Abstract

Periprosthetic hip infection caused by Brucella abortus is rare and only a few cases have been reported. This current case report presents a case of a man in his early 50s who developed periprosthetic hip infection 2 years after right hip arthroplasty. There was no fever or pain, the usual cardinal signs of infection, except for a sinus tract at the previous surgical incision. Laboratory and arthrocentesis culture examinations (done twice) confirmed infection with B. abortus. Accordingly, a two-stage revision surgery was performed accompanied by antibiotic treatment with doxycycline and rifampicin after each stage. There was no recurrence at the 2-year follow-up, with good functional recovery of the hip joint. Clinically, this case serves to highlight the fact that periprosthetic hip infections caused by B. abortus might not present with the typical symptoms such as fever or hip pain. Furthermore, this current case involved a chronic sinus tract, so the diagnostic and therapeutic course of this case offers useful insights for managing similar cases in the future. In addition, a review of the literature on the diagnosis and treatment of Brucella-caused periprosthetic hip infection is presented.

Keywords: Brucella abortus, periprosthetic joint infection (PJI), doxycycline, revision arthroplasty, case report

Introduction

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a serious complication of arthroplasty and the incidence of PJI after hip arthroplasty ranges from 0.5% to 2%. 1 The most common bacteria involved in PJI are coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Staphylococcus aureus. 2 Brucella-associated PJI is extremely rare, with only a few cases of Brucella periprosthetic hip infections reported in the literature. 3 This current report describes a rare case of Brucella infection of the hip PJI with sinus tract that was treated with two-stage revision surgery and a combination of antibiotics.

Case report

In June 2017, a 51-year-old male patient underwent right total hip arthroplasty for alcoholic femoral head necrosis in Ziyang People’s Hospital, Ziyang City, Sichuan Province, China. There were no obvious signs of infection during the initial hip replacement surgery and the patient recovered well after the operation. Over the next 2 years, the patient had no symptoms of cough, fever, chills or hip pain and had no history of exposure to pastoral or infectious diseases. In July 2019, the patient was admitted to the Department of Orthopaedics, Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China after developing a sinus tract that oozed fluid in his right hip for more than 1 month. Upon physical examination, his body temperature was 36.2°C. A sinus tract (approximately 2 cm × 1 cm in size) was formed in the middle section of the scar from the previous operation on the right hip (Figure 1). The right hip joint could be flexed and extended (0°–90°) with no significant pain on movement. Laboratory tests on admission revealed a normal white blood cell count (4.87 × 109/l) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level (2.94 mg/l). However, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was increased (39 mm/h). Plain hip radiographs showed no definite loosening of the femoral prosthesis (Figure 2). Two consecutive right hip punctures were performed and the arthrocentesis fluid (only approximately 1 ml of liquid was extracted each time) was immediately cultured using blood culture bottles, both of which grew Brucella abortus (reported positive at 65 and 73 h, respectively). Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci (MRCNS) susceptible to vancomycin and ciprofloxacin were cultured from the sinus tract exudate. These investigations revealed a periprosthetic infection caused by Brucella abortus with a sinus tract formation. A combination of bacterial infections such as MRCNS could not be ruled out.

Figure 1.

Preoperative appearance of a sinus tract (white arrow) of approximately 2 cm × 1 cm in size in the scar on the right hip of a 53-year-old male patient that had undergone right total hip arthroplasty for alcoholic femoral head necrosis 2 years previously. The colour version of this figure is available at: http://imr.sagepub.com.

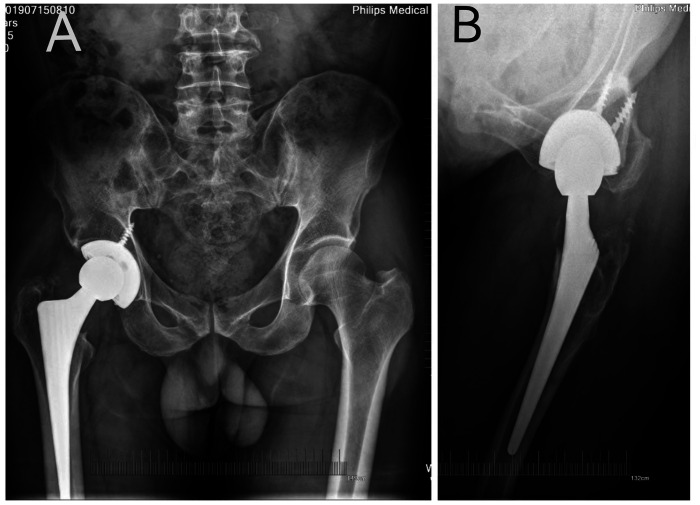

Figure 2.

Preoperative plain pelvic anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of the right hip showing no definitive evidence of prosthetic loosening in a 53-year-old male patient that had undergone right total hip arthroplasty for alcoholic femoral head necrosis 2 years previously.

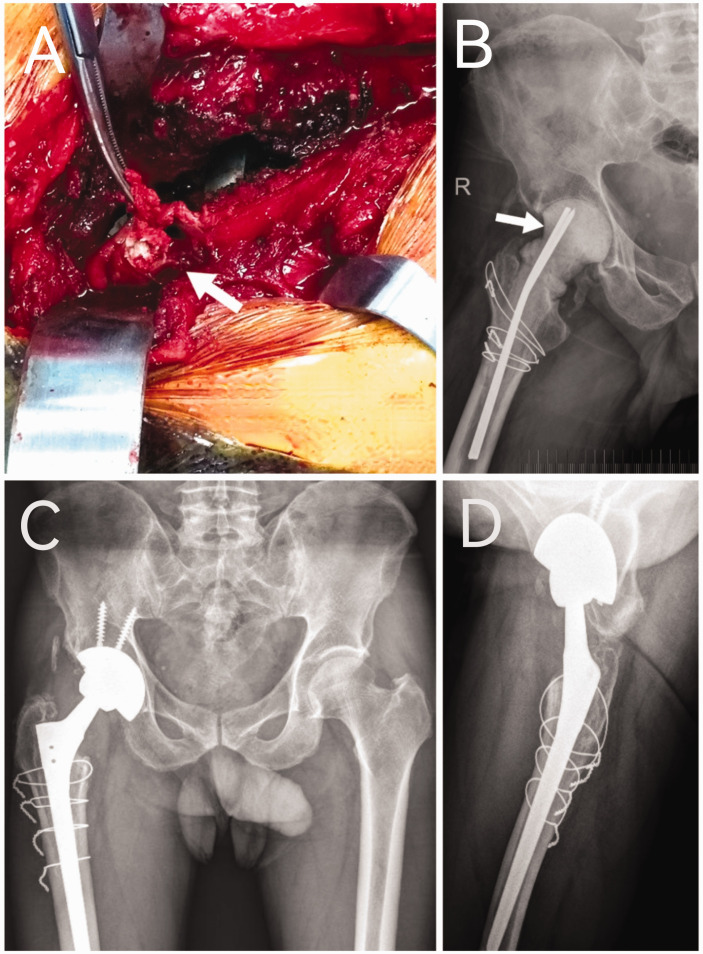

The patient underwent two-stage revision arthroplasty. During the first stage revision surgery, the sinus tract was visible in the middle portion of the original posterolateral incision and was connected to the joint cavity reaching the upper part of the acetabulum. Caseous tissue formation was visible at the base of the sinus tract (Figure 3a) and the articular cavity was filled with inflammatory synovial tissue; approximately 2 ml of joint effusion was observed and this was sent for bacterial culture. The proximal posterolateral femur showed a 5 cm long and 2 cm wide area of bone erosion and destruction, which was replaced by inflammatory granulation tissue. The sinus tissue, the inflammatory synovial tissue from the joint cavity and the periarticular scar tissue were thoroughly removed until the wound was freshly bleeding. The femoral prosthesis was found to be stable. Next, an extended trochanteric osteotomy was performed to remove all of the prosthetic components and the wound was soaked with Iodophor and rinsed three times with hydrogen peroxide and saline.

Figure 3.

Caseous tissue (white arrow) was seen in the supraacetabular area during the first-stage revision surgery (a) in a 53-year-old male patient that had undergone right total hip arthroplasty for alcoholic femoral head necrosis 2 years previously. A plain radiograph showing the bone cement spacer (white arrow) that was placed during the first-stage revision (b). Two-year postoperative follow-up plain pelvic anteroposterior (c) and lateral (d) radiographs of the right hip confirmed no manifest recurrence of infection. The colour version of this figure is available at: http://imr.sagepub.com.

After debridement, a vancomycin bone cement spacer was made by pouring 8 g of vancomycin powder (Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA) into 80 g bone cement powder (PALACOS MV + G, contains gentamicin; Heraeus Medical GmbH, Wehrheim, Germany) and mixing evenly. After making the bone cement spacer in a mould, it was placed into the femur (Figure 3b). The greater trochanter osteotomy block was reset and fixed with steel wire. Two plasma drainage tubes were placed and the wound was sutured. The following anti-infective treatment plan was developed after consultation with a clinical pharmacist based on the results of the bacterial drug sensitivity test: 0.1 g doxycycline oral twice a day, 0.45 g rifampicin oral once a day, 1 g vancomycin intravenous (i.v.) every 12 h and 0.2 g ciprofloxacin i.v. every 8 h. B. abortus was cultured again in the intraoperative joint fluid 5 days later. Two weeks later, the patient was discharged and continued on the following antibiotic drug regime: 0.5 g levofloxacin oral once a day, 0.45 g rifampicin oral once a day and 0.1 g doxycycline oral twice a day taken sequentially for 3 months postoperatively. Serum inflammatory markers and liver and kidney functions were reviewed regularly.

At the 4-month outpatient follow-up visit after the first-stage surgery, there was no redness, swelling and no significant or noteworthy pressure pain in the right hip. The blood results of the routine blood examination, CRP levels and ESR were also within normal ranges for three consecutive tests, so the patient was admitted to the hospital for the second-stage revision surgery. Intraoperatively, approximately 8 ml of light red fluid was extracted before incising the joint capsule and injected into a blood culture bottle for bacterial culture; no caseous tissue was found in the joint. The Zimmer acetabular cup (56 mm), a high-molecular polyethylene liner, a ceramic femoral head (32 mm) and a Wagner SL femoral stem (14/225) were placed; and the original greater trochanter osteotomy block was fixed with 4 wire-ties. The same anti-infection treatment plan as before was followed. Postoperative radiographs confirmed the good placement of the prosthesis. Postoperative rehabilitation was initiated the day after surgery. The joint fluid culture result was negative on day 5 postoperatively. The surgical wound healed well after the surgery and the patient recovered normally. He was discharged from the hospital and planned for regular outpatient review with no recurrence of infection. At the 2-year postoperative follow-up, the laboratory tests were also within normal limits, and the radiographs confirmed no recurrence of infection manifested in the right hip (Figures 3c & 3d). There was good functional recovery, with a Harris hip score of 95.

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was given by the Ethics Committee of the Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China (no. 232 of 2019). Informed consent for treatment was obtained from the patient. Informed consent for publication of this case report and any accompanying images was also obtained from the patient. In this case report, all patient details have been deidentified to protect the privacy and confidentiality of the individual. No personal information that could lead to the identification of the patient has been included in this report. The reporting of this study conforms to CARE guidelines. 4

Discussion

Periprosthetic hip infection caused by Brucella is very rare, with only 12 cases reported in the literature.5–14 The characteristics of these cases are summarized in Table 1. The patients included eight men and four women with a mean age of 61 years. Radiographic evidence of definite prosthetic loosening was found in eight of 12 cases (66.7%). Eleven patients underwent surgery (91.7%), including nine second-stage revisions (66.7%), one first-stage revision (8.3%) and one drainage procedure (8.3%). All cases were treated with doxycycline-based combination anti-infective therapy. During the follow-up period, there was no recurrence of infection in any of the cases.

Table 1.

Summary of the reported cases of Brucella prosthetic hip infection in the literature.5–14

| Author | Age, years | Sex | Symptom | Radiography | Joint fluid culture | Agglutination titre | Surgical treatment | Duration of anti-infection treatment, months | Follow-up, years | Good outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones et al., 1983 5 | 54 | M | Fever | No loosening | Negative | 640 | One-stage exchange | 12 | 3 | Yes |

| Ortega-Andreu et al., 2002 6 | 63 | M | Hip pain | Loosening of femoral component | No | NA | Two-stage exchange | 3 | 0.5 | Yes |

| Weil et al., 2003 7 | 38 | M | Hip pain fever | Loosening of femoral component | Negative | 1600 | Two-stage exchange | 1.5 | 1 | Yes |

| Kasim et al., 2004 8 | 47 | F | Hip pain | Loosening | No | 80 | Two-stage exchange | 5 | 4 | Yes |

| Ruiz-Iban et al., 2006 9 | 66 | F | Thigh pain groin pain | Radiolucent lines | Positive | NA | Two-stage exchange | 1.5 | 5.5 | Yes |

| Ruiz-Iban et al., 2006 9 | 71 | M | Painless | No loosening | No | 640 | Drainage | 6 | 5 | Yes |

| Cairo et al., 2006 10 | 50 | M | Hip pain | No loosening | No | 320 | None | 26 | 5 | Yes |

| Cairo et al., 2006 10 | 71 | M | Hip pain, limping | Implant Loosening | No | NA | Two-stage exchange | 6 | 3 | Yes |

| Tena et al., 2007 11 | 51 | M | Hip pain, fever | Implant loosening | Positive | 80 | Two-stage exchange | 2 | 4 | Yes |

| Carothers et al., 2015 12 | 67 | F | Thigh pain | Bone loss around cement | Negative | NA | Two-stage exchange | 5 | 2 | Yes |

| Tebourbi et al., 2016 13 | 73 | F | Hip pain | Acetabular component loosening | No | NA | Two-stage exchange | 3 | 2 | Yes |

| Walsh et al., 2019 14 | 75 | M | Hip pain, Sinus tract | Bone loss around cement and acetabular component loosening | No | NA | Two-stage exchange | 3 | NA | Yes |

M, male; NA, not available; F, female.

Most of these previous cases had symptoms such as hip pain, thigh pain and fever.5–14 The current patient had none of these symptoms and only presented with a sinus tract at the original incision scar on the hip. The sinus exudate was cultured for other bacteria, suggesting the possibility of a mixed bacterial infection, which has not been previously reported. This situation was associated with a high risk of treatment failure.

Brucellosis is a zoonotic infectious disease. The bacterium has strong resistance in the natural environment and can even survive in the excreta of diseased animals for approximately 120 days. 15 Human Brucellosis is usually caused by ingestion of unpasteurized infected animal products or via contact with infected animal fluids or tissues. 16 PJIs caused by Brucella are extremely rare, especially in non-pastoral populations. This current patient had no history of exposure to infected areas, contact with Brucella-infected patients or cattle, or use of unsterilized beef. However, he had a hobby of fishing, for which he used cattle manure to feed earthworms as bait and often experienced the fishhooks piercing the skin of his fingers. This transmission through the infected animal fluids was a possibility. Brucella infections usually have symptoms of pain and fever, but the current case did not present with these symptoms. His only symptom consisted of a sinus tract from the original surgical scar that oozed fluid, which highlights the fact that Brucella infections might not have the typical symptoms of fever and joint pain.

The commonly used tests for diagnosing a Brucella infection include the standard test tube agglutination test, Brucellacapt® test, indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, fluorescence polarization test and blood culture methods. 17 In the current patient, Brucella infection was not initially considered and was diagnosed based on the bacterial culture results of the arthrocentesis fluid. The positivity rate of Brucella culture in arthrocentesis fluid is approximately 50%. 7 In the current case, Brucella was cultured twice from preoperative arthrocentesis fluid and it is suggested that arthrocentesis and timely culture inoculation using blood culture bottles can improve the positivity rates. 18 It is worth noting that serological tests will be recommended for follow-up of the case. 17

Treating PIJs begins with ascertaining the pathogenic organism. This current patient had a sinus tract in the original surgical area, which is known to cause retrograde infection and the development of mixed bacterial infections. In this current case, additional cultures of MRCNS were found in the sinus tract secretions, so a combination of bacterial infections such as MRCNS could not be ruled out. Although it was possible that the bacterial culture results from the superficial sinus tract secretions were not consistent with those from deep synovial fluid, 19 given that the presence of chronic sinus tracts leads to an increased incidence of mixed infections 20 and an increased failure rate of revision surgery, the presence of co-infections was considered to be a possibility in the current case and vancomycin was used for anti-infective purposes based on the drug susceptibility results. The drugs of choice for Brucella infection are doxycycline, rifampicin and streptomycin. 21 In the current patient, a combination of drugs was used based on the results of other bacterial drug sensitivity tests as follows: oral doxycycline and rifampicin and i.v. vancomycin and ciprofloxacin for 2 weeks postoperatively; followed by sequential oral levofloxacin, rifampicin and doxycycline for 3 months postoperatively. Besides doxycycline and rifampicin, ciprofloxacin is known as a second-line agent against Brucella, 22 which exhibited anti-Brucella action and also worked against the other two bacteria for this current case. There is no standardized antibiotic course for PJI caused by Brucella, with the shortest reported antibiotic regimen of 6 weeks and the longest of 26 months. 3 The current patient was cured by a combination of antibiotics given for 3 months after each step of the revision surgery. Diligent research is warranted to determine the optimal course of anti-Brucella drug treatment.

It has been reported that Brucella species can produce biofilms in vitro, 23 but whether Brucella biofilms form on the surface of artificial joint prostheses has not been reported. Therefore, surgical treatment options, including the retention of prosthetic, debridement and revision (one-stage or two-stage), 3 are inconclusive; and there have even been reports of successful treatment with medication alone. 24 In this current case, a mixed infection needed to be considered. Therefore, two-stage revision surgery was planned. The key to successful surgery is thorough debridement, which requires the removal of scar tissue, entire sinus tract tissue and intraarticular synovial tissue to achieve fresh bleeding of the wound. Furthermore, Brucella can be transmitted through aerosols, 25 so extreme attention should be paid to the protection of healthcare personnel involved in the treatment process. Face shields, medical masks and waterproof surgical gowns are required.

In conclusion, Brucella hip PJI infections are rare. This current case highlights the fact that periprosthetic hip infections caused by Brucella may not present with typical symptoms such as fever or hip pain. Furthermore, this current case involved a chronic sinus tract. The diagnostic and therapeutic course of this current case offers useful insights for managing similar cases in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Microbiology and Pharmacology Departments of Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital for their dedicated advice and assistance in the diagnosis of this case.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J.W.F. performed the follow-up examinations and wrote the manuscript with the assistance of P.H. and Y.W.; and X.D. helped to revise the manuscript. J.H. provided administrative support. All authors contributed to the drafting and final approval of the manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD: Jun Wei Feng https://orcid.org/0009-0001-9724-0371

References

- 1.Hubert J, Beil FT, Rolvien T, et al. Restoration of the hip geometry after two-stage exchange with intermediate resection arthroplasty for periprosthetic joint infection. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 5221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tai DBG, Patel R, Abdel MP, et al. Microbiology of hip and knee periprosthetic joint infections: a database study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022; 28: 255–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SJ, Park HS, Lee DW, et al. Brucella infection following total joint arthroplasty: A systematic review of the literature. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2018; 52: 148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Headache 2013; 53: 1541–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones RE, Berryhill WH, Smith J, et al. Secondary infection of a total hip replacement with Brucella abortus. Orthopedics 1983; 6: 184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortega-Andreu M, Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Aguera-Gavalda M. Brucellosis as a cause of septic loosening of total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2002; 17: 384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weil Y, Mattan Y, Liebergall M, et al. Brucella prosthetic joint infection: a report of 3 cases and a review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36: 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasim RA, Araj GF, Afeiche NE, et al. Brucella infection in total hip replacement: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis 2004; 36: 65–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Iban MA, Crespo P, Diaz-Peletier R, et al. Total hip arthroplasty infected by Brucella: a report of two cases. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2006; 14: 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cairo M, Calbo E, Gomez L, et al. Foreign-body osteoarticular infection by Brucella melitensis: a report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88: 202–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tena D, Romanillos O, Rodriguez-Zapata M, et al. Prosthetic hip infection due to Brucella melitensis: case report and literature review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2007; 58: 481–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carothers JT, Nichols MC, Thompson DL. Failure of total hip arthroplasty secondary to infection caused by Brucella abortus and the risk of transmission to operative staff. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015; 44: E42–E45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tebourbi A, Hadhri K, Ben Salah M, et al. Prosthetic Hip Loosening Due to Brucellar Infection: Case Report and Literature Review. Reconstructive Review 2016; 6: 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh J, Gilleece A, Fenelon L, et al. An Unusual Case of Brucella abortus Prosthetic Joint Infection. J Bone Jt Infect 2019; 4: 277–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unuvar GK, Kilic AU, and Doganay M. Current therapeutic strategy in osteoarticular brucellosis. North Clin Istanb 2019; 6: 415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, et al. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 2325–2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suo B, He J, Wu C, et al. Comparison of different laboratory methods for clinical detection of Brucella infection. Bull Exp Biol Med 2021; 172: 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes HC, Newnham R, Athanasou N, et al. Microbiological diagnosis of prosthetic joint infections: a prospective evaluation of four bacterial culture media in the routine laboratory. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17: 1528–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tetreault MW, Wetters NG, Aggarwal VK, et al. Should draining wounds and sinuses associated with hip and knee arthroplasties be cultured? J Arthroplasty 2013; 28: 133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis B, Ford A, Holzmeister AM, et al. Management of Periprosthetic Hip and Knee Joint Infections With a Known Sinus Tract-A Single-Center Experience. Arthroplast Today 2021; 8: 124–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shakir R. Brucellosis. J Neurol Sci 2021; 420: 117280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alavi SM, Alavi L. Treatment of brucellosis: a systematic review of studies in recent twenty years. Caspian J Intern Med 2013; 4: 636–641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almirón MA, Roset MS, Sanjuan N. The aggregation of Brucella abortus occurs under microaerobic conditions and promotes desiccation tolerance and biofilm formation. Open Microbiol J 2013; 7: 87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis JM, Folb J, Kalra S, et al. Brucella melitensis prosthetic joint infection in a traveller returning to the UK from Thailand: case report and review of the literature. Travel Med Infect Dis 2016; 14: 444–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Traxler RM, Lehman MW, Bosserman EA, et al. A literature review of laboratory-acquired brucellosis. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51: 3055–3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]