1. Introduction

Heat-not-burn (HNB) tobacco products are entering the marketplace outside of the United States (U.S.; Caputi, 2016). HNB products heat tobacco leaf soaked in glycerol and propylene glycol to about 500 °F to create an inhalable aerosol (Caputi, 2016). Philip Morris’s (PM) HNB product named “IQOS” was initially on the market in Japan, Italy, Switzerland, and South Korea (Caputi, 2016) and is now available in 37 countries as of April 2018. British American Tobacco’s (BAT) HNB device named ‘Glo’ was released in Russia, Romania, Canada, Switzerland, Japan, and South Korea in 2017 (British American Tobacco - Developing less risky products, 2018). In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began reviewing Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) applications from PM in the summer of 2017 for the IQOS and other HNB products (Center for Tobacco Products, 2017), and BAT plans to submit an application for ‘Glo’ in 2018 (Chaudhuri, 2017). HNB products are internationally available and merit attention by public health researchers.

Health implications and prevalence of HNB use have not yet been thoroughly studied. Japanese and British researchers found about 1% to 2% of respondents reported ever use of HNB products in 2015 and 2017, respectively (Brose, Simonavicius, & Cheeseman, 2018; Tabuchi et al., 2016). It is likely that HNB use will increase as they become more popular in current and enter new markets. While the health consequences of HNB use are unknown, some research has examined HNB emissions. PM International’s (PMI) science website reports that IQOS aerosol has over 90% lower levels of harmful or potentially harmful constituents compared to cigarettes (Levels of HPHCs measured in Platform 1 THS 2.2 | PMI Science, 2017). Research not commissioned by PMI, found lower levels of most toxic compounds in IQOS emissions compared to cigarettes, but cautioned use due to significant emissions of several organic compounds (Ruprecht et al., 2017). Another health concern is the nicotine itself, which has been shown detrimental for the developing brain (England, Bunnell, Pechacek, Tong, & McAfee, 2015). While little is known about the prevalence and health consequences of HNB use, promotion of HNB products has yet to be examined.

Although HNB products have been introduced in a limited number of markets, their reach is likely transnational given promotion on the internet. Instagram is a mobile-based visual storytelling social media application that allows users to post photos and short videos that currently boasts more than 800 million international users (About Us Instagram, 2017; Jang, Han, Shih, & Lee, 2015). While HNB promotion has yet to be examined on Instagram, previous research has used Instagram’s Application Programming Interface (API) to collect data on posts that included hashtags associated with e-cigarettes, and examined differences in content between account types (Laestadius, Wahl, & Cho, 2016) and user interactions (Chu, Allem, Cruz, & Unger, 2016). Moreover, recent research has found an association between exposure to tobacco promotion on social media and tobacco use among adolescents (Hébert et al., 2017) and young adults (Unger et al., 2018). Given the potential behavioral influence of exposure to tobacco promotion on social media, it is important to understand how HNB content are shared on Instagram including health, cessation, flavors, and other messages pertaining to public health. Due to its visual storytelling capacity, Instagram is particularly well suited for examining both how people discuss and use HNB products in their photos compared to more text driven social media platforms. The proposed study will use Instagram’s API to examine image content of HNB posts, general textual topics and larger themes related to these textual topics, public health relevant topics, and different types of Instagram users who post HNB tobacco content.

2. Methods

Following previous research on e-cigarettes (Chu et al., 2016; Laestadius et al., 2016) and cigarillos/little cigars (Allem, Escobedo, Chu, Cruz, & Unger, 2017), data were gathered from the Instagram API using a hashtag keyword search term method. A list of hashtags related to HNB products was generated via a ‘snowball’ method (Goodman, 1961), which began with an API request for the hashtag #IQOS. Next, qualitative analysis of #IQOS results was used to generate more hashtag search terms until the research team deemed the list of useful terms were saturated. The final list of hashtags included: #IQOS, #Heatnotburn, #Heatstick, #IQOSBlack, #IQOSClub, #IQOSFamily, #IQOSFriends, #IQOSShop, #IQOSStyle, and #IQOSWhite. The Instagram API was queried with Netlytics, a third party social media API access tool that has been used in previous research (Allem et al., 2018; Gruzd, 2016). Individual hashtags were queried with a maximum rate of 10,000 posts and corresponding comments per request with one request every hour from September 27–October 4, 2017. Data from Instagram’s API included each post’s metadata, description, and comments. The authors’ university Institutional Review Board verified a review of study procedures was unnecessary as Instagram content are publicly published information.

The raw Instagram HNB hashtag dataset consisted of 15,471 posts and comments. After removing posts with dead links, the final number of posts and comments were 12,774, including 7027 with #IQOS, 254 with #Heatnotburn, 1256 with #Heatstick, 30 with #IQOSBlack, 208 with #IQOSClub, 3195 with #IQOSFamily, 338 with #IQOSFriends, 121 with #IQOSShop, 158 with #IQOSStyle, and 187 with #IQOSWhite. The proportion of retained posts and comments ranged from 3.2% to 92.6% per hashtag. Dates of publication ranged from May 23, 2016 - October 4, 2017. The final dataset included 4629 unique posts and 6402 unique users. Users outnumbered posts because some users only commented on other user’s posts rather than authoring posts. Posts were translated from their original language into English using the Google Cloud Translate API (Google Cloud Platform, 2018).

2.1. Analysis

The 10 most frequent words and public health relevant topics were found using R (R Core Team, 2017). Public health relevant topics were based on e-cigarette user perceptions and marketing messages (de Andrade, Hastings, & Angus, 2013; Willis, Haught, & Morris II, 2016). Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) was used for topic modeling, a mathematical algorithm for clustering words associated with topics (Silge & Robinson, 2017). Additionally, LDA has been found to adequately handle inconsistencies produced by Google Cloud Translate (Kuzar & Navrat, 2010; Liu, Boisson, & Chang, 2013). For the purposes of LDA analysis, each post was considered as one document. Text were cleaned by removing numeric values, symbols, stop words, and word stems (Bouchet-Valat, 2014). LDA analysis was conducted using the “TopicModels” package in R with ten topics specified (Silge & Robinson, 2017). Topics were discovered with an iterative method and to reduce additional noise in the LDA topics, a list of common non-relevant terms were removed (e.g. “iphone”) including each hashtag term used to query Instagram’s API. LDA topics were treated as codes from which larger themes were developed based on the grounded theory (GT) approach to text analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Specifically, Instagram posts with terms associated with each LDA topic were qualitatively analyzed to develop larger themes and find exemplar posts.

Inductive qualitative analysis of posts and user Instagram accounts were used to develop user types. Common terms used in posts and user names were used to differentiate types of users (see Table 1). After user types were coded, data were collapsed by user name and duplicate codes were checked. A total of 518 users were given two or more user type codes, these accounts were reviewed to determine their appropriate user type. Of the users given more than one user type, 61 users were unable to be verified and were dropped from user type analyses leaving a total of 6341 unique users.

Table 1.

Top ten most frequent words used in descriptions and comments (n = 12,774), prevalence of public health topics, and different types of users from Instagram posts with hashtags associated with Heat Not Burn tobacco products.

| Top words | Frequencies | Unique posts (n = 4629) |

|---|---|---|

| Smoke | 2363 | 633 (13.7%) |

| Cigarette | 2245 | 1056 (22.8%) |

| Electronic | 948 | 43 (0.9%) |

| Tobacco | 948 | 673 (14.5%) |

| Shop | 795 | 647 (14%) |

| Marlboro | 639 | 587 (12.7%) |

| Please | 593 | 462 (10%) |

| Japan | 571 | 633 (13.7%) |

| Bomb | 550 | 208 (4.5%) |

| Glo | 508 | 404 (8.7%) |

| Public health relevant topics | Terms | |

| Health | health; harmless; clean | 236 (3.7%) |

| Cessation | I-quit-original-smoking; I-quit-ordinary-smoking; stop; quit; smoke-free; better-than-cigarettes; not-burn; no-more-smoke | 47 (7.1%) |

| Smell | odor; stench; stink; smell | 423 (6.7%) |

| Convenience | use-everywhere; anywhere; convenience | 394 (6.2%) |

| Flavor | flavor; purple-menthol; aroma; taste; menthol; blueberry-flavor; flavorful | 554 (8.7%) |

| Type of user | Differentiating terms | Proportion of unique users (n = 6341) |

| HNB user | No terms | 2249 (35.5%) |

| IQOS retail employee | IQOSTeam; IQOSFamily | 251 (4%) |

| Fan community | No terms – use of “IQOS” in the account’s name | 32 (0.5%) |

| Online retailer | Whatsapp; sale; $; shipping; www; shop; available; cost | 3809 (60%) |

Note: Post descriptions and comments were collected from 4629 unique posts via Netlytic (Gruzd, 2016), a third party social media API access tool, between September 27th and October 2nd of 2017. Post publication dates ranged from May 23rd 2016 to October 4th 2017. Hashtags used to query Instagram’s API included #IQOS, #Heatnotburn, #Heatstick, #IQOSBlack, #IQOSClub, #IQOSFamily, #IQOSFriends, #IQOSShop, #IQOSStyle, and #IQOSWhite. The top 10 frequently used words were found using the “Tidytext” package in R. Authors were considered “HNB users” if they were not coded as a “IQOS retail employee”, “Fan community”, or “online retailer”, 61 authors were unable to be verified and were dropped from the user analyses.

For each individual post (n = 4629), image content including web-entities and labels were extracted as structured data using Google Cloud Vision API (GCV; Google Cloud Platform, 2018). GCV was used to complement the textual analyses and gain a general understanding of the content of the HNB related images posted on Instagram. GCV uses machine learning that improves in accuracy as more images are introduced to the API. Labels and web-entities are derived with “confidence scores” by comparison with other images used to train the API (labels) or hosted on Google Image Search (web-entities; Google, 2018). Label confidence scores are standardized (0 to 1), labels below 0.80 were dropped from the analysis, a cut-point used in previous research (Hyam, 2017). Web-entity confidence scores are not standardized, and a cut-point was not used. Instagram’s terms of use prohibit automated means of accessing content hosted on their platform (Instagram Inc, 2017). Therefore, we developed a method of manually taking screenshots of posts and uploading these images to the GCV API. The top ten categories of web-entities and identified labels were found using R (R Core Team, 2017). Posts identified as containing top image content categories were qualitatively analyzed to strengthen discussion of the results.

3. Results

3.1. Textual analysis

The top most frequent words related to HNB products included “tobacco”, “smoke”, “cigarette”, “marlboro”, and “Glo” (see Table 1). Public health relevant topic terms were found in 512 (11.1%) of posts. The 10 LDA topics were comprised of five words each and topic labels were chosen to best represent each cluster of words including “Style”, “Custom”, “Kid”, “Fashion”, “Glo”, “Marlboro”, “Shop”, “Japanese/Hong Kong”, “Accessories”, and “Sale” (see Table 2). The following themes were derived from qualitative analysis of posts with LDA topic text: “Appearance”, “Brand Names”, and “Marketing”.

Table 2.

Topic models and themes related to words used in descriptions and comments (n = 12,774) from Instagram posts with hashtags associated with Heat Not Burn products.

| LDA Topic Labels (%)a | Topic Text (n)b | Themes (%)c |

|---|---|---|

| Style (13.1%) | beautiful (273) love (356) heet (330) follow (204) fashion (438) | Appearance (34.8%) |

| Custom (11.1%) | decorate (49) cost (501) custom (403) cute (220) seal (197) | Appearance |

| Kid (14.2%) | kid (239) blah (130) smoke (2363) cool (244) bag (178) | Appearance |

| Fashion (17.7%) | supreme (179) fashion custom color (412) please (593) | Appearance |

| Glo (30.4%) | smoke tobacco (948) cigarette (2245) laugh (383) glo (508) | Brand Names (33.6%) |

| Marlboro (26.6%) | smoke bomb (550) marlboro (639) cigarette green (155) | Brand Names |

| Shop (16.4%) | shop (795) sticker (334) hangover (204) philipmorris (341) hangoversmartskin (152) | Marketing (39.3%) |

| Japanese/Hong Kong (16.8%) | japanese (344) kong (362) hong (360) shop glo | Marketing |

| Accessories (17%) | smoke clean (329) charger (168) marlboro kit (249) | Marketing |

| Sale (26.9%) | cigarette smoke sell (456) electronic (948) sale (475) | Marketing |

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) was used for topic modeling with the “TopicModels” package in R with 10 topics specified and 5 words per topic. Labels were chosen to best represent each topic’s texts. The percentage reported are number of unique posts (n = 4629) that include at least one of the topic’s text. The percentages are not independent because texts repeat across LDA topics and do not sum to 100.

Numeric value in parentheses represent frequency the word appeared in the HNB Instagram dataset not necessarily the number of posts that included the word (words can repeat per post). To simplify, frequencies were not repeated for the same word across multiple LDA topics (e.g. smoke).

LDA topics were treated as codes from which themes were developed with Grounded Theory analysis of posts including the topics’ texts. The percentage represents the proportion of all posts with at least one text from the theme. Because texts repeat between themes (e.g. “smoke” is in all three themes) the percentages do not sum to 100.

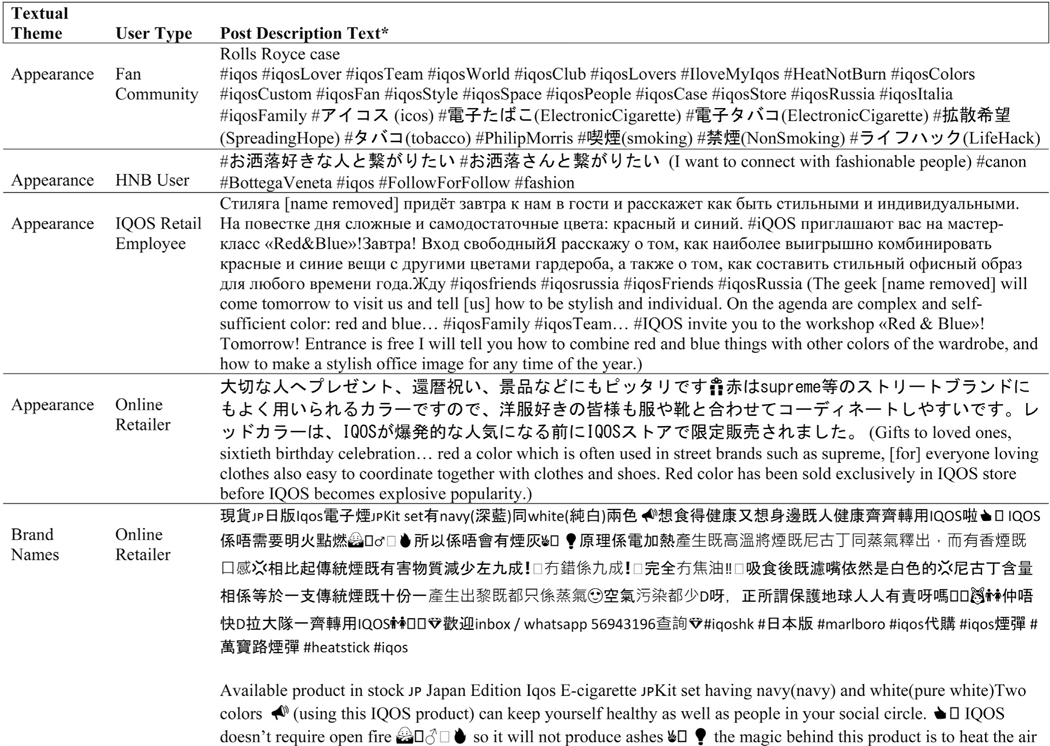

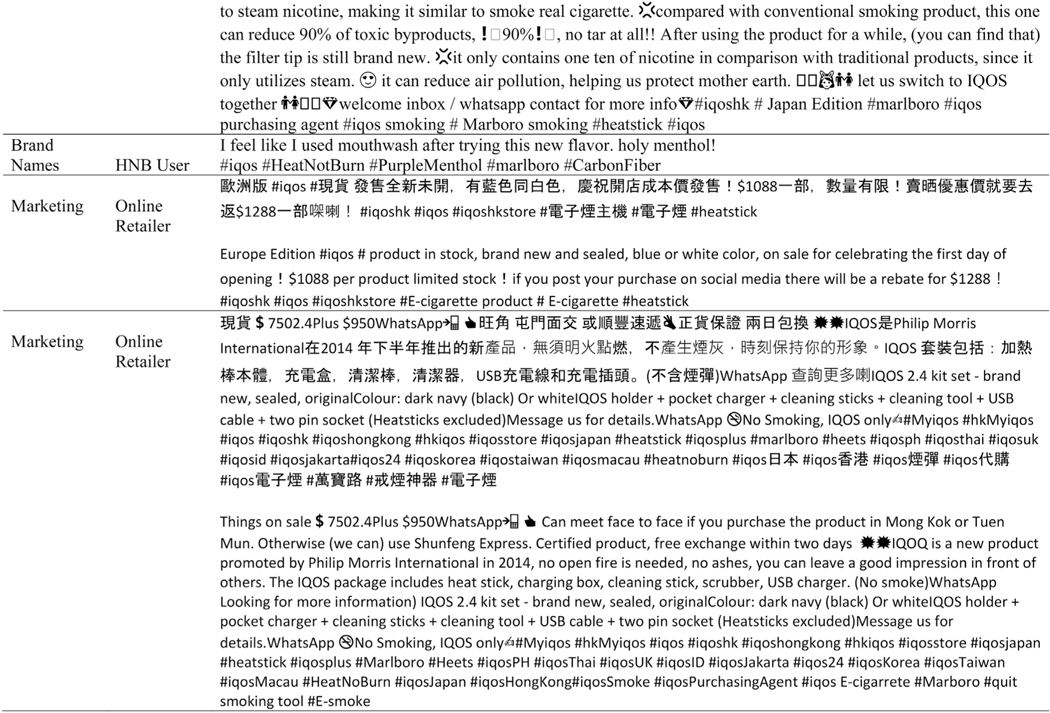

Posts under the “Appearance” theme included words clustered in the LDA topics “Style”, “Fashion”, “Kid”, or “Custom” (see Table 2). Under this theme, users posted about fashion choices, including pairing clothes with different HNB components including colored caps and device skins (decorative stickers). For instance, after reviewing posts with “#kid”, it was clear this hashtag referred to a specific brand of HNB skins. In addition to skins, users posted customized accessories, such as HeatStick (rolled tobacco leaf used in IQOS) cases, bags, and ashtrays to reflect their interests beyond tobacco use and contribute to a stylized aesthetic associated with HNB products on Instagram. One such post featured a matching IQOS case and ashtray decorated with a luxury vehicle brand skin (see Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S1). This post was generated by a self-described IQOS “fan community” account that frequently posted images of IQOS cases adorned with designer clothing brands, marijuana, cartoons, makeup, and videogames. Moreover, hashtags were used as a means of associating HNB products with “#luxury” and “#superiority”. For example, an account that solely posted images of cartons of HeatSticks used terms including “#cabaret”, “#sex”, “#status”, and “#boast”. In sum, the “Appearance” theme featured posts of customized HNB products indexed under fashion products on Instagram.

Table 3.

Exemplar heat not burn instagram posts’ description text by textual theme and user type.

|

|

The LDA topics labeled, “Japanese”, “Sale”, “Accessories”, and “Shop” were included under the larger theme entitled, “Marketing” (see Table 2). These posts were characterized with sales, retailers’ contact information and location, or a combination of these. Hashtags were commonly used to indicate a shop’s national location such as “#IQOSPhilipines” and “#MarlboroIqosPhilippines” which enabled other users looking to purchase HNB products to easily find retailers (see Table 3). Descriptions in these posts were used to promote pricing and accessibility with terms like “ship free within Italy”. Location was important for signifying the quality of product or local pride such as “the Japanese version IQOS” or skins “made in Italy” (see Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S1). To summarize, a unifying component of the “Marketing” theme was the use of Instagram posts to generate sales of HNB devices and accessories.

The “Brand Names” theme was developed from the LDA topics “Glo” and “Marlboro” (see Table 2). This theme was comprised of more generic HNB product terms than the other themes. Often these posts were used to showcase or critique HNB products. For example, one HNB user posted an image of their IQOS next to a carton of purple menthol and described the flavor (see Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S1). Other posts compared HNB products to cigarettes and suggested HNB were useful for smoking cessation. Posts associated HNB with a healthy lifestyle and reiterated the 90% reduction in harmful constituents, a finding touted by PMI (see Table 3). Other posts under this theme included curated images of HNB products with various products, models, and locations. These posts overlapped with the “Appearance” theme, but hashtag terms used in the “Brand Names” were used to attract HNB users and more related to tobacco content than fashion. Overall, posts under the “Brand Names” theme were more general than the other two themes and used to describe HNB products rather than sell or associate with other content on Instagram.

3.2. Visual content analysis

GCV analysis, conducted in February 2018, identified 1274 labels and 4473 web-entities among 3963 posts (666 posts were unable to be analyzed). The identified label categories were more generic than web-entities. For example, the most common label “product” is a broad class of object that may include posts with products other than HNB (e.g. smartphones) while the most common web-entity was “IQOS” (see Table 4). However, there was some overlap between labels and web-entities. For instance, “product” was identified in 753 posts as a label and 1046 posts as a web-entity, 41.2% of the posts labeled as “product” were also considered a “product” web-entity. Therefore, it was useful to refer to both labels and web-entities to get an overall feel of the variety of image content in our Instagram HNB hashtag dataset.

Table 4.

Top ten most frequent web entities and labels detected within the visual content of Instagram posts with hashtags associated with Heat Not Burn tobacco products (n = 4629).

| Top web entities | n(%) | Mean confidence (min, max)a | Top labels detected | n (%) | Mean confidence (min, max)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQOS | 1078 (23.3%) | 1.4 (0.2, 5.6) | Product | 753 (16.3%) | 84.4% (80%, 94.1%) |

| Product | 1046 (22.6%) | 0.6 (0.2, 0.9) | Electronic device | 261 (5.6%) | 86.1% (80%, 92.3%) |

| Heat-not-burn-product | 886 (19.1%) | 0.7 (0.2, 0.9) | Technology | 249 (5.4%) | 85.7% (80%, 92.8%) |

| Product design | 859 (18.6%) | 0.7 (0.2, 0.9) | Fashion accessory | 105 (2.3%) | 85.3% (80.2%, 92%) |

| Design | 812 (17.5%) | 0.5 (0.1, 0.9) | Text | 114 (2.5%) | 90.8% (85.1%, 97.3%) |

| Tobacco | 634 (13.7%) | 0.6 (0.2, 0.7) | Purple | 108 (2.3%) | 87.1% (80%, 96%) |

| Electronic cigarette | 617 (13.3%) | 0.6 (0.2, 0.9) | Social group | 107 (2.3%) | 93.3% (89.2%, 97.8%) |

| Cigarette | 389 (8.4%) | 0.6 (0.2, 0.9) | Beauty | 107 (2.3%) | 88% (85.1%, 95.6%) |

| Marlboro | 360 (7.8%) | 0.6 (0.2, 0.9) | Blue | 102 (2.2%) | 96.8% (96.8%, 96.8%) |

| Font | 367 (7.9%) | 0.6 (0.1, 0.9) | Photography | 86 (1.9%) | 82.4% (80%, 99.2%) |

Note: Visual content including web entities (information about the post’s image based on other images on the internet) and identified labels (e.g. objects) were analyzed using Google Cloud Vision API in February 2018. The top ten web entities and labels detected were found using the “Tidytext” package in R.

Web entity confidence scores are unstandardized and do not represent a percentage of confidence.

Label confidence scores are standardized between 0 and 1 and represent percent confidence. A cut point was used to restrict the top labels to those at or above 80% confidence.

Results of the visual content analysis generally corresponded with the textual analysis (see Table 4). For example, 34.9% of posts with the word “electronic” were identified with the “electronic cigarette” web-entity. Further, 59% of images labeled as “fashion accessory” had at least one word associated with the appearance text theme. Most web-entities and tags identified refer to HNB products. For instance, an image of a HNB device was categorized as “IQOS”, “cigarette”, “marlboro”, “product”, “product design”, “technology”, “gadget”, “heat-not-burn tobacco product”, “tobacco”, and “electronic cigarette”. Additionally, the labels “purple”, “text”, and “blue” and the web-entity “font” refer to the prominent colors and text on IQOS packaging. The “electronic cigarette” web-entity referred only to posts with HNB products not other types of e-cigarettes (e.g. disposable e-cigarettes). Additionally, “technology”, “electronic device”, and “electronics” were commonly identified in posts solely with HNB products. The “beauty” label encompassed posts of selfies and images of females modeling HNB products. The “social group” category included friends displaying HNB products or at IQOS sponsored events. “Photography” labeled posts featured groups of friends with a stylized filter on the image.

In sum, the top web-entities identified by GCV API identified more specific content associated with HNB products while the top labels were more broad categories associated with HNB products. Further, most content categories identified were descriptive of characteristics of HNB products in general terms (e.g. “design” and “tobacco”) while other categories were more specific such as “purple”.

3.3. Types of users

Qualitative and textual analyses of 6341 unique users identified general posting behavior of the following user types: HNB user (n = 2249), IQOS retail employee (n = 251), fan community (n = 32), and online retailer (n = 3809). HNB users posted images of themselves and customized IQOS devices with hashtags to describe the brand of skin and HNB device. IQOS retail employees posted images of models or themselves modeling, IQOS sponsored events, and of themselves working at kiosks selling IQOS with terms such as “IQOSTeam” (see Supplementary Fig. S1). With no official manufacturer accounts observed, these users acted as content creators on behalf of the HNB manufacturer. Fan community accounts posted images of HNB cases in various locations and adorned with a variety of designs. These users primarily reposted curated stylized images of people using HNB devices paired with vehicles, alcohol, luxury items, food, and models. Online retailers used hashtag terms to market and associate their accounts and HNB devices within broad categories of content on Instagram including luxurious, fashionable, and customizable products. These accounts typically posted images of HNB devices or accessories for sale with contact information and prices.

The prevalence of health terms in posts among the different types of users included: 9.4% of fan community users, 4% HNB users, 3.6% online retailers, and 2.8% IQOS retail employees. Similarly, 8.3% of HNB users, 6.5% of online retailers, 6.3% of fan communities, and 3.6% of IQOS retail employees posted terms associated with smoking cessation. The prevalence of users who posted regarding the smell of using HNB products was relatively even across user types including 6.9% of HNB users, 6.7% of online retailers, 6.3% of fan communities, and 4.8% of IQOS retail employees. Finally, the convenience of HNB products was emphasized by 7.4% of HNB users, 6.3% of fan communities, 5.8% of online retailers, and 1.6% of IQOS retail employees.

Among only users who posted using public health relevant topic terms, the proportion of posts corresponded with the prevalence of the user type in our dataset. For example, online retailers, who make up 60% of users, consistently represented about 60% of users who posted under each public health topic followed by HNB users (about 36%), IQOS retail employees (about 3%), and fan communities (about 1%). Thus, while the proportion of users posting with public health relevant terms may be similar across the different user types, the majority of posts with these terms were by online retailers and HNB users.

In summary, four types of users were identified in this study’s HNB Instagram hashtag network including: HNB user, IQOS retail employee, fan community, and online retailer. There were far more online retailers and HNB users than IQOS retail employees and fan community accounts represented in the HNB dataset and these users, due to their prevalence, accounted for the majority of posts with public health relevant topics.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the promotion of HNB products and we did so by studying HNB content on Instagram. Many of our results we expected: HNB users posted images of their HNB devices on Instagram and fan communities were dedicated to posting images of HNB devices. However, textual and GCV analyses of HNB posts on Instagram helped us to discover a popular aspect of HNB devices are the ability to customize the HNB cases, tips, and skins and the framing of these devices as fashion accessories. Moreover, the GCV label categories “social group”, “beauty”, and “photography” indicate HNB posts feature stylized images of friend groups and models that suggest social acceptability and normalcy of HNB products. Further, a large proportion of users posting about HNB devices are online retailers who use Instagram as a vehicle to reach potential customers and sell HNB devices and accessories. While not very widespread (about 4% to 7% of posts), online retailers and HNB users promoted HNB devices as convenient, healthy, less smelly, flavorful, and for smoking cessation. These public health relevant topics, commonly used in e-cigarette marketing, indicate early perceptions among users and marketing messages used among retailers that are important for tobacco control efforts. In addition to accessibility of HNB products via Instagram, youth exposure to messages that normalize and tout HNB products as healthy alternatives to smoking is concerning as these products become more available.

The present study extends previous research with analysis of visual content, textual topics and themes, public health relevant topics, and types of users associated with HNB content on Instagram. For example, Allem et al. (2018) found a large proportion of e-cigarette liquid posts on Instagram were by manufacturers (67.8%), similar to HNB online retailers in the current study (60%). Chu et al. (2016) identified “advertisement”, defined as “…a professional photo edited with embedded text of a company name”, as a common theme of e-cigarette Instagram posts. This theme is like retailer posts categorized under the current study’s theme “Marketing” that featured retailer contact information pasted over an image of a HNB device. Moreover, the “Appearance” theme and the GCV label “fashion accessory” in this study are similar to LDA discovered topics named “Fashion/beauty” and “Product” from a corpora of general Instagram posts collected in 2015 (Jang et al., 2015) and fashion has been described as a general category of posted content on Instagram (Hu, Manikonda, & Kambhampati, 2014). “Appearance” themed posts from “fan communities” and “IQOS retail employees” were indexed under a general Instagram theme to attract users who may not seek tobacco related content on Instagram.

Should the FDA’s Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) secretary determine the IQOS as a MRTP, PM will be able to market the IQOS as less harmful than cigarettes, a sentiment already shared by users on Instagram (see Table 3). It is important to surveil the influence of HNB promotion messages found in this study on vulnerable populations such as adolescents. Instagram has a large proportion of young users and the terms of use allow users 13 years and older (Instagram Inc, 2017; Jang et al., 2015). Of primary concern is exposure to HNB promotions may influence use of these products by youth and transitions to combustible tobacco use, as has been found among adolescent e-cigarette users (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016; Wills et al., 2016).

4.1. Limitations

Data were collected for this study using Instagram’s API. It is unclear what proportion of all published posts, that included the hashtags used to query Instagram’s API, were collected and posts with more than one of the hashtags may have been included in the LDA analysis multiple times. Therefore, generalizability of this study’s findings is influenced by an unavoidable limitation of collecting data through Instagram’s API, which has been severely restricted since June 2016 (Emersonthis, 2016). Further, the user type categories are not exhaustive and there could be other types of users who post HNB content such as friends of HNB users. However, our study’s sampling and analysis methods have been used in previous research specifically for examining tobacco promotion on Instagram (Allem, Chu, Cruz, & Unger, 2017). In sum, we are confident our data included a variety of HNB content on Instagram and the analyses were sufficient for our study’s purpose.

4.2. Conclusions

HNB are the newest class of tobacco product that may be appealing to the core demographics of Instagram users - young, interested in style/fashion, and active consumers (Jang et al., 2015). Our study demonstrated, HNB promotion on Instagram is overwhelmingly online retailer and HNB user generated buoyed by fan communities and IQOS employees (Richardson, Ganz, & Vallone, 2015). The prevalence of online retailers, indexing HNB under style/fashion categories, and use of health, flavor, and cessation terms are important to consider when these products enter the U.S. market as underaged youth may have access to HNB products and exposure to biased messaging through Instagram. Moreover, exposure to tobacco content on Instagram may normalize tobacco products and increase the social acceptability of tobacco use (Chu et al., 2016). If not an outright ban, Instagram could limit exposure to tobacco content among users ages 13 to 18. Findings from this study should inform health promoters and surveillance among regulators to prevent circumvention of tobacco control regulations as has been found with other tobacco products (Allem, Ayers, Althouse, & Williams, 2016; Williams, Derrick, & Phillips, 2017).

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Heat not burn tobacco products are widely promoted on Instagram.

Posts associated HNB devices with a healthy lifestyle

Posts compared HNB devices with cigarettes and suggested use for smoking cessation.

Posts associated HNB products with ‘#luxury’, ‘#fashion’, and ‘#superiority’.

HNB textual themes included “Appearance”, “Brand Names”, and “Marketing”.

Role of funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.09.003.

Conflict of interest

None to declare

References

- About Us Instagram (2017). Retrieved November 13, 2017, from https://www.instagram.com/about/us/.

- Allem J-P, Ayers J, Althouse B, & Williams R. (2016). When a ban really is not a ban: Internet loopholes and Djarum flavoured cigarettes in the USA. Tobacco Control, 25(4), 489–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem J-P, Chu KH, Cruz TB, & Unger JB (2017). Waterpipe promotion and use on instagram: #Hookah. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(10), 10.1093/ntr/ntw329ntw329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem J-P, Cruz TB, Unger JB, Toruno R, Herrera J, & Kirkpatrick MG (2018). Return of cartoon to market e-cigarette-related products. Tobacco Control. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem J-P, Escobedo P, Chu KH, Cruz TB, & Unger JB (2017). Images of little cigars and cigarillos on instagram identified by the Hashtag #swisher: Thematic analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(7), e255. 10.2196/jmir.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade M, Hastings G, & Angus K. (2013). Promotion of electronic cigarettes: Tobacco marketing reinvented? BMJ, 347. 10.1136/bmj.f7473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Pentz MA, & McConnel R. (2016). E-cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics, 138(1), e20160379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchet-Valat M. (2014). SnowballC: Snowball stemmers based on the C libstemmer UTF-8 library. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/package=SnowballC. [Google Scholar]

- British American Tobacco - Developing less risky products (2018). Retrieved September 28, 2017, from http://www.bat.com/productrisk.

- Brose LS, Simonavicius E, & Cheeseman H. (2018). Awareness and use of “heat-not-burn” tobacco products in Great Britain. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 4(2), 44–50. 10.18001/TRS.4.2.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi TL (2016). Industry watch: Heat-not-burn tobacco products are about to reach their boiling point. Tobacco Control, 26(5), 609–610. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Tobacco Products (2017). Philip Morris IQOS modified risk tobacco product (MRTP) applications. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/MarketingandAdvertising/ucm546281.htm.

- Chaudhuri S. (2017). BAT to submit FDA application to sell Glo in U.S. - MarketWatch. Retrieved September 28, 2017, from http://www.marketwatch.com/story/bat-to-submit-fda-application-to-sell-glo-in-us-2017-07-27.

- Chu K-H, Allem J-P, Cruz TB, & Unger JB (2016). Vaping on Instagram: Cloud chasing, hand checks and product placement. Tobacco Control, 26(5), 575–578. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core Team R. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Emersonthis (2016, July). Instagram on websites: The new landscape since june 1st. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@emersonthis/instagram-on-websites-the-new-landscape-62c91d733894. [Google Scholar]

- England LJ, Bunnell RE, Pechacek TF, Tong VT, & McAfee TA (2015). Nicotine and the developing human: A neglected element in the electronic cigarette debate. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(2), 286–293. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA (1961). Snowball Sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. Institute of Mathematical Statistics. 10.2307/2237615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Google (2018). Google cloud vision API. google cloud platform. Retrieved from https://cloud.google.com/vision/. [Google Scholar]

- Google Cloud Platform (2018). Cloud APIs - access bigquery and compute engine | google cloud platform. Retrieved March 9, 2018, from https://cloud.google.com/apis/.

- Gruzd A. (2016). Netlytic: Software for automated text and social network analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert ET, Case KR, Kelder SH, Delk J, Perry CL, & Harrell MB (2017). Exposure and engagement with tobacco- and E-cigarette–related social media. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(3), 371–377. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Manikonda L, & Kambhampati S. (2014). What we instagram: A first analysis of instagram photo content and user types. Icwsm. Retrieved from https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM14/paper/viewFile/8118/8087. [Google Scholar]

- Hyam R. (2017). Automated image sampling and classification can be used to explore perceived naturalness of urban spaces. PLoS One, 12(1), e0169357. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instagram Inc (2017). Terms of use. Retrieved August 12, 2017, from https://help.instagram.com/478745558852511.

- Jang JY, Han K, Shih PC, & Lee D. (2015). Generation like: comparative characteristics in instagram. Proceedings of the 33rd annual ACM conference on human factors in computing systems - CHI ‘15 (pp. 4039–4042). New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. 10.1145/2702123.2702555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzar T, & Navrat P. (2010). Preprocessing of slovak blog articles for clustering. In web intelligence and intelligent agent technology (WI-IAT), IEEE/WIC/ACM international conference on 2010 aug 31. Retrieved from https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/5614178/. [Google Scholar]

- Laestadius LI, Wahl MM, & Cho YI (2016). Vapelife: An exploratory study of electronic cigarette use and promotion on instagram. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(12), 1669–1673. 10.1080/10826084.2016.1188958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levels of HPHCs measured in Platform 1 THS 2.2 | PMI Science. (2017). Retrieved September 28, 2017, from https://www.pmiscience.com/platform-development/platform-development/aerosol-chemistry-physics/hphcs/levels-hphcs-measured

- Liu Y-L, Boisson J, & Chang JS (2013). NTHU at NTCIR-10 crosslink-2: An approach toward semantic features. NTCIR. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/06c1/fbf529f4899deb409c13843527720b4b403e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Ganz O, & Vallone D. (2015). Tobacco on the web: Surveillance and characterisation of online tobacco and e-cigarette advertising. Tobacco Control, 24(4), 341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruprecht AA, De Marco C, Saffari A, Pozzi P, Mazza R, Veronese C, & Boffi R. (2017). Environmental pollution and emission factors of electronic cigarettes, heat-not-burn tobacco products, and conventional cigarettes. Aerosol Science and Technology, 51(6), 674–684. 10.1080/02786826.2017.1300231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silge J, & Robinson D. (2017). Text mining with R: A tidy approach. Book down. Retrieved from https://bookdown.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, & Corbin J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. Retrieved from http://www.li.suu.edu/library/circulation/Stein/Comm6020ksStraussCorbinBasicsQualitativeFall07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi T, Kiyohara K, Hoshino T, Bekki K, Inaba Y, & Kunugita N. (2016). Awareness and use of electronic cigarettes and heat-not-burn tobacco products in Japan. Addiction, 111(4), 706–713. 10.1111/add.13231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Urman R, Cruz TB, Majmundar A, Barrington-Trimis J, Pentz MA, & McConnell R. (2018). Talking about tobacco on Twitter is associated with tobacco product use. Preventive Medicine, 114, 54–56. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RS, Derrick J, & Phillips KJ (2017). Cigarette sales to minors via the internet: How the story has changed in the wake of federal regulation. Tobacco Control, 26(4), 415–420. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis E, Haught MJ, & Morris DL II (2016). Up in vapor: Exploring the health messages of E-cigarette advertisements. Health Communication, 1–9. 10.1080/10410236.2016.1138388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, & Williams RJ (2016). Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii. Tobacco Control, 0, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.