Abstract

Antibiotic resistance poses a major global health threat. Understanding emergence and dissemination of antibiotic resistance in environmental media is critical to the design of control strategies. Because antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) may be aerosolized from contaminated point sources and disseminated more widely in localized environments, we assessed ARGs in aerosols in urban La Paz, Bolivia, where wastewater flows in engineered surface water channels through the densely populated urban core. We quantified key ARGs and a mobile integron (MI) via ddPCR and E. coli as a fecal indicator by culture over two years during both the rainy and dry seasons in sites near wastewater flows. ARG targets represented major antibiotic groups—tetracyclines (tetA), fluoroquinolines (qnrB), and beta-lactams (blaTEM)—and an MI (intI1) represented the potential for mobility of genetic material. Most air samples (82%) had detectable targets above the experimentally determined LOD: most commonly blaTEM and intI1 (68% and 47% respectively) followed by tetA and qnrB (17% and 11% respectively). ARG and MI densities in positive air samples ranged from 1.3 × 101 to 6.6 × 104 gene copies/m3 air. Additionally, we detected culturable E. coli in the air (52% of samples <1 km from impacted surface waters) with an average density of 11 CFU/m3 in positive samples. We observed decreasing density of blaTEM with increasing distance up to 150 m from impacted surface waters. To our knowledge this is the first study conducting absolute quantification of ARGs near uncontained urban wastewater flows. Environments in close proximity these impacted waters experience locally elevated concentrations of ARGs, a possible concern for the emergence and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in cities with poor sanitation.

Keywords: bioaerosol, wastewater, E. coli, mobile integron, dissemination, antibiotic resistance

INTRODUCTION

Antibiotic resistance (AR) is a serious threat to global public health (World Health Organization, 2019). Increased antibiotic use coupled with poor antibiotic stewardship has contributed to the rapid development and dissemination of resistance in microbial communities and ultimately the emergence of AR as a global crisis (Davies and Davies, 2010; de J. Sosal et al., 2010; Nadimpalli et al., 2020; Pruden et al., 2006; Vikesland et al., 2017). Bacteria may inherit resistance, acquire resistance by horizontal gene transfer (Bennett, 2008) or may possess resistance genes conferring resistance indirectly (Allen et al., 2010). Genes that enable resistance to antimicrobials are known as antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs); genes that confer horizontal gene transfer ability or enable bacteria to take up resistance genes from the environment are known as mobile genetic elements (MGEs); and genes that are physically related to MGEs and enable the recombination and functional conversion of ARGs are known as mobile integrons (MIs) (Barraud et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2017; Mazel, 2006).

Although most studies have focused on AR development and dissemination in clinical settings (Schrag et al., 2004; Wellington et al., 2013), understanding the fate and transport of ARGs in environmental media is crucial to controlling AR, especially because the full extent of AR dispersion in the environment is still poorly characterized. Sabatino et al. recently detected AR residues in a highly diluted marine environment far from any waste sources, showcasing the potential for extensive AR circulation at large scales and subsequent introduction into previously susceptible microbial species and populations where rapid resistance development may occur (Sabatino et al., 2020). A noteworthy example of rapid resistance development is the class A enzyme of β-lactamase genes, Cefotaximase (CTX-M), which appears to have originated in the Kluyvera spp. bacteria that exist in both environmental media and the human gut (Cantón, 2009). From first identification in the 1980s to the 2000s, CTX-M had displaced other variants to become the dominant extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) in countries where testing occurred (Cantón et al., 2012; Cantón and Coque, 2006), with environmental transmission implicated. Closely related in the same class and often co-occurring with CTX-M are the Temoneira (TEM) enzyme and Pseudomonas extended resistance (PER) enzyme (Celenza et al., 2006; Shahid et al., 2011). The TEM enzyme, first discovered in E. coli isolated from a patient in Athens, Greece in 1965, has since expanded to include 223 new and novel variants from all over the globe (Rahman et al., 2018; Steward et al., 2000). Other clinically relevant ARGs of putative environmental heritage include the qnr gene family which confers mild resistance to fluoroquinolones. These genes, often found in Enterobacteraciae affecting humans, are thought to have originated in several aquatic species of bacteria like Shewanella algae and Vibrio splendidus. (Cantón, 2009; Lupo et al., 2012).

Evidence exists indicating prevalent ARGs and high potential for mobility in environments such as water runoff from animal feedlots; air, soils and groundwater surrounding wastewater and solid waste treatment plants; air surrounding poultry farms and markets; and other sites where concentrated fecal wastes exist (Chapin et al., 2005; de J. Sosal et al., 2010; Echeverria-Palencia et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2018, 2016; Gibbs et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018, 2016; Liu et al., 2012; McEachran et al., 2015; Neher et al., 2020; Pal et al., 2016; Rizzo et al., 2013; Sancheza et al., 2016; Stange and Tiehm, 2020; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2013). In a few high-income cities across the globe, a variety of ARGs have been detected and quantified in aerosols. Xie et al. (Xie et al., 2019) and Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2019) detected ARGs encoding resistance to β-lactams, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones in ambient urban air from Chinese cities. Echeverria-Palencia et al. (Echeverria-Palencia et al., 2017) detected aerosolized blaSHV, a β-lactam resistance-encoding ARG, in densities ranging from 0.2 to 600 gene copies (gc)/m3 in four cities in California. Less well characterized are sources and densities of specific ARGs of concern in cities in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs), however. These are settings where conditions favor AR emergence and transfer, and where uncontained, concentrated fecal waste may be present in densely populated areas with a high burden of enteric disease and poor antibiotic stewardship (Graham et al., 2018; Nadimpalli et al., 2020; Witte, 2000; Zhang et al., 2017). Even where wastewater treatment is successful in removing a majority of fecal bacteria in these settings, AR-bacteria can persist post-treatment (Kumar et al., 2020). Where sanitation systems are completely absent or operating ineffectively, ARG diversity and AR protein concentrations are even more likely to be widely disseminated in the environment (Pehrsson et al., 2016), presenting possible exposure risks to nearby populations.

We hypothesized that where urban wastewater flows are uncontained and open to the atmosphere, ARGs would be detectable and quantifiable in aerosols nearby. The absolute densities of specific ARGs of concern – necessary for developing mechanistic models for fate, transport, and exposure – remain a critical unknown in these settings. We further hypothesized that aerosolized ARGs would decrease with distance from potential sources. The city of La Paz, Bolivia, where wastewater is conveyed in open, engineered channels shared with surface water, provided an opportunity to test these hypotheses.

METHODS

Sample sites and collection.

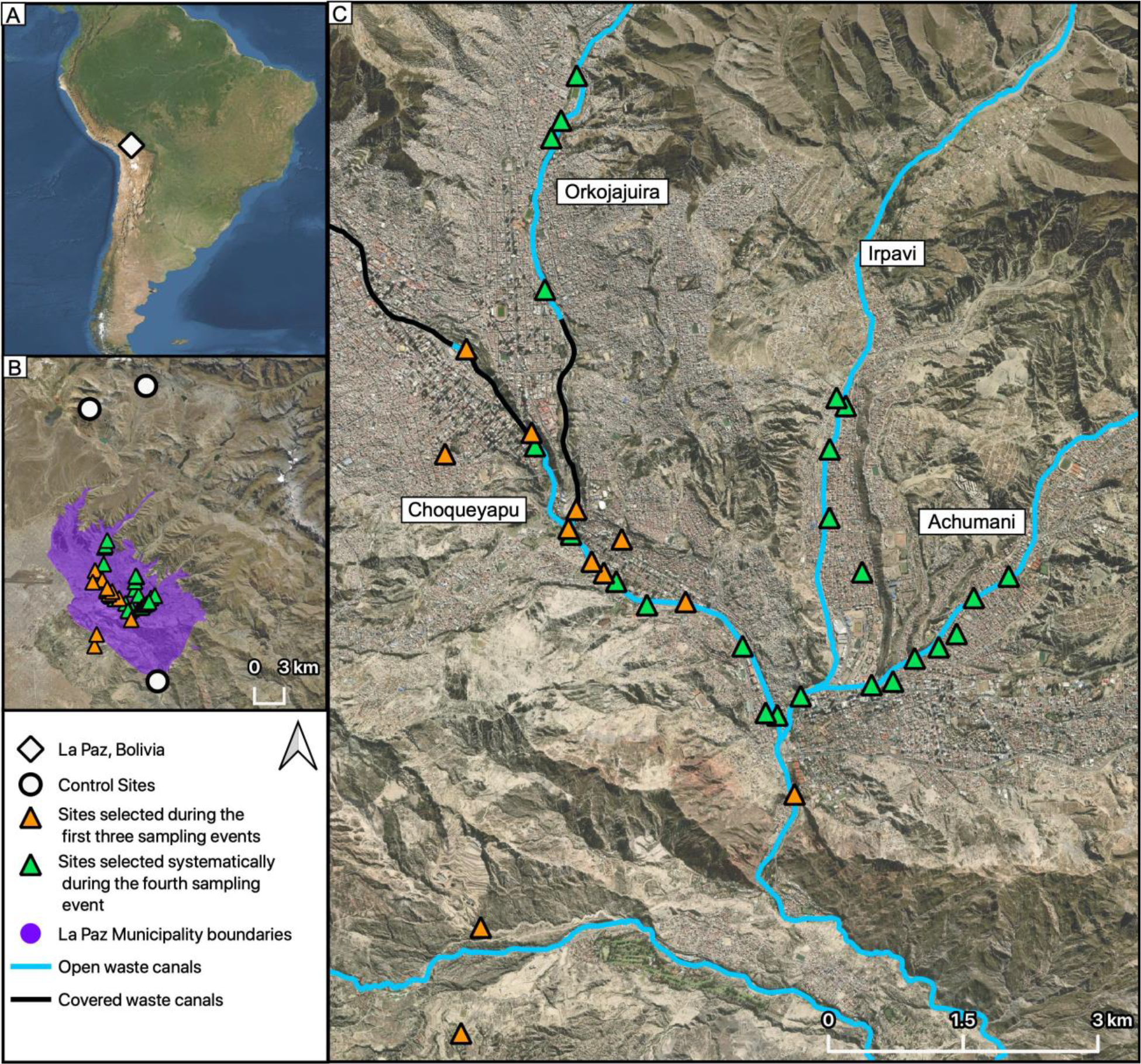

We collected samples during both the rainy (March) and dry (May-July) seasons in La Paz, Bolivia (March/2018, May-June/2018, March/2019, June-July/2019) where a network of rivers receives untreated sewage discharge, industry effluent, and stormwater runoff. Most of the waterway flows in a series of engineered channels (Alarcon Calderon, 1996; Poma et al., 2016) consisting of highly impacted surface waters, which we refer to here as open wastewater canals (OWCs). The main waterway, the Choqueyapu River, begins as a small stream at Pamapalarama, flowing south through central La Paz, home to 900,000 people (1900 persons/km2) (INE, 2018; Ohno, A; Marui, A; Castro, ES; Reyes, AA; Elio-Calvo, D; Kasitani, H; Ishii, Y; Yamaguchi, 1997). As it flows through the city, the Choqueyapu is joined by tangential tributaries including the Orkojahuira, Irpavi, and Achumani rivers (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Location of La Paz, Bolivia. (B) La Paz Municipality boundaries with all sampling sites and control sites. (C) Sampling locations in relation to covered and uncovered OWCs.

During the first three sampling events, we identified 13 sites along the Choqueyapu River meeting the following criteria: (1) proximity to OWCs, (2) accessible at ground level, and (3) unintrusive to residents or passers-by. We identified two control sites >1 km from known concentrated wastewaters or other contaminated sources: (1) Chacaltaya, a weather station and environmental observatory located at 5380 m in elevation and far from human habitation and (2) Pampalarama, a pristine site near the Choqueyapu headwaters. In a final sampling event (June-July 2019), we chose an expanded range of sites to further interrogate the spatial relationship of targets in relation to the OWCs, with particular attention to distances of 200 m or less from OWCs. We based selected sampling locations on the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) Global Digital Elevation Model (GDEM) version 2 data for the study area (NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Space Systems and Team, 2009) and a hydrographic model (ESRI Inc., 2019) in ArcGIS Version 10.7.1 to generate the major streamlines according to the topography for the La Paz metro area. Based on the four main OWCs, we randomly selected sites ≤ 200 m from the mid-point of OWCs and at least 150 m from the nearest other site. Given the diurnal cycles of atmospheric stability and the resulting impact on bioaerosol dissemination (Jacob, 1999; Jones and Harrison, 2004), we assessed the potential temporal associations of ARG densities in the air through sampling both in the morning and afternoon at each site.

Sample collection, culture, extraction, and analysis.

We used the Six-Stage Viable Andersen Cascade Impactor (ACI) with selective media in six partitioned chambers at a flow rate of approximately 28.5 L/min to assess viability of E. coli at a subset of sites (Andersen, 1958) (ACI, Thermo Scientific™, USA), as an indicator of aerosolized fecal material. We used AquaTest Medium (Sisco Research Laboratories PVT. LTD., India) to select for E. coli (Bain et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2020; Genter et al., 2019; Magro et al., 2014). We incubated plates overnight at 37°C. The limit of detection for the culture analysis was determined by dividing 1 colony-forming unit (CFU, the minimum count per plate) by the volume of air sampled.

To collect larger volumes for molecular analysis, we sampled for approximately 4 hours per sampling event using the ACD-200 BobCat Dry Filter Air Sampler (InnovaPrep, Drexel, MO, USA) with 52 mm electret filters and a flow rate of 150 L/min, to yield a total sample volume of 36 m3 of air per sample. We used a single-use wet foam carbon compressed elution kit (InnovaPrep, Drexel, MO, USA) to flush the filter following the manufacturer’s instructions, yielding approximately 6 mL of liquid. In a subset of locations, we collected 150 mL grab samples of OWC water for further molecular analysis.

We treated filter eluant with a guanidine thiocyanate-based lysis buffer (UNEX; Microbiologics, St. Cloud, MN, USA) in a 1:1 volumetric ratio, stored these in SK38 bead tubes (Bertin Corp, MD, USA) and cryovials and transported them to our laboratory in Atlanta. We used 900 μL of sample eluant and UNEX mixture for extraction. After DNA extraction per the bacterial/viral UNEX protocol (Hill et al., 2015), we stored extracted nucleic acids in 50–75 μL of 10 mM Tris-1 mM EDTA (pH 8) in a −80°C freezer until further analysis. We vortexed OWC samples and then followed the same extraction and storage procedures as for eluted air samples.

In total, we collected 27 ACI samples near OWCs (13 wet season, 14 dry season) for E. coli enumeration by culture, 71 high-volume samples for molecular analysis near OWCs (13 wet season, 58 dry season), and 4 grab samples of OWC water. The distance to nearest OWCs was a mean of 93 m (range: 1 – 778 m). We further collected 4 ACI (3 wet season, 1 dry season) and 4 high-volume (2 wet season, 2 dry season) control samples in the unimpacted settings far from human habitation. Sampling locations are shown in relation to OWCs in Figure 1.

ARG detection and quantitative analysis.

We conducted absolute quantification of ARGs via droplet digital PCR (ddPCR™, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). ARG targets spanned three major antibiotic groups commonly used in low-income settings and whose ARGs have been detected previously in environmental samples: tetracyclines (tetA) (Guarddon et al., 2011), fluoroquinolones (qnrB) (Cavé et al., 2016), and β-lactams (blaTEM) (Lachmayr et al., 2009). Resistance to tetracycline in clinical isolates has been reported in multiple studies in Bolivia, including in two urban cities of Bolivia where 93% of E. coli isolates from children’s stool were not susceptible to the antibiotic and another study in La Paz, Bolivia where 28% of ETEC isolates from children’s stool were not susceptible (Bartoloni et al., 2006; Rodas et al., 2011). Furthermore, tetracycline resistant Enterobacteriaceae were detected in ambient air in the same area as ours at 28% prevalence (Salazar et al., 2020) and 50% prevalence (Medina et al., 2020). Fluoroquinolone resistance has been reported in one study in Bolivia where overall, qnr genes were detected in 63% of commensal enterobacteria isolated from healthy children’s stools and specifically, qnrB was detected in 60% of isolates (Pallecchi et al., 2009). Additionally, another study in Bolivia reported fluoroquinolones as a common antibiotic used to treat upper respiratory infections (Cordoba et al., 2017). Class A β-lactamases such as TEM varieties are known to be present in South American countries due to the widespread distribution of β-lactam antibiotics (Villegas et al., 2008). Though the other three assays are specific to the individual gene, the blaTEM assay used in our analysis incorporates 135 variants within the TEM family of β-lactam resistance including resistance to penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems and other antibiotics that have a β-lactic ring in their structure. The TEM β-lactamases can be both ESBL (extended spectrum β-lactamases) and inhibitor resistant and are the most clinically significant. Therefore this assay accounts for a wide range of resistance mechanisms and target drugs that are commonly used in this sampling locations (Lachmayr et al., 2009).

An additional target, integron class 1 (intI1), was included to assess potential genetic mobility and has also been previously detected in environmental media. Through enabling gene cassette movement and their physical association to MGEs, integrons aid in the spread of antibiotic resistance in gram negative bacteria and when present in the environment or in bacteria, they indicate that resistance has either been acquired or may be acquired in the future (Barraud et al., 2010; Gillings et al., 2015; Mazel, 2006). One study by Leverstein-Van Hall et al. found that the detection and presence of integrons in Enterobacteriaceae is strongly associated with resistance to multiple antibiotics and in the case of some antibiotics, predictive of their resistance. (Leverstein-Van Hall et al., 2003).

We experimentally determined LODs for each assay using a probit analysis outlined by Stokdyk et al. (Bivins et al., 2020; Stokdyk et al., 2016). Reaction mixes, conditions, ARG target sequences, and experimentally determined limits of detection (LOD) for each target are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Forward and reverse primers and probes for each assay are listed. Reaction mixes were set to a total volume of 20 μL, containing a primer concentration of 900 nM, probe concentration of 250 nM and 1X Supermix for Bio-Rad’s QX200TM Droplet Digital PCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). We used the ddPCRTM Supermix for Probes for all targets except blaTEM, for which we used ddPCRTM Supermix for Residual DNA Quantification due to the known presence of residual sequence in less purified commercial supermixes (Chiang et al., 2005). On each ddPCR™ plate for all assays, we included 2 positive control wells using a gBlock™ (IDT, Coralville, Iowa, US) containing all of the target ARG sequences in its length, diluted to approximately 103 gc/uL of reaction mixture. For reproducibility, the positive control sequence is also included in a supplementary file. Additionally, we included at least 2 no template controls using molecular water to control for contamination via human or other error and to assess the rate of false positives. For 2 replicates of each sample extract, we quantified gene copies of each target in the ddPCR reaction mixture (2 μL extract, 21 μL of ddPCR reagents) and averaged the results together.

| Gene target | Primers | Probes | Limit of Detection (gc/uL ddPCR reaction mix) | Cycling conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tetA | F: CCGCGCTTTGGGTCATT R: TGGTCGCGTCCCAGTGA |

FAM-TCGGCGAGGATCG-BHQ1 | 0.19 |

95°C for 10 min 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 56°C for 1 min 98°C for 10 min |

| qnrB | F: CAGATTTYCGCGGCGCAAG R: TTCCCACAGCTCRCAYTTTTC |

FAM-CGCACCTGGTTTTGYAG YGCMTATATCAC-BHQ1 |

0.24 | 95°C for 10 min 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 56°C for 1 min 98°C for 10 min |

| bla TEM | F: CACTATTCTCAGAATGACTTGGT R: TGCATAATTCTCTTACTGTCATG |

FAM-CCAGTCACAGAAAAGCATCTTA CGG-BHQ1 |

0.12 | 95°C for 10 min 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 56°C for 1min 98°C for 10 min |

| intI1 | F: GCCTTGATGTTACCCGAGAG R: GATCGGTCGAATGCGTGT |

6HEX-ATTCCTGGCCGTGGTTCTGGG TTTT-BHQ1 |

0.10 | 95°C for 10 min 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 57°C for 1 min 98°C for 10 min |

|

Positive

Control |

ACTTGTCGGACAGGTGCCGGCCGCGCTTTGGGTCATTTTCGGCGAGGATCGCTTTCACTGGGAC GCGACCACGATCGGCATTTCGCTTGCCGAAATCCTTCTTGGGCGCCACCGTTGGCCTTCCTGTAA AGGATCTGGGTCCAGCGAGCCTTGCGGCGGAACTTCACGCGATCGGCAATGGCGCTGACTACGT CCGCATGGGCACCCATCCAACGGTTTTCCCACAGCTCACACTTTTCCAACACGACTTTCGAAAAA TTGGCGTAGCTTAGATTGGTATTCGTGATATATGCGCTACAAAACCAGGTGCGCGTGGTGATCAT ATTCATAAAGCTTGCGCCGCGGAAATCTGCGCCTTGTGCGCGGCAGTGGAGCAACTCGGTCGCC GCATACACTATTCTCAGAATGACTTGGTTGAGTACTCACCAGTCACAGAAAAGCATCTTACGGAT GGCATGACAGTAAGAGAATTATGCAGTGCTGCCATAACCATGAGTGATCGGCGAGTTCTTGGGA TGGCAGGCGATATTCATTACTTTGGCTATACTGGCGATGCTCGCACTCCTAAATGCGGGTTTCAG GTGGCACGAAACCCGCCCTCTGGATCAAGTCAAGACGCGCCGATCTGTCTTGCCGATCTTCGCG AGTCCGGCTTTTTGGGTTTACACTGTCGGCTTTAGCGCCGGTATGGGCACCTTCTTCGTCTTCTTC TCGACGGCTCCCCGTGTGCTCATACGCACGACACCGCTCCGTGGATCGGTCGAATGCGTGTGCTG CGCAAAAACCCAGAACCACGGCCAGGAATGCCCGGCGCGCGGATACTTCCGCTCAAGGGCGTCG GGAAGCGCAACGCCGCTGCGGCCCTCGGCCTGGTCCTTCAGCCACCATGCCCGTGCACGCGACAGC TGCTCGCGCAGGCTGGGTGCCAAGCTCTCGGGTAACATCAAGGCCCGATCCTTGGAGCCCTTGC |

|||

Spatial analysis.

We conducted a spatial analysis to estimate the relationship between lateral distance from OWCs and ARGs in aerosols, using data from the fourth sampling event (2019). First, we calculated the two-dimensional distance from each sampling location to the nearest OWC segment and then, to account for the city’s variable topography and elevation, we adjusted distances by applying the elevations we extracted from the ASTER GDEM (NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Space Systems and Team, 2009) to the horizontal distances of the sampling points in ArcGIS, calculating the adjusted distance through using Pythagorean theorem. We performed a linear regression analysis in RStudio version 1.1.383 to assess the significance of the relationship between lateral distance from OWCs and ARGs density based on 95% confidence (alpha=0.05), subsequently disaggregating the data based on time of sampling (morning or afternoon) and conducting a multiple linear regression analysis to assess the potential diurnal impacts.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

E. coli, ARG and MI detection in aerosol samples.

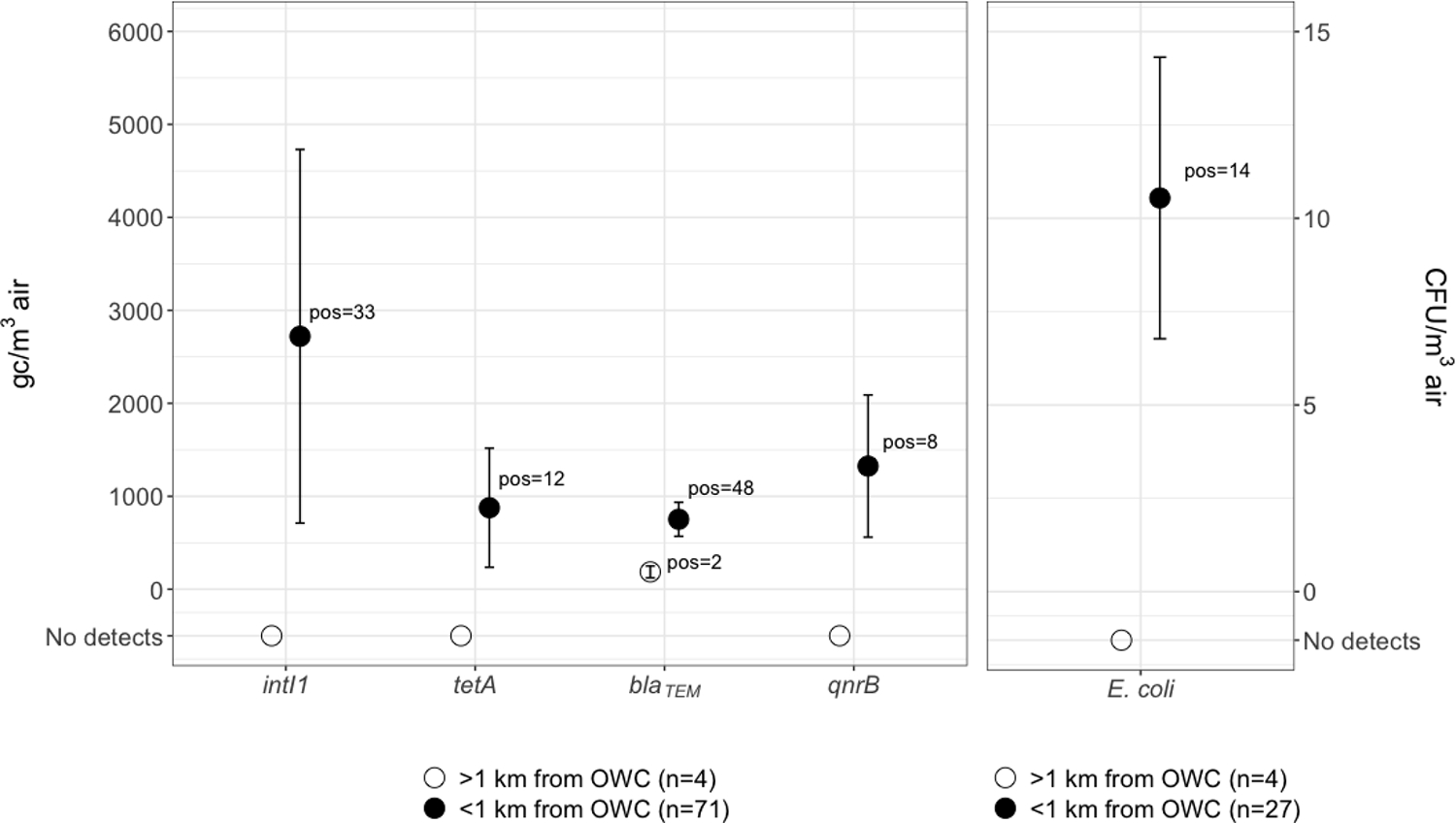

We analyzed high-volume samples for ARG and MI targets (mean volume 48 m3, range 9–216 m3). We set all densities below the experimentally derived LOD to zero. Our LODs can be interpreted as the density at which we are 95% confident that the density detected is accurate. Among samples located <1 km from OWCs (n=71), we detected the MI, intI1, in 47% of samples (n=33) and we detected ARGs qnrB, tetA, and blaTEM in 11%, 17%, and 68% of samples respectively (n=8,12, and 48; Table 3). We then plotted the density distribution and the corresponding standard error for each target (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Summary of positive detections in all air samples after applying the experimentally determined LOD.

| Detections in samples above experimentally determined LOD, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Samples <1 km from OWCs (n=71) | Samples >1 km from OWCs (n=4) | |

| intI1 | 33 (47%) | 0 (0%) |

| qnrB | 8 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| tetA | 12 (17%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaTEM | 48 (68%) | 2 (50%) |

Figure 2.

Left: average ARG and MI densities with mean standard error bars for the distribution in gene copies per cubic meter of air, where targets were detected at levels equal to or above the LOD. Right: mean culturable E. coli per cubic meter of air with mean standard error bars for the distribution in coliforming units per cubic meter of air.

To confirm the presence of aerosolized fecal material, we measured culturable E. coli in aerosol samples (Cronholm, 1980; Dueker, 2012; Farling et al., 2019; Rocha-Melogno et al., 2020; Salazar et al., 2020). We detected E. coli in 52% of samples (n = 14) with an average density of 11 CFU/m3 air across all positive samples (Figure 2). We detected culturable E. coli in aerosols with aerodynamic particle sizes of 0.6–7 μm, in 27 % of culturable E. coli under 2.1 μm, the size cutoff for fine aerosol particles. These data indicate that fecal indicator bacteria may linger in the air on a scale of hours, with a settling velocity in air of 0.5 m/hour for a typical particle with 2 μm diameter (Flagan and Seinfeld, 1988), indicating high transport potential in air near OWCs. While ARGs can be free-floating or contained within viable or non-viable cells, we make no inference about the relationship between E. coli and ARGs in this context, instead using E. coli only as a marker for aerosolized fecal waste that may be attributed to many sources in a contaminated urban setting such as La Paz. We do note that E. coli cultured from aerosols near the Choqueyapu River has indicated the presence of a range of resistant phenotypes in members of the coliform group (Medina et al., 2020; Salazar et al., 2020).

We detected all targets above the LOD among OWC-adjacent sites (Table 3). We detected blaTEM at one control site. Other studies in high-and-middle-income countries have reported comparable ARG absolute densities in contaminated settings where fecal wastes may be enriched, primarily indoors (Gao et al., 2018; Ling et al., 2013). Studies reporting relative abundances of ARGs in outdoor ambient air, such as Li et al. (Li et al., 2018), show that a wide range of ARG and MI subtypes may persist in the environment and shed light on the potential threat of urban aerosol transmission of these contaminants. However, where relative abundance reveals target diversity and presence within the microbial communities of a particular sample, absolute quantification in environmental media allows for characterization in a broader context that can be directly applied to population and environmental exposures through fate and transport modeling and risk assessments. Our results further confirm the range of ARGs present in outdoor ambient air at detectable levels and additionally through absolute quantification allow for public health exposure applications. This suggests widespread distribution of ARGs and associated MIs in ambient air, with uncontained urban wastewater flows now implicated as a potential source in cities with poor sanitation. Once airborne, ARGs and MIs in microorganisms may be transported through the air, inhaled or deposited on surfaces and fomites and subsequently ingested (de Man et al., 2014). Free floating ARGs and MIs may be picked up by other microbes in the environment through horizontal gene transfer. Both mechanisms may contribute to the dissemination of AR in the environment and potentially pose a public health threat to the affected populations.

ARG and MI detection in OWCs.

To confirm the presence of targets in OWCs, we collected samples during the third sampling event (n = 4). We detected intI1 and blaTEM in all OWC samples and at the highest averages (1.4×108 and 6.4×107 gc/100mL respectively). We detected qnrB and tetA in 3/4 OWC samples at averages of 1.7×107 and 1.4×107 gc/100 mL respectively, indicating AR contaminated surface waters that are likely contributing to the dissemination and proliferation of AR in the surrounding environment. Comparably, ESBL-producing bacteria, such as blaTEM, have been detected in the Choqueyapu River previously (Guzman-Otazo et al., 2019; Poma et al., 2016). Although there are limited data on antibiotic usage in Bolivia, previous studies have reported that in some areas in Bolivia and more widely in South America, the most commonly used antibiotics include penicillin, ampicillin, and amoxicillin (Bartoloni et al., 1998; Cordoba et al., 2017), all members of the β-lactam family. High usage of these drugs combined with poor wastewater treatment may lead to the release and spread of resistant organisms. A study in Cochabamba, Bolivia, a city south-east of La Paz, detected the presence of β-lactam resistance encoding ARG variants (also covered by the blaTEM ARG target we used in our study) in rivers that flow throughout the city (Saba Villarroel et al., 2017). Our results support these studies that β-lactam resistance encoding ARGs, in addition to tetracycline and fluoroquinolone resistance encoding ARGs are highly prevalent in these urban settings.

Spatial analysis.

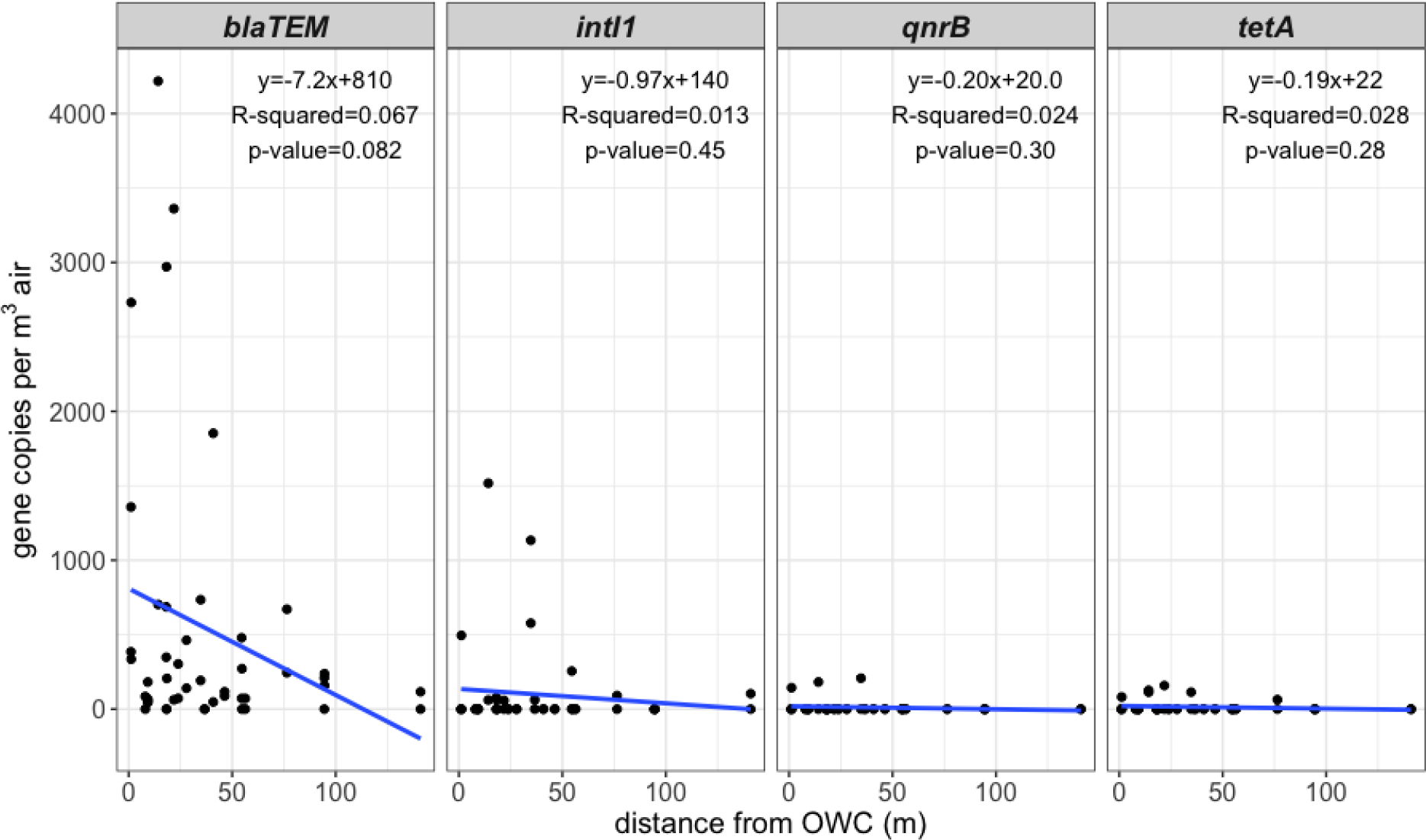

We sought to assess the relationship between ARGs and one MI near OWCs. From the randomly generated points (n=50) for the final sampling event, we only sampled at 25 sites due to time restraints and in some cases, lack of accessibility. One site we sampled at was observed to be much further (~450 m) than within the intended buffer because the actual river location varied from the model near this point. We excluded the 2 samples taken at this site from further analysis and the sample taken at the control site. Hence, we assessed 46 samples from 23 sites in our spatial model, all located within 150 m from OWCs. We performed a linear regression calculation for target densities as distance from OWCs increased and examined the relationship between lateral distance and OWCs for all targets detected (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

ARG density in gene copies per m3 of air in relation to the distance from OWCs. The blue line indicates the linear regression calculation for each data set and the data is not separated by time of day. Each plot includes the corresponding regression line equation, R-squared value, and p-value.

Despite observed mean higher densities of targets at locations close to OWCs, specifically for blaTEM, overall regression results showed no significance between distance from OWCs and ARG density based on 95% confidence both when separated by time of day and when not separated. However, when not separated by time of day we observed a tendency of blaTEM density in aerosols to decrease (p=0.082) as distance from OWCs increases within the 150 m. The apparent decrease may indicate that proximity to OWCs is important when assessing human risk through exposure, though we cannot rule out that this observation is attributable to chance.

Our interpretation of findings is constrained by the study limitations. Our data are observational and limited in time and space, where phenomena such as aerosolization of waste and aerosol transport may be highly variable according to local conditions. We identified a limited number of ARGs to assess a priori, and these may or may not be the most relevant targets for the study area or for exposure relevance more generally. Additionally, we acknowledge that though identification of low gene target densities via ddPCR is improved when compared to qPCR (Cavé et al., 2016), false positives are possible (Cao et al., 2015) even though we have applied conservative estimates of LODs derived experimentally. Though the detection of E. coli in air near OWCs indicates the presence of fecal waste in aerosols, we cannot unambiguously attribute E. coli to these OWCs. Additionally, though ARGs are present in air near OWCs where the same ARGs are also present, we cannot unambiguously identify the OWCs as the source.

CONCLUSION

Bioaerosols near urban wastewater flows may be an important factor in the environmental transmission of AMR in cities with poor sanitation. We found that as distance from fecal waste sources such as OWCs increases, blaTEM density decreases, indicating that proximity to these OWCs is important to consider in the context of dissemination of AR. While the exposure and health risks are unknown, uncontained, concentrated fecal wastes in densely populated cities may present a range of health risks related to exposure to sanitation-related aerosols. Further exploration into the spatial relationship between fecal sources and ARG and MI presence in the environment – including in cities of LMICs – should be pursued, along with quantitative risk models to assess the potential for exposures in this poorly characterized pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number 1653226. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We are thankful for undergraduate and graduate students who helped with sampling and data collection in Bolivia.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AR

antibiotic resistance

- ARG

antibiotic resistance gene; mobile genetic element (MGE)

- MI

mobile integron

- LMICs

low- and middle-income countries

- OWC

open waste cana

- ASTER

Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer

- GDEM

Global Digital Elevation Model

- ACI

Andersen Cascade Impactor

- FIB

fecal indicator bacteria

- CFU

colony-forming unit

- ddPCR

droplet digital PCR

- ESBL

extended spectrum β-lactamases

- LOD

limit of detection

- gc

gene copies

REFERENCES

- Alarcon Calderon VJ, 1996. A Water Quality Model of the Choqueyapu River, La Paz, Bolivia 1–24. 10.16953/deusbed.74839 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen HK, Donato J, Wang HH, Cloud-Hansen KA, Davies J, Handelsman J, 2010. Call of the wild: Antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 251–259. 10.1038/nrmicro2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen AA, 1958. New Sampler for the Collection, Sizing, and Enumeration of Viable Airborne Particles. U. S. Army Chem. Corps Proving Gr. 76, 471–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain RES, Woodall C, Elliott J, Arnold BF, Tung R, Morley R, Du Preez M, Bartram JK, Davis AP, Gundry SW, Pedley S, 2015. Evaluation of an inexpensive growth medium for direct detection of Escherichia coli in temperate and sub-tropical waters. PLoS One 10, 1–13. 10.1371/journal.pone.0140997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraud O, Baclet MC, Denis F, Ploy MC, 2010. Quantitative multiplex real-time PCR for detecting class 1, 2 and 3 integrons. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, 1642–1645. 10.1093/jac/dkq167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoloni A, Cutts F, Leoni S, Austin CC, Mantella A, Guglielmetti P, Roselli M, Salazar E, Paradisi F, 1998. Patterns of antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance among healthy children in Bolivia. Trop Med Int Heal. 3, 116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoloni A, Pallecchi L, Benedetti M, Fernandez C, Vallejos Y, Guzman E, Villagran AL, Mantella A, Lucchetti C, Bartalesi F, Strohmeyer M, Bechini A, Gamboa H, Rodríguez H, Falkenberg T, Kronvall G, Gotuzzo E, Paradisi F, Rossolini GM, 2006. Multidrug-resistant commensal Escherichia coli in children, Peru and Bolivia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 907–913. 10.3201/eid1206.051258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PM, 2008. Plasmid encoded antibiotic resistance: Acquisition and transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153, 347–357. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivins A, Lowry S, Murphy HM, Borchardt M, Coyte R, Labhasetwar P, Brown J, 2020. Waterborne pathogen monitoring in Jaipur, India reveals potential microbial risks of urban groundwater supply. npj Clean Water 3. 10.1038/s41545-020-00081-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Bir A, Bain RES, 2020. Novel methods for global water safety monitoring: comparative analysis of low-cost, field-ready E. coli assays. npj Clean Water 3. 10.1038/s41545-020-0056-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cantón R, 2009. Antibiotic resistance genes from the environment: A perspective through newly identified antibiotic resistance mechanisms in the clinical setting. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02679.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantón R, Coque TM, 2006. The CTX-M β-lactamase pandemic. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantón R, González-Alba JM, Galán JC, 2012. CTX-M enzymes: Origin and diffusion. Front. Microbiol. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Raith MR, Griffith JF, 2015. Droplet digital PCR for simultaneous quantification of general and human-associated fecal indicators for water quality assessment. Water Res. 70, 337–349. 10.1016/j.watres.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavé L, Brothier E, Abrouk D, Bouda PS, Hien E, Nazaret S, 2016. Efficiency and sensitivity of the digital droplet PCR for the quantification of antibiotic resistance genes in soils and organic residues. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 10597–10608. 10.1007/s00253-016-7950-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celenza G, Pellegrini C, Caccamo M, Segatore B, Amicosante G, Perilli M, 2006. Spread of blaCTX-M-type and blaPER-2 β-lactamase genes in clinical isolates from Bolivian hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57, 975–978. 10.1093/jac/dkl055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin A, Rule A, Gibson K, Buckley T, Schwab K, 2005. Airborne multidrug-resistant bacteria isolated from a concentrated swine feeding operation. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 137–142. 10.1289/ehp.7473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Liu C, Weng L, Wang N, Liaw G, 2005. Presence of β -Lactamase Gene TEM-1 DNA Sequence in Commercial Taq DNA Polymerase 43, 530–532. 10.1128/JCM.43.1.530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordoba G, Caballero L, Sandholdt H, Arteaga F, Olinisky M, Ruschel LF, Makela M, Bjerrum L, 2017. Antibiotic prescriptions for suspected respiratory tract infection in primary care in South America. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 305–310. 10.1093/jac/dkw370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronholm LS, 1980. Potential Health Hazards from Microbial Aerosols in Densely Populated Urban Regions 39, 6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Davies D, 2010. Origins and Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 417–433. 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de J, Sosal A., Byarugaba DK., Amabile-Cuevas, CF., Hsueh P-R., Kariuki S., Okeke IN. (Eds.), 2010. Antimicrobial Resistance in Developing Countries, Springer Science and Buisiness Media. 10.1007/s13312-014-0374-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Man H, Heederik DDJ, Leenen EJTM, de Roda Husman AM, Spithoven JJG, van Knapen F, 2014. Human exposure to endotoxins and fecal indicators originating from water features. Water Res. 51, 198–205. 10.1016/j.watres.2013.10.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueker ME, 2012. Connecting Water Quality With Air Quality Through Microbial Aerosols. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria-Palencia CM, Thulsiraj V, Tran N, Ericksen CA, Melendez I, Sanchez MG, Walpert D, Yuan T, Ficara E, Senthilkumar N, Sun F, Li R, Hernandez-Cira M, Gamboa D, Haro H, Paulson SE, Zhu Y, Jay JA, 2017. Disparate Antibiotic Resistance Gene Quantities Revealed across 4 Major Cities in California: A Survey in Drinking Water, Air, and Soil at 24 Public Parks. ACS Omega 2, 2255–2263. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farling S, Rogers T, Knee JS, Tilley EA, Brown J, Deshusses MA, 2019. Bioaerosol emissions associated with pit latrine emptying operations. Sci. Total Environ. 648, 1082–1086. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagan RC, Seinfeld JH, 1988. Fundamentals of air pollution engineering. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Qiu T, Sun Y, Wang X, 2018. The abundance and diversity of antibiotic resistance genes in the atmospheric environment of composting plants. Environ. Int. 116, 229–238. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Shao M, Luo Y, Dong Y, Ouyang F, Dong W, Li J, 2016. Airborne bacterial contaminations in typical Chinese wet market with live poultry trade. Sci. Total Environ. 572, 681–687. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genter F, Marks SJ, Clair-Caliot G, Mugume DS, Johnston RB, Bain RES, Julian TR, 2019. Evaluation of the novel substrate RUG™ for the detection of: Escherichia coli in water from temperate (Zurich, Switzerland) and tropical (Bushenyi, Uganda) field sites. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 5, 1082–1091. 10.1039/c9ew00138g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs SG, Green CF, Tarwater PM, Mota LC, Mena KD, Scarpino PV, 2006. Isolation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from the air plume downwind of a swine confined or concentrated animal feeding operation. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 1032–1037. 10.1289/ehp.8910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillings MR, Gaze WH, Pruden A, Smalla K, Tiedje JM, Zhu YG, 2015. Using the class 1 integron-integrase gene as a proxy for anthropogenic pollution. ISME J. 9, 1269–1279. 10.1038/ismej.2014.226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DW, Giesen MJ, Bunce JT, 2018. Strategic approach for prioritising local and regional sanitation interventions for reducing global antibiotic resistance. Water (Switzerland) 11. 10.3390/w11010027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guarddon M, Miranda JM, Rodríguez JA, Vázquez BI, Cepeda A, Franco CM, 2011. Real-time polymerase chain reaction for the quantitative detection of tetA and tetB bacterial tetracycline resistance genes in food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 146, 284–289. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Otazo J, Gonzales-Siles L, Poma V, Bengtsson-Palme J, Thorell K, Flach C-F, Iñiguez V, Sjöling Å, 2019. Diarrheal bacterial pathogens and multi-resistant enterobacteria in the Choqueyapu River in La Paz, Bolivia. PLoS One 14, e0210735. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill V, Narayanan J, Gallen R, Ferdinand K, Cromeans T, Vinjé J, 2015. Development of a Nucleic Acid Extraction Procedure for Simultaneous Recovery of DNA and RNA from Diverse Microbes in Water. Pathogens 4, 335–354. 10.3390/pathogens4020335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Zhao F, Zhang XX, Li K, Li C, Ye L, Li M, 2018. Metagenomic profiling of ARGs in airborne particulate matters during a severe smog event. Sci. Total Environ. 615, 1332–1340. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INE, 2018. Bolivia cuenta con más de 11 millones de habitantes a 2018 [WWW Document]. URL https://www.ine.gob.bo/index.php/notas-de-prensa-y-monitoreo/item/3170-bolivia-cuenta-con-mas-de-11-millones-de-habitantes-a-2018 (accessed 1.22.20).

- Jacob DJ, 1999. Introduction to Atmospheric Chemistry. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. [Google Scholar]

- Jones AM, Harrison RM, 2004. The effects of meteorological factors on atmospheric bioaerosol concentrations - A review. Sci. Total Environ. 326, 151–180. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2003.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Ram B, Sewwandi H, Sulfikar, Honda., Chaminda T., 2020. Treatment enhances the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes in the wastewater of Sri Lanka, and India. Environ. Res. 183. 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmayr KL, Cavanaugh CM, Kerkhof LJ, DiRienzo AG, Ford TE, 2009. Quantifying nonspecific tem β-lactamase (blatem) genes in a wastewater stream. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 203–211. 10.1128/AEM.01254-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverstein-Van Hall MA, Blok HEM, Donders ART, Paauw A, Fluit AC, Verhoe J, 2003. Multidrug resistance among enterobacteriaceae is strongly associated with the presence of integrons and is independent of species or isolate origin. J. Infect. Dis. 187, 251–259. 10.1086/345880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Cao J, Zhu Y, Chen Q, Shen F, Wu Y, Xu S, Fan H, Da G, Huang R, Wang J, de Jesus AL, Morawska L, Chan CK, Peccia J, Yao M, 2018. Global Survey of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Air. Environ. Sci. Technol. acs.est.8b02204. 10.1021/acs.est.8b02204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhou L, Zhang X, Xu C, Dong L, Yao M, 2016. Bioaerosol emissions and detection of airborne antibiotic resistance genes from a wastewater treatment plant. Atmos. Environ. 124, 404–412. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.06.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ling AL, Pace NR, Hernandez MT, Lapara TM, 2013. Tetracycline Resistance and Class 1 Integron Genes Associated with Indoor and Outdoor Aerosols. 10.1021/es400238g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Chai T, Xia X, Gao Y, Cai Y, Li X, Miao Z, Sun L, Hao H, Roesler U, Wang J, 2012. Formation and transmission of Staphylococcus aureus ( including MRSA ) aerosols carrying antibiotic-resistant genes in a poultry farming environment. Sci. Total Environ. 426, 139–145. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.03.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo A, Coyne S, Berendonk TU, 2012. Origin and evolution of antibiotic resistance: The common mechanisms of emergence and spread in water bodies. Front. Microbiol. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Li AD, Yin X, Le, Zhang T., 2017. The Prevalence of Integrons as the Carrier of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Natural and Man-Made Environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 5721–5728. 10.1021/acs.est.6b05887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magro G, Bain RES, Woodall CA, Matthews RL, Gundry SW, Davis AP, 2014. Synthesis and application of resorufin β- D -glucuronide, a low-cost chromogenic substrate for detecting Escherichia coli in drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 9624–9631. 10.1021/es502319n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazel D, 2006. Integrons: Agents of bacterial evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 608–620. 10.1038/nrmicro1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachran AD, Blackwell BR, Hanson JD, Wooten KJ, Mayer GD, Cox SB, Smith PN, 2015. Antibiotics, bacteria, and antibiotic resistance genes: Aerial transport from cattle feed yards via particulate matter. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 337–343. 10.1289/ehp.1408555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina C, Ginn O, Brown J, Soria F, Garvizu C, Salazar D, Tancara A, Herrera J, 2020. Detection and assessment of the antibiotic resistance of Enterobacteriaceae recovered from bioaerosols in the Choqueyapu River area, La Paz – Bolivia. Sci. Total Environ. 143340. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadimpalli ML, Marks SJ, Montealegre MC, Gilman RH, Pajuelo MJ, Saito M, Tsukayama P, Njenga SM, Kiiru J, Swarthout J, Islam MA, Julian TR, Pickering AJ, 2020. Urban informal settlements as hotspots of antimicrobial resistance and the need to curb environmental transmission. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 787–795. 10.1038/s41564-020-0722-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Space Systems, Team, U.S. /Japa. A.S., 2009. ASTER Global Digital Elevation Model [Data set], NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC [WWW Document]. [Google Scholar]

- Neher TP, Ma L, Moorman TB, Howe A, Soupir ML, 2020. Seasonal variations in export of antibiotic resistance genes and bacteria in runoff from an agricultural watershed in Iowa. Sci. Total Environ. 738, 140224. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno A; Marui A; Castro ES; Reyes AA; Elio-Calvo D; Kasitani H; Ishii Y; Yamaguchi K, 1997. Enteropathogenic Bacteria in the La Paz River of Bolivia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 57, 438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal C, Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ, 2016. The structure and diversity of human, animal and environmental resistomes. Microbiome 4, 54. 10.1186/s40168-016-0199-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallecchi L, Riccobono E, Mantella A, Bartalesi F, Sennati S, Gamboa H, Gotuzzo E, Bartoloni A, Rossolini GM, 2009. High prevalence of qnr genes in commensal enterobacteria from healthy children in Peru and Bolivia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 2632–2635. 10.1128/AAC.01722-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehrsson EC, Tsukayama P, Patel S, Mejía-Bautista M, Sosa-Soto G, Navarrete KM, Calderon M, Cabrera L, Hoyos-Arango W, Bertoli MT, Berg DE, Gilman RH, Dantas G, 2016. Interconnected microbiomes and resistomes in low-income human habitats. Nature 533, 212–216. 10.1038/nature17672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poma V, Mamani N, Iñiguez V, 2016. Impact of urban contamination of the La Paz River basin on thermotolerant coliform density and occurrence of multiple antibiotic resistant enteric pathogens in river water, irrigated soil and fresh vegetables. Springerplus 5. 10.1186/s40064-016-2132-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruden A, Pei R, Storteboom H, Carlson KH, 2006. Antibiotic resistance genes as emerging contaminants: Studies in northern Colorado. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 7445–7450. 10.1021/es060413l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S.ur, Ali T., Ali I., Khan NA., Han B., Gao J., 2018. The Growing Genetic and Functional Diversity of Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamases. Biomed Res. Int. 2018. 10.1155/2018/9519718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo L, Manaia C, Merlin C, Schwartz T, Dagot C, Ploy MC, Michael I, Fatta-Kassinos D, 2013. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 447, 345–360. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Melogno L, Ginn O, Bailey ES, Soria F, Andrade M, Bergin MH, Brown J, Gray GC, Deshusses MA, 2020. Bioaerosol sampling optimization for community exposure assessment in cities with poor sanitation: A one health cross-sectional study. Sci. Total Environ. 738. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodas C, Mamani R, Blanco J, Blanco JE, Wiklund G, Svennerholm AM, Sjöling Å, Iniguez V, 2011. Enterotoxins, colonization factors, serotypes and antimicrobial resistance of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains isolated from hospitalized children with diarrhea in Bolivia. Brazilian J. Infect. Dis. 15, 132–137. 10.1016/S1413-8670(11)70158-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba Villarroel PM, Gutkind GO, Di Conza JA, Radice MA, 2017. First survey on antibiotic resistance markers in Enterobacteriaceae in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 49, 50–54. 10.1016/j.ram.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino R, Di Cesare A, Dzhembekova N, Fontaneto D, Eckert EM, Corno G, Moncheva S, Bertoni R, Callieri C, 2020. Spatial distribution of antibiotic and heavy metal resistance genes in the Black Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 160, 111635. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar D, Ginn O, Brown J, Soria F, Garvizu C, 2020. Assessment of antibiotic resistant coliforms from bioaerosol samples collected above a sewage-polluted river in La Paz, Bolivia. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 228, 113494. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancheza HM, Echeverria C, Thulsiraj V, Zimmer-Faust A, Flores A, Laitz M, Healy G, Mahendra S, Paulson SE, Zhu Y, Jay JA, 2016. Antibiotic Resistance in Airborne Bacteria Near Conventional and Organic Beef Cattle Farms in California, USA. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 227. 10.1007/s11270-016-2979-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schrag SJ, McGee L, Whitney CG, Beall B, Craig AS, Choate ME, Jorgensen JH, Facklam RR, Klugman KP, 2004. Emergence of Streptococcus pneumoniae with very-high-level resistance to penicillin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 3016–3023. 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3016-3023.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid M, Singh A, Sobia F, Rashid M, Malik A, Shukla I, Khan HM, 2011. Bla CTX-M, bla TEM, and bla SHV in Enterobacteriaceae from North-Indian tertiary hospital: High occurrence of combination genes. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 4, 101–105. 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60046-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange C, Tiehm A, 2020. Occurrence of antibiotic resistance genes and microbial source tracking markers in the water of a karst spring in Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 742, 140529. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward CD, Wallace D, Hubert SK, Lawton R, Fridkin SK, Gaynes RP, McGowan JE, Tenover FC, 2000. Ability of laboratories to detect emerging antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: A survey of Project ICARE laboratories. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 38, 59–67. 10.1016/S0732-8893(00)00161-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokdyk JP, Firnstahl AD, Spencer SK, Burch TR, Borchardt MA, 2016. Determining the 95% limit of detection for waterborne pathogen analyses from primary concentration to qPCR. Water Res. 96, 105–113. 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikesland PJ, Pruden A, Alvarez PJJ, Aga D, Bürgmann H, Li XD, Manaia CM, Nambi I, Wigginton K, Zhang T, Zhu YG, 2017. Toward a Comprehensive Strategy to Mitigate Dissemination of Environmental Sources of Antibiotic Resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 13061–13069. 10.1021/acs.est.7b03623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas MV, Kattan JN, Quinteros MG, Casellas JM, 2008. Prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in South America. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14, 154–158. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01869.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang C, Song L, 2019. Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes and bacteria from sixatmospheric environments: Exposure risk to human. Sci. Total Environ. 694. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington EMH, Boxall ABA, Cross P, Feil EJ, Gaze WH, Hawkey PM, Johnson-Rollings AS, Jones DL, Lee NM, Otten W, Thomas CM, Williams AP, 2013. The role of the natural environment in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 155–165. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70317-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte W, 2000. Selective pressure by antibiotic use in livestock. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 16, 19–24. 10.1016/S0924-8579(00)00301-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2019. Ten threats to global health in 2019 [WWW Document]. WHO Bull. https//www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Jin L, He T, Chen B, Luo X, Feng B, Huang W, Li J, Fu P, Li X, 2019. Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) in PM2.5 from China: Implications for Human Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 963–972. 10.1021/acs.est.8b04630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Zuo J, Yu X, Shi X, Chen L, Li Z, 2017. Quantification of multi-antibiotic resistant opportunistic pathogenic bacteria in bioaerosols in and around a pharmaceutical wastewater treatment plant. J. Environ. Sci. 1–11. 10.1016/j.jes.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y-G, Johnson TA, Su J-Q, Qiao M, Guo G-X, Stedtfeld RD, Hashsham SA, Tiedje JM, 2013. Diverse and abundant antibiotic resistance genes in Chinese swine farms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 3435–3440. 10.1073/pnas.1222743110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]