Abstract

Construction of C‒C bonds in medicinal chemistry frequently draws on the reductive coupling of organic halides with ketones or aldehydes. Catalytic C(sp3)‒C(sp3) bond formation, however, is constrained by the competitive side reactivity of radical intermediates following sp3 organic halide activation. Here, an alternative paradigm deploys catalytic Ag surfaces for reductive fragment-based electrophile coupling compatible with sp3 organic halides. We use in-situ spectroscopy, electrochemical analyses, and simulation to uncover the catalytic interfacial structure and guide reaction development. Specifically, Mg(OAc)2 outcompetes the interaction between Ag and the aldehyde, thereby tuning the Ag surface for selective product formation. Data are consistent with an increased population of Mg-bound aldehyde facilitating the addition of a carbon-centered radical (product of Ag-electrocatalyzed organic halide reduction) to the carbonyl. Electron transfer from Ag to the resultant alkoxy radical yields the desired alcohol. Molecular interfacial tuning at reusable catalytic electrodes will accelerate development of sustainable organic synthetic methods.

Graphical Abstract

Demand for catalytic fragment-based C‒C bond-forming methods using sp3 organic halides is supported by the increasing prevalence of successful drug candidates that contain sp3 carbons,1–3 alongside the availability of sp3 organic halide feedstocks. Traditional methods to prepare C(sp3)‒C(sp3) bonds between sp3 organic halides and ketones or aldehydes rely on non-catalytic reactions that utilize organometallic reagents (e. g., Grignard4 or organolithium5)6 or intermediates (e. g., Barbier reactions7,8). In contrast, the catalytic reductive coupling of sp2 or sp organic halides (e.g., aryl, vinyl, alkynyl halides) with ketones or aldehydes is well-documented (e.g., Nozaki-Hiyama-Kishi reactivity,9 Ni,10 and Rh11 catalysis) and utilized in a variety of synthetic campaigns. These methods require the concerted, two-electron oxidative addition of the sp2 or sp organic halide to the homogeneous metal catalyst. In contrast, the oxidative addition of sp3 organic halide electrophiles typically proceed via single electron transfer, leading to radical intermediates. These intermediates hinder the selectivity of the desired reaction by competitive homocoupling (e.g., Wurtz coupling for benzyl halides12), β-scission (i.e., the addition of the carbon-centered radical to a carbonyl moiety is endergonic13–15), or competitive β-hydride elimination16. Outer-sphere electron transfer (OSET) to sp3 organic halide electrophiles can circumvent these radical intermediates via radical-polar crossover,17–19 forming an anion that can add into the ketone or aldehyde. However, this paradigm limits the scope of the aldehyde/ketone because they are competitively reduced, as the OSET reduction potentials of organic halides are nearly identical with that of the aldehyde/ketone,19,20 (Figure 1a), and the formation of a highly basic carbanion limits its compatibility with enolizable electrophiles.

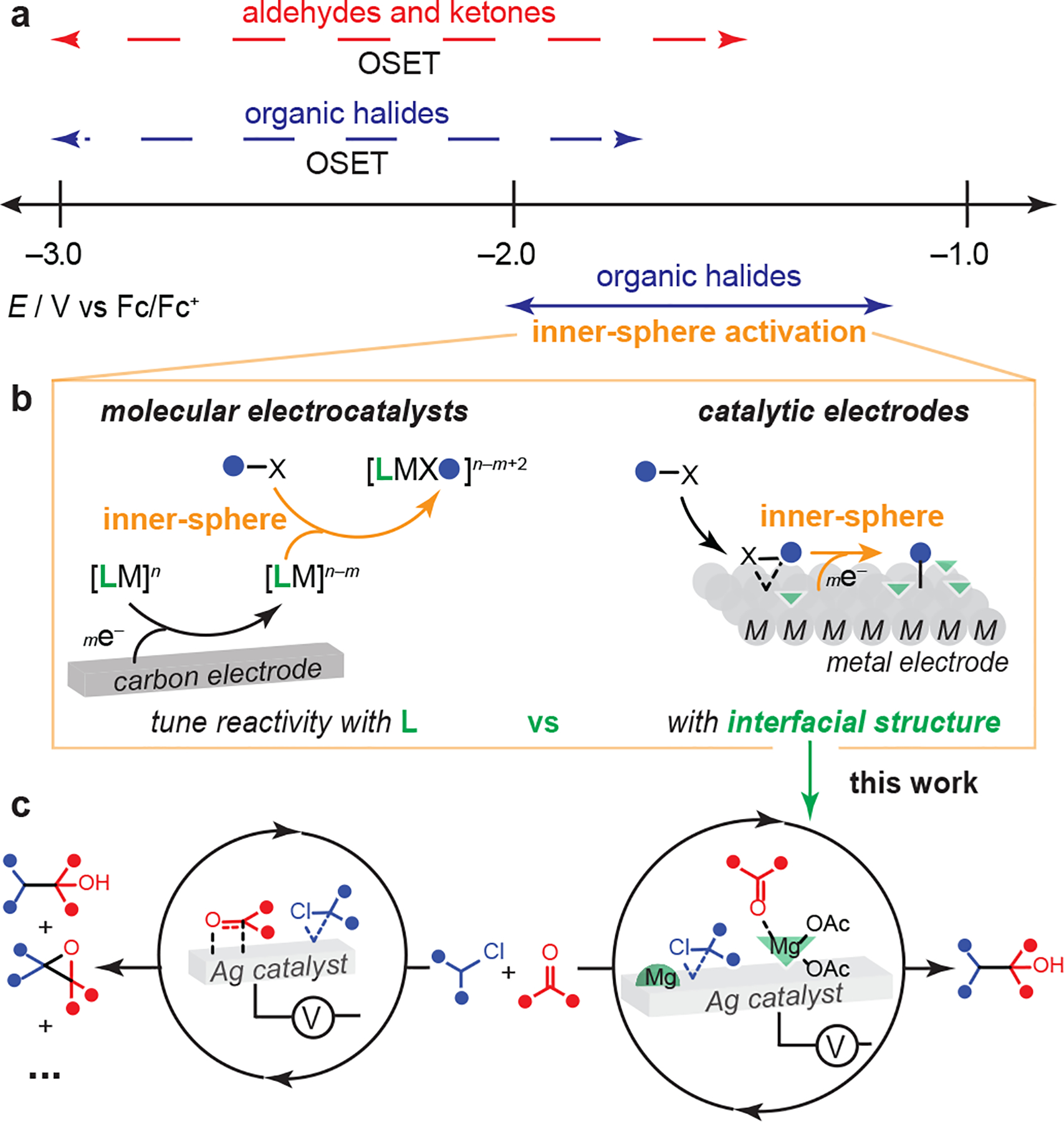

Figure 1. Electrocatalysis enables facile organic halide activation.

(a) Selective reductive activation of organic halides over aldehydes and ketones is limited due to the similar reduction potentials accessed via outer-sphere electron transfer (OSET). (b) Inner-sphere reductive activation of organic halides via molecular electrocatalysis or catalytic electrodes drives the reduction potential of organic halides to more positive potentials. (c) This work uncovers the interfacial structure at catalytic Ag electrodes that enables selective electrophile coupling.

To access sp3 organic halide reduction at more mild potentials, catalysis that drives inner-sphere activation is required (Figure 1a). Indeed, in complementary reactivity involving sp2 organic halide activation, molecular electrocatalysts have been utilized to access reductive aldehyde functionalization reactions21 (Figure 1b). An alternative paradigm for this reaction class is to directly employ the electrode surface as the catalyst, i.e., using catalytic electrodes. Ag has been shown to reductively activate sp3 organic halides22–28 at potential values that are ~500 mV more positive (i.e., ~11 kcal mol−1 lower energy barrier) than carbon24 (Figure 1a). This reactivity, which is analogous to the homogeneous oxidative addition of sp3 organic halide electrophiles following metal reduction,29–31 has been leveraged to enable electrocatalytic hydrodehalogenation,28 carboxylation,32–34 and radical cyclization reactions.26 Recent work has revealed the synthetic advantages of Ag-modified electrodes in reaction schemes beyond reductive sp2 organic halide activation, enabling cooperative behavior with homogeneous Ni electrocatalysts to facilitate decarboxylative electrophile coupling.35,36 While homogeneous electrocatalysts have a well-defined substrate binding site, and thus are amenable to reaction optimization via ligand design, extended metal structures, such as Ag, exhibit multiple possible binding sites at the electrified surface. Thus, control over reaction selectivity must be driven by interfacial chemistries to direct synthetic outcomes (Figure 1b). However, the interfacial structure during electroorganic synthesis remains unknown due to the lack of methodology development guided by insights from in-situ and surface-sensitive spectroscopies. This structural black box impedes the development of methods that rationally deploy catalytic electrodes.

Here, we use in-situ spectroscopy, electrochemical analyses, and simulation to discover that Ag-electrocatalyzed reductive coupling reactions between sp3 organic chlorides and aldehydes/ketones are selective in the presence of magnesium diacetate, Mg(OAc)2 (Figure 1c). We reveal that Mg(OAc)2 not only activates the aldehyde but also changes the interfacial structure of the catalytic Ag surface. The Lewis acid redirects competitive aldehyde binding to the Ag surface. This finding enables us to develop a reductive, catalytic method to form C(sp3)‒C(sp3) bonds between sp3 organic chlorides and ketone/aldehydes with a wide substrate scope.

Results

Mg(OAc)2 Enhances Ag-Catalyzed Electrophile Coupling.

To examine the baseline efficacy of Ag-electrocatalyzed electrophile coupling, we chose the model substrates, m-cyanobenzyl chloride (mCNBzCl) and p-anisaldehyde (pAN). These substrates were chosen because the nitrile group enables us to track mCNBzCl via in-situ infrared spectroscopy (see below); the reduction potential for pAN is sufficiently negative that it does not compete with the Ag-electrocatalyzed mCNBzCl reduction; and chloride, a product of the reductive activation, does not readily poison Ag37. Figure 2b shows the differences in the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of mCNBzCl reduction on glassy carbon (GC) and on Ag electrodes in dimethylformamide (DMF) containing tetrabutylammonium perchlorate (TBAClO4). On Ag, we observe a reductive feature at a peak potential (EISET) of −2.00 V vs Fc/Fc+ (all potentials are reported versus Fc/Fc+) (Figure 2b, black), attributed to the Ag-electrocatalyzed reduction of the carbon-halogen bond.23 Bulk electrolysis of the electrolyte mixture near EISET yields products in line with this reactivity; m-tolunitrile and dimerized products are observed (Supplementary Figure 1). In contrast, on GC, we observe a 310-mV negative shift in the initial reductive feature (Figure 2b, grey), consistent with previous observations for organic chlorides.23,38,39 This shift is attributed to the pre-adsorption of the electrophile to the Ag surface, lowering the barrier for reduction, as well as the favorable thermodynamics associated with the liberated halide adsorption to the surface (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3).40 Thus, the reduction at −2.31 V on GC is attributed to the catalyzed, outer-sphere reduction of mCNBzCl, EOSET, mCNBzCl. The peak at −2.74 V (Figure 2b, black) is attributed to the reduction of the benzonitrile moiety (Supplementary Figure 4).20 Figure 2c shows the CV of pAN alone. In contrast to the voltametric behavior observed for mCNBzCl, the reduction of pAN on both electrodes (Figure 2c, black and grey) exhibit an identical peak potential of −2.53 V, demonstrating that this potential corresponds to the direct, uncatalyzed reduction of pAN (EOSET, pAN). Together, these data demonstrate that the electrocatalytic activity of Ag towards mCNBzCl enables the reductive activation of mCNBzCl over pAN at EISET.

Figure 2. Electrochemical and reactivity data for Ag-catalyzed electrophile coupling.

(a) Observed reactivity between 40 mM mCNBzCl and 120 mM pAN at −2.23 V vs Fc/Fc+ with and without 44 mM Mg(OAc)2. m-cyanotoluene yield was determined by GCMS of the crude reaction mixture. All other product yields are isolated yields after chromatography on silica gel. (b) Cyclic voltammetry (CV) of 40 mM mCNBzCl on glassy carbon (grey), Ag (black) and Ag in the presence of 44 mM Mg(OAc)2 (green) at 100 mVs−1. (c) CV of 40 mM pAN on glassy carbon (grey), Ag (black) and Ag in the presence of 44 mM Mg(OAc)2 (green) at 100 mVs−1. (d) CV of 40 mM mCNBzCl and 40 mM pAN on Ag at 100 mVs−1 on Ag in the absence (black) and presence (green) of 44 mM Mg(OAc)2 at 100 mVs−1. All CVs are conducted with a negative direction of scan. (e) Chronoamperometry trace of 40 mM mCNBzCl and 120 mM pAN at −2.23 V vs Fc/Fc+ in the absence (black) and presence (green) of 44 mM Mg(OAc)2. All experiments are conducted in DMF containing 0.05 M TBAClO4.

The Ag-catalyzed reductive coupling of mCNBzCl and pAN is unselective. Figure 2d, black, shows the CV for both electrophile partners on Ag. We observe a voltametric feature −2.06 V, (Figure 2d, black), assigned to the catalytic reduction of mCNBzCl (i.e., EISET, also observed in the absence of pAN, Figure 2b). We additionally observe a new feature at −2.46 V (Enew), which is not observed for mCNBzCl (Figure 2b, black) or pAN reduction alone (Figure 2c, black). The reductive current associated with the third peak at −2.55 V (Figure 2d, black) grows with sequential titration of pAN to mCNBzCl (Supplementary Figure 5), and thus we attribute this peak to the direct reduction of pAN (EOSET). As the feature at Enew does not similarly increase as a function of pAN concentration (Supplementary Figure 5), these results suggest that Enew reports on a reductive event that follows a bimolecular reaction between pAN and reduced mCNBzCl. To examine the reactivity between the two species preceding Enew, we conducted a bulk electrolysis experiment at −2.23 V (near EISET). The current drops off (Figure 2e, black) after the passage of 1 F mol−1 of mCNBzCl, indicative of one-electron consumption per substrate. Analysis of the reaction mixture surprisingly shows the presence of an epoxide product (25%, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 6), in addition to the desired alcohol product (36%) and dehalogenated product (3%), Figure 2a. We interpret these results to suggest that the reaction proceeds via the intermediacy of an alkoxy radical, which disproportionates to form the epoxide and the alcohol. The reductive formation of an alkoxy radical intermediate at Enew is supported by the observation of a reductive wave at an identical potential for the independently synthesized alkoxyphthalimide derivative (Supplementary Figure 7a and b).41 At Enew, we thus hypothesize that the alkoxy radical is further reduced by one electron. Bulk electrolysis of the alkoxyphthalimide derivative leads to the formation of the epoxide product. These results provide further support for the formation of an open-shell alkoxy radical (Supplementary Figure 7c), although they do not discount an alternative pathway proceeding via an oxonium species under the conditions of Ag-catalyzed electrophile coupling. Our results demonstrate that the baseline reactivity for the reductive coupling between the electrophiles by Ag electrocatalysis results in an unselective, radical-based process, leading to both the desired alcohol product as well as the epoxide.

We discover that Mg(OAc)2 enables selective Ag-catalyzed reductive coupling of mCNBzCl and pAN. Bulk electrolysis experiments conducted near EISET in the presence of Mg(OAc)2 enables the formation of near-quantitative alcohol product (94%) after the passage of 2 F mol−1 of mCNBzCl (Figure 2e, green, Supplementary Figure 8). To demonstrate the importance of the catalytic Ag electrode in enabling selective product formation, we show that use of carbon cathodes instead of Ag, Supplementary Table 2, leads to a 44% drop in product yield. To examine the effect of the Mg(OAc)2 on the reaction, we performed analogous CV experiments on Ag in the presence of both electrophile partners (Figure 2d, green). In the presence of Mg(OAc)2, the reduction peak at Enew disappears while the peak at EISET remains. Importantly, the peak current density value at EISET is approximately two-fold increased. These results suggest that the presence of Mg(OAc)2 levels out the two separate single-electron redox events at EISET and Enew down to an apparent two-electron redox event at a single potential (i.e., Enew equals EISET, or Enew > EISET). This analysis is consistent with the net two-electron reactivity and observed selective alcohol formation. Sequential titration of Mg(OAc)2 into the electrolyte (Supplementary Figure 9) demonstrates that this hypothesized redox-leveling effect is dependent on the concentration of the Lewis acid in solution. To examine the effect of Mg(OAc)2 individually on each electrophile alone, we performed analogous CV experiments. Figure 2b (green) depicts the CV of mCNBzCl on Ag with Mg(OAc)2. Similar to the trace collected in the absence of Mg(OAc)2 (Figure 2b, black), we observe that the Ag catalyzes the activation of the substrate at −2.07 V (Figure 2b, green), suggesting that Mg(OAc)2 does not significantly alter the reductive activation of the carbon halogen bond. In line with this hypothesis, bulk electrolysis of mCNBzCl alone in the presence of Mg(OAc)2 at −2.23 V yields a product profile similar to that observed in the absence of the Lewis acid (Supplementary Figure 10). Figure 2c (green) depicts the CV of pAN alone on Ag with Mg(OAc)2. In the presence of Mg(OAc)2, the reduction of pAN exhibits a positive 80-mV shift (Figure 2c, green). This result suggests that the Lewis acid coordinates with pAN, thereby enabling more facile reduction.42–44 We also observe the disappearance of the back oxidation peak current (jp,a) (Figure 2c, green). Identical behavior is observed on GC electrodes (Supplementary Figure 11), and the bulk electrolysis of pAN alone in the presence of Mg(OAc)2 yields pinacol (Supplementary Figure 12b). The disappearance of jp,a combined with the observation of the pinacol product suggests that Mg(OAc)2 accelerates the rate of pinacol formation, i.e., the dimerization rate of the reductively generated ketyl radical at EOSET to form the pinacol outcompetes the rate of its back oxidation (jp,a).45 Indeed, theoretical working curves (Supplementary Figure 12a) and electroanalytical studies (Supplementary Figures 13 and 14) reveal that the rate of dimerization in the presence of Mg(OAc)2 is increased by two orders of magnitude (Supplementary Table 3). We note that the 19F NMR of p-fluorobenzylaldehyde do not show a significant peak shift in the presence Mg(OAc)2 (Supplementary Figure 15)46, suggesting that the Lewis acid does not bind to the aldehyde in major equilibrium. Thus, these results implicate that Mg(OAc)2 interacts with pAN in a minor equilibrium prior to electron transfer.42,44 Together, these results suggest that Mg(OAc)2 coordinates with pAN in minor equilibrium and yields the selective two-electron reduced C‒C coupled product at catalytic Ag electrodes by leveling out two redox events occurring at disparate potentials into one.

The observed two-electron reactivity could involve the electrochemical preparation of a Mg(mCNBz)OAc Grignard reagent47 followed by nucleophilic attack to the aldehyde. To investigate this possibility, we pre-electrolyzed mCNBzCl in the presence of Mg(OAc)2 at −2.23 V, then pAN was introduced. We do not observe any alcohol product (Supplementary Figure 16), demonstrating that the reaction does not proceed via a long-lived solution-dissolved Grignard. An alternative mechanism for the observed selective reactivity is via the formation of a surface Grignard at an electrodeposited Mg site on Ag. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) (Supplementary Figures 17 and 18) was measured after bulk electrolysis. Indeed, features at 1301.8 eV and 48.1 eV were observed, consistent with the presence of Mg0 on the Ag surface.48 However, when we subject the Ag electrode with the Mg0 deposit to the standard reaction conditions without added Mg(OAc)2, no significant quantities of the alcohol product were obtained (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figures 19 and 20). These results indicate that the observed Mg0 is not catalytically competent. In addition, the observation of 2 F mol−1 reactivity in the presence of Mg(OAc)2 coupled with near-quantitative alcohol formation rules out bulk Mg electrodeposition as a predominant mechanistic pathway to form Mg0 on the Ag surface, i.e., the Faradaic efficiency for alcohol formation is near unity. Thus, our data show that the redox-leveling effects only occur in the presence of solution-dissolved Mg(OAc)2, thereby ruling out a predominant mechanistic scheme in which the Ag electrocatalyst enables the formation of a long-lived, in-situ formed solution-dissolved Grignard reagent or a surface Grignard at an electrodeposited Mg0 site, which then adds into the aldehyde.

We investigated the role of the Lewis acid composition. Supplementary Table 4 shows that Mg(OAc)2 exhibited the highest yield of the alcohol product, while MgBr2, Mg(OTf)2 and Mg(ClO4)2 passivated the Ag electrode. Titrating TBAClO4 or TBAOAc (Supplementary Figures 21 and 22) to the electrolyte resulted in identical voltammetry to those observed in the absence of Mg(OAc)2, ruling out mechanisms where changes in the ionic strength or the OAc− concentration contribute to the observed selectivity enhancement. Studies have shown that the Mg2+ solvation determines the migration of the cation to the electrode surface and the formation of a passivating layer at the electrode interface.49 Our data highlight that the OAc− serves to balance out the competing factors of surface passivation and Mg2+ solvation to enable robust synthesis at catalytic Ag electrodes.

Mg(OAc)2 Liberates Aldehyde Interacting with Ag.

To identify the structural role of Mg(OAc)2 at the catalytic surface under the reaction conditions, we utilized in-situ surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS) in an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode.50,51 This technique leverages nanostructured surfaces to amplify IR absorption of molecules with normal modes perpendicular to the surface. SEIRAS is ideally suited to characterize the interfacial structure because the technique is sensitive to distances within ~8 nm of the polarized surface; and independent of the solution background.50,51 We prepared a new SEIRAS-active Ag film via the electrodeposition of Ag onto Au52,53 (see Methods). The film exhibited a pristine Ag surface with no detectable Au/Si signals by XPS (Supplementary Figure 23). The Ag/Au/Si composite film was evaluated for the electrocatalytic reaction in the presence of Mg(OAc)2. Near-identical reactivity to the commercial Ag electrodes was observed (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Figure 24). These results demonstrate that the SEIRAS-active Ag film is representative of the bulk reactivity evaluated above.

In the absence of Mg(OAc)2, both electrophile partners interact with the Ag surface. Figures 3a and 3b depict the chronoamperometry trace and the associated SEIRA spectra. A reference spectrum was collected (Figure 3b, grey) at −1.03 V, where no catalysis occurs. mCNBzCl was injected (Figure 3b, blue), and a distinct nitrile absorption at 2231 cm−1 was observed (Supplementary Figures 25b and 26). As the CN stretching of the cyanophenyl moiety is sensitive towards metal-coordination and changes in interfacial electric fields,54,55 the identical wavenumber observed for the free nitrile group (Supplementary Figure 26) suggests that the major species observed at −1.03 V is unbound mCNBzCl. The addition of pAN (Figure 3b, red) results in IR absorption bands at 1604, 1579, 1511, 1316, 1258, 1163 and 1025 cm−1. The peaks at 1579, 1511, 1316, 1258, 1163 and 1025 are in line with peaks observed for pAN in the bulk (Supplementary Figure 27) and with reported peak assignments to the CC stretch of the aryl ring (νCC) with single-bond character and the CO stretch of the methoxy substituent (Supplementary Table 5)56. In contrast, the peak at 1604 cm−1 is blue-shifted by 6 cm−1 from that observed for bulk pAN (1598 cm−1, Supplementary Figure 27 and Supplementary Table 5), assigned to the νCC of the pAN aryl ring with double-bond character (shown in Figure 3b).56,57 This blueshift is also observed for SEIRA spectra collected in the absence of mCNBzCl (Supplementary Figures 28b and 29), ruling out any influence of mCNBzCl on the observed blueshift. As the blueshift is only observed when an electrified Ag surface is introduced, this result suggests a significant interaction of pAN with the polarized interface. This hypothesis is further supported by the omission of a signal at 1701 cm−1 expected for the carbonyl (νCO) stretching frequency of monomeric pAN56,58, which is observed for pAN in the bulk, Supplementary Figure 27, and not observed in the absence of pAN at identical applied potential values (Supplementary Figures 25b and 30). As SEIRAS is not sensitive to transition dipole moments parallel to the surface,50,51 the lack of an observed signal at 1701 cm−1 is consistent with an interfacial structure where monomeric pAN interacts with the Ag surface with C=O bonds predominately parallel59,60 to the electrode surface such that the phenyl moiety is in a tilted, “side-on”, conformation, Figure 4iii (insert). We observe that the addition of pAN is coincident with a redshift of the mCNBzCl nitrile stretch by 4 cm−1. The lack of Faradaic charge transfer at −1.03 V suggests that the observed redshift cannot be attributed to the presence of a reaction intermediate or product. Thus, we hypothesize that this shift is driven by the increased population of the surface-bound species, [mCNBzCl‒Ag]25,61 (Figure 4iii). Switching the applied potential to −2.23 V, where catalysis is observed (Figure 3b, black) results in a further redshift of the IR peak corresponding to the nitrile group, while the IR bands corresponding to pAN remain. The lack of potential-dependent shifts of the assigned pAN νCC aryl bands is consistent with minimal Stark tuning observed for aryl moieties adsorbed to electrode surfaces.55,62,63 The redshift in the nitrile feature is attributed to Stark tuning effects of the surface-bound moiety upon reductive polarization,55 however, we cannot rule out that possible surface organometallic intermediates61 contribute to the nitrile signal. Prolonged polarization at −2.23 V (Figure 3b, black) results in similar spectra, with a slowly increasing integrated band intensity associated with the integration of the nitrile feature (Supplementary Figure 31). Together, these spectroscopic data are consistent with an interfacial structural model in which both electrophiles interact with Ag prior to (−1.03 V) and during (−2.23 V) catalysis: the pAN accumulates at Ag in a predominately side-on mode, Figure 4ii, while mCNBzCl is activated via Ag-electrocatalyzed reduction, Figure 4iii, iv.

Figure 3. Spectroscopic data collected during Ag-electrocatalyzed electrophile coupling reactions.

Chronoamperometry traces (a, c) recorded on SEIRAS-active Ag film, where substrates and reagents were sequentially added at −1.03 V vs Fc/Fc+, indicated by blue (mCNBzCl), red (pAN), and (only for c) yellow (Mg(OAc)2) arrows. SEIRA spectra (b, d) collected simultaneously at −1.03 V before (grey) and after the sequential addition of Mg(OAc)2 (44 mM, orange, only in d), mCNBzCl (40 mM, blue), and pAN (40 mM, red), followed by spectra collected during electrolysis at −2.23 V at given times. Background spectra (grey, in b and d) collected in DMF containing 50 mM TBAClO4 on the same SEIRAS-active Ag film at −1.03 V before the addition of substrates or Mg(OAc)2. Red shaded region in b and d highlight major changes to the spectra associated with pAN normal modes for data collected in the absence and presence of Mg(OAc)2.

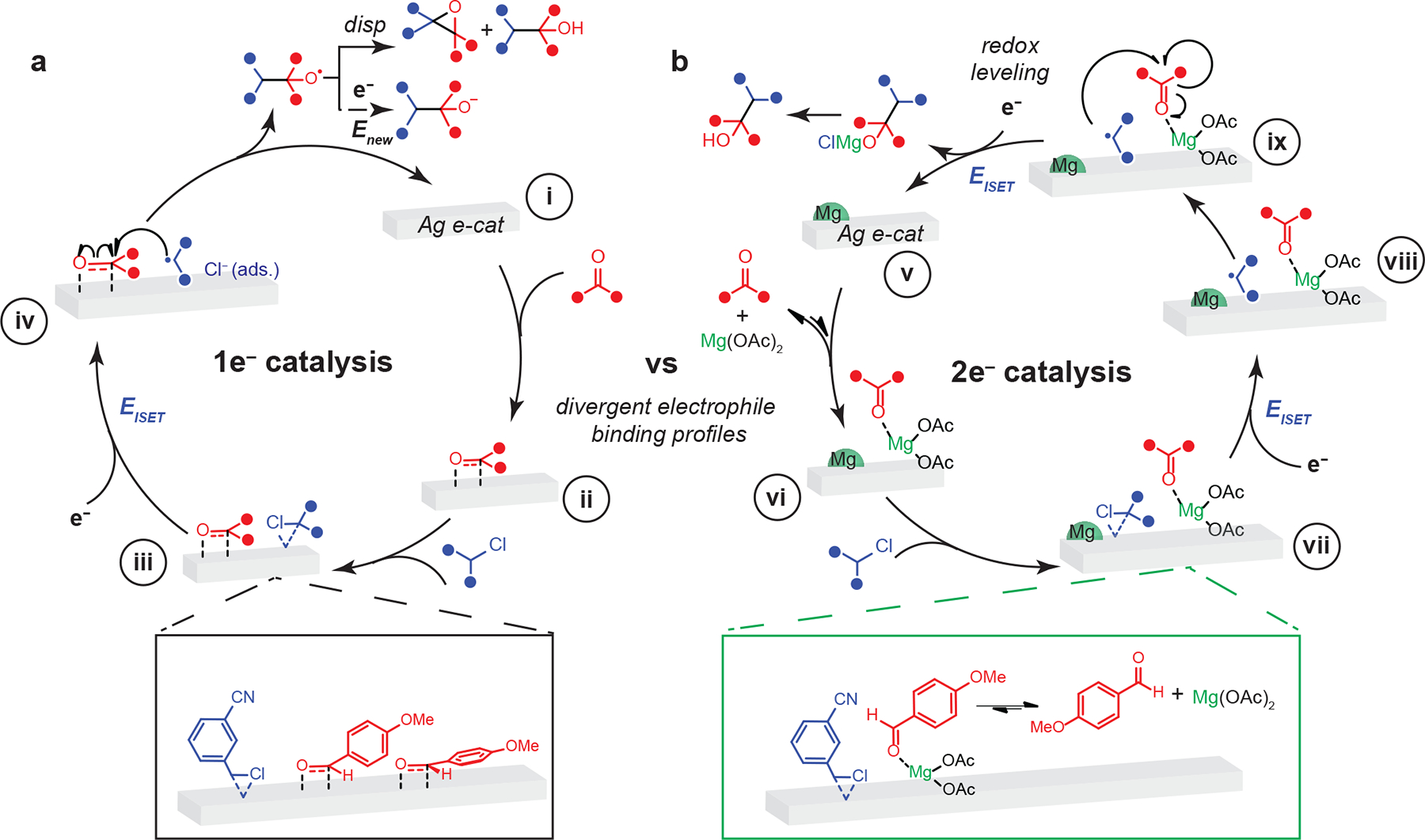

Figure 4. Summary of proposed mechanisms in the absence and presence of Mg(OAc)2.

Key mechanistic steps in the absence (a) and presence (b) of Mg(OAc)2 postulated via a combination of electroanalytical studies, simulation, reactivity observations, as well as in-situ spectroscopy are indicated with lower-case letter labels. Disp indicates disproportionation step. Black or green box indicates a zoom-in of the interfacial structure proposed in step iii or step vii. The Mg alkoxide salt is converted to the alcohol upon workup.

In the presence of Mg(OAc)2, the Lewis acid liberates the aldehyde electrophile interacting with the polarized Ag surface. Figure 3c and 3d depict the chronoamperometry trace and the associated SEIRA spectra of the polarized Ag surface in the presence of both electrophile partners and Mg(OAc)2. At −1.03 V, the addition of Mg(OAc)2 (Figures 3c and 3d, orange) leads to IR absorption bands at 1606, 1446, and 1416 cm−1, assigned to the CO asymmetric stretching, CH3 bending, and CO symmetric stretching modes, respectively.64 These observations indicate the accumulation of magnesium salts at the electrified interface (Supplementary Figures 32 and 33). The addition of mCNBzCl yields a distinct nitrile absorption at 2231 cm−1 (Figures 3c and 3d, blue, Supplementary Figure 25d), attributed to unbound mCNBzCl (Supplementary Figure 26). Interestingly, the addition of pAN leads to similar spectral changes for peaks associated with pAN, assigned above, but with the appearance of the C=O peak from monomeric pAN at 1701 cm−1,56,58 (Figure 3d, red shading) and weaker absorptions at 1022 cm−1, assigned to the CO stretch of the methoxy.56 This observation suggests an orientation of pAN at the Ag interface where, in contrast to that observed in the absence of Mg(OAc)2, the C=O is also perpendicular to the interface, Figure 4vii. In addition, the 6 cm−1 blueshift revealed for the νCC of the aryl ring in the absence of Mg(OAc)2 is no longer observed; instead, a peak identical to the bulk value is recovered (Figure 3b, Supplementary Figures 27 and 28b). The addition of pAN also results in a redshift of the nitrile peak from 2231 to 2226 cm−1, suggesting that the presence of pAN serves to enhance mCNBzCl binding. At −2.23 V, Figure 3d, green, we observe near-identical spectroscopic features to those observed at −1.03 V, however, the nitrile peak exhibits a further redshift. While the redshift in the nitrile feature can be attributed to Stark tuning effects of the surface-bound moiety upon reductive polarization,55 we cannot rule out the possibility that surface organometallic intermediates61 contribute to the signal. Prolonged polarization at −2.23 V (Figure 3d, black) results in similar spectra, with an increasing integrated band intensity associated with the integration of the nitrile feature (Supplementary Figure 31). Together, the spectroscopic data are consistent with a structural model in which Mg(OAc)2 tunes the Ag surface to outcompete the interaction between pAN and Ag, thereby increasing the interfacial population of free aldehyde at the interface, Figure 4.

Discussion

A mechanism consistent with our findings is summarized in Figure 4. In the absence of Mg(OAc)2, this scheme captures the side-on interaction of pAN to Ag, Figure 4i, ii, facilitating the binding of mCNBzCl, Figure 4iii. At EISET, 1 F mol−1 of organic chloride is passed, and the organic halide is reductively activated to form an alkyl radical intermediate, Figure 4iv. This radical adds into the aldehyde accumulated at Ag in a side-on mode to form an alkoxy radical intermediate. This intermediate disproportionates at a constant potential of EISET to yield the epoxide and the desired alcohol. Although the data do not provide evidence for the details of the disproportionation mechanism alone, the lack of detectable ketone in the reaction mixture (Figure 2a), rules out a predominant disproportionation pathway in which the α-H is abstracted. The lack of selective alcohol formation suggests that, under constant applied potential at EISET, the disproportionation rate outcompetes the second electron transfer. Examination of this scheme suggests that the poor selectivity observed in the absence of Mg(OAc)2 can be attributed to the lack of a suitable partner that levels out the two sequential electron transfers at EISET and Enew.

Mg(OAc)2 levels out the two sequential electron transfers. Figure 4vi captures the minor equilibrium binding of pAN to Mg(OAc)2, Figure 4vii. Subsequently, the reductive activation of the mCNBzCl is initiated at EISET to produce a carbon-centered radical, Figure 4viii. This alkyl radical intermediate adds into an aldehyde that is bound to Mg(OAc)2 in minor equilibrium, enabling the second electron transfer event to occur at a near-identical potential value of EISET, Figure 4ix. Thus, the liberation of the aldehyde accumulated at the Ag surface in a predominately side-on mode by Mg(OAc)2 enables this key redox-leveling effect to occur. Following, a Mg alkoxide salt is formed to produce an alcohol following workup. Figure 4vi also captures the observation of Mg0, which is not kinetically competent for the desired coupling reactivity.

In the bulk solution, our proposal is consistent with the widely recognized role of Mg2+ in enhancing the electrophilicity of aldehydes and ketones, leveraged to enable transformations such as hydroboration.46,65,66 These results help explain previous findings disclosing that Mg2+ salts accessed via sacrificial Mg anode dissolution increases the yield for select aldehyde/ketone functionalizations at non-catalytic electrodes.67,68 At the interface, however, our mechanistic proposal reveals the role of Mg(OAc)2. We observe that Mg(OAc)2 tunes the catalytic surface; in its absence, the aldehyde interacts with Ag in a predominately side-on mode, facilitating sequential one-electron transfers that limit reaction selectivity. With Mg(OAc)2, the minor equilibrium of pAN with Mg(OAc)2 as well as a significant interfacial population of Mg(OAc)2 outcompetes the proposed pAN-Ag binding, thereby enabling successful redox leveling of the two one-electron transfer events to occur at a single potential. These results highlight that the development of selective organic synthetic methods that utilize catalytic electrodes requires additives that direct competitive electrophile binding to the surface with multiple exposed binding sites.

In this work, we reveal the critical role of Mg(OAc)2 at catalytic Ag electrodes that facilitates selective product formation. This molecular- level framework enables access to a reductive catalytic method tolerant of sp3 organic chlorides to functionalize aldehydes and ketones. Figure 5 demonstrates that modest to high yields (32%−90%) of isolated products were obtained after the passage of 2 F mol−1 of the chloride substrate. Reactions were performed at a constant applied potential 200 mV more negative than the peak potential observed for the chloride (Figure 5, EISET). In heterogeneous electrocatalysis, the catalytic electrode is easily separable and capable of reuse without fouling.69 Indeed, the scope of the reaction was investigated with the same Ag electrode for nearly all substrates examined, demonstrating its reusability. The reusability is supported by the near-identical yield for 8 obtained using a fresh Ag (previously unused) and a reused Ag electrode after ~30 reactions. In addition, for 8, we demonstrate that the method is translatable to scale-up conditions using an undivided cell (Supplementary Figure 34). The reaction conditions are applicable to chlorides and aldehydes that contain a variety of heterocycles, including furan (12), thiophene (17 and 23), pyridine (11), pyrazole (10), and epoxide (20). The conditions are tolerant to nitriles (6, 12, 15–17, 19, 21–25) and esters (22, 28, 29); a property that would typically require control over reaction temperatures (< −40°C) to tolerate these functional groups using Grignard chemistry70,71. We note that the chloroalkyl cyanide substrate may operate via a resonance-stabilized anion intermediate and that we cannot discount competitive addition to the ester. The reaction is selective to the carbonyl over ester (22, 28,29), amide (27), or epoxide (20) functional groups. The conditions can be used with sterically hindered aldehydes (6, 13, 14)10 and those with select enolizable protons (13–16). The limitation with acidic functionality may be attributed to the known reductive chemistry accessible via surface-bound H on Ag.72,73 Ketones can also be used as an electrophilic partner in this transformation (25 and 26).

Figure 5. Investigated scope of the transformation.

All reactions were performed at room temperature in 3.5 mL DMF containing 40 mM chloride, 120 mM ketone/aldehyde, 44 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 50 mM TBAClO4 at a constant applied potential 200 mV more negative than the of the chloride substrate (values ranged from −2.0 to −2.8 V vs. Ag/Ag+). Reaction times ranged from 3 to 5 hours, until the current reached a value of −0.05 mA cm−2. All reported yields are isolated yields after chromatography on silica gel. Scale up details for 8 are provided in Methods.

Our reaction conditions allow us to expand the aldehyde scope of complementary electrosynthetic reactions that rely on non-catalytic carbon cathodes.19 In addition, the results show that the electrocatalytic process can access selective C(sp3)‒C(sp3) bonds from sp3 benzyl halides, where stoichiometric Grignard reactions would lead to parasitic Wurtz homocoupling.12 This discovery provides a catalytic route compatible with sp3 organic halide electrophiles (see Supplementary Table 6 for comparison) that is complementary to the catalytic reductive coupling methodology for sp2 or sp organic halides with ketones and aldehydes that employ stoichiometric reductants.10,11 Importantly, our catalytic method development is guided by mechanistic and structural insights from electroanalysis and in-situ spectroscopy revealing the critical role of Mg(OAc)2 in directing competitive electrophile binding. Thus, at a fundamental level, these studies lay a foundation to expose organic electrosynthetic reaction paradigms by tuning the interfacial structure at catalytic, reusable electrodes at the molecular level.

Methods

General Methods.

Reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Dimethylformamide (DMF) was dried and purified using a solvent purification system (PureSolv MD 5, INERT Corporation) under N2. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of reaction mixtures were performed using Merck silica gel 60 F254 TLC plates and visualized using iodine, KMnO4 stain, p-anisaldehyde stain, or UV. Column chromatography and preparative TLC was carried out using Mackerey-Nagel Silica Gel 60 Å, 0.04 × 0.063 mm or Merck silica gel 60 F254 TLC plates, respectively. 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR experiments were conducted using Bruker Ultrashield 400 Plus or 500 Plus instruments. Peaks were referenced using residual solvent peaks or added internal standards. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained on an Agilent 6224 TOF-MS spectrometer and were reported for molecular ions [M]+, [M+Na]+, or [M+H]+. For NMR spectra and HRMS of the compounds in this article, see Supplementary Figures 35–143. Gas chromatography mass spectrometry (EI ionization, Agilent Tech HP-5Å MS, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm column) was conducted using an Agilent 5975 Series MSD, Hewlett Packard 7683 Series injector, and Agilent 6890 series GC instrument, DMF and THF, as the solvents.

Electrolyte Preparation.

Anhydrous 0.05 M TBAClO4 electrolyte in DMF was prepared by drying the recrystallized TBAClO4 salt under vacuum overnight at 60°C, then dissolving the salt in anhydrous DMF (Sigma Aldrich, 99.8%), and then storing over freshly activated molecular sieves (3 Å, Supelco) in a N2-filled glovebox. Immediately prior to use, the electrolyte was filtered through a 0.22 μm frit. By Karl Fisher titration, the electrolyte contained 15–18 ppm of water. Anhydrous 0.05 M TBAClO4 electrolyte containing Mg(OAc)2 was prepared in a similar manner with the following modifications. Mg(OAc)2•4H2O (Sigma Aldrich, >99%) was dried under vacuum overnight at 60 °C. Electrolyte containing Mg(OAc)2 could be stored over molecular sieves for a total of 48 hours before the Mg2+ concentration was significantly altered. Thus, the electrolyte containing Mg(OAc)2 was dried overnight, filtered, and used immediately. By Karl Fisher titration, the electrolyte containing Mg(OAc)2 contained 15–18 ppm of water. Similar manipulations were performed to screen other Mg2+-based electrolytes (Mg(ClO4)2, Mg(OTf)2, MgBr2, and MgCl2) investigated in this work.

Electrochemical Methods.

All cyclic voltammetry experiments were conducted in an N2-filled glovebox. Electrochemical experiments were conducted using a Biologic VSP Potentiostat or a Gamry Reference 600+ Potentiostat, a Ag/Ag+ reference electrode (BASi, 10 mM AgBF4 in 0.05 M TBAClO4 in DMF, Fc/Fc+ at 0.026 V vs Ag/Ag+), a high surface area Pt-mesh counter electrode (Alfa Aesar, 99.997 %), and a glassy carbon (BASi, 3 mm diameter) or Ag (BASi, 2mm diameter) working electrode. Working electrodes were polished (alumina slurry with Millipore Type 1, 18.2 MΩ, water) and dried prior to experiments. The Ag/Ag+ electrode was stored in DMF between measurements and was periodically checked relative to Fc/Fc+ to ensure against potential drift. All experiments were performed at 24±1 °C. Electrode potentials were converted to the Fc/Fc+ standard using the conversion, EFc/Fc+ = EAg/Ag+ − 0.026 V. For each experiment utilizing the Biologic VSP Potentiostat, an initial starting point for the uncompensated Ohmic loss was measured using the Precise Function in the EC-Lab Biologic software workstation Version 11.41 (~500–600 Ω). This initial value was further corrected by collecting sequential cyclic voltammograms with increasing Ru values until oscillations corresponding to total compensation were observed.74 This corrected Ru value (Rcorr) was approximately 200–800 Ω higher than the initial value measured using the Ru test function, i.e. 800–1300 Ω. This Rcorr was inputted manually into the iR compensation menu in the EC-Lab Biologic software workstation Version 11.41. Current density values are reported relative to the geometric surface area of the working electrode. A three-compartment electrochemical cell was utilized and held 3.5 mL of electrolyte in the working compartment and counter compartments (James Glass Inc.) The compartments were separated by an ultra-fine glass frit (P5, Adams and Chittenden). For data collected in Figure 2b, we note that only the first CV were reported on a freshly polished Ag electrode.

Bulk Electrolysis Procedures.

Bulk electrolysis experiments were performed in an N2-filled glovebox. Experiments were conducted using a Biologic VSP potentiostat, a non-aqueous Ag/Ag+ reference electrode (BASi, 10 mM AgBF4 in 0.05 M TBAClO4 in DMF, Fc/Fc+ at 0.026 V vs Ag/Ag+), a high surface area Pt-mesh counter electrode (Alfa Aesar, 99.997 %), and a Ag mesh working electrode (1 cm2 surface area, 99.9%, Alfa Aesar), attached to a stainless steel rod by threading through Ag wire of 99.9% purity. For every experiment, the Ag mesh electrode was cleaned by 30-minute H2SO4 immersion, 30-minute sonication in NaHCO3 slurry, followed by sequential washing with water and acetone. The Ag/Ag+ electrode was stored in DMF between measurements and was periodically checked relative to Fc/Fc+ to ensure against potential drift. Electrode potentials were converted to the Fc/Fc+ standard using the conversion, EFc/Fc+ = EAg/AgCl − 0.026 V. All experiments were performed at 24±1 °C. A three-compartment electrochemical cell was utilized and held 3.5 mL of electrolyte in the working compartment and counter compartments (James Glass Inc.) The compartments were separated by an ultra-fine glass frit (P5, Adams and Chittenden). Organic halides (40 mM) and aldehydes/ketones (120 mM) were added to the cathode side containing 44 mM Mg(OAc)2 and 50 mM TBAClO4 in 3.5 mL of DMF. Prior to each experiment, a cyclic voltammogram of the chloride substrate was taken in the presence and absence of aldehyde or ketone using a Ag disk stationary working electrode (BASi, 2 mm diameter, polished outside the glovebox with alumina slurry with Millipore Type 1, 18.2 MΩ, water) to verify the potential of Ag-catalyzed substrate reduction. The working electrode was switched to the Ag mesh, and a chronoamperometry trace was initiated at a potential value 200-mV more negative than the peak potential of the catalyzed reduction determined by cyclic voltammetry. During the bulk electrolysis, the working and counter compartments were continuously stirred (~350 rpm). After the current value reached the background value (~ −0.05 mA), the chronoamperometry experiment was terminated. Consumption of the chloride substrates was confirmed by switching the working electrode to the Ag disk stationary working electrode. The catholyte was quenched with 1M NH4Cl solution, and the Ag mesh electrode was rinsed with diethyl ether. For determining GCMS yields, 5 mM of decane (THF) internal standard was added prior to the liquid injection. For determining isolated yields, the organic products were extracted with diethyl ether (3x). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine (3x) and water (1x), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Products listed below were isolated on silica gel by preparative thin layer chromatography or by column chromatography. Weighed isolated yields were determined.

Surface-Enhanced Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy (SEIRAS).

SEIRA spectra were recorded in an attenuated total reflection (ATR) configuration using a Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer equipped with a HgCdTe (MCT) detector (Ref/2x Gain Setting) and a PIKE VeeMax III accessory (incident angle of 60°). The Nicolet spectrometer was operated in the Series mode with an optical velocity of 1.898 cm s−1. Spectra were sequentially acquired with a spectral resolution of 4 cm–1 at every 25.13 s interval. A single beam spectrum collected at the starting potential in the absence of any substrates (i.e., in the presence of 0.05 M TBAClO4 in DMF) was used as the reference spectrum. All ATR-SEIRA spectra are reported in absorbance units defined as A=−log (I/I0), where I and I0 stand for the sample and reference single-beam spectra, respectively. Data analyses were conducted using the OMNIC version 9.12.928 software. The PIKE Jackfish J2 spectroelectrochemical cells were used, equipped with a SEIRAS-active Ag film as the working electrode, a Pt wire counter electrode and a non-aqueous Ag/Ag+ reference electrode. They were assembled inside a N2-filled glovebox, sealed after the addition of 11 mL DMF containing 50 mM TBAClO4, and then taken out prior to the SEIRAS measurements. Reference spectra (Supplementary Figures 26, 27, and 33) collected in the absence of a Ag film on top of the Si, i.e., only using bare Si prism, used the same spectroscopic setup. During a constant applied potential of −1.03 V vs. Fc/Fc+, concentrated solutions of Mg(OAc)2, and/or mCNBzCl and pAN were injected sequentially by syringe needles under N2 flow. Following, the applied potential was switched to −2.23 V.

Preparation of Ag Films for SEIRAS.

Au films were prepared on Si prisms (PIKE, 0.71 cm2 surface area) using the “double deposition method” as previously detailed.52,53,75 Following the deposition, the Au-coated Si prism was assembled into the PIKE Jackfish J2 spectroelectrochemical cell, and cleaned using an electrochemical procedure. The Au film was cycled in 0.1 M H2SO4 from 0 V vs Ag/AgCl to 1.5 V vs Ag/AgCl at 50 mV s−1 for 10 continuous cycles without pause. Following, the 0.1 M H2SO4 was replaced with 0.1 M H2SO4 containing 2 mM Ag2SO4 and degassed for 10 min with continuous N2 sparging. Then, chronoamperometry traces were conducted using the following sequence. First, 0.3 V vs Ag/AgCl was applied for 300 s twice (for a total of 600 s). Second, 0.25 V vs Ag/AgCl was applied for 300 s once (for a total of 300 s). This deposition procedure resulted in a film that looked like a sheen Ag layer by eye. Following, the film was washed with MilliQ, followed by ethanol. Then, the film was dried for 30 min under a continuous stream of N2 and cycled into the glovebox. Four separate independent but identical preparations of SEIRAS-active Ag films are reported: Film I was used to collect data shown in Figures 3a and 3b, and Supplementary Figures 25a and 25b, Film II was used to collect data shown in Supplementary Figures 28a, 28b, and 29. Film III was used to collect data shown in Figure 3d, and Supplementary Figures 25 and 25d, and Film IV was used to collect data shown in Supplementary Figures 28c, 28d, and 32. The background spectra for these four independent films in the absence of substrates but in the presence of DMF and 0.05 M TBAP are reported in Supplementary Figure 30. These data are collected after at least one 2 mV s−1 scan cycle between −1.03 and −2.23 V vs Fc/Fc+ and subsequent background collection at −1.03 V vs Fc/Fc+. In our hands, other reported SEIRAS-active Ag deposition procedures that do not have an Au underlayer76 resulted in Ag film leading to abnormal IR peaks.

Electrochemical Simulation.

Electrochemical simulations were carried out using KISSA-1D, Version 1.2 by BASi. Cyclic voltammetry simulations were conducted assuming a planar electrode geometry of a surface area 0.03 cm2, with natural convection turned on using δ=150 μm. Simulated scans were collected from −1.0 to −3.0 V with various experimentally relevant scan rates (0.1, 0.5, and 1 V s−1), with pre-equilibrium functions turned off.

Determination of the Dimerization Rate Constant for pAN.

Simulation methods were used to construct working curves used to evaluate the rate of radical-radical dimerization for pAN. The inputs to the simulation were determined assuming the following mechanistic scheme.45,77,78

| (1) |

| (2) |

where A is pAN, B is the product of single electron transfer (i.e., ketyl radical anion), and C is the dimerized product (i.e., pinacol), see also Supplementary Figure 12b. Equation 1 was designated as an outer-sphere, reversible charge-transfer reaction with Butler-Volmer kinetics assuming the transfer coefficient α=0.5, rate constant ks=0.005 cm s−1,79 and standard reduction potential E0= −2.2 V. Equation 2 was designated as an irreversible addition reaction with rate constant kd. Diffusion constants of species A, B and C in solution were taken from the diffusion constants of species of the same mass in DMF, where DA=DB=4.2×10−6 cm2 s−1,80 and DC=1.9×10−6 cm2 s−1.81 A collection of cyclic voltammograms was simulated for various experimentally relevant initial concentrations of A (20 mM, 40 mM, 80 mM, and 120 mM), with the initial concentrations of B and C set to 0 mM, in which kd was systematically altered from 3.892×10−5 to 3.892×104 M−1 s−1 by powers of 10 to adjust the dimensionless kinetic parameter,78,82,83

| (3) |

where [A0] is the initial concentration of A, ν is the scan rate (which was simulated for experimentally relevant scan rates 0.1, 0.5, and 1 V s−1), T is the temperature (298.15 K), F is Faraday’s constant, and R is the universal gas constant. To construct the working curves, the peak reductive current and peak oxidative current were extracted from the simulated cyclic voltammograms, and the peak current ratio (of peak oxidative current to peak reductive current, ipa/ipc) was plotted against log(λ) (Supplementary Figure 12a). The resulting working curve was then used to estimate the rate of dimerization, kd, for experimentally determined (Supplementary Figures 13 and 14) peak current ratios of varying experimental conditions ([A0], ν), the results of which are given in Supplementary Table 3.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy.

X-ray photoelectron spectra were collected on an as-prepared SEIRAS-active Ag film, a fresh Ag foil, and on a Ag foil following bulk electrolysis at −2.23 V vs. Fc/Fc+ in the presence of 120 mM pAN and 40 mM m-cyanobenzyl chloride in 0.05 M TBAClO4 in DMF containing 44 mM Mg(OAc)2. In the latter case, the working electrode was removed from the electrochemical cell while under polarization, and rinsed thoroughly with DMF. It was loaded on the sample stage in a N2-filled glovebox and transferred to the ultra-high vacuum chamber protected by an N2-filled bag. XPS samples were prepared by adhering the electrodes to the sample stage with copper foil. The X-ray photoelectron spectra were collected using an AXIS Nova spectrometer (Kratos Analytical) equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source. The Al anode was powered at 10 mA and 15 kV. The instrument work function was calibrated to give a Au 4f7/2 metallic gold binding energy of 83.95 eV. The instrument base pressure was ca. 1 × 10−8 Torr. The analysis area size was 0.3 × 0.7 mm2. For calibration purposes, the binding energies were referenced to the C 1s peak at 284.8 eV. Survey spectra were collected with a 160-eV pass energy and a step size of 1 eV. The high-resolution spectra were collected with a pass energy of 20 eV and a 0.1 eV step size. The survey spectrum of the Ag film used for SEIRA studies was obtained by Kratos AXIS-165 XPS equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα x-ray source. Survey spectra were collected with a 20-eV pass energy and a step size of 0.5 eV.

Scale-Up Demonstration.

A solution of 40 mL DMF containing 80 mM Mg(OAc)2, TBAOAc (160 mM), and TBAClO4 (50 mM) was dried over molecular sieve and Mg(OH)2 (ca. 200 mg) overnight. Both the Mg foam (1 × 4 × 0.1 cm, Thermo Scientific Chemicals) and Ag foil (1 × 4 cm, Thermo Scientific Chemicals) were carefully polished shortly before use. The dry DMF solution, 75 mM chlorodiphenylmethane and 225 mM pAN were added to an oven-dried test tube equipped with a stir bar. The electrodes were connected to the potentiostat via silver wires separately through a rubber septum. The cell was sealed using tape and grease in glovebox, followed by insertion of an N2 balloon immediately after transfer to regular fume hood. The current was set to −22 mA. The reaction mixture was stirred (circa 1000 rpm) at room temperature for 11 hours. Upon the completion of the reaction, 0.1 M NH4Cl solution was added, and the reaction mixture is diluted with 200 mL of brine. After extraction by Et2O (2 × 200 mL), the organic layers were combined and further washed by brine and water, followed by drying over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed by evaporation before separation by silica chromatography (0–15% EtOAc in n-hexane) to obtain the desired product (61%, 540 mg).

Preparation of Probe Compound.

To prepare 3-(2-((1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)oxy)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)benzonitrile, a solution of 3-(2-hydroxy-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)benzonitrile (10 mg, 0.025 mmol), PPh3 (7.8 mg, 0.03 mmol), and N-hydroxyphthalimide (4.9 mg, 0.03 mmol) in THF (0.075 mL) was added diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (6.25 uL in three portions, 0.03 mmol) over 10 min at −20 °C. The resulting mixture was stirred for 24 hours at room temperature, taken up in ethyl acetate (2 mL), and washed with saturated NaHCO3 (3 × 2 mL) and brine (2 × 2 mL). The organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo, and subjected to chromatography (MeOH : DCM : Et2O : n-hexane = 1:2:2:5) to yield a pale yellow oil (51%).

Preparation of Pb Disk Electrode.

We prepared the Pb disk electrode following a previously reported method.84 We find that this electrode displays oxide features characteristic of Pb in H2SO485, in contrast to a clean Au disk electrode.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the research laboratories of Professors John Anderson, Guangbin Dong, Scott Snyder, Viresh Rawal, Chibueze Amanchukwu, and Michael Hopkins for sharing their chemical inventories. We thank Professor Andrei Tokmakoff for helpful discussions on spectroscopic data. We thank Dr. Alexander Filatov, Professor Ksenija Glusac, and Biki Behera for assistance with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy data collection at the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago, respectively. We thank Dr. Josh Kurutz for assistance with nuclear magnetic resonance data collection at the University of Chicago. This research made use of the University of Chicago Mass Spectrometry Facility (NSF instrumentation grant CHE-1048528). This research was partially supported by the University of Chicago startup funds and a James R. Norris, Jr. fellowship to S.K. (University of Chicago, Department of Chemistry). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number 1R35GM150845.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the article (and its Supplementary Information) or available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Lovering F, Bikker J & Humblet C Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem 52, 6752–6756 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huffman BJ et al. Electronic complementarity permits hindered butenolide heterodimerization and discovery of novel cGAS/STING pathway antagonists. Nat. Chem 12, 310–317 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei W, Cherukupalli S, Jing L, Liu X & Zhan P Fsp3: a new parameter for drug-likeness. Drug Discov. Today 25, 1839–1845 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rappoport Z & Marek I The Chemistry of Organomagnesium Compounds. (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu G & Huang M Organolithium reagents in pharmaceutical asymmetric processes. Chem. Rev 106, 2596–2616 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider N, Lowe DM, Sayle RA, Tarselli MA & Landrum GA Big data from pharmaceutical patents: a computational analysis of medicinal chemists bread and butter. J. Med. Chem 59, 4385–4402 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicolaou KC, Ellery SP & Chen J Samarium diiodide mediated reactions in total synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 48, 7140–7165 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szostak M, Fazakerley NJ, Parmar D & Procter DJ Cross-coupling reactions using samarium(II) iodide. Chem. Rev 114, 5959–6039 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gil A, Albericio F & Álvarez M Role of the Nozaki-Hiyama-Takai-Kishi reaction in the synthesis of natural products. Chem. Rev 117, 8420–8446 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia KJ, Gilbert MM & Weix DJ Nickel-catalyzed addition of aryl bromides to aldehydes to form hindered secondary alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 1823–1827 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swyka RA, Zhang W, Richardson J, Ruble JC & Krische MJ Rhodium-catalyzed aldehyde arylation via formate-mediated transfer hydrogenation: beyond metallic reductants in Grignard/Nozaki-Hiyami-Kishi-type addition. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 1828–1832 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadam A et al. Comparative performance evaluation and systematic screening of solvents in a range of Grignard reactions. Green Chem. 15, 1880–1888 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curran DP, Diederichsen U & Palovich M Radical cyclizations of acylgermanes. New reagent equivalents of the carbonyl radical acceptor synthon. J. Am. Chem. Soc 119, 4797–4804 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilsey S, Dowd P & Houk KN Effect of alkyl substituents and ring size on alkoxy radical cleavage reactions. J. Org. Chem 64, 8801–8811 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salamone M & Bietti M Reaction pathways of alkoxyl radicals. The role of solvent effects on C–C bond fragmentation and hydrogen atom transfer reactions. Synlett 25, 1803–1816 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crabtree RH Insertion and Elimination. in The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals 185–203 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W & Lin S Electroreductive carbofunctionalization of alkenes with alkyl bromides via a radical-polar crossover mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 142, 20661–20670 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang W et al. Electrochemically driven cross-electrophile coupling of alkyl halides. Nature 604, 292–297 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu H et al. Cathodic carbonyl alkylation of aryl ketones or aldehydes with unactivated alkyl halides. Org. Lett 24, 9342–9347 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth H, Romero N & Nicewicz D Experimental and calculated electrochemical potentials of common organic molecules for applications to single-electron redox chemistry. Synlett 27, 714–723 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao Y et al. Electrochemical Nozaki-Hiyama-Kishi coupling: scope, applications, and mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 143, 9478–9488 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rondinini S, Mussini PR, Muttini P & Sello G Silver as a powerful electrocatalyst for organic halide reduction: the critical role of molecular structure. Electrochim. Acta 46, 3245–3258 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isse AA, De Giusti A, Gennaro A, Falciola L & Mussini PR Electrochemical reduction of benzyl halides at a silver electrode. Electrochim. Acta 51, 4956–4964 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isse AA, Gottardello S, Durante C & Gennaro A Dissociative electron transfer to organic chlorides: electrocatalysis at metal cathodes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 10, 2409–2416 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang YF et al. Bridging the gap between electrochemical and organometallic activation: benzyl chloride reduction at silver cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 17199–17210 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strawsine LM, Mubarak MS & Peters DG Use of silver cathodes to promote the direct reduction and intramolecular cyclization of ω-halo-1-phenyl-1-alkynes in dimethylformamide. J. Electrochem. Soc 160, G3030–G3037 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klymenko OV et al. Uncovering the missing link between molecular electrochemistry and electrocatalysis: mechanism of the reduction of benzyl chloride at silver cathodes. ChemElectroChem 1, 227–240 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strawsine LM, Sengupta A, Raghavachari K & Peters DG Direct reduction of alkyl monohalides at silver in dimethylformamide: effects of position and identity of the halogen. ChemElectroChem 2, 726–736 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartwig JF Oxidative Addition of Polar Reagents. in Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis. 301–320 (University Science Books, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diccianni JB, Katigbak J, Hu C & Diao T Mechanistic characterization of (xantphos)Ni(I)-mediated alkyl bromide activation: oxidative addition, electron transfer, or halogen-atom abstraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 1788–1796 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandford C, Fries LR, Ball TE, Minteer SD & Sigman MS Mechanistic studies into the oxidative addition of Co(I) complexes: combining electroanalytical techniques with parameterization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 18877–18889 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu DF et al. Electrocatalytic carboxylation of aliphatic halides at silver cathode in acetonitrile. Tetrahedron 64, 10517–10520 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medvedev JJ, Medvedeva XV, Engelhardt H & Klinkova A Relative activity of metal cathodes towards electroorganic coupling of CO2 with benzylic halides. Electrochim. Acta 387, 138528 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corbin N, Yang DT, Lazouski N, Steinberg K & Manthiram K Suppressing carboxylate nucleophilicity with inorganic salts enables selective electrocarboxylation without sacrificial anodes. Chem. Sci 12, 12365–12376 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harwood SJ et al. Modular terpene synthesis enabled by mild electrochemical couplings. Science 375, 745–752 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palkowitz MD et al. Overcoming limitations in decarboxylative arylation via Ag-Ni electrocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 144, 17709–17720 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foresti ML, Innocenti M, Forni F & Guidelli R Electrosorption valency and partial charge transfer in halide and sulfide adsorption on Ag(111). Langmuir 14, 7008–7016 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isse AA & Gennaro A Electrocatalytic carboxylation of benzyl chlorides at silver cathodes in acetonitrile. Chem. Commun 2798–2799 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isse AA et al. Electrocatalysis and electron transfer mechanisms in the reduction of organic halides at Ag. J. Appl. Electrochem 39, 2217–2225 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isse AA, Mussini PR & Gennaro A New insights into electrocatalysis and dissociative electron transfer mechanisms: the case of aromatic bromides. J. Phys. Chem C 113, 14983–14992 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Syroeshkin MA et al. Electrochemical behavior of N-oxyphthalimides: cascades initiating self-sustaining catalytic reductive N ― O bond cleavage. J. Phys. Org. Chem 30, e3744 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Douch J & Mousset G Electrochemical reduction of carbonyl compounds in non-aqueous solvent in the presence of EuCl3·6H2O. Can. J. Chem 65, 549–556 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ischay MA, Anzovino ME, Du J & Yoon TP Efficient visible light photocatalysis of [2+2] enone cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 130, 12886–12887 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fournier F & Fournier M Transferts d’électrons assistés par les métaux de transition:influence de la nature du cation métallique sur la réduction de composés carbonylés en milieu aprotique. Can. J. Chem 64, 881–890 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrieux CP, Grzeszczuk M & Savéant J-M Electrochemical generation and detection of transient intermediates: dimerizing species. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem 318, 369–372 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vasilenko V, Blasius CK, Wadepohl H, Gade LH & Li R Borohydride intermediates pave the way for magnesium-catalysed enantioselective ketone reduction. Chem. Commun 56, 1203–1206 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reetz MT, Harmat N & Mahrwald R Ligand effects in Grignard additions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 31, 342–344 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fournier V, Marcus P & Olefjord I Oxidation of magnesium. Surf. Interface Anal 34, 494–497 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hou S et al. Solvation sheath reorganization enables divalent metal batteries with fast interfacial charge transfer kinetics. Science 374, 172–178 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osawa M Dynamic processes in electrochemical reactions studied by surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS). Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 70, 2861–2880 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osawa M In-situ surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy of the electrode/solution interface. in Diffraction and Spectroscopic Methods in Electrochemistry (Advances in Electrochemical Science and Engineering, Vol.9) (eds. Alkire RC, Kolb DM, Lipkowski J & Ross PN) 269–314 (Wiley-VCH, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyake H, Ye S & Osawa M Electroless deposition of gold thin films on silicon for surface-enhanced infrared spectroelectrochemistry. Electrochem. Commun 4, 973–977 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yaguchi M, Uchida T, Motobayashi K & Osawa M Speciation of adsorbed phosphate at gold electrodes: a combined surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy and DFT study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 7, 3097–3102 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ros R, Leenarda M, Boschi T & Roulet R Cyanobenzylpalladium(H) complexes. Synthesis and spectroscopic properties. Inorganica Chim. Acta 25, 61–64 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delley MF, Nichols EM & Mayer JM Interfacial acid-base equilibria and electric fields concurrently probed by in situ surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 143, 10778–10792 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuş N, Sharma A, Reva I, Lapinski L & Fausto R Thermal and photoinduced control of relative populations of 4-methoxybenzaldehyde (p-anisaldehyde) conformers. J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 7716–7724 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gunasekaran S, Seshadri S, Muthu S, Kumaresan S & Arunbalaji R Vibrational spectroscopy investigation using ab initio and density functional theory on p-anisaldehyde. Spectrochim. Acta A 70, 550–556 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fathima AA, Umadevi M & Ramakrishnan V Changes in spectral features with varying mole fractions of anisaldehyde in binary mixtures. J. Raman Spectrosc 38, 271–276 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bron M et al. Bridging the pressure and materials gap: in-depth characterisation and reaction studies of silver-catalysed acrolein hydrogenation. J. Catal 234, 37–47 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang K & Yang B Theoretical understanding on the selectivity of acrolein hydrogenation over silver surfaces: the non-Horiuti–Polanyi mechanism is the key. Catal. Sci. Technol 7, 4024–4033 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang A et al. In situ identification of intermediates of benzyl chloride reduction at a silver electrode by SERS coupled with DFT calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 9534–9536 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao P & Weaver MJ Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy as a probe of adsorbate-surface bonding: benzene and monosubstituted benzenes adsorbed at gold electrodes. J. Phys. Chem 89, 5040–5046 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cai W. Bin et al. Orientational phase transition in a pyridine adlayer on gold(111) in aqueous solution studied by in situ infrared spectroscopy and scanning tunneling microscopy. Langmuir 14, 6992–6998 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pang SF, Wu CQ, Zhang QN & Zhang YH The structural evolution of magnesium acetate complex in aerosols by FTIR–ATR spectra. J. Mol. Struct 1087, 46–50 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Revunova K & Nikonov GI Main group catalysed reduction of unsaturated bonds. Dalt. Trans 44, 840–866 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Falconnet A, Magre M, Maity B, Cavallo L & Rueping M Asymmetric magnesium-catalyzed hydroboration by metal‐ligand cooperative catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 58, 17567–17571 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chaussard J et al. Use of sacrificial anodes in electrochemical functionalization of organic halides. Synthesis 1990, 369–381 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klein M & Waldvogel SR Counter electrode reactions—important stumbling blocks on the way to a working electro-organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 61, e202204140 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Novaes LFT et al. Electrocatalysis as an enabling technology for organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 50, 7941–8002 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boymond L, Rottländer M, Rard Cahiez GÂ & Knochel P Preparation of highly functionalized Grignard reagents by an iodine—magnesium exchange reaction and its application in solid-phase synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 37, 1701–1703 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee JS, Velarde-Ortiz R, Guijarro A, Wurst JR & Rieke RD Low-temperature formation of functionalized Grignard reagents from direct oxidative addition of active magnesium to aryl bromides. J. Org. Chem 65, 5428–5430 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shimizu KI, Sato R & Satsuma A Direct C-C cross-coupling of secondary and primary alcohols catalyzed by a γ-alumina-supported silver subnanocluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 48, 3982–3986 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Varshney S, Bar-Ziv R & Zidki T On the remarkable performance of silver-based alloy nanoparticles in 4-nitrophenol catalytic reduction. ChemCatChem 12, 4680–4688 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Savéant J-M & Costentin C Elements of Molecular and Biomolecular Electrochemistry: An Electrochemical Approach to Electron Transfer Chemistry. (John Wiley & Sons, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wuttig A, Ryu J & Surendranath Y Electrolyte competition controls surface binding of CO intermediates to CO2 reduction catalysts. J. Phys. Chem C 125, 17042–17050 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huo SJ, Xue XK, Li QX, Xu SF & Cai W Bin. Seeded-growth approach to fabrication of silver nanoparticle films on silicon for electrochemical ATR surface-enhanced IR absorption spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 25721–25728 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Savéant J-M & Vianello E Potential-sweep voltammetry: theoretical analysis of monomerization and dimerization mechanisms. Electrochim. Acta 12, 1545–1561 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Savéant J-M & Costentin C Coupling of electrode electron transfers with homogeneous chemical reactions. in Elements of Molecular and Bimolecular Electrochemistry 81–181 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsierkezos NG Investigation of the electrochemical reduction of benzophenone in aprotic solvents using the method of cyclic voltammetry. J. Solution Chem 36, 1301–1310 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang R et al. Catalytic reduction of O2 by pyrazine derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. A 108, 1891–1899 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marouani S, Louati A & Gross M Influence du solvant sur la reduction electrochimique du nitrate et de l’acetate d’uranyle. Electrochim. Acta 33, 147–155 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Savéant J-M & Vianello E Étude de la polarisation chimique en régime de variation linéaire du potentiel. Cas d’une désactivation spontanée, rapide et irréversible du produit de la réduction. C. R. Acad. Sci 256, 2597–2600 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Savéant J-M & Vianello E Potential-sweep voltammetry: general theory of chemical polarization. Electrochim. Acta 12, 629–646 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hall AS, Yoon Y, Wuttig A & Surendranath Y Mesostructure-induced selectivity in CO2 reduction catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 14834–14837 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Visscher W Cyclic voltammetry on lead electrodes in sulphuric acid solution. J. Power Sources 1, 257–266 (1976). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the article (and its Supplementary Information) or available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.