Abstract

Purpose:

The International Committee for the Classification of Corneal Dystrophies (IC3D) was created in 2005 to develop a new classification system integrating current information on phenotype, histopathology, and genetic analysis. This update is the third edition of the IC3D nomenclature.

Methods:

Peer-reviewed publications from 2014 to 2023 were evaluated. The new information was used to update the anatomic classification and each of the 22 standardized templates including the level of evidence for being a corneal dystrophy [from category 1 (most evidence) to category 4 (least evidence)].

Results:

Epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophies now include epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophy, category 1 (COL17A1 mutations, chromosome 10). Signs and symptoms are similar to Franceschetti corneal dystrophy, dystrophia Smolandiensis, and dystrophia Helsinglandica, category 4. Lisch epithelial corneal dystrophy, previously reported as X-linked, has been discovered to be autosomal dominant (MCOLN1 mutations, chromosome 19). Classic lattice corneal dystrophy (LCD) results from TGFBI R124C mutation. The LCD variant group has over 80 dystrophies with non-R124C TGFBI mutations, amyloid deposition, and often similar phenotypes to classic LCD. We propose a new nomenclature for specific LCD pathogenic variants by appending the mutation using 1-letter amino acid abbreviations to LCD. Pre-Descemet corneal dystrophies include category 1, autosomal dominant, punctiform and polychromatic pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy (PPPCD) (PRDX3 mutations, chromosome 10). Typically asymptomatic, it can be distinguished phenotypically from pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy, category 4. We include a corneal dystrophy management table.

Conclusions:

The IC3D third edition provides a current summary of corneal dystrophy information. The article is available online at https://corneasociety.org/publications/ic3d.

Key Words: corneal dystrophy, inherited corneal diseases, cornea, cornea pathology, genetic disease

WHAT IS THE IC3D?

IC3D First Edition History

The International Committee for the Classification of Corneal Dystrophies (IC3D) was created in 2005 to address the difficulties presented by the antiquated nomenclature for corneal dystrophies and to correct errors embedded in the literature.1 The goal was to create a new classification system that would retain some aspects of traditional corneal dystrophy nomenclature while incorporating new genetic, clinical, and pathologic information.

It had been well recognized that incorrect nomenclature increased the difficulty of correct diagnosis. Over a decade earlier, 1 author (J.S.W.) suggested changing the name of Schnyder crystalline corneal dystrophy to Schnyder corneal dystrophy (SCD) precisely because misdiagnosis was caused by the deceptive nomenclature.2 Because only 50% of patients with SCD actually had corneal crystals, the 50% of patients without crystals were repeatedly misdiagnosed. Owing to the name, many ophthalmologists and ophthalmic pathologists assumed that the presence of corneal crystals was an integral requirement for diagnosis. Consequently, patients with both clinical and/or histopathologic findings of SCD often escaped correct clinical diagnosis because they lacked the corneal crystals described in the original dystrophy name.3 This was only 1 of many examples of challenges presented by the antiquated dystrophy nomenclature.

The underlying problem was that the original nomenclature began in 1890, before the invention of the slit lamp and more than a century before genetic mapping became available.4,5 Although our knowledge base had markedly expanded, the nomenclature system remained static. An update of the outdated nomenclature was long overdue.

The initial and subsequent IC3D committees comprised clinicians, pathologists, and geneticists with first-hand knowledge of the corneal dystrophies. One-page summary “templates” for each dystrophy were written containing a “brief summary of the current genetic, clinical and pathologic information about the disease and representative images.”1 At the same time, the IC3D committee also corrected errors that had been perpetuated in the literature. One of the goals of the initial nomenclature revision was not only to devise a new nomenclature that was both accurate but also “flexible enough to facilitate the expansion of knowledge from other sources including genotyping.”1 The new nomenclature published in 2008 was well received. At the time of the writing of this article, it had been cited 245 times according to the Clarivate Analytics Web of Science. By 2015, continued expansion of the corneal dystrophy knowledge base mandated the publication of the IC3D second edition.6

Corneal Dystrophy—Problems With the Historic Definition

In the first edition of the IC3D, we explained that “the term ‘corneal dystrophy’ has been used to refer to a group of inherited corneal diseases that are typically bilateral, symmetric, slowly progressive and without relationship to environmental or systemic factors.”1 However, we also acknowledged that there were exceptions to each part of the definition. Some patients with posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) only had unilateral changes, so PPCD could be asymmetric. Fleck corneal dystrophy (FCD) was an example of a corneal dystrophy that was nonprogressive. Immunophenotypes of macular corneal dystrophy (MCD) were classified by the level of antigenic serum keratan sulfate, which suggested a systemic factor was associated. Both epithelial basement membrane dystrophy (EBMD) and central cloudy dystrophy of François (CCDF) did not seem to have hereditary patterns. Consequently, it was likely these 2 conditions were not corneal dystrophies and instead were corneal degenerations. We concluded that “the separation of entities into the category called corneal dystrophies may have more historical than practical meaning. There remains no consensus as to the precise definition of corneal dystrophy, but according to custom, we have chosen to primarily deal with the entities formerly called corneal dystrophies.”1 Although we conclude that EBMD and CCDF are likely corneal degenerations rather than inherited corneal diseases, it would be exceptionally challenging to change decades of teaching and publications by excluding these from the list of corneal dystrophies. As we observed in the first edition of the IC3D, “once established in textbooks, it is exceedingly difficult to purge incorrect information.”1 We have decided that the more practical approach, currently, is to continue to include these entities in the list of corneal dystrophies, while at the same time indicating that the lack of heredity suggests these are degenerations.

IC3D Corneal Dystrophy Categories

A category system was suggested by Professor Gordon K. Klintworth MD, PhD, to indicate the level of evidence supporting the existence of a given corneal dystrophy depending on how substantive was the knowledge of its clinical, pathologic, and genetic basis.1 He proposed that the existence of a new corneal dystrophy must begin with identification of a clinical phenotype and should progress to characterization of the causative gene mutation(s).

“An example of a monogenic category 1 dystrophy is SCD which is caused by mutations in 1 gene, UBIAD1. Another category 1 dystrophy, posterior amorphous corneal dystrophy (PACD) is caused by deletion of multiple genes, keratocan (KERA), lumican (LUM), decorin (DCN), and epiphycan (EPYC). The genetic basis of other dystrophies, such as some types of Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD), seems to be complex and involves multiple genes.”6

These categories were specified as follows:

“Category 1: A well-defined corneal dystrophy in which the gene has been mapped and identified and the specific mutations are known.”

“Category 2: A well-defined corneal dystrophy that has been mapped to one or more specific chromosomal loci, but the gene(s) remain to be identified.”

“Category 3: A well-defined corneal dystrophy in which the disorder has not yet been mapped to a chromosomal locus.”

“Category 4: This category is reserved for a suspected, new, or previously documented corneal dystrophy, although the evidence for it, being a distinct entity is not yet convincing.”1

It was postulated that as our knowledge about a dystrophy increased, the category should progress over time from 4 to 3 to 2 to 1. Conversely, “Suspected dystrophies that remain category 4 because no further information ever becomes available may be eventually removed from the nomenclature. The group did not further specify specific criteria for removal of category 4 dystrophy.”1

IC3D Second Edition

The second edition of the IC3D was published in 2015 because of the continued increase in the knowledge base of corneal dystrophies.6 In addition to clinical photographs included in the first edition, pathology images were now also included.6 Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED) was reclassified. Literature review had revealed that many and possibly all 5 families previously described to have autosomal dominant CHED (CHED1) most likely had PPCD.7–9 Consequently, CHED1 was removed from the nomenclature and autosomal recessive CHED, previously called CHED2, was renamed CHED. Another change was the introduction of a new anatomic subcategory, the epithelial-stromal TGFBI dystrophies. For the first time, corneal dystrophy nomenclature would be guided by genetics. All corneal dystrophies known to map to the TGFBI gene would be included in 1 category instead of the former approach of separating these into either Bowman layer or stromal dystrophies. The new epithelial-stromal TGFBI anatomic category facilitated explanation of why the dystrophies in this group had some overlap of the clinical signs, symptoms, and histopathologic changes.

Another change was the removal of the category 4, Grayson-Wilbrandt corneal dystrophy, from the IC3D classification. The category system allowed for a removal of a category 4 corneal dystrophy “in which no further information to prove or disprove its existence is forthcoming.”1 IC3D considered this an equivalent of “corneal dystrophy purgatory.” Grayson-Wilbrandt dystrophy was described in only 1 publication in 1966, supported by an artist rendition of the changes. There were no photographs or genotyping, and there were no subsequent articles over the following 5 decades. Consequently, Grayson-Wilbrandt corneal dystrophy was consigned to a category entitled “Removed Dystrophies” (Table 1).10 If a future publication substantiates its existence, the reference publication is easily retrievable, and it can be “resurrected from purgatory.”

TABLE 1.

The IC3D Classification

| Category (C) | |

| Epithelial and subepithelial dystrophies | |

| 1. Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy (EBMD) | C3 |

| 2. Epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophies (EREDs) | |

| Epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophy (ERED) | C1 |

| Franceschetti corneal dystrophy (FRCD) | C4 |

| Dystrophia Smolandiensis (DS) | C4 |

| Dystrophia Helsinglandica (DH) | C4 |

| 3. Subepithelial mucinous corneal dystrophy (SMCD) | C4 |

| 4. Meesmann corneal dystrophy (MECD) | C1 |

| 5. Lisch epithelial corneal dystrophy (LECD) | C1 |

| 6. Gelatinous drop-like corneal dystrophy (GDLD) | C1 |

| Epithelial-stromal TGFBI dystrophies | |

| 1. Reis–Bücklers corneal dystrophy (RBCD) | C1 |

| 2. Thiel–Behnke corneal dystrophy (TBCD) | C1 |

| 3. Lattice corneal dystrophies (LCDs) | |

| Classic LCD | C1 |

| LCD variants | C1 |

| 4. Granular corneal dystrophy, type 1 (GCD1) | C1 |

| 5. Granular corneal dystrophy, type 2 (GCD2) | C1 |

| Stromal dystrophies | |

| 1. Macular corneal dystrophy (MCD) | C1 |

| 2. Schnyder corneal dystrophy (SCD) | C1 |

| 3. Congenital stromal corneal dystrophy (CSCD) | C1 |

| 4. Fleck corneal dystrophy (FCD) | C1 |

| 5. Posterior amorphous corneal dystrophy (PACD) | C1 |

| 6. Central cloudy dystrophy of François (CCDF) | C4 |

| 7. Pre-Descemet corneal dystrophies (PDCDs) | |

| Pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy (PDCD) | C4 |

| Punctiform and polychromatic pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy (PPPCD) | C1 |

| Endothelial dystrophies | |

| 1. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) | C1, C2, or C3 |

| 2. Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) | C1 |

| 3. Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED) | C1 or C3 |

| 4. X-linked endothelial corneal dystrophy (XECD) | C2 |

| Removed dystrophies | |

| 1. Grayson-Wilbrandt corneal dystrophy (GWCD) | C4 |

IC3D Third Edition

The continued rapid expansion of corneal dystrophy knowledge suggested it was time for yet another update, reflected in this current third edition of IC3D. The revision includes new category 1 corneal dystrophies such as epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophy (ERED) and likely an entirely new category 1 corneal dystrophy, punctiform and polychromatic pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy (PPPCD), including its mutated gene (Table 1).

EPITHELIAL RECURRENT EROSION DYSTROPHIES: THE IMPORTANCE OF GENOTYPE

Most clinicians diagnose a specific corneal dystrophy solely on the basis of history and phenotype, and they do not or cannot obtain genetic analysis. As such, the IC3D corneal dystrophy nomenclature system is still primarily based on phenotype. Unfortunately, the lack of objective genotypic confirmation of the ophthalmologist's clinical impression has the disadvantage of not knowing whether the clinician's phenotypic assessment is correct or incorrect.

Epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophy (ERED) provides such an example. ERED was introduced in the first edition of IC3D as a new template to encompass Franceschetti corneal dystrophy (FRCD) and dystrophia Smolandiensis (DS), believed to be a variant of the former.1 FRCD was category 4, and DS was category 3, both primarily characterized by recurrent corneal erosions without other corneal findings beginning in the first decade of life. The second edition of IC3D introduced an updated template called the epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophies (EREDs) after introduction of a further entity, dystrophia Helsinglandica (DH).6 Each of these 3 autosomal dominant dystrophies had been characterized by recurrent erosions in childhood with no corneal findings between attacks. By adulthood, corneal opacification with decreased vision could occur while erosion frequency diminished and possibly ceased. Although there was no gene or gene locus identified for any of the described EREDs, it was noted that “The difference in severity of corneal opacification in FRCD, DS, and DH could be explained by the presence of polymorphism and difference in expressivity of a common gene.”6

Subsequent to the publication of the IC3D second edition, another corneal dystrophy, with similar symptoms and signs as FRCD, DH, and DS, was described by Jonsson et al who identified the associated abnormal gene as COL17A1. They classified this corneal dystrophy as epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophy (ERED).11

In 1997, almost a decade prior, Yee et al12 had diagnosed a Bowman layer dystrophy mapping to 10q23-24 as Thiel–Behnke corneal dystrophy (TBCD). This observation was controversial because although there was possibly some phenotypic similarity, TBCD was previously known to only be associated with mutations on the TGFBI gene on chromosome 5. The IC3D group was skeptical, and in the second edition, the group wrote “we believe that there is insufficient evidence to consider this a variant of TBCD. Is it a distinct dystrophy?” Our observation proved to be prescient. Subsequently, Jonsson et al provided evidence that the abnormal gene in this dystrophy was also COL17A1.11 Consequently, this corneal dystrophy, initially believed to be TBCD, was actually ERED.13 Genotyping provided the necessary information to correct the misdiagnosis based on phenotype alone. Subsequently, ERED, resulting from mutations in COL17A1, has been reported in several countries.

The ERED story is an example of the importance of genotype. Only genotype can assist in confirming or refuting the phenotypic diagnosis. The TBCD/ERED saga also demonstrates the necessity of requiring a high level of evidence before deciding that there is a distinct genetic causation for a previously known corneal dystrophy. This evidence ideally includes examination of the cornea through a dilated pupil and examination of multiple generations of a family.14–16

The Evolution of the EREDs Template

After the discovery of ERED in 2015 from mutations in the COL17A1 gene, the logical question was whether FRCD, DS, and DH mapped to this same gene. Unfortunately, there are no publications regarding this information. Personal communication from Dr. Irina Golovleva (Umeå, Sweden) suggests that DH maps to COL17A1, implying that DH and ERED may be the same dystrophy. While we suspect that FRCD and DS may also map to COL17A1, until published confirmation is attained, the EREDs template includes the category 1 corneal dystrophy ERED and corneal dystrophies of FRCD, DH, and DS demoted to category 4. If future studies demonstrate that COL17A1 is the responsible gene for these dystrophies, we may have substantiation for concluding these are different names for the same entity, called ERED.

EPITHELIAL-STROMAL TGFBI CORNEAL DYSTROPHIES

Initially, corneal dystrophies were named on the basis of inheritance, phenotype, and when available, histopathology.17,18 The addition of the epithelial-stromal TGFBI dystrophies anatomic category in the second edition of IC3D facilitated the opportunity to think about these corneal dystrophies genotypically rather than just phenotypically. For example, although Reis–Bücklers corneal dystrophy (RBCD) and granular corneal dystrophy type 1 (GCD1) have distinct mutations on TGFBI, both dystrophies are autosomal dominant, can develop recurrent erosions, show bright red deposits with Masson trichrome, and demonstrate rods on transmission electron microscopy. Although the phenotypes of RBCD and GCD1 are very different, the overlap in symptoms, signs, and histopathology is easily explained because both corneal dystrophies map to the same gene.

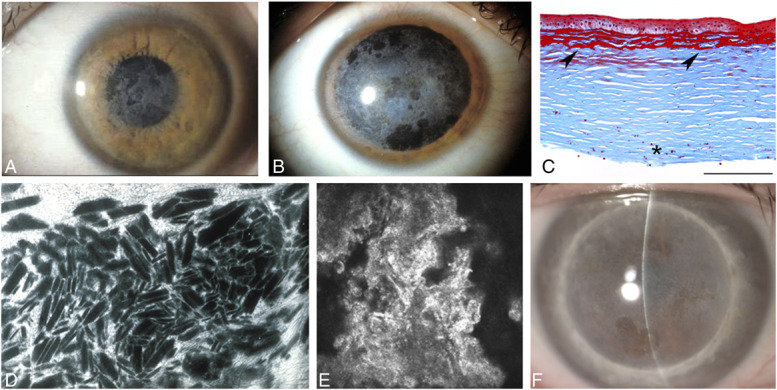

The Lattice Corneal Dystrophy Variants Compared with Classic Lattice Corneal Dystrophy

Since the introduction of the epithelial-stromal TGFBI category, this category has continued to grow in importance because of the ongoing discovery of dystrophies with distinct TGFBI mutations. These often have similar, though not identical, phenotypes to the TGFBI dystrophies that had already been described before discovery of their shared genetic background. For example, while classic lattice corneal dystrophy (classic LCD) is associated with the R124C mutation in the TGFBI gene, the expanding group called LCD variants in the IC3D nomenclature results from other distinct TGFBI mutations with clinical findings often similar though not identical to classic LCD. Although their phenotypes are typically reminiscent of classic LCD, some LCD variants lack distinct lattice lines, causing difficulty in making the clinical diagnosis. By histopathology, all LCD variants demonstrate corneal amyloid deposition as their primary diagnostic feature, although some may have minor deposits of keratohyalin. When compared with classic LCD, which is geographically widely spread and reported in 5 continents, known LCD variants are currently relatively geographically restricted. While classic LCD is caused by the R124C pathogenic variant in the first FAS1 domain of the TGFBI protein (earlier known as keratoepithelin), LCD variants are caused by several dozen distinct heterozygous amyloidogenic TGFBI variants that, with rare exceptions, localize to the fourth FAS1 domain of TGFBI. Over 80 LCD variants have already been published (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Lattice Corneal Dystrophy Variants

| DNA Change | Protein | Exon | FAS1 | Earliest Onset (Decade) | Erosions | Depth | Lines | Reported as | Clinical Description | Countries/Ethnicity | Clinical Publications (Listed by PMID) | Experimental Publications (Listed by PMID) |

| c.370C>T | p.R124C | 4 | 1 | Early 1st | Yes | All eventually | Thin | LCDI | See LCD template (classic LCD) | Australia; Bangladesh; Brazil; Bulgaria; Canada; China; France; Greece; Germany; Hungary; India; Japan; Mexico; Singapore (Malay descent); Spain; Switzerland; Turkey; Ukraine; the United Kingdom; the United States | 9054935, 9463327, 9497262, 9559741, 9592740, 9886734, 10798644, 10832717, 10844062, 11024425, 11095060, 11262611, 11146721, 11297504, 11413412, 11741113, 11923233, 11927442, 12138697, 12072720, 12225829, 12586172, 12770961, 15013897, 15017378, 15564760, 15623763, 16008913, 16118514, 16329070, 16380889, 16809844, 16710170, 16331487, 17063427, 16440005, 17768377, 17846354, 17982422, 18470323, 18615206, 19001012, 19062536, 19350511, 20161820, 20360992, 20664689, 20680100, 20806046, 21921985, 21462384, 21887843, 21835759, 22355247, 22773977, 22876129, 24801599, 25055147, 25876897, 25785536, 25932442, 26949635, 26748743, 27348782, 27737463, 27829782, 28393022, 28358433, 29085627, 30098247, 30805211, 31555324, 33513810, 34937214, 35484844, 35985662 | 21948648, 22080335, 23861389, 25557343, 26207300, 30387319 |

| c.1486C>T | p.R496W | 11 | 3 | Late 9th | No | Mainly deep | Minor | LCDIV | Corneal haze with many isolated or fused refractile opacities, mostly dots, some lattice lines, mainly in deep stroma | Japan | 20974628 | |

| c.1501C>A | p.P501T | 11 | None | Late 7th | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thick | LCDIIIA Japanese | Asymmetric; late-developing thick ropy lattice lines; linear thick branching rod-like opacities from limbus to limbus and discrete nodular deposits; thick ropy lattice lines | China; Japan; South Korea | 9497262, 10218700, 10832717, 11004271, 11024425, 11501939, 12400061, 16809844, 21462384, 23884333, 26748743 | |

| c.1504A>G | p.M502V | 11 | 4 | Late N/A | N/A | Unclassifiable | N/A | LCD atypical | Unclassifiable phenotype because of extensive corneal opacifications, 32-year-old daughter with small round, refractive deposits predominately in the anterior stroma | Mexico | 19303004 | |

| c.1514T>A | p.V505D | 11 | 4 | Early 1st | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thin | LCDI | Symmetrical opacities more prominent in the central cornea, in younger patients a few thin lattice lines anteriorly and axially with light central stromal clouding, with increasing age opacities spread posteriorly and centrifugally, 1–2 mm clear peripheral zone | China | 15838722 | |

| c.1526T>C | p.L509P | 11 | 4 | Early 2nd | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thin | LCDI; LCDIIIA; RBCD | Cloudy and geographic primarily subepithelial opacities, small granules in anterior stroma; confluent irregular and coarse geographic subepithelial and anterior stromal opacities; diffuse subepithelial opacities in direct illumination, paracentral stromal lattice lines in retroillumination; a network of thick lattice lines and dots; diffuse grayish-white subepithelial deposits, distinct refractile lattice lines spreading to the periphery; geographic opacities at Bowman layer level, lattice lines in deeper layers | France; Germany; South Korea | 19001012, 21617751, 25055147, 26748743, 35683443 | |

| c.1526T>G | p.L509R | 11 | 4 | Early 2nd | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thin | LCD atypical; EBMD | Irregularly shaped maps, faint gray–white patches 1 to several millimeters in size, map-dot-fingerprint changes; bilateral subepithelial geographic map-like opacities, lattice lines; geographic opacities at Bowman layer level, lattice lines in deeper stroma | France | 16652336, 21617751 | |

| c.1553T>C | p.L518P | 12 | 4 | Early 2nd | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thin | LCDI; LCDI Atypical | Dense superficial opacity, fine lattice lines in superficial stroma and midstroma, age 17 years fine lattice lines in superficial stroma and midstroma; age 15 round subepithelial central opacities, later extend into peripheral and deep stroma | Japan | 10482106, 10837380, 11095060, 12138697, 21948648 | |

| c.1553T>G | p.L518R | 12 | 4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | LCD//IIIA | Advanced subepithelial and stromal amyloid deposits | Switzerland (Swiss, Italian, or French descent) | 11923233 | |

| c.1565T>A | p.I522N | 12 | 4 | Early 2nd | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thin | LCDI | Distinct lattice lines and diffuse opacification in subepithelial and anterior stroma, thick lattice lines, and diffuse grayish-white clouding that partly hides central lattice lines | China; Mexico | 19956413 | |

| c.1580T>G | p.L527R | 12 | 4 | Late 7th | No | Mainly deep | Thick in some eyes | LCDIII; LCDIV; LCD deep | Asymmetric; large nodular gray–white deposits from deep stroma to pre-Descemet in pupillary zone or large filiform and lattice line opacities in various parts of stroma; deep stromal nodular deposits and thick lattice lines; distinct lattice lines; lattice-shaped granular deposits in asymmetric patterns, nodulolinear deposits mainly in anterior stroma, less linear and macular opacities; bifurcating thick lattice lines in superficial stroma in midperiphery, extending to central stroma, no nodular deposits; discrete and nodular opacities in deep central stroma, no visible lattice lines; haze composed of isolated or fused refractile opacities, most dot-like, some lattice-like; several bifurcating thick lattice lines in superficial to midstroma; discrete nodular opacities in deep stroma | Japan; South Korea | 9799082, 10832717, 11024425, 11095060, 11501939, 11413411, 12138697, 15022435, 15770959, 15923518, 16453189, 17846354, 20357204, 21191728, 21835759, 22876129, 24505203, 26748743 | 21948648 |

| c.1612A>C | p.T538P | 12 | 4 | Early 1st | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thin | LCDI | Lattice lines in central stroma; numerous fine lattice lines and dots in anterior central stroma | Australia; China | 16809844, 21462384, 35985662 | 22605926 |

| c.1613C>G | p.T538R | 12 | 4 | Early 1st | Yes | Mainly anterior | N/A | LCDI/IIIA | LCDI-like | Switzerland (American descent); Ukraine | 11923233, 19062536 | |

| c.1616T>A | p.V539D | 12 | 4 | Late 6th | N/A | Mainly anterior | N/A | N/A | Lattice lines in anterior stroma; anterior and midstromal lattice lines | India | 15623763 | |

| c.1617T>A | p.F540S | 12 | 4 | Late 5th | No | Mainly deep | Thick | N/A | Thick ropy lattice lines | Germany; China | 15790870 | 25557343 |

| c.1625C>G | p.P542R | 12 | 4 | Late 5th | Yes | Anterior to deep | Thick | LCD atypical | Distinct lattice lines; relatively thick lattice lines from the limbus in superficial and deep stromal layers, stromal haze in 1 eye | South Korea | 22876129, 26748743 | |

| c.1631A>G | p.N544S | 12 | 4 | Late 7th | No | Mainly deep | Thin | LCDIV atypical | Distinct lattice lines; dots and lattice lines in midstroma to deep stroma; tiny nodular deposits and thin lattice lines in midstroma | Japan; South Korea | 11024425, 15559315, 15770959, 26748743 | |

| c.1636G>A | p.A546T | 12 | 4 | Intermediate 4th | Yes | Anterior to deep | Thick | LCDIIIA French | Age 55 years predominantly central thick ropy lattice lines, some small nodular opacities, diffuse haze between the lines, age 35 years superficial lattice lines | Brazil; China; France | 10682981, 11297504, 11927442, 16440005, 21462384 | 25910219, 34097874 |

| c.1637C>A | p.A546D | 12 | 4 | Intermediate 3rd | No | Deep to anterior | Minor to thin | LCDIIIA; PCA; GCD1/2 | Multiple polymorphic, polygonal, refractile chipped ice-like gray and white opacities, occasional deep filamentous lines without distinct lattice pattern but producing a small focal network; polymorphic chipped ice-like opacities in posterior stroma, occasional filamentous lines without distinct lattice pattern; polymorphic stromal opacities, distinct branching filamentous lattice opacities, small granular opacities in peripheral cornea; atypical GCD1-like; five predominantly GCD2-like phenotype, one GCD1-like, one LCD-like phenotype; typical IIIA phenotype with focal central and distinct relatively thick lattice lines; polymorphic opacities predominantly in central cornea; short lineal deposits, without a clear lattice pattern; polymorphic opacities in central stroma, conspicuous interdigitating branching filamentous opacities and multiple lattice lines in peripheral stroma, also small granular opacities in peripheral cornea | China; Germany; Mexico; Taiwan; the United States | 15177960, 17063427, 17893671, 19001012, 19303004, 21462384, 22355247, 28393022, 35470743, 35484844 | 23592924 |

| c.1640T>C | p.F547S | 12 | 4 | Intermediate 4th | N/A | Deep to anterior | Minor | PCA | Snowflake-like central deposits, fine linear and chipped-ice deposits, more abundant in central cornea, extending throughout stroma, numerous pre-Descemet deposits | Hungary | 17982422 | |

| c.1643G>C | p.R548P | 12 | 4 | Late 7th | N/A | Deep to anterior | Minor | LCD variant; RBCD | Diffuse central corneal haze with edema without visible lattice lines | South Korea | 26748743 | |

| c.1649T>C | p.L550P | 12 | 4 | N/A | N/A | Deep to anterior | Thin | GCD2 | Deposits typical of GCD2 with bilateral symmetrical discrete lattice lines in peripheral cornea; fine peripheral lattice lines with powdery central lesions, another patient with lattice and granular stromal deposits | Mexico; South Korea | 19303004, 33513810 | |

| c.1673T>C | p.L558P | 12 | 4 | Intermediate 3rd | N/A | Deep to anterior | Thin | LCDIV; PCA | Initially scarce central punctiform 50–100 μm stromal deposits, later confluent, white–gray under direct illumination, typical branched filamentous opacities 0.5–3.0 μm length with no haze in some patients, in 1 patient with granular opacities arranged in irregular round shape in lower cornea; polymorphic corneal amyloidosis with deep stromal opacities | Spain; Ukraine | 19062536, 31056827 | |

| c.1673T>G | p.L558R | 12 | 4 | Late 6th | No | Deep to anterior | Minor | LCD | Fine translucent gray–white branching stromal lattice lines and dots at all depths | Czech Republic | 27028151 | |

| c.1694T>A | p.L565H | 13 | 4 | Late 5th | N/A | N/A | Minor to thin | LCDIIIA; LCD atypical | Haze and diffuse opacities in central stroma, lack of typical lattice lines, oval-shaped or short comma-shaped spots with indistinct margins within deep stroma; diffused opacities in central stroma, fine lattice lines in paracentral and peripheral stroma; small diffused translucent punctate opacities and a few chipped ice-like lattice lines; uniformly diffused punctate opacities in central stroma, fine lattice lines mostly in paracentral stroma | China | 31555324, 35484844 | |

| c.1694T>C | p.L565P | 13 | 4 | Late 6th | Yes | Deep to anterior | Minor | LCD atypical | Round, oval, and short comma-shaped opacities with indistinct margins, no visible lattice lines | Poland | 24473223 | |

| c.1706T>A | p.L569Q | 13 | 4 | Late 6th | Yes | N/A | Thick | LCDI | Large lattice lines; typical lattice lines | South Korea | 25932442, 26748743 | |

| c.1706T>G | p.L569R | 13 | 4 | Early 1st | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thin | LCDI | Diffuse subepithelial and anterior stromal clouding, typical fine branching lattice lines in midperipheral anterior stroma; age 7 years numerous fine refractile lattice lines and dots in central cornea; typical fine branching lattice lines, area of central opacification | The United States (Swiss, Italian, and Irish descent) | 14597039 | |

| c.1715A>G | p.H572R | 13 | 4 | Intermediate 3rd | Yes | Anterior to deep | Thin to thick | LCDI | Asymmetric; elevated subepithelial opacities, diffuse haze, thin to thick lattice lines, diffuse haze; elevated subepithelial opacities, thick lattice lines, diffuse haze; subepithelial and stromal white dots, thin linear irregular branching refractile lines; mild cases resemble LCDI with refractile lattice lines from central stroma to periphery with limbal sparing, in advanced cases lattice lines usually obscured by diffuse stromal opacity, difficult to distinguish from leukoma, corneal surface eventually becomes irregular because of elevated thick lattice lines; lattice lines thicker and less crowded than in LCDI, in anterior stroma yellowish discoloration | Thailand; Chile; China | 17013691, 20161820, 20806046, 31270466, 33513810 | 32637173 |

| c.1772C>T | p.S591F | 13 | 4 | Intermediate 4th | Yes | Deep to anterior | Thick | LCD asymmetric | Asymmetric; translucent subepithelial irregularity, relatively short and thick, branching central lattice lines, extending midperipherally; discrete relatively short and thin branching lattice lines in anterior and midstroma in central stroma | Finland; the United States (Spanish descent) | 33645289, 35315300 | |

| c.1781G>T | p.G594V | 13 | 4 | Late 6th | N/A | Deep | Thick | LCD atypical | Thick lattice lines in deep stroma, extending to limbus | India | 15623763 | |

| c.1828T>G | p.V613G | 14 | 4 | Late 9th | N/A | N/A | N/A | LCD | Corneal opacities, child with small dots and a star-shaped opacity | Algeria | 21617751 | |

| c.1856T>A | p.M619K | 14 | 4 | Late 5th | No | Anterior to deep | Thick | GLCD | In younger individuals, central subepithelial needle-like deposits; in older individuals, polymorphic semiconfluent anterior stromal opacities, combined granular lattice; axially distributed linear branching anterior and midstromal deposits, gray–white on direct illumination and translucent on retroillumination, additionally discrete semiconfluent anterior and midstromal polymorphic deposits; peripheral cornea with linear branching opacities similar to LCDI; dense confluent gray–white anterior and midstromal deposits in central stroma, a few linear extensions of central opacity | The United States (Hispanic) | 18332318 | 28381645 |

| c.1858G>C | p.A620P | 14 | 4 | Intermediate 4th | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thin | LCDIIIA granular | Distinct lattice lines; diffuse superficial haze and extensive lattice lines; focal superficial opacity, thick lattice lines | China; South Korea | 25321938 | |

| c.1859C>A | p.A620D | 14 | 4 | Intermediate 3rd | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thin | LCD variant | Subepithelial and anterior stromal scarring, radially oriented linear opacities in central anterior to midstroma | China; South Korea | 21835759, 26949635, 26748743, 33513810 | |

| c.1861A>C | p.T621P | 14 | 4 | Late 5th | Yes | Mainly anterior | Thick | LCDIIIA | Asymmetric; thick branching ropy lattice lines; thick ropy lattice lines extending to limbus with intervening opacities in central stroma | South Korea | 25932442, 27163623, 35484844 | |

| c.1864A>C | p.N622H | 14 | 4 | Late 5th | No | Anterior to deep | Thick | LCDIIIA; LCD late | Asymmetric; thick central ropy lattice lines | Australia; the United Kingdom | 10328397, 35985662 | 28381645 |

| c.1866T>G/A | p.N622K | 14 | 4 | Intermediate 4th | Yes | N/A | Thick | LCDIIIA | Large, ropy lattice lines in anterior stroma | Switzerland (Italian, South American descent) | 11923233 | |

| c.1867G>C | p.G623R | 14 | 4 | Intermediate 3rd | Yes | Mainly anterior | Minor to thin | LCD | In a young patient, single subtle greyish lattice line; in an older patient, subepithelial map-like opacities in central and midperipheral stroma, 2 branching lattice lines in anterior stroma, delicate thin anterior to midstromal lines in midperipheral cornea | Germany | 19001012 | 28381645 |

| c.1868G>A | p.G623D | 14 | 4 | Intermediate 3rd | Yes | Anterior | Minor to thin | LCDI/IIIA; RBCD; TBCD; EBMD | Tiny discrete linear subepithelial deposits in anterior stroma, middle, and posterior stroma free; patchy subepithelial central stromal haze, a single refractile lattice-like line; several foci of subepithelial haze, a single branching refractile anterior stromal lattice line-like deposit in 1 eye; scattered central patches of subepithelial haze without lattice lines, delicate thin anterior and midstromal lattice lines most dense axially and absent from peripheral 2 mm, a horseshoe-shaped opacification at Bowman layer level in 1 eye; central subepithelial haze, a prominent central subepithelial opacity, very fine branching lattice lines in central anterior stroma, other eye with scattered gray–white subepithelial opacities forming an arrowhead pattern, no lattice lines; subepithelial deposits resembling RBCD; diffuse or geographic superficial stromal opacity, small refractile granules or lines, diffuse axial anterior stromal haze with small lattice lines; geographic pattern of subepithelial haze and tiny granular structures; diffuse subepithelial haze and small refractile structures; subepithelial nodular opacification in a geographic pattern | Switzerland (Swiss, Italian, or French descent); the United Kingdom; the United States | 11923233, 15885785 | |

| c.1870G>A | p.V624M | 14 | 4 | Late 5th | No | Deep to anterior | Thick | LCD | Asymmetric; thick ropy linear opacities in deep stroma, fellow eye with small deep short rod-shaped stromal opacities | The United States | 18385782 | 22155582, 25557343 |

| c.1874T>A | p.V625D | 14 | 4 | Early 2nd | Yes | Anterior | Thin | LCD | Ridgy round pattern of opacities with uneven surface and thin lattice lines; diffuse anterior stromal haze, small granular focal opacities, lattice lines not visible | China | 17765440, 27737463 | |

| c.1877A>C | p.H626P | 14 | 4 | Early 1st | Yes | Anterior | N/A | LCDI/IIIA; early-onset superficial keratopathy | Dense haze, lattice lines; confluent subepithelial opacities; irregular corneal surface, discrete subepithelial gray–white polymorphic opacities project from Bowman layer level into epithelium, with longer duration increasing scarring, neovascularization and calcification with no visible lattice lines | Switzerland (Swiss, Italian, or French descent); Czech; New Zealand | 11923233, 18259096, 18728790 | |

| c.1877A>G | p.H626R | 14 | 4 | Intermediate 3rd | Some | Anterior to deep | Thick | LCDI/IIIA LCDIIIA LCDIIIB; LCDi; LCD asymmetric | Asymmetric; broad lattice lines; broad lattice lines, dense central scarring, initially lower cornea, initially thin lines in fellow eye; subepithelial clumps of translucent material; initial asymmetric stellate deposits in the lower central cornea; thick lattice lines in the whole stromal layer; a band-shaped deposition of amyloid close to Descemet membrane; initially subepithelial stellate deposits in lower central cornea; lattice lines and central patchy deposits; fewer but thicker and deeper lattice lines, extending more to the periphery than those of LCD1; anterior-to-midstromal lattice lines; fine GCD1-like opacities mainly in the central cornea; lattice lines in family, PCA in a sporadic patient; bilateral symmetrical fine translucent lattice lines in the superficial and middle stromal layers; thick lattice lines in peripheral and central cornea with small contralateral stellate or snowflake-like deposits; lattice lines and recurrent diffuse stromal haze; thick lattice lines in deep stroma; thick lattice lines extending toward periphery; delicate fragile rare lattice lines located centrally; thick, distinct lattice lines extending from limbus to limbus accompanied by stromal haze; radially oriented curvilinear opacities; gray–white thick lattice lines extending across the cornea; asymmetric, branching, translucent lattice lines, focally with stromal haze, a single patch peripherally in fellow eye; coarse, branching, lattice lines, with prominent stromal haze, a single patch peripherally in fellow eye; translucent focally delicate and branching, focally coarse deposits associated with stromal haze; GCD2 phenotype; numerous translucent, thick lattice lines in superficial and midstroma in central and peripheral cornea; minor lattice lines predominantly below the visual axis; lattice lines predominantly below the visual axis; gray–white thick lattice lines in deep stroma; thick, ropy lattice lines extending to periphery, superficial scar from recurrent erosions | Canada; China; Finland; France; India; Mexico; Switzerland; Ukraine; Vietnam; the United Kingdom; the United States | 10328397, 10798644, 11146721, 11297504, 11923233, 11927442, 12072720, 12770961, 15623763, 16008913, 16888689, 18728790, 19001012, 19350511, 19303004, 20664689, 21921985, 21835759, 24579556, 24589966, 24801599, 25876897, 26949635, 27348782, 27737463, 28358433, 30851800, 33513810 | 28381645, 28689406, 30387319 |

| c.1892T>A | p.V631D | 14 | 4 | N/A | N/A | Deep to anterior | N/A | LCD deep | Initially stellate pre-Descemet deposits with round Descemet indentations, later radial lattice lines in midstroma, anterior third of stroma mostly intact; opacities typically in central stroma | Switzerland (Italian descent) | 11923233, 23455751 |

EBMD, epithelial basement membrane dystrophy; GCD, granular corneal dystrophy; GLCD, granular-lattice corneal dystrophy; LCD, lattice corneal dystrophy; LCDI, previously called lattice corneal dystrophy, type 1 and now renamed classic lattice corneal dystrophy; LCDi, lattice corneal dystrophy intermediate; PCA, polymorphic corneal amyloidosis; RBCD, Reis-Bücklers corneal dystrophy; TBCD, Thiel-Behnke corneal dystrophy.

Lattice Variant Nomenclature

We propose a nomenclature system for this expanding category of LCD variants. For the first time, actual names of dystrophies will be primarily assigned based on genotype rather than phenotype. Consequently, for both consistency of reporting and to facilitate literature searches, we recommend referring to the specific pathogenic variant, when known, by appending the protein change using 1-letter amino acid abbreviations. For example, the LCD variant named LCD-H626R results from the His626Arg missense mutation. Identification of the variant by genetic mutation may be helpful in the future, should gene-targeted therapies be developed.

The Wide Variety of Lattice Variant Phenotypes

While lattice lines are typically evident within the many variants, the spectrum of their phenotypes may vary wildly with some variants having remote or no clear resemblance to classic LCD. The age of onset and the depth of the deposits differ between variants, and some variants include opacities that have been described as polymorphic, polygonal, refractile chipped ice-like, gray to white, snowflake or geographic, rather than linear.15 These LCD variants may initially be misdiagnosed as other corneal dystrophies like epithelial basement membrane dystrophy (EBMD), RBCD, TBCD, or GCD1 (Table 2) until genotyping reveals the true diagnosis.

There are at least 5 recurring major phenotypes which are distinguished by the onset of clinical signs in addition to the shape and depth of the opacities. There is often histopathologic confirmation regarding the depth and distribution of amyloid deposits. Similar to classic LCD, phenotypic variation can be found between both eyes and among individual patients with the same mutation. Some advanced cases may have severe anterior stromal scarring that obscures other phenotypic features. In these instances we do not know the earlier phenotype, when these patients were younger, that preceded the severe corneal scarring.

The 5 major phenotypes of LCD variants include (Table 2) the following:

Early-onset LCD variants.

Similar features and age of onset to classic LCD

(eg, LCD-V505D, LCD-L518P, LCD-T538P, and LCD-P569R).

2. Typically intermediate and sometimes late-onset LCD variants.

Thicker, often ropy, more prominent lattice lines than classic LCD.

(eg, LCD-P501T, LCD-A546T, LCD-S519F, LCD-T621P, and LCD-H626R which is the second most common and widespread LCD).19

3. Late-onset LCD variants.

Lattice lines can range from inconspicuous/infrequent to distinct. Amyloid deposits mostly in deep stroma close to Descemet membrane.

(eg, LCD-R496W, LCD-G594V, and LCD-V631D).

4. Early or intermediate-onset LCD variants with superficial geographic opacification from Bowman layer deposits.

Infrequent and/or indistinct lattice lines. Easily misdiagnosed as RBCD or TBCD or even EBMD.

(eg, LCD-L509R, LCD-G623D, and LCD-H626P).

5. Intermediate, sometimes late-onset LCD variants with polymorphic deposits.

Distinct or inconspicuous/infrequent lattice lines which may resemble chipped ice. The deposits vary in form and depth and are mostly dot-shaped and comma-shaped. Later in the disease course, with further dystrophy progression, some corneas demonstrate more prominent central opacification

(eg, LCD-L527R, LCD-A546D, LCD-A547S, LCD-L558P, and LCD-L565P).

PRE-DESCEMET CORNEAL DYSTROPHY (PDCD)

In the second edition of the IC3D, we reported that isolated pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy (PDCD) was not well defined because it was neither clearly hereditary nor degenerative. In the IC3D third edition, we have expanded the PDCD template to a template entitled PDCDs, which also includes the degeneration, cornea farinata, as well as punctiform and polychromatic pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy (PPPCD). In 2020, PPPCD was mapped to the PRDX3 gene on chromosome 10.20 The pre-Descemet opacities in PPPCD are polychromatic, larger, and more punctate than those in the degeneration, cornea farinata. We have chosen to include PPPCD within the PDCDs template so that clinicians can easily compare the findings of PPPCD, with which they may be unfamiliar, with the more common degenerative condition of cornea farinata. The goal is that the clinician presented with this additional knowledge has an opportunity to revise their diagnosis accordingly. In addition, a single patient with PPPCD was found to also have polychromatic crystals beneath their lens capsule, introducing the question of whether PPPCD is actually a corneal dystrophy or a manifestation of a systemic disease.20

SHOULD GENETIC TESTING BE PERFORMED WHEN SUSPECTING A CORNEAL DYSTROPHY?

How can an ophthalmologist confirm that their phenotypic diagnosis is correct when genotypic information is not available? If the dystrophy requires surgical intervention to improve vision, excision of corneal tissue may be submitted for pathology to further substantiate the clinical diagnosis. However, most patients with corneal dystrophies do not need surgical intervention. It has also been found that if the pathologist is unsure of what they seek, they may erroneously confirm an ophthalmologist's postulated though erroneous diagnosis.3

How critical is the accuracy of a specific corneal dystrophy diagnosis? Patients are interested in their prognosis, and different dystrophies have distinct clinical courses. Among the TGFBI corneal dystrophies which are typically distinguished on corneal examination and history, GCD1 usually results in more frequent corneal erosions and earlier visual loss than granular corneal dystrophy type 2 (GCD2). GCD2 will progress more rapidly after corneal injury, including surgery, while this does not occur with classic LCD. This type of information is of importance to an affected patient. While the clinical examination will often be sufficient to provide a specific corneal dystrophy diagnosis, this also depends on the experience and expertise of the examiner. Genetic testing is an easy way to confirm or refute the phenotypic diagnosis. The LCD variants are an excellent example in which a dystrophy may have a phenotype similar to classic LCD but a different mutation. In addition, some LCD variants do not resemble any widely recognized corneal dystrophy, and thus, genotyping may be necessary to even establish a corneal dystrophy diagnosis. Genotyping is infrequently performed because of inconvenience and cost. If genetic testing were performed more frequently, we might discover that our phenotypic diagnoses are less accurate than we imagine. Genotyping might also reveal more genetic variants with distinct mutations, as has occurred with the LCD variants, a category that continues to grow. In addition, genotyping may prove important if gene-targeted therapy is developed.

THE SPORADIC CORNEAL DYSTROPHY

When should the diagnosis of a sporadic corneal dystrophy be considered? When the diagnosis of a typically autosomal dominant corneal dystrophy is considered in an individual with a negative family history, the clinician should try to examine both parents and possibly other family members to determine whether some other family members could manifest the dystrophy but remain asymptomatic. In addition, other conditions such as paraproteinemic keratopathy (PPK) associated with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), smoldering plasma cell myeloma or Waldenström macroglobulinemia should be excluded.21 PPK can mimic various corneal dystrophies including SCD, LCDs, or GCD1. The index of suspicion for PPK can increase if there is late and possibly unilateral onset with a negative family history. Serum protein immunoelectrophoresis can reveal the presence of a monoclonal gammopathy.22

If after careful history and examination, the clinical phenotype still suggests a sporadic corneal dystrophy, for example, GCD1 or RBCD, the possibility of a de novo mutation must be considered. This term describes a change in the DNA sequence of a gene (for GCD1 and RBCD, this would be TGFBI) that is seen for the first time in a person and has not appeared in previous generations. A de novo mutation explains how a patient can have a corneal dystrophy that did not occur in his or her parents or siblings. Therefore, to make the molecular diagnosis of a de novo autosomal dominant mutation, testing of both parents must be negative for the mutation detected in the index patient. True sporadic or de novo cases can only be confirmed by molecular testing of the affected patient, the parents, and if necessary, their siblings.

It is important to recognize that in the same pedigree, different affected individuals can show variable phenotypes from mild to severe because of variable expressivity. It is also possible that a molecularly affected individual may not show any signs of the disease because of reduced penetrance of the gene mutation. This is why when making the argument for a de novo mutation in an autosomal dominant corneal dystrophy, it is mandatory that molecular genetic testing, not simply clinical examination, be performed for the proband and also clinically unaffected parents and siblings.

THE FOUNDER EFFECT

The founder effect is the introduction of a new mutation that becomes more frequent over generations resulting in the loss of genetic variation in this subset of the larger population. The most common scenario is offspring of an individual who first developed a de novo genetic mutation and for geographical reasons (eg, living in a remote area or on an island), the genetic diversity is reduced. Over time, there is likely to be a higher rate of this gene mutation compared with an ethnically and racially similar population. As migration occurs and affected individuals move away from the original area or population, by comparing haplotypes between affected individuals, a founder effect can still be detected. A founder effect need not only be seen in autosomal dominant conditions.23–25

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT

The management of corneal dystrophies is essentially functional to improve visual acuity and/or symptomatic to relieve ocular discomfort or pain.

Abnormalities in the ocular surface result from corneal dystrophies affecting the epithelium and/or anterior stroma. Corneal surface irregularity may be associated with foreign body sensation or painful corneal erosive episodes resulting from poor epithelial adhesion. If corneal epithelial irregularity involves the visual axis, then irregular astigmatism reduces quality and/or visual acuity. Such corneal epithelial abnormalities can be managed conservatively with lubricants, hyperosmotic agents, patching, bandage contact lenses, or, when recalcitrant, minor surgical interventions such as manual epithelial debridement, superficial keratectomy (SK) of subepithelial debris and deposits, anterior stromal puncture, superficial diamond burr polishing, or excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK).

Deposition of opaque substances in epithelial, subepithelial, epithelial-stromal TGFBI or stromal corneal dystrophies may also result in vision reduction. Visual loss may also occur in endothelial corneal dystrophies because of corneal epithelial or stromal edema consequent to endothelial dysfunction. Stromal scarring can also result from multiple epithelial erosions and chronic stromal edema.

The ophthalmologist and patient must decide if and when intervention is required to improve comfort and vision, understanding that dystrophies can recur although the frequency of recurrence depends on the specific corneal dystrophy. For the more superficial epithelial basement membrane dystrophies or degenerations, such as EBMD, SK alone is remarkably effective in improving acuity and decreasing erosions, and these benefits are often sustained for years, if not indefinitely, without recurrence. For opacities involving only the subepithelial and/or superficial stromal layers, SK and PTK are currently preferred for their technical ease, although both can be associated with high rates of recurrence within a few years. Mitomycin C (MMC) application has been used in conjunction with PTK for some corneal dystrophies in an attempt to decrease the risk of recurrence without definitive evidence for efficacy. MMC does seem to reduce postoperative scarring/haze when deeper stromal ablations are required to remove the bulk of the corneal opacity.

For more diffuse and deep stromal deposits, stromal replacement surgery such as deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) or penetrating keratoplasty (PK) can be performed with DALK having an advantage of retaining unaffected endothelium, thereby eliminating endothelial immune rejection risk. PK may be reserved for failed DALK attempts. Mushroom-shaped PK can be alternatively used to allow maximal removal of the diseased stroma with minimal endothelial replacement. Compared with PTK and SK, latency of recurrence is longer for DALK and may be even longer for PK. In epithelial-stromal TGFBI dystrophies, recurrent deposits have been observed within the epithelium, superficial stroma, graft–host interface, or along suture tracks (refer to GCD1 template).

For dystrophies solely associated with endothelial dysfunction, endothelial keratoplasty, either by Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) or Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), has become favored in comparison with PK because the former offers more rapid visual recovery, improved visual outcome, reduced immune rejection rates and lower risk of traumatic surgical wound dehiscence.

It is important to realize that not all corneal dystrophy patients require treatment. The ophthalmologist may be surprised by a patient's excellent visual acuity despite significant corneal opacification. Patients with SCD in their twenties, especially those without corneal crystals, often have no complaints. Early FECD with only corneal guttae and only mild stromal edema can retain excellent visual acuity and may be potentially benefited without surgical intervention, from regenerative medical therapies such as topical rho kinase inhibitors.26,27 The progression of corneal dystrophies is often variable such that the diagnosis of a particular corneal issue does not necessarily predict its course or therapy requirement. Consequently, the ophthalmologist must understand both the patient's symptoms and their severity before determining whether and what interventions should be considered. The exact etiology of a patient's complaint must be verified by a complete eye examination. If bothersome ocular irritation, recurrent erosion, and/or decreased vision are present, it is imperative to ascertain whether such complaints are consequent to stromal opacity and/or irregular surface astigmatism, as well as to assess the potential contributions of other ocular disorders such as amblyopia, cataract, glaucoma, or retinal issues. The choice of treatment becomes critically dependent on such exact etiologic diagnosis of the patient's complaint.

Table 3 outlines the management strategies for various corneal dystrophies.28–51 Several corneal dystrophies including FCD, PACD, CCDF, and PDCD are typically asymptomatic and do not require treatment. The table provides a broad overview of general treatment approaches rather than an exhaustive description of all possible treatments. More detailed sources should be consulted when contemplating treatment for a specific corneal dystrophy.

TABLE 3.

Management of Corneal Dystrophies

| Corneal Dystrophies | Management |

| Epithelial and subepithelial dystrophies | |

| Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy (EBMD) | Asymptomatic patients do not require treatment. For recurrent erosions, treatment may include lubricant drops, gels, or hyperosmotic agents during the day and/or ointments at bedtime. Patching or bandage contact lenses may also be necessary for acute attacks.28 Oral tetracyclines with topical steroids may be considered for recalcitrant erosions.29,30 SK to remove devitalized epithelium plus subepithelial pannus or deposits can improve epithelial–stromal adhesion and reduce irregular astigmatism. For persistent erosions outside the visual axis, anterior stromal micropuncture is recommended.31 When severe erosions are in the visual axis, mechanical debridement of loosened epithelium with or without diamond burr-assisted polishing is preferable to micropuncture.32 Excimer laser PTK is an alternative treatment, particularly if irregular astigmatism involves the visual axis or if there is underlying anterior corneal haze/scarring.33 Consider avoiding LASIK in EBMD because of the increased risk of epithelial sloughing and epithelial ingrowth.34 |

| Epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophies (EREDs) | For recurrent erosions, refer to section on EBMD management. For anterior stromal opacification, refer to section on RBCD/TBCD. |

| Subepithelial mucinous corneal dystrophy (SMCD) | For recurrent erosions, refer to section on EBMD management. For anterior stromal opacification, refer to section on RBCD/TBCD. |

| Meesmann corneal dystrophy (MECD) | Ocular discomfort due to epithelial microcysts and erosions can be managed with lubricants and occasionally bandage contact lenses. Epithelial debridement is rarely required.35 |

| Lisch epithelial corneal dystrophy (LECD) | Refer to section on EBMD management. Surgical intervention is rarely required.36 |

| Gelatinous drop-like corneal dystrophy (GDLD) | Lubricant eye drops and bandage contact lens provide symptomatic relief. Surgical interventions including superficial keratectomy, anterior lamellar keratoplasty (ALK), penetrating keratoplasty (PK), and as a final option, keratoprosthesis.37 |

| Epithelial–stromal TGFBI dystrophies | |

| Reis–Bücklers corneal dystrophy (RBCD) | For recurrent erosions, refer to section on EBMD management.37 For visually significant opacities, SK, PTK, and superficial anterior lamellar keratoplasty (SALK) may be performed.38,39 Recurrence in the graft is common and may necessitate repeat interventions or possibly DALK.40 |

| Thiel–Behnke corneal dystrophy (TBCD) | Refer to section on RBCD management.41 Recurrence in the graft is common. |

| Lattice corneal dystrophies (LCDs) | For recurrent erosions, refer to section on EBMD management. For visually significant opacities, PTK, SALK, ALK (microkeratome-assisted), DALK, PK may be performed depending on the depth of stromal involvement.42–44 DALK is advantageous in sparing the unaffected corneal endothelium. Failed DALK attempt may require conversion to PK. Beware of the risk of neurotrophic keratopathy in Meretoja syndrome.45 Recurrence in the graft is common and may occur at variable intervals and patterns.42 |

| Granular corneal dystrophy, type 1 (GCD1) and Granular corneal dystrophy, type 2 (GCD2) | For recurrent erosions, refer to section on EBMD management. For visually significant opacities, refer to the section on LCDs management. Recurrence in the graft is both more common and occurs earlier than in classic LCD (Figs. 12F, G).42,46 In GCD2, injury to the cornea such as LASIK results in accelerated deposition of corneal opacities and is contraindicated (Fig. 13H).47 |

| Stromal dystrophies | |

| Macular corneal dystrophy (MCD) | For recurrent erosions, refer to section on EBMD management. For visually significant opacities, refer to the section on LCDs management. Macular dystrophy does involve the corneal endothelium unlike LCD, so PK may be a better option than DALK. Recurrence after corneal grafting is less common compared with GCD1 and classic LCD.48 |

| Schnyder corneal dystrophy (SCD) | PTK can be performed if crystals in the visual axis are symptomatic. Visual acuity may be limited by underlying panstromal lipid deposits, thereby requiring DALK or PK. Some patients with decreased vision from cataracts require DALK or PK to facilitate visualization if severe corneal opacification is present. |

| Congenital stromal corneal dystrophy (CSCD) | For visually significant opacities, refer to section on LCDs management. |

| Endothelial dystrophies | |

| Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) | Asymptomatic patients should be observed. For minimal corneal decompensation, hypertonic saline drops and bandage contact lens may provide temporary symptomatic relief.49 Endothelial keratoplasty including DSAEK and DMEK is the standard definitive treatment. Advanced cases with severe end-stage corneal edema and deep stromal scarring may require PK.50 Alternative approaches such as Descemet stripping only (DSO), use of topical rho kinase inhibitors and intracameral injections of donor endothelial cells are under investigation. |

| Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) | Refer to section on FECD management. Intraocular pressure should be monitored, and if glaucoma is present, then managed. Amblyopia therapy is required in young children with high or asymmetric refractive error. |

| Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED) | Refer to section on PPCD management. |

| X-linked endothelial corneal dystrophy (XECD) | Refer to section on FECD management. Amblyopia therapy required in young children with high or asymmetric refractive error.51 |

THE IC3D FUTURE

The first and second editions of the IC3D were directed toward the clinician and the pathologist to facilitate diagnosis of the patient with corneal dystrophy, and this third edition continues that goal. The IC3D first, second, and third editions are available at https://corneasociety.org/publications/ic3d. The examining ophthalmologist has ready online access to the dystrophy templates without charge while examining a patient, as a guide for their diagnosis. While the IC3D has continued to publish nomenclature updates every 7 to 8 years, our infrequent journal publications are not an optimal approach to keep pace with the rapid changes in the corneal dystrophy knowledge base. The Cornea Society has secured the website domain www.ic3dcornealdystrophy.org so that going forward, the IC3D will have the potential to make more frequent changes online as the corneal dystrophy knowledge base advances.

EPITHELIAL AND SUBEPITHELIAL DYSTROPHIES

Epithelial Basement Membrane Dystrophy (EBMD)

Mendelian inheritance in man (MIM) #121820.

Former Alternative Names and Eponyms

Anterior basement membrane dystrophy.

Map-dot-fingerprint dystrophy.

Cogan microcystic epithelial dystrophy.

Inheritance

Most cases have no inheritance documented. Consequently, EBMD is usually considered to be degenerative or secondary to trauma.

Genetic Locus

None.

Gene

None (see note below).

Onset

Commonly presents in adult life. Rarely described in children.

Signs

Maps

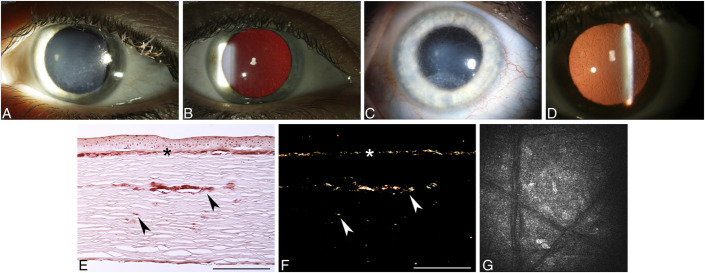

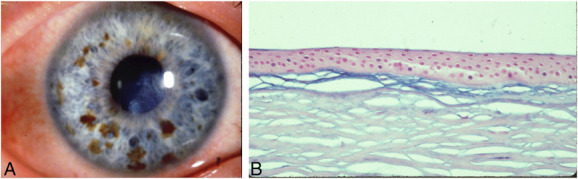

Irregular islands of thickened, gray, hazy epithelium with scalloped, circumscribed borders, particularly affecting the central or paracentral cornea. Isolated or combined with other signs (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy (EBMD). A, Map-like changes. B, Intraepithelial dot opacities (Cogan cysts) underlying map-like figures. C, Fingerprint lines, best visualized with retroillumination. D, Multiple crowded blebs (Bron), only visible in retroillumination. E and F, Light microscopy shows excessive basement membrane material (arrowheads) between the distorted epithelium and the intact Bowman layer to form sheets corresponding to maps (E) and redundant folds corresponding to fingerprint lines (F) (E, Masson trichrome; F, Periodic acid–Schiff, bar = 200 μm). G, In vivo confocal microscopy demonstrates abnormal hyperreflective intraepithelial basement membrane material within suprabasal and basal epithelial cell layers (400 × 400 μm). H, Spectral domain OCT scan shows presence of hyperreflective dots (intraepithelial pseudocysts) within the epithelial layer. Figures 1A, B, C, D, E, F, and G from Figures 1A, B, C, D, E, F, and G in Weiss JS, Møller HU, Aldave AJ, et al. IC3D Classification of Corneal Dystrophies—Edition 2. Cornea. 2015;34:117–159.

Dots (Cogan)

Irregular round, oval, or comma-shaped nonstaining, putty-gray intraepithelial opacities, clustered like an archipelago in the central or paracentral cornea (Fig. 1B). Typically combined with other signs, especially with maps.

Fingerprint Lines

Parallel, curvilinear lines, usually paracentral, best visualized with retroillumination (Fig. 1C). Isolated or combined with other signs, especially maps.

Bleb Pattern (Bron)

Subepithelial pattern like pebbled glass, best seen by retroillumination (Fig. 1D). Isolated or combined with other signs. Much less common than other signs.

EBMD can be seen in direct illumination but is often highlighted using retroillumination off the retina or iris. The lesions frequently cause the epithelial layer to be slightly elevated; this elevation can often be best appreciated by placing fluorescein dye on the cornea and looking for “negative staining” with the cobalt blue light.

Poor adhesion of basal epithelial cells to abnormal basal laminar material is believed to predispose to recurrent erosions.

Symptoms

EBMD can be asymptomatic, associated with mild to severely painful erosive episodes and/or may cause decreased vision by inducing mild irregular astigmatism (monocular diplopia or triplopia, “ghost” or “shadow” images).

Course

Location and degree of pathology can fluctuate with time.

Light Microscopy

Maps

Sheets of intraepithelial, multilamellar, basal laminar material (Fig. 1E).

Dots

Intraepithelial pseudocysts containing cytoplasmic debris.

Fingerprint Lines

Rib-like intraepithelial extensions of basal laminar material (Fig. 1F).

Bleb Pattern

Irregular, subepithelial accumulation of a fibrillogranular material.

In contrast to some other superficial dystrophies, the Bowman layer is normal.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Maps

Thick, multilamellar sheets (2–6 nm thick) of epithelial basement membrane that extend into the epithelium.

Dots

Intraepithelial pseudocysts contain degenerating cells with pyknotic nuclei and cytoplasmic debris.

Fingerprint Lines

Fine fibrillar (17 nm diameter) and granular (8 nm) substance in addition to undulating waves of the basement membrane.

Bleb Pattern

Discrete noncystic mounds of abnormal granular material deposited between the epithelium and the Bowman layer that indents the overlying basal epithelial cells. May mimic cysts clinically, but no cysts are present on histology.

Confocal Microscopy

Maps

Highly reflective tissue in various configurations corresponds to abnormal basement membrane extending into the intermediate and basal epithelial cell layers. Adjacent basal epithelial cells appear distorted. No abnormalities in superficial epithelial cells or stroma.

Dots

Hyperreflective structures with sharp borders within the intermediate cell layers.

Fingerprint Lines

Linear hyperreflective structures corresponding to abnormal basement membrane projecting into the corneal epithelium (Fig. 1G).

Bleb Pattern

Circular or oval hyporeflective or hyperreflective areas at the level of the basal epithelium and the Bowman layer. Some areas contain hyperreflective spots.

Optical Coherence Tomography

Maps

Presence of an irregular and thickened epithelial basement membrane with duplication and/or insinuation into the corneal epithelium layer.

Dots

Hyperreflective dots (intraepithelial pseudocysts) within the epithelial layer (Fig. 1H).

Fingerprint Lines

Expansions and folds of the pathological basement membrane.

Bleb Pattern

Hyporeflective spaces between the corneal epithelial layer and the Bowman layer.

Category

Category 3. Most likely degenerative and not hereditary.

Note: Only 1 publication exists which reports 2 families with EBMD with TGFBI changes (L509R and R666S), with few family members with positive clinical findings and genetic testing and no histopathology. Although other familial cases of EBMD have been reported in the literature, the evidence of it being a dystrophy is inconclusive because of lack of genotyping and histopathology or presence of changes suggestive of other TGFBI-related corneal dystrophies (L509R has alternatively been reported as a LCD variant with superficial geographic opacification and lattice lines, see Table 2), or the change is not confirmed to the pathogenic (R666S remains a variant of undetermined significance [VUS]).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boutboul S, Black GC, Moore JE, et al. A subset of patients with epithelial basement membrane corneal dystrophy have mutations in TGFBI/BIGH3. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:553–557.

Bron AJ, Brown NA. Some superficial corneal disorders. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1971;91:13–29.

Bron AJ, Tripathi RC. Cystic disorders of the corneal epithelium II. Pathogenesis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1973;57:361–375.

Cogan DG, Donaldson DD, Kuwabara T, et al. Microcystic dystrophy of the corneal epithelium. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1964;62:213–225.

Guerry D. Fingerprint-like lines in the cornea. Am J Ophthalmol. 1950;33:724–726.

Hau SC, Tuft SJ. In vivo confocal microscopy of bleb-like disorder in epithelial basement membrane dystrophy. Cornea. 2011;30:1478–1480.

Labbé A, De Nicola R, Dupas B, et al. Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy: Evaluation with the HRT II Rostock Cornea Module, Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1301–1308.

Laibson PR, Krachmer JH. Familial occurrence of dot (microcystic), map, fingerprint dystrophy of the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1975;14:397–399.

Laibson PR. Microcystic corneal dystrophy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1976;74:488–531.

Lisch W, Lisch C. Die epitheliale Hornhautbasalmembrandystrophie. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1983;183:251–255.

Munier FL, Korvatska E, Djemaï A, et al. Kerato-epithelin mutations in four 5q31-linked corneal dystrophies. Nat Genet. 1997;15:247–251.

Rodrigues MM, Fine BS, Laibson PR, et al. Disorders of the corneal epithelium. A clinicopathologic study of dot, geographic, and fingerprint patterns. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;92:475–482.

Vogt A. Lehrbuch und Atlas der Spaltlampenmikroskopie des lebenden Auges (1. Teil). Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1930:119–121.

Epithelial Recurrent Erosion Dystrophies (EREDs)

MIM #122400.

Former Alternative Names and Eponyms

Franceschetti corneal dystrophy (FRCD).

Dystrophia Smolandiensis (DS).

Dystrophia Helsinglandica (DH).

Note: EREDs includes ERED, FRCD, DS, and DH. Only ERED has a published genetic locus and gene.

Inheritance

Autosomal dominant.

Genetic Locus

10q25.1 (ERED).

Gene

Collagen, type XVII, alpha-1—COL17A1 (ERED).

Onset

Early childhood.

Signs

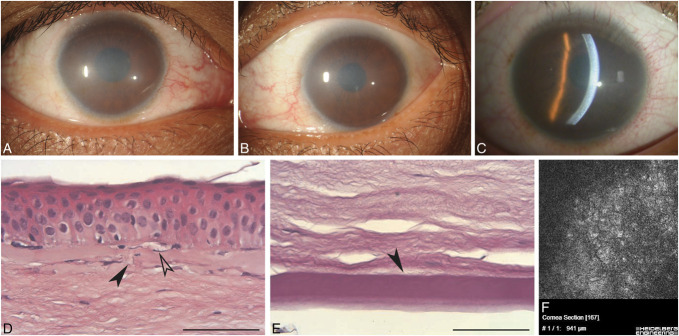

Recurrent epithelial corneal erosions, presenting in the first decade of life, last 1 to 7 days. During pain-free intervals, no biomicroscopically visible corneal changes are initially present (Fig. 2A). By middle age, recurrent attacks may gradually lead to focal or diffuse, central, or paracentral subepithelial opacities (Fig. 2B) or elevated keloid-like scars, resulting from subepithelial fibrosis.

FIGURE 2.

Epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophies (EREDs). A, In the first decades of life, the cornea appears normal without any dystrophy-specific signs after recurrent epithelial erosion. B, Bilateral central and paracentral opacities in the right (i) and left (ii) corneas of a 67-year-old with ERED and COL17A1 mutation. C, Light microscopy of the 67-year-old in (B) with keloid pannus visible between the basal epithelium and the locally destroyed (therefore absent) Bowman layer. PAS, bar = 100 μm. In several places, the epithelium is loosely attached (black arrowhead) to the basement membrane which also demonstrates breaks (white arrowhead) (Gly1052 COL17A1 mutation). D, Light microscopy: In advanced age, the Bowman layer (arrowhead) is partially destroyed and pannus (pan) is found between the basal epithelium and the Bowman layer (PAS, × 200 μm). E, Electron microscopy of pannus with numerous fibroblasts. Figures 2A and D from Figures 2A and C in Weiss JS, Møller HU, Aldave AJ, et al. IC3D Classification of Corneal Dystrophies—Edition 2. Cornea. 2015;34:117–159. Figure 2E from Figure 2 in Lisch W, Bron AJ, Munier FL, et al. Franceschetti hereditary recurrent corneal erosion. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:1073–81.e4.

Symptoms

Painful epithelial erosive attacks commence in the first decade and may recur throughout life. The attacks often start at night. Erosive attacks decrease in frequency and severity by the late thirties and may stop. Visual impairment from central corneal opacification may occur in up to 50% of patients by the late thirties.

Course

ERED, FRCD, DS, and DH all have frequent erosions in childhood with absence of corneal changes during pain-free episodes in childhood. Corneal erosions become less frequent with age. ERED shows individual phenotypic variation in the age of onset, frequency, and severity of erosions. Corneal erosions become less frequent with age. In DS, erosions are reported to begin in the first year, decrease in the late thirties, and then can stop entirely. By the late thirties, visual acuity is markedly decreased with 50% reporting having had penetrating keratoplasty. In DH, erosions are reported to begin at age 4 to 7 years, decreasing in frequency and intensity by the late twenties and developing subepithelial fibrosis by the late thirties although visual acuity is not usually affected. FRCD demonstrates midlife subepithelial fibrosis.

Light Microscopy

ERED

Uneven epithelial thickness with intracellular vacuoles. Discontinuous basement membrane is often separated from basal epithelial cells by collagenous scar tissue, and the Bowman layer is absent (destroyed) (Fig. 2C). These specimens represent late stages of the dystrophy.

FRCD

Irregular basal epithelium with enlarged intercellular spaces. Alcian blue-positive deposits are present both intracellularly and intercellularly. Partial or complete destruction of the Bowman layer with intervening avascular fibrous pannus between the basal epithelium and the Bowman layer (Fig. 2D). Negative Congo red staining.

DS

Keloid-like structure stains positive with Congo red, indicating secondary amyloidosis.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

FRCD

Irregularity in size and shape of the basal epithelial cells and enlarged intercellular clefts corresponding to Alcian blue-positive deposits. Presumably “dystrophic” mitochondria in between basal epithelial cells. Pannus contains numerous fibroblasts (Fig. 2E).

Immunohistochemistry

ERED

Corneal keratocytes in the subepithelial scar can demonstrate immunopositivity for syndecan (CD138), which is typical for activated fibroblasts, and smooth muscle actin, which is typical of myofibroblasts.

FRCD

Segmental reduced expression of the tight junction proteins claudin and E-cadherin, both of which are desmosome components. Decorin expression appears to be enhanced in the basal epithelial layer compared with normal postmortem cornea.

DS

Abundant fibronectin is present in areas of subepithelial fibrosis.

Confocal Microscopy

DS

Abnormal thinning of the corneal epithelium, absence of the Bowman layer with accumulation of abnormal material at the level of the Bowman layer. Subepithelial corneal nerves are sparse and tortuous.

Category

1. ERED

4. FRCD, DS, and DH

Note: Clinical, histopathologic, and electron microscopic descriptions of FRCD, DS, and DH are consistent with ERED, although neither linkage to the 10q25.1 locus nor COL17A1 mutation screening has been published. The difference in severity of corneal opacification in FRCD, DS, and DH could be explained by the presence of polymorphism and differential expressivity of a common gene. Future DNA analysis will reveal more information about FRCD, DS, and DH which could facilitate differential diagnosis. A synonymous mutation in COL17A1 can result in abnormal splicing and cause ERED, and 1 family that carries this variant was initially incorrectly diagnosed as a variant of Thiel–Behnke dystrophy linked to 10q23-q24. It is not clear whether subepithelial mucinous corneal dystrophy (SMCD) actually represents a unique dystrophy or could also fall under the EREDs group. The term “familial recurrent corneal erosions” should not be used to refer to EREDs because the former is a descriptive rather than diagnostic term as recurrent erosions also frequently occur in several other corneal dystrophies.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Franceschetti A. Hereditäre rezidivierende Erosion der Hornhaut. Z Augenheilk. 1928;66:309–316.

Hammar B, Björck E, Lagerstedt K, et al. A new corneal disease with recurrent erosive episodes and autosomal-dominant inheritance. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86:758–763.

Hammar B, Björck E, Lind H, et al. Dystrophia Helsinglandica: a new type of hereditary corneal recurrent erosions with late subepithelial fibrosis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:659–665.

Hammar B, Lagali N, Ek S, et al. Dystrophia Smolandiensis: a novel morphological picture of recurrent corneal erosions. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:394–400.

Jonsson F, Byström B, Davidson AE, et al. Mutations in collagen, type XVII, alpha 1 (COL17A1) cause epithelial recurrent erosion dystrophy (ERED). Hum Mutat. 2015;36:463–473.

Legrand J. Dystrophie épithéliale cornéenne récidivante familiale. Bull Soc Ophtalmol. 1963;5:384–387.