Abstract

Burgeoning evidence suggests that circulating tumor cells (CTCs) may disseminate into blood vessels at an early stage, seeding metastases in various cancers such as breast and prostate cancer. Simultaneously, the early-stage CTCs that settle in metastatic sites [termed disseminated tumor cells (DTCs)] can enter dormancy, marking a potential source of late recurrence and therapy resistance. Thus, the presence of these early CTCs poses risks to patients but also holds potential benefits for early detection and treatment and opportunities for possibly curative interventions. This review delves into the role of early DTCs in driving latent metastasis within breast and prostate cancer, emphasizing the importance of early CTC detection in these diseases. We further explore the correlation between early CTC detection and poor prognoses, which contribute significantly to increased cancer mortality. Consequently, the detection of CTCs at an early stage emerges as a critical imperative for enhancing clinical diagnostics and allowing for early interventions.

Keywords: circulating tumor cells, tumor dormancy, prostate cancer, breast cancer, early detection

Global statistics from 2020 report that breast cancer is the most diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among women, and prostate cancer ranks as the second most occurring in men (1). While these 2 cancer types accounted for 10% to 11% of all the cancer-related deaths in 2020, metastatic progression contributes to the majority of deaths associated with all solid malignancies (2). Therefore, the concern of distant relapse is prevalent across various cancer types in both early and advanced stages of the disease. For instance, approximately 20% to 30% of early-stage breast cancer patients encounter distant recurrence, often associated with poor survival (3, 4). Similarly, up to 20% to 40% of prostate cancer patients who have undergone radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy, standard treatments for localized prostate cancer, remain at risk of biochemical recurrence (BCR) concomitant with metastases for over a decade (5, 6). These findings have spurred us and other groups to reexamine the mechanisms and timing of tumor cell dissemination in metastasis.

The process of metastasis typically begins when cancer cells acquire genetic and molecular features that enable detachment and survival from their tissue of origin (resistance to anoikis), local invasion through the surrounding stroma, intravasation into the bloodstream or lymphatic system [termed circulating tumor cells (CTCs)], survival and transportation through the bloodstream, and extravasation and survival at a distant site [termed disseminated tumor cells (DTCs)]. Here, the DTCs can proliferate and form metastatic lesions over the course of months to decades. Under this general description of the metastatic process, 2 fundamental models of metastasis exist: the linear progression model and the parallel progression model (Fig. 1) (6). The linear progression model proposes that tumor cells accumulate genetic alterations within the primary tumor, leading to fully malignant phenotypes, and only then disseminate to form metastases. This process is more common in advanced-stage cancers and can lead to secondary metastases (7, 8). In contrast, the parallel progression model suggests that metastasis is initiated much earlier in the course of disease, even preceding clinical symptoms or the diagnosis of the primary tumor. This scenario leads to greater genetic disparities between the primary tumor and metastatic cells, with tumor cells displaying varying rates of dissemination in different organs (9). This underscores the importance of continuously monitoring and analyzing CTCs at different stages of cancer progression.

Figure 1.

Two fundamental models of metastasis: linear and parallel progression models. In the linear progression model (right box), cancer cells disseminate into the bloodstream after the development of the primary tumor and then seed into distant site(s) (primary metastasis). This primary metastasis may later disseminate again, resulting in secondary metastasis in other organs. In the parallel progression model (left box), cancer cells disseminate from the early lesion before the malignancy of the primary tumor matures, progressing in multiple sites at different rates.

Numerous studies have identified DTCs in patients with various early-stage cancers, including breast and prostate cancer (10-14). Additionally, malignancies with an unknown primary tumor of origin comprise 3% to 5% of all cancer cases (15), further supporting the parallel progression model and the early dissemination of tumor cells before primary tumor detection. Dormant DTCs at distant sites from the primary tumor have emerged as potential culprits behind this latent metastasis, leading to the development of overt metastatic lesions many years after their initial spread (16). These dormant DTCs are recognized by their ability to proliferate after a prolonged cell-cycle arrest in the G0–G1 phase. This characteristic may contribute to the resistance to traditional chemotherapies, posing challenges in targeting these cells and increasing the risk of disease progression (16, 17).

Despite evidence for early cancer cell dissemination, detection often does not occur until later stages, primarily because there is a lack of good screening tools to detect cancer early and the current imaging technologies can only find tumors of a certain minimum size, typically in the hundreds of millions to billions of cells. Further, invasive biopsies are rarely conducted on individuals without clinical indications of cancer confirmed beforehand with imaging. In addition, invasive tumor biopsies have limitations in monitoring mutation evolution and the presence of intratumor heterogeneity (18). These factors may lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment, thereby escalating the mortality rate in patients. In this review, we delve into the crucial role of early DTCs in latent metastasis within breast and prostate cancer and highlight the significance of monitoring and profiling CTCs at an early stage, particularly in the context of tumor screening and clinical diagnostics.

Role of Early DTCs in Latent Metastasis

Metastatic Capacity of Early DTCs

Breast and prostate cancer often metastasize to the bone, lymph nodes, liver, lung, and brain, with the bone being the most common site in the majority of cases (19). The metastatic potential of DTCs was notably highlighted in a 1997 case involving a cadaveric heart donor with regional prostate cancer (13). The recipient developed osteoblastic metastases in various sites, including the thoracic spine, sacrum, and ribs, with confirmed allelic identity to the prostate and kidney of the donor, suggesting the presence of DTCs and undetectable micrometastatic lesions in the donor tissue at an early disease stage.

In another study, DTCs were identified in over 70% of patients before radical prostatectomy (14). Despite no correlation between preoperative DTC status and pathologic risk factors, the study highlighted the prevalent early dissemination of prostate cancer cells to the bone marrow. Even in patients categorized as having no evidence of disease postradical prostatectomy, DTCs were detected in 57% of cases, including 45% of patients more than 5 years postsurgery. This suggests the dormant property of DTCs and delayed recurrence, a topic explored later in this section. The risk of recurrence increased nearly 7-fold in no evidence of disease patients with detectable DTCs compared to those without. Additional studies have shown that DTC presence in untreated prostate cancer patients correlates with poor prognosis (20, 21).

A recent trial (PADDY) analyzed data from 10 307 early-stage breast cancer patients, revealing DTCs in the bone marrow in 27.3% of cases (12). Correlation with baseline characteristics, including tumor grade and size, lymph node status, estrogen/progesterone negativity and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positivity, established DTC detection as a reliable prognostic marker. Moreover, analyzing DTCs in the bone marrow of breast cancer patients postsurgery (stage M0) and patients with metastasis (stage M1) demonstrated that DTCs harbor significantly fewer chromosomal aberrations than the primary tumor or cells from M1-stage patients (22). In addition, investigation of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a precursor to breast cancer, revealed DTCs in 21.1% of pure DCIS and 57.1% with microinvasion (23). Follow-up data informed some DTC-positive patients developing contralateral carcinoma and DCIS, indicating that cancer cell dissemination into bone marrow is an early event in the emergence of breast cancer. These examples support the parallel progression model of metastasis, suggesting DTCs disseminate early and evolve in parallel with the primary tumor.

A study in mice also corroborated this concept in early-stage breast cancer using a HER2-driven mice model (BALB-NeuT) (24). In this model, HER-2-positive and/or cytokeratin-positive (CK+) cells were detected in bone marrow as early as 4 to 9 weeks of age, preceding signs of atypical ductal hyperplasia and visible lung micrometastases around week 20. Gene expression analysis exhibited increased expression of invasion-associated proteases, such as matrix-metalloproteases, and cathepsins, in early lesions compared to large carcinomas. The epithelial-to-mesenchymal (EMT) transcription factor Twist was also expressed in early-stage lesions. Additionally, the evidence for early dissemination of founder cells was observed in lung micrometastases mirroring the growth of primary tumors. Subsequent research using the BALB-NeuT mouse model (25) reported the association of early dissemination with gene expression profiles changed by combined progesterone and HER2 pathway activation in early lesions. Genetic analyses in wildtype mice implanted with mammary tissue from 4-week-old BALB-NeuT mice revealed that 80% of lung metastases originated from early DTCs. This paper further concluded that genetic profiles of DTCs from breast cancer patients, isolated months to years before metastasis, showed distinct copy number alterations from primary tumor clones. These findings challenge the traditional view of metastasis, suggesting tumor cells disseminate before the primary tumor fully matures and becomes symptomatic.

Dormancy of DTCs

Dormant DTCs, distinct from senescent cells, retain the ability to proliferate after a prolonged period of quiescence (16). This characteristic poses a significant challenge in cancer diagnosis and therapy. Remaining inactive for extended periods, these DTCs contribute to the delayed detection of metastasis, resulting in inadequate cancer staging and treatment of aggressive tumors. The ability to detect metastatic lesions several years after the initial spread underscores the deficiencies in existing diagnostic methods. Nevertheless, exploring the complexity of DTC dormancy presents a promising opportunity for intervention before metastases establish a strong foothold (17).

The life cycle of dormant DTCs involves dynamic interactions with the microenvironment (16). Before seeding at a site, CTCs target specific niches based on tissue origin and histological subtype (26) via expression of chemotactic molecules, such as the MAF oncogene and CXCR4, that allows them to navigate to suitable environments like the bone marrow (26-28). In occupied niches, like the bone, prostate cancer cells compete with hematopoietic stem cells for binding to annexin A2 in the bone marrow niche (29, 30). In the niche microenvironment, physical factors like oxygen availability can influence cellular proliferation, affecting drug resistance (31, 32). Moreover, interactions with niche components, such as thrombospondin-1, GAS6, and the extracellular matrix, promote dormancy and chemoresistance (33-36). Cellular reprogramming precedes adaptation and a potential dormancy period before proliferation (37, 38). This coincides with the observation that early dissemination accounts for a significant portion of metastases found at late stages. The reversible nature of dormancy suggests epigenetic involvement during adaptation (37). To sustain long-term dormancy, dormant DTCs interact with immune cells, such as natural killer cells and CD4+/CD8+ T cells, to evade immunosurveillance (39, 40). Reactivation of dormant DTCs, influenced by intrinsic adaptations, changes in immune responses, niche remodeling, and inflammation, completes the cycle (41-46). Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms governing each stage of the dormant DTC life cycle provides valuable insights into potential therapeutic targets for preventing reactivation or inducing and maintaining dormancy in cancer cells.

Methodologies in Liquid Biopsy and Advantages of CTC Detection

Given the pivotal role of early DTCs in cancer progression, it is important to detect CTCs in the early stages of cancer. This consequently may benefit the patient by improving treatment outcomes. In this section, we explore various technologies developed to detect CTCs from liquid biopsies while briefly discussing the broader applications of CTCs in comparison to circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)/cell-free DNA (cfDNA), another common analyte in early cancer detection.

Liquid biopsies, like other blood-based tests, present a less invasive alternative to traditional tumor biopsies. This approach facilitates molecular analysis, including the examination of ctDNA, tumor-derived extracellular vesicles, and CTCs, providing valuable tumor-derived information (47). Liquid biopsies have notable potential in early-stage cancer screening, enabling timely intervention to prevent disease progression. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 liquid biopsy tests (Table 1), including the targeted ctDNA tests such as the cobas® EGFR Mutation Test v2 (48, 49), Guardant360® CDx (50), and FoundationOne® Liquid CDx (51). Devices like CellSearch® (52-58), Parsortix® (59), ClearCell® FX1 (60), and Vortex VTX-1 (61) are FDA-cleared for isolating CTCs. A few Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified laboratory-developed tests, such as the Oncotype DX® AR-V7 Nucleus Detect (62-64) and AdnaTest (65-69) for specific cancer markers in CTCs, are also available. There are also tests for analyzin cfDNA from blood samples, such as the Galleri test (70), which is a multicancer early detection test. Among these options, CTC detection offers specific advantages over the others.

Table 1.

FDA-approved/cleared devices and CLIA-certified LDTs for CTC and ctDNA detection and analysis

| Technology | Company | Material detected in patient blood | Methodology | Cancer type | Key features | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA approved/cleared | ||||||

| cobas® EGFR Mutation Test v2 | Roche Diagnostics | ctDNA | RT-PCR | NSCLC | (FDA approved) A companion diagnostic for treatment with erlotinib, osimertinib, and gefitinib; 42 mutations in exons 18, 19, 20, and 21 of EGFR gene, including the T790 M resistance mutation. | (48, 49) |

| Guardant360® CDx | Guardant Health | ctDNA | Targeted high-throughput hybridization-based capture technology | Any solid cancer | (FDA approved) A companion diagnostic to determine specific therapies for NSCLC patients. SNVs and indels in 55 genes, CNAs in 2 genes and fusions in 4 genes (eg, EGFR, HER2, KRAS). | (50) |

| FoundationOne® Liquid CDx | Foundation Medicine | ctDNA | Targeted high-throughput hybridization-based capture technology | Any solid cancer | (FDA approved) A companion diagnostic to determine specific therapies for NSCLC, prostate, breast, and solid cancer patients. Substitutions, indels in 311 genes, including rearrangements in 8 genes and CAN in 3 genes (eg, LK, EGFR, MET, ROS1, BRCA1, BRCA2, PIK3CA, NTRK1/2/3). | (51) |

| CellSearch® System | Menarini-Silicon Biosystems | CTC | Magnetic beads coated with antibodies targeting EPCAM | Metastatic breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers | (FDA cleared) Enumerates and isolates epithelial CTCs (CD45-, EPCAM+, and CK8+, 18+, and/or 19+). | (52-58) |

| Parasortix® | ANGLE plc | CTC | Size and deformability-based microfluidic isolation | Metastatic breast cancer | (FDA cleared) Enrich and isolate unlabeled CTCs. Further analyses needed to identify, enumerate, or characterize CTCs. | (59) |

| ClearCell® FX1 System | Biolidics Limited | CTC | CTChip® FR biochip: a spiral microfluidics system isolating CTCs based on biomechanical properties using Dean Flow Fractionation principle | (FDA cleared) Enrich and isolate unlabeled CTCs. Further analyses needed to identify, enumerate, or characterize CTCs. | (60) | |

| Vortex VTX-1 Liquid Biopsy System | Vortex Biosciences | CTC | Cell size, shape, and deformability-based isolation through inertial microfluidic chip using laminar microscale vortices | (FDA cleared) Enrich and isolate unlabeled CTCs. Further analyses needed to identify, enumerate, or characterize CTCs. | (61) | |

| CLIA-certified LDT | ||||||

| Oncotype DX® AR-V7 Nucleus Detect test | Epic Sciences | CTC | High-throughput fluorescent imaging of all nucleated cells stained with DAPI and antibodies targting cytokeratins and CD45 | Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | EPCAM-independent CTC detection assay with detection of AR-V7 protein localized in nucleus of CTCs. | (62-64) |

| AdnaTest | Qiagen | CTC | Immunomagnetic beads coated with antibodies tageting EPCAM and tumor-associated markers | Prostate, breast, lung, and colon cancers | EPCAM-based CTC detection assay coupled with mRNA extraction and cDNA synthesis that enables quantifying cancer-specific transcripts (eg, PSA, PSMA, EGFR, AR-FL and AR-V7 for prostate cancer, Muc-1 and Her-2 for breast cancer) in isolated CTCs by RT-PCR. | (65-69) |

| Galleri® test | GRAIL | ctDNA | cfDNA WGBS-seq | Pan-cancer | A multicancer early detection test that identifies methylation differences between normal and cancer-derived DNA at 30 million methylation sites across the genome. | (70) |

Abbreviations: AR-FL, full-length androgen receptor; AR-V7, androgen receptor splice variant 7; CLIA-certified LDT, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified laboratory-developed tests; CNA, copy number alteration; indel, insertion-deletion; CTC, circulating tumor cells; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; EPCAM, epithelial cell adhesion molecule; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PSA, prostate specific antigen; PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen; RT-PCR, real-time PCR; SNV, single nucleotide variant; WGBS-seq, whole genome bisulfite sequencing.

When cells undergo necrosis and apoptosis, cfDNA is released, of which approximately 0.01% to 5% enters peripheral blood (71-73). ctDNA, a subset of cfDNA specifically derived from tumor cells, is detectable through targeted and untargeted methods. Targeted techniques include droplet digital PCR; beads, emulsion, amplification, and magnetics; real-time PCR; tagged-amplicon deep sequencing; and cancer personalized profiling by deep sequencing. Among those, droplet digital PCR; beads, emulsion, amplification, and magnetics; and real-time PCR are highly sensitive and rapid but limited by the small number of mutations assessed in 1 assay (74). Targeted next-generation sequencing methods like tagged-amplicon deep sequencing and cancer personalized profiling by deep sequencing can simultaneously detect numerous rare mutations identified from a large genomic library of a specific cancer type (75, 76). Although targeted next-generation sequencing techniques are comparably sensitive and can detect a larger number of mutations, their screening capability is still limited because only predefined mutations can be assessed. This can further limit the potential discovery of novel drug targets and existing nonstandard therapies that may benefit the patients. Untargeted approaches, such as whole-exome sequencing and whole-genome sequencing, effectively characterize unknown mutations and noncoding variations in ctDNA. However, these methods exhibit lower sensitivity, particularly for rare alterations in early-stage cancer or minimal residual disease (77). Abnormal methylation patterns in cfDNA serve as indicators of cancer cell presence and are measured through DNA methylation detection technologies, including whole genome bisulfite sequencing (78). Whole genome bisulfite sequencing, an untargeted method, has proven effective in studying multiple cancer types, including early-stage breast and prostate cancers, by accurately detecting single-cytosine methylation levels in cfDNA extracted from plasma (79, 80). However, it faces challenges such as potential misrepresentation of genomic sequences and overestimation of methylated cytosine, which may be due to DNA degradation, diminishing the assay sensitivity (81).

CTC isolation techniques broadly fall into 2 categories: immunoaffinity (or immunomagnetic) and biophysical property (eg, size, density)-based isolation methods (82). In immunoaffinity-based isolation, specific biomarkers on the surface of CTCs or leukocytes are used for positive and/or negative enrichment, respectively. Systems using positive enrichment methods, like the CellSearch® System, MagSweeper, magnetic cell separation system, CTC-chip, and graphene oxide chip, employ antibodies targeting epithelial markers such as the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM) and cytokeratins (54, 83-89). Additional tumor-specific markers, such as vimentin [(VIM) an EMT marker], prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA; prostate cancer), HER2 (breast cancer), and EGFR (multicancer), are simultaneously used for CTC identification, enhancing assay sensitivity and providing phenotypic characteristics of CTC subpopulations (90-93). However, there is a concern about losing CTC subpopulations that do not express these markers during enrichment. Conversely, negative enrichment methods, such as the EasySep system and VERSA platform, eliminate non-CTC cells using antibodies targeting CD45, uniquely expressed on normal white blood cells, and potentially isolate all CTC subpopulations (94, 95). These methods employ immunomagnetic technology to yield label-free and device surface unbound CTCs but typically result in lower purity compared to positive enrichment methods. Alternatively, size-based techniques using membrane microfilters (eg, flexible micro spring array) or microfluidic devices (eg, Parsortix®) and density-based techniques (eg, OncoQuick, AccuCyte) separating cell types by centrifugation leverage distinct biophysical properties of CTCs (96-99). These strategies yield label-free, biochemically unmodified, and viable CTCs, facilitating downstream analysis for personalized diagnostic and prognostic information. Typically, the diameter of CTCs (9-19 μm) are larger than other cells in the blood; however, some smaller leukocytes (7-9 μm) are similar in diameter to small CTCs. This poses a challenge for size-based isolation methods, potentially leading to interference from leukocytes and failure in capturing smaller CTCs. The Epic Sciences CTC platform, a nonenrichment-based method, prevents the loss of any CTCs by depositing all nucleated cells from the blood onto slides for subsequent immunofluorescence or genomic analysis (100, 101). This unique platform enables biobanking of unstained samples and analyzing plasma from the same sample; however, this assay does not allow for viable CTC collection.

There are significant advantages to isolating and evaluating CTCs over ctDNA/cfDNA. CTCs offer versatility for DNA, RNA, and protein analyses, along with functional studies using cell lines and xenograft models derived from CTCs (102-107), which is in contrast to ctDNA/cfDNA, which provides solely genomic data. Functional experiments with CTCs allow exploration of signaling pathways, assessment of therapeutic responses, and investigation into treatment resistance mechanisms, offering critical insights for personalized treatment strategies (102, 106, 108-110). Single-cell analyses of CTCs further facilitate the investigation of tumor heterogeneity, presenting a broader view of the disease molecular profile compared to ctDNA (111-114). Additionally, in early-stage cancers, the dynamic nature of CTCs, with their evolving presence and characteristics, makes them valuable biomarkers for monitoring disease progression and predicting response to therapy. This distinctive feature sets CTC detection apart from other liquid biopsy methods, which tend to focus primarily on genomic information.

Detection of CTCs in Early-stage Breast and Prostate Cancers

Breast Cancer

Approximately 70% of metastatic breast cancer patients have detectable CTCs in their blood (115). Despite CTCs being less abundant in early-stage breast cancer compared to metastases, accumulating data have demonstrated the reliability and significance of early CTC detection as a screening tool or biomarker. This section provides an overview of the emerging evidence supporting early cancer cell dissemination in breast cancer (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies including early CTC detection in breast and prostate cancers

| Patient cohort | Classification | Stage of disease | Number of patients with CTC detected (total patients in the group) |

Average CTC count (range) | technology | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | ||||||

| 1371 BC patients before NCT (multistudies) |

Tumor grade | I | 13 (65) | NA | CellSearch® | (115) |

| II | 188 (702) | NA | ||||

| III | 161 (604) | NA | ||||

| 213 BC patients before NT (GeparQuattro study) | Grade of differentiation | 1–2 | 40 (131) | NA | CellSearch® | (116) |

| 3 | 24 (77) | NA | ||||

| Missing | 1 (5) | NA | ||||

| 102 BC patients and 240 benign breast disease and healthy female patients | US BI-RADS scorea | 1 | 12 (64) | 0.2 /4 mL (0–1) | Microfluidic-based immuno-capture CTC platform, CytoSorter® | (117) |

| 2 | 3 (7) | 0.4 /4 mL (0–1) | ||||

| 3 | 25 (82) | 0.4 /4 mL (0–4) | ||||

| 4A | 41 (71) | 0.8 /4 mL (0–6) | ||||

| 4B | 36 (54) | 1.1 /4 mL (0–3) | ||||

| 4C | 27 (31) | 2.9 /4 mL (0–15) | ||||

| 5 | 29 (31) | 2.8 /4 mL (0–9) | ||||

| 6 | 1 (1) | 2 /4 mL (NA) | ||||

| 73 patients with DCIS/LCIS | 6 (73) | 1b /22.5 mL (1–2) | CellSearch® | (56) | ||

| 101 nonmetastatic invasive (M0) BC patients | Histology grade | 1 | 2 (10) | 1b /22.5 mL (1–4) | ||

| 2 | 3 (49) | |||||

| 3 | 6 (36) | |||||

| 39 metastatic BC patients | 23 (39) | 9b /7.5 mL (1–640) | ||||

| 19 DCIS patients and 19 healthy controls | DCIS | 12 (19) | 1.27 /5 mL (NA) | Labyrinth inertial microfluidic device | (118) | |

| Healthy | 4 (19) | 0.259 /5 mL (NA) | ||||

| 28 BC patients and 30 healthy female patients | AJCC stage | IA | 9, including 3 with cluster (11) | Single cell: 3.75 (1–12) Cluster: 11.1 (1–29)c | After RBC and WBC removal, CTCs stained with antibodies on SBS-CTC slides | (119) |

| IIA | 5, including 2 with cluster (9) | Single cell: 1 (1) Cluster: 2 (2)d |

||||

| IIB | 3 (4) | 2 (1–4) | ||||

| IIIA | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | ||||

| Axillary relapse | 2 (2) | 4 (1–7) | ||||

| Prostate cancer | ||||||

| 19 metastatic and 7 localized PC patients | Metastatic | 19 (19) | 86 ± 78e /mL (16–292) | Microfluidic CTC chip | (84) | |

| Localized | 7 (7) | 94 ± 63e /mL (25–174) | ||||

| 45 untreated localized PC patients (prospective study) | NCCN | High-risk (pre-RP) | 19 (26) | 1.3b/mL (0–4.7) | Epic Sciences CTC platform | (112) |

| High-risk (pre-XRT) | 14 (19) | 1.3b/mL (0–22.5) | ||||

| 36 newly diagnosed high-risk, nonmetastatic PC patients | Clinical stage | T1 | 0 (9) | NA | CellSearch® | (120) |

| T2 | 4 (14) | 1.5 /7.5 mL (1–3) | ||||

| T3 | 1 (13) | 1 /7.5 mL (NA) | ||||

| 277 patients including other cancer types | Stage | 1 | 54 | NA (<3 CTCs/mL) | Filtration-based ISET | (121) |

| 2–3 | 11 | NA (3–20 CTCs/mL) | ||||

| 4 | 4 | NA (>20 CTCs/mL) | ||||

| 265 patients including other cancer types | Asymptomatic | Among 133 CTC-positive cancer patients, 50% of men with detected CTCs and normal PSA level revealed to have early prostate cancer by PSMA-PET scan | NA | ISET; Maintrac | ||

| 155 treatment-naïve localized PC patients | NCCN | Low risk | 10 (40) | 1 /7.5 mL (0–2)f | Parsortix® | (122) |

| Intermediate risk | 45 (78) | 2 /7.5 mL (0–4.3)f | ||||

| High risk | 29 (37) | 4 /7.5 mL (0–7.5)f | ||||

| 98 patients prebiopsy (prospective study) | Benign biopsy | 3 (33) | 0 /7.5 mL (0–1.5)f | |||

| Malignant biopsy | 38 (65) | 2 /7.5 mL (0–6)f | ||||

| 38 untreated localized PC patients | NCCN | Low risk | 4 (9) | NA | Parsortix® | (123) |

| Intermediate risk | 14 (23) | NA | ||||

| High risk | 6 (6) | NA | ||||

| 43 CRPC patients (40 with metastasis) |

CRPC | 41 (43) | NA |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BC, breast cancer; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; CTC, circulating tumor cells; DCIS/LCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ/lobular carcinoma in situ; ISET, isolation by size of epithelial tumor; NA, not applicable; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NCT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NT, neoadjuvant therapy; PC, prostate cancer; PSMA-PET, prostate-specific membrane antigen-based positron emission tomography; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RBC, red blood cell; RP, radical prostatectomy; WBC, white blood cell; XRT, radiotherapy.

a US BI-RADS scores indicate different levels of likelihood of breast cancer. Scores 1 to 6 represent negative, benign, probably benign, (low/moderate/high) suspicious, highly suggestive of malignancy, and known cancer, respectively.

b Median.

c Range of observed cluster numbers; 2 to 35 cells per cluster observed; 1 cluster had > 50 cells.

d 2 cells per cluster observed.

e Mean ± SD.

f Median for number of mesenchymal CTCs detected (interquartile range).

Several studies have identified CTCs in patients with early-stage (I–IIIA) breast cancer and reported that the presence of CTCs before neoadjuvant therapy and after adjuvant therapy is associated with decreased overall survival and disease-free survival, highlighting the potential use of CTC detection as an independent prognostic factor (115, 116, 124). Moreover, assessing the CTC detection rate and counts has shown promise in successfully identifying positive breast cancer cases when compared to conventional breast imaging modalities, thus supporting the diagnostic potential of CTC detection (117). In the same study, single CTCs were detected in 19% (n = 12/64) and 43% (n = 3/7) of negative and benign breast disease women, respectively. Although follow-up studies are required, this suggests the presence of CTCs even earlier than breast cancer diagnosis. Indeed, CTCs have been detected as early as patients with DCIS (stage 0). HER2-positive CTCs were found in 8.2% (n = 6/73) of DCIS/lobular carcinoma in situ patients at the range of 1 to 2 cells per 22.5 mL of blood (56). Another study employed a high-throughput inertial microfluidic device, which isolated and identified DAPI+/Pan-CK+/CD45- CTCs in 63.2% of patients diagnosed with DCIS (n = 12/19) (118). The average count was 1.27 CTCs per 5 mL of blood, while healthy controls had 0.259 CTCs per 5 mL of blood, with nondetectable CTCs in most of them (n = 15/19).

Breast cancer studies have also shown that CTCs can be found as single cells or as multicellular clusters, containing both cancer and immune cells. Recent work from Krol et al (119) observed single and clustered CTCs in early-stage breast cancer patients. In this study, CTCs were found as single cells in 57% (n = 16/50) of patients with stage I-IIA while CTC clusters of varying size (from 2 to more than 50 cells) were detected in 3 patients with stage IA (n = 3/11) and 2 with stage IIA (n = 2/9). The observation of clustered CTCs in early-stage breast cancer emphasizes their potential role in early metastatic spread and disease progression as the higher metastatic capacity of clustered CTCs can be attributed to several factors, such as their extensive cell-cell interaction (125, 126), epigenetic modifications promoting stemness and proliferation (127), and interaction with neutrophils (128).

Prostate Cancer

The emergence of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in the 1980s revolutionized the diagnosis and monitoring of prostate cancer, enabling noninvasive screening and tracking of disease progression (129). However, PSA tests are limited by their prognostic accuracy and inconsistent correlation with pathological stage of the disease. In contrast, CTC counts have recently demonstrated greater predictive value for patient survival over traditional PSA levels in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) (54, 130, 131), substantially contributing to disease monitoring and prognosis. Emerging technologies have enabled the isolation of CTCs in mCRPC patients and offer crucial insights into the molecular characteristics of these cells, signifying a paradigm shift (54, 55, 86, 87, 101, 132). The solid clinical value of the presence of CTCs in mCRPC allows for expansion into the area of early-stage prostate cancer detection. Although challenges arise due to the scarcity of isolated CTCs for comprehensive analysis, accumulating data supports the advantages of CTC detection in early-stage prostate cancer (Table 2).

A comprehensive study involving high-risk nonmetastatic prostate cancer patients using the CellSearch® technology identified CTCs in 5 out of 36 patients, with 4 at stage T2 and 1 at stage T3 (120). Each patient had 1 CTC per 7.5 mL of blood, except for a T2 stage patient with 3 CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood. Using the Epic Sciences CTC platform, a prospective study detected at least 1 CTC in 73.3% (n = 33/45) of high-risk localized prostate cancer patients before undergoing radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy with or without androgen deprivation therapy (112). In the same study, a subset of patients who had BCR (defined as a PSA level of 0.2 ng/mL or greater) and metastatic progression after radical prostatectomy, were found to have a higher total number of CTCs, AR + CTCs, and CTC phenotypic heterogeneity score [Shannon Index (133)] when compared to those without BCR and/or metastasis. Furthermore, the application of the microfluidic CTC chip, employing EPCAM-coated microposts, successfully isolated 25 to 174 CTCs per mL from all 7 localized prostate cancer patients and 16 to 292 CTCs per mL from 19 metastatic prostate cancer patients (84). This approach demonstrated remarkable sensitivity (99.1%) and specificity (100%) across all tested cancer types. Moreover, the average capture purity reached 49% in metastatic prostate cancers and 53% in localized cases. Another investigation utilizing isolation by size of epithelial tumor technology revealed that 50% of male patients with CTCs and normal PSA levels were diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer through subsequent PSMA-based positron emission tomography scans (121).

In a large cohort study, CTCs were identified in 54% of localized prostate cancer patients (n = 84/155) using the Parsortix® isolation system (122). Specifically, CTCs were observed in 34% (n = 22/64) of patients with a Gleason score of 3 + 3 and in 25% (n = 10/40) of those with low-risk cancer. Another cohort in the study, comprising 98 prebiopsy patients, was subjected to the prediction of prostate cancer diagnosis. As a result, CTC detection on these patients significantly outperformed PSA levels alone. Notably, the false-positive rate reduced from 31 (PSA level >4 ng/mL) to 3 (CTC score positive) out of 33 benign cases, exhibiting the robust predictive capability of this model and emphasizing the importance CTC detection may provide in reducing overtreatment. Moreover, in 87 patients from the prebiopsy cohort, the combination of CTC counts, transcriptomic analysis of CTCs using a 12-gene panel [including genes AOX1, ACOX2, EYA4, FAT1, FOXA1, GRHL2, HOXB13, KLK2, MNX1, FOLH1(PSMA), RAB3B, and SRD5A2], and PSA levels increased the area under the curve (AUC) for predicting clinically significant prostate cancer from 0.899 to 0.927. Furthermore, integrating these data with available multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging results markedly improved prediction accuracy (AUC 0.936 vs 0.629).

More studies have provided robust evidence supporting the synergy of integrating CTC enumeration and molecular profiling with the current tests in the diagnosis of prostate cancer and predicting metastatic progression. For example, an investigation involving both untreated localized prostate cancer and CRPC patients who have progressed identified various CTC subtypes, including those expressing CK+/ VIM−/CD45−, CK+/VIM+/CD45−, and CK−/VIM+/CD45− (123). While demonstrating high sensitivity for CRPC patients (n = 41/43), the assay identified a remarkable 63% of untreated localized prostate cancer patients to be CTC positive (n = 24/38), including all 6 high-risk patients. Moreover, a combination of CTC counts and PSA levels significantly discriminated metastatic prostate cancer patients from those without metastasis, with an AUC of 0.921. Another study, which involved 51 metastatic and 77 nonmetastatic prostate cancer patients, predicted distant metastases via the expression of 5 genes, SOD2, GPX1, AR, CCNB1, and FGF2, in CTCs achieving remarkable sensitivity (94%) and accuracy (81%) (134).

Altogether, these observations highlight the release of cancer cells into the circulation during early stages of tumor development in breast and prostate cancer and underscore the feasibility of isolating a higher number of CTCs at this stage. Moreover, these findings underscore the clinical significance of CTC counts and phenotyping in enhancing both diagnosis and prognosis prediction of breast and prostate cancers. Detecting early-stage CTCs can further contribute to patient classification for biopsy and treatment, enabling timely management of the disease. By combining CTC counts with genetic insights, these observations hold great promise for early-stage breast and prostate cancer patients, ultimately improving diagnostic accuracy, risk assessment, and treatment decisions.

Molecular Analyses of Early-stage CTCs

Insights into Cancer Progression and Therapy Through Analysis of Early-stage CTCs

Most of the current CTC detection systems employ immunostaining of epithelial- and disease-specific biomarkers to identify CTCs, providing valuable information about disease status and prognosis (90). However, the clinical relevance of CTCs extends beyond diagnosis and prognosis, especially since early-stage CTCs remain largely underexplored. A comprehensive analysis of early-stage CTCs can significantly enhance our understanding of tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution, with direct implications for drug development, patient stratification, and the assessment of mechanisms underlying drug resistance (135, 136).

Transcriptome analysis of CTCs in an MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line-derived orthotopic xenograft model identified a CTC gene signature distinct from primary tumors, lymph nodes, and lung metastases (137). The gene signature included upregulated genes linked to cell plasticity and adaptation and downregulated genes involved in chromatin remodeling and transcription. Assessing CTCs with a panel of CTC-specific genes (ADPRHL1, ELF3, FCF1, TFF1, and TFF3) selected from the gene signature improved CTC detection in both early and advanced breast cancer patients. Additionally, performing the analysis on both CTCs collected before and during therapy enhanced the prediction of distant relapse in the neoadjuvant setting. In a study with DCIS patients, single-cell quantitative PCR revealed the expression of proliferation (PKM2, TIMP1) and mesenchymal (SPARC, TGFB1) markers in the detected CTCs, while not expressing traditional white blood cell markers (118). Targeted DNA sequencing further identified genetic variations found in DCIS and high-risk DCIS. These suggest that CTC-specific molecular profiling can serve as a source of distant relapse and metastasis-related genes in breast cancer, advancing the understanding of tumor cell dissemination and metastasis.

In prostate cancer, single-cell genomic analyses illustrated the heterogeneity of CTCs harvested from a patient who exhibited the highest CTC count among a group of patients prior to radical prostatectomy (112). A diverse population of CTCs, including AR+, CK+, and CK- CTCs, as well as CTC clusters, were observed. Genomic analysis unveiled that only 6 out of the 13 sequenced CTCs exhibited consistent genomic aberrations with the origin of malignancy. Moreover, these 6 CTCs exhibited 3 distinct genomic profiles including common deletions in prostate cancer: 1 CTC with high genomic instability and PTEN loss, 2 with 12p and 22q losses, and 3 with 5q loss. In another cohort of localized high-risk, treatment-naïve prostate cancer patients, the analysis of 21 CTCs and 4 lymphocytes collected from 10 patients revealed a markedly diverse CTC profile with substantial inter- and intrapatient variations (138). Alterations in telomere biology occur early in prostate cancer development and persist throughout tumor progression (139, 140). Consistently, CTCs displayed a higher number of telomere signals than normal lymphocytes, with lower signal intensities indicating a shorter telomere length and an increase in telomere-related genomic instability. However, the length and number of telomeres signals varied considerably in each patient. Moreover, whole-exome sequencing of CTCs and lymphocytes revealed no common genetic variations across all 21 CTCs. Additionally, this study identified single nucleotide variants linked to responses to known drugs, including docetaxel, and gene amplifications associated with pathways, such as the DNA damage repair pathway. Hence, examining isolated CTCs at the single-cell level enables characterizing inter/intrapatient CTC heterogeneity and provides insights for advanced treatments and drug resistance at an earlier disease stage.

Determination of Dormant DTCs Through Analysis of Early-stage CTCs

Despite the importance of investigating cancer cell dormancy, significant challenges arise due to the invasive and technically challenging nature of sample acquisition, particularly from bone marrow. Thus, a functional assessment of whether the identified CTCs favor proliferation or dormancy becomes a viable alternative to invasive biopsies. However, to date, there are a limited number of studies that have delved into the determination of dormancy in DTCs through the evaluation of biomarkers expressed on CTCs.

Ki67 and M30 are used as markers for proliferation and apoptosis, respectively (141, 142). These markers were assessed on CTCs of early-stage breast cancer patients who had remained free of disease for at least 5 years and metastatic breast cancer patients who relapsed more than 5 years postsurgery (143). Notably, 82.4% of all detected CTCs in the early-stage breast cancer group were dormant (Ki67−/M30−), compared with 59.1% in metastatic patients. When analyzing nondormant CTCs, 67.5% were apoptotic (Ki67−/M30+) in the early breast cancer cohort, while all were proliferative (Ki67+/M30−) in metastatic patients. Moreover, apoptotic CTCs were more prevalent among nondormant CTCs in sequential follow-up samples from patients with prolonged disease-free status as opposed to those with late relapse. The findings suggest that monitoring CTC proliferation and apoptosis during the post-treatment period may serve as a valuable tool for predicting delayed disease recurrence.

Another study investigated biomarkers of dormancy on EPCAM-negative CTCs with CD44+/CD24− stem cell properties, known for their heightened capacity to generate breast cancer brain metastasis (144). These CTCs were isolated from blood samples of breast cancer patients with (n = 21) or without (n = 17) brain metastasis (107) and then categorized based on the combinatorial expression of uPAR and integrin β1 (ITGB1), key markers whose loss triggers dormancy in breast cancer (145). The study revealed that the uPAR/ITGB1 biomarker axis was linked to invadopodia formation of CTC organoids, a pivotal step in brain colonization and metastasis development. Moreover, gene expression profiling showed that genes involved in pathways associated with blood-brain barrier permeability, DNA repair, and cell proliferation were elevated in uPAR+/ITGB1+ CTC subsets compared to uPAR−/ITGB1− counterparts. The analysis of uPAR/ITGB1 CTC subsets to understand breast cancer dormancy and brain metastasis further suggests the potential use of CTC biomarkers to determine the dormant state of disease. Building on their previous findings, the same group further discovered that increased mTORC2 activity, coupled with decreased mTORC1 signaling, significantly contributed to the promotion of breast cancer-derived CTC seeding and the long-term dormancy of DTCs within the bone marrow (146). Ongoing research into markers on CTCs that delineate tumor dormancy will further advance early detection and treatment strategies for cancer-associated metastasis, representing a significant breakthrough in personalized medicine applications.

Alternative Approaches to Improve CTC Detection in Early-stage Cancers

Despite the FDA clearance of the CellSearch® System for monitoring advanced cancer patients and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments certification of a few selected laboratory-developed tests, further improvements in CTC isolation, detection, and analysis technologies are necessary for CTCs to be effectively used in clinical practice. The primary challenge with early-stage CTC detection lies in the low abundance of CTCs in blood samples, limiting detection sensitivity. To address this challenge, (1) the blood volume analyzed can be increased and (2) the detection technologies further improved, utilizing diverse cancer cell attributes such as size, density, morphology, or protein biomarkers. One of the approaches to capture CTCs from a larger blood volume is using a temporary indwelling intravascular aphaeretic system, including an anti-EpCAM-coated microfluidic herringbone graphene oxide chip (147). The validation of this system in canine models exhibited the capability of screening 1% to 2% of the entire blood volume over a 2-hour period and 3.5-fold higher CTC capture than serial draws. Additional methods include the intravenous insertion of the GILUPI CellCollector, a functionalized medical wire coated with anti-EpCAM antibodies (148), and the MagWIRE, a magnetic wire used in conjunction with anti-EpCAM coated magnetic particles for immunomagnetic capture of CTCs (149). While effective, these methods rely on cell surface markers, potentially missing EpCAM low-expressing CTCs like those undergoing EMT. Leukapheresis, an automated centrifugal enrichment method processing 1 to 3 L of peripheral blood, offers a promising approach to obtain large volumes of concentrated CTCs and white blood cells. Although leukapheresis products pose challenges due to the abundance of billions of white blood cells (150, 151), recent advancements in magnetic sorting and permeability-enhanced magnetic sorting using the LPCTC-iChip, have addressed some of these issues (152). This ultrahigh-throughput microfluidic device can efficiently sort the entire leukapheresis product, comprising over 6 billion nucleated cells, leading to a 100-fold increase in CTC isolation capacity and yielding unlabeled whole CTC populations.

Label-free CTC detection eliminates the need for antibodies, aiming to capture a larger population of CTCs with enhanced generalizability to various cancer types. These methods include not only techniques like dielectrophoresis, photoacoustic flowmetry, and mass spectrometry (153-156) but also advanced imaging approaches (157-160) that analyze CTCs based on their intrinsic physical and biochemical properties. For instance, high-resolution brightfield/phase contrast imaging discerns morphological features, enabling the detection based on size, shape, and texture variations. Holographic imaging techniques analyze diffraction patterns and optical properties associated with the surface and internal subcellular structures of cells (160-163). These imaging methods provide more nuanced characteristics of CTCs often overlooked by traditional methods. Overall, label-free methods can minimize the complexity and cost of the detection process and reduce the risk of altering cell properties during labeling. To further enhance detection technologies, label-free methods can be integrated with cutting-edge deep learning and artificial intelligence (AI), improving accuracy in CTC enumeration and characterization (164, 165). AI algorithms, particularly deep learning models, adeptly analyze complex imaging data from label-free techniques, identifying intricate patterns and features of CTCs and effectively differentiating them from other blood components. AI can also consolidate and interpret data from diverse sources, such as genetic profiles and clinical parameters, offering valuable insights into the prognostic and therapeutic implications of CTCs. This integration holds promise for advancing personalized medicine through improved early cancer diagnosis, disease monitoring, and treatment efficacy evaluation.

Conclusions

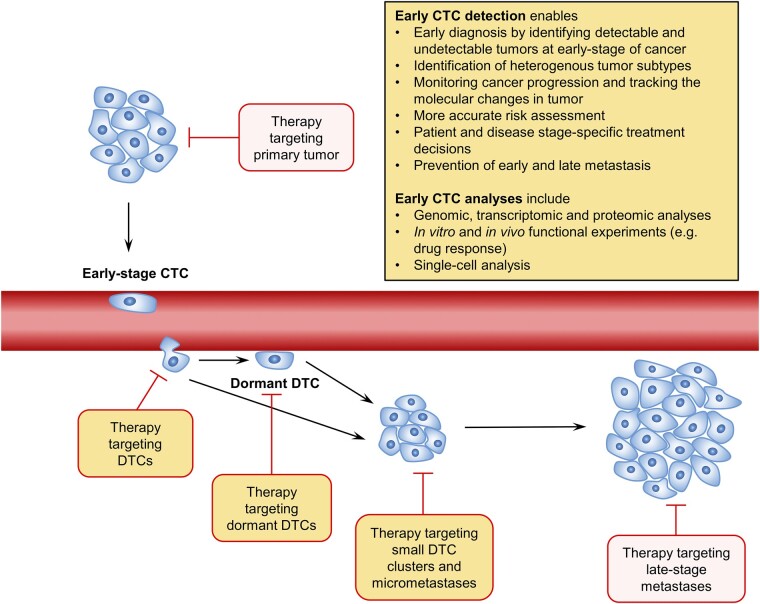

The role of early DTCs in establishing metastasis and their dormant property put forward the value of CTC detection early in the disease stage. Ongoing clinical trials, notably in prostate (PROLIPSY; NCT04556916) and breast (NCT03511859) cancer, signal a potential shift toward utilizing CTCs in early cancer detection. Fundamentally, the study of CTCs holds significant potential in the early detection and diagnosis of various clinically relevant cancers, underscoring the importance of CTC counts and genetic profiles in improving the accuracy of diagnosis, risk assessment, and tailoring patient specific treatment decisions, especially for early-stage nonmetastatic cancer patients (Fig. 2). Early detection of CTCs in the bloodstream may also serve as advanced indicators of metastasis, providing a minimally invasive means of monitoring cancer progression. Exploring the molecular variability between early-disseminated CTCs and those derived later could significantly influence treatment strategies. Uncovering CTC-specific biomarkers indicative of tumor dormancy presents an opportunity to predict future recurrence. Furthermore, targeting dormant tumor cells to inhibit reactivation is a promising area of ongoing research. The outcome of the research may benefit patients by reduced use of more aggressive therapies at later stages of the disease and the economic burden associated with treatment.

Figure 2.

Clinical advantage of early detection of CTCs. The detection of CTCs at an early stage of cancer allows for earlier diagnosis and improved prognosis prediction. Comprehensive analysis of CTCs identifies various subpopulations representing heterogeneous characteristics of primary tumors, potentially leading to metastases at different distant sites. The CTC profile obtained from the analyses enhances patient and disease stage-specific therapy selection and enables the tracking of molecular changes in the tumor over the course of treatment with noninvasive biopsy. Identification and targeting of dormant DTCs may prevent the emergence of late metastasis. Abbreviations: CTC, circulating tumor cells; DTC, disseminated tumor cells.

In early-stage disease, CTC detection may serve as a companion diagnostic, prompting more detailed evaluation for occult cancer patients. For example, breast or prostate magnetic resonance imaging can be recommended rather than just ultrasound or digital rectal examination, respectively. Additionally, it can help in predicting the necessity of adjuvant systemic therapy; for example, a woman diagnosed with localized breast cancer and a positive CTC test may choose mastectomy with adjuvant systemic chemotherapy. Similarly, a man with localized prostate cancer and detectable CTCs may opt for prostatectomy with adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy. However, the failure to differentiate between aggressive and inactive cancers may result in overdiagnosis and overtreatment, leading to a possibility of increased patient harm and medical expenses as opposed to the expected benefits from early cancer detection. Therefore, it is crucial to refine early cancer detection by molecular characterization of CTCs, differentiating subsets, and integrating CTCs with other biomarkers, including circulating proteins, ctDNA/cfDNA, microRNAs, and immune cell subsets. The integration of CTC detection with existing technologies, such as urinary biomarker assays and radiological imaging, provides a comprehensive approach to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Ongoing research and collaborative efforts are vital for the successful development and implementation of these strategies in clinical practice.

Contributor Information

Song Yi Bae, Astrin Biosciences, St. Paul, MN 55114, USA.

Kaylee Judith Kamalanathan, Astrin Biosciences, St. Paul, MN 55114, USA.

Catalina Galeano-Garces, Astrin Biosciences, St. Paul, MN 55114, USA.

Badrinath R Konety, Astrin Biosciences, St. Paul, MN 55114, USA; Allina Health Cancer Institute, Minneapolis, MN 55407, USA; Department of Urology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55454, USA.

Emmanuel S Antonarakis, Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; Division of Hematology, Oncology and Transplantation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

Jayant Parthasarathy, Astrin Biosciences, St. Paul, MN 55114, USA.

Jiarong Hong, Astrin Biosciences, St. Paul, MN 55114, USA; Department of Mechanical Engineering and St. Anthony Falls Laboratory, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55414, USA.

Justin M Drake, Astrin Biosciences, St. Paul, MN 55114, USA; Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; Department of Pharmacology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

Funding

E.S.A. is partially supported by National Cancer Institute Grant P30 CA077598. J.M.D. is supported by the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota and by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute Grant R01CA269801. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

B.R.K. serves as a consultant and chief medical officer at Astrin Biosciences. J.P. serves as chief executive officer at Astrin Biosciences. E.S.A. reports grants and personal fees from Janssen, Sanofi, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Curium, Merck, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Clovis; personal fees from Astellas, Amgen, Blue Earth, Exact Sciences, Invitae, Eli Lilly, and Foundation Medicine; grants from Novartis, Celgene, and Orion and has a patent for an AR-V7 biomarker technology that has been licensed to Qiagen. J.H. has no conflicts relevant to this work. However, he serves as the chief technology officer at Astrin Biosciences. J.M.D. has no conflicts relevant to this work. However, he serves as a consultant and chief scientific officer of Astrin Biosciences. The interest related to J.H. and J.M.D. has been reviewed and managed by the University of Minnesota in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. S.Y.B., K.K., C.G.G., B.R.K., J.P., J.H., and J.M.D. all own stock options at Astrin Biosciences.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331(6024):1559‐1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) . Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1687‐1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tevaarwerk AJ, Gray RJ, Schneider BP, et al. Survival in patients with metastatic recurrent breast cancer after adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2013;119(6):1140‐1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suardi N, Porter CR, Reuther AM, et al. A nomogram predicting long-term biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2008;112(6):1254‐1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. Fifteen-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(17):1547‐1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bross IDJ, Viadana E, Pickren J. Do generalized metastases occur directly from the primary? J Chronic Dis. 1975;28(3):149‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weinberg RA. Mechanisms of malignant progression. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(6):1092‐1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klein CA. Parallel progression of primary tumours and metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(4):302‐312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Friberg S, Nyström A. Cancer metastases: early dissemination and late recurrences. Cancer Growth Metastasis. 2015;8:43‐49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Banys M, Gruber I, Krawczyk N, et al. Hematogenous and lymphatic tumor cell dissemination may be detected in patients diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(3):801‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hartkopf AD, Brucker SY, Taran FA, et al. Disseminated tumour cells from the bone marrow of early breast cancer patients: results from an international pooled analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2021;154:128‐137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riethmüller G, Klein CA. Early cancer cell dissemination and late metastatic relapse: clinical reflections and biological approaches to the dormancy problem in patients. Semin Cancer Biol. 2001;11(4):307‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morgan TM, Lange PH, Porter MP, et al. Disseminated tumor cells in prostate cancer patients after radical prostatectomy and without evidence of disease predicts biochemical recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(2):677‐683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet. 2012;379(9824):1428‐1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Phan TG, Croucher PI. The dormant cancer cell life cycle. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(7):398‐411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Recasens A, Munoz L. Targeting cancer cell dormancy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40(2):128‐141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, Bardelli A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(9):531‐548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roodman GD. Mechanisms of bone metastasis. Discov Med. 2009;4(22):144‐148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Köllermann J, Weikert S, Schostak M, et al. Prognostic significance of disseminated tumor cells in the bone marrow of prostate cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant hormone treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(30):4928‐4933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weckermann D, Müller P, Wawroschek F, Harzmann R, Riethmüller G, Schlimok G. DISSEMINATED CYTOKERATIN POSITIVE TUMOR CELLS IN THE BONE MARROW OF PATIENTS WITH PROSTATE CANCER: DETECTION AND PROGNOSTIC VALUE. J Urol. 2001;166(2):699‐704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmidt-Kittler O, Ragg T, Daskalakis A, et al. From latent disseminated cells to overt metastasis: genetic analysis of systemic breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100(13):7737‐7742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sänger N, Effenberger KE, Riethdorf S, et al. Disseminated tumor cells in the bone marrow of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(10):2522‐2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hüsemann Y, Geigl JB, Schubert F, et al. Systemic spread is an early step in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(1):58‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hosseini H, Obradović MMS, Hoffmann M, et al. Early dissemination seeds metastasis in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;540(7634):552‐558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pavlovic M, Arnal-Estapé A, Rojo F, et al. Enhanced MAF oncogene expression and breast cancer bone metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(12):djv256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Müller A, Homey B, Soto H, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410(6824):50‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taichman RS, Cooper C, Keller ET, Pienta KJ, Taichman NS, McCauley LK. Use of the stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 pathway in prostate cancer metastasis to bone1. Cancer Res. 2002;62(6):1832‐1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shiozawa Y, Pedersen EA, Havens AM, et al. Human prostate cancer metastases target the hematopoietic stem cell niche to establish footholds in mouse bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1298‐1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shiozawa Y, Havens AM, Jung Y, et al. Annexin II/annexin II receptor axis regulates adhesion, migration, homing, and growth of prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105(2):370‐380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(10):721‐732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carcereri de Prati A, Butturini E, Rigo A, et al. Metastatic breast cancer cells enter into dormant state and express cancer stem cells phenotype under chronic hypoxia. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(10):3237‐3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carlson P, Dasgupta A, Grzelak CA, et al. Targeting the perivascular niche sensitizes disseminated tumour cells to chemotherapy. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(2):238‐250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ghajar CM, Peinado H, Mori H, et al. The perivascular niche regulates breast tumour dormancy. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(7):807‐817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shiozawa Y, Pedersen EA, Patel LR, et al. GAS6/AXL axis regulates prostate cancer invasion, proliferation, and survival in the bone marrow niche. Neoplasia. 2010;12(2):116‐127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yumoto K, Eber MR, Wang J, et al. Axl is required for TGF-β2-induced dormancy of prostate cancer cells in the bone marrow. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):36520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robinson NJ, Parker KA, Schiemann WP. Epigenetic plasticity in metastatic dormancy: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(14):903‐903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Suzuki M, Mose ES, Montel V, Tarin D. Dormant cancer cells retrieved from metastasis-free organs regain tumorigenic and metastatic potency. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(2):673‐681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goddard ET, Bozic I, Riddell SR, Ghajar CM. Dormant tumour cells, their niches and the influence of immunity. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(11):1240‐1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vinay DS, Ryan EP, Pawelec G, et al. Immune evasion in cancer: mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35:S185‐S198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luo X, Cheng C, Tan Z, et al. Emerging roles of lipid metabolism in cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Panigrahy D, Edin ML, Lee CR, et al. Epoxyeicosanoids stimulate multiorgan metastasis and tumor dormancy escape in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):178‐191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Albrengues J, Shields MA, Ng D, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps produced during inflammation awaken dormant cancer cells in mice. Science. 2018;361(6409):eaao4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ottewell PD, Wang N, Meek J, et al. Castration-induced bone loss triggers growth of disseminated prostate cancer cells in bone. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(5):769‐781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ottewell PD, Wang N, Brown HK, et al. OPG-Fc inhibits ovariectomy-induced growth of disseminated breast cancer cells in bone. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(4):968‐977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ribas A. Adaptive immune resistance: how cancer protects from immune attack. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(9):915‐919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Heidrich I, Ačkar L, Mossahebi Mohammadi P, Pantel K. Liquid biopsies: potential and challenges. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(3):528‐545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Torres S, González Á, Cunquero Tomas AJ, et al. A profile on cobas® EGFR mutation test v2 as companion diagnostic for first-line treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;20(6):575‐582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jenkins S, Cross D, Scudder SA. Chapter 23—osimertinib (TAGRISSOTM) and the cobas® EGFR mutation test v2. In: Jørgensen JT, ed. Companion and Complementary Diagnostics. Academic Press; 2019:429‐443. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bauml JM, Li BT, Velcheti V, et al. Clinical validation of Guardant360 CDx as a blood-based companion diagnostic for sotorasib. Lung Cancer. 2022;166:270‐278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Woodhouse R, Li M, Hughes J, et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne liquid CDx, a novel 324-gene cfDNA-based comprehensive genomic profiling assay for cancers of solid tumor origin. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9):e0237802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Riethdorf S, Fritsche H, Müller V, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a validation study of the CellSearch system. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(3):920‐928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. FDA . 510(k) Summary of Cell Search Technology. 2010. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf10/K103502.pdf

- 54. Scher HI, Jia X, de Bono JS, et al. Circulating tumor cell number as a prognostic marker in progressive castration-resistant prostate cancer: use in clinical practice and clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(3):233‐239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sperger JM, Emamekhoo H, McKay RR, et al. Prospective evaluation of clinical outcomes using a multiplex liquid biopsy targeting diverse resistance mechanisms in metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(26):2926‐2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ignatiadis M, Rothé F, Chaboteaux C, et al. HER2-positive circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e15624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bork U, Rahbari NN, Schölch S, et al. Circulating tumour cells and outcome in non-metastatic colorectal cancer: a prospective study. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(8):1306‐1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Moreno JG, Miller MC, Gross S, Allard WJ, Gomella LG, Terstappen LWMM. Circulating tumor cells predict survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Urology. 2005;65(4):713‐718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Templeman A, Miller MC, Cooke MJ, et al. Analytical performance of the FDA-cleared parsortix® PC1 system. J Circ Biomark. 2023;12:26‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee Y, Guan G, Bhagat AA. ClearCell® FX, a label-free microfluidics technology for enrichment of viable circulating tumor cells. Cytometry Part A. 2018;93(12):1251‐1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sollier-Christen E, Renier C, Kaplan T, Kfir E, Crouse SC. VTX-1 liquid biopsy system for fully-automated and label-free isolation of circulating tumor cells with automated enumeration by BioView platform. Cytometry Part A. 2018;93(12):1240‐1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Werner SL, Graf RP, Landers M, et al. Analytical validation and capabilities of the epic CTC platform: enrichment-free circulating tumour cell detection and characterization. J Circ Biomark. 2015;4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Scher HI, Lu D, Schreiber NA, et al. Association of AR-V7 on circulating tumor cells as a treatment-specific biomarker with outcomes and survival in castration-resistant prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(11):1441‐1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Graf RP, Hullings M, Barnett ES, Carbone E, Dittamore R, Scher HI. Clinical utility of the nuclear-localized AR-V7 biomarker in circulating tumor cells in improving physician treatment choice in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2020;77(2):170‐177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Wang H, et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and Abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):1028‐1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Armstrong AJ, Halabi S, Luo J, et al. Prospective multicenter validation of androgen receptor splice variant 7 and hormone therapy resistance in high-risk castration-resistant prostate cancer: the PROPHECY study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(13):1120‐1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lokhandwala PM, Riel SL, Haley L, et al. Analytical validation of androgen receptor splice variant 7 detection in a clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIA) laboratory setting. J Mol Diagn. 2017;19(1):115‐125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sharp A, Welti JC, Lambros MBK, et al. Clinical utility of circulating tumour cell androgen receptor splice variant-7 status in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;76(5):676‐685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Danila DC, Samoila A, Patel C, et al. Clinical validity of detecting circulating tumor cells by AdnaTest assay compared to direct detection of tumor mRNA in stabilized whole blood, as a biomarker predicting overall survival for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Cancer J. 2016;22(5):315‐320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fiala C, Diamandis EP. Can a broad molecular screen based on circulating tumor DNA aid in early cancer detection? J Appl Lab Med. 2020;5(6):1372‐1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sender R, Noor E, Milo R, Dor Y. What fraction of cellular DNA turnover becomes cfDNA? eLife. 2023;12:RP89321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Diaz LA, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsies: genotyping circulating tumor DNA. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):579‐586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bardelli A, Pantel K. Liquid biopsies, what we do not know (yet). Cancer Cell. 2017;31(2):172‐179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Li H, Jing C, Wu J, et al. Circulating tumor DNA detection: a potential tool for colorectal cancer management. Oncol Lett. 2019;17(2):1409‐1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Forshew T, Murtaza M, Parkinson C, et al. Noninvasive identification and monitoring of cancer mutations by targeted deep sequencing of plasma DNA. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(136):136ra68‐136ra68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Newman AM, Bratman SV, To J, et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat Med. 2014;20(5):548‐554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bos MK, Angus L, Nasserinejad K, et al. Whole exome sequencing of cell-free DNA—a systematic review and Bayesian individual patient data meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;83:101951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Luo H, Wei W, Ye Z, Zheng J, Xu RH. Liquid biopsy of methylation biomarkers in cell-free DNA. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(5):482‐500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Liu MC, Oxnard GR, Klein EA, et al. Sensitive and specific multi-cancer detection and localization using methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(6):745‐759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Legendre C, Gooden GC, Johnson K, Martinez RA, Liang WS, Salhia B. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of cell-free DNA identifies signature associated with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Olova N, Krueger F, Andrews S, et al. Comparison of whole-genome bisulfite sequencing library preparation strategies identifies sources of biases affecting DNA methylation data. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bankó P, Lee SY, Nagygyörgy V, et al. Technologies for circulating tumor cell separation from whole blood. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Miltenyi S, Müller W, Weichel W, Radbruch A. High gradient magnetic cell separation with MACS. Cytometry. 1990;11(2):231‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, et al. Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature. 2007;450(7173):1235‐1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Talasaz AH, Powell AA, Huber DE, et al. Isolating highly enriched populations of circulating epithelial cells and other rare cells from blood using a magnetic sweeper device. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(10):3970‐3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kozminsky M, Fouladdel S, Chung J, et al. Detection of CTC clusters and a dedifferentiated RNA-expression survival signature in prostate cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2018;6(2):1801254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Stott SL, Lee RJ, Nagrath S, et al. Isolation and characterization of circulating tumor cells from patients with localized and metastatic prostate cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(25):25ra23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pantel K, Denève E, Nocca D, et al. Circulating epithelial cells in patients with benign colon diseases. Clin Chem. 2012;58(5):936‐940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yoon HJ, Kim TH, Zhang Z, et al. Sensitive capture of circulating tumour cells by functionalized graphene oxide nanosheets. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8(10):735‐741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Lin D, Shen L, Luo M, et al. Circulating tumor cells: biology and clinical significance. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):1‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Niu Z, Kozminsky MA, Day KC, Palmbos PL, Day ML, Nagrath S. Abstract B35: isolation and characterization of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from bladder cancer patients using a highly sensitive graphene oxide-based microfluidic device (GO chip). Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(11_Supplement):B35. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Satelli A, Brownlee Z, Mitra A, Meng QH, Li S. Circulating tumor cell enumeration with a combination of epithelial cell adhesion molecule– and cell-surface vimentin–based methods for monitoring breast cancer therapeutic response. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):259‐266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kirby BJ, Jodari M, Loftus MS, et al. Functional characterization of circulating tumor cells with a prostate-cancer-specific microfluidic device. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Liu Z, Fusi A, Klopocki E, et al. Negative enrichment by immunomagnetic nanobeads for unbiased characterization of circulating tumor cells from peripheral blood of cancer patients. J Transl Med. 2011;9(1):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Sperger JM, Strotman LN, Welsh A, et al. Integrated analysis of multiple biomarkers from circulating tumor cells enabled by exclusion-based analyte isolation. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(3):746‐756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Harouaka RA, Zhou MD, Yeh YT, et al. Flexible micro spring array device for high-throughput enrichment of viable circulating tumor cells. Clin Chem. 2014;60(2):323‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hvichia GE, Parveen Z, Wagner C, et al. A novel microfluidic platform for size and deformability based separation and the subsequent molecular characterization of viable circulating tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(12):2894‐2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Rosenberg R, Gertler R, Friederichs J, et al. Comparison of two density gradient centrifugation systems for the enrichment of disseminated tumor cells in blood. Cytometry. 2002;49(4):150‐158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Campton DE, Ramirez AB, Nordberg JJ, et al. High-recovery visual identification and single-cell retrieval of circulating tumor cells for genomic analysis using a dual-technology platform integrated with automated immunofluorescence staining. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Scher HI, Armstrong AJ, Schonhoft JD, et al. Development and validation of circulating tumor cell enumeration (epic sciences) as a prognostic biomarker in men with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2021;150:83‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gupta S, Halabi S, Yang Q, et al. PSMA-positive circulating tumor cell detection and outcomes with Abiraterone or enzalutamide treatment in men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(10):1929‐1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yu M, Bardia A, Aceto N, et al. Ex vivo culture of circulating breast tumor cells for individualized testing of drug susceptibility. Science. 2014;345(6193):216‐220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]