Graphical abstract

Keywords: Corn bran, Insoluble dietary fiber, Ultrasonic-microwave treatment, Characterization

Highlights

-

•

Insoluble dietary fibre (IDF) was efficiently modified by ultrasound-microwave (U-M).

-

•

U-M reduced the crystallinity of IDF and exposed more hydroxyl groups.

-

•

U-M enhanced the in vitro hypoglycaemic activity of IDF.

-

•

U-M improved the growth-promoting and adhesion properties of IDF to probiotics.

Abstract

A comprehensive investigation aimed to access the impacts of ultrasonic, microwave, and ultrasonic-microwave synergistic modification on the physicochemical properties, microstructure, and functional properties of corn bran insoluble dietary fiber (CBIDF). Our findings revealed that CBIDF presented a porous structure with loose folds, and the particle size and relative crystallinity were slightly decreased after modification. The CBIDF, which was modified by ultrasound-microwave synergistic treatment, exhibited remarkable benefits in terms of its adsorption capacity, and cholate adsorption capacity. Furthermore, the modification improved the in vitro hypoglycemic activity of the CBIDF by enhancing glucose absorption, retarding the starch hydrolysis, and facilitating the diffusion of glucose solution. The findings from the in vitro probiotic activity indicate that ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification also enhances the growth-promoting ability and adsorbability of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium longum. Additionally, the level of soluble dietary fiber was found to be positively correlated with CBIDF adsorbability, while the crystallinity of CBIDF showed a negative correlation with α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition activity, as well as water-holding capacity, and oil-holding capacity.

1. Introduction

Dietary fiber (DF) is an analog of carbohydrates, typically viewed as having low nutritional worth. However, it significantly benefits human physiological functions, and greatly reduces the risk of hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other ailments [1], [2], [3]. Numerous studies have confirmed that DF can improve gastrointestinal digestion and absorption of nutrients, and improve blood sugar and lipid metabolism. DF can also be used to treat and intervene in various gastrointestinal diseases. Based on their solubility in water, DF can be roughly classified as soluble dietary fiber (SDF) and insoluble dietary fiber (IDF). IDF comprises cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose components, featuring numerous active groups on its surface, that could adsorb organic substances, including lipids and sugars in the intestine. Meanwhile, IDF could also remove toxic substances in the body and promote metabolism [4], [5]. In addition, IDF can increase satiety in the body and assist individuals in controlling their diet and maintaining good health.

FAO data showed global corn production of 1.21 billion tons in 2021. Corn is regarded as one of the world's most important and productive cereals, with significant economic and social value [6]. Despite being a major by-product of corn processing, corn bran has not attracted sufficient attention due to its low solubility in water and unappetizing taste [7]. Typically utilized as a feed ingredient. Studies have found that cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin make up the majority of corn bran. The fiber content of corn bran is about 70 %, making it a good source of dietary fiber [8], [9]. Its distinctive polysaccharide composition and structural characteristics distinguish corn bran dietary fiber from other sources. The hemicellulose content of the corn bran is approximately 68 %, with a high degree of branch chain and low lignin content [10]. Arabinoxylan, the main hemicellulose dietary fiber type in corn bran, constitutes up to 70 % of its hemicellulose, and it has high functional properties and probiotic activity [11], [12]. To enhance the value of corn bran and meet the requirements of IDF as a healthy food ingredient, modifications to IDF are necessary to reduce its adverse effects on food color, texture, and flavor [13].

Research has shown that both ultrasonic and microwave can be used as an important modification method for DF. Ultrasonic can cause severe vibration of polar molecules in the material to generate a cavitation effect, destroy the chemical bonds of polysaccharides, change the physicochemical properties and hydrophilicity of polysaccharide surface, and improve their function [14]. Microwaves can reinforce the destruction of cell walls or membranes, accelerate heat transfer, and transfer target compounds. In the native plant cell wall matrix, microwaves may trigger a rupture of the cell wall matrix, which is more easily utilized by gut bacteria to provide nutrients for the growth of gut microbes [15]. The ultrasonic and microwave synergy fully combines the high-energy acts of microwave and the cavitation action of ultrasound, thus realizing the full extraction or modification of target components under normal pressure. For instance, Huang et al. (2018) discovered that ultrasonic treatment significantly enhanced the in vitro hypoglycemic effect of IDF in garlic straw, the inhibition rate of α-amylase activity increased by 18.2 %, and the glucose absorption increased by 8.9 % (P < 0.05) [16]. Microwave modification can improve the fermentability of IDF, promote the growth of beneficial bacteria, and reduce the number of harmful bacteria [17], [18]. The synergistic effect of ultrasonic-microwave has shown promising results in the preparation and improvement of physicochemical properties of SDF [19], [20]. However, there is a dearth of research on IDF. This study presents the introduction of ultrasonic-microwave synergistic modification for the modification of CBIDF. It is suggested that this synergistic effect causes the breakdown of the dense polymer structure of IDF, thus exposing more functional groups such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups. Additionally, it enhances the functional properties of IDF from corn bran.

This study aimed to assess the impact of ultrasonic, microwave, and ultrasonic-microwave synergistic modification on CBIDF's physicochemical properties, microstructure, in vitro hypoglycemic activity, and probiotic activity. The correlation between these indicators was analyzed using clustered heat maps and correlation heat maps, yielding fresh insights into enhancing the functional properties of CBIDF. This research offers a theoretical basis for the profound processing of corn bran.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Corn bran was obtained from Jingliang Co., Ltd. (Suihua, China). Alkali protease (2×105 U/g), glucoamylase (1.5×105 U/g), and α-amylase (2×105 U/g) from Novozymes Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). α-glucosidase (50 U/mg), and α-amylase (derived from pig pancreas, 50 U/mg) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Trading Co., LTD. (Shanghai, China), glucose content detection kit: Solaibao Co., LTD. (Beijing, China). Lactobacillus acidophilus (BNCC336636) and Bifidobacterium longum (BNCC187962): Beina Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.2. Preparation of CBIDF

CBIDF was prepared using an enzymatic method [21]. The raw material was mixed with water at 1:20 (g/mL). The pH was adjusted to 6.5 using HCl (0.1 mol/L), and 0.5 % α-amylase was added. The mixture was hydrolyzed at 60 °C for 2 h, and the enzyme was inactivated by boiling. The pH was then regulated to 9.0 using NaOH (0.1 mol/L) at 55 °C, and 1 % alkaline protease was added. Hydrolysis was carried out for 3 h, and the enzyme was inactivated by heating again. After adjusting the pH to 4.2, add 0.5 % glucoamylase and hydrolyze at 50 °C for 2 h. Inactivate the enzyme after hydrolysis. Subsequently, centrifuge the sample at 4500 rpm for 10 min, wash the sediment with a 95 % ethanol solution 4 times, freeze-dry it, and label as CBIDF.

2.3. Modification of CBIDF

2.3.1. Ultrasonic treatment

The method of ultrasonic treatment was referenced by Li et al. [9], with minor modifications. 10.0 g of CBIDF was weighed and dispersed in 200 mL of deionized water, the mixture was treated with ultrasound at a power of 500 W for 30 min, the suspension was concentrated to a quarter of its original volume under reduced pressure at 60 °C. The freeze-dried sample was then labeled as U-CBIDF.

2.3.2. Microwave treatment

Microwave treatment was referred to Cantu et al. [17], with slight adjustments. The samples were dissolved as described previously and microwaved at 800 W for 10 min. The suspension was concentrated to a quarter of its initial volume under reduced pressure at 60 °C. The sample obtained after freeze-drying was labeled as M−CBIDF.

2.3.3. Ultrasonic-microwave treatment

10.0 g of CBIDF were weighed and dispersed in 200 mL of deionized water in a special container of the ultrasound-microwave synergistic extractor (CW2000, Shanghai Xintuo Technology Co., Ltd., China). After a single ultrasonication for 20 min, the microwave was turned on and the synergistic treatment was carried out for 10 min. After the ultrasound-microwave treatment, the suspension was concentrated to a quarter of its original volume under reduced pressure at 60 °C. The resulting sample obtained after freeze-drying was labeled as U-M−CBIDF.

2.4. Physicochemical properties

2.4.1. Basic composition

The DF and SDF contents were evaluated employing the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC) method 991.43. The moisture content was determined by the AOAC method 925.40 until the specimen attained a constant weight at 105 °C. The crude protein content was measured using a Kjeldahl apparatus based on AOAC method 950.40. The ash content was estimated with the standard AOAC method 923.03 implemented with a muffle furnace. Using AOAC method 920.39, the sample's crude fat content was determined through Soxhlet extraction recovery.

2.4.2. Particle size and color parameters

The sample's particle size distribution underwent analysis through a laser particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 3000, Malvern, UK). Distilled water was used to dilute the sample in a 1:10 ratio to avoid multiple scattering effects. The particles' size distribution detection range spanned records from 100 nm up to 2000 μm.

Additionally, the sample underwent color examination using a colorimeter (CR-10 Plus, Tokyo, Japan) where L*, a*, and b* characterized factors for luminance, redness, and yellowness, respectively.

2.4.3. Water-holding capacity (WHC)

CBIDF samples of a certain weight were weighed and mixed with water to prepare a suspension with a concentration of 5 % and deposited at 25 °C for 4 h. Centrifuge at 4500 rpm for 10 min and calculate the weight.

| (1) |

where Ww represents the weight of the sediment, and Ws represents the weight of the dried CBIDF sample.

2.4.4. Oil-holding capacity (OHC)

1.0 g of CBIDF was blended with 8.0 g of soybean oil and maintained at a constant temperature of 25 °C for 4 h. Subsequently, it was centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min, and the weight was calculated.

| (2) |

where Ww represents the wet weight of the sediment, and Ws represents the weight of the dried CBIDF sample.

2.4.5. Water swelling capacity (WSC)

1.0 g of CBIDF was weighed and mixed with 10 mL of water at 25 °C for 18 h. The sample solution's initial volume and the hydrated volume of the sample solution were recorded respectively.

| (3) |

where V1 represents the volume of hydration, V0 represents the original volume, and Ws represents the weight of the dried CBIDF sample.

2.4.6. Cholesterol adsorption capacity (CAC)

1.0 g of CBIDF was loaded in a 50 mL centrifuge tube, followed by the addition of 30 mL of diluted egg yolk solution (diluted by adding 9 times the volume of water to the egg yolk). To simulate the gastric and intestinal environments in vitro, the pH was regulated to 2.0 and 7.0, respectively. The reactions were shaken at 150 rpm and 37 °C for 2 h, followed by centrifugation at 4500 rpm for 10 min. The absorbance values of the supernatants were determined at 550 nm.

| (4) |

where N1 represents the cholesterol content in the diluted yolk solution, N2 indicates the content of cholesterol in the mixed liquor after absorption, and Ws represents the weight of the dried CBIDF sample.

2.4.7. Cholate adsorption capacity (CLAC)

The CLAC was referenced by the method of Yang et al. [22]. 0.5 g of CBIDF and 50 mg sodium cholate (SC) or sodium taurocholate (STC) were weighed and dissolved in 50 mL of PBS buffer (pH 7.0) and vibrated at a constant temperature of 37 °C for 2 h. The compound was then centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min, and the absorbance of the resulting supernatant was measured using furfural colorimetry.

| (5) |

where C1 represents the initial content of SC/STC, C2 represents the termination content of SC/STC, and Ws is the weight of the dried CBIDF sample.

2.5. Structural Characterization

2.5.1. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Take the required sample amount and add it to a mortar. Add KBr and grind it thoroughly. Put the mixture into a mold and make a thin slice. Analyse and scan the sample using an FTIR Spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) within the range of 400–4000 cm−1.

2.5.2. X-ray diffraction (XRD)

An appropriate amount of sample should be taken in the sample tank. Use a glass plate to compact the sample and make the surface flat. Then, insert the sample plate into the test base of the instrument (D8 Advance, Bruker, Germany). The test conditions require a voltage load of 40 kV and a scanning speed of 0.02 °s−1.

2.5.3. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Samples were imaged using a JSM-6390LA scanning electron microscope (NTC, Tokyo, Japan) at 5.0 kV acceleration electric potential.

2.6. Hypoglycaemic activity in vitro

2.6.1. Glucose adsorption capacity (GAC)

The GAC was referenced by the method of Jiang et al. [21]. 0.5 g of CBIDF sample was blended with 50 mL of glucose solution at various concentrations (10, 20, 35, 50 mmol/L). The mixture was shaken (150 rpm) at 37 °C for 6 h. Centrifugation was performed at 4500 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was collected for glucose content determination using the kit method.

| (6) |

where Ni represents the initial glucose content, Ne denotes the content of glucose content after absorption, and Ws represents the weight of the dried CBIDF sample.

2.6.2. Glucose dialysis retardation index (GDRI)

The method described in Zhu et al. was followed [23]. CBIDF was dissolved in a glucose solution (50 mmol/L) at a ratio of 1:50 (g/mL). The solution was loaded into a dialysis bag with 6,000 MWCO, placed in a beaker, and dialysed at 37 °C with 4 times the volume of distilled water as dialysate. The glucose content of the dialysate was measured at different dialysis times (10, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min). The CBIDF-free group was used as the control group.

2.6.3. Starch digestion in vitro

In this experiment, 20 mg of CBIDF were blended with 50 mg of corn starch in 10 mL of buffer (pH 5.2) at a constant temperature of 37 °C for 15 min. Following this, 2 mL of α-amylase (6 U/mL) and 2 mL of α-glucosidase (0.4 U/mL) were added, and the reaction was carried out in a shaken water bath (150 rpm) for 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. Finally, the enzymes were inactivated by heating. After cooling, the sample was centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was retained for glucose concentration determination. The CBIDF-free group was used as a the control group.

2.6.4. α-glucosidase activity inhibition

The methodology used in Chen et al. [24] was appropriately referenced and modified. A mixture of 0.5 mL α-glucosidase (0.4 U/mL) and 1.0 mL PBS (pH 6.8) was combined with 20 mg CBIDF. The resulting solution was placed in a water-bath shaker (150 rpm) at 37 °C for 15 min. Following this, 1.0 mL PNPG (10 mmol/L) was added as the substrate to start the reaction. After 30 min, the reaction was immediately terminated by adding 5.0 mL Na2CO3 (0.2 mol/L). The reaction underwent centrifugation at 4500 rpm for 10 min, and the resulting supernatant was retained and its absorbance was determined at a wavelength of 405 nm.

| (7) |

Where A1 is the absorbance without adding α-glucosidase; A2 is absorbance without CBIDF; A3 is the absorbance of adding CBIDF and α-glucosidase; A4 is absorbance with CBIDF but without α-glucosidase.

2.6.5. α-amylase activity inhibition

The α-amylase activity was determined using a previously established method [25], with some modifications. 0.5 mL of α-amylase (6 U/mL) was mixed with 1.0 mL of PBS (pH 6.9) and 20 mg CBIDF. The reaction mixture was then subjected to a water-bath shaker (150 rpm) at 37 °C for 15 min. To initiate the reaction, 1.0 mL of 1 % (w/w) soluble starch solution was added as the substrate. After 5 min, the reaction was stopped by adding 5.0 mL DNS. It was then boiled for 10 min, cooled, and centrifuged at 4500 rpm for another 10 min. The supernatant was retained and its absorbance was determined at a wavelength of 500 nm.

| (8) |

Where A1 is the absorbance without adding α-amylase; A2 is absorbance without CBIDF; A3 is the absorbance of adding CBIDF and α-amylase; A4 is absorbance with CBIDF but without α-amylase.

2.7. Biological activities

2.7.1. Prebiotic activity in vitro

Li et al.'s method, with minor modifications, was used to reference [26]. 1.0 mL of activated Lactobacillus acidophilus or Bifidobacterium longum was successively inoculated into carbon-free and sterilized MRS liquid medium, and 1 % glucose, inulin, or CBIDF prepared by different modification methods were sequentially added to the media. The cultures was then incubated under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C. Carbon-free MRS medium was employed as the control group. A sterile tube was used to collect 1.0 mL of bacterial solution at 0, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48 and, 54 h, respectively. The tube was then centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 min, and the resulting supernatant was retained to measure the OD600 value and draw the growth curve.

2.7.2. Probiotic adhesion activity

The adherence to probiotics was determined through coprecipitation method [27]. Bacterial cells (Lactobacillus acidophilus or Bifidobacterium longum) were diluted to 107 cfu/mL with a neutral PBS buffer solution. 2.0 mL of the bacterial suspension was mixed with 20 mg CBIDF, which was prepared using different modification methods, and used as the sample and bacteria group. The group containing only the sample without the bacterial suspension was used as the sample control group. The bacterial suspension-only group was used as a comparison for the results. Each group was cultured at 37 °C for 10 min and began to precipitate at room temperature. 3 mL of solution was absorbed from the bottom of the sample and measured at 540 nm at 20, 40, 60, and 80 min, respectively.

| (9) |

Where a represents the absorption value of the group including CBIDF and bacteria, b represents the absorption value of the group including CBIDF and without bacteria, and c represents the absorption value of the group including bacteria only.

2.8. Statistic analysis

All test data were determined 3 times and presented as “mean ± standard error”. The data was analysed using SPSS 22.0 software, undergoing both Duncan's test and ANOVA. We considered a probability level of 5 % (P < 0.05) statistically significant either between or within groups. Cluster and correlation heatmap analysis were conducted using Origin 2022.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical characteristics

The yields, chemical composition, color parameters, and physicochemical properties of CBIDF obtained through diverse modifications are shown in Table 1. The percentage of SDF increased significantly after modification, indicating that ultrasound and microwave processes may disrupt the structure of DF and convert IDF into SDF. The highest content of SDF was achieved after ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification, indicating that the synergistic effect of ultrasound and microwave was more effective than individual treatment. Basic component analysis revealed that CBIDF had low levels of non-fiber substances such as water, protein, fat, and ash, indicating high purity of the prepared corn bran insoluble dietary fiber (CBIDF). The particle size and color of CBIDF prepared by different modification methods showed slight changes. Among these methods, U-M−CBIDF displayed the smallest particle size and the greatest specific surface area (SSA). Generally, a smaller particle size results in a better adsorption index, while an increase in SSA contributes to the formation of additional hydrogen bonding or dipole space to accommodate water molecules [28], [29]. Additionally, the color of food ingredients is a crucial factor that affects consumer acceptability of the final product. The brightness of all four samples was high (L* > 75), and the color had a yellowish tone. Therefore, it has a broad application prospect.

Table 1.

Yields, chemical composition, particle size distribution, color parameters, and physicochemical properties of CBIDF obtained by different modification methods.

| CBIDF | U-CBIDF | M−CBIDF | U-M−CBIDF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | |||||

| IDF(%) | 84.67±0.31a | 80.33±0.24c | 81.70±0.29b | 74.92±0.37d | |

| SDF(%) | 1.98±0.11d | 6.32±0.28b | 4.95±0.17c | 11.73±0.31a | |

| Chemical composition | |||||

| Moisture(%) | 2.39±0.12a | 2.41±0.17a | 2.31±0.09a | 2.37±0.15a | |

| Protein(%) | 1.16±0.05a | 0.87±0.04b | 0.94±0.03b | 0.71±0.02c | |

| Ash(%) | 2.14±0.16a | 2.23±0.11a | 2.21±0.19a | 2.16±0.13a | |

| Fat(%) | 1.57±0.07a | 1.50±0.05a | 1.42±0.11a | 1.32±0.04a | |

| Particle size distribution | |||||

| D10(μm) | 16.98±0.04a | 12.09±0.01c | 12.96±0.04b | 10.58±0.04d | |

| D50(μm) | 137.2±0.55a | 84.01±0.28b | 72.89±0.39c | 68.34±0.43d | |

| D90(μm) | 366.6±0.93a | 219.9±0.72b | 200.0±0.81c | 201.8±0.58c | |

| D[4], [3](μm) | 170.9±0.32a | 101.7±0.29b | 92.12±0.20c | 89.82±0.19d | |

| D[3], [2](μm) | 36.71±0.08a | 26.19±0.06b | 26.08±0.07b | 23.23±0.05c | |

| Specific surface area (m2/g)) | 60.52±0.76c | 84.83±0.59b | 85.18±0.82b | 95.65±0.67a | |

| Color parameters | |||||

| L* | 77.32±1.05ab | 78.23±1.46a | 75.28±1.73b | 75.97±1.07ab | |

| a* | 3.19±0.23c | 3.72±0.20b | 2.82±0.35c | 4.28±0.06a | |

| b* | 18.91±0.17a | 18.06±0.13bc | 17.91±0.28c | 18.52±0.28ab | |

| Physicochemical properties | |||||

| WHC(g/g) | 4.52±0.11c | 5.17±0.07b | 5.08±0.09b | 5.98±0.12a | |

| WSC (mL/g) | 2.37±0.08c | 2.73±0.07b | 2.42±0.05c | 2.91±0.09a | |

| OHC(g/g) | 1.82±0.11d | 3.54±0.07b | 3.08±0.09c | 4.32±0.12a | |

| CAC(mg/g) | pH2.0 | 3.38±0.37d | 13.46±0.34b | 11.92±0.42c | 20.08±0.53a |

| pH7.0 | 6.63±0.45d | 21.35±0.39b | 18.33±0.41c | 28.72±0.58a | |

| CLAC(mg/g) | SC | 6.63±0.45c | 14.02±0.35b | 14.52±0.23b | 20.47±0.49a |

| STC | 8.13±0.19c | 12.82±0.22b | 13.06±0.24b | 18.56±0.37a | |

CBIDF, corn bran IDF; U-CBIDF, ultrasonic modified corn bran IDF; M−CBIDF, microwave modified corn bran IDF; U-M−CBIDF, ultrasonic-microwave synergistic modified corn bran IDF. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were found between the values represented by different letters in the same index.

The basic physicochemical properties of DF, including its water-holding capacity (WHC), and water swelling capacity (WSC), play a crucial role in improving physical function. DF is considered a high-quality functional food component due to its ability to improve food texture and viscoelasticity, promote intestinal peristalsis, and prevent constipation [30]. The oil-holding capacity (OHC) is also an important indicator of its ability to enhance lipid metabolism and lower serum cholesterol levels. The physicochemical properties of CBIDF were substantially upgraded (P < 0.05) after modification in different ways. Ultrasonic modification was found to be more effective than microwave modification (P < 0.05), while the best results were achieved through the synergistic effect of ultrasonic and microwave modification. The WHC, WSC, and OHC of CBIDF were 1.32, 1.23, and 2.37 times that of CBIDF, respectively, following ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification. This could be attributed to the reduction in particle size and the increase in specific surface area resulting from the combined treatment of ultrasound and microwave. As a result, more hydrophilic groups were exposed, leading to a greater contact area between IDF and water. IDF is widely recognised for its excellent water retention and absorbency, which can lead to increased defecation, improved gastrointestinal motility, and a lowered risk of bowel cancer [17]. Additionally, it has outstanding oil retention properties, which can greatly reduce the body's intake of oil [31]. Cholesterol adsorption capacity (CAC) has also been shown to effectively reduce serum cholesterol levels, resulting in a reduction of blood lipids [32]. Under both acidic and neutral conditions, the CAC of U-M−CBIDF was 5.94 times and 4.33 times greater than that of CBIDF, respectively. This is likely due to the loose structure of U-M−CBIDF after ultrasonic and microwave treatment, which exposes more lipophilic groups, resulting in stronger IDF affinity with oil. Additionally, the honeycomb structure facilitates the infiltration of oil molecules. Qiao et al. demonstrated that DFs with loose, porous, and high OHC generally exhibit superior cholesterol adsorption capacity [33]. DF reduces blood cholesterol content by adsorbing bile acid salts, preventing their re-absorption from the small intestine into the enterohepatic circulation, promoting cholesterol metabolism, and preventing diseases. The cholate adsorption capacity (CLAC) of modified CBIDF increased significantly (P < 0.05) with the use of ultrasonic microwave synergistic modification technology. This indicates that the functional characteristics of CBIDF can be improved through this method.

3.2. Structural characteristics

3.2.1. FT-IR analysis

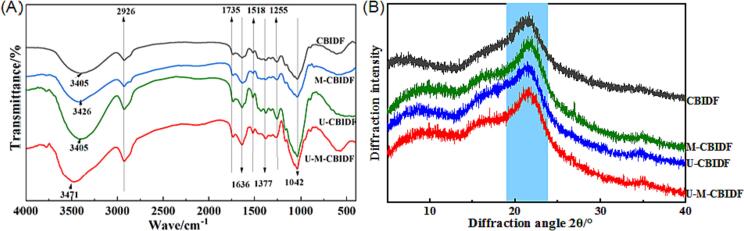

The FT-IR characteristic peaks of CBIDF obtained through various modification methods demonstrate similarities (Fig. 1(A)). This suggests that ultrasonic, microwave, and ultrasonic-microwave collaborative modification methods do not alter the primary absorption peaks of CBIDF. Moreover, the cellulose or hemicellulose O-H stretching vibration results in a clear absorption peak, ranging between 3400 – 3500 cm−1, for CBIDF acquired via different modification methods [34]. A prominent absorption peak was observed at 2926 cm−1, indicating the presence of C-H stretching vibration of the methylene group. This suggests that CBIDF has the typical structure of cellulose, as reported by Yan et al. [35]. Additionally, tensile vibration of C = O were observed at 1735 and 1636 cm−1, suggesting that CBIDF contains –CHO or –COOH [36]. Lastly, the peaks at 1518 cm−1 confirmed the presence of the carboxyl group [37]. Peaks at 1255 and 1042 cm−1 suggest that CBIDF comprises sugar ring structures. The increased absorption peak intensity of CBIDF after microwave modification, ultrasonic modification, and ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification indicates a decrease in intermolecular forces of CBIDF, which exposes more –OH and C-O groups. Furthermore, the modified CBIDF is more effective in adsorbing heavy metals. This may be due to the presence of negatively charged carboxyl and hydroxyl groups on its molecular structure, which are involved in heavy metal adsorption through electrostatic attraction and surface complexation [38], [39].

Fig. 1.

FT-IR (A), X-ray diffraction (B) of CBIDF treated by different methods.

3.2.2. X-ray analysis

The XRD findings of CBIDF samples subjected to various modification procedures were disclosed in Fig. 1(B). The diffraction peaks of the CBIDF samples were primarily situated at around 10° and 22°, signifying cellulose type II configuration and cellulose type I double helix configuration, respectively [40]. The outcomes indicated the absence of marked dissimilarities in the crystal structure of modified CBIDF. The modification of IDF causes a decrease in the diffraction peak at approximately 22° compared to CBIDF. This may be due to the destruction of hemicellulose irregularities attached to the cellulose surface after ultrasonic, microwave, and ultrasonic-microwave synergistic modification. Consequently, there is a decline in the crystalline structure of CBIDF [41]. The enhanced WHC, OHC, and adsorption properties of the modified CBIDF may be attributed to its relatively loose structure and weak interaction forces.

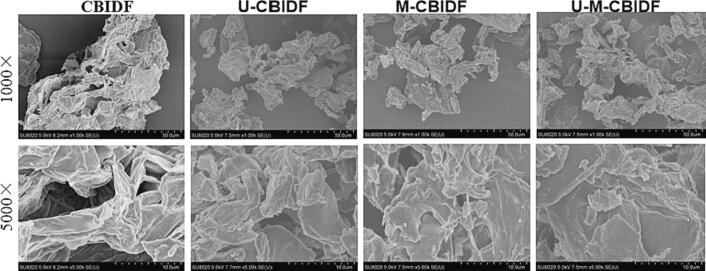

3.2.3. SEM analysis

SEM images of CBIDF at magnifications 1000× and 5000× were shown in Fig. 2. The outcome of the experiments revealed that the structure of the treated CBIDF was partially damaged compared to the untreated CBIDF. The particles of CBIDF underwent noticeable changes. The synergistic modification of ultrasound and microwave resulted in a more distinct degree of CBIDF granulation. Additionally, the ultrasound modification may have ruptured the IDF cell wall and broken cellulose and hemicellulose chains, leading to the highest degree of structural porosity, while the microwave modification resulted in the destruction of lignin and other components [40]. The dual characteristics of ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification effectively destroy the cross-linking of IDF molecules, thereby influencing the microstructure of CBIDF through various modification techniques.

Fig. 2.

SEM images of CBIDF acquired using different modification techniques at magnifications of 1000× and 5000×.

3.3. In vitro hypoglycemic activities

Numerous investigations have also confirmed that the loose and porous structure of IDF has potent adsorption properties, which efficiently prolong the absorption and utilization of carbohydrates, leading to a decrease in postprandial blood sugar levels. This gives it a hypoglycemic effect [22]. The hypoglycemic properties of CBIDF obtained through various modification methods in vitro were shown in Fig. 3. CBIDF has a strong glucose adsorption capacity (GAC), which showed a positive correlation with glucose concentration (Fig. 3A). The GAC of CBIDF was (0.733±0.011) mmol/g·L at a glucose concentration of 50 mmol/L. This increased by 27.15 % in U-M−CBIDF, with a GAC value of (0.932±0.013) mmol/g·L. Furthermore, the modified CBIDF showed significantly increased GAC (P < 0.05), indicating that ultrasonic and microwave modifications had an energetic impact on the GAC. The concentration of glucose in the dialysate increases over time (Fig. 3B). The rate of glucose diffusion was reduced by the addition of CBIDF, resulting in a significant decrease in glucose concentration after ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification. After an osmosis time of 180 min, the glucose concentration in the dialysate of the U-M−CBIDF group decreased by approximately 1.48 mmol/L compared to the control group. The loose fiber structure enhances the capillary effect, promoting affinity adsorption and physical binding to glucose molecules while reducing their free diffusion [42]. Furthermore, the influence of corn starch digestibility on CBIDF was shown in Fig. 3C. CBIDF reduced the concentration of glucose produced during starch digestion, indicating its ability to slow down the hydrolysis of starch. This effect was observed after microwave modification, ultrasonic modification, and ultrasonic-microwave synergistic modification. The addition of U-M−CBIDF resulted in a reduction of approximately 0.69 mmol/L in the glucose concentration produced by starch hydrolysis after 120 min. On the other hand, it is well known that α-amylase and α-glucosidase are vital enzymes that contribute to the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates consumed by the human body, so the inhibitory activity of these two enzymes has often been used as hypoglycaemic indicators in vitro [43]. The inhibition rate of U-M−CBIDF on two enzymes was (65.50±0.93)% and (21.41±0.52)%, respectively (Fig. 3D), which were 2.02 times and 2.52 times that of CBIDF. The combination of ultrasonic and microwave treatment can effectively reduce the particle size of IDF, which can then be embedded in starch particles to limit their gelatinisation. The modified IDF has a loose, porous structure that forms a physical barrier and restricts glucose diffusion [44]. Furthermore, the modified IDF reduces the activity of starch-digesting enzymes due to mixed or non-competitive inhibitors [45].

Fig. 3.

GAC (A), Glucose diffusion inhibition (B), Starch digestion (C), and Digestive enzyme inhibition (D) of CBIDF obtained through various modification methods. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed between the values represented by different letters in the same index.

3.4. Biological activities in vitro

Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium longum, as recognized intestinal probiotics, play an important role in the regulation human intestinal health. We tested the ability of the above two beneficial bacteria to utilize CBIDF as a carbon source in MRS media without other carbon sources, and compared the growth curves when glucose or inulin was used as carbon sources under the same conditions (Fig. 4a and b). Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium longum rapidly propagated within the initial 24 and 18 h, correspondingly, when glucose was used as the carbon source. When CBIDF obtained by different modification methods was used as carbon source, they showed strong persistence. The growth-promoting effects on Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium longum were ordered as U-M−CBIDF, M−CBIDF, U-CBIDF, and CBIDF from large to small, indicating that modified CBIDF was more easily utilized by probiotics, which promoted the proliferation of probiotics. Among the ultrasound-microwave synergistic modifications, the best effect was observed. The prepared CBIDF has a loose structure and weak intermolecular forces, which may be attributed to the dual effect of cavitation and heating during the ultrasonic and microwave cooperative treatment. This may also increase its susceptibility to bacterial contact, activating metabolic pathways that produce ATP without the need for additional chemical or enzymatic reactions, providing an energy source for probiotic growth [46], [47]. Bacterial adhesion to the matrix can promote the bacterial proliferation process [48]. On the other hand, the key to the ability of a bacterium to use a substrate as a nutrient for reproduction was that the bacterium should have a certain degree of adhesion to the substrate. The adhesion of two probiotics to different modified CBIDFs is shown in Fig. 4c and d. The adhesion of CBIDF obtained by different modification methods to Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium longum showed an overall pattern of increasing and subsequently slightly decreasing over time. The maximum adhesion value was (66.28±1.23)% and (70.42±1.13)%, respectively, when the adhesion time was 60 min. It was slightly higher than the adhesion of soybean skin IDF to Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium longum [41]. The test results demonstrated that the ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification could effectively enhance the probiotic properties of CBIDF. The increased adhesion of CBIDF to intestinal microorganisms in vitro may be due to the exposure of some proteins associated with IDF adhesion after modification treatment [26]. In conclusion, the ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification can enhance the survival and adhesion capabilities of IDF. This modification enables IDF to successfully colonise the intestinal epithelium and exert its probiotic activity. It provides a new approach to the study of functional dietary fibre modification technology.

Fig. 4.

Growth of Lactobacillus acidophilus (a), growth of Bifidobacterium longum (b), adhesion of probiotics of Lactobacillus acidophilus (c), adhesion of probiotics of Bifidobacterium longum (d) of CBIDF obtained by different modification methods. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were found between the values represented by different letters in the same index.

3.5. Multivariate analysis

In this paper, the differences in the data between the different groups are demonstrated concretely using a heatmap. It can be seen from the heatmap (Fig. 5A), that there was significant separability between CBIDF, U-CBIDF, M−CBIDF, and U-M−CBIDF based on the Euclidean correlation, indicating that different CBIDFs have significant variability. Cluster analysis of the CBIDF data led to the classification of their physical properties and bioactivities. The first cluster includes moisture, color parameters, fat, D50, protein, crystallinity, IDF, GDRI, and ash. Among them, U-M−CBIDF's information is considerably lower than CBIDF's, which directly indicates that the ultrasonic-microwave synergistic modification can significantly reduce the basic composition of CBIDF. The second cluster mainly includes some physicochemical properties (e.g. WHC, CLAC, OHC, CAC, WSC), in vitro hypoglycaemic activity (e.g. GAC, inhibition activity of α-glucosidase, and α-amylase), and prebiotic activity (growth of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium longum, as well as, the adhesion of probiotics). The U-M−CBIDF data show a significant increase compared to U-CBIDF and M−CBIDF. This suggests that microwave and ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification may be promising techniques for the production of high quality CBIDF and are essential for improving the physicochemical properties and bioactivity of CBIDF.

Fig. 5.

Clustering heatmap (A) and Pearson correlation (B) of CBIDF obtained by different modification methods.

In addition, the Pearson correlation (Fig. 5B) was performed to examine the correlation between the basic composition, physicochemical properties, in vitro hypoglycaemic activity, and prebiotic activity of CBIDF. The findings demonstrated a positive correlation between the content of SDF and some physicochemical properties (e.g. CAC, CLAC, GAC, WHC, OHC), as well as the α-amylase inhibition activity (P < 0.05). In contrast, a negative correlation was observed between the content of SDF and GDRI and crystallinity. The specific surface area (SSA) was positively correlated with CAC, CLAC, OHC, and α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition activity(P < 0.05). It was also positively correlated with prebiotic activity in vitro (P>0.05), and a negatively correlation with GDRI and crystallinity. Moreover, the crystallinity was negatively correlated with α-glucosidase, α-amylase inhibition activity, WHC, and OHC.

In general, ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification increased the proportion of SDF in CBIDF and decreased its crystallinity, thereby increasing the SSA of the fibers, which enhances the adsorption capacity of CBIDF [49]. After modification, the crystalline region of CBIDF was destroyed, and by increasing the contact area, it is more conducive to improving the hypoglycaemic activity and probiotic activity in vitro. In addition, the brightness of CBIDF modified by ultrasound and microwave remains high, making it suitable for widespread use in the food processing industry. The above data also indicate that increasing the SSA of IDF or decreasing its crystallinity is beneficial for improving its performance [50].

4. Conclusion

The study suggests that CBIDF modified by ultrasound-microwave synergistic treatment has significant advantages in terms of WHC, OHC, WSC, CAC, and CLAC. These outcomes may be due to the loose and porous microstructure of U-M−CBIDF, which exposes more functional groups, and the reduced relative crystalline content after modification. The ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification technique also improved the hypoglycaemic activity of CBIDF in vitro and its ability to promote probiotic growth and adhesion. The clustering and correlation heatmaps suggested that SDF content had positive correlations with certain physicochemical properties (e.g. WHC, CLAC, OHC, CAC, WSC). In contrast, crystallinity exhibited negative correlations with α-glucosidase, α-amylase inhibition activity, WHC, and OHC. In conclusion, the ultrasound-microwave synergistic modification can be used as an eco-friendly approach to enhance the usage of corn bran resources thereby producing CBIDF products of higher value. However, it is crucial to conduct an assessment of the functional features of U-M−CBIDF under varying food matrices before implementation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Caixia Jiang: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Xiangrui Zeng: Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Xuyao Wei: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Xiaolan Liu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Juntong Wang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Xiqun Zheng: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the major special sub-project of millions of engineering science and technology in Heilongjiang Province (2021ZX12B09-4), National 14th Five-Year Plan Sub-theme (2021YFD2100904).

Contributor Information

Xiaolan Liu, Email: liuxiaolan001@126.com.

Xiqun Zheng, Email: zhengxiqun@126.com.

References

- 1.He Y., Wang B., Wen L., Wang F., Yu H., Chen D., Su X., Zhang C. Effects of dietary fiber on human health. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 2021;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2021.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang M., Chen X., Dong L., Nan X., Ji W., Wang S., Sun W., Zhou Q. Modification of pea dietary fiber by ultrafine grinding and hypoglycemic effect in diabetes mellitus mice. J. Food Sci. 2021;86(4):1273–1282. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendall C.W.C., Esfahani A., Jenkins D.J.A. The link between dietary fiber and human health. Food Hydrocoll. 2010;24(1):42–44. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin D., Wu J., Yang Y., Long X., Wu Z., Qin W. The anti-lipidemic role of soluble dietary fiber extract from okara after fermentation and dynamic high-pressure microfluidization treatment to Kunming mice. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;57(11):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04463-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y., Ma Y. Optimization of the extrusion process for preparation of soluble dietary fiber-enriched calamondin pomace and its influence on the properties of bread. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;56(12):5444–5453. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-04015-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An N., Li D., Wang L., Wang Y. Microwave irradiation of corn kernels: Effects on structural, thermal, functional and rheological properties of corn flour. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;143 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xue J., Sheng X., Zhang B., Zhang C., Zhang G. The Sirtuin-1 relied antioxidant and antiaging activity of 5,5'-ferulic acid glucoside esters derived from corn bran by enzymatic method. J. Food Biochem. 2020;44(12):519–530. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Z., Yu X., Geng X. Protective role of three differently processed corn bran on glucose and lipid concentrations in d-galactose-induced mice model. J. Food Biochem. 2022;44:e13281. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S., Hu N., Zhu J., Zheng M., Liu H., Liu J. Influence of modification methods on physicochemical and structural properties of soluble dietary fiber from corn bran. Food Chem: X. 2022;14 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J.E., Vadlani P.V., Faubion J. Corn bran bioprocessing: Development of an integrated process for microbial lipids production. Bioresour. Technol. 2017;243(1):196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J., Bai J., Fan M., Li T., Li Y., Qian H., Wang L., Zhang H., Qi X., Rao Z. Cereal-derived arabinoxylans: Structural features and structure-activity correlations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;96:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.E. Zannini, Á. Bravo Núñez, A.W. Sahin, E. K.Arendt, Arabinoxylans as functional food ingredients: a review. Foods, 11(2022), 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11071026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Zhou D., Liu J., Liu S., Liu X., Tang X., Lv X. Characterization of alkaline and enzymatic modified insoluble dietary fiber from Undaria pinnatifida. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;55(12) doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zohaib H., Muhammad I., Haseeb A.M., Kamran K.M. Ultrasound-Assisted Modification of Insoluble Dietary Fiber from Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) Seeds. J. Food Quality. 2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/5035299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng G., Gan J., Dong R., Chen Y., Xie J., Huang Z., Gu Y., Huang D., Yu Q. Combined microwave and enzymatic treatment improve the release of insoluble bound phenolic compounds from the grapefruit peel insoluble dietary fiber. LWT. 2021;149 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang L., Ding X., Zhao Y., Li Y., Ma H. Modification of insoluble dietary fiber from garlic straw with ultrasonic treatment. J. Food Process. Pres. 2018;42(1):13399–13407. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.13399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantu J.T.M., Zhang X., Kazem A.E., Iacomini M., Hamaker B.R., Cordeiro L.M.C. Microwave treatment enhances human gut microbiota fermentability of isolated insoluble dietary fibers. Food Res. Int. 2021;143 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao Y., Tian B., Zhang Z., Yang K., Cai M., Hu W., Guo Y., Xia Q., Wu W. Positive effects of dietary fiber from sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] peels by different extraction methods on human fecal microbiota in vitro fermentation. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.986667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gan J., Huang Z., Yu Q., Peng G., Chen Y., Xie J., Nie S., Xie M. Microwave assisted extraction with three modifications on structural and functional properties of soluble dietary fibers from grapefruit peel. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;101(C) doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen L., Zhang Z., Zhao M., Senthamaraikannan R., Padamati R.B., Sun D., Tiwari B.K. Green extraction of soluble dietary fibre from coffee silverskin: impact of ultrasound/microwave-assisted extraction. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;55(5):2242–2250. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang C., Wang R., Liu X., Wang J., Zheng X., Zuo F. Effect of Particle Size on Physicochemical Properties and in vitro Hypoglycemic Ability of Insoluble Dietary Fiber From Corn Bran. Front. Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.951821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang X., Dai J., Zhong Y., Wei X., Wu M., Zhang Y., Huang A., Wang L., Huang Y., Zhang C., Chen X., Xiao H. Characterization of insoluble dietary fiber from three food sources and their potential hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects. Food Funct. 2021;14 doi: 10.1039/D1FO00521A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Y., Ji X., Yuen M., Yuen T., Yuen H., Wang M., Smith D., Peng Q. Effects of Ball Milling Combined With Cellulase Treatment on Physicochemical Properties and in vitro Hypoglycemic Ability of Sea Buckthorn Seed Meal Insoluble Dietary Fiber. Front. Nutr. 2022;20(8):672–684. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.820672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J., Wu S., Zhang Q., Yin Z., Zhang L. α-Glucosidase inhibitory effect of anthocyanins from Cinnamomum camphora fruit: Inhibition kinetics and mechanistic insights through in vitro and in silico studies. Int. J. Bio. Macromol. 2020;143(15):696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karimi A., Azizi M.H., Gavlighi H.A. Fractionation of hydrolysate from corn germ protein by ultrafiltration: In vitro antidiabetic and antioxidant activity. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;8(9):5192. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L., Zhao Y., Li J., Ban L., Yang L., Wang S., Zhu L., Song H., Liu H. The adhesion of the gut microbiota to insoluble dietary fiber from soy hulls promoted the proliferation of probiotics in vitro. LWT. 2022;153 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernando W.M., Flint S., Brennan C.S., Ranaweera K.K., Bamunuarachchi A.J. The influence of environmental factors on the adhesion of combinations of probiotics to rice fiber fractions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;28(6):2293–2302. doi: 10.1007/s11274-012-1035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyu B., Wang H., Swallah M.S., Fu H., Shen Y., Guo Z., Tong X., Li Y., Yu H., Jiang L. Structure, properties and potential bioactivities of high-purity insoluble fibre from soybean dregs (Okara) Food Chem. 2021;364(1) doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y., Yu K., Tian X., Sui W., Wu T., Wang S., Jin Y., Zhu Q., Meng J., Zhang M. Combined Modification of Soluble Dietary Fibers from Apple Pomace by Steam Explosion and Enzymatic Hydrolysis to Improve its Structural, Physicochemical and Functional Properties. Waste Biomass Valori. 2022;13:4869–4879. doi: 10.1007/s12649-022-01823-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong Y., Li Q., Zhao Y., Cao J. Effects of ultrasonic assisted high-temperature cooking method on the physicochemical structure characteristics and in vitro antioxidant capacities of dietary fiber from Dendrocalamus brandisii Munro shoots. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;97 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang L., Zhao Y., Huang J., Zhang H., Lin Q., Han L., Liu J., Wang J., Liu H. Insoluble dietary fiber from soy hulls regulates the gut microbiota in vitro and increases the abundance of bifidobacteriales and lactobacillus. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;57(1):152–162. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-04041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He Y., Li W., Zhang X., Li T., Ren D., Lu J. Physicochemical, functional, and microstructural properties of modified insoluble dietary fiber extracted from rose pomace. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;57(4):1421–1429. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-04177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiao C., Zeng F., Wu N., Tan B. Functional, physicochemical and structural properties of soluble dietary fiber from rice bran with extrusion cooking treatment. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;121 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H., Zhao C., Li J., Hussain S., Yan S., Wang Q. Effects of extrusion on structural and physicochemical properties of soluble dietary fiber from nodes of lotus root. LWT. 2018;93:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan X., Ye R., Chen Y. Blasting extrusion processing: The increase of soluble dietary fiber content and extraction of soluble-fiber polysaccharides from wheat bran. Food Chem. 2015;180:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.01.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alba K., MacNaughtan W., Laws A.P., Foster T.J., Campbell G.M., Kontogiorgos V. Fractionation and characterisation of dietary fiber from blackcurrant pomace. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;81:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y., Qi J., Zeng W., Huang Y., Yang X. Properties of dietary fiber from citrus obtained through alkaline hydrogen peroxide treatment and homogenization treatment. Food Chem. 2020;311(C) doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Z., Xiong X., Zeng Q., He S., Yuan Y., Wang Y., Yang X., Su D. Alterations in structural and functional properties of insoluble dietary fibers-bound phenolic complexes derived from lychee pulp by alkaline hydrolysis treatment. LWT. 2020;127(C) doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu H., Wang J., Yu J., Wang Y., Chi R. Adsorption performance and stability of the modified straws and their extracts of cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose for Pb2+: pH effect. Arab. J. Chem. 2020;13(12):9019–9033. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.10.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai W., Zhu J., Wu L., Qiao Z., Li L., Yan J. Preparation, characterization, rheological and antioxidant properties of ferulic acid-grafted curdlan conjugates. Food Chem. 2019;300(C) doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sang J., Li L., Wen J., Liu H., Wu J., Yu Y., Xu Y., Gu Q., Fu M., Lin X. Chemical composition, structural and functional properties of insoluble dietary fiber obtained from the Shatian pomelo peel sponge layer using different modification methods. LWT. 2022;165 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu M., Fang H., Gao Y., Su T., Niu Y., Yu L. Characterization of enzymatic modified soluble dietary fiber from tomato peels with high release of lycopene. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;99 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saikia S., Mahanta C.L. In vitro physicochemical, phytochemical and functional properties of fiber-rich fractions derived from by-products of six fruits. J. Food Sci Technol. 2016;53(3):1496–1504. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-2120-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H., Sun S., Ai L. Physical barrier effects of dietary fibers on lowering starch digestibility. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022;48 doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2022.100940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He T., Zhang X., Zhao L., Zou J., Qiu R., Liu X., Hu Z., Wang K. Insoluble dietary fiber from wheat bran retards starch digestion by reducing the activity of alpha-amylase. Food Chem. 2023;426 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y., Lei Y., Qi S., Fan M., Zheng S., Huang Q., Lu X. Ultrasonic-microwave-assisted extraction for enhancing antioxidant activity of Dictyophora indusiata polysaccharides: The difference mechanisms between single and combined assisted extraction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;95 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu H.Y., Rhim D.B., Kim S.K., Ban O.H., Oh S.K., Seo J., Hong S.K. Growth promotion effect of red ginseng dietary fiber to probiotics and transcriptome analysis of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. J. Ginseng Res. 2023;47(1):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2022.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye S., Shah B.R., Li J., Liang H., Zhan F., Geng F., Li B. A critical review on interplay between dietary fibers and gut microbiota. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022;124:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2022.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi H., Zhang M., Wang W., Devahastin S. Solid-state fermentation with probiotics and mixed yeast on properties of okara. Food Biosci. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feng X., Chen H., Liang Y., Geng M., He M., Huang Y., Li Y., Teng F. Effects of electron beam irradiation treatment on the structural and functional properties of okara insoluble dietary fiber. J Sci. Food Agric. 2022;103(1) doi: 10.1002/jsfa.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]