Abstract

The lack of inclusion of sexual pleasure in comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) could be detrimental to sexual development, misses opportunities for inclusive education, and may have a long-term impact on sexual well-being. The WAS’ Declaration on Sexual Pleasure provides the opportunity to advocate for pleasure as an indispensable part of CSE. Specifically, the inclusion of pleasure in CSE will positively impact six outcomes: traditional risk-reduction, cultivating healthy relationships, celebration of sexual diversity, exercise of sexual rights, empowerment, and consent, and prevention of gender-based sexual violence. Messages of sexual pleasure are crucial for sexuality education to be comprehensive, effective, and inclusive.

Keywords: Sexuality education, comprehensive sex ed, sexual pleasure, inclusion

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is the curriculum-based process that incorporates the teaching of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that empower children and young people to develop a healthy sexuality, healthy relationships, and the recognition and respect of the sexual rights of themselves and others (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2018). CSE is central in addressing the health of of children and young people and it equips them with knowledge, skills, and attitudes they need to determine and enjoy their sexuality – physically and emotionally, individually and in relationships (IPPF, 2016; Kanem, 2017; UNESCO, 2018). It provides the opportunity for youth to acquire skills and strengthen competencies in relation to healthy decision-making around self-esteem and sexual consent, and recognizing qualities for healthy relationships. It works to prevent gender-based violence, unintended pregnancy and STIs/HIV, and aids the understanding of the student’s own sexuality and identity (UNESCO, 2018).

Prevention of adverse sexual health outcomes such as unintended pregnancy, STIs/HIV, and sexual violence are important components of CSE, but focusing only on these issues misses opportunities for promoting youth empowerment, gender equality, and sexual rights. Moreover, targeting only prevention is not sufficient to meet the needs of students at all developmental stages and does not facilitate sexual identity development nor the possibility of building the skills needed for effective communication of sexual needs and the expression of desires. Although many advocates of CSE and educators delivering CSE would ideally like to move beyond prevention to the point of integrating pleasure, they are often limited by lack of funding, inadequate time in the curriculum, inadequate training for the person delivering the CSE, or lack of widespread support to go beyond risk-reduction for fear of backlash (Allen, 2012; Cameron-Lewis & Allen, 2013; Robinson et al., 2017).

So far, the framework that has traditionally been used to determine the efficacy of CSE is reliant on measurable outcomes (e.g., number of unintended pregnancies, age of first sexual intercourse, number of STIs (Kirby, 2007)), but measurable does not equate to effective and may not be comprehensive at all (Morris, 2005). Additionally, this reliance on measureable outcomes related to risk-reduction are short-term and do not measure important developmental skills such as self-efficacy, agency, and confidence communicating things like consent; all crucial to CSE efforts (Kantor & Lindberg, 2020; Morris, 2005).

The pursuit of sexual pleasure is inarguably a central motivation for engaging in sexual activity (Edwards & Coleman, 2004; Hull, 2008; Meston & Buss, 2007; World Association for Sexual Health (WAS), 2008); therefore, a pleasure-based approach must be included in CSE curricula to normalize the idea that giving and receiving pleasure, not only in sexual intercourse but in relationships, is completely normal and contributes to increased life satisfaction and wellbeing. The content currently covered in CSE needs to expand beyond sexual risk reduction, beyond communication and self-efficacy, and focus on holistic sexual health, inclusive of sexual pleasure (Fortenberry, 2013; Kantor & Lindberg, 2020).

The WAS’ Declaration on Sexual Pleasure defines sexual pleasure as the enjoyment and satisfaction derived from any kind of sexual activity or erotic experience, solitary or partnered (WAS, 2019). This Declaration also provides a powerful and unique platform from which sexuality educators and policymakers can advocate to integrate sexual pleasure in their curricula as it is central to sexual rights and sexual health (Ford et al., 2019). However, the reality is that sexual pleasure is currently insufficiently integrated into sexuality education efforts worldwide (Allen & Carmody, 2012; Fine & McClelland, 2006) and one of the reasons has to do with the explicit denial of people’s sexual expression and sexuality, especially for young people, which entails the denial of their sexual rights. By incorporating a pleasure-based approach to sexuality education, students develop healthier relationships both with themselves and their partners by learning to identify their own sexual needs, preferences, boundaries, and desires. It may equip them to make informed decisions and may contribute to their capacity to say “no” to sex when it does not feel right and, most importantly, to say “yes” to sex when it does. Pleasure is inherently about feeling happy and fulfilled.

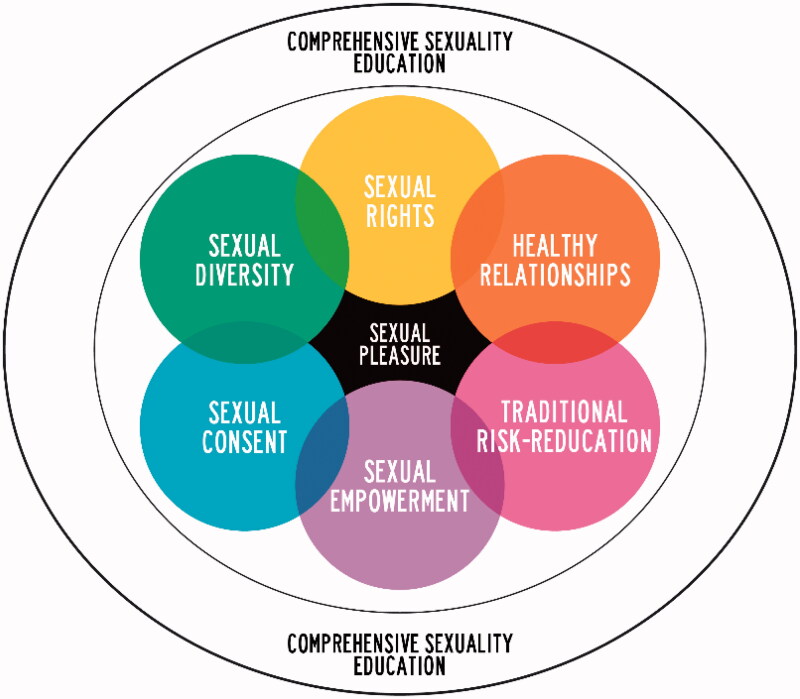

There is a worldwide need for comprehensive and accessible sexuality education inclusive of sexual pleasure that empowers individuals to exercise their sexual rights and to live sexually healthy and satisfying lives. This contributes not only to the acknowledgment and exercise of sexual rights, but also provides accurate information to recognize and filter unhealthy messages about sexual pleasure coming from different sources such as adverstisments, TV, and peers, that are constantly providing information on sexuality. This paper aims to identify the ways in which sexuality educators and policymakers can apply the WAS’ Declaration on Sexual Pleasure (2019) to advocate for the inclusion of sexual pleasure in CSE curricula in formal and informal settings. Based on the extant literature and empirical evidence, we propose six outcomes of sexuality education (see Figure 1) that could potentially be improved by the inclusion of sexual pleasure.

Figure 1.

The six outcomes of sexuality education benefit from the integration of sexual pleasure to CSE.

Traditional risk-reduction

A sexually unhealthy society comes at great social and economic cost (Chesson et al., 2017; Phipps, 2008; Trussell, 2007). A sexually healthy society is one with low unintended pregnancy rates, low STI and HIV rates, where gender equality policies result in the establishment of legal protocols to eliminate gender-based sexual violence, and where pleasure, particularly sexual pleasure, contributes to happy and healthy sex lives. Worldwide, as access to contraceptives has increased, the rate of unintended pregnancy has fallen; however, progress is not uniform. Women in the poorest countries are still more likely to face unintended pregnancies than those in the wealthiest countries; in developing regions, an estimated 21 million girls aged 15–19 years become pregnant every year, and approximately 12 million of them give birth (Maddow-Zimet et al., 2020). Estimates also suggest that 2.5 million girls aged under 16 years give birth every year (Maddow-Zimet et al., 2020). In addition, adolescents and young people represent a growing share of people living with HIV worldwide. In 2019 alone, 460,000 young people between the ages of 10–24 were newly infected with HIV, of whom 170,000 were adolescents between the ages of 10 and 19 (United Nations AIDS (UNAIDS)). Likewise, STIs have become a major concern as more than one million infections are acquired every day worldwide among people aged 15–49 (World Health Organization (WHO), 2019). More recently, within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, violence against women and girls has increased significantly. Globally, 34% of women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence, and 137 women are killed by a member of their family every day (United Nations Women (UNWOMEN), 2020).

Given the pervasiveness of negative sexual health outcomes in various regional contexts, CSE can have a positive impact in people’s lives, especially when it aims to provide young people with the necessary skills to make free, informed, and responsible decisions for their wellbeing. Efforts worldwide need to be improved to meet a holistic approach to sexuality education, which includes contents about reproduction, sexual behaviors, risks and prevention of ill health, but most importantly, which incorporates content that provides opportunities to help people understand that sexuality is positive and might include feelings of love, pleasure, or relationships based on mutual respect and equality (UNESCO, 2018). Although the potential benefits of integrating positive sexual content into general persuasive messaging has been well-studied and sex has long been used to market non-sexual products with great efficacy (see review by Reichert (2002)), this approach has been notably absent from CSE implementation and, especially, evaluation. In fact, sex and sexual pleasure have been historically absent from sexual health messaging that targets women in particular (Higgins & Hirsch, 2008; Higgins et al., 2008). Yet, eroticizing safer sex leads to more risk-preventive attitudes and less risky sexual behavior (Scott-Sheldon & Johnson, 2006) and practicing safer sex can actually make sex more pleasurable (Philpott et al., 2006).

Traditional risk-reduction efforts that target unintended pregnancy, STI/HIV prevention, and the elimination of sexual violence would be more effective with the integration of strategies and messages relevant to young people’s wellbeing such as self-esteem and pleasure-seeking from the early stages of a CSE process. Researchers argue that most current sexuality education efforts focus too much on fear-based messaging and not enough on pleasure-based messaging despite its potential for efficacy (Beasley, 2008; Kantor & Lindberg, 2020; Philpott et al., 2006). Effective sexuality education must be free of guilt, shame, and secrecy. Additionally, even if some programs that integrate sexual pleasure include outcome evaluations, the direct impact of the integration of sexual pleasure into messaging has not yet been empirically measured or evaluated. Therefore, empirical documentation and evaluation of the integration of sexual pleasure into CSE is a necessary next step (Kantor & Lindberg, 2020).

Although there are many reasons that sexuality education may not be as effective as it could be – unsuitable educational approaches, content focused only on prevention, lack of adequate planning and implementation, lack of teacher training, lack of political support and financial backing, ineffectiveness to respond to young people’s needs and demands, or to the young people’s diversity – the lack of inclusion of sexual pleasure when it is one of the strongest motivators of sex is certainly worth further empirical examination. The WAS Declaration on Sexual Pleasure provides a strong framework for educators and advocates of sexuality education to avoid focusing exclusively on traditional risk reduction health outcomes and to integrate rights-based and gender-equality approaches as a fundamental part of sexuality education which could lead to the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences (WAS, 2019). The aim of this paper is to outline six outcomes of CSE that benefit from the inclusion of sexual pleasure (see Figure 1) and provide empirical evidence and calls to future research that bolster the inclusion of sexual pleasure in CSE efforts in practice.

Healthy relationships

Incorporating messages of sexual pleasure, sexual communication, and healthy satisfying sexual expression into sexuality education has the potential to improve the extent to which youth can confidently navigate their early sexual experiences and relationships. Research has shown that adolescence is a time where there is a heightened vulnerability to losing touch with one’s own identity as a sexual person, especially for girls, and especially when it comes to sexual expression and relationships (Impett et al., 2006; Tolman, 1994; Tolman, 2012; Tolman et al., 2003), which may negatively impact the way they relate with others. Unfortunately, there has been little empirical work to focus specifically on the impact that positive messages about the pursuit of sexual pleasure within CSE can have on the development of healthy relationships for youth and adolescents.

Positive relationships and sexual experiences in adolescence contribute to developing healthy intimate relationships throughout the lifespan (Impett & Tolman, 2006; O’Sullivan et al., 2019). Sexual satisfaction in adults is associated with better physical and psychological well-being (Davison et al., 2009; Dundon & Rellini, 2010), better communication between couples (Dundon & Rellini, 2010; Henderson et al., 2009; Mark & Jozkowski, 2013), and stronger relationship satisfaction (Vowels & Mark, 2020). Satisfying intimate relationships are one of the strongest predictors of happiness and life satisfaction (Diener & Seligman, 2002) and maintaining that satisfaction over time can be accomplished through the maintenance of sexual desire, sexual satisfaction, communication, and mutual respect (Butzer & Campbell, 2008; Impett et al., 2008; McNulty et al., 2016).

Building these sexual and relationship skills early and throughout life provides a foundation from which to foster intimacy through the pursuit of sexual pleasure and shared sexual experience. If risk reduction is the only focus of sexuality education and young people are withheld information about why individuals choose to engage in sexual behavior (including but not limited to masturbation, sexual touching, oral sex, vaginal sex, anal sex) for the sake of their well-being, they will fail to benefit from crucial information about intimacy building, sexual exploration beyond penile-vaginal intercourse, and opportunities for diverse sexual experiences, all of which contribute to sexual satisfaction (Giuliano & Allard, 2001; O’Leary et al., 2012; Štulhofer et al., 2014; Yoo et al., 2014). The WAS Declaration on Sexual Pleasure affirms that access to sources of sexual pleasure are part of human experience and subjective well-being (WAS, 2019) and including sexual pleasure in sexuality education can expand learners’ ability to communicate and cultivate intimacy in relationships, thereby improving their overall well-being.

Sexual diversity

Sexuality education has the potential to be more effective worldwide with the incorporation of sexual pleasure into our broad understanding of sexual health including the possibility of diverse sexual experiences (WAS, 2019). This encourages CSE to go beyond cisgender heteronormative ideas of penile-vaginal intercourse as the “gold standard” of sex. By focusing on sexual pleasure, we distance from the intercourse framework so messages become inclusive to all sexual diversities and gender identities; social messages based on guilt and shame can be broken down around constructs such as “virginity” that negatively impact everyone (Bhana, 2016), especially young girls and women. Clearly specifying sexual pleasure as an inherent desire or aspiration that contributes to our sexuality and is an integral part of who we are. It helps us lead our efforts toward achieving sexual health rather than focusing on guilt, shame, and secrecy, or messages of “purity and modesty” (that are often disproportionately targeted toward young girls); this can facilitate sexual empowerment and the recognition of different sexual experiences (Orenstein, 2016). The WAS Declaration on Sexual Pleasure indicates sexual pleasure is part of human experience fundamental to well-being, sexual, and human rights (WAS, 2019) and this is no truer than in the context of diverse sexual and gender development.

Sexual expression and the development of one’s sexuality is understood as a core dimension of being human and includes the understanding of, and relationship to, the human body; emotional attachment and love; sex; gender expression; gender identity; sexual orientation; sexual intimacy; pleasure; and reproduction (UNESCO, 2018). Freedom to develop one’s sexuality is a sexual right and thus, a Human Right. By providing sexuality education in a setting where diversity and inclusion are taught to all learners (e.g., people with disabilities, transgender and gender diverse people, people from all cultural backgrounds), allows all identities to feel included and understood, and opens the possibility of experiencing better sexual health outcomes (Human Rights Campaign, 2015; Jarpe-Ratner, 2020; Proulx et al., 2019; Snapp et al., 2015).

Sexual rights

Sexual rights are solidly grounded in universal human rights for the attainment of sexual health and sexual pleasure. Sexual rights apply existing human rights to sexuality and sexual health. People have a right to fulfill, express, and enjoy their sexuality and sexual health within the bounds of respecting others’ sexual rights (WHO, 2006). The WAS (2019) states that the highest attainable standard of sexual health involves the possibility of pleasurable, satisfying, and safe sexual experiences. By integrating sexual pleasure into CSE, there is a foundation of understanding that sexuality, and pleasure derived from it, is a central aspect of being human and retains one’s sexual rights. Humans have a right to experience and enjoy sexuality independent of reproduction, and reproduction independent of sexuality should be safeguarded (IPPF, 2008).

There are several ways in which CSE can focus on sexual rights as an outcome of educational efforts. By integrating more pleasure-based messages in CSE, there is greater opportunity for sexual rights to be acknowledged and respected. This protects the rights to sexual freedom; to sexual autonomy integrity and safety of the sexual body; to sexual privacy; to sexual equality; to emotional sexual expression; to sexually associate freely; to make free and responsible reproductive choices; to sexual information based upon scientific inquiry; and to sexual health care (WAS, 2019). There are adverse health impacts when human rights are violated, and there has been an increase in the recognition of the importance of sexual rights as human rights—look to LGBTQ+ rights, disability rights, or sex workers’ rights as examples (Kismödi et al., 2017). Any opportunity to strengthen the link between sexual health, sexual rights, and sexual pleasure has the potential to bolster the efficacy of CSE efforts; integrating sexual pleasure into CSE provides that opportunity. The WAS Declaration of Sexual Rights (Kismödi et al., 2017) states that everyone has the right to education and the right to CSE. This declaration indicates that CSE must provide positive approaches to sexuality and pleasure in addition to it being age appropriate, scientifically accurate, culturally competent, and grounded in human rights and gender equality. Educators and policymakers who plan or implement CSE should use the WAS Declaration that sexual pleasure contributes to sexual health and sexual rights, and that it is a human right as a persuasive argument for messages of sexual pleasure to be included in CSE efforts.

Sexual empowerment

An important outcome of CSE is the ability to equip young people with information that empowers them to make decisions around their sexuality and sexual health that are beneficial for them. Although the definition of sexual empowerment is disputed—some argue it is an internal subjective feeling of agency and power, others argue it is an objective measure of power and control—it is agreed to be multidimensional and continuous (Peterson, 2010). When young people are provided space to develop their own ways of sexual knowledge building within CSE, sexual empowerment can be an effective and powerful CSE outcome (Kohler et al., 2008; Naezer et al., 2017). This empowerment is crucial to healthy sexual development; however, this is something that is particularly difficult to teach young women in many cultural contexts around the world that operate within strict patriarchical norms (Tolman et al., 2003). Providing the educational message that the pursuit of sexual pleasure is something that contributes positively to sexual health and well-being may have a powerful impact on empowerment of learners and the WAS Declaration of Sexual Pleasure can be an influential force in advocating for this.

Research has shown that CSE with a focus on aspects of sexual empowerment have been successful at addressing traditional sexual health outcomes such as contraceptive use (Crissman et al., 2012). Additionally, CSE focusing on gender inequalities that may be a barrier to sexual empowerment, such as improving attitudes toward girls and women, facilitating less agreement with hegemonic masculinity ideology, and increasing baseline sexual health knowledge are promising (Grose et al., 2014). Additionally, scholars have argued that at the core of young women reaching sexual empowerment there is a need to address the sexualization of girls and women due to issues of gender inequality (Fine & McClelland, 2006; Tolman, 2012). To address this, it will require work with youth of all gender identities to create a more inclusive and complete picture of what healthy sexuality looks like – complete with sexual pleasure.

Sexual consent and the prevention of gender-based sexual violence

The WAS Declaration on Sexual Pleasure states that safe sexual experiences free of discrimination, coercion, and violence are a fundamental part of sexual health (WAS, 2019). As noted above, integrating sexual pleasure into sexuality education can correct some of the deeply engrained shame-based messages that are part of abstinence-only sex education (Kantor, 1993); these messages directly contribute to gender-based violence around the world (Gruber et al., 2014; Hlavka, 2017). CSE can have a positive impact on attitudes and values around gender norms and promote messages of gender equality (Rollston et al., 2020). In an evaluation of CSE programmes focusing on gender and empowerment, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (2015) found that compared to boys in a control group, boys participating in comprehensive sexuality education programmes recognized gender inequity and said they were making changes in their behavior and encouraging others to do the same more frequently than boys in the control group. Additionally, girls who participated in CSE programmes reported that their brothers and other boys in their communities were also more likely to make changes for gender equality than girls in the control group (UNFPA, 2015). A recent qualitative study examining the role of CSE to prevent intimate partner violence among young people has provided support that CSE is effective in developing strategies to prevent and respond to partner violence. Among the elements that seemed central to violence prevention were: (1) their reflection about romantic relationships, which helped them question whether jealousy and possessive behaviors were signs of love; (2) helping them develop skills to communicate about sexuality, inequitable relationships, and reproductive health; (3) encouraging care-seeking behavior; and (4) addressing norms around gender and sexuality, for example demystifying and decreasing discrimination toward sexually diverse populations (Schneider & Hirsch, 2020).

Gender-based sexual violence is rooted in inequality. A crucial component of sexual pleasure involves the feeling of sexual safety and sexual trust (Fortenberry, 2019 May-Jun). In a study of women who had experienced sexual trauma, the need to develop skills of self-efficacy and agency in advocating for their own sexual pleasure was consistent across women’s work to move into a healthy sexual relationship post-sexual trauma (Mark & Vowels, 2020). Many women in this study did not feel as though they deserved to experience sexual pleasure, but if we taught messages of sexual pleasure along with self-esteem, healthy relationships, personal well-being and sexual rights, as part of our approach to sexuality education, the pursuit of pleasure could be considered standard for learners.

Conclusion

Taken together, integrating sexual pleasure in CSE efforts aligns with the WAS Declaration on Sexual Pleasure in several important ways. Utilizing the integration of sexual pleasure to CSE efforts can benefit several outcomes of CSE that are crucial for healthy sexual development, empowerment, and well-being (Figure 1). The implications of improving outcomes of CSE by integrating sexual pleasure should not be missed by policymakers, educators, administrators, and parents looking to advance the sexual health of their communities. Education is ongoing, lifelong, defined by the cultural norms of communities and regions, and therefore messages of sexual pleasure should be culturally competent, just as is suggested with other parts of sexuality education curricula.

Effective sexuality education is intended to provide the opportunity for individuals to develop a deeper understanding of their own sexuality, the self-efficacy to act confidently on that knowledge, the skills necessary to enhance sexual health and avoid negative sexual health outcomes, and an environment that is safe, secure, and inclusive for achieving optimal sexual health (SIECCAN, 2020). There have been strong calls for an expansion of content and a more comprehensive evaluation of efficacy of CSE programs (e.g., Kantor & Lindberg, 2020), and the WAS Declaration of Sexual Pleasure bolsters this message and provides additional evidence for the importance of actual implementation of messages of sexual pleasure in CSE.

Sexuality education, when effectively developed and delivered, provides a host of health benefits including delayed initiation of sex, reduction in sexual risk-taking, increased condom and contraception use, increased knowledge about sexuality and safer sex behaviors, and more positive attitudes toward sexual health (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2015; Fonner et al., 2014; UNESCO, 2018). Sexual pleasure is a crucial component of sexual health and the programmatic inclusion of sexual pleasure in sexuality education efforts is required to truly meet individuals’ needs, aspirations, and realities for optimal sexual health through the lifespan. The creation of guidelines for sexuality education that are culturally competent, inclusive, and that position pleasure as central to sexual health has the potential to be effective in forming a sexually empowered youth equipped to make healthy decisions around their sexual life. Messages of sexual pleasure throughout sexual development will contribute positively to sexual relationships, help to battle against messages of shame and guilt around sex that are prominent in many cultures, and support sexual empowerment and sexual rights inclusive of all people.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Allen, L. (2012). Pleasure’s perils? Critically reflecting on pleasure’s inclusion in sexuality education. Sexualities, 15(3–4), 455–471. 10.1177/1363460712439654 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L., & Carmody, M. (2012). ‘Pleasure has no passport’: Re-visiting the potential of pleasure in sexuality education. Sex Education, 12(4), 455–468. 10.1080/14681811.2012.677208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley, C. (2008). The challenge of pleasure: Re-imagining sexuality and sexual health. Health Sociology Review, 17(2), 151–163. 10.5172/hesr.451.17.2.151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhana, D. (2016). Virginity and virtue: African masculinities and femininities in the making of teenage sexual cultures. Sexualities, 19(4), 465–481. 10.1177/1363460715613298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15(1), 141–154. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00189.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron-Lewis, V., & Allen, L. (2013). Teaching pleasure and danger in sexuality education. Sex Education, 13(2), 121–132. 10.1080/14681811.2012.697440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra-Mouli, V., Lane, C., & Wong, S. (2015). What does not work in adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A review of evidence on interventions commonly accepted as best practices. Global Health: Science and Practice, 3(3), 333–340. 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson, H. W., Mayaud, P., & Aral, S. O. (2017). Sexually transmitted infections: Impact and cost-effectiveness of prevention. In Holmes K. K., Bertozzi S., and Bloom B. R. (Eds.), Major infectious diseases (3rd ed.). The World Bank. 10.1596/978-1-4648-0524-0_ch10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crissman, H. P., Adanu, R. M., & Harlow, S. D. (2012). Women’s sexual empowerment and contraceptive use in Ghana. Studies in Family Planning, 43(3), 201–212. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00318.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison, S. L., Bell, R. J., LaChina, M., Holden, S. M., & Davis, S. R. (2009). The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(10), 2690–2697. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84. 10.1111/1467-9280.00415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundon, C. M., & Rellini, A. H. (2010). More than sexual function: Predictors of sexual satisfaction in a sample of women age 40–70. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(2 Pt 2), 896–904. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01557.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, W. M., & Coleman, E. (2004). Defining sexual health: A descriptive overview. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(3), 189–195. 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000026619.95734.d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, M., & McClelland, S. (2006). Sexuality education and desire: Still missing after all these years. Harvard Educational Review, 76(3), 297–338. 10.17763/haer.76.3.w5042g23122n6703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fonner, V. A., Armstrong, K. S., Kennedy, C. E., O’Reilly, K. R., & Sweat, M. D. (2014). School based sex education and HIV prevention in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 9(3), e89692. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J., Vargas, E. C., Finotelli, I., Jr., Fortenberry, J. D., Kismödi, E., Philpott, A., Rubio-Aurioles, E., & Coleman, E. (2019). Why pleasure matters: Its global relevance for sexual health, sexual rights and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 217–230. 10.1080/19317611.2019.1654587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry, J. (2019, May-Jun). Trust, sexual trust, and sexual health: An interrogative review. Journal of Sex Research, 56(4–5), 425–439. 10.1080/00224499.2018.1523999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry, J. D. (2013). The evolving sexual health paradigm: transforming definitions into sexual health practices. AIDS (London, England), 27(Suppl 1), S127–S133. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano, F., & Allard, J. (2001). Dopamine and sexual function. International Journal of Impotence Research, 13(S3), S18–S28. 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose, R. G., Grabe, S., & Kohfeldt, D. (2014). Sexual education, gender ideology, and youth sexual empowerment. Journal of Sex Research, 51(7), 742–753. 10.1080/00224499.2013.809511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, D., Hansen, L., Soaper, K., & Kivisto, A. J. (2014). The role of shame in general, intimate, and sexual violence perpetration. In Lockhart K.G. (Ed.), Psychology of shame: New research (pp. 39–62). Nova Science. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, A. W., Lehavot, K., & Simoni, J. M. (2009). Ecological models of sexual satisfaction among lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(1), 50–65. 10.1007/s10508-008-9384-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. A., & Hirsch, J. S. (2008). Pleasure, power, and inequality: Incorporating sexuality into research on contraceptive use. American Journal of Public Health, 98(10), 1803–1813. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. A., Hoffman, S., Graham, C., & Sanders, S. A. (2008). Relationships between condoms, hormonal methods, and sexual pleasure and satisfaction: An exploratory analysis from the Women’s Well-Being and Sexuality Study. Sexual Health, 5(4), 321–330. 10.1071/SH08021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavka, H. R. (2017). Speaking of stigma and the silence of shame: Young men and sexual victimization. Men and Masculinities, 20(4), 482–505. 10.1177/1097184X16652656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hull, T. H. (2008). Sexual pleasure and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health, 20(1–2), 133–145. 10.1080/19317610802157234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign (2015). A call to action: LGBTQ youth need inclusive sex education. https://hrc-prod-requests.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/files/assets/resources/HRC-SexHealthBrief-2015.pdf?mtime=20200713133955&focal=none

- Impett, E. A., Schooler, D., & Tolman, D. L. (2006). To be seen and not heard: Femininity ideology and adolescent girls’ sexual health. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(2), 129–142. 10.1007/s10508-005-9016-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impett, E. A., Strachman, A., Finkel, E. J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Maintaining sexual desire in intimate relationships: The importance of approach goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(5), 808–823. 10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impett, E. A., & Tolman, D. L. (2006). Late adolescent girls’ sexual experiences and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Adolescent Research, 21(6), 628–646. 10.1177/0743558406293964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPPF (2008). Sexual rights: An IPPF declaration. https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/sexualrightsippfdeclaration_1.pdf

- IPPF (2016). Everyone’s right to know: Delivering comprehensive sexuality education for all young people. https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/2016-05/ippf_cse_report_eng_web.pdf

- Jarpe-Ratner, E. (2020). How can we make LGBTQ+-inclusive sex education programmes truly inclusive? A case study of Chicago Public Schools’ policy and curriculum. Sex Education, 20(3), 283–299. 10.1080/14681811.2019.1650335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanem, N. (2017, December). Advancing comprehensive sexuality education to achieve the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://www.unfpa.org/press/advancing-comprehensive-sexuality-education-achieve-2030-agenda-sustainable-development

- Kantor, L. M. (1993). Scared chaste? Fear-based educational curricula. SIECUS Report, 21(2), 1–15. PMID: 12344738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor, L. M., & Lindberg, L. (2020). Pleasure and sex education: The need for broadening both content and measurement. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), 145–148. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, D. (2007). Abstinence, sex, and STD/HIV education programs for teens: Their impact on sexual behavior, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted disease. Annual Review of Sex Research, 18(1), 143–177. 10.1080/10532528.2007.10559850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kismödi, E., Corona, E., Maticka-Tyndale, E., Rubio-Aurioles, E., & Coleman, E. (2017). Sexual rights as human rights: A guide for the WAS Declaration of Sexual Rights. International Journal of Sexual Health, 29(sup1), 1–92. 10.1080/19317611.2017.1353865 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, P. K., Manhart, L. E., & Lafferty, W. E. (2008). Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 42(4), 344–351. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddow-Zimet, I., Kost, K., & Finn, S. (2020). Pregnancies, births and abortions in the United States, 1973–2016: National and state trends by age. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/pregnancies-births-abortions-in-united-states-1973-2016

- Mark, K. P., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2013). The mediating role of sexual and nonsexual communication between relationship and sexual satisfaction in a sample of college-age heterosexual couples. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(5), 410–427. 10.1080/0092623X.2011.644652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark, K. P., & Vowels, L. (2020). Sexual consent and sexual agency of women in healthy relationships following a history of sexual trauma. Psychology & Sexuality, 11(4), 315–328. 10.1080/19419899.2020.1769157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty, J. K., Wenner, C. A., & Fisher, T. D. (2016). Longitudinal associations among relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and frequency of sex in early marriage. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 85–97. 10.1007/s10508-014-0444-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston, C. M., & Buss, D. M. (2007). Why humans have sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(4), 477–507. 10.1007/s10508-007-9175-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R. W. (2005). Research and evaluation in sexuality education: An allegorical exploration of complexities and possibilities. Sex Education, 5(4), 405–422. 10.1080/14681810500278501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naezer, M., Rommes, E., & Jansen, W. (2017). Empowerment through sex education? Rethinking paradoxical policies. Sex Education, 17(6), 712–728. 10.1080/14681811.2017.1362633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, K. D., Acevedo, B. P., Aron, A., Huddy, L., & Mashek, D. (2012). Is long-term love more than a rare phenomenon? If so, what are its correlates? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(2), 241–249. 10.1177/1948550611417015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein, P. (2016). Girls and sex: Navigating the complicated new landscape. Harper-Collins. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, L., Hughes, K., Talbot, F., & Fuller, R. (2019). Plenty of fish in the ocean: How do traits reflecting resiliency moderate adjustment after experiencing a romantic breakup in emerging adulthood? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(5), 949–962. 10.1007/s10964-019-00985-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Z. D. (2010). What is sexual empowerment? A multidimensional and process-oriented approach to adolescent girls’ sexual empowerment. Sex Roles, 62(5–6), 307–313. 10.1007/s11199-009-9725-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott, A., Knerr, W., & Boydell, V. (2006). Pleasure and prevention: When good sex is safer sex. Reproductive Health Matters, 14(28), 23–31. 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28254-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott, A., Knerr, W., & Maher, D. (2006). Promoting protection and pleasure: Amplifying the effectiveness of barriers against sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy. Lancet (London, England), 368(9551), 2028–2031. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69810-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps, M. G. (2008). Consequences of inadequate sex education in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 111(2 Pt 1), 254–255. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318163c833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, C. N., Coulter, R. W. S., Egan, J. E., Matthews, D. D., & Mair, C. (2019). Associations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning-inclusive sex education with mental health outcomes and school-based victimization in U.S. high school students. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 64(5), 608–614. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert, T. (2002). Sex in advertising research: A review of content, effects, and functions of sexual information in consumer advertising. Annual Review of Sex Research, 13(1), 241–273. 10.1080/10532528.2002.10559806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, K. H., Smith, E., & Davies, C. (2017). Responsibilities, tensions, and ways forward: Parents’ perspectives on children’s sexuality education. Sex Education, 17(3), 333–347. 10.1080/14681811.2017.1301904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rollston, R., Wilkinson, E., Abouelazm, R., Mladenov, P., Horanieh, N., & Jabbarpour, Y. (2020). Comprehensive sexuality education to address gender-based violence. Lancet (London, England), 396(10245), 148–150. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31477-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M., & Hirsch, J. S. (2020). Comprehensive sexuality education as a primary prevention strategy for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 21(3), 439–455. 10.1177/1524838018772855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon, L. A., & Johnson, B. T. (2006). Eroticizing creates safer sex: A research synthesis. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 27(6), 619–640. 10.1007/s10935-006-0059-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIECCAN (2020). Questions & answers: Sexual health education in schools and other settings. Sex Information & Education Council of Canada (SIECCAN; ). [Google Scholar]

- Snapp, S. D., Burdge, H., Licona, A. C., Moody, R. L., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Students’ perspectives on LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education, 48(2), 249–265. 10.1080/10665684.2015.1025614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Štulhofer, A., Ferreira, L. C., & Landripet, I. (2014). Emotional intimacy, sexual desire, and sexual satisfaction among partnered heterosexual men. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29(2), 229–244. 10.1080/14681994.2013.870335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman, D. L. (1994). Daring to desire: Culture and the bodies of adolescent girls. In Irvine J. (Ed.), Sexual cultures: Adolescents, communities and the construction of identity (pp. 250–284). Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman, D. L. (2012). Female adolescents, sexual empowerment and desire: A missing discourse of gender inequity. Sex Roles, 66(11–12), 746–757. 10.1007/s11199-012-0122-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman, D. L., Striepe, M. I., & Harmon, T. (2003). Gender matters: Constructing a model of adolescent sexual health. Journal of Sex Research, 40(1), 4–12. 10.1080/00224490309552162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trussell, J. (2007). The cost of unintended pregnancy in the United States. Contraception, 75(3), 168–170. 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education. An evidence-informed approach (Rev. ed.). UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (2015). The evaluation of comprehensive sexuality education programmes: A focus on the gender and empowerment outcomes. UNFPA. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Women (UNWOMEN) (2020). Facts and figures: Ending violence against women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures

- Vowels, L. M., & Mark, K. P. (2020). Relationship and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal Actor-Partner Interdependence Model approach. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 35(1), 46–59. 10.1080/14681994.2018.1441991 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Association for Sexual Health (WAS) (2008). Sexual health for the millennium. A declaration and technical document. World Association for Sexual Health. https://worldsexualhealth.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/millennium-declaration-english.pdf

- World Association for Sexual Health (WAS) (2019). WAS declaration on sexual pleasure. World Association for Sexual Health. https://worldsexualhealth.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019_WAS_Declaration_on_Sexual_Pleasure.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO ). (2006). Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health 28–31 January 2002, Geneva. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/gender_rights/defining_sexual_health.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization (WHO ). (2019). Sexually transmitted infection factsheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis)

- Yoo, H., Bartle-Haring, S., Day, R. D., & Gangamma, R. (2014). Couple communication, emotional and sexual intimacy, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40(4), 275–293. 10.1080/0092623X.2012.751072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]