Abstract

Since the initial landmark study on the chiral induced spin selectivity (CISS) effect in 1999, considerable experimental and theoretical efforts have been made to understand the physical underpinnings and mechanistic features of this interesting phenomenon. As first formulated, the CISS effect refers to the innate ability of chiral materials to act as spin filters for electron transport; however, more recent experiments demonstrate that displacement currents arising from charge polarization of chiral molecules lead to spin polarization without the need for net charge flow. With its identification of a fundamental connection between chiral symmetry and electron spin in molecules and materials, CISS promises profound and ubiquitous implications for existing technologies and new approaches to answering age old questions, such as the homochiral nature of life. This review begins with a discussion of the different methods for measuring CISS and then provides a comprehensive overview of molecules and materials known to exhibit CISS-based phenomena before proceeding to identify structure–property relations and to delineate the leading theoretical models for the CISS effect. Next, it identifies some implications of CISS in physics, chemistry, and biology. The discussion ends with a critical assessment of the CISS field and some comments on its future outlook.

1. Introduction

Since the time of Louis Pasteur, chiral symmetry and chiral molecules have intrigued chemists. Chiral molecules exist as stereoisomers, termed enantiomers, that are nonsuperimposable mirror-image structures of each other, like right and left hands. While the chemical formula and atomic connectivity of enantiomers are identical, their three-dimensional structure is not and gives rise to distinctive interactions with circularly polarized light. Chiral molecules that appear in organisms (lipids, carbohydrates, nucleic acids, and proteins) are homochiral, and even though the chemical behavior of enantiomers is often very similar, their bioactivity is not. Although conventional wisdom considers changes in chemical behavior to arise from differences in shape (lock and key mechanism of binding and enzymatic function), the reasons for homochirality and what might have guided Nature’s choice of one enantiomer over the other in biomolecules have long intrigued chemists.1−3 Even more generally, one might ask, “Why is chirality, as such, preserved so persistently throughout evolution?” or “What makes chiral symmetry so important to life?” Answers to these questions could involve the relationship between chirality and the electron spin, which manifests as the chiral induced spin-selectivity effect (CISS). CISS refers to the connection between chiral symmetry and electron spin in molecules and materials and it can manifest for electron transmission and for electron displacement currents.

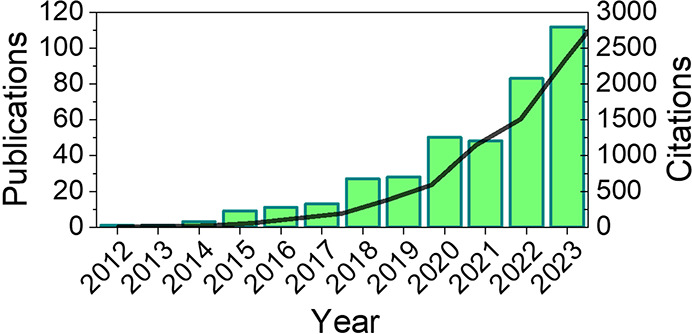

The idea that spin-polarized electrons scatter asymmetrically from chiral molecules was explored soon after the discovery of parity violation, i.e., the weak force breaks parity conservation, by Lee and Yang.4 However, studies with chiral molecules in the gas phase gave scattering asymmetries of A < 10–4, where A = (I+ – I–)/(I+ + I–) where I+ and I– are the intensities of the electron beam with spin angular momentum parallel and antiparallel to the velocity. In 1999, we showed that the asymmetry in photoelectron scattering is >100-fold larger, ca. 0.1–0.2, when the electrons traverse through an ordered film of chiral molecules.5 Subsequent studies, using the same approach, reproduced these findings for other chiral molecular adlayers.6−8 In 2006, Wei et al. first showed that the phenomenon manifests for electron transport in electrochemical tunnel junctions,9 and since that time a large number of tunnel junction measurements and proximal probe studies have observed spin-dependent electron transport through chiral molecules and ultrathin chiral films.10,11 In 2011, Göhler et al. used Mott polarimetry to measure the photoelectron spin distributions through films of duplex DNA and found spin asymmetries as high as 60%.12 A perspective/mini-review of this early work in 2012 helped spark interest in this phenomenon, which is now called the CISS effect.13 Over the past decade, the number of publications using the term chiral-induced spin selectivity, and their corresponding citations has grown considerably year over year (see Figure 1).

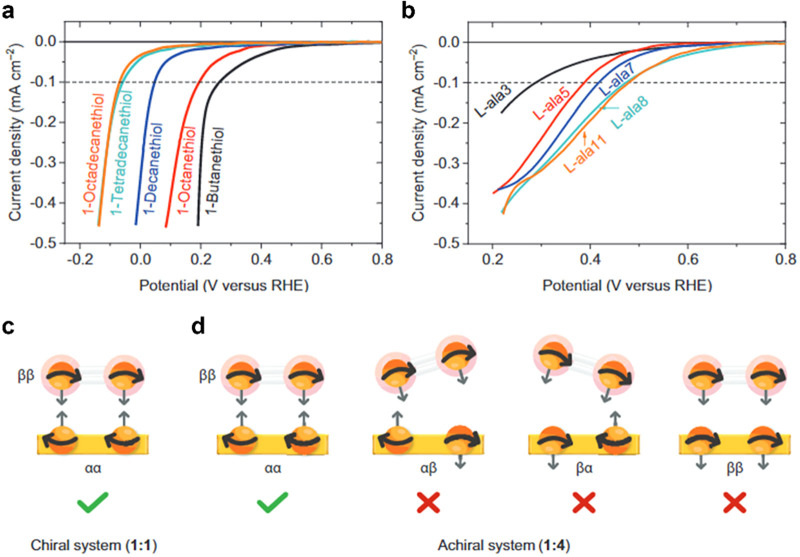

Figure 1.

Number of publications, and the citations of those publications, using the phrase “chiral induced spin selectivity” or “chirality induced spin selectivity” from 2012 to 2022. The bars show the number of publications each year, and the solid curve shows the cumulative growth in citations. Data are from Clarivate Web of Science.

This review aims to provide a more comprehensive description of the field and current understanding of CISS-related phenomena than that of reviews prior and comprises eight parts. In the next section we overview the different methodologies that have been used to measure the CISS effect, and then we follow with a section that summarizes the classes of molecules and materials shown to exhibit CISS. In Section 4, we identify general trends and inferences that can be drawn from particular experiments described in Sections 2 and 3, and in Section 5 we provide a brief assessment on the current status of theory, and its advances, since the review published in 2022.14 In Section 6, we describe some implications and applications of CISS for physics, chemistry, and biology. Lastly, we conclude with a critical assessment of the field (Section 7) and then offer some forward-looking sentiments (Section 8)

2. Methods for Measuring CISS

Direct experimental determinations of the CISS effect fall largely into two main measurement modalities: the observation of spin-dependent electron transport through chiral systems and the measurement of charge polarization-induced spin polarization of chiral systems. Transport/transmission measurements have been performed, both above the vacuum level (Section 2.1) and below the vacuum level (Section 2.2). While studies have attempted to calibrate the magnitude of the CISS-response across different measurement techniques,15 this process remains challenging because of differences in how the measurements are performed and how the CISS-response is quantified. In CISS studies the “spin polarization” has often been defined as the difference of measurables, for some process that selects for spin, divided by their sum. For example, the CISS literature often defines polarizations as normalized anisotropies in electron currents or charge transfer rate constants, and these quantities can be convoluted with the spin density of states. However, this treatment contrasts with classical definitions in which the spin polarization is formally given as the difference in populations for spin up and spin down electrons.16,17 Thus, care must be taken when comparing findings between different measurement techniques.

In addition to direct measurements, indirect probes for the CISS effect rely on the spin-selectivity of product formation in electrochemical reactions,18 or of charge polarization-induced spin polarization, and the complementary phenomenon of spin polarization-induced charge polarization, of chiral molecules and materials.19,20 In the latter case CISS has been shown to give rise to enantiospecific interactions, be they intermolecular or with ferromagnetic substrates,21,22 as well as spin-dependent charge delocalization.19 It is important to note that CISS is often a transient process,23,24 particularly as it pertains to enantiospecific interactions or measurements affected by decoherence, vide infra; therefore, measurement time scales are important for revealing spin selectivity.25,26 Below we summarize different measurement techniques that have been used to probe the CISS effect in chiral molecules and chiral materials.

2.1. Photoelectron Spectroscopy

Spin-resolved photoemission of electrons through chiral molecular films or ultrathin chiral materials is often considered the “gold standard” for quantifying the CISS effect because measurement of the electron spin population is not convoluted with charge displacement currents. These studies have provided insights into the importance of molecular helicity and length, as well as substrate spin–orbit coupling12,15,27−29 on the spin-dependent electron transmission. In cognate approaches, researchers have begun to explore CISS effects indirectly, e.g., through shifts in the substrate work function30,31 and through spin-dependent electron-induced chemical reactions.32

2.1.1. Mott Polarimetry

Mott polarimetry has historically been used for analyzing the magnetic characteristics of thin films33−35 and characterizing spin-polarized electron sources,36 among other applications.37,38 In this method electrons incident on a crystalline solid with large spin–orbit coupling (e.g., Au) scatter at different angles based on their spin orientation, and their angle dependent detection provides quantitative information about the spin population of the electrons. See ref (38) for a more detailed explanation and a historical perspective. For CISS studies, the typical process proceeds as follows: (i) electrons from a substrate, or a chiral material,39 are photoexcited, (ii) the photoelectrons transit through (from) a chiral layer where spin-filtering manifests, (iii) the photoelectrons are directed to a Mott polarimeter and spatially resolved according to their spin. The number of photoelectrons observed at the two detectors (gray spheres, iv) are used to determine the asymmetry or spin polarization, P (see Figure 2) through

| 1 |

where I+ and I– correspond to the intensity of photoelectrons measured at the two different detectors.

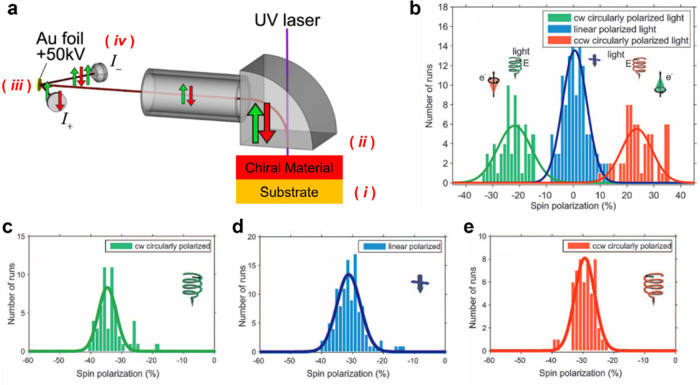

Figure 2.

Representative schematic diagram (a) for the determination of CISS using Mott polarimetry measurements. First, photoelectrons in a substrate are excited (i) and then transmit through the chiral spin filter (ii), resulting in a net spin polarization. The photoelectrons are scattered on an Au foil target according to their spin (iii) and quantified at two independent detectors (iv). The schematic is reproduced with permission from ref (39). Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. Panel b shows the photoelectron spin polarization from a bare Au(111) substrate excited with clockwise (green), linear (blue), and counterclockwise (red) polarized light. Panels c–e show the spin polarization for photoelectrons from an Au(111) surface that is coated with double-stranded DNA for clockwise, linear, and counterclockwise excitation, respectively. The data are adapted from ref (12) with permission. Copyright 2011 Science.

By way of example, consider an Au substrate. Excitation of an Au(111) surface with clockwise and counterclockwise circularly polarized light produces spin-polarized photoelectrons with equal, but opposite, polarizations, whereas excitation with linearly polarized light does not give rise to a net spin polarization (see Figure 2b).12 Conversely, when the substrate is coated with double-stranded DNA, the polarizations measured for clockwise (Figure 2c), linear (Figure 2d), and counterclockwise polarized light excitation (Figure 2e) was negative, owing to the CISS effect. Similar studies have been carried out showing the spin selectivity of other oligonucleotides,40 oligopeptides,15,40 metal oxides,39,41 and helicenes.28 For a recent review of CISS studies using Mott polarimetry, see ref (29).

2.1.2. Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy

The determination of CISS using ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) was first demonstrated by Weiss and co-workers for α-helical peptides immobilized on Co/Pt ferromagnetic substrates.30 Here, they measured changes in the photoelectron energies as a function of North and South magnetization of a Co/Pt substrate. A change in work function of ∼100 meV was observed and attributed to the spin-dependent exchange interactions occurring between the chiral molecules and the magnetized ferromagnetic substrate. Related studies on ferromagnetic substrates by Kelvin probe force microscopy have similar work function shifts.19 Because of the spin-selective electron delocalization of chiral molecules, the surface dipole moment is affected by the substrate magnetization. As a result, magnetization determines how much the adsorbates accept, or donate, charge density with the substrate and change the work function. Note that a spin-polarized detection scheme, such as Mott polarimetry, can also be used in tandem with UPS; work by Viswanatha et al. showed that the spin and momentum, both transverse and longitudinal, of the photoelectrons can be resolved for 3-methylcyclohexanone adsorbates on Cu(643) surfaces.27

2.2. Electron Transport

Since the first report in 2006,9 many studies have explored spin-polarized electron currents through tunnel junctions of various types. Notably, studies also show that electron transport through chiral semiconductors and chiral metals is spin-filtered. Thus, CISS does not originate from a particular subclass of conventional conductance mechanisms; however, it remains unclear if the mechanism underlying the spin selectivity is different for metallic conduction than it is for tunneling. To date, no correlation between reported spin polarizations and corresponding conductivities among different classes of materials has been reported.42

2.2.1. Conductive Probe Atomic Force Microscopy

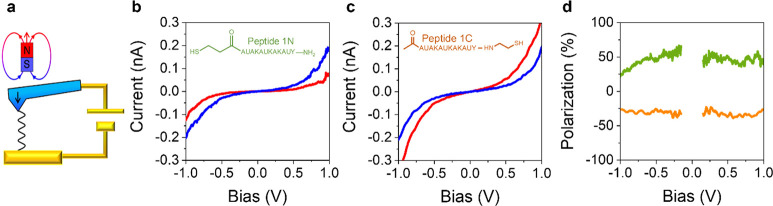

Magnetic conductive probe-atomic force microscopy (mc-AFM) studies, in which a ferromagnetic electrode acts as a spin analyzer, are now available for a large range of organic and bio-organic molecules, hybrid organic–inorganic materials, and inorganic materials (see Section 3). mc-AFM measurements display distinctive characteristics (vide infra) and are being widely used. It is important to note, however, that the geometry in which the experiment is performed can determine the sign of the polarization; see ref (43) for a recent discussion on this topic. Figure 3 exemplifies these features for the case in which the AFM tip is magnetized, either North or South, relative to the molecule. The current voltage curve for the peptide 1N (Figure 3b) shows that the current is higher when the tip is magnetized to select for electrons with their spins oriented parallel to their velocity (blue) as compared to the case in which the electron spins are oriented antiparallel (red) to their velocity. That is, the magnitude of the current is higher when the electron spin direction and the electron velocity are aligned parallel. It is common to define a percent polarization as

| 2 |

and this is plotted in Figure 3d for the peptide 1N (green). The same measurement on peptide 1C (linker attached to the C-terminus of the peptide rather than to the N-terminus) displays an opposite behavior. That is, the current is higher for the case where the spin is aligned antiparallel to the electron velocity (see Figure 3c). An analogous dependence on the peptide’s attachment to the surface was reported from photoemission studies.8,44

Figure 3.

Panel a shows the experimental geometry used for a measurement of the current–voltage curves. Panel b shows current–voltage curves for peptide 1N with the linker on the N-terminus of the peptide. The blue curve corresponds to a South magnetized tip in which the electron transport is aligned parallel with its spin and the red curve corresponds to a North magnetized tip in which the electron transport is aligned antiparallel to its spin. Panel c shows current voltage curves for peptide 1C; in this case the South magnetized tip shows a lower current and the North magnetized tip shows the higher current. Panel d plots the percent spin polarization, as calculated from the data in panels b and c for peptide 1N (green, 44%) and peptide 1C (orange, −32%). The figure is adapted from ref (43) with permission. Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons.

The experimental mc-AFM studies have caused intensive discussion because they display behavior that differs from those commonly expected for magnetoresistance devices used in spintronics.45 Those devices are based on two ferromagnetic electrodes comprising a “hard” magnet (high coercivity) and a “soft” magnet, with an insulating metal oxide layer, typically tens of nanometers thick, between them. In common magnetoresistance devices, the current behaves as if it flows through a diode, namely one spin current is dominant under positive voltage bias and the other under negative bias. This is not the case for CISS-based devices where the same spin-current is dominant, independent of the voltage sign. In addition, CISS-based devices often display spin polarizations that are higher than what is expected for the magnetic layer acting as the analyzer polarizer, which implies that the chiral molecular junction must be nonlinear. In fact, the current in CISS-based junctions often depend nonlinearly on the voltage, see Section 3.1.1 and the discussion below.

The current–voltage data in the mc-AFM measurements can be understood by considering a model in which the applied voltage polarizes the chiral system and this charge polarization is accompanied by spin polarization (see ref (46)). The model considers a chiral molecular film located between two leads, one of them a ferromagnet, and assumes that charge polarization of the chiral molecules by the applied voltage causes spin polarization. The positive pole of the chiral molecules is associated with one spin and the negative pole is associated with the opposite spin in an enantiospecific manner, i.e., depends on the handedness. Hence, electrons that have to penetrate into the chiral system from the ferromagnetic electrode confront a spin-dependent barrier whose magnitude is proportional to the charge at the pole times the spin-exchange interaction. By assuming that the charge at the pole is about 10% of an electron charge and that the magnitude of the spin-exchange interaction is on the order of 1 eV, one finds the difference in barrier height for the two spins to be ∼100 meV. Indeed, experiments indicate that the difference in injection barrier for the two spins is of this order of magnitude, e.g., see ref (10). Such a barrier explains the very high spin selectivity at room temperature. Other works have proposed “spinterface” models to explain these experimental signatures in a more quantitative manner (see Section 5.1).

2.2.2. Scanning Tunneling Microscopy Methods

Diez-Perez and co-workers11 used scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) break-junction measurements to show that CISS manifests in single molecule junctions, i.e., the spin-filtering does not depend on having a chiral film, but can manifest at the single molecule level. In this work, they trapped individual peptide molecules between a magnetized STM Ni tip and an Au electrode and measured the current. They found that the molecular conductance depends on the magnetization state of the STM tip and on the enantiomeric form of the peptide. Note that these measurements did not display a perfect antisymmetry, and it was necessary to invoke a spin-to-charge voltage (or “spinterface” effect, see Section 5.1) to fully explain the data. More recently, CISS studies at the single molecule level have been performed by Bürgler and co-workers, who used spin-polarized STM to examine the enantioselective adsorption of chiral molecules on magnetic surfaces,47,48 and by Ortuño et al., who have developed a chiral oligo(phenylene)ethynylene based molecular tunnel junction and used theoretical calculations to predict spin polarizations of 20% to 40%.49 Collectively, these experiments demonstrate that CISS manifests at the single molecule level.

2.2.3. Magnetoresistance and Spin Valve Studies

The mc-AFM method described in Section 2.2.1 can be viewed as a spin valve, in which the magnetic probe tip, or the substrate, acts as the ferromagnetic contact. A vertical magnetic spin valve device comprises a chiral film that is contacted on one side to a normal metal electrode and on the other side to a magnetic electrode, whose magnetization direction can be changed by an applied external magnetic field. In this device, a magnetoresistance is obtained from measurements of the current–voltage response through the top and bottom contacts as a function of an applied magnetic field and probe how the chiral film affects the magnetoresistance. This configuration was first used to measure spin-selective charge transfer through a self-assembled monolayer of polyalanine with a magnetized Ni layer,50 and has since been used to evaluate the magnitude of the CISS effect with other chiral systems.51 Unlike standard spintronic devices, in this configuration only one magnetic layer is needed for a CISS-based device because the chiral axis direction of the insulating layer determines the spin direction that is analyzed. In a four-probe setup it is possible to measure the magnetoresistance without the contribution of the contact resistances. In this configuration, larger area devices are used and smaller magnetoresistance values are found; see ref (52) for further explanation and Figure 9 for a representative example. Note that more elaborate spin-valve structures have also been used for studying CISS.53,54

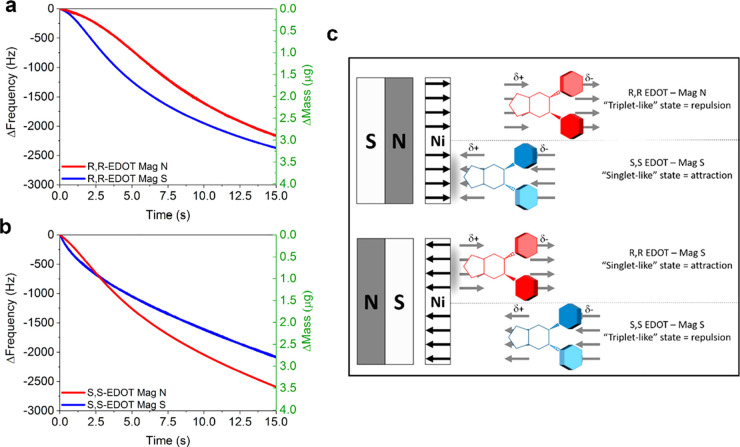

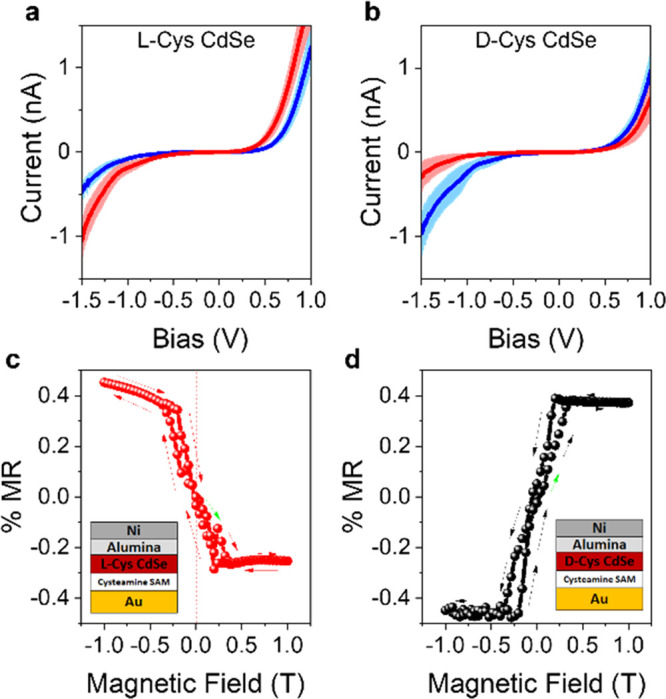

Figure 9.

Spin transport measurements on CdSe quantum dots passivated with l-cysteine (a,c) and d-cysteine (b,d) ligands. Panels a and b show mc-AFM measurements in which the red curve corresponds to the electron spin antiparallel to its momentum and the blue curve corresponds to the electron spin parallel to its momentum. The shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals. Panels c and d show corresponding magnetoresistance (MR) measurements on spin-valve devices. The data are replotted from ref (163) with permission. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

2.2.4. Electrochemical Tunnel Junctions

The determination of CISS in a tunnel junction configuration was first shown using electrochemical methods on porphyrin terminated chiral molecular scaffolds, l-Cys-(pro4(2S4S))4-Porph and d-Cys-(pro4(2R4R))4-Porph, immobilized on gold electrodes.9 Here, excitation of the porphyrin with circularly polarized light (left vs right) created a spin-polarized population of porphyrin excited states and the subsequent photocurrent was measured. Interestingly, a spin polarization (ca. 0.5%) in the photocurrent was observed with excitation polarization and was found to depend on the handedness of the molecular scaffold. The results were rationalized as spin-dependent processes affecting the electronic coupling. Similar results have been shown for chiral oligopeptide SAMs with tethered CdSe quantum dots on ferromagnetic electrodes placed in contact with a ferri-/ferrocyanide redox couple; however, here the polarizations were determined by changing an applied magnetic field on the electrode.55 Upon excitation, polarizations as high as 30% were reported at the redox potentials of the ferri-/ferrocyanide and the findings were corroborated by steady-state fluorescence measurements that monitored the asymmetry in quenching associated with electron transport to the electrode. Electrochemical methods have also been used to measure spin polarization in the dark; Kettner et al. observed changes in the oxidation and reduction currents for ferri-/ferrocyanide solutions, using magnetized electrodes coated with oligopeptide SAMs.15 The larger current response was found when the spins were aligned antiparallel to their momentum, in agreement with the conclusions drawn from photoemission measurements for the same oligopeptide assemblies.

Researchers have quantified changes in the charge transfer rate, k0, of redox species attached to chiral monolayers. For instance, ferrocene-oligopeptide composites immobilized on gold showed an asymmetry in the charge transfer rate for reduction and oxidation that depends on the handedness of the oligopeptide, e.g., for l-oligopeptides the k0 for reduction was faster than the k0 for oxidation and for d-oligopeptides the k0 for reduction was slower than the k0 for oxidation.56 This behavior was attributed to an induced magnetization associated with the oligopeptide assembly, similar to that shown in other works,57 and the CISS-mediated transport properties of the oligopeptides. Experiments have also been performed on magnetized ferromagnetic electrodes, so as to exclude spontaneous magnetization effects.58 In these studies cytochrome c was immobilized on Cys-Ala-Glu tripeptide monolayers and electron transfer from the cytochrome c’s heme unit to the electrode was measured. For tripeptide SAMs in which each of the substituents was levorotatory (LLL), a North applied magnetic field led to a faster rate constant than a South magnetic field, whereas tripeptide SAMs comprising all dextrorotatory substituents (DDD) resulted in the opposite dependence, i.e., a South magnetic field led to a faster rate constant than North magnetic field. For SAMs with a heterochiral structure, e.g., LDL, the electron transfer rates for North and South applied magnetic fields were the same.

The spin-specific change in charge transport through chiral molecules in electrochemical tunnel junctions, be that through monitoring changes in current or charge transfer rate, likely arise from the same phenomenon: spin-dependent changes in resistance for charge transport. This supposition is supported by recent impedance measurements made on DNA coated ferromagnetic electrodes, in which an equivalent circuit model analysis is used to extract the charge transfer resistance as a function of applied magnetic field.59−61 For the DNA assemblies, deviations in charge transfer resistance with magnetization orientation are observed, owing to the CISS effect; however, in achiral systems the charge transfer resistance is unaffected by the magnetic field orientation.

2.2.5. Hanle Rotation

The Hanle effect can probe the spin polarization of carriers in a semiconductor by measuring their spin precession and dephasing as they propagate through a transverse magnetic field.62,63 In addition to determining spin lifetimes, Hanle effect measurements also report on pure spin transport and on spin accumulation, which gradually reduces to zero with increasing magnetic field strength.64,65 In traditional electrical Hanle measurements a ferromagnet is used to generate a spin-polarized current in a transport channel that is probed through spin accumulation on a semiconductor. Recently, Xiong and co-workers generated spin-polarized current by injecting electrons from an Au electrode, which was coated with an α-helical polyalanine film, into a transport channel and detected the spin accumulation at a GaAs electrode (Au/l-polyaniline/Si:GaAs junctions).66 They observed universal temperature and bias current dependences for the spin-polarized carriers. These results provide further evidence that CISS-based spin polarization can be detected without the use of a ferromagnet.

2.3. Charge Polarization and Spin Polarization Methods

The methods in Section 2.2 rely on steady-state or periodic charge currents; however, this need not hold for observing spin polarization in chiral molecules. Recent studies show that it is enough to charge polarize chiral materials transiently to generate a spin polarization, and that the complementary response in which a magnetization induces a charge polarization can manifest.

2.3.1. Spin-Dependent Polarization in Hall Voltage

Surface magnetizations, induced by the CISS response of a chiral film, have been investigated using the Hall and anomalous Hall effects.20,67 Hall effect devices68 are widely used for continuous monitoring of spin-induced magnetization,69 and they commonly have one of two configurations: a standard Hall bar configuration and a van der Pauw square configuration.70 It is important to note that in shallow two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) devices the surface spins interact strongly with the 2DEG through Ruderman–Kittel–Kasuya–Yosida (RKKY) interactions.71 When spin-polarized electrons are injected into III–V heterostructures (such as AlGaN/GaN or AlGaAs/GaAs) that contain a 2DEG layer, the semiconductor becomes magnetized, even at room temperature, with a magnetization direction that depends on the direction of the polarization of the injected spins.72 For dry measurements, a shallow GaAs 2DEG is mostly utilized,67 while for liquid solutions GaN-based 2DEG are most used.72 The latter can also be used to monitor the spin dependence of electrochemical processes.

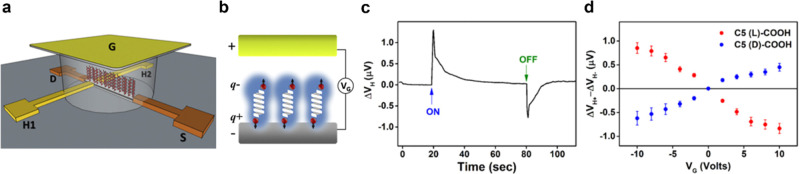

In 2017, Kumar et al. used a Hall bar device to show that an applied voltage acting on a chiral oligopeptide film generates a magnetization at the interface between the monolayer film and the Hall bar surface, even though no net current flows.20Figure 4a,b shows a schematic diagram of their experimental measurement design. They constructed a Hall bar circuit, which was buried under a few nm thick film of GaN and then coated with a self-assembled monolayer film. The application of a voltage between the bottom working electrode and the counter-electrode (G) creates a displacement current that charge polarizes the chiral molecular film and generates a transient Hall voltage signal (Figure 4c), which then decays. Upon release of the applied voltage, the film discharges and generates an opposite Hall voltage because of the opposite direction of current flow. Figure 4d shows that the signal increases with the magnitude of the applied voltage, which increases the charging current, and that it is enantiospecific, i.e., a film of l-oligopeptide has a response opposite in sign to that of a film of d-oligopeptide. Note that no magnetic materials and no external magnetic fields are present in this experiment; the chiral charge polarization of the molecules gives rise to a spin polarization at the bottom of the film that manifests as a magnetization that acts on the charge carriers moving in the source drain channel.

Figure 4.

Panels a and b show a representative schematic diagram of a Hall device passivated with chiral oligopeptides. Panel c shows that upon charge polarization of the oligopeptides, a transient Hall voltage is generated. Panel d shows the dependence of the Hall voltage on the magnitude and sign of the gate voltage and the handedness of the oligopeptides. The figure is adapted from ref (20) with permission.

The Hall circuit design can be incorporated into a working electrode, which can be used to probe spin-selective charge transfer and charge displacement processes. The electrochemical cell used in the above experiment was constructed to not display any Faradaic current, so that the oligopeptide-coated electrode surface would closely approximate an ideally polarizable electrode. If instead, one constructs an electrochemical cell with a redox couple, then Faradaic current can flow and the working electrode, with its embedded Hall device, allows one to monitor the spin dependence of redox reactions in addition to the charge currents that are traditionally measured.72 By using a working electrode that possesses an embedded Hall probe, one can perform “3D spin electrochemistry”,73 i.e., measure the current, voltage, and spin simultaneously for redox reactions.74

Most of the Hall signal induced by chiral molecule adsorption on metals and semiconductors seems to arise from the anomalous Hall effect.75 This was verified by experimentally verifying the relation between the longitudinal and Hall resistance as a function of temperature.76

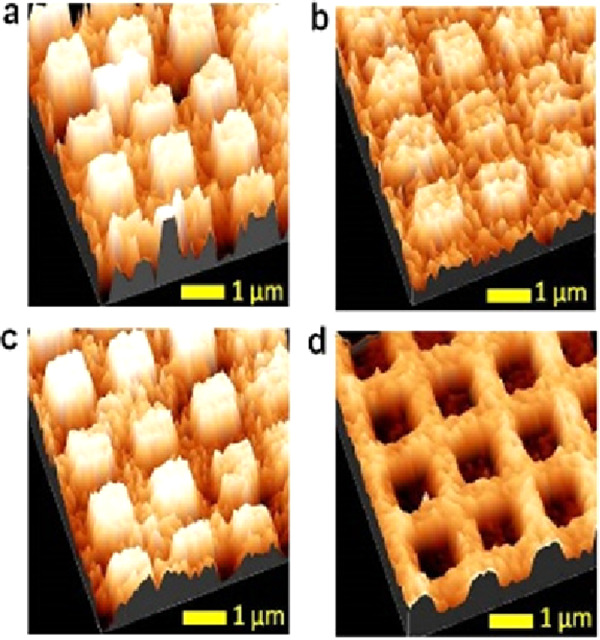

2.3.2. Emergent Magnetic Properties and Magnetic Force Microscopy

The spin polarization, which is generated by the charge redistribution in chiral molecules, can be stabilized in a ferromagnetic film. Figure 5 shows magnetic force microscopy images of lithographed surfaces in which chiral molecules, by virtue of their charge-polarization induced spin-polarization, imprint a magnetization onto a ferromagnet.57Figure 5a,b shows topographical images of a patterned surface on which l- and d-polyalanine monolayers are adsorbed, and the corresponding magnetic force microscopy images in Figure 5c,d show opposite magnetization directions. These findings establish that as chiral molecules and ferromagnetic layers come into contact, the spin-polarized current exchange between the chiral layer and the ferromagnet is very efficient in polarizing the spins of the ferromagnet (Figure 5).50 In this case, about 1013 electrons per cm2 are sufficient to induce magnetization reversal. The direction of the magnetization depends on the handedness of the adsorbed chiral molecules, i.e., it is enantiospecific. In contrast, the current density required for the spin-transfer torque in modern magnetoresistive random access memory is 106A cm2, or about 1025 electrons cm2/s, a trillion times higher. Note that the inverse effect, enantiospecific interaction of chiral molecules with a magnetized substrate, can be used to separate chiral molecules21 (see Section 6.2).

Figure 5.

Topography and magnetic force microscopy phase images are shown for a molecular-induced magnetization orientation. The top row shows AFM topography images of SAMs of l-polylalanine (a) and d-polyalanine (b) adsorbed on Co thin ferromagnetic layers with a 5 nm Au overlayer, and the bottom row shows their corresponding magnetic AFM magnetic phase images (l-polylalanine (c) and d-polylalanine (d)). Adsorption of oligopeptides induce a magnetization, and the direction of the magnetization is controlled by the enantiomeric form of the molecules. The figure is adapted from ref (57) with permission (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

2.3.3. Spin Exchange Microscopy

The enantiospecific interaction between chiral molecules and ferromagnetic surfaces enables one to perform locally resolved magnetic imaging by adsorbing chiral molecules on an AFM tip.78 This technique is based on short-range spin-exchange interactions that can be scaled down to atomic resolution and only require a conventional AFM tip functionalized with a chiral molecule. A direct measurement of the force and tip displacement for the interaction between a ferromagnetic substrate and chiral molecules provides energy for the interaction, and the difference in energy for the two magnetization directions (North versus South) of the ferromagnet allows one to determine the difference in exchange energies. The mean pulling energy showed a difference of 150 meV for sample magnetizations of North and South along the sample normal.

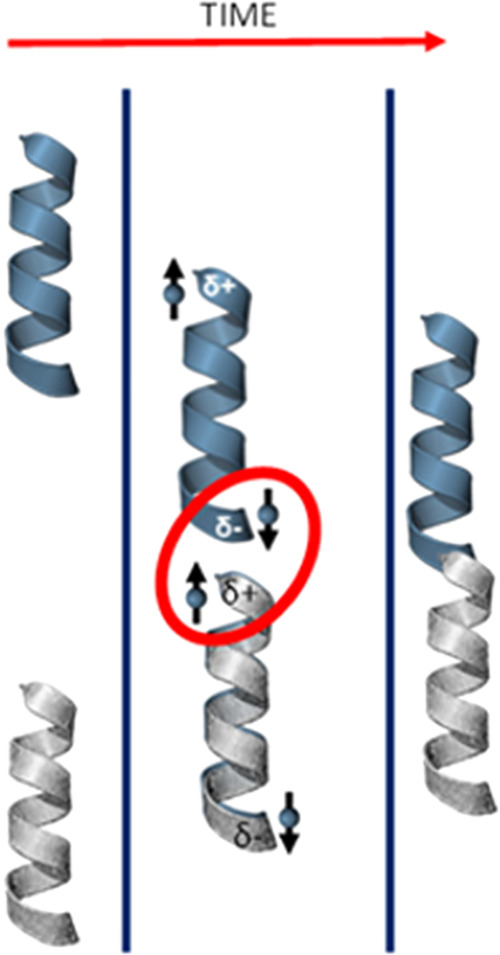

To illustrate the phenomenon, consider the interaction between two helical molecules. When two chiral molecules of the same handedness interact, the charge polarization is accompanied by a spin polarization acting in the same direction, e.g., pointing outward along the helix axis (see Figure 6), and the exchange interaction between the molecules’ excess spin densities in the overlap region is characterized by two spin polarizations aligned antiparallel. In contrast, the spin polarizations of two interacting molecules of opposite chirality would be aligned parallel. The difference in these spin arrangements generates a change in exchange energies.20 Note that the spin polarization manifests even when the two molecules are each closed shell; while they remain singlet states globally, their electron clouds can locally display spin imbalances.

Figure 6.

The image shows the effect of spin-dependent charge reorganization interactions between two chiral molecules. From left to right: The two chiral reactant molecules are represented by helices and are noninteracting at a very large distance. As the chiral molecules approach each other dispersion forces generate induced dipoles on each molecule, which in turn are accompanied by a spin polarization. The two chiral molecules react to give a product with an energy that depends on whether the spin polarizations on the molecules are aligned antiparallel or parallel.

2.3.4. Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy

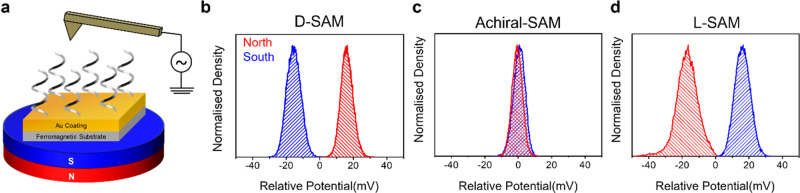

Probing the surface potential that is induced by spin transfer can be achieved using Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM). The basic Kelvin probe measurement consists of a metallic probe electrode that is placed near the sample surface to form a capacitor.79 Then, the distance between the probe electrode and the sample surface is changed periodically to generate a frequency dependent capacitance. Thus, an AC voltage is created across the gap, and it is proportional to the voltage difference between the probe electrode and the sample. Rather than record the AC voltage directly, it is common to apply a DC voltage, referred to as the contact potential difference (CPD), to null the response. To measure the CISS-induced spin wave function changes, the CPD can be measured when altering the adsorbate’s enantiomeric form and the surface magnetization (see Figure 7). Kelvin probe measurements on ferromagnetic thin film electrodes coated with self-assembled monolayers of chiral molecules reveal that the electron penetration from the metal electrode into the chiral molecules depends on the ferromagnet’s magnetization direction and the molecules’ chirality. Figure 7b–d shows the changes in the measured CPD with North (red) and South (blue) magnetizations for d-oligopeptide SAMs, achiral SAMs, and l-oligopeptide SAMs, respectively.19 Electrostatic potential differences as large as 100 mV are observed and arise from the applied oscillating electric field, which drives spin-dependent charge penetration from the ferromagnetic substrate to the chiral molecules. The large potential changes (>kT at room temperature) imply that this phenomenon is important for spin transport in chiral spintronic devices and for magneto-electrochemistry of chiral molecules.

Figure 7.

Panel a shows a schematic diagram for the Kelvin probe measurement. Panels b–d show changes in the measured contact potential difference with North (red) and South (blue) magnetizations for d-oligopeptide SAMs, achiral SAMs, and l-oligopeptide SAMs, respectively on ferromagnetic electrodes. The figure is adapted from ref (19) with permission. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

2.4. Other Techniques

While studies of the CISS effect in chiral materials are most prevalent using the techniques discussed above, a number of other strategies have been demonstrated and are being developed. Here, the manifestation of a CISS-response is akin to that described previously, in that it arises from a spin-dependent response in the material that depends on the chirality.

2.4.1. Fluorescence

Fluorescence spectroscopy can provide detailed information about relaxation and/or charge and energy transfer processes that take place following light absorption. Thus, if energy transduction is affected by spin selectivity in a chiral system, then the photoluminescence of a chromophore can report on the spin-dependence for the transduction. For instance, researchers showed that the photoluminescence of nanoparticles tethered to magnetized ferromagnetic substrates through chiral oligopeptides changes with the orientation of an external magnetic field.55 Here, hole transfer, and hence photoluminescence quenching, from the nanoparticle to the substrate depended sensitively on the match, or mismatch, between the spin selectivity of the oligopeptide and the magnetization orientation of the substrate. Similar measurements have been made in which spin-dependent electron transfer80 and energy transfer81 processes are responsible for controlling the chromophore’s photoluminescence intensity with substrate magnetization.

In addition to steady-state fluorescence, time-resolved measurements can provide information about the importance of spin on charge transfer kinetics. Such behavior was demonstrated by studies of donor-bridge-acceptor nanoparticle systems, in which the acceptor was made chiral.82 Here, excitation of the donor nanoparticle with clockwise and counterclockwise circularly polarized light, thus yielding spin-polarized excitation of the donor, resulted in large differences in charge transfer rates to the acceptor because of the CISS effect. Note, however, that the efficacy of these measurements relied on several factors: (i) the system required a principal excitation axis to define the electron spin orientation relative to that of the transport trajectory, and (ii) the time scale for electron transfer had to be shorter than the decoherence of the spin.

2.4.2. Resonance Spectroscopies

To date, only a handful of spectroscopy methods have been applied to the study of CISS; however, they are likely to prove very important in future studies, because they can provide incisive information about CISS when the chiral system is weakly coupled to its surroundings.

2.4.2.1. Cross-Polarization NMR

Although “conventional wisdom” holds that nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is not sensitive to a molecule’s chirality unless it is perturbed by a chiral bias of some sort, this assumption is overly simplistic. For example, Buckingham has shown that NMR methods that sense odd parity magnetoelectric coupling terms should be able to directly probe chirality.83,84 In other works, Ugalde and co-workers used CP-NMR to measure the solid-state NMR spectra of 15N nuclei for different enantiomers of amino acids, and found a systematic and significant increase in the signal levels for the d-isomer over that for the l-isomer, even though the chemical shifts are identical.85,86 The CP-NMR experiment transfers polarization from the majority nuclear spins (protons in this case) to the dilute minority spins (15N nuclei in this case) and the efficiency of this process is enantiospecific, giving rise to higher signal intensities for the d-isomer in their spectrometer. This finding implies that the coupling, which leads to the polarization transfer, is enantiospecific and they propose a mechanism based on CISS to rationalize their findings. Experiments of this sort are important for studying fundamental features of CISS, because they do not have the complications associated with molecule–substrate couplings; rather, they probe the interaction between nuclei in the amino acid molecules, via the molecule’s CISS-based electronic response.

2.4.2.2. Time-Resolved EPR Studies

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), or electron spin resonance (ESR), spectroscopy can provide a direct probe of spin polarization. Its use in CISS studies was first reported in 2020 by Ansermet and co-workers to probe the spin polarization of paramagnetic radicals that are produced by electrochemical reduction at a chiral electrode (i.e., Au coated with an oligopeptide).87 Since that initial report, a number of other research groups have actively pursued experimental and theoretical studies into identifying CISS signatures in EPR spectra and proposed photochemical mechanisms to enhance them.26,88−90 Recently, Wasielewski and co-workers have demonstrated that photoinduced electron transfer in a donor-chiral bridge-acceptor molecule gives rise to electron spin polarization in the biradical product, ca. 50%.91

2.4.3. Magnetometry and Magneto-optical Methods

The accumulation of spin polarization at interfaces, or even self-contained in chiral materials, has led to the use of magnetic-based detection schemes for monitoring the CISS effect. Indeed, such behavior is responsible for the response in Hall devices (Section 2.3.1), magnetic force microscopy (Section 2.3.2), and spin-exchange microscopy (Section 2.3.3) measurements; however, other methods for detection have also been employed. For instance, superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometry has been used to measure the effect of chiral molecules on the magnetic properties of materials; studies show that superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles adsorbed on chiral self-assembled monolayers become ferromagnetic92 and conventional superconductors may exhibit topological superconductivity when interfaced with chiral molecules.93

Another technique, which has been used to probe the CISS-effect in chiral materials, is magnetic circular dichroism. Here, a magnetic field is oriented parallel or antiparallel to the direction of light and the differential adsorption of left and right circularly polarized light is measured.94 In a typical experiment, the orientation of the external magnetic field determines the sign of the optical activity. Conversely, when the CISS effect is stronger than the effect imposed by the external magnetic field, a change in magnetic field orientation does not change the sign of the optical activity. Such behavior has now been observed for chiral mesostructured BiOBr and α-Fe2O3.95,96

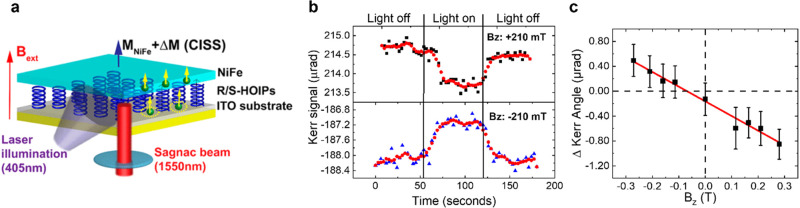

Spin transport from chiral materials to adjacent ferromagnetic layers has been probed by magneto-optic Kerr effect (MOKE) measurements in which a change in the magnetization of a magnetic material is monitored through changes in the reflection of polarized light off its surface. Figure 8a shows a schematic for MOKE measurements. Here, linearly polarized excitation of a chiral perovskite film creates a photoinduced spin current that magnetizes an adjacent ferromagnetic layer.97 The Kerr angle, reflecting the change in magnetization of the ferromagnetic layer, depends on the perovskite’s enantiomorph, whereas achiral perovskites show no response. Figure 8b shows the change in MOKE response upon photoexcitation of the perovskites, and Figure 8c plots the change in Kerr angle with applied magnetic field. Experiments have shown that a change in Kerr response can occur upon photoexcitation or thermal activation of chiral layers because of CISS-mediated transport.97,98

Figure 8.

Panel a shows an experimental schematic for magneto-optic Kerr effect measurements on chiral perovskite thin films. Panel b shows magneto-optic Kerr rotation measurements on S-hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites, under positive (top) and negative (bottom) out-of-plane external magnetic fields. The red line is an adjacent average smoothing of the data. Panel c shows the change in photoinduced Kerr response as a function of the external magnetic field strength. The red line is a linear fit to the data. The figure is adapted from ref (97) with permission. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Note that other spectroscopic methods, such as optically detected magnetic resonance via nitrogen vacancies in diamond, are also being used to measure magnetization effects for CISS studies, e.g., reorientation of ferromagnetic layers upon adsorption of chiral molecules.99

2.4.4. Spin Seebeck Effect

In magnetic materials, spin currents can arise from temperature gradients by the conventional spin Seebeck effect.100 Recently, Sun and co-workers used a temperature gradient to generate a spin selectivity effect in chiral materials without any ferromagnetic layer, which they call the CPASS (chiral-phonon-activated spin Seebeck) effect.98 In this case the chiral phonon–electron coupling generates a spin current because of the conservation of angular momentum, i.e., the chiral phonons transfer angular momentum to the electron spin angular momentum. CPASS provides a unique and incisive probe for examining the importance of electron–phonon coupling for the CISS effect. CPASS could also be used to distinguish between coherent and incoherent chiral pumping of spin waves in thin magnetic films.101

3. Materials and Molecules Exhibiting CISS

Early experiments on CISS have examined spin-dependent electron transport and electron polarization with organic molecules, for which the structure and organization of their assemblies can be manipulated. More recent studies have shown that CISS manifests for a wide array of molecular, supramolecular, and materials types. CISS effects have been reported for insulating, semiconducting, and metallic chiral solids; chiral quantum dots, chiral 2D layered materials, and chiral polymers, including biopolymers, and their assemblies. Here we overview these studies and identify key aspects about CISS, which they have revealed. Note that, a comparison across material types is discussed in Section 4.

3.1. Molecules and Macromolecules

3.1.1. DNA and Oligopeptides

DNA (see refs (7, 10, 12, 31, 52, 59−61, 80, 102−111)) and α-helical oligopeptides (see refs (11, 15, 19−21, 30, 43, 44, 50, 52, 54−57, 67, 69, 72, 74, 77, 92, 99, 104, 112−126)) have been widely used to explore the CISS effect and its connection with molecular properties. Having been investigated by spin-dependent photoemission, transport, electrochemical, and spin-dependent polarization experiments, they comprise testbed systems for comparisons between methods. These studies have provided a number of key insights into CISS properties.

Polarization, P, as a Metric

For both families of molecules

spin polarization exceeding 60% was found, when the polarization, P, is defined as  with j+ and j– referring to the charge current measured

when the magnetic North pole is pointing toward the adsorbed molecules

or away from them, respectively; and these magnitudes compare well

to those observed by spin-polarized photoemission studies.15

with j+ and j– referring to the charge current measured

when the magnetic North pole is pointing toward the adsorbed molecules

or away from them, respectively; and these magnitudes compare well

to those observed by spin-polarized photoemission studies.15

Length Dependence

Over the size ranges studied (<20 nm for DNA and shorter for oligopeptides), the P increases linearly with the length. It is found that the α-helices of oligopeptides are about a factor of 5× better spin filters than DNA, on a per nanometer basis.104 The length dependence of the spin polarization results from the conduction of the favored spin decaying more slowly as a function of length than does the unfavored spin.

Voltage Dependence

In the conduction studies performed with the mc-AFM method, it was established that spin-dependent conduction displays a power law dependence on the voltage, with the power d being greater than one, and that a different voltage threshold for conduction exists for each of the spin polarizations. The different thresholds imply that spin flipping during the conduction is not significant, i.e., a mixed spin distribution would not generate different voltage thresholds.104,127

Point Chirality versus Helical Chirality

Helical chirality appears to give rise to stronger spin filtering than the point chirality of individual stereocenters. Electrochemistry-based measurements show that folding DNA duplexes, comprising the same nucleobase sequences, into right-handed or left-handed helices controls the sign of the spin-filtering, implying that the helical twist of the duplex DNA dominates over the point chirality of the sugars.102 This observation is consistent with Mott polarimetry photoelectron studies using disordered films of single-stranded DNA and oligopeptides that display poor spin-filtering.12

Dipole Orientation Effect

Both photoemission8,44 and mc-AFM measurements43 show that the sign of the spin-polarized current changes with the orientation of the molecule on the electrode. That is, placing an oligopeptide on a metal substrate by its carbon end gives a different sign for the spin polarization than binding it to the electrode by its nitrogen end.

Circular-Dichroism (CD) is a Predictor

Studies on oligopeptides of the same length but different CD strengths (lowest energy) show that the spin filtering increases as the CD strength increases.43 This claim is corroborated by studies on chiral quantum dots82 (see Section 3.2.2) and supramolecular structures128,129 (see Section 3.2.1).

3.1.2. Helicenes

Although helicenes do not contain carbon stereocenters, they possess axial chirality. CISS manifests in enantiospecific adsorption of helicenes to magnetized surfaces, in spin-filtered electron transmission via photoelectron spectroscopy, and in conduction experiments through monolayer films of helicenes.28,47,48,130−134 Although several classes of helicenes have been investigated, no reports have drawn a clear correlation between the structure of a helicene and its spin-filtering power. Photoemission studies indicate some effect of the substrate on the spin polarization; however, no simple correlation was found between the spin–orbit coupling of the substrate and the size of the spin polarization in the CISS effect.28 As a caveat, one must appreciate that different binding groups are used for attaching molecules to the different substrates and this can lead to different charge distributions at the interface, hence work functions. Thus, the exact role of the substrate remains an open issue and may require careful studies to reach firm conclusions.

3.1.3. Proteins

Experiments find that both redox proteins, as well as other proteins, display spin-polarized electron transport; including photosystem I, cytochromes, azurin, and multiheme electron transfer conduits, among others.22,58,115,135−142 These observations are consistent with electron transfer via peptidic pathways in proteins. Beyond these pioneering demonstrations, systematic studies have examined the temperature dependence of spin filtering, the importance of homochirality in electron transfer, and the role of CISS in allostery.

Temperature Dependence

Temperature-dependent conductance measurements show that the spin-filtering decreases with decreasing temperature, even in cases where the overall conductance remains approximately constant. These studies imply that spin-dependent transport is activated, suggesting the importance of phonons for CISS to manifest.142 See Section 4.7 for more discussion of temperature-dependence studies.

Homochirality in Redox Chemistry

Because the linear momentum of the electron and its spin are locked, backscattering in homochiral assemblies is suppressed, which makes electron transfer more efficient. Measurements with the redox protein cytochrome c on oligopeptide films of differing enantiomeric forms show that the electron transfer rates in the heterochiral assemblies are suppressed, as compared to the electron transfer rates in homochiral assemblies.58

CISS in Molecular Recognition

Spin dependent charge polarization in proteins affects allostery, enhancing or reducing reactivity at sites far from the binding position of the substrate. A recent study on the association of an antibody with its target protein antigen can be modulated by a ferromagnet, even when the protein is bound to the ferromagnetic substrate at a site remote from the binding site.22,143 The charge reorganization is modulated by the magnetization because the charge displacement currents in the protein are spin polarized.

3.1.4. Polymers

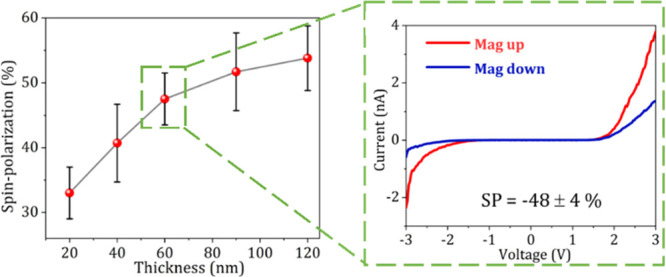

Spin-filtered electron transport and spin polarization manifests in chiral polymers and chiral polymer fibers.129,144−149 In a number of cases these films are grown by CISS-mediated processes (see Section 6.3.3). A major outcome of these studies is the demonstration that spin-filtered electron transport can proceed over hundreds of nanometers to microns in length. For example, Yan and co-workers showed that polyaniline fibers spin-filter electron currents over length scales of a few microns, along the chiral axis of the supercoiled fibers.144 The spin filtering is not restricted to transport along the polymer chains, even current through thick (up to 120 nm) films of chiral polymers display spin-filtered currents, see Figure 11. Similar to the case of biopolymers, the spin-filtering is temperature activated150 and a correlation exists between the spin polarization and the strength of the CD signal.147

Figure 11.

The plot shows the dependence of the spin polarization on the thickness for the polymer synthesized on a ferromagnetic electrode with application of an oriented external magnetic field. The inset shows the average current versus voltage (j–V) curves recorded for 60 ± 3 nm thickness polymers with the magnet North pole pointing up (red) and down (blue). The figure is adapted from ref (150) with permission. Copyright 2022 American Association for the Advancement of Science.

3.2. Inorganic and Hybrid Organic–Inorganic Materials

Reviews of chiral inorganic materials have recently become available.151−154 Here we focus on CISS studies associated with different classes of chiral inorganic and hybrid inorganic–organic materials. Given the promise of CISS for interesting applications in spintronics, optoelectronics, and catalysis, the number of CISS studies with inorganic materials is expanding.

3.2.1. Chiral Supramolecular Constructs

Inorganic materials and organometallic supramolecular assemblies exhibit CISS properties and can be combined with other functional elements of supramolecular constructs for bespoke spin-selective functions. For example, Therian and co-workers used mc-AFM and spin-Hall measurements to show that chiral conjugated zinc-porphyrin molecular wires polarize spin currents up to 32%.155 Incubating the as-assembled chiral molecular wires in binucleating ligands of the opposite handedness causes a flip in the circular dichroism response and corresponding spin-filtering properties of the assembly. In other work, Cardona-Serra and co-workers used cyclic voltammetry, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, and transport studies to show that incorporation of paramagnetic Tb3+ lanthanides into helical peptides leads to higher spin polarizations compared to metallizing with diamagnetic Yb3+.122 The spin-filtering properties of the paramagnetic helical metallopeptides were later used to construct a memristor.156 In other studies, Sang et al. showed that helical nanofibers composed of achiral benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide molecules with an aminopyridine group that could coordinate to Ag(I) display spin polarizations of ∼45%,157 and Mtangi et al. showed that chiral Zn-porphyrin stacks display polarizations of ∼35%.158 Even much simpler organometallic complexes, which possess stereocenters as opposed to chiral secondary structures, exhibit CISS properties (see Wang et al.159 and Miwa et al.)160,161

Synergy of CISS and Spin Blockade

Spin filtering in chiral molecules containing paramagnetic ions is enhanced over that in molecules without paramagnetic ions, suggesting that CISS can be combined with more traditional spin blockade ideas to enhance spin filtering.122

Chiral Supramolecular Constructs

Yamamoto and co-workers showed that the assembly of achiral cobalt phthalocyanines into helical supramolecular assemblies on ferromagnetic substrates can be controlled by the magnetization state of the surface.162 This guided self-assembly is similar to the enantioseparation of amino acids from racemic solutions by crystallization onto magnetized surfaces.

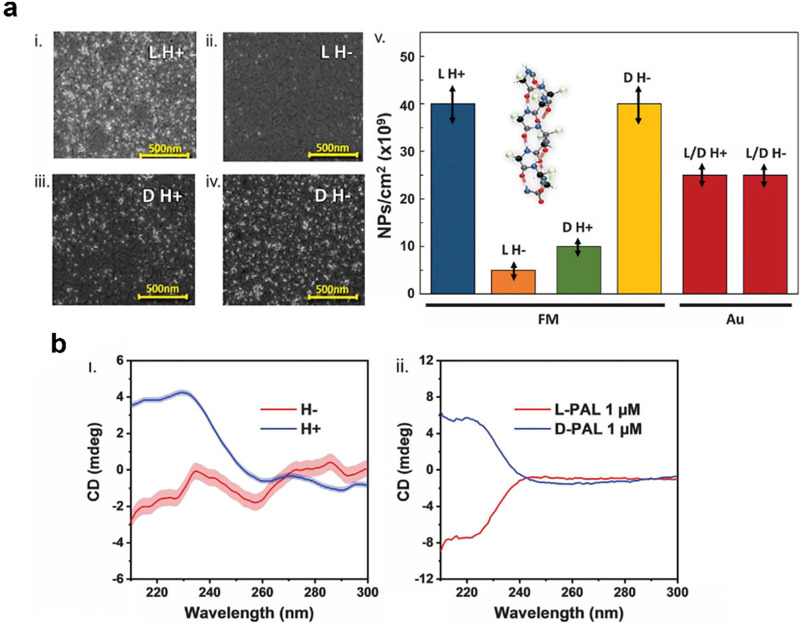

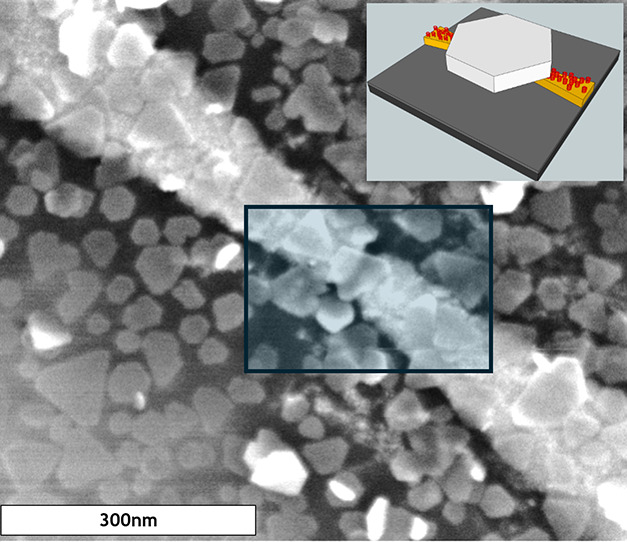

3.2.2. Chiral Inorganic Nanoparticles

The first report on a semiconductor’s CISS response was in 2016, in which chirality was imprinted on CdSe NPs by surface ligands.163Figure 9a,b shows mc-AFM measurements for studies on 2.2 nm CdSe nanoparticles passivated with cysteine molecules where an ∼33% polarization at negative bias and ∼15% polarization under positive bias was observed, in spite of the nanoparticles showing only a modest chiroptical response (∼0.5 mDeg).163 Moreover, a spin-valve device was constructed using the chiral nanoparticles and the data showed an asymmetric magneto-response in a manner consistent with the favorable spin alignment found for mc-AFM

In other works, assemblies comprising CdSe-polyalanine multilayers, using a layer-by-layer approach,164,165 display a large excitation polarization dependent change in fluorescence lifetime (∼3.5× longer for CW excitation than CCW) that was attributed to symmetry breaking-induced changes in nanoparticle coupling and spin delocalization.164 The enhanced delocalization between nanoparticles separated by long helical polyalanine was superior to that found in other experiments using short-chain achiral molecules,166 and thus, could prove useful for design strategies in parallel computing applications.

Chiral quantum dots have also found a number of applications examining fundamental CISS issues and exploring device concepts.

Electron Transfer Rates and CD Correlation

Electron donor-bridge-acceptor dyads, comprising an achiral CdTe NP donor and a chiral CdSe NP acceptor, were used to demonstrate how spin-filtering in chiral assemblies affects electron transfer rates.82 The electron transfer rate asymmetry, (ket,CW – ket,CCW)/(ket,CW + ket,CCW), was found to correlate with the strength of the circular dichroism spectrum for the acceptor NPs first exciton transition, and the maximum asymmetry was 88%. These studies showed that the rates can be described by a Marcus electron transfer picture in which the electronic coupling is affected by CISS.

Optospintronic Memory Architectures

Spin selective electron transfer between chiral NP constructs and a substrate have been used to write local magnetizations corresponding to logical memory.118 The spin selectivity of electron transfer with chiral CdSe NPs has been exploited to demonstrate a 9-state volatile-like spin-memory device.167

3.2.3. Hybrid Organic Inorganic Perovskites and Metal Halides

The initial work explicitly demonstrating CISS in R-/S-methylbenzylammonium (R-/S-MBA) lead iodide perovskite 2-D layered thin films was shown by Vardeny and co-workers and displayed spin polarizations as high as 92%.168 Similar findings have since been reported in hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites and metal halides with other compositions as well (see Table 1). In related work, researchers have incorporated achiral additives into the chiral matrix in order to improve the film crystallinity, yet retain their spin-filtering power.169,170 For instance, Lee et al. showed that the addition of urea to (R-/S-MBA)2PbI4 perovskites causes structural changes to the perovskite host, which can enhance the chiroptical response and ensuing spin polarization measured by mc-AFM.169 The spin-filtered currents in these materials can persist over thicknesses of hundreds of nanometers, and it is hypothesized to arise from multiple tunneling processes through the chiral organic molecules occupying the space between the layered octahedral perovskite sheets.168

Table 1. mc-AFM Determined Spin Polarizations of Different Hybrid Organic–Inorganic Perovskites and Metal Halides.

| Compositiona | Polarization (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| (R-/S-MBA)2PbI4 | 92 | (168) |

| (R-/S-MBA)2PbI4/CsPbBr3 | 80 | (171) |

| (R-/S-MBA)PbBr3 | 90 | (172) |

| (R-/S-MBA)2SnI4 | 94 | (173) |

| (R-/S-MBA)4Bi2Br10 | 84 | (174) |

| (R-/S-MBA)2CuBr4 | 92 | (175) |

| (R-/S-MBA)2CuCl4 | 92 | (175) |

| (R-/S-NEA)2CoCl4 | 90 | (170) |

R-/S-MBA is R-/S-methylbenzylammonium; R-/S-NEA is R-/S-1-(1-naphthyl)ethylamine.

The spin selectivity of perovskites in photoinduced transport has been leveraged for spin-polarized charge injection from perovskites into transition-metal dichalcogenides to manipulate valley pseudospins,176−178 to realize spin-mediated photogalvanic and photovoltaic devices,179 and to create circularly polarized light detectors169,174,180,181 (see Section 6).

The perovskite film studies reveal a number of important aspects for CISS-based materials as well.

Length Dependence and Mechanism

The studies on films show that spin-filtered electron currents can propagate over hundreds of nanometers,168 rather than the few nanometer limits observed for molecules. Measurements as a function of film thickness support a mechanism in which the chiral organic molecule layers spin-filter the electron currents and compensate for loss of spin purity as the propagation proceeds.

The Role of Chiral Phonons

Kim et al. showed that a spin-polarized current, which depended on the perovskite’s handedness and an externally applied magnetic field, manifests when a chiral perovskite is subjected to a thermal gradient.98 The spin polarization was attributed to a chiral-phonon-activated spin Seebeck (CPASS) effect.

3.2.4. Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDs)

A collection of works on chiral TMDs has recently been published and further expands the landscape of materials known to exhibit CISS properties. Duan and co-workers showed that intercalating chiral molecules into TaS2 and TiS2 TMD layers provide structurally robust materials with large spin polarizations, ca. 60%.182 Interestingly, spin tunnel junction devices made from the materials show magnetoresistance exceeding 300%, over an order of magnitude larger than that observed in previous CISS-based systems. Other methods for preparing chiral TiS2 have also been demonstrated.183 In related studies, Bian et al. report spin-polarized electron currents as high as 75% through 5 μm thick films of MoS2184 and greater than 90% in >100 μm TiS2 crystals.185

The spin polarizations generated in chiral molecules and materials may also prove fruitful when interfaced with TMDs to break valley state degeneracy. Research on single monolayer MoS2 and WSe2 interfaced with chiral perovskites showed changes in the degree of valley polarization and the effect was attributed to the spin-selective charge injection from the chiral perovskite, i.e., CISS.177 A similar enhancement in valley polarization was also observed when d-histidine was interfaced with a monolayer of MoS2.186 Here, the spin-dependent charge redistribution properties of the histidine, and strong hybridization between histidine and the MoS2, led to the degree of polarization at the +K valley being 7.73% and the −K valley being 1.6%. Note that spin-dependent charge redistributions in chiral molecules can lead to spontaneous magnetization,20 and application of external magnetic fields to TMDs can cause a Zeeman energy splitting that increases valley contrast.187,188

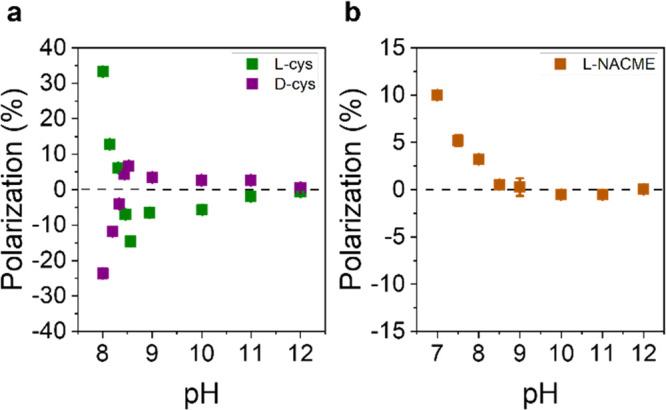

3.2.5. Metal Oxides

A wide array of chiral magnetic oxides are becoming available and offer promise for a range of applications.189 Interest in chiral metal oxides for CISS-applications stems from initial research showing that electrodes coated with chiral molecules reduces the reaction overpotential for the oxygen evolution reaction compared to analogous electrodes coated with achiral molecules (see Section 6.3.1).41 By adapting the electrodeposition methods developed by Switzer and co-workers,190,191 chiral CuO coated electrodes were studied by Mott polarimetry and shown to exhibit spin polarizations of ∼10%.39 In related experiments, the spin polarization through cobalt oxide surfaces was shown, using mc-AFM and Hall device measurements.192,193 More recently, Ghosh et al. showed that doping cobalt oxide thin films with 5% Mn afforded an ∼2-fold enhancement in the spin polarization (55–60%) compared to the undoped chiral thin film (25%),192 whereas Bai et al. showed that helical stacking of NiOx nanoflakes leads to 50–80% spin polarizations.194

Studies of transition-metal oxides manifest the interplay between chiral symmetry and magnetic ions, or materials. By comparing magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) spectra for helically stacked nanoflakes, Bai et al. showed that chiral α-Fe2O3, which is antiferromagnetic, exhibits a chirality-dependent/magnetic field-independent MCD response whereas the ferrimagnetic Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 nanoflakes exhibit a chirality-independent/magnetic field-dependent MCD response.95 They conclude that magnetic field effects in the ferrimagnetic metal oxides are stronger than the magnetic field generated by CISS, whereas the CISS effect dominates for antiferromagnetic materials. Other measurements on metal oxides indicate that chiral symmetry can influence the magnetic ordering of a material. For instance, asymmetric adsorption of chiral molecules on a 10 nm superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle caused the material to become ferromagnetic.92 In analogous experiments, vibrating sample magnetometer measurements showed that achiral CuO films were diamagnetic, whereas chiral CuO films were mostly paramagnetic with a weak ferromagnetic hysteresis.39 The emergent properties were hypothesized to arise from canted spins associated with a chirality-induced asymmetric lattice; however, more experiments are necessary to confirm such behavior.

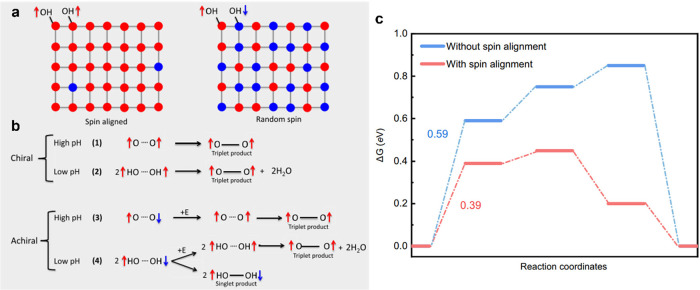

Spin-Dependent Electrocatalysis

A combination of measurements for spin-filtered currents and for water electrolysis demonstrate the usefulness of CISS for directing chemical heterogeneous chemical reactions through spin control (see Section 6.3.1).

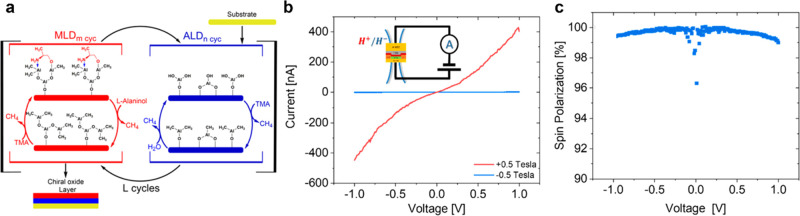

Nonmagnetic Oxide Spin Filters

Recent work by Al-Bustami et al. shows the promise of chiral metal oxides as spin filters in spintronic applications. By using atomic and molecular deposition techniques (see Figure 10), they created chiral Al2O3/organic hybrid films with a near 100% spin polarization.195 This represents the highest spin-polarized electron current, obtained via CISS, for a device structure.

Figure 10.

Panel a shows a schematic which illustrates the atomic molecular deposition super cycle repeated a total number of “L” times until a desired thickness is achieved. The deposition is composed of two subcycles; atomic layer deposition (blue) of alumina using trimethylaluminum and water repeated “n” times followed by dosing of the film (red) with d- or l-alaninol repeated “m” times. Panel b shows j–V characteristics of a device with a film fabricated using l-alaninol precursors for two different magnetic field directions; the inset illustrates the measurement circuit design. Panel c plots the resulting spin polarization as a function of bias potential. This figure is adapted from ref (195) with permission. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

3.2.6. Bulk Crystals and Organometallic Constructs

In the past five years, workers have shown that CISS phenomena are not restricted to ultrathin films and molecules but can also manifest in bulk solids.

3.2.6.1. Inorganic Chiral Crystals

Recent experiments on bulk crystals, ranging from insulators to semiconductors and metals, demonstrate that CISS-based, spin-polarized charge currents persist over micrometer to centimeter distances. Inui et al. first illustrated this fact for chiral CrNb3S6 bulk crystals by detecting the spin-polarized charge current by an inverse spin Hall signal (voltage drop).53 The Hall signal, and hence spin polarization, was found to depend sensitively on the current direction as well as the handedness of the chiral crystal. The spin polarization in these crystals persisted over micron length scales, much longer than that of conventional achiral materials with lower spin–orbit interactions,196 and were hypothesized to arise from antisymmetric spin–orbit interactions, i.e., the chiral materials did not exhibit normal spin-flipping processes. In follow-up experiments by the same group, the CrNb3S6 crystals were shown to manifest bulk magnetization when an electric current was applied along the principal chiral axis of the crystal.197 The presence of CISS in inorganic crystals is not limited to CrNb3S6 systems; recent studies have expanded the library of crystals to include chiral Te, NbSi2, and TaSi2;198−201 and theoretical works on SnIP double helices are argued to give rise to spin-dependent velocity asymmetries in electron transport as well.202

Spin Transport up to Centimeters

Studies on chiral crystalline rods of NbSi2 and TaSi2 demonstrate that chirality-based spin polarization can persist for centimeters in length.203

Inverse CISS Manifests

Studies using CrNb3S6 in device structures demonstrated the existence of an inverse CISS effect, i.e., a pure spin current induces a charge current.53

3.2.6.2. Chiral Metal–Organic Frameworks and Crystals

In a landmark paper by San Sebastian and co-workers, a paramagnetic metal–organic framework, composed of Dy(III)-tartrate, showed near-ideal spin-filtering capabilities (∼100%) and spin polarization in the charge transport persisting over 1 μm length scales.204 The remarkable performance was attributed to the large spin–orbit coupling of the Dy(III) lanthanides in tandem with the helicity of the metal–organic framework along multiple crystallographic directions, leading to multichannel spin-selective electron transmission. A similar behavior has also been observed in 300 nm thick Cu(II)phenyl alanine crystals, with mc-AFM measured polarizations up to ∼68%.205 Notably, these crystals display a transition from antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic at 50 K that was explained by the emergence of a low-lying thermally populated ferromagnetic state, which arises from interactions among Cu(II) species mediated by the chiral lattice. Newer work on Co(II)-phenylalanine crystals reports polarizations of 35–45%.206

Circular Dichroism (CD) as a Predictor

Comparisons between Cu(II)phenylalanine and Cu(II)pentafluoro-phenylalanine crystals show that the circular dichroism response of the crystal is a good predictor for the sign of the spin polarization, rather than the structural enantiomorph.205 This finding corroborates such correlations reported in nanomaterials, molecules, and supramolecular assemblies.

3.3. Summary

The diversity of chiral molecules, molecular assemblies, and materials support the notion that CISS arises from an underlying relationship between electron spin and chiral matter that manifests because of the chiral symmetry. The knowledge amassed from the numerous experiments is defining the criteria necessary for maximizing the CISS-response in a given system and researchers are already using them to realize spin polarization magnitudes in excess of 99%.195,204 The knowledge gained from experiments like those described in Sections 3 and 4 is necessary for understanding CISS and developing a comprehensive theory for CISS-based phenomena.

4. General Trends and Structure–Property Relationships

Although a quantitatively accurate mechanism for describing the CISS effect has yet to be identified, experimental work has begun to identify structure–property relationships for chiral molecules and materials that must be accounted for by a comprehensive theory. In this section we overview the different trends observed in experiments, comment on their pervasiveness, and identify important questions that must be addressed for continued progress in the field.

4.1. Length Dependence

For CISS, the most well-studied trend is the relationship between the length through which an electron traverses and the resulting spin polarization of its charge current. Systematic studies of DNA and oligopeptides, using a range of different techniques (photoemission spectroscopy, mc-AFM, electrochemistry, and Hall device measurements), show that spin-filtering of the charge currents increases monotonically with the length of the molecules.10,12,15,74,104,207 Most studies in molecular films and assemblies have been limited to a few tens of nanometers or less, however. For example, Mishra et al. examined the correlation between the length dependence of the optical activity and the spin-filtering performance of oligopeptides and DNA for film thicknesses <15 nm.104 Recently, Clever et al. analyzed CISS data on DNA and oligopeptides and found that the trend of increasing polarization with increasing length was consistent among independent studies, even though the absolute magnitude of the reported polarizations varied.43 The increase in spin-filtering performance per nucleobase in the case of DNA and per amino acid in the case of peptides are different, however.

In addition to these studies on molecular systems, studies on chiral organic–inorganic perovskite films168 and studies through different thicknesses of chiral polymer films150 display an increase in spin polarization for thin films and then plateaus at large film thickness. Although it seems likely that phonons and structural imperfections in molecular assemblies would reduce the spin polarization above a certain length, recent experiments on the spin filtering of electron currents through chiral polymer films indicate that the spin polarization does not decrease strongly with increasing film thickness. Figure 11 shows electropolymerized chiral films of poly(2-vinylpyridine) in which the spin polarization increases monotonically up to a thickness of ∼120 nm, even though the chiral polymer strands in the film are disordered with respect to each other.

4.2. Effect of Chirality Type

Molecules manifest chirality through stereoisomerism, which includes planar chirality, axial chirality and/or helical chirality, and point chirality, which arises through dissymmetry in bond connectivity about an atomic center (typically carbon). Although CISS manifests for all of the chiral types, responses for axial or helical chirality appear to dominate over others in organic systems. For instance, mc-AFM measurements on single-stranded DNA yields no discernible spin polarization, whereas polarizations as high as 57% were found for double-stranded DNA.10 Similarly, Stremer et al. introduced a Hg chelating unit to single-stranded DNA, which creates a chiral secondary structure, and observed the emergence of a spin polarization.31 The effect of helical structure on spin polarization was also observed for peptide-nucleic acids (PNAs). PNA with modified backbones, in which the monomer units become chiral, create helices with a shorter pitch length and result in higher spin polarizations than their unmodified counterparts.40 These studies also imply that point and structural chirality of a material may be synergistic. Possible evidence of this synergy is shown by measurements on B-DNA, for which the helix and the stereocenters along the backbone are both right-handed. B-DNA exhibits larger spin polarizations than do measurements on Z-DNA, for which the helix is left-handed and the stereocenters along the backbone are still right-handed.102 Unfortunately, the helicity of B-DNA and Z-DNA is different and so a clear distinction on the underlying mechanism cannot yet be made. Also the effect of helicity on spin polarization was shown for a series of peptides that were systematically altered through amino acid substitution at fixed oligopeptide length.43 Here, the spin polarization increased sequentially with the increased helical content of the peptide. Because of the similar composition between peptides, this system is ideal for exploring the relationship between helicity and differences in length dependence on spin polarization.

4.3. CISS Manifests for Individual Molecules