Abstract

Background:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is highly prevalent and poorly managed in spinal cord injury (SCI). Alternative management models are urgently needed to improve access to care. We previously described the unique models of three SCI rehabilitation centers that independently manage uncomplicated OSA.

Objectives:

The primary objective was to adapt and implement a similar rehabilitation-led model of managing OSA in an SCI rehabilitation center in Australia. Secondary objectives were to identify the local barriers to implementation and develop and deliver tailored interventions to address them.

Methods:

A clinical advisory group comprised of rehabilitation clinicians, external respiratory clinicians, and researchers adapted and developed the care model. A theory-informed needs analysis was performed to identify local barriers to implementation. Tailored behavior change interventions were developed to address the barriers and prepare the center for implementation.

Results:

Pathways for ambulatory assessments and treatments were developed, which included referral for specialist respiratory management of complicated cases. Roles were allocated to the team of rehabilitation doctors, physiotherapists, and nurses. The team initially lacked sufficient knowledge, skills, and confidence to deliver the OSA care model. To address this, comprehensive education and training were provided. Diagnostic and treatment equipment were acquired. The OSA care model was implemented in July 2022.

Conclusion:

This is the first time a rehabilitation-led model of managing OSA has been implemented in an SCI rehabilitation center in Australia. We describe a theory-informed method of adapting the model of care, assessing the barriers, and delivering interventions to overcome them. Results of the mixed-methods evaluation will be reported separately.

Keywords: implementation science, sleep apnea syndromes, spinal cord injuries, rehabilitation

Introduction

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is the most common sleep disorder in spinal cord injury (SCI) and a significant source of morbidity. SDB in SCI is associated with substantially lower quality of life, cognitive impairment, and daytime sleepiness.1,2 Over 80% of people with tetraplegia have SDB, with over a third having severe disease.3 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most predominant form of SDB in SCI; it is 9 to 18 times more prevalent than central sleep apnea.4

OSA is traditionally diagnosed with an overnight sleep study and can be effectively treated with therapies such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).5 Despite the high prevalence and negative consequences, available data suggest that OSA is grossly underdiagnosed and undertreated in SCI.6,7 The usual management pathway for someone with SCI and symptoms of OSA involves a referral to specialist respiratory services for investigation and treatment.8 However, people with SCI9 and rehabilitation doctors8 have reported difficulty accessing specialist sleep services.

OSA in the general population is also common, with prevalence estimates of 9% to 38%.10 In response to this high prevalence and consequent burden on specialist services, several clinical trials have compared primary care management of uncomplicated OSA to sleep specialist management. An individual participant meta-analysis of four randomized trials in the general population found patient outcomes were similar in both models, but primary care was more cost-effective.11 Consequently, there is ongoing effort in Australia and elsewhere to shift the management of uncomplicated sleep disorders, including OSA, to primary care.12

To improve access to treatments for OSA in SCI, our group has been investigating alternative nonspecialist models. We have described the management models of three international SCI rehabilitation centers (in Canada, Switzerland, and The Netherlands) that routinely screen, diagnose, and treat uncomplicated OSA in people with SCI during rehabilitation. These models were developed in response to limited access to specialist sleep services. Each center had a small, multidisciplinary team who conducted assessments and treatments on the inpatient ward using ambulatory equipment. Sleep or respiratory specialist referral was reserved for complicated cases only, such as those with preexisting lung disease. The common pathways and elements of the three flagship centers were distilled into a single care model, suitable for adaptation and implementation elsewhere.13

Studying the factors involved in successful implementation of health care practices in flagship or “early adopting” sites can guide implementation elsewhere.14 We previously conducted a retrospective, theoretical analysis of the key, common enablers to rehabilitation-led OSA management at the three flagship centers, using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF).13 The TDF is a commonly used determinant framework to support analysis of barriers and enablers to health care practices.15 Their OSA management models were embedded in the rehabilitation programs of the respective centers and had evolved over many years. We hypothesize that similar models could substantially improve access to diagnosis and treatment without compromising effectiveness. However, understanding how to adapt and implement a similar model of care in a center that has never provided it before, and whether it is feasible to do so, would be an essential precursor to testing this hypothesis.

Translating evidence into clinical practice requires careful planning using structured and evidence-based approaches. The Knowledge to Action (KTA) framework describes the process of moving research evidence into practice.16 Knowledge creation is represented as a funnel in the center of the cycle, organizing knowledge from its least to most tailored forms. The action cycle describes the seven phases that are needed to effectively translate the knowledge into clinical practice:

Identify the problem

Adapt knowledge to local context

Assess barriers to knowledge use

Select, tailor, implement interventions

Monitor knowledge use

Evaluate outcomes

Sustain knowledge use

These phases can occur sequentially, simultaneously, or iteratively.

Guided by implementation and behavior change theories and frameworks,15-17 this project aimed to develop and implement a new OSA management model in an SCI rehabilitation center in Australia. The specific objectives were to adapt the previously described model of rehabilitationled OSA management13 for an SCI rehabilitation center in Australia (KTA phase 2), to analyze site-specific barriers and enablers to implementation (KTA phase 3), and to develop and deliver tailored interventions to address the identified barriers (KTA phase 4). The outcomes of the pilot implementation project (KTA phases 5-7) will be reported separately.

Methods

This collaborative project was initiated by clinicians from a rehabilitation center in Australia, who approached researchers investigating alternative models for managing OSA in SCI. The project was overseen by a clinical advisory committee that included the researchers, SCI rehabilitation clinicians (physicians, physiotherapists, and nurses), and respiratory experts (respiratory and sleep physicians, physiotherapists). Human Research Ethics approval was received.

The scope of this project was aligned with phases 2, 3, and 4 of the KTA framework. Methods and results are reported against these phases. This was an iterative process, and many of the activities occurred concurrently. Table 1 summarizes the methods used.

Table 1.

Summary of methods used to address the three phases of the Knowledge to Action (KTA) cycle

| KTA phase | Methods/Activities |

|---|---|

| Adapt knowledge to local context | Six stakeholder meetings/workshops with clinical advisory committee to:

|

| Assess barriers to knowledge use |

|

| Select, tailor, and implement interventions |

|

Note: OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Adapt to the local context

The clinical advisory committee attended a series of six meetings and workshops over 8 months to adapt and develop the common care pathway of the three flagship centers. This was a highly collaborative process, involving the rehabilitation and respiratory clinicians and researchers, to ensure that the model was evidence-based, feasible, safe for patients and clinicians, and suited to the local context. Through an iterative process of discussion, review, and feedback, the clinical advisory committee adapted the model of care that included clear processes for assessments, diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing management. Particular attention was paid to developing parameters for safe clinical practice and establishing referral pathways for patients requiring specialist management.

Assess barriers to knowledge use

Previously published analyses of the barriers and enablers to rehabilitation-led OSA management were collated and summarized.13 Using this knowledge, the researchers and local clinicians undertook a needs analysis to identify the modifiable barriers that could be addressed in the local setting prior to implementation of the new model of care. These were mapped to the TDF to help guide the development of interventions.15

Select, tailor, and implement interventions

With support from the clinical advisory committee, the researchers identified potential behavior change interventions that would target barriers to implementation. Each barrier was first linked with one or more of nine broad categories of behavior change interventions (e.g., education, training).17 These were further developed according to the mode of delivery (e.g., face-to-face skills training) and content (e.g., CPAP mask-fitting practice), ensuring feasibility and local relevance.18 All were delivered prior to implementation of the new care model.

Results

Adapt knowledge to local context

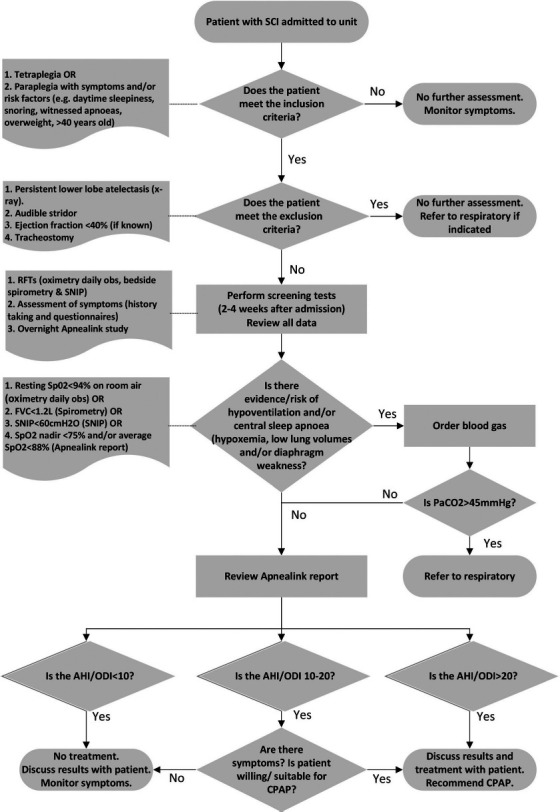

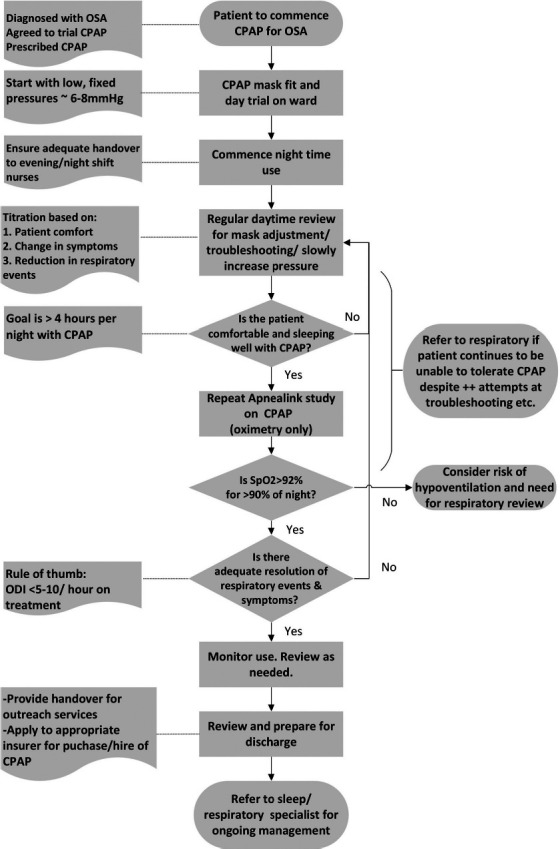

The multidisciplinary team that was selected to deliver the service comprised two rehabilitation medicine physicians, two physiotherapists, and four nurses from the SCI unit. The assessment and treatment pathways are presented in Figures 1 and 2 and summarized below.

Figure 1.

Clinical assessment pathway for obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) diagnosis. AHI/ODI = apnea hypopnea index/oxygen desaturation index; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; obs = observations; RFTs = respiratory function tests; SNIP = sniff nasal inspiratory pressure.

Figure 2.

Clinical treatment pathway. CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Assessments

All patients admitted to the specialist SCI rehabilitation unit with tetraplegia, and those with paraplegia with OSA risk factors and/or symptoms, are screened within 4 weeks of their admission. Those with persistent lower lobe atelectasis on radiograph, audible stridor, an ejection fraction of <40%, or a tracheostomy are excluded from the service. Symptoms and risk factors, such as daytime sleepiness, snoring, witnessed apneas, and overweight/obesity, are assessed with a clinical interview, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (alternative version for people with disability, ESS-ALT),19 Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS),20 and Berlin questionnaire (category 1 only).21 Respiratory function assessments include pulse oximetry to measure resting daytime oxygen saturation, spirometry to measure forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and sniff nasal inspiratory pressure (SNIP) to assess diaphragm strength. Presence and severity of OSA is assessed with a Level III overnight sleep study (ResMed ApneaLink Air).

Screening and referral for hypoventilation

An arterial blood gas is required if any of the following thresholds are met upon respiratory testing: resting daytime peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) <94%, FVC <1.2 L, SNIP <60 cm H2O, or overnight oximetry showing SpO2 nadir <75% or SpO2 <88%. If the blood gas reveals a partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) >45 mm Hg, the patient is referred to a respiratory physician for further investigations and management.

Diagnosis

The sleep study report is reviewed by the rehabilitation physicians in consultation with the multidisciplinary team. In line with the three flagship centers, an apnea hypopnea index (AHI) and/or 3% oxygen desaturation index (ODI) >20 events per hour is generally considered positive for OSA and treatment is recommended; an AHI and/or ODI <10 is considered negative for OSA and treatment is not recommended; and an AHI and/or ODI of 10 to 20 is carefully considered in relation to the patients symptoms, the likelihood they will benefit from CPAP, and their willingness to trial CPAP before a diagnosis is made. Results are discussed with the patient and, if appropriate, a trial of CPAP is offered.

Treatment

CPAP is initiated and progressed by the clinical team on the ward. Following the initial mask fitting and day trial, CPAP is initiated at night. The patient is generally started on a low, fixed pressure (∼6-8 mm Hg) and is regularly reviewed to adjust the mask, troubleshoot any issues, and gradually up-titrate the pressure. When the patient is comfortable and sleeping with CPAP (>4 hours per night), the overnight sleep study (oximetry only) is repeated. If the clinical team are satisfied with the reduction in respiratory events and symptom resolution, the patient is monitored and reviewed prior to discharge. Otherwise, the cycle of troubleshooting and review continues.

Discharge and ongoing care

Upon discharge, patients using CPAP are referred to a specialist respiratory service for ongoing management. The interim management plan is handed over to the local outreach team.

Assess barriers to knowledge use

Table 2 provides a summary of the published barriers and enablers to rehabilitation-led management of OSA, the corresponding TDF domains, and results of the local needs assessment. Establishing a local multidisciplinary team to deliver the service was a priority. Strong clinical leadership and the belief that OSA diagnosis and treatment is within the rehabilitation team's scope of practice were not considered barriers because the head of the unit had initiated and driven this collaborative project (TDF domains: Social/Professional roles and identity; Social influences). The local clinical team had minimal experience with OSA assessment, diagnosis, and treatment initiation and progression. Therefore, improving their knowledge and skills were identified as important targets (TDF domains: Skills; Knowledge; Beliefs about capabilities). Routine, clear, and embedded processes were clearly required for successful local implementation (TDF domain: Memory, attention and decision processes). The three flagship centers had dedicated, respiratory trained nurses or respiratory therapists. However, there was no funding to support additional staffing at the local center, meaning the model of care had to be delivered by the rehabilitation team within their existing roles. Funding to support the purchase of equipment was available (TDF domain: Environmental context and resources). Confidence and optimism in the new model of care had not yet been established (TDF domains: Beliefs about consequences; Optimism).

Table 2.

Assessment of the modifiable barriers to providing the obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) model of care

| TDF domain(s) | Previously published enablers | Previously published barriers | Local needs analysis and identification of need | Is this a modifiable barrier that can be feasibly addressed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social/Professional roles and responsibilities | Multidisciplinary, collaborative teams with clear roles and responsibilities | Unclear team roles and responsibilities | Yes | |

| Social influences | Strong leadership/clinical champion | Belief that diagnosis / treatment of OSA is outside rehab physician scope of practice. | Director of SCI rehabilitation center instigated this project and believes it is within the scope of practice. | No |

| Skills; Knowledge; Beliefs about capabilities | Highly skilled, confident clinicians | Lack of necessary skills to diagnose and treat OSA. Lack of confidence in ability to diagnose and treat. | Limited experience with sleep apnoea management resulting in limited knowledge, skills and confidence. | Yes |

| Environmental context and resources | Dedicated time for nurses/therapists to deliver the OSA service | Not enough trained clinical staff (nurses/allied health) | No resources available to support dedicated staff time. Service to be delivered within existing staffing arrangements. | No |

| Ample diagnostic and treatment equipment available | No diagnostic equipment and CPAP machines/masks, etc. | Yes | ||

| CPAP funded only if diagnosis/prescription made by sleep specialist. | Some local CPAP funding schemes require sleep specialist prescription. | Yes | ||

| Beliefs about consequences; Optimism | Belief that CPAP is beneficial; Strong belief in the benefits of their service | Belief that adherence to CPAP may be poor | Team unclear on benefits of model of care. | Yes |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | Routine processes and clear pathways | — | New to OSA management. No processes or pathways in place. | Yes |

Note: CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; TDF = Theoretical Domains Framework.

Select, tailor, and implement interventions

Table 3 describes the interventions that were developed to address the local barriers to implementation. An in-person education and skills-training program was developed and delivered to the clinical team over a 3-day period to improve knowledge and skills. The program included a mix of practical, hands-on skills training and tutorial-style education, and it was delivered by respiratory clinicians and an implementation scientist. (See Appendix A, Detailed Outline of Education/ Training Program.) Two manuals were developed to support the assessment and treatment pathways, and existing educational materials were collated. All materials were available in both hard copy and electronic formats. Persuasive communication and modelling techniques were incorporated into the training to promote confidence and optimism among team members. These techniques included showing videos of people with SCI discussing the benefits of CPAP and presenting examples of alternative OSA care models and evidence of their effectiveness.

Table 3.

Interventions developed to support the implementation of the model of care

| TDF domain(s) | Barrier | Intervention types | Intervention modes | Intervention content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge, skills | Limited knowledge and skills to enable assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of OSA | Education and skills training | Face-to-face and online education and practical skills training was delivered to the clinical team over a 3-day period. | Topics covered:

(See Appendix A for a detailed summary of the education and training program.) |

| Education (provision of written information) | Manuals and other written support materials were developed and collated and were provided in hard copy and online in shared drive. | New manuals developed:

Other collated resources: |

||

| Enablement (remote clinical support / mentoring) | Respiratory/ sleep specialist - acute hospital in Sydney | Email or telephone support/advice regarding results of diagnostic tests and treatment prescription | ||

| Enablement (remote implementation support) | Respiratory physiotherapist - acute hospital in Melbourne | Email or telephone support/advice regarding CPAP initiation and progression | ||

| Implementation support from researchers | Email or telephone support/advice regarding implementation issues. | |||

| Memory, decision processes | Unclear screening, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment pathways and processes | Enablement (action planning); environmental restructuring | Pathways clearly defined and documented, including referral pathways | (See Figures 1 and 2 for assessment and treatment pathways.) |

| Roles and responsibilities | Unclear team roles and responsibilities | Enablement (action planning); social restructuring | Roles allocated; workflow defined and documented | (See Appendix B for summary of the team roles and workflow.) |

| Environment context | Lack of diagnostic and treatment equipment | Environmental restructuring (equipment acquisition) | Equipment purchased or donated | Level III sleep study devices:

Handheld spirometer and SNIP device: CPAP machines

CPAP masks of a variety of sizes |

| CPAP funding schemes require sleep specialist prescription | Enablement (remote specialist support) | Remote support from sleep physician at local acute hospital | Sleep physician available to review assessments and prescribe CPAP if appropriate and required | |

| Beliefs about consequences; optimism | Team unclear on benefits of managing sleep apnea in rehabilitation environment | Modelling; persuasive communication; education | Education and training to include persuasion about capability and demonstration of successful OSA care models |

|

Note: CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; TDF = Theoretical Domains Framework.

Authors are not recommending one commercially available product over another.

Remote, ad hoc clinical support for patient-related assessment, diagnosis, and treatment queries was incorporated into the model of care. The rehabilitation physician could contact a local respiratory physician from the referring acute hospital for clinical advice related to diagnosis and treatment prescription. Respiratory physiotherapists were available for remote advice on CPAP initiation, troubleshooting, and treatment progression. As discussed, clinical pathways were developed with the clinical team (Figures 1 and 2) who also assigned and documented the individual roles and responsibilities to ensure clarity and maximize efficiency. (See Appendix B, Team Roles and Workflow.)

CPAP devices (ResMed AirSense10; ResMed Inc., San Diego, California), masks of different types and sizes, a hand-held spirometer, Level III sleep study devices (ResMed Apnealink Air; ResMed Inc., San Diego, California), and a MicroRPM (Vyaire Medical Inc., Chicago, Illinois) to measure SNIP were all acquired. For instances where specialist prescription of CPAP was required for funding, the local sleep specialist offered to remotely review the patient and formally prescribe the treatment, if indicated and appropriate.

Discussion

The OSA model of care was implemented in July 2022. To our knowledge, this is the first time that an SCI rehabilitation center, with minimal prior experience in sleep disorder management, has systematically implemented a new model for managing OSA. The previously studied rehabilitation-led OSA care models had grown organically over time.13 Our systematic approach to implementation had several notable strengths. Model of care adaptations were developed in partnership with the clinicians who would deliver it. Our series of workshops and meetings to adapt the care model were highly collaborative and included the doctors, nurses, and physiotherapists from within the rehabilitation center who had formed the clinical team and the local respiratory physician who offered to support the team. There were no resources to support additional staff time on this project. The team of four nurses, two physiotherapists, and two rehabilitation doctors needed to integrate the assessment and treatment processes into their existing workloads, and therefore high levels of engagement were essential.

Interventions aiming to improve the delivery of health care are more likely to be effective if they are tailored to the barriers to that behavior22 and are informed by behavioral theories.23 We incorporated behavior change theories and frameworks to assess the potential barriers and to design solutions to address them.16-18 Our prior research had established the common enablers or “key ingredients” to the successful flagship models using the TDF.13 Using this, we assessed the capacity of local rehabilitation team to identify potential barriers that could be targeted before implementation. Tailored interventions were then developed and delivered to specifically address these potential barriers. A similar theory-informed approach to understanding barriers and developing targeted interventions was recently undertaken in a rehabilitation setting aiming to introduce evidence-based goal-setting practices.24 These projects provide examples for other rehabilitation centers to assess their readiness for change and maximize successful implementation of new, evidence-based programs.

As part of the development process, we developed a screening algorithm for the risk of undiagnosed sleep-related hypoventilation (SRH). SRH is a rare5 but potential serious condition in SCI because it can lead to hypercapnic respiratory failure, however detecting it can be challenging. In a sleep laboratory, SRH is usually assessed with evening and morning arterial blood gases and transcutaneous CO2 monitoring throughout the night. Unfortunately, arterial blood gases were not readily available at the rehabilitation center. The algorithm we developed only requires an arterial blood gas to rule out SRH if conservative thresholds for resting daytime SpO2, FVC, SNIP, overnight SpO2 nadir, or average SpO2 are detected (Figure 1). If the subsequent blood gas demonstrates PaCO2 >45 mm Hg, the patient is referred to a respiratory specialist for further assessment and ongoing management. This algorithm could be adopted by other centers with poor access to arterial blood gases, however more research is needed to validate this approach.

The model of care is being piloted for a 12-month period. The comprehensive mixed-methods evaluation is guided by the RE-AIM framework to assess outcomes related to reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance.25 The evaluation includes both quantitative and qualitative components. Routinely collected clinical data are collated from those who receive any element of model of care to assess reach (i.e., how many people with SCI were screened, diagnosed, treated) and effectiveness (i.e., CPAP usage, change in daytime sleepiness). Patients and staff will participate in a semi-structured interview to explore their experience of the model of care, including the barriers and enablers (adoption), any adaptations that were made during the pilot period (implementation), and plans for ongoing delivery (maintenance). The outcomes of the evaluation, including recommendations for future research and implementation efforts, will be published separately.

Limitations

This project had several limitations. We did not have the resources to enable a full analysis of the local potential barriers prior to implementation and were therefore restricted to assessing these in relation to previously published barriers and enablers. We did not have the resources to enable and support dedicated time for the clinical team members (i.e., nurses or physiotherapists) to undertake the assessments and CPAP initiation. As such, our evaluation will assess whether it is feasible for a rehabilitation center to provide this model of care within existing staff resources. Unfortunately, due to issues outside of our control, including COVID lockdowns, limited funding, and travel barriers, our attempts to partner with people with SCI from the beginning of the project were unsuccessful. Two people with SCI joined the clinical advisory committee soon after the model was implemented and have been recommending ongoing adaptations to the model and supporting the evaluation. Research co-design has been defined as “the meaningful involvement of research users during the study planning phase of a research project.”26 Co-design has been described as a powerful approach to service design and improvement because of its potential to enhance relevance, minimize waste, and facilitate sustainable change.26 Wherever possible, SCI rehabilitation centers planning to implement a similar care model should engage and partner with people with SCI from the early planning stages of the project.

Conclusion

Most SCI rehabilitation centers do not routinely screen for OSA and refer those with obvious signs and symptoms to specialist respiratory management.8 However, despite the high prevalence of OSA, most people with SCI remain undiagnosed and untreated. Rehabilitation-led management of noncomplicated OSA has been proposed as one potential solution for people with SCI. In this article, we describe a systematic and theory-informed process of preparing an SCI rehabilitation center for implementation of a new OSA management model by developing the model of care, assessing the potential barriers, and delivering interventions to overcome them. This article presented the adapted OSA model of care and summarized the interventions developed to address local barriers. These methods and results can be used by other rehabilitation centers and teams that may be planning to implement an alternative model of managing OSA.

APPENDIX A

Detailed Outline of Education/Training Program

Session 1: Overview of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in SCI (1 hour, presentation with discussion)

- Sleep in SCI

- Brief overview

- Impacts of poor sleep

- Causes of poor sleep

- Common sleep disorders

- What is SDB?

- Obstructive sleepiness apnea (OSA) vs. central sleep apnea (CSA) vs. sleep-related hypoventilation (SRH)

- Pathophysiology

- SDB in SCI

- Epidemiology

- Causes

- Clinical features/symptoms

- Risk factors

- Measurement and diagnosis of SDB

- Questionnaires

- Types of sleep studies (Level 1-4)

- Metrics: Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI), Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI), Oxygen Desaturation Index (ODI)

- Treatment of SDB in SCI

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) – how does it work?

- Adherence – rates and what influences adherence?

- Other treatments (bi-level positive airway pressure (PAP), mandibular advancement device, positional therapy, lifestyle interventions)

Session 2: How to perform the screening tests (1 hour, practical session with presentation)

- Screening for symptoms

- Daytime sleepiness (Karolinska Sleepiness Scale [KSS], Epworth Sleepiness Scale-alternative version for people with disability [ESS-ALT])

- Sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index)

- OSA risk (Berlin)

- Level III sleep study (ResMed ApneaLink)

- Setting up the device

- Donning/doffing

- Downloading data and creating report

- Respiratory function tests (RFTs)

- Spirometry

- Sniff nasal inspiratory pressure (SNIP)

- Risk of hypoventilation

- Daytime oximetry

Session 3: CPAP treatment (1-1.5 hours, practical session with presentation)

Machine basics

Masks and fitting

Initial setting and progressing treatment

Cleaning and maintenance

Common problems and troubleshooting

Safety considerations

Daytime set-up process and mask fit (on patient)

Session 4: Education for evening and night shift nurses (practical, 30 mins)

ResMed Apnealink (patient set-up)

- CPAP basics

- ResMed Airsense devices

- Mask fit

- Troubleshooting common issues overnight

Session 5: Overview of model of care/team meeting (75 mins; team discussion)

Overview of processes and roles

Resources available

Evaluation overview

Session 6: Interpreting the results to make a diagnosis (1.5 hours, interactive session with case studies and presentation)

- Symptoms

- What matters?

- Scoring and interpreting questionnaires (KSS, ESS-ALT, Berlin)

- Interpretation of sleep study results

- Automated report metrics

- Raw traces (obstructive vs central events)

Interpretation of RFTs in relation to SDB diagnosis

Three case studies – group discussion

- Putting it all together

- Is the patient suitable for treatment?

- When to refer/seek advice

Other education provided:

Downloading ResMed ApneaLink and CPAP data (using the software)

Masks and equipment (ordering, safety and infection control)

Clarifying referral pathways

Communication and resources

APPENDIX B

Team Roles and Workflow

| Stage | What | Who? When? Where? |

|---|---|---|

| Screening tests |

1. Subjective symptoms and risk factors

|

Clinical Care Coordinators (CCC)

|

2. Respiratory function

|

Physiotherapists

|

|

3. Hypercapnia risk screen

|

Day nurses (usual daytime observation) | |

4. Level III sleep study

|

CCCs and evening/night nurses

|

|

| Review screening data |

1. Subjective symptoms and risk factors

Includes basic summary of symptom severity? (e.g., ESS of >16 = severe daytime sleepiness). |

CCC to review and summarize |

2. Respiratory

|

Physiotherapists to review and summarize

Doctors to order blood gas if needed |

|

3. Hypercapnia risk

|

Doctors to review results and order blood gas if needed | |

4. ResMed Apnealink (Level III sleep study)

“Rule of thumb” for AHI and ODI thresholds:

|

Doctors to review and summarize

|

|

| Diagnosis and treatment prescription | 1. Review and discuss all results to decide whether patient has SDB and could benefit from treatment |

Doctors responsible for the diagnosis and management plan. Requires information and judgment from the whole team. Discussed in weekly team meeting. |

2. If patient is suitable for treatment, discuss results with patient and explain the treatment and potential benefits.

|

Doctors to discuss results with patient | |

| 3. If patient accepts CPAP trial, refer to physio for CPAP initiation. | Doctors to prescribe CPAP and refer to physio for initiation. |

Note: AHI = apnea hypopnea index; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale; KSS = Karolinska Sleepiness Scale; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Funding Statement

Financial Support To support this project, the following grants were received: Australasian Sleep Association Rob Pierce Grant in Aid and Australian and New Zealand Spinal Cord Society: Small Research Grant. CPAP masks were donated for this project by ResMed and Phillips Respironics.

Footnotes

Adherence to Ethics

Ethical approval was received by the Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC: 2021/ETH11323).

Conflicts of Interest

M.G., D.B., and C.L.C. have been involved in research studies that have received equipment and/or funding support from ResMed and Philips Respironics. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berlowitz DJ, Spong J, Gordon I, Howard ME, Brown DJ. Relationships between objective sleep indices and symptoms in a community sample of people with tetraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(7):1246–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sankari A, Badr MS, Martin JL, Ayas NT, Berlowitz DJ. Impact of spinal cord injury on sleep: Current perspectives. Nature Sci Sleep. 2019;11:219. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S197375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graco M, McDonald L, Green SE, Jackson ML, Berlowitz DJ. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in people with tetraplegia—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spinal Cord. 2021;59(5):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41393-020-00595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graco M, Ruehland W, Schembri R, et al. Prevalence of central sleep apnoea in people with tetraplegic spinal cord injury: A retrospective analysis of research and clinical data. Sleep. 2023 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsad235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berlowitz DJ, Schembri R, Graco M, et al. Positive airway pressure for sleep-disordered breathing in acute quadriplegia: A randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2019;74(3):282–290. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns SP, Rad MY, Bryant S, Kapur V. Long-term treatment of sleep apnea in persons with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(8):620–626. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000171008.69453.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sankari A, Martin J, Badr M. A retrospective review of sleep-disordered breathing, hypertenstion and cardiovascular diseases in spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord. 2015;53(6):496. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graco M, Berlowitz DJ, Green SE. Understanding the clinical management of obstructive sleep apnoea in tetraplegia: A qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):405. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graco M, Green SE, Tolson J, et al. Worth the effort? Weighing up the benefit and burden of continuous positive airway pressure therapy for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea in chronic tetraplegia. Spinal Cord. 2019;57(3):247. doi: 10.1038/s41393-018-0210-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senaratna CV, Perret JL, Lodge CJ, et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Ryswyk EM, Benítez ID, Sweetman AM, et al. Primary vs. specialist care for obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and individual participant data level meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19(4):668–677. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202105-590OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai-Coetzer CL, Redman S, McEvoy RD. Can primary care providers manage obstructive sleep apnea? J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(1):1–2. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graco M, Gobets DF, M O'Connell C, et al. Management of sleep-disordered breathing in three spinal cord injury rehabilitation centers around the world: A mixed-methods study. Spinal Cord. 2022:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41393-022-00780-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor N, Best S, Martyn M, et al. A transformative translational change programme to introduce genomics into healthcare: A complexity and implementation science study protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e024681. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: A consensus approach. Qual Safe Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French SD, Green SE, O'Connor DA, et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: A systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gronewold J, Lenuck MCI, Gülderen I, et al. Developing an alternative version of the Epworth sleepiness scale to assess daytime sleepiness in adults with physical or mental disabilities. Gerontology. 2021;67(1):49–59. doi: 10.1159/000511361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Åkerstedt T, Gillberg M. Subjective and objective sleepiness in the active individual. Int J Neurosci. 1990;52(1-2):29–37. doi: 10.3109/00207459008994241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(7):485–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005470.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021:374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker A, Cornwell P, Gustafsson L, Stewart C, Lannin NA. Developing tailored theoretically informed goal-setting interventions for rehabilitation services: A co-design approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1–21. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co-design in health: A rapid overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-0528-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]