score for homosexuality would positively correlate with both attitude scores for gay men and lesbian women. It would result in the decrease of multivariate model’s validity. Considering above reasons, we ran multiple two-way ANOVA analyses instead of a MANOVA to compare the explicit and implicit attitudes of the experimental and control groups and the influence of gender on the intervention effect. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to reveal the relationships among CSE questionnaire scores and explicit and implicit attitudes.

Results

Sexual knowledge

Participants who did not take the CSE questionnaire were excluded from the analysis, resulting in the elimination of 8 participants (5 girls in the experimental group, 2 boys and 1 girl in the control group). The scores are shown in Table 3. The experimental group’s score was significantly higher than the control group (t (140) = 7.52, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.27). All 10 dimensions covered by the questionnaire had significant differences between two groups: Family and Marriage (t (140) = 5.60, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.43), Life Skills (t (140) = 4.61, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.36), Rights (t (140) = 3.95, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.32), Self-Protection (t (140) = 2.43, p < .05, Cohen’s d = 0.20), Reproductive Organs (t (126.49) = 4.87, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.40), Hygiene and Health (t (122.48) = 5.18, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.42), Adolescent Development (t (140) = 7.03, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.51), Sexual Behaviors (t (140) = 5.99, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.45), HIV (t (140) = 2.21, p < .05, Cohen’s d = 0.18), and Reproduction and Contraception (t (140) = 2.57, p < .05, Cohen’s d = 0.21).

Table 3.

The Scores of CSE Questionnaire.

| CSE questionnaire’s dimension | The experimental group |

The control group |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 65) |

(N = 77) |

|||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Family and marriage*** | 5.68 | 1.19 | 4.48 | 1.33 |

| Life skills*** | 11.74 | 2.26 | 9.88 | 2.49 |

| Rights*** | 4.06 | 1.13 | 3.27 | 1.23 |

| Self-protection* | 6.17 | 1.65 | 5.47 | 1.76 |

| Reproductive organs*** | 2.86 | 1.16 | 1.97 | 0.99 |

| Hygiene and health*** | 4.15 | 1.52 | 2.94 | 1.23 |

| Adolescent development*** | 8.23 | 1.85 | 6.14 | 1.68 |

| Sexual behaviors*** | 9.26 | 2.04 | 7.22 | 2.01 |

| HIV* | 2.77 | 1.01 | 2.39 | 1.03 |

| Reproduction and contraception* | 1.12 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.70 |

| Total*** | 56.05 | 10.03 | 44.55 | 8.19 |

Note. ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Explicit attitude measurement

Explicit attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women

In terms of explicit attitudes toward gay men, participants who did not complete the scale were excluded from analysis, resulting in the elimination of 30 participants (2 boys and 8 girls in the experimental group, 14 boys and 6 girls in the control group). It was found that CSE experience had a significant main effect (F (1,116) = 54.37, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.32). The experimental group (M = 38.83 ± 7.31, N = 60) had significantly more positive explicit attitudes toward gay men than the control group (M = 29.02 ± 7.25, N = 60). The main effect of gender was significant (F (1, 116) = 6.58, p < .05, partial η2 = 0.05). Females (M = 35.75 ± 8.44, N = 63) viewed gay men more positively than males (M = 31.91 ± 8.74, N = 57). The interaction effect between CSE experience and gender was not significant (F (1,116) = .06, p > .05, partial η2 = 0.001).

In terms of explicit attitudes toward lesbian women, participants who did not complete the scale were excluded from the analysis, resulting in the elimination of 21 participants (3 boys and 7 girls in the experimental group, 5 boys and 6 girls in the control group). It was found that CSE experience had a significant main effect (F (1, 125) = 41.67, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.25). The experimental group (M = 39.23 ± 6.80, N = 60) demonstrated significantly more positive explicit attitudes toward lesbian women than the control group (M = 30.49 ± 7.90, N = 69). Gender demonstrated a significant main effect (F (1, 125) = 15.82, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.11). The female participants (M = 37.59 ± 6.84, N = 64) had a more positive views of lesbian women than the male participants (M = 31.57 ± 9.10, N = 65). The interaction effect between CSE experience and gender was not significant (F (1,125) = 0.04, p > .05, partial η2 = 0.000).

Explicit attitudes toward homosexuality

The total scores for explicit attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women were taken as the score for explicit attitudes toward homosexuality. Participants who did not complete the scale were excluded from the analysis, resulting in the elimination of 40 participants (4 boys and 10 girls in the experimental group, 15 boys and 11 girls in the control group). The main effect of CSE experience was significant (F (1, 106) = 50.97, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.36). The experimental group that received comprehensive CSE courses (M = 78.25 ± 13.39, N = 56) demonstrated significantly more positive attitudes toward homosexuality than the control group (M = 58.76 ± 14.97, N = 54). The main effect of gender was significant (F (1, 106) = 9.54, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.08). Females (M = 73.50 ± 15.07, N = 56) viewed homosexuality more positively than males (M = 63.69 ± 17.93, N = 54). The interaction effect between CSE experience and gender was not significant (F (1, 106) = 0.01, p > .05, partial η2 = 0.000).

Implicit attitude measurement

Implicit attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women

For the gay men SC-IAT, participants with an error rate greater than 20% or who did not complete SC-IAT test were excluded from the analysis, resulting in 27 participants being eliminated (5 boys and 5 girls from the experimental group, 11 boys and 6 girls from the control group). A two-way ANOVA showed there was no significant main effect for CSE experience (F (1, 119) = 2.55, p >.05, partial η2 = 0.02). The difference between the experimental and control groups’ D scores for the gay men SC-IAT was significant (experimental group: M = 0.001 ± 0.33, N = 60; control group: M = −0.078 ± 0.35, N = 63). However, the main effect of gender was significant (F (1, 119) = 10.82, p = .001, partial η2 = 0.08). This suggests that males (M = 0.06 ± 0.30, N = 57) had more positive attitude toward gay men than females (M = −0.13 ± 0.36, N = 66) whether or not they had CSE experience. The interaction effect between CSE experience and gender was not significant (F (1, 119) = 2.81, p > .05, partial η2 = 0.02).

For the lesbian women SC-IAT, participants with a correct rate less than 80% or who did not complete SC-IAT test were excluded from analysis, resulting in 27 participants being eliminated (6 boys and 8 girls in the experimental group, 9 boys and 4 girls in the control group). A two-way ANOVA suggested that neither the main effect of CSE experience (F (1, 119) = 3.00, p > .05, partial η2 = 0.03) nor the main effect of gender (F (1, 119) = 1.33, p >.05, partial η2 = 0.01) was significant. The interaction effect between CSE experience and gender was not significant (F (1, 119) = 0.02, p >.05, partial η2 = 0.002).

Implicit attitudes toward homosexuality

Participants with an error rate greater than 20% or who did not complete the SC-IAT test were eliminated, resulting in 23 participants being excluded from the analysis (4 boys and 5 girls in the experimental group, 10 boys and 4 girls in the control group). A two-way ANOVA showed there was significant main effect for CSE experience (F (1, 123) = 8.11, p <.01, partial η2 = 0.06). The experimental group D scores for homosexuality (M = 0.02 ± 0.20, N = 61) was significantly higher than those of the control group (M = −0.09 ± 0.27, N = 66). The main effect of gender was also significant (F (1, 123) = 9.24, p < .01, partial η2 = 0.07). This suggests that males (M = 0.03 ± 0.21, N = 59) had a more positive attitude toward homosexuality than females (M = −0.09 ± 0.26, N = 68). The interaction effect between CSE experience and gender was not significant (F (1, 123) = 3.07, p > .05, partial η2 = 0.02).

Relationship between explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexuality

Correlation analysis was conducted on the students’ explicit attitudes toward homosexuality and implicit SC-IAT D scores. The results are shown in Table 4. There is no significant correlation between the students’ explicit and implicit attitudes toward gay men/lesbian women or between the students’ explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexuality.

Table 4.

Correlation between students' implicit attitude and explicit attitude toward homosexuality.

| Explicit attitude toward gay men |

Explicit attitude toward lesbian women |

Explicit attitude toward homosexuality |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | N | r | p | N | r | p | N | |

| D scores for gay men | 0.16 | .10 | 104 | 0.13 | .17 | 107 | 0.16 | .11 | 95 |

| D scores for lesbian women | 0.13 | .19 | 100 | 0.03 | .73 | 107 | 0.10 | .34 | 93 |

| D scores for homosexuality | 0.12 | .24 | 102 | 0.05 | .64 | 107 | 0.09 | .38 | 95 |

Relationship between sexual knowledge test results and attitudes toward homosexuality

Correlation analysis was conducted on the scores of each dimension of the students’ CSE questionnaire scores and on their explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexuality. The results, presented in Table 5, show that most of the CSE questionnaire’s dimensions (except for HIV and Reproduction and Contraception) were significantly positively correlated with the participants’ explicit attitudes toward homosexuality.

Table 5.

Correlation Between Students' CSE Questionnaire Score and Their Attitude to Homosexuality.

| CSE questionnaire’s dimension | Explicit attitude toward homosexuality |

D scores for homosexuality |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 110) |

(N = 116) |

|||

| R | p | r | p | |

| Family and marriage | 0.34*** | <.001 | −0.02 | .81 |

| Life skills | 0.24* | .01 | 0.15 | .10 |

| Rights | 0.22* | .02 | −0.11 | .25 |

| Self-protection | 0.20* | .04 | 0.10 | .29 |

| Reproductive organs | 0.30** | .001 | 0.28** | .003 |

| Hygiene and health | 0.32** | .001 | 0.23* | .02 |

| Adolescent development | 0.40*** | <.001 | 0.10 | .31 |

| Sexual behaviors | 0.22* | .02 | 0.12 | .21 |

| HIV | 0.10 | .30 | 0.02 | .86 |

| Reproduction and contraception | 0.17 | .08 | −0.06 | .53 |

| Total | 0.40*** | <.001 | 0.15 | .12 |

Note: ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Discussion

The results of this study are consistent with our main hypothesis. CSE not only has a positive effect on students’ sexual knowledge but also on their explicit and implicit attitudes toward people who are homosexual. First, the results are consistent with previous studies that show CSE can effectively improve individuals’ explicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals, gay men, and lesbian women (Guo et al., 2019; Waterman et al., 2001; Wright & Cullen, 2001), and we extend this conclusion to primary school students. Second, primary school students’ implicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals were significantly more positive than those not receiving CSE. This implies CSE can influence not only explicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals but also implicit attitudes. Third, females demonstrated more positive explicit attitudes than males, while males had more positive implicit attitudes than females. Finally, we found no significant correlation between implicit and explicit attitudes. Part of this separation may stem from the small number of trials in the SC-IAT. Karpinski and Steinman (2006) suggest that when the number of trials is reduced, the internal consistency of the SC-IAT is decreased. Although we followed their recommendation to ensure that 24 practice trials and 72 critical trials were included in each stage of the SC-IAT, it is only when we consider gay men and lesbian women SC-IAT as the whole to calculate the D score for homosexuality that the experimental effect appears significant. Conversely, this suggests that when explicit attitude is improved, implicit attitude does not change synchronously with explicit attitude, and implicit attitude may change to a lesser extent. When new attitudes are formed, old attitudes still exist and have an effect. This implies that explicit and implicit attitudes may be two relatively independent systems (Banse et al., 2001). To align implicit and explicit attitudes requires longer-term and deeper intervention.

Some studies have focused on other intervening methods for changing negative attitudes toward homosexual individuals based on explicit attitudes (Ai & Yan, 2017). This raises a question whether CSE, which is a long-term and comprehensive intervention, could effectively change implicit attitudes in the way it affects explicit attitudes. Previous studies on school-based CSE that were designed to change negative attitudes toward homosexual individuals mostly measured explicit attitudes and paid little attention to implicit attitudes (Guo et al., 2019; Waterman et al., 2001; Wright & Cullen, 2001). The current study addresses this gap in past research and proves the effectiveness of CSE in improving both explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals, building on indicators of CSE evaluation and providing further empirical evidence for its generalization. According to the Associative–Propositional Evaluation Model (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2014), implicit attitudes are outcomes of associative processes (the activation of mental associations in memory), while explicit attitudes are outcomes of propositional processes. Propositional processes are the validation of information implied by activated associations, which are guided by the principle of cognitive consistency. Facing a new propositional statement that is inconsistent with the former one, individuals may accept new information and change their attitudes to avoid cognitive dissonance. As described in Methods, CSE is a systematic and long-term curriculum. In CSE, lessons related to gender and sexual orientation illustrate knowledge of gender diversity and sexual orientation diversity, guide children to respect the rights of homosexual individuals, and teach them proper behaviors toward homophobic bullying. Students may be exposed to many propositions inconsistent with negative stereotypes of homosexual individuals, which contribute to a change of explicit attitudes. Meanwhile, students can form new attitude associations through learning propositions, which can influence their implicit attitudes (Lu et al., 2017).

Concretely speaking, the Cherishing Life curriculum promotes equality, respect, pluralism, and tolerance through curriculum design, teaching, and class discussions. CSE curricula include content on gender equality, sexual orientation, and gender expression by discussing, for instance, the division of labor between men and women in the family, social and gender equality in the choice of a career, equality and fraternity in interpersonal communication, rights and laws for social life, the prevention and elimination of gender-based violence, self-protection from campus bullying and sexual abuse, safe sexual behavior, and sexually transmitted infections and AIDS-related knowledge (Liu & Su, 2014). The course focuses on numerous situations in which primary school students interact with homosexual individuals in real life. Teaching goals (knowledge, skills, behavior, and attitudes) of the Cherishing Life curriculum follows an upward spiral and the course is age-appropriate. Meanwhile, the CSE program’s six-year duration, standard class hours, qualified teacher training, and specialized teaching materials support high-quality implementation.

Our intervention targets were migrant children in sixth grade. The age group for which the CSE was assessed with regard to the improvement in attitudes toward homosexual individuals was extended. The issue of homosexuality is a sensitive topic in many countries and cultures around the world, and this is especially true for children and adolescents. Adults may think students do not know about homosexuality or that it is difficult for them to understand sexual orientation. The current study suggests that students in their last year of primary school not only understand the concept of homosexuality but also respect homosexual individuals after receiving CSE.

Few studies focus on homophobic problems among migrant children or on assessing CSE outcomes on migrant children. In China, the migrant population reached 370 million in 2020, indicating that the migrant population is a nonnegligible community (National bureau of statistics of China, 2021). Previous studies suggest that Chinese migrant children have more mental health problems compared to non-migrant children (for example: impulsive, learning anxiety, sensitive, and social anxiety tendencies; Zhang et al., 2019), suffer more bullying (Guo et al., 2017), and are more likely to bully others (Wang et al., 2021). Sexual-orientation-based bullying and related negative outcomes as a special bullying behavior are risk factors for young children (Guo & Liu, 2019; Wei & Liu, 2015). Therefore, it is valuable to intervene in migrant children’s negative attitude toward homosexuality, which partly fills the gap in the existing literature. Improving migrant children’s negative attitudes toward homosexuality may contribute to reducing migrant children’s orientation-based bullying and psychological harm (Rinehart et al., 2020).

Our results suggest sex differences in explicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals, gay men, lesbian women, and female’s attitudes are often more inclusive than those of males. These results are consistent with previous studies in many cultures (Adamczyk & Liao, 2019; Chi & Hawk, 2016; Dessel & Rodenborg, 2017;; Donaldson et al., 2017; Herek, 2000; Korobov, 2004; Russell et al., 2018; Santona & Tognasso, 2018; Zheng et al., 2022). This trend may be attributed to differences in gender norms and beliefs. Male possibly have stronger traditional gender beliefs than females and violating gender norms is considered more serious for males (Kite & Whitley, 1996). According to masculinity theories, homophobic behavior is a manifestation of following masculine norms. Homosexuality is likely to be considered contrary to masculine norms, so male heterosexuals tend to exhibit homophobic behavior to maintain their gender identities (Burns et al., 2015; Javaid, 2017; Korobov, 2004).

However, the results for sex differences in implicit attitudes are not consistent with previous studies (Donaldson et al., 2017). We found males had more positive implicit attitudes toward homosexuality and gay men than females. This result may be related to the particularities of students in their last year of primary school. Previous research has mainly studied adolescents and college students. Among primary school students, issues related to gender and gender identity and the effects of gender norms are less pronounced than they are among adolescents and college students, which may be why we identified an opposite trend of sex differences in implicit attitudes toward homosexuality (Guo et al., 2019). Still, more studies are needed to further explore sex differences in implicit attitudes of primary students. In addition, we did not identify sex differences in implicit attitudes toward lesbian women. One potential explanation is that lesbian women usually experience social negligence (Yao, 2014). Compared with lesbian relationships, gay relationships in the Chinese imperial court prevailed (Zhang, 2007), richly documented in Chinese historical records (Ruan & Tsai, 1987) and Chinese modern art works (such as films, novels, and TV plays), which may result in feminism becoming an absent concept within the broader concept of homosexuality, public awareness of homosexual issues focusing on gay men, and neglecting lesbian women (Cheng, 2018). Therefore, participants in the current study might have clearer schema of gay men than lesbian women, and our results suggest no sex differences in implicit attitudes toward lesbian women. However, more studies are needed to support this explanation.

Traditional Chinese cultural, social, and legal factors may guide some individuals to form negative attitudes toward homosexuality (UNDP, 2016; Wang, 2011). Traditional Confucianism regards homosexuality as a challenge to the harmonious relationship between “阴阳 (Yin and Yang)”, family ethics, and social order (Wang, 2011). In addition, the longstanding stigmatization of homosexuality in Chinese society and the use of insulting terms (such as “娘炮 Niangpao”, sissy, and faggy) have insidiously spread and intensified negative attitudes toward homosexuality. However, homosexuality is a natural form of behavior prevalent throughout human history and negative views of homosexual individuals have a seriously negative impact on homosexual individuals’ physical and mental health. At present, CSE in China is not implemented as part of an extensive system spanning multiple years. The application and verification of CSE through research should be further developed. The current study presents an effective way of promoting sexual orientation equality and of guaranteeing the rights and interests of homosexual individuals. A new multi-system CSE evaluation approach adopting several approaches is also provided.

Limitations

Our study presents some limitations. First, the research samples are relatively small, because the implementation of CSE in China is still in its infancy and CSE has been carried out in only a few schools. In further research, it is planned to promote CSE on a large scale and expand the sample size. Second, the sample in the current study was drawn from a specific migrant community in Beijing; for future studies, a more general sample is needed. Finally, we are both the designer and implementer of the curriculum. Therefore, we undertook two strategies to avoid potential bias: (1) All CSE teachers were trained but knew nothing specifically related to the current study. One of the CSE trainers is a professor from the Netherlands who did not participate current study. (2) Three external researchers who have no working experience in CSE course designs and the Cherishing Life program were responsible for data collection and analysis. Nevertheless, we cannot deny the potential existence of bias in our findings.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that CSE can not only affect the sexual knowledge of primary students but can also affect their explicit and implicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals. The experimental group with CSE was found to exhibit more positive implicit and explicit attitudes toward homosexual individuals. We found no correlation between explicit attitudes and implicit attitudes. The impact of CSE may vary between male and female students. These results not only demonstrate the importance of CSE in promoting equality in sexual orientation but also provide empirical evidence for the effectiveness of an evaluative approach to comprehensive sexuality education.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Beijing Normal University under grant number 2019-01-113-BZK01; and the Ford Foundation under Grant number 1120-1817.

Note

In the current study, homosexuality only means same-sex attraction, including attractions between gay men/ lesbian women.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Adamczyk, A., & Liao, Y. C. (2019). Examining public opinion about LGBTQ-related issues in the United States and across multiple nations. Annual Review of Sociology, 45(1), 401–423. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ai, J., & Yan, J. (2017). 肯定类型对扩展接触改善同性恋态度的影响 [Extended intergroup contact improve attitude toward homosexuality: The influence of positive attitude types. Psychological Exploration, 37(4), 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Albaladejo-Blázquez, N., Ferrer-Cascales, R., Ruiz-Robledillo, N., Sánchez-SanSegundo, M., Fernández-Alcántara, M., Delvecchio, E., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2019). Health-related quality of life and mental health of adolescents involved in school bullying and homophobic verbal content bullying. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2622. 10.3390/ijerph16142622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer, B. (2001). Changes in attitudes toward homosexuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 42(2), 63–75. 10.1300/j082v42n02_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres, E. B., Choi, E. P. H., Fung, A. W. C., Lau, K. W., Ng, N. H. T., Yeung, M., & Johnston, J. M. (2021). Comprehensive sexuality education in Hong Kong: Study protocol for process and outcome evaluation. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–7. 10.1186/s12889-021-10253-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams, L., Dubas, J. S., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2017). Comprehensive sexuality education as a longitudinal predictor of LGBTQ name-calling and perceived willingness to intervene in school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(5), 931–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banse, R., Seise, J., & Zerbes, N. (2001). Implicit attitudes toward homosexuality: Reliability, validity, and controllability of the IAT. Experimental Psychology, 48(2), 145–160. 10.1026//0949-3946.48.2.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett, M., Espelage, D. L., & Koenig, B. (2009). LGB and questioning students in schools: The moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 989–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, M. N., Ryan, D. T., Garofalo, R., Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2015). Mental health disorders in young urban sexual minority men. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(1), 52–58. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, F. K. (2018). Dilemmas of Chinese lesbian youths in contemporary Mainland China. Sexuality & Culture, 22(1), 190–208. 10.1007/s12119-017-9460-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chi, X., & Hawk, S. T. (2016). Attitudes toward same-sex attraction and behavior among Chinese university students: Tendencies, correlates, and gender differences. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1592. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi, X., Hawk, S. T., Winter, S., & Meeus, W. (2015). The effect of comprehensive sexual education program on sexual health knowledge and sexual attitude among college students in Southwest China. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27(2), 2049–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demol, K., Verschueren, K., ten Bokkel, I. M., van Gils, F. E., & Colpin, H. (2021). Trajectory classes of relational and physical bullying victimization: Links with peer and teacher-student relationships and social-emotional outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10.1007/s10964-021-01544-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessel, A. B., & Rodenborg, N. (2017). Social workers and LGBT policies: Attitude predictors and cultural competence course outcomes. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 14(1), 17–31. 10.1007/s13178-016-0231-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, C. D., Handren, L. M., & Lac, A. (2017). Applying multilevel modeling to understand individual and cross-cultural variations in attitudes toward homosexual people across 28 European countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(1), 93–112. 10.1177/0022022116672488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage, D. L., Basile, K. C., Leemis, R. W., Hipp, T. N., & Davis, J. P. (2018). Longitudinal examination of the bullying-sexual violence pathway across early to late adolescence: Implicating homophobic name-calling. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(9), 1880–1893. 10.1007/s10964-018-0827-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, R. H., & Towles-Schwen, T. (1999). The MODE model of attitude-behavior processes. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S. T. (1998). Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski, B., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2014). Implicit and explicit evaluation: A brief review of the associative–propositional evaluation model. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(8), 448–462. 10.1111/spc3.12124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhards, J. (2010). Non-discrimination towards homosexuality: The European union’s policy and citizen’s attitudes towards homosexuality in 27 European countries. International Sociology, 25(1), 5–28. 10.1177/0268580909346704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480. 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H., Chen, L., Ye, Z., Pan, J., & Lin, D. (2017). 流动儿童同伴侵害的特点及与内化问题的循环作用关系:一项追踪研究 [Characteristics of peer victimization and the bidirectional relationship between peer victimization and internalizing problems among rural-to-urban migrant children in China: A longitudinal study]. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 49(3), 336–348. 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.00336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L., Fang, S., Li, Y., Liu, S., & Liu, W. (2019). 性教育课程改善小学生同性恋态度效果评价 [Effectiveness of sexuality education curriculum to improve the attitude towards homosexuality in primary school]. Chinese Journal of School Health, 40(10), 1478–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L., & Liu, W. (2019). 性少数群体校园暴力与欺凌的危险和保护因子 [The risk factors and protective factors of sexual minorities when facing school violence and bullying]. Chinese Journal of School Health, 40(1), 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L., & Liu, W. (2021). 全面性教育视角下中国义务教育阶段课程标准与教材分析 [Curriculum standards and teaching materials in compulsory education in China from the perspective of comprehensive sexuality education]. Chinese Journal of School Health, 42(3), 325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Haberland, N., & Rogow, D. (2015). Sexuality education: Emerging trends in evidence and practice. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(1 Suppl), S15–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadler, M. (2012). The influence of world societal forces on social tolerance. A time comparative study of prejudices in 32 countries. The Sociological Quarterly, 53(2), 211–237. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2012.01232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, J. R., Clemow, L., Pbert, L., Ockene, I. S., & Ockene, J. K. (1995). Social desirability bias in dietary self-report may compromise the validity of dietary intake measures. International Journal of Epidemiology, 24(2), 389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiden-Rootes, K., Wiegand, A., Thomas, D., Moore, R. M., & Ross, K. A. (2020). A National survey on depression, internalized homophobia, college religiosity, and climate of acceptance on college campuses for sexual minority adults. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(4), 435–451. 10.1080/00918369.2018.1550329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek, G. M. (2000). Sexual prejudice and gender: Do heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men differ? Journal of Social Issues, 56(2), 251–266. 10.1111/0022-4537.00164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hymel, S., & Swearer, S. M. (2015). Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. The American Psychologist, 70(4), 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzer, V., Ossa, F. C., Eppelmann, L., Parzer, P., Resch, F., & Kaess, M. (2021). Under the skin: Does psychiatric outcome of bullying victimization in school persist over time? A prospective intervention study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 10.1111/jcpp.13502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaid, A. (2017). In the shadows: Making sense of gay male rape victims’ silence, suffering and invisibility. International Journal of Sexual Health, 29(4), 279–213. 10.1080/19317611.2017.1309484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinski, A., & Steinman, R. B. (2006). The single category implicit association test as a measure of implicit social cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(1), 16–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kite, M. E., & Whitley, B. E. (1996). Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behaviors, and civil rights a meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(4), 336–353. 10.1177/0146167296224002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korobov, N. (2004). Inoculating against prejudice: A discursive approach to homophobia and sexism in adolescent male talk. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 5(2), 178–189. 10.1037/1524-9220.5.2.178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Z., Hu, Y., Liu, W., & Ma, Y. (2015). 小学三年级流动儿童性教育课程效果评价 [Impact of school-based comprehensive sexuality education on grade 3 migrant children’s sexual health knowledge and healthy behavior]. Chinese Journal of School Health, 36(8), 1150–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N., Dai, J., & Gao, J. (2014). 2012中国同性恋调查报告及对同性婚姻合法化的思考 [2012 Report on homosexuality in China and reflections on the legalization of same-sex marriage]. The Chinese Journal of Human Sexuality, 23(1), 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. (2017). 珍爱生命——小学生性健康教育读本 (全十二册) [Cherishing life–sexuality education for primary school students]. Beijing Normal University Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., & Liu, W. (2019a). 基于性知识和性别刻板印象的小学性教育课程效果评价 [Effectiveness of sexuality education curriculum in primary schools based on sexual health knowledge and gender stereotypes]. Chinese Journal of School Health, 40(3), 350–354. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., & Liu, W. (2019b). 小学性健康教育课程对减少艾滋病歧视的效果评价 [Evaluation of the effect of school-based sexuality education in reducing AIDS discrimination in primary school]. Chinese Journal of Health Education, 35(12), 1108–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W., & Su, Y. (2014). School-based primary school sexuality education for migrant children in Beijing. China. Sex Education, 14(5), 568–581. 10.1080/14681811.2014.934801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W., & Yuan, Y. (2017). 我国中小学性教育政策回顾(1984∼2016) [Review of sex education policy in primary and secondary schools in China(1984 ∼ 2016)]. Education and Teaching Research, 31(7), 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J., , Xiao, Z., & , Feng, T. (2017). 元认知:态度与说服研究的新视角 [Metacognition: A new perspective on attitude and persuasion study]. Advances in Psychological Science, 25(5), 866. 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2017.00866 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Storey, A., & Benner, A. (2019). Externalizing behaviors exacerbate the link between discrimination and adolescent health risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(9), 1724–1735. 10.1007/s10964-019-01020-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, W., Turanovic, J. J., Lloyd, K. M., & Pratt, T. C. (2020). The victimization of LGBTQ students at school: A meta-analysis. Journal of School Violence, 19(4), 421–432. 10.1080/15388220.2020.1725530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2021). Major figures on 2020 population census of China. China Statistics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, M. C., , Johnson, K. E., , Russell, S., & , Gobble, T. (2019). Homophobic Bullying and Suicidal Behavior Among US Heterosexual Youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(2), 205–208. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.08.473 31493473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, A., & Rhead, R. (2013). Personal relationships: Changing attitudes towards sex, marriage and parenthood. British Social Attitudes. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat, V. P., Mereish, E. H., Digiovanni, C. D., & Koenig, B. W. (2011). The effects of general and homophobic victimization on adolescents’ psychosocial and educational concerns: The importance of intersecting identities and parent support. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 597–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat, V. P., & Russell, S. T. (2013). Understanding homophobic behavior and its implications for policy and practice. Theory into Practice, 52(4), 264–271. 10.1080/00405841.2013.829729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randall, D. M., & Fernandes, M. F. (1991). The social desirability response bias in ethics research. Journal of Business Ethics, 10(11), 805–817. 10.1007/BF00383696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart, S. J., , Espelage, D. L., & , Bub, K. L. (2020). Longitudinal effects of gendered harassment perpetration and victimization on mental health outcomes in adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(23-24), 5997–6016. 10.1177/0886260517723746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, I. (2000). Social exclusion, absenteeism and sexual minority youth. Support for Learning, 15(1), 13–18. 10.1111/1467-9604.00136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. P., Espelage, D. L., & River, L. (2013). Developmental trends in peer victimization and emotional distress in LGB and heterosexual youth. Pediatrics, 131(3), 423–430. 10.1542/peds.2012-2595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, F. F., & Tsai, Y. M. (1987). Male homosexuality in traditional Chinese literature. Journal of Homosexuality, 14(3–4), 21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, E., Ickes, W., & Ta, V. (2018). Women interact more comfortably and intimately with gay men—but not straight—men after learning their sexual orientation. Psychological Science, 29(2), 288–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S. T., Ryan, C., Toomey, R. B., Diaz, R. M., & Sanchez, J. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent school victimization: Implications for young adult health and adjustment. The Journal of School Health, 81(5), 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S. T., Sinclair, K. O., Poteat, V. P., & Koenig, B. W. (2012). Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 493–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa, Z., Tian, L., & Wang, X. (2021). Evidence for a comprehensive sexuality education intervention that enhances Chinese adolescents’ sexual knowledge and gender awareness and empowers young women. Sex Roles, 85(5–6), 357–370. 10.1007/s11199-021-01223-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santona, A., & Tognasso, G. (2018). Attitudes toward homosexuality in adolescence: An Italian study. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(3), 361–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, K. O., Bauman, S., Poteat, V. P., Koenig, B., & Russell, S. T. (2012). Cyber and bias-based harassment: Associations with academic, substance use, and mental health problems. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(5), 521–523. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. U., & Reidy, D. (2021). Bullying and suicide risk among sexual minority youth in the United States. Preventive Medicine, 153, 106728–106726. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, R., Guo, L., Tang, H., Ye, P., Zhang, S., Xiao, Y., Liu, W., & Liu, C. (2020). Comprehensive sexuality education weakens the effect of in-group bias on trust and fairness. Sex Education, 20(1), 33–942. 10.1080/14681811.2019.1610373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H. C., Ho, J. A., Kumarusamy, R., & Sambasivan, M. (2021). Measuring social desirability bias: Do the full and short versions of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability scale matter? Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 10.1177/15562646211046091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z., Chen, J., & Deng, Y. (2016). 公众对同性恋者的包容度分析———基于 CGSS (2010) 数据的实证分析 [Analysis of public’s tolerance for homosexual—the empirical analysis of CGSS (2010) data]. The Chinese Journal of Human Sexuality, 25(1), 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Y. (2016). LGBTI + students’ school environment research report. http://www.tongyulala.org/uploadfile/2019/0404/20190404055620718.pdf

- UNDP. (2016). Being LGBTI in China: A national survey on social attitudes towards sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. https://www.asia-pacific.undp.org/content/rbap/en/home/library/democratic_governance/hiv_aids/being-lgbti-in-china--a-national-survey-on-social-attitudes-towa.html

- UNESCO. (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education (revised edition) (Report No, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO). https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/reproductive-health/sexual-health/international-technical-guidance-on-sexuality-education.pdf?sfvrsn=10113efc_29&download=true

- van der Star, A., Pachankis, J. E., & Bränström, R. (2021). Country-level structural stigma, school-based and adulthood victimization, and life satisfaction among sexual minority adults: A life course approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., , Wang, Y., , Wang, G., , Wilson, A., , Jin, T., , Zhu, L., , Yu, R., , Wang, S., , Yin, W., , Song, H., , Li, S., , Jia, Q., , Zhang, X., & , Yang, Y. (2021). Structural family factors and bullying at school: A large scale investigation based on a Chinese adolescent sample. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12889-021-12367-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. (2011). 认同而不“出柜”———同性恋者生存现状的调查研究 [Well-identified but not coming out: Contemporary gay minority investigation]. China Agriculture University Journal of Social Science Edition, 28(4), 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Yu, H., Yang, Y., Li, R., Wilson, A., Wang, S., Drescher, J., & Chen, R. (2020). The victim-bully cycle of sexual minority school adolescents in China: Prevalence and the association of mood problems and coping strategies. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, 1–12. 10.1017/S2045796020000918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A. D., Reid, J. D., Garfield, L. D., & Hoy, S. J. (2001). From curiosity to care: Heterosexual student interest in sexual diversity courses. Teaching of Psychology, 28(1), 21–26. 10.1207/S15328023TOP2801_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C., & Liu, W. (2015). 性少数学生心理健康与遭受校园欺凌之间关系研究 [The association between school bullying and mental health of sexual minority students]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23(4), 701–705. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C., & Liu, W. (2019). Coming out in Mainland China: A national survey of LGBTQ students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 16(2), 192–219. 10.1080/19361653.2019.1565795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T. D., Lindsey, S., & Schooler, T. Y. (2000). A model of dual attitudes. Psychological Review, 107(1), 101–126. 10.1037/0033-295X.107.1.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, L. W., & Cullen, J. M. (2001). Reducing college students' homophobia, erotophobia, and conservatism levels through a human sexuality course. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 26(4), 328–333. 10.1080/01614576.2001.11074440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, M. (2014). China still far from accepting gays, lesbians. Retrieved April 6, 2017, from http://www.shanghaidaily.com/feature/China-still-far-from-accepting-gays-lesbians/shdaily.shtml.

- Youn, G. (2018). Attitudinal changes toward homosexuality during the past two decades (1994–2014) in Korea. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(1), 100–116. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1310512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y., Xiao, S., & Xiang, Y. (2010). 同性恋态度量表的构建及其信度、效度检验 [Theory construction of the attitudes toward gay men and Lesbians in Chinese context and assessments in college students]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(02), 174–176. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., , Yan, L., & , Yuan, Y. (2019). Rural-urban migration and mental health of Chinese migrant children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 257, 684–690. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Leng, L., Chen, H., Fang, X., Shu, Z., & Lin, X. (2017). 家庭社会经济地位对流动儿童认知能力的影响:父母教养方式的中介作用 [Parental rearing pattern mediates the association between social economic status and cognitive ability of migrant children]. Chinese Journal of Psychological Development and Education, 33(2), 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. (2007). 古代城市中的同性恋 [Homosexuality in ancient cities in China]. Retrieved February21, 2017, from http://www.zgxkx.org/sex/zgsex/201206/1909.html.

- Zheng, Q., Guo, Y., Wang, Z., Andrasik, F., Kuang, Z., Li, J., Xu, S., & Hu, X. (2022). Exploring Weibo users’ attitudes toward lesbians and gays in Mainland China: A natural language processing and machine learning approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 127, 107021–107013. 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]