Abstract

We experimentally vary signals and senders to identify which combination will increase vaccine demand among a disadvantaged population in the United States—Black and White men without a college education. Our main finding is that laypeople (nonexpert concordant senders) are most effective at promoting vaccination, particularly among those least willing to become vaccinated. This finding points to a trade-off between the higher qualifications of experts on the one hand and the lower social proximity to low-socioeconomic-status populations on the other hand, which may undermine credibility in settings of low trust.

Preventive health investments can yield considerable benefits for individuals and society, yet are often adopted at low rates (see Newhouse 2021). Immunization against infectious diseases is a leading example of a measure that improves health and reduces employee absenteeism (CDC 2020; Nichol, Mallon, and Mendelman 2003).1 However, despite near-universal recommendation of the seasonal influenza vaccine for individuals over the age of six months in the United States and federally mandated zero cost-sharing under the Affordable Care Act, take-up rates among adults average only 45 percent (CMS 2010; CDC 2021a). Take-up rates are particularly low among certain demographic groups, such as men, individuals without a four-year college degree, and non-Hispanic Black Americans (see panel A of online Appendix Figure 1; CDC 2017; Newhouse 1993).

Among the groups with the lowest vaccination rates, the reasons frequently reported for not taking up flu vaccines relate to pessimistic views on the benefits or nonpecuniary costs of vaccinations, as opposed to financial costs or lack of recommendation by a health professional.2 These findings echo prior research on higher levels of medical mistrust among Black Americans as well as among individuals with less education (Blendon, Benson, and Hero 2014; Kinlock et al. 2017; Nanna et al. 2018; Hammond et al. 2010; Idan et al. 2020). This mistrust likely has deep historical roots, including the government-led experiment in Tuskegee, Alabama, as well as contemporaneous racism in medicine (Alsan and Wanamaker 2018; Bajaj and Stanford 2021; Brandt 1978). The findings on beliefs also relate to growing scholarship on misperceptions in the net benefits of preventive care (i.e., behavioral hazard) leading to underutilization (Handel and Kolstad 2015; Bhargava, Loewenstein, and Benartzi 2017; Ericson and Sydnor 2017; Brot-Goldberg et al. 2017; Handel and Schwartzstein 2018; Chandra, Flack, and Obermeyer 2023). There is scope, then, to change individuals’ views on vaccination through the provision of credible and accurate information (Kamenica and Gentzkow 2011).

In this study, we aim to evaluate the effectiveness of messaging interventions designed to shift knowledge, beliefs, and take-up behavior regarding vaccines among populations with low socioeconomic status (SES). We randomly assigned respondents recruited online to one of four video messages with information about flu vaccination. We then elicited beliefs and behaviors regarding flu vaccination as well as spillovers to COVID-19 vaccination, including at a follow-up survey a few weeks later. Our sample consists of 2,893 White and Black men without a college education who had not received their seasonal influenza vaccine at the time of recruitment.3

Understanding the determinants of demand for preventive health care, including vaccines, has been of great interest to researchers. Important experimental work has shown the effectiveness of celebrity messages (Alatas et al. 2023), cues and nudges (Milkman et al. 2011), or increased accessibility (Brewer et al. 2017; Banerjee et al. 2010), particularly among those planning to be vaccinated. There is limited evidence, however, on how to persuade those who are not already intending to be immunized (in our sample, nearly half of respondents report that they are completely unwilling to receive an influenza vaccine). Which messages will resonate under such circumstances? And could some well-intentioned messages backfire? The urgency of answering such questions is underscored by the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on disadvantaged communities, the unequal vaccination rates across racial and ethnic groups in the United States, and the potential for new variants and COVID-19 endemicity.

Our videos, which were narrated by ten separate senders, held information about the safety and effectiveness of the influenza vaccine constant and varied along three policy-relevant dimensions: (i) the perceived medical expertise of the sender (“expertise”), (ii) the admission/omission of acknowledgement of past injustice committed by the medical community by discordant senders (“acknowledgement”), and (iii) the race of the sender (“concordance”). We tailored the expertise and acknowledgement interventions to Black respondents since Black men continue to comprise less than 3 percent of the US physician workforce, with their representation among admitted medical students stagnant since the late 1970s (Gallegos 2016; AAMC 2019). In general, the White US population has not faced the same systematic exploitation by the medical profession as Black Americans. Similarly, for White patients, racially concordant physicians are widely available, and discrimination by health-care providers is less common, lessening the need for lay senders (Sun et al. 2022). Understanding the potential of concordant community members to substitute for medical experts, as well as the role of acknowledgement of past injustice by discordant physicians may play in bridging trust gaps, holds relevance amid challenges in diversifying the physician workforce and persistent racial health inequalities (Street et al. 2008; Williams and Rucker 2000).

The layperson sender intervention was motivated by the ambiguous effects expertise may have on belief and behavior change. Medical doctors, the relevant experts in our study, have specialized training and experience and may therefore be considered more credible sources of health information than peers, all else equal. They are, however, also more socially distant from those who are disadvantaged, and such class cleavages could engender skepticism (Gauchat 2012; Eichengreen, Aksoy, and Saka 2021). Recent research in economics has revisited the role of expertise: Sapienza and Zingales (2013) find that providing ordinary Americans with information on the consensus opinions of academic economists does not move their beliefs, while DellaVigna and Pope (2018) document that nonexperts perform similar to experts in forecasting the rank of interventions. Representative surveys on trust and credibility indicate that respondents find “a person like yourself” as credible as academic experts and show a growing gap in institutional trust between individuals of high and low SES (Ries 2016). Experimentally, the variation we induce is between senders wearing a white coat and stethoscope (expert condition) and the same senders wearing a white short-sleeved shirt (layperson condition), narrating the same script.4 In a separate survey conducted on Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), senders in layperson attire are rated by respondents as 1.7 standard deviation units less educated than those in a laboratory coat (online Appendix Table 1), indicating that our experimental variation had the intended effect (i.e., a “first stage”).

The concordant expert arm was motivated by recent research showing that treatment by a race-concordant physician in an in-person setting can increase demand among Black Americans for preventive care as well as improve health outcomes (Alsan, Garrick, and Graziani 2019; Cooper-Patrick et al. 1999; Cooper et al. 2003; Greenwood, Carnahan, and Huang 2018; Greenwood et al. 2020; Hill, Jones, and Woodworth 2023). Evidence is limited, however, on whether these effects exist in one-way communication settings. In a pair of randomized evaluations of video messages recorded by physicians regarding mask wearing and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, the first such messaging study found small but robust sender concordance effects among Black respondents on information-seeking behavior (Alsan et al. 2021). However, the second study, by the same set of authors and using a more complicated design, failed to detect such effects (Torres et al. 2021). This paper builds on and extends the prior studies to include vaccination views and behavior.

The acknowledgement arm, in which some White senders acknowledge past breaches of trust committed by the medical community, could provide an alternative, scalable way to increase trust in medical recommendations amid a largely non-Black physician workforce. While acknowledgement of historical medical injustice can be expressed through a variety of approaches, we developed a short statement corresponding closely to the one proposed for use by physicians in an Annals of Internal Medicine editorial on responding to vaccination concerns (Opel, Lo, and Peek 2021). The proposed script from Annals reads “I understand why you have a lot of mistrust. The government and research systems have not always treated your community fairly,” and can be compared to our script found in Section I. Before distributing this type of message at scale, however, it is imperative to test its effectiveness, as unintended negative consequences are also conceivable.

We establish three main results. First, when comparing layperson to expert senders, we find that lay senders are rated by respondents as substantially less qualified and trustworthy (0.54 standard deviation units) to give general medical advice. However, individuals in the nonexpert condition exhibit greater recall of factual signal content and increase their willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine by 8.8 percentage points (20 percent). Furthermore, respondents assigned to lay senders were 15 percentage points (39 percent) more likely to report that they or their household members had received the flu vaccine in the weeks between the baseline and follow-up surveys. There is substantial attrition between the baseline and follow-up (the latter was conducted several weeks later to allow individuals time to receive a flu shot). Such attrition is not uncommon after such a length of time or among studies of vulnerable populations, but suggests caution in interpreting results on take-up. Nevertheless, attrition did not vary across arms, and the layperson intervention is the only intervention with a take-up rate that is statistically significantly different from (namely, higher than) that of other interventions.

Second, we find that concordance effects on sender and signal ratings are present exclusively among Black respondents, with no such effects evident among White respondents. We further find that acknowledgement of past breaches of trust by a race-discordant expert sender increases ratings of the signal by approximately the same magnitude as a race-concordant expert sender providing the standard signal without acknowledgement (an increase of 0.14 standard deviation units). Neither intervention, however, significantly affects vaccine take-up as measured in the follow-up survey, although coefficient estimates on intent to vaccinate against influenza and COVID-19 are weakly positive in both arms.

Third, we find striking heterogeneity by treatment arm across respondents with varying levels of vaccination reluctance. Viewing previous flu vaccination experience as a proxy for distance from a take-up “threshold,” we divided the sample into “most hesitant,” “moderately hesitant,” and “least hesitant” based on the date of a respondent’s last influenza vaccine. We find that both the concordance and acknowledgement interventions demonstrate significant effects on flu and COVID-19 vaccination intent among those least hesitant—those who had received seasonal flu vaccines within the past two years (about a quarter of the sample). In sharp contrast, the effectiveness of nonexperts was strongest among those most hesitant—those who had never previously received a flu vaccine (another quarter of the sample)—with individuals in this group rating the signal from a nonexpert (relative to that of the expert) significantly higher than respondents who had previously taken up the flu vaccine and exhibiting substantial increases in flu and COVID-19 vaccination intent (by 47 percent and 49 percent, respectively).

Taken together, these findings represent a step toward identifying effective ways to influence immunization views and behaviors. While messages from concordant and empathetic experts may resonate most among individuals familiar with vaccination, our study suggests that peer figures, such as community health workers or citizen ambassadors, could play an important role in communicating benefits and dispelling myths about vaccines among those least inclined to receive one.

I. Experimental Design

A. Experiment Overview

We collected data in two flu seasons: 2019–2020 and 2020–2021. Respondents were recruited via survey panels from Qualtrics, Lucid, CloudResearch, and Facebook and participated in the experiment through an online survey on Qualtrics. We timed the experiment so that it would fall into the middle of the flu season (between December and February in 2019–2020 and between late October and January in 2020–2021), so as to ensure recruitment of participants who would be unlikely to get the flu vaccine in the absence of our intervention.5 Upon completing the consent process, participants answered a set of questions to determine eligibility based on self-identified gender (male), race (Black or White), age (25–51), education (no college), and flu vaccine status (had not yet been vaccinated for influenza in the current season).6

Eligible respondents continued to answer basic demographic questions, reported their baseline attitudes and beliefs about the flu vaccine, and then watched a video infomercial, described in the next paragraph. After the infomercial, we gathered the main survey-based outcome measures and distributed a coupon for a free flu shot. We note that many places distribute free flu shots for indigent populations and that many insurance providers cover flu shots. However, in the event that cost was a barrier for a handful of individuals, the coupon removed it, thus leaving only nonmonetary barriers to vaccination. At least two weeks later, participants were invited to complete a follow-up survey to measure medium-term impacts of our video treatment and to measure respondents’ self-reported flu vaccination status. See online Appendix Figure 3 for an overview of the study design. Participants received a financial incentive for completing the baseline and follow-up survey (between $5 and $20) in the form of an electronic gift card.

B. Treatment Variation

In order to test whether the expertise of the sender, race concordance, and acknowledgement statements influence the key outcomes of interest, we aimed to produce videos that held all other factors precisely constant. This required tight control over key features of the video, such as the lighting, script, intonation, speaking rate, and sender appearance (such as age, height, facial hair, and clothes). Ensuring such consistency necessitated the use of a professional recording studio as well as the use of actors for the recording of the videos.7

We produced videos with a total of five Black and five White male actors (“senders”), recruited from the same casting agency. Each sender recorded the video in four variations, representing the experimental variation in expertise (expert versus nonexpert layperson) and signal content (standard versus including an acknowledgement statement).8 Within each treatment condition, subjects were randomly assigned in equal proportions to one of five recorded senders of the assigned race. The randomization was stratified by season and recruitment platform. All senders wore the exact same clothes, provided by the research team. In the expert role, the senders wore a button-down blue shirt, striped tie, laboratory coat and stethoscope. In the layperson role, they wore a white short-sleeved shirt.

The standard signal (video script S1) was 40 seconds long and read9

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, recommends everyone 6 months and older get the flu shot. The shot protects you from getting sick by cutting your chance of catching the flu in half. It’s also very safe: less than 1 in 100 vaccinated people experiences a side effect such as fever or chills. The flu shot does not contain an active flu virus, so you cannot get the flu virus from the shot. I get the flu shot every year to protect myself, my family, and my community. I recommend you look into getting vaccinated as soon as possible.10

The script of acknowledgement signal (S2) was identical to the above except that three sentences were added acknowledging historical injustices committed by the medical establishment. They were placed in between the first and second sentence of script S1 and read “I know some people are nervous to follow medical advice about vaccines. In the past, there may have been times when the medical community broke your trust. But I hope that sharing some information with you can help you understand how important the flu shot is.”

We aimed for the two groups of actors to have a similar distribution of age and training in acting. We validated the former criterion via external MTurk ratings of each actor (in each role) on age and also collected perceptions of attractiveness and educational attainment from the MTurk sample. Columns (1) through (3) of online Appendix Table 1 reveal that Black MTurkers rate lay senders as less educated, less attractive, and younger than the same set of senders wearing white coats. Such results support the notion that the senders in casual attire were perceived as less advantaged than expert senders.

There are no statistically significant differences in perceived age and education between concordant and discordant expert senders among Black MTurk respondents (online Appendix Table 1, columns (4) to (5)). Black respondents do, however, rate Black expert senders as more attractive (column (6)).

Consistent with implicit bias, White MTurkers perceive Black expert senders wearing a white coat as 0.53 standard deviations younger and 2.84 standard deviations less educated than White senders in a white coat (columns (7) to (8)). These differences are statistically significant. They should be kept in mind when interpreting the (null) results among White respondents. Online Appendix Figure 4 presents perceived within-sender education differences (white coat versus casual attire for Black versus White senders). We observe that the penalty for a Black male wearing casual attire is much greater than for a White male, as they are perceived to be significantly less educated. These findings connect to a broader literature about stereotypes and the profiling of Black men in the United States (Hester and Gray 2018; Oliver 2003).

II. Outcome Variables

We consider four primary and four secondary outcomes, described in detail in the next subsections and summarized in brief here.

Our primary outcomes include measures of perceptions of both the message and the messenger—which are important to elucidate mechanisms—as well as measures of the intent to get vaccinated. As secondary outcomes, we include additional measures aimed at elucidating mechanisms (including information recall and beliefs about the safety of flu shots) and measures of vaccine demand and take-up: we elicited an incentive compatible measure of demand for a free flu shot, and we collected information about self-reported vaccine take-up as measured via a follow-up survey. However, because flu shots are widely available for free, and because of sizeable attrition to the follow-up survey, respectively, we consider both to be relatively noisy, suggestive measures of the underlying outcomes of interest.

Online Appendix Section E presents the survey question text underlying our outcome measures. Several of our outcomes are constructed as an index composed of answers to several survey questions that are proxies for the same outcome. The advantage of using indices is that it reduces noise as well as the risk of false positives (in terms of statistical significance) due to multiple hypothesis testing. We construct each such index as an inverse covariance-weighted average, as described in Anderson (2008). Construction of outcomes follows our preanalysis plan.11

A. Primary Outcomes

Rating of sender: This outcome is an index comprised of responses to survey questions regarding whether the respondent was interested in further medical advice from the given sender and trusted advice from the sender, and the respondent’s assessment of the sender’s qualification to provide medical advice.

Rating of signal: This outcome is an index comprised of responses to survey questions on recommending the video to friends and family, recommending the flu shot to friends and family, and the respondent’s assessment of the extent to which the information contained in the video was useful.

Flu vaccination intent: This refers to the respondent’s self-reported likelihood of receiving the flu vaccine before the end of the flu season. It was elicited on an 11-point Likert scale, once before and once after the video message treatment. We present results on posterior intent (instead of changes in intent) to keep in parallel with the COVID-19 vaccination outcome measure. We rescaled this outcome to have support 0 to 1.

COVID-19 vaccination intent: This refers to the respondent’s self-reported likelihood of taking up the COVID-19 vaccine if made available free of charge, elicited on the same scale as flu vaccination intent. We rescaled this outcome to have support 0 to 1. Since COVID-19 was not yet prevalent during the 2019–2020 flu season, we asked this question only in the second wave of data collection—i.e., during the 2020–2021 flu season.

B. Secondary Outcomes

Signal content recall: This outcome is an index comprised of responses to survey questions on the age group for whom the flu vaccine is recommended and whether the flu shot contains the flu virus (recall of information discussed in the video).

Safety beliefs: This outcome is an index comprised of the point belief and the certainty on the likelihood to contract the flu from the flu shot, measured by a Likert scale and balls-and-bins method, respectively. Both measures were elicited twice, once before and once after the video message treatment, and we use the posterior-prior difference of each in our index.

Coupon interest: This outcome is an index comprised of two revealed preference measures of demand for a free flu shot coupon—willingness to pay for the coupon as well as demand for information regarding locations to redeem the coupon; both were elicited in an incentive compatible manner—see online Appendix Section E for details. Since only 3 percent of individuals in our sample mention cost as a major barrier to vaccination take-up (see online Appendix Figure 2), we consider this outcome to be a relatively noisy proxy for flu shot demand.

Flu vaccine take-up: This outcome is binary and equals one if respondents reported in the follow-up survey that they or their family members had received the flu shot, or if we observed redemption of the coupon. It is not a primary outcome, because attrition to the follow-up survey is sizable, and because coupon redemption data likely provide a very incomplete picture of actual flu vaccine take-up.12

III. Descriptive Statistics, Balance, and Attrition

Our main sample includes all respondents who fulfilled our eligibility criteria (see Section I), passed our quality check, and completed the baseline survey. Attrition after randomization was low: among all respondents who arrive at the video treatment stage of the survey, 89 percent completed the survey. Online Appendix Table 3 tests for imbalance in attrition by treatment status both during the baseline survey (columns 1 and 2) and between the baseline and follow-up surveys (columns 3 and 4). The only statistically significant differential attrition we detect in the former is among White respondents who were assigned to a Black sender: they exited the baseline survey at a higher rate (2.3 percentage points, p-value 0.09), suggesting that those who remained were not as averse to discordant senders. Attrition between the baseline and follow-up is substantial, though such high attrition is not entirely unexpected given the lengthier time period between the two surveys—necessitated in order to observe vaccine seeking behavior—and the sample composition, as socially disadvantaged individuals tend to have lower response rates and higher loss to follow-up. Online Appendix Table 3, columns (3) and (4) demonstrate that there is no differential attrition across treatment arms.

Summary statistics are presented in Table 1. We recruited approximately 400 Black respondents for each of the interventions (concordant expert, concordant lay, discordant expert, discordant expert plus acknowledgement) and approximately 600 White respondents for each of the two interventions to which White respondents were assigned (concordant expert, discordant expert). Respondents were on average 37 years old, and about 53 percent reported an annual household income below $30,000. Approximately 27 percent of the sample had never received a flu vaccine, while 28 percent received one in the past 2 years, and the remainder more than 2 years ago. Among the latter group, the majority (66 percent) received the flu vaccine more than 5 years ago. Before viewing the infomercial, respondents report a mean likelihood of receiving the flu vaccine of 2.57 on a 0–10 point scale.

Table 1—

Summary Statistics

| Scale | All | Black | White | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Panel A. Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age | (C) | 36.83 (6.74) | 2,893 | 35.87 (6.56) | 1,672 | 38.14 (6.76) | 1,221 |

| Low household income | (B) | 0.53 (0.50) | 2,893 | 0.60 (0.49) | 1,672 | 0.42 (0.49) | 1,221 |

| Completed high school | (B) | 0.88 (0.32) | 2,893 | 0.88 (0.33) | 1,672 | 0.89 (0.31; | 1,221 |

| Married | (B) | 0.25 (0.43) | 2,893 | 0.19 (0.39) | 1,672 | 0.32 (0.47) | 1,221 |

| South | (B) | 0.52 (0.50) | 2,879 | 0.58 (0.49) | 1,667 | 0.44 (0.50) | 1,212 |

| Panel B. Health characteristics | |||||||

| Insured | (B) | 0.63 (0.48) | 2,809 | 0.60 (0.49) | 1,602 | 0.66 (0.47) | 1,207 |

| Subjective health status | [1,5] | 3.47 (1.03) | 2,893 | 3.64 (1.02) | 1,672 | 3.23 (0.99) | 1,221 |

| Subjective flu shot cost | (C) | 33.56 (70.94) | 2,893 | 39.71 (82.60) | 1,672 | 25.15 (49.62) | 1,221 |

| Has primary care provider | (B) | 0.47 (0.50) | 2,893 | 0.44 (0.50) | 1,672 | 0.53 (0.50) | 1,221 |

| Most hesitant | (B) | 0.27 (0.45) | 2,893 | 0.27 (0.45) | 1,672 | 0.28 (0.45) | 1,221 |

| Moderate hesitant | (B) | 0.45 (0.50) | 2,893 | 0.45 (0.50) | 1,672 | 0.45 (0.50) | 1,221 |

| Least hesitant | (B) | 0.28 (0.45) | 2,893 | 0.28 (0.45) | 1,672 | 0.28 (0.45) | 1,221 |

| Panel C. Prior elicitation | |||||||

| Flu vaccine intent | [0,10] | 2.57 (3.23) | 2,893 | 2.57 (3.26) | 1,672 | 2.56 (3.19) | 1,221 |

| Likelihood of contracting flu | [0,10] | 2.48 (2.77) | 2,893 | 2.21 (2.83) | 1,672 | 2.84 (2.65) | 1,221 |

| Belief about safety of flu vaccine | [0,100- | 57.22 (28.09) | 2,893 | 54.45 (27.86) | 1,672 | 61.02 (27.98) | 1,221 |

Notes: Columns 2–3 show the mean, standard deviation, and sample size for all respondents. Columns 4–5 restrict the sample to Black respondents, and columns 6–7 restrict the sample to White respondents. Low household income is a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent’s self-reported household income is less than or equal to the median income of Black respondents in the sample (= $30k). Subjective health status is measured on a five-point Likert scale (where 1 is poor and 5 is excellent). Subjective flu shot cost is in US dollars; the values above the ninety-ninth percentile are set to the ninety-ninth percentile value. Most hesitant is a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent has never received the flu shot. Moderate hesitant is a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent has received the flu shot more than two years ago. Least hesitant is a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent has received the flu shot within the past two years. Flu vaccine intent is the respondent’s prior intent to receive the flu vaccine before the end of the flu season elicited on an 11-point Likert scale. Likelihood of contracting flu is the respondent’s subjective likelihood of contracting flu before the end of the flu season elicited on an 11-point Likert scale. Belief about safety of flu vaccine is belief over how many individuals out of 100 will not contract the flu from the flu shot. (C) indicates that the variable is continuous; (B) indicates that the variable is binary. In cases when the variable is not binary or continuous, the scale of the raw variable is provided.

We detect differences across racial groups that reflect broader social inequality: Black respondents report lower incomes, rates of high school completion, and health insurance coverage rates, although they express slightly higher average subjective health status. The relationship between COVID-19 vaccination intent and flu vaccination intent (as measured following the video intervention) is strongly positive (correlation coefficient = 0.58, online Appendix Figure 5), indicating that there may be a generic aversion to immunization.

Observable characteristics and preintervention views are well balanced across treatment assignment in the baseline survey (online Appendix Table 4). As noted above, there was a lower response rate for the follow-up survey, though we do not detect differential response rates across study conditions. Characteristics are generally well balanced across conditions in the follow-up survey, although a handful of exceptions are observed (see online Appendix Table 5).

IV. Results

Results are organized corresponding to the four study arms (i.e., lay versus expert sender among Black respondents, acknowledgement versus standard signal among Black respondents, concordance versus discordant expert senders for Black respondents, and concordance versus discordant expert senders for White respondents). We report estimates with robust standard errors obtained from a linear regression of the variables described in Section II on treatment indicators. We include the stratifying variables of recruitment season and survey platform (combining the Facebook and CloudResearch platforms, given their low recruitment numbers) in all regressions.

We present our main results from the baseline survey in Table 2. There are four columns, one for each primary outcome. Outcomes in columns 1 and 2 are normalized to mean zero and standard deviation one, while outcomes in columns 3 and 4 are the self-reported likelihood (i.e., intent) to receive the flu and COVID-19 vaccination, respectively.13

Table 2—

Treatment Effect Estimates

| Rating sender | Rating signal | Flu vaccine intent | COVID-19 vaccine intent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Panel A. Layperson versus expert: Black respondents | ||||

| Layperson treat | −0.540 | −0.081 | 0.019 | 0.088 |

| (0.071) | (0.067) | (0.025) | (0.030) | |

| [0.000] | [0.231] | [0.455] | [0.003] | |

| Mean in control | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.43 |

| Observations | 845 | 845 | 845 | 592 |

| Panel B. Standard versus acknowledgement signal: Black respondents | ||||

| Acknowledgement signal treat | 0.100 | 0.142 | 0.027 | 0.054 |

| (0.068) | (0.069) | (0.025) | (0.031) | |

| [0.145] | [0.040] | [0.287] | [0.080] | |

| Mean in control | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.40 |

| Observations | 827 | 827 | 827 | 581 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.819 | 0.433 |

| Panel C. Concordant versus discordant expert sender: Black respondents | ||||

| Concordance treat | 0.183 | 0.139 | 0.026 | 0.035 |

| (0.067) | (0.070) | (0.025) | (0.031) | |

| [0.007] | [0.049] | [0.302] | [0.254] | |

| Mean in control | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.40 |

| Observations | 832 | 832 | 832 | 587 |

| Panel D. Concordant versus discordant expert sender: White respondents | ||||

| Concordance treat | −0.075 | −0.009 | 0.003 | 0.009 |

| (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.021) | (0.025) | |

| [0.189] | [0.876] | [0.868] | [0.719] | |

| Mean in control | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.45 |

| Observations | 1,221 | 1,221 | 1,221 | 866 |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.100 | 0.487 | 0.512 |

Notes: Table reports OLS estimates. Each dependent variable in columns 1 and 2 is an inverse-covariance-weighted index as described in Anderson (2008) and standardized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Dependent variables in columns 3 and 4 are on a scale of 0 to 1. COVID-19 vaccine intent was asked during the 2020–2021 flu season only. Outcome variables are described in Section II and in online Appendix Section E. The p-value in panel B tests the null hypothesis that the acknowledgement signal treatment and layperson treatment effects are equal. The p-value in panel D tests the null hypothesis that the concordance treatment effects are the same across Black and White respondents. Stratifying variables (platform and season) are included as controls in the regression but not reported. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. p-values are in brackets.

A. Layperson versus Expert

Results comparing concordant nonexpert to concordant expert senders are displayed in panel A of Table 2. Respondents randomized to the layperson condition provide less favorable ratings of the sender, by 0.54 standard deviation units. The large negative effect on the rating of the sender lends credence to respondents paying attention: the measure includes a rating of the sender’s qualification to give general medical advice. This finding also accords with the perception that senders wearing a white short-sleeved shirt are less educated and younger than those wearing a white coat (online Appendix Table 1 columns (1)–(3)).

Despite perceiving nonexpert senders to be of lower expertise, however, respondents assigned to such senders stated no lower intent to receive the flu vaccine, and even significantly increased their intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine by 8.8 percentage points relative to the expert sender condition. Consistent with this finding, the nonexpert sender condition significantly increased take-up of the flu vaccine: respondents assigned to lay senders were 15 percentage points more likely in our follow-up survey to report that they and/or another household member received the flu vaccine in the weeks since the baseline survey (a 39 percent increase).

Experimenter demand effect is not a reasonable explanation for these patterns, since all arms were “treated” in the study and there would need to be higher self-report bias among those viewing a signal from a nonexpert versus from a health authority figure, which seems very unlikely. Instead, respondents absorbed more information on the flu vaccine from lay senders, as reflected by a sizable positive effect of the lay treatment on signal content recall (0.12 standard deviation units). This finding is consistent with patients experiencing increased anxiety levels when interacting with a doctor (which can sometimes raise blood pressure, a phenomenon in clinical medicine dubbed “white coat hypertension”), which may in turn impair the ability to retain information. The lower rating of lay sender qualifications, moreover, did not translate into significantly less favorable beliefs or attitudes, such as on the perceived safety of the flu vaccine or interest in a flu vaccine coupon, compared to individuals randomized to an expert sender.

B. Acknowledgment versus Standard Message

Panel B of Table 2 reports the main effect of the acknowledgement signal intervention among Black respondents assigned to White expert senders. On average, Black respondents assigned to the acknowledgement statement condition rate the statement 0.14 standard deviation units higher than the default statement conveyed by the same set of senders. They are also 5.4 percentage points more likely to intend to take up the COVID-19 vaccine. We do not detect statistically significant effects of the acknowledgement statement on flu vaccine intent (and take-up).

C. Race Concordance versus Discordance

For Black respondents (panel C), race concordance has a positive, sizable effect on the respondent’s ratings of the sender (0.18 standard deviation units). Furthermore, relative to the discordant expert baseline signal, a race-concordant expert sender increases ratings of the signal by approximately the same magnitude as the acknowledgement of past breaches of trust by a race-discordant expert sender (an increase of 0.14 standard deviation units). By contrast, we do not detect concordance effects on sender or signal ratings among White respondents (panel D).

Concordance is associated with weak positive effects on flu and COVID-19 vaccination intent for Black respondents, but these are not statistically significant.14 As mentioned in Section III, White respondents assigned a discordant sender attrited at higher rates, which we view as a relevant outcome. It does, however, suggest that estimates reported in panel D are biased toward the (reported) null effect of concordance.15

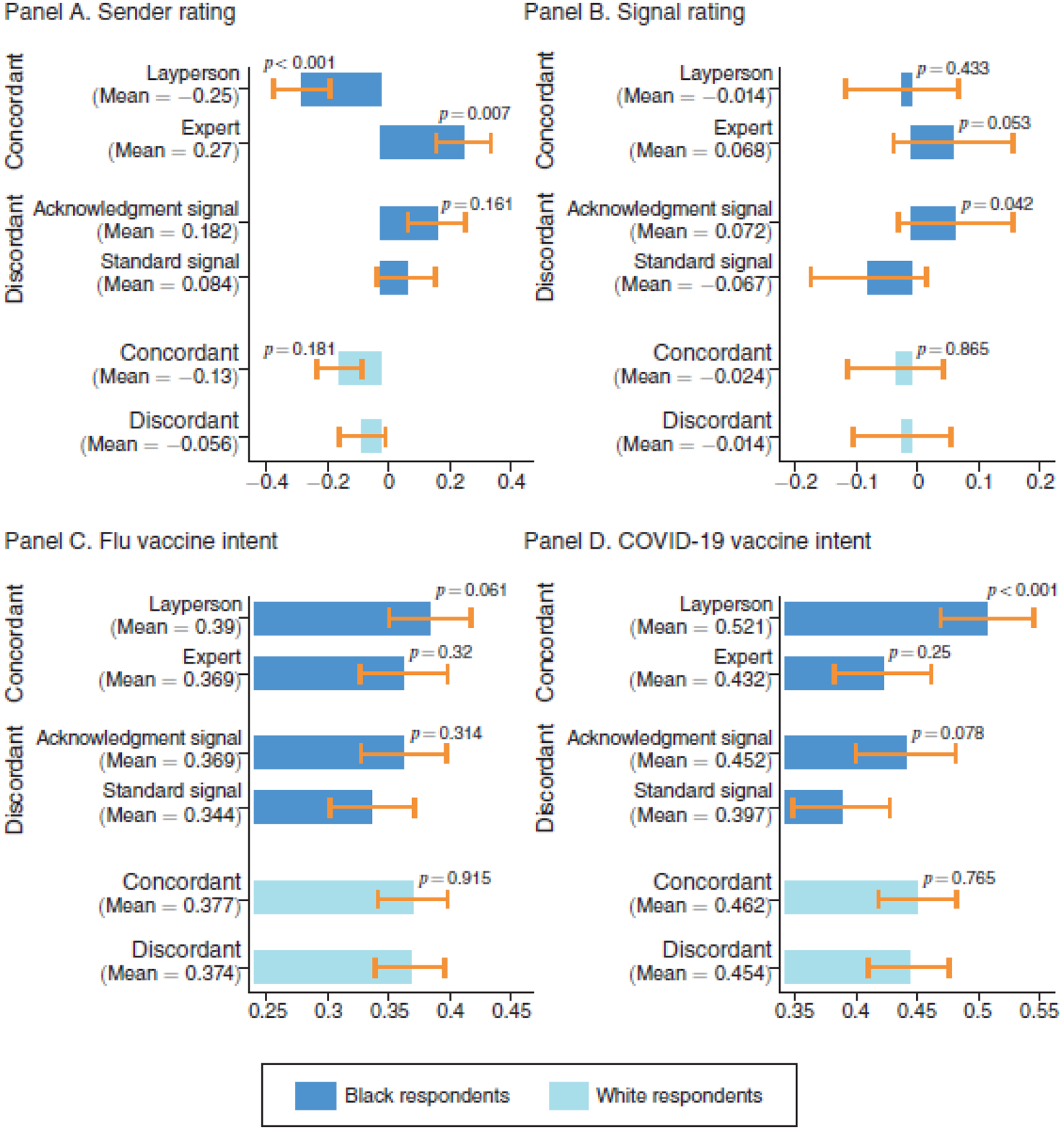

D. Most Effective Treatment, Overall

Figure 1 displays means of primary outcomes, as well as 95 percent confidence bands by treatment condition. Across our key measures of vaccination intention and behavior (including flu vaccine take-up, displayed in Panel (D) of online Appendix Figure 8), the layperson treatment condition consistently performs the best among Black respondents (dark-blue bars), whereas discordant expert senders fare poorly among Black individuals. White respondent averages (light-blue bars) across concordant and discordant treatment conditions do not meaningfully differ. Soberingly, flu and COVID-19 vaccination intent, as well as flu vaccine take-up, are substantially lower—by 3 to 6 percentage points—among Black respondents paired with a discordant expert sender than they are among White respondents paired with a concordant expert sender. As 85 percent of White patients in the United States have a concordant physician yet nearly 75 percent of Black patients do not, such a comparison mirrors the experience of many Black Americans in the US health-care system (Blewett et al. 2018). We find, however, that layperson senders shift Black respondents to levels of vaccination intent and take-up comparable to White respondents.

Figure 1.

Outcome Means by Treatment Arm

Notes: Figure shows the mean of each primary outcome by treatment condition among the sample of Black respondents (dark-blue bars) as well as among the sample of White respondents (light-blue bars). Sender and signal rating are inverse-covariance-weighted indices as described in Anderson (2008); flu and COVID-19 vaccine intent have support 0 to 1. For dark-blue bars, p-values test the null hypotheses that the concordant expert, concordant nonexpert (standard signal condition), and discordant expert (acknowledgement condition) means each differ from the discordant expert (standard signal condition) among Black respondents. For light-blue bars, p-values test the null hypothesis that the concordant expert (standard signal condition) mean differs from the discordant expert (standard signal condition) among White respondents. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals using robust standard errors are shown.

An assessment of the overall effect of any one signal on outcomes, relative to no signal at all, is of interest in itself as well. However, since the focus of this study is on testing the differential effectiveness of signal frames aimed at bridging trust gaps relative to a standard signal from a typical expert sender, we did not include a no-signal control group. Therefore, we cannot assess the impact of any one signal relative to a no-signal counterfactual directly, but differences between posterior and prior flu vaccination intent do provide some suggestive evidence (online Appendix Figure 9). Reassuringly, we observe an increase or no change in flu vaccine intent among the vast majority (approximately 90 percent) of respondents.

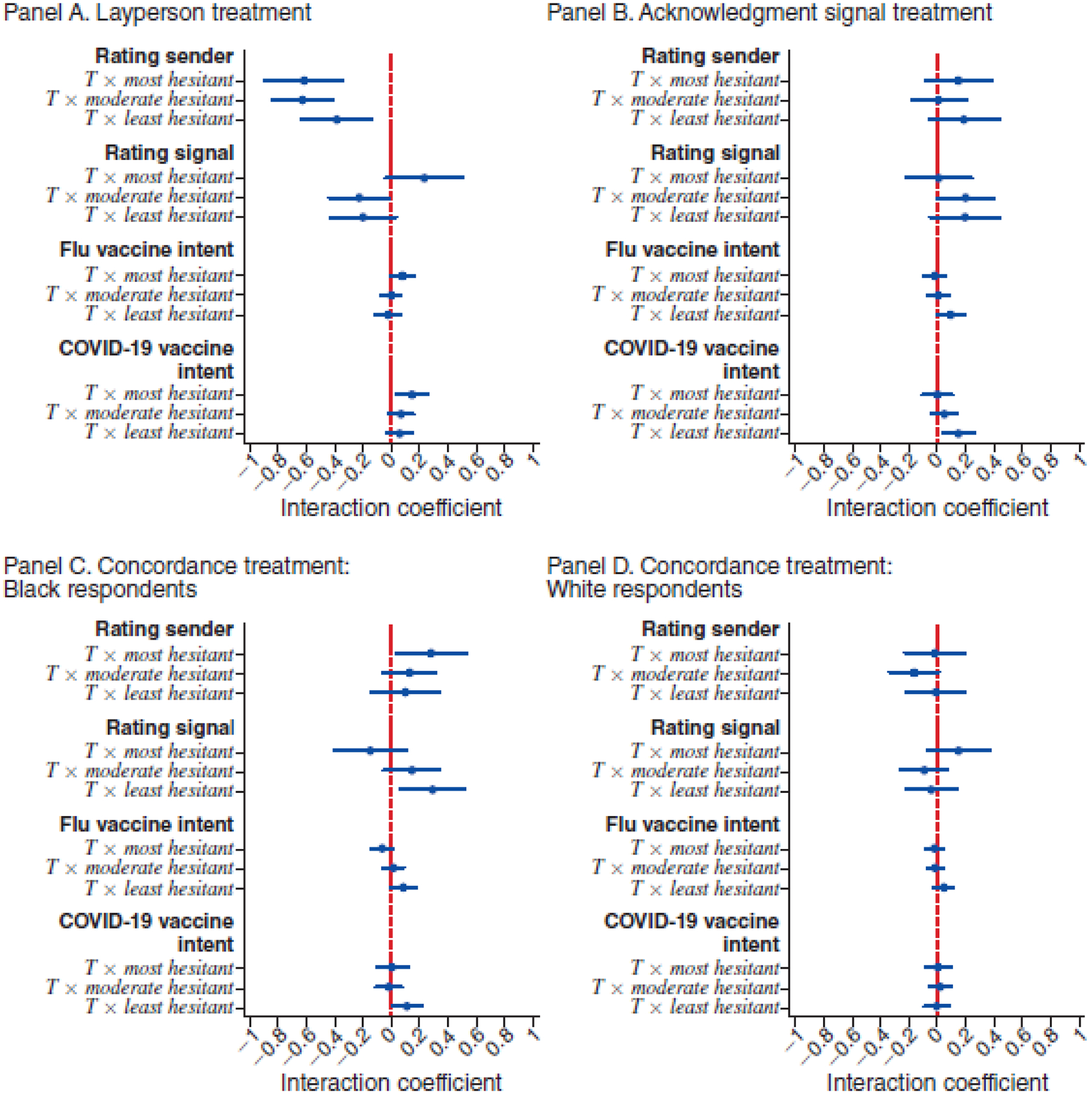

E. Heterogeneity

What type of message is most persuasive may depend upon an individual’s baseline beliefs about vaccines, which may be shaped by past experience with medical experts and vaccination. Those who elected to receive an influenza vaccine at some point in their lifetime may be less opposed to vaccines than those who never evinced a willingness to do so, all else equal.16 We divided the sample into three groups—“most hesitant,” “moderate hesitant,” and “least hesitant”—based on whether the respondent reported never receiving a flu vaccine, receiving a flu vaccine over two years ago (with the majority of these individuals receiving their last vaccine over five years ago), or receiving a flu vaccine recently (within the past two years, exclusive of the current season).

We fully interact our treatment effects with the three hesitancy indicator variables and report the results for each study arm in Figure 2.17,18 As hypothesized, we find striking heterogeneity in the persuasiveness of interventions across hesitancy groups: the lay signal is most persuasive among the most hesitant, while the acknowledgement and concordance conditions persuade those less hesitant more.

Figure 2.

Heterogeneity by Vaccine Hesitancy

Notes: Based on OLS regression of each outcome (listed in bold face on the y-axis) of following form yi = α + β1Ti × Mosti + β2Ti × Moderatei + β3Ti × Leasti + γ1 Moderatei + γ2 Leasti + μXi + ϵi. Interaction coefficients are shown. Most hesitant is a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent has never received the flu shot. Moderate hesitant is a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent received the flu shot more than two years ago. Least hesitant is a binary variable equal to 1 if the respondent received the flu shot within the past two years, not including the current season. Controls Xi include season dummy and survey platform fixed effects. Sender rating and signal rating are inverse-covariance-weighted indices as described in Anderson (2008). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals using robust standard errors are shown.

Specifically, panel A shows that nonexperts are consistently judged as unqualified to provide medical advice and that this does not vary by prior flu vaccination experience. However, the rating of the signal delivered by nonexpert senders is more positive among the most hesitant, and this difference is statistically significant at the 10 percent level, a result strikingly different from the perception among the least hesitant. Moreover, the effect of nonexpert senders on both influenza and COVID-19 vaccine intent is large, significant, and positive for the most hesitant, and, in the former case, statistically different from those who are least hesitant.

The positive effect of the acknowledgement intervention on signal ratings is driven by those who have ever received a vaccine (i.e., the “moderately hesitant”), with the coefficient estimate among the least hesitant large but imprecise (panel B). The acknowledgement signal increases flu and COVID-19 vaccination intent substantially among the least hesitant of the flu vaccine, while effects on intent among the most hesitant are muted and significantly different from respondents with recent immunization experience.

Panel C demonstrates that among Black respondents, concordance effects on signal ratings and flu vaccination intent are positive and statistically significant only among those that have recently taken up the vaccine (i.e., the least hesitant). There is no such heterogeneity among White respondents in panel D.

F. Contextualizing Findings

Our findings suggest that two key processes shape how individuals absorb advice about vaccines; they jointly rationalize the central findings of our paper:

A patient’s trust in medical advice from experts (relative to laypersons) may differ when the advice concerns vaccines or other preventives versus when it concerns the treatment of an acute condition; such a dynamic is consistent with two key findings in our data: First, we find that rating of the signal (in terms of its relevance, as well as willingness to share the information provided) is much more predictive of vaccination intention than the rating of the sender (which captures respondent’s perception of the sender’s medical expertise and qualification to provide general medical advice). Second, we find that the nonexpert intervention simultaneously performs “worst” with respect to respondents’ trust in the medical qualifications of the sender, while performing “best” with respect to vaccination intent and take-up.

The decision to follow medical advice on vaccines among low-SES, vaccine-hesitant individuals may not operate through direct updating about the parameters of vaccine safety and effectiveness but through mental “ shortcuts” that operate at a faster and easier level: through assessments of whether the advice giver is perceived as trustworthy when it comes to advice about vaccines. This assessment, in turn, may depend on many factors, such as the sender’s social proximity (in age, race, or perceived SES). This hypothesis is in line with our finding that vaccination intent and take-up may increase even though we do not observe updating about, for example, vaccine safety. It also rationalizes why updating differs across intervention arms even though the information disseminated is precisely held constant.

V. Conclusion

Low demand for high-value preventive care is of interest to policymakers and a puzzle for researchers. In this paper, we examine the effect of various sender and signal combinations on vaccination outcomes in a sample of low-SES men. Although race-concordant expert senders and race-discordant expert senders acknowledging past medical injustice earned higher ratings from Black individuals, we find that signals on vaccination delivered by a race-concordant layperson led to the greatest increases in intent to be vaccinated against influenza and COVID-19 as well as take-up of the flu vaccine. The effects of nonexpert senders were concentrated among respondents with no prior experience with flu vaccination, a group that may be particularly difficult to persuade, whereas experts move vaccination intent most among those immunized in recent years.

These results are important in understanding how best to improve vaccination take-up rates and reduce health inequality. The effectiveness of nonexpert senders relates to work by Larson (2020), who notes that individuals reluctant to vaccinate may be more moved by “heard truths” from proximate community members than by elite experts. An alternative explanation is that medical doctors discussing the benefits of vaccination are viewed as agents not solely of the individual patient but also of broader social interests or private interests such as insurers or pharmaceutical companies.19 Through such a lens, professionals, though qualified, may also appear conflicted, whereas laypersons do not. More broadly, our results suggest a role for communicating information on preventive care through senders diverse both in racial background and level of expertise.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Minjeong Joyce Kim, Nikhil Shankar, and Lukas Leister for excellent research assistance. We also thank Mackenzie Alston, Luca Braghieri, Amitabh Chandra, Stefano DellaVigna, Esther Duflo, Amy Finkelstein, Matthew Gentzkow, Mirelle Jacobson, Damon Jones, Heather Royer, Kosali Simon, Marianne Wanamaker, Crystal Yang, J-PAL North America board and reviewers as well as participants in seminars at ASSA, Brown University, Harvard/MIT/BU Health Economics, Stanford, UCSB, UCSD, and Washington University in St. Louis for comments. The study was approved by IRB at Harvard University (IRB19-1424) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov. (NCT04160975), AEA RCT registry (AEARCTR-0004796), and OSF (DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/XJ5WP) Data and code for data cleaning and analysis are provided as part of the replication package, which is available at http://doi.org/10.3886/E178301V1.Funding was provided by J-PAL North America and Harvard Kennedy School. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute on Aging under award number P30AG064190. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no conflicts to disclose. Previously circulated under the title “Persuasion in Medicine: Messaging to Increase Vaccine Demand.”

Footnotes

Go to https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20210393 to visit the article page for additional materials and author disclosure statement(s) or to comment in the online discussion forum.

The seasonal influenza vaccine alone averts 3,500 to 12,000 deaths a year and reduces work loss due to the illness by nearly one-fifth (CDC 2020).

See online Appendix Figure 2, which explores reasons for not vaccinating among our sample. Note that vaccination take-up among Hispanic men is also relatively low, but this population was not included in this study.

The education cutoff still represents a substantial fraction of US men (approximately 50 percent of Black men and 35 percent of non-Hispanic White men in the US population (Health Day News 2021)).

In the remainder of the paper, we refer to senders in the expert condition as expert senders, while senders in the layperson condition are layperson senders. For experimentation on doctor attire, see Varnado-Sullivan et al. (2019) and Petrilli et al. (2018).

By the fourth week of October 2020, flu shot distribution was on par with the first week of December 2019 (165 and 169 million doses, respectively), likely accelerated by the pandemic (CDC 2021b).

We did not recruit participants aged older than 51, because a different vaccine than the one covered by our flu shot coupon is advised for older individuals. We also excluded those aged between 18 and 24 because we aimed to recruit individuals without a college education, and they may still be in college. Online Appendix Figure 1 demonstrates the relatively low vaccine take-up among low-SES men, which motivates our focus on that particular demographic group.

In prior work (Alsan, Garrick, and Graziani 2019; Alsan et al. 2021; Torres et al. 2021), our team used licensed medical doctors for messaging. However, given the fine titration of all elements of the messaging and the need for the same person to play multiple roles, we used actors in this instance. Note that the same person who delivered the message as an expert recorded as a nonexpert too; thus, either experts would have had to have acted as nonexperts or vice versa. We debriefed respondents about the use of nonexpert actors in the influenza infomercials as well as the tracking of coupons, per IRB guidance, at the end of the follow-up survey.

Because of the low marginal cost of recording additional videos, we had each actor record all four video variations; however, for power considerations and because pipeline issues for medical professionals are not as relevant for White respondents, nor is the shameful history of medical exploitation, we only used the standard lay and standard expert videos for Black actors and the standard expert and acknowledgement expert videos for White actors in the experiment.

See online Appendix Section D for links to the videos we recorded.

In the layperson video, we replaced the word “cannot” with “can’t” in the script.

We make one meaningful deviation from our preanalysis plan: to accommodate referee comments remarking that a full set of outcomes elicited is difficult to parse, we split the set of eight main outcomes into four primary and four secondary ones, presenting results on the latter in the online Appendix. The decision about which results to designate as secondary outcomes mainly followed considerations about data quality outlined above.

Pharmacies reported to TotalWellness, Inc., the coupon vendor, whether the coupon was used and shared this information with the study team. Because well below 1 percent of coupons were recorded as redeemed, we combine self-reported flu shot receipt as reported at follow-up with the coupon redemption data into a single outcome. The low recorded redemption rate stands in contrast to self-reported usage rates of 15.5 percent as per our follow-up survey. The gap is likely due to pharmacists billing insurance instead of using coupons—74 percent of respondents with discrepancies were insured. If we recode all inconsistencies as not having been vaccinated, the conclusions reported herein are unchanged. We also show results on redemption separately in online Appendix Table 2.

Results pertaining to secondary outcomes are presented in online Appendix Table 6.

There may be a concern that Black and White senders may differ along other characteristics besides race (e.g., Heckman 1998 and Pager 2007). We designed this experiment to minimize such concerns by holding key other dimensions (e.g., sex, age, clothing, setting and script) constant. We also demonstrate that the effect of any given Black sender on most of the outcomes is indistinguishable from other Black senders in the concordance arm (see online Appendix Table 7 for the rating outcomes). For one outcome (COVID-19 vaccine intent), we do reject the null; however, there are no concordance effects detected for this outcome (see column 4 of Table 2, panel C). Similarly, we do not detect heterogeneity in the layperson treatment effect by sender (online Appendix Table 8).

Individual outcomes that comprise the indices can be found in online Appendix Figures 6 and 7. Specifications including LASSO-chosen controls can be found in online Appendix Table 9. Estimates with Lee (2009) bounds, available on request, also fail to find an effect.

Indeed, we find that 69 percent of those who never received a flu vaccine in the past state prior to the video treatment that they are “not at all likely” to receive the flu vaccine in the current season, compared to 54 percent of those who are moderately hesitant and 20 percent of those who are least hesitant as measured by past vaccination take-up. Online Appendix Figure 10 provides a histogram of prior flu vaccine intent by respondent vaccination experience.

We also test the null hypothesis that treatment effects for the most and least hesitant individuals are equal and report results in online Appendix Table 10.

We present additional heterogeneity results along other margins in online Appendix Figure 11.

One such comment from a respondent was “Medical industry using mind games to get people to buy their nonsense.” We thank Keith Ericson for the interpretation of doctors as agents acting on behalf of potentially multiple principals.

Contributor Information

Marcella Alsan, Harvard Kennedy School and NBER.

Sarah Eichmeyer, Bocconi University.

REFERENCES

- Alatas Vivi, Chandrasekhar Arun G., Mobius Markus, Olken Benjamin A., and Paladines Cindy. 2023. “Do Celebrity Endorsements Matter? A Twitter Experiment Promoting Vaccination in Indonesia.” https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2023-10/Indonesia_Twitter_Paper_manuscript.pdf (accessed on November 20, 2023).

- Alsan Marcella, and Eichmeyer Sarah. 2024. “Replication Data for: Experimental Evidence on the Effectiveness of Nonexperts for Improving Vaccine Demand.” American Economic Association [publisher], Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. 10.3886/E178301V1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsan Marcella, and Wanamaker Marianne. 2018. “Tuskegee and the Health of Black Men.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 133 (1): 407–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsan Marcella, Stanford Fatima Cody, Banerjee Abhijit, Breza Emily, Chandrasekhar Arun G., Eichmeyer Sarah, Goldsmith-Pinkham Paul, et al. 2021. “Comparison of Knowledge and Information-Seeking Behavior after General COVID-19 Public Health Messages and Messages Tailored for Black and Latinx Communities: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Annals of Internal Medicine 174 (4): 484–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsan Marcella, Garrick Owen, and Graziani Grant. 2019. “Does Diversity Matter for Health? Experimental Evidence from Oakland.” American Economic Review 109 (12): 4071–111. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Medical Colleges. 2019. “Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019—Figure 20. Percentage of Physicians by Sex and Race/Ethnicity, 2018” https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-20-percentage-physicians-sex-and-race/ethnicity-2018 (accessed March 10, 2021).

- Anderson Michael L. 2008. “Multiple Inference and Gender Differences in the Effects of Early Intervention: A Reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and Early Training Projects.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 103 (484): 1481–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj Simar Singh, and Stanford Fatima Cody. 2021. “Beyond Tuskegee—Vaccine Distrust and Everyday Racism.” New England Journal of Medicine 384 (5): e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee Abhijit Vinayak, Duflo Esther, Glennerster Rachel, and Kothari Dhruva. 2010. “Improving Immunisation Coverage in Rural India: Clustered Randomised Controlled Evaluation of Immunisation Campaigns with and without Incentives.” BMJ 340: 2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava Saurabh, Loewenstein George, and Benartzi Shlomo. 2017. “The Costs of Poor Health (Plan Choices) & Prescriptions for Reform.” Behavioral Science and Policy 3 (1): 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Blendon Robert J., Benson John M., and Hero Joachim O.. 2014. “Public Trust in Physicians—US Medicine in International Perspective.” New England Journal of Medicine 371 (17): 1570–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blewett Lynn A., Rivera Drew Julia A., Griffin Risa, Williams Kari C. W., and Backman Daniel. 2018. “IPUMS Health Surveys: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Version 1.0” IPUMS. https://ipums.org/projects/ipums-health-surveys/d071.v1.0 (accessed March 10, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Brandt Allan M. 1978. “Racism and Research: The Case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.” Hastings Center Report 8 (6): 21–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer Noel T., Chapman Gretchen B., Rothman Alexander J., Leask Julie, and Kempe Allison. 2017. “Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science into Action.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 18 (3): 149–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brot-Goldberg Zarek C., Chandra Amitabh, Handel Benjamin R., and Kolstad Jonathan T.. 2017. “What Does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-Sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (3): 1261–318. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. “Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2017 (BRFSS 2017).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2017.html accessed May 31, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. “Past Seasons Estimated Influenza Disease Burden Averted by Vaccination.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/past-burden-averted-est.html (accessed February 25, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021a. “Results for General Population Influenza Vaccination Coverage.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/interactive-general-population.htm (accessed February 25, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021b. “Weekly Cumulative Doses (in Millions) of Influenza Vaccines Distributed, United States, 2016–2021.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/dashboard/vaccination-doses-distributed.html (accessed February 25, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2010. “Background: The Affordable Care Act’s New Rules on Preventive Care.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/preventive-care-background (accessed February 25, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Amitabh, Flack Evan, and Obermeyer Ziad. 2023. “The Health Costs of Cost-Sharing.” NBER Working Paper 28439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Lisa A., Roter Debra L., Johnson Rachel L., Ford Daniel E., Steinwachs Donald M., and Powe Neil R.. 2003. “Patient-Centered Communication, Ratings of Care, and Concordance of Patient and Physician Race.” Annals of Internal Medicine 139 (11): 907–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick Lisa, Gallo Joseph J., Gonzales Junius J., Hong Thi Vu Neil R. Powe, Nelson Christine, and Ford Daniel E.. 1999. “Race, Gender, and Partnership in the Patient-Physician Relationship.” Journal of the American Medical Association 282 (6): 583–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DellaVigna Stefano, and Pope Devin. 2018. “Predicting Experimental Results: Who Knows What?” Journal of Political Economy 126 (6): 2410–56. [Google Scholar]

- Eichengreen Barry, Aksoy Cevat Giray, and Saka Orkun. 2021. “Revenge of the Experts: Will COVID-19 Renew or Diminish Public Trust in Science?” Journal of Public Economics 193: 104343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson Keith Marzilli, and Sydnor Justin. 2017. “The Questionable Value of Having a Choice of Levels of Health Insurance Coverage.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31 (4): 51–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos Alicia. 2016. “AAMC Report Shows Decline of Black Males in Medicine.” Association of American Medical Colleges News, September 27, 2016. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/aamc-report-shows-decline-black-males-medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Gauchat Gordon. 2012. “Politicization of Science in the Public Sphere: A Study of Public Trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010.” American Sociological Review 77 (2): 167–87. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood Brad N., Carnahan Seth, and Huang Laura. 2018. “Patient–Physician Gender Concordance and Increased Mortality among Female Heart Attack Patients.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (34): 8569–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood Brad N., Hardeman Rachel R., Huang Laura, and Sojourner Aaron. 2020. “Physician–Patient Racial Concordance and Disparities in Birthing Mortality for Newborns.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117 (35): 21194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond Wizdom Powell, Matthews Derrick, Mohottige Dinushika, Agyemang Amma, and Corbie-Smith Giselle. 2010. “Masculinity, Medical Mistrust, and Preventative Health Services Delays Among Community-Dwelling African-American Men.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 25: 1300–08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handel Benjamin R., and Kolstad Jonathan T.. 2015. “Health Insurance for ‘Humans’: Information Frictions, Plan Choice, and Consumer Welfare.” American Economic Review 105 (8): 2449–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handel Benjamin R., and Schwartzstein Joshua. 2018. “Frictions or Mental Gaps: What’s behind the Information We (Don’t) Use and When Do We Care?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 32 1: 155–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HealthDay News. 2021. “Poll: Education Level a Prime Driver of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy.” United Press International, February 27. https://www.upi.com/Health_News/2021/02/27/coronavirus-vaccine-hesitation-education-level/3001614375413. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman James J. 1998. “Detecting Discrimination.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 12 (2): 101–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hester Neil, and Gray Kurt. 2018. “For Black Men, Being Tall Increases Threat Stereotyping and Police Stops.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (11): 2711–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Andrew J., Jones Daniel B., and Woodworth Lindsey. 2023. “Physician-Patient Race-Match Reduces Patient Mortality.” Journal of Health Economics 92: 102821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idan Edna, Xing Anlu, Ivory Javarcia, and Alsan Marcella. 2020. “Sociodemographic Correlates of Medical Mistrust among African American Men Living in the East Bay.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Undeserved 31 (1): 115–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenica Emir, and Gentzkow Matthew. 2011. “Bayesian Persuasion.” American Economic Review 101 (6): 2590–615. [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock Ballington L., Parker Lauren J., Bowie Janice V., Howard Daniel L., Laveist Thomas A., and Thorp Roland J. Jr. 2017. “High Levels of Medical Mistrust Are Associated with Low Quality of Life among Black and White Men with Prostate Cancer.” Cancer Control 24 (1): 72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee David S. 2009. “Training, Wages, and Sample Selection: Estimating Sharp Bounds on Treatment Effects.” Review of Economic Studies 76 (3): 1071–102. [Google Scholar]

- Milkman Katherine L., Beshears John, Choi James J., Laibson David, and Madrian Brigitte C.. 2011. “Using Implementation Intentions Prompts to Enhance Influenza Vaccination Rates.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (26): 10415–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanna Michael G., Ann Marie Navar Pearl Zakroysky, Xiang Qun, Goldberg Anne C., Robinson Jennifer, Roger Veronique L., et al. 2018. “Association of Patient Perceptions of Cardiovascular Risk and Beliefs on Statin Drugs with Racial Differences in Statin Use: Insights from the Patient and Provider Assessment of Lipid Management Registry.” JAMA Cardiology 3 (3): 739–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse Joseph P. 2021. “An Ounce of Prevention.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 35 (2): 101–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol Kristin L., Mallon Kenneth P., and Mendelman Paul M.. 2003. “Cost Benefit of Influenza Vaccination in Healthy, Working Adults: An Economic Analysis Based on the Results of a Clinical Trial of Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Virus Vaccine.” Vaccine 21 (17–18): 2207–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver Mary Beth. 2003. “African American Men as ‘Criminal and Dangerous’: Implications of Media Portrayals of Crime on the ‘Criminalization’ of African American Men.” Journal of African American Studies 7 (2): 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Opel Douglas J., Lo Bernard, and Peek Monica E.. 2021. “Addressing Mistrust About COVID-19 Vaccines among Patients of Color.” Annals of Internal Medicine 174 (5): 698–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pager Devah. 2007. “The Use of Field Experiments for Studies of Employment Discrimination: Contributions, Critiques, and Directions for the Duture.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 609: 104–33. [Google Scholar]

- Petrilli Christopher M., Saint Sanjay, Jennings Joseph J., Caruso Andrew, Kuhn Latoya, Snyder Ashley, and Chopra Vineet. 2018. “Understanding Patient Preference for Physician Attire: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study of 10 Academic Medical Centres in the USA.” BMJ Open 8 (5): 021239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries Tonia. 2016. “The Inversion of Influence.” Edelman, January 18. https://www.edelman.com/post/inversion-of-influence. [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza Paola, and Zingales Luigi. 2013. “Economic Experts versus Average Americans.” American Economic Review 103 (3): 636–42. [Google Scholar]

- Street Richard L., O’Malley Kimberly J., Cooper Lisa A., and Haidet Paul. 2008. “Understanding Concordance in Patient-Physician Relationships: Personal and Ethnic Dimensions of Shared Identity.” Annals of Family Medicine 6 (3): 198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Michael, Oliwa Tomasz, Peek Monica E., and Tung Elizabeth L.. 2022. “Negative Patient Descriptors: Documenting Racial Bias in the Electronic Health Record.” Health Affairs 41 (2): 203–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres Carlos, Ogbu-Nwobodo Lucy, Alsan Marcella, Stanford Fatima Cody, Banerjee Abhijit, Breza Emily, Chandrasekhar Arun G., et al. 2021. “Effect of Physician-Delivered COVID-19 Public Health Messages and Messages Acknowledging Racial Inequity on Black and White Adults’ Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices Related to COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open 4 (7): 2116024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnado-Sullivan Paula, Larzelere Michele, Solek Kaly, Gupta Shalinder, Hatfield Jackson E., Cheema Mohammad H., and Delfino Matthew. 2019. “The Impact of Physician Demographic Characteristics on Perceptions of Their Attire.” Familiy Medicine 51 (9): 737–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R, and Rucker Toni D.. 2000. “Understanding and Addressing Racial Disparities in Health Care.” Health Care Financing Review 21 (4): 75–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.