Abstract

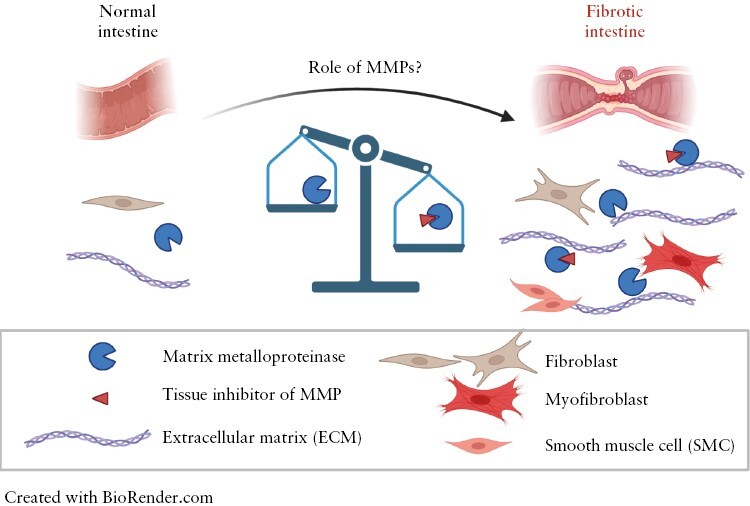

Intestinal fibrosis is a common complication in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [IBD], in particular Crohn’s disease [CD]. Unfortunately, at present intestinal fibrosis is not yet preventable, and cannot be treated by interventions other than surgical removal. Intestinal fibrosis is characterized by excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix [ECM], which is caused by activated fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. Accumulation of ECM results from an imbalanced production and degradation of ECM. ECM degradation is mainly performed by matrix metalloproteinases [MMPs], enzymes that are counteracted by tissue inhibitors of MMPs [TIMPs]. In IBD patients, MMP activity [together with other protease activities] is increased. At the same time, CD patients have a generally lower MMP activity compared to ulcerative colitis patients, who usually do not develop intestinal strictures or fibrosis. The exact regulation and role[s] of these MMPs in fibrosis are far from understood. Here, we review the current literature about ECM remodelling by MMPs in intestinal fibrosis and their potential role as biomarkers for disease progression or druggable targets.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

1. Introduction

Crohn’s disease [CD] and ulcerative colitis [UC] are inflammatory bowel diseases [IBD] characterized by relapsing and remitting inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. The prevalence of IBD is around 0.5% in the Western world, but is increasing worldwide.1,2 Intestinal fibrosis/stenosis is a common complication of CD, much more than in UC.3 Around 30–50% of CD patients develop a stricturing disease, often around the terminal ileum in the ileocecal region, as a result of tissue fibrosis.4–6 To classify the patient's characteristics, the Montreal classification system has been developed. Using this system, age of onset, disease location [using L1 for terminal ileum, L2 for colon, and L3 for ileocolon] and behaviour can be classified [using B1 for nonstricturing, nonpenetrating, B2 for structuring, and B3 for penetrating disease].7 Current therapies target the inflammatory component of the disease by using anti-inflammatory therapy such as tumour necrosis factor [TNF]α-antagonists and corticosteroids, but these do not prevent or regress intestinal fibrosis.8 So far, surgery with/without stricturoplasty or endoscopic balloon dilatation are the only treatments available for intestinal fibrosis. However, these interventions cause a high patient burden and do not prevent recurrent fibrosis.5

The general description of tissue fibrosis, including intestinal fibrosis, is that fibrosis results from the excessive production of extracellular cellular matrix [ECM] components, produced by activated fibroblasts and other ECM-producing cell types. Besides excessive ECM production, the ECM composition and ECM remodelling are altered during fibrogenesis and fibrosis.9,10 ECM is the scaffolding network for cells and a substantial component of tissues. In addition to giving the tissue support, it is becoming increasingly clear that ECM also has a role in cell signalling via mechanosignalling and serves as a buffer for a plethora of signalling molecules (such as transforming growth factor [TGF]-β) and matrix metalloproteinases [MMPs].11,12 The ECM has a critical impact on the immune system and vice versa. For example, due to altered ECM composition during inflammation, the binding affinity of leukocytes to the ECM is increased, leading to increased retention of immune cells during inflammation.13 On the other hand, immune cells can produce MMPs and other ECM-degrading enzymes, especially during inflammation, which will be discussed further in this review.

Fibrosis is a universal response in different chronically diseased tissues and organs, a response aimed at tissue healing. Although the outcome, e.g. changes in ECM composition, tissue stiffening, and loss of functionality, are similar in the different organs, there are distinct mechanisms that lead to the progression of fibrosis. Furthermore, the ECM composition and remodelling are also different in different organs. While the diverse role of ECM remodelling proteins, such as MMPs and their inhibitors [tissue inhibitors of MMPs, TIMPs], was discussed previously for several organs,14 a dedicated review on the function of these proteins in intestinal fibrosis is still lacking. The role of ECM, MMPs, and TIMPs in intestinal inflammation in IBD has been reviewed previously11,15,16 but did not specifically focus on the role of the ECM remodelling proteins in the context of intestinal fibrosis. Hence, this review discusses the importance of the ECM and its remodelling proteins during intestinal fibrosis in CD, mainly focusing on the role of MMPs and TIMPs.

2. ECM remodelling by MMPs

MMPs play an important role in ECM remodelling during tissue homeostasis and disease.17 MMPs are endopeptidases that can degrade ECM components and are therefore important for ECM remodelling homeostasis.17 MMPs contribute to processes such as angiogenesis, cell migration, tissue repair, and inflammation. In healthy tissue, MMPs are important for normal ECM turnover, and MMP activity is very low.15,18,19 In IBD, MMP expression, activity, and inhibition by their inhibitors [TIMPs] are dysregulated, which is assumed to lead to serious complications such as fistula and fibrosis.11,20

MMPs are zinc-dependent endopeptidases that can cleave ECM constituents and other non-matrix proteins, such as cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, growth factors, and their receptors. The MMP protein family shares common structural and functional elements.17 MMPs have a substrate specificity and are subdivided into different classes, namely collagenases [MMP-1, -8, and -13], gelatinases [MMP-2 and -9], stromelysins [MMP-3, -10, -11, and -19], matrilysins [MMP-7 and -26], membrane-type MMPs [MT-MMPs], macrophage elastase [MMP-12], and others [Table 1]. Within these classes, MMPs have their own substrate specificity and affinity. For example, MMP-1 [collagenase-1] preferentially cleaves type III collagen, MMP-8 [collagenase-2] prefers type I collagen, and MMP-13 [collagenase-3] cleaves type II collagen more efficiently.21 In healthy tissue, the expression of collagenases is very low, but these collagenases are upregulated during inflammation and have been linked to tissue destruction.21 Because MMPs are potentially hazardous for tissues, their expression, activity, and inhibition by [among others] TIMPs are tightly regulated. In most cells, MMPs are synthesized and secreted immediately. However, MMPs can be stored in granules in inflammatory cells and released upon stimulation.15 Every MMP, even those with similar substrate specificity, has its own expression pattern, dependent on cell type, tissue and disease context. Transcription is regulated by growth factors and cytokines and can cause 20- to 50-fold changes in MMP mRNA and protein expression upon stimulation.22 MMPs are synthesized as pro-peptides and need to be activated. Cleavage of the pro-peptide can be induced chemically [i.e. hypoxia or via NO], following autolytic cleavage, or via other proteases [e.g. MMPs]. Once activated by pro-peptide cleavage, MMP activity is dependent on the presence of [one of] its inhibitors [TIMPs]. In turn, TIMPs [1–4] also have their substrate specificity, but this still needs to be further elucidated.17,19 Finally, ECM and especially ECM-breakdown products [neo-epitopes] can also regulate MMP activity.12 For example, elastin peptide κ-elastin increased MMP-1 expression in human skin fibroblasts.25 A more detailed description of MMP regulation and substrate specificity has been described previously.18,22

Table 1.

| Class name | MMPs | ECM substrates | Non-ECM substrates [among others] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Result | |||

| Collagenases | MMP-1, -8, and -13 | Collagen types I, II, III, and V triple-helices | α1-antitrypsin Plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 α2-antiplasmin Latent TGF-β1 |

Inactive SERPINA1 Inactive PAI2 [SERPINB2] Inactive SERPINF2 Activated TGF-β1 |

| Gelatinases | MMP-2 and -9 | Gelatin, denatured collagens, collagen type IV | Latent TGF-β1 α1-antitrypsin Plasminogen |

Activated TGF-β1 Inactive SERPINA1 |

| Stromelysins | MMP-3, -10, and -11 | ECM substrates [except triple-helical collagens] | α1-antitrypsin Plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 Endostatin Latent TGF-β1 Collagenases |

Inactive SERPINA1 Inactive PAI2 Activation Activated TGF-β1 Activation |

| Matrilysins | MMP-7 and -26 | ECM substrates [except triple-helical collagens] | α1-antitrypsin | Inactive SERPINA1 |

| Macrophage elastase | MMP-12 | Elastin | α1-antitrypsin | |

| Others | MMP-19, -20 -21, -23A/B, -27, and -28 | |||

| Membrane-type MMPs | MMP-14, -15, -16, -17, -24, and -25 | |||

Besides regulation of MMP activity via transcription, translation, and proteolytic activation, MMP and TIMP expression and activity can also depend on specific DNA variants in the gene or promotor region. For example, the TIMP-1 genotype TIMP-1 + 372 T is significantly more abundant in CD patients compared to healthy controls. TIMP-1 protein expression in TIMP-1 + 372 T patients is lower compared to TIMP-1 + 372 C patients.26 Therefore, this TIMP-1 + 372 T genotype might be a risk factor for CD and associated with higher MMP activity. No differences in MMP-1, -2, -3, -9 and TIMP-2 genotype distribution in IBD patients and controls were found.26 Although there is no significant difference between MMP-3 genotype distribution between IBD patients and controls, distinct genotype distributions within IBD patients with different disease behaviour [e.g. stricturing or penetrating] do exist. The MMP-3 -1613 5T5T genotype was significantly more frequent in CD patients who developed strictures, compared to the other MMP-3 -1613 5T6T/6T6T genotypes.26 The MMP-3 protein also seems to be more highly expressed in IBD tissue carrying the 5T5T variant of the MMP3 gene compared to 5T6T/6T6T genotypes, but this was not significant.26,27

3. Normal intestinal MMP expression

In the intestine, MMPs and TIMPs are expressed by different cell types in all layers of the intestinal wall [Table 2]. In normal tissue, MMPs are mostly secreted in their latent [inactive] form.28,29 In the lamina propria, just below the epithelial layer, expression of MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 has been shown, as well as the expression of TIMP-1.28,30,31 MMP-2 expression was also detected in the muscularis mucosa,28 although another study did not observe MMP-2 [gelatinase A] expression in histologically normal sections.31 MMP-1 and -9 are shown to be expressed in the submucosa as well as in the muscularis externa.30,31

Table 2.

MMP and TIMP expression in normal human intestine

| Intestinal layer | Cell types | Protein |

|---|---|---|

| Mucosa | Epithelium | MMP-1, -2, -3, -7, -8, -9, -10, 12, -19, and -28, TIMP-2 and -3 |

| Villus-associated fibroblasts | MMP-11 | |

| Lamina propria | MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 and TIMP-1 | |

| Myeloid cells | MMP-12 | |

| Muscularis mucosae | MMP-2 | |

| Submucosa | Not determined | MMP-1 and -9 |

| Monocytes | MMP-2, -3, -9, -10, and -19 and TIMP-1 | |

| Polymorphonuclear cells | MMP-9 | |

| Fibroblasts | MMP-2 | |

| Muscularis externa | MMP-1 and -9 | |

| Not detected | MMP-1, -10, and -13 | |

| Not studied | MMP-14, -15 -16, -17, -23A/B, -24, -25, -26, and -27 and TIMP-3 and -4 | |

In the intestine, epithelial and mononuclear cells [including macrophages and lymphocytes] show a more pronounced expression of MMPs and TIMPs compared to polymorphonuclear cells [including basophils, eosinophils, and neutrophils] and fibroblasts. In primary human colonic epithelial cells, high mRNA expression of MMP-1, -3, -7, -10 and -12, and low and inconsistent expression of MMP-2, -8, -9 were detected. MMP-11, -13 and -14 mRNA was not detected in vitro.32 Immunohistochemical staining of the normal human colon indicates that MMP-10 and -19, TIMP-2 and -3 are expressed in the epithelium.28,33 Immunohistochemistry revealed low levels of MMP-2 in the colonic epithelium, whereas MMP-1, -3, -7, -9, and TIMP-1 were not detected.28,34 Monocytes express MMP-2, while a low number of monocytes also express stromelysins [MMP-3 and -10], MMP-9, and TIMP-1. Collagenase [MMP-1, -8, and -13] expression is hardly detected in monocytes.28,31 In intestinal polymorphonuclear cells, only MMP-9 expression is detected.31 In intestinal fibroblasts, only MMP-2 expression was detected.28

Kirkegaard et al. did not observe any expression of MMP-1 and MMP-7 in control colon biopsies using immunohistochemistry [IHC].28 Using in situ hybridization, MMP-10 [stromelysin-2], MMP-12 [macrophage elastase], and MMP-13 [collagenase-3] were also not detected.35 To the best of our knowledge, expression of other MMPs and TIMPs have not been studied in the intestine.33 Of note, [secreted] MMPs may be hard to detect using IHC when they are not actively produced at the time of tissue fixation. Thus, in normal tissue, MMP detection using IHC might not be the most suitable detection method because MMP expression is generally very low. In this case, Western blot analysis, immunoprecipitation of tissue lysates, or mRNA analysis might be more trustworthy.36 RNA sequencing [RNA-seq] makes it possible to study the complete transcriptome of certain tissues in homeostasis and disease. More recently, single-cell RNA-sequencing [scRNA-seq] has been an upcoming technique that makes it possible to study cellular diversity and gene expression in a single cell type.37,38 scRNA-seq of normal human duodenum revealed that mature enterocytes show enriched expression of TIMP2, while enterochromaffin cells [an enteroendocrine cell subtype] show enriched expression of TIMP1.39 MMP transcripts are found in multiple cell types,39, but the number of transcripts per cell is rather low [no significant enrichment in any cell type], which is expected in a healthy gut.40 Smillie et al. performed scRNA-seq on colon biopsies from UC patients and healthy controls. These authors showed that MMPs and TIMPs in combination with other markers can be used as a marker for several stromal and immune cell subtypes [e.g. inflammatory fibroblasts and inflammatory monocytes]. For example, MMP-2 appears to be a specific marker for stromal cells, and more specifically for fibroblasts. MMP-11 was found to be a specific marker for villus-located fibroblasts [WNT5B + 1, WNT5B + 2], and MMP-12 was found to be specific for myeloid cells [including macrophages].41

4. ECM composition

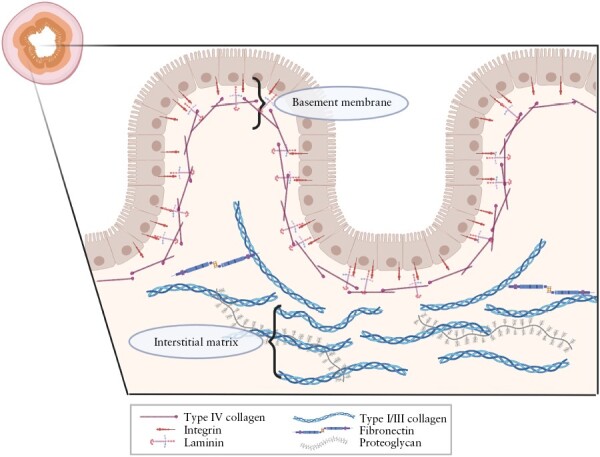

The ECM is a substantial component of tissues and is essential for tissue function, architecture, and homeostasis. In the normal intestine, the ECM can be divided into two compartments, the basement membrane and the interstitial ECM [Figure 1]. The basement membrane in the intestine supports the epithelial cells and consists mainly of laminins and type IV collagen. The interstitial matrix provides tissue strength and elasticity and consists mainly of type I, III, and V collagens and elastin.42 ECM, besides giving mechanical support to the tissue, also regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration, and has a function in cell–cell communication via integrin signalling.43 Moreover, the ECM also stores and releases various molecules [e.g. TGF-β] and ECM-turnover products [neo-epitopes] and thereby has a signalling function as well.12

Figure 1:

Extracellular matrix compartments of the intestine. Schematic representation of the basement membrane and the interstitial matrix. Created with BioRender.com.

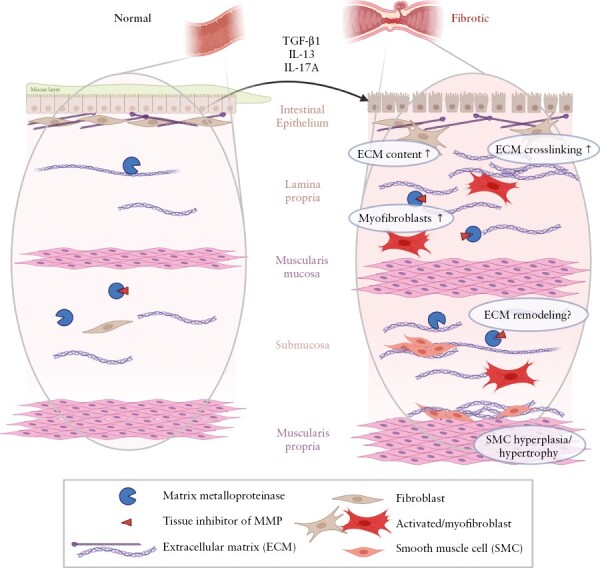

Fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells [SMCs] are the main cell types responsible for ECM production and remodelling, especially during wound healing and fibrosis [Figure 2]. Fibroblasts (vimentin [VIM]+, α-smooth muscle actin [SMA]−−) are responsible for maintaining the ECM by secreting ECM components. Recent scRNA-seq studies have revealed that there are multiple fibroblast subsets and that they differ in healthy and inflamed human gut.37,41 For example, the inflammation-associated fibroblast subset is abundant in UC patients and can be expanded more than 100-fold compared to in healthy individuals.41 As a result of pro-fibrotic signalling, fibroblasts can differentiate into myofibroblasts [VIM+, SMA+]. Due to the presence of the actin cytoskeleton in myofibroblasts, these cells can contract and exert tension on the ECM. Recently, it has been shown that not only fibroblasts proliferate and migrate to the fibrotic tissue, but also SMCs [SMA+, DES+] from the muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria can produce ECM and are present in the fibrotic submucosa, while they are not present in the healthy submucosa. SMC hyperplasia and hypertrophy in the muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria [interna] in intestinal strictures seem to be the main factor contributing to the increased wall thickness.44,45 During wound healing, fibroblasts are attracted to the damaged tissue, start producing ECM, and use their contractile ability to initiate wound closure. During normal wound healing, ECM production and contraction will be terminated by inducing fibroblast and myofibroblast apoptosis. However, during chronic inflammation, apoptosis is inhibited/prevented and ECM production and contractility are further increased.46,47

Figure 2:

Changes in fibrotic intestine. Schematic representation of normal and fibrotic intestine. Pro-fibrotic stimuli, e.g. transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), Interleukin-13 and 17A (IL-13/IL-17A) contribute to the progression of fibrosis. Fibrosis in the intestine is characterized by increased extracellular matrix (ECM), changed ECM composition, myofibroblast differentiation, and smooth muscle cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy in the muscularis mucosae as well as in the muscularis propria. How changed in ECM remodeling contribute to intestinal fibrosis is currently unknown. Created with BioRender.com.

In the healthy intestine, the mucosa [including the epithelium], submucosa, and muscularis propria are clearly distinguishable. In the mucosa and submucosa, collagens of the interstitial matrix [type I and III collagens] are loosely arranged and mostly present near the muscularis propria48,49 [Figure 1]. During chronic inflammation in IBD, the intestinal wall is damaged and requires repair and ECM reconstruction. The inflamed intestine of CD patients shows an increased type III/I collagen ratio [inflamed 0.61 vs normal 0.24 in the lamina propria] in all intestinal layers.50 In the inflamed fibrotic intestine, the type III/I collagen ratio increases even further [1.11 in the lamina propria].50 It has been shown in human tissue samples and in vitro in fibroblast cultures that the majority of the ECM proteins are upregulated in the fibrotic intestine resulting in an altered composition and function of the fibrotic ECM.48–53 ECM composition and architecture are highly influenced by post-translational modifications, which have also been shown to be affected by intestinal fibrosis51,53 [Figure 2]. We refer to recent reviews42,43,54 for more detailed overviews of the function of different collagens and ECM proteins in the intestine.

As a result of increased collagen deposition and muscle hyperplasia, the submucosa, muscularis mucosae and serosa are often expanded in fibrotic areas [Figure 2].48,55 In the submucosa, clusters of SMCs with associated collagen appear. Also, the luminal side of the muscularis propria contains collagenous material.48 Fibrosis and SMC hyperplasia/hypertrophy are different in ileal vs colonic strictures. In the ileum, muscular hyperplasia and hypertrophy are more abundant compared to the colon, while fibrosis of the submucosa and muscularis propria is more apparent in the colon.45,47,48 Following the increase in collagen content in the fibrotic intestine, the stiffness of the intestine is also increased [Young’s modulus of 16.7 kPa vs 2.9 kPa for healthy bowel].56 Tissue stiffness has a strong influence on [myo-]fibroblast behaviour. For example, intestinal [myo-]fibroblasts cultured on stiff collagen gels produce more collagen and fewer ECM-degrading enzymes,53,56 which further stimulates fibrogenesis.

As described above, intestinal fibrosis is characterized by thickening of all intestinal layers and increased collagen deposition. This is probably initiated by inflammation and insufficient wound healing by fibroblasts.44 Furthermore, ECM composition and architecture are altered as a result of dysregulated expression of collagen and collagen-crosslinking enzymes. To counteract ECM production and cross-linking, ECM degradation is mediated by proteases such as MMPs. The ECM turnover by MMPs is disturbed during fibrotic disease, thereby further promoting fibrosis.8,56

5. Increased expression of MMPs in IBD

During a clinical relapse in IBD, the mucosal architecture, including the ECM, is disrupted as a consequence of infiltrating immune cells and chronic inflammation. MMP expression and activity are generally increased in the inflamed mucosa of IBD patients [Table 3].16,20 We will briefly describe the role of MMPs in [intestinal] inflammation since this topic has been extensively reviewed already.15,16,21,23,65

Table 3.

MMP expression in the inflamed human intestine [compared to control]

| Gene | Protein | Activity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagenases | |||

| MMP-1 | ↑ mucosa57, epithelial cells32, fibroblasts41 | ↑ mucosa57, ↔31 | ↑58 |

| MMP-8 | ↔ epithelial cells32 | ↔31, ↑59 | |

| MMP-13 | ↑60 | ||

| Gelatinases | |||

| MMP-2 | ↑ mucosa34,57,61,62, ↔ epithelial cells32 |

↑ mucosa58,34,57 | ↑ mucosa28,58,29,34 |

| MMP-9 | ↑ mucosa34,61,62, ↑ epithelial cells32 | ↑ mostly mucosa and submucosa28,58,31, mucosa29,34 | ↑ mucosa58,29 |

| Stromelysins | |||

| MMP-3 | ↑ mucosa38,57,61,62, epithelial cells32, fibroblasts41 | ↑ mucosa63,64,28,57 | ↑58 |

| MMP-10 | ↑ mucosa61,62, ↑ epithelial cells32 |

||

| Matrilysins | |||

| MMP-7 | ↑ mucosa61,62, ↑ epithelial cells32,41 |

||

| Macrophage elastase | |||

| MMP-12 | ↔ epithelial cells32, ↑ mucosa35,38,62 |

↑ mucosa64 | |

| Membrane-bound MMPs | |||

| MMP-14 | ↑ mucosa57 | ||

| Others | |||

| MMP-19 | ↔ whole intersection33, ↑ mucosa61,62 |

↔, ↓, ↑ epithelial cells [all MMP-19 forms, pro-MMP-19 peptide, hinge-region MMP-19 respectively]33 | |

| MMP-28 | ↓ mucosa62 | ||

| TIMPs | |||

| TIMP-1 | ↑ mucosa57,62, ↑ absorptive and secretory epithelial cells41 |

↔ mucosa28,64, ↑ mucosa58,63 |

|

| TIMP-2 | ↔ mucosa57, ↑ immature enterocytes and mast cells41, ↑ mucosa62 |

↔58 | |

| TIMP-3 | ↑35 | ||

↑ = increased expression or activity in tissue from IBD patients compared to controls.

↓ = decreased expression or activity in tissue from IBD patients compared to controls.

↔ = similar expression or activity in tissue from IBD patients compared to controls.

This might be caused by changes in cellular composition [e.g. >100-fold increase in inflammation-associated fibroblasts] of the affected intestine, as well as changes in gene expression in particular cell types.41 Gene expression of MMP-1, -2, -3, -14, and TIMP-1 is increased in inflamed IBD mucosa, while MMP-9 and TIMP-2 expression levels are not affected.26,34,57In vitro cultured colonic epithelial cells isolated from IBD patients show increased gene expression of MMP-1, -3, -7, -9, and -10 compared to control epithelial cells.32 Protein expression of MMP-1, -2, -3, -9, -12, and TIMP-1, but not TIMP-2, is increased in inflamed mucosa from IBD patients compared to controls.34,57,58,63,66 In inflamed tissue, the presence of the latent form of MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 is increased compared to controls.29,58 MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 activity is higher in IBD mucosa compared to controls.58 The gene expression of MMP-1, -2, -3, -14, and TIMP-1 is positively correlated with the histological degree of inflammation.57 Interestingly, only detailed characterization of the expression patterns of the different MMP-19 forms, e.g. pro-peptide and processed/activated forms, has been studied in IBD patients.33 Here, an antibody against the MMP-19 pro-peptide [likely to interact with inactive non-processed MMP-19] and an antibody against the MMP-19 hinge-region [detects processed and probably active MMP-19] were used. This study showed that MMP-19 pro-peptide was present in the epithelium of healthy intestinal tissue, but was not detected in IBD epithelium. On the other hand, the MMP-19 hinge-region was detected in both healthy as well as IBD epithelium. These authors concluded that MMP-19 expression is not down- or up-regulated in IBD epithelium compared to controls, but MMP-19 activation by cleavage of the pro-peptide is increased.33

To obtain a broader overview of changed MMP and TIMP expression, we reviewed several [sc-]RNA-seq studies that compared the transcriptome of normal and inflamed mucosa from IBD patients. Using bulk RNA-seq on inflamed and non-inflamed mucosal biopsies of UC and CD patients, Hu et al. found increased expression of MMP-1, -2, -3, -7, -9, -10, and -19 and increased expression of TIMP-1, -2, and -3 in inflamed vs non-inflamed mucosa.61 Furthermore, these authors showed pathway enrichment of ‘activation of matrix metalloproteinases’, ‘degradation of the extracellular matrix’, and ‘extracellular matrix organization’ in inflamed mucosal biopsies.61 Analysis of differentially expressed genes [DEGs] showed that MMP-3 is in the ‘top 10 upregulated genes’ in inflamed CD mucosa compared to healthy control mucosa [ileum and colon samples combined]. Moreover, Hong et al. showed that SERPINE1 and MMP-12 are significantly increased in inflamed CD mucosa compared to non-inflamed CD and healthy control mucosa,38 also indicating the important role of MMPs in intestinal inflammation. When DEG analysis was performed on colonic samples only, MMPs did not show up as DEGs in inflamed colonic CD mucosa compared to non-inflamed colonic CD mucosa and healthy control mucosa.38 This might indicate that the role of MMPs in CD inflammation is different in the ileum and colon. scRNA-seq of inflamed and non-inflamed CD mucosa revealed that MMP-2 and CTSK are expressed in stromal cells, especially in activated fibroblasts.40 Smillie et al. showed significantly increased expression of MMP-7 in epithelial cells of inflamed UC mucosa compared to healthy control mucosa. Moreover, these authors showed increased expression of TIMP-1 by absorptive epithelial cells and secretory epithelial cells and increased expression of TIMP-2 by immature enterocytes in inflamed UC mucosa compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, fibroblasts had higher expression of MMP-1 and -3 and mast cells had higher expression of TIMP-1 in UC mucosa compared to healthy controls.41 Interestingly, Smillie et al. found that the inflamed and uninflamed UC mucosa DEG signature was very similar, indicating that uninflamed UC mucosa is still affected by UC inflammation.

Increased activity of MMPs is also reflected by MMP-degradation products in the serum of IBD patients. C1M [type I collagen degradation product of MMP-2, -9, and-13], C3M [type III collagen degradation product of MMP-9], C4M [type IV collagen degradation product of MMP-2, -9, and -12], and C6Ma3 [type VI collagen alpha chain degradation product of MMP-2 and -9] are significantly elevated in the serum of Montreal B1 [non-stricturing, non-penetrating] CD patients compared to healthy controls.67,68 In contrast, C5M [type V collagen degradation product of MMP-2 and -9] and C6M [type VI collagen degradation product of MMP-2 and -9] levels are similar between Montreal B1 CD patients and healthy controls.68

Interestingly, when comparing MMP expression in different locations in the intestine, it seems that MMP expression and activity are lower in CD patients with ileum involvement compared to CD patients with colonic inflammation. De Bruyn et al. showed that MMP-12 expression is lower in mucosa from inflamed CD ileum compared to the colon, whereas other MMPs and TIMPs were not differently expressed.62 Mortensen et al. showed that BGM [MMP-3 and -9 degradation product] was lower in the serum of CD patients with ileum [Montreal L1] vs colonic [Montreal L2/3] involvement.69 It might be possible that fibrostenotic complications develop more often in the ileocecal region because there is a lower ECM-degrading capacity at that location, but this should be further investigated.

Increased expression of MMPs during inflammation has several consequences. MMPs might increase cellular migration by loosening the cells from each other and/or the surrounding ECM, thereby promoting the infiltration of immune cells and fibroblasts. Furthermore, MMPs can activate cytokines and chemokines, thereby promoting chemotaxis and/or activation of inflammatory cells. Migration of inflammatory cells and fibroblasts, on the one hand, might promote wound healing as these cells are needed for a proper wound healing response. However, when dysregulated MMP activation also causes defects in the epithelial barrier and inflicts too much tissue damage, there might be a vicious circle of MMP activation and inflammation promotion.

6. MMP expression in CD patients is lower than in UC patients

Remarkably, while both CD and UC patients have a generally increased expression and activity of MMPs, patients with CD develop strictures much more often than UC patients.5 Therefore, we reviewed in more detail whether there are differences between the expression of MMPs and TIMPs in CD compared to UC patients [Table 4].

Table 4.

Expression and activity of MMPs and TIMPs in CD tissue compared to UC tissue

| Gene | Protein | Activity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagenases | |||

| MMP-1 | ↔57, ↓70 | ↓58 | |

| MMP-13 | ↑35 | ↓60 | |

| Gelatinases | ↓71 | ||

| MMP-2 | ↓57 | ↓34 | ↔34, ↑72 |

| MMP-9 | ↓70 | ↔34 | ↓34,72 |

| Stromelysins | |||

| MMP-3 | ↓57,58 | ↔63 | |

| MMP-10 | ↔35 | ||

| Macrophage elastase | |||

| MMP-12 | ↔35, ↓70 | ||

| Membrane-bound MMPs | |||

| MMP-14 | ↔57 | ||

| TIMPs | |||

| TIMP-1 | ↔57 | ↔63 | |

| TIMP-2 | ↔57 | ↔58 | |

↑ = increased expression or activity in tissue from CD patients compared to UC tissue.

↓ = decreased expression or activity in tissue from CD patients compared to UC tissue.

↔ = similar expression or activity in tissue from CD patients compared to UC tissue.

In inflamed CD mucosa, there is a lower gene expression of MMP-2 and -3 compared to UC, whereas MMP-1 and -14 and TIMP-1 and -2 are not differently expressed.57 Lawrance et al. showed that gene expression of ECM proteins and several MMPs [MMP-1, -3, -9, and -12] were overexpressed in full-thickness colon tissue of UC patients compared to CD patients.70 A slightly lower MMP-2 and -9 protein expression and activity was found in CD vs UC intestinal mucosa, but this was not significant.34 RNA-seq of UC and CD mucosa did not reveal differences in MMP or TIMP gene expression.61 Similar results have been obtained by Bailey et al., in which they also showed an increased MMP-2 and a decreased MMP-9 expression in both mucosa and muscularis of uninflamed CD intestine compared to UC intestine.55 Total MMP-1 activity was found to be lower in CD mucosa compared to UC, whereas TIMP-2 expression was higher.58 Baugh et al. also showed a lower gelatinase [MMP-2 and -9] expression in CD compared to UC.29 Another study found that MMP and TIMP expression and activity were very similar between UC and CD mucosa, and only MMP-1 activity was lower and TIMP-2 protein expression was higher in CD mucosa compared to UC mucosa.26 In CD mucosal explant cultures, protein expression of active MMP-1, -2, and -3 was lower compared to UC mucosal explant cultures.27 Differences in serum levels of ECM degradation products were also found between CD and UC patients.72 VIMC [vimentin degradation product of MMP-2 and -8] levels are higher in CD patients compared to UC patients, while C3M and BGM levels are higher in UC patients.72 No differences between serum levels of C1M, C4M, and C5M were found in CD vs UC patients.73,74

The results described above show an altered expression and activity of ECM remodelling MMPs in CD compared to UC patients. Interestingly, CD patients, who are more prone to developing fibrosis, show a generally lower expression and activity of MMPs compared to UC patients, who are less prone to developing fibrosis. Whether lower MMP activity in CD vs UC patients indeed is [one of] the reasons for the higher prevalence of fibrosis in CD patients is not known. What should be taken into account is that MMP expression and activity are generally lower in the ileocecal region compared to the colon.62,69 Since ileocecal inflammation is often present in CD patients, while UC is characterized by colonic inflammation, direct comparison between these two patient groups might fall short.5 In CD patients, stenosing and stricturing disease is more often present in patients with ileal or ileocolonic disease compared to patients with colonic involvement only.75,76 Stricture development thus seems to be location-specific. Since the luminal diameter of the terminal ileum is smaller than other parts of the intestine, stricture development might be symptomatic earlier in this region compared to other intestinal regions.6,77,78

Differences in MMP regulation between CD and UC patients might also be explained by differences in the type of inflammation [Table 5]. Inflammation is limited to the mucosa in UC, while CD inflammation is transmural. Moreover, CD is characterized by a Th1 immune response, while UC seems more Th2-driven.73 Although this separation is debatable, several studies have shown a higher expression of IFN-γ [Th-1 cytokine] in CD tissue compared to UC and healthy tissue, while IL-13 [Th-2 cytokine] is expressed at similar or lower levels in CD tissue compared to UC tissue.73 CD is also characterized by higher IL-17A levels, indicating active Th-17 inflammation as well.73,79 This results in the expression and activity of different cytokines, which may alter MMP expression and activity.

Table 5.

In vitro effect of Th-1, -2, and -17 cytokines on MMP expression

| In vivo | In vitro | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-/anti-fibrotic | Expression in intestinal fibrosis | mRNA | Protein | |

| Th-1 cytokines | ||||

| IFN-γ | Anti-fibrotic | ↑ MMP-1; ↔ MMP-9 and TIMP-1 |

||

| TNF-α | Pro-fibrotic | ↑ MMP-1; ↔ MMP-9 and TIMP-1 |

↑ MMP-1 | |

| Th-2 cytokines | ||||

| IL-4 | Pro-fibrotic | Not studied | ↑ MMP-1; ↓ MMP-9 | |

| IL-13 | Pro-fibrotic | ↑ muscle | ↔ MMP-1; ↓ MMP-9 | ↓ MMP-1 and -2 |

| Th-17 cytokines | ||||

| IL-17A | Pro-fibrotic | ↑ muscle | ↑ MMP-1; ↔ MMP-9 and TIMP-1 | ↑ MMP-1, -3, and -12 and TIMP-1 |

| IL-22 | Pro-fibrotic | ↔ MMP-1 and -9 and TIMP-1 | ||

| IL-23 | Pro-fibrotic | ↑ MMP-1 and -9 and TIMP-1 | ||

| Treg | ||||

| IL-10 | Anti-fibrotic | Not studied | ↑ MMP-1; ↔ TIMP-1 |

↑ = increased expression compared to control.

↓ = decreased expression compared to control.

↔ = similar expression compared to control.

The Th-1 cytokine IFN-γ alone does not influence MMP-9 expression in vitro cultured intestinal fibroblasts but suppresses TNF-α- and IL-1α-induced expression of MMP-9.80 In intestinal epithelial cells, IFN-γ induces expression of TIMP-.80 Interestingly, the Th-2 [but not Th-1] cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 and the Th-17 cytokine IL-17A promote intestinal fibrosis development.71,74,81IL-13 gene expression is upregulated in the muscle of CD strictures,55 but no differences in IL-13 production of muscularis explants overlying strictures were found.82 On the other hand, both studies found higher expression of IL-13Rα1 in isolated cells from tissue overlying strictures compared to control tissue.55,82 Stimulation of intestinal muscle fibroblasts causes decreased pro-MMP-1 and -2 synthesis.55 Filidou et al. also showed that Th-2 cytokines [IL-4 and IL-13] decreased MMP-9 mRNA levels in intestinal myofibroblasts, but also showed that IL-4 alone increased MMP-1 gene expression.83

Expression of the Th-17 cytokine IL-17A is increased in fibrotic muscle vs non-fibrotic muscle of CD patients.84 Stimulation with IL-17A causes an increase in MMP-3 and -12 and TIMP-1 expression in fibroblasts isolated from fibrotic, non-fibrotic, and control intestine.84,85 Other Th-17 cytokines, e.g. IL-22 and IL-23, have different effects on intestinal myofibroblasts. While IL-22 did not affect MMP-1 or TIMP-1 expression, IL-23 induced MMP-1 and TIMP-1 expression in intestinal fibroblasts.83

Thus, it seems that there is a different regulation of MMPs and TIMPs in CD vs UC, which might be caused by a different type and/or location of intestinal inflammation. Unfortunately, there is little literature on the role of MMPs in different regions and layers of healthy and IBD intestines and how these could promote intestinal fibrosis.

7. MMP expression in intestinal fibrosis

MMPs have diverse roles in organ fibrosis. In the first place, it is logical to assume that MMP activity is lower during fibrosis development and established fibrosis, as this would explain excessive ECM accumulation. However, MMPs can also have a pro-fibrotic role, for instance through activating TGF-β by MMP-2 and -9 or by promoting epithelial–mesenchymal transition [EMT] by MMP-3.14,86 In the next section, the current literature on MMP and TIMP expression and activity in fibrotic vs inflamed or control CD specimens is reviewed [Table 6].

Table 6.

Expression and activity of MMPs and TIMPs in fibrotic intestine compared to non-fibrotic control tissue

| Gene | Protein | Activity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagenases | |||

| MMP-1 | ↑30 ↑51 |

↑ submucosa and muscularis30, ↑ muscularis and mucosa55, ↔ mucosa30, inflamed fibrotic mucosa58, ↔31 |

↔ inflamed fibrotic mucosa58 |

| MMP-8 | ↔31 | ||

| Gelatinases | |||

| MMP-2 | ↔ inflamed fibrotic mucosa58 | ↑ mucosa55, ↔ inflamed fibrotic mucosa58, ↔ muscularis55 |

|

| MMP-9 | ↔30 | ↑ mostly mucosa and submucosa31, ↔ inflamed fibrotic mucosa58 |

↔muscle and mucosa [increased compared to cancer control]55, ↔ inflamed fibrotic mucosa58 |

| Stromelysins | |||

| MMP-3 | ↑ 28, 54 | ↑ mucosa [less pronounced], submucosa and muscularis30 ↔ inflamed fibrotic mucosa58 |

↔ inflamed fibrotic mucosa58 |

| Membrane-bound MMP | |||

| MMP-14 | ↑51 | ||

| TIMPs | |||

| TIMP-1 | ↔,30 ↑51 |

↑ muscle55, ↔ mucosa55, ↔inflamed fibrotic mucosa58 |

|

| TIMP-2 | ↔ inflamed fibrotic mucosa58 | ||

↑ = increased expression or activity in fibrotic tissue from CD patients compared to control tissue.

↓ = decreased expression or activity in fibrotic tissue from CD patients compared to control tissue.

↔ = similar expression or activity in fibrotic tissue from CD patients compared to control tissue.

No differences in expression and proteolytic activity of MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9, nor in the expression of TIMP-1 and -2 were detected between inflamed fibrotic CD mucosa and inflamed non-fibrotic CD mucosa.26 In contrast, others found differences when non-inflamed fibrotic CD tissue was compared to control or inflamed CD tissue. In general, it was found that TIMP-1 expression is increased in the fibrotic [both mucosa and muscularis] intestine compared to non-fibrotic CD intestine and non-IBD controls.55,66 Interestingly, MMP-1 and -14, as well as TIMP-1 expression, were significantly increased in full-thickness fibrotic terminal CD ileum when compared to non-fibrotic and non-CD controls.51 Warnaar et al. also found that MMP-1 and MMP-3 are upregulated in muscularis and submucosal tissue of the fibrotic intestine. MMP-1 was not differentially expressed in the mucosa, but increased in the submucosa and muscularis of stenotic CD intestine compared to controls, while MMP-3 expression was increased in all intestinal layers.30 Pro-MMP-1 was shown to be increased in both muscularis and mucosa of the fibrotic CD intestine compared to controls and inflamed intestine. MMP-9 activity was not altered whereas MMP-2 activity was increased in the mucosa, but not in the muscularis.55 Bailey et al. detected higher expression of stromelysins [MMP-3 and -10] in areas of SMC proliferation, suggesting a pro-fibrotic role for these MMPs by promoting migration and the ability of SMCs to invade the submucosa.31 Altogether, it appears that the expression and activity of several MMPs [collagenases, gelatinases, as well as stromelysins] are increased in fibrotic intestinal tissue compared to non-fibrotic tissue. However, at the same time, TIMP-1 expression is also increased51,55,66 and thus could counteract the increased MMP expression in vivo. Unfortunately, the expression of MMPs is not well studied in layers of the human intestine other than the mucosa.

As a measure of the formation and degradation rates of ECM, ratios between MMPs, TIMPs, and collagens have been used. Warnaar et al. showed that MMP-1/TIMP-1 and MMP-3/TIMP-1 ratios were increased in fibrotic terminal ileum compared to controls, but similar to proximal resection margins. MMP-9/TIMP-1 was found to be similar in fibrotic terminal ileum compared to controls,30 suggesting that ECM breakdown may take place at the same pace in fibrotic vs non-fibrotic regions. Possibly, the increased collagen production is not compensated for by increased ECM breakdown. Indeed, the MMP-1/collagen synthesis ratio was found to be lower in fibrotic muscularis compared to uninflamed CD and inflamed UC.55 This indicates that the increased MMP expression is not sufficient to compensate for the increased collagen expression.

The expression of MMP and TIMP genes and proteins does not translate 1-to-1 to their actual activity in the tissue, since this is highly regulated at a post-translational level. To determine the balance of ECM remodelling more closely, the ratio between ECM formation products and ECM degradation products by MMPs can be determined. Interestingly, when formation and degradation products of type I, III, V, and VI collagen were determined in the serum of CD patients, the balance of type I and III collagens in CD patients with stricturing disease [Montreal class B2] pointed more towards collagen degradation when compared to healthy controls. On the other hand, type V collagen formation/degradation balance was more towards formation in CD patients with stricturing disease compared to healthy controls, while the type VI balance was unchanged.68 Bourgonje et al. also measured serum levels of Pro-C3 and C3M, but in contrast to van Haaften et al. did not find a difference in C3M/Pro-C3 ratio in the serum of Montreal B2 CD patients compared to healthy controls. They did find an increase in Pro-C4/C4M ratio, C1M, and C6Ma3 serum levels in Montreal B2 CD patients compared to healthy controls.67 A reason for these different results might be the difference in patient inclusion/exclusion criteria. For example, van Haaften et al. only included CD patients with ileal disease [L1], while Bourgonje et al. did not specifically include or exclude patients with different disease locations. Interestingly, it has been shown previously that disease location might influence serum levels of another MMP-degraded ECM protein [BGM].69 It might be difficult to specifically find differences between Montreal B2 [stricturing], B1 [inflammatory], and healthy controls since the formation and degradation products were measured in patients’ serum, which does not necessarily represent the activity at the specific part of the intestine. It is therefore possible that inflammation in other parts of the CD intestine masks the alterations at the fibrotic region.68 When B1 and B2 phenotypes are compared, only the collagen IV formation rate [ProC4/C4M ratio] appears different [increased] in the serum of B2 patients compared to B1 patients.67 Together, these results suggest higher MMP-2, -9, -12, and/or -13 activity in CD patients with stenosis.

8. In vitro studies

Fibroblasts are considered to be the main cell type involved in ECM production and remodelling during fibrosis and fibrogenesis. MMP expression of fibroblasts has been studied from three different perspectives, namely the fibroblast source, culture conditions, and exposure to soluble factors [pro-fibrotic molecules]. Of note, it is not always clear whether the authors used fibroblasts or myo-fibroblasts since these terms are not consistently used between the various papers. However, as described before, many fibroblast subtypes exist and one subtype might [and can] differentiate into another, also during culture. Depending on culture conditions, ‘spontaneous’ differentiation from fibroblasts [α-SMA−] to myofibroblasts [α-SMA+] does occur in culture and is not always mentioned or verified in scientific publications. This is probably the case when culturing isolated fibroblasts from the normal, or healthy intestine since α-SMA is normally only detected in the muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria, and not in areas with fibroblasts [epithelial lining, lamina propria, or submucosa]45,87

First, MMP and TIMP expression is different between control, inflammatory, and fibrotic tissue-derived fibroblasts [Table 7].66,84 De Bruyn et al. showed lower expression of MMP-3, -10, -11 and -24, and increased expression of MMP-2 and TIMP-1 and -2 in myofibroblasts from stenotic tissue compared to non-stenotic myofibroblasts, while no difference was observed for MMP-1, -16, and -17 expression. Moreover, MMP-2 and MMP-3 activity were higher in stenotic myofibroblasts compared to inflamed and normal myofibroblasts.53 McKaig et al. showed significantly increased expression of TIMP-1 by stenotic myofibroblasts from CD patients compared to UC myofibroblasts and control myofibroblasts, but they did not detect differences in MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 expression.88 Thus, myofibroblasts isolated from healthy, inflamed and stenotic regions of the intestine are different and express MMPs and TIMPs differently. MMPs can be either higher or lower expressed in fibrotic myofibroblasts compared to normal myofibroblasts, whereas TIMPs are more highly expressed in stenotic myofibroblasts. This indicates that there is in general lower ECM degradation activity by myofibroblasts from stenotic regions compared to myofibroblasts from the healthy or inflamed regions.

Table 7.

In vitro MMP and TIMP expression

| Fibroblast source | Comparison | mRNA | Protein | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stenotic | Stenotic vs non-stenotic fibroblasts | ↔ MMP-1, -16, and -1753; ↓ MMP-3, -10, -11, and -2453; ↑ MMP-2 and TIMP-253; ↑ TIMP-166,88 |

↓ MMP-1266,84; ↔ MMP-366,84; ↑ TIMP-166,88; ↔ TIMP-184; ↔ TIMP-288 |

↓ MMP-1266 ↑ MMP-2 and -353 |

| Normal | Plastic vs matrix cultured fibroblasts | ↑ MMP-389 | ↑ MMP-2 | |

| Ccd-18Co | Plastic vs matrix cultured fibroblasts | ↑ MMP-3 | ↑ MMP-271 | |

| Normal | Increasing stiffness | ↑ MMP-353 | ||

| Stenotic | Increasing stiffness | ↓ MMP-353 | ||

| Ccd-18Co | Increasing stiffness | ↓ MMP-1 and -356 | ↓ MMP-353 |

↑ = increased expression or activity.

↓ = decreased expression or activity.

↔ = similar expression or activity.

Second, the influence of culture substrate and stiffness on MMP and TIMP expression has been studied in vitro. One reason for the different expression patterns in vitro compared to in vivo is the substrates on which intestinal fibroblasts are cultured. Fibroblasts are usually cultured on plastic or glass with a stiffness in the GPa range,90 while the stiffness of a healthy bowel is around 2.8–4.3 kPa and that of a stenotic bowel 28–30 kPa.53,91 Fibroblasts can react to different substrates and matrix stiffness via focal adhesions [FAs]. FAs are protein complexes that attach the intracellular cytoskeleton via transmembrane proteins, and integrins, to the ECM.92 Focal adhesion kinase [FAK], one of the FA proteins, is more highly expressed in fibroblasts isolated from the fibrotic intestine compared to controls.93 FAs are also known to be upregulated in fibroblasts grown on a stiff matrix, compared to fibroblasts grown on a soft matrix, and in myofibroblasts exposed to type XVI collagen.74,91 Subsequent downstream FA signalling [via Rho/ROCK] can be pro-fibrotic and also influence MMP and TIMP expression. Indeed, when Ccd-18Co fibroblasts [a human colonic fibroblast cell line] are cultured in a collagen I, hyaluronic acid, or fibronectin gel or agar, instead of normal plastic, this results in higher expression and activation of MMP-2.71 Moreover, when Ccd-18Co fibroblasts are cultured on acrylamide gels, MMP-1 and MMP-3 gene expression decreases with increasing gel stiffness, with the highest MMP expression on gels with a physiologically normal stiffness [4.3 kPa] and the lowest expression in gels with stiffness corresponding to that of the stenotic bowel [28 kPa].56 Primary intestinal fibroblasts also show upregulation of MMP-3 when cultured in decellularized human intestinal scaffolds compared to fibroblasts cultured on plastic.89 Interestingly, de Bruyn et al. showed that primary myofibroblasts isolated from normal, inflamed only, or stenotic intestines respond differently to matrix stiffness. As expected, when cultured on a stiff collagen-coated matrix, normal myofibroblasts increase their MMP-3 activity. In contrast, myofibroblasts from the stenotic intestine decreased their MMP-3 activity on a stiff matrix. These authors showed a similar response to matrix stiffness in Ccd-18Co fibroblasts, suggesting that these cells represent stenotic fibroblasts.53 Taken together, the expression and activation of MMPs are dependent on the [myo-]fibroblast source, but also on the environment in which they are cultured. In future studies, fibroblast sources, as well as fibroblast culture substrate, should be carefully chosen and documented. To set up good in vitro models using intestinal fibroblasts, proper comparisons between in vitro and in vivo expression of MMPs and TIMPs in different circumstances should be made.

Lastly, fibroblasts are cultured in the presence of pro-fibrotic factors to delineate the molecular mechanisms involved in intestinal fibrosis. Here we will focus on TGF- β1 and its role in MMP and TIMP regulation in intestinal fibroblasts.

TGF-β1 is upregulated in the fibrotic intestine and isolated fibroblasts [Table 8].66,84 It is well known that TGF-β1 plays an important role in the wound healing response and that TGF-β1 acts as a pro-fibrotic signalling molecule. Also in the intestine, TGF-β isoforms [1, 2, and 3] are differentially expressed in CD mucosal samples and isolated fibroblasts.81,94 In particular, TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 mRNA were more abundant in macrophages and fibroblasts in the lamina propria of CD intestines compared to normal intestines.81 In the fibrotic CD intestine, the protein expression of TGF-β1 is increased in all layers of the intestine compared to inflamed UC as well as control intestines.50 Interestingly, in primary fibroblasts from CD patients with stenosis, TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 expression is increased, while TGF-β3 expression is decreased compared to normal fibroblasts.94 When normal fibroblasts are treated with TGF-β1 or TGF-β2, TIMP-1 expression is increased, while treatment with TGF-β3 does not affect TIMP-1 expression, suggesting a pro-fibrotic role for TGF-β1 and TGF-β2.88 No effect of TGF-β on MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 expression was found in Ccd-18Co intestinal fibroblasts.71 In conclusion, TGF- β1 might influence decreasing ECM breakdown, by increasing the expression of TIMPs.

Table 8.

Role of TGF-β in vitro expression of MMPs and TIMPs

| In vivo | In vitro | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro/anti-fibrotic | Expression in intestinal fibrosisa | mRNAb | Proteinb | |

| TGF-β1 | Pro-fibrotic | ↑ | MMP-1 ↔; TIMP-1 ↑ | MMP-2 and TIMP-1 ↑; MMP-3 ↔; MMP-9 ↑; MMP-12 ↓ |

| TGF-β2 | ↑ | TIMP-1 ↑ | ||

| TGF-β3 | Anti-fibrotic | ↓ | TIMP-1 ↔ | |

↑ = increased expression compared to control.

↓ = decreased expression compared to control.

↔ = similar expression compared to control.

aCompared to non-fibrotic control.

bCompared to non-treated control.

A major limitation of in vitro studies using [myo-]fibroblast cultures is that freshly isolated primary [myo-]fibroblasts are different from [myo-]fibroblasts cultured in vitro for longer periods [higher passage] Moreover, isolation methods influence the yield and type of fibroblasts that are isolated.95,96 The absence or presence of an advanced culture substrate, stress/strain, flow/shear, topography, and specific stiffness does influence the cellular response to stimuli.90,97,98 For example, the ACTA2 and TGF-β1 gene expression of primary intestinal myofibroblasts cultured in two dimensions [2D] [conventional plastic] did not change upon stimulation with TGF-β1, while the same myofibroblasts cultured in decellularized duodenum matrix did show a significant increase in ACTA2 and TGF-β1 gene expression upon TGF-β1 stimulation, showing the importance of the presence of a 3D environment.89 Moreover, using primary intestinal fibroblasts, it has been shown that the stiffness of the culture substrate influences fibroblast morphology, proliferation rate, and expression of genes involved in matrix turnover, showing the importance of substrate stiffness.91 Fibroblast source [cell line, primary, healthy, inflamed, or stenotic] is of great influence on how fibroblasts respond to, for example, matrix stiffness.53 However, using mRNA expression analysis, these authors showed that, even when using the same selection criteria, isolation, and culture methods, gene expression between primary myofibroblasts from different patients shows different patterns.53 Currently, it is not known what would be the most representative culture method for the best translation of in vitro studies to the in vivo situation. Advanced models would probably have a better translational potential, but these models are usually more labour-intensive, more costly, and less robust than conventional models. Therefore, the model of choice depends on the research question. Moreover, researchers should be aware of the limitations that come with the experimental model they apply.99 Comparisons between available in vivo data and in vitro data will be necessary to validate the best models. However, as noted in the next section, we should further improve the data obtained from human studies.

9. Limitations of patient studies

As described above, apparent contradictory results have been described for MMP expression, localization, and activity in the healthy and fibrotic intestine. There are several reasons to explain this. First, the expression, localization, and activity of MMPs are determined in samples obtained from patients using different inclusion/exclusion criteria, from different locations in the small or large intestine, or from a different layer of the intestinal tissue. Control and affected tissues [inflamed, fibrotic, or both] are very heterogeneous, and not specified well in every study. In the case of the fibrotic intestine, the tissue might originate from the jejunum, ileum, or colon and can be inflamed or non-inflamed. This is not always described in detail, which makes a direct comparison between different studies difficult. Moreover, healthy tissue used as controls was obtained either from macroscopically or histologically non-affected resection margins of CD patients,30,51,55,58,64 and from non-CD controls with another underlying disease [UC or cancer].28,30,31,51,55,56 Microscopically normal intestines might still be affected by inflammatory conditions proximal to the normal-appearing intestine, as shown by Baugh et al., who showed that the expression and activation of MMPs were increased in both non-inflamed as well as inflamed IBD mucosa compared to controls.29 Moreover, histologically normal intestine from patients undergoing bowel resection due to colon/pancreatic cancer is very often used as a non-IBD control. However, tissue under the influence of cancer also has impaired ECM remodelling. Moreover, these patients may have undergone [chemo]therapy before surgery,17,100 which will also affect the intestinal mucosa. Second, MMP expression and activity vary between anatomical locations of the gut and between different tissue layers, again making a direct comparison between studies complicated. Third, current and earlier [drug] treatments of IBD patients might affect the expression and activity of MMPs and TIMPs. For instance, it has been shown that MMP-7, -9 and -26 and TIMP-1 and -3 are downregulated in specific cell types in patients after using immunosuppressive drugs.101 De Meijer et al. also showed downregulation of MMP-1 and -3 in mucosa after ex vivo exposure to infliximab, a commonly used anti-TNF-α-drug.27 Surprisingly, medication use is usually not addressed in the patient selection or taken into consideration in the data analysis. Lastly, the expression and activation of MMPs is very complex and tightly regulated.18,22 Contradictory results in MMP expression, activation, or localization using different analytical methods for MMP detection is therefore not surprising. It is thus important to clarify, especially when using antibodies against MMPs and TIMPs, which variant of the protein [pro-peptide or active form] is actually detected. Most of the above-described studies performed Western blot analyses, IHC, or ELISA using uncharacterized or unspecified antibodies. Using such antibodies, it is possible to detect other or fewer MMP conformations than assumed. Unfortunately, only one study has reported a direct comparison between different antibodies [against MMP-19 pro-peptide and MMP-19 hinge-region] detecting either pro-MMP-19 [before activation] or total MMP-19 [before and after activation]. When using these two antibodies, different expression patterns in IBD intestines were found, highlighting the importance of using well-defined detection methods.33

10. MMPs as drug targets

Depending on the pro- or anti-fibrotic role of a specific MMP, MMPs are considered as potential drug targets or therapeutic agents to treat intestinal fibrosis, for example by stimulating ECM breakdown or inhibiting cytokine and growth factor activation. Specific MMP antagonists are available, and other drugs do interfere with MMP and/or TIMP expression and activation. MMP inhibition can be obtained via several approaches, such as [broad-spectrum] small-molecule inhibitors, anti-MMP-antibodies, or micro-RNAs.17,102 In the context of intestinal fibrosis, only anti-MMP-9 antibodies have been evaluated as a potential treatment option.103 Indeed, treatment with anti-MMP-9 antibodies in an intestinal fibrosis mouse model resulted in less obstruction and better preservation of villi compared to isotype controls. Moreover, lower amounts of hydroxylated proline in collagens were found in anti-MMP-9-treated intestinal grafts compared to isotype controls.103 Unfortunately, measurements of MMP-9 activity in Montreal B2 CD patients have not yet been conclusive, since studies showed either an increase in all Montreal classes [B1, 2, and 3] in C3M serum levels compared to healthy controls68 or no difference between Montreal B2 and controls.67 Thus, MMP-9 activity might be more related to inflammation or CD in general rather than fibrosis. MMP-9 antagonists have been tested in CD and UC patients in several clinical trials, but these resulted in conflicting data due to differences in study endpoints, patient characteristics, and a small number of patients.104–107 It was suggested that MMP-9 antagonists might be favourable in specific patient groups. Still, more [human] pre-clinical evidence for the potential benefits of MMP-9 antagonists in intestinal fibrosis should be generated, since this has barely been studied so far.104 More generally, effective treatment by targeting MMPs will only be possible when the expression, activity, and function of the targeted MMP[s] is fully known. Moreover, the timing, location, and specificity of the doses might be crucial in the ultimate beneficial or harmful effect of such treatment.17,102

Currently used IBD medication has been shown to influence MMP expression and activity. In mucosal explant cultures, infliximab, an anti-TNF-α antibody, decreases MMP-1, -3, and -9 and TIMP-1 secretion. Interestingly, only tissues from patients with certain genotypes seemed to show decreased expression of these MMPs upon infliximab treatment.27 In biopsies of patients after anti-TNF-α treatment, the expression of MMP-7, -9, and -26 and TIMP-1 and -3 was lower compared to biopsies before treatment.101 At the gene expression level, decreased expression of almost all MMPs and TIMP-1 and -2, and increased expression of MMP-28 in CD patients after infliximab treatment has been shown.62 In the serum of patients treated with vedolizumab [an anti-α4β7-integrin] lower levels of C1M, C3M, C4M, and C6Ma3 were detected, indicating a lower activity of MMPs [MMP-2, -9, -12, and -13].108 Decreasing MMP activity in the above-mentioned cases [TNF-α- or α4β7-integrin inhibition] is probably caused by the anti-inflammatory role of these therapeutics. To the best of our knowledge, the effect of MMP activity by other commonly used CD treatments [mesalazine, azathioprine, corticosteroids] in CD patients has not yet been studied.

Interestingly, a retrospective study found that when immunomodulating drugs [azathioprine or anti-TNF-α therapy] are given early enough [≥6 months before first surgery] in CD patients, this can delay, but not prevent, disease phenotype changes [Montreal B1 to B2/3] and the time to the first surgery [which is usually needed for stricturing or penetrating disease].109 Unfortunately, when treatment is started [too] late, the need for intestinal surgery can no longer be reduced.8,109 Thus, as mentioned above, the timing of treatment to prevent intestinal fibrosis, either via direct or indirect targeting of MMPs, is very important. Early diagnosis, or prediction of changing disease phenotype using biomarkers, such as MMP-degraded collagens, could be helpful.

11. Concluding remarks

The specific roles of MMPs and TIMPs in intestinal fibrosis remain unclear, although some conclusions can be drawn. In general, gene expression of various MMPs is increased, or at least similar, in the fibrotic intestine in CD patients as well as in vitro models, while at the same time TIMP-1 is overexpressed. While overexpression has been shown for a few MMPs on the protein level, only one study showed increased MMP-2 activity.55 Thus, the MMP/TIMP balance might be shifted towards inhibition of ECM breakdown even whilst the MMP expression is increased. Remarkably, it appears that collagenases [MMP-1, -8, and -13] have not yet been studied thoroughly, while these are the only MMPs that can actually digest cross-linked collagens that accumulate during intestinal fibrosis. Thus, future studies should focus on the presence and activity of a broader range of MMPs and TIMPs, especially those involved in the degradation of cross-linked collagen. Since TIMP-1 can inhibit a broad spectrum of MMPs, it is logical to assume that the collagenase activity in vivo is inhibited. Indeed, MMP-1 activity was shown to be similar in fibrotic CD mucosa compared to controls. Higher expression of MMPs [e.g. MMP-1, -2, and -12] in fibrotic lesions might also have a pro-fibrotic effect since they also facilitate cell migration and chemokine processing.14 For instance, MMP-1 and -2 can activate latent TGF-β and MMP-9 and -12 can inactivate plasminogen. Future studies should elucidate how and when these MMPs act as pro- or anti-fibrotic factors. Expression of MMPs and TIMPs appears different in muscularis compared to mucosal tissue, but this is not been thoroughly studied. While muscularis and submucosa are probably more involved in intestinal fibrosis, the role of MMPs is still more extensively studied in mucosal tissue. In summary, new studies should be initiated that will generate knowledge about the pro- or anti-fibrotic role of MMPs in intestinal fibrosis. Interesting targets are MMPs that can activate latent TGF-β1, thereby promoting fibrogenesis [e.g. MMP-2, -9, -13, and -14110,111]; MMPs that can process plasminogen, thereby preventing activated plasminogen [plasmin] for processing ECM and activating pro-MMPs [MMP-2, -7, -9, -12, and -1933,100,112]; MMPs that specifically process cross-linked collagens [MMP-1, -8, and -13]; and last, but not least, inhibitors of MMPs [TIMPs, α2-macroglubulin, thrombospondin ½, and RECK17]. Future in vivo studies should be aware of the importance of [1] patient characteristics [e.g. medication and underlying disease], [2] selection of proper controls, [3] specifying the sample/tissue source [layer and region], and [4] antibody selection and specification.

Improvements in research techniques and analysis methods, for example in antibody specificity and single-cell omics, should help us to unravel the complex and diverse functions of MMPs in intestinal fibrosis, which could potentially lead to biomarkers and novel drug targets.

Key questions to be answered in new studies.

Which MMPs and TIMPs are differently expressed/active in fibrotic intestinal tissue?

How are MMPs and TIMPs differently expressed in the several intestinal layers and cells?

Which MMPs are considered pro- or anti-fibrotic in fibrotic intestine?

How can we study MMP and TIMP activity and function in a relevant experimental setting?

How can we steer MMP and TIMP activity towards fibrosis resolution without causing tissue damage?

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Groningen Research Institute for Pharmacy [GRIP] for providing the PhD scholarship position.

Contributor Information

Carin Biel, Department of Pharmaceutical Technology and Biopharmacy, University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

Klaas Nico Faber, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Ruud A Bank, Department of Pathology and Medical Biology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, 9713 GZ Groningen, The Netherlands.

Peter Olinga, Department of Pharmaceutical Technology and Biopharmacy, University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

C.B. collected and reviewed the current literature and drafted the manuscript. R.A.B., K.N.F. and P.O. critically read and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this review.

References

- 1. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Publ Gr 2015;12:720–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54.e42; quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Latella G, Rieder F.. Intestinal fibrosis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2017;33:239–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hovde O, Moum BA.. Epidemiology and clinical course of Crohn’s disease: Results from observational studies. World J Gastroenterol 2012;1723:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cosnes J, Gower–Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A.. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1785–1794.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rieder F, Latella G, Magro F, et al. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation topical review on prediction, diagnosis and management of fibrostenosing Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:873–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 2005;19(Suppl A):5A–36A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cosnes J, Nion-Larmurier I, Beaugerie L, Afchain P, Tiret E, Gendre J-P.. Impact of the increasing use of immunosuppressants in Crohn’s disease on the need for intestinal surgery. Gut 2005;54:237–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lawrance IC, Rogler G, Bamias G, et al. Cellular and molecular mediators of intestinal fibrosis. J Crohns Colitis 2015;11:j.crohns.2014.09.008. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burke JP, Mulsow JJ, O’Keane C, Docherty NG, Watson RWG, O’Connell PR.. Fibrogenesis in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:439–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shimshoni E, Yablecovitch D, Baram L, Dotan I, Sagi I.. ECM remodelling in IBD: innocent bystander or partner in crime? The emerging role of extracellular molecular events in sustaining intestinal inflammation. Gut 2015;64:367–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karsdal MA, Nielsen SH, Leeming DJ, et al. The good and the bad collagens of fibrosis – their role in signaling and organ function. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2017;121:43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sutherland TE, Dyer DP, Allen JE.. The extracellular matrix and the immune system: a mutually dependent relationship. Science 2023;379:eabp8964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giannandrea M, Parks WC.. Diverse functions of matrix metalloproteinases during fibrosis. Dis Model Mech 2014;7:193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O’Shea NR, Smith AM, OʼShea NR, Smith AM.. Matrix metalloproteases role in bowel inflammation and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:2379–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O’Sullivan S, Gilmer JF, Medina C.. Matrix metalloproteinases in inflammatory bowel disease: an update. Mediators Inflamm 2015;2015:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sagi I, Talmi-Frank D, Arkadash V, Papo N, Mohan V. Matrix metalloproteinase protein inhibitors: highlighting a new beginning for metalloproteinases in medicine. Met Med 2016;3:31–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaffney J, Solomonov I, Zehorai E, Sagi I.. Multilevel regulation of matrix metalloproteinases in tissue homeostasis indicates their molecular specificity in vivo. Matrix Biol 2015;44-46:191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pender SL, MacDonald TT.. Matrix metalloproteinases and the gut – new roles for old enzymes. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2004;4:546–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Bruyn M, Vandooren J, Ugarte-Berzal E, Arijs I, Vermeire S, Opdenakker G.. The molecular biology of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in inflammatory bowel diseases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2016;51:295–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ravi A, Garg P, Sitaraman SV.. Matrix metalloproteinases in inflammatory bowel disease: boon or a bane? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chakraborti S, Mandal M, Das S, Mandal A, Chakraborti T.. Regulation of Matrix Metalloproteinases: An Overview 2003;253;269–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nissinen L, Kähäri VM.. Matrix metalloproteinases in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1840:2571–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Macdonald TT, Pender SLF.. Proteolytic enzymes in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1998;4:157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duca L, Debelle L, Debret R, Antonicelli F, Hornebeck W, Haye B.. The elastin peptides-mediated induction of pro-collagenase-1 production by human fibroblasts involves activation of MEK/ERK pathway via PKA- and PI3K-dependent signaling. FEBS Lett 2002;524:193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meijer MJ, Mieremet-Ooms MAAC, van Hogezand RA, et al. Role of matrix metalloproteinase, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase and tumor necrosis factor-α single nucleotide gene polymorphisms in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:2960–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meijer MJ, Mieremet-Ooms MAC, Van Duijn W, et al. Effect of the anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibody infliximab on the ex vivo mucosal matrix metalloproteinase-proteolytic phenotype in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:200–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kirkegaard T, Hansen A, Bruun E, Brynskov J.. Expression and localisation of matrix metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors in fistulae of patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut 2004;53:701–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baugh MD, Perry MJ, Hollander AP, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase levels are elevated in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1999;117:814–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Warnaar N, Hofker HS, Maathuis MHJ, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases as profibrotic factors in terminal ileum in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:863–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bailey CJ, Hembry RM, Alexander A, Irving MH, Grant ME, Shuttleworth CA.. Distribution of the matrix metalloproteinases stromelysin, gelatinases A and B, and collagenase in Crohn’s disease and normal intestine. J Clin Pathol 1994;47:113–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedersen G, Saermark T, Kirkegaard T, Brynskov J.. Spontaneous and cytokine induced expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases in human colonic epithelium. Clin Exp Immunol 2009;155:257–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Červinková M, Horák P, Kanchev I, et al. Differential expression and processing of matrix metalloproteinase 19 marks progression of gastrointestinal diseases (matrix metalloproteinase 19/ inflammatory bowel disease/macrophages/colon cancer/endothelium/lymphatic vessels). Folia Biol 2014;60:113–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gao Q, Meijer MJW, Kubben FJGM., et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases-2 and -9 in intestinal tissue of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Liver Dis 2005;37:584–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vaalamo M, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Puolakkainen P, Kere J, Saarialho-Kere U.. Distinct expression profiles of stromelysin-2 (MMP-10), collagenase-3 (MMP-13), macrophage metalloelastase (MMP-12), and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP-3) in intestinal ulcerations. Am J Pathol 1998;152:1005–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sivertsson A, Lindströ E, Katona B, et al. Enhanced validation of antibodies enables the discovery of missing proteins. Cite This J Proteome Res 2020;19:4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bigaeva E, Uniken Venema WTC, Weersma RK, Festen EAM.. Understanding human gut diseases at single-cell resolution. Hum Mol Genet 2020;29:R51–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hong SN, Joung J-GG, Seol Bae J, et al. RNA-seq reveals transcriptomic differences in inflamed and noninflamed intestinal mucosa of Crohn’s disease patients compared with normal mucosa of healthy controls. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:1098–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Busslinger GA, Weusten BLA, Bogte A, Begthel H, Brosens LAA, Clevers H.. Human gastrointestinal epithelia of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum resolved at single-cell resolution. Cell Rep 2021;34:108819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martin JC, Chang C, Boschetti G, et al. Single-cell analysis of Crohn’s disease lesions identifies a pathogenic cellular module associated with resistance to anti-TNF therapy. Cell 2019;178:1493–508.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smillie CS, Biton M, Ordovas-Montanes J, et al. Intra- and inter-cellular rewiring of the human colon during ulcerative colitis. Cell 2019;178:714–30.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mortensen JH, Lindholm M, Langholm LL, et al. The intestinal tissue homeostasis–the role of extracellular matrix remodeling in inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;977:93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim SH, Turnbull J, Guimond S.. Extracellular matrix and cell signalling: the dynamic cooperation of integrin, proteoglycan and growth factor receptor. J Endocrinol 2011;209:139–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen W, Lu C, Hirota C, Iacucci M, Ghosh S, Gui X.. Smooth muscle hyperplasia/hypertrophy is the most prominent histological change in Crohn’s fibrostenosing bowel strictures: a semiquantitative analysis by using a novel histological grading scheme. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:92–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alfredsson J, Wick MJ.. Mechanism of fibrosis and stricture formation in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Immunol 2020;92:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rieder F, Brenmoehl J, Leeb S, Schölmerich J, Rogler G.. Wound healing and fibrosis in intestinal disease. Gut 2007;56:130–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Roulis M, Flavell RA.. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts of the intestinal lamina propria in physiology and disease. Differentiation 2016;92:116–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Graham MF, Diegelmann RF, Elson CO, et al. Collagen content and types in the intestinal strictures of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 1988;94:257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kodaira S, Hosoda Y, Tokyo SM.. Immunohistologic analysis of the extracellular matrix components of the fibrous stroma of human colon cancer. J Surg Oncol 1993;53:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lawrance IC, Maxwell L, Doe W.. Inflammation location, but not type, determines the increase in TGF-β1 and IGF-1 expression and collagen deposition in IBD intestine. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2001;7:16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]