Abstract

Crescentic glomerulonephritis has been associated with several solid tumour malignancies. Only a few cases of nephropathy have been reported in association with tubo-ovarian/peritoneal malignancies. We report a 55-year-old female patient who presented to a tertiary care centre, Muscat, Oman, in 2022. She developed combined immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis and pauci-immune necrotising crescentic vasculitis simultaneously with the diagnosis of tubo-ovarian/peritoneal cancer. The baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 13 mL/min. The patient received two doses of rituximab and three doses of pulse corticosteroids, leading to significant improvement in renal function and the disappearance of her proteinuria. The eGFR improved to >60mL/min; her proteinuria gradually resolved after 10 weeks of treatment. She was then given a combination chemotherapy treatment for tubo-ovarian/peritoneal cancer leading to a normalisation of her CA-125 after three months of therapy.

Keywords: Peritoneal Neoplasm, Glomerulonephritis, Vasculitis, Chemotherapy, Case Report, Oman

Glomerulopathy in the field of cancer was first described in 1922.1 Glomerulonephritis has been reported in patients with solid tumours, and only a few cases have been reported in patients with tubo-ovarian/peritoneal cancer.2 The most common form of secondary glomerulonephritis is membranous nephropathy (MN), which is most commonly presented as nephrotic syndrome. The prevalence of malignancy with MN ranges from 1–22%.3 The glomerular lesions are considered paraneoplastic; however, the exact pathogenesis remains unclear in most cases. Renal impairment is a limiting factor in the prescription of chemotherapy, especially nephrotoxic agents, and thus can compromise the survival of patients. This case report describes a patient diagnosed with metastatic tubo-ovarian/peritoneal cancer and severe acute kidney injury due to crescentic glomerulonephritis.

Case Report

A 55-year-old female patient was hospitalised at a tertiary care centre, Muscat, Oman, in 2022 for epigastric pain, weight loss, abdominal distension and poor oral intake. She had a past medical history of hypertension (treated with amlodipine) and hypothyroidism (treated with levothyroxine replacement). Approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, the patient complained of abdominal pain and distention with abdominal mass in the imaging; she had undergone a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy surgery. The postoperative histopathology report was consistent with serous cystadenoma with borderline malignancy. The postoperative CA-125 was carefully followed-up for one year after the surgery, however the patient then stopped attending follow-up appointments.

During the current presentation, positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan was done; the patient was found to have supraclavicular, mediastinal, paraaortic, iliac and inguinal lymph nodes with moderate pleural effusion and ascites. She underwent a cervical lymph node biopsy which was consistent with a new diagnosis of metastatic high-grade serous tubo-ovarian/peritoneal carcinoma: CK7, CA-125, P16 and ER were each positive (strong and diffuse), WT1 was positive and PR was negative. Her CA-125 was 1,056 KIU/L (normal range: 0–35 KIU/L). During her hospitalisation, she was found to have acute kidney injury (AKI), as she was found to have a serum creatinine of 217 μmol/L (normal range: 45–84 μmol/L) on presentation, and the serum urea was 10.9 mmol/L (normal range: 2.8–8.1 mmol/L). Her electrolytes were normal. The urine dipstick showed blood 3+, protein 1+ and positive leucocytes. Urine microscopy showed no casts or crystals. The urine culture showed significant growth of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli with >100,000 CFU. She was commenced on intravenous (IV) piperacillin/tazobactam antibiotic. However, she did not complete the course of antibiotics as she only had mild symptoms, her inflammatory markers were not raised, when the urine sample was taken. The patient had a urinary catheter but her renal functions declined slowly. She also was found to have nephrotic range proteinuria with a urine protein to creatinine ratio (UPCR) of 436 mg/mmol (normal range: less 15 mg/mmol) and urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR) of 312 mg/mmol (normal range: 0–3.5 mg/mmol). Serum creatinine increased to 257 μmol/L despite hydration and appropriate urinary tract infection treatment.

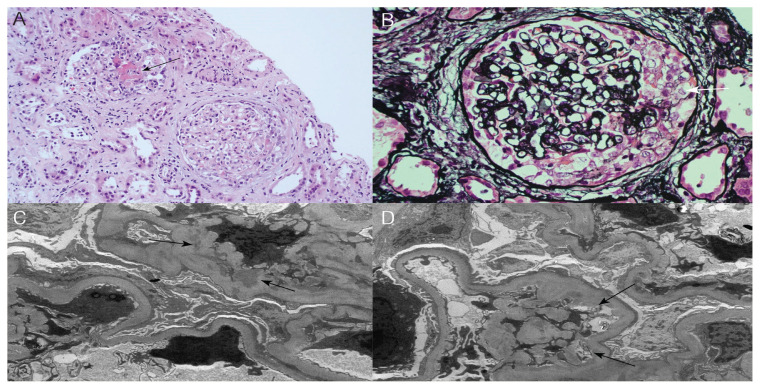

In light of her metastatic disease, AKI and heavy proteinuria, a thorough workup was performed to seek possible additional causes of the AKI. She had normal complements, negative hepatitis B, C and HIV serology. The serum protein electrophoresis and urine protein electrophoresis showed no abnormal serum protein bands or free light chains in the urine, respectively. The ANA was positive (titre 1:320) but negative anti-dsDNA antibody. All extractable nuclear antigens profile was negative. She had positive IgG antibodies for cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) but negative IgM for both viruses. The CMV, adenovirus and EBV tested negative on a polymerase chain reaction. Regarding her anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), the cytoplasmic and perinuclear forms were both positive; anti-proteinase 3 (PR3) was expected but myeloperoxidase (MPO) was borderline positive (titre = 24 U/mL; normal range: 0.00–20.00 U/mL). A clinical diagnosis of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis was made and a kidney biopsy was performed. The light microscopy report was consistent with crescentic glomerulonephritis (GN) with positive staining for IgG, IgA, C3, and C1q. Further histopathologic examination of the kidney tissue by electron microscopy revealed features consistent with immune complex-related GN with mesangial and subendothelial deposits electron microscope with extensive effacement of podocyte foot processes [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

A: Haematoxylin and eosin stain at ×200 magnification showing two glomeruli, one with fibrinoid necrosis (arrow) and the other with a cellular crescent. B: Jones stain at ×400 magnification showing a glomerulus with a cellular crescent (white arrow). C: Electron micrograph at ×12,000 magnification showing mesangial deposits (arrows). D: Electron micrograph at ×10,000 magnification showing subendothelial deposits (arrows). There is also extensive foot process effacement of podocytes.

The patient received a diagnosis of AKI secondary to crescentic GN, likely due to pauci-immune GN with concomitant immune complex-mediated GN. She received pulse IV methylprednisolone 500 mg daily for 3 days with appropriate calcium and vitamin D supplementations, then started on oral prednisone 30mg daily with a gradual taper over 8 weeks and was finally maintained on prednisone 5 mg daily. Additionally, she received IV rituximab 1g once weekly for 2 weeks. Rituximab infusions were without any anaphylaxis and infusion-related reactions. Two months later, the UPCR was 43 mg/mmol and UACR was 27.6 mg/mmol. Serum creatinine decreased to 98 umol/L and her eGFR was 50 mL/min. The remission of her proteinuria and significant improvement in her renal functions allowed for complete dose chemotherapy to be administered. She continued to show significant improvement in her renal functions (serum creatinine = 78 μmol/L, eGFR = 66.5 mL/min) and had a good response to chemotherapy (CA-125 = 30.2 KIU/L).

Verbal and written consent for publication purposes was taken from the patient.

Discussion

Historically solid tumour malignancies are pulmonary and gastric carcinomas which are most commonly associated with nephropathy.3 Membranoproliferative (MPGN) injury pattern has been described in association with solid tumours of the lung, kidney and stomach. Melanoma, breast carcinoma and thymoma have also been rarely reported in association with MPGN.3 Crescentic glomerulonephritis has been associated with several solid tumour malignancies.3 Only a few cases of nephropathy have been reported in association with tubo-ovarian/peritoneal malignancies.3 Nephropathy seems to occur irrespective of the tubo-ovarian/peritoneal tumour diagnosis, either during a relapse, 2 years after the first diagnosis or simultaneously.

The underlying glomerular lesions are reported to be membranous nephropathy, MPGN, AA amyloidosis, minimal change nephropathy and mesangial-proliferative glomerulonephritis.4 In the case of nephropathy associated with tubo-ovarian/peritoneal tumours, the treatment includes the administration of corticosteroids, surgery and chemotherapy.5 The current patient was not medically fit for initial debulking surgery as the disease was metastatic. Corticosteroids and rituximab were prescribed, resulting in complete nephropathy remission. Chemotherapy paclitaxel and carboplatin could be prescribed one month after her cancer diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of secondary nephropathy has not been clearly defined, but a cell-mediated immune response has been postulated; the secretion of a tumoural factor and/or the appropriate production of lymphokines by T-cells to suppress tumour growth could increase glomerular permeability.6 Clinically, it is difficult to differentiate primary MPGN from secondary MPGN associated with solid tumours. Lefaucheur et al. reported two risk factors differentiating paraneoplastic MPGN from primary MPGN.7 These include an age of over 65 years and a history of smoking 20 pack-years. The current patient was a non-smoker. Beck et al. identified circulating autoantibodies in most cases of adult primary MPGN.8 These autoantibodies were not found in cases of secondary MPGN.4 Lefaucheur et al. reported an increased number of inflammatory cells (more than 8 cells per glomeruli) on the kidney biopsy of patients with paraneoplastic MPGN compared to patients with primary MPGN.7

In the current case, biopsy showed mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting mainly of lymphocytes and a few neutrophils, which is consistent with the paraneoplastic origin of glomerulonephritis. Beck et al. explain the possible mechanisms, whereby solid tumours may be associated with MPGN.8 These include: (a) in situ immune-complex formation in which antibodies are formed against a tumour antigen that is localised in the subepithelial location or to podocyte antigen that is identical or similar to the tumour antigen; (b) tumour antigens may form circulating immune complexes that are subsequently trapped in glomerular capillaries; and (c) external factors such as infections with oncogenic viruses or altered immune function that can cause both the malignancy and MPGN.

The degree of proteinuria varies among patients with MPO vasculitis but is usually subnephrotic.9,10 Proteinuria of 1 g/day or less in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) is most likely the consequence of fibrosed glomeruli or tubular fibrosis in an individual who may or may not be in remission. Higher amounts of proteinuria, including proteinuria of more than 3 g/day, may be more common in patients who present later in the course of the disease and who have had previous necrotising glomerulonephritis.11 In the current patient, although the biopsy had a limited number of glomeruli, all glomeruli were intact and showed a mild increase in the mesangial matrix. All glomeruli showed cellular crescents with segmental fibrinoid necrosis in the tuft. There were no signs of endocapillary hypercellularity or thrombosis on light microscopy. Capillary walls showed normal thickness with no spikes or double contours. There was no tubular atrophy or interstitial fibrosis.

Further examination by electron microscopy revealed numerous small subendothelial deposits in the basement membrane with extensive effacement of podocyte foot processes with mesangial expansion and mesangial deposits. In some patients with AAV with high amounts of proteinuria, there may be a second concurrent glomerular disease or an atypical histologic pattern such as a glomerular immune-complex deposition.12,13 The nephrotic range proteinuria was most likely due to the extensive foot processes effacement found on histopathologic analysis of the renal biopsy.

Conclusion

This case report describes a patient diagnosed with tubo-ovarian/peritoneal cancer and associated with glomerulonephritis and vasculitis. Clinical history, physical examination, laboratory data and kidney biopsy led to the correct diagnosis. Corticosteroids combined with rituximab resulted in an improvement in renal functions, and the patient was able to receive a combination of chemotherapy paclitaxel and carboplatin for tubo-ovarian/peritoneal cancer. The treatment of paraneoplastic glomerulonephritis requires a multidisciplinary approach to monitor both cancer and glomerular lesions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr Mohammad Athar Khan for kindly reviewing the manuscript and giving useful suggestions to improve its quality.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION: AZ, AN and IAB managed the case. MR provided the details of histopathology. AZ, AN and MR drafted the manuscript. IAB critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Galloway J. Remarks on Hodgkin’s disease. Br Med J. 1922;2:1201–8.2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.3234.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyrier A, Delahousse M, Callard P, Rainfray M. Minimal change nephrotic syndrome revealing solid tumours. Nephron. 1992;61:220–3. doi: 10.1159/000186877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacchetta J, Juillard L, Cochat P, Droz JP. Paraneoplastic glomerular diseases and malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;70:39–58. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeroudi A, Kadikoy H, Gaber L, Ramanathan V, Frome A, Anwar N, et al. Profound nephrotic syndrome in a patient with ovarian teratoma. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2013;24:777–82. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.113883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salazar-Exaire D, Rodríguez A, Galindo-Rujana ME, Briones JC, Arenas-Osuna J, Rocha LM, et al. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with a mixed-cell germinal ovary tumour. Am J Nephrol. 2001;21:51–4. doi: 10.1159/000046219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnaper HW, Robson AM. Minimal change disease, focal glomerulosclerosis and related disorders. In: Schrier RW, Gottschalk CW, editors. Disease of the kidney. 5th ed. Boston, USA: Little, Brown and Company; 1992. pp. 1731–84. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefaucheur C, Stengel B, Nochy D, Martel P, Hill GS, Jacquot C, et al. Membranous nephropathy and cancer: epidemiologic evidence and determinants of high-risk cancer association. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1510–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck LH., Jr Membranous nephropathy and malignancy. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30:635–44. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, Hallahan CW, Lebovics RS, Travis WD, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: An analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savage CO, Winearls CG, Evans DJ, Rees AJ, Lockwood CM. Microscopic polyarteritis: Presentation, pathology and prognosis. Q J Med. 1985;56:467–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falk RJ, Merkel PA, King TE. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. [Accessed: Jan 2023]. From: https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/3117.

- 12.Haas M, Eustace JA. Immune complex deposits in ANCA-associated crescentic glomerulonephritis: A study of 126 cases. Kidney Int. 2004;65:2145–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann I, Regele H, Kain R, Birck R, Meisl FT. Glomerular immune deposits are associated with increased proteinuria in patients with ANCA-associated crescentic nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:524–31. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]