Abstract

This paper develops a trauma-informed sex-positive framework as a public health, clinical, and research approach to sexual experience over the life course. The framework centers trauma-informed sex positivity as the linkage for sexual pleasure (along with sexual wellbeing and sexual health) to the social, cultural, and legal concepts of sexual justice. By providing a conceptual distinction of sexual pleasure from sexual wellbeing and sexual health, the framework improves clarity about how these constructs are related as well as provides possibilities for detailed operationalization in public health surveillance and in the new research.

Keywords: Sexual pleasure, sexual wellbeing, sexual health, trauma-informed care, sexual rights

The goal of this paper is to describe a trauma-informed sex-positive approach to sexual pleasure as a significant component of clinical care, in public health practice, and in research related to sexual experiences. Such an approach is needed because sexual pleasure is confusingly conflated with other essential components of sexual experience such as sexual wellbeing and sexual health. Moreover, sexuality experiences that may generate pleasure intersect with personal and structural trauma arising from often rigid cultural traditions and complex social and legal structures that prioritize pleasure for some while limiting or even punishing pleasure for others. These cultural boundaries deeply embed sexual pleasure in gender, in social class, in social privilege—the same structures that create sexual and reproductive health inequities. This intersection of private sexual experience with wellbeing and health outcomes suggests the need for operationalizable frameworks to link sexual pleasure to clinical and public health objectives, goals, and practices (Landers & Kapadia, 2020). As a step toward such a comprehensive approach, we present a framework to address sexual pleasure as an element of sexual experience related to sexual wellbeing and sexual health, linked to sexual justice in a framework of trauma-informed sex-positivity.

Organization of the paper

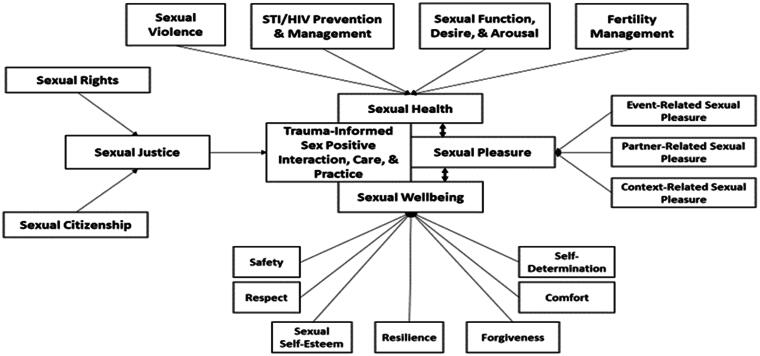

The focus of this paper is to propose a trauma-informed sex-positive approach to sexual pleasure. To avoid over-simplification of the model, we also introduce sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual justice as essential core determinants of sexual experience over the lifespan (see Figure 1). We first introduce the idea that sexual pleasure has both clinical and broad public health implications for addressing the good, bad, and ambiguous diversity of sexual experiences. We then introduce a conceptual framework to identify the principal elements of each concept. The distinction of these related aspects of sexual experience allows more nuanced approaches to operationalization while recognizing their close interconnections. Concepts of sexual justice (including sexual rights and sexual citizenship) identify the social, cultural, and legal structures that continuously shape and define the sexual experience. Finally, we introduce a trauma-informed sex-positive approach as a means of linking sexual justice to sexual pleasure, sexual wellbeing, and sexual health. Examples of trauma-informed, sex-positive approaches are linked to principles of trauma-informed practice and to the specific domains of sexual experience in Table 1 to suggest paths toward more nuanced clinical, public health, and research approaches to sexual experience.

Figure 1.

Framework for trauma-informed sex positive approaches to sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual pleasure.

Table 1.

Matching Sexual Wellbeing, Sexual Health, and Sexual Pleasure With Principles and Practice Behaviors of Trauma-Informed Approaches.

| Trauma informed approach behaviors | Trauma informed approach principle | Sexuality domain |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Sexual wellbeing | ||

|

Safety | Safety/Security |

|

Trust & transparency | Respect |

|

Empowerment, voice, & choice | Sexual self-esteem |

|

Foster post-traumatic healing & growth | Resilience |

|

Foster post-traumatic healing & growth | Forgiveness |

|

Collaboration & mutuality | Comfort |

|

Empowerment, voice, & choice | Self-determination |

| Panel B. Sexual health | ||

|

Screening for trauma | Sexual violence |

|

Knowledge, services, resources | STI/HIV Prevention & Management |

|

Knowledge, services, resources | Sexual Function, Desire & Arousal |

|

Knowledge, services, resource | Fertility management |

| Panel C. Sexual pleasure | ||

|

Knowledge, services, resources | Person-related pleasure |

|

Context-related pleasure | |

|

Events-related pleasure |

A perspective on sexual pleasure—from subjective experience to public health

Sexual pleasure is at or near the essence of subjective sexual experience. From the intense thrill of arousal through the “it feels so good” of orgasm to the heightened self-awareness and metaphysical transformations of sexual ecstasy, the pleasure associated with sexual experience is engrained in day-to-day life but also associated with transcendent emotion and meaning. This broad subjective perspective is included in the definition of sexual pleasure in a recent position paper on sexual pleasure (Ford et al., 2019) and included in the 2019 Mexico City World Congress of Sexual Health (WAS) Declaration on Sexual Pleasure “Sexual pleasure is the physical and/or psychological satisfaction and enjoyment derived from solitary or shared erotic experiences, including thoughts, dreams and autoeroticism.” (World Association for Sexual Health, 2019) This definition of sexual pleasure is thus aligned with subjective sexual wellbeing and health rather than explicitly relevant to public health. Consequently, pleasure may be viewed as a quality of individual experience with potential clinical importance, but outside the public health purview.

The person-centered perspective is expanded, however, by additional dimensions of the WAS Declaration on Sexual Pleasure that carry more evident public health implications: “Sexual pleasure should be exercised within the context of sexual rights, particularly the rights to equality and nondiscrimination, autonomy and bodily integrity, the right to the highest attainable standard of health and freedom of expression.” These caveats in the definition of sexual pleasure show how emotions and bodily sensations of pleasure are linked to public health through a focus on the social and structural determinants of health, relevant in societies and cultures around the world. Accordingly, sexual justice links social and structural determinants of health to sexual pleasure by focusing on elements of sexual experience outside of personal agency and action (Gruskin & Kismodi, 2020). This connection is solidified through the concept of trauma-informed sex-positive approaches to care and practice.

Sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual pleasure in sexual experience

The purpose of this paper is to describe a framework linking trauma-informed sex-positive approaches and sexual pleasure. However, there are at least three reasons for proposing sexual wellbeing and sexual health as additional distinct domains of sexual experience. First, the three concepts are typically conflated. For example, in the widely used World Health Organization (WHO) definition of sexual health, sexual wellbeing is constructed as an undefined outcome of sexual health. Definitions of sexual pleasure likewise reference sexual wellbeing without specifying how the concepts are distinct (World Health Organization, 2020). Second, the conflation of sexual wellbeing, health, and pleasure leads to a lack of specificity in operationalization and measurement of each, where the measurement of one is interpreted as an assessment of all. Among other issues, this leads to an over-emphasis of sexual experience as a set of health challenges requiring professional services and biomedical technology. One highly publicized and debated example centers around hypoactive sexual desire disorder and the pharmaceutical agent flibanserin, where both diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment are broadly contested in terms of implications for sexual health, sexual wellbeing, and sexual pleasure, but without a clear distinction of which—if any—of the domains are most responsive to the pharmaceutical (Anderson & Moffatt, 2018). Third, the distinction of sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual pleasure is important because each requires different approaches in developing evidence-based clinical and public health approaches that could contribute to overall wellbeing and health. The proposed framework thus moves beyond current conceptual imprecision in addressing sexual experience and allows for the inclusion of single-person (often referred to a solo or masturbation sex) and multiple-person (often referred to as partnered sex) pleasure, recognizes the potential for unequal social protections and legal rights (gender identity and sexual orientation are examples), addresses the ubiquity of traumatic sexual experiences that may have lifelong influences on sexual experience, incorporates a perspective on health equity as a global public health target, and is amenable to operationalization in public health, clinical, and research settings (Miller et al., 2015).

Sexual wellbeing

Sexual wellbeing is a summative self-experience of sexuality through cognitive, affective, and bodily assessment of sexual experiences and near-future sexual expectations (Lorimer et al., 2019). Sexual wellbeing captures population trends distinct from sexual health and sexual pleasure, although it is often referred to in definitions of each. Here, we incorporate recent conceptual work by Mitchell et al. (2021) to operationalize sexual wellbeing with a seven-domain model: sexual safety/security; sexual respect; sexual self-esteem; sexual resilience; sexual forgiveness; sexual determination; and sexual comfort. Sexual safety/security refers to sexual experiences of limited threat coupled with actions taken to assuage vulnerability (Alexander & Fannin, 2014). Sexual respect is the perception of positive regard by others for one’s sexual personhood (Huo et al., 2010). Sexual self-esteem refers to affective appraisals of oneself as a sexual being (Bornefeld-Ettmann et al., 2018a; Doyle Zeanah & Schwarz, 1996). Sexual resilience is defined as the maintenance or restoration of equilibrium in response to sexual stress, dysfunctions, adversity, or trauma (Meng et al., 2018). Sexual forgiveness is defined as a process that interrupts patterns of self-blame, self-stigmatization, shame, avoidance, aggression, and revenge (Hall & Fincham, 2005; Worthington et al., 2007). Sexual self-determination refers to the free choice of the sexual partner(s), behaviors, context, and timing without pressure, force, or felt obligation (Sanchez et al., 2005). Sexual comfort refers to the experience of ease in contemplation, communication, and enactments of sexuality and sex (Hensel et al., 2011). Although no widely used measure of sexual wellbeing is in use, these domains are consistent with those summarized by Lorimer et al. (2019) and allow more detailed focus on sexual wellbeing as distinct from sexual health and sexual pleasure.

Sexual health

Our conceptualization of sexual health follows that outlined in the WHO definition of sexual health, with a focus on four domains: sexual violence and sexual violence prevention; prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and human immunodeficiency virus infections (HIV); sexual functions, including desire and arousal; and fertility regulation (Wellings, 2012).

The WHO Working Group to Operationalize Sexual Health (Stephenson et al., 2017) links sexual health to “physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality,” and additionally identifies prevention, support, and care for gender-based violence as a core intervention area. The global public health relevance of sexual health is reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals via consideration of specific areas of sexual health, including adolescent sexual/reproductive health; gender-based violence; STI/HIV; contraception, safe abortion, and infertility; maternal and newborn health; and reproductive cancers, particularly those due to human papillomaviruses (Starrs et al., 2018). Focus on these domains—distinct but related to sexual wellbeing and sexual pleasure—allows a better understanding of the etiology and epidemiology of issues related to sexual health as well as a focused use of available infrastructure and technologies.

Sexual pleasure

Our framework distinguishes sexual pleasure from both sexual wellbeing and sexual health to emphasize the importance of pleasure both as motivation for, and consequence of, sexual experience. The social, psychological, and physiological elements of sexual pleasure as embodied experiences underscore its distinction from sexual wellbeing and sexual health as evidenced by the inclusion of sexual pleasure in many perspectives of sexual wellbeing and in the WHO definition of sexual health (Syme et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2020). From a public health perspective, sexual pleasure, sexual health, and sexual rights form a “perfect triangle” of elements contributing to sexual and overall wellbeing (Gruskin et al., 2019).

Our theoretical perspective considers sexual pleasure as an embodied element of everyday sexual experience that generates meaning for the person(s) involved but also reflects larger social and cultural meanings (Jackson & Scott, 2007). “Embodiment” here is conceptualized as the ways individual bodies create sensations associated with pleasure and other affective sexual responses (Tolman et al., 2014). Gender (Tolman et al., 2014), sexual agency and entitlement to pleasure (Chmielewski et al., 2020), and sexual geographies of bodies and modesty expectations for body display and movement (Reddy-Best & Choi, 2020; Sehlikoglu, 2016); are all influences on the sexual embodiment. An embodiment perspective facilitates consideration of how diverse bodies themselves influence the perceptions and experiences of sexual pleasure (Fortenberry & Hensel, 2021). For example, people with gender dysphoria may reject pleasure associated with solo or partnered sex because of the specific conformation of their genitals even in the context of intense sexual arousal (Doorduin & van Berlo, 2014). Or, consider how neurodiverse people with the autism spectrum may struggle to interpret sexual attractions as pleasurable even when experiencing pleasurable sensations through touch (Sala et al., 2020). As a final example, consider how people with a common spinal cord condition such as spina bifida report sexual pleasure even in the context of impaired genital sensation and anorgasmia (Streur et al., 2021).

Accordingly, we isolate three dimensions of phenomenology of sexual pleasure to describe person-centered, everyday meaning-making of sexual experience: person-related pleasure; context-related pleasure; and event-related pleasure.

Person-related pleasure refers to whether a sexual experience involves a single person or multiple persons. Single-person and multiple-person sex are related but distinct forms of sexual experience (Goldey et al., 2016). In particular, multiple-person sex adds intersubjective considerations for the coordination of each partner’s experience of, and contribution to, pleasure. Multiple person sex and sexual pleasure are especially relevant to a host of social, legal, and public health issues: the social status of marriage and use of latex barriers for STI/HIV prevention, to name only two examples. If the phenomenology of sex is considered a series of questions resolved in the process of sex, person-related pleasure depends on answers to “who” questions (e.g., one person alone/with someone else; this person/not someone else; known others/unknown others; Goldey et al., 2016).

Context-related pleasure refers to the environment in which sex is acceptable/unacceptable to the person(s) for whom sex is a possibility (Willis et al., 2020). Key questions about the “wantedness” of specific sexual experiences arise when considering context-related elements, such as “if/where/when” sex occurs (Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2007). Sexual events such as first partnered coitus retain a substantial degree of personal and social significance associated with pleasure-related expectations and experiences, especially for young people (Higgins et al., 2010). These considerations extend beyond issues of consent and may include (for example) whether a person wants sex during menses (even though they desire sex), or engage in certain behaviors in certain locations (e.g., because of associations with past pleasurable experiences) but not another (e.g., because of traumatic triggering by past experiences; Spencer & Vencill, 2017).

Event-related pleasure addresses situational attributes such as the “what” of sex (e.g., greater arousal/lesser arousal; focus on self-pleasure/focus on partner pleasure; inclusion of only familiar behaviors/introduction of new behaviors (Herbenick et al., 2019; Willis et al., 2020). A perspective on event-related pleasure—distinct from the pleasure that is responsive to partners and to context—broadens understanding of pleasure as an embodied social practice closely linked to sexual wellbeing and sexual health (Hargons et al., 2018; Hensel et al., 2012; Rubin et al., 2019).

Sexual justice as a defining influence on sexual experience

Broad efforts—including those of public health entities—to support full and equal access to sexual rights and distributive and restorative justice are central to the foundation of sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual pleasure (McGlynn et al., 2012; Starrs et al., 2018). Sexual rights summarize the social, cultural, and legal efforts to create and maintain equitable sexual and reproductive experiences. Challenges to sexual rights are often based on historical restrictions of sexual citizenship based on ethnicity, sex, and sexual and gender identity. Sexual citizenship refers to membership in local, regional, and national public structures that is unmodified by one’s gender, gender identity, and expression, or sexual identity and expression (Corboz, 2009). For example, sexuality and gender-related identities are often used to disenfranchise some people from equal access to military service, marriage, and adoptive family formation. Sexual citizenship allows explicit understanding of how dominant sexual, racial, and class structures erase or suppress the full social and civic participation of some groups (Richardson, 2017). Sexual justice thus provides a platform for the free exercise of sexual rights and sexual citizenship that supports the prevention and healing potentials of trauma-informed sex-positivity approaches to sexual pleasure.

Trauma-informed sex-positive approaches to sexual pleasure

Our framework centers on trauma-informed sex-positive approaches as the critical link between sexual justice, trauma experiences, and sexual pleasure (Table 1). Trauma and sexual pleasure are both learned interpretations and embodied responses, with trauma often associated with harmful effects on sexuality and sexual experience (Lorvick et al., 2012). The unifying element in our framework—trauma-informed sex positivity—is inextricably linked to the core concepts of sexual experience: sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual pleasure. Additionally, trauma-informed sex positivity enables the linkage of sexual justice, sexual rights, and sexual citizenship to the key elements of sexual experiences. A trauma-informed sex-positive approach emphasizes sexuality and sexual experience as assets that contribute to overall health and wellbeing, despite previous experiences of adversity or trauma.

Sex positivity

Sex positivity is central to an integrated understanding of sexual pleasure by anchoring supportive and therapeutic approaches to the many traumatic (sexual and otherwise) experiences that resonate through the life course and diminish the quality of sexual experiences (Bird et al., 2014; O’Loughlin & Brotto, 2020; O’Loughlin et al., 2020; Rellini et al., 2009). Sex positivity is a well-established but variably defined concept focused on the recognition of sexuality as potentially enhancing expressions of body diversity, relationships, safety, and perceptions about sexuality itself (Queen & Comella, 2008). Sex positivity may be contrasted to “sex-negativity” based on definitions of acceptable sexuality that stigmatizes, shames, and punishes sexual expression outside of rigidly defined social boundaries (Ivanski & Kohut, 2017). Sex negativity often directly generates the trauma that adversely affects sexual experiences. Fahs (2014) emphasizes the importance of sex positivity based simultaneously on freedom to explore sexuality and sexual diversity as well as freedom from gender-, class-, and race-based social mandates (thus linking sex positivity to concepts of sexual justice, rights, and citizenship). Sex positivity thus allows for more effective reparative and healing interventions based on intersections implied by diverse races and ethnicities, sexualities, gender identities and expressions, and sexual behaviors (Hogben et al., 2015; Mosher, 2017).

Trauma-informed approaches to sexual pleasure

Trauma is defined as resulting from “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being” (Kessler et al., 2017). Our perspective on trauma also extends—via attention to issues of sexual justice—to recognize and respond to the sexual influences of historical and structural trauma such as colonialism and racism (Andermahr, 2015). This recognition is key to adapting to critical differences in perspectives on sexuality both within and between nations and communities around the world (Richardson, 2018).

A broad clinical and public health research literature identifies general negative effects and sexual effects of specific kinds of trauma and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as maltreatment, separation from caregivers, and poverty (Brown & Shillington, 2017; Cicchetti, 2013; Felitti et al., 1998). These experiences are common and tend to co-occur (Anda et al., 1999; Dube et al., 2003; Felitti et al., 1998). For example, 70.4% of respondents to the WHO World Mental Health Survey reported experiencing lifetime traumas, with the average number of traumas being 3.2 (Kessler et al., 2017). In addition, data from the 2011–2012 National Survey of Children’s Health revealed that 48% of youth report experiencing some kind of ACE (e.g., living with a parent with mental health problems, violence in the home or neighborhood; Bethell et al., 2014) while 61.6% of adults in a nationally representative sample reported experiencing at least one ACE and 24.6% reported experiencing three or more ACEs (Merrick et al., 2018).

Related to sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and to sexual pleasure, trauma often negatively impacts healthy relationships (Colman & Widom, 2004; DiLillo et al., 2007) and is associated with self-blame, shame, guilt, negative body image, negative sexual self-esteem, and sexual health risk behaviors (Cook et al., 2005; Feiring et al., 2009; Lemieux & Byers, 2008; Meston et al., 2006; Putnam, 2003; Reissing et al., 2004; Roemmele & Messman-Moore, 2011; Senn et al., 2008; Van Bruggen et al., 2006; Wenninger & Heiman, 1998; Wilson & Widom, 2011). Low sexual satisfaction, decreased sexual pleasure, and impaired sexual function are all outcomes of both childhood and adult sexual trauma (DiMauro et al., 2018; Bornefeld-Ettmann et al., 2018b). However, not all overwhelming or life-threatening experiences create trauma responses; positive adaptations are possible and can be fostered by supportive communities along with healing public health and clinical services (Infurna & Jayawickreme, 2019). It is both the commonality of trauma and the uniqueness of a person’s response that requires professionals to adopt a trauma-informed approach to understanding and supporting sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual pleasure.

At its core, trauma-informed approaches are an organizational change process grounded in the realization of the high prevalence of trauma; recognition of how trauma affects all individuals and communities involved; belief in the resilience of individuals and communities; and proactive use of evidence-based practices (Hales et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2014). Trauma-informed approaches refocus clinical and public health interventions away from asking “What is wrong with you?” toward “What has happened to you?”(Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). In this way, a person’s or a community’s experiences do not define who they are, and it is possible to more clearly assess current stressors and environmental influences, as well as resilience and protective factors that might mitigate the risk of negative outcomes (Racine et al., 2020). As it relates to sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual pleasure, trauma-informed approaches provide a map and toolbox for professionals to best support the individuals and communities with whom they work. Talking about the sexual aspects of one’s life can be difficult—for clients and professionals—and the principles of trauma-informed care outline an approach to communication that supports direct discussions about sex and sexuality. Furthermore, the professional relationship can serve as a model of a healthy relationship for individuals who struggle to build these within their personal lives, and the professional relationship can be a space for one to reflect on assets and resources in their life as sources of strength.

Several key principles of trauma-informed care have been identified, and while there is some variability around the specific terminology used worldwide, there is broad consensus around some fundamental principles: safety, trust and transparency, collaboration and mutuality, and empowerment, choice, and voice (Bowen & Murshid, 2016; Hales et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2014). Additionally, we propose that screening for trauma, posttraumatic growth and healing, and access to knowledge, services, and resources are principles with explicit relevance to our consideration of trauma-informed sex-positive care and practice (see Table 1). Safety is the creation of an institutional and interpersonal environment that promotes emotional and physical safety, minimizes threat, re-traumatization, and additional trauma experiences. Trust and transparency require that procedures, policies, and decisions be carried out with transparency in all interactions among and between professionals as well as with clients. Collaboration and mutuality facilitate trust, create a sense of safety, and empower relationships—personal and professional—to be a source of healing, shared decision making, and powerful meaning-making. The principle of empowerment, choice, and voice centers shared power with clients and highlights that trauma is a unique experience for everyone and that the best supports will be individualized and focused on promoting a person’s strengths, rather than what may be perceived as a deficit. Screening allows for the elicitation of trauma experiences and the creation of responsive environments. Access to knowledge, services, and resources addresses institutional commitment to equitable access to evidence-based programs. Post-traumatic healing and growth allow space for therapeutic engagement by dismantling stereotypes of victims and supporting each person’s potential and capacity (Slade et al., 2019; Taube & Mussap, 2020). Recognition of trauma as experiences of communities as well as individuals allows trauma-informed public health approaches that focus on historical discrimination and violence related to sexuality and gender (Loomis et al., 2019). This can create opportunities for specific types of public health engagement with communities: the long shadow of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic is an example of differential effects of trauma on the sexual experiences of diverse communities (Hussein, 2020) .

The pervasive negative effects of diverse trauma experiences on sex and sexuality suggest a need for the addition of sex-positivity into trauma-informed approaches (Byers & Glenn, 2012; Elliott et al., 2004; Koss, 1993; Neville & Heppner, 1999; Ullman et al., 2007). Sex positivity humanizes sexual experiences—both positive and negative—and emphasizes direct communication, nonjudgmental attitudes, and interactions, and explicitly recognizes intersections with other marginalized identities at all levels of social organization (Alexander, 2019; Williams et al., 2013).

Summary and discussion

Our intention in this paper is to outline a broad approach to sexual experience, although with a focus on sexual pleasure. The distinction of three key dimensions of sexual experience—sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual pleasure—allows a more detailed understanding of the unique elements of each. By specifying the unique domains of the element, we hope to move beyond the limitations of overly broad definitions, of imprecise operationalization, by fragmented data collection, and by a sense that sexual experience—especially as marked by sexual pleasure—is outside the public health purview. Fortunately, as represented in the WAS Declaration on Sexual Pleasure, this perspective is changing. Importantly as well, linking sexual experiences to sexual rights, sexual citizenship, and sexual justice demonstrates the importance of cultural, social, and legal structures needed to support healthy sexual experience and address sexual wellbeing, sexual health, and sexual pleasure.

The heart of our proposed public health approach to sexual experience is our call for trauma-informed sex-positive approaches to care and practice. From our perspective, both trauma-informed approaches and sex-positivity are key to comprehensive clinical and public health approaches to the ubiquitous experiences of trauma without adding to the stigmatization and victimization of both individuals and communities. The inclusion of trauma-informed sex-positive approaches as standards for clinical and public health work focuses on the social determinants of inequities in wellbeing and health that may lead to mitigation of existing trauma as well as prevention of new traumas. Particularly in moving forward with the inclusion of sexual pleasure as defined element of clinical and public health practice, our comprehensive, multi-dimensional approach also emphasizes the healing possibilities of clinical and public health practice by outlining approaches to operationalizing key person, context, and event-related elements of sexual pleasure that will support surveillance, interventions, and new research.

This requires tremendous social and political will and significant investment to recast our clinical and public health approaches to sexual experience, including sexual pleasure. However, huge benefits to personal and public health and wellbeing might be expected (Bowen & Murshid, 2016).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Alexander, A. A. (2019). Sex for all: Sex positivity and intersectionality in clinical and counseling psychology. Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships, 6(1), 49–72. 10.1353/bsr.2019.0015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K. A., & Fannin, E. F. (2014). Sexual safety and sexual security among young Black women who have sex with women and men. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 43(4), 509–519. 10.1111/1552-6909.12461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda, R. F., Croft, J. B., Felitti, V. J., Nordenberg, D., Giles, W. H., Williamson, D. F., & Giovino, G. A. (1999). Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA, 282(17), 1652–1658. 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andermahr, S. (2015). Decolonizing trauma studies: “Trauma and postcolonialism”—Introduction. Humanities, 4(4), 500–505. 10.3390/h4040500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R., & Moffatt, C. E. (2018). Ignorance is not bliss: If we don’t understand hypoactive sexual desire disorder, how can flibanserin treat it? Commentary. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(3), 273–283. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell, C. D., Newacheck, P., Hawes, E., & Halfon, N. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: Assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Affairs, 33(12), 2106–2115. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird, E. R., Seehuus, M., Clifton, J., & Rellini, A. H. (2014). Dissociation during sex and sexual arousal in women with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(5), 953–964. 10.1007/s10508-013-0191-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornefeld-Ettmann, P., Steil, R., Höfling, V., Weßlau, C., Lieberz, K. A., Rausch, S., Priebe, K., Fydrich, T., & Müller-Engelmann, M. (2018a). Validation of the German version of the Sexual Self-Esteem Inventory for Women and its application in a sample of sexually and physically abused women. Sex Roles, 79(1–2), 109–122. 10.1007/s11199-017-0849-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bornefeld-Ettmann, P., Steil, R., Lieberz, K. A., Bohus, M., Rausch, S., Herzog, J., Priebe, K., Fydrich, T., & Müller-Engelmann, M. (2018b). Sexual functioning after childhood abuse: The influence of post-traumatic stress disorder and trauma exposure. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(4), 529–538. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, E. A., & Murshid, N. S. (2016). Trauma-informed social policy: A conceptual framework for policy analysis and advocacy. American Journal of Public Health, 106(2), 223–229. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. M., & Shillington, A. M. (2017). Childhood adversity and the risk of substance use and delinquency: The role of protective adult relationships. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 211–221. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers, E. S., & Glenn, S. A. (2012). Gender differences in cognitive and affective responses to sexual coercion. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(5), 827–845. 10.1177/0886260511423250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, J. F., Bowman, C. P., & Tolman, D. L. (2020). Pathways to pleasure and protection: Exploring embodiment, desire, and entitlement to pleasure as predictors of black and white young women’s sexual agency. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(3), 307–322. 10.1177/0361684320917395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, D. (2013). Annual research review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children-past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(4), 402–422. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman, R. A., & Widom, C. S. (2004). Childhood abuse and neglect and adult intimate relationships: A prospective study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(11), 1133–1151. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M., Cloitre, M., DeRosa, R., Hubbard, R., Kagan, R., Liautaud, J., Mallah, K., Olafson, E., & van der Kolk, B. (2005). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 390–398. 10.3928/00485713-20050501-05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corboz, J. (2009). Sexuality, citizenship and sexual rights. Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/31022755/Sexuality__citizenship_and_sexual_rights.pdf

- DiLillo, D., Lewis, T., & Loreto-Colgan, A. D. (2007). Child maltreatment history and subsequent romantic relationships. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 15(1), 19–36. 10.1300/J146v15n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DiMauro, J., Renshaw, K. D., & Blais, R. K. (2018). Sexual vs. non-sexual trauma, sexual satisfaction and function, and mental health in female veterans. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 19(4), 403–416. 10.1080/15299732.2018.1451975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorduin, T., & van Berlo, W. (2014). Trans people’s experience of sexuality in the Netherlands: A pilot study. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(5), 654–672. 10.1080/00918369.2014.865482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle Zeanah, P., & Schwarz, J. C. (1996). Reliability and validity of the sexual self-esteem inventory for women. Assessment, 3(1), 1–15. 10.1177/107319119600300101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dube, S. R., Felitti, V. J., Dong, M., Chapman, D. P., Giles, W. H., & Anda, R. F. (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics, 111(3), 564–572. 10.1542/peds.111.3.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, D. M., Mok, D. S., & Briere, J. (2004). Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(3), 203–211. 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029263.11104.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahs, B. (2014). ‘Freedom to’ and ‘freedom from’: A new vision for sex-positive politics. Sexualities, 17(3), 267–290. 10.1177/1363460713516334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring, C., Simon, V. A., & Cleland, C. M. (2009). Childhood sexual abuse, stigmatization, internalizing symptoms, and the development of sexual difficulties and dating aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 127–137. 10.1037/a0013475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J. V., Corona Vargas, E., Finotelli, I., Jr., Fortenberry, J. D., Kismödi, E., Philpott, A., Rubio-Aurioles, E., & Coleman, E. (2019). Why pleasure matters: Its global relevance for sexual health, sexual rights and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 217–230. 10.1080/19317611.2019.1654587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry, J. D., & Hensel, D. J. (2021). Sexual pleasure in adolescence: A developmental sexual embodiment perspective. In VanderLaan D. P. & Wong W. I. (Eds.), Gender and sexuality development: Contemporary theory and research. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Goldey, K. L., Posh, A. R., Bell, S. N., & van Anders, S. M. (2016). Defining pleasure: A focus group study of solitary and partnered sexual pleasure in queer and heterosexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(8), 2137–2154. 10.1007/s10508-016-0704-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin, S., & Kismodi, E. (2020). A call for (renewed) commitment to sexual health, sexual rights, and sexual pleasure: A matter of health and well-being. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), 159–160. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin, S., Yadav, V., Castellanos-Usigli, A., Khizanishvili, G., & Kismödi, E. (2019). Sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure: Meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(1), 1593787. 10.1080/26410397.2019.1593787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales, T., Kusmaul, N., & Nochajski, T. (2017). Exploring the dimensionality of trauma-informed care: Implications for theory and practice. Human Service Organizations, 41(3), 317–325. 10.1080/23303131.2016.1268988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (2005). Self–forgiveness: The stepchild of forgiveness research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(5), 621–637. 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.5.621 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hargons, C. N., Mosley, D. V., Meiller, C., Stuck, J., Kirkpatrick, B., Adams, C., & Angyal, B. (2018). “It feels so good”: Pleasure in last sexual encounter narratives of Black university students. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(2), 103–127. 10.1177/0095798417749400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel, D. J., Fortenberry, J. D., O’Sullivan, L. F., & Orr, D. P. (2011). The developmental association of sexual self-concept with sexual behavior among adolescent women. Journal of Adolescence, 34(4), 675–684. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel, D. J., Stupiansky, N. W., Herbenick, D., Dodge, B., & Reece, M. (2012). Sexual Pleasure during condom-protected vaginal sex among heterosexual men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(5), 1272–1276. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02700.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbenick, D., Bartelt, E., Fu, T.-C., Paul, B., Gradus, R., Bauer, J., & Jones, R. (2019). Feeling scared during sex: Findings from a US probability sample of women and men ages 14 to 60. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 45(5), 424–439. 10.1080/0092623X.2018.1549634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. A., Trussell, J., Moore, N. B., & Davidson, J. K. (2010). Virginity lost, satisfaction gained? Physiological and psychological sexual satisfaction at heterosexual debut. Journal of Sex Research, 47(4), 384–394. 10.1080/00224491003774792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogben, M., Ford, J., Becasen, J. S., & Brown, K. F. (2015). A systematic review of sexual health interventions for adults: Narrative evidence. Journal of Sex Research, 52(4), 444–469. 10.1080/00224499.2014.973100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y. J., Binning, K. R., & Molina, L. E. (2010). Testing an integrative model of respect: Implications for social engagement and well-being. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(2), 200–212. 10.1177/0146167209356787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, J. (2020). COVID-19: What implications for sexual and reproductive health and rights globally?. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 28(1), 10.1080/26410397.2020.1746065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infurna, F. J., & Jayawickreme, E. (2019). Fixing the growth illusion: New directions for research in resilience and posttraumatic growth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(2), 152–158. 10.1177/0963721419827017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanski, C., & Kohut, T. (2017). Exploring definitions of sex positivity through thematic analysis. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 26(3), 216–225. https:// 10.3138/cjhs.2017-0017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S., & Scott, S. (2007). Faking like a woman? Towards an interpretive theorization of sexual pleasure. Body & Society, 13(2), 95–116. 10.1177/1357034X07077777 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., Degenhardt, L., de Girolamo, G., Dinolova, R. V., Ferry, F., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, S., Lepine, J.-P., Levinson, D., … Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(5), 1353383. 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss, M. P. (1993). Rape: Scope, impact, interventions, and public policy responses. American Psychologist, 48(10), 1062–1069. 10.1037/0003-066X.48.10.1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers, S., & Kapadia, F. (2020). The public health of pleasure: Going beyond disease prevention. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), 140–141. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux, S. R., & Byers, E. S. (2008). The sexual well-being of women who have experienced child sexual abuse. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(2), 126–144. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00418.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis, B., Epstein, K., Dauria, E. F., & Dolce, L. (2019). Implementing a trauma-informed public health system in San Francisco, California. Health Education & Behavior, 46(2), 251–259. 10.1177/1090198118806942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer, K., DeAmicis, L., Dalrymple, J., Frankis, J., Jackson, L., Lorgelly, P., McMillan, L., & Ross, J. (2019). A rapid review of sexual wellbeing definitions and measures: Should we now include sexual wellbeing freedom? Journal of Sex Research, 56(7), 843–853. 10.1080/00224499.2019.1635565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorvick, J., Bourgois, P., Wenger, L. D., Arreola, S. G., Lutnick, A., Wechsberg, W. M., & Kral, A. H. (2012). Sexual pleasure and sexual risk among women who use methamphetamine: A mixed methods study. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 23(5), 385–392. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn, C., Westmarland, N., & Godden, N. (2012). ‘I just wanted him to hear me’: Sexual violence and the possibilities of restorative justice. Journal of Law and Society, 39(2), 213–240. 10.1111/j.1467-6478.2012.00579.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X., Fleury, M.-J., Xiang, Y.-T., Li, M., & D’Arcy, C. (2018). Resilience and protective factors among people with a history of child maltreatment: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(5), 453–475. 10.1007/s00127-018-1485-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1038–1044. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston, C. M., Rellini, A. H., & Heiman, J. R. (2006). Women’s history of sexual abuse, their sexuality, and sexual self-schemas. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 229–236. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. M., Kismödi, E., Cottingham, J., & Gruskin, S. (2015). Sexual rights as human rights: A guide to authoritative sources and principles for applying human rights to sexuality and sexual health. Reproductive Health Matters, 23(46), 16–30. 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, K., Lewis, R., O’Sullivan, L. F., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2021). What is sexual wellbeing, and why does it matter for Public Health? A paradigm shift for public health inquiry and intervention in sexuality. Lancet Public Health. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher, C. M. (2017). Historical perspectives of sex positivity: Contributing to a new paradigm within counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(4), 487–503. 10.1177/0011000017713755 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neville, H. A., & Heppner, M. J. (1999). Contextualizing rape: Reviewing sequelae and proposing a culturally inclusive ecological model of sexual assault recovery. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 8(1), 41–62. 10.1016/S0962-1849(99)80010-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin, J. I., & Brotto, L. A. (2020). Women’s sexual desire, trauma exposure, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(3), 238–247. 10.1002/jts.22485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin, J. I., Rellini, A. H., & Brotto, L. A. (2020). How does childhood trauma impact women’s sexual desire? Role of depression, stress, and cortisol. Journal of Sex Research, 57(7), 836–847. 10.1080/00224499.2019.1693490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Z. D., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (2007). Conceptualizing the “wantedness” of women’s consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences: Implications for how women label their experiences with rape. Journal of Sex Research, 44(1), 72–88. 10.1080/00224490709336794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, F. W. (2003). Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(3), 269–278. 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queen, C., & Comella, L. (2008). The necessary revolution: Sex-positive feminism in the post-Barnard era. The Communication Review, 11(3), 274–291. 10.1080/10714420802306783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Racine, N., Killam, T., & Madigan, S. (2020). Trauma-informed care as a universal precaution: Beyond the adverse childhood experiences questionnaire. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(1), 5–6. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy-Best, K. L., & Choi, E. (2020). “Male hair cannot extend below plane of the shoulder” and “no cross dressing”: Critical queer analysis of high school dress codes in the United States. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(9), 1290–1340. 10.1080/00918369.2019.1585730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissing, E. D., Binik, Y. M., Khalifé, S., Cohen, D., & Amsel, R. (2004). Vaginal spasm, pain, and behavior: An empirical investigation of the diagnosis of vaginismus. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(1), 5–17. 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000007458.32852.c8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellini, A. H., Hamilton, L. D., Delville, Y., & Meston, C. M. (2009). The cortisol response during physiological sexual arousal in adult women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(6), 557–565. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2010-00260-010&site=ehost-live 10.1002/jts.20458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D. (2017). Rethinking sexual citizenship. Sociology, 51(2), 208–224. 10.1177/0038038515609024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D. (2018). Sexuality and citizenship. Sexualities, 21(8), 1256–1260. 10.1177/1363460718770450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roemmele, M., & Messman-Moore, T. L. (2011). Child abuse, early maladaptive schemas, and risky sexual behavior in college women. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 20(3), 264–283. 10.1080/10538712.2011.575445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, J. D., Conley, T. D., Klein, V., Liu, J., Lehane, C. M., & Dammeyer, J. (2019). A cross-national examination of sexual desire: The roles of ‘gendered cultural scripts’ and ‘sexual pleasure’ in predicting heterosexual women’s desire for sex. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109502. 10.1016/j.paid.2019.07.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sala, G., Pecora, L., Hooley, M., & Stokes, M. A. (2020). As diverse as the spectrum itself: Trends in sexuality, gender and autism. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 7(2), 59–68. 10.1007/s40474-020-00190-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, D. T., Crocker, J., & Boike, K. R. (2005). Doing gender in the bedroom: Investing in gender norms and the sexual experience. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(10), 1445–1455. 10.1177/0146167205277333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehlikoglu, S. (2016). Exercising in comfort: Islamicate culture of mahremiyet in everyday Istanbul. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 12(2), 143–165. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/625051. 10.1215/15525864-3507606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senn, T. E., Carey, M. P., & Vanable, P. A. (2008). Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: Evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(5), 711–735. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M., Rennick-Egglestone, S., Blackie, L., Llewellyn-Beardsley, J., Franklin, D., Hui, A., Thornicroft, G., McGranahan, R., Pollock, K., Priebe, S., Ramsay, A., Roe, D., & Deakin, E. (2019). Post-traumatic growth in mental health recovery: Qualitative study of narratives. BMJ Open, 9(6), e029342. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, K. G., & Vencill, J. A. (2017). Body beyond: A pleasure-based, sex positive group therapy curriculum for transfeminine adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(4), 392–402. 10.1037/sgd0000248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starrs, A. M., Ezeh, A. C., Barker, G., Basu, A., Bertrand, J. T., Blum, R., Coll-Seck, A. M., Grover, A., Laski, L., Roa, M., Sathar, Z. A., Say, L., Serour, G. I., Singh, S., Stenberg, K., Temmerman, M., Biddlecom, A., Popinchalk, A., Summers, C., & Ashford, L. S. (2018). Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: Report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. Lancet, 391(10140), 2642–2692. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30293-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, R., Gonsalves, L., Askew, I., & Say, L. (2017). Detangling and detailing sexual health in the SDG era. Lancet, 390(10099), 1014–1015. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32294-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streur, C. S., Corona, L., Smith, J. E., Lin, M., Wiener, J. S., & Wittmann, D. A. (2021). Sexual function of men and women with spina bifida: A scoping literature review. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 9(2), 244–266. 10.1016/j.sxmr.2020.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

- Syme, M. L., Cohn, T. J., Stoffregen, S., Kaempfe, H., Schippers, D. (2019). “At my age …”: Defining sexual wellness in mid- and later life. Journal of Sex Research, 56(7), 832–842. 10.1080/00224499.2018.1456510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taube, L. N., & Mussap, A. J. (2020). Growth from adversity in trans and gender diverse people of color. International Journal of Transgender Health. Advance online publication. 10.1080/26895269.2020.1777615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman, D. L., Bowman, C. P., & Fahs, B. (2014). Sexuality and embodiment. In Tolman D. L., Diamond L. M., Bauermeister J. A., George W. H., Pfaus J. G., & Ward L. M. (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology, Vol. 1: Person-based approaches (pp. 759–804). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, S. E., Townsend, S. M., Filipas, H. H., & Starzynski, L. L. (2007). Structural models of the relations of assault severity, social support, avoidance coping, self-blame, and PTSD among sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(1), 23–37. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00328.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bruggen, L. K., Runtz, M. G., & Kadlec, H. (2006). Sexual revictimization: The role of sexual self-esteem and dysfunctional sexual behaviors. Child Maltreatment, 11(2), 131–145. 10.1177/1077559505285780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellings, K. (2012). Sexual health: Theoretical perspectives. In: Wellings K., Mitchell K., & Collumbien M. (Eds.), Sexual health: A public health perspective. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wenninger, K., & Heiman, J. R. (1998). Relating body image to psychological and sexual functioning in child sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11(3), 543–562. 10.1023/A:1024408830159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. J., Prior, E., & Wegner, J. (2013). Resolving social problems associated with sexuality: Can a “sex-positive” approach help? Social Work, 58(3), 273–276. 10.1093/sw/swt024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis, M., Fu, T.-C., Jozkowski, K. N., Dodge, B., & Herbenick, D. (2020). Associations between sexual precedent and sexual compliance: An event-level examination. Journal of American College Health. Advance online publication. 10.1080/07448481.2020.1726928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, H. W., & Widom, C. S. (2011). Pathways from childhood abuse and neglect to HIV-risk sexual behavior in middle adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(2), 236–246. 10.1037/a0022915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M. R., Green, S. A., Nochajski, T. H., Mendel, W. E., & Kusmaul, N. S. (2014). ‘We’re civil servants’: The status of trauma-informed care in the community. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(1), 111–120. 10.1080/01488376.2013.845131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Association for Sexual Health . (2019). Mexico City World Congress of Sexual Health Declaration on Sexual Pleasure. https://worldsexualhealth.net/declaration-on-sexual-pleasure/

- World Health Organization . (2020). Defining Sexual Health. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/sh_definitions/en/

- Worthington, E. L., Witvliet, C. V. O., Pietrini, P., & Miller, A. J. (2007). Forgiveness, health, and well-being: A review of evidence for emotional versus decisional forgiveness, dispositional forgivingness, and reduced unforgiveness. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(4), 291–302. 10.1007/s10865-007-9105-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]