Abstract

Uterine leiomyoma (LM), also known as uterine fibroids, are common gynecological tumors and can reach a prevalence of 70% among women by the age of 50 years. Notably, the LM burden is much higher in Black women with earlier onset, a greater tumor number, size, and severity compared to White women. Published knowledge shows that there are genetic, environmental, and lifestyle-based risk factors associated with racial disparity for LM. Significant strides have been made on genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic data levels in Black and White women to elucidate the underlying pathomolecular reasons of racial disparity in LM development. However, racial disparity of LM remains a major area of concern in gynecological research. This review highlights risk factors of LM and their role in different races. Furthermore, we discuss the genetics and uterine myometrial microenvironment in LM development. Comparative findings revealed that a major racial difference in the disease is linked to myometrial oxidative burden and altered ROS pathways which is relevant to the oxidized guanine in genomic DNA and MED12 mutations that drive the LM genesis. Considering the burden and morbidity of LM, we anticipate that this review on genetic risk and myometrial microenvironment will strengthen understanding and propel the growth of research to address the racial disparity of LM burden.

Keywords: environment, epigenetics, leiomyoma, MED12, methylation, mutations, myometrium, oxidative stress, racial disparity, transcriptome

Introduction

Uterine leiomyomas (LMs), also known as fibroids, are the most common uterine smooth muscle tumors in reproductive-aged women and affected approximately 226 million women worldwide in 2019 (Global Burden of Disease Collaborator Network, 2020). The estimated incidence of uterine LM is 40–60% among women under the age of 35 years and 70–80% among women over 50 years (HunscHe et al., 2022). Clinically, they are benign monoclonal neoplasms originating from the myometrium of the uterus (Donnez and Dolmans, 2016). LM range in size from a few millimeters to massive growth of 20 cm or more in diameter and up to hundreds of tumors in a single uterus (Williams, 2017; Jayes et al., 2019). About 30% of LM patients show various symptoms that cause significant morbidity, including heavy menstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, anemia, abdominal bloating, and even infertility (Wise and Laughlin-Tommaso, 2016).

LM has significant societal and financial impact associated with medical care as well as a considerable loss in quality of life. Most non-invasive treatment options for LM give temporary relief of symptoms; however, surgical procedures such as hysterectomy or myomectomy are considered the final option to alleviate symptoms and morbidities (Stewart, 2015; Hartmann et al., 2019). LM is the leading cause of approximately 600 000 hysterectomies/myomectomies per year in the USA and the medical cost for treatment of LM including medication, physician visits, and hospital admissions is at least $34.4 billion annually (Catherino et al., 2011; Cardozo et al., 2012).

Racial disparity is observed in LM incidence and severity. Black women are more likely to have earlier onset, more LM, larger tumor size at diagnosis, more severe symptoms (Charifson et al., 2022), and higher rates of surgery for LM than other races (Becker et al., 2005; Yap et al., 2022). Black women tend to have a three times higher rate of myomectomy and a seven times higher hysterectomy rate for LM than White women (Eltoukhi et al., 2014). Currently available federal drug agency (FDA) approved therapies are based on hormonal treatments. Elagolix, and combination therapy with relugolix are the main oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist medicines. These drugs effectively suppress the ovarian sex hormone production and reduce uterine LM-related morbidities including bleeding (Schlaff et al., 2020; Al-Hendy et al., 2021). Given the recognized disparity in LM incidence, the pathological conditions, severity and morbidity, have made investigating in the occurrence, diagnosis, and treatment of this disease difficult (Wang et al., 2020).

Although the exact reason of LM genesis and racial disparity for LM remains largely unknown, recent studies on the global genomic landscape and uterine microenvironment have uncovered important findings related to racial differences in tumor myometrial cells and LM. In this narrative review, we assess and report the current state of knowledge of risk factors behind these disparities and the possible mechanisms of LM genesis. We anticipate that this review article will strengthen understanding and increase research to address the racial disparity in uterine LM.

General risk factors for racial difference in LM

Although the exact mechanism of racial disparity is still unknown, there are several well-established risk factors that are strongly associated with the occurrence and race differences in LM. These factors are categorized into genetic (non-modifiable) and environment/lifestyle (modifiable).

Age

Of the non-modifiable factors, age is the most significant factor for the development of LMs. LM is known as a disease of childbearing age; the risk of being diagnosed with LM is positively correlated with age, peaking at 50 years (Miriello et al., 2021). Genome-causal mediation analysis has identified genetic loci associated with uterine LMs which, importantly, are mediated by age at menarche (Tai et al., 2022). The onset of LM development was observed earlier in Black women than in White women. By 35 years of age, 60% of Black women will have LMs, increasing to 80% by the age of 50 years. Comparatively, in White women, only 40% will have developed LMs by the age of 35 years, with this number jumps to and 70% by the age of 50 years (Baird et al., 2003) (Table 1). LMs do not occur before puberty and the frequency of the disease decreases after menopause (Giannubilo et al., 2015). This is consistent with hormone-driven tumorigenesis for LM development, but what causes racial differences in age-related changes remains largely unknown.

Table 1.

Prevalence of leiomyoma and general risk factors in Black and White women.

| Prevalence (% of population) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Black | White | Reference |

| Leiomyoma presence | |||

| At age 35 years | 60% | 40% | Baird et al., 2003 |

| At age 50 years | 80% | 70% | |

| MED12mut | 79% | 68% | Li et al., 2023 |

| 75% | 66% | He et al., 2022 | |

| Sex hormones and enzymes | |||

| CYP17 A2/A2 | 45% | 15% | Othman and Al-Hendy, 2008 |

| COMT Val/Val | 50% | 19% | Othman and Al-Hendy, 2008 |

| ERα-P/P | 36% | 17% | Al-Hendy and Salama, 2006 |

COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; ERα-PP, estrogen receptor alpha polymorphism.

Genetic and somatic gene alterations

Genetic predisposition is considered as the second leading factor in the development of LM. A family history of LM development is correlated with significantly higher risk for the onset of LM (Van Voorhis et al., 2002). A series of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in different populations have uncovered the differences in the genetic risk of different ancestries and elaborated genetic alterations as risk factors (Table 2, Fig. 1). GWAS was performed in African American (Bray et al., 2017, 2018; Hellwege et al., 2017), Caucasian American (Edwards et al., 2013; Aissani et al., 2015), and Japanese (Sakai et al., 2020), and identified several loci and candidate genes strongly associated with racial differences in LM risk (Table 2). However, the exact mechanism of these genetic variants in LM development remains unclear.

Table 2.

Loci and candidate genes strongly associated with racial differences in Leiomyoma risk in genome-wide association studies.

| Population | Study | No. of patients | No. of controls | Loci | Region | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | Hellwege et al., 2017 | 3399 | 4764 | rs739187 | 22q13.1 | CYTH4 |

| Bray et al., 2018 | 1520 | 5115 | rs57542984 | 5q34 | MAT2B | |

| Bray et al., 2017 | 609 | 5115 | rs12219990 | 10q21.1 | IPMK | |

| Caucasian American | Aissani et al., 2015 | 1018 | 1549 | rs6001794 | 22q13.1 | TNRC6B |

| Edwards et al., 2013 | – | – | rs2280543 | 11p15.5 | BET1L | |

| Japanese | Sakai et al., 2020 | 5720 | 17 492 | rs17033114 | 12q23.2 | LINC00485 |

Figure 1.

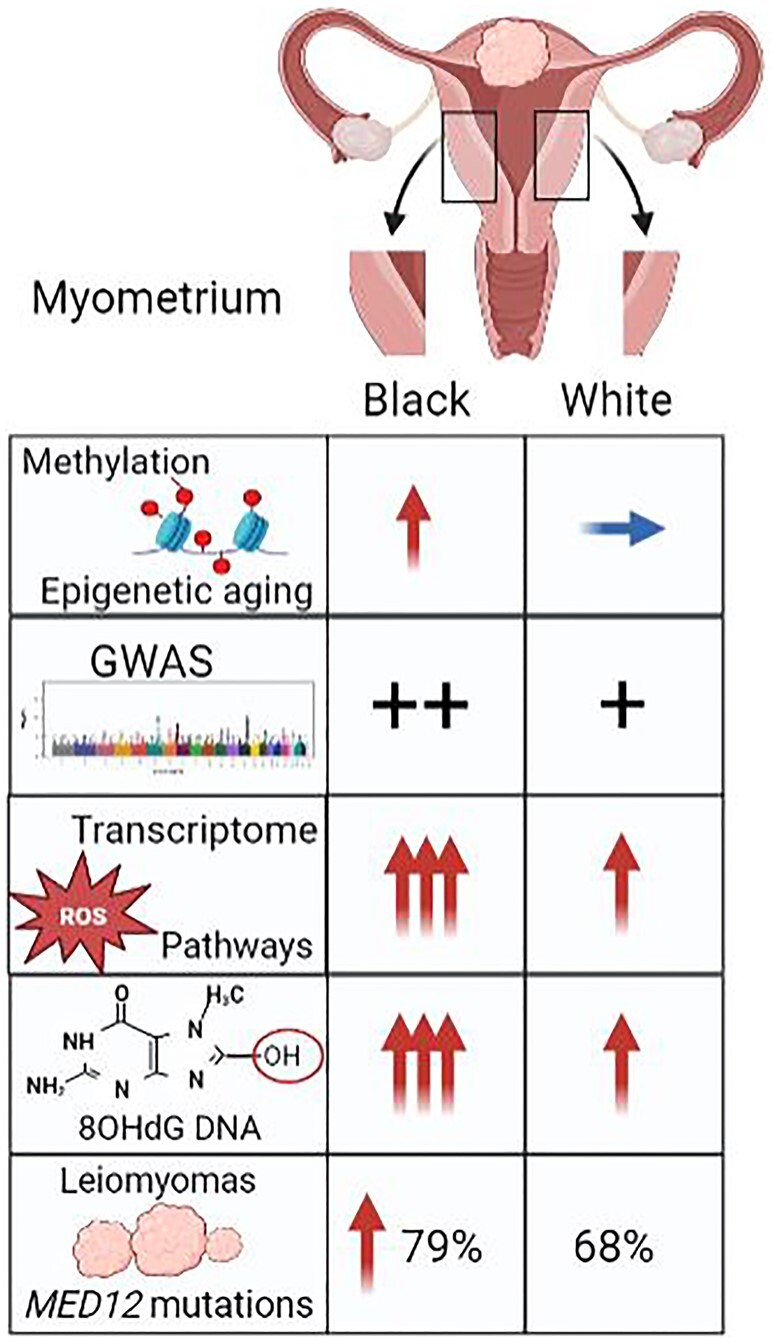

Illustration of racial differences of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors in the myometrium. GWAS, genome wide association study. Red arrow: increased; blue arrow: baseline.

Studies on cytogenetic analyses revealed that 40% of LMs harbor specific chromosomal abnormalities (Sandberg, 2005; Bridge, 2014). In the past decade, a number of studies concluded that single gene alterations were strongly associated with the origin of LM. It has been found that FH biallelic inactivation, MED12, HMGA2, CYPIA, COL4A6, SCRAP subunit, YYPIB1, proto-oncogenes like p27, p53, and signaling pathways (e.g. PI3K-AKT-MTOR) were related to functional alterations involved in LM development (Mäkinen et al., 2011; Mehine et al., 2013; Styer and Rueda, 2016; Berta et al., 2021; Välimäki et al., 2023). Three main mutations, MED12, HMGA2, and FH, can be found in LM tumors, at a rate of 70%, 10%, and 1%, respectively (Mäkinen et al., 2017). The MED12 protein is a component of the complex of 26 subunits that regulate transcription initiation and elongation by bridging regulatory elements in gene promotors to the RNA polymerase II initiation complex (Mäkinen et al., 2011; Bertsch et al., 2014). This protein is known to regulate smooth muscle cell function (Beyer et al., 2007). In cancer studies, mutations in MED12 have been observed in tumors from women of diverse racial and ethnic origins, including those of North American, European, African, Asian, and Middle Eastern descent, with increased frequency in women of African as opposed to non-African descent (Makinen et al., 2011; Sadeghi et al., 2016; Park et al., 2018; He et al., 2022). Regarding uterine fibroid–linked mutations in MED12, all are located within exons 1 or 2, and in particular, occurring more frequently in exon 2 than in exon 1, with the latter accounting for ∼6% of pathogenic alterations reported in uterine LM (Kampjarvi et al., 2014). Most of these mutations are missense with a smaller proportion corresponding to small in-frame deletions and insertions (Li et al., 2022). MED12 mutations drive uterine fibroid-like transcriptional and metabolic programs by a genome-wide chromatin compartmentalization switch (Buyukcelebi et al., 2023) although the molecular basis by which pathogenic mutations in MED12 drive uterine fibroid formation is presently unclear. More importantly, an observable racial difference in LM with MED12 mutations has been reported in association studies (Table 1) (He et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). The molecular basis by which MED12 mutations drive LM formation is under intensive investigation.

Sex hormones

In general, LMs are considered a disease of endocrine disruption. Environmental exposures to endocrine disrupting compounds (EDC) such as phthalates, Bisphenol A (BPA) plasticizers, diethylstilbestrol (DES), genistein (GEN), perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and parabens in personal care products during critical periods of development, increase LM risk by modulating the epigenomic plasticity in progenitor cells and developing tissues (Greathouse et al., 2012; Katz et al., 2016; Bariani et al., 2020).

LM growth is dependent on the ovarian hormones estradiol and progesterone in women (Bulun, 2013; Omar et al., 2019) through their promoting growth factors (Borahay et al., 2015). Population studies from the USA showed that Black women have higher levels of sex hormones than White women (Wise et al., 2004; Assari et al., 2020). A few studies suggest that genetic polymorphisms in sex steroid hormone receptors and their metabolic enzymes are highly relevant to sex steroid hormone functions and racial disparity in LM (Table 1). For example, CYP17 encodes for the cytochrome P450C17α enzyme. This enzyme functions at steroidogenesis and is linked to high levels of serum estradiol. The genotype A2/A2, a polymorphism at 5′URT of CYP17 has been linked to the risk of LM in Black women and large tumor size (Othman and Al-Hendy, 2008). Another estrogen catalyzing enzyme, Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) has a functional genetic polymorphism at codon 158 resulting in a valine to methionine substitution and significantly decreases in enzymatic activity. The genotype of Val/Val in COMT is significantly higher in Black women (50%) than in White women (19%) (Othman and Al-Hendy, 2008). Interestingly, a study showed that estrogen receptor alpha polymorphism (ERα-PP) is significantly correlated with risk of LM in Black women (36%) in comparison to White women (17%) (Al-Hendy and Salama, 2006). The exact relationships between these genes, sex steroid hormones, and LMs remain to be determined.

It is a well-established fact that the level of the sex hormones, estrogen and progesterone are positively associated with LM development through proinflammatory factors (cytokine), growth factors (IGF1, IGF2, TGF-β3, and β-FGF), and cellular apoptosis inhibitors (Manta et al., 2016). Myometrium with LM (MyoF) has a high expression of PR as compared to myometrium without LM (MyoN) (Li et al., 2023). Furthermore, in MyoF, P-4 responsive genes including Bcl2, FOXO1A, SCGB2A2, CYP26a1, and MMP11 exhibit a P4-hyper responsiveness, suggesting that MyoF is primed and at risk for LM transformation (Omar et al., 2019). A study of evaluating progenitor/stem cells exposed to endocrine disrupting compounds (EDC) demonstrates that the inflammatory pathways are activated by enhancing the expression of critical inflammatory-related genes (IRGs) in the myometrial stem cells and myometrium. Those reprogrammed IRGs may result in a hyper-inflammatory phenotype and an increase in hormone-dependent risk of LM as a second hit later in life (Yang et al., 2023).

Myometrium of different races: genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors for LM development

LMs are considered monoclonal neoplasms, derived from a single myometrial cell. The mechanism of neoplastic transition of a myometrial cell into LM is largely unknown. Investigations on the biology of myometrial cells and functional and molecular fingerprints are necessary for understanding their transformation into LM. The human myometrium is the muscular wall of the uterus that is formed by an intricate network of different Müllerian smooth muscle lineages and extracellular matrix dispersed throughout connective tissues of vessels, fibroblasts, and niche of inflammatory cell network (Goad et al., 2022). As a tissue that is poised to regenerate, the myometrium sustains continuous dynamic change—initial expansion during puberty, fluctuating proliferation and apoptosis during cyclic hormonal fluctuations, robust expansion, and terminal differentiation during pregnancy and postpartum involution (Shynlova et al., 2006).

It has been noted that early life adverse environmental exposures can impose serious adult diseases and, more specifically, the female reproductive tract has been deemed a target for developmental programming during early life hormone exposure (Silbergeld and Patrick, 2005; Mas et al., 2017b). Regarding the disparity of myometrial cell transitions to LM, studies showed that Black women have an increased likelihood of experiencing hazardous exposures (during uterus development and in later adulthood) to environmental chemicals such as endocrine disrupting compounds (Greathouse et al., 2012; Katz et al., 2016; Bariani et al., 2020). Other environmental pressures, such as racism and discrimination can also affect personal well-being and health in many ways (Williams and Mohammed, 2009). Studies have shown a positive association between self-reported experiences of racial discrimination and the incidence of uterine LM (Geronimus et al., 2006; Wise et al., 2007; Van Dyke et al., 2020). These findings clearly postulate that environmental exposures and pressures can increase risk of LM development in Black women, but more studies are needed.

Susceptibility of myometrium for LM development

Recent advanced multi-omics approaches on characterizing the molecular genomics profiling of progenitor cells have added insight into the susceptible myometrium. It has been shown that mutational errors in scaffold proteins known as the SRCAP complex lead to abnormal growth of myometrium cells. The SRCAP proteins complex is an important player that controls the replacement of H2A with histone variant H2A.Z in the nucleosome during DNA packing. As a result, these inactivating mutations in SRCAP complex genes lead to a defect in H2A.Z loading that ultimately alters protein expression in the myometrium to drive its neoplastic transformation (Berta et al., 2021). Irrespective of ancestry, a comprehensive study of 728 LM patients and 2263 fresh-frozen tumors with matched myometrium tissues (MyoF) demonstrated that tumors bearing germline mutations in the SRCAP members YEATS4 and ZNHIT1 showed defective deposition of the histone variant H2A.Z. In these tumors, open chromatin emerged at transcription start sites where H2A.Z was lost, which was associated with upregulation of genes. These findings describe myometrial cell transition into LM through an aberrant differentiation program driven by deranged chromatin, emanating from a small number of mutually exclusive driver mutations. Furthermore, these findings open new avenues to determine whether these mutations can be involved in racial disparity in LM incidence (Berta et al., 2021).

Myometrial stem cells for LM development

Several studies link myometrium transition into LM from tissue-specific stem cell divisions and self-renewal (Ono et al., 2013; Mas et al., 2017a; Fernung et al., 2018). In particular, the somatic mutations in myometrial stem cells (MyoSCs) convert them into tumor-initiating cells, leading to LM development. Based on the Eker rat model, the MyoSCs were defined as STRO-1+/CD44+ cells in the myometrium (Mas et al., 2017a). Investigation of a large number of myometrial samples found that the MyoF contained higher numbers of STRO-1+/CD44+ than MyoN (Fernung et al., 2018). Furthermore, the myometrium of Black women had higher STRO-1+/CD44+ MyoSCs than that of White women. They observed a positive correlation of MyoSCs with parity and number of LM, which fluctuated with menstrual cycle hormone changes and age (Fernung et al., 2018). As a key candidate, STRO-1+/CD44+ MyoSCs population may affect the risk for LM development.

Altered DNA methylation in myometrium of different races

Aberrations in gene expression through epigenetic modifications, caused by exposure to environmental factors such as diet, exercise, drugs, and chemicals, have been implicated in the development of many disorders, including LMs (Moosavi and Motevalizadeh Ardekani, 2016). When such influences can be changed, these are termed as modifiable risk factors. It is proposed that physical and environmental stresses in a person’s life can contribute to physical ailments (Forde et al., 2019). Events like economic hardship, psychological stress, alcohol consumption, low physical activity, poor diet, and vitamin D deficiency can erode an individual’s health and have been associated with LM development (Vijayan and Karuna, 2019; Hajhashemi et al., 2019; Tinelli et al., 2021; VanNoy et al., 2021). Altered or dysfunctional hormone levels, oxidative burden, inflammation, and other common stressors on the uterus may impact the rate of genomic instability and result in somatic gene mutations. Certain risk factors including oxidative stress are apparently a higher burden in Black women than in White women. In serum and human umbilical vein endothelial cells culture-based studies, it has been found that Black women have higher oxidative stress as compared to Caucasian women (Feairheller et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2012).

DNA methylation, a heritable epigenetic mark involving the covalent transfer of a methyl group to the C-5 position of the cytosine ring of DNA by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) (Jin et al., 2011), causes alterations in gene expression without altering the sequence. Hypermethylation of the CpG Island in the promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes and genes involved in DNA repair has been associated with gene silencing, causing an increase in genome instability and inducing the growth of tumor cells (Wajed et al., 2001). The discovery of TET1 (ten-eleven translocation protein1) (Tahiliani et al., 2009) led to a series of genome-wide DNA methylation and transcriptional studies uncovering molecular events in human disease. In early studies, DNMT enzymes, responsible for methylation, were shown to be deregulated in LM suggesting that DNA methylation was involved in local changes of DNA (Yamagata et al., 2009). Hypermethylation within promoter regions is usually associated with repression of gene expression, while hypomethylation leads to gene expression. Altered DNA methylation patterns have been implicated in LM (Carbajo‐García et al., 2022). The aberrant patterns of DNA methylation were due to abnormal expression of DNMTs that resulted in the differential expression of associated genes in LM compared to matched myometrium (Li et al., 2003; Włodarczyk et al., 2022). A study has shown the aberrant methylation patterns in LM, and found considerable alterations in promoter methylation, leading to the downregulated expression of various genes, including EFEMP110, WNT2B5, ADH1B4 GATA26, and KLF47 (Mlodawska et al., 2022). Maekawa et al. (2013) identified differential DNA hypomethylation at the promotor regions of collagen-related genes involved in extracellular matrix, in addition to hypermethylation of DAPK1 (death associated protein kinase 1) in the LM compared to matched myometrium, suggesting that DNA methylation can alter gene expression associated with LM development.

Although methylation and epigenetic alterations in LM have been characterized (Yang et al., 2016), a genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in tumor myometrium from both Black and White women was only recently performed. Notably, uteri of Black women were more susceptible to increased altered methylation patterns (Paul et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). The study found remarkable differences in the methylation profiles in the myometrium of Black and White women (Paul et al., 2022). Analysis of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) in the myometrium of Black and White women discovered a significant racial difference of DMR-associated genes, and same findings were present in LM (Paul et al., 2022). In CpG probe analyses, 327 gene-associated probes were shown to be hypomethylated whereas 495 genes were hypermethylated in the myometrium and LM by >10% in Black women compared to White women (Table 3, Fig. 1). Given a high incidence of LM in young Black women (Table 1), an altered methylation profile in the myometrium of Black women strongly suggest a role of epigenomic aging for the risk of LM (Wang et al., 2022). Further analysis revealed that two genes, VWF (Von Willebrand Factor, a blood glycoprotein involved in platelet adhesion) and CD9 (modulates the cell adhesion), at approximately 60 kb upstream of the transcription start sites, were hypomethylated in myometrium from Black women compared to White women (Paul et al., 2022). Overall, these findings shed new light on race-specific patterns of DNA methylation in both LM tissue and the adjacent myometrium.

Table 3.

Molecular differences in myometrium of Black versus White women with leiomyoma.

| Number of genes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Upregulated | Downregulated | Reference |

| Gene expression changed >2-fold | 270 | 374 | Li et al., 2023 |

| 922 | 489 | Paul et al., 2022 | |

| Hypermethylation | Hypomethylation | ||

| Methylation changed >10% | 495 | 327 | Paul et al., 2022 |

| ROS pathway | Oxidized guanine (8-OHdG) | ||

| Oxidative stress | Enriched | Increased | Li et al., 2023 |

| Enriched | Paul et al., 2022 | ||

ROS, reactive oxygen species; 8-OHdG, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine.

Intriguingly, it has been reported that epigenomic DNA methylation can be influenced by exogenous and endogenous factors. Among the exogenous/environmental risk factors, smoking is a common factor which affects both global and gene-specific DNA methylation. In recently published studies, it has been shown that smoking mediates alteration in DNA methylation status and is associated with LM development (Domingo-Relloso et al., 2023; Wesselink et al., 2023). Similarly, alcohol abuse and low physical activity are potent drivers of DNA methylation and in incidence and growth of LM genesis (Föhr et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2023). Epigenetic processes like DNA methylation may underlie associations between air pollution and increased risk of LM with other negative health outcomes (Wesselink et al., 2021; Holliday et al., 2022; Messingschlager et al., 2023).

Likewise, several endogenous risk factors like aging, oxidative stress, inflammation, metabolic disorders, and hormone dysfunction have strong associations with DNA methylation status and onset of tumorigenesis. DNA methylation and aging are linked in a positive manner and are considered the signature of each other (Carlund et al., 2023). Additionally, factors such as chronic inflammation or infection can influence the patterns of DNA methylation in the myometrium and determine the difference in prevalence of LM (Kabodmehri et al., 2022).

Transcriptomic landscaping in myometrium of different races

Transcriptomics has provided an excellent tool to study the functional implications of genetic variability. Race-based clustering of RNA seq data from myometrium and LM (mutant MED12) samples indicated that myometrial samples were significantly associated with race, while LM samples did not correlate with race. This suggests that transformed LM cells gain similar tumor genomic identities in both Black and White tumors, while in the myometrium, there is a clear division of gene expression between the two groups (Paul et al., 2022). A total of 489 genes were downregulated and 922 genes were upregulated in the myometrium of Black compared to White women (Table 3, Fig. 1). In contrast, fewer genes were differentially regulated in the LM of Black and White women (97 genes down and 101 upregulated) (Paul et al., 2022). Gene set enrichment analysis identified 23 LM hallmark pathways (TGFb signaling, Wnt/b-catenin signaling, p53, myogenesis, hypoxia, and reactive oxygen species (ROS)) that were enriched in the myometrium of Black women compared to White women (Table 3). A similar study that compared the transcriptomic profiles of the myometrium of Black and White women with LM found 270 upregulated and 374 downregulated genes differentially expressed between these groups (Table 3). Gene enrichment and gene ontology analysis revealed that the ROS pathway as well as the oxidation–reduction process, organ development, cell adhesion, inflammation, hypoxia, and oxidative phosphorylation pathways were significantly associated with the myometrium of Black women with LM compared to samples from White women with LM (Table 3) (Li et al., 2023).

Taken together, the transcriptomic and DNA methylation profiles of the myometrium of Black versus White women has elucidated important information; the molecular composition of the myometrium was strongly clustered by race in both transcriptome and methylation profiles, as opposed to LM samples which were not. The findings indicated that a progenitor associated with racial disparity begins in the myometrium prior to the development of LM and that racial differences in methylation and transcriptomic patterns in myometrium may determine the fate of LM development.

Oxidative burden in the myometrium for LM development

Oxidative stress plays an important role and is tightly regulated in the uterus of reproductive-aged women (Foksinski et al., 2000; Vidimar et al., 2016; Fletcher et al., 2017; Torres et al., 2018). Studies demonstrate that Black women experience a higher baseline level of endothelial cells and serum oxidative stress than White women both in vitro and in vivo (Feairheller et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2012). Unregulated, increased oxidative stress can increase susceptibility to neoplasia (Zhang et al., 2019). Oxidative stress levels can be impacted by lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, and psychosocial variables. A higher burden of oxidative stress in the myometrium leads to DNA damage and increases proteins associated with oxidative DNA damage and repair (Table 3) (Li et al., 2023). ROS is a product of cell metabolism with important physiological roles, yet when redox homeostasis is disturbed (due to an imbalance between production and neutralization) oxidative stress arises. Importantly, myometrial cells, in response to high oxidative stress, may play a critical role in the risk of LM development.

Role of myometrial ROS in racial disparity for LM

There is a growing body of literature linking ROS to the development of uterine LM. A decreased ability to scavenge superoxide by acetylated manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSODK122Ac) results in oxidative stress (Sies et al., 2017). Clinical findings indicate that serum protein markers of oxidative stress in women with LM are significantly higher compared to women without LM, in addition to correlating with the severity of the disease (Santulli et al., 2013; Vidimar et al., 2016). In line with these findings, high ROS accumulation mediates the oxidation of nucleotides in genomic DNA. In particular, modified guanine 8-OHdG (8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine) (Table 3, Fig. 1) (Sekiguchi and Tsuzuki, 2002; Poetsch, 2020) increases the misrepair rate of 8-OHdG and other modified nucleotides that cause an increase in DNA mutations (Aggarwal et al., 2019). It was reported that 8-OHdG mediated gene mutation in different oncogenes, e.g. K-Ras (controls cell growth, maturation, and death) and p53 (controls cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis), further support the development of ROS-mediated tumors (Olivier et al., 2010; Ziech et al., 2011).

ROS burden may contribute to the MED12 mutation rate, leading to the development of LM (Li et al., 2022, 2023). LMs experience a high level of oxidative stress due in part to ROS-related metabolic defects (Vidimar et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2018). Age-matched myometrial tissues from women with LM have higher immunoreactivity for 8-OHdG compared to myometrial tissues without LM (Li et al., 2022). Age-matched myometrium in Black women with LM have higher detectable levels of 8-OHdG in the genomic DNA than in White women with LM (Li et al., 2022). The expression of proteins associated with oxidative DNA damage and repair, 8-OHdG, 8-oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) were higher in LM and matched myometrium of Black women (Li et al., 2023). Along with increased oxidative stress in the myometrium of Black women there were increases in DNA damage through 8-OHdD formation and misrepair. This is consistent with the findings of a higher rate of MED12 mutations in the LM of Black women versus White women (Li et al., 2022; Buyukcelebi et al., 2023).

ROS-mediated MED12 mutations in racial disparity for LM

In a study of 529 LM samples from different races, MED12 mutations were significantly higher in the LM from Black women (79.7%) than White women (68%) (Li et al., 2022). A meta-analysis containing data from 25 studies indicated that MED12 mutations were more common in Black women (74.5%) than in White women (65.8%) (He et al., 2022) (Table 1, Fig. 1). Insertion, deletion, and point mutations in MED12 all occurred at a higher rate in tumors of Black women (Laganà et al., 2017; Galindo et al., 2018; Griffin et al., 2019; Zyla and Hodgson, 2021). This significantly higher rate of MED12 mutations could provide a potential explanation for the racial disparity observed in LM incidence. Several pathological and clinical studies have investigated the association of genetic mutations in HMGA2 and FH with LM development (Laganà et al., 2017; Galindo et al., 2018; Griffin et al., 2019; Zyla and Hodgson, 2021), however, no noticeable pattern linking race and mutations within these genes to the development of LM has been observed.

DNA damage plays a significant role in mutation, genetic instability, and epigenetic changes. 8-OHdG is the key target of oxidative stress toward DNA damage and is used as a biomarker to measure DNA damage (Asare et al., 2016). These mutations may lead to a mismatch between adenine and guanine (G) and mediate the transversion of regular pairs of adenine and thymidine (A:T), or cytosine and guanine(C:G), which is the hallmark of mutagenicity in LM (Cheng et al., 1992; Ziech et al., 2011). It is imperative to investigate how increased ROS promotes MED12 mutation in myometrial cells through the oxidation of guanine nucleotides, ultimately leading to misrepair. It was shown that Paraquat (PQ), a chemical widely used to stimulate superoxide production in cell culture conditions, caused high DNA oxidation and DNA damage in primary myometrial cells (Xie et al., 2018). The level of γH2AX (histone family member x), detected by immunofluorescent staining, was significantly increased when primary LM cells were treated with PQ (Li et al., 2022) signifying increased DNA damage. PQ-treated myometrial cells induced genes associated with ROS, hypoxia, DNA repair, p53, estrogen response, and AKT signaling pathways (Li et al., 2022). The targeted replacement of guanine with 8-OHdG at MED12 c.130 by CRISPR/cas9 significantly increased the misrepair of G>T, further supporting the notion of oxidized guanine misrepair in target genes (Li et al., 2022). Most significantly, myometrial cells treated with PQ in vitro caused an increase in the rate of MED12 mutations in exon 2 at c.130–131 (Li et al., 2022) which are the mutations that are frequently found in LM. These data showed that ROS can induce DNA damage in the myometrium and can induce MED12 mutations in vitro. As Black women exhibit increased oxidative stress in the myometrium, this correlates with the increased MED12 mutations in LM in vivo.

The consistency of the findings from DNA methylation, transcription, and ROS-based MED12 mutations is exciting because they provide new insight into the disparity in LM development between Black and White women. Further investigations are needed to identify the molecular trigger points where these events are initiated. Current findings demonstrate a key role of ROS and highlights race-specific differences in the myometrial microenvironment.

To date, published data on uterine LMs have been insufficient to elucidate the reasons for racial disparities. However, basic and mechanistic research in recent years has significantly enhanced our understanding of the mechanisms underlying LM development which could be explored in tumors of Black and White women. Furthermore, these findings enable the research community to begin thinking about new and improved diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Specifically, the hormonal dysfunction, MED12 mutation, and oxidative stress emerge as potential target sites for treating or preventing the disease. Undoubtedly, further studies will be needed to develop novel therapeutic tools that can mitigate risk factors and reduce racial disparities in LM genesis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LM can be attributed to a combination of genetic predisposition and epigenetic changes influenced by environmental and lifestyle factors, shaping the epigenomic plasticity of myometrial smooth muscle cells. Racial disparities in LM are evident at the biological level, as seen in marked differences in the transcriptomic and epigenomic profiles of the myometrium derived from Black and White patients with LM. Evidence suggests that elevated ROS may serve as a potential driver of MED12 mutations and LM development. Taking into account both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms associated with LM development and growth.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Serdar Bulun and the leiomyoma biology study team at Northwestern University for their support and scientific discussion. We especially thank Dr Yinuo Li who contributed to the studies of this topic.

Contributor Information

Nazeer H Khan, Department of Pathology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA.

Ross McNally, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA.

J Julie Kim, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA.

Jian-Jun Wei, Department of Pathology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this article.

Authors’ roles

J.-J.W. and J.J.K. performed the study concept; N.H.K. and J.-J.W. wrote the article; R.M. and J.J.K. reviewed and revised the article. All authors read and approved the final article.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA254367).

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest for all authors.

References

- Aggarwal V, Tuli HS, Varol A, Thakral F, Yerer MB, Sak K, Varol M, Jain A, Khan MA, Sethi G. Role of reactive oxygen species in cancer progression: molecular mechanisms and recent advancements. Biomolecules 2019;9:735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aissani B, Zhang K, Wiener H. Evaluation of GWAS candidate susceptibility loci for uterine leiomyoma in the multi-ethnic NIEHS uterine fibroid study. Front Genet 2015;6:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN III, Venturella R, Villarroel C, Critchley HOD, Li Y, McKain L, Arjona Ferreira JC, Langenberg AGM et al. Treatment of uterine fibroid symptoms with relugolix combination therapy. N Engl J Med 2021;384:630–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hendy A, Salama SA. Ethnic distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha polymorphism is associated with a higher prevalence of uterine leiomyomas in Black Americans. Fertil Steril 2006;86:686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asare GA, Akuffo G, Doku D, Asiedu B, Santa S. Dynamics of urinary oxidative stress biomarkers: 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine and 8-isoprostane in uterine leiomyomas. J Mid-Life Health 2016;7:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Boyce S, Bazargan M, Caldwell CH. Race, socioeconomic status, and sex hormones among male and female American adolescents. Reprod Med 2020;1:108–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in Black and White women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bariani MV, Rangaswamy R, Siblini H, Yang Q, Al-Hendy A, Zota AR. The role of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in uterine fibroid pathogenesis. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2020;27:380–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker ER, Spalding J, DuChane J, Horowitz IR. Inpatient surgical treatment patterns for patients with uterine fibroids in the United States, 1998-2002. J Natl Med Assoc 2005;97:1336–1342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berta DG, Kuisma H, Välimäki N, Räisänen M, Jäntti M, Pasanen A, Karhu A, Kaukomaa J, Taira A, Cajuso T et al. Deficient H2A. Z deposition is associated with genesis of uterine leiomyoma. Nature 2021;596:398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch E, Qiang W, Zhang Q, Espona-Fiedler M, Druschitz S, Liu Y, Mittal K, Kong B, Kurita T, Wei J-J. MED12 and HMGA2 mutations: two independent genetic events in uterine leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma. Mod Pathol 2014;27:1144–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer KS, Beauchamp RL, Lee MF, Gusella JF, Naar AM, Ramesh V. Mediator subunit MED28 (Magicin) is a repressor of smooth muscle cell differentiation. J Biol Chem 2007;282:32152–32157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borahay MA, Al-Hendy A, Kilic GS, Boehning D. Signaling pathways in leiomyoma: understanding pathobiology and implications for therapy. Mol Med 2015;21:242–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray MJ, Edwards TL, Wellons MF, Jones SH, Hartmann KE, Velez Edwards DR. Admixture mapping of uterine fibroid size and number in African American women. Fertil Steril 2017;108:1034–1042.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray MJ, Wellons MF, Jones SH, Torstenson ES, Edwards TL, Velez Edwards DR. Transethnic and race-stratified genome-wide association study of fibroid characteristics in African American and European American women. Fertil Steril 2018;110:737–745.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA. The role of cytogenetics and molecular diagnostics in the diagnosis of soft-tissue tumors. Mod Pathol 2014;27(Suppl 1):S80–S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulun SE. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1344–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyukcelebi K, Chen X, Abdula F, Duval A, Ozturk H, Seker-Polat F, Jin Q, Yin P, Feng Y, Wei JJ et al. Engineered MED12 mutations drive uterine fibroid-like transcriptional and metabolic programs by altering the 3D genome compartmentalization. Res Sq 2023;14:4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbajo‐García MC, Corachán A, Juárez‐Barber E, Monleón J, Payá V, Trelis A, Quiñonero A, Pellicer A, Ferrero H. Integrative analysis of the DNA methylome and transcriptome in uterine leiomyoma shows altered regulation of genes involved in metabolism, proliferation, extracellular matrix, and vesicles. J Pathol 2022;257:663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of uterine leiomyomata in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:e211–e219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlund O, Norberg A, Osterman P, Landfors M, Degerman S, Hultdin M. DNA methylation variations and epigenetic aging in telomere biology disorders. Sci Rep 2023;13:7955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catherino WH, Parrott E, Segars J. Proceedings from the national institute of child health and human development conference on the uterine fibroid research update workshop. Fertil Steril 2011;95:9–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha P-C, Takahashi A, Hosono N, Low S-K, Kamatani N, Kubo M, Nakamura Y. A genome-wide association study identifies three loci associated with susceptibility to uterine fibroids. Nat Genet 2011;43:447–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charifson M, Vieira D, Shaw J, Kehoe S, Quinn GP. Why are Black individuals disproportionately burdened with uterine fibroids and how are we examining the disparity? A systematic review. F&S Reviews 2022;3:256–279. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng KC, Cahill DS, Kasai H, Nishimura S, Loeb LA. 8-Hydroxyguanine, an abundant form of oxidative DNA damage, causes GT and AC substitutions. J Biol Chem 1992;267:166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo-Relloso A, Joehanes R, Rodriguez-Hernandez Z, Lahousse L, Haack K, Fallin MD, Herreros-Martinez M, Umans JG, Best LG, Huan T et al. Blood DNA methylation sites, smoking and risk of lung cancer. Environ Pollut 2023;334:122153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnez J, Dolmans M-M. Uterine fibroid management: from the present to the future. Hum Reprod Update 2016;22:665–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards TL, Michels KA, Hartmann KE, Velez Edwards DR. BET1L and TNRC6B associate with uterine fibroid risk among European Americans. Hum Genet 2013;132:943–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltoukhi HM, Modi MN, Weston M, Armstrong AY, Stewart EA. The health disparities of uterine fibroid tumors for African American women: a public health issue. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:194–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feairheller DL, Park JY, Sturgeon KM, Williamson ST, Diaz KM, Veerabhadrappa P, Brown MD. Racial differences in oxidative stress and inflammation: in vitro and in vivo. Clin Transl Sci 2011;4:32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernung LEP, Jones K, Mas A, Kleven D, Waller JL, Al-Hendy A. Expanding upon the human myometrial stem cell hypothesis and the role of race, hormones, age, and parity in a profibroid environment. Am J Pathol 2018;188:2293–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher NM, Abusamaan MS, Memaj I, Saed MG, Al-Hendy A, Diamond MP, Saed GM. Oxidative stress: a key regulator of leiomyoma cell survival. Fertil Steril 2017;107:1387–1394.e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Föhr T, Waller K, Viljanen A, Rantanen T, Kaprio J, Ollikainen M, Sillanpää E. Mortality associations with DNA methylation-based biological aging and physical functioning measures across a 20-year follow-up period. J Gerontol 2023;78:1489–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foksinski M, Kotzbach R, Szymanski W, Olinski R. The level of typical biomarker of oxidative stress 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine is higher in uterine myomas than in control tissues and correlates with the size of the tumor. Free Radic Biol Med 2000;29:597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde AT, Crookes DM, Suglia SF, Demmer RT. The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol 2019;33:1–18.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo LJ, Hernández-Beeftink T, Salas A, Jung Y, Reyes R, de Oca FM, Hernández M, Almeida TA. HMGA2 and MED12 alterations frequently co-occur in uterine leiomyomas. Gynecol Oncol 2018;150:562–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. Am J Public Health 2006;96:826–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannubilo SR, Ciavattini A, Petraglia F, Castellucci M, Ciarmela P. Management of fibroids in perimenopausal women. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2015;27:416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborator Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME; ), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goad J, Rudolph J, Zandigohar M, Tae M, Dai Y, Wei JJ, Bulun SE, Chakravarti D, Rajkovic A. Single-cell sequencing reveals novel cellular heterogeneity in uterine leiomyomas. Hum Reprod 2022;37:2334–2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greathouse KL, Bredfeldt T, Everitt JI, Lin K, Berry T, Kannan K, Mittelstadt ML, Ho S-M, Walker CL. Environmental estrogens differentially engage the histone methyltransferase EZH2 to increase risk of uterine tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer Res 2012;10:546–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin BB, Ban Y, Lu X, Wei J-J. Hydropic leiomyoma: a distinct variant of leiomyoma closely related to HMGA2 overexpression. Hum Pathol 2019;84:164–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajhashemi M, Ansari M, Haghollahi F, Eslami B. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on the size of uterine leiomyoma in women with vitamin D deficiency. Caspian J Intern Med 2019;10:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann KE, Fonnesbeck C, Surawicz T, Krishnaswami S, Andrews JC, Wilson JE, Velez-Edwards D, Kugley S, Sathe NA. Management of Uterine Fibroids. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2017 Dec. Report No.: 17(18)-EHC028-EF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Nelson W, Li H, Xu YD, Dai XJ, Wang YX, Ding YB, Li YP, Li T. Frequency of MED12 mutation in relation to tumor and patient’s clinical characteristics: a meta-analysis. Reprod Sci 2022;29:357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwege JN, Jeff JM, Wise LA, Gallagher CS, Wellons M, Hartmann KE, Jones SF, Torstenson ES, Dickinson S, Ruiz-Narvaez EA et al. A multi-stage genome-wide association study of uterine fibroids in African Americans. Hum Genet 2017;136:1363–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday KM, Gondalia R, Baldassari A, Justice AE, Stewart JD, Liao D, Yanosky JD, Jordahl KM, Bhatti P, Assimes TL et al. Gaseous air pollutants and DNA methylation in a methylome-wide association study of an ethnically and environmentally diverse population of US adults. Environ Res 2022;212:113360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsche E, Rakov V, Scippa K, Witherspoon B, McKain L. The burden of uterine fibroids from the perspective of US women participating in open-ended interviews. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle) 2022;3:286–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayes FL, Liu B, Feng L, Aviles-Espinoza N, Leikin S, Leppert PC. Evidence of biomechanical and collagen heterogeneity in uterine fibroids. PLoS One 2019;14:e0215646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin B, Li Y, Robertson KD. DNA methylation: superior or subordinate in the epigenetic hierarchy? Genes Cancer 2011;2:607–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabodmehri R, Etezadi A, Sharami SH, Ghanaei MM, Hosseinzadeh F, Heirati SFD, Pourhabibi Z. The association between chronic endometritis and uterine fibroids. J Family Med Prim Care 2022;11:653–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampjarvi K, Park MJ, Mehine M, Kim NH, Clark AD, Butzow R, Bohling T, Bohm J, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen H et al. Mutations in Exon 1 highlight the role of MED12 in uterine leiomyomas. Hum Mutat 2014;35:1136–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz TA, Yang Q, Treviño LS, Walker CL, Al-Hendy A. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril 2016;106:967–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganà AS, Vergara D, Favilli A, La Rosa VL, Tinelli A, Gerli S, Noventa M, Vitagliano A, Triolo O, Rapisarda AMC et al. Epigenetic and genetic landscape of uterine leiomyomas: a current view over a common gynecological disease. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2017;296:855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Chiang T-C, Richard-Davis G, Barrett JC, Mclachlan JA. DNA hypomethylation and imbalanced expression of DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1, 3A, and 3B) in human uterine leiomyoma. Gynecol Oncol 2003;90:123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, McNally RP, Feng Y, Kim JJ, Wei J-J. Racial differences in transcriptomics and reactive oxygen species burden in myometrium and leiomyoma. Hum Reprod 2023;38:609–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Xu X, Asif H, Feng Y, Kohrn BF, Kennedy SR, Kim JJ, Wei J-J. Myometrial oxidative stress drives MED12 mutations in leiomyoma. Cell Biosci 2022;12:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa R, Sato S, Yamagata Y, Asada H, Tamura I, Lee L, Okada M, Tamura H, Takaki E, Nakai A et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis reveals a potential mechanism for the pathogenesis and development of uterine leiomyomas. PLoS One 2013;8:e66632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makinen N, Heinonen HR, Moore S, Tomlinson IP, van der Spuy ZM, Aaltonen LA. MED12 exon 2 mutations are common in uterine leiomyomas from South African patients. Oncotarget 2011;2:966–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen N, Kämpjärvi K, Frizzell N, Bützow R, Vahteristo P. Characterization of MED12, HMGA2, and FH alterations reveals molecular variability in uterine smooth muscle tumors. Mol Cancer 2017;16:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen N, Mehine M, Tolvanen J, Kaasinen E, Li Y, Lehtonen HJ, Gentile M, Yan J, Enge M, Taipale M et al. MED12, the mediator complex subunit 12 gene, is mutated at high frequency in uterine leiomyomas. Science 2011;334:252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manta L, Suciu N, Toader O, Purcărea R, Constantin A, Popa F. The etiopathogenesis of uterine fibromatosis. J Med Life 2016;9:39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas A, Prusinski L, Yang Q, Diaz-Gimeno P, Stone L, Diamond MP, Simon C, Al-Hendy A. Role of Stro1+/CD44+ stem cells in myometrial physiology and uterine remodeling during pregnancy. Biol Reprod 2017a;96:70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas A, Stone L, O’Connor PM, Yang Q, Kleven D, Simon C, Walker CL, Al-Hendy A. Developmental exposure to endocrine disruptors expands murine myometrial stem cell compartment as a prerequisite to leiomyoma tumorigenesis. Stem Cells 2017b;35:666–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehine M, Kaasinen E, Mäkinen N, Katainen R, Kämpjärvi K, Pitkänen E, Heinonen H-R, Bützow R, Kilpivaara O, Kuosmanen A et al. Characterization of uterine leiomyomas by whole-genome sequencing. N Engl J Med 2013;369:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messingschlager M, Bartel-Steinbach M, Mackowiak SD, Denkena J, Bieg M, Klös M, Seegebarth A, Straff W, Süring K, Ishaque N et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation sequencing identifies epigenetic perturbations in the upper airways under long-term exposure to moderate levels of ambient air pollution. Environ Res 2023;233:116413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miriello D, Galanti F, Cignini P, Antonaci D, Schiavi M, Rago R. Uterine fibroids treatment: do we have new valid alternative? Experiencing the combination of vitamin D plus epigallocatechin gallate in childbearing age affected women. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021;25:2843–2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlodawska OW, Saini P, Parker JB, Wei J-J, Bulun SE, Simon MA, Chakravarti D. Epigenomic and enhancer dysregulation in uterine leiomyomas. Hum Reprod Update 2022;28:518–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi A, Motevalizadeh Ardekani A. Role of epigenetics in biology and human diseases. Iran Biomed J 2016;20:246–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AA, Zhao L, Patel RS, Jones DP, Ahmed Y, Stoyanova N, Gibbons GH, Vaccarino V, Din-Dzietham R, Quyyumi AA. Differences in systemic oxidative stress based on race and the metabolic syndrome: the Morehouse and Emory Team up to Eliminate Health Disparities (META-Health) study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2012;10:252–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010;2:a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omar M, Laknaur A, Al-Hendy A, Yang Q. Myometrial progesterone hyper-responsiveness associated with increased risk of human uterine fibroids. BMC Womens Health 2019;19:92–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Yin P, Navarro A, Moravek MB, Coon JSt, Druschitz SA, Serna VA, Qiang W, Brooks DC, Malpani SS et al. Paracrine activation of WNT/beta-catenin pathway in uterine leiomyoma stem cells promotes tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:17053–17058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Othman EE, Al-Hendy A. Molecular genetics and racial disparities of uterine leiomyomas. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2008;22:589–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MJ, Shen H, Kim NH, Gao F, Failor C, Knudtson JF, McLaughlin J, Halder SK, Heikkinen TA, Vahteristo P et al. Mediator kinase disruption in MED12-mutant uterine fibroids from hispanic women of South Texas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103:4283–4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul EN, Grey JA, Carpenter TJ, Madaj ZB, Lau KH, Givan SA, Burns GW, Chandler RL, Wegienka GR, Shen H et al. Transcriptome and DNA methylome analyses reveal underlying mechanisms for the racial disparity in uterine fibroids. JCI Insight 2022;7:e160274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poetsch AR. The genomics of oxidative DNA damage, repair, and resulting mutagenesis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2020;18:207–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi S, Khorrami M, Amin-Beidokhti M, Abbasi M, Kamalian Z, Irani S, Omrani M, Azmoodeh O, Mirfakhraie R. The study of MED12 gene mutations in uterine leiomyomas from Iranian patients. Tumour Biol 2016;37:1567–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, Tanikawa C, Hirasawa A, Chiyoda T, Yamagami W, Kataoka F, Susumu N, Terao C, Kamatani Y, Takahashi A et al. Identification of a novel uterine leiomyoma GWAS locus in a Japanese population. Sci Rep 2020;10:1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg AA. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft tissue tumors: leiomyoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2005;158:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santulli P, Borghese B, Lemaréchal H, Leconte M, Millischer A-E, Batteux F, Chapron C, Borderie D. Increased serum oxidative stress markers in women with uterine leiomyoma. PLoS One 2013;8:e72069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaff WD, Ackerman RT, Al-Hendy A, Archer DF, Barnhart KT, Bradley LD, Carr BR, Feinberg EC, Hurtado SM, Kim J et al. Elagolix for heavy menstrual bleeding in women with uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med 2020;382:328–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi M, Tsuzuki T. Oxidative nucleotide damage: consequences and prevention. Oncogene 2002;21:8895–8904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shynlova O, Oldenhof A, Dorogin A, Xu Q, Mu J, Nashman N, Lye SJ. Myometrial apoptosis: activation of the caspase cascade in the pregnant rat myometrium at midgestation. Biol Reprod 2006;74:839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sies H, Berndt C, Jones DP. Oxidative stress. Annu Rev Biochem 2017;86:715–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld EK, Patrick TE. Environmental exposures, toxicologic mechanisms, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:S11–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA. Clinical practice. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1646–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styer AK, Rueda BR. The epidemiology and genetics of uterine leiomyoma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2016;34:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science 2009;324:930–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai A-S, Lin R-T, Lin Y-C, Wang C-H, Lin S-H, Imoto S. Genome-wide causal mediation analysis identifies genetic loci associated with uterine fibroids mediated by age at menarche. Hum Reprod 2022;37:2197–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinelli A, Vinciguerra M, Malvasi A, Andjić M, Babović I, Sparić R. Uterine fibroids and diet. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres MJ, Kew KA, Ryan TE, Pennington ER, Lin CT, Buddo KA, Fix AM, Smith CA, Gilliam LA, Karvinen S et al. 17beta-estradiol directly lowers mitochondrial membrane microviscosity and improves bioenergetic function in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab 2018;27:167–179.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Välimäki N, Jokinen V, Cajuso T, Kuisma H, Taira A, Dagnaud O, Ilves S, Kaukomaa J, Pasanen A, Palin K et al. Inherited mutations affecting the SRCAP complex are central in moderate-penetrance predisposition to uterine leiomyomas. Am J Hum Genet 2023;110:460–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke ME, Baumhofer NK, Slopen N, Mujahid MS, Clark CR, Williams DR, Lewis TT. Pervasive discrimination and allostatic load in African American and White Adults. Psychosom Med 2020;82:316–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhis BJ, Romitti PA, Jones MP. Family history as a risk factor for development of uterine leiomyomas. Results of a pilot study. J Reprod Med 2002;47:663–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanNoy BN, Bowleg L, Marfori C, Moawad G, Zota AR. Black women’s psychosocial experiences with seeking surgical treatment for uterine fibroids: implications for clinical practice. Womens Health Issues 2021;31:263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidimar V, Gius D, Chakravarti D, Bulun SE, Wei J-J, Kim JJ. Dysfunctional MnSOD leads to redox dysregulation and activation of prosurvival AKT signaling in uterine leiomyomas. Sci Adv 2016;2:e1601132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan U, Karuna MS. An overview on the multitude of factors promoting and symptoms associated with the incidence of uterine Leiomyoma among women of reproductive years. IJBAR 2019;9:345–353.

- Wajed SA, Laird PW, DeMeester TR. DNA methylation: an alternative pathway to cancer. Ann Surg 2001;234:10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Liu H, Hu Q, Wang L, Liu J, Zheng Z, Zhang W, Ren J, Zhu F, Liu GH. Epigenetic regulation of aging: implications for interventions of aging and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022;7:374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Li S, Zhang Z, Jia J, Shan B. Prevalence and occult rates of uterine leiomyosarcoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e21766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesselink AK, Rosenberg L, Wise LA, Jerrett M, Coogan PF. A prospective cohort study of ambient air pollution exposure and risk of uterine leiomyomata. Hum Reprod 2021;36:2321–2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesselink AK, Wegienka G, Coleman CM, Geller RJ, Harmon QE, Upson K, Lovett SM, Claus Henn B, Marsh EE, Noel NL et al. A prospective ultrasound study of cigarette smoking and uterine leiomyomata incidence and growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023;229:151.e1–151.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR. Uterine fibroids–what’s new? F1000Res 2017;6:2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 2009;32:20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise LA, Laughlin-Tommaso SK. Epidemiology of uterine fibroids–from menarche to menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2016;59:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise LA, Palmer JR, Cozier YC, Hunt MO, Stewart EA, Rosenberg L. Perceived racial discrimination and risk of uterine leiomyomata. Epidemiology 2007;18:747–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise LA, Palmer JR, Harlow BL, Spiegelman D, Stewart EA, Adams-Campbell LL, Rosenberg L. Reproductive factors, hormonal contraception, and risk of uterine leiomyomata in African-American women: a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Włodarczyk M, Nowicka G, Ciebiera M, Ali M, Yang Q, Al-Hendy A. Epigenetic regulation in uterine fibroids—the role of ten-eleven translocation enzymes and their potential therapeutic application. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Xu X, Yin P, Li Y, Guo H, Kujawa S, Chakravarti D, Bulun S, Kim JJ, Wei J-J. Application of ex-vivo spheroid model system for the analysis of senescence and senolytic phenotypes in uterine leiomyoma. Lab Invest 2018;98:1575–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata Y, Maekawa R, Asada H, Taketani T, Tamura I, Tamura H, Ogane J, Hattori N, Shiota K, Sugino N. Aberrant DNA methylation status in human uterine leiomyoma. Mol Hum Reprod 2009;15:259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Ali M, Treviño LS, Mas A, Ismail N, Al-Hendy A. Epigenetic modulation of inflammatory pathways in myometrial stem cells and risk of uterine fibroids. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:11641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Mas A, Diamond MP, Al-Hendy A. The mechanism and function of epigenetics in uterine leiomyoma development. Reprod Sci 2016;23:163–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap VL, Mogana R, Dharmendra K, Abdullah M, Selvaraja M. Latest evidence in the pathogenesis of uterine fibroids. Curr Trends Biotechnol Pharm 2022;16:260–287. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Ye ZW, Townsend DM, Hughes-Halbert C, Tew KD. Racial disparities, cancer and response to oxidative stress. Adv Cancer Res 2019;144:343–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Q, Wang H, Yan A, Yin F, Qiao X. DNA methylation in alcohol use disorder. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:10130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziech D, Franco R, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)––induced genetic and epigenetic alterations in human carcinogenesis. Mutat Res 2011;711:167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zyla RE, Hodgson A. Gene of the month: FH. J Clin Pathol 2021;74:615–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this article.