Abstract

Background:

Trauma is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide. There is a need for development and provision of efficient paediatric trauma services based on adequate information and funding which are lacking in low- and middle-income countries.

Aims:

This study was carried out to assess the scale of the problem, identify the most common causes of trauma in Pan African Paediatric Surgical Association (PAPSA) zone and to define the limiting factors for provision of the necessary services required to reduce the potential mortality and disability.

Materials and Methods:

Data were collected through an electronic form sent out in PAPSA platform. Members were requested to provide prospective data on all paediatric major trauma admitted to or seen at their health facilities between the beginning of April 2019 and the end of June 2020. Hospital location, child’s age, gender, type of injury, mechanism of injury, severity, initial management, method of transport, time to arrive to hospital, availability of surgical specialities, length of hospital stay and injury outcome were analysed.

Results:

There were 531 entries. The mean age was 3.53 years and median age 1.34 years. Male-to-female ratio was 2:1. The leading causes for injuries were falls 194 (36.53%) and motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) 176 (33.15%) followed by obstetrical 42 (7.9%), thermal 27 (5.1%) and domestic injuries 22 (4.1%). The most common injuries were limb fractures 181 (34.1%) and traumatic brain injury 111 (20.9%). Public and private transport were used in 313 (58.9%), while ambulance service was used in only 54 (10.1%). Distances to a health facility varied between 1 and 157 km. 70.2% of cases did not receive any primary care, while definitive care was received in 95.5% of the cases. Outcome was full recovery in 90.6% of patients, morbidity in 8.1% and a mortality rate of 1.3%.

Conclusions:

Most of the injuries were in the under 5-year age group. The two main causes of trauma in children in this study were the falls from height and MVCs. Long distance travels to reach health-care facilities were noticeable in this study, together with substantial lack of adequate ambulance facilities and shortage in necessary subspecialty services such as neurosurgical, orthopaedics and rehabilitation. Implementing proposed recommendations can reduce the burden.

Keywords: Africa, children, paediatric trauma

INTRODUCTION

Trauma remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children across the world. It is estimated that 40% of all deaths and 30% of disability in children aged 1–14 years are due to trauma.[1,2] Moreover, an alarming 95% of trauma-related deaths are in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) including Africa.[3] The rate of unintentional injuries for children in sub-Saharan Africa has reached 53.1 per 100,000, the highest for regions across all income levels.[4] There is a need for development and provision of proper and efficient paediatric trauma services based on adequate information and funding which is frequently an obstacle in LMICs.

With this background, and following a panel discussion on Paediatric Trauma in Africa at the 12th Pan African Paediatric Surgical Association (PAPSA) meeting in Addis Ababa, November 2018, a consensus was reached on the need for a trauma registry establishment to obtain a uniform database. This preliminary study was carried out aiming to assess the current scale of the problem, identify the most common causes of trauma in PAPSA zone and to define the limiting factors for provision of the necessary services required to reduce the potential mortality and disability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An electronic pro forma was designed and sent out through PAPSA communication platform to all its registered membership with a request to provide prospective data on all paediatric major trauma admitted to or seen at their health facilities between the beginning of April 2019 and the end of June 2020. A centre outside of Africa participated and this was planned to allow for some comparison. Data requested included: hospital location, city, country, child’s age, gender, type of injury, mechanism of injury, severity, initial management received, method of transport, time to arrive to hospital, availability of surgical specialities, length of hospital stay (LOHS) and injury outcome – either mortality, disability or recovery.

RESULTS

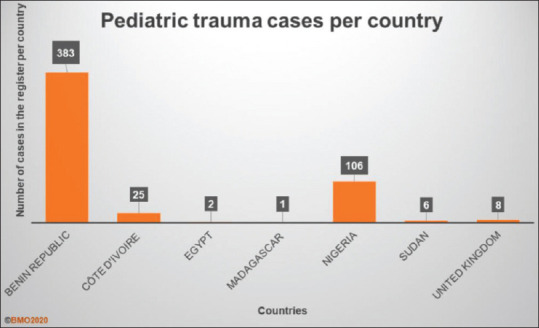

There were 531 entries from 6 countries in the African continent and contribution from one centre in UK for comparison. Response was variable ranging from 1 entry (in Madagascar) to 383 in (Benin). The entries from Benin and Nigeria represented >92% [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Most of the cases were reported from Benin republic and Nigeria

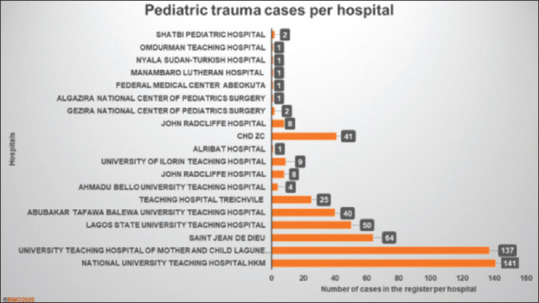

Participating hospitals are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Participating hospitals

Ages of injured children ranged between 1 day and 18 years with a mean age 3.53 years and median age 1.34 years.

Males were more frequently injured than females 330 versus 201 (62 vs. 38%), a ratio of approximately 2:1.

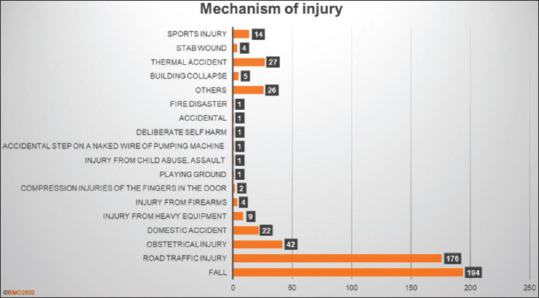

The leading causes for injuries were falls 194 (36.53%) and motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) 176 (33.15%), followed by obstetrical 42 (7.9%), thermal 27 (5.1%) and domestic injuries 22 (4.1%), and others 70 (13.22%). Firearm injuries were reported in 4 cases, all of whom were from a UK centre [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Falls and motor vehicle accident represented the most common causes of paediatric trauma

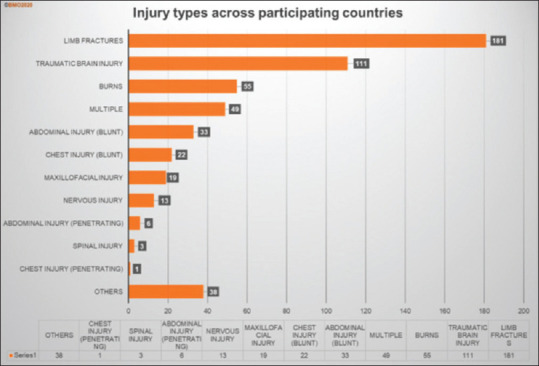

The most common inflicted injuries were limb fractures 181 (34.1%), followed by traumatic brain injury (TBI) 111 (20.9%), burns 55 (10.4%), multiple injuries 49 (9.2%), abdominal injuries 33 (6.2%), chest injuries 22 (4.1%) and others 80 (15%) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Limb fracture was the most common type of inflicted injury, followed by traumatic brain injury, burns and multiple injuries and blunt abdominal injuries

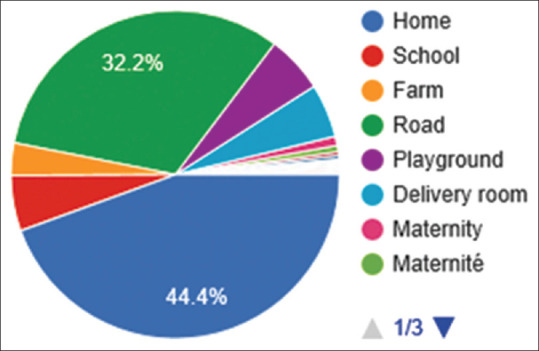

Majority of injuries took place at home followed by roads [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Place of injury

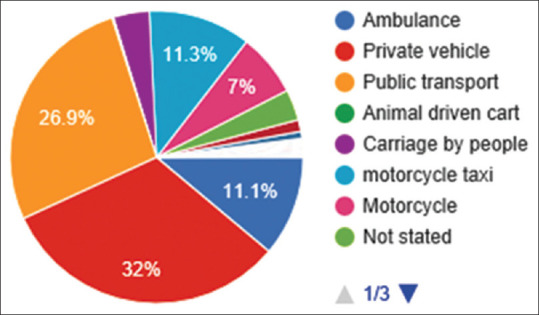

Regarding the method of transport, public and private transport were used in 313 (58.9%) of cases to reach to health-care (HC) facilities, while ambulance service was used in only 58 (11%) of cases, and 54 (10.1%) if we exclude the UK records [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Transport method

With remarkable variations, distance to a health facility varied between 1 and 157 km, with a mean of 36.12 km and a median of 19 km, and time taken from injury to arrive at a health facility was ranging between 2 min and skewed 210 days (mean 6.5 days and median 6 h).

Initial management varied from none in 373 (70.2%), analgesia administration in 24 (4.5%), ambu bag respiration in 9 (1.7%), chin lift-jaw thrust in 3 (0.6%) and IVF in 2 (0.4%). In-hospital initial management with IVF was carried out in 378 (71%), nasal oxygen in 87 (16.4%), blood transfusion in 41 (7.7%) and analgesia in 64 (12%) patients.

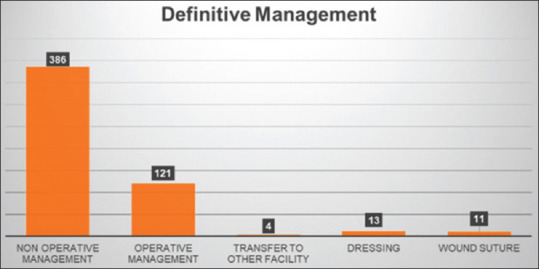

Definitive treatment was completed in 507 (95.5%), majority of patients did not require operative management 386 (72.6%), while 121 (22.8%) were treated operatively. Simple wound suture was carried out in 11 (2.1%), dressing in 13 (2.45%) and few patients were actually transferred to other facilities 4 (0.75%) [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Majority of patients did not require operative management (72.6%)

LOHS was 0–165 days, with a mean of 4.18 days and a median of 13 days.

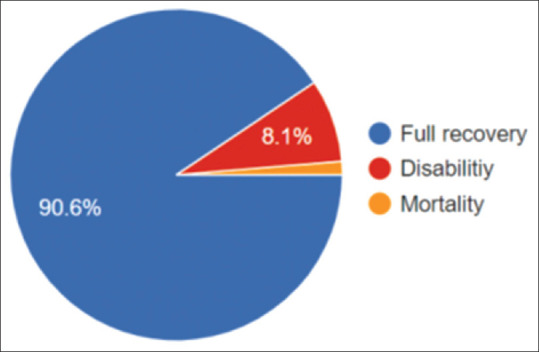

Final outcome was full recovery in 90.6% of patients, morbidity and a disability in 43 (8.1%) and 7 deaths in this study with a mortality rate of 1.3% [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Final outcome

DISCUSSION

Trauma is a universal health problem with potentially devastating immeasurable cost physically, mentally and psychosocially. The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund consider paediatric trauma a major health concern requiring urgent attention in their World Report on Child Injury Prevention in 2008.[1]

Although paediatric trauma is a global phenomenon, approximately 95% of deaths from trauma are in LMICs including Africa[3] where sub-Saharan countries are disproportionally affected.[5] Although trauma is one of the most frequent causes for admission within paediatric surgery in the LMICs, data are very scanty. As a result, the burden and pattern of injuries in Africa is poorly known and not well studied.

The role of reliable data availability to characterise the causes and risk factors associated with childhood injuries, and the impact of registries in determining the burden and effects of paediatric trauma, are essential to design and formulate preventative and therapeutic strategies and guide targeted interventions, allocation of resources, auditing and performance improvement.[6,7] Trauma registries are also needed in LMICs for future research and to inform local policy.[3] This is specially required in the African continent where health services are stretched to encompass a wide range of diverse illnesses within very limited facilities and resources. It is of note that trauma registries represent an integral component of the current trauma systems. As the use of electronic medical recordkeeping expands in LMICs, computerization of trauma registries is an attainable and potentially highly beneficial quality improvement endeavour.[8] While it is true that some countries have consistently kept Trauma registries, there was none that was representative of the continent and perhaps apart from Cape Town, few keep paediatric trauma registry.

At the PAPSA, Addis Ababa 2018, it was recommended to establish a PAPSA body, trauma work group/task force to gather, analyse and report the data to make the results of research available for stakeholders to take the necessary informed action based on the provided data.

Contribution was non consistent as there was a disproportionate response to the questionnaire. While centres from some of the countries contributed over a 100 responses, others did not participate. Therefore, the results presented here represent the situation in those responding countries/centres.

Response was variable ranging from 1 entry (in Madagascar) to 383 in (Benin). The entries from Benin and Nigeria represented >92%. The imbalance of the data in favour of Benin and Nigeria represents a limitation of the study.

The outbreak of COVID-19 had a masking effect as it was accompanied with a significant reduction in the cases reported. It was not clear however whether that was a result of a true reduction in injuries or underreporting.

The spectrum of paediatric trauma in this study showed significant variation in injury mechanisms and patterns. The leading causes of injuries were falls (36.53%) and MVC (33.15%), followed by obstetrical (7.9%), thermal (5.1%) and domestic injuries (4.1%), and others (13.22%). As has been reported, the two main causes of trauma in children who were included in this study were the road traffic accidents and falls from height. Results were comparable to previous studies.[6,9]

The predominance of MVC is possibly, at least partly, due to rapid growth of motorised transport systems and to expansion of industrial production without adequate safety and preventative precautions.[9]

Even in low speed-limit zones, trauma may occur due to inadequate road pavement and lack of designated traffic lanes, pedestrian sidewalks and safety signs and measures.

Limb fractures and TBIs are the most common types of sustained injuries in children, essentially due to MVC or falls. This is consistent with previous reports that also showed a higher proportion of fracture and dislocation injuries in LMICs when compared to High Income Countries. This comes with a cost of significant disability as noted in this study, and also comes as a reminder of the need for availability of orthopaedic services including rehabilitation.[3] Hospitals should be equipped with facilities for appropriate management of such injuries.

Majority of injuries took place at home followed by roads. This is probably due to lack of attention or of safety measures as indicated above.

Regarding the method of transport, public and private transport were used in almost 60% of cases to reach to HC facilities while ambulance service was rarely used in LMIC. This clearly indicates the disparity between HIC and LMIC in provision of safe transport of trauma patients and the potential risks of delay in arrival to HC facilities or deterioration of patients’ condition as a result of injury-related complications.

With remarkable variations, distance to a health facility varied between 1 and 157 km, with a mean of 36.12 km and a median of 19 km, and time taken from injury to arrive at a health facility was ranging between 2 min and skewed 210 days (mean 6.5 days and median 6 h). This is a reflection of the diversity in distribution of health services which can directly affect the outcome as delay in management, as well as the method of transport, may complicate an injury that may have a totally different outcome if handled and managed appropriately and in a timely manner. Comparable variations have also been reported from Nigeria where the percentage of Nigeria’s 0–19 population residing within 2 h of a health facility with a paediatric surgical and anaesthesia workforce ranges from <2% to 22.7%–30.5%.[10]

Majority of patients did not require operative management (72.6%), while 22.8% were treated operatively. Accordingly, it appears that many trauma patients may not need surgery; hence, good health systems can take care of nearly three quarters of patients with minimal surgical requirements.

There was lack of subspecialised services in the majority of participating places due to shortage in subspeciality facilities, including staffing, in many hospitals. This has been especially reported in district hospitals, therefore adding to the burden of centralised services.

Of the constraints facing trauma services in the continent are the diversities in and lack of adequate facilities for primary care for trauma, imaging, definitive management, multidisciplinary team, surgical specialities, anaesthesia, blood bank, OR, intensive care unit and rehabilitation physiotherapy which are necessary in today’s trauma management. In a study from Ghana, assessment revealed marked deficiencies in many essential items and services. Among the unavailable essential items, some were of low cost, such as basic airway supplies, chest tubes and several emergency medications.[11]

Improved trauma management can reduce the time between injury and medical interventions, thus decreasing morbidity and mortality. In general, LMICs have particular difficulties with management of trauma and such problems faced in Africa include the following: (1) Lack of accurate registry necessary for strategic planning and allocation of resources. (2) Lack of political will for promoting trauma services. (3) Lack of funding for developing the service: There may be no high-tech equipment (and sometimes not even electricity, oxygen and running water). (4) Poor infrastructure, accessibility and safe transport facilities. This leads to patients often need to be transferred for long distances and arrive late following injury and (5) Shortage in qualified health professionals and well-trained staff.

Accordingly, and in order to improve the situation, the following directives should be the focus of policy makers and concerned authorities:[1,10,11,12,13]

(1) Representative and meaningful data required. (2) Development of an effective trauma system is required and should be implemented from PHC level to hospital level through ensuring availability of essential equipment in A&Es, radiology departments, blood banks, operating rooms and paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) facilities, and ending in provision of specialised services and rehabilitation. It has direct impact on the quality of service provided as it had improved the outcome in developed countries. (3) Public health education on prevention and first aid. (4) Improving training of attendants for a better prehospital service. Currently, there is training for paediatric surgery not for trauma paramedics. (5) A safe and timely patient transfer system should be established. (6) Communication system to forward the information to receiving health facilities in advance. (7) Triage space and service at the emergency department is essential to ensure prioritisation and timely assessment of injured patients, utilizing checklists to guide appropriate triage. (8) A need to develop paediatric trauma as a specialty Trauma Fellowship for Paediatric Surgeons. (9) Educational and training institutions to adopt and introduce curricula and qualification. (10) Improve maternity, antenatal and perinatal care to reduce birth injuries. (11) Medical legislations and implementation. (12) Development of specialized centres.

The study did not look into availability or lack of other facilities such as imaging and PICU blood bank. Therefore, it is recommended that a thorough quantitative and qualitative study of the available facilities is carried out locally and at national levels against the required approximate ratios per population.

In this study, final outcome was full recovery in 90.6%, morbidity and a disability in 8.1% and mortality rate was 1.3%, perhaps masking a hidden mortality and morbidity of a sizable volume of patients in remote areas.

Impacts

An organised emergency care system can theoretically improve economies by employing simple low-cost interventions that will save millions of lives. Preventable trauma in childhood costs North America and Europe US$ 1.3 trillion a year. Just a 10% reduction in the prevalence of childhood trauma could equate to annual savings of US$ 105 billion (WHO support adverse childhood experience studies 2012–2018 (European status report on preventing child maltreatment (2018).) However, little is known about the cost-effectiveness of emergency care interventions in LMICs, where such interventions may have the greatest impact. Current costing research has considerable variability in the costs and cost descriptions of injury and associated prevention interventions. The economic burden of injury is high, suggesting significant potential for cost savings through injury prevention. A standardised approach to economic evaluation of injury in LMICs is needed to further prioritise investing in injury prevention.[14]

The average annual per capita income is in the range of $400 or less, while the average per capita expenditure on health in most sub-Saharan African countries is <$14 per annum.[15]

The cost-effectiveness of establishing an ambulance system ranged from US$ 18 in Uganda to US$ 568 642 in Malaysia per life year saved. In Thailand, reducing the response time would decrease the yearly national health-care expenditure by US$ 425 million to US$ 850 million for each minute saved.

Strengthening the human resource capacity to provide trauma care ranged from US$ 30 per life year saved for lay first-responders to US$ 188 per life year saved for orthopaedic trauma residency, for instance.[16]

Researchers have estimated that over half of deaths in LMICs, and up to 2.5 billion disability-adjusted life-years annually, could be addressed through the implementation of effective emergency care. These figures are expected to grow due to factors such as increased urbanisation and increased use of motor vehicles with unparalleled development of protective and safety measures. Traumatic injury alone represents a fifth of all ill health worldwide.[6,7]

Although it may not add new or novel information, this study reflects the current trend which has not changed despite efforts exerted to highlight the scale of the problem.

Accordingly, there is a growing need to draw attention of all stakeholders to the importance of proper training of health-care worker (HCW) and allocation of funds to hospitals and all HC facilities that provide paediatric trauma services to manage this nondiscriminating, but potentially avoidable, devastating, disabling, disfiguring, costly and greatly distressing health problem.

CONCLUSIONS

The spectrum of paediatric trauma varied significantly, with different injury mechanisms and patterns. Most of the injuries were in the under 5-year age group.

The two main causes of trauma in children in this study were falls from height and motor vehicle accidents, while obstetrical injuries represent a considerable proportion of paediatric trauma in parts of the continent. Limb fractures and TBIs were the most common types of sustained injuries in children.

Long distance travels to reach HC facilities were noticeable in this study, together with substantial lack of adequate ambulance facilities and shortage in necessary subspeciality services such as that of neurosurgical and orthopaedic services including rehabilitation. Implementing proposed recommendations, developing preventative measures and observing safety precautions by authorities, public and HCWs can and should reduce the burden.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peden M, Oyegbite K, Ozanne-Smith J, Hyder AA, Branche C, Rahman AF, et al., editors. WHO Press, Switzerland: WHO; 2008. World Report on Child Injury Prevention. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wesson DE, Naik-Mathuria B. CRC Press, Tylor &Francis Group; Boca Raton, USA; 2017. Pediatric Trauma: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradshaw CJ, Bandi AS, Muktar Z, Hasan MA, Chowdhury TK, Banu T, et al. International study of the epidemiology of paediatric trauma: PAPSA research study. World J Surg. 2018;42:1885–94. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4396-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz-Casares M. Unintentional childhood injuries in sub-Saharan Africa: An overview of risk and protective factors. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:51–67. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdur-Rahman LO, van As AB, Rode H. Pediatric trauma care in Africa: The evolution and challenges. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012;21:111–5. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wesson HK, Bachani AM, Mtambeka P, Schulman D, Mavengere C, Ward Millar AJ, et al. Changing state of pediatric injuries in South Africa: An analysis of surveillance data from a pediatric emergency department from 2007 to 2011. Surgery. 2017;162:S4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Reilly GM, Joshipura M, Cameron PA, Gruen R. Trauma registries in developing countries: A review of the published experience. Injury. 2013;44:713–21. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenkrantz L, Schuurman N, Hameed M. Trauma registry implementation and operation in low and middle income countries: A scoping review. Glob Public Health. 2019;14:1884–97. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1622761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordberg E. Injuries as a public health problem in Sub-Saharan Africa: Epidemiology and prospects for control. East Afr Med J. 2000;77:S1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Vilaly MA, Jones MA, Stankey MC, Seyi-Olajide J, Onajin-Obembe B, Dasogot A, et al. Access to paediatric surgery: The geography of inequality in Nigeria. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6:e006025. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Japiong KB, Asiamah G, Owusu-Dabo E, Donkor P, Stewart B, Ebel BE, et al. Availability of resources for emergency care at a second-level hospital in Ghana: A mixed methods assessment. Afr J Emerg Med. 2016;6:30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kironji AG, Hodkinson P, de Ramirez SS, Anest T, Wallis L, Razzak J, et al. Identifying barriers for out of hospital emergency care in low and low-middle income countries: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:291. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3091-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lampi M, Junker JP, Tabu JS, Berggren P, Jonson CO, Wladis A. Potential benefits of triage for the trauma patient in a Kenyan emergency department. BMC Emerg Med. 2018;18:49. doi: 10.1186/s12873-018-0200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wesson HK, Boikhutso N, Bachani AM, Hofman KJ, Hyder AA. The cost of injury and trauma care in low- and middle-income countries: A review of economic evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:795–808. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ademuyiwa AO, Usang UE, Oluwadiya KS, Ogunlana DI, Glover-Addy H, Bode CO, et al. Pediatric trauma in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges in overcoming the scourge. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5:55–61. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.93114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner K, Risko N, Burkholder T, Munge K, Wallis L, Reynolds T. Cost-effectiveness of emergency care interventions in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98:341–52. doi: 10.2471/BLT.19.241158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]