Abstract

The RAG1 and RAG2 proteins initiate V(D)J recombination by introducing double-strand breaks at the border between a recombination signal sequence (RSS) and a coding segment. To understand the distinct functions of RAG1 and RAG2 in signal recognition, we have compared the DNA binding activities of RAG1 alone and RAG1 plus RAG2 by gel retardation and footprinting analyses. RAG1 exhibits only a three- to fivefold preference for binding DNA containing an RSS over random sequence DNA. Although direct binding of RAG2 by itself was not detected, the presence of both RAG1 and RAG2 results in the formation of a RAG1-RAG2-DNA complex which is more stable and more specific than the RAG1-DNA complex and is active in V(D)J cleavage. These results suggest that biologically effective discrimination between an RSS and nonspecific sequences requires both RAG1 and RAG2. Unlike the binding of RAG1 plus RAG2, RAG1 can bind to DNA in the absence of a divalent metal ion and does not require the presence of coding flank sequence. Footprinting of the RAG1-RAG2 complex with 1,10-phenanthroline-copper and dimethyl sulfate protection reveal that both the heptamer and the nonamer are involved. The nonamer is protected, with extensive protein contacts within the minor groove. Conversely, the heptamer is rendered more accessible to chemical attack, suggesting that binding of RAG1 plus RAG2 distorts the DNA near the coding/signal border.

Functional immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor genes are assembled in early B- or T-cell development by recombination events collectively termed V(D)J recombination (18, 36). The V, D, and J gene segments are flanked by recombination signal sequences (RSS) that are composed of highly conserved heptamer and nonamer motifs separated by a relatively nonconserved spacer of 12 or 23 bp (2, 11). All segments of one class (V, D, or J) are flanked by RSS of the same spacer length. Recombination preferentially takes place between RSS of different spacer lengths (the “12/23 rule”), thus directing assembly of functionally relevant gene segments (18).

The recombination reaction can be divided into two stages; first, double-strand breaks (DSB) are created at the border of the RSS and coding segment. Broken coding ends are covalently sealed in a hairpin structure while signal ends are blunt, 5′-phosphorylated molecules (25, 26, 31). In the second stage, the broken molecules are processed and ligated to form signal and coding joints. Signal joints are formed by precise ligation of signal ends in a head-to-head fashion. Coding ends are ligated imprecisely to form coding joints, thus introducing junctional diversity. The first stage of recombination is mediated by the lymphoid-specific genes RAG1 and RAG2 (22, 30). The later stages of the reaction require a number of factors, including many involved in DSB repair (14).

The RAG proteins together carry out the same cleavage reaction in vitro as is observed in vivo, introducing a DSB at the coding/signal border (20). This cleavage is generated in two steps. First, a nick is introduced at the 5′ end of the heptamer adjacent to the coding flank, leaving a free 3′ hydroxyl on the last nucleotide of coding sequence. In a second step, this 3′ hydroxyl attacks the phosphodiester bond between the coding sequence and the RSS of the opposite strand, leaving a blunt 5′-phosphorylated signal end and a coding end covalently sealed in a hairpin structure (20). Thus, the in vitro cleavage reaction faithfully reproduces the reaction intermediates observed in vivo. Cleavage mediated by RAG1 and RAG2 requires a divalent metal ion. When cleavage is carried out in the presence of Mg2+, a pair of signals are required (8, 39), with a 12/23 pair being cleaved preferentially. In contrast, cleavage in the presence of Mn2+ can occur at either site independently (20), although coordinated cleavage at the two signals can still occur (15).

Because RAG1 and RAG2 are sufficient to carry out site-specific cleavage in vitro, it was clear that one or both must recognize and bind the RSS. However, the issue of which proteins are required for specific RSS recognition has been controversial. From experiments using a one-hybrid assay in mammalian cells or surface plasmon resonance with purified proteins, it was concluded that RAG1 bound specifically to the nonamer of the RSS (7, 34) and that RAG1 subsequently recruited RAG2 to form the active cleavage complex (7). However, these experiments did not allow a direct measurement of binding affinity or specificity and did not permit a comparison of the binding properties of RAG1 and the RAG1-RAG2 complex with DNA. In contrast, a RAG1-RAG2-DNA complex active in V(D)J cleavage was observed by gel shift aided by chemical cross-linking (12), but in these experiments no binding of RAG1 alone was detected. Thus, the role of each RAG protein in RSS recognition remained unclear.

To distinguish between the functions of RAG1 and RAG2 in RSS recognition, we developed a gel retardation assay that allows direct comparison of the binding of RAG1 or RAG2 separately and together under conditions in which cleavage can occur. We show that RAG1 plus RAG2 bind to DNA with far greater sequence specificity than is exhibited by RAG1 alone. Although binding of RAG2 alone to DNA is not detected, the presence of RAG2 increases the extent of binding as well as the sequence specificity and stability of the complex. Footprint analysis indicates that both the heptamer and the nonamer are bound by the RAG1-RAG2 complex, with extensive protein contacts to the nonamer through the minor groove. Furthermore, this binding is associated with structural alterations of the heptamer DNA at the RSS/coding border.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins and oligonucleotide substrates.

All DNA manipulations were performed according to standard protocols (3). Murine RAG1 proteins R1 (RAG1 amino acids 384 to 1008, modified to include nine histidine residues and a human c-Myc epitope at the C terminus) and MR1 (a fusion of the maltose-binding protein to the N terminus of RAG1384–1008 and containing 9 histidine residues at the C terminus) were expressed in a baculoviral expression system and purified from SF9 cells over nickel columns, as described previously (20, 37). R1 was used for all experiments except as noted. Extracts from SF9 cells infected with a baculovirus not expressing RAG1 were prepared in parallel and failed to yield a gel shift. “Hin” mutants were generated by replacing the NcoI/SphI fragment at the 5′ end of RAG1384–1008 with a PCR fragment containing the desired mutation. Additional epitopes for purification are the same as in R1. Four separate mutants were generated: CLM1, R391L; CLM2, P329A; CLM3, R393L; and CLM4, a deletion of GGRPR, amino acids 389 to 393. The presence of the mutations was confirmed by sequencing. Recombinant baculovirus, was prepared by standard protocols (3) and purified as previously described (37). The murine RAG2 protein R2 contains amino acids 1 to 383 of RAG2 in conjunction with FLAG (13) and Myc epitopes and nine histidine residues at the N terminus. R2 was expressed in HeLa cells from recombinant vaccinia and was purified over FLAG and nickel columns as described previously (20). Purified proteins were stored in a buffer of 25 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-KOH (pH 7.0), 100 mM potassium glutamate, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride.

All oligonucleotide substrates were 5′ end labeled on the top strand with [γ-32P]ATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase according to standard protocols (3), unless otherwise stated. DNA substrates were constructed by annealing the synthetic oligonucleotides as described previously (5) except that a twofold excess of the unlabeled strand was included to insure that no unannealed labeled DNA was present. Heptamer and nonamer replacements and coding flank mutations were all made in the context of the 12 bp RSS (12-RSS) (VDJ100/101 [the positions corresponding to the heptamer and nonamer are underlined]): VDJ100, 5′GCTGCAGGTCGACCTGCACAGTGCTACAGACTGGAACAAAAACCAGGTCTC3′; VDJ101, 5′TGAGACCTGGGTTTTTGTTCCAGTCTGTAGCACTGTGCAGGTCGACCTGCAG3′. Sequences of the 23-RSS, 10-RSS, 14-RSS, and heptamer or nonamer replacement (or both) oligonucleotides were as described previously (5). The sequences of additional mutants are indicated in the figures and were made as replacements into VDJ100/101. Two different nonspecific competitor DNAs were used in these experiments. In VDJ156/157, the heptamer and nonamer sequences were replaced within the context of VDJ100/101 (the positions corresponding to the heptamer and nonamer in a complete RSS are underlined): VDJ156 (top-strand competitor), 5′GCTGCAGGTCGACCTGACGCCGTCTACAGACTGGACTGGCTCAGCAGGTCTC3′; VDJ157 (bottom-strand competitor), 5′TGAGACCTGCTGAGCCAGTCCAGTCTGTAGACGGCGTCAGGTCGACCTGCAG-3′. An oligonucleotide (VDJ176) with the same base composition as VDJ100 but with the nucleotides in random order (5′TCCACGAAGTCGCCCCTGTGGTTTAATCGCTTGTAGCGTGGTCTGGAAGTGC3′) was also used as competitor DNA. The results with VDJ176 and VDJ156 were essentially indistinguishable, and VDJ156 was used for most experiments except as noted.

Gel retardation assay.

The standard binding assay mixture contained 25 fmol of labeled substrate DNA in 22.5 mM MOPS-KOH (pH 7.0), 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 2.2 mM DTT, 50 mM potassium glutamate, 2% (vol/vol) glycerol (including carryover from the protein purification), 100 ng of bovine serum albumin per μl, and approximately 0.5 pmol (each) of purified RAG1 (R1, except as indicated) and RAG2 core protein in a 10-μl total volume. MgCl2 (1 mM) was added as the divalent metal ion unless otherwise stated. VDJ156 (2.5 pmol) (or VDJ176 where indicated) was included as unlabeled nonspecific single-stranded competitor. When substrate labeled in the bottom strand was used in the reaction, VDJ157 was used as the nonspecific single-stranded competitor DNA. Binding reactions were performed for 2 h at 25°C unless otherwise stated. Samples were cross-linked with 0.1% glutaraldehyde at 37°C for 10 min. To separate complexes by native electrophoresis, 1 μl of 0.05% bromophenol blue was added and the sample was separated on a 4 to 20% polyacrylamide gel (Novex) in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 4°C. Gels were visualized by autoradiography and quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) and ImageQuaNT software.

For antibody supershift experiments, binding reactions were carried out as described above with the addition of 0.1 μg of anti-Myc (AB-1; Oncogene Science) or anti-FLAG (M2; Kodak) antibody to detect RAG1 or RAG2, respectively. For determination of the status of the DNA in the bound complex, binding reactions were performed in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+ and subjected to native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The bound protein-DNA complex was crush eluted from the polyacrylamide in a buffer containing 0.3 M sodium acetate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 1 mM EDTA, treated with 50 μg of proteinase K per ml for 2 h at 55°C, and then extracted with phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitated. The resuspended DNA was then analyzed on a 10% acrylamide gel containing 7 M urea and 30% formamide, as previously described (5).

DNA footprinting.

Binding reactions were performed in a total volume of 30 μl of the buffer described above and included approximately 5 pmol (each) of RAG1 (MR1) and RAG2 protein, 0.25 pmol of substrate, and 25 pmol of nonspecific competitor DNA (VDJ156 and VDJ157 for top and bottom strands, respectively) and were incubated for 4 h at 25°C prior to cross-linking with 0.1% glutaraldehyde for 10 min at 37°C. CaCl2 (1 mM) was used as the divalent metal ion. Essentially indistinguishable results were obtained with R1 instead of MR1.

For dimethyl sulfate (DMS) protection footprinting, 5 μl of 100 mM DMS was added followed by a 1-min incubation at room temperature. The reactions were terminated with 2 μl of 1 M DTT and 1 μl of 0.05% bromophenol blue, and the protein complexes were separated by gel electrophoresis. The gel-purified DNA complex and the unbound substrate (also purified from the gel) were treated with 50 μg of proteinase K per ml at 55°C for 2 h, extracted with phenol-chloroform, and ethanol precipitated. Samples were then subjected to piperidine treatment (19) and analyzed on a 12% polyacrylamide sequencing gel.

Phenanthroline-copper (OP-Cu) footprinting in a gel slice was performed according to the procedure of Sigman et al. (32). Briefly, bound complexes were separated by gel electrophoresis after cross-linking, as described above, and gel slices, immersed in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), were mixed with 10 μl each of solution A (2 mM 1,10-phenanthroline and 0.45 mM CuSO4) and solution B (58 mM 3-mercaptopropionic acid). After a 5-min incubation at room temperature, reactions were terminated with 10 μl of 28 mM 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline in ethanol and 270 μl of a solution containing 0.3 M sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. The DNA was eluted overnight, treated as described above, and analyzed by gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS

Direct detection of RAG1 binding to DNA.

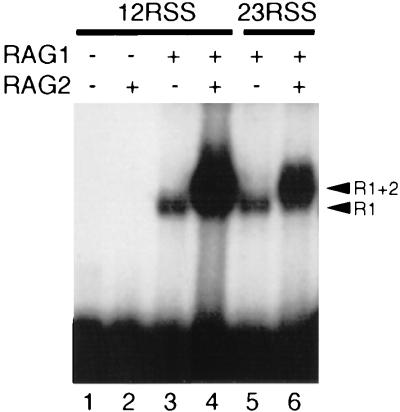

Core fragments of the RAG1 (amino acids 384 to 1008) and RAG2 (amino acids 1 to 387) proteins have been shown to be active in V(D)J recombination (6, 16, 28, 29, 33), and the isolated proteins are active for V(D)J cleavage (20, 37). To measure the DNA binding of RAG1 and RAG2, epitope-tagged core RAG1 and RAG2 fragments were purified to ∼90% homogeneity, as described previously (20, 37), and incubated with oligonucleotide substrates containing either a radioactively labeled 12- or 23-bp spacer signal (12-RSS or 23-RSS). Complete annealing of the oligonucleotide substrates was confirmed by electrophoresing the annealed substrate through a native gel. To further insure that all detectable binding was to double-stranded DNA, a 100-fold excess of cold nonspecific single-stranded DNA was included in all reactions. Incubation was carried out in cleavage reaction buffer with DMSO, and the mixture was subjected to glutaraldehyde cross-linking for 10 min prior to gel electrophoresis. A gel shift dependent on the presence of RAG1 was observed with both the 12- and 23-RSS substrates (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 5). The presence of RAG1 in the shifted complex was confirmed by supershifting with an antibody directed against an epitope tag on the RAG1 protein (data not shown). Under the same conditions, no binding of the RAG2 core was observed (Fig. 1, lane 2). Binding was also detectable without benefit of glutaraldehyde cross-linking, but the decreased intensity of the band from this shifted complex precluded further analysis (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Detection of RAG1-DNA and RAG1-RAG2-DNA complexes. The indicated RAG proteins were incubated in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+ with 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotide substrates containing a 12-RSS or a 23-RSS, as indicated. The samples were fixed with 0.1% glutaraldehyde and electrophoresed through a 4 to 20% native polyacrylamide gel. The positions of the RAG1 (R1) and RAG1-RAG2 (R1+2) gel shifts are indicated by arrowheads.

Successful detection of RAG1 binding by gel shift allows, for the first time, a direct comparison of the features of RAG1-DNA binding with those observed for RAG1 and RAG2 together. Moreover, because these binding conditions are compatible with the cleavage reaction (see below and reference 12), the specificity of the protein-DNA interactions detected here is likely to reflect those that occur during cleavage. As expected, coincubation of RAG1 and RAG2 with DNA yielded a band with lower mobility than RAG1 alone (Fig. 1, lanes 4 and 6). This lower-mobility species could be supershifted with antibody directed against distinct epitope tags on either RAG1 or RAG2, indicating that both proteins were present in the complex (data not shown). The species containing RAG1 and RAG2 was present in a substantially increased amount (5- to 10-fold) compared to the complex with RAG1 alone.

RAG1-RAG2 binds much more specifically than RAG1 alone.

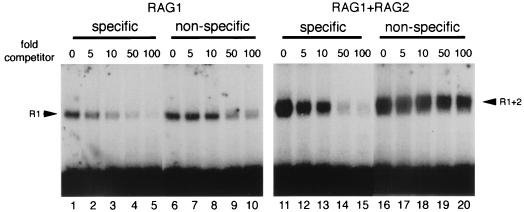

To compare the binding specificity of RAG1 alone with that of RAG1 and RAG2 together, nonradioactive specific and nonspecific substrates were used as competitors in the binding reaction (Fig. 2). Specific and nonspecific DNA competitors were required in ∼8-fold and ∼30-fold molar excess, respectively, to achieve a 40% reduction in RAG1 binding (Figure 2; compare lanes 1 to 5 and lanes 6 to 10). Thus, RAG1’s preference for DNA containing an RSS over nonspecific DNA is at most three- to fivefold. The binding of RAG1-RAG2 under the same conditions is highly sequence specific. In this case, a 5-fold excess of specific DNA competed much more effectively than a 100-fold excess of nonspecific competitor (Figure 2; compare lanes 12 and 20). Indeed, a 40% reduction in binding required ∼50- to 60-fold-more nonspecific than specific competitor DNA. Competition reactions were also performed in the presence of Ca2+ instead of Mg2+ to rule out possible effects on binding resulting from top-strand nicking. Comparable results were obtained with calcium (data not shown). In this case, sixfold-less specific (as compared to nonspecific) competitor was needed to achieve a 50% reduction in binding of RAG1 alone. In contrast, specific competitor was 60-fold more effective than nonspecific DNA in achieving the same reduction with RAG1 plus RAG2.

FIG. 2.

The sequence specificity of RAG1 plus RAG2 (R1+2) is much greater than that of RAG1 (R1) alone. A comparison of the binding competition with RAG1 alone (left) and RAG1 plus RAG2 (right) is shown. Binding reactions were carried out in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+ and the specified ratios of unlabeled competitor DNA to labeled substrate DNA. VDJ176 (see Materials and Methods) was included as unlabeled, nonspecific single-stranded DNA. Specific competitor (lanes 1 to 5 and 11 to 15) was formed by annealing VDJ100/101 (5), and nonspecific competitor (lanes 6 to 10 and 16 to 20) was constructed from VDJ156/157 (see Materials and Methods).

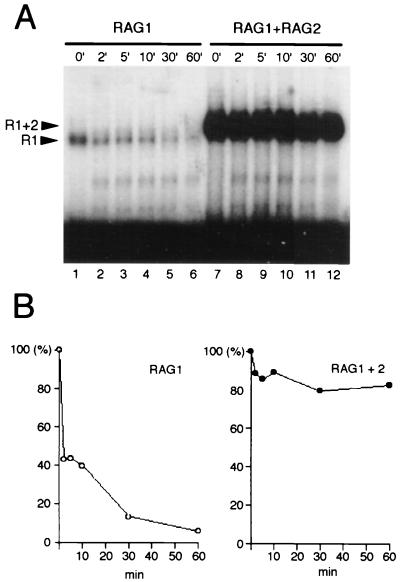

Corresponding to the very limited specificity seen with RAG1 binding, the association of RAG1 with DNA was very unstable, whereas the RAG1-RAG2-DNA complex was highly stable once formed (Fig. 3). Dissociation rates were compared by introducing a 1,000-fold molar excess of unlabeled specific competitor DNA to the binding reaction after complex formation. Incubations in the presence of competitor DNA were carried out for the times indicated (0 to 60 min) prior to cross-linking and gel electrophoresis. The amount of RAG1-DNA complex was reduced by half after only a 2-min incubation with cold competitor (Fig. 3A, lane 2, and Fig. 3B, left panel), whereas the RAG1-RAG2-DNA complex remained for an hour without noticeable dissociation (Fig. 3A, lane 12, and Fig. 3B, right panel). Indeed, more than 60% of the complex remained after an 8-h incubation (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Binding of RAG1 plus RAG2 (R1+2) is more stable than that of RAG1 (R1). (A) Dissociation of RAG1 versus RAG1 lus RAG2. RAG1 or RAG1 plus RAG2 proteins were allowed to bind to a labeled 12-RSS for 2 h at 25°C and then were challenged with a 1,000-fold excess of nonradioactive 12-RSS competitor for the times indicated before the addition of glutaraldehyde and subsequent electrophoresis. (B) Quantitation of dissociation over time. The gel from panel A was analyzed on a PhosphorImager, and the percentage of bound complex remaining at each time point is indicated.

DNA sequence requirements for binding.

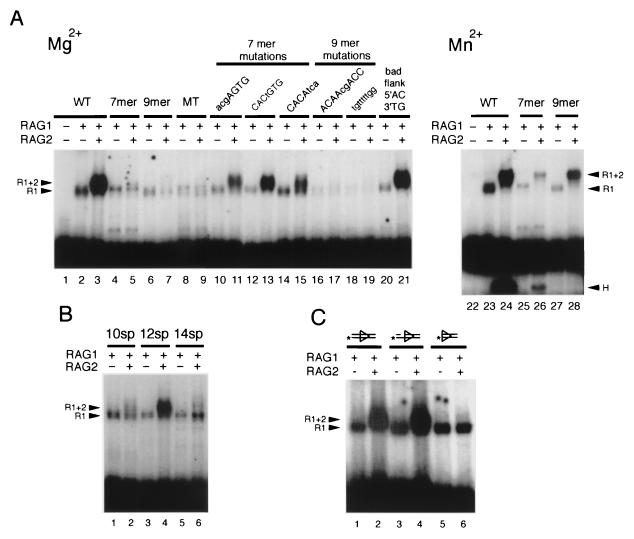

An alternative method for assessing the sequence specificity of binding is to compare the effects of mutating the recognition site. In keeping with the results described above, we found that the RAG1-RAG2 complex was sensitive to many alterations in the RSS, whereas RAG1 binding was minimally affected (Fig. 4). Little, if any, of the RAG1-RAG2 complex was formed when either the heptamer or the nonamer of the RSS (or both) was replaced with unrelated sequence (Fig. 4A, lanes 5, 7, and 9). Thus, both heptamer and nonamer sequences are required for optimal RAG1-RAG2 binding, consistent with previous observations (12). The gel shift corresponding to the binding of RAG1 alone is clearly visible even in the absence of the heptamer or nonamer sequences and is reduced only slightly from that seen with a wild-type RSS (Fig. 4A, lanes 4, 6, and 8). However, this reduction is reproducible, suggesting that preferential binding of RAG1 to DNA containing an RSS requires both heptamer and nonamer sequences. This binding of RAG1 alone is the residual signal remaining in the lanes containing RAG1 plus RAG2 and a mutant RSS (Fig. 4A, lanes 5, 7, and 9).

FIG. 4.

Binding of RAG1 (R1) or RAG1 plus RAG2 (R1+2) to mutant substrates. The binding of RAG1 and RAG1 plus RAG2 to substrates with the indicated mutations was examined. Reactions were performed in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+, except as noted. The presence of RAG1 or RAG2 is indicated at the top of each lane. (A) Effects of mutations in the heptamer or nonamer. WT, 12-RSS; 7mer, intact heptamer with nonamer replaced; 9mer, intact nonamer with heptamer replaced; MT, both heptamer and nonamer replaced. The sequences of other mutants are as noted. (B) RAG1-RAG2 binding is sensitive to changes in spacer length. 10sp, 12sp, and 14sp are RSS with spacers of 10, 12, and 14 bp, respectively. Reactions mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 25°C. (C) Effects of structural variations of the substrate. Lanes: 1 and 2, 12-RSS; 3 and 4, top-strand nick; 5 and 6, RSS with no coding flank. Substrates were labeled on the 5′ end of the bottom strand in panel C and on the 5′ end of the top strand for panels A and B.

Proper spacing of the heptamer and nonamer was also critical for RAG1 plus RAG2 binding but not for RAG1 alone. RAG1-RAG2 bound to signals with a 12- or 23-bp spacer but not to those with a 10- or 14-bp spacer (Fig. 4B and Fig. 1). While the binding of RAG1 plus RAG2 is less efficient (∼5-fold lower) with the 23-RSS than the 12-RSS, RAG1 appeared to bind to a 12-RSS and a 23-RSS with equal efficiency (Fig. 1, lanes 3 to 6). RAG1 also does not discriminate between substrates with spacers of 10, 12, or 14 bp (Fig. 4B).

Specific point mutations in the heptamer and nonamer sequences were also examined. The most highly conserved nucleotides in the heptamer are the first three (5′CAC3′), and mutations in these nucleotides severely decrease both recombination in vivo and cleavage in vitro (1, 11, 24). Mutation of these first three nucleotides did reduce binding of RAG1 plus RAG2 (Fig. 4A, lane 11) but not as dramatically as expected from their effects on cleavage in vitro and recombination in vivo. Mutations in the last three nucleotides also moderately decreased RAG1-RAG2 binding (Fig. 4A, lane 15), but the binding remained considerably better than in the absence of a heptamer, indicating that the residual correct nucleotides contribute to specific binding in the RAG1-RAG2 complex. Mutations in the nonamer had a more dramatic effect on RAG1-RAG2 binding (Fig. 4A, lanes 17 and 19). Mutation of the most highly conserved residues (As at the fifth and sixth positions in the nonamer) reduced binding to the essentially undetectable levels seen when the entire nonamer was replaced. Cleavage of substrates containing mutations in the nonamer was reduced to the level seen for a heptamer alone, indicating that the complex, once formed, was competent for cleavage (references 5 and 24 and data not shown). Thus, point mutations in the nonamer affect binding more severely than point mutations in the heptamer, whereas mutations in the heptamer have more dramatic affects on cleavage. Finally, the effect of coding flank alterations was examined. Binding of RAG1 plus RAG2 was not reduced in the presence of a “bad” flank (5′AC3′) (27) sequence (Fig. 4A, lane 21). This result is in keeping with the phenotype of bad flank cleavage in which hairpin formation is inhibited while nicking is not (5, 24). Thus, the flanking sequence would appear to affect DSB formation but not binding.

RAG1 binding was measured for the same mutations and was found to be largely unaffected, in keeping with RAG1’s limited ability to discriminate between specific and nonspecific sequences. The amount of RAG1-DNA complex formed with each mutant varied by no more than three- to fivefold from the wild-type binding (Fig. 4A). In addition, while RAG1-RAG2 requires the presence of a coding flank for binding, RAG1 does not (Fig. 4C, lanes 3 and 4). Both RAG1 alone and RAG1-RAG2 can bind to substrates containing nicked DNA (Fig. 4C, lanes 5 and 6).

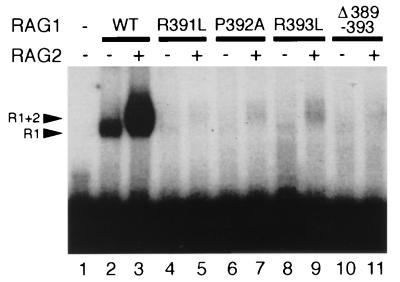

Mutations in the Hin domain disrupt binding of RAG1 and RAG1 plus RAG2.

Binding of RAG1 was previously shown to be impaired in mutants with single amino acid substitutions or complete deletions of a small region of RAG1 termed the “Hin” homeodomain, so called because of the region’s homology to the binding domain of the Hin bacterial recombinase (7, 34). We generated and tested similar mutants with this binding assay to quantitate the effects on RAG1 binding alone and the binding of RAG1 plus RAG2. Binding of three RAG1 derivatives with point mutations in the Hin domain (R391L, P392A, and R393L) was reduced to 1, 3, and 5% of wild-type levels, respectively (Fig. 5). Low levels of binding were previously detected for the R391L and R393L mutants (34). No binding was detectable when the GGRPR motif in the Hin domain was deleted. Comparable decreases were seen for the binding of RAG1 alone or RAG1 plus RAG2. A low level of cleavage was detected only for R393L (data not shown). While it is clear that mutations in this region abrogate binding, we cannot say whether these mutations are directly in the DNA binding domain or serve to grossly alter the protein structure so that it is unable to bind to DNA or to interact with RAG2.

FIG. 5.

Mutations in the Hin domain disrupt binding of RAG1 (R1) and RAG1 plus RAG2 (R1+2). Binding of core RAG1 (WT) and RAG1 mutant proteins was examined under standard reaction conditions (the concentrations of WT and mutant RAG1 protein were adjusted to 1 pmol per reaction). Point mutations and deletions, as indicated, are described in the text.

DNA is released after RSS cleavage at a single site.

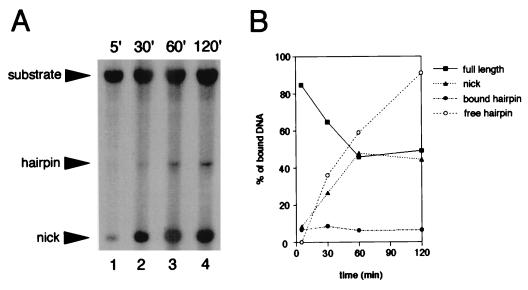

To examine the state of the DNA in the bound complexes for RAG1 alone and RAG1-RAG2, a time course of binding was performed and the DNA from the bound complexes was examined. Binding reactions were carried out in the presence of Mn2+ to permit cleavage to occur. The protein-bound DNA was gel-purified, and the extracted DNA was separated on a denaturing gel to allow the amount of intact substrate and nicked or hairpinned product to be determined. After a 5-min incubation with RAG1 plus RAG2, approximately 85% of the bound DNA was unprocessed, while 8% had been nicked (Fig. 6A, lane 1, and Fig. 6B). By 1 h, 50% of the bound substrate was processed and the amount of intact bound substrate (which should also include de novo binding) had been reduced. While the amount of free hairpin product (which migrates faster than the substrate) steadily increased, less than 7% of the DNA in the bound complex existed as the hairpinned product (Fig. 6B). The amount of bound hairpinned product remained largely constant throughout the time course, suggesting that the active complex quickly dissociates from an individual RSS after completion of the DSB. This observation is in keeping with other work (9, 12). As expected, DNA bound by RAG1 alone remained unmodified over the time course of the reaction (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

RAG1-RAG2 dissociates from DNA after cleavage. (A) The structure of the DNA from gel-purified RAG1-RAG2-DNA complexes was examined by denaturing gel electrophoresis. Binding reactions were allowed to proceed for the times indicated in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+ to permit cleavage. The positions of the substrate and nicked or hairpinned products are indicated. (B) Graphic representation of the percentage of each species of DNA present in the bound complex. Quantitation of the bands in the gel from panel A was performed on a PhosphorImager. In addition, the amount of hairpinned product migrating below the unbound substrate was determined and included in the graph as open circles (free hairpin). Quantitation of free hairpin is given as the relative amount of radioactivity in the hairpin form compared to the total amount of bound complex.

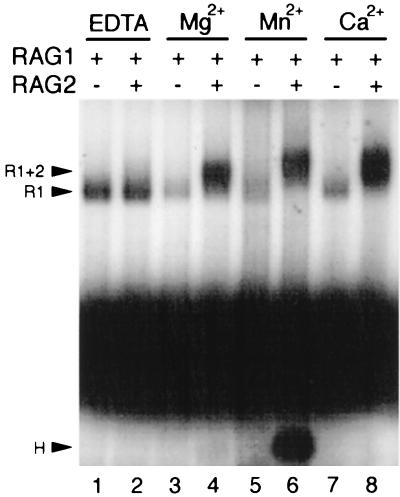

Differential effects of divalent metal ion on binding of RAG1 or RAG1 plus RAG2.

Because V(D)J cleavage requires the presence of a divalent metal ion, we investigated the divalent metal ion requirement for binding of RAG1 compared to RAG1 plus RAG2. In keeping with the requirements for cleavage, formation of the RAG1-RAG2 complex requires a divalent metal ion. Either Mg2+, Mn2+, or Ca2+ allows complex formation (Fig. 7, lanes 4, 6, and 8; see also cleaved product H in lane 6 and reference 12), although cleavage cannot occur in the presence of calcium (12). Five- to 10-fold-more RAG1-RAG2 complex is formed than with RAG1 alone regardless of the divalent metal ion included, indicating that this difference in binding is not a result of the nicking mediated by RAG1-RAG2 in the presence of Mg2+. The RAG1-RAG2-DNA complex in the presence of Mg2+ appears to migrate slightly faster than with Mn2+ or Ca2+ (Fig. 7 and Fig. 4A, right panel), possibly indicating that the composition or conformation of the RAG1-RAG2 complex is sensitive, to the particular divalent metal ion included in the reaction. Binding of the RAG1-RAG2 complex was abolished in the presence of 10 mM EDTA. In contrast, binding of RAG1 alone was not dependent on inclusion of a cation and was readily detected with 10 mM EDTA (Fig. 7, lane 1).

FIG. 7.

Effects of divalent metal ions on binding of RAG1 (R1) or RAG1 plus RAG2 (R1+2). Binding in the presence of different divalent metal cations is analyzed. Binding reactions were carried out at 25°C for 15 min in the presence of 10 mM EDTA (lanes 1 and 2), 1 mM Mg2+ (lanes 3 and 4), 1 mM Mn2+ (lanes 5 and 6), or 1 mM Ca2+ (lanes 7 and 8). The cleaved hairpin product (H) can be seen below the free substrate in lane 6.

The analysis of the effects of mutations on binding described in the previous section was carried out in the presence of Mg2+ to avoid the complication of protein dissociation occurring subsequent to double-strand breakage during the binding reaction. With Mn2+ as the divalent metal ion, the sequence requirements for RAG1-RAG2 complex formation appeared to be less stringent (Fig. 4A, right panel). When either the nonamer or heptamer sequence was replaced by nonspecific DNA, binding of RAG1 plus RAG2 was significantly greater with Mn2+ than Mg2+. (The apparent preference for binding to a substrate containing a nonamer alone versus a heptamer alone reflects the dissociation of RAG1 plus RAG2 after cleavage when a heptamer is present [as discussed above]). Site selection in other protein-DNA interactions is also known to be more specific in the presence of Mg2+ than of Mn2+ (17).

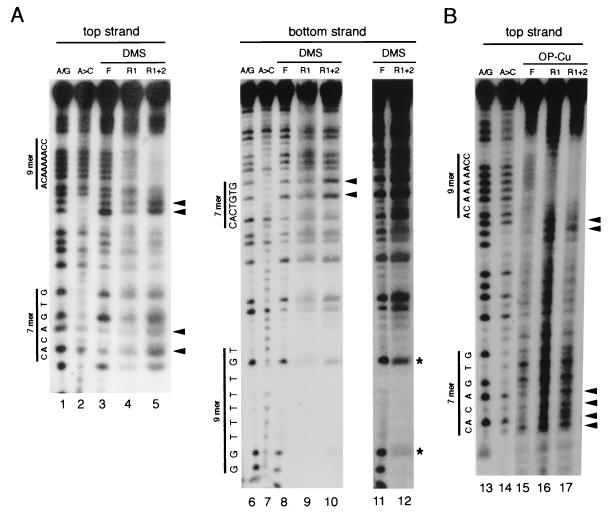

Footprinting analysis of RAG1-DNA and RAG1-RAG2-DNA complexes.

To see which nucleotides are recognized by the RAG complexes in detail, we carried out DMS protection and OP-Cu footprinting experiments (Fig. 8). Because only a small fraction of DNA is bound by RAG proteins, the RAG-DNA complexes were separated by gel electrophoresis prior to analysis. For DMS protection studies, complexes were formed in solution prior to treatment with DMS and then separated by gel electrophoresis. The gel-purified bound DNA was subsequently treated with piperidine. For the OP-Cu method, gel-purified RAG-DNA complexes were isolated prior to treatment with OP-Cu and then the products of that treatment were separated on a denaturing gel. Binding reactions were performed with Ca2+ as a cofactor to prevent substrate cleavage by the RAG proteins. Because, as indicated earlier, the sequence specificity in the presence of Ca2+ ion is similar to that observed with Mg2+, it is likely that the structure of complexes formed in the presence of Ca2+ ion represents the natural sequence specificity.

FIG. 8.

RAG1-RAG2 contacts the heptamer and the nonamer of the RSS. The binding of RAG1 (R1) and RAG1-RAG2 (R1+2) was analyzed by DMS protection and OP-Cu footprinting, as described in Materials and Methods. The RAG1 protein MR1 was used (see Materials and Methods). The positions of the heptamer and nonamer sequences are marked and the chemical sequencing ladder for A/G and A>C is shown. Sites of enhanced chemical cleavage are marked by arrowheads. (A) DMS protection. Top and bottom strands of 12-RSS oligonucleotides were labeled at the 5′ ends. The positions of the unprotected G residues are indicated by asterisks. Lanes 11 and 12 are longer exposures of lanes 8 and 10. (B) OP-Cu footprint. F, free substrate purified from the gel and treated in parallel with the bound complexes. R1 and R1+2 are the footprints of RAG1 and RAG1 plus RAG2, respectively.

The RAG1 plus RAG2 DMS protection pattern, with substrate labeled on the top strand, revealed a clear protection of the nonamer sequence and enhanced methylation of the first two nucleotides of the spacer region directly adjacent to the nonamer. The pattern suggests that the RAG1-RAG2 complex binds to the nonamer via the minor groove, where the A residues are methylated by DMS, and that binding renders nucleotides adjacent to the nonamer more susceptible to chemical modification. The RAG1-RAG2 footprint also showed enhanced methylation within the heptamer at the As in the second and fourth positions (Fig. 8A; compare lanes 3 and 5), suggesting that RAG1-RAG2 binding distorts the DNA in the region of the heptamer, making it more susceptible to attack by DMS. Analysis of the RAG1-RAG2 footprint on the bottom strand also shows enhancements of methylation in the heptamer (Fig. 8A, lane 10). Protection of this strand of the nonamer, which is comprised primarily of uncleavable T residues, is more difficult to detect. The G residues present within the nonamer are not strongly protected by RAG1-RAG2, consistent with the binding occurring primarily through the minor groove (Fig. 8A, lanes 10 and 12). The RAG1 DMS footprint reveals possible, but very weak, protection of the nonamer, in keeping with its limited ability to discriminate between specific and nonspecific sequences (Fig. 8A, lane 4).

The OP-Cu footprint is consistent with that obtained with DMS. Protection of the nonamer is again observed for the RAG1-RAG2-DNA complex (Fig. 8B; compare lanes 15 and 17). The OP-Cu footprint over the nonamer also indicates that the RAG1-RAG2 complex interacts with the nonamer at least through the minor groove, since the chemistry of the nuclease activity of OP-Cu is restricted to the minor groove (32). Again, the heptamer region showed enhanced cleavage.

DISCUSSION

Site-specific cleavage of an RSS is known to require only the RAG1 and RAG2 proteins, indicating that RSS recognition is mediated by one or both proteins without a requirement for additional factors. However, the functions of the two RAG proteins have remained inseparable, and the contribution of each RAG protein to catalysis or site-specific DNA binding has remained elusive. Site recognition is exceptionally demanding in this system because two different RSS sequences must be recognized. Here, we show that the individual proteins do not exhibit significant specificity, but the combination does. RAG1 binds to DNA with significantly less preference for an RSS than does RAG1 plus RAG2. The three- to fivefold preference for binding to DNA containing an RSS that is observed for RAG1 in our competition studies suggests that RAG1 has a limited ability to recognize an RSS (in keeping with other reports [7, 21, 34]) but is not able to successfully discriminate between specific and nonspecific sequences when the nonspecific targets are in even modest excess. While RAG1 is a contributing factor to RSS recognition, it is not sufficient on its own and the binding of RAG1 alone to DNA may not be biologically relevant.

The ability of RAG1 to only weakly discriminate between specific and nonspecific sequences (as shown here) is entirely consistent with earlier reports concluding that RAG1 specifically binds to the nonamer sequence of the RSS. First, the detection of RAG1 binding to an RSS via a one-hybrid assay required a minimum of eight RSS in a tandem array (7). The use of such a large array can overemphasize the specificity of binding, allowing a very minimal sequence preference to be detected. Second, surface plasmon resonance measurements of RAG1 binding (34) reveal an approximately two- to threefold sequence preference. While no equilibrium binding data is available, the initial slopes of the binding curves (association rates) indicate at most a twofold difference between the specific and nonspecific DNA sequences tested. The dissociation rates were identical for specific and nonspecific sequences, suggesting that there was only a twofold difference in binding constants. Third, following the initial submission of this paper, a report demonstrating a RAG1 footprint over the nonamer of the RSS was published. Even with a relatively poor ability to discriminate between specific and nonspecific sequences, it is still possible to have sufficient specific binding to allow detection of a footprint. Assuming that an RSS binding site is ∼30 bp, there would be approximately 25 nonspecific binding sites in a 54-bp oligonucleotide (i.e., 25 different positions within the oligonucleotide where the protein[s] could bind). Thus, to obtain the 3- to 5-fold preference for an oligonucleotide containing an RSS, as seen here, the protein would have 100-fold preference for the RSS over any individual 30-bp sites. Such a sequence preference is sufficient to give a specific footprint on a short DNA segment under appropriate conditions. However, such a limited ability to discriminate between specific and nonspecific sequences indicates that RAG1 by itself would be unable to distinguish an RSS within a complex genome. Biologically significant binding needs to be of sufficiently high affinity and avidity that a target site can be distinguished in the context of nonspecific DNA, and it appears that RAG1 alone fails this test.

Distinct roles of RAG1 and RAG2.

By direct comparison, the binding of RAG1 plus RAG2 is much more specific and stable than the binding observed for RAG1 alone. Under identical reaction conditions, RAG1 and RAG2 together are extremely sensitive to alterations in the RSS that affect RAG1 binding only marginally. And while RAG1 dissociates from DNA rapidly, the complex of RAG1-RAG2 remains stably bound to the RSS, being efficiently released only after cleavage of the DNA. The binding properties observed here for RAG1-RAG2 are generally consistent with the recent report of Hiom and Gellert (12). While, in that study, binding of RAG1 alone was not observed, differences in reaction conditions (e.g., concentration of competitor DNA) or protein preparations may explain this apparent inconsistency.

The specificity revealed by RAG1-RAG2 is largely the same as the specificity observed for the cleavage reaction. Both a heptamer and nonamer are required for the most efficient binding. A 12-RSS is more readily bound than one with a 23-bp spacer, and a 12-RSS is a better substrate for cleavage than a 23-bp signal. Variations from the canonical spacer length abolish binding, suggesting that proper spacing is critical for RAG1-RAG2 to contact both the heptamer and the nonamer. These binding studies also serve to underscore a distinction between the contribution of the heptamer and nonamer sequences to binding and cleavage. The first three nucleotides of the heptamer and the fifth and sixth positions of the nonamer are critical for V(D)J recombination in vivo (1, 11). While mutations in these positions lead to similarly poor recombination efficiencies in vivo, these essential nucleotides seem to be required for different reasons. The first three nucleotides of the heptamer are critical for cleavage (24) but not for binding (Fig. 4A) (12). In contrast, the nucleotides in the fifth and sixth positions of the nonamer are critical for the formation of a detectable bound complex but have comparatively little effect on cleavage of a single site in vitro (1a, 5). The relatively high protein and DNA concentrations used in vitro may explain why cleavage occurs despite unstable binding, whereas recombination in vivo is severely reduced. The relative importance of the nonamer for binding may be reflected in the strong footprint observed over the nonamer when both RAG1 and RAG2 are bound and in the observation that competition with a nonamer inhibits cleavage in vitro more significantly than the addition of competing heptamer (24).

Does RAG1 recruit RAG2?

It has been suggested that RAG1 binds to the RSS and subsequently recruits RAG2 to form the active cleavage complex (7). As discussed above, the minimal preference for an RSS exhibited by RAG1 is not compatible with RAG1 binding to an RSS within the context of a complex genome. The fast dissociation rate of RAG1 bound to DNA also makes it unlikely that the protein could remain stably bound and able to recruit RAG2. Because the buffer conditions used here to carry out the binding also support cleavage, they allow for a fair assessment of the binding specificity of RAG1 during the assembly of a cleavage complex in vitro. Indeed, preincubation of DNA with RAG1 prior to the addition of RAG2 increases the rate of binding and cleavage by at most 10% (1a). The fact that RAG2 does not bind an RSS on its own does not mean that it must be recruited by RAG1. For example, Fos oncoprotein is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein that can only bind its cognate sequence as a heterodimer with Jun (10). RAG1 and RAG2 may be arranged such that specific and tight binding requires them both to be interacting with the DNA at the same time.

Binding of RAG1 and RAG2 distorts DNA.

Coding ends produced in V(D)J cleavage are covalently sealed hairpin structures arising from a one-step transesterification in which the free 3′-OH on the top strand attacks the phosphodiester bond on the opposing strand (20, 38). The duplex DNA of the coding flank must become unpaired by the time the hairpin is formed, and a considerable kink is likely to be introduced to achieve the direct in-line attack required for the transesterification (see references 5 and 24). The work presented here demonstrates that the RAG proteins induce considerable distortion in the DNA. The enhancements of chemical cleavage observed in both the DMS and OP-Cu footprints are consistent with the DNA being distorted in the region of the heptamer as a consequence of RAG1-RAG2 binding.

There is additional evidence suggesting that DNA distortion plays an important role in V(D)J cleavage. First, unpairing of the first two nucleotides of coding flank DNA can dramatically increase the frequency of hairpin formation in situations where there is a bad coding flank sequence (5, 24). Second, the RAG proteins can specifically cleave an RSS which is entirely single-stranded, suggesting that some unwinding might naturally occur during cleavage (5, 24). Third, the CACA sequence of the heptamer is likely to have an unusual structure in which the DNA is partially unwound (4, 23, 35). Thus, it remains likely that access to RSS and therefore V(D)J recombination may be regulated by the state of DNA unwinding or the potential for local distortion. Importantly, the DNA distortion revealed in the RAG1-RAG2 footprint is a direct consequence of the binding of RAG1-RAG2, as it can occur in the absence of V(D)J cleavage. Thus, the ability of RAG1-RAG2 to distort the bound RSS and hence facilitate the hairpinning step is likely to be a major component of the catalytic activity of the RAG proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Cynthia Mundy, Heather Hunt, and Rhonda Feinbaum for generating the RAG1 mutant viruses and to Hui Su for excellent technical assistance. We thank Robert Kingston, Katsuya Shigesada, Kevin Struhl, and members of the Oettinger Lab for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Uehara Memorial Foundation (Y.A.) and by National Institutes of Health grant GM48026, the Leukemia Society Scholars Program, the Pew Scholars Program, and Hoechst AG.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akamatsu Y, Tsurushita N, Nagawa F, Matsuoka M, Okazaki K, Imai M, Sakano H. Essential residues in V(D)J recombination signals. J Immunol. 1994;153:4520–4529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Akamatsu, Y. Unpublished observations.

- 2.Akira S, Okazaki K, Sakano H. Two pairs of recombination signals are sufficient to cause immunoglobulin V-(D)-J joining. Science. 1987;238:1134–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.3120312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Wiley Interscience; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung S, Arndt K, Lu P. Correlation of lac operator DNA imino proton exchange kinetics with its function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3665–3669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuomo C A, Mundy C L, Oettinger M A. DNA sequence and structure requirements for cleavage of V(D)J recombination signal sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5683–5690. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuomo C A, Oettinger M A. Analysis of regions of RAG-2 important for V(D)J recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1810–1814. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.10.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Difilippantonio M J, McMahan C J, Eastman Q M, Spanopoulou E, Schatz D G. RAG1 mediates signal sequence recognition and recruitment of RAG2 in V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1996;87:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eastman Q M, Leu T M, Schatz D G. Initiation of V(D)J recombination in vitro obeying the 12/23 rule. Nature. 1996;380:85–88. doi: 10.1038/380085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grawunder U, Lieber M R. A complex of RAG-1 and RAG-2 proteins persists on DNA after single-strand cleavage at V(D)J recombination signal sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1375–1382. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.7.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halazonetis T D, Georgopoulos K, Greenberg M E, Leder P. c-Jun dimerizes with itself and with c-Fos, forming complexes of different DNA binding affinities. Cell. 1988;55:917–924. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hesse J E, Lieber M R, Mizuuchi K, Gellert M. V(D)J recombination: a functional definition of the joining signals. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1053–1061. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.7.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiom K, Gellert M. A stable RAG1-RAG2-DNA complex that is active in V(D)J cleavage. Cell. 1997;88:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81859-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopp T P, Prickett K S, Price V, Libby R T, March C J, Cerretti P, Urdal D L, Conlon P J. A short polypeptide marker sequence useful for recombinant protein identification and purification. Bio/Technology. 1988;6:1205–1210. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson S P, Jeggo P A. DNA double-strand break repair and V(D)J recombination: involvement of DNA-PK. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:412–415. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim D R, Oettinger M A. Functional analysis of coordinated cleavage in V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4679–4688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirch S A, Sudarsanam P, Oettinger M A. Regions of RAG1 protein critical for V(D)J recombination. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:886–891. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kornberg A, Baker T A. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman and Company; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis S M. The mechanism of V(D)J joining: lessons from molecular, immunological, and comparative analyses. Adv Immunol. 1994;56:27–150. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxam A M, Gilbert W. Sequencing end labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McBlane J F, van Gent D C, Ramsden D A, Romeo C, Cuomo C A, Gellert M, Oettinger M A. Cleavage at a V(D)J recombination signal requires only RAG1 and RAG2 proteins and occurs in two steps. Cell. 1995;83:387–395. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagawa F, Ishiguro K, Tsuboi A, Yoshida T, Ishikawa A, Takemori T, Otsuka A J, Sakano H. Footprint analysis of the RAG protein recombination signal sequence complex for V(D)J type recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:655–663. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oettinger M A, Schatz D G, Gorka C, Baltimore D. RAG-1 and RAG-2, adjacent genes that synergistically activate V(D)J recombination. Science. 1990;248:1517–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.2360047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel D J, Shapiro L, Hare D. NMR-distance geometry studies of helical errors and sequence dependent conformations of DNA in solution. In: Wells R D, Harvey S C, editors. Unusual DNA structures. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1987. pp. 115–161. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramsden D A, McBlane J F, van Gent D C, Gellert M. Distinct DNA sequence and structure requirements for the two steps of V(D)J recombination signal cleavage. EMBO J. 1996;15:3197–3206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roth D B, Menetski J P, Nakajima P B, Bosma M J, Gellert M. V(D)J recombination: broken DNA molecules with covalently sealed (hairpin) coding ends in scid mouse thymocytes. Cell. 1992;70:983–991. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90248-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth D B, Nakajima P B, Menetski J P, Bosma M J, Gellert M. V(D)J recombination in mouse thymocytes: double-strand breaks near T cell receptor δ rearrangement signals. Cell. 1992;69:41–53. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90117-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadofsky M, Hesse J E, van Gent D C, Gellert M. RAG-1 mutations that affect the target specificity of V(D)J recombination: a possible direct role of RAG-1 in site recognition. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2193–2199. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadofsky M J, Hesse J E, Gellert M. Definition of a core region of RAG-2 that is functional in V(D)J recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1805–1809. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.10.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadofsky M J, Hesse J E, McBlane J F, Gellert M. Expression and V(D)J recombination activity of mutated RAG-1 proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5644–5650. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.24.5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schatz D G, Oettinger M A, Baltimore D. The V(D)J recombination activating gene (RAG-1) Cell. 1989;59:1035–1048. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90760-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlissel M, Constantinescu A, Morrow T, Baxter M, Peng A. Double-strand signal sequence breaks in V(D)J recombination are blunt, 5′ phosphorylated, RAG-dependent, and cell-cycle-regulated. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2520–2532. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sigman D S, Kuwabara M D, Chen C H, Bruice T W. Nuclease activity of 1,10-phenanthroline-copper in study of protein-DNA interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1991;208:414–433. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08022-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silver D P, Spanopolou E, Mulligan R C, Baltimore D. Dispensable sequence motifs in the RAG-1 and RAG-2 genes for plasmid V(D)J recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6100–6104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spanopoulou E, Zaitseva F, Wang F H, Santagata S, Baltimore D, Panayotou G. The homeodomain region of Rag-1 reveals the parallel mechanisms of bacterial and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1996;87:263–276. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timsit Y, Vilbois E, Moras D. Base-pairing shift in the major groove of (CA)n tracts by B-DNA crystal structures. Nature. 1991;354:167–170. doi: 10.1038/354167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 1983;302:575–581. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Gent D C, McBlane J F, Ramsden D A, Sadofsky M J, Hesse J E, Gellert M. Initiation of V(D)J recombination in a cell-free system. Cell. 1995;81:925–934. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Gent D C, Mizuuchi K, Gellert M. Similarities between initiation of V(D)J recombination and retroviral integration. Science. 1996;271:1592–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Gent D C, Ramsden D A, Gellert M. The RAG1 and RAG2 proteins establish the 12/23 rule in V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1996;85:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]