Abstract

Limited knowledge on dementia biomarkers in Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries remains a serious barrier. Here, we reported a survey to explore the ongoing work, needs, interests, potential barriers, and opportunities for future studies related to biomarkers. The results show that neuroimaging is the most used biomarker (73%), followed by genetic studies (40%), peripheral fluids biomarkers (31%) and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers (29%). Regarding barriers in LAC, lack of funding appears to undermine the implementation of biomarkers in clinical or research settings, followed by insufficient infrastructure and training. The survey revealed that despite the above barriers, the region holds a great potential to advance dementia biomarkers research. Considering the unique contributions that LAC could make to this growing field, we highlight the urgent need to expand biomarker research. These insights allowed us to propose an action plan that addresses the recommendations towards a biomarker framework recently proposed by regional experts.

1. Introduction

Dementia in Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries is a major public health challenge [1-4]. The prevalence of dementia in LAC countries among individuals of 65+ years of age is higher than in Europe and the United States, ranging from 7.1% to 11.5%, and is expected to triple by 2050 [5-7]. It has been estimated that currently, over 58% of all people living with dementia in Lower-Middle Income Countries (LMIC) and that will increase to 68% in 2030 [8, 9]. Importantly, most of the LAC countries are classified in the “upper-middle income group” (UMIC). Here, we report on the results from an online survey completed by dementia specialists from 2 HIC (Chile and Uruguay) and 8 UMIC (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru) [10].

1.1. Dementia diagnosis harmonization in LAC: challenges

The diagnosis of dementia has evolved from a purely clinical process to become a more complex exercise that integrates neuropsychological and biomarker evidence [11, 12]. The former requires culturally adapted and validated instruments that are sensitive and specific to a wide range of age-related diseases that cause cognitive impairment. It also relies on clinically experienced examiners who are up to date in current challenges. The latter includes central (i.e., imaging) and peripheral methodologies, both heavily reliant on highly specialized personnel, expensive technologies and sophisticated analytical tools [13, 14].

1.2. Biomarkers in dementia

Biomarkers are indicators that objectively measure and evaluate normal or pathological biological processes [15]. Currently validated biomarkers in AD are amyloid-β42 (Aβ42), total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) proteins, which are measured in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [16-20]. In addition, neuroimaging studies are also considered biomarkers validated for AD diagnosis, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) with F18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and PET with the use of tracers for Aβ and tau in vivo [21-28]. Validated central biomarkers have been grouped into three categories: A/T/N, where A refers to Aβ markers (PET Aβ or Aβ42 in CSF); T to tau markers (p-tau in CSF or tau PET) and N to neurodegeneration markers (FDG-PET, MRI or total tau in CSF) [11, 29]. To date, CSF and neuroimaging biomarkers have proved of great utility. However, they are not easily accessible to patients. For this reason, multiple investigations have focused on the identification of biomarkers in peripheral fluids where it is possible to detect early pathological changes that occur in the brain during the development of dementia [30] thus proving promising for intervention strategies. Importantly, peripheral biomarkers have the potential to be accessible to people living far from capital cities where the infrastructure to perform central biomarker assessments is normally located. This entails a significant reduction of costs thus enhancing equity in dementia diagnosis. Peripheral biomarkers can be different molecules such as proteins, peptides, nucleic acids, microRNAs (miRNAs), lipids and metabolites which can be detected in plasma, serum, exosomes or cellular components [31-33]. The investigation and development of peripheral biomarkers, specifically blood-based biomarkers for dementia, are in early stages. Ongoing efforts are focusing on their clinical evaluation and validation to explore opportunities for their future integration into clinical practice [34]. Since heritability rates for dementia range from 40% to 80%, other biomarkers commonly evaluated are genetic [35]. Some genes involved in dementia are: amyloid precursor protein (APP) [36], presenilin-1 (PSEN1) [37], presenilin-2 (PSEN2) [38], chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) [39], granulin precursor (GRN) [40], and microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) genes [41], among other. In addition, some specific pathway genes have also been associated with increased risk, such as APOE Ɛ4 [42].

1.3. Biomarkers in LAC: the status quo

The biomarkers suggested by recent consensus [11, 29] are both scarce and scattered in LAC [43, 44]. Regarding PET scans, economic and political factors were identified as barriers to advances in PET imaging in LAC. Among others, the lack of infrastructure was highlighted (e.g., neighboring cyclotron) [45]. Since these earlier reports, we have witnessed the emergence of multiple PET facilities in LAC (Instituto Neurologico Fleni in Buenos Aires, Argentina; University of São Paulo-USP and PUC-RS in Porto Alegre, Brazil; Centro Uruguayo de Imagenología Molecular CUDIM in Montevideo, Uruguay; and Instituto Nacional de Neurologia y Neurocirugia (INNN) in Mexico City, Mexico) [46-52]. Regarding CSF, sample collection is the main barrier identified in LAC. The invasiveness of this procedure poses significant limitations to its wide use and acceptance [43]. Nevertheless, a few examples are worth highlighting. Argentina and Brazil have conducted studies using CSF biomarkers. They have reported differences between controls, cognitively impaired patients, AD, and other types of dementia [46, 53-57]. In Colombia, CSF biomarkers were evaluated in young (40-50 years old) carriers of PSEN1 mutation and non-carriers, where clear differences in Aβ1-42 were identified between the two groups, which correlates with the clinical progression of this familial variant of AD [58].

The above-mentioned examples are drawn from a limited set of labs and countries. Such labs are confined to centers specialized in dementia, such as memory clinics, where there is more experience in the diagnosis of dementia [59]. Additionally, LAC’s native populations are characterized by a combination of demographic, ethnic, genetic, and socio-cultural factors that enable the investigation of biomarkers profiles linked to dementia risk difficult to identify in other parts of the world. Given the ancestry and genetic admixture that characterize LAC [1, 2] such studies are of a great importance.

1.4. Emerging biomarkers in LAC: opportunities

Since dementia has been declared a global challenge, the regional and international community must come together to devise and implement regional and global strategies. There are now a few recent examples from LAC that support the impact of joint efforts. The Latin America and the Caribbean Consortium on Dementia (LAC-CD) and The Multi-Partner Consortium to Expand Dementia Research in Latin America (ReDLat) are two prominent initiatives that have highlighted the need to harmonize practice across LAC and have proposed a new knowledge-to-action plan that includes a Biomarker Framework [3, 44, 60, 61]. Briefly, LAC-CD, at the time this survey study was run, involved 172 members from Central and South American countries with an interest and different levels of expertise in dementia research and clinical practice [61]. They have been working collaboratively from 2015 to identify opportunities, formulate an integrated agenda, promote collaborative research and training, harmonize clinical practices, and raise awareness in dementia at all levels (http://lac-cd.org/en/about-us/). ReDLat, a research project involving 13 sites across Latin America and the US, aims to expand open regional research by combining genomic, social determinants of health, neuroimaging, and cognition in over 4,000 individuals to improve the characterization of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (same ref as above). Recently, the Latin American Brain Health Institute (BrainLat) has been established as a result of a partnership between the University Adolfo Ibañez of Chile and the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI), which is an initiative of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) and Trinity College Dublin (TCD) (https://brainlat.uai.cl/). In Mexico, the National Dementia BioBank (BND) has been implemented [62]. The readiness of LAC to embark on such plans has been acknowledged [43], placing the region in a unique position to move towards more ambitious targets such as a harmonized and global biomarker framework [3, 63].

An emergent area that holds significant potential for LAC is that of peripheral biomarkers [64-66], involving different molecules such as proteins (including plasma Aβ42/Aβ40, plasma p-Tau and plasma neurofilament, which cover the amyloid/tau/neurodegeneration (ATN) framework for AD diagnostics in CSF, but also other proteins, e.g., inflammation markers), peptides, nucleic acids, miRNAs [66], lipids and metabolites [65]. The advantage of peripheral biomarkers over CSF is the easy, less invasive, and inexpensive sample collection (plasma, serum, urine, among others) [67]. Because biomarkers in peripheral fluids minimize risk and discomfort for patients, thus expanding their applicability in an aging population, large-scale peripheral fluid-based tests can become the primary tool and the first step in a dementia diagnostic process. They can become screening tools that can inform who should then undergo more expensive and invasive assessments, such as CSF biomarkers or neuroimaging [68]. A peripheral fluid-based test could also be useful for monitoring therapeutic outcomes, especially if repeated measurements are required over a short period of time as they may be more accessible in low-resource and non-specialized settings [69, 70]. In the future, these early detection biomarkers in peripheral fluids would also be useful in the development of clinical trials of new drugs, allowing a more accurate selection of individuals who meet the necessary criteria to participate in such trials [34, 70-72].

Aware of the above challenges and opportunities, we decided to further investigate regional realities in LAC. We focused on central biomarkers such as CSF as well as neuroimaging, peripheral fluids, and genetics biomarkers. This study was not only aimed at providing an updated picture of the biomarker realities in LAC but also to assess the level of interest and readiness the region holds to embark on biomarker research. We envisaged that this knowledge would help expand opportunities in the region to make biomarkers research more inclusive and representative, leveling the playfield, and in so doing enabling global biomarker agendas.

2. Methods

2.1. Survey generation, distribution, and data capture

The survey was developed by a group of professionals with extensive experience in the areas of biomarkers, dementia, neurology, psychiatry, and neuropsychology from LAC countries. Five meetings, involving multidisciplinary experts in the mentioned areas, were held to create the survey including the co-authors: MAP, CDA, AD, AS, FH, PO, and VC. The survey gathered the largest amount of information regarding the status of central, peripheral biomarkers, and genetic studies for dementia in LAC countries considered to date. It requested information regarding accrued experience, barriers, and level of readiness of centers and labs in the region. Our main goal was to identify shared concerns and opportunities present in the region which can allow us to align our agenda both regionally and with international initiatives.

The survey was distributed among the 172 members of LAC-CD (http://lac-cd.org/en/members/) via email. It was created as a Google Form and distributed in Spanish, Portuguese and English. The survey body comprised 90 different questions grouped by biomarker type (See also Supplementary Material Appendix 1) and it took approximately 20 minutes to complete. It was first sent on August 15th, 2020, followed by two reminders (September 17th 2020 and March 7th 2021) with a total period of availability of eight months.

The survey started with a brief introduction of its objective and a brief presentation of the group leading this initiative. It requested general information such as country, profession, and workplace. The questions in the survey were linked to the following biomarker classes: Central biomarkers which included CSF and neuroimaging modalities; peripheral biomarkers which included fluids such as plasma, serum, whole blood, saliva, urine, deposition, ocular biomarkers, and others; and genetic studies which presented a list of different genes related to dementia and their subtypes. A set of questions were asked for each biomarker class including current use, purpose, barriers, funding, motivation to work with biomarkers and access to the population for research purposes. Questions were in the form of multiple-choice or open-ended (see Supplementary Material Appendix 1). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez, Chile.

2.3. Data analysis

The data were exported as a Microsoft Excel file and answers in the three different languages were organized into one document. The multiple-choice questions were scored and then converted to percentages. The open-ended questions were qualitatively analyzed and grouped in relation to predefined criteria: access to study samples, published papers related to biomarkers in LAC, barriers, other types of funding, interest, and motivation (or lack of them) to work with specific biomarkers, among others. Empty, inconsistent, or incomplete data were discarded (n = 2). The figures were created by using GraphPad® Prism® 8.

3. Results

3.1. Responses

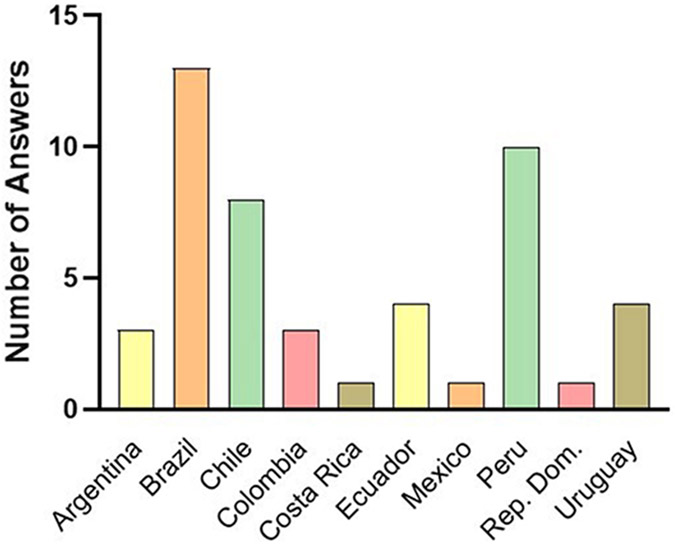

The survey was answered by 48 participants (28% of LAC-CD members) from 10 countries in total (Figure 1). The countries with the highest participation were Brazil (27%), Peru (21%), and Chile (17%). Of the 48 participants, 27 were male and 21 females. Their professional specialties were general practitioners (n=3), neurologists (n=26), psychiatrists (n=8), neurologist-psychiatrist (n=1), geriatricians (n=3), gastroenterologist (n=1), physician-neuropsychologist (n=1), neuropsychologists (n=2) and researchers (n=3). They reported to be associated to 37 public institutions, 9 private institutions and 2 public-private institutions, indicating that the majority of the participants (81%) worked in public institutions.

Figure 1. Distribution of survey responses from the 48 participants by country.

3.2. Biomarkers used, purposes and funding

In this section, we summarized the answers of the respondents related to biomarkers use and interest, purpose, and funding.

3.2.1. Biomarkers use and interest:

We divided the 48 respondents in those who are currently using biomarkers and those who are not using them, but are interested/uninterested in their future use. Neuroimaging is the biomarker that is currently most widely used, as reported by 35 respondents (73%), with 12 of the remaining respondents (25%) reporting they would be interested in using them and only 1 respondent (2%) reporting no interest in using this biomarker. On the other hand, CSF biomarkers are the least currently used with only 14 respondents reporting their use (29%). However, 22 respondents (46%) are interested in using them if available. There were 12 (25%) respondents who are uninterested in using this type of biomarker. Despite their novelty, peripheral fluid biomarkers are being used by 15 respondents (31%), and 26 (54%) reported an interest in their future use. Only 7 respondents (15%) are not interested in this type of biomarker. Finally, genetic biomarkers attracted similar number of responses regarding use (19, 40%) and interest (20, 41%), with 9 respondents (19%) reporting no interest in their use (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Biomarkers used, purposes and funding.

(A) Using, interested and uninterested respondents by type of biomarker. (B) Purpose of the use of biomarkers in LAC. (C) Funding sources for biomarker studies in LAC.

3.2.2. Biomarker purposes:

In the field of neuroimaging, from the 35 participants currently performing studies, half of them reported using these biomarkers for both clinical and research purposes (17 respondents, 49%), whereas their use in either clinical practice or research practice shared a similar trend, 8 (23%) and 10 respondents (29%), respectively). From the 12 respondents interested in future use of neuroimaging, 11 (92%) would like to perform neuroimaging for clinical and research purposes whereas only 1 respondent (8%) would like to use it only for research. In terms of CSF biomarkers, of the 14 respondents currently using them, 7 (50%) use them for research, 5 (36%) for clinical and research, and 2 respondents (14%) for only clinical purposes. Of the 22 participants interested in using CSF biomarkers in the future, 15 of them would like to use them for clinical and research purposes (67%) and 7 (33%) only for research. Regarding peripheral biomarkers, of the 15 respondents currently using them, 14 respondents are using them for research (93%) whereas only 1 respondent (7%) is using them for research and clinical purposes. Of the 26 respondents who are interested in using them in the future, 16 respondents would use them for research and clinical purposes (62%) and 10 only for research (38%). Finally, for genetics studies, of the 19 respondents interested in performing them, 13 respondents would use them for research (68%) whereas 6 (32%) would use them for clinical and research purposes. The participants who are not currently using biomarkers, 20 respondents, reported the purposes for which they would like to use them in the future: 15 respondents indicated interest in using them for research and clinical purposes (75%), 4 respondents for research only (20%), and 1 for clinical practice (5%) (Figure 2B).

3.2.3. Funding for Biomarkers:

Regarding funding opportunities to support the use of biomarkers, the respondents, using or interested, reported the funding type for each one of these biomarkers (neuroimaging, CSF, peripheral and genetic studies). The sum of answers of the respondents that currently work with biomarkers stated that most of their funding opportunities came from public grants (51%) followed by no funding (18%), private funds (13%), a mix between public and private funds (13%), and “other type of funding resources” (5%). However, this trend changes for the respondents that are interested in using biomarkers as a high number of respondents state a lack of funding opportunities (64%), followed by public grants (16%), “other type of funds” (9%), a mix of public and private funds (6%), and private funds (5%) (Figure 2C).

3.3. Biomarker specific characterization in LAC

In this section, we summarized the answers of the respondents related to the specific subtypes of biomarkers they are using or interested in using (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Biomarker characterization in LAC.

(A) Neuroimaging. (B) CSF biomarkers. (C) Peripheral fluids. (D) Genetic biomarkers.

3.3.1. Neuroimaging:

For neuroimaging biomarkers, 95 responses were recorded considering seven options of a multiple choice question. The modality of neuroimaging most commonly used corresponds to MRI (33 answers, 35%), followed by FDG-PET (16 answers, 17%), DTI (13 answers, 14%), amyloid PET (11 answers, 12%), fMRI (13 answers, 14%) and tau PET (4 answers, 4%) (Figure 3A). Concerning other types of neuroimaging methods, 5 (5%) use techniques such as SPECT, 18 F-fluoro-L-DOPA positron emission tomography (PET-DOPA), and brain tomography. The neuroimaging equipment most used is 1.5 and 3.0 Tesla with a clinical objective of patient evaluation and longitudinal follow-up. In addition, the most used MRI techniques for structural analysis in research are cortical thickness and Voxel-Based Morphometry (VBM), whereas the most used for functional analysis is the Resting-State fMRI. Of the 44 respondents not using neuroimaging biomarkers but interested in their future use, 9 (20%) expressed an interested in MRI, 9 (20%) in Tau PET, 8 (18%) in fMRI, 8 (18%) in FDG-PET, 8 (18%) shared a similar interest in these specimens but amyloid PET, 1 (2%) in DTI, and 1 (2%) in other not listed in the survey (Figure 3A).

3.3.2. CSF biomarkers:

For CSF biomarkers, a total of 43 responses were gathered reflecting their use by 13 (30%) for Aβ, 13 (30%) for t-Tau, 13 (30%) for p-Tau and only 4 (10%) search for other types of CSF biomarkers such as neurofilaments, neurotransmitters, inflammatory markers, and hormones. Interested respondents (n=61), indicated their motivation for Aβ (19, 31%), t-Tau (20, 33%), p-Tau (18, 29%) and other (4, 7%) such as neurofilaments, microRNAs, neurogranin and prion protein detection (Figure 3B). In addition, the most used technique to analyze biomarkers in CSF is Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and the techniques that would be chosen for CSF biomarkers analysis are Single Molecule Array (SIMOA) and ELISA.

3.3.3. Peripheral Biomarkers:

Regarding the main peripheral fluids, we obtained 34 responses, which showed a high tendency towards the study of blood samples and their components (83%) distributed as: 14 (41%) plasma, 7 (21%) serum, 7 (21%) whole blood. Other fluids used with less frequency correspond to 3 (9%) saliva, 1 (3%) deposition, 1 (3%) ocular biomarker, and other 1 (3%) like platelets. The number of interested respondents was similar to that using them, with 30 responses distributed as: 8 (27%) plasma, 6 (20%) serum, 5 (17%) whole blood, 5 (17%) saliva, 3 (10%) urine, 2 (7%) ocular biomarkers and 1 (3%) deposition (Figure 3C). Concerning the type of peripheral biomarkers in current use, we found a wide variety: neurodegeneration markers (Aβ, tau, P-tau, neurofilaments), inflammatory markers (i.e., cytokines, lactoferrin, lipoxin, annexin), hormones (cortisol, metabolomics), hemostatic markers, and miRNAs. Furthermore, regarding the percentage of the peripheral biomarkers they would be interested in using, most respondents mentioned neurodegeneration markers such as 35% Aβ, 35% t-Tau, 10% p-Tau, 8% neurofilaments, 2% TDP-43, and 2% neurogranin. Interestingly, 6% of responders stated they would be interested in using “all biomarkers that I could work with”. The currently used techniques to study peripheral biomarkers are ELISA, Cytometric Bead Array (CBA), Multiplex Luminex and SIMOA, and the techniques respondents prefer to use are ELISA and SIMOA.

3.3.4. Genetic studies:

From the multiple choice question 82 responses were obtained, reporting that the main genes assessed in genetic studies are: 16 (20%) ApoE, 9 (11%) MAPT, 9 (11%) PSEN1, 8 (10%) PSEN2, 8 (10%) APP, 7 (9%) C9orf72, 7 (9%) PGRN, 5 (6%) TREM2, 6 (7%) TARDBP, 3 (4%) perform GWAS analysis and 4 (5%) studied other genes such as PRNP, vitamin D receptor polymorphism, exome, Huntington and Parkinson populations. Additionally, regarding the genes that respondents are interested in using for genetic studies, the following trend can be observed from 96 answers: 18 (19%) ApoE, 14 (15%) PSEN1, 13 (14%) PSEN2, 12 (13%) APP, 9 (9%) MAPT, 8 (8%) C9orf72, 8 (8%) PGRN, 6 (6%) TARDBP, 4 (4%) TREM2, and 4 (4%) GWAS (Figure 3D). The principal techniques to perform genetic studies currently used and of interest are real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), used to detect specific polymorphisms or mutations, Sanger Sequencing, and Next Generation Sequencing (NGS).

3.4. Experience to date

One of the main questions regarding the use of biomarkers was related to the number of years that clinicians and researchers from the different LAC countries have been using the different types of biomarkers. Brazil was the country with the most years per respondent working in neuroimaging, followed by Ecuador, Uruguay, Peru, and Chile. We found the same pattern for CSF biomarkers, whereby Brazil, followed by Peru, shows prominent results with more years of experience than other countries. In peripheral biomarkers, which is the newest field of study, Brazil leads the results of years of experience in these techniques followed by Chile. Finally, in genetics studies, Colombia was at the top followed by Brazil with prominent years of experience and close to Chile (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Years of experience in the use of biomarkers of respondents by country and per biomarkers.

3.5. Access to unique populations in LAC

Regarding neuroimaging, Argentinian reported having access to populations with familial AD and Down’s syndrome, whereas Brazilian respondents reported having access to different populations with diagnoses of cognitive impairment and dementia, specifically Caucasian, black, and admixed populations. Chilean respondents reported having access to dementia and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) population, and Colombian respondents indicated access to populations with genetic AD, FTD, PD, Huntington’s disease, and vascular hereditary dementia CADASIL (Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy) type. Costa Rican respondents reported having access to mixed populations, Dominican respondents reported having access to the general population, and Ecuadorian respondents reported having access to cognitive impairment, dementia, and ethnic populations. Finally, Peruvian respondents indicated access to the general population, illiterate adults and to ethnic groups such as the Quechua and Aymara.

Regarding the possibility of performing neuroimaging studies with such populations in LAC, 60.5% of the respondents confirmed that this option is available whereas 39.5% responded that this is not available for them. Regarding CSF biomarkers in LAC, in Argentina, respondents reported having access to samples of Down’s syndrome. Brazil indicated access to samples from different ethnic groups like Caucasian, black, and admixed samples. Colombia reported access to CSF samples in families with autosomal dominant AD, FTD, and vascular hereditary dementia CADASIL Type, whereas Ecuador has access to samples of the indigenous population.

Regarding the possibility of performing CSF studies in such populations, 57.4% of the respondents confirmed they would be able to access them for research purposes. Regarding biofluids, Brazil has access to peripheral samples from different ethnic groups such as caucasian, black, and admixed individuals. In Chile, there is access to samples of elderly members of the GERO cohort [73]. In Colombia, there is access to samples of families with autosomal dominant AD and vascular hereditary dementia CADASIL Type. With respect to the possibility of performing peripheral fluid biomarkers studies in different populations in the future, 71.7% of the respondents of the survey answered that they would be able to access them while 28.3% would not.

Regarding genetic studies, Argentina indicated that the genetic samples obtained come from family forms of different dementia populations, including Down syndrome. In Brazil access to samples from Afro-Brazilian and Asian-Brazilian people is available. In Chile, a regional cohort study of aged individuals (GERO) is currently collecting samples [73]. Colombia has the widest access via their genetic clusters including AD, FTD, PD, Huntington disease and vascular hereditary dementia CADASIL-Type. Peru will now start collecting genetic samples from patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild AD in Quechua and Aymara populations. In relation to the possible access to genetic samples to perform future studies, 59% of respondents of the survey could have access to genetic samples from different populations in their country. In contrast, 41% of the respondents indicate that obtaining samples from a diverse population is not possible.

3.6. Barriers to the use of Biomarker

3.6.1. Barriers to perform biomarkers studies in LAC

The identified barriers from this survey were: funding, infrastructure and knowledge (as technical personnel and human resources). The main barrier to the use of the analyzed biomarkers is the lack of funding to perform clinical and research studies, whereas the second leading barrier identified was the infrastructure. Of the total of responses from respondents currently using or interested in using neuroimaging, CSF, peripheral fluid and genetic studies, around 73% of the former and 60% of the latter group reported that funding is a main barrier. The second more prominent barrier was knowledge, reporting 16% of the answers of the respondents currently using these biomarkers and 19% of the answers of the respondents interested. With regard to the infrastructure as a barrier, 11% of the answers corresponded to respondents using these biomarkers and 21% of to those interested (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Barriers to perform biomarkers studies in LAC.

(A) Barriers to perform biomarkers studies. (B) Possible barriers to perform biomarkers studies for uninterested respondents.

3.6.2. Attitudes towards dementia biomarkers in LAC

Finally, in the survey we asked the respondents the reasons why they are not working with biomarkers, or why they are not interested in using them. Respondents not working (45%) or uninterested (39%) in using neuroimaging, CSF, peripheral fluid and genetic biomarkers reported that lack of funding was the main barrier. The second barrier was the infrastructure, reported by 31% of the respondents currently not using biomarkers and 28% of those uninterested. With regard to knowledge as a barrier, 14% of the answers corresponded to the participants not using these biomarkers and 17% to those uninterested. Among the options in the survey regarding possible reasons for not being interested in performing biomarker studies, only 4 respondents reported they consider these are “not necessary” or “ unreliable”.

3.7. Publications of Latin American respondents

The respondents of the survey reported published papers about biomarkers studies developed in LAC populations from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay. Brazil reported 72 publications, most of them related to neuroimaging and peripheral fluids, followed by Colombia reporting 29 publications related to genetics studies published in high impact factor journals. On the other hand, Peru and Uruguay reported only one publication each (Table 1).

Table 1. Publications of Latin American respondents.

ƍ:Neuroimaging, Ƿ:CSF, □:Peripheral Fluid, ƺ:Genetic, ⌠:Neuroimaging and CSF, ⎧:Neuroimaging and Peripheral fluid, ⎩:Neuroimaging and Genetic, ⎿:Neuroimaging, CSF and Genetic, ©:Neuroimaging, Peripheral fluid and Genetic and ⟨:Peripheral Fluid and Genetic, Þ: CSF and Genetics, Å: Neuroimaging, CSF and Peripheral Fluids, Æ: Neuroimaging, CSF, Peripheral Fluids and Genetics.

| Country | Biomarker | Mean impact factor |

№ of papers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | ƍ(1) Ƿ(2) ƺ(3) Ꝑ(3) ꝏ(1) Ꝙ(3) | 4.805 | 13 |

| Brazil | ƍ(26) Ƿ(7) Ꜵ(22) ƺ(8) ꝭ(2) ꝏ(1) Ꝍ(5) Þ(1) | 3.749 | 72 |

| Chile | ƍ(2) Ꜵ(3) ƺ(1) ꝭ(1) | 3.996 | 7 |

| Colombia | ƺ(11) ꝏ(11) Ꝩ(1) Ꝍ(1) Å(1) Æ(3) | 14.962 | 28 |

| Mexico | Ꜵ(4) ƺ(3) ꝏ(2) ƍ(2) | 3.575 | 11 |

| Peru | ƺ(1) | 4.347 | 1 |

| Uruguay | ƍ (1) | 3.552 | 1 |

Note: ƍ:Neuroimaging, Ƿ:CSF, Ꜵ:Peripheral Fluid, ƺ:Genetic, Ꝑ:Neuroimaging and CSF, ꝭ:Neuroimaging and Peripheral fluid, ꝏ:Neuroimaging and Genetic, Ꝙ:Neuroimaging, CSF and Genetic, Ꝩ:Neuroimaging, Peripheral fluid and Genetic, Ꝍ:Peripheral Fluid and Genetic, Þ: CSF and Genetics, Å: Neuroimaging, CSF and Peripheral Fluids, Æ: Neuroimaging, CSF, Peripheral Fluids and Genetics.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Limited knowledge and implementation barriers for dementia biomarkers in LAC countries remain serious challenges. The main motivation of this survey was to collect updated information to provide a representative and inclusive overview of the reality and implications of the use of the different types of biomarkers in LAC.

4.1. Biomarkers use and interest

Neuroimaging is the most widely used biomarker by the respondents of our survey. Neuroimaging biomarkers that hold well-known clinical value, such as MRI and FDG-PET, are the most frequently used whereas the others (DTI, PET, fMRI, SPECT) are used though to a smaller extent and are more scattered among LAC countries. It is worth noting that genetic biomarkers were the second class most frequently used after neuroimaging. A reason for this may be linked to the presence of genetic clusters of mutations linked to dementia subtypes which have been and continue to be identified in the region [74].

It is also important to emphasize that respondents have identified peripheral biomarkers as the class that they are most interested to use in the future, followed by CSF and genetic studies. This coincides with the increasing use of CSF and peripheral biomarkers in various centers in LAC.

4.2. Biomarker purposes

Relative to other biomarkers classes, Neuroimaging seems to be the method most widely used in clinical practice. Even respondents who do not use it are interested and see this as a useful tool supporting clinical and research settings. This result may be explained by the growing body of evidence supporting the use of neuroimaging biomarkers throughout the dementia continuum (MCI [75]) and care pathway including diagnosis [76], progression [77], and predicting treatment response [78].

Neither peripheral nor genetic biomarkers are currently reported as being used for clinical purposes. A barrier to the clinical implementation of peripheral biomarkers might be the lack of adequate centers and standardized protocols for sample processing. The application of a peripheral biomarker in clinical practice requires significant research and validation [79] as well as a continuous evaluation process.

4.3. Barriers to Biomarker use in LAC

Barriers to the implementation of biomarkers have been previously described [3, 80]. Importantly, the respondents of our survey provided crucial information related to the main barriers that they have been or they would be presented with to perform studies with biomarkers in LAC (Figure 6A). The main challenges and barriers reported in this study were funding, technical personnel, and infrastructure. However, those barriers were not equally distributed across LAC, with some countries such as Brazil or Argentina, with strong research on biomarkers while others, including Costa Rica or Uruguay, have little to no research in the clinical use of biomarkers. In this context, the most accessible and cost-effective biomarkers, such as fluid biomarkers, represent a good opportunity to enhance diagnosis and dementia research in the region.

4.4. Funding for Biomarkers

Our study has identified that funding represents one of the main challenges in the implementation and use of biomarkers. Funding is limited and mainly granted by public agencies. It should be noted that even most of the respondents working in private centers have mainly public funding to carry out their research. Interestingly, biomarkers, which are being used mainly for research purposes (CSF, peripheral and genetic), are those attracting most funding in LAC (Figures 2B and 2C). It is worth noting that these are mainly located in advanced centers where the expertise is hosted. This indicates a centralization of knowledge and technological resources within each country and across the region. Nevertheless, it indicates a promising landscape for international collaborations and funding which would allow LAC to continue developing hubs for biomarker research, validation, and training.

Respondents with an interest in biomarkers who are currently not incorporating them in their practice have reported the lack of funding as one of their limitations. It will be worth exploring where these barriers lie as overcoming them would provide opportunities to set up facilities and increase the number of qualified professionals across the region. Improving grant proposals via strong regional and international collaborations would be a key strategy to fill these gaps. This survey provides key evidence that can inform such joint efforts. Furthermore, support is also needed to enhance capacity building strategies via training programs offered by countries with strong infrastructure (i.e., Biomarker Hubs).

4.5. Experience

As previously discussed by Parra et al. [2], experience in the use of biomarkers is concentrated in a few LAC countries. Such experiences often map onto the population these countries have access to. For instance, Colombia reported experience in genetic biomarkers and access to large genetic clusters of families carrying rare single-gene mutations for various types of dementia (Table 1). On the other hand, countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador, Uruguay, Peru, and Chile have a long-standing experience in the use of biomarkers with heterogeneous populations (Table 1). We envisage that these countries can become hubs for biomarker research and training in LAC which could lead to partnerships across countries for data exchange and cooperative research.

4.6. Infrastructure

In our study, several respondents reported the lack of state-of-the-art laboratories to perform biofluid or genetic biomarkers analysis as a limitation, which is seemingly linked to the limited funding opportunities of the region. This pattern seems to be shared across respondents who are currently using and not using biomarkers. Moreover, it was reported that multiple research groups currently working on biomarkers have the need to outsource the genetic analysis of their samples to foreign laboratories which may increase the cost of the use of biomarkers in research and clinical settings.

On another point, state of the art neuroimaging equipment is available in highly specialized health institutions, most of them localized in capital cities, limiting the access to the general population. Less specialized health institutions which can be found in peripheral centers are regularly equipped with low to middle-resolution scanners.

4.7. Strengths and limitations of this study

LAC-CD is the most extensive regional network focused on neurodegenerative diseases. Although we tried to be as inclusive as possible by involving its entire membership, this attempt certainly yielded a biased sample. Nevertheless, this caveat seems to characterize different works led by a consortium and is one widely seen in the relevant literature. A significant number of members from LAC-CD are currently undertaking or have previously undertaken biomarkers research, and many of them work as both clinicians and researchers. Given the diversity, expertise, and representativeness of LAC-CD members that contributed to this survey, we feel confident to uphold the validity of the results here reported.

Another important limitation is that it was not possible to compare public and private centers. Only 11 respondents out of the total 48 (23%) are working in private centers. This small proportion did not allow to perform further analysis to unveil differences across sectors. For instance, only 2 respondents linked to private centers are currently working with CSF biomarkers instead of 14 respondents belonging to public centers.

4.8. Why is it important to review the status quo in LAC?

In the past few years, significant efforts have led to the creation of several Latin-American networks aimed at promoting clinical and research activities on dementia [60]. One of the main challenges has been to harmonize procedures, ensuring that evidence-based protocols are available to LAC countries [2, 3]. To tackle the local challenges regarding dementia research, multinational networks aimed at identifying the unique genetic, social, and economic factors driving the presentation of FTD and AD have been set up [61]. Regarding biomarkers, LAC research has focused on developing multicentric studies that integrate several biomarkers to provide a better classification of neurodegenerative diseases, evaluating the multi-dimensional data using artificial intelligence (AI) approaches such as machine learning [81]. The LAC-CD Biomarker Framework aims to support the use, development and validation of affordable biomarkers in the region with a special emphasis on peripheral biomarkers. Considering the role that some countries in the region are playing in the validation of the A/T/N biomarker framework, development of new drugs for the secondary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease together with the distinctiveness of risk and protective factors for dementia found in the region, we feel compelled to further encourage the implementation of the LAC-CD Biomarker Framework. This study provides the knowledge base that will inform the implementation of such a Framework and ensuing initiatives.

4.9. Biomarker Opportunities in LAC

The impact of genetic ancestry and admixture on dementia prevalence and phenotypes in LAC has been widely acknowledged. LAC countries are highly diverse, so investigating these factors will provide unique insights to better understand the interplay of social determinants of health, demographic variables, biomarkers of neurodegenerative pathologies, and risk of dementia. Regarding genetic features of LAC populations, we have highlighted the opportunities that such populations host for the advancement of biomarker research and drug development programs positioning LAC as a key example (Neuroscience Group of Antioquia, Instituto Neurológico FLENI, RedLat, PISA at University of Sao Paulo).

One key barrier extensively acknowledged in scientific literature is the lack of publications of LAC studies in high impact journals. However, this trend is rapidly changing with emerging networking initiatives [2, 3, 60]. As the results from our survey, we have identified countries currently making significant contributions to knowledge building (Table 1) are those where biomarker expertise and resources are mostly gathered. We have suggested that these realities can change if such centers act as hubs to support capacity building and collaboration in the region and beyond. This situation also poses a great opportunity to form partnerships and create the space needed for knowledge exchange and capacity building in the LAC region.

5. Final Remarks

LAC hosts unprecedented opportunities to advance biomarker development and validation globally. Our survey suggests that the region holds positive attitudes to embark on such developments. Respondents of this survey who are not currently using biomarkers reported their eagerness to incorporate “all biomarkers that they could work with”. Previous reports have characterized regional realities and provided action plans to tackle them. Here, we specifically aim to contribute to the biomarkers framework proposed by the LAC-CD’s Knowledge to Action Plan which includes: i) Validation and implementation of harmonized protocols such as the A/T/N framework in LAC hubs. This survey provided evidence of centers that act as such hubs, ii) Strengthening partnership with the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute of Health/National Institute on Aging (NIH/NIA) to improve regional grant proposals, expand funding opportunities and increase collaborative work among LAC-CD members. This survey has contributed evidence on funding barriers and eagerness of respondents to engage in collaborative work. We have initiated discussions with leaders of the Neuroimaging and Biofluid Based Biomarkers Professional Interest Areas of ISTAART to set up Regional Biomarker Networks and Collaborative Groups, iii) Introduction of complementary affordable biomarkers based on new assessments depending on the infrastructure available in each LAC country included in this study. The survey contributed evidence on laboratories where Biofluid Based Biomarkers could be swiftly introduced or enhanced. We will invite these center and groups to join the LAC Biomarker Network to expand funding opportunities, iv) To improve understanding of the interplay of the genetic mechanisms, clinical phenotypes, and severity of neurodegenerative diseases. The survey provided valuable information that complements previous efforts from LAC-CD [3] and together they pave the way for future work on the above factors. There are ongoing initiatives that will contribute and further benefit from such work (RedLat, NIH-R01 consortia grants of biomarkers/epigenetics/linguistic, and LAC funding of new peripheral biomarkers), v) To promote efforts via capacity building, implementation science and translational research to support regional dementia plans, enhance the regional health systems’ infrastructure related to brain health, and facilitate future agreements with governments to increase the budget for dementia prevention, care and research. We are confident that new collaborative initiatives currently considering the LAC region will soon materialize.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

1. Systematic review:

An online survey was created to identify the current use and accessibility of biomarkers for the diagnosis of dementias in Latin American Countries (LAC). This survey was answered by 48 participants from 10 LAC countries.

2. Interpretation:

The results provide information about a prominent potential in LAC to perform research on dementia biomarkers, as respondents of the survey showed high interest. The main barriers identified to use biomarkers correspond to funding, infrastructure, and lack of personnel training.

3. Future directions:

A main action plan was suggested that addresses the recommendations towards a biomarker framework recently proposed by LAC regional experts.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sandro Casavilca-Zambrano, Gabriel Espinoza Coronel, Jose Carlos Huilca Flores, Pablo Martinez-Lage, Dongjun Yoo, Fernando Lara Roquette who participated in answering the survey. CDA is partially supported by 2018-AARG-591107, ANID/FONDEF ID20I10152, ANID/FONDECYT 1210622 and ANID/PIA/ANILLOS ACT210096. AI is supported by grants from CONICET; ANID/FONDECYT Regular (1210195 and 1210176); ANID/FONDAP (15150012); FONCYT-PICT 2017-1820; Takeda CW2680521; Sistema General de Regalías (BPIN2018000100059), Universidad del Valle (CI 5316); Alzheimer’s Association GBHI ALZ UK-20-639295; and the MULTI-PARTNER CONSORTIUM TO EXPAND DEMENTIA RESEARCH IN LATIN AMERICA [ReDLat, supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Aging (R01 AG057234), Alzheimer’s Association (SG-20-725707), Rainwater Charitable foundation-Tau Consortium, and Global Brain Health Institute)]. MIB is supported by ANID/Fondecyt Regular (1190958), ANID/FONDEF-IDEA: (ID20I10252 and (ID19I10302) and ANID/Fondequip 2021. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of these Institutions. LCS and PC hold a senior researcher grant (bolsa de produtividade em pesquisa) from CNPq, Brazil. STF is funded by the Brazilian agencies Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) and National Institute for Translational Neuroscience. HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2018-02532), the European Research Council (#681712), Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG-720931), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (#201809-2016862), the AD Strategic Fund and the Alzheimer's Association (#ADSF-21-831376-C, #ADSF-21-831381-C and #ADSF-21-831377-C), the Olav Thon Foundation, the Erling-Persson Family Foundation, Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor, Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2019-0228), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 860197 (MIRIADE), European Union Joint Program for Neurodegenerative Disorders (JPND2021-00694), and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL. FH was supported by grants from ANID-Subdirección de Capital Humano/Doctorado Nacional/2021- 21211349, Chile.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

HZ has served at scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Abbvie, Alector, Annexon, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, CogRx, Denali, Eisai, Nervgen, Novo Nordisk, Pinteon Therapeutics, Red Abbey Labs, Passage Bio, Roche, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Triplet Therapeutics, and Wave has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Cellectricon, Fujirebio, Alzecure, Biogen, and Roche, and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program (outside submitted work).

References

- [1].Baez S, Ibanez A. Dementia in Latin America: An Emergent Silent Tsunami. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Parra MA, Baez S, Allegri R, Nitrini R, Lopera F, Slachevsky A, et al. Dementia in Latin America: Assessing the present and envisioning the future. Neurology. 2018;90:222–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Parra MA, Baez S, Sedeno L, Gonzalez Campo C, Santamaria-Garcia H, Aprahamian I, et al. Dementia in Latin America: Paving the way toward a regional action plan. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:295–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nitrini R, Barbosa MT, Dozzi Brucki SM, Yassuda MS, Caramelli P. Current trends and challenges on dementia management and research in Latin America. J Glob Health. 2020;10:010362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Manes F. The huge burden of dementia in Latin America. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:63–75 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nitrini R, Bottino CM, Albala C, Custodio Capunay NS, Ketzoian C, Llibre Rodriguez JJ, et al. Prevalence of dementia in Latin America: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:622–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wolters FJ, Chibnik LB, Waziry R, Anderson R, Berr C, Beiser A, et al. Twenty-seven-year time trends in dementia incidence in Europe and the United States: The Alzheimer Cohorts Consortium. Neurology. 2020;95:e519–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Prince MWA GM, Ali GC, Wu Y-T, Prina M, ADI World alzheimer report 2015. The global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, costs and trends. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bank W. List of economies. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jack CR Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:734–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].El Kadmiri N, Said N, Slassi I, El Moutawakil B, Nadifi S. Biomarkers for Alzheimer Disease: Classical and Novel Candidates’ Review. Neuroscience. 2018;370:181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Blennow K, Hampel H. CSF markers for incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:605–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Burger nee Buch K, Padberg F, Nolde T, Teipel SJ, Stubner S, Haslinger A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau protein shows a better discrimination in young old (<70 years) than in old old patients with Alzheimer’s disease compared with controls. Neurosci Lett. 1999;277:21–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hampel H, Buerger K, Zinkowski R, Teipel SJ, Goernitz A, Andreasen N, et al. Measurement of phosphorylated tau epitopes in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer disease: a comparative cerebrospinal fluid study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hampel H, Burger K, Teipel SJ, Bokde AL, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Core candidate neurochemical and imaging biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Hansson O, Andreasen N, Parnetti L, Jonsson M, et al. CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2009;302:385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bobinski M, de Leon MJ, Wegiel J, Desanti S, Convit A, Saint Louis LA, et al. The histological validation of post mortem magnetic resonance imaging-determined hippocampal volume in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2000;95:721–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zarow C, Vinters HV, Ellis WG, Weiner MW, Mungas D, White L, et al. Correlates of hippocampal neuron number in Alzheimer’s disease and ischemic vascular dementia. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:896–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Silverman DH, Small GW, Chang CY, Lu CS, Kung De Aburto MA, Chen W, et al. Positron emission tomography in evaluation of dementia: Regional brain metabolism and long-term outcome. JAMA. 2001;286:2120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].de Leon MJ, Convit A, Wolf OT, Tarshish CY, DeSanti S, Rusinek H, et al. Prediction of cognitive decline in normal elderly subjects with 2-[(18)F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose/poitron-emission tomography (FDG/PET). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10966–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Drzezga A, Lautenschlager N, Siebner H, Riemenschneider M, Willoch F, Minoshima S, et al. Cerebral metabolic changes accompanying conversion of mild cognitive impairment into Alzheimer’s disease: a PET follow-up study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:1104–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Koychev I, Gunn RN, Firouzian A, Lawson J, Zamboni G, Ridha B, et al. PET Tau and Amyloid-beta Burden in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease: Divergent Relationship with Age, Cognition, and Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60:283–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ossenkoppele R, Smith R, Ohlsson T, Strandberg O, Mattsson N, Insel PS, et al. Associations between tau, Abeta, and cortical thickness with cognition in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2019;92:e601–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Aschenbrenner AJ, Gordon BA, Benzinger TLS, Morris JC, Hassenstab JJ. Influence of tau PET, amyloid PET, and hippocampal volume on cognition in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2018;91:e859–e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jack CR, Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Feldman HH, Frisoni GB, et al. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016;87:539–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Irizarry MC. Biomarkers of Alzheimer disease in plasma. NeuroRx. 2004;1:226–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Thambisetty M, Lovestone S. Blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: challenging but feasible. Biomark Med. 2010;4:65–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lista S, Faltraco F, Prvulovic D, Hampel H. Blood and plasma-based proteomic biomarker research in Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;101-102:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zetterberg H, Schott JM. Blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Acta Neurol Scand. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Moving fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease from research tools to routine clinical diagnostics. Mol Neurodegener. 2021;16:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].van der Flier WM, Scheltens P. Epidemiology and risk factors of dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76 Suppl 5:v2–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Goate A. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid beta-protein precursor gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cruts M, Hendriks L, Van Broeckhoven C. The presenilin genes: a new gene family involved in Alzheimer disease pathology. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5 Spec No:1449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Levy-Lahad E, Wasco W, Poorkaj P, Romano DM, Oshima J, Pettingell WH, et al. Candidate gene for the chromosome 1 familial Alzheimer’s disease locus. Science. 1995;269:973–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72:245–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006;442:916–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, Nemens E, Garruto RM, Anderson L, et al. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:815–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, George-Hyslop PH, Pericak-Vance MA, Joo SH, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1467–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Duran-Aniotz C, Orellana P, Leon Rodriguez T, Henriquez F, Cabello V, Aguirre-Pinto MF, et al. Systematic Review: Genetic, Neuroimaging, and Fluids Biomarkers for Frontotemporal Dementia Across Latin America Countries. Front Neurol. 2021;12:663407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sexton C, Snyder HM, Chandrasekaran L, Worley S, Carrillo MC. Expanding Representation of Low and Middle Income Countries in Global Dementia Research: Commentary From the Alzheimer’s Association. Front Neurol. 2021;12:633777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tutor CA, Frias L. Development of PET in Latin America Experience of the first PET-Cyclotron Center. World Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2002;1:219. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Allegri RF, Chrem Mendez P, Calandri I, Cohen G, Martin ME, Russo MJ, et al. Prognostic value of ATN Alzheimer biomarkers: 60-month follow-up results from the Argentine Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12:e12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Allegri RF, Chrem Mendez P, Russo MJ, Cohen G, Calandri I, Campos J, et al. Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in mild cognitive impairment: Experience in a memory clinic from Latin America. Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2021;36:201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Cecchini MA, Yassuda MS, Squarzoni P, Coutinho AM, de Paula Faria D, Duran FLS, et al. Deficits in short-term memory binding are detectable in individuals with brain amyloid deposition in the absence of overt neurodegeneration in the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Brain Cogn. 2021;152:105749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Damian A, Portugal F, Niell N, Quagliata A, Bayardo K, Alonso O, et al. Clinical Impact of PET With (18)F-FDG and (11)C-PIB in Patients With Dementia in a Developing Country. Front Neurol. 2021;12:630958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Faria DP, Duran FL, Squarzoni P, Coutinho AM, Garcez AT, Santos PP, et al. Topography of 11C-Pittsburgh compound B uptake in Alzheimer’s disease: a voxel-based investigation of cortical and white matter regions. Braz J Psychiatry. 2019;41:101–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Coutinho AM, Busatto GF, de Gobbi Porto FH, de Paula Faria D, Ono CR, Garcez AT, et al. Brain PET amyloid and neurodegeneration biomarkers in the context of the 2018 NIA-AA research framework: an individual approach exploring clinical-biomarker mismatches and sociodemographic parameters. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:2666–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].de Souza GS, Andrade MA, Borelli WV, Schilling LP, Matushita CS, Portuguez MW, et al. Amyloid-beta PET Classification on Cognitive Aging Stages Using the Centiloid Scale. Mol Imaging Biol. 2022;24:394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hansen EO, Dias NS, Burgos ICB, Costa MV, Carvalho AT, Teixeira AL, et al. Millipore xMap(R) Luminex (HATMAG-68K): An Accurate and Cost-Effective Method for Evaluating Alzheimer’s Biomarkers in Cerebrospinal Fluid. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:716686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Madeira C, Lourenco MV, Vargas-Lopes C, Suemoto CK, Brandao CO, Reis T, et al. d-serine levels in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for novel biomarker development. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lourenco MV, Ribeiro FC, Sudo FK, Drummond C, Assuncao N, Vanderborght B, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid irisin correlates with amyloid-beta, BDNF, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12:e12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lourenco MV, Ribeiro FC, Santos LE, Beckman D, Melo HM, Sudo FK, et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurotransmitters, Cytokines, and Chemokines in Alzheimer’s and Lewy Body Diseases. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82:1067–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Madeira C, Vargas-Lopes C, Brandao CO, Reis T, Laks J, Panizzutti R, et al. Elevated Glutamate and Glutamine Levels in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients With Probable Alzheimer’s Disease and Depression. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Reiman EM, Quiroz YT, Fleisher AS, Chen K, Velez-Pardo C, Jimenez-Del-Rio M, et al. Brain imaging and fluid biomarker analysis in young adults at genetic risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in the presenilin 1 E280A kindred: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:1048–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hampel H, O’Bryant SE, Molinuevo JL, Zetterberg H, Masters CL, Lista S, et al. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer disease: mapping the road to the clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:639–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Ibanez A, Parra MA, Butler C, Latin A, the Caribbean Consortium on D. The Latin America and the Caribbean Consortium on Dementia (LAC-CD): From Networking to Research to Implementation Science. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82:S379–S94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ibanez A, Yokoyama JS, Possin KL, Matallana D, Lopera F, Nitrini R, et al. The Multi-Partner Consortium to Expand Dementia Research in Latin America (ReDLat): Driving Multicentric Research and Implementation Science. Front Neurol. 2021;12:631722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Reyes-Pablo AE, Campa-Cordoba BB, Luna-Viramontes NI, Ontiveros-Torres MA, Villanueva-Fierro I, Bravo-Munoz M, et al. National Dementia BioBank: A Strategy for the Diagnosis and Study of Neurodegenerative Diseases in Mexico. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76:853–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zetterberg H, Bendlin BB. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease-preparing for a new era of disease-modifying therapies. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:296–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Thijssen EH, La Joie R, Wolf A, Strom A, Wang P, Iaccarino L, et al. Diagnostic value of plasma phosphorylated tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Nat Med. 2020;26:387–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Khan TK, Alkon DL. Peripheral biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44:729–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ogonowski N, Salcidua S, Leon T, Chamorro-Veloso N, Valls C, Avalos C, et al. Systematic Review: microRNAs as Potential Biomarkers in Mild Cognitive Impairment Diagnosis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:807764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Alawode DOT, Heslegrave AJ, Ashton NJ, Karikari TK, Simren J, Montoliu-Gaya L, et al. Transitioning from cerebrospinal fluid to blood tests to facilitate diagnosis and disease monitoring in Alzheimer’s disease. J Intern Med. 2021;290:583–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wojsiat J, Laskowska-Kaszub K, Mietelska-Porowska A, Wojda U. Search for Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in blood cells: hypotheses-driven approach. Biomark Med. 2017;11:917–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].O’Bryant SE, Mielke MM, Rissman RA, Lista S, Vanderstichele H, Zetterberg H, et al. Blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer disease: Current state of the science and a novel collaborative paradigm for advancing from discovery to clinic. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:45–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Teunissen CE, Verberk IMW, Thijssen EH, Vermunt L, Hansson O, Zetterberg H, et al. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: towards clinical implementation. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:66–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Ashton NJ, Kiddle SJ, Graf J, Ward M, Baird AL, Hye A, et al. Blood protein predictors of brain amyloid for enrichment in clinical trials? Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2015;1:48–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Cummings J, Feldman HH, Scheltens P. The “rights” of precision drug development for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Slachevsky A, Zitko P, Martinez-Pernia D, Forno G, Court FA, Lillo P, et al. GERO Cohort Protocol, Chile, 2017-2022: Community-based Cohort of Functional Decline in Subjective Cognitive Complaint elderly. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Magaki S, Yong WH, Khanlou N, Tung S, Vinters HV. Comorbidity in dementia: update of an ongoing autopsy study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1722–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Gullett JM, Albizu A, Fang R, Loewenstein DA, Duara R, Rosselli M, et al. Baseline Neuroimaging Predicts Decline to Dementia From Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:758298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Shiino A, Shirakashi Y, Ishida M, Tanigaki K, Japanese Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Machine learning of brain structural biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis, prediction of disease progression, and amyloid beta deposition in the Japanese population. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2021;13:e12246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Zhou Y, Song Z, Han X, Li H, Tang X. Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease Progression Based on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021;12:4209–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Di Tella S, Cabinio M, Isernia S, Blasi V, Rossetto F, Saibene FL, et al. Neuroimaging Biomarkers Predicting the Efficacy of Multimodal Rehabilitative Intervention in the Alzheimer’s Dementia Continuum Pathology. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:735508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Menon MC, Murphy B, Heeger PS. Moving Biomarkers toward Clinical Implementation in Kidney Transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:735–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Teunissen CE, Otto M, Engelborghs S, Herukka SK, Lehmann S, Lewczuk P, et al. White paper by the Society for CSF Analysis and Clinical Neurochemistry: Overcoming barriers in biomarker development and clinical translation. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Bachli MB, Sedeno L, Ochab JK, Piguet O, Kumfor F, Reyes P, et al. Evaluating the reliability of neurocognitive biomarkers of neurodegenerative diseases across countries: A machine learning approach. Neuroimage. 2020;208:116456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.