Abstract

The objective of this study is to describe survival outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma in a real-world setting receiving combination and single-agent immunotherapy outside the clinical trial context. We conducted a retrospective single-institution study of patients with metastatic melanoma in a real-world setting. Survival was calculated using log-rank test. Contingency tables were analyzed using Fisher’s Exact test. CD8 + T-cell densities were measured using quantitative immunofluorescence and analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test. The median overall survival (OS) for 132 patients was 45.3 months. Brain metastasis did not confer a higher risk of death relative to liver and/or bone disease (39.53 versus 30.00 months, respectively; P = 0.687). Anti-PD-1 monotherapy was the most common first-line treatment, received by 49.2% of patients. There was no significant difference in OS between patients receiving single-agent anti-PD-1 and combination anti-PD-1 plus CTLA-4 (39.4 months versus undefined; P = 0.643). Patients treated with combination therapy were more likely to be alive without progression at the last follow-up than those who received monotherapy (70.4% versus 49.2%; P = 0.0408). Median OS was 21.8 months after initiation of second-line therapy after anti-PD-1 monotherapy. CD8+ T-cell densities were higher in patients who achieved disease control on first-line immunotherapy (P = 0.013). In a real-world setting, patients with metastatic melanoma have excellent survival rates, and treatment benefit can be achieved even after progression on first-line therapy. Combination immunotherapy may produce more favorable long-term outcomes in a real-world setting. High pretreatment CD8+ T-cell infiltration correlates with immunotherapy efficacy.

Keywords: CTLA-4, immune checkpoint inhibitors, immunotherapy, melanoma

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have dramatically improved rates of overall survival (OS) for patients with metastatic melanoma [1–4]. Ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody (mAb), received approval in 2011 from the USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in advanced melanoma after demonstrating significant improvement in OS when compared to chemotherapy [1,5]. Pembrolizumab and nivolumab, two anti-PD-1 mAb, were FDA-approved in 2014 [2,3]. The 2017 CheckMate 067 clinical trial demonstrated that a combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab improved survival for advanced melanoma compared with either agent alone [6–9]. Notably, 6 years of follow-up was required to demonstrate the benefit of adding anti-CTLA-4 to upfront anti-PD-1, with OS benefit demonstrated in 2022 after initial inconclusive results published in 2015, 2018, and 2019, suggesting that benefits of combination therapy are not readily apparent but emerge over time [6]. However, the combination had a significantly higher incidence of toxicity (58% versus 21% for nivolumab); despite this, it was associated with a higher quality of life [9–11]. Additionally, a systematic review and meta-analysis, the OTHERS study, found a benefit of prolonged ICI administration beyond 2 years compared to a fixed 2-year schedule in patients with melanoma [12]. Most recently, humanized, immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) mAb directed against the inhibitory receptor lymphocyte activation gene 3 protein (anti-lag3) has gained FDA approval. There is currently no data proving that anti-lag3 improves OS, although benefit in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) has been established [13,14].

Patients with poor performance status and lower disease burdens may benefit from either single-agent or combination immunotherapy upfront, and selection is often clinically dependent. This is largely because, while combination immunotherapy improves survival, adding anti-CTLA-4 to a regimen is perceived by clinicians to increase risk of life-altering toxicities [15,16]. While these toxicities may be well-tolerated by patients enrolled in clinical trials, patients in real-world situations may experience higher rates of dose-limiting toxicities. Fewer than 5% of cancer patients enroll in clinical trials, and many patients who would be excluded from clinical trials are currently being medically treated. Another difference between trial and clinic patients is the patients enrolled in clinical trials wherein survival benefit was proven did not always have ready access to second-line combination immunotherapy that could be given immediately upon progression on single-agent treatment. Finally, combination therapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab may not be cost-effective for all patients [17]. Thus, it is not readily apparent that the survival benefit observed in trials of combination immunotherapy would be applicable to patients in a real-world setting due to the potential for increased toxicity in less fit populations or populations with limited disease burden.

A second area of interest in clinical practice is how to manage patients who progress on anti-PD-1 therapy, either alone or in combination, particularly if the patient does not carry a BRAF mutation. The standard second-line therapy used in clinical trials as a comparator is single-agent anti-CTLA-4, which in a recent randomized trial yielded a median PFS of 3.1 months and OS of 18.9 months, performing inferiorly to tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy with a PFS of 7.2 months and OS of 35.8 months [18]. Adding complexity to management is the well-documented phenomenon of responses to anti-PD-1 treatment after disease progression or with re-induction, supported by data suggesting the potential benefits of prolonged anti-PD-1 therapy [19,20]. Therefore, some practitioners may favor continuing or re-introducing anti-PD-1 after progression or possibly including additional FDA-approved therapies such as targeted therapies, radiation, or talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC). The efficacy of these multimodality therapies is unknown, and it is unproven whether anti-PD-1 or other therapies add benefit to second-line anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy.

The primary objective of this retrospective single-institution study is to describe patterns of disease progression and survival for patients treated for metastatic melanoma in the real-world setting with a focus on evaluating the benefit of combination and single-agent ICI upfront as well as second- and third-line treatments for patients who progress on initial therapy. Patients had overall favorable outcomes, consistent with what was observed in clinical trials with a median OS of 45.3 months, undefined in patients with M1a or M1b disease. No significant difference in survival was observed based on the initial choice of single-agent immunotherapy or combination immunotherapy. However, there was a trend towards improved survival in patients receiving combination immunotherapy first line with a ‘tail of the curve’ observed. Further, patients treated upfront with combination immunotherapy had a significantly greater likelihood of ongoing response at time of last follow-up. Patients with M1d disease (brain metastasis) had survival curves virtually identical to patients without brain metastasis. Complete responses (CRs) were observed with second- and third-line therapy, and median OS after progression on anti-PD-1 for patients who received any second-line therapy was 22.5 months with some durable responses achieved. These results document the dramatic shift in survival observed with modern immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma patients in a real-world setting and highlight the value of intensive and continued immunotherapy for melanoma.

Methods

Patient cohort

Data for patients with metastatic melanoma treated at Columbia University Irving Medical Center from January 1st, 2011 to July 1st, 2021 were reviewed. The cutoff date was September 1st, 2021. The inclusion criteria were stage IV metastatic melanoma or unresectable stage III metastatic melanoma (based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system 8th edition) with diagnosis confirmed by histopathology. Patients with inaccessible medical records, uveal melanoma, sparsely-documented treatment histories due to poor compliance or follow-up at other institutions, or unclear date of death were excluded.

Data collection

This retrospective cohort study was conducted under an IRB approved at Columbia University Medical Center and at Montefiore Einstein Cancer Center. Patient and disease characteristics were retrospectively gathered from NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital’s electronic medical record. Collected data included patient demographics, date of initial diagnosis, date of first metastasis, stage at initial diagnosis, metastasis stage (AJCC 8th edition, using anatomical sites only), metastasis sites, mutation status, treatments administered, and survival. Treatments were categorized by mechanism into anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4, combination ICI, non-IMI (interferon or T-VEC), BRAF and/or MEK targeted inhibition, and chemotherapy. Up to three lines of treatment were recorded for each patient, because, in clinical practice, very few patients receive beyond three lines. Surgical resection and radiation therapy, if performed, were recorded separately. Tumor response to treatment was characterized according to the best response indicated by routine radiological evaluation or clinician determination using the revised response evaluation criteria in solid tumors. The date of last follow-up or death was determined based on the most recent appointment scheduled with any department or the recorded date of death, respectively. The date of transfer to hospice care served as a substitute if an exact date of death was unobtainable.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 9. Kaplan Meyer curves were generated in GraphPad Prism using log-rank and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon tests. For smaller cohort analysis, Fisher exact tests were utilized. Mann-Whitney tests were also conducted. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Patient demographics and outcomes

A total of 132 patients were included in our analysis (Table 1). The median age was 75 years, and 65% were men. At the time of data collection, 46% of patients were deceased. Of the patients, 20% had only lymph node or soft tissue metastasis (unresectable IIIc or M1a, n = 27), 12% had only lung metastasis (M1b, n = 16), 26% had other visceral sites of disease (M1c, n = 34), and 42% had brain metastasis (M1d, n = 55). Of the patients with M1c disease, 33% had metastases to liver, 24% to both bone and the liver, 18% to bone, and 26% to other distant organs excluding the central nervous system. BRAF mutations were found in 34% of patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| (n = 132) | |

|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 86 (65.2) |

| Female | 46 (34.8) |

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 75 (32-102) |

| Deceased | 60 (45.5%) |

| Stage (AJCC 8th edition), n (%) | |

| IIIC or M1A | 27 (20) |

| M1b | 16 (12) |

| M1c | 34 (26) |

| Bone | 6 (17.6) |

| Liver | 11 (32.5) |

| Bone and liver | 8 (23.5) |

| Other | 9 (26.4) |

| M1d | 55 (42) |

| CNS only | 31 (56.4) |

| CNS and liver | 11 (20) |

| CNS and bone | 5 (9.1) |

| CNS, liver, and bone | 8 (14.5) |

| Mutational status,n (%) | |

| BRAF mutant | 45 (34) |

| BRAF wild type | 81 (61) |

| Unknown | 6 (5) |

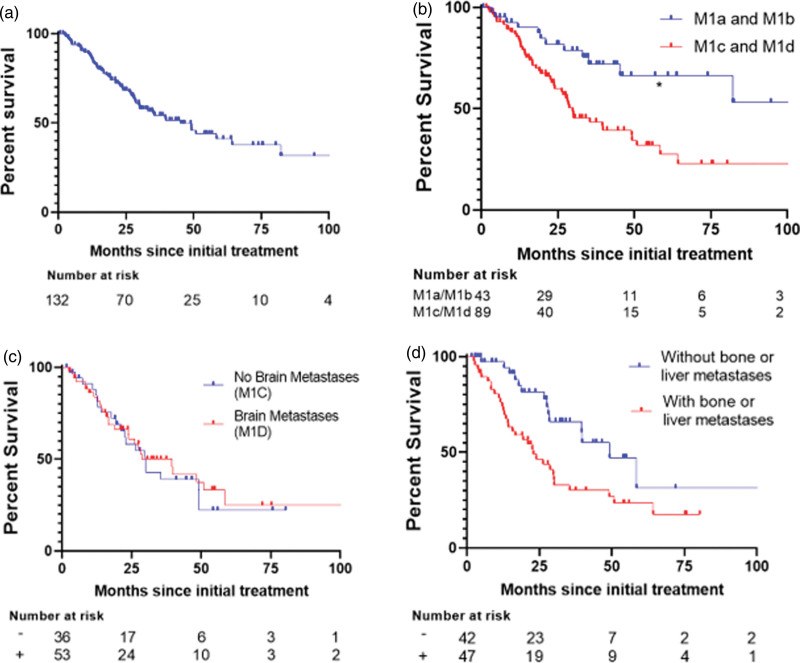

The overall median disease-specific survival (DSS) was 45.3 months (Fig. 1a). Median DSS for patients with stage IIIC, M1a, or M1b disease (n = 41) was not reached (NR), whereas it was 29.83 months for patients with M1c or M1d disease (n = 89) (HR = 0.3632, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1b). Median DSS was similar between patients with and without brain metastases (28 months among M1d versus 30 months among M1c, respectively; P = 0.96) (Fig. 1c). Within the combined M1c and M1d group, the presence of either liver or bone metastasis correlated with shortened survival of 22.9 months versus 49.17 months, respectively (P = 0.0072) (Fig. 1d). The presence of liver or bone metastasis alone trended towards decreased survival (P < 0.06) (Supplements A and B, Supplemental digital content 1, http://links.lww.com/MR/A362). In summary, overall median survival approached 4 years, and the presence of brain metastasis did not confer significantly inferior survival.

Fig. 1.

Melanoma-specific survival (DSS) Kaplan-Meier survival curves. (a) Curve for all patients (medial DSS 45.3 months). (b) Comparing survival between stage M1a and M1b versus M1c and M1d (HR = 0.3632, P < 0.001). (c) Comparing survival between M1c versus M1d (P = 0.687). (d) Comparing survival without bone or liver metastasis versus with either (P = 0.0072).

Comparison of first-line anti-PD-1 monotherapy versus combination anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4

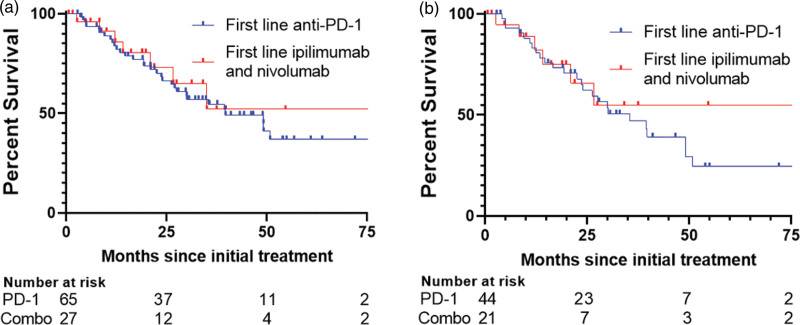

Every patient received systemic treatment for metastatic melanoma. Anti-PD-1 monotherapy was the most common first-line treatment, administered in 56.06% (n = 74) of cases. The combination of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1, specifically ipilimumab and nivolumab (thereafter, ‘combination ICI’), was the second commonest, given to 21.21% (n = 28) of patients. Other treatments included T-VEC, BRAF/MEK inhibitors, C-kit inhibitors, anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy, and chemotherapy. Most patients who received combination ICI first-line treatment had M1d disease (57%), and only one had no visceral mets (M1a). There was no significant difference in median OS among those who received anti-PD-1 compared to those who received combination ICI (39.7 versus NR, respectively, P = 0.642) (Fig. 2a); this was also true for patients with M1c or M1d disease (35.4 versus NR, P = 0.574; Fig. 2b). 50% of patients with M1c or M1d disease who were treated with combination ICI were alive at last follow up. A significantly higher percentage of total patients who received combination ICI had ongoing response at last follow-up than patients who received anti-PD-1 monotherapy (70.4% versus 46.1%, P = 0.0406; Table 2). However, there was no significant difference in the initial CR rate between single-agent anti-PD-1 and combination ICI (P = 0.332; Table 2). There was an overall trend in all stages toward a higher percentage of patients alive at last follow-up with combination ICI as compared with single-agent anti-PD-1 (74% versus 54%, P = 0.0651).

Fig. 2.

Melanoma-specific survival curves for patients who received immunotherapy as first-line treatment stratified by monotherapy versus combination therapy. (a) Curves for all patients. (b) Curves for patients with M1c or M1d disease.

Table 2.

Complete and ongoing response rates

| Initial complete response, n (%) | Ongoing response, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-PD-1 monotherapy (n = 65) | 19 (29.2%) | 30 (46.1%) |

| Anti-CTLA-4 + Anti-PD-1 (n = 27) | 11 (40.7%) | 19 (70.4%) |

| P = 0.332 | P = 0.041 |

Responses to second- and third-line therapy

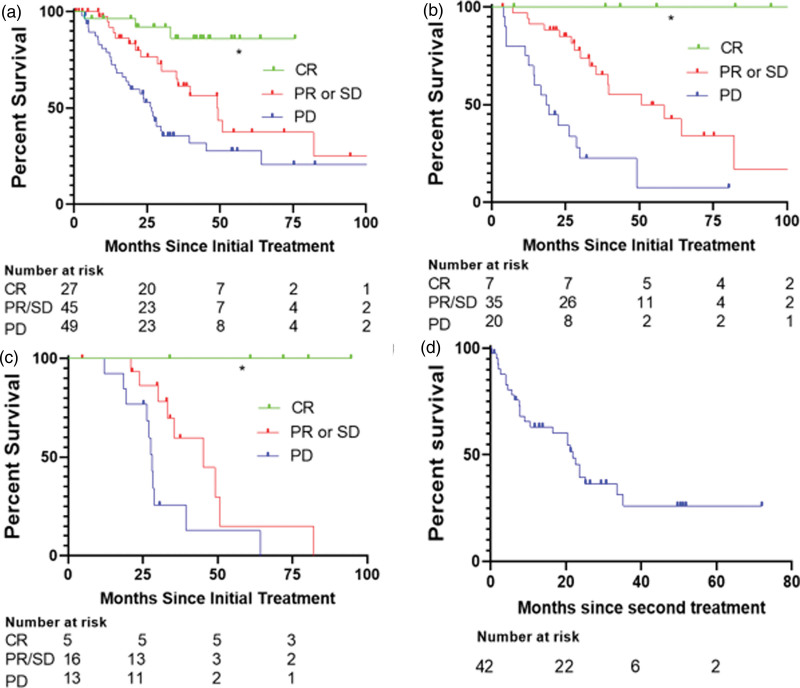

Analysis of treatment data documented responses and durable survival after each line of therapy (Fig. 3). CR was achieved in 22.7% of 132 patients after first-line treatment, 7.8% of 90 patients after second-line treatment, and 11.3% of 53 patients after third-line treatment. Comparing best responses on first-line treatment with ICI revealed that patients who achieved CR had the longest median survival, whereas patients with progressive disease (PD) experienced the shortest median survival (CR: NR; PR or SD: 49.13 months; PD: 26.67 months; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3a). This was true for patients who received ICI as second-line (CR: NR, PR or SD: 45.30 months, PD: 19.37 months, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3b) or third-line treatment (CR: NR, PR or SD: 49.13 months; PD: 27.03 months, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Overall survival for patients stratified by disease outcomes. (a) Survival based on response to first-line immunotherapy. (b) Survival based on response to second-line immunotherapy. (c) Survival based on response to third-line immunotherapy. (d) Survival after using first-line anti-PD-1.

The benefit of second- and third-line therapy was next evaluated in the patients who received anti-PD-1 monotherapy as the first regimen (Fig. 3d). The literature documents anti-CTLA-4 as standard second-line therapy with a median survival of 18.9 months for 84 patients with unresectable stage IIIC-IV disease, and we aimed to compare our real-world population with this standard. Of patients receiving first-line anti-PD-1 therapy, 4 died without receiving further treatment, and 19 achieved a durable response, leaving 42 who received a second-line therapy. The median survival for these latter patients was 21.8 months from the time of initiation of the second regimen. The most common second-line treatment regimens observed in our subset of patients who initially received anti-PD-1 were a combination anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 (n = 11) and BRAF/MEK inhibition (n = 11). Additional regimens consisted of immunotherapy combinations including T-VEC (n = 8), re-induction with anti-PD-1 alone (n = 4), anti-CTLA-4 alone (n = 3), combination targeted therapy and immunotherapy (n = 2), imatinib (n = 1), and chemotherapy (n = 1). Patients treated with first-line combination anti-PD-1 and ant-CTLA-4 therapy who received a second-line regimen experienced a similar median OS of 20.1 months. Taken together, this data suggests that there is benefit to continued therapy after failure of first-line ICI and that continuing anti-PD-1 therapy after progression is a reasonable strategy in some cases.

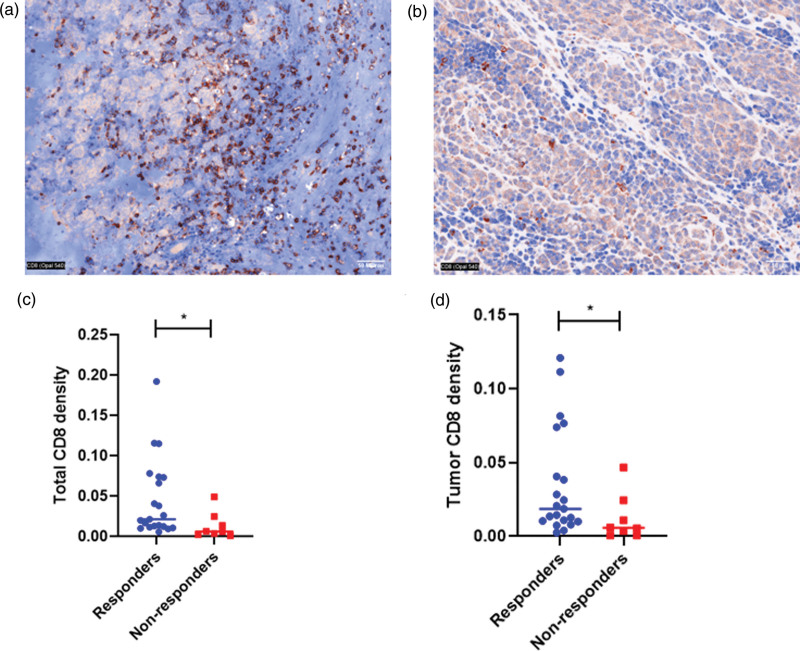

CD8+ quantification as a biomarker for disease control

The correlation between CD8+ T-cell infiltration and response to first-line immunotherapy was evaluated. Tissue from a pretreatment metastatic biopsy site, including brain, was available for analysis for 29 patients. Patients were characterized as responders if their disease did not progress after 3 months of treatment with first-line immunotherapy. Quantitative multiplex immunofluorescence was performed (Fig. 4a and b). Median total CD8 density was 0.021 per total number of cells in view among responders and 0.006 among non-responders (P = 0.013) (Fig. 4c). Median tumor CD8 density was 0.019 per total number of cells in view among responders and 0.006 among non-responders (P = 0.032) (Fig. 4d). These data show that CD8+ T-cell quantification may serve as a potential predictor of benefit from immunotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Quantitative multiplex immunofluorescence of CD8+ T cells in metastatic biopsies from (a) responder patients and (b) non-responders to immunotherapy. (c) Total CD8+ T cell counts in tumors stratified by responder and non-responders (d) Tumor CD8+ T cell counts in patient tumors stratified by responder and non-responders.

Discussion

In this retrospective study of outcomes in metastatic melanoma in a single academic center between 2011 and 2021, OS was 45.3 months, comparable to those observed in clinical trials conducted during this time period, highlighting the applicability of immunotherapy for melanoma to real-world populations. For comparison, at the 6.5-year follow-up timepoint for Checkmate 067 conducted from July 2013 through March 2014, the median OS was 19.9 months, 36.9 months, and 72.1 months for patients treated with single-agent anti-CTLA-4, single-agent anti-PD-1, and combination therapy, respectively [6]. Further, a broader patient population was included in our analysis, including patients with brain metastasis, autoimmune disease, and/or organ transplantation who would have been excluded from the registrational studies. Most likely due to the presence of an active neurosurgery program at the institution where this study was conducted, 41.7% of patients had brain metastasis as compared with less than 5% in Checkmate 067 [4]. Notably, no patient death in this subset of this study was due to a known immune-related adverse event. These results highlight the dramatic benefits of modern therapies, particularly immunotherapy, in a real-world setting, even for patients with multiple comorbidities and advanced melanoma.

Our data is in line with other real-world studies of efficacy of immunotherapy in advanced melanoma [21,22]. Similar OS data was reported in the only large multi-center retrospective study of patients who received combined anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 between 2015 and 2020. In that study, out of 697 patients, there were only 4 treatment-related deaths, OS was 53.7 months in treatment-naïve patients without brain metastasis, and there was a non-significant trend towards decreased survival for patients with and without brain metastasis, a group including 29% of treatment-naive patients with brain metastases [21]. Our results further confirm that melanoma brain metastasis is treatable with immunotherapy in a real-world setting and support including patients with brain metastasis in clinical trials. In our cohort, 94.8% of patients with brain metastasis received irradiation in addition to immunotherapy, which may have further contributed to a relatively favorable OS.

Real-world comparisons between single-agent and combination immunotherapy are fraught because of the length of follow-up required to document improvements in OS seen with the combination regimen. Further differences in melanoma survival based on local or regional factors make it challenging to compare data across studies and even between different centers in retrospective studies. This can be compounded by clinician preference to treat lower-stage patients with less toxic regimens. A large registry study of 787 patients treated in Italy between 2010 and 2018 showed that treatment with single-agent anti-PD-1 (n = 80) versus combination immunotherapy (n = 41) yielded a non-significantly different DSS (70 versus 58 months) [23]. Large retrospective trials have yielded ambiguous results in some cases when direct comparisons are made between single and combination therapy [16]. For clinicians in clinical practice, it can feel difficult to justify combination therapy for some patients because, as shown in the data presented here, survival is very good with monotherapy and differences in response are not readily apparent. This is particularly true for clinicians who see limited numbers of patients with advanced melanoma. However, it was intriguing that in our small sample, although CR rates were virtually identical, a significantly higher percentage of patients treated upfront with combination immunotherapy were alive and in response than patients treated with a single-agent regimen, suggesting that the survival advantage of combination therapy may be applicable in real-world settings.

Patients who received first-line single-agent anti-PD-1 in this study experienced prolonged survival even after second- and third-line therapy. Notably, the survival achieved in this real-world population exceeded the survival reported in a second-line study population receiving ipilimumab. This is consistent with data from other studies; a single-arm study of second-line combination pembrolizumab and ipilimumab after first-line anti-PD-1 reported a median OS of 24.7 months and a response rate of 29% [24,25]. Further, responses to re-induction with anti-PD-1 have been documented [20,26], and there is evidence to suggest that maintaining patients on anti-PD-1 long-term after combination immunotherapy prolongs survival [27]. Therefore, the data reported here is consistent with the observation that patients can respond well to second-line therapy including anti-PD-1 even after progression on this same agent and suggests that consideration of including anti-PD-1 in second-line regimens is warranted. Further, the prolonged survival should be somewhat reassuring to patients who progress on first-line immunotherapy.

The correlation of CD8+ T-cell infiltrates to immune responsiveness is well-known, but no CD8+ biomarkers are available for use in clinical practice [28]. Interestingly, this study found that biopsies of metastatic disease from widely divergent organs from patients who did not progress after 3 months of treatment with first-line immunotherapy had higher density of CD8+ T-cells than metastatic biopsies from patients who progressed. This suggests that a high CD8+ T-cell count may be a strong predictor of response to immunotherapy in standard clinical practice, particularly if density is calculated specifically rather than qualitatively graded. Quantification of CD8+ T-cells in larger populations might be developed into a useful clinical tool. Given that PD-L1 is not an excellent marker for response to immunotherapy in melanoma, evaluation of CD8+ T-cell density may be useful in some clinical settings to estimate the likelihood of therapeutic benefit of immunotherapy.

In summary, this data provides a real-world analysis of clinical outcomes in one academic practice. The results are based on a sample set of 132 patients and therefore not conclusive; further evaluation of larger samples is warranted. We find that the improved survival benefits of immunotherapy are readily apparent, particularly in patients with brain metastasis. Although no significant difference in OS was observed between combination and single-agent immunotherapy, longer-term ongoing response data shows some evidence that combination immunotherapy may provide superior outcomes to single-agent immunotherapy in standard settings as previously demonstrated in the 6.5-year follow-up to Checkpoint 067 [6]. Furthermore, this study suggests that there may be a benefit in continuing therapy with anti-PD-1 even after progression, and in some cases, including anti-PD-1 in the treatment plan is advisable. Finally, quantification of CD8+ T-cells has potential as a biomarker in standard clinical practice in melanoma.

Acknowledgements

Source of funding: R01CA160375 and UH3CA218149.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Brian Ko and Kevin Tao contributed equally to the writing of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.melanomaresearch.com.

References

- 1.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, Hodi FS, Gutzmer R, Neyns B, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015; 16:375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV, Arance A, Grob J-J, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival results of a multicentre, randomised, open-label phase 3 study (KEYNOTE-006). Lancet. 2017; 390:1853–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodi FS, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, Robert C, Grossmann KF, McDermott DF, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma: 2-year overall survival outcomes in a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016; 17:1558–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O’Day S, Weber J, Garbe C, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:2517–2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob J-J, Rutkowski P, Lao CD, et al. Long-term outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022; 40:127–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larkin J, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:1270–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodi FS, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob J-J, Rutkowski P, Cowey CL, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067): 4-year outcomes of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018; 19:1480–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob J-J, Rutkowski P, Lao CD, et al. Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1535–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larkin J, Del Vecchio M, Mandala M, Gogas H, Arance Fernandez AM, Dalle S, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage iii/iv melanoma: 5-year efficacy and biomarker results from checkmate 238. Clin Cancer Res. 2023; 29:3352–3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph RW, Liu FX, Shillington AC, Macahilig CP, Diede SJ, Dave V, et al. Health-related quality of life (QoL) in patients with advanced melanoma receiving immunotherapies in real-world clinical practice settings. Qual Life Res. 2020; 29:2651–2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogani G, Cinquini M, Signorelli D, Pizzutilo EG, Romanò R, Bersanelli M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the optimal treatment duration of checkpoint inhibitors in solid tumors: the others study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023; 187:104016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tawbi HA, Hodi FS, Long GV. Nivolumab with or without relatlimab in untreated advanced melanoma reply. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386:1860–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boutros A, Tanda ET, Croce E, Catalano F, Ceppi M, Bruzzone M, et al. Activity and safety of first-line treatments for advanced melanoma: a network meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2023; 188:64–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarhini A, Atzinger C, Gupte-Singh K, Johnson C, Macahilig C, Rao S. Treatment patterns and outcomes for patients with unresectable stage III and metastatic melanoma in the USA. J Comp Eff Res. 2019; 8:461–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ugurel S, Rohmel J, Ascierto PA, Flaherty KT, Grob JJ, Hauschild A, et al. Survival of patients with advanced metastatic melanoma: the impact of novel therapies-update 2017. Eur J Cancer. 2017; 83:247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh A, Tran DM, McDowell LC, Keyvani D, Barcelon JA, Merino O, et al. Cost-effectiveness of nivolumab-ipilimumab combination therapy compared with monotherapy for first-line treatment of metastatic melanoma in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017; 23:653–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohaan MW, Borch TH, van den Berg JH, Met O, Kessels R, Geukes Foppen MH, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy or ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2022; 387:2113–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asher N, Israeli-Weller N, Shapira-Frommer R, Ben-Betzalel G, Schachter J, Meirson T, et al. Immunotherapy discontinuation in metastatic melanoma: lessons from real-life clinical experience. Cancers (Basel). 2021; 13:3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipson EJ, Sharfman WH, Drake CG, Wollner I, Taube JM, Anders RA, et al. Durable cancer regression off-treatment and effective reinduction therapy with an anti-PD-1 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2013; 19:462–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serra-Bellver P, Versluis JM, Oberoi HK, Zhou C, Slattery TD, Khan Y, et al. Real-world outcomes with ipilimumab and nivolumab in advanced melanoma: a multicentre retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2022; 176:121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asher N, Ben-Betzalel G, Lev-Ari S, Shapira-Frommer R, Steinberg-Silman Y, Gochman N, et al. Real world outcomes of ipilimumab and nivolumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancers (Basel). 2020; 12:2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crispo A, Corradin MT, Giulioni E, Vecchiato A, Del Fiore P, Queirolo P, et al.; Clinical National Melanoma Registry Study Group at the Italian Melanoma Intergroup. Real life clinical management and survival in advanced cutaneous melanoma: the Italian clinical national melanoma registry experience. Front Oncol. 2021; 11:672797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olson DJ, Eroglu Z, Brockstein B, Poklepovic AS, Bajaj M, Babu S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus ipilimumab following anti-PD-1/L1 failure in melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021; 39:2647–2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blake Z, Marks DK, Gartrell RD, Hart T, Horton P, Cheng SK, et al. Complete intracranial response to talimogene laherparepvec (T-Vec), pembrolizumab and whole brain radiotherapy in a patient with melanoma brain metastases refractory to dual checkpoint-inhibition. J ImmunoTher Cancer. 2018; 6:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koch EAT, Petzold A, Wessely A, Dippel E, Gesierich A, Gutzmer R, et al. Immune checkpoint blockade for metastatic uveal melanoma: re-induction following resistance or toxicity. Cancers (Basel). 2; 14:518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maloney G-H, Fogarasi O, Hodi S, Silk H, Liu IB. Role of nivolumab maintenance therapy in advanced melanoma patients following severe immune-related adverse events from combination nivolumab and ipilimumab. ASCO Annual Meeting. Chicago; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJM, Robert L, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014; 515:568–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.