Abstract

Background and Aims

Anti-hypertensive agents are one of the most frequently used drugs worldwide. However, no blood pressure–lowering strategy is superior to placebo with respect to survival in diabetic hypertensive patients. Previous findings show that Wnt co-receptors LDL receptor–related proteins 5 and 6 (LRP5/6) can directly bind to several G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). Because angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) is the most important GPCR in regulating hypertension, this study examines the possible mechanistic association between LRP5/6 and their binding protein Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) and activation of the AT1R and further hypothesizes that the LRP5/6-GPCR interaction may affect hypertension and potentiate cardiac impairment in the setting of diabetes.

Methods

The roles of serum DKK1 and DKK1-LRP5/6 signalling in diabetic injuries were investigated in human and diabetic mice.

Results

Blood pressure up-regulation positively correlated with serum DKK1 elevations in humans. Notably, LRP5/6 physically and functionally interacted with AT1R. The loss of membrane LRP5/6 caused by injection of a recombinant DKK1 protein or conditional LRP5/6 deletions resulted in AT1R activation and hypertension, as well as β-arrestin1 activation and cardiac impairment, possibly because of multiple GPCR alterations. Importantly, unlike commonly used anti-hypertensive agents, administration of the anti-DKK1 neutralizing antibody effectively prevented diabetic cardiac impairment in mice.

Conclusions

These findings establish a novel DKK1-LRP5/6-GPCR pathway in inducing diabetic injuries and may resolve the long-standing conundrum as to why elevated blood DKK1 has deleterious effects. Thus, monitoring and therapeutic elimination of blood DKK1 may be a promising strategy to attenuate diabetic injuries.

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome, Diabetes, Hypertension, DKK1, LRP5/6, GPCR, AngII/AT1R, β-arrestin1

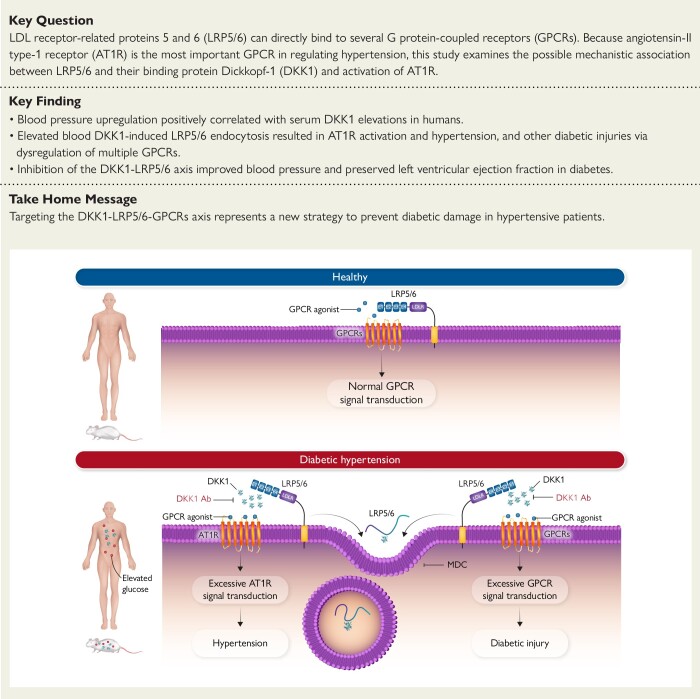

Structured Graphical Abstract

Structured Graphical Abstract.

Role of DKK1 inducing the development of hypertension and organ injury in diabetes. Under normal conditions, LRP5/6 bind to and fine-tune GPCRs to maintain normal GPCR signal transduction and organ homeostasis. Under diseased conditions such as type 2 diabetes, elevated circulating DKK1 induces membrane LRP5/6 endocytosis, which leads to deregulations of GPCRs. For example, deregulation of AT1R activation leads to hypertension, while deregulations of other LRP5/6-interacting GPCRs lead to organ injury, and these can be prevented by an anti-DKK1 neutralizing antibody or MDC that prevents DKK1-induced LRP5/6 endocytosis. AT1R, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; DKK1, Dickkopf-1; GPCR, G protein–coupled receptor; LRP5/6, LDL receptor–related proteins 5 and 6; LDLR, LDL receptor; MDC, monodansylcadaverine.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Dickkopf-1: an emerging danger signal in hypertension and cardiovascular disease’, by P.P. Toth, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad797.

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is commonly defined by the coexistence of high blood glucose, hypertension, and obesity and has become one of the most common and serious disorders worldwide due to increasing mortality and morbidity rates.1,2 Fatal cardiovascular complications constitute the most common outcomes of these health conditions, of which diabetic hypertension is thought to be the major risk factor.3 Unfortunately, high blood pressure is common in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes (much more so than in those without diabetes), with hypertension occurring in over two-thirds of patients with type 2 diabetes.4 Despite significant advances made in understanding hypertension pathogenesis and developing improved treatments, there is an ongoing debate on the appropriate pharmacologic treatments, particularly in high-risk groups such as patients with diabetes. Therefore, numerous guidelines specifically address hypertension in diabetes, including the most recent guidelines from the Eighth Joint National Committee.5 However, the findings of a recent network meta-analysis of randomized trials conducted around the world indicated that no current blood pressure–lowering strategy prolonged survival in adults with diabetes, including angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), and in particular did not support the use of β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, renin inhibitors, or diuretics in this clinical setting.6 Additionally, among patients with type 2 diabetes, blood pressure lowering was shown to be associated with improved mortality and other clinical outcomes with lower relative risk but only observed among those with baseline blood pressure of 140 mmHg and greater.7,8 Thus, the ineffectiveness of lowering blood pressure in improving mortality for people with lower blood pressure appears to reach a consensus. Hence, we hypothesize that the occurrence of hypertension in diabetes may only be a sign that indicates an unhealthy status, and therefore, other than the current anti-hypertensive drugs, identifying and targeting potentially novel factors and pathways underlying hypertension in diabetic patients is urgently needed.

The Wnt co-receptors LDL receptor–related proteins 5 and 6 (LRP5/6) are indispensable for development.9–11 Interestingly, we recently revealed a Wnt/β-catenin–independent role for LRP5/6 in inhibiting tumour metastasis via direct binding to several G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) such as Frizzled and CXCR4.12,13 We further found that knocking down LRP5/6 expression with siRNA in HepG2 cells affected multiple GPCR-related pathways.14 Thus, we hypothesized that LRP5/6 might function as general regulators of multiple GPCRs, whereby LRP5/6 deletions might induce the dysregulation of LRP5/6-interacting GPCRs and affect the corresponding GPCR-related pathways. In this regard, because angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) is the most important GPCR in regulating hypertension, we examined the role of LRP5/6 in regulating blood pressure and sought to further explore a possible interaction between LRP5/6 and AT1R. Notably, we recently found that the circulating LRP5/6-binding protein Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) promoted ischaemic cardiac impairment (probably by inducing LRP5/6 endocytosis during adulthood). From a translational perspective, it is much easier to remove circulating factors; hence, we explored whether DKK1 might play a role in LRP5/6-regulated blood pressure.

In this study, we sought to reveal whether a new DKK1-LRP5/6-GPCRs (including AT1R) pathway was involved in diabetic injury. We further compared the effects of an anti-DKK1 neutralizing antibody in preventing diabetic cardiac impairment to other commonly used anti-hypertension agents.

Methods

Detailed methods are provided in Supplementary data online, Materials.

Animal models

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Fujian, China) and comply with the ARRIVE guidelines and were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. All wild-type mice and inducible global LRP5/6-knockout mice used were C57BL/6J strain (stock #000664), male, and 8–10-week-old. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Two-dimensional echocardiography

Two-dimensional echocardiography was performed using VisualSonics Vevo 2100 Imaging System by a blinded investigator. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Blood pressure measurement

Mouse systolic blood pressures (SBPs) were measured by non-invasive tail-cuff method using CODA High Throughput System (Kent Scientific, USA) by a blinded investigator. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Cell culture and reporter gene assays

For details of cell culture and reporter gene assays, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Participants data collection

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethics Committee of Shanghai East Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, approved this study protocol (Number: ECSEH2017-010). All enrolled subjects gave written informed consent. This was a community population-based study of non-institutionalized older individuals from Pudong New District (Shanghai, China) between April and August 2017. All subjects were aged 60 years or older and had permanent residency in the community. Overnight fasted blood samples were obtained, and standardized questionnaires were filled out based on demographic characteristics, personal and medical history, and lifestyle risk factors. Subsequently, recording of anthropometric measurements was collected according to standard protocol. For the cohort of younger participants from Fujian (≤65 years old), all subjects underwent routine physical examinations and overnight fasted blood samples were collected at Fujian Provincial Hospital (Fujian, China) between July and November 2019. All participants were of Asian ethnicity. The study received ethical approval from the Local Committee of Fujian Provincial Hospital, Health Management Department. All subjects provided written informed consent forms for taking part in the study. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay assays

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assays were performed according to standard procedure. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Glomerular filtration rate measurement

Estimated glomerular filtration rate was performed via high-throughput assay using FITC-inulin. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis

Immunoprecipitation (IP) and western blot (WB) analysis were performed according to standard procedures. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Histological and immunofluorescence staining

Histological and immunofluorescence staining was performed according to standard procedure. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Vascular contractility

Measurements of vascular contractility were performed via wire myography according to standard procedure. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Quantitative proteomics analysis

Combined non-standard quantitative technology and mass spectrometry–based proteomics technology was performed. For details, see Supplementary data online, Materials.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using SPSS 17.0 software. Shapiro–Wilk tests for normality were performed, and for outcomes with normal distribution, comparisons of means were performed using unpaired Student’s t-test (for two groups) or one-way ANOVA (for three or more groups) followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc analysis. For outcomes with non-normal distribution, Mann–Whitney U-test (for two groups) or Kruskal–Wallis (for three or more groups) followed by post-hoc Dunn’s test were performed. Two-tailed P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Multiple regression analysis was performed to examine the association of elevated serum DKK1 in humans with the increase in blood pressure, after adjusting for all potential confounders. R-squared values for the model were estimated based on the line of best fit using least squares linear regression.

Results

Potential involvement of Dickkopf-1 in diabetes

A protein interaction network generated from the GeneCards data set comprising of 13 747 diabetes-related genes showed that DKK1 occupied a relatively central position among diabetes-related genes (see Supplementary data online, Figure S1A). Furthermore, DKK1 was also observed in two additional data sets from Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man Database and Rat Genome Database that only displayed diabetes-related genes, respectively (see Supplementary data online, Figure S1B). Notably, the top-listed genes that encode secreted proteins, such as insulin, interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and insulin-like growth factor 1, have all been reported to participate in different developmental stages of diabetes (see Supplementary data online, Figure S1C), which validated the accuracy of the bioinformatics data set. In addition, a Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) data set showing up-regulated or down-regulated genes in the kidneys of mice with type 2 diabetes was used to analyse the expression patterns of the top diabetes-related genes from the human GeneCards data set. Interestingly, DKK1 was identified as the top-ranked gene among those showing stable up-regulation (see Supplementary data online, Figure S1D). These bioinformatics data imply a potential involvement of DKK1 in diabetes.

A positive relationship between elevated serum Dickkopf-1 levels and high blood pressure in humans

To investigate how DKK1 is involved in diabetes, we first analysed serum samples from 2073 eligible elderly subjects (≥60 years old). The participants were separated into a hypertensive group with a history of hypertension and a normal group without a history of hypertension (Table 1). Interestingly, the blood levels of DKK1, fasting glucose, and haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) were significantly higher in the hypertensive group (Figure 1A). Furthermore, participants with a history of diabetes who were not currently taking anti-hyperglycaemic drugs also had significantly higher DKK1 levels and blood pressure than normal subjects (Figure 1B). These results suggest a possible link between hyperglycaemia and high blood DKK1 levels and hypertension.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in the cohort of elderly Shanghai residents in China grouped according to whether they had a prior history of hypertension (hypertensive) or no prior history of hypertension (normal)

| Group (Shanghai) | Normal n = 869 |

Hypertensive n = 1204 |

Total n = 2073 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.88 ± 5.76 | 70.69 ± 6.07 | 70.35 ± 5.95 | .002 |

| Sex (male | female) | 360 | 509 | 518 | 686 | 878 | 1195 | .468 |

| Height (cm) | 160.1 ± 8.72 | 160.2 ± 8.35 | 160.2 ± 8.51 | .901 |

| Weight (kg) | 61.82 ± 11.02 | 66.06 ± 12.62 | 64.28 ± 12.15 | <.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 134.73 ± 18.48 | 147.79 ± 20.77 | 142.31 ± 20.86 | <.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 79.16 ± 9.92 | 81.96 ± 10.72 | 80.79 ± 10.48 | <.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.25 ± 1.05 | 6.44 ± 1.09 | 6.36 ± 1.07 | <.001 |

| Fasted glucose (mmol/L) | 5.69 ± 1.64 | 6.04 ± 1.62 | 5.89 ± 1.64 | <.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.17 ± 0.97 | 5.01 ± 1.00 | 5.08 ± 0.99 | <.001 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.55 ± 0.81 | 1.75 ± 1.07 | 1.67 ± 0.98 | <.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.52 ± 0.42 | 1.40 ± 0.38 | 1.45 ± 0.41 | <.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.44 ± 0.87 | 3.32 ± 0.92 | 3.37 ± 0.90 | .003 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 2.00 ± 4.36 | 2.33 ± 5.45 | 2.19 ± 5.02 | .125 |

| α-Fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 3.13 ± 1.74 | 3.10 ± 1.73 | 3.11 ± 1.74 | .656 |

| Uric acid (µmol/L) | 314.7 ± 81.99 | 336.8 ± 85.83 | 327.5 ± 84.92 | <.001 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 74.10 ± 16.97 | 76.44 ± 17.96 | 75.46 ± 17.59 | .003 |

| Urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 5.50 ± 1.34 | 5.59 ± 1.51 | 5.55 ± 1.44 | .181 |

| Homocysteine (µmol/L) | 15.51 ± 7.03 | 16.59 ± 7.79 | 16.14 ± 7.50 | .001 |

| AST (U/L) | 21.80 ± 8.68 | 21.52 ± 7.37 | 21.64 ± 7.94 | .447 |

| ALT (U/L) | 17.37 ± 11.52 | 19.18 ± 13.95 | 18.42 ± 13.01 | .001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 141.2 ± 45.84 | 141.26 ± 13.09 | 141.2 ± 31.31 | .961 |

Values indicate means ± standard deviations. P values comparing significance between normal vs. hypertensive residents, Student’s t-test.

BP, blood pressure; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

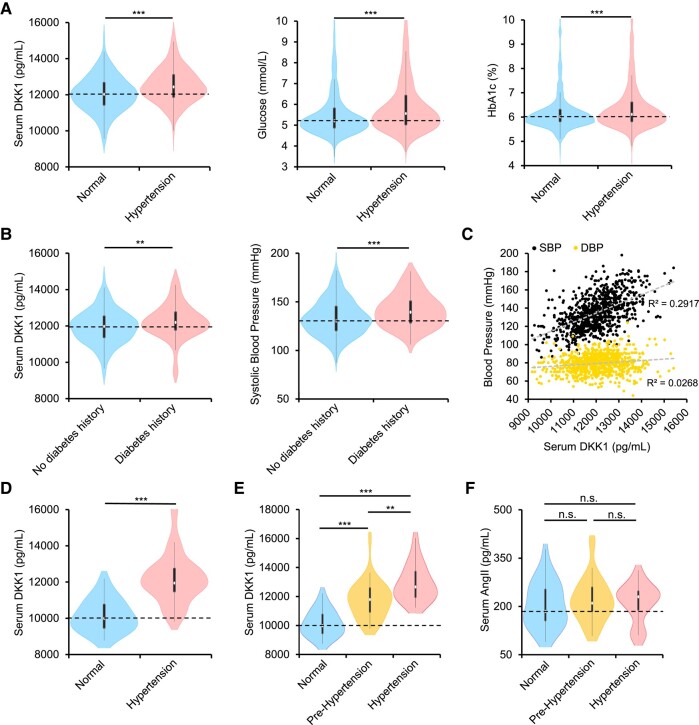

Figure 1.

A positive relationship between elevated serum Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) levels and high blood pressure in humans. (A–C) Shanghai cohort. For comparisons of serum DKK1 with blood pressure, multiple regression analysis using least square means was used after adjustment for the following confounders: age, haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), HDL, LDL, and serum uric acid for the predicted serum DKK1 level from regression model fit. Violin plots (A) showing serum DKK1 levels (left), blood glucose (middle), and HbA1C (right) in elderly participants without hypertensive history (normal, n = 869) vs. hypertensive patients with a history of hypertension (hypertensive, n = 1204). Student’s t-test. ***P < .001. White dot, median; black bars, first and third quartiles; black lines, 1.5× interquartile range. Violin plots (B) showing serum DKK1 levels (left) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) (right) in normal participants without hypertensive or diabetic history or clearly diagnosed hypertension or diabetes (normal, n = 620) vs. participants with diabetes but not taking anti-hyperglycaemic drugs (diabetes, n = 97). Student’s t-test. **P < .01, ***P < .001. Scatter plot (C) showing the moderate positive correlation between increased serum DKK1 with increased SBP but not diastolic blood pressure (DBP) among normal elderly participants without hypertensive history (n = 869). R-squared values for the model were estimated based on the line of best fit using least squares linear regression. (D–F) Fujian cohort. For comparisons of serum DKK1 with blood pressure in Fujian cohort, multiple regression analysis using least square means was used after adjustment for the following confounders: age, blood glucose, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides for the predicted serum DKK1 level from regression model fit. Violin plots (D) showing serum DKK1 levels in younger participants with normal blood pressure (normal, n = 27) vs. those with elevated blood pressure (hypertension, n = 54). Mann–Whitney U-test. ***P < .001. White dot, median; black bars, first and third quartiles; black lines, 1.5× interquartile range. Violin plots (E) showing serum DKK1 levels in younger participants separated according to their blood pressures, ranging from normotensive (DBP < 80 mmHg and SBP < 120 mmHg, n = 27), pre-hypertension (either DBP between 80 and 89 mmHg or SBP 120–139 mmHg, n = 34), or hypertension (either DBP ≥ 90 mmHg or SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, n = 20). Kruskal–Wallis test. **P < .01, ***P < .001. Violin plots (F) showing serum AngII levels in younger participants separated according to their blood pressures, ranging from normotensive (n = 27), pre-hypertension (n = 34), or hypertension (n = 20). Kruskal–Wallis test. n.s., no significance

Notably, a broad distribution of blood pressures was also observed in participants without a history of hypertension, who did not take anti-hypertensive drugs and should represent a realistic level of blood pressure. Interestingly, a detailed analysis of these participants without diagnosed hypertension showed a moderate positive relationship between elevated blood DKK1 levels and up-regulated systolic pressures but not diastolic pressures (Figure 1C). Because of elevated arterial stiffness, a natural ageing phenomenon among the elderly that diminishes elastic recoil and results in higher systolic but lower diastolic blood pressures,15–17 the ability of DKK1 in up-regulating diastolic blood pressure may be diluted in the elderly.

Because elderly people have a weakened ability to regulate the blood pressure, we further recruited a smaller cohort of younger individuals (≤65 years old) (Table 2). Blood DKK1 levels were also significantly elevated in participants with elevated blood pressure in the younger population (Figure 1D). Blood pressure could be further divided into normotension, pre-hypertension, and hypertension according to the expression levels of blood DKK1 (Figure 1E), indicating that DKK1 has increased sensitivity in regulating the blood pressure in these younger people. However, no correlation was observed between blood angiotensin II (AngII) levels and blood pressure up-regulation in these participants (Figure 1F). These results indicate that blood DKK1 levels may be a sensitive determinant for blood pressure up-regulation. A larger cohort analysis may elucidate whether DKK1 is an ideal serum marker for monitoring blood pressure changes.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in the cohort of younger Fujian participants in China grouped according to their measured blood pressure, where SBP < 120 mmHg and DBP < 80 mmHg (normotensive) and SBP > 120 mmHg or DBP > 80 mmHg (hypertensive)

| Group (Fujian) | Normotensive n = 27 |

Hypertensive n = 54 |

Total n = 81 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.59 ± 8.19 | 50.11 ± 8.99 | 46.94 ± 9.79 | <.001 |

| Sex (male | female) | 4 | 23 | 32 | 22 | 36 | 45 | .002 |

| Height (cm) | 161.06 ± 6.09 | 164.78 ± 9.96 | 163.56 ± 9.01 | .114 |

| Weight (kg) | 56.52 ± 9.90 | 66.35 ± 11.60 | 63.11 ± 11.95 | <.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 105.77 ± 6.85 | 133.85 ± 11.06 | 124.61 ± 16.52 | <.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 65.46 ± 5.85 | 81.70 ± 9.18 | 76.35 ± 11.23 | <.001 |

| Fasted glucose (mmol/L) | 4.80 ± 0.45 | 5.38 ± 1.68 | 5.19 ± 1.43 | .038 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.68 ± 1.06 | 4.90 ± 1.02 | 4.83 ± 1.03 | .136 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.10 ± 0.62 | 1.68 ± 1.06 | 1.49 ± 0.97 | .008 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.48 ± 0.30 | 1.31 ± 0.35 | 1.36 ± 0.34 | .079 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.08 ± 1.00 | 3.36 ± 0.99 | 3.27 ± 1.00 | .052 |

| Uric acid (µmol/L) | 296.04 ± 69.40 | 376.44 ± 90.47 | 350.34 ± 91.92 | <.001 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 64.84 ± 11.59 | 68.37 ± 14.84 | 67.22 ± 13.89 | .367 |

| Urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 4.62 ± 1.21 | 4.97 ± 1.12 | 4.86 ± 1.15 | .172 |

Values indicate means ± standard deviations. P values comparing significance between normal vs. hypertensive residents, Student’s t-test.

BP, blood pressure; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Dickkopf-1 induced blood pressure up-regulation in diabetic mice

To establish causal relationships between DKK1 and diabetic hypertension, we investigated the roles of DKK1 in mice with type 2 diabetes fed a high-fat/high-fructose diet (HFFD) and mice with type 1 diabetes injected with streptozocin (STZ). Serum DKK1 levels were significantly up-regulated in both mouse models, which was prevented by insulin administration that attenuated blood glucose levels (Figure 2A). In contrast, intraperitoneal injections of glucose (continuous for 24 h) in wild-type mice induced blood DKK1 up-regulation, although continuous injections resulted in greatly diluted serum protein levels, including those of DKK1 (Figure 2B). These results suggest that high blood glucose levels can induce blood DKK1 up-regulation. Furthermore, similar to the effect observed in humans, the increases in blood pressures in both HFFD-fed and STZ-treated mice correlated closely with elevated blood DKK1 levels (Figure 2C), demonstrating the sensitive ability of blood DKK1 to up-regulate blood pressure. Importantly, blood pressure up-regulation in these diabetic mice was prevented by treatment with a neutralizing anti-DKK1 antibody—BHQ880, Novartis Therapeutics (Figure 2D).

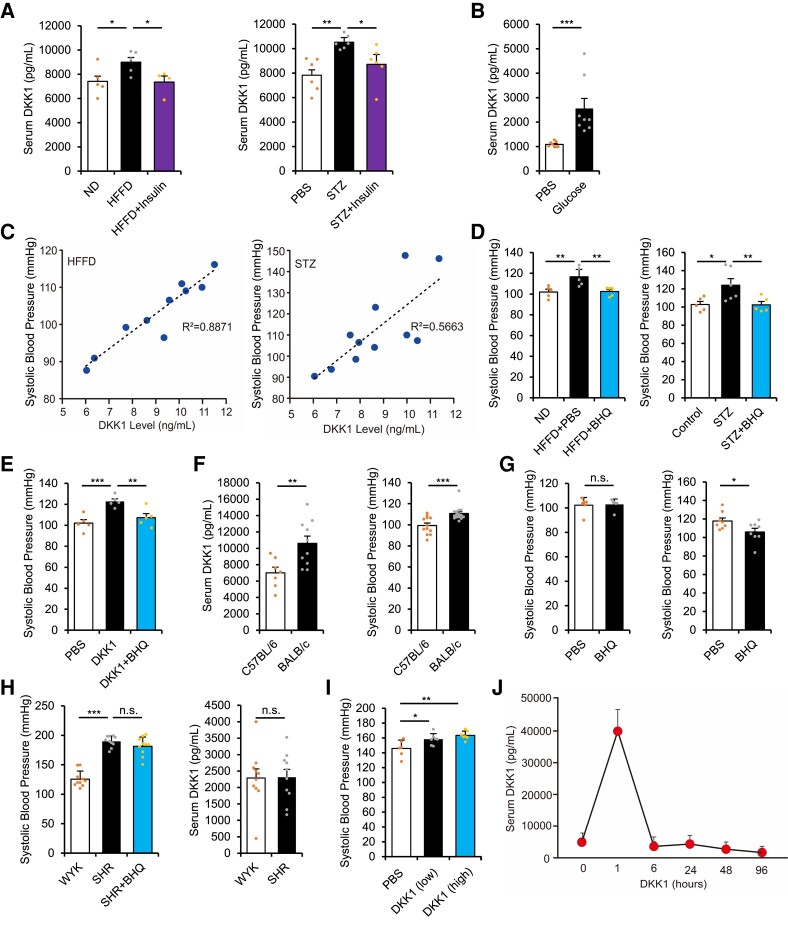

Figure 2.

Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) induces blood pressure up-regulation. (A) Serum DKK1 level (left) at 10 weeks in high-fat/high-fructose diet (HFFD)-fed mice with or without treatment with insulin, compared with those on normal diet. n = 4 or more, *P < .05 vs. HFFD alone. Serum DKK1 level (right) at 6 weeks in streptozocin (STZ)-injected mice with or without treatment with insulin, compared with phosphate buffered saline (PBS)-injected mice. n = 6. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, **P < .01, *P < .05 vs. STZ alone. (B) Serum DKK1 level in 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice injected with glucose (2 g/kg/h) or PBS for 24 h. n = 8. Mann–Whitney U-test. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001. (C) Regression analysis of mouse systolic blood pressure vs. serum DKK1 level in diabetic HFFD model, n = 10 (left), and STZ model, n = 11 (right). (D) Systolic blood pressure in HFFD-fed mice with or without treatment with BHQ880 at 10 weeks post-HFFD model (left), n = 5, **P < .01 vs. HFFD alone or in STZ-injected mice at 6 weeks (right), n = 5 or more. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01 vs. STZ alone. (E) Systolic blood pressure following DKK1 injection (1 mg/kg/day) for 4 consecutive days, with or without treatment with BHQ880. n = 5. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs. DKK1 alone. (F) Serum DKK1 level in 10-week-old C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice (left). n = 7 or more, Student’s t-test. **P < .01. Systolic blood pressure in 10-week-old C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice (right). n = 12 or more. Mann–Whitney U-test. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001. (G) Systolic blood pressure in 10-week-old C57BL/6 (left) and BALB/c (right) mice with or without treatment with BHQ880 for 2 weeks. n = 6 or more. Student’s t-test. Mean ± SEM, n.s., no significance, *P < .05. (H) Systolic blood pressure (left) and serum DKK1 level (right) in 10-week-old spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) injected with PBS or BHQ880, compared with age-matched Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. n = 10. One-way ANOVA (left) or Student’s t-test (right). Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001. n.s., no significance. (I) Systolic blood pressure in 6-week-old SHR injected with DKK1 (low, 0.5 mg/kg/day) or (high, 1 mg/kg/day) for 3 consecutive days. n = 6 or more. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, *P < .05, **P < .01. (J) Serum DKK1 level changes following a single injection of DKK1 (1 mg/kg) in 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice. n = 3

Furthermore, we directly injected recombinant DKK1 protein into wild-type mice, which resulted in a significant increase in blood pressure that could be prevented by BHQ880 administration (Figure 2E). Interestingly, BALB/c mice had higher serum DKK1 levels and higher basal blood pressures than C57BL/6 mice (Figure 2F). Importantly, treatment with BHQ880 decreased blood pressure in BALB/c mice but not in C57BL/6 mice (Figure 2G). BHQ880 also had no effect on blood pressure regulation in spontaneous hypertensive rats (SHRs) that had spontaneous hypertension without elevated blood DKK1 levels (Figure 2H). However, DKK1 injection in SHRs rapidly induced blood pressure up-regulation (Figure 2I). Notably, exogenous DKK1 has a short half-life in the blood; hence, even after injecting recombinant DKK1 protein into wild-type mice, the serum DKK1 levels were not maintained at a high level for very long (Figure 2J). Thus, even a slight up-regulation of basal blood DKK1 levels during diabetes should be adequate for inducing blood pressure up-regulation. These results demonstrate the ability of DKK1 to up-regulate the blood pressure. It would be interesting to reveal the underlying mechanism regarding how DKK1 induces blood pressure up-regulation, which we will explore in detail below.

Potential involvement of Dickkopf-1-induced LDL receptor–related proteins 5 and 6 endocytosis in up-regulating blood pressure

A protein interaction network based on the GeneCards data set showed that LRP5/6 were the closest interacting proteins with DKK1 in patients with diabetes (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2A). Indeed, LRP5/6 and Kremen1/2 are generally known as DKK1-binding proteins, where DKK1 inhibits the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway by binding to both LRP5/6 and Kremen1/2, thereby causing LRP5/6 internalization.18,19 The initial activation and gradual inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signalling determines embryonic development, and, therefore, both LRP5/6 (key Wnt activators) and DKK1 (a strong Wnt antagonist) are indispensable during development.18–21 However, DKK1 expression becomes silent in most adult organs22–24; hence, the roles of DKK1 in regulating LRP5/6-related functions during adulthood remain unclear.

A GEO data set comprising kidney gene expression levels in mice with type 2 diabetes was further used to analyse the corresponding expression patterns of the top diabetes-related genes from the human GeneCards data set, which revealed LRP6 down-regulation and highly stable DKK1 up-regulation (see Supplementary data online, Figure S1D). Surprisingly, global deletions of LRP5/6 significantly induced blood pressure up-regulation (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2B). These results suggest that the down-regulation of both LRP5 and LRP6, but the up-regulation of blood DKK1, can induce blood pressure up-regulation. We further found that DKK1 injection induced LRP5/6 endocytosis in organs such as the heart, which was prevented by monodansylcadaverine (MDC), a small molecule that prevents DKK1-induced LRP5/6 endocytosis,25 as well as BHQ880 (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2C–E). Importantly, MDC administration prevented blood pressure up-regulation in DKK1-injected, HFFD-fed, and STZ-treated mice but not in SHRs without elevated blood DKK1 (Figure 3A–C). Furthermore, membrane LRP5/6 down-regulation was observed in the hearts of HFFD-fed mice, which was prevented by BHQ880 administration (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2F), suggesting that elevated blood DKK1 levels lead to LRP6 endocytosis during diabetic hypertension. Thus, membrane LRP5/6 down-regulation constitutes the underlying mechanism whereby DKK1 up-regulates blood pressure.

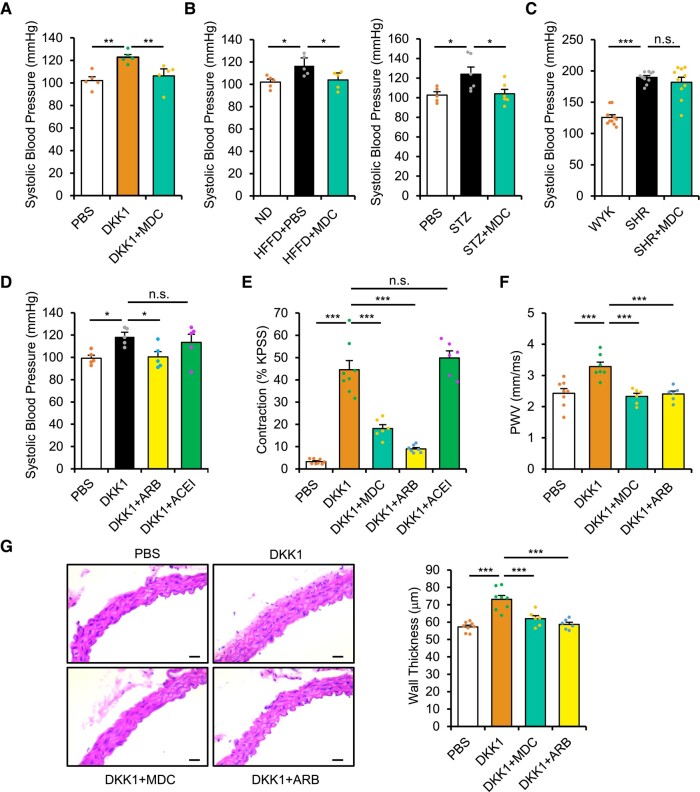

Figure 3.

Involvement of DKK1-induced LRP5/6 endocytosis in up-regulating blood pressure via activating angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R). (A) Systolic blood pressure following Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) injection (1 mg/kg/day) with or without monodansylcadaverine (MDC) treatment for 4 days. n = 5. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, **P < .01 vs. DKK1 alone. (B) Systolic blood pressure at 10 weeks post-HFFD model and treatment with or without MDC (left). n = 5, *P < .05 vs. HFFD alone or at 6 weeks post-streptozocin (STZ) model (right). n = 5 or more. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, *P < .05 vs. STZ alone. (C) Systolic blood pressure in 10-week-old spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) injected with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or MDC, compared with age-matched Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. n = 10. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001, n.s., no significance. (D) Systolic blood pressure following DKK1 injection (1 mg/kg/day) for 2 days, with or without angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) (losartan) or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) (captopril). n = 5. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, *P < .05 vs. DKK1 alone. (E) Vascular contractility was measured ex vivo via wire myography following incubation of the descending thoracic aorta with PBS or DKK1 (1 µg/mL), with or without MDC, ARB (losartan), or ACEI (captopril) for 1 h. Maximum contractility was first induced with high potassium physiological saline solution (KPSS), and results were calculated based on the percentage of maximum contraction. n = 6 or more. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001, n.s., no significance. (F) Aortic pulse-wave velocity (PWV) based on pulse transit time was measured via echocardiography assessment at 2 weeks following injections with PBS or DKK1 (1 mg/kg/day), with or without MDC or ARB (losartan). n = 6 or more. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001. (G) Representative H&E staining of descending thoracic aortas (left) and wall thickness (right) at 2 weeks following injections with PBS or DKK1 (1 mg/kg/day), with or without MDC or ARB (losartan). n = 6 or more. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001. Scale bar, 50 µm

A new Dickkopf-1-LDL receptor–related proteins 5 and 6-angiotensin II type 1 receptor pathway in up-regulating blood pressure

Angiotensin II/AT1R signalling is known to play the most important role in up-regulating blood pressure.26 Due to the ability of LRP5/6 to regulate GPCRs,12–14 we investigated whether the DKK1-LRP5/6 axis up-regulated blood pressure by affecting the prototypical GPCR, AT1R. Notably, the rapid blood pressure up-regulation induced by DKK1 administration was completely prevented by ARB, losartan (an AT1R antagonist) but not ACEI, and captopril (an inhibitor of AngII production) (Figure 3D). Furthermore, we directly examined vascular function ex vivo via wire myography following acute incubation of the descending thoracic aorta with DKK1. Dickkopf-1 administration rapidly increased vascular contractility, which was significantly attenuated by administration of ARB or MDC but not ACEI (Figure 3E). Thus, because the vessels were cultured ex vivo, this ensured that AngII was unavailable and hence indicates that DKK1 administration affects vessel contractility and up-regulates blood pressure via inducing LRP5/6 endocytosis and directly activating AT1R. Moreover, chronic DKK1 administration for 2 weeks significantly increased pulse-wave velocity (Figure 3F) and thickening of vascular wall (Figure 3G and Supplementary data online, Figure S2G), which were also attenuated by administration of ARB or MDC. These results indicate that DKK1 activates AT1R and up-regulates blood pressure by inducing LRP5/6 endocytosis.

Additionally, chronic AngII-induced hypertension was further enhanced by DKK1 administration but unaffected by MDC administration (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2H) even though MDC prevented blood pressure up-regulation in DKK1-injected, HFFD-fed, and STZ-treated mice (Figure 3A and B). Chronic AngII administration also significantly increased pulse-wave velocity and thickening of vascular wall, which were further enhanced by DKK1 administration (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2I). Taken together, these results on the vasculature further demonstrate that the DKK1-LRP5/6 axis-induced blood pressure up-regulation is via activating AT1R in the blood vessels.

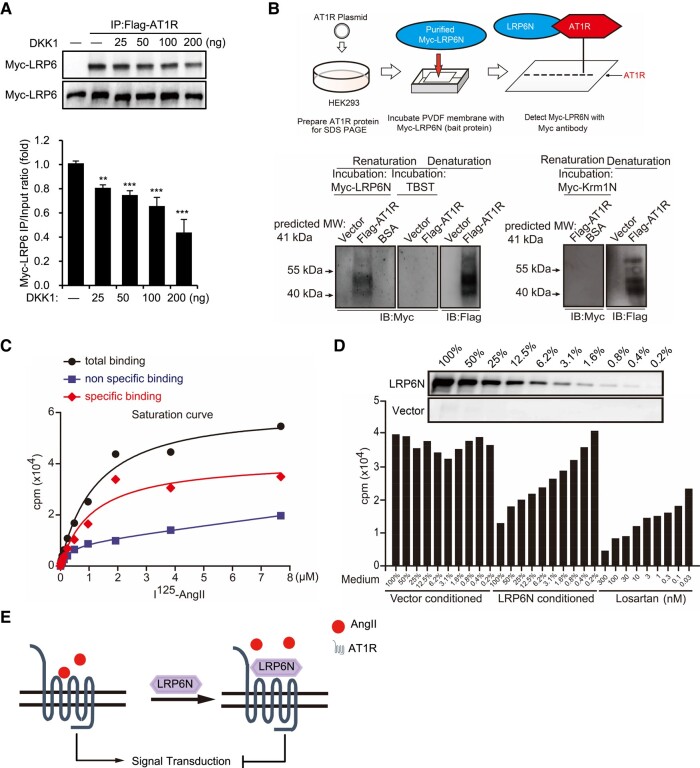

LDL receptor–related protein 6 directly bound to angiotensin II type 1 receptor via its ectodomain

Co-immunoprecipitation/WB analysis showed that Myc-tagged full-length LRP6 bound to Flag-tagged AT1R, which was attenuated by treatment with a recombinant DKK1 protein (Figure 4A). Furthermore, in addition to the LRP6ΔN mutant (which lacked the ectodomain), all LRP6 mutants bound to AT1R (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3A and B), indicating that the ectodomain of LRP6 (LRP6N) binds to AT1R. We also performed far-WB analysis,27 which showed a distinct band corresponding to the Myc-tagged LRP6N protein but not the Kremen1N protein at the site of Flag-tagged AT1R (Figure 4B), demonstrating that LRP6N but not Kremen1N directly bound to AT1R. Furthermore, I125-AngII bound to AT1R in a saturated manner in HEK293-AT1R cells that stably expressed AT1R but in a linear fashion in wild-type HEK293 cells (Figure 4C), thus verifying the specific binding of AngII to AT1R. Moreover, pre-treatment with LRP6N-conditioned medium or losartan (positive control) inhibited I125-AngII binding to AT1R in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4D), suggesting that LRP6N competitively prevented AngII binding to AT1R.

Figure 4.

LDL receptor–related protein 6 (LRP6) via its ectodomain directly binds to angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R). (A) Immunoprecipitation (IP) and western blot (WB) showing the expression of Myc-LRP6 following transfection with Flag-AT1R for 24 h followed by treatment with various concentrations of Dickkopf-1 in HEK293 cells for 1 h. n = 3. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, **P < .01, ***P < .001. (B) Schematic flow chart of Far-WB process (upper). Far-WB analysis showing direct interaction of recombinant LRP6N protein with Flag-AT1R (lower). n = 3. (C) Radioligand saturation assays showing interaction between AngII and AT1R. Each data point from increasing concentrations of I125-AngII incubated with HEK293 cells expressing AT1R (total binding) was subtracted by that from wild-type HEK293 cells (non-specific binding), with final saturation curve (specific binding). (D) Radioligand competition assays showing interaction between LRP6N and AT1R. Increasing amounts (0.2%–100%) of conditioned Myc-LRP6N supernatant and losartan pre-treatment and their effect on the binding of I125-AngII to AT1R-expressing HEK293 cells. Upper immunoblot showed the linear change of Myc-LRP6N supernatant. (E) Schematic illustration showing the effect of LRP6N in preventing AngII binding to AT1R

LDL receptor–related protein 6 ectodomain inhibited angiotensin II/angiotensin II type 1 receptor signal transduction

We then investigated the functional significance of LRP6N binding to AT1R. Except for LRP6ΔN (without the ectodomain), all LRP6 mutants inhibited the activation of AngII/AT1R-responsive c-fos and β-MHC-luciferase (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3C and D). In contrast, except for LRP6ΔC, the overexpression of all LRP6 mutants robustly activated Wnt-responsive TOPflash (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3E). Overexpression of a constitutively active β-catenin mutant (β-cateninΔN) also robustly activated TOPflash (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3E) but did not affect c-fos or β-MHC activation (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3C). AngII-induced activations of ERK1/2, c-fos, and β-MHC were enhanced by siRNA-mediated knockdown of LRP5 or LRP6 but not β-catenin (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3F and G). The enhanced activations of c-fos and β-MHC were robustly inhibited by pre-treatment with LRP6N-conditioned medium (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3H and I). These results indicate that the LRP6 ectodomain inhibited AngII/AT1R signal transduction independently of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. AngII stimulation also induced an increase in Ca2+ influx (immediately downstream in the signalling pathway), which was significantly prevented by pre-treatment with recombinant LRP6N protein and losartan but not Kremen1N protein (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3J–L). Additionally, LRP6N-conditioned medium attenuated AngII-induced activations of ERK1/2, c-fos, and β-MHC (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3M and N). Collectively, these results demonstrate that LRP6N competitively inhibited AngII/AT1R signal transduction (Figure 4E).

We further constructed LRP6N-transgenic mice (LRP6N/Tg) that globally expressed the LRP6N protein via an inducible Cre-loxP system (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3O and P). Both AngII and DKK1 rapidly induced ERK1/2 activations in wild-type mice (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3Q). Furthermore, DKK1 injection enhanced AngII-induced ERK1/2 activations and the enhanced ERK1/2 activations were prevented by MDC administration (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3Q), suggesting that DKK1 enhances AngII/AT1R signal transduction via inducing LRP5/6 endocytosis. However, AngII administration did not activate ERK1/2 in LRP6N/Tg mice (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3R), verifying the ability of LRP6N to inhibit AngII/AT1R activation in vivo. Additionally, as it is known that LRP6N can bind to DKK1, DKK1 injection also did not activate ERK1/2 or enhance AngII-induced ERK1/2 activations in LRP6N/Tg mice (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3R). Importantly, LRP6N overexpression in LRP6N/Tg mice significantly prevented chronic AngII infusion-induced blood pressure up-regulation (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3S). These findings indicate that LRP6N inhibited the functions of both AT1R and DKK1 by directly binding to them.

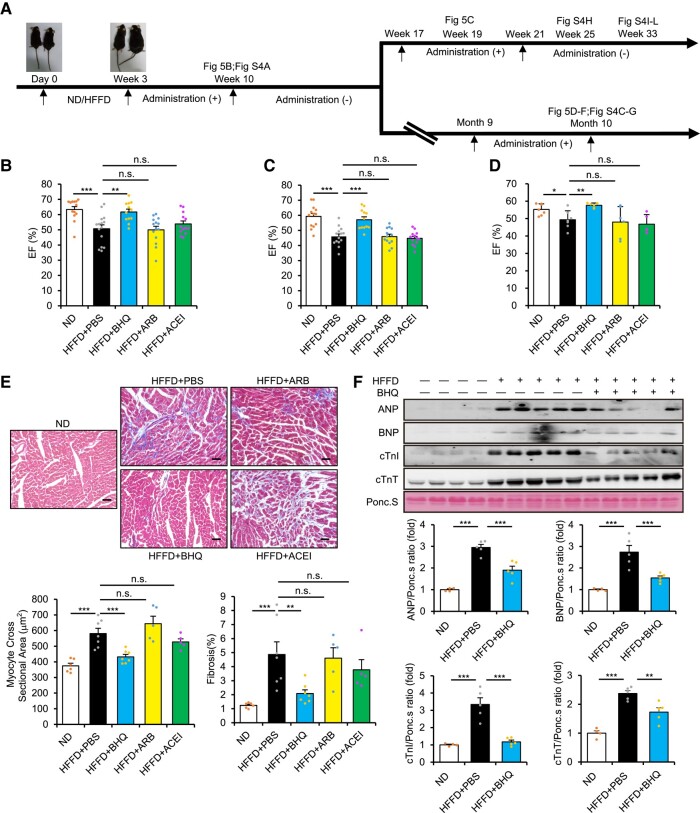

Neutralizing blood Dickkopf-1 effectively prevented diabetic injuries

Since hypertension can be effectively controlled by currently used anti-hypertensive agents, the seemingly mild extent of DKK1-induced blood pressure up-regulation may appear to have less significance with respect to the potential clinical application of anti-DKK1 antibodies. To determine the functional importance of neutralizing blood DKK1, we observed the long-term chronic effects of these agents (Figure 5A). Although ARB or ACEI prevented blood pressure up-regulation in HFFD-fed or STZ-treated diabetic mice, any halt in treatment resulted in the immediate re-up-regulation of blood pressure, but this was not the case in mice treated with BHQ880 or MDC (see Supplementary data online, Figure S4A and B). Echocardiography assessment showed systolic impairment with decreased ejection fraction (EF) following HFFD feeding for 10 weeks, which was strongly prevented by 7-week treatment with BHQ880 but not ARB or ACEI (Figure 5B). Skipping or voluntary discontinuation of anti-hypertensive medication is commonplace but may be associated with higher all-cause mortality.28 Notably, after a 7-week halt in treatment and subsequent re-administration for 2 weeks, only BHQ880 treatment stably protected cardiac function (Figure 5C). Furthermore, after a longer 6.5-month halt and subsequent re-administration for 1 month, BHQ880 was still the only treatment that showed preserved EF (Figure 5D), suggesting that neutralizing DKK1 at any stage is beneficial for prevention of HFFD-induced cardiac impairment. Cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and up-regulations of cardiac remodelling markers were also observed in these mice, which were significantly attenuated only by re-administration of BHQ880 (Figure 5E and F and Supplementary data online, Figure S4C–E). These results demonstrate that DKK1 neutralization but not AT1R inhibition can specifically prevent HFFD-induced cardiac impairment. In contrast, all three agents exhibited similar protective effects on HFFD-induced kidney injury (see Supplementary data online, Figure S4F and G).

Figure 5.

Neutralizing blood Dickkopf-1 prevents diabetic cardiac impairment. (A) Scheme of mouse high-fat/high-fructose diet (HFFD) model experiments and administrations of anti-hypertensive agents. Eight-week-old C57BL/6 mice were started on a normal diet (ND) or HFFD diet designated as Day 0. Starting at Week 3 following induction of HFFD, administration of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or anti-hypertensive agents was performed via intraperitoneal injection once every 2 days until Week 10. (Top line) In the first group, after a 7-week halt in treatment, mice were re-administered with the respective anti-hypertensive agents for 4 weeks prior to discontinuation. (Bottom line) In the second group, after a 6.5-month halt in treatment, mice were re-administrated with the respective anti-hypertensive agents for 4 weeks. (B) Ejection fraction at Week 10 in HFFD mice administrated with BHQ880, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), or PBS. n = 12 or more. Kruskal–Wallis test. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001, **P < .01, n.s., no significance. (C) Ejection fraction at Week 19 in HFFD mice administrated with BHQ880, ARB, ACEI, or PBS. n = 12 or more. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001, n.s., no significance. (D–F) Ejection fraction (D), representative Masson’s trichrome–stained sections and quantification of myocyte cross-sectional area and cardiac fibrosis (E), and representative immunoblots and quantifications (F) at Month 10 in HFFD-fed mice administrated with PBS or BHQ880, ARB, or ACEI, followed by 6.5-month halt in treatment and then re-administration with the respective anti-hypertensives for 4 weeks. n = 4 or more. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .001, **P < .01, n.s., no significance

Additionally, mice fed long-term with HFFD had impaired liver function, with significant elevations of plasma AST and ALT levels, which were also attenuated only by BHQ880 (see Supplementary data online, Figure S4H). Moreover, mice fed long-term with HFFD had impaired capacity for physical activity, which was also significantly improved only by BHQ880 (see Supplementary data online, Figure S4I–K). These results may explain the clinical findings that ARB or ACEI cannot prolong survival in patients with diabetic hypertension. Indeed, in addition to the protective functions for different organs, we also observed that mice that were treated with BHQ880 for 11 weeks prior to discontinuation had markedly prolonged median survival following long-term HFFD feeding, while in contrast, those administered with ARB or ACEI did not (see Supplementary data online, Figure S4L). Whether continued treatment of BHQ880 may result in significantly prolonged survival warrants further investigations.

We further co-administrated BHQ880 with ARB or ACEI in HFFD-fed mice (see Supplementary data online, Figure S5A). Following HFFD feeding for 10 weeks, mice exhibited cardiac impairment, which were similarly attenuated by BHQ880 administration alone or co-administrations with either ARB or ACEI for 7 weeks but not by ARB or ACEI alone (see Supplementary data online, Figure S5B–D), suggesting that DKK1 neutralization but not AT1R inhibition can protect HFFD-induced cardiac impairment. In contrast, administrations of all above agents showed similar effects in attenuating blood pressure up-regulation in the HFFD-fed mice (see Supplementary data online, Figure S5E). These results demonstrate the added benefit of DKK1 inhibition on top of AT1R inhibition in protecting diabetic cardiac impairment. Additionally, conditional LRP5/6 deletion-induced cardiac impairment and blood pressure up-regulations were unaffected by BHQ880 administration (see Supplementary data online, Figure S5F–H), confirming the key role of the DKK1-LRP5/6 axis activation in cardiac impairment and blood pressure up-regulation. Collectively, these findings indicate that DKK1 inhibition is superior to AT1R inhibition in protecting HFFD injuries.

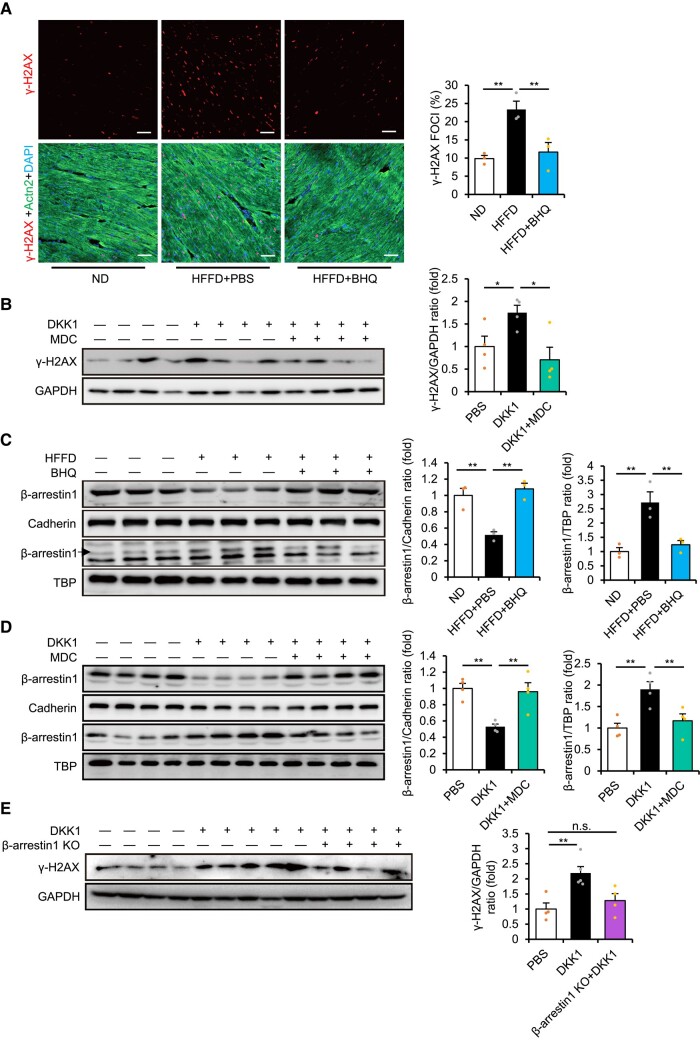

Function of the Dickkopf-1-LDL receptor–related proteins 5 and 6 axis in inducing DNA damage during diabetes

We further explored the underlying mechanism of deleterious DKK1 functions during diabetes. We previously showed that DKK1 administration or LRP5/6 deletions accelerated DNA damage in the ischaemic heart.14 Thus, we investigated whether the DKK1-LRP5/6 axis plays any role in inducing DNA damage response in HFFD-fed diabetic mice using gamma-H2A histone family member X (γ-H2AX), a marker of DNA damage. Interestingly, γ-H2AX up-regulation was observed in the hearts of mice fed long-term with HFFD, which was prevented by the administration of BHQ880 (Figure 6A and Supplementary data online, Figure S6A), suggesting that elevated blood DKK1 levels can induce DNA damage in the diabetic heart. Furthermore, DKK1 injection or global LRP5/6 deletions directly induced γ-H2AX up-regulation in the heart, whereas DKK1 injection-induced γ-H2AX up-regulation was prevented by MDC administration (Figure 6B and Supplementary data online, Figure S6B). Notably, unlike BHQ880, administering ARB or ACEI did not prevent γ-H2AX up-regulation induced by HFFD or DKK1 injection (see Supplementary data online, Figure S6C–E). The results suggest that activation of the DKK1-LRP5/6 axis-induced DNA damage independently of AT1R.

Figure 6.

Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) induces DNA damage response via inducing LRP5/6 endocytosis and activating β-arrestin1. (A) Immunofluorescence staining (left) and quantification (right) of γ-H2AX foci, cardiomyocyte-specific α-actinin 2 (Actn2), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in the heart of high-fat/high-fructose diet (HFFD)-fed mice at Week 3 injected with BHQ880 or phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 2 weeks. n = 3. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, **P < .01 vs. HFFD alone. Scale bar, 25 µm. (B) Representative immunoblots (left) and quantification (right) of γ-H2AX expression in mice following DKK1 injection (1 mg/kg/day) with or without treatment with monodansylcadaverine (MDC) for 4 days. n = 4. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, *P < .05 vs. DKK1 alone. (C) Representative immunoblots (left) and quantification (right) of membrane and nuclear β-arrestin1 expression in the heart of HFFD-fed mice at Week 3 injected with BHQ880 or PBS for 2 weeks. n = 3. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, **P < .01 vs. HFFD alone. (D) Representative immunoblots (left) and quantification (right) of membrane and nuclear β-arrestin1 expression in the heart following injection of DKK1 in combination with MDC treatment for 1 day. n = 4. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, **P < .01 vs. DKK1 alone. (E) Representative immunoblots (left) and quantification (right) of γ-H2AX expression in control or β-arrestin1 knockout mice following injection with DKK1 (1 mg/kg/day) for 4 days. n = 4 or more. One-way ANOVA. Mean ± SEM, **P < .01 vs. DKK1 alone, n.s., no significance

β-arrestin1 was involved in Dickkopf-1-induced DNA damage during diabetes

In addition to directly binding to the GPCRs, Frizzled and CXCR4,12,13 LRP5/6 can interact with several other GPCRs such as LGR4/5 and PTH1R to activate the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway.29,30 Furthermore, siRNA-mediated knockdown of LRP5/6 affected multiple GPCR-related pathways,14 suggesting that LRP5/6 are prone to interact with GPCRs. Our previous findings further showed that translocational alterations of β-arrestin1/2 (as direct and general downstream targets of GPCRs) were rapidly induced by DKK1 stimulation in cultured cardiac cells, which were prevented by MDC administration.14 These results suggest that activation of the DKK1-LRP5/6 axis may cause translocational alterations of β-arrestin1/2 as an outcome of multiple GPCR alterations.

Interestingly, significant down-regulation of membrane LRP5/6 and β-arrestin1 and up-regulation of nuclear β-arrestin1 were observed in the hearts of mice fed HFFD for 3 weeks, which were prevented by the administration of BHQ880 (Figure 6C). Furthermore, DKK1 injection induced similar down-regulation of membrane β-arrestin1 but up-regulation of nuclear β-arrestin1 in the heart, which were attenuated by MDC administration (Figure 6D). Moreover, DKK1 administration induced significant up-regulation of γ-H2AX in the hearts of wild-type mice but not β-arrestin1 knockout mice (Figure 6E). Previously, β-arrestin1 was found to directly participate in the DNA damage response.31 Thus, these results reveal a potentially new DKK1-LRP5/6-β-arrestin1 pathway in inducing DNA damage.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that neutralizing blood DKK1 prevented blood pressure up-regulation and attenuated other diabetic injuries. Because no current blood pressure–lowering strategy prolongs survival in adults with diabetes,6 the beneficial effects of neutralizing blood DKK1 in reducing blood pressure, preserving organ function, and increasing the capacity for physical activity suggest this approach as a promising new therapy for treating diabetic hypertensive patients. It has also been reported that although anti-hypertensive treatment reduces the risk of mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in people with diabetes and an SBP of >140 mmHg, no observed benefits (but rather an increased risk of cardiovascular death) were found for those who had an SBP of <140 mmHg.7,8,32 Our results showed a similar mild extent of blood pressure up-regulation in DKK1-injected or LRP5/6-deleted mice as found with HFFD-fed and STZ-treated diabetic mice, suggesting that mild blood pressure up-regulation in diabetic patients may be related to elevated blood DKK1 levels, which may pose a serious health threat and should not be overlooked. Hence, in addition to currently used clinical examinations and therapy in patients with diabetes, monitoring and eliminating excess blood DKK1 (even in those with only mild blood pressure increases) may be of great importance.

Because Wnt/β-catenin signalling is one of the most important pathways during development, it is unsurprising that mice with deletions of the Wnt co-receptors, LRP5/6, died shortly after gastrulation.33 However, it is surprising that conditional deletions of LRP5/6 during adulthood led to blood pressure up-regulation and further acted as GPCR-regulating proteins during adulthood. We demonstrated that LRP6 inhibited AT1R, the most important GPCR in regulating blood pressure, via directly binding to it. Furthermore, DKK1 activated AT1R signalling by inducing membrane LRP5/6 endocytosis and releasing LRP5/6-bound AT1R. Importantly, elevated blood DKK1 levels, induced by high blood glucose during diabetic hypertension, led to hypertension by activating LRP5/6-AT1R signalling, demonstrating that DKK1 is highly sensitive for up-regulating blood pressure. Thus, our findings reveal a novel DKK1-LRP5/6-AT1R pathway in regulating diabetic hypertension. Furthermore, in addition to interacting with AT1R, LRP5/6 can directly bind to and inhibit the GPCRs, Frizzled and CXCR4,12,13 and interact with several other GPCRs (such as LGR4/5 and PTH1R) to activate the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathways.29,30 These results suggest that LRP5/6 are prone to interact with GPCRs. In support of this possibility, siRNA-mediated knockdown of LRP5/6 affected multiple GPCR-related pathways.14 Further investigations may reveal additional LRP5/6-binding GPCR partners or new mechanisms involved in the development of other diseases. Thus, LRP5/6 appear to be general regulators of multiple GPCRs; hence, impaired homeostasis of LRP5/6 (such as during DKK1-induced LRP5/6 endocytosis) may induce the dysregulation of LRP5/6-interacting GPCRs and lead to organ injury (Structured Graphical Abstract). Indeed, the wide-ranging complications that result from diabetic injury may result from the dysregulation of multiple GPCRs, whose precise mechanisms require further investigation. At present, β-arrestin1 appears to be involved in DKK1-induced DNA damage as the general outcome of multiple GPCR alterations.

It is noteworthy that high circulating DKK1 levels were observed in diabetic patients and correlated closely with cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis, although the mechanisms underlying the deleterious functions of DKK1 have not been reported.34–43 Notably, hyperglycaemia is known to develop osteoporosis.44,45 Interestingly, the results of phase II clinical trial of myeloma treatment showed that neutralizing blood DKK1 by administering BHQ880 promoted increased bone mineral density and bone strength.42,46 Combined with the effect of BHQ880 in preventing hypertension and cardiac impairment, as observed in this study, neutralizing DKK1 signalling should be effective for a broad range of diabetic therapies. In this regard, although ARBs are one of the most commonly used anti-hypertension drugs, they appear to be less effective in reducing the simultaneous occurrence of other stressors beyond hypertension.47,48

There are several limitations to our study. Due to the large numbers of statistical tests performed in the study, it is likely that one or more type I errors may have occurred. Additionally, although multiple blood pressure measurements were recorded to ensure accuracy, the lack of ambulatory blood pressure measures to confirm the blood pressure values makes it impossible to exclude the potential influence of white coat hypertension or masked hypertension in the population. Further, even though our analysis provided experimental evidence of the robust ability of anti-DKK1 neutralizing antibody in preventing wide-ranging diabetic injuries in addition to diabetic hypertension, it will be important to further establish their functional effect in real-world applications such as randomized controlled trials. Finally, whether the monitoring and elimination of serum DKK1 prolongs survival in clinical therapy of diabetic hypertension requires further human investigations.

Taken together, our results suggest that neutralizing elevated blood DKK1 levels shows promise for future clinical therapy and may be key for improving the health and survival for the ever-growing number of patients with diabetic hypertension worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr BO. Williams for providing LRP5/6fl/fl mice and Dr X. He and Dr C. Niehrs for providing plasmids.

Contributor Information

En Ma, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China; Clinical and Translational Research Center, Research Institute of Heart Failure Shanghai East Hospital, Key Laboratory of Arrhythmias of Ministry of Education, Tongji University School of Medicine, 1239 Siping Road, Yangpu, Shanghai, China.

Da Wo, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China.

Jinxiao Chen, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China.

Hongwei Yan, Clinical and Translational Research Center, Research Institute of Heart Failure Shanghai East Hospital, Key Laboratory of Arrhythmias of Ministry of Education, Tongji University School of Medicine, 1239 Siping Road, Yangpu, Shanghai, China.

Xiaohui Zhou, Clinical and Translational Research Center, Research Institute of Heart Failure Shanghai East Hospital, Key Laboratory of Arrhythmias of Ministry of Education, Tongji University School of Medicine, 1239 Siping Road, Yangpu, Shanghai, China.

Jia He, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China.

Celiang Wu, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China.

Qing Wang, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China.

Changjing Zuo, Department of Nuclear Medicine, Changhai Hospital, Shanghai, China.

Xiao Li, Department of Nuclear Medicine, Changhai Hospital, Shanghai, China.

Li Li, Department of Health Management, Shengli Clinical College of Fujian Medical University, Fujian Provincial Hospital, Fuzhou, China.

Qingshu Meng, Clinical and Translational Research Center, Research Institute of Heart Failure Shanghai East Hospital, Key Laboratory of Arrhythmias of Ministry of Education, Tongji University School of Medicine, 1239 Siping Road, Yangpu, Shanghai, China.

Liang Zheng, Clinical and Translational Research Center, Research Institute of Heart Failure Shanghai East Hospital, Key Laboratory of Arrhythmias of Ministry of Education, Tongji University School of Medicine, 1239 Siping Road, Yangpu, Shanghai, China.

Luying Peng, Clinical and Translational Research Center, Research Institute of Heart Failure Shanghai East Hospital, Key Laboratory of Arrhythmias of Ministry of Education, Tongji University School of Medicine, 1239 Siping Road, Yangpu, Shanghai, China.

Lidian Chen, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China.

Jun Peng, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China.

Dan-ni Ren, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China.

Weidong Zhu, Innovation and Transformation Center, Collaborative Innovation Center for Rehabilitation Technology, Fujian Key Laboratory of Integrative Medicine on Geriatrics, Academy of Integrative Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1 Qiuyang Road, Minhou, Fuzhou 350122, China; Clinical and Translational Research Center, Research Institute of Heart Failure Shanghai East Hospital, Key Laboratory of Arrhythmias of Ministry of Education, Tongji University School of Medicine, 1239 Siping Road, Yangpu, Shanghai, China.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at European Heart Journal online.

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

All authors declare no disclosure of interest for this contribution.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82074190), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province for Distinguished Young Scholars (2022J06027), Scientific Research Foundation for the Top Youth Talents of Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (XQB202201), Scientific Research Foundation for the High-level Talents, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (X2019001-talent, X2021001-talent, X2021002-talent, X2021003-talent), Shanghai Key Medical Discipline for Critical Care Medicine (2017zz02017), and the Top-level Clinical Discipline Project of Shanghai Pudong (PWYgf2018-05).

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethics Committee of Shanghai East Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, approved this study protocol (number: ECSEH2017-010). All enrolled subjects gave written informed consent. All animal studies have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Fujian, China) and comply with the ARRIVE guidelines and were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Pre-registered Clinical Trial Number

None supplied.

Translational perspective.

An anti-DKK1 neutralizing antibody (BHQ880, Novartis) has been used in clinical trials for cancer treatment and shown to be safe. Notably, unlike current anti-hypertensive agents, BHQ880 administration prevented hypertension and in addition preserved left ventricular ejection fraction in a diabetic murine model. Additionally, due to the ease in clinical monitoring of serum DKK1 changes, serum DKK1 may be an ideal target for improving the general health of hypertensive diabetic patients. Further clinical investigations on BHQ880 in preventing diabetic injuries may resolve the long-standing conundrum that blood pressure–lowering strategies are not superior to placebo treatments with respect to survival in hypertensive diabetic patients.

References

- 1. Unwin N. The metabolic syndrome. J R Soc Med 2006;99:457–62. 10.1177/014107680609900917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gallagher EJ, Leroith D, Karnieli E. The metabolic syndrome–from insulin resistance to obesity and diabetes. Med Clin North Am 2011;95:855–73. 10.1016/j.mcna.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1113–32. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferrannini E, Cushman WC. Diabetes and hypertension: the bad companions. Lancet 2012;380:601–10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60987-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014;311:507–20. 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Palmer SC, Mavridis D, Navarese E, Craig JC, Tonelli M, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of blood pressure-lowering agents in adults with diabetes and kidney disease: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 2015;385:2047–56. 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62459-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, Callender T, Perkovic V, Patel A. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;313:603–15. 10.1001/jama.2014.18574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brunström M, Carlberg B. Association of blood pressure lowering with mortality and cardiovascular disease across blood pressure levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:28–36. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wehrli M, Dougan ST, Caldwell K, O'Keefe L, Schwartz S, Vaizel-Ohayon D, et al. Arrow encodes an LDL-receptor-related protein essential for wingless signalling. Nature 2000;407:527–30. 10.1038/35035110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, et al. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature 2000;407:530–5. 10.1038/35035117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pinson KI, Brennan J, Monkley S, Avery BJ, Skarnes WC. An LDL-receptor-related protein mediates Wnt signalling in mice. Nature 2000;407:535–8. 10.1038/35035124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ren DN, Chen J, Li Z, Yan H, Yin Y, Wo D, et al. LRP5/6 directly bind to Frizzled and prevent Frizzled-regulated tumour metastasis. Nat Commun 2015;6:6906. 10.1038/ncomms7906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang J, Chen J, Wo D, Yan H, Liu P, Ma E, et al. LRP6 ectodomain prevents SDF-1/CXCR4-induced breast cancer metastasis to lung. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:4832–45. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-3557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wo D, Peng J, Ren DN, Qiu L, Chen J, Zhu Y, et al. Opposing roles of Wnt inhibitors IGFBP-4 and Dkk1 in cardiac ischemia by differential targeting of LRP5/6 and β-catenin. Circulation 2016;134:1991–2007. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Franklin SS, Wt G, Wong ND, Larson MG, Weber MA, Kannel WB, et al. Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1997;96:308–15. 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sleight P. Lowering of blood pressure and artery stiffness. Lancet 1997;349:362. 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)62869-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Witteman JC, Grobbee DE, Valkenburg HA, van Hemert AM, Stijnen T, Burger H, et al. J-shaped relation between change in diastolic blood pressure and progression of aortic atherosclerosis. Lancet 1994;343:504–7. 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91459-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mao B, Wu W, Li Y, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Glinka A, et al. LDL-receptor-related protein 6 is a receptor for Dickkopf proteins. Nature 2001;411:321–5. 10.1038/35077108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mao B, Wu W, Davidson G, Marhold J, Li M, Mechler BM, et al. Kremen proteins are Dickkopf receptors that regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nature 2002;417:664–7. 10.1038/nature756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cadigan KM, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development. Genes Dev 1997;11:3286–305. 10.1101/gad.11.24.3286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2004;20:781–810. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qian J, Xie J, Hong S, Yang J, Zhang L, Han X, et al. Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) is a widely expressed and potent tumor-associated antigen in multiple myeloma. Blood 2007;110:1587–94. 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu B, Yang X, Xu Y, Yao G, Shu H, Lin B, et al. Elevated expression of DKK1 is associated with cytoplasmic/nuclear beta-catenin accumulation and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinomas. J Hepatol 2009;50:948–57. 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato N, Yamabuki T, Takano A, Koinuma J, Aragaki M, Masuda K, et al. Wnt inhibitor Dickkopf-1 as a target for passive cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res 2010;70:5326–36. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-09-3879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamamoto H, Sakane H, Yamamoto H, Michiue T, Kikuchi A. Wnt3a and Dkk1 regulate distinct internalization pathways of LRP6 to tune the activation of beta-catenin signaling. Dev Cell 2008;15:37–48. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chobanian AV. Shattuck Lecture. The hypertension paradox–more uncontrolled disease despite improved therapy. N Engl J Med 2009;361:878–87. 10.1056/NEJMsa0903829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu Y, Li Q, Chen XZ. Detecting protein-protein interactions by far western blotting. Nat Protoc 2007;2:3278–84. 10.1038/nprot.2007.459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qiao Y, Shin JI, Chen TK, Inker LA, Coresh J, Alexander GC, et al. Association between renin-angiotensin system blockade discontinuation and all-cause mortality among persons with low estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:718–26. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Lau W, Barker N, Low TY, Koo BK, Li VS, Teunissen H, et al. Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature 2011;476:293–7. 10.1038/nature10337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wan M, Yang C, Li J, Wu X, Yuan H, Ma H, et al. Parathyroid hormone signaling through low-density lipoprotein-related protein 6. Genes Dev 2008;22:2968–79. 10.1101/gad.1702708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hara MR, Kovacs JJ, Whalen EJ, Rajagopal S, Strachan RT, Grant W, et al. A stress response pathway regulates DNA damage through β2-adrenoreceptors and β-arrestin-1. Nature 2011;477:349–53. 10.1038/nature10368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brunström M, Carlberg B. Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2016;352:i717. 10.1136/bmj.i717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kelly OG, Pinson KI, Skarnes WC. The Wnt co-receptors Lrp5 and Lrp6 are essential for gastrulation in mice. Development 2004;131:2803–15. 10.1242/dev.01137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhu ZB, Guo DX, Zhong CK, Wang AL, Xie XW, Xu T, et al. Serum Dkk-1 (Dickkopf-1) is a potential biomarker in the prediction of clinical outcomes among patients with acute ischemic stroke. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2019;39:285–93. 10.1161/atvbaha.118.311960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Garcia-Martin A, Reyes-Garcia R, Garcia-Fontana B, Morales-Santana S, Coto-Montes A, Munoz-Garach M, et al. Relationship of Dickkopf1 (DKK1) with cardiovascular disease and bone metabolism in Caucasian type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 2014;9:e111703. 10.1371/journal.pone.0111703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miranda TS, Napimoga MH, Feres M, Marins LM, da Cruz DF, da Silva HDP, et al. Antagonists of Wnt/β-catenin signalling in the periodontitis associated with type 2 diabetes and smoking. J Clin Periodontol 2018;45:293–302. 10.1111/jcpe.12854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Faienza MF, Ventura A, Delvecchio M, Fusillo A, Piacente L, Aceto G, et al. High sclerostin and Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) serum levels in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:1174–81. 10.1210/jc.2016-2371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lattanzio S, Santilli F, Liani R, Vazzana N, Ueland T, Di Fulvio P, et al. Circulating dickkopf-1 in diabetes mellitus: association with platelet activation and effects of improved metabolic control and low-dose aspirin. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e001000. 10.1161/jaha.114.001000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ghardashi-Afousi A, Davoodi M, Hesamabadi BK, Asvadi-Fard M, Bigi MAB, Izadi MR, et al. Improved carotid intima-media thickness-induced high-intensity interval training associated with decreased serum levels of Dkk-1 and sclerostin in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2020;34:107469. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2019.107469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klingenschmid G, Tschiderer L, Himmler G, Rungger G, Brugger S, Santer P, et al. Associations of serum Dickkopf-1 and sclerostin with cardiovascular events: results from the prospective Bruneck study. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e014816. 10.1161/jaha.119.014816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ueland T, Akerblom A, Ghukasyan T, Michelsen AE, Becker RC, Bertilsson M, et al. Admission levels of DKK1 (Dickkopf-1) are associated with future cardiovascular death in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2019;39:294–302. 10.1161/atvbaha.118.311042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pinzone JJ, Hall BM, Thudi NK, Vonau M, Qiang YW, Rosol TJ, et al. The role of Dickkopf-1 in bone development, homeostasis, and disease. Blood 2009;113:517–25. 10.1182/blood-2008-03-145169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Neto R, Pereira L, Magalhaes J, Quelhas-Santos J, Martins S, Carvalho C, et al. Sclerostin and DKK1 circulating levels associate with low bone turnover in patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3 and 4. Clin Kidney J 2021;14:2401–8. 10.1093/ckj/sfab081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yaturu S, Humphrey S, Landry C, Jain SK. Decreased bone mineral density in men with metabolic syndrome alone and with type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Monit 2009;15:CR5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wong SK, Chin KY, Suhaimi FH, Ahmad F, Ima-Nirwana S. The relationship between metabolic syndrome and osteoporosis: a review. Nutrients 2016;8:347. 10.3390/nu8060347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iyer SP, Beck JT, Stewart AK, Shah J, Kelly KR, Isaacs R, et al. A phase IB multicentre dose-determination study of BHQ880 in combination with anti-myeloma therapy and zoledronic acid in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma and prior skeletal-related events. Br J Haematol 2014;167:366–75. 10.1111/bjh.13056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marques-Vidal P, Vollenweider P, Waeber G. Angiotensin receptor blockers are not associated with reduced inflammatory markers in the general population. J Hypertens 2015;33:2173–8. 10.1097/hjh.0000000000000683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Umebayashi R, Uchida HA, Okuyama Y, Kakio Y, Hanayama Y, Shikata K, et al. The clinical efficacy of angiotensin II type1 receptor blockers on inflammatory markers in patients with hypertension: a multicenter randomized-controlled trial; MUSCAT-3 study. Biomarkers 2019;24:255–61. 10.1080/1354750x.2018.1548033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.