Abstract

During C. elegans development, 1090 somatic cells are generated of which 131 reproducibly die, many through apoptosis. The C. elegans BH3-only gene egl-1 is the key activator of apoptosis in somatic tissues, and it is predominantly expressed in ‘cell death' lineages i.e. lineages in which apoptotic cell death occurs. egl-1 expression is regulated at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. For example, we previously showed that the miR-35 and miR-58 families of miRNAs repress egl-1 expression in mothers of ‘unwanted' cells by binding to the 3′ UTR of egl-1 mRNA, thereby increasing egl-1 mRNA turnover. In a screen for RNA-binding proteins with a role in the post-transcriptional control of egl-1 expression, we identified EIF-3.H (ortholog of human eIF3H) and HRPR-1 (ortholog human hnRNP R/Q) as potential activators of egl-1 expression. In addition, we demonstrate that the knockdown of the eif-3.H or hrpr-1 gene by RNA-mediated interference (RNAi) results in the inappropriate survival of unwanted cells during C. elegans development. Our study provides novel insight into how egl-1 expression is controlled to cause the reproducible pattern of cell death observed during C. elegans development.

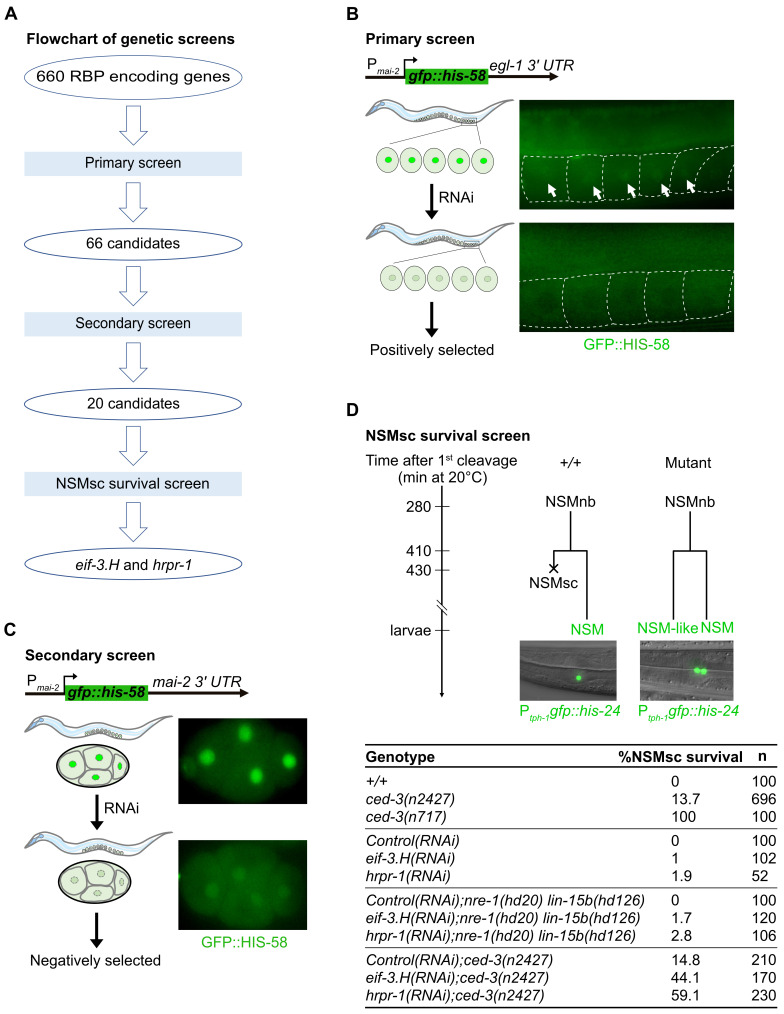

Figure 1. Genetic screen for activators of egl-1 expression using RNA-mediated interference .

A) Flowchart of genetic screens for activators of egl-1 expression. (B) Primary (positive) screen for activators of egl-1 expression. After RNAi-mediated knockdown of RBP genes, candidates were identified by screening for a decrease in GFP:: HIS-58 signal in oocytes of animals carrying the reporter P mai- 2 gfp:: his-58 :: egl-1 3′ UTR ( bcSi26 ). White arrows point to GFP:: HIS-58 signal in oocyte nuclei. (C) Secondary (negative) screen. Nonspecific candidates were eliminated by screening for a decrease in GFP:: HIS-58 signal in embryos of animals carrying the reporter P mai- 2 gfp:: his-58 :: mai-2 3′ UTR ( bcSi25 ). (D) NSM sister cell (NSMsc) survival screen. (Top) Schematics showing the NSM lineage in wild-type ( +/+ ) and ced-3 (717) animals (Ellis and Horvitz, 1986). The two bilaterally symmetric neurosecretory motoneuron (NSM) neuroblasts (NSMnb) (left and right) divide ~410 minutes after the first zygotic cleavage (at 20°C), each generating one NSM neuron, which is programmed to survive, and one NSM sister cell (NSMsc), which is programmed to die (‘unwanted' daughter cell) (Sulston et al., 1983). In wild-type ( +/+ ) animals, the NSMsc undergoes apoptotic cell death, resulting in one NSM from each NSM neuroblast. When apoptosis is blocked, the NSMsc inappropriately survives, resulting in an extra ‘NSM-like' cell. The NSM and the ‘undead' NSMsc can be identified in the anterior pharynx of L3/L4 larvae using the reporter P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 (Yan et al., 2013). (Bottom) RNAi knockdown of eif-3.H or hrpr-1 causes NSMsc survival. To enhance RNAi efficiency in the NSM lineage, RNAi experiments were also performed in the nre-1 ( hd20 ) lin-15b ( hd126 ) background (Schmitz et al., 2007). The percentage of NSMsc survival is enhanced in the background of n2427 , a weak loss of function mutation of ced-3 (Shaham et al., 1999). The sample size (n) is shown in the table. The complete genotypes of strains used are provided in Table 1.

Description

Programmed cell death removes unwanted cells and helps shape organs during development (Suzanne and Steller, 2013) . Dysregulation of programmed cell death contributes to several diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative or autoimmune diseases (Favaloro et al., 2012) . Caenorhabditis elegans ( C. elegans ) is a powerful model for studying programmed cell death. Programmed cell death during C. elegans development occurs in a highly reproducible pattern. Sulston and co-workers discovered that, among 1090 somatic cells generated during the development of a C. elegans hermaphrodite, precisely 131 cells die, many through apoptosis (Conradt et al., 2016; Horvitz, 1999; Sulston and Horvitz, 1977; Sulston et al., 1983) . The process of apoptosis is tightly regulated through a genetic pathway that is evolutionarily conserved from nematodes to mammals. In C. elegans , this pathway consists of four key components: egl-1 , ced-9 , ced-4 , and ced-3 (Conradt et al., 2016; Horvitz, 1999) . The egl-1 gene is necessary and sufficient for apoptosis and encodes a pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein, EGL-1 , which binds to the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2-like protein CED-9 in unwanted cells. This displaces a dimer of the Apaf1-like protein CED-4 from CED-9 , thereby allowing CED-4 to form the apoptosome, which facilitates the autocatalytic activation of the CED-3 caspase. Activated CED-3 cleaves multiple substrates, ultimately leading to cell death. In contrast to ced-9 , ced-4 , and ced-3 , which appear to be broadly expressed at least during C. elegans embryogenesis (Chen et al., 2000; Maurer et al., 2007) , egl-1 expression is essentially restricted to cell death lineages (Conradt and Horvitz, 1999; Nehme et al., 2010) . Thus, the spatiotemporal pattern of egl-1 expression and, hence, the control of egl-1 expression is critical for the highly reproducible pattern of cell death observed during C. elegans development.

egl-1 expression during C. elegans development is regulated at the transcriptional level by lineage-specific transcription factors that act through specific cis -acting elements upstream or downstream of the egl-1 transcription unit (Conradt et al., 2016) . In addition, egl-1 expression is controlled at the post-transcriptional level by miR-35 and miR-58 family miRNAs that act through the 3′ UTR of the egl-1 mRNA to repress egl-1 expression in mothers of unwanted cells, thereby preventing their precocious death (Sherrard et al., 2017) . Apart from binding sites for miR-35 and miR-58 family microRNAs, the egl-1 3' UTR contains additional conserved elements (Extended data figure 1). For this reason, we propose that factors other than microRNAs, such as RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), may contribute to the post-transcriptional regulation of egl-1 expression and, hence, the highly reproducible pattern of cell death during C. elegans development.

To identify RBPs that promote egl-1 expression, we performed a systematic RNAi (RNA-mediated interference) screen in C. elegans . To that end, we first generated a comprehensive list of previously reported C. elegans RBPs. An initial list of C. elegans RBP-encoding genes published by Wang et al. contains 319 genes that were identified by searching for genes encoding RNA-binding domains (RBDs) (Wang et al., 2009) . By searching for additional putative RBDs, Tamburino et al. increased the number of putative C. elegans RBP-encoding genes from 319 to 887 (Extended data table 1a) (Tamburino et al., 2013) . They included additional putative RBDs and protein classes such as dsRBDs and ribosomal proteins as well as C2H2 zinc finger- and SAM domain-containing proteins. In addition, systematic approaches were employed to experimentally map mRNA-binding proteins in yeast and mammalian cells by capturing in vivo cross-linked mRNA–protein complexes and by identifying associated proteins by mass spectrometry (Scherrer et al., 2010; Tsvetanova et al., 2010) . In a poly(A)-containing mRNA-capturing experiment, Matia-González et al. identified 594 proteins that interact with polyadenylated mRNAs in C. elegans (Matia-González et al., 2015). These mRNA-binding proteins are encoded by 591 genes (Extended data table 1b). However, only a small fraction of these 591 RBP genes (151) overlaps with the 887 RBP genes reported by Tamburino et al. (Extended data figure 2A). In addition, many previously reported RBPs, such as GLD-3 (Eckmann et al., 2002) , MEX-3 and PUF-8 (Ariz et al., 2009) , are missing from this list of 591 RBP genes, suggesting that the RBPs identified by Matia-González et al. do not represent all RBPs in C. elegans . Thus, we incorporated the lists published by Tamburino et al. and Matia-González et al. and conducted Gene Ontology (GO) and phenotype enrichment analyses (Extended data figure 2B, Extended data table 1c-1e). Genes with general functions, such as genes encoding tRNA-binding proteins or ribosomal subunits, were excluded (Extended data table 1d). Interestingly, some RBP genes are also enriched in phenotypes such as ‘cell death variants' (Extended data table 1e). These genes were retained in the final list for the RNAi screen. The final RBP compendium contained 800 genes (Extended data figure 2B, Extended data table 1f) of which 660 genes are represented in the Ahringer RNAi library (Kamath and Ahringer, 2003; Kamath et al., 2003) (Extended data table 1g). These 660 genes were subjected to the following RNAi screens for activators of egl-1 expression (referred to as ‘ egl-1 activators').

We first screened the 660 genes for potential egl-1 activators using an egl-1 3′ UTR reporter ( Figure 1B, P rimary screen) (Sherrard et al., 2017) . In this reporter, the egl-1 3′ UTR is fused to a fusion of the coding sequences of gfp and Histone 2B gene his-58 ( gfp:: his-58 ), and the expression of the resulting fusion gene is driven by the promoter of the gene mai-2 , which is ubiquitously transcribed (Ichikawa et al., 2006) . The use of the mai-2 promoter ensures transcription of the reporter in all cells, which allows us to monitor the impact of the 3′ UTR on reporter expression. A single copy of this reporter was inserted into the C. elegans genome, generating the transgene P mai-2 gfp:: his-58 :: egl-1 3′ UTR ( bcSi26 ) (Sherrard et al., 2017) . The expression of P mai-2 gfp:: his-58 :: egl-1 3′ UTR is repressed in embryos; however, in oocytes, moderate expression is detected ( Figure 1B ) (Sherrard et al., 2017) . By screening for a decrease in GFP:: HIS-58 signal in oocytes, 66 activator candidates were identified ( Figure 1A, 1B, Extended data table 2a). After the primary screen, we conducted a secondary (negative) screen for activators that are specific to the egl-1 3′ UTR. To that end, we used a single copy integration of the mai-2 3′ UTR reporter P mai- 2 gfp:: his-58 :: mai-2 3′ UTR ( bcSi25 ). This reporter differs from the egl-1 3′ UTR reporter ( bcSi26 ) only in its 3′ UTR but it is ubiquitously expressed in all cells ( Figure 1C ) (Sherrard et al., 2017) . By screening for a decrease in GFP:: HIS-58 signal in embryos carrying P mai- 2 gfp:: his-58 :: mai-2 3′ UTR ( bcSi25 ), 41 out of 66 candidates were considered general nonspecific activators and were excluded from subsequent analyses. The remaining 25 candidates were considered specific for the egl-1 3′ UTR. The identities of the RNAi clones for these candidates were verified through Sanger sequencing. Twenty of them contained the correct insert ( Figure 1A, E xtended data table 2b).

The loss of activators of egl-1 is expected to reduce egl-1 activity and result in a cell-death defective (Ced) phenotype, namely, the inappropriate survival of unwanted cells (Conradt et al., 2016; Nehme and Conradt, 2008) . In wild-type embryos, the NSMsc dies soon after its birth ( Figure 1D ). When apoptosis is blocked, for example by a strong ced-3 loss-of-function mutation n717 (Ellis and Horvitz, 1986) , the NSMsc survives and forms an NSM-like cell. The NSM and ‘undead' NSMsc can be visualized by the expression of the reporter P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 ( Figure 1D ) (Yan et al., 2013) . RNAi knockdown of eif-3.H or hrpr-1 (also known as hrp-2 ) caused a low rate of NSMsc survival in bcSi126 (P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 ) animals (1% for eif-3.H (RNAi) and 1.9% for hrpr-1 (RNAi) , respectively) ( Figure 1D ). Most C. elegans neurons are resistant to RNAi (Firnhaber and Hammarlund, 2013; Schmitz et al., 2007) . The nre-1 ( hd20 ) lin-15b ( hd126 ) background has been shown to enhance RNAi efficiency in neurons (Schmitz et al., 2007) . For this reason, we also performed RNAi in a nre-1 ( hd20 ) lin-15b ( hd126 ) background. In this background, RNAi knockdown of eif-3.H or hrpr-1 caused 1.7% or 2.8% NSMsc survival, respectively ( Figure 1D ). By contrast, 0% NSMsc survival is detected in bcSi126 (P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 ) wild-type ( +/+ ) or bcSi126 (P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 ); nre-1 ( hd20 ) lin-15b ( hd126 ) animals that are fed with the control RNAi clone. We also determined NSMsc survival in the sensitized background of the weak ced-3 loss-of-function mutation n2427 (Shaham et al., 1999) . In bcIs66 (P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 ); ced-3 ( n2427 ) animals, the apoptosis pathway is partially inactivated, resulting in 13.7% NSMsc survival ( Figure 1D ). In addition, bcIs66 (P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 ); ced-3 ( n2427 ) animals fed with the control RNAi clone show 14.8% NSMsc survival. In contrast, eif-3.H (RNAi) and hrpr-1 (RNAi) show a significant enhancement of NSMsc survival in bcIs66 (P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 ); ced-3 ( n2427 ) animals (44.1% for eif-3.H (RNAi) and 59.1% for hrpr-1 (RNAi) , respectively) ( Figure 1D ). These data suggest that eif-3.H and hrpr-1 have pro-apoptotic activity and contribute to the activation of apoptosis possibly through promoting egl-1 expression at the post-transcriptional level.

EIF-3.H is an ortholog of human eIF3H, which regulates the translation of mRNAs (Lee et al., 2015) . In zebrafish, it was shown that eIF3H promotes target gene translation during embryogenesis by targeting specific mRNAs to polysomes (Choudhuri et al., 2013) . In C. elegans , EIF-3.H was reported to promote axon guidance (Schmitz et al., 2007) . Our results show that C. elegans EIF-3.H possibly acts as an activator of egl-1 expression. In the future, it will be interesting to determine whether EIF-3.H enhances egl-1 mRNA translation by recruiting egl-1 mRNA to polysomes. HRPR-1 (also known as HRP-2 ) is an ortholog of human hnRNP R, hnRNP Q (Syncrip) and ACF protein, the essential complementation factor in ApoB mRNA editing (Kinnaird et al., 2004) . C. elegans HRPR-1 contains three RNA-recognition motifs (RRM) and a C-terminal RG/RGG repeat element, indicating that it has RNA-binding activity (Kinnaird et al., 2004) . In addition , HRPR-1 regulates mRNA splicing by binding to UCUAUC splicing regulatory elements within target mRNAs, which include unc-52 mRNA and lin-10 mRNA (Kabat et al., 2009) . In mammals, hnRNP R regulates mRNA localization in neurons (Dombert et al., 2014; Glinka et al., 2010) . For example, hnRNP R directs the localization of β-actin mRNA to axons by binding to the 3′ UTR of β-actin mRNA (Glinka et al., 2010; Rossoll et al., 2003) . hnRNP Q has been reported to regulate mRNA splicing (Chen et al., 2008) as well as mRNA transport (McDermott et al., 2012) , translation (Svitkin et al., 2013) and stability (Grosset et al., 2000) . Therefore, C. elegans HRPR-1 may be involved in several aspects of the lifecycle of egl-1 mRNA. In summary, our data suggest that, in addition to microRNAs, RBPs are likely to be involved in the control of egl-1 expression at the post-transcriptional level and the activation of apoptosis during C. elegans development.

Methods

C. elegans strains and maintenance

The strains were maintained at 20°C on nematode growth medium (NGM) plates with E. coli OP50 bacterial lawns (Brenner, 1974) , unless otherwise specified. The stains used are listed in Table 1. The mutations and transgenes used were: LG I: bcSi25 [P mai-2 gfp:: his-58 :: mai-2 3ʹ UTR + unc-119 (+) ] (Sherrard et al., 2017) , bcSi26 [P mai-2 gfp:: his-58 :: egl-1 3ʹ UTR + unc-119 (+) ] (Sherrard et al., 2017) ; LG III: bcIs66 [P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 + lin-15 (+) ] (Yan et al., 2013) , bcSi126 [P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 :: tbb-2 3′ UTR + unc-119 (+) ] (This study), unc-119 (ed3) (Maduro and Pilgrim, 1995) ; LG IV: ced-3 ( n2427 ) (Shaham et al., 1999) , ced-3 ( n717 ) (Ellis and Horvitz, 1986) ; LG V: ltIs44 [P pie-1 mCherry::PH(PLC1 delta1 ) + unc-119 (+) ] (Audhya et al., 2005) ; LG X: nre-1 ( hd20 ) (Schmitz et al., 2007) , lin-15b ( hd126 ) (Schmitz et al., 2007) .

Cloning and plasmid construction

To construct the plasmid pBC1969 (P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 :: tbb-2 3′ UTR ), a 1.7 kb DNA fragment of the tph-1 promoter region including the first exon was first amplified by PCR from C. elegans genomic DNA with primers 5ʹ-TGCATCGCGCGCACCGTACGTTCTCGCGAATTGCGGCCGAC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-GGAGCTGAAAGTACAGAAATTAC-3ʹ. Next, a 958 bp GFP fragment was amplified by PCR from the plasmid pBC1484 (Sherrard et al., 2017) with primers 5ʹ-ATTTCTGTACTTTCAGCTCCATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTTC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-ACAACAGCGGAATCAGACATACTAGTTCTAGAGCGGCCGCCAC-3ʹ. Then, a 730 bp his-24 fragment was amplified by PCR from C. elegans genomic DNA with primers 5ʹ-ATGTCTGATTCCGCTGTTGTTG-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TTAGGCCTTGGCGGCTGGCT-3ʹ. Finally, a 371 bp tbb-2 3 ′ UTR fragment was amplified by PCR from the plasmid pCFJ601 (Frokjaer-Jensen et al., 2012) with primers 5ʹ-AGCCAGCCGCCAAGGCCTAAATGCAAGATCCTTTCAAGCATTC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-AGAGGGTACCAGAGCTCACCTAGGTGAGACTTTTTTCTTGGCGGCAC-3ʹ. These fragments have 20 bp overlapping ends and were then assembled into the backbone pCFJ350 (Frokjaer-Jensen et al., 2012) between the BsiWI and AvrII restriction sites using the NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (NEB, #E2621L). The Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB, #M0530L) was used for PCRs. The insert region of plasmid generated was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Microinjection and transgenic animals

To generate the Mos1 transposon-mediated Single-Copy Insertion (MosSCI) (Frokjaer-Jensen et al., 2012; Frokjaer-Jensen et al., 2008) transgene bcSi126 [P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 :: tbb-2 3′ UTR + unc-119 (+) ], the universal MosSCI strain EG8080 [ oxTi444 unc-119 (ed3) III] was used for germline microinjection and for targeted insertion onto chromosome III. The plasmid pBC1969 [P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 :: tbb-2 3′ UTR + unc-119 (+) ] was injected at a concentration of 30 ng/μl with co-injection plasmids 50 ng/μl pCFJ601 (P eft-3 Mos1 transposase ), 10 ng/μl pGH8 (P rab-3 mCherry:: unc-54 3′ UTR ), 2.5 ng/μl pCFJ90 (P myo-2 mCherry:: unc-54 3′ UTR ), and 5 ng/μl pCFJ104 (P myo-3 mCherry:: unc-54 3′ UTR ).

Genetic screen by RNA-mediated interference

Genetic screen by RNA-mediated interference (RNAi) was performed using the updated Ahringer RNAi feeding library (Kamath and Ahringer, 2003; Kamath et al., 2003) distributed by Source BioScience Ltd ( https://sourcebioscience.com ). This library covers ~87% of the currently annotated C. elegans protein-coding genes. Bacterial RNAi clones carrying the constructs that express relevant dsRNAs were cultured in 100 µL of LB medium containing 100 μg/mL carbenicillin in a 96-well plate at 37°C overnight. 10 µL of each bacteria culture was seeded into individual wells of a 12-well NGM plate containing 6 mM IPTG and 100 μg/mL carbenicillin as described previously (Rolland et al., 2019) . The seeded plates were incubated at 20°C overnight in the dark to induce dsRNA expression before use.

In the primary screen, the egl-1 3′ UTR reporter P mai-2 gfp:: his-58 :: egl-1 3′ UTR ( bcSi26 ) was used to screen for a decrease in gfp:: his-58 expression. Ten L3 larvae carrying P mai-2 gfp:: his-58 :: egl-1 3′ UTR ( bcSi26 ) were transferred into each well of the 12-well NGM plate seeded with bacterial RNAi clones. After the animals were fed with bacterial RNAi clones for 48 hours, the expression of gfp:: his-58 in nuclei of oocytes was scored. In wild-type animals, this reporter is repressed in embryos but moderately expressed in oocytes and germ cells. If gfp:: his-58 expression was reduced in oocytes after the knockdown of an RBP gene, this RBP was considered an activator candidate of egl-1 expression. In this screen, gfp RNAi and control RNAi were used as the positive control and negative control, respectively.

In the secondary (negative) screen, the mai-2 3′ UTR reporter P mai-2 gfp:: his-58 :: mai-2 3′ UTR ( bcSi25 ) was used to exclude non-specific regulators by screening for a decrease in gfp:: his-58 expression in 4-cell stage embryos. Candidates that reduced the expression of the mai-2 3′ UTR reporter after their knockdown were excluded. The identities of bacterial RNAi clones were confirmed by Sanger sequencing of the insert in the RNAi construct.

The percentage of NSMsc survival after RNAi-mediated knockdown of RBP genes was determined in the following way. Three L3 stage animals carrying the NSM reporter P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 were transferred to NGM plates seeded with bacterial RNAi clones. After three days, L3/L4 stage F1 progenies were scored for extra NSM-like cells, which are found in the anterior pharynx and labelled by the reporter P tph-1 gfp:: his-24 (Yan et al., 2013) . For RBP genes that cause larval arrest upon knockdown, L1/L2 stage F1 progeny was scored. In this screen, the control RNAi clone was used as a negative control.

Reagents

Table 1. List of strains used in this study.

Extended Data

Description: List of RBP genes in C. elegans. Resource Type: Dataset. DOI: 10.22002/fjp7q-n1732

Description: egl-1 activator candidates. Resource Type: Dataset. DOI: 10.22002/cdeer-7ah33

Description: Conserved features in the egl-1 3' UTR. The C. elegans egl-1 3′ UTR contains conserved elements in comparison to those of three other Caenorhabditis species. (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo). . Resource Type: Dataset. DOI: 10.22002/nhsx6-qv793

Description: Analysis of C. elegans RNA-binding proteins. (A) Overlap analysis of RNA-binding protein (RBP)-encoding genes reported by Tamburino et al., (2013) and Matia-Gonzalez et al., (2015). (B) Pipeline for RBP gene analyses, characterization, and selection. . Resource Type: Dataset. DOI: 10.22002/yspxf-ram42

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Some strains used in this study were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by UCL (Capital Equipment Fund), a predoctoral fellowship from the China Scholarship Council ( https://www.csc.edu.cn/ ) to YJ, a Wolfson Fellowship from the Royal Society ( https://royalsociety.org/ ) to BC (RSWF\R1\180008), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (https://www.dfg.de/en/index.jsp) (C0204/10-1 to BC) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (https://bbsrc.ukri.org/) (BB/V007572/1 and BB/V015648/1 to BC). The Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

References

- Ariz M, Mainpal R, Subramaniam K. C. elegans RNA-binding proteins PUF-8 and MEX-3 function redundantly to promote germline stem cell mitosis. Dev Biol. 2008 Dec 7;326(2):295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audhya A, Hyndman F, McLeod IX, Maddox AS, Yates JR 3rd, Desai A, Oegema K. A complex containing the Sm protein CAR-1 and the RNA helicase CGH-1 is required for embryonic cytokinesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 2005 Oct 24;171(2):267–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974 May 1;77(1):71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Lambie EJ, Bindu S, Mikeladze-Dvali T, Conradt B. Engulfment pathways promote programmed cell death by enhancing the unequal segregation of apoptotic potential. Nat Commun. 2015 Dec 10;6:10126–10126. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Hersh BM, Conradt B, Zhou Z, Riemer D, Gruenbaum Y, Horvitz HR. Translocation of C. elegans CED-4 to nuclear membranes during programmed cell death. Science. 2000 Feb 25;287(5457):1485–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HH, Chang JG, Lu RM, Peng TY, Tarn WY. The RNA binding protein hnRNP Q modulates the utilization of exon 7 in the survival motor neuron 2 (SMN2) gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 Sep 15;28(22):6929–6938. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01332-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri A, Maitra U, Evans T. Translation initiation factor eIF3h targets specific transcripts to polysomes during embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 May 28;110(24):9818–9823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302934110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt B, Horvitz HR. The TRA-1A sex determination protein of C. elegans regulates sexually dimorphic cell deaths by repressing the egl-1 cell death activator gene. Cell. 1999 Aug 6;98(3):317–327. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt B, Wu YC, Xue D. Programmed Cell Death During Caenorhabditis elegans Development. Genetics. 2016 Aug 1;203(4):1533–1562. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.186247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombert B, Sivadasan R, Simon CM, Jablonka S, Sendtner M. Presynaptic localization of Smn and hnRNP R in axon terminals of embryonic and postnatal mouse motoneurons. PLoS One. 2014 Oct 22;9(10):e110846–e110846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckmann CR, Kraemer B, Wickens M, Kimble J. GLD-3, a bicaudal-C homolog that inhibits FBF to control germline sex determination in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2002 Nov 1;3(5):697–710. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell. 1986 Mar 28;44(6):817–829. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaloro B, Allocati N, Graziano V, Di Ilio C, De Laurenzi V. Role of apoptosis in disease. Aging (Albany NY) 2012 May 1;4(5):330–349. doi: 10.18632/aging.100459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firnhaber C, Hammarlund M. Neuron-specific feeding RNAi in C. elegans and its use in a screen for essential genes required for GABA neuron function. PLoS Genet. 2013 Nov 7;9(11):e1003921–e1003921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frøkjær-Jensen C, Davis MW, Ailion M, Jorgensen EM. Improved Mos1-mediated transgenesis in C. elegans. Nat Methods. 2012 Jan 30;9(2):117–118. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frøkjaer-Jensen C, Davis MW, Hopkins CE, Newman BJ, Thummel JM, Olesen SP, Grunnet M, Jorgensen EM. Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 2008 Oct 26;40(11):1375–1383. doi: 10.1038/ng.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinka M, Herrmann T, Funk N, Havlicek S, Rossoll W, Winkler C, Sendtner M. The heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein-R is necessary for axonal beta-actin mRNA translocation in spinal motor neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 Feb 18;19(10):1951–1966. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosset C, Chen CY, Xu N, Sonenberg N, Jacquemin-Sablon H, Shyu AB. A mechanism for translationally coupled mRNA turnover: interaction between the poly(A) tail and a c-fos RNA coding determinant via a protein complex. Cell. 2000 Sep 29;103(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz HR. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cancer Res. 1999 Apr 1;59(7 Suppl):1701s–1706s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa N, Ando C, Fumino M. Caenorhabditis elegans MAI-1 protein, which is similar to mitochondrial ATPase inhibitor (IF1), can inhibit yeast F0F1-ATPase but cannot be transported to yeast mitochondria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2006 Aug 2;38(2):93–99. doi: 10.1007/s10863-006-9009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat JL, Barberan-Soler S, Zahler AM. HRP-2, the Caenorhabditis elegans homolog of mammalian heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins Q and R, is an alternative splicing factor that binds to UCUAUC splicing regulatory elements. J Biol Chem. 2009 Aug 24;284(42):28490–28497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2003 Aug 1;30(4):313–321. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, Welchman DP, Zipperlen P, Ahringer J. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003 Jan 16;421(6920):231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnaird JH, Maitland K, Walker GA, Wheatley I, Thompson FJ, Devaney E. HRP-2, a heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein, is essential for embryogenesis and oogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp Cell Res. 2004 Aug 15;298(2):418–430. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AS, Kranzusch PJ, Cate JH. eIF3 targets cell-proliferation messenger RNAs for translational activation or repression. Nature. 2015 Apr 6;522(7554):111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature14267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maduro M, Pilgrim D. Identification and cloning of unc-119, a gene expressed in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system. Genetics. 1995 Nov 1;141(3):977–988. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.3.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matia-González AM, Laing EE, Gerber AP. Conserved mRNA-binding proteomes in eukaryotic organisms. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015 Nov 23;22(12):1027–1033. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer CW, Chiorazzi M, Shaham S. Timing of the onset of a developmental cell death is controlled by transcriptional induction of the C. elegans ced-3 caspase-encoding gene. Development. 2007 Feb 28;134(7):1357–1368. doi: 10.1242/dev.02818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott SM, Meignin C, Rappsilber J, Davis I. Drosophila Syncrip binds the gurken mRNA localisation signal and regulates localised transcripts during axis specification. Biol Open. 2012 Apr 11;1(5):488–497. doi: 10.1242/bio.2012885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehme R, Conradt B. egl-1: a key activator of apoptotic cell death in C. elegans. Oncogene. 2008 Dec 1;27 Suppl 1:S30–S40. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehme R, Grote P, Tomasi T, Löser S, Holzkamp H, Schnabel R, Conradt B. Transcriptional upregulation of both egl-1 BH3-only and ced-3 caspase is required for the death of the male-specific CEM neurons. Cell Death Differ. 2010 Feb 12;17(8):1266–1276. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland SG, Schneid S, Schwarz M, Rackles E, Fischer C, Haeussler S, Regmi SG, Yeroslaviz A, Habermann B, Mokranjac D, Lambie E, Conradt B. Compromised Mitochondrial Protein Import Acts as a Signal for UPR mt . . Cell Rep. 2019 Aug 13;28(7):1659–1669.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossoll W, Jablonka S, Andreassi C, Kröning AK, Karle K, Monani UR, Sendtner M. Smn, the spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene product, modulates axon growth and localization of beta-actin mRNA in growth cones of motoneurons. J Cell Biol. 2003 Nov 17;163(4):801–812. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer T, Mittal N, Janga SC, Gerber AP. A screen for RNA-binding proteins in yeast indicates dual functions for many enzymes. PLoS One. 2010 Nov 11;5(11):e15499–e15499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz C, Kinge P, Hutter H. Axon guidance genes identified in a large-scale RNAi screen using the RNAi-hypersensitive Caenorhabditis elegans strain nre-1(hd20) lin-15b(hd126). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jan 9;104(3):834–839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510527104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham S, Reddien PW, Davies B, Horvitz HR. Mutational analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell-death gene ced-3. Genetics. 1999 Dec 1;153(4):1655–1671. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.4.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrard R, Luehr S, Holzkamp H, McJunkin K, Memar N, Conradt B. miRNAs cooperate in apoptosis regulation during C. elegans development. Genes Dev. 2017 Feb 6;31(2):209–222. doi: 10.1101/gad.288555.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977 Mar 1;56(1):110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983 Nov 1;100(1):64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzanne M, Steller H. Shaping organisms with apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2013 Mar 1;20(5):669–675. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitkin YV, Yanagiya A, Karetnikov AE, Alain T, Fabian MR, Khoutorsky A, Perreault S, Topisirovic I, Sonenberg N. Control of translation and miRNA-dependent repression by a novel poly(A) binding protein, hnRNP-Q. PLoS Biol. 2013 May 21;11(5):e1001564–e1001564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburino AM, Ryder SP, Walhout AJ. A compendium of Caenorhabditis elegans RNA binding proteins predicts extensive regulation at multiple levels. G3 (Bethesda) 2013 Feb 1;3(2):297–304. doi: 10.1534/g3.112.004390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetanova NG, Klass DM, Salzman J, Brown PO. Proteome-wide search reveals unexpected RNA-binding proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One. 2010 Sep 10;5(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhao Y, Wong K, Ehlers P, Kohara Y, Jones SJ, Marra MA, Holt RA, Moerman DG, Hansen D. Identification of genes expressed in the hermaphrodite germ line of C. elegans using SAGE. BMC Genomics. 2009 May 9;10:213–213. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan B, Memar N, Gallinger J, Conradt B. Coordination of cell proliferation and cell fate determination by CES-1 snail. PLoS Genet. 2013 Oct 31;9(10):e1003884–e1003884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]