Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to present the magnitude and determinants of awareness about refractive surgery among the adult Saudi population and recommend knowledge improvement.

Methods

This web-based cross-sectional study was conducted between June 2020 and May 2021 across various regions of Saudi Arabia on the adult Saudi population. A total of 11 close-ended questions regarding indication, contraindication, preparation and surgery procedures were asked. The awareness scores were grouped as ‘good’ (≥6) or ‘poor’ (≤5). Demographic and ocular parameters were associated with the outcomes.

Results

Of the 6,746 participants, 6,580 (response rate = 97.5%) completed the survey. The participation of younger women and older men was greater than their proportions in the population, while older women participated less than their proportion. Good awareness about refractive surgery was noted in 1,165 (17.7%; 95% confidence interval: 16.2–18.0) participants. Women (P <0.001), the 18–29 age group (P <0.001), residents of the central region of Saudi Arabia (P <0.001), health professionals (P <0.001), health sector students (P = 0.0004), people with myopia (P <0.001) and history of refractive surgery (P <0.001) were associated with good awareness. Women (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.5; P <0.001), health sector students (AOR = 1.57; P <0.001), and residents in the central region (AOR = 1.27; P <0.001) were independent predictors of awareness. Knowledge about contraindications for surgery was good in more than one-third of the participants. Of the 535 participants who underwent surgery in the past, 452 (84.5%) were satisfied with their outcomes.

Conclusion

Awareness of refractive surgeries is low in the adult Saudi population. Targeted counseling is recommended to improve the knowledge and acceptance of refractive surgery.

Keywords: Refractive Surgeries, Awareness, Survey, LASIK, Refractive Errors, Saudi Arabia

Advances in Knowledge

- The adult Saudi population in this study that showed a good level of awareness of refractive surgery to address refractive error and obtain spectacle-free functional normal vision was 17.7%.

- Participants were aware of when not to undergo refractive surgeries.

- Females, young adults, residents of central Saudi Arabia, those related to the health profession and those who were operated for refractive error in the past had better knowledge about refractive surgery.

Application to Patient Care

- Health promotion, campaigns and counselling about refractive surgery as an alternative to achieve spectacle-free vision of the adult Saudi population is needed.

- Campaigns aimed at increasing awareness about refractive surgery should target males, older adults and residents of regions other than Riyadh.

- The selection of client-friendly modes like social media and mass media will have a wider reach of health messages.

Uncorrected refractive error is one of the leading causes of blindness and vision impairment.1 Globally, the median effective refractive error (RE) coverage in 2020 was 35.7% at the 6/12 visual acuity threshold and 65.4% at the 6/18 threshold.2 All efforts should thus be directed towards identifying and addressing the barriers to the uptake of visual aids. These aids include spectacles, contact lenses (CLs) and refractive surgeries.3

The prevalence of REs was found to be as high as 78% among the Saudi adult population.4 Of the identified adults with REs, nearly 75% opted to not wear corrective visual aids. A meta-analysis of 23 international studies determined the overall compliance with spectacle wearing at only 40.1%.5 Therefore, alternatives to spectacles are likely to be favoured by the Saudi adult population with REs.

A survey of CL users in Saudi Arabia revealed that only half of the respondents used CLs for RE correction and 23% had not visited an ophthalmologist for their CL-related problems.6 The standard of maintaining ocular and facial hygiene to avoid severe complications from wearing CLs was poor among Saudi CL users.7 Contact lens wearers obtained CLs from optical shops (51%), beauty salons (38%) and pharmacies (11%), with 37.8% of them not consulting with their eye practitioners to get the CLs.8 Thus, CL usage in Saudi Arabia could have a negative impact if complications due to uncontrolled CL dispensing practices continue. In one study, 68% of current visual aids users preferred to opt for refractive surgeries, with cost not being a barrier; rather, fear and lack of information about these surgeries were the main reasons for apprehension among the users.9

Globally, the annual number of refractive surgeries performed is likely to increase from 3.6 million to 5.8 million. The satisfaction level among those operated on in the USA was as high as 98.7%.10,11 Furthermore, practicing refractive surgeons in Saudi Arabia have revealed that services are improving with modern tools and experienced surgeons.12 The uptake of refractive surgery also depends on awareness among persons with REs and family members who decide on surgeries. A study in northern Saudi Arabia reported that 16% of adult participants had undergone refractive surgery and fear of complications was the main reason for not opting for surgery among those surveyed.13 A study of 80 art students in India revealed that 70% had inadequate knowledge about refractive surgeries to correct REs.14 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, research on the determinants of awareness about refractive surgeries has not been conducted.

This study presents the magnitude and determinants of awareness about refractive surgeries including laser procedures among the Saudi adult population in 2021. Based on the findings, strategies to improve this population’s knowledge and increase the uptake of refractive surgeries in Saudi Arabia are recommended.

Methods

This cross-sectional web-based survey was held across various regions of Saudi Arabia from June 2020 to May 2021. The study population consisted of Saudi adults aged 18 and above years. It was assumed that the level of awareness about refractive surgeries was poor in 70% of the adult population, as noted by Goyal.14 To achieve a 95% confidence interval (CI) and 5% acceptable error margin with a clustering effect of 2, 650 participants from each subgroup needed to be randomly selected. Thus, to represent 5 regions of Saudi Arabia and both genders, at least 6,500 participants were needed. OpenEpi software’s statistical calculator (Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) was used to calculate the sample size for this cross-sectional study.15

Google Forms (Google, Mountain View, California, USA) was used to collect the participants’ responses.16 University websites, social media and newspapers were used to inform the Saudi adult population about this survey and invite them to participate. The demographic data collected included age group, gender, area of residence, education, employment, type of students, type of employment, monthly income and current refractive status. Data on participants’ history of refractive surgery, type of visual aids used and type of refractive error were also collected. The 11 awareness-related questions were grouped as indications (4 questions), contraindications (3 questions), preparation for surgery (2 questions) and surgical procedures (2 questions); 3 senior ophthalmologists responded to the questions in the pilot test. The responses that all 3 deemed correct were used as the gold standard for analysing the participants’ responses. A sample of 20 volunteers’ responses in the pilot test was reviewed to validate the data collection method (α = 0.832). A score of 1 point was awarded for each correct response, while no points were awarded for incorrect answers or selection of ‘I don’t know’. The total awareness score was further grouped as ‘good’ if ≥6 or ‘poor’ if ≤5 [Supplementary Table 1].

The collected data were exported from Google Forms (Google) to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA). Only the surveys that were fully answered were included for analysis. The participation rate was calculated as completed questionnaire/total participation in the survey multiplied by 100. After a consistency check and the removal of duplicates, if any, the data were transferred to a spreadsheet in Statistical Package for Social Studies (SPSS), Version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). The qualitative data were presented as frequencies and percentage proportions. The outcome variables and state of awareness (‘good’/‘poor’) among the participants were associated with different variables based on an estimated odds ratio, its 95% CI and two-sided P values. The variables with significant association with awareness level were included in a binary regression model using the step-out method to study variable interaction. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR), its 95% CI and the P values were presented as significant predictors of the level of awareness regarding refractive surgeries.

The Imam Muhammad bin Saud Research Ethics Committee in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia approved the study (95–2020). Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants, and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were strictly followed throughout the research stages.

Results

A total of 6,746 participants enrolled in this web-based survey. Of them, 6,580 (response rate = 97.5%) completed the survey and had their responses analyzed. The participation of younger women and older men was greater than their proportions in the population, while older women participated less than their proportion in the population [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Population proportion of Saudi adults (2017 projections) and examined sample for the survey on awareness of refractive surgery.

| Age group in years | n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Census population | Surveyed sample | Census population | Surveyed sample | |

| 18–29 | 2,896,778 (50.7) | 1,237 (51.4) | 2,755,885 (50.3) | 3,106 (74.4) |

| 30–39 | 1,628,169 (28.5) | 337 (14.0) | 1,593,601 (29.1) | 403 (9.7) |

| ≥40 | 1,185,073 (20.8) | 831 (34.6) | 1,131,324 (20.6) | 666 (16.0) |

| Total | 5,710,020 (100.0) | 2,405 (100.0) | 5,480,810 (100.0) | 4,175 (100.0) |

Table 2.

Profile of adult Saudi population participating in survey on awareness about refractive surgeries (N = 6,580)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 2,405 (36.6) |

| Female | 4,175 (63.4) |

| Age groups in years | |

| 18–29 | 4,343 (66.0) |

| 30–39 | 740 (11.2) |

| ≥40 | 1,497 (22.8) |

| Regions of Saudi Arabia | |

| Central | 1,125 (17.1) |

| Eastern | 1,127 (17.1) |

| Northern | 1,200 (18.2) |

| Western | 1,167 (17.7) |

| Southern | 910 (13.8) |

| Undisclosed | 1,051 (16.0) |

| Education | |

| Completed school | 1,117 (17.0) |

| Graduate | 5,150 (78.3) |

| Postgraduate | 313 (4.7) |

| Occupation | |

| Student | 3,867 (58.8) |

| Employed | 1,662 (25.3) |

| Other | 1,051 (16.0) |

| Student type | |

| Health sector | 701 (18.1) |

| Other | 3,166 (81.9) |

| Profession | |

| Health related | 91 (5.5) |

| Other | 1,571 (94.5) |

| Monthly income in USD | |

| <1,333 | 3,192 (48.5) |

| 1,333–2,667 | 1,122 (17.1) |

| 2,668–4,000 | 1,011 (15.4) |

| >4,000 | 204 (3.1) |

| Not applicable | 1,051 (16.0) |

USD = United States Dollar

Women and the 18–29 years age group constituted 66.0% of the total participants; 16.0% of the participants opted not to disclose their area of residence. The graduates or postgraduates comprised 83% of the surveyed participants. Fifty-eight percent of the participants were college students. Very few health professionals and health sector students participated in the study. 48% of the participants had a monthly income of less than USD 1,300.

A good level of awareness about refractive surgery was noted in 1,165 (17.7%, 95% CI: 16.2–18.0) Saudi adult participants. However, the level of awareness about refractive surgery was less than desired (‘poor’) in 5,415 (82.3%) participants.

The participants’ demographics and other determinants were associated with the level of awareness about refractive surgery. Female gender (P <0.001), the 18–29 age group (P <0.001), residence in the central region of Saudi Arabia (P <0.001), health professionals (P <0.001), health sector students (P = 0.0004), myopia (P <0.001) and history of refractive surgery (P <0.001) were significantly associated with good awareness about refractive surgery [Table 3].

Table 3.

Refractive error based on the participants’ responses (N = 6,580).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Type of refractive error | |

| Myopia | 2,004 (30.5) |

| Hyperopia | 320 (4.9) |

| Astigmatism | 764 (11.6) |

| Not known | 1,053 (16.0) |

| No refractive error | 2,439 (37.5) |

| Device used for refractive error correction | |

| Spectacles | 1,623 (24.7) |

| Contact lens | 116 (1.8) |

| Contact lens and spectacles (Both) | 554 (8.4) |

| Surgery | 202 (3.1) |

| None | 462 (7.0) |

| Not applicable | 3,623 (55.1) |

| Past refractive surgery | |

| Yes | 535 (8.1) |

| No | 6,045 (91.9) |

Regression analysis was used to predict the level of awareness among the Saudi adult population. Women (AOR = 1.5; P <0.001), health sector students (AOR = 1.57; P <0.001) and residents of the central region of Saudi Arabia (AOR = 1.27; P < 0.001) were independent predictors of the level of awareness about refractive surgery among Saudi adults [Tables 4 and 5].

Table 4.

Factors associated with awareness about refractive surgery among adult Saudi population (N = 6,580).

| Characteristic | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Good level of awareness (n = 1,165) | Poor level of awareness (n = 5,414) | Test statistic | |

| Gender | OR = 0.5, 95% CI: 0.4–0.6; P <0.001 | ||

| Male | 283 (24.3) | 2,122 (39.2) | |

| Female | 882 (75.7) | 3,293 (60.8) | |

| Age group in years | X2 = 36.5, Df = 5; P <0.001 | ||

| 18–29 | 843 (72.4) | 3,500 (64.6) | |

| 30–39 | 139 (11.9) | 601 (11.1) | |

| ≥40 | 183 (15.7) | 1,314 (24.3) | |

| Region | X2 = 21, Df = 4; P <0.001 | ||

| Central | 263 (22.6) | 862 (15.9) | |

| Eastern | 174 (14.9) | 953 (17.6) | |

| Northern | 200 (17.2) | 1,000 (18.5) | |

| Western | 186 (16.0) | 981 (18.1) | |

| Southern | 135 (11.6) | 775 (14.3) | |

| Education | X2 = 0.01, Df = 2; P = 0.93 | ||

| School completed | 201 (17.3) | 916 (16.9) | |

| Graduate | 906 (77.8) | 4,244 (78.4) | |

| Postgraduate | 58 (5.0) | 255 (4.7) | |

| Occupation | X2 = 3.4, Df = 2; P =0.06 | ||

| Student | 748 (64.2) | 3,119 (57.6) | |

| Employed | 210 (18.0) | 1,452 (26.8) | |

| Other | 207 (17.8) | 844 (15.6) | |

| Profession | OR = 4.2, 95% CI: 2.7–6.7; P <0.001 | ||

| Health related | 32 (2.7) | 59 (1.1) | |

| Other | 178 (15.3) | 1,393 (25.7) | |

| Student type | OR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.2–1.7; P = 0.0004 | ||

| Health sector | 170 (14.6) | 531 (9.8) | |

| Other | 578 (49.6) | 2,588 (47.8) | |

| Monthly income in USD | X2 = 5.7, Df = 3; P = 0.02 | ||

| <1,333 | 596 (51.2) | 2,596 (47.9) | |

| 1,333–2,667 | 175 (15.0) | 947 (17.5) | |

| 2,668–4,000 | 145 (12.4) | 866 (16.0) | |

| >4,000 | 42 (3.6) | 162 (3.0) | |

| Refractive error | X2 = 28, Df = 4; P <0.001 | ||

| Myopia | 422 (36.2) | 1,582 (29.2) | |

| Hyperopia | 58 (5.0) | 262 (4.8) | |

| Astigmatism | 127 (10.9) | 637 (11.8) | |

| Not known | 207 (17.8) | 846 (15.6) | |

| No refractive error | 351 (30.1) | 2,088 (38.6) | |

| Device used for refractive error correction | X2 = 3.2, Df = 5; P = 0.07 | ||

| Spectacles | 268 (23.0) | 1,355 (25.0) | |

| Contact lens | 27 (2.3) | 89 (1.6) | |

| Contact lens and spectacles (Both) | 142 (12.2) | 412 (7.6) | |

| Surgery | 61 (5.2) | 141 (2.6) | |

| None | 89 (7.6) | 373 (6.9) | |

| Not applicable | 578 (49.6) | 3,044 (56.2) | |

| Past refractive surgery | OR = 2.16, 95% CI: 1.78–2.63; P <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 161 (13.8) | 374 (6.9) | |

| No | 1,004 (86.2) | 5,041 (93.1) | |

USD = United States Dollar

Table 5.

Predictors of awareness about refractive surgeries among adult Saudi population.

| Characteristic | Odds ratio | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | −0.792 | 0.453 | 0.37–0.56 | <0.001 |

| Female | 1 | 1 | ||

| Region | ||||

| Central | 0.211 | 1.24 | 0.94–1.63 | 0.138 |

| Eastern | −0.135 | 0.87 | 0.67–1.16 | 0.351 |

| Northern | −0.068 | 0.93 | 0.7–1.25 | 0.645 |

| Western | −0.311 | 0.73 | 0.56–0.97 | 0.028 |

| Southern | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Student type | ||||

| Health sector | 0.452 | 1.57 | 1.26–1.96 | <0.001 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | ||

| Constant | −1.252 | 0.286 | <0.001 | |

Knowledge about the indication of refractive surgeries was good among 834 (12.7%) participants, and knowledge about the contraindication of refractive surgeries was good among 2,475 (37.6%) participants. Furthermore, knowledge about preparation for surgery and surgical procedures was good in 1,089 (16.6%) and 778 (11.8%) participants, respectively.

Among the 535 participants who had undergone refractive surgery in the past, 452 (84.5%) were satisfied with their outcomes. Of them, 428 (80%) expressed a desire to recommend surgery to others, 38 (7.1%) declined to recommend it and 69 (12.9%) were ambivalent.

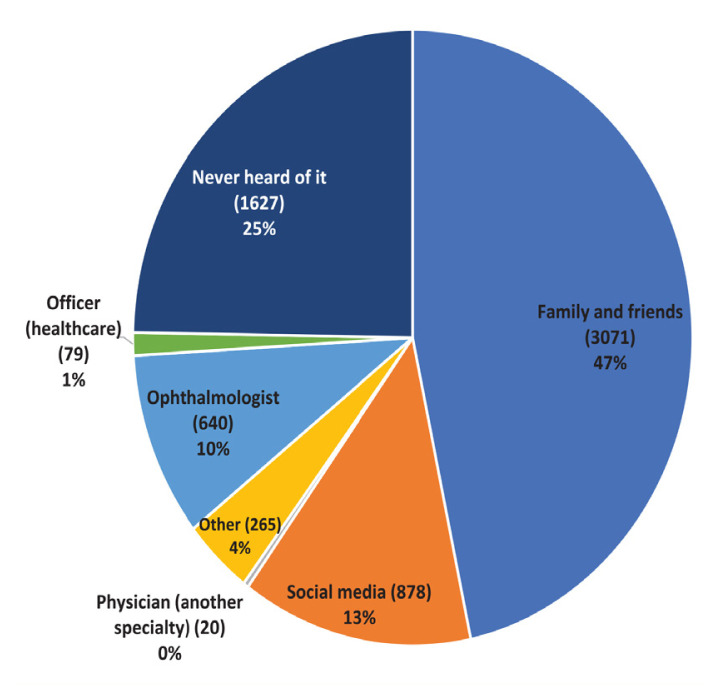

The source of information about refractive surgery among the participants mainly included friends and relatives (n = 3,071, 46.7%), social media (n = 878, 13.3%) and ophthalmologists (n = 640, 9.7%). As many as 1,627 (24.7%) had not heard about refractive surgery for correcting refractive errors [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Sources of information about refractive surgeries among the Saudi adult population participating in a web-based survey (N = 6,580).

Discussion

A total of 1 in 6 adult participants had a good level of awareness about refractive surgery. Awareness was significantly better among females, young adults, residents of the central region of Saudi Arabia, health sector students, and those who had undergone refractive surgery in the past. Also, knowledge about contraindications for surgery was good in 33% of participants. Among those who had undergone refractive surgery in the past, most were satisfied with the outcome and would recommend it to others. Word of mouth, social media and ophthalmologists’ advice were the main sources of knowledge about refractive surgery in the Saudi adult population.

The sample size was large enough to allow for comparison of the outcomes in the population’s subgroups. Due to Saudi Arabia’s $23,586 gross domestic product per capita in 2021, which is very high compared to many developing countries, the Saudi adult population is unique.17 Additionally, health services, including refractive surgeries at government eye hospitals and university hospitals, are free of cost for Saudi nationals. Thus, the cost may not be a major barrier to undergoing refractive surgery. In 2019, 80.7% of the population in Saudi Arabia used a smartphone, and 61% of women and 54% of men in Saudi Arabia owned a computer.18 Furthermore, there were 40.2 million mobile connections in Saudi Arabia in January 2020.19 Access to knowledge through digital and mass media is easy and widespread. Therefore, the low level of knowledge about refractive surgery in a population that is tech-savvy and has access to digital devices such as smartphones and computers is concerning. It indicates a need for caregivers and professionals involved in refractive surgeries to further the efforts to provide the necessary information to the population to improve the uptake of the surgeries and enable patients to make informed decisions to effectively address REs.

Among the current study’s participants, 17% had a good level of awareness about refractive surgery. In a study in Nigeria, more than half of the participants with REs were aware of refractive surgery as a substitute for wearing spectacles.20 A survey of medical students in Pakistan reported that three-fourths of the participants had heard about refractive surgery to correct REs, but only 33% were willing to undergo the procedure due to a lack of knowledge and fear of outcomes.21 Thus, it seems that knowledge about refractive surgery as a substitute for conventional visual aids is greater among those with REs and those in the medical field. However, the general population continues to have limited knowledge about refractive surgery. This seems probable, considering that two-thirds of the Saudi adult population of Makkah had a low level of knowledge about cataract surgery.22 A different survey conducted in Al Baha in the southern region of Saudi Arabia indicated that only 47% of the Saudi adult population knew about cataract surgery as a means of restoring vision in eyes with cataracts.23 Efforts to increase awareness may be implemented in stages using suitable tools to reach vulnerable populations.

Awareness about refractive surgery was significantly better among the Saudi adult female population of the current study. One should note the overrepresentation of young adult women in the present study; older women, especially those residing outside major cities, are less likely to be represented in the study, and they may be less aware of health issues such as refractive surgeries. Therefore, gender differences in awareness noted in the present study should be carefully interpreted when extrapolating to the entire older adult population of Saudi Arabia. Nevertheless, gender differences in awareness showed better knowledge among female than male students, residents of Riyadh compared to other regions, and those aged 18–32 years compared to >33 years of age. As many as 64% preferred surgery as a mode for correcting REs.9 A study showed that 95% of female Saudi students used social media for social interaction and research on topics of interest.24 While preparing health education to increase awareness among Saudi adults, a gender-specific approach is recommended to create a better impact.

Knowledge of refractive surgery was better among physicians and health sector students, compared to the study’s other participants. Knowledge about and willingness to undergo refractive surgery were similarly high among medical students with RE in western Saudi Arabia. The authors further recommend introducing refractive surgeries to medical students during their ophthalmology rotations.25

There was a wide variation in awareness among the participants from each of the 5 regions of Saudi Arabia. The central region, which mainly includes Riyadh, comprises several education centres, and professionals working there had better awareness. The southern region, on the other hand, had noticeably low awareness. Regional disparity in eye care services in Saudi Arabia, especially for refractive surgeries, could explain these regional variations.26

Participants with myopia had significantly better knowledge about refractive surgeries. Refractive surgeries are mostly performed to correct myopia, which likely explains the high level of awareness among myopic participants.27 However, a study by Alghamdi et al. showed there was no significant difference in the level of awareness by type of RE.23

Significant differences in awareness among the young adult participants compared to the middle-aged participants were noted. Since most of the participants were young students, they most probably had better access to social media and medical information compared to the older population.

The participants who had undergone refractive surgery had significantly better awareness of the different components of refractive surgeries. Informed consent obtained before surgery could be responsible for this differential awareness. This was also noted for patients undergoing cataract surgeries.28 This difference in awareness reflects the impact of the pre-surgery counselling on refractive surgery being carried out in ophthalmic services in Saudi Arabia. This also suggests that patient-to-patient dissipation of knowledge about interventions for addressing visual impairment and offering spectacle-free vision could have better success.

Almost one-fourth (24.7%) of the participants had never heard of refractive surgery. There is huge potential to increase the knowledge and awareness about this subject among the general Saudi adult population. The sources of information noted in the current study’s population differ from those in the study by Alduraywish et al.29 The authors noted that doctors and pharmacists, as well as the internet, were the main sources of health information, while social media was not commonly used for seeking health knowledge.29 The majority of the current study’s participants were young, and all participation in the study was through Google Forms (Google); therefore, extrapolation of survey outcomes about awareness of refractive surgery as a mode of achieving spectacle-free vision to the general population should be done with caution.

Despite those who underwent refractive surgery in the past being satisfied with their outcomes and their desire to recommend the surgery to others being above 80%, these figures are lower than those reported in a systematic review by the Canadian Drug Agency.30 Alsabaani et al. noted that only 70% of the ophthalmologist participants who underwent refractive surgery in the past were satisfied with their outcomes.31 Thus, studies on quality of life and satisfaction after refractive surgeries are recommended and could be an integral part of a surgical audit of these surgeries.

Although increasing the general population’s awareness of refractive surgeries is desired, it may not be possible given the priority of several other health ailments in Saudi society. In a targeted approach focusing on the adolescent population with REs and those seeking help from health services with a desire for spectacles, CL-free vision may be selected for counselling to raise awareness about this topic. If prospective clients for refractive surgeries are given evidence of success and recommendations from those who had undergone refractive surgery, a wider audience may be reached and a better impact produced. Forming social media groups of those who underwent refractive surgery could be an effective approach to providing relevant information to potential candidates.

This study had some limitations. Given the survey’s web-based approach, the non-random selection of participants could be skewed towards the computer-literate Saudi adult population, and extrapolation of the study outcomes to the entire population should therefore be done with caution. However, the study outcomes are useful to refractive surgeons because the educated young adult Saudi population is their main potential client for increasing uptake of this intervention to correct REs.

Conclusion

A survey on health issues with a large sample size distributed across all regions of Saudi Arabia provided insight into the awareness level of Saudi adults regarding refractive surgeries. This is a relatively new modality of addressing REs to attain the desired goal of spectacle-free vision in Saudi Arabia, where the climate is mostly hot and dry and, consequently, unsuitable for CL usage. With increasing demand, a rising number of corneal surgeries and a growing industry providing state-of-the-art medical tools in Saudi Arabia, efforts need to be increased to improve awareness of refractive surgeries among the population so that they can make evidence-based medical decisions. A targeted approach and focus on poor areas of awareness on this topic may be a good strategy.

The young adult population is more aware of refractive surgery as an option to address REs and obtain the spectacle-free normal functional vision. Females, young adults, residents of the central region of Saudi Arabia, health sector students and those with a history of surgery for REs in the past had better awareness of refractive surgeries than the rest of the population.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION: RAH, DAE, AA and SAR conceptualized and designed the study. SAK, NAQ, YAD, JAN, DAD and SAR collected the data. All authors analysed the data. RAH, DAE, AA and SAR drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

FUNDING: No funding was received for this study.

References

- 1.Burton MJ, Ramke J, Marques AP, Bourne RR, Congdon N, Jones I, et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on global eye health: Vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e489–551. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30488-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resolution WHA74(12) Integrated people-centred eye care, including preventable vision impairment and blindness. [Accessed: Sep 2023]. From: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA74/A74(12)-en.pdf.

- 3.Evans JR, Lawrenson JG, Ramke J, Virgili G, Gordon I, Lingham G, et al. Identification and critical appraisal of evidence for interventions for refractive error to support the development of the WHO package of eye care interventions: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Ophthalmic Physiol Op. 2022;42:526–33. doi: 10.1111/opo.12963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almudhaiyan T, Alhamzah A, AlShareef M, Alrasheed A, Jaffar R, Alluhidan A, et al. The prevalence of refractive errors among Saudi adults in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2020;34:30–4. doi: 10.4103/1319-4534.301297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhirar N, Dudeja S, Duggal M, Gupta PC, Jaiswal N, Singh M, et al. Compliance to spectacle use in children with refractive errors—A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20:71. doi: 10.1186/s12886-020-01345-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alzahrani O, Alshehri FA, Alali AO, Alzahrani OH, Alzahrani ZA, AlZahrani A, et al. Contact lens practices and knowledge of complications and its association with refractive error in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2021;13:e12786. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alhumaidi RA, Yousef KH. Impact of using contact lenses with hygiene rules in Saudi Arabia. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2018;72:5313–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abahussin M, AlAnazi M, Ogbuehi KC, Osuagwu UL. Prevalence, use and sale of contact lenses in Saudi Arabia: Survey on university women and non-ophthalmic stores. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014;37:185–90. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeried FM, Alnehmi DA, Osuagwu UL. A survey on knowledge and attitude of Saudi female students toward refractive correction. Clin Exp Optom. 2020;103:184–91. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Market Scope. Refractive surgery to grow 9.6 % a year through 2025, despite COVID-19. [Accessed: Sep 2023]. From: https://eyewire.news/articles/market-scope-refractive-surgery-to-grow-9-6-a-year-through-2025-despite-covid-19/?c4src=article:infinite-scroll.

- 11.Packer M. Refractive surgery current status: Expanding options. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2022;4:231–2. doi: 10.1080/17469899.2022.2108405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alghamdi AS, AlGethami RA, Almalki NA, Al-Amri AM. The preferences and practices regarding refractive surgeries among Saudi Ophthalmology Society members. Saudi J Health Sci. 2022;11:110. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alamri AM, Almutairi BA, Asiri FN, Alshehri MB, Rassam LA, Thalibah AM. Awareness and attitude toward refractive error surgery and other correction methods in Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia: A cross sectional study. Bahrain Med Bull. 2022;44:1000–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goyal MMK. Effectiveness of structured teaching programme on knowledge regarding LASIK eye surgery among the students in arts college. Int J Innov Res Adv Stud. 2016;3:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open source epidemiologic statistics for public health, version. [Accessed: Sep 2023]. From: www.OpenEpi.com.

- 16.Google. Get insights quickly, with Google Forms. [Accessed: Sep 2023]. From: https://www.google.com/forms/

- 17.Macrotrends. Saudi Arabia GDP per capita 1968–2022. [Accessed: Sep 2023.]. From: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/SAU/saudi-arabia/gdp-per-capita.

- 18.Statista. Society demographic. [Accessed: Sep 2023]. From: https://www.statista.com/statistics/625436/smartphone-user-penetration-in-saudi-arabia/

- 19.Datareportal. Digital 2020. Saudi Arabia: [Accessed: Sep 2023]. From: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-saudi-arabia. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayanniyi AA, Olatunji FO, Hassan RY, Adekoya BJ, Monsudi KF, Jamda AM. Awareness and attitude of spectacle wearers to alternatives to corrective eyeglasses. Asian J Ophthalmol. 2014;13:86–94. doi: 10.35119/asjoo.v13i3.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siddiqui SA, Ramzan MA, Sheroze MW, Jamal K, Batool R, Batool SK. Knowledge, attitude and practices among undergraduate medical students regarding surgical correction of refractive errors; A cross-sectional study. Ophthalmol Res Int J. 2022;16:1–6. doi: 10.9734/or/2022/v16i430239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magliyah MS, Nageeb MR, Abdulmannan DM, Badr HM, Hemmeish MM, Alotaibi WT, et al. Assessment of knowledge regarding cataract among Saudi adult population in Makkah city, Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2015;4:595–600. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2015.02022015121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alghamdi AH, Alamri A, Alzahrani RA, AMA, Alghamdi A, Saeed YS, et al. Awareness about causes and risk factors of cataract among general population of Albaha city. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2017;69:2703–10. doi: 10.12816/0042253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aljaad NH. The role of social communication tools in education from the Saudi female students’ perceptions. Int Educ Stud. 2016;9:194–202. doi: 10.5539/ies.v9n8p194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alhibshi N, Kamal Y, Aljohani L, Alsaeedi H, Ezzat S, Mandora N. Attitude toward refractive error surgery and other correction methods: A cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg. 2021;72:103104. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.103104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al Motowa S, Khandekar R, Al-Towerki A. Resources for eye care at secondary and tertiary level government institutions in Saudi Arabia. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21:142. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.129761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkinson JM, Cozine EW, Kahn AR. Refractive eye surgery: Helping patients make informed decisions about LASIK. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95:637–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tipotsch-Maca SM, Varsits RM, Ginzel C, Vecsei-Marlovits PV. Effect of a multimedia-assisted informed consent procedure on the information gain, satisfaction, and anxiety of cataract surgery patients. Journal Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alduraywish SA, Altamimi LA, Aldhuwayhi RA, AlZamil LR, Alzeghayer LY, Alsaleh FS, et al. Sources of health information and their impacts on medical knowledge perception among the Saudi Arabian population: Cross-sectional study. J Medical Internet Res. 2020;22:e14414. doi: 10.2196/14414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran K, Ryce A. Laser refractive surgery for vision correction: A review of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018. [Accessed: Sep 2023]. From: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532537/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alsabaani N, Alshehri MS, AlFlan MA, Awadalla NJ. Prevalence of laser refractive surgery among ophthalmologists in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2020;34:116–9. doi: 10.4103/1319-4534.305043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.