Abstract

Background/Aim

A genomic analysis based on next-generation sequencing is important for deciding cancer treatment strategies. Cancer tissue sometimes displays intratumor heterogeneity and a pathologic specimen may contain more than two tumor grades. Although tumor grades are very important for the cancer prognosis, the impact of higher tumor grade distribution in a specimen used for a genomic analysis is unknown.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the data of 61 clear cell carcinoma and 46 prostate cancer patients that were diagnosed between December 2018 and August 2022 using the GeneRead Human Comprehensive Cancer Panel or SureSelect PrePool custom Tier2. Genome annotation and curation were performed using the GenomeJack software.

Results

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was increased in proportion to the higher tumor grade distribution in grade 2 clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). In PC, Grade Group 3/4 specimens that included an increased distribution of Gleason pattern 4 had more frequent gene mutations.

Conclusion

Our results suggest the importance of selecting the maximum distribution of higher tumor grade areas to obtain results on the precise gene alterations for genomics-focused treatments.

Keywords: Tumor grade distribution, genetic alteration, cancer panel test, intratumor heterogeneity

Despite recent advances in cancer treatment, advanced cancers are still incurable. Gene mutations in cancer are promising treatment targets (1,2); thus, the precise detection of genetic alterations gives cancer patients a greater chance to receive genomics-focused treatment. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have played an important role in the detection of the genetic alterations of cancer (3). Clinically used cancer panel tests based on NGS are performed starting with DNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections or with circulating cell-free DNA extracted from blood (1,4). In samples with <20% tumor cells in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections, the sensitivity in the detection of copy number alterations (CNAs) or mutations may decrease (5,6). The targeting of the area of the section to be used as the specimen for DNA extraction is usually determined by pathologists in order to maximize tumor cell content. Meanwhile, tumor grade, which is mostly defined by the structure and cytological features including nuclear or morphological atypia, is one of strongest predictive factors in many cancers. Although, pathologically high-grade cancer, which shows an aggressive nature with increased genomic instability and mutations (7-10), is likely to show more genetic alterations, the relationship of the area of high-grade tumor distribution in specimens and genetic alterations has not been studied.

In clear cell or papillary renal cell carcinoma (RCC), tumor grading based on nuclear atypia (grades 1-3), and with features of extreme nuclear pleomorphism, multinucleated giant cells, and/or rhabdoid and/or sarcomatoid differentiation (grade 4) is widely used in the World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology (WHO/ISUP) grading system (11). In the grading system, the highest tumor grade is assigned when more than one of the grading features exists in a tumor. Mutational heterogeneity, with the exception of VHL, among different regional tumor grades of clear cell RCC (ccRCC) has been reported (12). On the other hand, Ball et al. reported no association between the Fuhrman grade–which is defined by the traditionally employed RCC grading system–and mutational change (7).

The Gleason score has been used to predict the prognosis of prostate cancer (PC) (11,13). The Gleason score is calculated as the sum of the two most prevalent Gleason patterns, which are defined by morphological atypia (glandular architecture and microscopic appearance). The Gleason score system has been refined with the establishment of the PC grade group (GG) (11). Prostate cancer with Gleason score ≤6, 3+4, 4+3, 8, and 9-10 are categorized to GG 1, 2, 3 ,4 and 5, respectively. Some genetic alterations, including mutations in DNA repair genes, are associated with advanced stage and higher Gleason grade in PC (8,9,14).

In this context, it seems natural to select samples with the area that shows the maximum distribution of the highest tumor grade because tumor heterogeneity is often observed in many cancers (15-17). Many studies using different samples from individual patients demonstrated that a high tumor grade was associated with increased genomic alterations; however, the impact of intra-tumor grade distribution in the pathological specimen on genetic alterations has not been elucidated. In this study we hypothesized that increased distribution of the higher tumor grade in urologic cancer specimens would affect the detection of genetic alterations.

Patients and Methods

Patients and samples. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Central Japan International Medical Center (No.2022-44). Each patient had provided written informed consent. This retrospective study was conducted by reviewing the data of ccRCC and PC patients who underwent surgery or biopsy followed by a genome profiling test between December 2018 and August 2022. The tumor grades of ccRCC and PC were diagnosed based on the 2016 WHO/ISUP grading system. Patients pre-treated before surgery or biopsy were excluded from this analysis.

DNA isolation and next-generation sequencing-based multiplex gene assay. Prior to DNA extraction, pathologists investigated the tissue tumor cell content on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides. At the time, the distribution of each tumor grade was not considered. The area that predominantly included tumor cells was then macro-dissected from 10-μm-thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections. DNA was extracted using Maxwell RSC DNA FFPE Kit-PKK, Custom (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA). A multiplex gene assay based on NGS was reported previously (18,19). After quantification of purified DNA using an Agilent 4200 TapeStation, DNA libraries were prepared with DNA (DNA integrity number >3.1) for subsequent genomic sequencing. From December 2018 to December 2021, gene amplification was performed using a GeneRead Human Comprehensive Cancer Panel (160 genes; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). From January 2022 to August 2022, it was performed using SureSelect PrePool custom Tier2 (143 genes; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Targeted amplicon exome sequencing for cancer-related genes was performed using the Illumina Miseq sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Genome annotation and curation was performed using GenomeJack (Mitsubishi Space Software, Tokyo, Japan) (20,21). Based on this platform, high scoring (≥2.0) gene mutations were noted as actionable gene mutations. Since two different panels were used, the common target gene mutations in the panels were analyzed in this study.

Statistical analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the Graph Pad Prism software program (version 7.03, Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Comparisons among the three groups were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared test. p-Values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

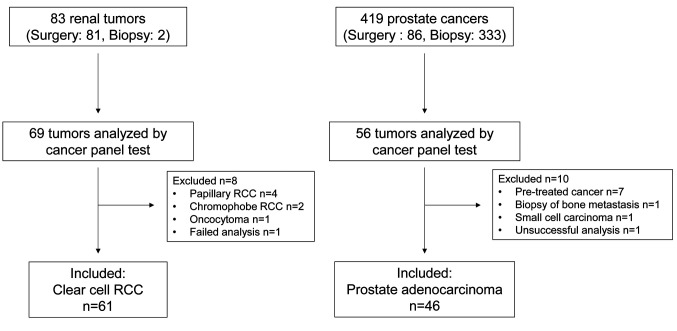

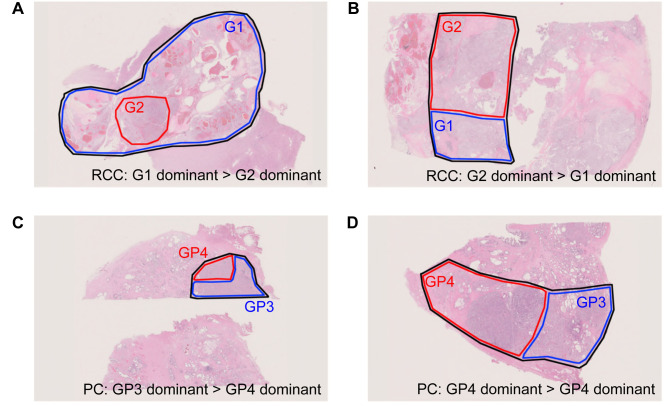

Patient cohort and samples. Eighty-three cases of RCC and 419 cases of PC were diagnosed by either surgery or biopsy. Of these, 69 cases of RCC and 56 cases of PC were analyzed by cancer panel tests. After applying the exclusion criteria, data from 61 cases of clear cell RCC (ccRCC) and 46 cases of PC were included in this study (Figure 1). All specimens were pathologically reviewed by a pathologist (S Sugiyama) who evaluated the distribution of each tumor grade in the macro-dissected area in a blinded manner. Representative data of specimens of ccRCC and PC for the cancer panel tests are shown in Figure 2. Grade 2 ccRCC specimens included a different ratio grade 2 dominant area (Figure 2A and B). Grade group 2/3 PC included Gleason pattern 3- and 4-dominant specimens (Figure 2C and D).

Figure 1. Patient selection and composition of the clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) and prostate cancer (PC) cohorts. 69 RCCs and 56 PCs were tested by the cancer panels. After exclusion of ineligible participants, data from 61 RCC and 46 PC were analyzed in this study.

Figure 2. Representative data of tumor specimens. A and B: Representative data from a clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) specimen diagnosed as grade 2. Grade 1 was dominant in the sample area selected for the cancer panel test (A). Grade 2 was dominant in the sample area selected for the cancer panel test (B). The area enclosed by the black line was macro-dissected and used for DNA extraction following the cancer panel test. The area enclosed by the blue line was grade 1 ccRCC dominant area, while that enclosed by the red line was grade 2 ccRCC dominant area. C and D: Representative data of a prostate cancer (PC) specimen diagnosed as grade group 2/3. Gleason pattern 3 was dominant in the sample area selected for the cancer panel test (C). Gleason pattern 4 was dominant in the sample area selected for the cancer panel test (D). The area enclosed by the black line was macro-dissected and used for DNA extraction following the cancer panel test. The area enclosed by the blue line was Gleason pattern 3 dominant area, while the area enclosed by the red line was Gleason pattern 4 dominant area.

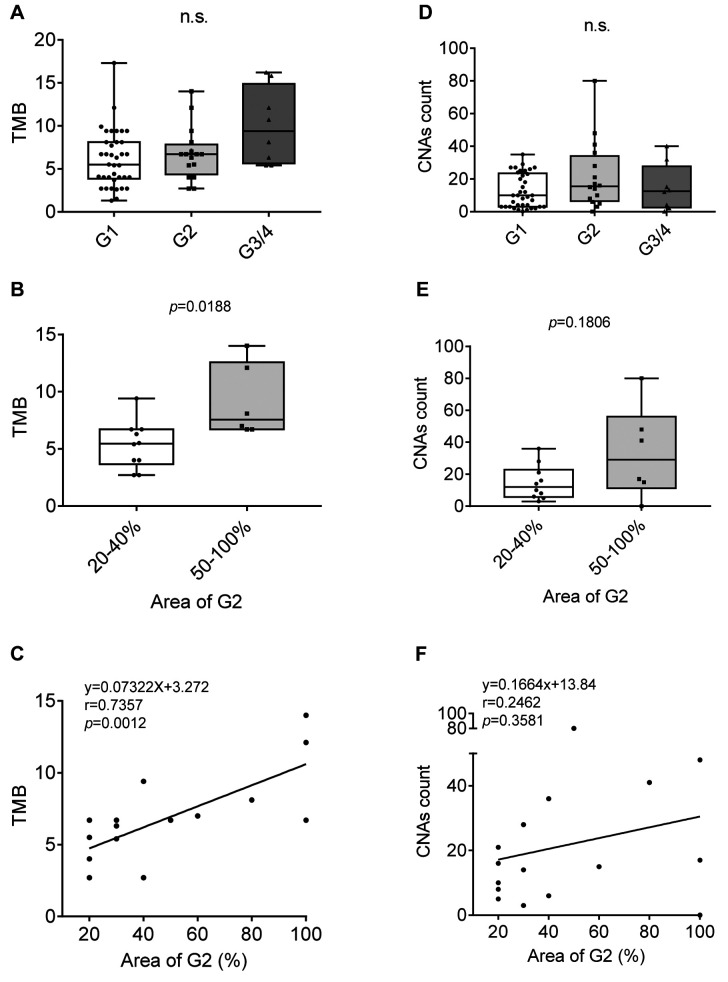

TMB and CNA count in ccRCC. The tumor mutation burden (TMB) in specimens of each ccRCC tumor grade was analyzed. The TMB in grade 3 or 4 ccRCC was increased in comparison to that in grade 1 or 2, but the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 3A). Since the WHO/ISUP grading system of RCC notes the highest tumor grade, grade 2 ccRCC tumors include grade 1 tumors with a small amount of grade 2, to 100% grade 2 tumors. To analyze the relationship of tumor grade distribution and TMB, we investigated the TMB only in the grade 2 group. The ratio of grade 2 distribution area was from 20–100% (the rest of the areas were grade 1). The median TMB in specimens with ≥50% grade 2 was significantly higher than that in those with <50% grade 2 (Figure 3B). In addition, a strong positive correlation between the TMB and the ratio of the grade 2 distribution area was observed (Figure 3C). We also investigated the CNA count using the same dataset. There was no significant correlation between the CNA count and the ratio of the grade 2 distribution area (Figure 3D-F).

Figure 3. The tumor mutation burden (TMB) and copy number alteration (CNA) count in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). A: TMB in grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3/4. B: TMB in cases with 20-40% grade 2 distribution area and 50-100%. C: The correlation between TMB and the ratio of the G2 distribution area in G2 ccRCC. D: The CNA count in grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3/4. E: CNA count in cases with 20-40% grade 2 distribution area and 50-100%. F: The correlation between CNA count and the ratio of the G2 distribution area in G2 ccRCC.

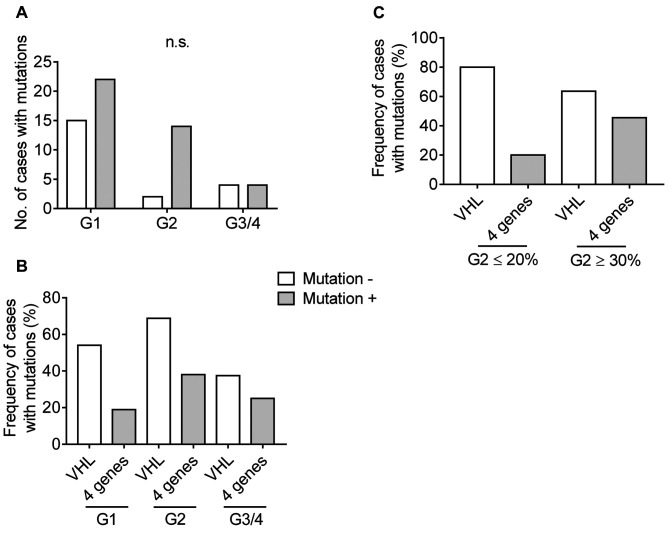

Gene mutations in ccRCC. We analyzed the frequency of actionable gene mutations in each tumor grade. The number of gene mutations in WHO/ISUP grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3/4 were 22 in 37 (59.5%), 14 in 16 (87.5%) and 4 in 8 (50.0%), respectively (Figure 4A). The frequency of gene mutations in grade 2 tended to be increased in comparison to G1; however, the difference was not statistically significant. Mutations in BAP1, PBRM1, SETD2 and PTEN play important roles in tumor evolution in ccRCC in addition to VHL mutation, which is the most common gene mutation in this type of cancer (18,22). VHL mutation was observed 54.1%, 68.8 and 37.5% of grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3/4, respectively. The rates of any mutation in the above 4 genes were 18.9%, 38.0 and 25.0% in grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3/4, respectively (Figure 4B). Subsequently, the mutation rate was analyzed according to the ratio of the grade 2 distribution area in grade 2. In 5 specimens with grade 2 ≤20%, 4 VHL mutations (80%) and a PBRM1 mutation (20%) were detected. On the other hand, 7 mutations in VHL (63.6%), 2 mutations in BAP1 and SETD2, and 1 mutation in PBRM1 and PTEN (45.4% in total) were detected in 11 specimens with ≥30% grade 2 distribution (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Gene mutations in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). A: The numbers of cases with or without gene mutation in each tumor grade of ccRCC. The statistical value was calculated using Fisher’s exact test with the Bonferroni post hoc test. B: The frequency of cases with VHL mutation or a mutation of BAP1, PBRM1, SETD2, or PTEN in each tumor grade of ccRCC. C: The frequency of cases with VHL mutation or a mutation of BAP1, PBRM1, SETD2, or PTEN in specimens with ≤20% grade 2 distribution and ≥30% grade 2 distribution.

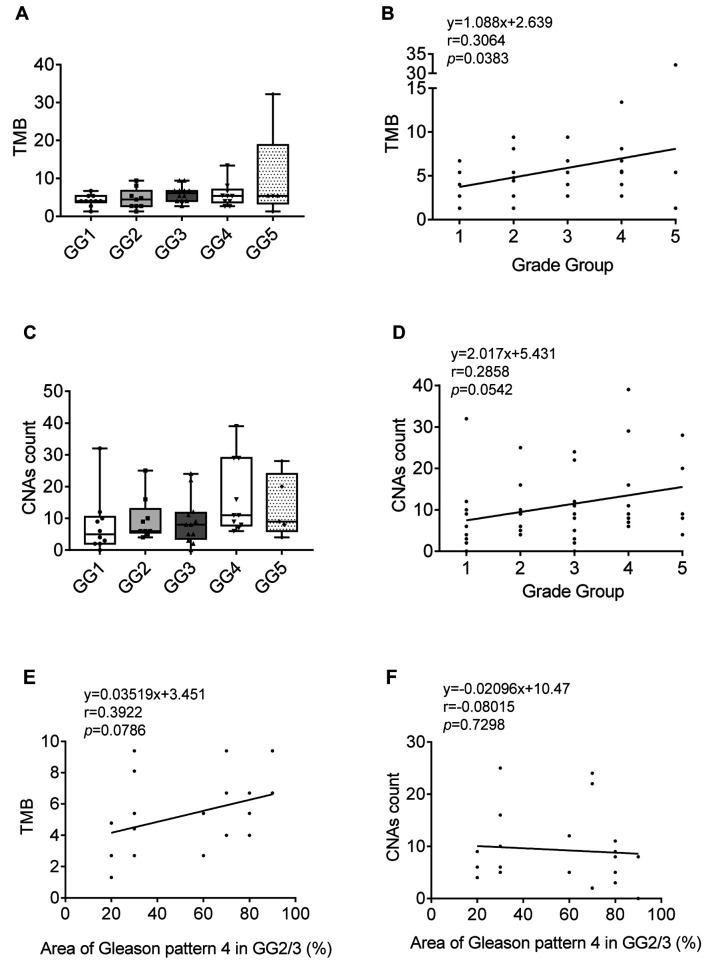

TMB and CNA count in PC. The prostate cancer grade group (GG) is a refined version of the Gleason score system. Features of Gleason ≤6, 3+4, 4+3, 8 (3+5, 4+4, 5+3), and 9 (4+5, 5+4)-10 (5+5) are classified to GG1-5, respectively. The TMB and CNA count according to each GG are shown in Figure 5A and C, respectively. Although the TMB and CNA count were high in some GG4 or GG5 samples, the median values showed no significant difference. There was a weak but positive correlation between TMB and GG (Figure 5B and D). The Gleason score, which is the basis of the GG is defined by adding together the 2 most common Gleason patterns with >5% distribution; thus, the distribution of the second component may range from 5-45% in Gleason score 3+4 (GG2) or 4+3 (GG3). However, the distribution of the Gleason pattern in the specimen used for the cancer panel test, a part of whole tumor, is not noted. To study whether the range of the second Gleason pattern in the specimen affected the TMB or CNA count, we analyzed the correlation between TMB/CNA count and the ratio of Gleason pattern 4 distribution in GG2/3. There was no significant correlation between the TMB/CNA count and the ratio of Gleason pattern 4 distribution (Figure 5E and F).

Figure 5. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) and copy number alteration (CNA) count of prostate cancer (PC). A: TMB in PC diagnosed as grade group 1-5. B: The correlation between TMB and grade group. C: The CNA count in PC diagnosed as grade group 1-5. D: The correlation between CNA count and grade group. E: The correlation between TMB and the ratio of Gleason pattern 4 distribution area in G3/4 PC. F: The correlation between CNA count and the ratio of Gleason pattern 4 distribution area in G3/4 PC.

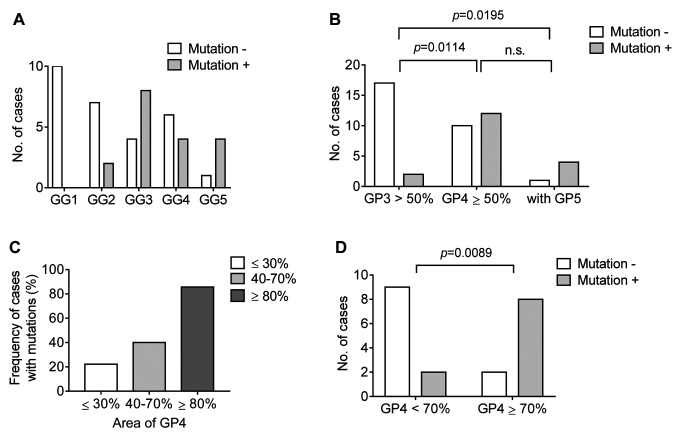

Gene mutations in PC. We analyzed the frequency of actionable gene mutations in each GG of PC; the number of cases with mutations is shown in Figure 6A. No gene mutation was detected in GG1, while higher GGs showed more mutations. Specimens with ≥50% Gleason pattern 4 or with a Gleason pattern 5 component had significantly more mutations in comparison to specimens with <50% Gleason pattern 3 (Figure 6B). The frequency of cases with mutations in GG2/3 according to the ratio of Gleason pattern 4 is shown in Figure 6C. Specimens with ≥70% Gleason pattern 4 had significantly more mutations in comparison to those with <70% Gleason pattern 4 in GG2/3.

Figure 6. Gene mutations in prostate cancer (PC). A: The number of cases with or without gene mutation in each grade group of PC. B: The number of cases with or without gene mutation in specimens with <50% Gleason pattern 3, with ≥50% Gleason pattern 4, or with any amount of Gleason pattern 5. The statistical value was calculated using Fisher’s exact test with the Bonferroni post hoc test. C: The frequency of cases with mutation in specimens with different distribution ratios of Gleason pattern 4 in GG2/3. D: The number of cases with or without gene mutation in GG2/3 specimens with <70% Gleason pattern 4 and ≥70% Gleason pattern 4. The statistical value was calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

Discussion

For the best yield of tumor-derived DNA extraction, pathologists need to select high tumor content areas in specimens. A higher tumor grade reflects the essence of genetic alterations from the most critical features of the cancer, and the precise detection of genetic alterations is important for genomics-focused treatments. However, whether a higher tumor grade distribution in the specimen impacts the sensitivity of the detection of genetic alterations has not been elucidated. For genomic analyses, the results of our study indicate that pathologists need to consider the distribution ratio of higher tumor grade areas when more than two different morphological features are present in a specimen, in addition to the tumor cell content.

In our cohort of patients with ccRCC, the TMB increased with higher ratio of grade 2 distribution. The TMB is a known favorable predictive factor of immune checkpoint inhibitor in several cancers, but its relevance in RCC is controversial (23). We demonstrated that the TMB may depend on the tumor grade distribution; thus, the evaluation of TMB using specimens with maximum distribution ratio of higher tumor grade may provide different results regarding the role of TMB in the prediction of ccRCC treatment. VHL degrades hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), which regulates the expression of a large number of target genes related to tumor progression (24,25). In line with a previous study, VHL was the most common mutated gene in ccRCC and was found in 55.7% in our cases (26). VHL mutation is important in the initial clonal expansion following the loss of chromosome 3p, which includes the VHL gene (22). Since the mutation occurs at the initial stage of tumorigenesis, i.e., decades before diagnosis, the frequency of VHL mutation was consistent through all tumor grades. Belzutifan, a potent, selective small molecule inhibitor of HIF-2α, has shown promising anti-cancer activity in ccRCC (27). As long as only VHL is targeted, it may not be necessary to select the higher tumor grade area for a genetic analysis in ccRCC. On the other hand, clonal or subclonal drivers of mutations of BAP1, PBRM1 PTEN, or SETD2 accelerate the rapid progression of RCC. Mutations in these genes were likely to be found in specimens with higher tumor grade (grade 2) distribution in WHO/ISUP grade 2 ccRCC. Treatments based on these mutations are being developing in many cancer types (28-31). In this context, the higher-grade tumor content is preferred to detect gene mutations other than the VHL mutation, which would maximize the chances of achieving genomics-focused treatments in RCC.

Since not all tumor grades are diagnosed by nuclear atypia like ccRCC, we verified our results using a prostate cancer dataset, in which the grade is defined by structural morphology; the so-called Gleason grading system. We identified no significant differences between GGs and TMB or CNA count, whereas the frequency of mutations was higher in specimens with an increased Gleason pattern 4 distribution area in GG2/3. Higher GG, which denotes an increased number of gene mutations, might be suitable for targeted therapies. In GG3/4, Gleason pattern 3-dominant specimens (≥70% Gleason pattern 3) had only two mutations in ECT2L and KDM6A in 11 samples. In Gleason pattern 4-dominant specimens (≥70% Gleason pattern 4), mutations were detected in 8 out of 10 cases. The mutations were in ARID1A, BRAF, CDK12, GRIN2A, IDH1, KDM6A, SMARCA4 and SPOP. Some of them are targets of approved or developing novel targeted therapies (32). The SPOP mutation was also reported to be a marker of a superior response to androgen deprivation therapy plus androgen receptor axis-targeted therapies, which are essential treatments for PC (33). It is preferred to maximize the distribution area of Gleason pattern 4 in a specimen to detect more mutations by a cancer panel test in GG2/3 PC. Conversely, that type of sample collection may not be necessary for a TMB analysis in PC.

We also analyzed whether these results are compatible with other types of cancer in 44 untreated breast cancer specimens (luminal A: 6, luminal B: 12, luminal HER2: 4, HER2: 4, triple negative: 18). There was no association between genetic alterations (TMB, CNA count, and frequency of gene mutation) and the nuclear features/amount of gland formation, which are part of the components of the Nottingham Histologic Score system (data not shown). This result, which is inconsistent with ccRCC or PC data, could be explained by the following reason: our breast cancer dataset included mostly aggressive cancer types. Nevertheless, sample collection from the highest nuclear or structure grade area with the maximum distribution is worth consideration in cancer panel tests.

Study limitations. It was a retrospective study based on a small sample size. Tumor cell sampling was performed by macro-dissection, and the tumor fraction data on the individual tumor grades was absent. Lower tumor cell content may affect the results of cancer panel tests. In addition, mutation calling in our dataset may differ from the results obtained using other mutation calling algorithms. Therefore, further clinical studies with larger datasets of cancer panel tests that are widely used in the clinical setting are needed to validate our results, in which several of our findings show several borderline significance or associations.

Conclusion

Genomic medicine contributes to accurate cancer diagnosis, effective treatment, and cancer prevention. Intratumor heterogeneity of genomic alteration may have an impact on cancer genomic medicine. Our study’s findings suggest that maximizing higher-grade tumor distribution as well as tumor cell content in a specimen is important for genomic analysis of ccRCC and PC. Precise results based on prior knowledge and our findings may contribute to better genomics-focused pharmacology.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: KMi. Data analysis and interpretation: KMi, SSu, SSa, IS, HF and KH. Data curation: IS, YK and HN. Clinical evaluations and treatment: KMi, SSu, KK, SK, SY, AM, MT, KS, TY, HE, KMa, TY SI and TD. Article writing: KMi. All Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ayane Kinoshita, Natsumi Haba and Hiroki Furukawa for their invaluable contributions to the data acquisition, and Jitsuhiro Yamada for helpful discussions. This work was partially supported by Gifu Prefecture Medical Association Research Grant.

References

- 1.Nagahashi M, Shimada Y, Ichikawa H, Kameyama H, Takabe K, Okuda S, Wakai T. Next generation sequencing-based gene panel tests for the management of solid tumors. Cancer Sci. 2019;110(1):6–15. doi: 10.1111/cas.13837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wakai T, Prasoon P, Hirose Y, Shimada Y, Ichikawa H, Nagahashi M. Next-generation sequencing-based clinical sequencing: toward precision medicine in solid tumors. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24(2):115–122. doi: 10.1007/s10147-018-1375-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeda M, Takahama T, Sakai K, Shimizu S, Watanabe S, Kawakami H, Tanaka K, Sato C, Hayashi H, Nonagase Y, Yonesaka K, Takegawa N, Okuno T, Yoshida T, Fumita S, Suzuki S, Haratani K, Saigoh K, Ito A, Mitsudomi T, Handa H, Fukuoka K, Nakagawa K, Nishio K. Clinical application of the FoundationOne CDx assay to therapeutic decision-making for patients with advanced solid tumors. Oncologist. 2021;26(4):e588–e596. doi: 10.1002/onco.13639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodhouse R, Li M, Hughes J, Delfosse D, Skoletsky J, Ma P, Meng W, Dewal N, Milbury C, Clark T, Donahue A, Stover D, Kennedy M, Dacpano-Komansky J, Burns C, Vietz C, Alexander B, Hegde P, Dennis L. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne Liquid CDx, a novel 324-Gene cfDNA-based comprehensive genomic profiling assay for cancers of solid tumor origin. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0237802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sah S, Chen L, Houghton J, Kemppainen J, Marko AC, Zeigler R, Latham GJ. Functional DNA quantification guides accurate next-generation sequencing mutation detection in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor biopsies. Genome Med. 2013;5(8):77. doi: 10.1186/gm481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Do H, Dobrovic A. Sequence artifacts in DNA from formalin-fixed tissues: causes and strategies for minimization. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):64–71. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.223040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball MW, Gorin MA, Drake CG, Hammers HJ, Allaf ME. The landscape of whole-genome alterations and pathologic features in genitourinary malignancies: an analysis of the Cancer Genome Atlas. Eur Urol Focus. 2017;3(6):584–589. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G, Zhao D, Spring DJ, DePinho RA. Genetics and biology of prostate cancer. Genes Dev. 2018;32(17-18):1105–1140. doi: 10.1101/gad.315739.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall CH, Fu W, Wang H, Baras AS, Lotan TL, Antonarakis ES. Prevalence of DNA repair gene mutations in localized prostate cancer according to clinical and pathologic features: association of Gleason score and tumor stage. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019;22(1):59–65. doi: 10.1038/s41391-018-0086-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Bai L, Lin H, Dong L, Zhang R, Cheng X, Liu Z, Ouyang Y, Ding K. Multiomics analysis of tumor mutational burden across cancer types. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:5637–5646. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moch H, Humphrey PA, Ulbright TM, Reuter V. Who classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon, France, International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferronika P, Kats-Ugurlu G, Haryana SM, Utoro T, Rinonce HT, Danarto R, de Lange K, Terpstra MM, Sijmons RH, Westers H, Kok K. Mutational heterogeneity between different regional tumour grades of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol. 2020;115:104431. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2020.104431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sauter G, Steurer S, Clauditz TS, Krech T, Wittmer C, Lutz F, Lennartz M, Janssen T, Hakimi N, Simon R, von Petersdorff-Campen M, Jacobsen F, von Loga K, Wilczak W, Minner S, Tsourlakis MC, Chirico V, Haese A, Heinzer H, Beyer B, Graefen M, Michl U, Salomon G, Steuber T, Budäus LH, Hekeler E, Malsy-Mink J, Kutzera S, Fraune C, Göbel C, Huland H, Schlomm T. Clinical utility of quantitative Gleason Grading in prostate biopsies and prostatectomy specimens. Eur Urol. 2016;69(4):592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocca C, Rocca G, Zampieri P, Dell’atti L, Bianchi N, Ippolito C, Aguiari G. Somatic and germline variants affect prognosis and susceptibility in prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2023;43(7):2941–2949. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.16465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Sousa E Melo F, Vermeulen L, Fessler E, Medema JP. Cancer heterogeneity – a multifaceted view. EMBO Rep. 2013;14(8):686–695. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher R, Pusztai L, Swanton C. Cancer heterogeneity: implications for targeted therapeutics. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(3):479–485. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Lih TM, Dhanasekaran SM, Mannan R, Chen L, Cieslik M, Wu Y, Lu RJ, Clark DJ, Kołodziejczak I, Hong R, Chen S, Zhao Y, Chugh S, Caravan W, Naser Al Deen N, Hosseini N, Newton CJ, Krug K, Xu Y, Cho KC, Hu Y, Zhang Y, Kumar-Sinha C, Ma W, Calinawan A, Wyczalkowski MA, Wendl MC, Wang Y, Guo S, Zhang C, Le A, Dagar A, Hopkins A, Cho H, Leprevost FDV, Jing X, Teo GC, Liu W, Reimers MA, Pachynski R, Lazar AJ, Chinnaiyan AM, Van Tine BA, Zhang B, Rodland KD, Getz G, Mani DR, Wang P, Chen F, Hostetter G, Thiagarajan M, Linehan WM, Fenyö D, Jewell SD, Omenn GS, Mehra R, Wiznerowicz M, Robles AI, Mesri M, Hiltke T, An E, Rodriguez H, Chan DW, Ricketts CJ, Nesvizhskii AI, Zhang H, Ding L, Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium Histopathologic and proteogenomic heterogeneity reveals features of clear cell renal cell carcinoma aggressiveness. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(1):139–163.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizutani K, Hirade K, Sugiyama S, Kato Y, Nishihara H, Ishihara S. Genomic landscape of treatment-naïve urological cancers using next-generation sequencing-based panel test in the Japanese population. Int J Urol. 2022;29(8):909–911. doi: 10.1111/iju.14927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizutani K, Yokoi S, Sawada S, Sakamoto I, Kameyama K, Kamei S, Hirade K, Sugiyama S, Matsunaga K, Yamada T, Kato Y, Nishihara H, Ishihara S, Deguchi T. Derivative chromosome 3 loss from t(3;6)(q12;q14) followed by differential VHL mutations underlie multifocal ccRCC. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2022;19(6):740–746. doi: 10.21873/cgp.20356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi H, Tanishima S, Fujii K, Mori R, Okada C, Yanagita E, Shibata Y, Matsuoka R, Amano T, Yamada T, Yabe I, Kinoshita I, Komatsu Y, Dosaka-Akita H, Nishihara H. Clinical impact of a cancer genomic profiling test using an in-house comprehensive targeted sequencing system. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(10):3926–3937. doi: 10.1111/cas.14608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimozaki K, Hayashi H, Tanishima S, Horie S, Chida A, Tsugaru K, Togasaki K, Kawasaki K, Aimono E, Hirata K, Nishihara H, Kanai T, Hamamoto Y. Concordance analysis of microsatellite instability status between polymerase chain reaction based testing and next generation sequencing for solid tumors. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):20003. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99364-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricketts CJ, Linehan WM. Multi-regional sequencing elucidates the evolution of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cell. 2018;173(3):540–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raimondi A, Sepe P, Zattarin E, Mennitto A, Stellato M, Claps M, Guadalupi V, Verzoni E, de Braud F, Procopio G. Predictive biomarkers of response to immunotherapy in metastatic renal cell cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1644. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandriota SJ, Turner KJ, Davies DR, Murray PG, Morgan NV, Sowter HM, Wykoff CC, Maher ER, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ, Maxwell PH. HIF activation identifies early lesions in VHL kidneys. Cancer Cell. 2002;1(5):459–468. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iacovelli R, Arduini D, Ciccarese C, Pierconti F, Strusi A, Piro G, Carbone C, Foschi N, Daniele G, Tortora G. Targeting hypoxia-inducible factor pathways in sporadic and Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome-related kidney cancers. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;176:103750. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499(7456):43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonasch E, Donskov F, Iliopoulos O, Rathmell WK, Narayan VK, Maughan BL, Oudard S, Else T, Maranchie JK, Welsh SJ, Thamake S, Park EK, Perini RF, Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, MK-6482-004 Investigators Belzutifan for renal cell carcinoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(22):2036–2046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun DA, Ishii Y, Walsh AM, Van Allen EM, Wu CJ, Shukla SA, Choueiri TK. Clinical validation of PBRM1 alterations as a marker of immune checkpoint inhibitor response in renal cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(11):1631–1633. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fennell DA, King A, Mohammed S, Branson A, Brookes C, Darlison L, Dawson AG, Gaba A, Hutka M, Morgan B, Nicholson A, Richards C, Wells-Jordan P, Murphy GJ, Thomas A, MiST1 study group Rucaparib in patients with BAP1-deficient or BRCA1-deficient mesothelioma (MiST1): an open-label, single-arm, phase 2a clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(6):593–600. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu M, Zhao B, Liu M, Wu L, Li Y, Zhai Y, Shen X. Pan-cancer analysis of SETD2 mutation and its association with the efficacy of immunotherapy. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5(1):51. doi: 10.1038/s41698-021-00193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sweeney C, Bracarda S, Sternberg CN, Chi KN, Olmos D, Sandhu S, Massard C, Matsubara N, Alekseev B, Parnis F, Atduev V, Buchschacher GL Jr, Gafanov R, Corrales L, Borre M, Stroyakovskiy D, Alves GV, Bournakis E, Puente J, Harle-Yge ML, Gallo J, Chen G, Hanover J, Wongchenko MJ, Garcia J, de Bono JS. Ipatasertib plus abiraterone and prednisolone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (IPATential150): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):131–142. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00580-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, Roboz GJ, Altman JK, Mims AS, Swords R, Collins RH, Mannis GN, Pollyea DA, Donnellan W, Fathi AT, Pigneux A, Erba HP, Prince GT, Stein AS, Uy GL, Foran JM, Traer E, Stuart RK, Arellano ML, Slack JL, Sekeres MA, Willekens C, Choe S, Wang H, Zhang V, Yen KE, Kapsalis SM, Yang H, Dai D, Fan B, Goldwasser M, Liu H, Agresta S, Wu B, Attar EC, Tallman MS, Stone RM, Kantarjian HM. Durable remissions with ivosidenib in IDH1-mutated relapsed or refractory AML. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2386–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swami U, Graf RP, Nussenzveig RH, Fisher V, Tukachinsky H, Schrock AB, Li G, Ross JS, Sayegh N, Tripathi N, Mathew Thomas V, Oxnard GR, Antonarakis ES, Agarwal N. SPOP mutations as a predictive biomarker for androgen receptor axis–targeted therapy in de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(22):4917–4925. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-22-2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]