Abstract

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI), the field of infectious diseases (ID) faces both innovation and disruption. AI and its subfields including machine learning, deep learning, and large language models can support ID clinicians’ decision making and streamline their workflow. AI models may help ensure earlier detection of disease, more personalized empiric treatment recommendations, and allocation of human resources to support higher-yield antimicrobial stewardship and infection prevention strategies. AI is unlikely to replace the role of ID experts, but could instead augment it. However, its limitations will need to be carefully addressed and mitigated to ensure safe and effective implementation. ID experts can be engaged in AI implementation by participating in training and education, identifying use cases for AI to help improve patient care, designing, validating and evaluating algorithms, and continuing to advocate for their vital role in patient care.

Keywords: antimicrobial stewardship, artificial intelligence, infection control, infectious diseases, workforce

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, the field of infectious diseases faces both innovation and disruption. We provide considerations for infectious diseases specialists to leverage this growing technology while mitigating its risks.

The United States (US) Presidential Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence marks the impending impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on a variety of fields, including healthcare. The executive order highlights the important balance between mitigating the disruption of AI on jobs and human safety while promoting innovation to improve productivity and well-being [1]. AI refers to machines performing tasks that typically require human intellect. In various forms, these algorithms and models impact our daily lives as healthcare professionals and private citizens [2, 3]. AI encompasses various techniques, many of which are likely to impact the field of infectious diseases (ID). These non–mutually exclusive approaches include but are not limited to retrospective models (eg, surveillance), prospective models (eg, risk prediction), large language models (LLMs), image recognition, and robotics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Artificial Intelligence and Potential Applications to Infectious Diseases

| Artificial Intelligence Technique | Examples of Potential Applications to ID |

|---|---|

| Retrospective models: Use of machine learning (machines are trained to recognize patterns and gradually improve accuracy) or deep learning (neural networks are used to identify complex patterns) to evaluate a large volume of retrospective data |

|

| Prospective models: The application of machine learning/deep learning trained on retrospective data, applied to real-time risk prediction |

|

| Large language models: Processing and generating natural language using deep learning techniques |

|

| Image recognition: The application of machine learning/deep learning to convert images to data and identify patterns |

|

| Robotics: Machines with physical capabilities to perform tasks autonomously |

|

Similar to past technological revolutions, automation simultaneously contributes to scientific and economic progress while disrupting lives of humans potentially displaced by, or at least impacted by, machines. The AI revolution may automate approximately 300 million full-time jobs globally, with 80% of the US workforce experiencing a change in at least 10% of their tasks. While past revolutions displaced “unskilled” labor forces, today, “office jobs,” or those requiring cognitive skills, creativity, and higher education levels, may be the most vulnerable to current and future generations of automation [6, 7].

Job satisfaction among the ID workforce stems from human connections, its dynamic roles, exciting new discoveries, diverse patient care options, teaching, and collaboration with other specialties [8]. Additionally, we implement and lead safety programs like healthcare infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship. While it is hard to envision AI completely replacing these activities, automation necessitates reevaluating the contributions of ID to healthcare. Despite job satisfaction, ID physicians, pharmacists, infection preventionists, and public health epidemiologists spend excessive time on tasks, such as documentation, auditing antimicrobial orders, and mining the electronic health record (EHR) for drug-related issues. A perennial time-consuming task in ID is combing through massive outside hospital records to identify a few key pieces of relevant information, such as confirmation of culture susceptibility. AI-driven automation prompts us to explore where it can help to improve efficiency, a major need in the practice of ID.

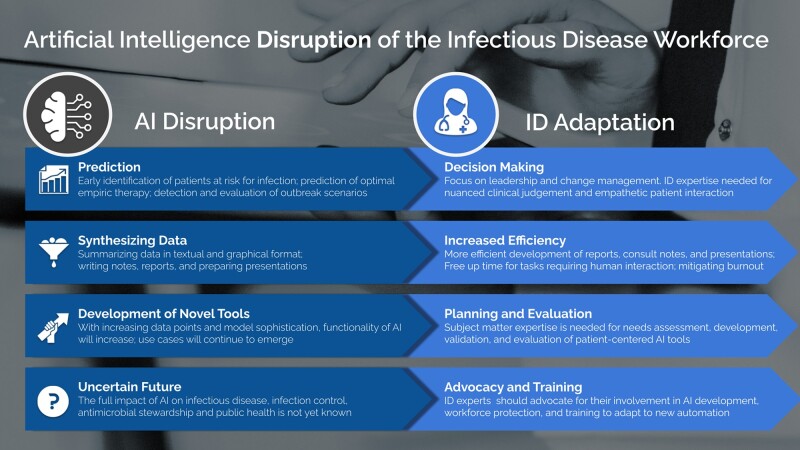

While the ID workforce is not in danger of being fully replaced by machines in the near future, emerging technologies do represent an opportunity to facilitate and improve day-to-day work in ID. Identifying areas where automation can assist with tasks may help improve efficiency and address staffing and personnel challenges plaguing the field [9]. The aim of this review is to utilize illustrative examples from ID, antimicrobial stewardship, and infection prevention to highlight risks and growth possibilities. In addition, suggested approaches are provided in which institutional leaders and professional societies can proactively advocate for the ID workforce to help the specialty weather looming disruptions and challenges to its roles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Artificial intelligence (AI) disruptions and proposed infectious diseases (ID) workforce adaptations.

WHAT WILL AI DO?

Facilitate Enhanced Decision Making

Lack of systems for near-real-time surveillance of pathogen identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing can contribute to delays in selection of appropriate antimicrobial therapy and failure to de-escalate treatment in a timely manner. Automated algorithms to identify infections and match organisms to effective treatment are a potential solution to this perennial challenge [10].

While most examples of the application of AI to ID are proof-of-concept studies and not widely implemented, increasing sophistication of tools such as machine learning to predict risk of complicated Clostridioides difficile infection [11], deep learning algorithms for identifying and classifying malaria blood smears [12], and classification of bacterial morphology on Gram stain [13] are likely to augment rather than replace the role of ID specialists. Such approaches may also help to free up time for laboratory and clinical personnel and address workforce shortages.

While still in the early stages of development, literature summary and appraisal tools may help in the future to facilitate faster decision making; caution is warranted with currently available technologies [14]. Eventually, efforts spent performing online literature searches to address complex patient care issues may be performed by AI with more efficiency and greater scale. ID is an especially dynamic field of medicine in part due to regionally and temporally variable epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance and the emergence of novel pathogens. Given the dynamic nature of the ID landscape and the rapidly changing literature, AI-assisted rapid literature reviews are a particularly attractive option to ensure recommendations are appropriate to current context and conditions [15].

Monitoring of antimicrobial use and resistance is becoming increasingly important to evaluate the impact of interventions, support benchmarking, and meet regulatory requirements. Machine learning models can incorporate a large volume of patient-specific encounter-level variables to improve antimicrobial use risk adjustment at the level of the individual patient and improve retrospective surveillance and interhospital comparison [16]. However, machine learning risk prediction models are inherently only able to analyze retrospective data documented in the clinical chart. If a key piece of information, such as a travel history, is not available in the clinical chart, the machine learning risk prediction tool will make recommendations based on the information it can “see” in the EHR—not based on reality. Thus, as highlighted in the trustworthy AI framework, it is critical that these algorithms be transparent and that clinicians applying them understand what information they are based on [17]. Relying on algorithm output based on incomplete information has the potential to worsen clinical decision making and antimicrobial selection.

Support Precision Infectious Diseases

AI has the potential to provide management recommendations tailored to individual cases, offering precision and speed that traditional consultation might struggle to match [18]. Automated systems equipped with sophisticated algorithms aim to support real-time analysis of complex patient data, identify subtle patterns, and expedite the diagnosis of infections [19, 20]. For instance, machine learning models have been used to help predict the risk of multidrug-resistant organisms and, when coupled with real-time computer prescriber order entry prompts, can help to reduce unnecessarily broad-spectrum empiric therapy for patients with pneumonia [21]. By leveraging AI-powered prediction into ID consultation, providers can provide swift and accurate recommendations while optimizing time spent with patients.

However, the implementation of automated systems for ID management necessitates robust validation and rigorous testing to ensure accuracy, reliability, and the avoidance of unintended consequences [22]. As noted above, algorithms can only interpret data that are collected and documented; missing data are inherently also missing from the analysis. Large language generative AI models are rapidly advancing but currently suffer from several limitations as they apply to medical decision making. In particular they lack contextual awareness, lack transparency in the underlying training data, and can perpetuate existing biases [23]. As such, in its current state, the output of LLMs is highly error-prone, which can lead to hazardous clinical consequences. For example, in a prospective cohort study, when tasked with providing comprehensive management plans for patients with bloodstream infections, GPT-4 provided harmful recommendations in 16% of cases. Similarly, when prompted to provide a management plan for cryptococcal meningitis, GPT-3.5 often authoritatively provided hazardous recommendations and incorrect citations [24]. Additionally, there are significant privacy concerns to sharing data with large language models including privacy leakage from the underlying data used to train the model or leakage from the inputted data [25]. Such concerns may persist even for Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)–compliant LLMs due to the risk for reidentification [26]. This risk of unintended consequences further emphasizes the importance of actively involving ID specialists, (physicians, pharmacists, and infection preventionists), in collaboration with AI experts to test, validate, and fine-tune algorithms and protocols and to develop infrastructure to ensure patient safety and privacy are protected and maintained [18, 25, 27]. Further, the safe scale-up of AI to support ID practice requires high-quality data sources, robust ethical and data governance guardrails, and interoperability standards [28]. ID experts will be an important part of these interdisciplinary efforts to improve data quality and stewardship to support “precision ID.”

Improve Detection and Outbreak Management

Traditional outbreak detection is labor intensive and has low sensitivity and specificity. Automated real-time infection surveillance tools using machine learning can enable early detection of clusters and facilitate earlier intervention. Coupled with genomic data, predictive models can detect concurrent outbreaks from a shared source separated in space and time [29]. If run in real-time, the combination of whole genome sequencing with machine learning of the EHR can improve outbreak detection and identify clusters that would have otherwise been undetected using traditional infection prevention approaches [30]. In the outpatient setting, the increasing prevalence of wearable electronic devices, like smartwatches, may help facilitate improved contact tracing. A supervised learning model has been used along with Bluetooth proximity sensing to estimate exposure risk [31].

Protocols for patient isolation, healthcare-associated infection (HAI) bundles, and public health reporting, often algorithmic in nature, are ideal for AI-driven automation and integration into decision support strategies [20, 27, 32].

Streamline Workflow

Prospective audit and feedback is a labor-intensive but effective strategy in antimicrobial stewardship programs. However, not all patients reviewed by antimicrobial stewardship clinicians require intervention. Machine learning models may be helpful to identify patients more likely to require intervention, such as intravenous to oral switch or de-escalation [33, 34], thereby increasing the yield of clinician time and effort. As such, emerging tools may help streamline workflow and mitigate provider burnout.

Retrospective surveillance of hospital-acquired infections is often a time-consuming task for infection prevention professionals. A study using fictitious patient data found that after repeated training, GPT-4 exhibited a high sensitivity and specificity for identifying patients with catheter-associated urinary tract infections [35]. Such approaches may help to free up infection prevention professional time to perform other prevention-related activities. However, there are several hurdles that must be overcome before implementation, such as ensuring that reliable training data exist; validation in different contexts; and meeting privacy and regulatory requirements [36].

Additionally, AI can contribute to drafting reports and presentations, a task that requires substantial time and effort [37]. At present, human oversight is necessary to minimize errors and maximize benefits [38, 39], but will allow ID professionals to explore new avenues for patient and provider interaction across the healthcare spectrum at the individual and system levels [10]. We explore these essential opportunities below.

WHAT WILL HUMANS DO?

Ensure Patient-Centered Decision Making

“AI output is more effective when viewed as a member of the team rather than as a substitute for clinical judgment.” —N. R. Sahni and B. Carrus [40]

The rapid expansion of AI is fueled by exponentially decreasing costs of prediction, according to economists and AI researchers Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans, and Avi Goldfarb [41]. They suggest that prediction (performed by machines) and judgment (performed by humans) are distinct phenomena, and the value of human judgment will increase as the cost of prediction falls. ID specialists will face a paradigm shift, where their tasks may change as they continue to make increasingly impactful decisions in the healthcare system. Machine learning can identify pathogens and predict antimicrobial susceptibility from matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) profiles and whole genome sequencing [42, 43]. But after prediction, ID expertise is still required to select optimal antimicrobial treatment regimens based on past medical history, severity, comorbidities, and patient preferences. With increasing variables in machine learning algorithms, prediction accuracy will improve, but expert input is necessary to assess patient care nuances and include missing or overlooked information. In the airline industry, the autopilot does not replace the pilot's judgment; it maximizes operator reliability and improves flight safety. ID practitioners must vigorously argue for their critical, nuanced, and patient-centered role in the decision-making process.

Planning and Implementation

“The best way to predict the future is to create it.” — P. Drucker & A. Lincoln

Compared to fields such as e-commerce and advertising, the adoption of AI in healthcare is slow due to regulatory requirements, the heterogeneity of patient care settings, different platforms used across healthcare systems, concerns about privacy, and risk associated with inaccurate output. To mitigate these concerns and ensure effective and safe use of AI, ID experts play an important role in the adoption, planning, and implementation of AI [40]. ID experts should be thoroughly involved in needs assessments to identify and prioritize the most useful, feasible, equitable, and cost-effective tools for their setting. Needs assessment can identify whether operational (eg, automated writing and formatting of clinical notes through EHR integration, voice and conversation recognition), laboratory (eg, point-of-care testing, early pathogen detection, antimicrobial susceptibility testing [AST] prediction), or clinical/surveillance (eg, prediction of patient or population risk, identifying patients at risk for C difficile infection, tracking and reporting antibiotic resistance acquisition across the healthcare continuum, and early identification of clusters or outbreaks using AST or genetic testing) functionality is useful to our practice setting. Each of these functions requires thorough planning (eg, deciding on thresholds for reporting and to whom to report), validation (evaluating the sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value, and predictive value for these tools compared to a gold standard), and iterative improvement over time based on feedback and evaluation.

In the book Power and Prediction, authors Agrawal, Gans, and Goldfarb discuss 2 different types of AI interventions: point solutions and system solutions [44]. Point solutions involve a replacement of tasks (eg, using deep learning to support identification of pneumonia on chest radiographs), whereas system solutions require a greater investment of time, energy, and money by overhauling the entire process (eg, indication-based machine learning–driven antimicrobial prescribing) but can be highly impactful. Along this spectrum of interventions, ID expertise is needed to ensure solutions meet clinicians’ and patients’ needs, adhere to ethical principles, and are aligned with best practices.

The foundation of effective AI tools is a comprehensive and accurate source of data. The field of clinical informatics will play a key role in ensuring high-quality clinical data, interoperability across systems, and cost-effective clinical workflow integration. Experts trained in both ID and clinical informatics will be integral partners to support safe and effective AI strategies.

Evaluation and Research

“Without data, you're just another person with an opinion.” —W. Edwards Deming

Artificial intelligence in ID and healthcare is largely in the pilot stages and not yet subjected to rigorous evaluation. Simple and cluster randomized controlled trials evaluating machine learning models to improve the identification and management of ID will advance knowledge and uptake of new technology. This research gap provides an opportunity for ID specialists to not only shape the future of AI in infection prevention, antimicrobial stewardship, and public health, but also to be leading scholars on AI and clinical outcomes. Use of explainable AI techniques can help to “see what's under the hood” of AI models, thereby better understanding how they contribute to prediction (eg, the risk of antimicrobial resistance) and strengthen human trust with the technology [45]. Furthermore, with strong backgrounds in epidemiology and critical appraisal, ID specialists are well equipped to assess the quality of new AI literature and whether and how it should be implemented in their setting. ID specialists can enthusiastically engage and drive the agenda of patient-centered AI research.

The role of AI in drug discovery and development is also rapidly emerging. Deep learning models identify novel molecules with potential antibacterial activity for further investigation [46]. Clinical ID specialists have an intricate knowledge of the existing challenges with currently available therapies and can work with the biomedical industry to advocate for therapies with the most unmet clinical need.

Essential Leadership Skills That AI Cannot Replace

“Data should do the talking” is an oversimplification as data alone are not always convincing [47]. For maximal success, leaders must harness the art of persuasion, which is rooted in the psychology of relationships and influence, which are currently outside the scope of AI [47, 48].

Managing programs requires organizational and communication skills. ID specialists must serve as content experts as well as effective team managers to maximize clarity of purpose, scope, and action.

ID leadership skills that AI cannot teach or implement:

Identifying and overcoming human barriers: Saint et al noted the negative impact of active resistors and organizational constipators on healthcare-associated infection efforts [49]. ID specialists must be vigilant of human barriers and employ multilevel communication strategies to achieve change including education, audit and feedback, marketing, and empowerment of champions and facilitators [50]. This is relevant to all aspects of our work regardless of automation.

Identifying meaningful and effective collaborators: Positive deviance describes "certain individuals or groups with uncommon traits that enable them to find better solutions to problems than their peers, despite similar resources and challenges” [51]. In infection prevention, positive deviance initiatives resulted in improvements in hand hygiene, MRSA infection rates, and overall HAI rates [52]. ID leaders can encourage diverse participation and empower front-line workers to help improve systems-level decision making.

Engaging healthcare leaders: ID leaders must establish a sense of urgency, communicate the vision, empower action, and provide the necessary resources to institutionalize change [53]. Keeping healthcare executives consistently focused on ID is an ongoing struggle due to competing interests. ID leaders must maintain relevance by regularly engaging and communicating effectively with chief medical and safety officers, nursing leaders, and chief executive officers.

Empower colleagues to maximize team dynamics and mitigate burnout: ID leaders must remain vigilant of burnout and promote positive work environments [54]. In ID, physician burnout approaches 45% as reported in a subspecialty survey [55–57]. No simple solution exists for minimizing burnout in healthcare systems; however, team dynamics are critically important for engagement and group performance. Creating psychologically safe environments that promote open dialogue results in enhanced team bonding and daily interactions, which are primary drivers of high-functioning teams [58].

Professional advocacy: The perception of ID specialists by hospital stakeholders, including their ability to connect with and convince front-line staff of best practices, is greatly enhanced by communicating persuasively and effectively at the “podium,” which may include virtual meetings, local town halls and grand rounds, in-person conferences, or lectures to learners at one's own institution. These skills build trust and likeability, and improve retention of information. Messaging should be authentic to one's own experiences, interests, and beliefs; this level of personalization is outside of AI's current scope. After successful implementation of organizational change with measurable impacts on patient care, publication can further increase visibility for all involved [59].

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF INSTITUTIONS AND PROFESSIONAL SOCIETIES IN PREPARING US FOR DISRUPTION?

Impending changes to our daily lives as individual clinicians or disciplines within ID is apparent, as are potential ways to lean into changes and use them to our advantage. However, institutions and professional societies have a clear role in advocating for the individual and workforce.

Academic institutions and healthcare systems can help:

Convene multidisciplinary steering committees to establish AI best practices, maximizing its value for patient care and clinician education while setting clear parameters on its use for grant applications, research publications, scientific presentations, curricula, etc.

Set clear parameters for disclosing use of AI by clinicians in patient care and scientific presentations and scholarship.

As part of annual assessments and credentialing, institutions can ensure that staff are adequately trained on the strengths and limitations of AI as it pertains to patient outcomes, potential biases, and harms, such as loss of patient privacy [23].

Create patient-centered learning materials and videos in all major languages informing them how AI may be used in their personalized care.

Professional societies can help:

Promote equity in the development and application of AI. ID experts should be involved in validation to help minimize bias in machine learning algorithms, and advocate for equitable access to AI models to support underserved and/or marginalized communities. For example, data from insurance billing claims illustrate that the use of medical AI usage is skewed toward higher income, urban regions, and academic medical centers [60].

Advocate for the creation of diagnostic codes allowing clinicians to bill for time spent using AI to assist with patient care, in addition to other services rendered [6].

Vigorously advocate for protections on existing salary lines and reimbursement rates despite increasing automation. This is critically important as erosion of salary will almost certainly undermine the current workforce and serve as a recruitment disincentive, further reducing our specialty.

Advocate for ID consultation in the development of AI tools, which aims to streamline our work.

Consider the inclusion of specialized AI and data science tracks in annual meetings and increase the AI-related offerings for educational development.

Promote legislation aimed to improve loan repayment prospects for the ID workforce, to ensure funding for infection prevention and stewardship programs, and to stimulate and change incentive paradigms for new drug development. These include provisions to protect the workforce against job losses due to automation and create incentives for application of AI to advance the discovery and development of novel antimicrobial therapies, ID diagnostics, and vaccines.

“Be at the table” for national and global discussions pertaining to use of AI for research and publication and ensure protections on patient data and privacy.

CONCLUSIONS

As ID experts navigate this transformative juncture, our focus should not solely rest on the potential for automation to replace our roles, but also on how it can amplify our capabilities. By integrating automated systems thoughtfully, ID specialists can devote more time to matters requiring values-driven decisions, human intuition, emotional intelligence, multidimensional assessment, research prioritization, change implementation, and leadership across our professional spectrum. The collaboration between human expertise and AI-driven automation could lead to a symbiotic relationship where our decision-making is augmented by technology, resulting in improved patient outcomes and more efficient healthcare delivery. Application of these tools will require acquisition and refinement of skills such as implementation and dissemination science, as well as effective communication and negotiation strategies to better interface with other humans in healthcare (patients, families, colleagues, and executives). While change is inevitable, optimizing our relevance requires a comprehensive understanding of challenges and cultivation of the skills and functions that AI has yet to replace.

Contributor Information

Bradley J Langford, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Hotel Dieu Shaver Health and Rehabilitation Centre, Department of Pharmacy, St Catharines, Ontario, Canada.

Westyn Branch-Elliman, Department of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; National Artificial Intelligence Institute, Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, District of Columbia, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Priya Nori, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Montefiore Health System, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, USA.

Alexandre R Marra, Instituto Israelita de Ensino e Pesquisa Albert Einstein, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil; Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Gonzalo Bearman, Division of Infectious Diseases, Virginia Commonwealth University Health, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, USA.

References

- 1. The White House . Fact sheet: President Biden issues executive order on safe, secure, and trustworthy artificial intelligence. 2023. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/10/30/fact-sheet-president-biden-issues-executive-order-on-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-artificial-intelligence/. Accessed 27 November 2023.

- 2. Haug CJ, Drazen JM. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in clinical medicine, 2023. N Engl J Med 2023; 388:1201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harari YN. Yuval Noah Harari argues that AI has hacked the operating system of human civilization. The Economist. Available at: https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2023/04/28/yuval-noah-harari-argues-that-ai-has-hacked-the-operating-system-of-human-civilisation. Accessed 10 July 2023. Published 04/28/2023.

- 4. Segal R, Bradley WP, Williams DL, et al. Human-machine collaboration using artificial intelligence to enhance the safety of donning and doffing personal protective equipment (PPE). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2023; 44:732–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lu T, Bader H, Hauser K. Robot personal protective equipment (PPE) design, donning, and self-doffing. Intelligent motion laboratory. Available at: http://motion.pratt.duke.edu/nursing/doffing.html. Accessed 27 November 2023.

- 6. Kessler S. The A.I. revolution will change work. Nobody agrees how. The New York Times. 2023. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/10/business/ai-jobs-work.html? auth=login-google1tap&login=google1tap. Accessed 25 September 2023.

- 7. Miller CC, Cox C. In reversal because of A.I., office jobs are now more at risk. The New York Times. 2023. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/24/upshot/artificial-intelligence-jobs.html. Accessed 25 September 2023.

- 8. Nori P, Bartash R, Cowman K, Dackis M, Pirofski LA. Is burnout infectious? Understanding drivers of burnout and job satisfaction among academic infectious diseases physicians. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parkinson J. Addressing the decline in the number of infectious disease physicians. ContagionLive. 2023. Available at: https://www.contagionlive.com/view/addressing-the-decline-in-the-number-of-infectious-disease-physicians. Accessed 25 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Egli A. ChatGPT, GPT-4, and other large language models: the next revolution for clinical microbiology? Clin Infect Dis 2023; 744:1322–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li BY, Oh J, Young VB, Rao K, Wiens J. Using machine learning and the electronic health record to predict complicated Clostridium difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang G, Luo G, Lian H, Chen L, Wu W, Liu H. Application of deep learning in clinical settings for detecting and classifying malaria parasites in thin blood smears. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023; 10:ofad469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith KP, Kirby JE. Image analysis and artificial intelligence in infectious disease diagnostics. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26:1318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wagner G, Lukyanenko R, Paré G. Artificial intelligence and the conduct of literature reviews. J Inf Technol 2022; 37:209–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Branch-Elliman W, Elwy AR, Chambers DA. Embracing dynamic public health policy impacts in infectious diseases responses: leveraging implementation science to improve practice. Front Public Health 2023; 11:1207679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moehring RW, Phelan M, Lofgren E, et al. Development of a machine learning model using electronic health record data to identify antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e213460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. VA National Artificial Intelligence Institute . The Department of Veterans Affairs establishes a trustworthy AI framework. 2023. Available at: https://department.va.gov/ai/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2023/09/trustworth-framework.pdf. Accessed 27 November 2023.

- 18. Wong F, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Collins JJ. Leveraging artificial intelligence in the fight against infectious diseases. Science 2023; 381:164–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chang A, Chen JH. BSAC vanguard series: artificial intelligence and antibiotic stewardship. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022; 77:1216–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fitzpatrick F, Doherty A, Lacey G. Using artificial intelligence in infection prevention. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis 2020; 12:135–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gohil SK, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. 13. INSPIRE-ASP pneumonia trial: a 59 hospital cluster randomized evaluation of intelligent stewardship prompts to improve real-time empiric antibiotic selection versus routine antibiotic selection practices for patients with pneumonia. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8(Suppl 1):S9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Embi PJ. Algorithmovigilance-advancing methods to analyze and monitor artificial intelligence-driven health care for effectiveness and equity. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e214622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwartz IS, Link KE, Daneshjou R, Cortés-Penfield N. Black box warning: large language models and the future of infectious diseases consultation [manuscript published online ahead of print 16 November 2023]. Clin Infect Dis 2023. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maillard A, Micheli G, Lefevre L, et al. Can chatbot artificial intelligence replace infectious disease physicians in the management of bloodstream infections? A prospective cohort study [manuscript published online ahead of print 12 October 2023]. Clin Infect Dis 2023. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu X, Duan R, Ni J. Unveiling security, privacy, and ethical concerns of ChatGPT. J Inf Intell 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marks M, Haupt CE. AI chatbots, health privacy, and challenges to HIPAA compliance. JAMA 2023; 330:309–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brownstein JS, Rader B, Astley CM, Tian H. Advances in artificial intelligence for infectious-disease surveillance. N Engl J Med 2023; 388:1597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abbo LM, Vasiliu-Feltes I. Disrupting the infectious disease ecosystem in the digital precision health era innovations and converging emerging technologies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2023; 67:e0075123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Branch-Elliman W, Sundermann AJ, Wiens J, Shenoy ES. The future of automated infection detection: innovation to transform practice (part III/III). Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol 2023; 3:e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sundermann AJ, Chen J, Kumar P, et al. Whole-genome sequencing surveillance and machine learning of the electronic health record for enhanced healthcare outbreak detection. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 75:476–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ng PC, Spachos P, Gregori S, Plataniotis KN. Epidemic exposure tracking with wearables: a machine learning approach to contact tracing. IEEE Access 2022; 10:14134–48. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mermin-Bunnell K, Zhu Y, Hornback A, et al. Use of natural language processing of patient-initiated electronic health record messages to identify patients with COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6:e2322299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goodman KE, Heil EL, Claeys KC, Banoub M, Bork JT. Real-world antimicrobial stewardship experience in a large academic medical center: using statistical and machine learning approaches to identify intervention “hotspots” in an antibiotic audit and feedback program. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofac289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tran-The T, Heo E, Lim S, et al. Development of machine learning algorithms for scaling-up antibiotic stewardship. Int J Med Inform 2023; 181:105300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Perret J, Schmid A. Application of OpenAI GPT-4 for the retrospective detection of catheter-associated urinary tract infections in a fictitious and curated patient data set. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2023; 45:96–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wu JT, Shenoy ES, Carey EP, Alterovitz G, Kim MJ, Branch-Elliman W. ChatGPT: increasing accessibility for natural language processing in healthcare quality measurement. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2024; 45:9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee P, Bubeck S, Petro J. Benefits, limits, and risks of GPT-4 as an AI chatbot for medicine. N Engl J Med 2023; 388:1233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meskó B, Topol EJ. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. NPJ Digit Med 2023; 6:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Minssen T, Vayena E, Cohen IG. The challenges for regulating medical use of ChatGPT and other large language models. JAMA 2023; 330:315–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sahni NR, Carrus B. Artificial intelligence in U.S. health care delivery. N Engl J Med 2023; 389:348–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Agrawal A, Gans JS, Goldfarb A. Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence: prediction versus judgment. Inf Econ Policy 2019; 47:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Agrebi S, Larbi A. Chapter 18—Use of artificial intelligence in infectious diseases. In: Barh D, ed. Artificial intelligence in precision health. Academic Press, 2020:415–38. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ali T, Ahmed S, Aslam M. Artificial intelligence for antimicrobial resistance prediction: challenges and opportunities towards practical implementation. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023; 12:523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Agrawal A, Gans J, Goldfarb A. Power and prediction: the disruptive economics of artificial intelligence. Harvard Business Review Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cavallaro M, Moran E, Collyer B, McCarthy ND, Green C, Keeling MJ. Informing antimicrobial stewardship with explainable AI. PLoS Digit Health 2023; 2:e0000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stokes JM, Yang K, Swanson K, et al. A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell 2020; 180:688–702.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Berinato S. Data science and the art of persuasion. Harvard Business Review, 2019. Available at: https://hbr.org/2019/01/data-science-and-the-art-of-persuasion. Accessed 25 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cialdini RB. Harnessing the science of persuasion. Harvard Business Review, 2001. Available at: https://hbr.org/2001/10/harnessing-the-science-of-persuasion. Accessed 25 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Saint S, Kowalski CP, Banaszak-Holl J, Forman J, Damschroder L, Krein SL. How active resisters and organizational constipators affect health care-acquired infection prevention efforts. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2009; 35:239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reagan KA, Chan DM, Vanhoozer G, et al. Resistors and constipators: financial impact in an academic medical center, a mathematical model. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43:533–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Positive Deviance Collaborative. What is positive deviance? Available at: https://positivedeviance.org/. Accessed 4 May 2023.

- 52. Alzunitan MA, Edmond MB, Alsuhaibani MA, Samuelson RJ, Schweizer ML, Marra AR. Positive deviance in infection prevention and control: a systematic literature review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43:358–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zucker R. Why highly efficient leaders fail. Harvard Business Review, 2019. Available at: https://hbr.org/2019/02/why-highly-efficient-leaders-fail. Accessed 25 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Koval ML. Medscape infectious disease physician lifestyle, happiness & burnout report 2023: contentment amid stress. 2023. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-infectious-disease-6016081? icd=login_success_email_match_norm#1. Accessed 25 September 2023.

- 55. Smith TJG, Pryor R, Hota SS, Haessler SD, Deloney VM, Bearman G. Characterizing burnout among healthcare epidemiologists in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: a study of the SHEA Research Network. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol 2023; 3:e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bearman G, Hota SS, Haessler SD. Physician burnout and healthcare epidemiology: dual implications worthy of greater scrutiny. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020; 41:250–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mullin RA, Hota SS, Bearman G. Leading teams while exhausted: perspectives from healthcare epidemiology and beyond. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol 2023; 3:e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Duhigg C. What google learned from its quest to build the perfect team. The New York Times. 2016. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html. Accessed 25 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bearman G, Nori P. Implementing behavior change in healthcare epidemiology and antimicrobial stewardship: the worst that can happen is you fail. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol 2023; 3:e129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wu K, Wu E, Theodorou B, et al. Characterizing the clinical adoption of medical AI devices through U.S. insurance claims. NEJM AI 2023; 1. [Google Scholar]