Abstract

Despite its relationship with several development issues and sexual health, menstrual health and hygiene management among adolescents have until recently been ignored by practitioners and researchers. This paper is a systematic review of existing literature and argues that menstrual health and hygiene management is a human rights issue. 28,745 articles were screened, with 84 articles included in the full-text review and quality assessment. The results indicate that using a cross-cutting, human rights framework to address inadequate menstrual health and hygiene management is fundamental to promoting menstrual health and hygiene management with dignity among girls and women across the globe.

Keywords: Menstrual health and hygiene management, menstrual hygiene management, adolescent girls, human rights

Introduction

Menstruation is a natural, monthly occurrence for women and girls of reproductive age. Beginning sometime in adolescence, menarche—the initiation of menstruation—is an important phase for an adolescent girl, signaling her transition into puberty and womanhood. After reaching menarche, there is a need to ensure adequate menstrual health and hygiene management (MHHM) for adolescent girls and women, so that they can fully participate in daily activities. Adequate menstrual hygiene management is defined as the “use of clean menstrual management material to absorb or collect blood that can be changed in privacy as often as necessary for the duration of the menstruation period, using soap and water for washing the body as required and having access to facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials” (Sommer & Sahin, 2013; WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme, 2012). The larger concept of menstrual health and hygiene is defined as menstrual hygiene management in conjunction with the “broader systematic factors that link menstruation to health, well-being, gender equality, education, equity, empowerment, and rights” (WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme, 2012). As the definition of adequate menstrual hygiene management excludes the systematic factors that lead to menstruation-related violations of human rights, adequate MHHM must combine the two concepts. While not seen in the literature, the authors propose using a definition of adequate MHHM that encompasses both the access to and use of clean menstrual management material, facilities for disposal of the materials, and soap and water for washing the body, as well as the living free of the social norms and taboos that hinder access and use and limit knowledge and empowerment (Geertz, 2016; UNICEF, 2019). Note, however, that as this definition is not institutionalized, the definition of menstrual hygiene management is used as a proxy for assessing articles.

Despite being a normal, biological process, many adolescent girls and women are unable to practice adequate MHHM. Literature across low- and middle-income countries demonstrates that ∼50% of girls and women practice inadequate MHHM because of reasons beyond their control, such as social restrictions, lack of knowledge about menstruation, and lack of menstrual hygiene products and facilities (Hennegan & Montgomery, 2016; Mahon & Fernandes, 2010). Adolescent girls and women being unable to adequately practice MHHM have far-reaching negative impacts on their lives, such as mobility restrictions, restrictions on attendance at school and community gatherings, compromised safety, and additional stress and anxiety (UNICEF, 2019). When their basic MHHM needs go unmet, adolescent girls and women are denied their rights to manage their menstrual cycle in a dignified, healthy way (UNICEF, 2019).

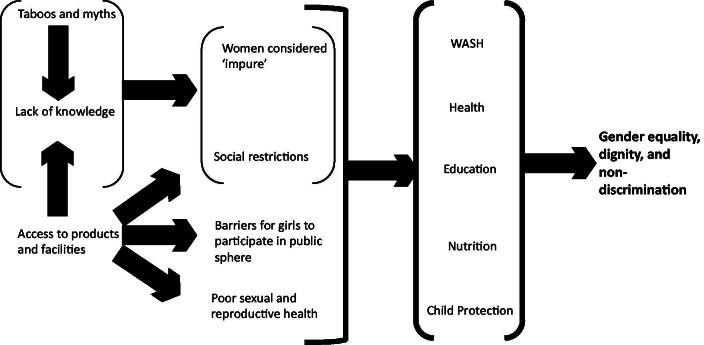

As MHHM encompasses a significant portion of adolescent girls’ and women’s daily lives, inadequate MHHM negatively impacts their health, education, nutrition, safety, and hygiene, making MHHM a human rights issue (Mahon & Fernandes, 2010; Sommer et al., 2015; Sumpter & Torondel, 2013; UNDP, 2015; UNICEF, 2015). Inadequate MHHM has implications for several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 3: good health; SDG 4: quality education; SDG 5: gender equality; and SDG 6: water and sanitation (UNDP, 2015) as well as the World Association for Sexual Health’s Declaration of Sexual Rights (WAS, 1999). Figure 1 outlines how MHHM is a cross-cutting public health and human rights challenge that requires attention and action if SDGs 3–6 are to be attained (UNDP, 2015; Cross et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Health and Human Rights framework adapted from Neumeyer (82).

Background of current literature

Historically, taboos have kept MHHM from receiving much attention or discussion. While some anthropological literature documents societies that have celebrated menarche, menstrual blood itself has consistently been perceived as unclean, with girls and women instructed to discretely manage their menstruation and hide their menstruation-related challenges from public discourse (Sommer et al., 2015). MHHM first began to be mentioned by family planning advocates, primarily in reference to the married woman of reproductive age. However, the prioritization of the global health sector on reducing maternal morbidity and mortality in relation to the HIV/AIDS epidemic kept the discussions from focusing on the psychological and emotional challenges or the experiences of adolescent girls (Sommer et al., 2015). Similarly, the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and education sectors did not acknowledge MHHM until the 2000s, and then primarily framed it as a way to close the gender gap in schools (Sommer et al., 2015). Some believe that MHHM has been overlooked by these sectors because both stakeholders and donors believed it to be a private matter that should not have a public focus (Sommer et al., 2015). Therefore, each sector tackled MHHM in different ways at different times with different focuses, creating the segmented trend still seen today.

Despite the synchronous appearance of MHHM within different sectors, the connections between MHHM and the individual development domains of WASH, health, education, nutrition, and child protection are now documented in current literature. With regards to education, the relationship with MHHM is centered around schools providing adequate health education programs. MHHM also arises as an education issue when menstruation impacts girls’ school attendance, thus impacting the completeness and quality of their education (Haque et al., 2014; Hennegan & Montgomery, 2016).

WASH plays a significant role in MHHM as suitable WASH facilities are necessary for the attainment of adequate MHHM. A lack of appropriate WASH facilities at school can impact school attendance, and inadequate WASH facilities at home can reduce the overall quality of life (Bodat et al., 2013; Mathew et al., 2009). According to UNICEF (UNICEF, 2019), over 335 million girls still go to schools without clean water and soap, making it crucial to have private and adequate WASH facilities to practice proper MHHM.

The relationship between MHHM and health is mostly measured by access to healthcare or seeking healthcare, and the health effects of menstruation, such as irregular cycles, dysmenorrhea, and infections. Several studies show that being able to access healthcare and MHHM resources, such as disposable absorbents, positively correlate with fewer symptoms of menstruation; therefore, adolescent girls not having adequate access to such resources impact their daily lives, tying into the notion of health as a human rights issue (Lakshmi Narayanamma et al., 2016; Shingade 2016; Sumpter & Torondel, 2013). Sexual health and well-being are human rights issues as well (Kismödi et al., 2017), and MHHM is inextricably tied to sexual health. In one study, Cherenack et al. (2020) highlight that improved menstrual, sexual, and intravaginal practices are necessary because of high levels of menstrual, intravaginal, and sexual risk practices, particularly among adolescent girls and young women (AGYW).

Menstruation has also been related to dietary restrictions, which impact the nutrition of girls. Scientific studies show that the number of adolescent girls facing restrictions on eating specific foods ranges from 4.6 to 70% worldwide (Chothe et al., 2014; Farage et al., 2011; Goel & Kundan, 2011; Guterman et al., 2008; House et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2015; Kumar & Singh, 2014; Kumar & Srivastava, 2011; Paria et al., 2014; Ramaiya et al., 2016; Savanthe & Nanjundappa, 2016; Shanbhag et al., 2012; Tiwari et al., 2006). As women and girls are already discriminated against in comparison to men and boys in terms of food provision, there is a compounding effect that makes them more vulnerable to under-nutrition. Under-nutrition reduces the capabilities of adolescent girls and has long-term implications for the physiologic function of the body and the ability to thrive later in life (House et al., 2012; Sen, 1999).

Finally, the relationship between MHHM and child protection has been depicted mostly through addressing child marriage. Studies have shown a significant association between age at menarche and child marriage (Field & Ambrus, 2008; Ibitoye et al., 2017; Raj et al., 2015). When an adolescent girl attains menarche, she is thought to be a woman, signaling maturity and her ability to bear a child (Garg et al., 2001, 2012). Family honor and social traditions dictate that an adolescent girl who has attained menarche is of marriageable age (Garg et al., 2001; Ibitoye et al., 2017; Mahon & Fernandes, 2010; UNICEF, 2015). Child marriage is a harmful practice because it is associated with significantly higher rates of mental and physical health conditions, such as maternal mortality and morbidity, infant mortality and morbidity, intimate partner violence, depression, and anxiety.

While there is ample literature documenting the relationships between MHHM and the individual development domains of WASH, health, education, nutrition, and child protection, the literature is fragmented, stems from different academic disciplines, and frames MHHM as an issue within each of the five domains. This systematic review argues that MHHM has been hitherto neglected in the overall development sphere and aims to evaluate the extent to which adequate MHHM among adolescent girls is a fundamental human right. Jyoti Sanghera stated that “Stigma around menstruation and menstrual hygiene is a violation of several human rights, most importantly of the right to human dignity” (United Nations Human Rights, n.d.). In addition to this violation of human dignity, the stigma around MHHM perpetuates violations of rights to education, health, consensual marriage, and WASH (Menstrual Hygiene Day, 2014). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a landmark document for human rights, which holds all participating nations accountable to its tenets (United Nations General Assembly, 1948). According to the UDHR, people are the “rights holders” to security, dignity, and well-being and states are the “duty-bearers” to respect, protect, and fulfill those rights (United Nations Human Rights, n.d.). Table 1 outlines the covenants, comments, and articles that are most relevant to MHHM and how the states are violating their rights as duty-bearers.

Table 1.

Human Rights Articles and How the Rights Are Respected, Protected, and Fulfilled?

| Convention/Document/Treaty/Rapporteur | Article description | How are the rights violated by the state? (Respected, protected, fulfilled?) |

|---|---|---|

| Right to human dignity and non-discrimination | ||

| Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations General Assembly, 1948) | (1): “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” | States do not protect adolescent girls’ right to dignity |

| (2): “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as sex” | States do not fulfil adolescent girls’ right to freedom and non-discrimination. | |

| Right to education | ||

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (The United Nations, 1990) | (28e): “States Parties recognize the right of the child to education, and with a view to achieving this right progressively and on the basis of equal opportunity: Take measures to encourage regular attendance at schools and the reduction of drop-out rates.” | States do not fulfil to take measures to encourage regular attendance at schools. Which impacts health and future capabilities. |

| Right to consensual marriage | ||

| Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (UN General Assembly, 1981) | (16.1): “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in all matters relating to marriage” | States do not protect girls from early and forced marriage which impacts education and health |

| Highest attainable standard of health and comprehensive health education | ||

| International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UN General Assembly, 1966) |

(12.1): “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.” | States do not fulfil the right to physical and mental health. |

| International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights—General Comment 14 (UN Economic and Social Council (CESCR), 2000) | (34): “should refrain from limiting access to…health-related information, including sexual education and information, as well as from preventing people's participation in health-related matters.” (44d): “provide education and access to information concerning the main health problems in the community, including methods of preventing and controlling them”. | States do not fulfil the right to comprehensive health education. |

| Right to water and sanitation | ||

| International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights General Comment 15 (UN Economic and Social Council (CESCR), 2003) | (2): “The human right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic uses.” | States do not fulfil the right to adequate facilities and clean water. |

Identifying MHHM as a health and human rights issue requires states to respect, protect, and fulfill the right of its citizens to adequate MHHM (United Nations Human Rights, n.d.). Placing the UDHR as its foundation and using the human rights framework, this manuscript aims to assess existing literature to evaluate the practice of treating MHHM as a cross-cutting human rights issue through a narrative systematic review.

Finally, while adequate MHHM is crucial for anyone who menstruates, this review focuses primarily on adolescent girls. This is because adolescent girls are uniquely affected by MHHM challenges due to the physical, psychological, and emotional changes they experience during puberty. Additionally, adolescent girls are more vulnerable to violations of their MHHM-related rights, because of their dependence on parents and guardians. With lower levels of autonomy, adolescent girls’ access to adequate MHHM is not based solely on their decisions; it is also largely impacted by the knowledge, attitudes, norms, and decisions of their families.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

To be included in the review, articles had to: be in the English language (this was the only language all coders understood); mention adolescents, health or hygiene, and menstruation or menstrual; be primary studies in peer-reviewed or gray literature; and be published after the year 2000 (considered adequate to gain a full sense of the extant literature). The exclusion criteria were: not in the English language; did not have the key terms adolescents, health or hygiene, or menstruation or menstrual; systematic review, meta-analysis, commentaries, dissertations or editorials or not peer-reviewed or gray literature; or published before 2000.

Information sources

A total of four coders independently screened PubMed, Academic OneFile, and Google Scholar to obtain articles. These three databases were selected to allow us to cover a wide range of humanities and social science literature. Each coder focused on the relationship of MHHM with either health outcomes, education, child protection, nutrition, or WASH. If the article was not available locally or through the interlibrary loan, the corresponding author was contacted through email by the coder. Furthermore, the bibliographies of all included articles were screened to identify additional relevant articles pertaining to the research question.

Search

Iterations of seven key terms were used in the search: (1) menstrual health; (2) adolescents; (3) health outcomes; (4) education; (5) nutrition; (6) WASH; and (7) child protection. Table 2 includes the key terms and the iterations used across all three databases, taking into account the eligibility criteria identified above.

Table 2.

Seven Key Term Combinations Used to Conduct Searches in PubMed, Academic OneFile, and Google Scholar.

| Menstrual health | AND | Adolescents | AND | Cross-cutting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

OR

OR

OR

OR

|

OR

OR

|

Health outcomes:

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

Education:

OR

OR

OR

OR

Nutrition:

OR

OR

OR

OR

WASH:

OR

OR

OR

OR Child Protection:

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

OR

|

Study selection

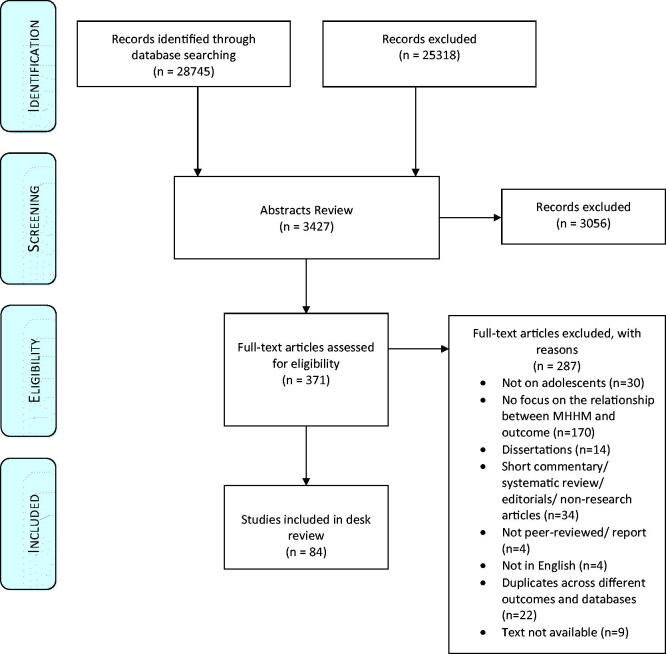

The PRISMA flow diagram was used to screen for articles that answered the research question and met the eligibility criteria. The screening was done at the title, abstract, and full-text review stages. When full-text articles were excluded, a reason was reported. Due to the high volume of results in Google Scholar (n = 26,004), not every result was examined from that search engine. Search results were screened until twenty consecutive results were unrelated to the topic, at which point the researcher moved on to the next set of search terms. Figure 2 outlines the PRISMA diagram of the systematic review process.

Figure 2.

Systematic outline of the review process.

Data collection process

Each coder assessed the quality of the selected full-text articles. Sirriyeh, Lawton, and Garner’s (Sirriyeh et al., 2012) coding matrix and quality assessment were adapted for this study, as it allowed assessment of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies and demonstrated good face validity and reliability. Table 3 outlines the criteria used for coding and assessment.

Table 3.

Criterion to Assess Quality of Manuscripts.

| Item |

Coding category |

Description |

| 1. | Citation | Full citation APA style |

| 2. | Type of manuscript | Peer Review Journal Article, Editorials/Commentary, Report, Newspaper Article |

| 3. | Type of sub-publication | Original article, narrative systematic review, meta-analysis |

| 4. | Precise location | School, village, district, province, state, country |

| 5. | Location | Enter country where study was conducted |

| 6. | Location: Region | Enter the region of the world |

| 7. | Intervention | Did the manuscript mention/describe an intervention? If yes, describe the intervention. Make sure to state who the intervention was for, the intervention activities, the dose, the site where activities took place, and duration of the intervention. |

| 8. | Audience: Primary | What was the primary audience of the intervention? |

| 9. | Audience: Secondary | What was the secondary audience of the intervention? |

| 10. | Level of influence: intrapersonal | Was the intervention addressing the intrapersonal domain of the socio-ecological model? |

| 11. | Level of influence: interpersonal | Was the intervention addressing the interpersonal domain of the socio-ecological model? |

| 12. | Level of influence: social | Was the intervention addressing the social domain of the socio-ecological model? |

| 13. | Level of influence: policy | Was the intervention addressing the policy domain of the socio-ecological model? |

| 14. | MHHM Definition | Was a definition for menstrual health and hygiene management stated? If yes, enter the definition. |

| 15. | Evaluation | If an intervention was described, was an evaluation conducted? |

| 16. | MHHM Variable | Is the MHHM variable the independent, dependent or confounding/mediator/moderator variable? |

| 17. | Other study variables | What are the other study variables? Are these the independent, dependent or confounding variables? |

| 18. | Type of study | Cross-sectional, Randomized control trial, quasi-experimental, case-control, longitudinal |

| 19. | Methods | What type of methods were described in the manuscript? Qualitative, Quantitative, Mixed-Methods, Participatory |

| 20. | Key Results | Discussion of key results (if quantitative study, state the significant findings) |

| 21. | Conceptual/Theoretical Frameworks | Theory of change is outlined and applied to examine the key components |

| 22. | Statement of aims/objectives (Research question) | Description on why the manuscript was written and its contribution to literature is provided. |

| 23. | Justification for analytical method selected | Detailed explanation on why an analytical method was selected. |

| 24. | Sample Description | Who are the participants of the study? Include the sample size as: (n=) |

| 25. | Sample size consideration in the analysis | How was the sample size calculated? For quantitative studies, power analysis is provided; for qualitative studies enough individuals to reach saturation. |

| 26. | Statistical assessment of reliability | Are measures used reliable? (e.g., was pretesting conducted? Was a literature review conducted on the measures used? Was reliability analyzed?). Enter text to explain. |

The assessment criteria were a 9-item scale (items 21–29). A number was assigned for each criterion. If the outlined criterion was not mentioned, 0 was given. If there was limited mention of the criterion, 1 was given. Some discussion of the criterion received a 2 and if there was a thorough discussion of everything outlined in the criterion, 3 was given. A maximum of 27 points could be given to each study. If a study received 19–27 points, it was coded as a “strong,” if a study received 10–18 points, it was coded as “moderate,” and if a study received 0–9 points, it was coded as “weak.”

To ensure the reliability of the quality assessment scores, double coding was conducted on a sub-sample of the articles. A fifth coder independently coded 20% of the database to ensure inter-rater reliability. Approximately 70% of the scores were within 4 points of the original score. Differences in coding were discussed and challenges were resolved.

Results

Overall, a total of 28,745 articles were screened across the three databases, with 3,427 included as part of the abstract review (11.9%), 371 for full-text eligibility (1.3%), and 83 in the desk review (0.3%). This section first describes the basic characteristics of the 83 included articles, followed by the results of their quality assessment. The final results are presented to detail the key findings of the articles and their connection of MHHM with the five development domains.

Table 4 provides background information on the 83 articles. where over 80% reported cross-sectional data and more than half (55.4%) used quantitative methodologies. The studies were derived from multiple geographical locations, with all (100%) set in developing, low-, and middle-income countries. India was the most frequent site, as the location of 29 articles (35.0%). The methodology used was predominantly quantitative (55.4%) and cross-sectional (83.1%). Only 22 (26.5%) of the articles described specific interventions. All (100%) studies involved adolescent girls, with school staff and administrators being the second most targeted audience (19.3%)

Table 4.

Summary of Articles Included in the Systematic Review (N = 83).

| Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Methodology | ||

| Quantitative | 46 | 55.4 |

| Qualitative | 17 | 20.5 |

| Mixed-methods | 12 | 14.5 |

| Participatory | 9 | 10.8 |

| Cross-sectional | 69 | 83.1 |

| Geographic regions | ||

| South Asia | 35 | 42.2 |

| Eastern Africa | 35 | 42.2 |

| Southern Africa | 24 | 28.9 |

| West and Central Africa | 9 | 10.8 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 9 | 10.8 |

| East Asia and the Pacific | 4 | 4.8 |

| Americas and the Caribbean | 1 | 1.2 |

| Combination | 1 | 1.2 |

| Targeted audience | ||

| Girls | 83 | 100 |

| School staff and administrators | 16 | 19.3 |

| Community members | 10 | 12.0 |

| Boys | 6 | 7.2 |

| Parents of girls | 6 | 7.2 |

| Non-governmental organizations and ministries | 3 | 3.6 |

Based on the quality assessment for the 83 articles, nine articles were coded as “strong” (10.8%), 46 (55.4%) were coded as “moderate,” and 28 (33.7%) were coded as “weak.” The two assessment criteria with the highest percentages of 0’s were “outlining a conceptual framework” (74.0%) and “justification for analytical method” (60.2%). The two criteria with the highest number of 3’s were “outlining a research question” (64.6%) and “recommendations” (43.8%).

Quality was also considered based on the inclusion of a definition of MHHM. More than 60% of the articles looked at the relationship of MHHM with health (37.3%) or with WASH (25.3%). The rest looked at the relationship of MHHM with education (13.3%) nutrition (7.2%), and child protection (2.4%). Additionally, 14.4% of the studies examined the relationship between MHHM and two development issues, for example, 7.2% of the articles examined the links between adequate MHHM with WASH and education.

Further, most of the studies were not based on or did not mention, a theoretical framework. Only 19 articles (22.9%) referenced using theories to guide their study. The most commonly used theory was the socioecological model, which represents a social system with every level of the system impacting the individual. Other mentioned theories include the grounded theory, social cognitive theory, the PRECEDE model, the MRC framework, and feminist theory.

Across the domains, sociodemographic factors were highlighted, especially poverty, social restrictions, secrecy around menstruation within the societies in which the studies took place, lower socio-economic status, and mothers with lower literacy. These factors were also associated with a lack of facilities, which emerged as a major factor in achieving adequate MHHM (Rizvi & Ali, 2016; Kusuma & Ahmed, 2016).

Thirty articles (36.1%) related MHHM and access to adequate facilities, outlining ramifications for child protection, WASH, education, and health. Lack of facilities was also examined in the context of knowledge, restrictions, seeking healthcare, facilities available in school, access to information and support, and not disposing of the menstrual absorbent in the toilet or latrine. Limited access to facilities was associated with dirty and constricted water and sanitation facilities within the school and home environment. The cycle of inadequate procurement of clean menstrual absorbents, infrequent changing of absorbents, inadequate drying of absorbents in the sun, and unsafe disposal further led to physical discomfort, inconvenience, embarrassment, and school absenteeism. Seven studies demonstrated that access to facilities (including covered toilets, locked doors, and availability of clean absorbents, water, soap, and dustbins) coupled with education programs was protective for MHHM and school attendance during menstruation (Auemaneekul et al., 2013; Gultie, 2014; Jones et al., 2015; Montgomery et al., 2012; Naeem et al., 2015; Shah et al., 2013; Varghese et al., 2015).

Fourteen articles outlined the relationship between MHHM with health and nutrition, One article demonstrated that those with better individual health had better menstrual health (p = .001) (Fakhri et al., 2012). Most of the studies associated poor MHHM with social secrecy and taboos surrounding menstruation, which led adolescent girls to use unhygienic methods (cloth), stay home from school, not exercise, and be unable to perform daily tasks during menstruation. These factors, described in several studies, led to adolescent girls being significantly more likely to exhibit at least one symptom of a reproductive tract infection (OR = 1.046–1.94, p < .05), vaginal discharge (OR = 1.303, p < .001), urinary tract infection (OR: 1.38, p < .05), and sexually transmitted infections, as well as a lower likelihood of seeking treatment for any of these health problems (Anand et al., 2015; Balamurugan et al., 2014; Bathija et al., 2013; Khanna et al., 2005; Sumana et al., 2015; Walraven et al., 2002). One article provided contradictory information by showing no association between either washing the cloth with soap and water or not, or drying the cloth in the sun or not and having reproductive tract infection or sexually transmitted infection symptoms (Dongre et al., 2007). Two articles outlined a negative relationship between adequate MHHM and nutrition. Religion and mothers’ education showed either societal-imposed or self-imposed restrictions, such as avoiding food during menstruation to manage the menstrual flow (Rizvi & Ali, 2016, Santina et al., 2013).

There were 15 articles (18.1%) outlining the importance of pre-menarche training and health education that cut across health, education, and WASH issues (Aniebue et al., 2010; Arora et al., 2013; Chiou et al., 2007; Chiou & Wang, 2008; Djalalinia et al., 2012; Dongre et al., 2007; El-Lassy & Madian, 2013; Fakhri et al., 2012; Fetohy, 2007; Haque et al., 2014; Montgomery et al., 2012; Nemade et al., 2009; Pokhrel et al., 2014; Vijaysree et al., 2016). These programs covered all definitional aspects of MHHM, all of which were operationalized except for the ability to change the absorbent in privacy. Additional MHHM information in these programs included regularity of menstrual cycle, knowledge, health-seeking behavior, student’s behavior during the first day of menstruation, tendency to stay at home, school absenteeism during menstruation, change in diet during menstruation (restrictions), and methods for managing menstrual problems.

Overall, there was a lack of consistency in the results when it came to pre-menarche training and education. Those who had prior knowledge on menstruation had better handwashing (Vijaysree et al., 2016), had a higher proportion reporting no pain during menses (29.3 vs. 20.7%, p = .05), had a higher proportion having no effect on schooling life (33.3 vs. 19.8%, p < .01), had a higher proportion using sanitary pads (75.1 vs. 61.7%, p < .01), and had a higher proportion disposing of absorbents by burning (35.5 vs. 25.2%, p < .01) (61). At the same time, pre-menarche training and frequency of changing absorbent were not significantly associated (Aniebue et al., 2010). In one study, those who did not have prior knowledge of menstruation had better disposal practices Vijaysree, 2016).

Results from studies summarizing health education programs in schools showed that after adjusting for other co-factors, those who had never received health education had a 44% greater probability (p = .04) of dysmenorrhea than those who had previously received health education (Chiou & Wang, 2008). Health educational programs had a positive correlation with improved intention to visit the health center at any time, increased knowledge, better attitudes, hygienic choice of absorbent, increased frequency of changing sanitary pads, reusing of cloth after washing, proper cleanliness of genitalia during menstruation, improved self-care behavior, increased bathing during menstruation, increased school attendance, fewer health complications, and seeking treatment for a reproductive tract infection or sexually transmitted infection as compared to the control group (Anand et al., 2015; Arora et al., 2013; Chiou et al., 2007; Chiou & Wang, 2008; El-Lassy & Madian, 2013; Fakhri et al., 2012; Fetohy, 2007; Haque et al., 2014; Montgomery et al., 2012; Nemade et al., 2009; Pokhrel et al., 2014). One study demonstrated that, while training by either parents or health trainers was beneficial in comparison to no training, school health trainers elicited better MHHM behaviors (Djalalinia et al., 2012).

Only two (2.4%) articles fell in the child protection domain, considering issues of child marriage and bullying. Both of these articles drew the connection between MHHM and WASH through education (Jones et al., 2015; Ngugi & Nyaura, 2014). One article described the harmful physical and emotional treatment of girls by boys in school, including mocking, stigmatizing, isolating, bullying, and name-calling (Ngugi & Nyaura, 2014). This negative treatment of girls by boys eventually led to some girls dropping out of school (Ngugi & Nyaura, 2014). The second child protection article outlined the pathway from MHHM challenges, such as physical discomfort and shame, to ultimately dropping out of school, which can then lead to increased instances of early marriage (Jones et al., 2015). Child marriage is a central child protection issue; thus, the article argued the importance of solving MHHM issues so that girls would be more likely to stay in school, protecting them from underage marriage (Jones et al., 2015). Two additional articles (2.4%) considered child protection as a function of WASH and education. One of these articles claimed that without proper sanitation and supportive adaptations in education, it would not be possible to achieve gender equality and female empowerment, nor protect girls from harassment and marginalization (Jewitt & Ryley, 2014). Both of these articles emphasized poverty and the failure to provide for the basic needs of children. Children living in poverty did not have access to resources, such as clean sanitary products, pain-relieving medication, and adequate ways of disposing of sanitary products and could not practice adequate MHHM safely and healthily. However, the studies emphasized that donations of sanitary products were not the solution. For example, in one of the studies, two schools that received donations of disposable pads only had short-term benefits; to make the benefits long-term, there needs to be a reliable alternative, such as reusable sanitary pads (Jewitt & Ryley, 2014).

Discussion

This systematic review sought to understand the extent to which adequate MHHM is related to WASH, health, education, nutrition, and child protection, connected through a human rights approach. Overall, the quality of the studies was too variable to make explicit conclusions on MHHM as a human rights issue, with 89% being of low (weak) or moderate quality when evaluated by the adapted quality assessment scale. Nonetheless, the results do demonstrate relationships between MHHM and the SDG goals and provided important insight into future research and programming to consider MHHM holistically in the context of health, education, WASH, child protection, and nutrition.

The review illustrated that most articles did not explicitly consider MHHM as a human rights issue but rather framed it as a single issue, or in some cases a combination of two issues. As only a handful of studies utilized a multi-disciplinary approach to address MHHM, there is a clear need to increase the integration of less represented sectors in future research and programs. Primarily, articles framed MHHM as either a health, wash, or education issue (37, 25, and 13%, respectively), while only fewer than 10% combined focused on nutrition and child protection (7 and 2%, respectively). The articles that focused on more than one topic area mostly combined WASH with education. For example, multiple studies found that menstruation has a negative impact on education because girls miss school due to schools lacking adequate and private WASH facilities; this, in turn, leads to gender discrimination in the school environment, such as bullying and teasing from male peers and male peers having more opportunities to spend time at school, leading to more exposure to education (Sommer et al., 2016). The other common combination of domains was health and education, with studies that showed a lack of proper health education due to secrecy and taboos surrounding menstruation leading to girls using unhygienic methods during menstruation and thus, have increased risks of vaginal discharge, urinary tract infections, and sexually transmitted infections. These findings suggest that WASH and/or health could be effective focal points of cross-cutting interventions, while the education domain can be an effective nexus, linking the domains. Education could also help situate MHHM within the context of sexual rights and sexual health, which are considered human rights issues. Additionally, tying sexual pleasure to sexual health and recognizing that it is an important aspect of sexuality (and thus sexual health) can reduce adverse outcomes, such as sexually transmitted infections, unintended pregnancy, and sexual violence (Ford et al., 2019). As no intervention has yet taken a full human rights approach to address MHHM, expanding and bridging already existing approaches may be crucial to success.

Furthermore, the results of many of the studies outlined limitations that lead to poor MHHM, including the existence of negative cultural and traditional beliefs toward menstruation, teachers’ insufficient knowledge of MHHM to teach comprehensive reproductive health, girls’ inability to afford to buy disposable sanitary pads that would reduce rashes and infections, and the lack of access to appropriate healthcare and adequate WASH facilities in schools (Tamiru et al., 2015). This combination of issues, while not exhaustive, supports the idea that MHHM is a cross-cutting issue; solutions to one domain alone will not completely address the barriers to adequate MHHM. If solutions are required in all domains, a multi-sectoral approach is likely to be the most complete approach, more likely to achieve comprehensive results.

The systematic review also found that all studies were set in developing, low- and middle-income countries. This is unsurprising, given that low- and middle-income countries are generally the focus of work in the development domains, more likely to have limited access to water and sanitation services, limited access to healthcare, and barriers to accessing education (UNICEF/WHO, 2016). However, it emphasizes the need for programs that consider achieving MHHM as a product of improvement in multiple development domains; challenges exist across development sectors in low- and middle-income countries, all of which can impact the ability of girls and women to achieve adequate MHHM.

It is important to note that the emphasis on taking a comprehensive, cross-cutting approach does not mean a sector-specific approach is without advantages. Having a sectoral approach allows each sector to utilize its expertise at maximum capacity and have a straightforward influence on relevant policies. For example, the education sector can focus on creating a comprehensive curriculum to be implemented at every school in one town or the health sector can focus on providing adolescent-friendly reproductive care at all hospitals of one region. These targeted initiatives will surely expand access to adequate MHHM for adolescent girls. However, as seen in many studies in this review, MHHM cuts across multiple sectors, such as adequate reproductive education being crucial to encourage proper nutrition and health habits, and the need for adequate sanitation facilities in schools so that girls can continue going to school, leading to decreased school dropout rates, preventing child marriage. As MHHM does not only apply to one sector, the collaboration of multiple sectors leads to a comprehensive program with a broader reach, more likely to result in the attainment of adequate MHHM for all girls and women.

In addition to taking a comprehensive approach, efforts must be made to improve the quality of programs and interventions; only nine of the 83 articles were rated as strong. One particularly weak area across the studies was the use of theoretical frameworks. Using theories and conceptual models is imperative for evidence-based research because they provide a roadmap of how to achieve the desired behavior change. Yet despite the importance of theoretical frameworks, only 19 articles (23%) included in this study mentioned using a conceptual model or theory. The low percentage of studies employing a theory or model as a basis for the research demonstrates the need to emphasize this approach. As programs shift to multi-sectoral approaches, frameworks are even more important as they will map how all of the determinants work together and how larger, systemic factors can affect the pathway to change. They can draw the relationship between factors that hinder change, such as taboos that lead to social restrictions, as well as help to identify the key players that can facilitate changes. Having a theoretical framework and/or conceptual model can also serve as a guide to design and evaluate interventions and programs, as they help identify the components that need to be measured to observe short-, medium- and long-term outcomes (UNICEF, 2019). Rigorous monitoring and evaluation will be vital to identifying which cross-cutting, human-rights-based strategies actually improve the ability to achieve adequate MHHM.

Regardless of the theory chosen, future studies should be created using a framework that incorporates a multi-level approach to attain the maximum level of impact. One example of this is the Socioecological Model, which encourages intervention at multiple levels of society and takes into account, not just personal perceptions, but also societal and cultural norms and environmental and social influences (Naeem et al., 2015). The results of the review demonstrated that current approaches are siloed and often focus on the same few entry points: school-based interventions for adolescent girls that use teachers as the primary influencers. Still, some studies did target women, parents, schoolteachers, male students, and school administrators in addition to targeting adolescent girls. Targeting not just girls but other influential members of the society allowed studies to use a participatory approach to gain a better understanding of different perspectives of girls’ challenges and experiences, as well as the gaps in knowledge and resources regarding MHHM in the target communities. One study by Long (Long et al., 2013) conducted focus group discussions with mothers, teachers, and male students; the mothers expressed discomfort and fear in regard to talking about menstruation with their daughters because they lacked formal MHHM education, teachers admitted difficulty in teaching menstruation and reproductive health because of cultural norms and disapproval from parents, and students described their teachers, particularly male teachers, as scared to teach about menstruation and only giving the class an overview of the topic. From these results, the study recommends schools to have policies, facilities, and resources to allow girls to discreetly and affordably manage menstruation, providing comprehensive menstruation education to be provided to pre-menarche primary school girls, strengthening teachers’ capacities so they can provide in-depth and accurate information in schools, and local and national governments to enact policies that encourage adequate WASH facilities in schools (Long et al., 2013). These findings reiterate that to tackle MHHM issues from a comprehensive approach, it is essential to broaden the scope of the target population and engage a wide range of stakeholders.

Finally, and crucially, the systematic review results underscore the need to standardize the concept and definition of MHHM. The inclusive definition of menstrual hygiene management that incorporates ideas of procurement, storage, personal hygiene, privacy, frequency of changing, and disposal, has been beneficial in guiding broader interventions in the past decade; still, the results showed that none of the studies are yet using this inclusive definition of menstrual hygiene management in full. Of the 83 studies, only seven outlined any definition of MHHM and none of those seven included procurement, storage, personal hygiene, privacy, frequency of change, or disposal in their definition. While efforts should be made to incorporate all aspects of menstrual hygiene management, it is clear that components of menstrual health and hygiene, the broader systemic factors affecting the ability to achieve adequate menstrual hygiene, must also be integrated. Continuing to base studies and interventions on a definition related to facilities and supplies alone will lead not lead to the full achievement of MHHM-related human rights. A comprehensive definition of MHHM that encompasses all elements is needed to guide any cross-cutting human rights approaches to addressing menstruation-related issues.

Limitations

Limitations exist in every study. This study included a time limit to conduct the searches, which may have led researchers to miss some articles that could have qualified for the study. There were multiple coders, which may have resulted in discrepancies in coding. However, in an attempt to eliminate these discrepancies, a thorough screening of the articles that qualified for the study was conducted by one of the coauthors and 20% of those articles were reassessed by an external reviewer to evaluate inter-rater reliability. This also ended up being a narrative systematic review rather than a meta-analysis because the study team believed it was necessary to include qualitative and mixed-methods studies. Only English publications that were available online were included in the search, reducing the generalizability to non-English publications.

Publication bias could also be a concern, but this was minimized since gray literature (reports) were allowed as part of the inclusion criteria. In terms of the location of the studies, although there were no exclusion criteria for the geographical setting of the studies, all studies were from low and middle-income countries. This limited the extent of analysis for studies in developed countries.

Another significant limitation is that the studies included in this review focus on MHHM of adolescent girls. Including studies on all women of reproductive age may have provided different results, as the challenges experienced by older women are likely to differ from those of adolescent girls. While a further review that incorporates studies of all menstruating women will be useful to create a holistic picture of the field of MHHM, the authors do believe that beginning the discussion around adolescent girls’ MHHM and human rights is an important starting point. Improving interventions and programs targeting adolescent girls also provides the opportunity to generate a longer-lasting impact, as adolescent girls will experience menstruation for a long time after the interventions have been conducted.

The studies have also been analyzed using the original definition of menstrual hygiene management, provided in the beginning. Conducting the quality assessment of articles with a more comprehensive definition that incorporates systemic factors would provide different results and allowed for the identification of studies taking comprehensive approaches. Finally, another consideration regarding the quality assessment of articles is that the databases used did not contain information about ethical considerations. Ethical considerations are paramount to research, particularly research that focuses on MHHM and adolescents. Thus, not being able to use this to assess the quality of the articles was a limitation.

Recommendations

Treating MHHM as a human rights issue encourages programs to take a comprehensive approach, with multiple sectors working in collaboration. To elevate MHHM programming, based on the results of the review, it is recommended that a comprehensive definition of MHHM is developed and adopted, that MHHM is considered a human rights issue, and that all future MHHM programming takes a multisectoral approach and base their interventions on a holistic theoretical framework.

Given the inconsistent description of adequate MHHM across studies, it is time for all development domains to employ a more holistic definition of MHHM to accompany the comprehensive human-rights-based approach. While the current definition of menstrual hygiene management provided in the background may have served as an adequate starting point, it is likely to be limiting for future work. As mentioned in the discussion, that definition does not encompass the social norms, stigma, and other systemic factors that have led to the need for a multi-sectoral, human rights approach. Thus, an expanded definition is proposed. The definition should not only include the use of clean sanitary products that can be changed in privacy as often as necessary for the duration of menstruation, access to adequate sanitation facilities that includes soap and clean water, and access to proper disposal of used sanitary products but also include living free of social norms and taboos that influence systemic barriers that hinder anyone who menstruates from accessing the aforementioned adequate resources.

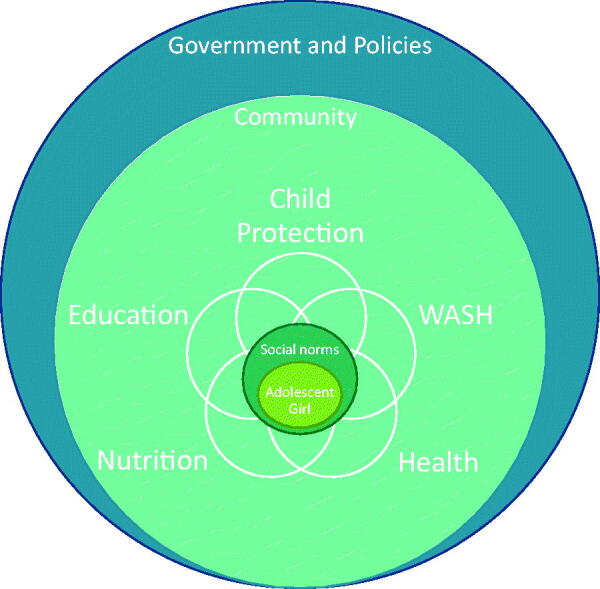

In line with this definition, Figure 3 depicts how adolescent girls are influenced by social norms surrounding them, and to shift those norms, different sectors, such as education, child protection, WASH, health, and nutrition can work together to influence the girls’ community, and more broadly, the government sectors, to change policies. Including social norms is imperative, as social norms exacerbate the systemic factors keeping girls from accessing adequate healthcare, sanitation facilities, and menstrual supplies, thus preventing them from practicing adequate MHHM and leading to violations of girls’ human rights.

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework of MHHM with a human rights approach.

MHHM as a construct has not been measured consistently within scientific studies. There has only been one study that conducted psychometric testing of an MHHM scale, and even then, only in the pre-testing phase Ray & Aparajita, 2012). Reliable and valid measures, based on a comprehensive definition, are essential to understanding the burden of inadequate MHHM within communities. Additionally, creating a tested construct of MHHM will support the use of it in theoretical models, which is a further recommendation for improving programs and research.

Predominantly, MHHM has been studied in silos, focusing on its relationship with individual issues in WASH, health, hygiene and nutrition, education, and child protection, even though MHHM cuts across several SDG goals. As issues of MHHM are a complex blend that requires multiple solutions, having a multi-sectoral, comprehensive approach where each sector comes up with what they can contribute, while working together with other sectors, is necessary. Moreover, countries and states will be challenged to meet MHHM goals if the social norms and taboos around menstruation remain unchanged. A comprehensive approach that takes a human rights lens should engage not only adolescent girls, but their parents, teachers, and other stakeholders in the community to shift social norms and taboos. Such an approach would address adolescent girls’ immediate needs, such as access to clean sanitary products and sanitation facilities, as well as building the knowledge and skills needed to properly understand menstruation and how to manage it, creating an environment where adolescent girls feel empowered instead of being bullied or shamed, and changing policies at the local, regional, and national level to institutionalize protections for MHHM-related rights (UNICEF, 2019; Plan International USA, 2018).

Note, while there is a need to focus on MHHM as a cross-cutting topic, taking a multisectoral approach doesn’t mean the dissolution of MHHM promotion activities within individual development domains; every sector can individually strengthen their approaches to improve MHHM while acknowledging the need to work in collaboration with others. For example, a cross-cutting program implemented on a community-level could have WASH experts promote access to adequate hygiene in schools and build adequate sanitation facilities, education specialists to develop a curriculum that not only addresses reproductive education but ways to respond to stigma and bullying surrounding menstruation, healthcare workers to provide exams and HPV vaccinations at community clinics, and child protection specialists holding forums with parents on the connections between poor MHHM and child marriage. As issues of MHHM are a complex blend that requires multiple solutions, having a multi-sectoral, comprehensive approach where each sector comes up with what they can contribute while working together with other sectors is. The one caveat is that those involved in human rights overall need to connect with the other sectors to make sure that MHHM isn’t being forgotten. Clear coordination and collaboration may come best from a human rights locus.

An example of a multi-sectoral program has been implemented by Plan International in 28 countries. Plan’s program includes targeted MHHM education through community platforms, such as teacher training and promoting peer educators, initiating discussions in schools to allow students, parents, and community elders to come together to break the silence surrounding stigma and social taboos of menstruation, and creating adequate sanitation facilities with changing rooms and incinerators for proper disposal of used sanitary products (Plan International USA, 2018). Although this program only extends to the community level, future programs can go beyond by working with government sectors to evaluate successful programs, scale them up, and conduct them in other regions of the country.

Finally, it is recommended that, since MHHM is a human rights issue, those most impacted should be involved and their opinions and voices amplified. Participatory methods, allowing target populations to be involved in the design, implementation, and evaluation of programs, would be an effective way to break the silence and increase communication about MHHM among community members. At the same time, states can protect and respect the rights of adolescent girls by engaging and contracting with local grassroots non-governmental organizations to educate adolescent girls, boys, mothers, fathers, and community members to decrease stigma and to increase dialogue about menstruation (Hennegan & Montgomery, 2016; Neumeyer, n.d.). Participatory methods would be effective tools to empower community members as implementers and change cultural norms to make sustainable changes around MHHM. Adolescent girls, in particular, should be engaged in implementing programs—they should not just have interventions performed on and for them but be empowered to support the realization of their rights.

Conclusion

Although menstruation is a normal biological process, it is associated with impurity and is considered taboo in many countries worldwide. The silence around menstruation generated by the taboo makes women and adolescent girls vulnerable to many human rights and health violations. It is essential to examine MHHM as a cross-cutting, multi-disciplinary, human rights issue, that is key to achieving several SDGs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Carmen Cronin, Jessica Lopez, Tashi Lhamo, Manasvi Shah, and Mariana Chilton for their support and assistance in conducting the review.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Author contributions

SS1 was the principal investigator, oversaw the review process, and edited the manuscript. SS2 and MO reviewed the data and wrote and edited the manuscript. AR conducted the majority of the review and assisted with manuscript writing. MH reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Anand, E., Singh, J., & Unisa, S. (2015). Menstrual hygiene practices and its association with reproductive tract infections and abnormal vaginal discharge among women in India. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 6(4), 249–254. 10.1016/j.srhc.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aniebue, U., Aniebue, P., & Nwankwo, T. (2010). The impact of pre-menarcheal training on menstrual practices and hygiene of Nigerian school girls. Pan African Medical Journal, 2(1), 1-9. 10.4314/pamj.v2i1.51708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora, A., Mittal, A., Pathania, D., Singh, J., Mehta, C., & Bunger, R. (2013). Impact of health education on knowledge and practices about menstruation among adolescent school girls of rural part of district Ambala. Haryana. Indian Journal of Community Health, 25(4), 492–497. [Google Scholar]

- Auemaneekul, N., Bhandari, S., & Kerdmongkol, P. (2013). Menstrual hygiene practice among adolescent in a rural district of Nepal. Asia Journal of Public Health, 4, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan, S. S., Shilpa, S., & Shaji, S. (2014). A community based study on menstrual hygiene among reproductive age group women in a rural area, Tamil Nadu. Journal of Basic and Clinical Reproductive Sciences, 3(2), 83–87. 10.4103/2278-960X.140040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bathija, G. V., Bant, D. D., & Itagimath, S. R. (2013). Study on usage of woman hygiene kit among menstruating age group in field practice area of Kims. International Journal of Biomedical Research, 4(2), 94–98. 10.7439/ijbr.v4i2.233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodat, S., Ghate, M. M., & Majumdar, J. R. (2013). School absenteeism during menstruation among rural adolescent girls in Pune. National Journal of Community Medicine, 4(2), 212–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cherenack, E. M., Rubli, J., Dow, D. E., & Sikkema, K. J. (2020). Sexual risk behaviors and menstrual and intravaginal practices among adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania: A cross-sectional, school-based study. International Journal of Sexual Health, 32(4), 394–407. 10.1080/19317611.2020.1821861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, M. H., & Wang, H. H. (2008). Predictors of dysmenorrhea and self-care behavior among vocational nursing school female students. Journal of Nursing Research, 16(1), 17–25. 10.1097/01.JNR.0000387286.30688.5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, M. H., Wang, H. H., & Yang, Y. H. (2007). Effect of systematic menstrual health education on dysmenorrheic female adolescents' knowledge, attitudes, and self-care behavior. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 23(4), 183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothe, V., Khubchandani, J., Seabert, D., Asalkar, M., Rakshe, S., Firke, A., Midha, I., & Simmons, R. (2014). Students’ perceptions and doubts about menstruation in developing countries: A case study from India. Health Promotion Practice, 15(3), 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross, D., Shaw, T., Hadwen, K., Cardoso, P., Slee, P., Roberts, C., Thomas, L., & Barnes, A. (2016). Longitudinal impact of the cyber friendly schools program on adolescents’ cyberbullying behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 42(2), 166–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djalalinia, S., Tehrani, F. R., Afzali, H. M., Hejazi, F., & Peykari, N. (2012). Parents or school health trainers, which of them is appropriate for menstrual health education? International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3(9), 622. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongre, A. R., Deshmukh, P. R., & Garg, B. S. (2007). The effect of community-based health education intervention on management of menstrual hygiene among rural Indian adolescent girls. World Health & Population, 9(3), 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Lassy, R. B., & Madian, A. A. E. (2013). Impact of health educational program on menstrual beliefs and practices of adolescent Egyptian girls at secondary technical nursing school. Life Science Journal, 10(2), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhri, M., Hamzehgardeshi, Z., Golchin, N. A. H., & Komili, A. (2012). Promoting menstrual health among Persian adolescent girls from low socioeconomic backgrounds: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 1–5. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farage, M. A., Miller, K. W., & Davis, A. (2011). Cultural aspects of menstruation and menstrual hygiene in adolescents. Expert Review of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 6(2), 127–139. 10.1586/eog.11.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fetohy, E. M. (2007). Impact of a health education program for secondary school Saudi girls about menstruation at Riyadh city. Journal of Egypt Public Health Association, 82(1–2), 105–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field, E., & Ambrus, A. (2008). Early marriage, age of menarche, and female schooling attainment in Bangladesh. Journal of Political Economy, 116(5), 881–930. 10.1086/593333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J. V., Corona Vargas, E., Finotelli, I. Jr., Fortenberry, J. D., Kismödi, E., Philpott, A., Rubio-Aurioles, E., & Coleman, E. (2019). Why pleasure matters: Its global relevance for sexual health, sexual rights and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 217–230. 10.1080/19317611.2019.1654587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garg, R., Goyal, S., & Gupta, S. (2012). India moves towards menstrual hygiene: subsidized sanitary napkins for rural adolescent girls—Issues and challenges. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(4), 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg, S., Sharma, N., & Sahay, R. (2001). Socio-cultural aspects of menstruation in an urban slum in Delhi. Reproductive Health Matters, 9(17), 16–25. 10.1016/S0968-8080(01)90004-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, A. (2016). An opportunity to address menstrual health and gender equity. FSG. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, M. K., & Kundan, M. (2011). Psycho-social behaviour of urban Indian adolescent girls during menstruation. The Australasian Medical Journal, 4(1), 49–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gultie, T. K. (2014). Practice of menstrual hygiene and associated factors among female Mehalmeda high school students in Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Science Journal of Public Health, 2(3), 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Guterman, M., Mehta, P., & Gibbs, M. (2008). Menstrual taboos among major religions. The Internet Journal of World Health and Societal Politics, 5(2), 2. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, S. E., Rahman, M., Itsuko, K., Mutahara, M., & Sakisaka, K. (2014). The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: An intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. BMJ Open, 4(7), e004607. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennegan, J., & Montgomery, P. (2016). Do menstrual hygiene management interventions improve education and psychosocial outcomes for women and girls in low and middle income countries? A systematic review. PLoS One, 11(2), e0146985. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House, S., Mahon, T., & Cavill, S. (2012). Menstrual hygiene matters hygiene around the world (pp. 1–352). ACF; Care; IRC; OXFAM; Plan; Save the Children; UNICEF; USAID; WASH; WaterAid; World Vision. [Google Scholar]

- Ibitoye, M., Choi, C., Tai, H., Lee, G., & Sommer, M. (2017). Early menarche: A systematic review of its effect on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One, 12(6), e0178884. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, S., & Ryley, H. (2014). It’s a girl thing: Menstruation, school attendance, spatial mobility and wider gender inequalities in Kenya. Geoforum, 56, 137–147. 10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.07.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N., Tefera, B., Presler-Marshall, E., Gupta, T., Emirie, G., Gebre, B., & Berhanu, K. (2015). Now I can propose ideas that can solve any problem: The role of community awareness interventions in tackling child marriage in Ethiopia. https://odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/10306.pdf

- Khanna, A., Goyal, R. S., & Bhawsar, R. (2005). Menstrual practices and reproductive problems: A study of adolescent girls in Rajasthan. Journal of Health Management, 7(1), 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kismödi, E., Corona, E., Maticka-Tyndale, E., Rubio-Aurioles, E., & Coleman, E. (2017). Sexual rights as human rights: A guide for the WAS declaration of sexual rights. International Journal of Sexual Health, 29(sup1), 1–92. 10.1080/19317611.2017.1353865 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D., Goel, N. K., Puri, S., & Gupta, N. (2015). Dietary practices during menstruation among unmarried girls in Chandigarh. International Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Inventions, 2(4), 860–865. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., & Singh, A. K. (2014). Menstrual practices and hygiene among adolescent: A cross-sectional study in urban area of Garhwal, Uttarakhand. International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies, 2(2), 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A., & Srivastava, K. (2011). Cultural and social practices regarding menstruation among adolescent girls. Social Work in Public Health, 26(6), 594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma, M., & Ahmed, M. (2016). Awareness, perception and practices of government pre-university adolescent girls regarding menstruation in Mysore city, India. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 3(6), 1593. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi Narayanamma, V., Indira, I., Prasad G., & Jyothsna, J. (2016). Adolescent menstrual problems in a rural community in Andhra Pradesh. National Journal of Community Medicine, 132–138. 5(2). [Google Scholar]

- Long, J., Caruso, B. A., Lopez, D., Vancraeynest, K., Sahin, M., Andes, K. L., & Freeman, M. C. (2013). WASH in schools: Empowers girls' education in rural Cochabamba, Bolivia: An assessment of menstrual hygiene management in schools. United Nations Children's Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon, T., & Fernandes, M. (2010). Menstrual hygiene in South Asia: A neglected issue for WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) programmes. Gender & Development, 18(1), 99–113. 10.1080/13552071003600083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, K., Zachariah, S., Shordt, K., Snel, M., Cairncross, S., Biran, A., & Schmidt, W. P. (2009). The sustainability and impact of school sanitation, water and hygiene education in southern India. Waterlines, 28(4), 275–292. 10.3362/1756-3488.2009.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menstrual Hygiene Day (2014). Menstrual Hygiene is fundamental to realizing Human Rights 2014. http://menstrualhygieneday.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/HumanRights.pdf

- Montgomery, P., Ryus, C. R., Dolan, C. S., Dopson, S., & Scott, L. M. (2012). Sanitary pad interventions for girls' education in Ghana: A pilot study. PLoS One, 7(10), e48274. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, K., Klawitter, S., & Aziz, A. (2015). Learning, acting, and learning (LAL) research on schools' menstrual hygiene management (MHM): Pakistan. Waterlines, 34(1), 103–112. 10.3362/1756-3488.2015.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nemade, D., Anjenaya, S., & Gujar, R. (2009). Impact of health education on knowledge and practices about menstruation among adolescent school girls of Kalamboli, Navi-Mumbai. Health and Population-Perspectives and Issues, 32(4), 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Neumeyer, H. (n.d.). Menstrual hygiene & human rights: A bloody road to a more equal world. UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- Ngugi, M. N., & Nyaura, J. E. (2014). Demystifying the menstruation process among the Kenyan girl-child “a period of shame”: A sociocultural perspective. http://edocs.maseno.ac.ke

- Paria, B., Bhattacharyya, A., & Das, S. (2014). A comparative study on menstrual hygiene among urban and rural adolescent girls of West Bengal. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 3(4), 413. 10.4103/2249-4863.148131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plan International USA (2018). Menstrual hygiene management. [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel, S., Mahantashetti, N., Angolkar, M., & Devkota, N. (2014). Impact of health education on the knowledge and practice regarding personal hygiene among pre university female students of a college located in urban area of Belgaum. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science, 3(4), 38–44. 10.9790/1959-03413844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A., Ghule, M., Nair, S., Saggurti, N., Balaiah, D., & Silverman, J. G. (2015). Age at menarche, education, and child marriage among young wives in rural Maharashtra, India. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 131(1), 103–104. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaiya, A., Malhotra, A., & Sood, S. (2016, October 29–November 2). Individual and community level correlates for menstrual taboos: A population based cross-sectional study in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. American Public Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, S., & Aparajita, D. (2012). Determinants of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls: A multivariate analysis. National Journal of Community Medicine, 3(2), 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi, N., & Ali, T. S. (2016). Misconceptions and mismanagement of menstruation among adolescents girls who do not attend school in Pakistan. Journal of Asian Midwives, 3(1), 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Santina, T., Wehbe, N., Ziade, F. M., & Nehme, M. (2013). Assessment of beliefs and practices relating to menstrual hygiene of adolescent girls in Lebanon. International Journal of Health Science & Research, 3(12), 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Savanthe, A., & Nanjundappa, V. (2016). Menstruation: A cross-sectional study on knowledge, belief, and practices among adolescent girls of junior colleges, Kuppam, Andhra Pradesh. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health, 5(1), 22–27. 10.5455/ijmsph.2016.100620157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S. P., Nair, R., Shah, P. P., Modi, D. K., Desai, S. A., & Desai, L. (2013). Improving quality of life with new menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent tribal girls in rural Gujarat. Reproductive Health Matters, 21(41), 205–213. 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41691-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanbhag, D., Shilpa, R., D'Souza, N., Josephine, P., Singh, J., & Goud, B. R. (2012). Perceptions regarding menstruation and practices during menstrual cycles among high school going adolescent girls in resource limited settings around Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health, 4(7), 1353. [Google Scholar]

- Shingade, P. P., Suryavanshi, J., & Kazi, Y. (2016). Menstrual hygiene among married women: a hospital based cross-sectional study in an urban slum of Mumbai, India. International Journal of Community Medicine & Public Health, 3, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sirriyeh, R., Lawton, R., Gardner, P., & Armitage, G. (2012). Reviewing studies with diverse designs: The development and evaluation of a new tool. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(4), 746–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M., Caruso, B. A., Sahin, M., Calderon, T., Cavill, S., Mahon, T., & Phillips-Howard, P. A. (2016). A time for global action: Addressing girls’ menstrual hygiene management needs in schools. PLOS Medicine, 13(2), e1001962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M., Hirsch, J. S., Nathanson, C., & Parker, R. G. (2015). Comfortably, safely, and without shame: Defining menstrual hygiene management as a public health issue. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), 1302–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M., & Sahin, M. (2013). Overcoming the taboo: Advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. American Journal of Public Health, 103(9), 1556–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M., Sutherland, C., & Chandra-Mouli, V. (2015). Putting menarche and girls into the global population health agenda. Reproductive Health, 12(1), 1–3. 10.1186/s12978-015-0009-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumana, Y., Rahoul, D., & Kantharia, S. (2015). Menstrual hygiene: Gaps in the knowledge and practices in adolescent school girls. Journal of Evidence Based Medicine and Healthcare, 2(17), 2487–2492. [Google Scholar]

- Sumpter, C., & Torondel, B. (2013). A systematic review of the health and social effects of menstrual hygiene management. PLoS One, 8(4), e62004. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamiru, S., Mamo, K., Acidria, P., Mushi, R., Ali, C. S., & Ndebele, L. (2015). Towards a sustainable solution for school menstrual hygiene management: Cases of Ethiopia, Uganda, South-Sudan, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. Waterlines, 34(1), 92–102. 10.3362/1756-3488.2015.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, H., Oza, U. N., & Tiwari, R. (2006). Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about menarche of adolescent girls in Anand district, Gujarat. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 12(3–4), 428–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF/World Health Organization (2016). Joint Monitoring Programme for water supply, sanitation and hygiene. UNICEF/World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (2015). A communication framework: Menstrual management. UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (2019). Guidance on menstrual health and hygiene. UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (2015). Post-2015 sustainable development agenda. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/mdgoverview/post-2015-development-agenda.html

- United Nations General Assembly (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. UN General Assembly, 302(2), 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Rights (n.d.). International Human Rights Law . https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/InternationalLaw.aspx

- United Nations Human Rights (n.d.). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of 16 December 1966 entry into force 3 January 1976, in accordance with article 27. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Rights (n.d.). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, New York, 18 December 1979. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cedaw.aspx [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Rights (2000). Substantive Issues Arising in the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. https://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=4slQ6QSmlBEDzFEovLCuW1AVC1NkPsgUedPlF1vfPMJ2c7ey6PAz2qaojTzDJmC0y%2B9t%2BsAtGDNzdEqA6SuP2r0w%2F6sVBGTpvTSCbiOr4XVFTqhQY65auT [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Rights (2003). Substantive Issues Arising in the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. https://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/water/docs/CESCR_GC_15.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, M., Ravichandran, L., & Anandhan, A. K. (2015). Knowledge and practice of menstrual hygiene among school going adolescent. Indian Journal of Youth and Adolescent Health, 3(2), 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Vijaysree, L., Kusneniwar, G., Vaz, L. S., & Rao, S. R. (2016). A study on menstrual practices and hygiene among adolescent girls in a government high school. Indian Journal of Medical Research and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 3, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Walraven, G., Ekpo, G., Coleman, R., Scherf, C., Morison, L., & Harlow, S. D. (2002). Menstrual disorders in rural Gambia. Studies in Family Planning, 33(3), 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (2012). Meeting report of JMP post-2015 global monitoring working group on hygiene. [Google Scholar]

- World Association for Sexual Health (1999). Declaration of sexual rights. https://worldsexualhealth.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Declaration-of-Sexual-Rights-2014-plain-text.pdf