Abstract

Objectives: Despite billions of dollars in funding spent each year on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and HIV programming, sexual pleasure is insufficiently addressed. This paper therefore has three key aims: (1) to introduce the concept of sexual pleasure in SRHR programming, while providing context regarding investment and research, (2) to introduce and situate an upcoming systematic review and meta-analysis to quantify whether and to what extent incorporating sexual pleasure into SRHR interventions can improve health outcomes, and (3) to examine the key practical, methodological, and theoretical challenges in carrying out such a review. Methods: We undertook a literature review and analysis of conference abstract publications to highlight the 'pleasure gap' in evidence in sexual and reproductive health and rights programming and research. We detailed the scope, search strategy and challenges for our subsequent systematic review. Results: This paper and the subsequent review highlights the need to equip the SRHR and HIV fields to better meet the needs of communities by considering key reasons people have sex, and understand the challenges of undertaking a review of this nature. Conclusions: We conclude that this a focus on pleasure is particularly pertinent in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals and the ratification of the declaration on sexual pleasure at the 2021 World Congress of the World Association for Sexual Health.

Keywords: Sexual and reproductive health and rights, HIV & AIDS, sexual health promotion, pleasure, HIV prevention, contraception, family planning

Introduction: the elephant in the room – pleasure taboo

Modern sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR including HIV) programming and services worldwide stand on the shoulders of decades of global commitments, investment, research, advocacy, coordination, and innovation. Today’s programmes have developed over 40 years since the HIV crisis began, and 25 years after the rallying cries for global attention to reproductive health and rights at the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo (United Nations, 2014) and the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (UN Women, 1995). The Millennium Development Goals twenty years ago channeled unprecedented global coordination and resources to addressing daunting global statistics in maternal mortality (Hogan et al., 2010) and HIV (Schouten et al., 2011), and in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals placed even more ambitious SRHR-specific targets in place (Buse & Hawkes, 2015).

The current normative model of sexual health has been based on prevention of ill-health, and fear and deficit based approaches to health, rather than the more holistic model of well-being as defined by WHO’s current working definition of sexual health,

…a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled. (World Health Organisation, 2006)

This paper describes the role and importance of sexual pleasure in SRHR programming, while highlighting its absence, historically; contextualizes an upcoming systematic review and meta-analysis exploring if and the extent to which pleasure inclusive sexual health programmes and sex education improve health outcomes [Prospero ID. CRD42020201822], and outlines some challenges to the review.

Investment in sexual health: the urgent need for all the evidence to improve sexual health

Continued commitments from government and the international community are responsible for the important progress made on SRHR-related outcomes, and ongoing financial and political investments are required to address persistent and emerging health challenges (Box 1). Sexual ill-health is still a significant cause of untimely death, as seen in the latest Global Burden of Diseases report (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators, 2020). This is more marked for lower income countries, with AIDS being the fourth highest cause of death. The Guttmacher-Lancet Commission’s report estimated an annual cost of USD 53.6 billion to meet contraception, abortion, and maternal and new-born care-related needs at WHO-recommended standards, worldwide (Starrs et al., 2018). Separately, an additional USD 25.2 billion would be required to meet HIV-related goals for treatment and prevention scale up, on top of the over half a trillion dollars spent on HIV & AIDS, globally, between 2000 and 2015 (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation [IHME], 2019; Dieleman et al, 2018).

Box 1.

The continued health impact of unsafe sex and ineffective education and services

More than one billion people have a sexually transmitted infection (STI), with an estimated 357 million new infections every year of four STIs: chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and trichomoniasis (WHO, 2019, Newman et al. 2015). Pregnancy and childbirth complications are the leading cause of death among girls aged 15–19 years globally, with low- and middle-income countries accounting for 99% of global maternal deaths of women aged 15–49 years (Vos et al, 2020). Early pregnancies among adolescents have major health consequences for adolescent mothers and their babies (Neal et al., 2012).

More than half of all women of reproductive age in low-income regions want to avoid pregnancy. However, one-fourth of these women, 225 million, are not using an effective contraceptive method (Singh, Darroch, & Ashford, 2014). In sub-Saharan Africa six in seven new HIV infections amongts adolescentss aged 15-19 are among girls. (UNAIDS, 2021a; 2021b).

In September 2015, the General Assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, n.d.). The SDGs 3.7 and 5.6 (UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs) are aimed at ensuring universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights. In 2016, the United Nations General Assembly’s Political Declaration on Ending AIDS committed countries to the 90–90–90 targets, to ensure access to treatment and testing (UNAIDS, 2016).

With so much at stake, SRHR and HIV programming and service delivery strategies have pursued significant innovations and widely disseminated best practices to increase access and adherence to, or uptake of needed SRHR and HIV interventions. These have included addressing economic drivers and gender inequality, improving individual autonomy, comprehensive sexuality education, and tackling widely held taboos about sexual norms, including social stigma around sexual behaviors and accessing services. However, despite the billions of dollars in domestic and donor funding spent each year on SRHR and HIV services and programming, sexual pleasure - a proximal determinant of sexual activity – is insufficiently addressed in most areas of the world (Allen & Carmody, 2012; Arrington-Sanders et al., 2015; Boyce et al., 2007; Fine & McClelland, 2006; Philpott et al., 2006). The Guttmacher-Lancet Commission on SRHR in 2018 acknowledged that certain aspects of sexual health, including sexual pleasure were “largely absent from organized SRHR programmes and their links to reproductive health…understudied”. Action within the gay men, and men who have sex with men community, as well as among sex workers’ communities provide some notable exceptions [Altman, 1988, Patton 1989].

Where is the pleasure in SRHR and HIV prevention?

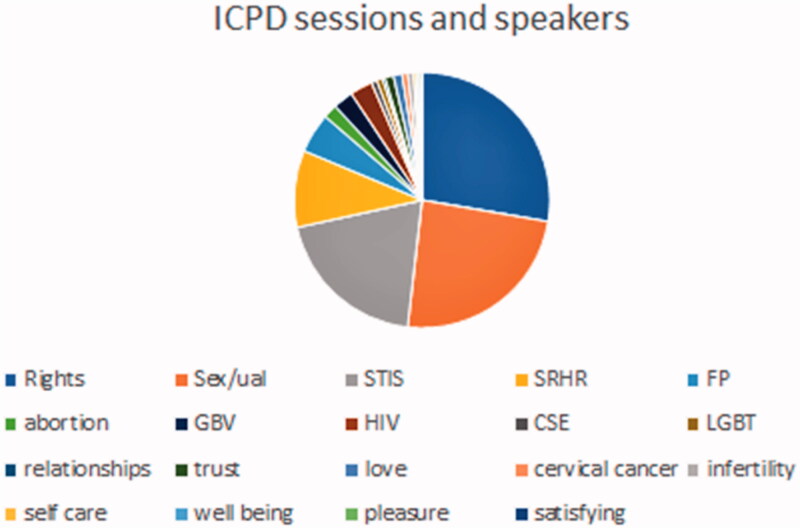

Session Analysis from the AIDS 2020 — The 23rd Global AIDS Conference, International AIDS Society

One way to illustrate just how overlooked sexual pleasure is in the global SRHR discourse is to track its presence (or lack thereof) in key international fora. The Pleasure Project an international education and advocacy organization that works to eroticize safer sex, has tracked pleasure-related content at HIV and SRHR conferences since 2004 (The Pleasure project, 2021).

The Pleasure Project’s search of the International AIDS Society abstract archive from International Conferences on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment & Prevention and International AIDS Conferences from 2001 until 2016, finds that out of a total of 67,500 abstracts, only 352 (0.52%) are returned when searching for keyword “pleasure”. Given the acceptance of pleasure and well-being as a key motivator for sexual activity (World Association for Sexual Health [WAS], 2008), and its place in the working definition of sexual health, by WHO, the World Association for Sexual Health and other bodies – this is all the more striking in its absence. For contrast, a search for “disease” returns 10519 abstracts, “death” 4262, “HIV” 63963, “sex” 25560, and “condom” 9565.

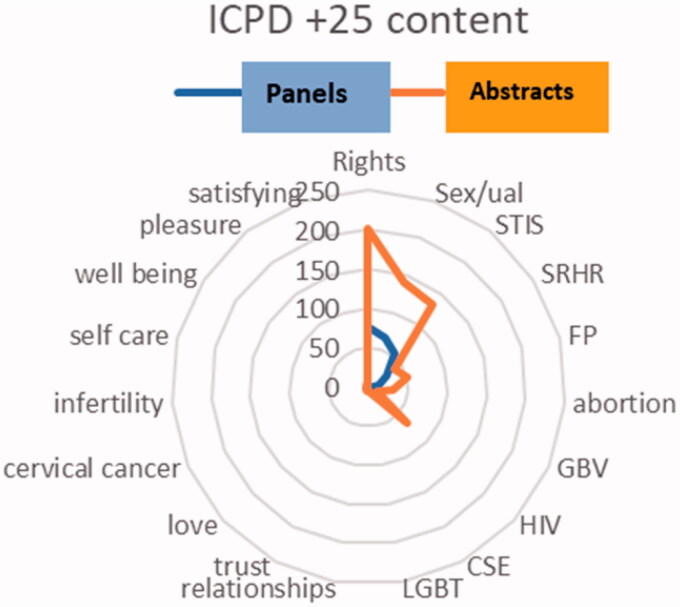

Analysis of abstracts using key word search of abstract database at the 22nd International AIDS Conference, Amsterdam The Netherlands.

Only 31 of those 352 abstracts highlight pleasure in a positive or innovative way to promote sexual health. A large proportion of the other 352 fall under the categorization of “pleasure has a price”, and many focus on perceptions that condoms reduce pleasure.

The ICPD + 25 Conference in Nairobi in 2019 had one session that mentioned pleasure out of 278 (0.3%) and a mere 1 abstract out of 713 (0.003%). A 2014 UNFPA review of progress by the UN General Assembly highlights progress in all areas of reproductive health and rights, and yet it is dominated by data on contraception, HIV and childbirth. There were no mentions of satisfaction, pleasure or desire as part of health. In development as a whole, the lack of recognition of pleasure, well-being or desire continues. For example, amongst the 247 SDG indicators there are no references to pleasure or joy or well-being, and the health targets are predominantly “deficit” focused.

Analysis of Sessions for Key Words at the 25th Anniversary of the International Conference on Population and Development, held in Nairobi, Kenya 2019

This lack of attention to a primary motivator for sexual behavior reflects a politically uncontentious, ill-health and bio-medicalized “treatment” focus of programming and policy. It also reflects a related lack of funding tied to research that can uncover and highlight more effective ways to prevent the unwanted negative outcomes of sex. In the literature,notable work at the beginning of the AIDS pandemic highlighted the importance of addressing sexual motivations, cultures of sexuality, and reduction of stigma (Vance, 1992; WRAP, 1989; Watney, 1986; Altman, 2001; Altman, 1988). More recently, a literature review examined evidence on how and why pleasure and sexual wellness are key to sexual health (Knerr & Philpott, 2008a), illustrating the need to address stigma toward specific interventions alongside of stigma toward sexual behavior and specific groups (Stangl, et al, 2019).

Analysis of Sessions and Panel for Key Words at the 25th Anniversary of the International Conference on Population and Development, held in Nairobi. Kenya 2019.

A new pleasure dawn with a rising pleasure wave

In recent years, sexual pleasure as an important component of SRHR has made some meaningful appearances in the field. Despite a lack of a specific focus on sexual well-being, the SDG around health is inclusive of “well-being” broadly, and includes a specific target focused on ensuring universal access to sexual and reproductive health care services. This resulted in renewed attention to sexual as well as reproductive health, and a need to describe the corresponding “health care services” referenced in SDG 3.7. As such, in 2017, WHO published an operational framework describing the intervention areas which comprised “comprehensive” sexual and reproductive health services. Several months later, the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission’s report (Starrs et al., 2018) highlighted a complementary set of essential SRH interventions along with a new, integrated definition of sexual and reproductive health and rights that includes pleasure, which emphasizes that,

a positive approach to sexuality and reproduction should recognise the part played by pleasurable sexual relationships, trust, and communication in the promotion of self-esteem and overall well-being.

This integrated definition also underscores the right of all individuals to have safe and pleasurable sexual experiences, among other sexual and reproductive rights. The revised UN International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education (UNESCO et al., 2018) also promotes learning about sex and relationships in a manner that is positive and affirming (See Box 2).

Box 2.

The links between Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) and Pleasure

There is an intrinsic link between prevalent social and gender norms around sexuality and the way in which sexual health and education programmes, including CSE programmes, are designed. The purpose of sexual health and education programmes is often to transform social and gender norms around sexuality, and change behaviors related to gender and sex that are harmful, discriminatory and non-inclusive. However, rather than highlighting the diversity of sexual experiences that are possible and challenging the norms that control, regulate or repress sexuality, they are often executed in a manner that reinforces negative aspects of sexuality, over-emphasizing risk prevention, and focusing on the dangers of engaging in particular kinds of sex. Therefore, they do not contribute to reducing or transforming structures of power, oppression and social inequality. As documented by the International Planned Parenthood Federation,

“To exclude elements of positivity and pleasure from CSE programmes creates a disproportionate focus on the negative health and emotional consequences of sex, which risks reinforcing notions that power inequalities, abuse, coercion and violation are, and will always be, the norm.” (IPPF, 2016)

The idea of pleasure as a desirable and important possibility in sexual situations also ensures that problematic myths like virginity and painful sexual debut are tackled. Girls and boys would be taught to expect pain-free (especially for girls) and pleasurable sexual activity that is related to consent and open communication, as well as being safe and satisfying. After all, the discussion on “pleasure” is not completely alien to sexuality education curricula which have often focused on puberty education where changes in girl’s bodies are discussed in terms of menstruation while boy’s bodily changes are related to with discussions on erections, ejaculations and wet dreams; thus, reinforcing the patriarchal, heteronormative narrative that sexual pleasure is a male domain (IPPF, 2016). CSE that emphasizes the diverse forms that pleasure can take enables learners to understand that there are no “binaries” of “good” or “bad” sexual behavior. Instead, there are several factors – as explained in the next section – that influence whether or not a certain encounter feels satisfying, safe and pleasurable to those involved. This also helps learners more easily identify when they are in an unsafe situation, facing unacceptable behavior, abuse or violence, or in a relationship that is making them vulnerable or at-risk.

A sex-positive approach to CSE [IPPF 2016] must necessarily be accompanied with discussions on gender and power as these concepts are intricately linked. Gender-focused CSE programmes are substantially more effective especially when they include transformative content and teaching methods that support students to question social and cultural norms around gender and to develop gender equitable attitudes (UNESCO et al., 2018). The intersection of sex-positive discussions of sexuality with sexual health and sexual rights ensure that learners’ citizenship skills are strengthened toward building a more just and equal sexual culture (IPPF, 2016). One that challenges stereotypes that reinforce damaging norms that masculinity is enhanced by sexual pleasure and femininity is diminished or threatened by it.

In addition, Singh and Philpott have defined a pleasure – based approach as moving further forward from the IPPF sex-positive approach and one that “celebrates sex, sexuality and the joy and well-being that can be derived from these, and creates a vision of good sex built on sexual rights. It focuses on sensory, mental, physical and sensual pleasure to enable individuals to understand, consent to, and gain control over their own bodies and multi-faceted desires. Well-being, safety, pleasure, desire and joy are the objectives of a programme with a pleasure-based approach. This approach measures empowerment, agency, and self-efficacy by whether or not an individual has been enabled to know what they want, and can ask for it, and request this of others, in relation to their sexuality, desires and pleasure.” (Singh & Philpott, 2019)

In 2019, the World Association for Sexual Health (WAS, 2019) (Ford et al, 2019) sexual pleasure declaration further elevated sexual pleasure within the broader SRHR community. Here, participants of the 24th World Congress of the World Association for Sexual Health in Mexico recognized sexual pleasure as integral to sexual health in declaring that, “the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences free of discrimination, coercion, and violence is a fundamental part of sexual health and well-being for all”. The declaration points to the importance of comprehensive sexuality education addressing sexual pleasure in an inclusive, evidence-informed and rights-based manner in order to allow experiences of informed, self-determined, respectful, and safe sexual pleasure; and underlines that sexual pleasure is integral to sexual health care services provision or digital information provision In 2021, at the WAS Global Congress this Sexual Pleasure Declaration was ratified by WAS members.Others have provided tools to enable discussion of pleasure between client and professional for effective health service provision [Castellanos - Usigli, A & Braeken-van Schaik, D. 2019, Jolly et al, 2020, Van Clief & Anemaat, 2020]

Finally, emerging evidence has tied elements of sexual health and sexual pleasure specifically to overall mental and physical well-being (Whipple, 2007 ; Gainotten, 2021 in review). As such, comprehensive health services should include health promotion services which are inclusive of sexual pleasure, to ensure both effective public health for the large burden of sexual health disease as well as enhance sexual well-being.

Pleasure during a pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic elevated sexual pleasure into the public discourse in many countries, as health authorities issued frank guidance on COVID-safe sexual activity. With penile-vaginal intercourse (as well as other forms of in-person sexual activity) inadvisable in COVID-19-affected households or communities and a need for detailed, pandemic-related guidance, health authorities made headlines with recommendations on: multiple types of partners; use of sex toys (Government of the District of Columbia, 2020; Government of Colombia Ministry of Health and Social Protection, 2020); masturbation (Sexual Health and Crisis Pregnancy Programme, 2021); consensual cybersex activity (Government of Colombia Ministry of Health and Social Protection, 2020). Sex toy companies have reported increased sales (Chazan, 2020), the use of which has been largely accepted as a necessary form of safer sex.

Tacitly acknowledged by these pandemic-era recommendations is the fact that, in addition to being a central driver of sexual behavior, sexual pleasure is also an element of overall well-being (Edwards & Coleman, 2004; Hull, 2008; WAS, 2008). Devoid of the emphasis on reproductive health (and even disease transmission, in the case of solo or distanced sexual activities), these recommendations instead, directly or indirectly, addressed the ongoing need for intimate connection, sexual desire, and sexual pleasure.

Need for further evidence: the extent to which sexual pleasure-inclusive interventions improve sexual health

It is imperative to recognize that sexual rights, as fundamental human rights, are an essential component for human development (WAS, 2008, 2014; IPPF, 2008). Explicit inclusion of sexual pleasure as a necessary corollary of sexual rights and sexual health strengthens human rights protections and expands public health programming to address sexuality as a personal and social asset rather than simply a health challenge to be prevented or resolved (Gruskin et al., 2019).

There are, therefore, several reasons to test the current wave of “sex-positivity”, which is embracing sexual pleasure’s tie to sexual activity and sexual practices (solo or partnered), and evidence the integration of sexual pleasure into SRHR related education, promotion, policies, programmes, and services. One previous systematic review and meta-analysis, conducted in 2006 and the most comprehensive review of the evidence to date, demonstrated the value-add of incorporating sexual pleasure into HIV-prevention interventions (Scott-Sheldon & Johnson, 2006). This meta-analysis examined the effectiveness of sexual risk reduction interventions in 21 studies that integrated a safer sex eroticization component. Eroticization was defined as any sexually arousing, exciting, or pleasurable material that was used to promote safe sexual behavior. Compared to controls, intervention participants exhibited lower sexual risk on six dimensions: HIV-related knowledge, attitudes toward condoms, condom use, overall behavioral risk, communication with sexual partners, and sexual frequency. Additional analyses showed significant improvement in condom use in the intervention compared to the control groups. Overall, findings suggested that eroticizing safer sex leads to more risk-preventive attitudes, which in turn facilitates less risky sexual behavior.

Today’s unprecedented attention and openness to sexual pleasure in sexual health domains is occurring simultaneously with sustained political and ideological resistance to comprehensive SRHR information and services (let alone sex-positive information and services) (Newby & Philpott, 2018; Philpott et al, 2017). As such, in 2020 we initiated an update and expansion of the Scott-Sheldon review and meta-analysis, also building on The Pleasure Project’s literature review (Knerr & Philpott, 2008a), in the hope of equipping the SRHR and HIV fields to better meet the needs of communities by considering key reasons people have sex.

Scope of our review: impact of pleasure inclusiveness on SRHR outcomes

In the subsequent sections, we describe the scope of the review and spotlight key methodological challenges we’ve encountered that illustrate the challenges of conceptualizing (let alone including) sexual pleasure considerations in relevant health programmes and services. We detail how we have addressed these challenges for the purposes of the review and conclude with several recommendations.

Review scope

The review will focus on the literature since Scott-Sheldon (i.e. from 2005) and is intended to answer the question: Do sexual and reproductive health interventions which incorporate sexual pleasure improve relevant health outcomes? Our hypothesis is that incorporating considerations or concerns around sexual pleasure, this key driver of sexual activity and sexual satisfaction, into SRHR interventions will result in better SRH-related outcomes.

As described by the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission, “sexual and reproductive health interventions” is a broad concept which could conceivably capture menstrual hygiene to menopausal symptoms management, gender-based violence prevention to fertility treatment. As such, we have opted to narrow our focus to two specific types of interventions: pregnancy prevention and HIV/STI prevention interventions.

Our reason for this is two-fold. First, as described above, family planning and HIV interventions have decades of history and longstanding international agreements supporting them. While other interventions in the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission package are only beginning to receive attention (e.g. fertility treatment and sexual functioning services), interventions and best practices to prevent HIV (and STIs, to a lesser extent) as well as unwanted pregnancy are well-documented. Second, as part of this documentation, there is a better understanding of how sexual pleasure considerations can impact pregnancy-prevention and HIV-prevention efforts. There has been some exploration of “sexual acceptability” of contraceptives, i.e. how they influence a user’s sexual experiences (including sexual pleasure, sexual desire, sexual arousal, etc.) (Higgins & Hirsch, 2008; Boozalis 2016). The perception that HIV/STI-prevention barrier methods like the external or internal condom reduce sexual pleasure is an oft-cited reason for nonuse or “incomplete use” (Crosby et al, 2008). Meanwhile, the increasing availability of pre-exposure prophylaxis has introduced debate around “appropriate” reasons for use (sexual pleasure not being one of these) (Calabrese & Underhill, 2015). In short, for HIV/STI and pregnancy prevention interventions, there is enough of a sexual pleasure link to believe that these considerations may have been incorporated in interventions over the last 15 years, and enough funding, research, and innovation for it to have been possible.

Review criteria and approach

Eligible studies will be intervention studies with a control group, either randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies, with both pre- and post- intervention measurements. One intervention arm will need to contain at least one component that incorporates pleasure. We require that the intervention manual or corresponding published manuscript makes a direct mention of incorporating pleasure that is in line with the definitions for pleasure proposed by the Global Advisory Board for Sexual Health and Wellbeing (GAB, 2016) and adopted by the World Association for Sexual Health (WAS, 2019). In order to isolate the role of pleasure, we require that another arm provides a comparison measure. This can be either a pure or matched control or “usual SRH care’ that does not incorporate pleasure. Single group studies, post-measurement-only comparisons between groups, cross-sectional studies or any other nonintervention observational studies are excluded. Full outcomes of interest are described elsewhere (Larrson et al, 2020), but included are contraception and condom use (as well as attitudes toward and acceptability of use), sexual behavior, use of STI/HIV and pregnancy prevention services, etc. With these criteria, the aim is that a meta-analysis will determine (1) whether pleasure-inclusive interventions work; and (2) the added value of pleasure-inclusive interventions as compared with usual SRHR care. We will narratively synthesize results in a systematic review as well provide a random effects model aggregating effect sizes in a meta-analysis. Our review will follow PRISMA guidelines and is pre-registered on Prospero (ID: CRD42020201822), where further methodological details can be found.

Identifying relevant SRHR interventions in terms of design and appropriate outcomes was a relatively straightforward part of the review protocol’s development. By contrast, determining what was meant by incorporation of pleasure (and how reviewers could objectively and systematically identify pleasure-inclusive interventions) was not straightforward. Despite the fact that we considered what constitutes pleasure incorporation through existing definitions (i.e. those proposed by WAS (2019) and GAB (2019) we have encountered several key challenges in “operationalizing” this approach for the purposes of this literature review, which we assert are demonstrative of the previous lack of attention to sexual pleasure in SRH programming. We describe these below, along with measures we have taken to mitigate these.

The complication of locating “pleasure” in SRHR interventions

How do we search for pleasure inclusive interventions?

Search strategy challenges

A key challenge in carrying out a systematic review of pleasure in SRHR emerges at the very outset – the lack of a universally-accepted (UN or global body adopted) definition of sexual pleasure. This signifies by extension a lack of well-articulated, appropriate search terms. Every systematic review, regardless of topic, requires that a series of search terms are queried in a number of selected relevant research databases. Both main types of search terms, that is keywords or subject headings, bring about unique difficulties in the context of pleasure inclusive work.

First, subject headings are often the preferred approach for many clinical topics. They are products of carefully controlled and organized vocabularies, such as the one led by the National Library of Medicine, which has produced PubMed’s MeSH terms. Subject headings are used to index, catalogue, and structure recently published scientific articles. This process requires shared definitions of a given subject matter to exist. In the context of well-established topics or discernible diagnoses (such as HIV), indexing is a straightforward task. Conversely, in areas where there is less attention or consensus, indexing is far more difficult, as for example, in the case of “Sexual Health, which only became a MeSH term in 2018”. In the context of sexual pleasure or sex-positive research, a greater degree of ambiguity exists regarding an operational definition. This lack of consensus means that suitable subject headings either do not exist or are not used in a consistent manner.

The initial efforts made by the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission (2018), the World Association for Sexual Health (2019) and the International Planned Parenthood Federation (2016) to define pleasure and sex-positivity are fundamental in advancing our ability to discuss sexual pleasure within a common framework, as well as to systematically identify work that promotes it. Nevertheless, substantial work lies ahead before existing definitions can be unified and applied by researchers globally, and there is further lag time (and effort required) for such definitions to be translated into appropriate subject headings consistent across multiple databases.

Second, single keywords may also be queried as part of a systematic review. These pose additional challenges given the diversity of ways in which sex-positive interventions or pleasure inclusive work may be described. A researcher may be tempted to query for “sex positive*” “sex feminis*”, “pleasur*” or “erotic*” but such a narrowly defined set of keywords will likely lead to omissions of relevant work. A next step might be to include adjectives associated with pleasure inclusive approaches such as sexy, affirming, rewarding, accepting, satisfying, empowering, exciting, passionate, arousing. Including additional terms will exponentiate the number of papers returned, but none of these keywords on their own will guarantee a given work is sex-positive or that other, more relevant publications, are not omitted.

Our approach

Unlike many clinical or health-oriented reviews, we do not rely solely on subject headings in our search strategy as these cannot capture sex-positive terms sufficiently well. Further, given that indexing new research articles with appropriate headings takes additional time, any approach relying solely on subject heading is likely to be unable to capture the most recently published research. Instead, we combine subject headings and key terms in order to be able to cast a wider net and not miss any relevant publications.

We do not include key terms for pleasure or associated terms for sex-positivity. Instead, we have queried the full set of SRHR interventions that fall within the scope of our review. This includes those pertaining to HIV, reproductive health, pregnancy and family planning, sexually transmitted diseases, safe sex and contraception. In order to limit this expansive search, we also use proximity operators to specify our required context – that of prevention and control. We further manage our search by querying for the relevant experimental designs (e.g. randomized controlled trials, pseudo-randomized trials, matched trials, quasi experimental designs). Additionally, we do not apply exclusion criteria based on population or participant characteristics. We further supplement our main search approach with a secondary search, that includes contacting known researchers, reference tracking, and querying Google Scholar. All of these decisions taken together necessarily mean that we will obtain a very large set of results. As a consequence of the increase in number of results, a prolonged period of abstract and full text screening will be required. We have taken this approach in order to be as fully inclusive as possible. We believe that such theoretically informed, methodologically rigorous efforts are more than justified in order to obtain a meticulous full perspective of the effects of sex-positive, pleasure inclusive interventions.

How do we identify pleasure inclusive interventions?

Screening challenges

The different ways interventions are described poses a further difficulty for identifying work that incorporates pleasure. On a surface level, we can separate interventions in two categories: those that state they have carried out pleasure inclusive work explicitly and those that make no such mention. For as simple as such a division could be, even this type of separation can be heavily influenced by factors such as publication bias, politics, funding, and journal requirements. For instance, publication bias, a type of bias in the context of academic publishing, pertains to situations when the outcomes or features of a given study may influence the decisions whether or not to publish. It is possible that publication bias exists in the context of pleasure inclusive interventions such that programmes that are described in neutral language, excluding pleasure, are more likely to be published. This may in turn signify that authors could, intentionally or unintentionally, omit mentioning pleasure to fit in with the existing published literature, which makes finding pleasure inclusive literature even more difficult in the context of a systematic review.

Further, political reasons may also influence the way interventions are described, especially from periods where funding could have been dependent on conservative guidelines. With such considerations, authors would be less likely to describe their work in ways that do not align with their funding body’s expectations and common narratives in SRHR and HIV/AIDS research, as evidenced earlier in this paper. Additionally, we also anticipate that in cases where small components of the overall interventions incorporate pleasure to some degree, limitations arising from academic journals, such as allotted word counts, will decrease the likelihood that an explicit mention of pleasure is made. Some authors may consider such small components to be too tangential to the intervention’s overall aims and outcomes in order to justify including a dedicated detailed description. Taken together, these issues speak to the difficulty of identifying the full set of pleasure inclusive or sex positive work during the screening stage of a systematic review.

Our approach

Provided that vast differences in write-up and description of interventions are present in the field (as outlined above), we did not screen for pleasure incorporation on the abstract stage. We believe that such a screening would exclude a significant number of publications that may describe the relevant components in the main text (e.g. in their Methods section). Instead, for the abstract screening, we only check for relevance in terms of appropriate interventional design and topic.

We divide our full text screening in two stages: in the first we read full texts and exclude those that do not meet our criteria for design, topic, outcomes. Additionally, we look for mentions of sex-positivity or pleasure inclusive work. For this stage, we consider any mention or context of pleasure focused work sufficient. As long as a paper provides a mention of sex-positivity, we retain it for further discussion. As part of our due diligence for this stage, if a publication states that a full description of methods or interventional implementation is available in an earlier publication (e.g. protocol, feasibility trial) or in supplementary materials available elsewhere, we commit to reading and assessing the information included from such additional sources.

Then, in a second stage of full text screening, all reviewers have to agree that the remaining papers meet our standards for work that incorporates pleasure and are in line with existing definitions by the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission (2018), WAS (2019) and GAB (2019) as a minimum. The raters met to discuss this inclusion and agreed that any mention of pleasure as motivation for safer sex, pleasure in the context of sexual health and pleasure as an intervention or tool would qualify for inclusion. This enabled a wider range of interventions that encompassed pleasure-inclusive sexual health, sex positive sexual health or at a smaller scale a safer sex component [e.g eroticising condom use] within a wider experiment would be included. Therefore, density was broad. Further details will be available on this “ladder of pleasure inclusive sexual health” within the systematic review. Again, this two-stage full screening strategy means additional effort is put in screening and extra time is spent in consensus meetings, but we take this approach in order to obtain a full, holistic picture of the available evidence regarding the effects of sex-positive interventions.

Lastly, for all screening stages, our review process involves 5 independent raters with different areas of practical and theoretical expertise regarding sexual health and systematic review methodology. Most systematic reviews involve only two raters but we have chosen to carry out our screening with an interdisciplinary team of health and research professionals in order to minimize bias and ensure a greater level of rigor. We summarize the main issues, challenges, and our approach in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Issues in this Review.

| Main issue | Challenge for systematic review | Our approach |

|---|---|---|

| How do we search for pleasure inclusive interventions? | ||

| Lack of universally accepted definitions or key terms for research that is sex positive or incorporates pleasure |

|

We do not query for sex-positive or pleasure terms in our search. Instead, we take on an expansive search strategy approach, whereby we incorporate both subject headings and key terms and look for suitable sexual health interventions. Sex-positive and pleasure incorporating interventions will be a subset of all sexual health interventions and will thus be captured by our search. |

| How do we identify interventions that incorporate pleasure? | ||

| Sex-positive/pleasure incorporating components may not be described in a given publication |

|

We commit to reading additional literature and materials, including protocols, feasibility reports, and supplementary materials in order to have a higher chance of capturing all the relevant information for a given trial. |

| Sex-positive/pleasure incorporating components may be described in different sections of a publication |

|

We do not screen for the inclusion of sex-positive or pleasure incorporating work during the abstract screening stage. For this stage, we only screen for publications that are relevant in terms of topic and methods. This means a high number of papers will be retained for full text screening. |

| Sex-positive / pleasure incorporating components will likely be described in a variety of ways |

|

We divide our full text screening in two stages. During the first, we accept any mentions of work that incorporates pleasure. During the second, our team engages in thorough discussions of each paper to ensure it meets our definitional criteria for work that incorporates pleasure, and ensure the outcomes of SRHR improvements are measured. We further employ a team of 5 cross-disciplinary specialists to ensure a wide variety of backgrounds and experiences from sexual and public health, as well as systematic review methodology, are represented. |

In addition to the challenges above we are challenged by the likelihood that more proximal or indirect determinants of sexual health behavior are wide and structural: such as self-esteem, gendered expectations of sexual relationships, legal statuses of sexual behavior based on sexual identity, traumatic experiences of sex through a young person’s life and so on. In recent years, there has been an increase in holistic, multi-level interventions that could affect a person’s acceptance of sex-positivity and sexually healthy behavior in both a mental and physical sense. These include interventions which may define themselves as “sex-positive” (very broadly defined), women-empowering/self-efficacy-boosting, human-rights based, or more broadly focus on gender inequality, economic empowerment, and broader intimacy and relationship skills-building. Pleasure theoretically could be a component of all of these; however, for this review, it may be difficult to clearly identify the inclusion of sexual pleasure. Alternatively, if included in one of these broader programmes of many components, we may not be able to attribute changes in outcomes to the inclusion of sexual pleasure alone.

Conversely, we may see consideration of pleasure in a potentially “sex-negative” intervention (Tanner & Pollack, 1988). For example, an intervention that only highlights eroticization where the female partner in a heterosexual relationship is being shown how to put a condom onto a penis erotically and explain to the man that it can feel good. Or a hyper-sexualised image of a woman is used to sell condoms. Although that is indeed a use of pleasure in safer sex education (and therefore warrants inclusion in this review), we recognize that it has been with adherence of patriarchal and sexist norms of privileging male pleasure, and training or objectifying only women to enhance it. We also recognize that there is a relationship between empowerment and more pleasurable safer sex, e.g. people who have a positive view of sexuality or are confident in knowing and expressing what they want in sex, are more likely to use condoms (Knerr & Philpott, 2008a).

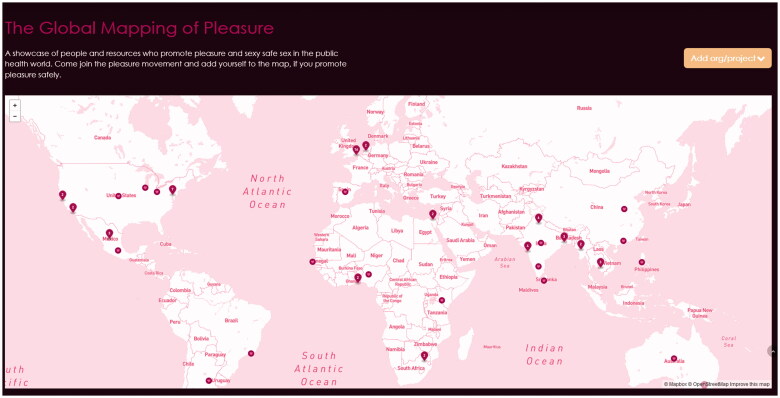

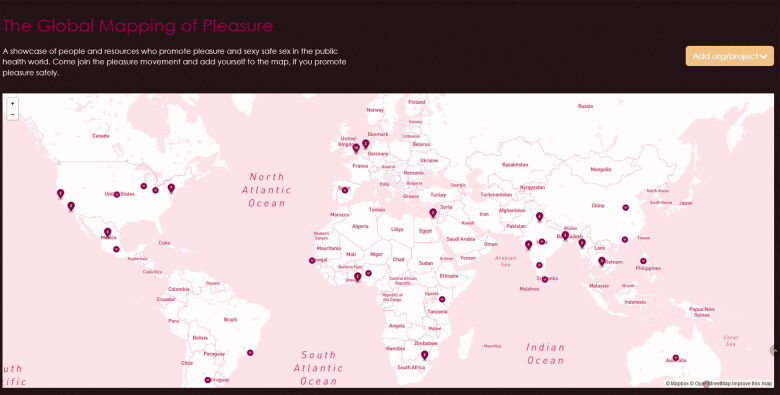

Conclusion: Surfing the Pleasure Wave

This systematic review complements an expanded detailing of emerging best practise on sex-positive and pleasure inclusive safer-sex initiatives (including many geographies, communities and groups) of how safer sex and sex education can be promoted in a positive way by considering the role of pleasure and desire in sexual behavior. These are now housed as an online “Pleasure Map” on The Pleasure Project website (The Global Mapping of Pleasure - The Pleasure Project 2021). This has grown from an original documentation in 2005 of 15 examples of people (Knerr, W, 2008) and organizations that incorporated pleasure into their health work into a map with 95 cases listed in 2021. Work has also continued to analyse the extent to which pleasure can be positvely incorporated into sex education in Kenya and Ghana (Singh et al., 2021).

However, the process of running this review and the immediate challenges encountered even in formulating a search illustrates just how much sexual pleasure has been intentionally and inadvertently overlooked in public health programming to date. Far from “not enough” attention to sexual pleasure, there continues to be a lack of even agreed-upon definitions and keywords to capture pleasure-inclusive “good practices” where they happen. A thorough scan of the literature so far reflects western ideologies of biomedical disease prevention and emphasis on risk-reduction rather than enhancing well-being and aspiring toward achieving pleasurable, healthy, consensual sexual experiences.

This review will be completed and submitted for publication during 2021. Toward the end of that year, the WAS General Assembly has ratified the declaration on sexual pleasure at their World Congress. This review was initiated in order to describe and quantify the value-add that incorporating sexual pleasure can bring to sexual and reproductive health and rights programming. However, the process of even designing and implementing the review already points to immediate next steps needed following the Declaration: consensus around and support to define, incorporate, and evaluate effective sexual pleasure components in programmes.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

References

- Allen, L., & Carmody, M. (2012). Pleasure has no passport: Re-visiting the potential of pleasure in sexuality education. Sex Education, 12(4), 455–468. 10.1080/14681811.2012.677208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D., (1988). Legitimation through disaster: AIDS and the gay movement. In Fox E. & Fox D. M. (Eds), AIDS: The burdens of history. University of California Press, c1988. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D. (2001). Global sex. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arrington-Sanders, R., Morgan, A., Ogunbajo, A., Trent, M., Harper, G., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2015). The role of sexually explicit material (SEM) in the sexual development of Black young same-sex-attracted men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(3), 597–608. 10.1007/s10508-014-0416-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boozalis, A., Tutlam, N. A., Robbins, C. C., & Peipert, J. F. (2016). Sexual desire and hormonal contraception. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 127 (3), 563–572. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, P., Lee, M., Jenkins, C., Mohamed, S., Overs, C., Paiva, V., Reid, E., Tan, M., & Aggleton, P. (2007). Putting sexuality (back) into HIV/AIDS: Issues, theory and practice. Global Public Health, 2(1), 1–34. 10.1080/17441690600899362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse, K., & Hawkes, S. (2015). Health in the sustainable development goals: Ready for a paradigm shift? Globalization and Health, 11(1), 13. 10.1186/s12992-015-0098-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, S. K., & Underhill, K. (2015). How stigma surrounding the use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis undermines prevention and pleasure: A call to destigmatize “truvada whores”. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), 1960–1964. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Usigli, A., & Braeken-van Schaik, D. (2019). The Pleasuremeter: Exploring the links between sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure in sexual history-taking, SRHR counselling and education. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(1), 1–315. 10.1080/26410397.2019.1690334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazan, G. (2020, 2 April). Condoms and sex toys in demand from social isolators. Financial Times. Retrieved December 2020, from https://www.ft.com/content/80e11807-3e0d-4867-9b42-bbe959a071a9

- Crosby, R., Milhausen, R., Yarber, W. L., Sanders, S. A., & Graham, C. A. (2008). Condom 'turn offs' among adults: An exploratory study. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 19(9), 590–594. 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieleman, J. L., Haakenstad, A., Micah, A., Moses, M., Abbafati, C., Acharya, P., Adhikari, T. B., Adou, A. K., Ahmad Kiadaliri, A., Alam, K., Alizadeh-Navaei, R., Alkerwi, A., Ammar, W., Antonio, C. A. T., Aremu, O., Asgedom, S. W., Atey, T. M., Avila-Burgos, L., Awasthi, A., … Murray, C. J. L. (2018). Spending on health and HIV/AIDS: Domestic health spending and development assistance in 188 countries, 1995–2015. The Lancet, 391(10132), 1799–1829. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30698-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, W. M., & Coleman, E. (2004). Defining sexual health: A descriptive overview. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(3), 189–195. 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000026619.95734.d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J. V., Vargas, E. C., Finotelli, I. J., Fortenberry, D., Kismödi, E., Philpott, A., Rubio-Aurioles, E., & Coleman, E. (2019). Why pleasure matters: Its global relevance for sexual health, sexual rights and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 217–230. 10.1080/19317611.2019.1654587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, M., & McClelland, S. I. (2006). Sexuality education and desire: Still missing after all these years. Harvard Educational Review, 76(3), 297–338. 10.17763/haer.76.3.w5042g23122n6703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Global Advisory Board. 2016. https://www.gab-shw.org/our-work/workingdefinition-of-sexual-pleasure/ [Accessed 120721]

- Gainotten . (2021). International Journal of Sexual Health. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1204–1222. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Advisory Board. (2016). https://www.gab-shw.org/our-work/workingdefinition-of-sexual-pleasure/

- Government of Colombia Ministry of Health and Social Protection. (2020). ABC on sexual intercourse and Coronavirus disease (covid-19). https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/ABC-sobre-las-relaciones-sexuales-y-las-enfermedades-por-coronavirus-(COVID-19).aspx

- Government of the District of Columbia. (2020). Sex during the COVID-19 public health emergency. https://coronavirus.dc.gov/sex

- Gruskin, S., Yadav, V., Castellanos-Usigli, A., Khizanishvili, G., & Kismödi, E. (2019). Sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure: Meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(1), 1593787. 10.1080/26410397.2019.1593787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. A., & Hirsch, J. S. (2008). Pleasure, power, and inequality: Incorporating sexuality into research on contraceptive use. American Journal of Public Health, 98(10), 1803–1813. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, M. C., Foreman, K. J., Naghavi, M., Ahn, S. Y., Wang, M., Makela, S. M., Lopez, A. D., Lozano, R., & Murray, C. J. (2010). Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: A systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. The Lancet, 375(9726), 1609–1623. 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull, T. H. (2008). Sexual pleasure and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health, 20(1–2), 133–145. 10.1080/19317610802157234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). (2019, August 25). Financing global health 2019: Tracking health spending in a time of crisis. IHME. http://www.healthdata.org/policy-report/financing-global-health-2019-tracking-health-spending-time-crisis.

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. (2016). Putting sexuality back into comprehensive sexuality education: Making the case for a rights-based, sex-positive approach. https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/2016-10/Putting%20Sexuality%20back%20into%20Comprehensive%20Sexuality%20Education_0.pdf.

- Jolly, S., Oosterhoff, P., Faith, B., Braeken, D., & Shephard, K. (2020). Background paper prepared for the section of Health and Education at UNESCO: A review of the evidence: Sexuality education in the digital space. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373885/PDF/373885eng.pdf.multi

- Knerr, W., & Philpott, A. (2008a). Everything you wanted to know about pleasurable safer sex but were afraid to ask: Twenty questions on sex, pleasure and health. https://thepleasureproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TPP-20-Questions_v6.pdf.

- Knerr, W., & Philpott, A. (2008b). The Global Mapping of Pleasure: A directory of organizations, programmes, media and people who eroticize safer sex. The Pleasure Project. https://www.gov.uk/research-for-development-outputs/the-global-mapping-of-pleasure-a-directory-of-organizations-media-and-people-who-eroticize-safer-sex

- Larrson, G., Gonsalves, L., Askew, I., Philpott, A., Singh, A., Sunderland, G., & Zaneva, M. (2020). Addressing sexual pleasure in the context of sexual health interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. National Institute for Health Research. International prospective register of systematic reviews. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020201822.

- Neal, S., Matthews, Z., Frost, M., Fogstad, H., Camacho, A. V., & Laski, L. (2012). Childbearing in adolescents aged 12-15 years in low resource countries: A neglected issue. New estimates from demographic and household surveys in 42 countries. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91(9), 1114–1118. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby, K., & Philpott, A. (2018). The eroticization of condom use: Could porn be used to have a positive impact on public health? Porn Studies, 5(2), 204–207. 10.1080/23268743.2018.1434161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, L., Rowley, J., Vander Hoorn, S., Wijesooriya, N. S., Unemo, M., Low, N., Stevens, G., Gottlieb, S., Kiarie, J., & Temmerman, M. (2015). Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLOS One, 10(12), e0143304. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304 PMID: 26646541; P MCID: P MC4672879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, C. (1989). Resistance and the erotic. In Aggleton P., Hart G., & Davies P. (Eds.), AIDS: Social representations, social practices. London Falmer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Philpott, A., Knerr, W., & Maher, D. (2006). Promoting protection and pleasure: Amplifying the effectiveness of barriers against sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy. The Lancet, 368(9551), 2028–2031. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69810-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott, A., Singh, A., & Gamlin, J. (2017). Blurring the boundaries of public health: It’s time to make safer sex porn and erotic sex education. Institute of Development Studies Bulletin Sex Education in the Digital Era, 48 (1), 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten, E., Jahn, A., Midiani, D., Makombe, S., Mnthambala, A., Chirwa, Z., Harries, A., Oosterhout, J., Meguid, T., Ben-Smith, A., Zachariah, A., Lynen, L., Zolfo, M., Van Damme, V., Gilks, C., Atun, R., Shawa, M., & Chimbwandira, F. (2011). Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the health-related Millennium Development Goals: Time for a public health approach. The Lancet, 378(9787), 282–284. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62303-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon, L., & Johnson, B. (2006). Eroticizing creates safer sex: A research synthesis. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 27(6), 619–640. 10.1007/s10935-006-0059-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon, L., Marsh, K., Johnson, B., & Glasford, D. (2006). Condoms + pleasure = safer sex? A missing addend in the safer sex message . AIDS Care, 18(7), 750–754. 10.1080/09540120500411073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexual Health and Crisis Pregnancy Programme. (2021). Sex and coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.sexualwellbeing.ie/sexual-health/sex-and-coronavirus/

- Singh, A., Both, R., & Philpott, A. (2021). 'I tell them that sex is sweet at the right time' – a qualitative review of 'pleasure gaps and opportunities' in sexuality education programmes in Ghana and Kenya. Global Public Health, 16(5), 788–800. 10.1080/17441692.2020.1809691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A., & Philpott, A. (2019, August). What do we mean by a pleasure-based approach? What does it translate to? Pleasure as a measure of agency and empowerment. Medicus Mundi Schweiz: MMS Bulletin #151. https://thepleasureproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Pleasure-as-a-measure-of-agency-and-empowerment-%E2%80%94-Medicus-Mundi-Schweiz.pdf

- Singh, S., Darroch, J. E., & Ashford, L. S. (2014). Adding it up: The costs and benefits of investing in sexual and reproductive health 2014. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/adding-it-costs-andbenefits-investing-sexual-and-reproductive-health-2014 [Google Scholar]

- Stangl, A. L., Earnshaw, V. A., Logie, C. H., Brakel, W. V., Simbayi, L. C., Barré, I., & Dovidio, J. F. (2019). The health stigma and discrimination framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 31–13. 10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starrs, A. M., Ezeh, A. C., Barker, G., Basu, A., Bertrand, J. T., Blum, R., Coll-Seck, A. M., Grover, A., Laski, L., Roa, M., Sathar, Z. A., Say, L., Serour, G. I., Singh, S., Stenberg, K., Temmerman, M., Biddlecom, A., Popinchalk, A., Summers, C., & Ashford, L. S. (2018). Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: Report of the Guttmacher– Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 391(10140), 2642–2692. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starrs, A., Ezeh, A. C., Barker, G., Basu, A., Bertrand, J. T., Blum, R., Coll-Seck, A. M., Grover, A., Laski, L., Roa, M., Sathar, Z. A., Say, L., Serour, G. I., Singh, S., Stenberg, K., Temmerman, M., Biddlecom, A., Popinchalk, A., Summers, C. S., & Ashford, L. S. (June 2018). Accelerate progress—Sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: Report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. Lancet, 391(10140), 2642–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, W. M., & Pollack, R. H. (1988). The effect of condom use and erotic instructions on attitudes toward condoms. Journal of Sex Research, 25(4), 537–541. 10.1080/00224498809551481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Global Mapping of Pleasure - The Pleasure Project. (2021). Retrieved February 8, 2021, from https://thepleasureproject.org/pleasuremap/

- The Pleasure Project. (2021). Campaigns for advocacy & communication. https://thepleasureproject.org/tpp-event-materials-postcards/

- UN Women. (1995). Beijing and its follow-up. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/

- UNAIDS. 2016. Statement ‘United Nations Political Declaration on Ending AIDS sets world on the Fast-Track to end the epidemic by 2030’. Retrieved February, 2021, from http://teampata.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/UNAIDS_2016-United-Nations-Political-Declaration-on-Ending-AIDS-sets-world-on-the-Fast-Track-to-end-the-epidemic-by-2030.pdf

- UNAIDS. (2021a). 90-90-90: Treatment for all. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/909090

- UNESCO, UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF, UNWOMEN, WHO. (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach (Revised ed.). UNESCO, 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. ( n.d.). UN, department of economic and social affairs, the sustainable development goals . https://sdgs.un.org/

- United Nations. (2014). International conference on population and development programme of action: Twentieth anniversary edition. united nations population fund, 1–296. https://www.unfpa.org/publications/international-conference-population-and-development-programme-action

- Vance, C. (1992). Pleasure and danger: Exploring female sexuality. Pandora Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Clief, L., & Anemaat, E. (2020). Good sex matters: Pleasure as a driver of online sex education for young people. Gates Open Research, 3, 1480. 10.12688/gatesopenres.13003.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vos, T., Lim, S. S., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi, M., Abbasifard, M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abbastabar, H., Abd-Allah, F., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahpour, I., Abolhassani, H., Aboyans, V., Abrams, E. M., Abreu, L. G., Abrigo, M. R. M., Abu-Raddad, L. J., Abushouk, A. I., … Murray, C. J. L.. 2020. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 396(10258), 1204–1222. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watney, S. (1986). Policing desire: Pornography, AIDS and the media first published as policing desire (Media and Society) ISBN 0816630259 (ISBN13: 9780816630257). University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Association for Sexual Health. (n.d). Mexico City World Congress of Sexual Health DECLARATION ON SEXUAL PLEASURE. https://worldsexualhealth.net/wpcontent/uploads/2019/10/2019_WAS_Declaration_on_Sexual_Pleasure.pdf

- Whipple, B., Komisaruk, B. R., & Beyer Flores, C. (2006). The science of orgasm. John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, Geneva. (2019). More than 1 million new curable sexually transmitted infections every day. https://www.who.int/news/item/06-06-2019-more-than-1-million-new-curable-sexually-transmitted-infections-every-day

- World Health Organisation. (2021). World Health Organisation working definition of Sexual health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/sexual-health

- Women, Risk and Aids Project (WRAP, 1989–90). (1989). Interview with Melanie, 21, White British, upper working class. Women, risk and AIDS project, 1989, Manchester. Anonymised version, ref BT08) (pp: 1–13). The Reanimating Data Project (2018–20). https://archives.reanimatingdata.co.uk/s/fays/item/874#?c=&m=&s=&cv=.

- World Association for Sexual Health. (2008). Sexual Health for the Millennium: A declaration and technical document (pp. 133–144). World Association for Sexual Health. https://worldsexualhealth.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/millennium-declaration-english.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Association of Sexual Health. (2019). Definition of sexual pleasure as per the Mexico City Congress of Sexual Health Declaration of Sexual Pleasure . https://worldsexualhealth.net/declaration-on-sexual-pleasure/

- World Association of Sexual Health. (2014). Declaration of sexual rights [Revised]. https://worldsexualhealth.net/resources/declaration-of-sexual-rights/

- World Health Organization. (2006). Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health, 28–31 January 2002, Geneva, Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2016). Promoting health through the life course: What is the Global Strategy? The global strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescent’s Health, 2016. https://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/global-strategy-2016-2030/en/