Abstract

The stigmatization of people with pedophilia was previously identified as a “blind spot” in stigma research. This systematic review updates and expands on Jahnke and Hoyer’s 2013 review to understand (1) factors contributing to stigma toward people with sexual interest in children, (2) experiences of stigma, and (3) how stigma can be challenged and reduced. Thematic synthesis was used to analyze data from 35 studies from the United Kingdom, United States, The Netherlands, Germany, Canada, Norway, Australia, and New Zealand. Overarching themes were (1) misperceptions and stereotypes, (2) negative affective responses, (3) discrimination, (4) mental distress, (5) internalized public stigma, (6) negative effects of disclosure, and (7 and 8) informative and humanizing interventions. Findings highlighted substantial prevalence of stigma toward and amongst people with sexual interest in children, and methodological limitations of extant research. An agenda for future research is discussed, emphasizing how stigma can be challenged.

Keywords: Stigma, sexual interest in children, minor attraction, systematic review

Despite previous research highlighting prevalent public stigma surrounding pedophilia and its significant consequences for individuals affected (Jahnke & Hoyer, 2013), only a handful of studies have focused on ways in which stigma can be reduced. Understanding and addressing stigma surrounding sexual interest in children is paramount as stigma contributes to avoidance of help-seeking, which may increase risk of sexual abuse against children (Blagden et al., 2017). In their 2013 review, Jahnke and Hoyer found only a limited number of stigma studies surrounding both pedophilia and sexual offending directly related to the sexual interest, highlighting this as a “blind-spot” in contemporary stigma research. Jahnke and Hoyer identified a pressing need for more “theory-driven, methodologically robust and representative empirical studies” (p. 169) concerning stigma against people with pedophilia. They emphasized that the current literature lacked adequate theoretical grounding, validated stigma scales, commonly conflated sexual interest and sexual behavior, and featured small, biased participant samples. This review provides an update and expansion of their review, to identify the extent to which contemporary research has addressed this blind spot and inform an agenda for future research.

Sexual interest in children is a broad term used throughout this review to encompass both pedophilia and hebephilia. Pedophilia refers to sexual interest in prepubescent children (often between ages 3–10; Seto, 2017), whereas hebephilia refers to sexual interest in pubescent children (typically between 11 and 14 years; Blanchard et al., 2009). The current review thus focuses on stigma surrounding both pedophilia and hebephilia. Of note, the term minor attraction has recently gained traction and is self-selected by some people with sexual interest in children (B4U-ACT, 2019). Minor attraction encompasses pedophilic, hebephilic, and ephebophilic interests (sexual interest in adolescents typically between 15 and 17 years; Seto, 2017). None of these sexual interests are synonymous with sexually abusive behavior, which is an important and often overlooked distinction (Jahnke, 2018b).

Stigma is commonly defined as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting” that acts to reduce an individual “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (Goffman, 1963, p. 265). Stigma can manifest in cognitive, affective, and behavioral ways (Corrigan et al., 2012; Jahnke, Phillip, et al., 2015). Regarding sexual interest in children, stigmatization manifests in stereotyping, emotional responses (such as disgust, fear, and anger), and various discriminatory behaviors (such as social distancing and supporting imprisonment as form of prevention; Harper et al., 2018). This review considers two variations of stigma: (1) public stigma, in which members of the general public sanction negative attitudes and discrimination against persons who are different and thus devalued (Vogel et al., 2013), and (2) internalized or self-stigma, which refers to the internalization of negative societal attitudes. The latter involves three phases: having an awareness of the stereotype and agreeing with the stereotype and self-application (Corrigan et al., 2009).

The Jahnke and Hoyer (2013) review included quantitative empirical studies published in English, German or French. Of the 11 studies fitting their inclusion criteria, eight focused on “lay theories, stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination against people with pedophilia” (p. 169). They concluded that extant research was too limited and diverse to provide more than a rudimentary understanding, and only five studies featured pedophilia as the primary focus. However, they acknowledged the preliminary evidence supported the notion that pedophilia is a highly stigmatized characteristic. Jahnke and Hoyer noted that misperceptions, stereotypes, and discrimination surrounding people with pedophilia were prevalent among small samples of the general public and mental health practitioners. Misperceptions and stereotypes were identified through the endorsement of judgmental traits, beliefs of high rates of offending and pessimistic beliefs about treatability. Discrimination was characterized by strong rejection from students, less acceptance for treatment from psychotherapists and a general belief that people with pedophilia are to be evaded at all costs.

Jahnke and Hoyer (2013) highlighted that in addition to stereotypical representations in the media, an overall failure to distinguish between individuals who have sexually offended and individuals attracted to children may contribute to the public creating a direct link between sexual interests and sexually abusing a child. More specifically, no studies explicitly differentiated the two phenomena and it is possible that participants across studies might have responded to questions about people with pedophilia as if they were people who had offended. McCartan (2011) found that various professionals (academics, media associates, practitioners) had varied perceptions of pedophilia, which also included conflation. This confusion may impact the attitudes and willingness of treating practitioners, as well as the framing and discourse used by journalists which empowers stigmatization (McCartan, 2011). Only one study included in Jahnke and Hoyer’s review investigated professionals’ attitudes toward people with pedophilia. Jahnke and Hoyer proposed that negative attitudes may limit professionals’ willingness to offer treatment, but further exploration with professional samples was required.

Only three of the 11 studies included in Jahnke and Hoyer (2013) review considered effects of public stigma on people with pedophilia. They found evidence of negative attitudes surrounding their attraction as a result of public stigma. In addition, they found help-seeking behavior was limited (due to a fear of discovery), despite a general belief of potential benefits. Based on the few studies reviewed, Jahnke and Hoyer questioned whether perceived stigma increased self-isolation potentially increasing risk for offending. A recent review built upon their query and indeed found that negative outcomes associated with stigma-related stress are extensive and theorized to link to central risk factors for the initiation of sexual offending (Cantor & McPhail, 2016). Minority stress theory (discussed by Jahnke and Hoyer, 2013) describes this phenomenon. This theory was developed by Meyer (2003) to understand the prejudice and social stressors faced by individuals who identify as homosexual or bisexual and how these experiences can adversely impact mental health. It has been proposed that numerous consequences result from suffering discrimination, leading to amplified vigilance of expected stigma, the internalization of negative societal views, and efforts to hide one’s sexual interests (Meyer, 2003).

Contemporary studies demonstrate attempts to address Jahnke and Hoyer’s (2013) suggestion for more theory driven research. Harper (2016) proposed a modified social cognitive theory of attitudes in which a dual process of cognition assumes the use of two systems for processing information. “One of these systems is automatic and nonconscious in nature, enabling people to form rapid judgements with little cognitive effort. The second system involves people using conscious reasoning, and the evaluation of available information, before making a decision” (p. 29). Harris and Socia (2016) provided support for this theory, in which the “sexual offender” label elicited more punitive responses to adults and juveniles who have committed sexual offenses than the neutral descriptor “people who have committed crimes of a sexual nature.” They suggested the label triggers a “series of subconscious processes known as heuristics (cognitive shortcuts that facilitate rapid, intuitive judgments)” (p. 665). The social cognitive theory of attitudes emphasizes the importance of distinguishing intuitive (primarily affective based) responses from cognitive reasoning responses in both understanding and challenging stigmatizing attitudes. However, as this framework has been recently developed and is not widely utilized, labeling theory (Link et al., 1989), and the social cognitive model of stigma (Rüsch et al., 2005) were also drawn on throughout the current review to examine literature and interpret findings.

Aims of systematic review

Since Jahnke and Hoyer’s (2013) review, greater attention to people living with sexual interests in children has developed among researchers. Moreover, it appears that contemporary research has heeded at least some of their recommendations. It is therefore timely to take stock of what we know about stigma sounding sexual interest in children and how it is experienced. To the extent stigma toward these individuals remains poorly understood, attempts to challenge stigma are compromised and negative experiences on individuals affected continue. Moreover, individuals affected may struggle accessing help when needed, and society is no safer.

This review provides an update and expansion to the 2013 review conducted by Jahnke and Hoyer on lay theories, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination of people with pedophilia, and the effect of stigma on individuals with pedophilia. We widen the inclusion criteria to consider qualitative and mixed-methods research together with quantitative research (published after 2012) and considered contemporary research exploring ways to challenge public stigma. The inclusion of qualitative research was considered paramount as a systematic review of this literature is currently missing. The current review aims to identify and synthesize qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods empirical studies to understand:

Factors contributing to public stigma toward people with sexual interest in children;

The effects of stigma on people with sexual interest in children; and

The effectiveness of interventions designed to challenge public stigma surrounding sexual interest in children.

Methodology

Search strategy

Literature was first retrieved with a primary multidatabase key word search strategy in four major science and social science related databases. The database search incorporated ProQuest, Scopus, Web of Science, and Medline OVID for literature published from 2012 to March 2020. These databases were searched using a combination of the terms “stigma*” “attitude*” “stereotyp*” “label*” “discrimination” “prejudice” “social distance” “media” and the words “pedophil*” “paedophil*” or “minor attract*”. A full-text search via Google Scholar within the same date range was also conducted. The search was expanded through hand-searching references in the studies selected and their citations in the Web of Science Citation Index. This did not produce any additional search terms. A supplementary search for qualitative studies published prior to 2013 was conducted using the primary search strategy with the added term qualitative. This did not produce any additional studies. An independent gray literature search was not conducted as ProQuest incorporates gray literature (research that is either unpublished or has been published in non-peer reviewed form).

Inclusion criteria

Empirical studies or dissertations featuring sexual interest in children as the primary focus, written in English, which (1) explored factors of stigma toward persons with sexual interest in children; (2) the effects of stigma upon persons with sexual interest in children; and (3) challenging or reducing public stigma.

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies.

Exclusion criteria

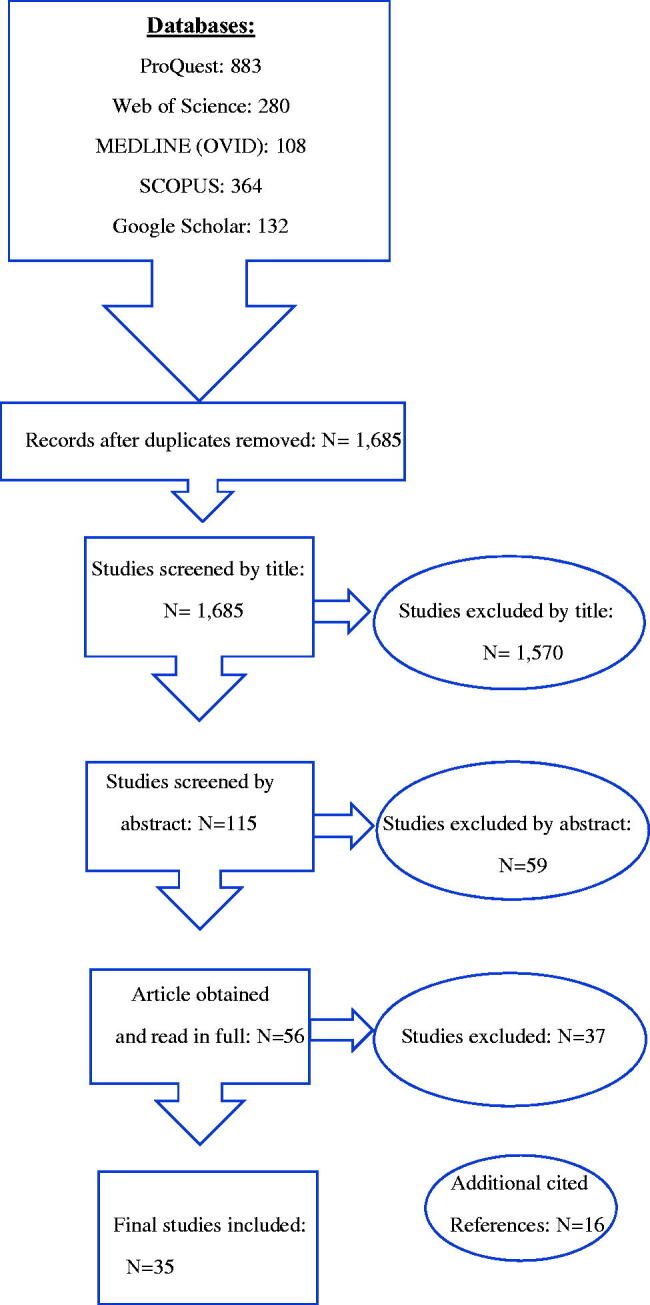

Research regarding sexual interest in children and sexual abuse against children has revealed a dubious tendency to obscure social, legal and psychopathological classifications (Feelgood & Hoyer, 2008). To avoid perpetuating this misperception, studies dealing with public, professional, or self-perceptions of individuals who have sexually abused children (Budd, 2011; Colson, 2018; Corabian, 2012; de Vel-Palumbo et al., 2019; Flynt, 2016; Greineder, 2012; Hancock, 2019; Harris & Socia, 2016; Hildembrand, 2019; King & Roberts, 2017; Kleban & Jeglic, 2012; Klein, 2015; Levenson et al., 2017; Malinen et al., 2014; Piché et al., 2016; Rosselli & Jeglic, 2017; Sandbukt, 2019; Thakker, 2012; Goodier & Lievesley, 2018; Bartram, 2018) were excluded unless the researchers specifically differentiated sexual interest in children from child sex offending, and asked about perceptions of the former. Finally, although important, studies which solely pertained to the coping mechanisms or therapeutic interventions for people with sexual interest in children who experience stigma were excluded), unless they focused on the perceived effects or reduction of stigma. One borderline study (Wurtele, 2018) was included. The study examined the impact of an educational intervention on perceptions surrounding sexual interest in children and child sex offending. Only findings pertaining to the former were included. Selected studies were imported into a bibliographic management software program, and duplicates removed. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of study selection process.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from selected studies: country, participant age and sex, sample size, recruitment strategy, study objective, methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and findings (online supplementary appendices OSM1 and OSM2).

Data synthesis

Thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, 2008) was used to summarize and analyze data from included studies. Thematic synthesis was selected for the purposes of this review for numerous reasons. First, it is well-suited to our objective of collecting existing evidence and identifying patterns within data. Second, whilst it is mostly associated with the synthesis of qualitative research findings, thematic synthesis is also used for the synthesis of quantitative research findings, particularly where there is heterogeneity in outcome variables and measurements. Finally, the process of thematic synthesis offers transparency in that findings are accessible preserving the principles of systematic reviews (Thomas & Harden, 2008). Thematic synthesis identifies central concepts across studies, even when diverse wording or explanations are used. Concepts are then drawn together in themes, endeavoring to go beyond the content of the original research (Thomas & Harden, 2008). The synthesis includes three stages, which were repeated for each of the three aims of the current review.

Stage 1: line-by-line coding of the findings from included studies.

Stage 2: development of descriptive themes.

Stage 3: generating analytical themes that ‘go beyond’ the findings of the original studies and generate new interpretive constructs, explanations or hypotheses (Thomas & Harden, 2008, p. 1).

The first author read the studies several times to ensure that all text relating to the three focus areas (factors contributing to stigma, effects of stigma and challenging stigma) were identified, integrated, and grouped into initial subthemes. Findings from both text and abstracts discussed or labeled “results” or “findings” were extracted (Thomas & Harden, 2008). All extracted text were read line by line and independently coded in a code-book document by the first author, who labeled meaning and content. The development of descriptive subthemes were identified during subsequent reading of the texts, and overarching themes were generated from subthemes. Subthemes were then reviewed by the second author and overarching themes were discussed and reviewed through a series of revisions. The thematic structure was finalized with helpful comments from an anonymous peer-reviewer.

Results

Included in the review were 20 quantitative, 11 qualitative and four mixed methods studies, making a combined total of 35 studies. The studies were carried out in Germany (n = 8), United States (n = 13), United Kingdom (n = 6), Canada (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), and Norway (n = 2). Of these studies, 12 had mixed international samples. None of the studies included were featured in the Jahnke and Hoyer (2013) review. All but two studies were conducted in subsequent years. These two studies were qualitative and thus did not meet Jahnke and Hoyer’s inclusion criteria. There were 17 studies that focused on contributing factors of public stigma and 14 studies focused on the experiences and effects of stigma amongst people living with sexual interest in children. Of these 31 studies, 10 explored how public stigma could be challenged or reduced, whereas only four featured this as their primary focus. In all, three themes, generated from 13 subthemes, characterized contributing factors of stigma toward sexual interest in children: misperceptions and stereotypes, negative affective responses, and discrimination. Three themes deduced from 15 subthemes were identified regarding the effects of stigma for people with sexual interest in children: mental distress, internalized public stigma, and negative experiences and effects of disclosure. Two themes of humanization and informative interventions were extrapolated from three subthemes as ways to challenge stigma. Findings (including subthemes) will be discussed as they relate to each aim of the review.

Contributing factors of public stigma toward people with sexual interest in children

Table 1 lists subthemes of contributing factors of stigma toward people with sexual interest in children. Results of the main themes are described in the following sections.

Table 1.

Subthemes of contributing factors of public stigma toward people with sexual interest in children.

| Subthemes | Jahnke, Imhoff, et al. (2015) | Imhoff (2015) | Imhoff and Jahnke (2018) | Harper et al. (2018) | Jahnke (2018) | Levenson & Grady (2019) | Campbell (2013) | Boardman & Bartels (2018) | Richards (2018) | Moss (2019b) | Wurtele (2018) | Montes (2018) | Gunnarsdottir (2018) | Serigstad (2016) | Hanson (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereotypes | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Negative affective reactions | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Perceived dangerous-ness | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Low levels of social acceptance | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Perceived deviance and un-trust worthiness | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Perceived intentionality | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Perceived un controllability | X(b) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Presence of labels | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Inevitability of offending behavior | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Desire for punitive punishment | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Perceptions of immorality | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Mis-perceptions or lay theories | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Therapists unwillingness to provide treatment | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Misperceptions and stereotypes

There were 17 identified studies which examined the link between misperceptions and/or stereotypes and public stigma. The theme misperceptions and stereotypes encompassed inaccurate causes and beliefs commonly held by the public regarding individuals with sexual interest in children. This theme was characterized by participants’ agreement with various statements featured in stigma and knowledge scales. The statements reflected perceived levels of dangerousness, deviance, choosing to have the sexual interest, inability to control acting upon the sexual interest, and inevitability of offending behavior. Within the qualitative and mixed methods studies, this theme was characterized by phrases suggestive that people with sexual interest in children have an inability to be treated, are inherently different from other people, are lying about their intentions of not acting upon their sexual interest, that their urges will escalate to action, and endorsements of other common stereotypes discussed below.

Although a considerable number of participants across studies believed sexual interest in children was a choice, most did not (e.g. Imhoff, 2015; Imhoff & Jahnke, 2018; Jahnke, Imhoff, et al., 2015). Within these studies, researchers suggested the view that sexual interest in children is innate, and therefore incurable, appeared to increase the degree of blameworthiness and untrustworthiness attributed to the individual. In addition, most studies found that most participants viewed the interest as uncontrollable which extended to individuals who had not acted on their interest. Consequently, findings illustrate participants made a strong connection between the sexual interest in children and the assumption of criminality, which highlights the stigmatization surrounding this sexual interest is reflected in cognitive conceptions of the ability to choose and control them. Similarly, in addition to perceptions of choice and controllability, studies found links between perceived danger and the assumption that sexual interest in children is synonymous with (the inevitability of) sexual abuse against children. In that, despite highlighting that no offending related behavior had occurred, six studies (see Table 1) found moderate to high levels of perceived dangerousness. Results suggested varying levels of stereotype endorsement, but most participants across studies believed that the terms pedophile and child sex offenders were interchangeable. Across all studies, the general public; social work, psychology, and psychotherapy students; and police trainee samples showed higher levels of various stereotype endorsements than samples of experienced professionals.

Wurtele (2018) suggested that widespread media attention in recent years featuring cases of adults serving in positions of authority (including religious advisors, coaches, and teachers both male and female) may have assisted in discrediting some common stereotypes (e.g., “dirty old man” and “stranger danger”). However, Richards’ (2018) results showed persistence of the “stranger danger” stereotype. Although results of these studies are largely consistent with previous literature on the common misperceptions (Jahnke & Hoyer, 2013), they advance on previous research by illuminating the cognitive processes that inform widely held conflicting perceptions. In addition, Imhoff and Jahnke (2018) and Imhoff (2015) used a labeling theory framework to highlight how the “pedophile” label plays a fundamental role in influencing moral judgments. Some results indicated that empirical accuracy is making its way into public consciousness, that is, many participants recognized that having a sexual interest in children is not something one can choose is in line with scientific evidence (Seto, 2008). However, despite the decrease in some stereotypes (e.g., “dirty old man”) and most participants holding accurate beliefs regarding choice, these do not appear to have reduced risk and danger misperceptions (Jahnke, Imhoff, et al., 2015).

Negative affective responses

This theme encompassed participants’ negative affective responses to individuals with sexual interest in children, and how these responses correspond to other factors which shape stigma. The theme was characterized by participants’ agreement with statements within scaling tools featuring anger, fear, disgust, and reduced pity or empathy used in six studies (see Table 1). Similar words were used to describe individuals with sexual interest in children in five qualitative and mixed methods studies (see Table 1). In addition, use of words like gross and pieces of shit were decidedly suggestive of disgust and reduced empathy.

Lower levels of negative affective responses were reported amongst three studies sampling experienced clinicians (Campbell, 2013; Moss, 2019 & Parr & Pearson, 2019), whereas the social work, psychology, and psychotherapy students, police trainees, and clinicians with little experience working with this population, featured in Montes (2018), Gunnarsdottir (2018), Hanson (2018), Jahnke et al. (2015) and Serigstad (2016) reported moderate to high negative affective responses.

High levels of anger, fear, and reduced pity were especially prevalent in the studies sampling the general public, despite the absence of offending behavior (Jahnke, 2018; Jahnke, Imhoff, et al., 2015). As in the misperceptions and stereotypes theme, perceptions of reduced controllability (which Jahnke, Imhoff, et al., 2015, hypothesized as virtually tantamount with accountability) associated with an increase in anger and reduction in pity. The levels of self-reported anger in these studies were considered high for something that the majority perceives as something one cannot choose. These findings provide support for the social cognitive theory of attitudes, in that, people’s subconscious (or affective) responses are triggered and used to make snap judgments about this group, despite holding empirically accurate information negating these judgments. Furthermore, results found that pity and anger were predictors of social distance, whereas fear was not. More specifically, anger was associated with higher levels of social distance whereas pity accompanied increased acceptance. Jahnke (2018) and Jahnke, Imhoff, et al. (2015) identified that female participants were more likely to experience fear and disgust than male participants and had a greater desire to punish. Participants who had young children below the age of fourteen had a higher probability to report fear and punitive attitudes than participants without or with older children.

Discrimination

The theme of discrimination was characterized by public participants statements or agreement with statements in surveys that reflected low levels of social acceptance (including personal interaction or acceptance), punitive judgments and punishments, and therapists’ unwillingness to provide treatment. There were 17 studies (see Table 1) that explored how these variations of discrimination contribute to stigma.

Consistent with the negative affective reactions, studies with general public samples found high levels of discrimination regarding personal interactions with individuals with sexual interest in children but some found low-moderate levels of punitive judgments and punishment. Imhoff (2015), Jahnke (2018), and Imhoff and Jahnke (2018) all found that discriminatory attitudes were not only predicted by the perceived association of attraction and offending behavior, but also by the perceived choice of the sexual interest and its nonconformity. They suggested that the confusion between the two phenomena is only a partial explanation of the public’s need to punish people with this attraction. Consequently, the attraction itself and not just its assumed criminality evokes a desire for punishment (Imhoff, 2015). These studies also indicated that higher social desirability is related to stronger discrimination. Thus, choice and social desirability as predictors of discrimination appear to have a direct relationship to the desire to conform to group norms and to punish those who deviate. Furthermore, the studies suggested that the desire to punish based upon an inherent difference correlates with deviance, fear, and (in Jahnke, Imhoff, et al., 2015) right-wing authoritarianism. Imhoff (2015) and Imhoff and Jahnke (2018) provided further evidence for a labeling effect, whereby the labels pedophile and pedophilia increased discrimination. Specifically, the pedophilia label held further adverse associations compared with a descriptive naming of the sexual interest.

Social work and psychology students and police trainees tended to report higher levels of discriminatory attitudes and an unwillingness to work with individuals with sexual interest in children (Gunnarsdottir, 2018; Hanson, 2018; Montes, 2018) compared to experienced professionals who overall, held more positive attitudes (Campbell, 2013; Jahnke et al., 2015; Moss, 2019b; Parr & Pearson, 2019). Reported reasons regarding unwillingness to provide treatment from clinicians who held negative attitudes included; an incapacity to suspend negative beliefs and judgments, fear of entanglement in legal situations, personal safety concerns (correlating the sexual interests with unpredictable behavior), and in some cases believing they are unable to be treated. The mixed results from professional samples links to previous themes, in that accurate knowledge, training and interaction impacts discriminatory attitudes and behavior. Furthermore, such an explanation also aligns with findings from studies with general population samples as they are less likely to have had exposure to people with sexual interest in children and form rapid judgements about them.

Effects of stigma on persons with sexual interest in children

Table 2 lists subthemes of effects of stigma on persons with sexual interest in children. Results of the main themes are described in the following sections.

Table 2.

Subthemes of the effects of stigma on people with sexual interest in children.

| Subthemes | Moss (2019a) | Lievesley et al. (2020) | Jahnke et al. (2015) | Cohen et al. (2020) | Freimond (2013 | Cacciatori (2017) | Cohen et al. (2018) | Muir (2018) | Cash (2016 | Grady et al. (2019) | Levenson & Grady (2019) | Houtepen et al. (2016) | Stevens & Wood (2019) | Walker (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative treatment experiences | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Negative assumptions of professional support | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Negative affective responses | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Low levels of self-esteem | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Perceived levels of limited public acceptance | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Internalizing perceived negative attitudes | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Isolation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Feeling misunderstood | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Difficulty forming new relationships | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Depression | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Suicidal ideation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Fear of discovery | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Negative (non-professional) responses to disclosure | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Identity secrecy | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Identity distress | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Experiences of discrimination | X | X | X | X |

Mental distress

The theme mental distress encompasses self-reported accounts from participants with sexual interest in children regarding forms of negative emotional and psychological impacts as a result of stigma. All 14 studies (see Table 2) exploring the effects of stigma identified significant mental distress was felt by individuals with sexual interest in children. Mental distress was characterized by self-reported depression, anger (at the public, themselves, and wider society), anxiety, despair, shame, grief, guilt, loneliness, isolation, and low self-esteem. Many participants spoke of despair as the most substantial challenge they faced in living with a sexual interest in children. This was described as a profound sense of loss for their future. Participants discussed grief for these losses which centered around a lack of intimacy, love, family relationships, and professional opportunities. Cohen et al. (2018) found that individuals with sexual interest in children with and without sex offense convictions self-reported comparable levels of mental distress, whereas the Jahnke et al. (2015) participants self-reported high levels of mental distress and social isolation, with lower levels of emotional coping than comparison samples. Cash’s (2016) sample had lower self-reported self-esteem and higher loneliness than comparison samples of the general public. A concerning number of participants featured in eight studies (see Table 2) self-reported either recent or chronic suicidality. Cohen et al. (2020) reported suicidal participants self-reported more reasons not to self-disclose compared with their non-suicidal counterparts and had higher scores on low self-esteem and social anxiety. Lievesley et al. (2020) found that higher levels of self-reported guilt and shame and lower levels of hope for the future were consistent with high levels of internalization of negative societal attitudes.

Internalized public stigma

The theme internalized public stigma was characterized by the absorption and self-application of negative messages or stereotypes. The theme encompassed participants’ accounts of negative public perceptions of social acceptance, identity distress manifested by identifying with negative attitudes and perceptions, and negative assumptions of the effects of disclosure in professional and personal capacities. Many participants featured in Cacciatori (2017), Cash (2016), Freimond (2013), Grady et al. (2019), Walker (2017), and Muir (2018) described internalizing the negative beliefs observed in society, which contributed to identification with the horrific perception that wider society holds, in that they were “deviant monsters” fated to offend. Many participants who had not acted upon their attraction reported being labeled as a pedophile, child abuser, sexual deviant, and monster by society in addition to their self-labeling of being “minor attracted.” They described that the labels made them feel misunderstood, ashamed, prejudged based on things that would never happen, unworthy of services, precriminals, dysfunctional, or perverts. This labeling contributed to self-reported mental distress such as guilt, self-loathing, and shame.

Several participants featured in the same studies above experienced substantial fear of their sexual interests being discovered, which they anticipated would result in discriminatory ramifications. Hypothesized ramifications included loss of employment and status within the community, fear of violent responses, and further isolation. This fear compelled many participants to actively evade suspicion, which negatively impacted their relationships. Participants across studies described feeling unsafe, fearing others’ perceptions and concern that they would be detested or rejected from those close to them and wider society. Participants described fear of exposure as a primary reason for not seeking therapy. They described internal conflict between wanting to engage in therapeutic services but choosing not to do so, due to the strongly held belief that society views those who identify as having a sexual interest in children as destined to offend. This belief corresponded to the perceived fear that the cost of disclosure would result in police involvement even with an absence of an offense.

Jahnke et al. (2015) suggested that persons with a sexual interest in children generate presumptions on how they are viewed by wider society based on media representations and a small number of people who express negative attitudes. Because of the internalization of these attitudes and an unwillingness to disclose their attraction, they are unable to determine how they are perceived. Thus, avoidance means they do not receive any corrective feedback. Findings support this claim, as the social distance many participants perceived the public wished to maintain was an overestimate when compared to the social distance results from the public sample in Jahnke, Imhoff, et al. (2015).

Negative experiences and effects of disclosure

The theme of negative experiences of disclosure encompassed individuals’ processes in the decision to disclose and the lived experiences when disclosing their attraction to others in personal and professional settings. Many participants across 11 studies (see Table 2) discussed the experienced effects of personal disclosure (family and friends), which included self-reported increased stress, feeling their attraction is misunderstood, the loss and strain of relationships, feeling intimidated through threats of violence, legal action and verbal abuse, and being outed to others without their knowledge. Some participants reported experiencing status loss and discrimination in areas including treatment options, education, work, living situation, church, and community. Participants in Houtepen et al. (2016) shared that the negativity they received upon personal disclosure contributed to secretive behavior.

Various participants across studies self-reported further mental distress as a result of using mental health services. Based on their sexual interest, they emphasized being judged, rejected, or ignored resulting in feelings of hopelessness, shame, and feeling unworthy of treatment. An overwhelming majority of participants across studies described experiencing a lack of understanding from inadequate professional care and observed a gap in both the services available to them and limited trained therapists to support those with an attraction to children. This gap was observed by individuals in the United States, Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, The Netherlands, and New Zealand (Cash, 2016; Freimond 2013; Houtepen et al., 2016; Jahnke et al., 2015; Lievesley et al., 2020; Muir, 2018).

Disclosure was a theme with dichotomous elements of both stress and relief. For many, resolving this conflict was only possible at a point of desperation. At this point, the cost of not disclosing was maximized and participants felt that there was no option but to disclose. The decision process entailed uncertainty as participants navigated the tension between fear of rejection and desire for support. Several studies (Cacciatori, 2017; Grady et al. 2019; Lievesley et al., 2020; Moss, 2019a; Muir, 2018) identified a problematic secrecy-stigma paradox, that is, stigma generates secrecy of the sexual interest, but wider exposure of the existence of the attraction is highlighted as an integral element of stigma reduction. However, it is important to acknowledge the existence of positive or neutral experiences of disclosure. In fact, many participants within the Cash (2016) and Freimond (2013) studies reported neutral or positive experiences of personal and professional disclosure, and just under half of the participants in Levenson and Grady’s (2019) study found formal assistance helpful. Characteristics of beneficial therapeutic encounters included knowledge about the attraction, nonjudgmental attitudes, and viewing clients in a person-centered and holistic way.

Challenging public stigma surrounding sexual interest in children

Table 3 lists subthemes of challenging public stigma surrounding sexual interest in children. Results of the main themes are described in the following sections.

Table 3.

Subthemes of challenging public stigma surrounding sexual interest in children.

| Subthemes | Theaker (2015) | Jahnke et al. (2015) | Gunnarsdottir (2018) | Parr & Pearson (2019) | Wurtele (2018) | Harper et al. (2018) | Harper et al. (2019) | Boardman & Bartels (2018) | Montes (2018) | Levenson & Grady (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education/informative materials | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Increased public visibility of individuals with minor attraction | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Humanizing narratives | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Informative interventions

The theme of informative interventions was extrapolated by examining the outcomes of studies which used this technique to challenge stigma surrounding sexual interest in children. This theme reflected findings associated with an increase in understanding, and an increase in empathy for individuals with sexual interest in children. Harper et al. (2018) and Wurtele (2018) saw educational interventions were effective in challenging assumptions and attitudes. Specifically, these studies found educational interventions were able to decrease negative affective responses and improve attitudes toward treatment by decreasing support for punitive punishment. In addition, Gunnarsdottir (2018) and Moss (2019b) both saw results suggesting that empirically accurate information regarding sexual interest in children could decrease negative affective responses, such as anger. However, the informative intervention provided to the Jahnke et al. (2015) sample of psychotherapists saw that despite an increase in empathy, there was no increase in a willingness to work with people with sexual interest in children. In addition, Harper et al. (2019) found providing fact-based information had mixed results and actually increased perceptions of deviance. In line with previous findings regarding choice and controllability, they suggested that presenting empirically accurate information may produce an attitude that people with these sexual interests are destined to offend due to an unchosen, unchangeable, and therefore untreatable sexual interest (Harper et al., 2019).

Several studies explored views of mental health professionals regarding individuals with sexual interest in children and how stigma toward them could be challenged. Numerous participants highlighted that the media offered potential to educate the public and decrease stigma by increasing understanding and decreasing judgment. Participants in Parr and Pearson (2019) discussed that education campaigns (through social media and sex education in schools) should emphasize the importance of the stable nature of the sexual interest, and behavioral choices and responsibility which shifts focus away from secrecy and shame. In addition, they suggest an increase in publicity may normalize the concept that understanding sexual interest in children is of more benefit to the community than condemning it. Participants also acknowledged that increased publicity would likely improve the visibility of services.

Humanization narratives

The theme of humanization narratives was also extrapolated from studies that explored avenues of challenging stigma. This theme reflected findings which were associated with an increase in empathy and a greater understanding of individuals with sexual interest in children. Boardman and Bartels (2018), Gunnarsdottir (2018), Harper et al. (2018), Harper et al. (2019), Jahnke et al. (2015), and Wurtele (2018) found narrative-based depictions of individuals with sexual interest in children had the effect of reducing stigmatization via the processes of humanization. These studies consistently found that presenting tangible and accurate representations of persons with sexual interest in children who had not offended (compared to conflating the attraction and offending) had a significant effect of improving attitudes toward this population, and support for preventative treatment services. Most studies that featured both humanizing narratives and educational interventions found the former was more effective in decreasing punitive attitudes and negative affective responses. However, Harper et al. (2018) found no such differences between a first-person narrative condition and an expert opinion condition. Although, they suggested that narrative presentation may be more effective in improving attitudes as the effect size was substantially greater in the narrative condition. Two studies showed the effects of narrative-based presentations led to long-term reductions in stigmatization through follow up surveys (Harper et al., 2019; Jahnke et al., 2015). Of note, most studies which featured a humanization narrative condition were conducted with psychology students or trainee psychotherapists, and only one sampled the general public (see Harper et al., 2019).

Theaker (2015) evaluated public responses on social media to Luke Malone’s This American Life radio segment entitled “help wanted.” This study provided preliminary insight as to whether (humanization narrative based) visibility of nonoffending individuals with sexual interest in children could challenge stigma. Theaker also explored willingness of prosocial behavior toward this population. Many commenters acknowledged their assumptions about the interest had been challenged and alluded to supporting the concept of intervention for self-identified individuals with sexual interest in children. However, frequent comments reflected disbelief of the existence of a nonoffending pedophile, implying the concept is not understood or accepted by members of the general public. All studies that explored ways of challenging stigma suggested that presenting humanized information about these individuals may lead to more accepting societal attitudes.

Discussion

This systematic review expands on the limited understanding of stigma found in the 2013 quantitative review. The inclusion of 36 studies (compared to the 11 in the 2013 review) found consistent evidence that stigma presents as a significant multifaceted issue. The addition of 11 qualitative, four mixed-methods studies, and gray literature included within this review added further richness to understanding stigma. (It should be noted that because of the search strategy of qualitative research prior to 2012, some literature may have been missed.) Findings showed strong stigmatizing assumptions, negative emotions, discrimination, and a desire to punish from the public and professionals on a widespread scale. Moreover, the review illuminated the effects of stigma upon individuals with sexual interest in children, including high levels of mental distress, increased social isolation and limited help-seeking behavior. Finally, a small number of empirical studies showed preliminary ways in which stigma can be addressed and reduced, which was a novel and important component of this review.

Contemporary research has addressed some of the limitations of stigma research highlighted by Jahnke and Hoyer (2013). The expanded enquiry includes larger and more representative professional and general public samples, a larger number of studies including sexual interest in children as the main focus, explicitly assessing perceptions of nonoffending people with sexual interest in children, wider application (or discussion) of theoretical frameworks, and some research assessing attitudes with newly developed stigma scales. Now that we know more about what contributes to stigma than we did in 2013, we are better equipped to challenge it. Although prominent themes related to stigmatization were identified, several studies were limited by various methodological issues expanded on next.

Methodological limitations of stigma research and implications for future research

In their 2013 review, Jahnke and Hoyer acknowledged no study had attempted to counteract confusion, as clarity between “pedophile” and “child sex offender” was lacking. Although some studies separated the two distinct phenomena (Imhoff & Jahnke, 2018; Jahnke, Phillip, et al., 2015; Jahnke, Imhoff, et al., 2015; Jahnke, 2018a), attitudinal tools used in a small number of studies (Attitudes Towards Sexual Offenders (ATS-21), Community Attitudes Toward Sex Offenders (CATSO), Perceptions of Sex Offenders (PSO), Moral Disengagement Towards Sex Offenders (MDS-SO) continued conflation by failing to provide definitional clarity and inexplicably interchanged the terminologies. For instance, studies were specifically designed to assess attitudes surround sexual interest in children, yet scales asked about attitudes toward “offenders” promoting the stereotype that people with sexual interest in children have or will offend. Thus, a limitation of extant research resides in the terminology used by researchers. Accurately identifying perceptions and attitudes is hindered when the target group are not clearly defined. Implications for future research include consistent definitional clarity of target groups and ceasing interchangeability, so as not to inadvertently contribute to stigmatizing misperceptions. In addition, utilization of validated scales which measure attitudes directly relating to perceptions of sexual interest in children are encouraged.

Through the lens of labeling theory, Imhoff and Jahnke (2018) and Imhoff (2015) identified how the “pedophile” label influenced negative perceptions of people with sexual interest in children. Lowe and Willis (2020) found similar effects in that offense-based labels like “sex offender” or “murderer” were associated with less willingness among community members to do volunteer work with these groups as compared to neutral person first language (e.g., “people who have committed crimes of a sexual nature”). To challenge labels and reduce their effects, we recommend that researchers use person-first language, particularly if it is to filter through to public discourse. Such a recommendation is consistent with bias-free language guidelines outlined in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (American Psychological Association, 2020). The recently released seventh edition of the Publication Manual differentiates person-first and identity-first language, which is of relevance to stigma surrounding sexual interest in children. The term minor attracted person, self-selected by some people with minor attraction (B4U-ACT, 2019), is an example of the latter. Although the Publication Manual endorses both person-first and identity-first language, the extent to which individuals who experience sexual interest in children embrace the “minor attracted person” label is unknown. Accordingly, to prevent stigma that might result from assigning an unwanted label, we recommend cautious use of identity-first language until labeling preferences of people with sexual interest in children are better understood. Furthermore, ceasing the use of labels and conflation of sexual interest in children and child sex offending in future research is of importance for integrating the concept of the interest without criminality within public consciousness.

Statements used within measurement tools identifying perceptions and attitudes were often framed in a punitive manner, which may inadvertently reinforce underpinning punitive belief systems. The framing of questions and statements within measurement tools is of vital importance (particularly when challenging stigma) as evoking myths in an attempt to negate them, in fact, reinforces them (Schwarz et al., 2016). This is particularly true if the issue induces fear in people, and sexual interest in children continues to be what people fear the most (McCartan, 2010). Research on “valence framing” effects suggests that attitude intensity is increased by the use of negative frames (Bizer et al., 2011). Future scales may consider including statements such as people with sexual interest in children can control their interests, can achieve psychological wellbeing or can build relationships with adults. Moreover, to ensure that items within scales capture the range of possible underlying attitudes and do not inadvertently influence them, it is important that future research integrate findings from qualitative studies to inform the design of quantitative research.

Finally, future research should broaden stakeholder samples to include, for example, judges, doctors, teachers, school counselors, healthcare practitioners, public health workers, and pastoral workers. As these stakeholders hold a position of trust within the community, it is logical to assume that they may be confided in by individuals with sexual interest in children. Indeed, Levenson and Grady (2019) and Muir (2018) found that medical doctors, school counselors and religious advisors were amongst the professional stakeholders who were contacted for help from these individuals. Numerous studies identified a correlation between a lack of knowledge or training and higher levels of discrimination. Successful anti-stigma intervention efforts targeting trusted community members may have a significant impact in challenging general public stigma, given their potential influence. No study featured in the review measured genuine behavioral changes among professional stakeholders who received anti-stigma interventions. It is recommended that future anti-stigma research accounts for this gap, in order to gauge whether interventions result in lasting behavioral changes. Furthermore, despite a growing number of studies focused on attitudes (including behavioral intentions toward persons with convictions), only one study investigated whether the public would engage in proactive prosocial behavior toward persons with sexual interest in children. Future research may benefit from focusing on the general public’s behavioral intentions regarding earlier intervention, before harm is done.

Implicit attitudes and humanization interventions

Findings supported the modified dual processing of the social cognitive theory of attitudes (Harper, 2016) as the literature overwhelmingly indicated both the existence of prevalent stigma and negative affective responses informing a desire to punish even when the behavior and the attraction were distinguished. Thus, it appears that a cognitive awareness of the conceptual differences does not negate negative affective responses. Furthermore, the public engages in processes of othering of individuals with sexual interest in children and creates narratives which support and reflect this (Richards, 2018). A common misperception contributing to stigma was the belief that a lack of choice was connected to uncontrollability. This narrative seems exclusive to people with sexual interest in children and not other sexual interests. Researchers are encouraged to engage in stigma reduction messages that focus on the nature of choice and controllability of other sexual preferences. This focus may assist in the recognition that people with sexual interest in children can indeed control their sexual behavior.

Although research has highlighted how dual processing is understood and expressed (Harper, 2016), we know little about the origins of negative affective attitudes and limited focus has been placed on emotional aspects of the stigma surrounding sexual interest in children (Jahnke, 2018a). We recommend further research evaluates how implicit attitudes are prompted by subconscious value and belief systems and adopt a line of inquiry which seeks to better understand and target these systems. The promising results from the studies using first-person narrative humanization techniques to challenge stigma (Boardman & Bartels, 2018; Gunnarsdottir, 2018; Harper et al., 2018; 2019; Jahnke et al., 2015; Wurtele, 2018) may be engaging with people’s values and belief systems. Harper et al. (2018) stated that “challenging implicit-level cognitions may mean that snap judgments about this group may also be influenced, potentially leading to more rational and progressive social discourses” (p. 553). Rydell et al. (2007) explored how explicit (identifiable and controllable) and implicit (subconscious and uncontrollable) attitudes changed in response to counter-attitudinal information. They found that explicit attitudes were able to change quickly when presented with counter-attitudinal information, whereas implicit attitudes were slower to change postpresentation of counter-attitudinal information. They suggested that this shift was a result of the continued accumulation of information influencing the subject of the attitudes (Rydell et al., 2007). Indeed, the results from Harper et al. (2019) showed negative attitudes continued and even increased despite cognitive changes in understanding empirically accurate information regarding sexual interest in children. Thus, as attitudes regarding the attraction have developed over an extended period, repeated interventions are required to develop and sustain long lasting attitudinal changes. Ma and Loke (2020) identified that a combination of strategies were more effective for interventions reducing stigma related to people living with HIV/AIDS, as opposed to isolated strategies. A multifaceted approach may also be required for stigma reduction efforts surrounding sexual interest in children, as new information is often evoking of preceding beliefs (Rüsch et al., 2005).

Several quantitative studies within the review found participants endorsed a score of 3 on a 1–6-point Likert scale survey, indicating a lack of knowledge. For instance, the scale measuring social distance used by Imhoff (2015) showed a substantial number of participants were uncertain as to whether they would talk to an individual with sexual interest in children. Individuals who are uncertain of their perceptions and attitudes of this group may be highly valuable to involve in stigma reduction efforts, as they may be more open to accept empirically accurate information, and attitudinal changes may be quicker and more malleable.

Only one study used a humanization narrative with a general public sample, whereas the others featured students and mental health professionals. We recommend that future research make use of international general public samples to provide a more representative indication of whether narrative humanization is a viable method of reducing public stigma.

Implications for wider society and persons with sexual interest in children

At a wider society level, addressing structural discrimination is an integral component of targeting public stigma (Coleman et al., 2017; Corrigan et al., 2012). Although some stereotypes, such as “dirty old man” appeared to have been discredited, most studies found that inaccurate stereotypes maintained by the media (such as the interchangeability of the “pedophile” and “child sex offender” labels) remained within public consciousness (Gunnarsdottir, 2018; Harper et al., 2018; Jahnke, Imhoff, et al., 2015; Montes, 2018; Richards, 2018; Wurtele, 2018). Mass media interventions have shown to increase public knowledge and decrease discrimination in other fields (Clement et al., 2015). In addition, campaigns may challenge stereotypes commonly associated with sexual interest in children, such as dangerousness, choice to have the interest and controllability. For instance, promoting the knowledge that most individuals realize their attraction at puberty may assist with humanization efforts. Educational campaigns providing information on sexual abuse prevention, effective support for persons with sexual interest in children and reducing people’s reliance on affectively laden judgements may alleviate the paradoxical effects of stigma (Harper & Bartels, 2017). An increased awareness within the public consciousness appears paramount as findings suggest that internalization of stigma and associated fear of disclosure is what maintains stigma related distress, providing further support for minority stress theory. Goffman (1963) proposes that over time, familiarization and increased frequency of contact leads to normalization and acceptance of the difference present in a stigmatized individual or group. It could therefore be argued that increased visibility has the potential to reduce the effects of stigma by encouraging more individuals to disclose their attraction.

Literature pertaining to how individuals with sexual interest in children cope with the effects of stigma was beyond the scope of this review. We encourage future research to take stock of the humanitarian focus centering on how people with these sexual interests manage to live fruitful and offense-free lives, while coping with the stigma of their sexual interest (Cantor, 2014).

Conclusion

Research exploring stigmatization of people with sexual interest in children has important implications for sexual abuse prevention. However, the means of preventing sexual abuse against children has divided opinion, especially since as a society, we are largely preoccupied with punishment (Parr & Pearson, 2019). Future prevention efforts which challenge stigma are encouraged to focus on behavioral choice and controllability rather than shame and punishment, which are contributing factors to secrecy and an environment for potential offending. Stigma can be challenged and reduced. However, it is no simple endeavor to influence entrenched affectively laden attitudes (Malinen et al., 2014). This review highlighted promising means of influencing such attitudes, including humanizing narratives. These narratives provide a platform in which labels are challenged and enables public consideration of these individuals as people who can indeed control acting upon sexual interests. Positive social effects by means of the humanization of individuals with sexual interest in children has potential for the promotion and acceptance of preventative therapies, minimizing the harmful effects of self-stigmatization and reducing the risk of these individuals moving from the non-offending space to the offending space (Wilson & Jones, 2008).

Supplementary Material

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychological Association (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- B4U-ACT (2019). Learn: Know the Facts. B4U-ACT. https://www.b4uact.org/know-the-facts/

- Bartram, K. A. (2018). Does mental illness affect societal perception of sex offenders? [Master’s thesis, John Jay College of Criminal Justice]. CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_etds/63/

- Bizer, G. Y., Larsen, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Exploring the valence‐framing effect: Negative framing enhances attitude strength. Political Psychology, 32(1), 59–80. 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00795.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blagden, N., Lievesley, R., & Ware, J. (2017). Emotions and sexual offending. In Gannon, T. A., & Ward, T. (Eds.), Sexual offending: Cognition, emotion and motivation (pp. 71–88). Wiley Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, R., Lykins, A. D., Wherrett, D., Kuban, M. E., Cantor, J. M., Blak, T., Dickey, R., & Klassen, P. E. (2009). Pedophilia, hebephilia, and the DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(3), 335–350. 10.1007/s10508-008-9399-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, K. A., & Bartels, R. M. (2018). Using video stimuli to examine judgments of nonoffending and offending pedophiles: A brief communication. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(4), 333–342. 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1405300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd, K. (2011). Moral panics and changing sociolegal responses toward stigmatized outsiders: Public perceptions of convicted sex offenders and sex offender laws (Publication No. 3479316) [Doctoral dissertation, Purdue University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Cacciatori, H. (2017). The lived experiences of men attracted to minors and their therapy-seeking behaviors [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. Scholarworks. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4970&context=dissertations

- Campbell, J. (2013). Comparisons between psychology graduate students/trainees and licensed psychologists concerning general attitudes and perceptions of pedophiles (Publication No. 3615262) [Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, J. M. (2014). Gold-star” pedophiles in general sex therapy practice. In Binik Y. M. & Hall K. S. (Eds.), Principles and practice of sex therapy (5th ed., pp. 219–234).Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, J. M., & McPhail, I. V. (2016). Non-offending pedophiles. Current Sexual Health Reports, 8(3), 121–128. 10.1007/s11930-016-0076-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cash, B. M. (2016). Self-identifications. Sexual development, and wellbeing in minor-attracted people: An exploratory study [Master’s thesis, Cornell University]. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/45135/bmc87.pdf?sequence=1

- Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., Morgan, C., Rüsch, N., Brown, J. S. L., & Thornicroft, G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 11–27. 10.1017/S0033291714000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L., Ndukwe, N., Yaseen, Z., & Galynker, I. (2018). Comparison of self-identified minor-attracted persons who have and have not successfully refrained from sexual activity with children. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(3), 217–230. 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1377129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L. J., Wilman-Depena, S., Barzilay, S., Hawes, M., Yaseen, Z., & Galynker, I. (2020). Correlates of chronic suicidal ideation among community-based minor-attracted persons. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 32(3), 273–300. 10.1177/1079063219825868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, S. J., Stevelink, S. A. M., Hatch, S. L., Denny, J. A., & Greenberg, N. (2017). Stigma-related barriers and facilitators to help seeking for mental health issues in the armed forces: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Psychological Medicine, 47(11), 1880–1892. 10.1017/S0033291717000356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson, M. D. (2018). Sex offender perceptions: Investigating social supports as buffers to the consequences of Megan’s Law [Master’s thesis, Rowan University]. Rowan Digital Works. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/2622/

- Corabian, G. (2012). Collateral effects of the media on sex offender reintegration: Perceptions of sex offenders, professionals, and the lay public [Master’s thesis, University of Alberta]. Education and Research Archive. https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/6abb2916-73b5-47b0-8c20-d5210642b11f

- Corrigan, P. W., Larson, J. E., & Rüsch, N. (2009). Self‐stigma and the “why try” effect: Impact on life goals and evidence‐based practices. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (Wpa), 8(2), 75–81. 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, P. W., Morris, S. B., Michaels, P. J., Rafacz, J. D., & Rüsch, N. (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C..), 63(10), 963–973. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vel-Palumbo, M., Howarth, L., & Brewer, M. B. (2019). Once a sex offender always a sex offender’? Essentialism and attitudes towards criminal justice policy. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(5), 421–439. 10.1080/1068316X.2018.1529234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feelgood, S., & Hoyer, J. (2008). Child molester or paedophile? Sociolegal versus psychopathological classification of sexual offenders against children. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 14(1), 33–43. 10.1080/13552600802133860 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flynt, L. N. (2016). Law enforcement officers attitudes towards sex offenders and SORNA policies (Publication No. 10172475) [Doctoral dissertation, Capella University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. [Google Scholar]

- Freimond, C. M. (2013). Navigating the stigma of pedophilia: The experiences of nine minor-attracted men in Canada [Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University]. Summit. http://summit.sfu.ca/item/13798

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma and social identity. In Anderson, T, L. (Ed.), Understanding deviance: Connecting classical and contemporary perspectives (pp. 256–265). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goodier, S., & Lievesley, R. (2018). Understanding the needs of individuals at risk of perpetrating child sexual abuse: A practitioner perspective. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 18(1), 77–98. 10.1080/24732850.2018.1432185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, M. D., Levenson, J. S., Mesias, G., Kavanagh, S., & Charles, J. (2019). “I can’t talk about that”: Stigma and fear as barriers to preventive services for minor-attracted persons. Stigma and Health, 4(4), 400–410. 10.1037/sah0000154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greineder, B. (2012). Correctional officers’ perceptions of sexual offenders (Publication No. 3507629) [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsdottir, K. E. (2018). Attitudes toward people with pedophilia: Comparing the views of psychology students and police trainees in Norway [Master’s thesis, University of Oslo]. Duo Research Archive. https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/63353

- Hancock, V. (2019) Clinicians’ Attitudes Towards Sex Offender Treatment. [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9077&context=dissertations

- Hanson, K. (2018). Evaluating stigmatizing attitudes among clinicians toward people with ABDL and pedophilic interests [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University]. Cornerstone. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/807/

- Harper, C. A., & Bartels, R. M. (2017). The influence of implicit theories and offender characteristics on judgements of sexual offenders: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 23(2), 139–150. 10.1080/13552600.2016.1250963 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harper, C. A., Bartels, R. M., & Hogue, T. E. (2018). Reducing stigma and punitive attitudes toward pedophiles through narrative humanization. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 30(5), 533–555. 10.1177/1079063216681561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper, C. A. (2016). Examining the link between media representations and attitudes towards sexual offenders using a dual-process framework [Doctoral dissertation, University of Lincoln]. Lincoln Repository. http://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/id/eprint/24742/

- Harper, C. A., Lievesley, R., Carpenter, T., Blagden, N., Hocken, K. (2019). Using personal narratives to humanize people with pedophilic sexual interests. Advance Online Publication. 10.31234/osf.io/9c3s2 [DOI]

- Harris, A. J., & Socia, K. M. (2016). What’s in a name? Evaluating the effects of the “sex offender” What’s in a name? Evaluating the effects of the “sex offender” label on public opinions and beliefs. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 28(7), 660–678. 10.1177/1079063214564391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildembrand, S. (2019). The effects of the social imposition of stigma and self-stigma on convicted sex offenders: A phenomenological study (Publication No. 13899558). [Doctoral dissertation, Fielding Graduate University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. [Google Scholar]

- Houtepen, J. A., Sijtsema, J. J., & Bogaerts, S. (2016). Being sexually attracted to minors: Sexual development, coping with forbidden feelings, and relieving sexual arousal in self-identified pedophiles. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 42(1), 48–69. 10.1080/0092623X.2015.1061077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhoff, R. (2015). Punitive attitudes against pedophiles or persons with sexual interest in children: Does the label matter? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(1), 35–44. 10.1007/s10508-014-0439-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhoff, R., & Jahnke, S. (2018). Determinants of punitive attitudes toward people with pedophilia: Dissecting effects of the label and intentionality ascriptions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(2), 353–361. 10.1007/s10508-017-1048-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke, S. (2018a). Emotions and cognitions associated with the stigma of non-offending pedophilia: A vignette experiment. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(2), 363–373. 10.1007/s10508-017-1073-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke, S. (2018b). The stigma of pedophilia: Clinical and forensic implications. European Psychologist, 23(2), 144–153. 10.1027/1016-9040/a000325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke, S., & Hoyer, J. (2013). Stigmatization of people with pedophilia: A blind spot in stigma research. International Journal of Sexual Health, 25(3), 169–184. 10.1080/19317611.2013.795921 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke, S., Imhoff, R., & Hoyer, J. (2015). Stigmatization of people with pedophilia: Two comparative surveys. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(1), 21–34. 10.1007/s10508-014-0312-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke, S., Philipp, K., & Hoyer, J. (2015). Stigmatizing attitudes towards people with pedophilia and their malleability among psychotherapists in training. Child Abuse & Neglect, 40, 93–102. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke, S., Schmidt, A. F., Geradt, M., & Hoyer, J. (2015). Stigma-related stress and its correlates among men with pedophilic sexual interests. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(8), 2173–2187. 10.1007/s10508-015-0503-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, L. L., & Roberts, J. J. (2017). The complexity of public attitudes toward sex crimes. Victims & Offenders, 12(1), 71–89. 10.1080/15564886.2015.1005266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleban, H., & Jeglic, E. (2012). Dispelling the myths: Can psychoeducation change public attitudes towards sex offenders? Journal of Sexual Aggression, 18(2), 179–193. 10.1080/13552600.2011.552795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J. L. (2015). Vilifying the pedophiles and perverts: A nationwide test of the Community Attitudes Toward Sex Offenders (CATSO) scale. Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society, 16(3), 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, J. S., & Grady, M. D. (2019). Preventing sexual abuse: Perspectives of minor-attracted persons about seeking help. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 31(8), 991–1013. 10.1177/1079063218797713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, J. S., Grady, M. D. (2019). “I Could Never Work With Those People…”: Secondary prevention of child sexual abuse via a brief training for therapists about pedophilia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(20), 4281–4302. 10.1177/0886260519869238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, J. S., Willis, G. M., & Vicencio, C. P. (2017). Obstacles to help-seeking for sexual offenders: Implications for prevention of sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(2), 99–120. 10.1080/10538712.2016.1276116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievesley, R., Harper, C. A., & Elliott, H. (2020). The internalization of social stigma among minor-attracted persons: Implications for treatment. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(4), 1291–1304. 10.1007/s10508-019-01569-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, B. G., Cullen, F. T., Struening, E., Shrout, P.E., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (1989). A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review, 400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, G., & Willis, G. (2020). Sex offender” versus “person”: The influence of labels on willingness to volunteer with people who have sexually abused. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 32(5), 591–523. 10.1177/1079063219841904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H., & Loke, A. Y. (2020). A scoping review of an HIV/AIDS-related stigma-reduction intervention for professionals and students from health-related disciplines. International Journal of Sexual Health, 32(2), 94–129. 10.1080/19317611.2020.1754317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malinen, S., Willis, G. M., & Johnston, L. (2014). Might informative media reporting of sexual offending influence community members’ attitudes towards sex offenders? Psychology, Crime & Law, 20(6), 535–552. 10.1080/1068316X.2013.793770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCartan, K. (2010). Media constructions of, and reactions to, paedophilia in society. In Harrison, K. (Ed.), Managing high-risk sex offenders in the community: Risk management, treatment and social responsibility (pp. 249–268). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McCartan, K. F. (2011). Professional responses to contemporary discourses and definitions of pedophilia. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 13(4), 322–335. 10.1350/ijps.2011.13.4.240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes, D. R. (2018). Social Work Perceptions of Pedophilies: Opening the Dialogue [Master’s thesis, California State University]. CSUSB Scholarworks. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/680

- Moss, S. L. (2019). Understanding the treatment barriers for minor-attracted persons living in the community [Master’s thesis, Saint Mary’s University]. Patrick Power Library. http://www.t.library2.smu.ca/handle/01/29008#.XsUI7mgzbIU

- Muir, S. A. (2018). More than “potential offenders”: Understanding adults who are sexually attracted to children who have not offended [Doctoral dissertation, Massey University]. MRO. http://hdl.handle.net/10179/15091

- Parr, J., & Pearson, D. (2019). Non-offending minor-attracted persons: Professional practitioners’ views on the barriers to seeking and receiving their help. Journal of child sexual abuse, 28(8), 945–967. 10.1080/10538712.2019.1663970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piche, L., Mathesius, J., Lussier, P., & Schweighofer, A. (2016). Preventative services for sexual offenders, Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 30, 63–81. 10.1177/1079063216630749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]