Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The authors created a postoperative postanesthesia care unit (PACU) pathway to bypass routine intensive care unit (ICU) admissions of patients undergoing routine craniotomies, to improve ICU resource utilization and reduce overall hospital costs and lengths of stay while maintaining quality of care and patient satisfaction. In the present study, the authors evaluated this novel PACU-to-floor clinical pathway for a subset of patients undergoing craniotomy with a case time under 5 hours and blood loss under 500 ml.

METHODS

A single-institution retrospective cohort study was performed to compare 202 patients enrolled in the PACU-to-floor pathway and 193 historical controls who would have met pathway inclusion criteria. The pathway cohort consisted of all adult supratentorial brain tumor cases from the second half of January 2021 to the end of January 2022 that met the study inclusion criteria. Control cases were selected from the beginning of January 2020 to halfway through January 2021. The authors also discuss common themes of similar previously published pathways and the logistical and clinical barriers overcome for successful PACU pathway implementation.

RESULTS

Pathway enrollees had a median age of 61 years (IQR 49–69 years) and 53% were female. Age, sex, pathology, and American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status distributions were similar between pathway and control patients (p > 0.05). Most of the pathway cases (96%) were performed on weekdays, and 31% had start times before noon. Nineteen percent of pathway patients had 30-day readmissions, most frequently for headache (16%) and syncope (10%), whereas 18% of control patients had 30-day readmissions (p = 0.897). The average time to MRI was 6 hours faster for pathway patients (p < 0.001) and the time to inpatient physical therapy and/or occupational therapy evaluation was 4.1 hours faster (p = 0.046). The average total length of stay was 0.7 days shorter for pathway patients (p = 0.02). A home discharge occurred in 86% of pathway cases compared to 81% of controls (p = 0.225). The average total hospitalization charges were $13,448 lower for pathway patients, representing a 7.4% decrease (p = 0.0012, adjusted model). Seven pathway cases were escalated to the ICU postoperatively because of attending physician preference (2 cases), agitation (1 case), and new postoperative neurological deficits (4 cases), resulting in a 96.5% rate of successful discharge from the pathway. In bypassing the ICU, critical care resource utilization was improved by releasing 0.95 ICU days per patient, or 185 ICU days across the cohort.

CONCLUSIONS

The featured PACU-to-floor pathway reduces the stay of postoperative craniotomy patients and does not increase the risk of early hospital readmission.

Keywords: craniotomy, postoperative pathway, neurosurgery outcomes, tumor

POSTOPERATIVE care for patients undergoing open cranial surgery has traditionally taken place in the resource-intensive ICU setting. Growing evidence suggests that the majority of craniotomy patients monitored in the ICU postoperatively do not need ICU-level care or intervention. 1–3 Given the high cost and limited supply of ICU resources, institutions have developed streamlined care pathways for select craniotomy patients to bypass the ICU and undergo immediate postoperative monitoring in stepdown units such as a postanesthesia care unit (PACU).4–6 Pathways for same-day or early discharge after craniotomy have met with similar success.7,8

On the basis of the existing literature and our own institutional experience, we developed a novel PACU-to-floor pathway, or PACU pathway, to safely decrease ICU days and lengths of stay (LOSs), improve resource utilization, and lower overall healthcare-associated costs.9 This pathway expands on previously described protocols by extending the PACU observation period to 4 hours, defining a tapered neurological examination structure, and engaging a multidisciplinary team to evaluate patient suitability to continue in the pathway. This pathway was rigorously assessed to ensure it is effective for weekend cases and latestart cases. We also collated our experience with the literature to demonstrate the range of metrics that should be applied to examine other clinical pathways for brain tumor surgery. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and subsequent recovery effort, both of which have strained the US healthcare system, have further highlighted the importance of maximizing resource utilization to provide quality care to neurosurgical patients.10 Here, we describe the results of our PACU pathway protocol and evaluate its effect on hospital costs, LOS, and readmission.

Methods

Objective

We hypothesized that our PACU pathway would reduce hospital LOSs and costs. Our primary analyses compared the time to MRI capture, time to physical therapy (PT) and/or occupational therapy (OT) evaluation, time to discharge, and hospital charge between PACU pathway patients and a historical control cohort. Secondary analyses included differences in discharge dispositions and readmissions. Prespecified subset analyses included time-of-day and time-of-week (weekday vs weekend) cases.

PACU Pathway Design and Implementation

Initial implementation of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital craniotomy-to-floor pathway involved collaboration among the neurosurgery department, nursing, anesthesia, and the hospital safety/quality team in January 2020. Logistical barriers were identified via tabletop simulation exercises, and nursing education events were conducted in the lead-up to implementation. All stakeholders had the opportunity to review protocol drafts prior to final implementation.

During the booking process, the attending surgeon identifies cases that are likely to meet the PACU pathway inclusion criteria. On the day of surgery, the nurses in charge verify that these patients do not meet preoperative or intraoperative exclusion criteria as described below, ensuring allocation of nursing resources only to actual pathway enrollees. The nursing-to-patient staffing ratio in the PACU is 1:1 or 1:2, ensuring close monitoring of the PACU pathway throughout the postoperative period. Once the patient arrives in the PACU, there is a 4-hour monitoring period with regular neurological examinations and vital sign checks every 15 minutes for the 1st hour, every 30 minutes for the next 2 hours, and then every hour thereafter until the patient is transferred to the floor. Samples for laboratory work are drawn on patient arrival to monitor hematological stability, and tests include basic chemistry, complete blood counts, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio, and partial thromboplastin time test; the patient’s arterial line is also maintained while in the PACU. A neurosurgeon or advance practice provider from the neurosurgery service examines the patient within 30 minutes of arrival and documents the examination by the end of the 4-hour observation period. At the 4-hour mark, the surgery, PACU anesthesia, and nursing teams make a multidisciplinary determination about the disposition of the patient to confirm their continued appropriateness for pathway enrollment and discharge to the floor.

An escalation protocol was also defined to outline the criteria by which pathway patients should be transferred to the ICU. These criteria include intraoperative or postoperative seizure, focal postoperative neurological change or new-onset agitation as assessed by the attending clinician, cardiopulmonary instability, and new cardiac dysrhythmia.

Pathway Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We defined rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria for the PACU pathway to select patients with a maximal likelihood of success. Patients were enrolled in the pathway with the approval of the attending neurosurgeon if they were undergoing supratentorial craniotomy for resection of primary or metastatic tumor.

Intraoperative inclusion criteria consisted of a total case length less than 5 hours (defined as the duration between surgery start and end times), estimated blood loss (EBL) less than 500 ml, and routine extubation in the operating room without complication. Continued inclusion in the pathway was contingent on the absence of cardiac dysrhythmia intraoperatively or in the PACU and the maintenance of a postoperative systolic blood pressure less than 150 mm Hg for more than 1 hour without intravenous antihypertensive medications.

At the time of discharge from the PACU, patients were required to be at or near their neurological baseline without new postoperative deficits to proceed with the pathway protocol. Patients who were not at their neurological baseline could also continue with the pathway if permitted by their attending surgeon following neurological evaluation. Specifically, patients with transient postoperative deficits that demonstrated rapid improvement were permitted to stay in the PACU pathway. However, if a deficit was slow to improve or did not improve within the PACU observation period, the patient would be transferred to the ICU for more advanced care and monitoring.

Patients with morbid obesity (BMI > 40) or obesity (BMI > 30) with a history of obstructive sleep apnea or coagulopathy diagnosis or requiring continuous intravenous drips were excluded from pathway enrollment. Other exclusion criteria included the presence of a “difficult” airway as determined by the anesthesia service, the need for nonalbumin blood product transfusion, the presence of an intracranial drain (except for a subgaleal drain), and an intra- or postoperative seizure.

The full protocol for PACU pathway implementation and extended inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the Appendix (an updated version of the initial protocol described in this study).

Data Handling

We included in the pathway adult supratentorial brain tumor resection cases meeting inclusion criteria from the beginning of January 2021 to the end of January 2022. We selected historical control cases from the beginning of January 2020 to the beginning of January 2021. Control cases were also supratentorial brain tumor resections that were under 5 hours in surgical time and had less than 500 ml EBL. Patients were excluded if they had intraoperative seizures or received blood transfusions.

We categorized early surgeries as those starting before noon and late surgeries as those starting after noon. We excluded the LOS values for 2 PACU pathway and 1 control patient who stayed for weeks as inpatients for adjuvant chemotherapy because of insurance and social issues that prevented discharge. Discharge disposition categories included discharge home (with or without home rehabilitation services), discharge to a facility (acute-care rehabilitation hospital, skilled nursing facility, or hospice), and discharge against medical advice. We omitted missing data with pairwise elimination within each analysis.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.1.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Data visualization was performed using the ggplot2 R package (version 3.3.6). We compared medians between pathway and control patients for discrete variables using a two-sided, nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test (alpha = 0.05).

To account for confounding effects on our analysis, we also performed multivariable linear regression using the glm function (base R) to calculate the difference in adjusted means of linear outcomes. Our models included adjustments for the following variables: age, gender, distance from patient’s residence to the hospital, day of the week the procedure was performed (weekday vs weekend), time of procedure start (before noon vs at or after noon), presence of preoperative deficit(s), and total operative time (minutes). We also calculated a 3-day rolling average LOS using the rollmean function in the zoo R package (version 1.8–10). The zip code of each patient’s residence was obtained from their electronic medical record and used as a proxy for residence location for geospatial analysis. We used the zipcodeR package (version 0.3.4) to calculate the distance between each patient’s zip code and the zip code of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

We used Fisher’s exact test (alpha = 0.05) to compare the proportion of patients who were discharged home versus all other discharge dispositions in the PACU pathway and control groups. We also used Fisher’s exact test (alpha = 0.05) to compare the proportion of patients in the PACU pathway and control groups that experienced an emergency department visit or hospital readmission within 30 days of initial discharge.

Ethical Permissions

The study received IRB approval, and all appropriate guidelines were followed.

Results

Demographics

PACU pathway enrollees represented 45.2% of all craniotomy patients during the study period (January 1, 2021, to January 31, 2022). Demographic characteristics were similar between patients in the PACU pathway (n = 202) and control patients (n = 193) who had undergone craniotomy for brain tumor resection (Table 1). The median age of patients in the control cohort was 63.0 years (range 17.0–88.0 years), and that of the PACU pathway patients was 60.5 years (range 21.0–88.0 years; p > 0.05). The proportion of females was similar between the two groups (54.9% vs 52.5%, respectively; p > 0.05). Across all patients, 65.1% carried private insurance, whereas 32.4% were enrolled in Medicare. Most patients in both cohorts (84.7% of PACU patients and 80.8% of controls) were classified as having an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification of III.

TABLE 1.

Summary of characteristics in patients undergoing craniotomy

| Variable | Control Cohort | PACU Pathway Cohort | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 193 | 202 | 395 |

| Age in yrs | |||

| Mean (SD) | 60.4 (15.2) | 58.2 (14.0) | 59.3 (14.6) |

| Median (min, max) | 63.0 (17.0, 88.0) | 60.5 (21.0, 88.0) | 62.0 (17.0, 88.0) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||

| F | 106 (54.9) | 106 (52.5) | 212 (53.7) |

| M | 87 (45.1) | 96 (47.5) | 183 (46.3) |

| ASA class, no. (%) | |||

| II | 12 (6.2) | 16 (7.9) | 28 (7.1) |

| III | 156 (80.8) | 171 (84.7) | 327 (82.8) |

| IV | 24 (12.4) | 15 (7.4) | 39 (9.9) |

| V | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Insurance category, no. (%) | |||

| Private/BCBS insurance | 116 (60.1) | 141 (69.8) | 257 (65.1) |

| Medicare | 73 (37.8) | 55 (27.2) | 128 (32.4) |

| Medicaid | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Self-pay | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 3 (1.6) | 6 (3.0) | 9 (2.3) |

| Pathology, no. (%) | |||

| GBM | 61 (31.6) | 60 (29.7) | 121 (30.6) |

| Meningioma | 25 (13.0) | 32 (15.8) | 57 (14.4) |

| Brain metastasis | 73 (37.8) | 69 (34.2) | 142 (35.9) |

| Other | 34 (17.6) | 41 (20.3) | 75 (19.0) |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BCBS = Blue Cross/Blue Shield; GBM = glioblastoma.

The overall distribution of brain tumor pathologies did not significantly differ between the two cohorts (Table 1). Metastases were the predominant presenting pathology across the study cohort, followed by glioblastoma. Meningiomas comprised 13.0% of the control patient pathology and 15.8% of the pathway patient pathology.

Hospital Course

Of the 202 patients enrolled in the PACU pathway, 7 required escalation to the ICU postoperatively: 4 had postoperative neurological deficits, 2 were transferred because of attending preference, and 1 had postoperative agitation. Age, sex, operative time, and pathology were not associated with the development of new postoperative deficits. One PACU pathway enrollee experienced a postoperative medical complication—deep venous thrombosis (DVT)—compared to 7 historical controls who developed either DVT or a urinary tract infection while in the hospital.

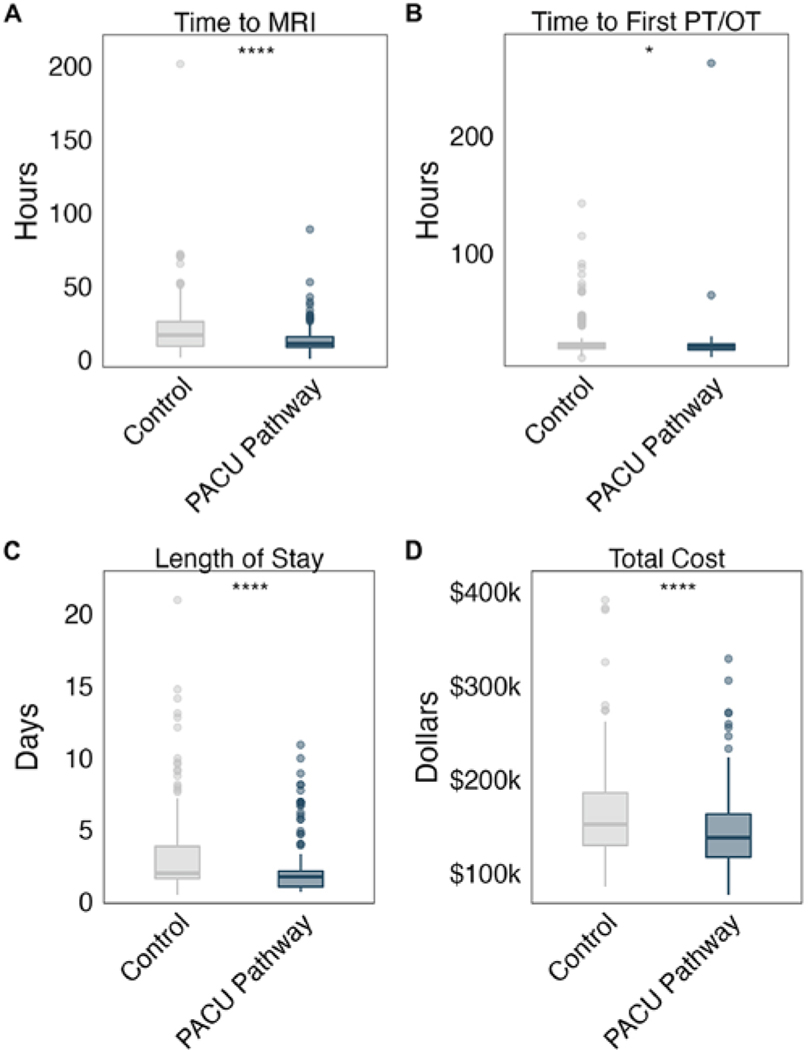

We calculated the median time to first postoperative MRI and time to first inpatient PT and/or OT evaluation for patients in both cohorts. The median time to MRI was 11.0 hours (IQR 8.6–15.6 hours) for PACU pathway patients and 17.0 hours (IQR 9.5–26.0 hours) for historical controls (p < 0.001; Fig. 1A). Time to first postoperative PT and/or OT evaluation was significantly shorter for patients in the PACU pathway than for historical controls (p = 0.046; Fig. 1B). In our adjusted model, PACU pathway patients waited an average of 8.0 hours less to undergo postoperative MRI (p < 0.001) and 3.5 hours less for a postoperative PT and/or OT visit (p = 0.14) compared to control patients (Supplementary Fig. 1A). We next calculated the number of ICU days saved per PACU pathway patient and estimated that pathway enrollment saved 0.95 ICU days per patient (SE ± 0.0016).

FIG. 1.

Boxplots of time to MRI (A), time to first postoperative visit by PT and/or OT (B), LOS (C), and total hospital charges (D) for patients in the PACU pathway versus historical controls. *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001.

LOS was shorter for patients enrolled in the PACU pathway (median 1.7 days, IQR 1.0–2.1 days) compared to control patients (median 2.0 days, IQR 1.6–3.8 days; Fig. 1C). This trend held after adjusting for possible confounding factors; the adjusted LOS for PACU patients was 0.65 days shorter than for historical controls (p = 0.02; Supplementary Fig. 1B). The median hospital charge for pathway patients was $138,044 (IQR $117,350–$163,095), lower by more than $14,000 compared to the median charge for control patients (median $152,109, IQR $129,933–$185,628; p < 0.001; Fig. 1D).

Impact of Operative Start Time on Hospital Course

We classified cases as early if the operative start time was before noon or as late if the operation started after noon. Most cases fell into the late category; only 31% of PACU cases and 21% of control cases had start times before noon. The median LOS was not significantly longer for late PACU pathway cases (1.8 days, IQR 1.0–2.0 days) than for early pathway cases (median 1.2 days, IQR 1.1–2.2 days). Neither were median LOSs significantly different between pathway and control patients who had undergone early craniotomies; the same trend was observed for patients whose craniotomies had started after noon (Fig. 2A).

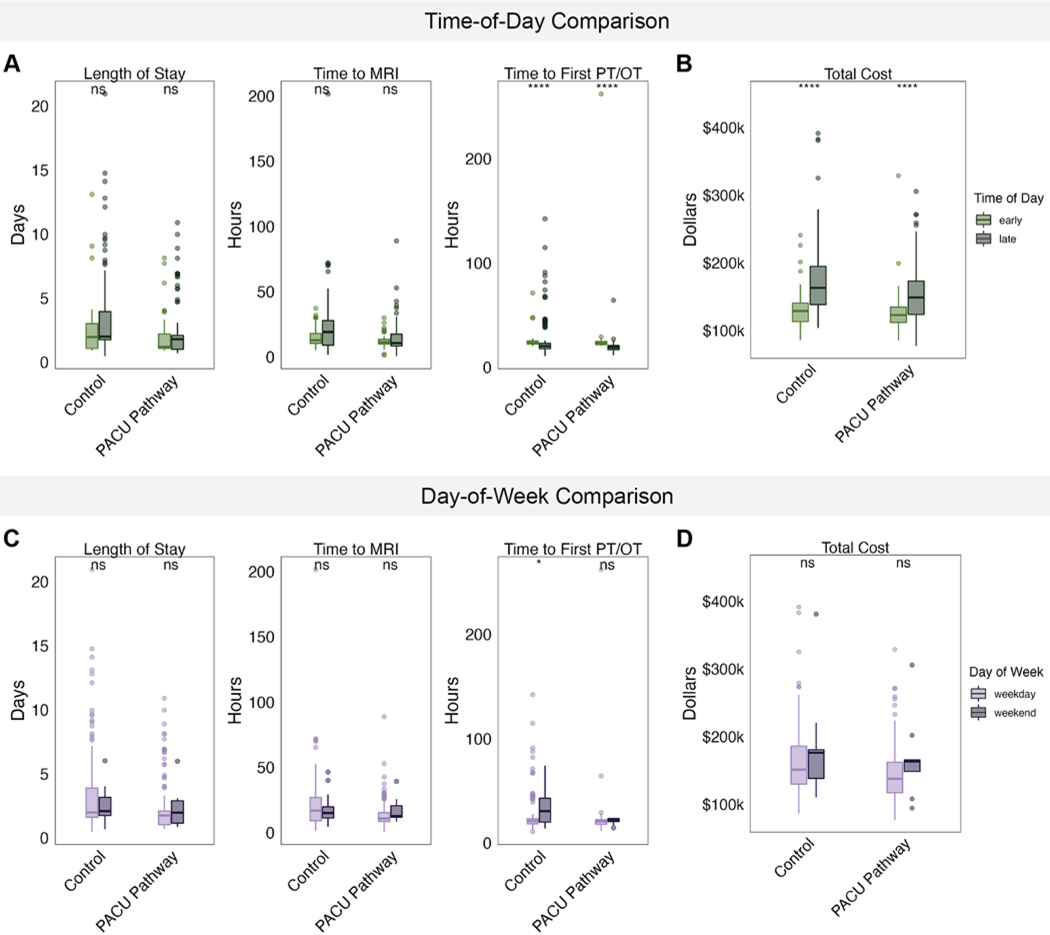

FIG. 2.

A: Boxplots of LOS, time to first postoperative MRI, and time to first postoperative PT and/or OT evaluation for PACU patients and historical controls, separated by operative start time of day. B: Boxplot of total hospital charges for pathway patients and historical controls, separated by operative start time of day. C: Boxplots of LOS, time to first postoperative MRI, and time to first postoperative PT and/or OT evaluation for PACU patients and historical controls, separated by weekday versus weekend operative dates. D: Boxplots of total hospital charges for PACU patients and historical controls, separated by weekday versus weekend operative dates. ns = not significant. *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001.

No significant difference in time to the first MRI or first PT and/or OT visit was identified between PACU patients with early and those with later operative start times (Fig. 2A). The median MRI wait times for pathway patients with early and late craniotomies were shorter than those for control patients in the same time categories, though the differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.67 and p = 0.092, respectively). Similarly, pathway enrollees with late operative start times experienced significantly faster median wait times for a PT and/or OT visit compared to their control counterparts (p = 0.004).

The median total cost for patients with late craniotomies was significantly higher than for patients with early craniotomies within both the PACU and control cohorts (Fig. 2B). The median charge for late PACU patients ($148,944, IQR $123,807–$173,105) was still over $10,000 lower than the median charge for late control patients ($163,031, IQR $138,308–$140,528).

Impact of Operative Day on Hospital Course

We also examined the impact of the day of surgery on patient outcomes. Cases were classified as occurring on a weekday or weekend. Most cases—96% of PACU pathway cases and 89% of control cases—were performed on weekdays. LOS, time to first postoperative MRI, and time to initial PT and/or OT visit did not differ significantly between weekday and weekend craniotomy cases in either cohort (Fig. 2C). Weekend patients incurred higher total costs than weekday patients across both cohorts, although these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 2D).

Relationship Between Patient Proximity to Hospital and Outcomes

We next sought to explore whether the proximity of a patient’s domicile to the hospital was correlated with outcomes. We did not identify a relationship between the distance from the patient primary zip code to our institution and LOS in either the control cohort (R = −0.047, p = 0.52) or the PACU cohort (R = −0.0012, p = 0.99; Supplementary Fig. 2A). Neither did we identify a relationship between distance to the hospital and total cost in either cohort (control R = 0.075, p = 0.31; PACU pathway R = −0.11, p = 0.12; Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Discharge Disposition and Readmission Within 30 Days of Discharge

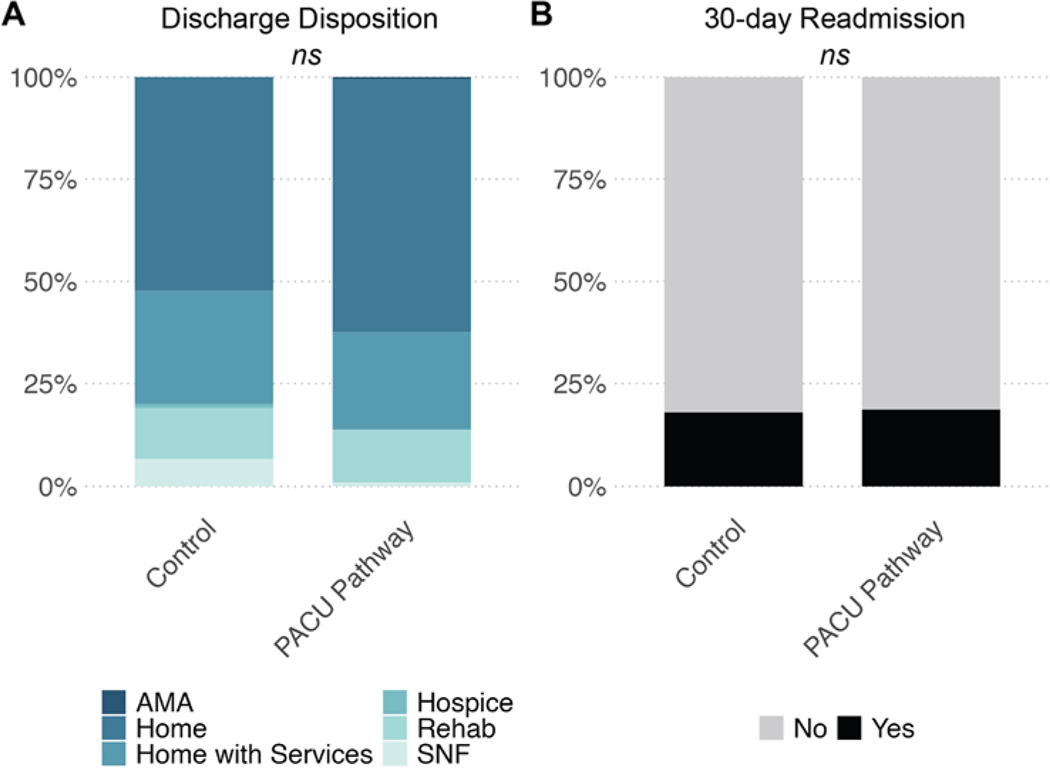

No significant differences in discharge disposition or 30-day readmission were identified in our analysis. Most patients in both groups were discharged to home with or without additional services, that is, 86% of pathway patients compared to 81% of control patients (p = 0.23; Fig. 3A). Nineteen percent of pathway patients had an emergency room visit or hospital readmission within 30 days of initial discharge, compared to 18% of control patients (p = 0.90; Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Discharge disposition (A) and readmission after 30 days of initial discharge (B) in PACU pathway and control cohorts. AMA = discharge against medical advice; SNF = skilled nursing facility.

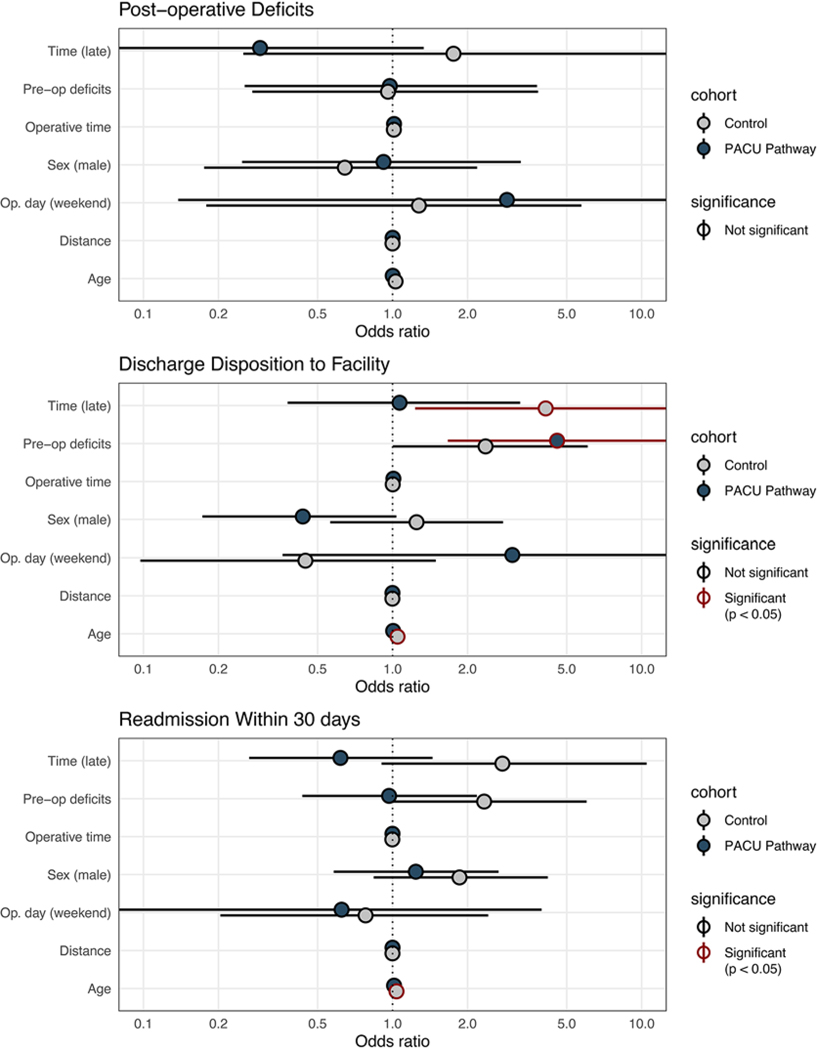

In our adjusted model, the presence of preoperative neurological deficits was significantly associated with the likelihood of being discharged to a rehabilitation center or skilled nursing facility in patients in the PACU cohort (adjusted OR [aOR] 4.57, 95% CI 1.67–14.92) but not the control cohort (Fig. 4). Patient age at the time of surgery (aOR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.07) and a late operative start time (aOR 4.11, 95% CI 1.23–18.98) were significantly associated with discharge to a facility in the control group but not in the PACU pathway cohort.

FIG. 4.

Patient and operative characteristics associated with unfavorable outcomes in PACU pathway and control patients. Significance indicated by red outlining (p < 0.05).

Additional Pathways to Bypass Routine ICU Admission

We identified 11 postoperative protocols for brain tumor patients designed to bypass routine ICU admission, including the one in our study (Table 2). Six protocols were created strictly for supratentorial brain tumor resections, whereas the other pathways variably included craniotomy for microvascular decompression, endoscopic third ventriculostomy, and subdural hematoma. Five protocols included an operative time cutoff and three included an EBL cutoff. Five of the six analyses that focused on LOS demonstrated a reduction in LOS with the studied protocol, and all four studies that measured costs showed a cost reduction. Two pathways incorporated pediatric patients. Two pathways bypassed an overnight stay altogether for a select minority of early-start, short brain tumor resections.7,11

TABLE 2.

Results of selective protocols and care pathways designed to bypass overnight admission to the ICU

| Authors & Year | Methodology | No. of Cases (focus of study) | Pathway Criteria | Protocol | ICU Time Reduction per Patient (days) | LOS Reduction (days) | ICU Admissions/Transfers | Cost Savings per Patient | Pathway Readmission | Comparison Group | Comparison Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study | Retro cohort | 202 (adult brain tumor resection) | Supratentorial craniotomy for brain tumor/SDH, infratentorial craniotomy for CM/MVD, op time <5 hrs, EBL <500 ml | 4-hr obs in PACU w/ neurological checks q hr, then transfer to floor | 0.95 | 0.7 | 3.4% | $13,448 | 19% (30-day, includes ER visits) | Historical controls | Decreased time to MRI, time to PT, LOS, & hospital charges for pathway |

| Vallejo et al., 202211 | Single-surgeon prospective cohort | 37 (adult brain tumor resection) | supratentorial brain tumor <4 cm, op time <3 hrs, EBL <300 ml, start time before 8:30 am | 3-hr obs in PACU, then MRI, then 3-hr ICU monitoring, then PT evaluation, then discharge | - | - | 0.0% (14.0% admitted to floor) | - | 11% | - | - |

| Young et al.,20216 | Case control | 94 (adult brain tumor resection, MVD, & CM) | Age <65 yrs, supratentorial craniotomy for brain tumor <3 cm, infratentorial craniotomy for CM/MVD, case length <6 hrs, EBL <500 ml | 4-hr obs in PACU w/ neurological checks q 2 hrs, then transfer to floor | 1 | 0.25 | 0.0% | $4,000 | 1% (30-day) | Concurrent patients | Decreased LOS & hospital charges for pathway |

| Laan et al., 202027 | Retro cohort | 109 (adult brain tumor resection) | Su supratentorial craniotomy for brain tumor, op time <6 hrs | Routine admission to ward unless surgery >6 hrs or significant cardiopulmonary comorbidities | 0.2 | 1.0 | 24.0% | €1,953 | Historical controls | Decreased ICU LOS, periop complications, & hospital charges for pathway | |

| Mirza et al.,201 828 | Retro cohort | 355 (adult & pediatric brain tumor resection) | Supratentorial craniotomy for intraaxial brain tumor | 2- to 4-hr obs in PACU, then transfer to floor | - | - | 0.1% | - | - | - | - |

| Florman et al., 20175 | Retro cohort | 200 (adult brain tumor resection & biopsy) | Supratentorial craniotomy for brain tumor | 4-hr obs in PACU w/ transfer to floor | - | 4.0 | 2.5% | - | - | Concurrent patients | Decreased LOS & increased likelihood of discharge home for pathway |

| Venkatraghavan et al., 20167 | Single-surgeon retro cohort | 198 (adult brain tumor resection) | Supratentorial craniotomy for brain tumor, op time <4 hrs, caregiver ability overnight w/in 1 hr of hospital | 2-hr obs in PACU, CT scan 4 hrs postop, 2-hr obs in day surgery unit | - | - | 0.0% (11.6% admitted to floor) | - | 3% | - | - |

| Bui et al., 201129 | Retro cohort | 394 (adult brain tumor resection & biopsy, ventriculostomy, & vascular lesion management) | Supra- & infratentorial brain tumor, pituitary tumors, hydrocephalus treated w/ETV | 2- to 3-hr obs in PACU, then 6-hr obs on floor w/ neurological & vital sign checks q hr, then routine floor care | - | 2.9 | 13% (2% planned, 11% unplanned) | - | - | - | - |

| Boulton & Bernstein, 200830 | Single-surgeon retro cohort | 145 (adult brain tumor resection) | Supratentorial craniotomy fo r intraaxial brain tumor | RoRoutine admission to PACU w/ plan for discharge home PODO | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Beauregard & Friedman, 20034 | Single-sugeon retro cohort | 132 (adult brain tumor resection & TN) | Su supra- & infratentorial brain tumor, pituitary tumors, TN | Routine floor admission | - | 3.3 | - | $4,026 | - | Concurrent patients of other attending surgeons | Decreased LOS & hospital charges for pathway |

| Gabel et al.,201631 | Retro cohort | 61 (pediatric brain tumor resection) | Susupra- & infratentorial craniotomy for brain tumor | Routine floor admission | - | - | 9.8% | - | - | - | - |

CM = Chiari malformation; ER = emergency room; ETV = endoscopic third ventriculostomy; MVD = microvascular decompression; obs = observation; POD = postoperative day; q = every; retro = retrospective; SDH = subdural hematoma; TN = trigeminal neuralgia.

Discussion

ICU admission is a resource-intensive step in the postoperative management of cranial neurosurgery patients. There is growing interest in identifying patients who can bypass the ICU in favor of floor management and earlier discharge, but concerns persist regarding the potential negative impact on complication rates, readmissions, and patient experience. In this study, we conducted an analysis of patient hospital courses and outcomes following the implementation of a novel craniotomy-to-floor pathway, or PACU pathway, to better inform those interested in adopting this protocol at their own institutions.

Data Discussion

We identified several key accelerations in the postoperative treatment timeline resulting from PACU pathway enrollment. First, we demonstrated significant reductions in patient LOS that remained robust after adjustment for potential patient- and surgery-level confounders. The benefits conferred by such reductions are manifold. From an institutional perspective, decreasing the average LOS reduces demand for limited hospital resources such as nursing care, inpatient and ICU beds, imaging modalities, and more. Longer hospital durations have also been associated with worse postoperative outcomes and a poorer quality of life after discharge.12

Next, we found that enrollment in the PACU pathway was associated with significantly faster times to the first postoperative MRI. This permitted faster evaluation by the neurosurgery team. Patients also received information about the outcome of their craniotomy more quickly, expediting discharge and scheduling of follow-up care trajectories. Finally, although the association was not statistically significant in our adjusted model, we observed reductions in time to the first postoperative PT and/or OT visit for PACU pathway patients compared to historical controls. Previous efforts have revealed correlations between early mobility and decreased LOSs and hospital-ac quired infections in patients requiring neurointensive care; variable effects on pressure ulcer, deep venous thrombosis, and venous thromboembolism incidences have also been documented.13–15 Earlier assessment by PT and OT teams facilitates planning and goal setting for outpatient care.

Our data support a considerable reduction in total hospital charges following implementation of the PACU pathway. Multivariable analyses of cost differences in craniotomies identified a significant association between a longer LOS and higher costs for brain tumor patients, revealing a mechanism by which our pathway directly contributes to patient savings.16,17 Furthermore, our institution charges approximately $4500 more for an overnight stay in the ICU than on the floor, and patients are more likely to have frequent laboratory work done in the ICU. Earlier PACU-to-floor pathway designs have also demonstrated a nontrivial cost benefit from bypassing ICU admission in elective craniotomy patients (Table 2). The charge reductions resulting from our pathway may promise some financial relief for brain tumor patients, who already shoulder the highest average treatment costs ($100,000 or more) across all cancer patients in the US.18,19

Additionally, no new neurosurgical advance practice providers were required for successful implementation of the PACU pathway protocol or to support its ongoing success at our institution, meaning that additional salary costs do not undercut the financial benefits of the pathway. The burden of advanced practitioner responsibilities falls to the PACU nurses, who are critical care trained and have extensive ICU experience. We found that a one-time 30-minute orientation session with a senior neurosurgeon that covered the key neurological examinations and documentation strategies of the pathway protocol was sufficient training for the PACU nursing team.

One of our most salient findings is the fact that implementation of the PACU pathway saved approximately 0.95 ICU days per patient. While ICU resources are always limited in nature, this savings was particularly important during the peak of the pandemic and the ensuing recovery effort, which has resulted in a higher-than-normal demand for healthcare. Maintaining sufficient ICU bed availability directly impacts outcomes for all patients, not just neurosurgical ones; a reduced ICU bed census has been correlated with increases in morbidity, mortality, and ICU readmission rates for patients with COVID-19, cardiac arrest, and beyond.20–22 ICU bed scarcity also restricts triage decision-making, often resulting in the denial of intensive care for some patients with a significant need or redirection to palliative measures.23–26 As the US continues to grapple with a persistently high demand for healthcare resources and an ever-growing shortage of ICU staffing capacity, methods for maintaining ICU bed availability like ours will become increasingly vital to maintaining patient access to surgical care.

Our study also highlights the noninferiority of the PACU pathway protocol in discharging patients to home and avoiding readmissions and emergency room evaluations within 1 month of discharge. The incidence of new postoperative deficits was equivalent in PACU pathway and control groups, suggesting that surgical complications are not driving the differences we observed in our analysis.

Finally, the distance between a patient’s residence and our institution was not significantly associated with discharge to a facility or readmission within 30 days. The persistence of significant LOS and wait-time decreases in pathway patients despite these disposition difficulties demonstrates the ubiquitous benefit of PACU pathway enrollment. We, therefore, assert that patient distance should not be considered an exclusion criterion for future implementation of our pathway model.

PACU Pathway in Context

We compared 11 studies that have published the results of postoperative pathways designed to bypass ICU admission predominantly after brain tumor resection. While our PACU pathway included nontumor cases, we focused on brain tumor resection in this study since it composed over half of our enrolled cases and was easily standardized for analysis. Our study is the first to demonstrate that dedicated postoperative pathways can reduce the time to MRI following brain tumor resection. We also identified a significant hospital charge reduction and demonstrated that our findings are not related to patient distance from the hospital. We found that our pathway has utility regardless of the day or time of the case.

To understand the subjective experience of both the healthcare team and patients with the PACU pathway, we also informally surveyed all enrolled patients and their nurses during the pilot implementation. Zero negative responses were reported from both patients and nurses, suggesting that the clinical benefits of our pathway do not come at the cost of a worsening quality of patient care. Similarly, as attendings grew more familiar with the PACU pathway, we observed an absolute reduction in enrolled patient transfers to the ICU for monitoring alone.

The success of the PACU pathway prompted us to expand its applications to other neurosurgical indications at our institution. We have now safely enrolled into the PACU pathway patients undergoing supratentorial craniotomy for seizure-focus resection, as well as those undergoing infratentorial craniotomy for microvascular or Chiari decompression (Appendix). We anticipate that these patients will experience the same clinical and economic benefits identified in this study.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Our study design utilized well-matched PACU pathway and control cohorts, facilitating meaningful comparison of outcome measures between the two groups. The diversity of patient ages, pathologies, craniotomy timings, and distances from the hospital represented in our study maximizes the generalizability of our findings to patient demographics likely represented at similar tertiary care centers.

The retrospective design of this study represents the primary limitation of our analysis. While we demonstrated significant, objective LOS and cost benefits in our study, further work should incorporate a more longitudinal financial analysis of patient savings and qualitative study to determine the impact of PACU pathway enrollment on the patient experience.

Conclusions

In this study, we evaluated a novel PACU pathway aimed at decreasing LOS and improving critical care resource utilization in postoperative patients undergoing craniotomy. We found that enrolling patients in our PACU pathway resulted in a faster time to postoperative MRI, faster discharge, and decreased hospital charges without increasing postoperative complications or the likelihood of readmission. The pathway also resulted in the liberation of ICU beds that were then available to critically ill patients. Although these data originate from a single institution, we expect that our results are generalizable and can inform the design and implementation of similar pathways at other tertiary neurosurgery care centers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by award nos. T32GM007753 (S.E.H. and B.M.H.) and T32GM144273 (S.E.H. and B.M.H.) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- DVT

deep venous thrombosis

- EBL

estimated blood loss

- LOS

length of stay

- OT

occupational therapy

- PACU

postanesthesia care unit

- PT

physical therapy

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Bernstock reported an equity position in Treovir LLC, an oHSV clinical stage company, and membership on the POCKiT Diagnostics Board of Scientific Advisors.

Supplemental Information

Online-Only Content

Supplemental material is available with the online version of the article.

Appendix and Supplementary Figures. https://thejns.org/doi/suppl/10.3171/2022.12.JNS222123.

References

- 1.Nitahara JA, Valencia M, Bronstein MA. Medical case management after laminectomy or craniotomy: do all patients benefit from admission to the intensive care unit? Neurosurg Focus. 1998; 5(2): e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Almeida CC, Boone MD, Laviv Y, Kasper BS, Chen CC, Kasper EM. The utility of routine intensive care admission for patients undergoing intracranial neurosurgical procedures: a systematic review. Neurocrit Care. 2018; 28(1): 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanak BW, Walcott BP, Nahed BV, et al. Postoperative intensive care unit requirements after elective craniotomy. World Neurosurg. 2014; 81(1): 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beauregard CL, Friedman WA. Routine use of postoperative ICU care for elective craniotomy: a cost-benefit analysis. Surg Neurol. 2003; 60(6): 483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florman JE, Cushing D, Keller LA, Rughani AI. A protocol for postoperative admission of elective craniotomy patients to a non-ICU or step-down setting. J Neurosurg. 2017; 127(6): 1392–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young JS, Chan AK, Viner JA, et al. A Safe Transitions Pathway for post-craniotomy neurological surgery patients: high-value care that bypasses the intensive care unit. J Neurosurg. 2021; 134(5): 1386–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venkatraghavan L, Bharadwaj S, Au K, Bernstein M, Manninen P. Same-day discharge after craniotomy for supratentorial tumour surgery: a retrospective observational singlecentre study. Can J Anaesth. 2016; 63(11): 1245–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sughrue ME, Bonney PA, Choi L, Teo C. Early discharge after surgery for intra-axial brain tumors. World Neurosurg. 2015; 84(2): 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veilleux R, Senra Costa R, Chalk G, et al. Post-operative craniotomy pathway—PACU to floor pilot. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021; 36(4): e6–e7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnaout O, Patel A, Carter B, Chiocca EA. Letter: Adaptation under fire: two Harvard neurosurgical services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurosurgery. 2020; 87(2): E173–E177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vallejo FA, Eichberg DG, Morell AA, et al. Same-day discharge after brain tumor resection: a prospective pilot study. J Neurooncol. 2022; 157(2): 345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaudino M, Girola F, Piscitelli M, et al. Long-term survival and quality of life of patients with prolonged postoperative intensive care unit stay: unmasking an apparent success. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007; 134(2): 465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Titsworth WL, Hester J, Correia T, et al. The effect of increased mobility on morbidity in the neurointensive care unit. J Neurosurg. 2012; 116(6): 1379–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein K, Mulkey M, Bena JF, Albert NM. Clinical and psychological effects of early mobilization in patients treated in a neurologic ICU: a comparative study. Crit Care Med. 2015; 43(4): 865–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Booth K, Rivet J, Flici R, et al. Progressive mobility protocol reduces venous thromboembolism rate in trauma intensive care patients: a quality improvement project. J Trauma Nurs. 2016; 23(5): 284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zygourakis CC, Liu CY, Yoon S, et al. Analysis of cost variation in craniotomy for tumor using 2 national databases. Neurosurgery. 2017; 81(6): 972–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Missios S, Bekelis K. Drivers of hospitalization cost after craniotomy for tumor resection: creation and validation of a predictive model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015; 15(1): 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goel NJ, Bird CE, Hicks WH, Abdullah KG. Economic implications of the modern treatment paradigm of glioblastoma: an analysis of global cost estimates and their utility for cost assessment. J Med Econ. 2021; 24(1): 1018–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley S, Sherwood PR, Donovan HS, et al. I could lose everything: understanding the cost of a brain tumor. J Neurooncol. 2007; 85(3): 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos AC, de Oliveira SLF, Macedo VLM, et al. Intensive care unit prioritization: the impact of ICU bed availability on mortality in critically ill patients who requested ICU admission in court in a Brazilian cohort. J Crit Care. 2021; 66: 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Town JA, Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Huber MT, Kress JP, Edelson DP. Relationship between ICU bed availability, ICU readmission, and cardiac arrest in the general wards. Crit Care Med. 2014; 42(9): 2037–2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosey MM, Needham DM. Survivorship after COVID-19 ICU stay. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020; 6(1): 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robert R, Coudroy R, Ragot S, et al. Influence of ICU-bed availability on ICU admission decisions. Ann Intensive Care. 2015; 5(1): 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stelfox HT, Hemmelgarn BR, Bagshaw SM, et al. Intensive care unit bed availability and outcomes for hospitalized patients with sudden clinical deterioration. Arch Intern Med. 2012; 172(6): 467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gooch RA, Kahn JM. ICU bed supply, utilization, and health care spending: an example of demand elasticity. JAMA. 2014; 311(6): 567–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinuff T, Kahnamoui K, Cook DJ, Luce JM, Levy MM. Rationing critical care beds: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32(7): 1588–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laan MT, Roelofs S, Van Huet I, Adang EMM, Bartels RHMA. Selective intensive care unit admission after adult supratentorial tumor craniotomy: complications, length of stay, and costs. Neurosurgery. 2020; 86(1): E54–E59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mirza FA, Wang C, Pittman T. Can patients safely be admitted to a ward after craniotomy for resection of intra-axial brain tumors? Br J Neurosurg. 2018; 32(2): 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bui JQH, Mendis RL, van Gelder JM, Sheridan MMP, Wright KM, Jaeger M. Is postoperative intensive care unit admission a prerequisite for elective craniotomy? J Neurosurg. 2011; 115(6): 1236–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boulton M, Bernstein M. Outpatient brain tumor surgery: innovation in surgical neurooncology. J Neurosurg. 2008; 108(4): 649–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabel BC, Martin J, Crawford JR, Levy M. Questioning the need for ICU level of care in pediatric patients following elective uncomplicated craniotomy for brain tumors. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016; 17(5): 564–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.