Abstract

Sensitive detection of two biological events in vivo has long been a goal in bioluminescence imaging. Antares, a fusion of the luciferase NanoLuc to the orange fluorescent protein CyOFP, has emerged as a bright bioluminescent reporter with orthogonal substrate specificity to firefly luciferase (FLuc) and its derivatives such as AkaLuc. However, the brightness of Antares in mice is limited by the poor solubility and bioavailability of the NanoLuc substrate furimazine. Here, we report a new substrate, hydrofurimazine, whose enhanced aqueous solubility allows delivery of higher doses to mice. In the liver, Antares with hydrofurimazine exhibited similar brightness to AkaLuc with its substrate AkaLumine. Further chemical exploration generated a second substrate, fluorofurimazine, with even higher brightness in vivo. We used Antares with fluorofurimazine to track tumor size and AkaLuc with AkaLumine to visualize CAR-T cells within the same mice, demonstrating the ability to perform two-population imaging with these two luciferase systems.

Bioluminescence imaging with luciferases is an essential technique for tracking cells and reporting biological events in preclinical animal models. Luciferases catalyze oxidation of chemical substrates to generate electronic excited states that then relax via photonic emission1. Because bioluminescence does not require excitation light, there is no autofluorescence produced during imaging, and background is generated only by spontaneous substrate emission, which is negligible for commonly used substrates1. As a result, luciferase-based reporters achieve very high signal to background ratios, enabling non-invasive imaging of cells in deep tissues with lower limits of detection than fluorescence2,3.

Since the first use of firefly luciferase (FLuc) and its substrate D-luciferin in mice more than two decades ago4, researchers have attempted to develop brighter bioluminescent enzyme-substrate systems, with recent success. Aka luciferase (AkaLuc) and its substrate AkaLumine, derived from FLuc and D-luciferin respectively, produce ~13 times more detectable light per reporter molecule from intrapulmonary locations5. Other improved bioluminescent systems are based on the highly catalytic blue-emitting luciferase NanoLuc, which uses furimazine (Fz) as its substrate6. In one case, the reporter Antares consists of two copies of the cyan-excitable orange fluorescent protein CyOFP1 fused to NanoLuc7. In another case, red enhanced Nano-lantern (ReNL) consists of two copies of the orange fluorescent protein dTomato fused to NanoLuc8. In these proteins, Förster resonance energy transfer (RET) from the NanoLuc reaction product to CyOFP1 or dTomato shifts a large fraction of emission to wavelengths above 600 nm, which transmit through mammalian tissue more efficiently9. Antares has recently been further developed into Antares2, which uses diphenylterazine (DTZ), a furimazine derivative with red-shifted emission7,10.

Further improvements to NanoLuc-based enzyme-substrate systems such as Antares-Fz would be of widespread utility for two reasons. First, FLuc and NanoLuc are orthogonal in their substrate specificity, due to their unrelated structures and enzymatic mechanisms, and thus can be used to image two biological processes or cell populations in the same animals11–13. Improving NanoLuc substrates would allow reporters such as Antares to reach higher levels of in vivo sensitivity, which would be useful for dual bioluminescence imaging experiments with FLuc-based reporters, regardless of the relative brightness of the two systems. Second, unlike insect-derived luciferases such as FLuc and its derivatives, NanoLuc does not require ATP as a cofactor14. This uniquely allows for applications of NanoLuc-based systems in the extracellular space, e.g. the detection of cell surface receptors by application of NanoLuc-fused ligands15,16 or the detection of antigens with NanoLuc-conjugated antibodies17.

We hypothesized that further enhancement of NanoLuc-based in vivo bioluminescence reporting should be possible. For example, furimazine is poorly soluble in aqueous solutions whereas D-luciferin can be dissolved to high concentrations in buffered saline. Thus, while D-luciferin is routinely administered by intraperitoneal (IP) injection at 150 mg/kg (13 μmol for a 25-g mouse) to reach concentrations that saturate FLuc18, the poor aqueous solubility of furimazine limits maximum dosage to only 1.3 μmol in the previously published polyethylene glycol-300 (PEG-300)-based aqueous formulation7, while a dosage of 0.25 mg/kg (0.016 μmol for a 25-g mouse) in PBS has been routinely administered11. Furthermore, lipophilic compounds bind to plasma proteins and concentrate within adipose tissues, increasing their volumes of distribution and lowering their effective concentrations in extracellular fluid. Indeed, while Antares can produce >100-fold more photons than FLuc in cells incubated with saturating concentrations of substrates, its advantage in vivo is reduced to ~three-fold of FLuc due to the limited amount of furimazine that can be administered7,10. Thus, improving the solubility of furimazine could increase the sensitivity of NanoLuc-based bioluminescence imaging in animals.

Here, we report the development of new NanoLuc substrates with greater solubility and higher maximum possible doses in vivo. When administered by IP injection, the new substrates produced an approximately four- to five-fold improvement in Antares brightness from deep-tissue locations compared to furimazine at maximal doses. Antares with the new substrates also exhibits comparable performance to AkaLuc with AkaLumine for deep tissue imaging in live mice. We name the two most optimal new substrates hydrofurimazine (HFz) and fluorofurimazine (FFz). Compared to furimazine, photon generation from HFz in vivo is both more intense and more prolonged, allowing Antares-based reporters to track dynamic events in vivo at high temporal resolution and for extended periods of time. FFz exhibits even higher peak and integrated brightness than HFz in vivo. We demonstrate that Antares with FFz and AkaLuc with AkaLumine can be used in the same subjects for dual bioluminescence imaging.

Results

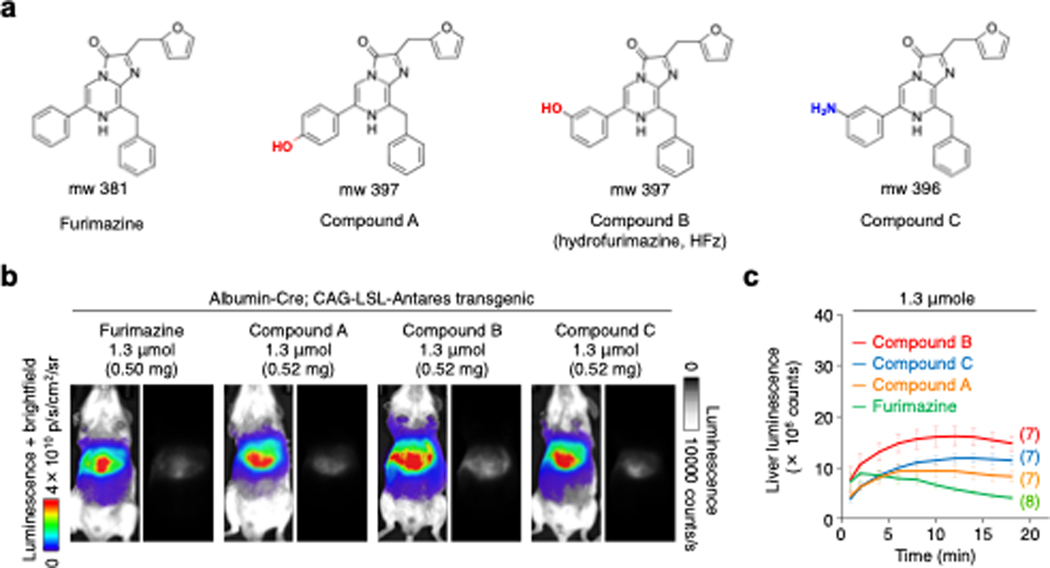

As the brightness of in vivo NanoLuc-based reporters such as Antares is likely constrained by the maximum injectable amount of substrate, we set out to create NanoLuc substrates with improved solubility. NanoLuc is derived from Oplophorus gracilis luciferase, which uses coelenterazine as its natural substrate, as characterized by Shimomura19. Coelenterazine features a phenol group at the C6 position of the central imidazopyrazinone ring, whereas furimazine and DTZ contain the more hydrophobic phenyl group. We found furimazine to be more soluble than DTZ in the PEG-300-based aqueous formulation7, so we selected furimazine as a starting point for synthesizing new substrates with improved solubility. Specifically, we synthesized derivatives of furimazine with polar substituents on the phenyl ring (Supplementary Fig. 1), creating a 4ʹ-hydroxy substituent (designated compound A), a 3ʹ-hydroxy substituent (compound B), and a 3ʹ-amino substituent (compound C) (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Figs. 2–4). These compounds were indeed more soluble than furimazine (Extended Data Fig. 1a), reaching at least 8.8 mM vs. 2.8 mM for furimazine in the PEG-300-based formulation. Interestingly, compound B was noticeably more soluble than compounds A and C, dissolving well at a concentration of 28 mM.

Figure 1. In vivo screening of novel furimazine analogs.

(a) Structures of bioluminescent substrates. (b) Bioluminescence images of mice doubly hemizygous for albumin-Cre and CAG-loxP-stop-loxP-Antares (CAG-LSL-Antares) genes, which express Antares protein in the liver. Representative results with peak bioluminescence from each substrate injection were shown in two images. Left, linear pseudocolored representations of bioluminescence intensity overlaid on bright-field images, which is the more commonly used display format for bioluminescence in animals. Right, raw grayscale images, allowing intuitive assessment of relative brightness and visualization of anatomical features. This display format, while standard for fluorescence imaging, is rarely used for bioluminescence in animals. Exposure 1 s, binning 1, f-stop 8. (c) Mean bioluminescence intensity over time for each amount of injected substrate. Error bars, standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Numbers of mice are indicated in parentheses.

We next characterized the new compounds as substrates for Antares. The emission spectrum of Antares, which comprises two peaks representing photons from the reaction product and post-RET emission from CyOFP1, were not significantly altered with the new substrates (Extended Data Fig. 1b). This finding indicates that the new substrates emitted with similar wavelength distributions as furimazine and, since donor quantum yield affects RET efficiency, that quantum yields of NanoLuc with the new substrates are also not significantly changed. Substrate titration assays revealed that compound B has similar Vmax and thereby kcat and higher kcat/KM compared to furimazine (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Light output decreased more rapidly over time with compound A than with the other substrates (Extended Data Fig. 1d), which suggests specific inhibition of NanoLuc by the product of compound A oxidation. Compared to furimazine, the new substrates also showed improved stability in serum (Extended Data Fig. 1e), a desirable characteristic for use in mice.

To facilitate comparisons between substrates or between bioluminescent reporters in mice, we constructed an Antares gene whose transcription from a constitutive promoter was dependent on Cre recombinase. This gene was integrated into the H11 safe-harbor locus by φC31-mediated integration into an attP site previously inserted in that locus20. We could then introduce tissue-specific Cre drivers through genetic crosses. This experimental design reduces the number of experimental variables during comparisons between substrates, as reporters are driven by identical genetic elements, and are expressed in a stable long-term manner.

To compare new substrates and furimazine brightness in deep tissues, we first expressed Antares in the liver by creating mice doubly hemizygous for an albumin-Cre gene and the CAG-LSL-Antares. We then administered 1.3 μmol of each substrate by IP injection in the previously used vehicle, which uses PEG-300 as the primary solubilizing agent7. We observed that peak light production was highest with compound B, followed by compound C and then compound A or furimazine, with the latter two demonstrating similar peak light levels (Fig. 1b). All three new substrates exhibited a slower onset to peak and clearly prolonged duration of bioluminescence compared to furimazine. Consequently, compound A produced more total integrated output even though its peak output was similar to that of furimazine (Fig 1c). As the new substrates yield more signal in vivo despite performing similarly to or worse than furimazine in vitro, these results suggest the improved output is due to differences in bioavailability.

We next quantified light production in mice from Antares with the two most soluble substrates, compounds B and C. The maximum amount of compound C that could be administered IP in the PEG-300 formulation was 4.2 μmol due to an injection volume limit of ~0.5 mL, whereas it was possible to inject up to 13.3 μmol of compound B because of its higher solubility (Extended Data Fig. 1a). 13.3 μmol of compound B produced similar brightness as 4.2 μmol (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b), establishing 4.2 μmol as a saturating dose for compound B. Specifically, compound B at saturating dose produced approximately four-fold more light than the maximum dose of furimazine. To further validate the performance of the new substrates in vivo, we performed a second set of imaging experiments in transgenic mice expressing Antares in the kidney using nestin-Cre/CAG-LSL-Antares mice, as nestin is known to be expressed during kidney development. These experiments confirmed that injecting higher amounts of the new substrates improved light production over furimazine (Extended Data Fig. 2c-f).

Given its high brightness and aqueous solubility, we selected compound B, which we named hydrofurimazine (HFz), for further characterization in vivo. AkaLuc-AkaLumine, Antares2-DTZ, and LumiScarlet-8pyDTZ are other recently developed luciferase-luciferin pairs with in vivo performance superior to FLuc with D-luciferin. To assess how well Antares-HFz performs in vivo relative to these bioluminescent systems, we expressed Antares, Antares2, LumiScarlet, or AkaLuc in nude mice by hydrodynamic transfection of plasmid DNA. After 18 hours, the mice were injected IP with optimal doses of substrates and imaged (Fig. 2a,b, Extended Data Fig. 3). Specifically, we injected 4.2 μmol of HFz, the maximum soluble doses of DTZ and 8pyDTZ (1 and 4 μmol), and the recommended dose of AkaLumine for AkaLuc (3 μmol)5. Time-lapse imaging revealed that all luciferase-substrate pairs were similar in peak intensity (Fig. 2b,c). Thus, the increased light production from Antares conferred by HFz allows NanoLuc-based bioluminescence systems to match that of the orthogonal AkaLuc-AkaLumine system. Antares-HFz also exhibited uniquely sustained emission (Fig. 2b,d), allowing its integrated signal over 20 min to significantly exceed that of Antares2-DTZ (Fig. 2e). Integrated signal over 20 min also appeared higher than that of LumiScarlet-8pyDTZ, but narrowly missed statistical significance after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Fig. 2b,e). A difference in integrated signal may be more apparent with longer integration times.

Figure 2. In vivo characterization and application of compound B (HFz).

(a) Representative results of bioluminescence imaging in J:NU mice hydrodynamically transfected with plasmids encoding Antares, Antares2, LumiScarlet or AkaLuc. Maximal amounts of corresponding luciferins were injected IP. Images from the time point of maximal brightness are displayed with the same intensity scaling. Exposure 1 s, binning 1, f-stop 1.2. (b) Mean signal intensity in the liver over time for luciferase-luciferin systems. Error bars, standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Numbers of mice are indicated in parentheses. (c) Mean peak signal intensities of the three systems, calculated from the peak intensities of individual mice. (d) Signal persistence, quantified in each mouse as intensity at 20 min divided by peak intensity. (e) Total integrated signal, quantified from the sum of signals from 0 to 20 min for individual mice. (c-e) Error bars, s.e.m. P values, two-tailed Welch’s unpaired t test. Asterisks, statistically significant differences indicated by P values below 0.0167 (for an overall alpha level of 0.05 for three comparisons by the Bonferroni method). (f) Bioluminescence imaging of calcium in mouse liver with Orange CaMBI and extended-release compound B (HFz). Emission from Orange CaMBI in one region of the liver reveals calcium oscillations. Raw luminescence was corrected for substrate decay by fitting to a monoexponential decay curve. (g) Top, bioluminescence images at three time points showing localized changes in CaMBI activity. Below, bioluminescence intensity within two regions as indicated in the bioluminescence images. Arrows indicate the time points corresponding to the three images. Results in (f-g) were repeated independently two times with similar results.

Although HFz already demonstrates slower signal decay in vivo compared to previous substrates, further prolonging light production would be useful for time-lapse imaging of dynamic bioluminescent reporters. Aqueous solutions of poloxamer-407 (P-407) are liquid at room temperature but gel at body temperature, and can be used to create extended-release IP formulations of small-molecule drugs21. Conveniently, mice can be given P-407 for months (12 mg IP every 3 days) without affecting body weight, morbidity, or mortality22. We found that after solubilizing 4.2 μmol (1.7 mg) of substrate with 12 mg P-407 in ethanol and evaporating the ethanol, the lyophilized cakes of P-407 with HFz, but not furimazine or compound C, could be resolubilized with 0.48 mL of water (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Mice injected daily for three days with this aqueous solution of HFz and P-407, or P-407 alone, were similar to uninjected mice in body weight or complete blood counts (Supplementary Table 1). On a comprehensive metabolic panel, the only consistent abnormality compared to uninjected controls was hypercholesterolemia (Supplementary Table 1), a previously described effect of P-407 that reverses upon discontinuation22. In addition, no abnormalities were found on gross examination of organs or on histology of the liver, lung, and kidney (Extended Data Fig. 4b).

We compared the P-407 formulation of HFz with the earlier PEG-300-based formulation for signal intensity and duration in mice. Upon IP administration to mice expressing Antares in the liver, the two formulations produced similar peak brightness, but light output with the P-407-based formulation peaked later and appeared more sustained (Extended Data Fig. 4c, d). Thus P-407, in addition to allowing lyophilization and water-reconstitution of HFz, also conferred sustained-release kinetics for NanoLuc-based bioluminescence imaging in vivo without sacrificing peak brightness.

This sustained-release formulation of HFz should be useful for bioluminescence imaging of physiological events in vivo over long time courses. To determine if this is the case, we performed extended imaging of the Antares-based, orange-emitting, calcium-modulated bioluminescent indicator (Orange CaMBI) in mouse liver. Orange CaMBI has been used to non-invasively report calcium oscillations in the liver, but previous imaging sessions using furimazine were limited to 6 min in duration 23. Using sustained-release HFz, orange CaMBI signals were sufficiently bright to be seen by the naked eye in the dark for >1 h, and allowed time-lapse imaging with <1 s exposures using a consumer-grade digital camera. We observed Orange CaMBI reaching peak brightness 24 min after substrate injection, dropping to half of its peak brightness ~60 min after injection with monoexponential kinetics. Vasopressin administration was followed by oscillations in Orange CaMBI signals within liver regions with periods of ~45 s over a 45 min window (Fig. 2g), confirming previous results using furimazine over shorter time frames23. The combination of brightness and signal duration produced by HFz allowed calcium oscillations to be visualized with fine temporal resolution for >1 h after substrate injection (Fig. 2f). Thus, extended-release HFz enables bioluminescence imaging in vivo over long time courses, which should be useful for studying dynamic physiological events in real time.

As demonstrated by HFz and compound C, improving solubility and bioavailability is a promising strategy for engineering new substrates derived from furimazine. We next explored other strategies to further improve their in vivo performance. In medicinal chemistry, fluorination on a target molecule is often adopted in drug design to alter potency, membrane permeability, metabolism and pharmacokinetics properties24. We thus synthesized derivatives of HFz and compound C with fluorine substitution on the phenyl ring (Supplementary Fig. 1), creating two new substrates with 2ʹ-fluoro substituents (designated compound D and E) (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Figs. 5–6). In vitro, these fluorinated compounds do not alter the emission spectrum of Antares (Extended Data Fig. 5a), while exhibiting improved Vmax and thereby kcat versus furimazine (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 5b), and retaining the improved stability in serum observed with HFz and compound C (Extended Data Fig. 5c). More importantly, when 1.3 μmol of each substrate in the PEG-300 formulation was administered by IP injection, both compound D and E showed brighter signal outputs than HFz in mouse liver. Compound E in particular showed an approximately three-fold improvement (Fig. 3b, c). As compound E yields greater improvement in vivo than in vitro, these results suggest the improved light output is likely due to differences in both enzyme utilization and bioavailability brought by fluorination.

Figure 3. In vitro characterization and in vivo screening of novel fluorinated furimazine analogs.

(a) Left, structures of fluorinated furimazine analogues. Right, determination of kinetic parameters of relative kcat and absolute KM for Antares with each substrate. As the same concentration of purified Antares was used with each substrate, kcat relative to furimazine can be calculated from the relative asymptotic luminescence (Vmax) values. Centre values, mean. Error bars, standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). N = 3 independent experiments. (b) Bioluminescence imaging results in mice doubly hemizygous for albumin-Cre and CAG-loxP-stop-loxP-Antares (CAG-LSL-Antares) genes, which express Antares protein in the liver, at 6–8 weeks of age, and injected with indicated amount of fluorinated furimazine analogues. Representative results with peak bioluminescence were shown in two images, with conditions of experiments and data processing same as that of Fig 1b. Exposure 1 s, binning 1, f-stop 8. (c) Mean bioluminescence intensity over time for each amount of injected substrate. Error bars, s.e.m.. Numbers of mice are indicated in parentheses.

Encouraged by the improved performance of singly fluorinated compounds over their non-fluorinated analogues, and by the brighter signal of compound E over compound D, we introduced another fluorine substitution on a different phenyl ring of compound E, leading to compound F (Supplementary Fig. 7) (Fig. 3a). Compared to compound E, compound F displays a higher Vmax and thereby kcat for Antares in vitro, and a further increase in peak signal when administered at 1.3 μmol in vivo (Fig. 3b, c, Extended Data Fig. 5a-c). We then characterized the solubility of compounds E and F, finding them to be as soluble as the parent compound C, reaching at least 8.8 mM in the PEG-300-based formulation (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Interestingly, compound F was especially soluble in the P-407 formulation, dissolving well at a concentration of 8.8 mM, while compound E and C could not be solubilized at this concentration. Unexpectedly, however, compound F displayed a shorter in vivo bioluminescence half-life in the P-407 than PEG-300 formulation. Regardless, as compound F produced the most light per mole both in vitro and in vivo, and was the most soluble fluorinated compound, we named it fluorofurimazine (FFz) and selected it for further characterization.

We first established the optimal dosage and vehicle for FFz administration in mice. An injection of 1.3 μmol FFz produced more light from the mouse liver than 4.2 μmol HFz (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b), while requiring a smaller injection volume of only 0.15 mL compared to 0.48 mL. No abnormalities in body weight, blood chemistry, or histology were found in mice injected with 1.3 μmol FFz in P-407 daily for three days. A dose of 4.2 μmol of FFz produced more light than 1.3 μmol (Extended Data Fig. 6b), but was associated with weight loss, abnormal blood chemistry (Supplementary Table 2), and histologic evidence of kidney toxicity and hepatic subcapsular degeneration (Extended Data Fig. 6c, Table 3). These results indicate that FFz can be safely administered at a dose of 1.3 μmol in P-407, at which it produces more light than 4.2 μmol HFz in mice.

As lack of spontaneous emission by substrates is crucial for the high signal-to-background ratio of bioluminescence imaging, we directly tested the level of spontaneous emission from furimazine, HFz, or FFz in vivo. We injected each substrate into wild-type mice not expressing any reporter, allowing us to assess true background in the known absence of enzyme. All tested NanoLuc substrates, including furimazine, HFz and FFz, and Fluc substrate D-luciferin, produced negligible signals after injection under sensitive imaging settings, while AkaLumine produced clear background signal in the liver (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig 7a-b).

Figure 4. In vivo characterization and application of fluorofurimazine (FFz).

(a) Background luminescence for the novel substrates, D-luciferin and Akalumine in unshaved white fur coated mice. The experiment was repeated independently two times with similar results. (b) Representative results of bioluminescence imaging in J:NU nude mice hydrodynamically transfected with plasmids encoding Antares or AkaLuc. Maximal amounts of corresponding luciferins were injected IP. Images in each type are displayed with the same intensity scaling and represent the time point of maximal brightness. Exposure 1 s, binning 1, f-stop 1.2. (c) Mean signal intensity in the liver over time for luciferase-luciferin systems. Error bars, standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Numbers of mice are indicated in parentheses. (d) Left, mean peak signal intensities of each system. Right, Total integrated signal, quantified from the sum of signals from 0 to 20 min for individual mice. Error bars, s.e.m., P values, two-tailed Welch’s t test. (e) In vitro assay of expression of luciferase in transgenic HeLa cell lines. N = 3. (f) Representative results of bioluminescence imaging in J:NU nude mice subcutaneously implanted with 103 HeLa cells stably expressing both Antares and AkaLuc luciferases. Exposure 60 s, binning 2, f-stop 1.2. (g) Left, mean peak signal intensities. Right, total integrated signal, quantified from the sum of signals from 0 to 20 min for individual mice. N = 9. Error bars, s.e.m.. P values, two-sided Welch’s unpaired t test.

We next assessed how well Antares with FFz compared to AkaLuc with AkaLumine. In hydrodynamic transfection experiments, Antares with 1.3 μmol FFz tended to produce more brightness than AkaLuc with AkaLumine, although the effect was not statistically significant with the observed variance and the number of mice tested (Fig. 4b-d, Extended Data Fig. 7c). Kinetics of light production were similar between these two systems (Fig. 4c). To more tightly correlate expression between Antares and AkaLuc, we also created HeLa cells stably expressing both proteins from a bicistronic gene using a P2A sequence, thereby translating the same number of mRNA molecules. In cells, the ratio of AkaLuc signal over Antares signal was higher in HeLa[Antares-P2A-AkaLuc] cells than in HeLa[AkaLuc-P2A-Antares], unexpectedly (Fig. 4e). We thus selected HeLa[Antares-P2A-AkaLuc] cells for in vivo experiments to obtain as much signal from AkaLuc as possible. After implanting 1000 cells subcutaneously in the left thoracolumbar region, we imaged mice using FFz and AkaLumine sequentially (Fig. 4f). Half the mice were imaged first with FFz and then, after signals decayed, with AkaLumine, while the other mice were imaged in the reverse order. As the order of injection did not noticeably affect results, samples were combined for analysis. Antares with FFz exhibited three-fold more bioluminescence than AkaLuc with AkaLumine, quantified as either peak intensity or integrated signal (Fig. 4g, Extended Data Fig. 7d). AkaLumine-injected mice exhibited substantial bioluminescence from the upper abdomen (Fig. 4f), consistent with the background liver signal observed in mice injected with AkaLumine in the absence of AkaLuc expression (Fig 4a, Extended Data Fig. 7b).

Luciferases are commonly used to track the location and growth of tumors in mice. We thus tested the ability of Antares and AkaLuc to report the growth of engrafted EW8 Ewing sarcoma cells in nod scid mice. We transfected EW8 cells with plasmids expressing Antares or AkaLuc-P2A-CyOFP, where the CyOFP allowed us to ascertain how similarly the two luciferases were expressed. Despite Antares containing two copies of CyOFP, we observed similar brightness distributions in the CyOFP channel for the stably expressing population (Extended Data Fig. 8a), indicating the AkaLuc-P2A-CyOFP mRNA was translated as well or better than the Antares mRNA. We then selected for high stable expression of both luciferases using the same range of CyOFP values, and created xenografts in nod scid mice (Extended Data Fig. 8a–c). Unexpectedly, the EW8[Antares] tumors produced >100-fold more signal after FFz injection than the EW8[AkaLuc] tumors did after AkaLumine infection (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c). In addition, the EW8[Antares] tumors exhibited increasing bioluminescence over 6 days in 6 of the 9 mice imaged, whereas EW8[AkaLuc] tumors showed a drop in signal in all the mice imaged (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c). We also observed decreasing bioluminescence over time from engrafted MG63.3 osteosarcoma cells stably expressing AkaLuc in NSG mice administered native T cells (Extended Data Fig. 9a-d). The reasons for decreasing AkaLuc signals are unclear, but they could indicate effects of AkaLuc on long-term cell viability, decreasing AkaLuc expression, or decreasing access of AkaLumine to the tumor cells due to stroma formation.

The ability to image distributions of cancer cells and immune cells in the same subjects would be extremely useful in mouse models of immunotherapy. Changes in tumor size and changes in immune cell number and distribution can then be visualized in the same subjects, providing clearer evidence for immune-mediated effects than imaging of either cell type alone. Moreover, sensitive reporters could shed light on dynamic responses of immune cells such as proliferation and trafficking. In mice bearing Antares-expressing MG63.3 cells (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b), we administered either native T cells expressing AkaLuc or T cells co-expressing AkaLuc and B7-H3 CAR, which targets MG63.3 cells. Bioluminescence from the Antares-expressing MG63.3 tumors increased over time in mice treated with the native T cells (Fig. 5b, Extended Data Fig. 10d) as expected, unlike the decreasing signals we had observed from AkaLuc-expressing MG63.3 tumors. In contrast, bioluminescence from the Antares-expressing MG63.3 tumors in mice treated with the AkaLuc- and CAR-expressing T cells decreased nine days following T cell administration (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 10c). This resulted in significantly lower Antares signals in mice treated with CAR-T cells than mice treated with native T cells (Fig. 5c-d), confirming that tumor regression was CAR-mediated. Interestingly, AkaLuc imaging revealed both native and CAR-expressing T cells to colocalize with the tumor (Fig. 5a-b, Extended Data Fig. 10c-d), suggesting that specific antigen recognition, and not simply T cell presence in the tumor, is required for an anti-tumor effect. Taken together, these results establish the ability of Antares and AkaLuc to be used for orthogonal imaging of two cell populations in vivo, and demonstrate how dual luciferase imaging can be used to reveal the relationship between T cell distributions and tumor responses within individual mice.

Figure 5. Dual bioluminescence imaging of tumor xenografts and CAR-T cells in vivo.

(a-b) Bioluminescence imaging in NSG mice engrafted with Antares-expressing MG63.3 tumors in one leg (at day 0) and intravenously injected with AkaLuc-expressing B7-H3 CAR-T cells (a) or native T cells (b) (at day 14). Maximal amounts of individual luciferins were injected IP on the indicated days. (c) Normalized intensities of individual mice. (d), mean signal intensity of tumor over time, normalized to day 9 post tumor cells injection (first time point). N = 5. Error bars, s.e.m.. P value, two-tailed Welch’s unpaired t test.

Discussion

In this study, we developed new substrates for NanoLuc-based bioluminescent reporters that are more water-soluble than furimazine. We demonstrate that these new substrates improve the effective brightness of the NanoLuc-based Antares reporter in vivo. One specific substrate, hydrofurimazine (HFz), can be dosed to saturating concentrations by simple intraperitoneal injections. Antares with HFz produces four-fold higher brightness than a saturating dose of furimazine in Antares-expressing transgenic mice, and displays comparable brightness and superior signal duration than AkaLuc with AkaLumine or Antares2 with DTZ. We created a formulation for HFz that allows dry storage and rapid reconstitution with water, demonstrates low toxicity in mice, and exhibits extended release properties in vivo. With this extended-release formulation, Antares produced a highly persistent signal with half-life of >30 min. The intensity and duration of this signal allowed for non-invasive visualization of calcium oscillations in the liver with high temporal resolution for over an hour. Another substrate, fluorofurimazine (FFz), displays even higher molar brightness than HFz, allowing lower IP injection volume for long-term studies. Antares with FFz at optimal dose produces three-fold higher brightness than AkaLuc with AkaLumine in a cell implantation mouse model. Together with the orthogonal AkaLuc system, Antares with FFz enabled imaging distributions of cancer cells and immune cells in the same subjects in mouse models of immunotherapy. Thus, Antares with extended-release HFz will be especially useful in experiments visualizing dynamic events over time, while FFz will be most useful for detecting small numbers of cells.

Our results demonstrate the importance of substrate solubility and bioavailability as practical limitations to bioluminescence imaging in vivo. We found that introducing a hydrophilic entity (hydroxy- or amino-) onto the phenyl group of furimazine resulted in improved substrate solubility and bioavailability while preserving utilization by NanoLuc. Antares with the resulting substrate, HFz, produced similar peak and integrated bioluminescence as AkaLuc with AkaLumine upon IP injection. As demonstrated by FFz, fluorination of the phenyl and benzyl rings further improves in vivo brightness. While FFz produces approximately three-fold more photons per mole than HFz in mice, it is only 1.1-fold brighter in vitro, suggesting the in vivo improvement is due to better bioavailability.

Our study also demonstrates how transgenic expression of reporters enables rapid substrate screening. The coefficient of variation in measurements of HFz brightness was lower when Antares was expressed in the liver by transgenesis (~30%) than when it was expressed by hydrodynamic transfection (~71% over all injections). As the route of substrate administration was the same in both sets of mice, this demonstrates that variability in reporter expression after hydrodynamic transfection dominates over variability in substrate supply by IP injection. This is not surprising, as the process of hydrodynamic injection is inherently variable due to differences in vascular volume and structure between mice26, and sensitive to trial-to-trial differences in the difficult tail vein injection procedure. Stable expression from the same genomic locus eliminates the above sources of variability present in transient transfection, and thus allows for rapid testing of different substrates with smaller numbers of mice. We note, however, that our results in transgenic mice may have underestimated the per-molecule performance of Antares versus FLuc due to lack of cDNA optimization. FLuc was encoded by the Luc2 gene with cryptic transcription factor sites removed and codon usage optimized for mammalian expression, which produces 4- to 12-fold more FLuc in mammalian cells than the non-optimized synonymous Luc+ gene27. In contrast, the Antares gene has not undergone any coding sequence optimization. In addition, the Luc2 gene was preceded by a Kozak sequence whereas the Antares gene was not. In the future, similar optimizations to the Antares gene could be introduced for a fairer comparison.

Whether furimazine-like substrates show spontaneous light production in vivo has recently been questioned5. Our results conclusively demonstrate that Antares substrates on their own do not spontaneously produce light in vivo. Our testing method was to simply inject substrates into mice not expressing any luciferase. This straightforward approach had also been used to demonstrate minimal spontaneous emission from DTZ in vivo10. However, some confusion has arisen from observations that injection of Antares2-expressing cells followed by DTZ produced widespread luminescence throughout the body, while injection of AkaLuc-expressing cells followed by AkaLumine produced luminescence at only defined sites5. A recent study has provided a clear explanation for these findings28. When Antares2-expressing cells are injected, dying cells release active Antares2 into the bloodstream, which is active because Antares2 does not require any cofactors to catalyze oxidation of its substrates. Thus, testing for spontaneous light production from furimazine-related substrates should be performed by injecting substrates into mice that do not express a NanoLuc-based reporter anywhere in the body. In contrast, because AkaLuc requires ATP, which is absent in blood, and because AkaLuc is also inactivated by plasma proteins, lysis of AkaLuc-expressing cells does not result in bioluminescence from the bloodstream. This difference in ATP dependence between luciferases should be considered when designing experiments.

Our results suggest several avenues for future exploration. First the performance of furimazine analogs for bioluminescence reporting in the brain would be interesting to investigate. In preliminary work, we have observed that Antares with our newly reported furimazine derivatives is as bright or brighter in the brain than FLuc with luciferin. Second, the brightness of NanoLuc-based systems in animals could be further improved. As demonstrated by the development of AkaLuc or Antares2, NanoLuc could be evolved to improve its utilization of new substrates. In particular, higher brightness is possible if the NanoLuc domain within Antares can be evolved to catalyze light production from HFz or FFz with faster kinetics or higher quantum yield. Alternatively, effective brightness in mammals can be improved by increasing the fraction of total emission above 600 nm, which is currently only ~50% for Antares with HFz or FFz. Substituting a RET acceptor for NanoLuc with emission more red-shifted than CyOFP1 could thus further improve brightness in vivo.

In summary, HFz and FFz enable sensitive bioluminescence imaging for either prolonged light production of high sensitivity. Notably, existing NanoLuc-based reporters, including those in cell lines and transgenic mice, can benefit immediately these improved substrates without modification. Prolonged light production with HFz makes it the optimal substrate for dynamic reporters such as CaMBI, while the intensity of light production with FFz makes it well suited for tasks where sensitivity is important such as visualizing tumor growth, viral spread, or gene expression. Finally, Antares with FFz and AkaLuc with AkaLumine enable imaging of two biological entities in the same animal subjects with similarly high sensitivity. By enabling experiments on the interactions between immune and cancer cells, as we have demonstrated here, or between immune cells and pathogens, dual bioluminescence imaging with high sensitivity is likely to have widespread utility in biomedical research.

Methods

Synthetic procedures.

In general, substrates were synthesized using organic synthetic methodology as previously described29. Specific reaction conditions and analytical results are described below.

Tert-butyl 2-diazo-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acetate (compound 2 in Supplementary Scheme. 1a).

To a solution of 4-methylbenzenesulfonyl azide (29.1 g, 147 mmol) in THF (300 mL) at 0 °C was added sodium hydride (5.9 g, 147 mmol, 60% oil dispersion) in ~1 g batches. tert-butyl 2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acetate (31.0 g, 123 mmol) was added dropwise over 30 min. The mixture stirred for 1 h at 0°C and 2 h at room temperature. A mixture of ether and ice water was prepared in 2 L beaker and the reaction mixture was carefully added with stirring. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ether. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to afford the desired product (32.9 g, 96%) as a yellow mobile oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.32 – 4.09 (m, 4H), 1.51 (s, 9H), 1.38 (td, J = 7.1, 0.8 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.56 (d, J = 12.1 Hz), 128.06 (d, J = 323 Hz), 83.02, 63.44 (d, J = 5.7 Hz), 28.25, 16.17 (d, J = 6.9 Hz); HPLC 99.3% (AUC at 254 nm) 5.03 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

5-Bromo-3-(2-fluorobenzyl)pyrazin-2-amine (compound 4b).

To an oven dried flask, acid activated zinc (10.4g, 15 9 mmol) was suspended in THF (40 mL) at rt. 1-(Bromomethyl)-2-fluorobenzene (10.0 g, 52.9 mmol) was added and the suspension was heated to reflux for 1 h. The reaction was cooled to rt and the supernatant was transferred to a flask containing 3,5-dibromopyrazin-2-amine (6.1 g, 24.1 mmol), bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) dichloride (0.84 g, 1.2 mmol), and THF (40 mL). The mixture was heated to 50 °C for 4 h. After cooling, the mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate and water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to afford desired product (3.0 g, 44%) as a light yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.44 – 7.01 (m, 4H), 6.60 (s, 2H), 4.14 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.36, 159.93, 153.65, 142.06, 140.85, 131.88, 131.83, 129.10, 129.02, 124.83, 124.76, 124.72, 124.67, 123.54, 115.66, 115.44, 32.32, 32.29; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C11H9BrFN3 [M + H]+ m/z 282.0037, found 282.0033. HPLC 98.4% (AUC at 254 nm) 7.84 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.02%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((3-benzyl-5-bromopyrazin-2-yl)amino)-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acetate (compound 5a).

To a suspension of 4a (ref. 30) (3.8 g, 14.4 mmol) in dichlorobenzene (30 mL) was added 2 (4.8 g, 17.3 mmol) and rhodium (II) acetate dimer (0.64 g, 1.44 mmol). The mixture was heated to 105 °C for 72 h. After cooling, the mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate, concentrated with celite, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to afford the desired product (5.4 g, 73%) as a brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.05 (s, 1H), 7.38 – 7.21 (m, 5H), 5.27 – 5.19 (m, 1H), 5.01 (dd, J = 21.2, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.21 – 3.83 (m, 6H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 1.24 (dt, J = 21.2, 7.0 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.16, 150.27 (d, J = 8.5 Hz), 142.90, 141.66, 135.53, 129.01, 128.74, 127.18, 126.33, 83.11, 63.66 – 63.24 (m), 52.54 (d, J = 146 Hz), 40.38, 27.84, 16.35 – 16.27(m); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C21H29BrN3O5P [M + H]+ m/z 514.1107, found 514.1085; HPLC 98.1% (AUC at 254 nm) 6.59 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((5-bromo-3-(2-fluorobenzyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-2-(diethoxyphosphoryl)acetate (compound 5b).

To a suspension of 5-bromo-3-(2-fluorobenzyl)pyrazin-2-amine 4b (1.3 g, 4.6 mmol) in dichlorobenzene (20 mL) was added 2 (1.9 g, 6.9 mmol) and rhodium (II) acetate dimer (0.20 g, 0.46 mmol). The mixture was heated to 105 °C for 18 h. After cooling, the mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate, concentrated with celite, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to afford the desired product (2.2 g, 88%) as a brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.42 – 7.02 (m, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 8.6, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 5.10 (dd, J = 23.4, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (s, 2H), 4.14 – 3.90 (m, 4H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 1.20 (dt, J = 28.2, 7.0 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.29, 162.25, 159.82, 150.93, 142.85, 141.27, 131.82, 129.35, 125.58, 124.92, 124.26, 115.79, 82.62, 63.44, 54.42, 52.96, 32.31, 27.98, 16.63; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C21H28BrFN3O5P [M + H]+ m/z 532.1007, found 532.1001; HPLC 94.1% (AUC at 254 nm) 6.59 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.02%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((3-benzyl-5-bromopyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylate (compound 6a).

To a solution of 5a (5.4 g, 10.5 mmol) in methanol (100 mL) was added furfural (1.5 g, 15.7 mmol). Tetramethylguanidine (3.6 g, 31.5 mmol) was added dropwise and the reaction stirred at rt for 30 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to afford the desired product (4.0 g, 83%) as a brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.43 – 7.27 (m, 5H), 6.96 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (s, 1H), 6.70 (s, 1H), 6.29 (dd, J = 3.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.16 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (s, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.01, 150.36, 149.59, 143.83, 143.25, 142.11, 136.21, 129.23, 128.81, 128.33, 127.53, 127.31, 112.71, 111.70, 110.84, 81.70, 40.50, 27.91; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C22H22BrN3O3 [M + H]+ m/z 456.0924, found 456.0913; HPLC 94.1% (AUC at 254 nm) 6.86 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((5-bromo-3-(2-fluorobenzyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylate (compound 6b).

To a solution of 5b (4.4 g, 8.3 mmol) in methanol (100 mL) was added furfural (0.95 g, 9.9 mmol). Tetramethylguanidine (2.9 g, 24.8 mmol) was added dropwise and the reaction stirred at rt for 30 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to afford the desired product (2.8 g, 71%) as a light yellow gum. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.42 – 7.13 (m, 4H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 6.79 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (t, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (s, 2H), 1.34 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.25, 162.31, 159.88, 150.93, 150.12, 144.93, 142.39, 141.69, 131.65, 129.25, 127.25, 126.03, 124.84, 117.59, 115.77, 115.56, 114.66, 112.86, 81.01, 27.97; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C22H21BrFN3O3 [M + H]+ m/z 474.0823, found 474.0812; HPLC 98.9% (AUC at 254 nm) 8.98 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.02%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((3-benzyl-5-(4-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylate (compound 7a).

To a solution of 6a (0.24 g, 0.53 mmol) in dioxane (10 mL) was added (4-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)boronic acid (0.20 g, 0.79 mmol), [1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene]-dichloropalladium(II) (0.042 g, 0.053 mmol), and cesium carbonate (1.05 mL, 1.05 mmol, 1.0 M). The mixture was purged with nitrogen and heated to 85°C for 18 h. The reaction was diluted with ethyl acetate and water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to afford the desired product (0.085 g, 27%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.44 (s, 1H), 7.92 – 7.84 (m, 2H), 7.43 – 7.30 (m, 5H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 7.00 – 6.93 (m, 3H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.67 (s, 1H), 6.29 (dd, J = 3.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.16 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H), 4.40 (s, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H), 1.03 (s, 9H), 0.25 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.50, 156.40, 150.75, 148.56, 143.76, 142.91, 142.38, 137.15, 136.40, 130.19, 129.05, 128.88, 128.35, 127.34, 126.99, 120.54, 115.91, 112.08, 111.60, 109.61, 81.51, 40.86, 27.95, 25.76, 18.34; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C34H41N3O4Si [M + H]+ m/z 584.2945, found 584.2941; HPLC 91.6% (AUC at 254 nm) 10.45 min (Zorbax XDB-C8, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((3-benzyl-5-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylate (compound 7b).

To a solution of 6a (0.32 g, 0.70 mmol) in dioxane (10 mL) was added (3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)boronic acid (0.26 g, 1.05 mmol), [1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene]-dichloropalladium(II) (0.060 g, 0.070 mmol), and cesium carbonate (1.4 mL, 1.4 mmol, 1.0 M). The mixture was purged with nitrogen and heated to 85°C for 18 h. The reaction was diluted with ethyl acetate and water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to afford the desired product (0.265 g, 64%) as a dark brown foam. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.46 (s, 1H), 7.60 – 7.55 (m, 1H), 7.51 – 7.46 (m, 1H), 7.43 – 7.31 (m, 6H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (ddd, J = 8.1, 2.6, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (s, 1H), 6.30 (dd, J = 3.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (s, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H), 1.04 (s, 9H), 0.26 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.48, 156.22, 150.70, 149.05, 143.46, 143.00, 142.50, 138.48, 137.11, 136.94, 129.90, 129.80, 129.06, 128.93, 128.17, 127.02, 120.07, 119.01, 117.76, 112.25, 111.64, 110.03, 81.57, 40.89, 27.91, 25.76, 18.29; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C34H41N3O4Si [M + H]+ m/z 584.2945, found 584.2924; HPLC 88.5% (AUC at 254 nm) 10.43 min (Zorbax XDB-C8, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((3-benzyl-5-(3-nitrophenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylate (compound 7c).

To a solution of 6a (0.34 g, 0.75 mmol) in dioxane (10 mL) was added 3-nitrophenyl)boronic acid (0.19 g, 1.12 mmol), [1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene]dichloropalladium(II) (0.061 g, 0.075 mmol), and cesium carbonate (1.5 mL, 1.5 mmol, 1.0 M). The mixture was purged with nitrogen and heated to 85°C for 1 h. The reaction was diluted with ethyl acetate and water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to afford crude product (0.37 g) as an orange solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.88 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.57 (s, 1H), 8.37 – 8.29 (m, 1H), 8.24 (ddd, J = 8.0, 2.0, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.44 – 7.32 (m, 5H), 7.12 (s, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.31 (dd, J = 3.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (s, 2H), 1.42 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.19, 150.44, 149.89, 148.95, 143.28, 142.92, 137.03, 136.63, 131.48, 130.31, 129.76, 129.18, 128.85, 127.60, 127.23, 123.32, 122.81, 120.76, 112.74, 111.73, 110.95, 81.71, 40.85, 27.97; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C28H26N4O5 [M + H]+ m/z 499.1982, found 499.1970. HPLC 70.9% (AUC at 254 nm) 6.45 min (Zorbax XDB-C8, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((3-benzyl-5-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-2-fluorophenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylate (compound 7d).

To a solution of 6a (0.21 g, 0.46 mmol) in dioxane (10 mL) was added (3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-2-fluorophenyl)boronic acid (0.19 g, 0.69 mmol), [1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene]dichloropalladium(II) (0.037 g, 0.046 mmol), and cesium carbonate (0.92 mL, 0.92 mmol, 1.0 M). The mixture was purged with nitrogen and heated to 85°C for 3 h. The reaction was diluted with ethyl acetate and water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to desired product (0.16 g, 58%) as a white foam. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.46 – 8.21 (m, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.52 – 7.32 (m, 5H), 7.32 – 7.23 (m, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.08 – 6.91 (m, 2H), 6.60 – 6.39 (m, 2H), 4.34 (s, 2H), 1.32 (s, 9H), 0.98 (s, 9H), 0.21 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.44, 152.91, 150.49, 150.22, 150.17, 144.62, 143.77, 143.64, 142.47, 140.04, 139.93, 138.44, 137.35, 129.37, 128.90, 127.73, 126.92, 126.43, 126.33, 124.97, 122.56, 121.88, 116.59, 114.15, 112.76, 80.86, 38.79, 27.90, 25.90, 18.49; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C34H40FN3O4Si [M + H]+ m/z 602.2845, found 602.2827; HPLC 96.2% (AUC at 254 nm) 10.51 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.02%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((3-benzyl-5-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylate (compound 7e).

To a solution of 6a (0.24 g, 0.53 mmol) in dioxane (10 mL) was added 2-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolane (0.21 g, 0.79 mmol), [1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene]dichloropalladium(II) (0.042 g, 0.053 mmol), and cesium carbonate (1.6 mL, 1.6 mmol, 1.0 M). The mixture was purged with nitrogen and heated to 85°C for 1 h. The reaction was diluted with ethyl acetate and water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to desired product (0.19 g, 59%) as a yellow foam. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.53 (s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (td, J = 7.5, 6.6, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (td, J = 7.7, 6.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.48 – 7.33 (m, 4H), 7.33 – 7.23 (m, 1H), 7.01 (s, 1H), 6.59 – 6.42 (m, 2H), 4.37 (s, 2H), 1.33 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.34, 153.72, 151.10, 150.80, 150.10, 144.80, 142.80, 140.62, 138.69, 138.26, 135.98, 135.43, 129.38, 128.94, 127.95, 127.84, 127.39, 126.98, 125.93, 125.59, 117.29, 114.45, 112.80, 80.95, 38.70, 27.92; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C28H25FN4O5 [M + H]+ m/z 517.1882, found 517.1865; HPLC 98.5% (AUC at 254 nm) 9.78 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.02%TFA).

Tert-butyl 2-((5-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)-3-(2-fluorobenzyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylate (compound 7f).

To a solution of 6b (2.6 g, 5.5 mmol) in dioxane (50 mL) was added 2-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolane (2.2 g, 8.2 mmol), [1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene]dichloropalladium(II) (0.45 g, 0.55 mmol), and cesium carbonate (13.7 mL, 13.7 mmol, 1.0 M). The mixture was purged with nitrogen and heated to 85°C for 1 h. The reaction was diluted with ethyl acetate and water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in heptane and ethyl acetate to desired product (2.9 g, 97%) as a light brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 8.17 – 7.92 (m, 2H), 7.73 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.41 – 7.13 (m, 4H), 7.06 (s, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (dd, J = 3.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.36 (s, 2H), 1.35 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.36, 162.46, 160.03, 153.67, 150.94, 150.19, 144.95, 141.36, 140.59, 138.68, 135.56, 135.23, 131.66, 129.05, 127.72, 127.38, 125.84, 125.50, 125.24, 124.76, 117.51, 115.66, 115.44, 114.66, 112.86, 80.98, 27.93; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C28H24F2N4O5 [M + H]+ m/z 535.1788, found 535.1790; HPLC 90.9% (AUC at 254 nm) 9.11 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.02%TFA).

2-((3-benzyl-5-(4-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylic acid (compound 8a).

To a solution of 7a (0.080 g, 0.14 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (1 mL) and the reaction stirred at rt for 6 h. The mixture was diluted with toluene and concentrated. The process was repeated twice to afford crude product as an orange oil. ESI MS m/z 528 [M + H]+.

2-((3-benzyl-5-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylic acid (compound 8b).

To a solution of 7b (0.26 g, 0.45 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (1 mL) and the reaction stirred at rt for 18 h. The mixture was diluted with toluene and concentrated. The process was repeated twice to afford crude product as an orange oil. ESI MS m/z 528 [M + H]+.

2-((3-benzyl-5-(3-nitrophenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylic acid (compound 8c).

To a solution of 7c (0.26 g, 0.52 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (1 mL) and the reaction stirred at rt for 1 h. The mixture was diluted with toluene and concentrated. The process was repeated twice to afford crude product as a brown solid. ESI MS m/z 443 [M + H]+.

2-((3-benzyl-5-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-2-fluorophenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylic acid (compound 8d).

To a solution of 7d (0.16 g, 0.26 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (1 mL) and the reaction stirred at rt for 2 h. The mixture was diluted with toluene and concentrated. The process was repeated twice to afford crude product as a brown solid. ESI MS m/z 546 [M + H]+.

2-((3-benzyl-5-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylic acid (compound 8e).

To a solution of 7e (1.7 g, 3.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (50 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (5 mL) and the reaction stirred at rt for 5 h. The mixture was diluted with toluene and concentrated. The process was repeated twice to afford crude product as a brown solid. ESI MS m/z 461 [M + H]+.

2-((5-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)-3-(2-fluorobenzyl)pyrazin-2-yl)amino)-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylic acid (compound 8f).

To a solution of 7f (0.67 g, 1.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (20 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (2 mL) and the reaction stirred at rt for 3 h. The mixture was diluted with toluene and concentrated. The process was repeated twice to afford crude product as a brown foam. ESI MS m/z 479 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-6-(4-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethylene)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(2H)-one (compound 9a).

To a solution of 8a (0.14 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added carbonyldiimidazole (44 mg, 0.27 mmol) and the reaction stirred at rt for 10 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a black solid. ESI MS m/z 510 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-6-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethylene)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(2H)-one (compound 9b).

To a solution of 8b (0.45 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added carbonyldiimidazole (147 mg, 0.91 mmol) and the reaction stirred at rt for 1 hr. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a black solid. ESI MS m/z 510 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-2-(furan-2-ylmethylene)-6-(3-nitrophenyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(2H)-one (compound 9c).

To a solution of 8c (0.52 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added carbonyldiimidazole (168 mg, 1.04 mmol) and the reaction stirred at rt for 30 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a red black solid. ESI MS m/z 425 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-6-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-2-fluorophenyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethylene)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(2H)-one (compound 9d).

To a solution of 8d (0.26 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added carbonyldiimidazole (84 mg, 0.52 mmol) and the reaction stirred at rt for 1 h. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a red brown solid. ESI MS m/z 528 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-6-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethylene)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(2H)-one (compound 9e).

To a solution of 8e (3.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (100 mL) was added carbonyldiimidazole (1.1 g, 6.7 mmol) and the reaction stirred at rt for 2 h. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a red brown solid. ESI MS m/z 443 [M + H]+.

6-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)-8-(2-fluorobenzyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethylene)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(2H)-one (compound 9f).

To a solution of 8f (1.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (20 mL) was added carbonyldiimidazole (0.41 g, 2.5 mmol) and the reaction stirred at rt for 30 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a red brown solid. ESI MS m/z 461 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-6-(4-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound 10a).

To a solution of 9a (0.14 mmol) in dichloromethane/methanol (1:1, 10 mL) at 0°C was added sodium borohydride (26 mg, 0.69 mmol) and the reaction stirred for 10 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as an orange solid. ESI MS m/z 512 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-6-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)phenyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound 10b).

To a solution of 9b (0.45 mmol) in dichloromethane/methanol (1:1, 20 mL) at 0°C was added sodium borohydride (85 mg, 2.3 mmol) and the reaction stirred for 45 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a red brown solid. ESI MS m/z 512 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-6-(3-nitrophenyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound 10c).

To a solution of 9c (0.52 mmol) in dichloromethane/methanol (1:1, 20 mL) at 0°C was added sodium borohydride (98 mg, 2.6 mmol) and the reaction stirred for 30 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a red brown solid. ESI MS m/z 427 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-6-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-2-fluorophenyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound 10d).

To a solution of 9d (0.26 mmol) in dichloromethane/methanol (1:1, 20 mL) at 0°C was added sodium borohydride (49 mg, 1.3 mmol) and the reaction stirred for 15 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a red brown solid. ESI MS m/z 530 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-6-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound 10e).

To a solution of 9e (3.3 mmol) in dichloromethane/methanol (1:1, 20 mL) at 0°C was added sodium borohydride (0.64 mg, 16.7 mmol) and the reaction stirred for 30 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a red brown solid. ESI MS m/z 445 [M + H]+.

6-(2-fluoro-3-nitrophenyl)-8-(2-fluorobenzyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound 10f).

To a solution of 9f (1.3 mmol) in dichloromethane/methanol (1:1, 20 mL) at 0°C was added sodium borohydride (0.12 mg, 3.1 mmol) and the reaction stirred for 30 min. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with HCl (0.1 M). The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to afford crude product as a red brown solid. ESI MS m/z 463 [M + H]+.

8-benzyl-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-6-(4-hydroxyphenyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound A).

To a solution of 10a (0.14 mmol) in methanol (10 mL) was added HCl (1 mL, 6M) and the reaction stirred at rt for 1 h. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in dichloromethane and methanol to afford the desired product (0.040 g, 74% over 4 steps) as an orange solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.84 (s, 1H), 7.60 – 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.46 – 7.38 (m, 3H), 7.37 – 7.29 (m, 2H), 7.29 – 7.20 (m, 1H), 6.95 – 6.87 (m, 2H), 6.34 (dd, J = 3.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (s, 2H), 4.24 (s, 2H); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C24H19N3O3 [M + H]+ m/z 398.1505, found 398.1498; HPLC 97.1% (AUC at 254 nm) 4.45 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

8-benzyl-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-6-(3-hydroxyphenyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound B, hydrofurima-zine).

To a solution of 10b (0.45 mmol) in methanol (20 mL) was added HCl (1 mL, 6M) and the reaction stirred at rt for 1 h. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in dichloromethane and methanol to afford the desired product (0.091 g, 50% over 4 steps) as a brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.47 – 7.38 (m, 3H), 7.37 – 7.21 (m, 4H), 7.18 – 7.04 (m, 2H), 6.90 (ddd, J = 8.1, 2.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (dd, J = 3.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.18 – 6.09 (m, 1H), 4.44 (s, 2H), 4.21 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD); δ 157.79, 149.70, 147.30, 142.15, 139.11, 138.69, 135.47, 134.51, 129.77, 128.96, 128.44, 126.99, 126.79, 121.74, 117.55, 116.58, 113.35, 110.33, 110.29, 107.02, 37.17, 23.14; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C24H19N3O3 [M + H]+ m/z 398.1505, found 398.1503; HPLC 97.1% (AUC at 254 nm) 4.55 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

6-(3-aminophenyl)-8-benzyl-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound C).

To a nitrogen purged solution of 10c (1.0 mmol) in methanol (50 mL) was added Pd/C (40 mg). The mixture was purged with hydrogen and then stirred with 1 atm hydrogen for 4 h at rt. The mixture was purged with nitrogen, filtered over celite, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in dichloromethane and methanol to afford the desired product (0.24 g, 59% over 4 steps) as a dark orange solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.47 – 7.37 (m, 3H), 7.36 – 7.28 (m, 2H), 7.28 – 7.14 (m, 2H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (ddd, J = 8.1, 2.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (dd, J = 3.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.13 (dd, J = 3.2, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (s, 2H), 4.21 (s, 2H); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C24H20N4O2 [M + H]+ m/z 397.1665 found 397.1659; HPLC 94.1% (AUC at 254 nm) 3.87 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

8-benzyl-6-(2-fluoro-3-hydroxyphenyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound D).

To a solution of 10d (0.26 mmol) in methanol (20 mL) was added HCl (1 mL, 6M) and the reaction stirred at rt for 2 h. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and poured into a separatory funnel with water. The two layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layers were combined, dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in dichloromethane and methanol to afford the desired product (0.071 g, 66% over 4 steps) as an orange brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.50 – 7.37 (m, 3H), 7.37 – 7.19 (m, 3H), 7.19 – 6.98 (m, 3H), 6.34 (dd, J = 3.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.13 (dd, J = 3.2, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 4.42 (s, 2H), 4.22 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 2H); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C24H18FN3O3 [M + H]+ m/z 416.1405, found 416.1384; HPLC 99.6% (AUC at 254 nm) 4.45 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

6-(3-amino-2-fluorophenyl)-8-benzyl-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound E).

To a nitrogen purged solution of 10e (3.3 mmol) in methanol (50 mL) was added Pd/C (40 mg). The mixture was purged with hydrogen and then stirred with 1 atm hydrogen for 4 h at rt. The mixture was purged with nitrogen, filtered over celite, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in dichloromethane and methanol to afford the desired product (0.17 g, 12% over 4 steps) as a dark orange solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.67 (s, 1H), 7.48 – 7.37 (m, 3H), 7.37 – 7.20 (m, 3H), 7.10 – 6.90 (m, 2H), 6.83 (s, 1H), 6.34 (dd, J = 3.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.13 (dd, J = 3.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (s, 2H), 4.22 (d, J = 0.9 Hz, 2H); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C24H19FN4O2 [M + H]+ m/z 415.1565 found 415.1546; HPLC 100% (AUC at 254 nm) 4.47 min (Synergi Max-RP, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

6-(3-amino-2-fluorophenyl)-8-(2-fluorobenzyl)-2-(furan-2-ylmethyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one (compound F, fluorofurimazine).

To a nitrogen purged solution of 10f (1.3 mmol) in methanol (20 mL) was added Pd/C (40 mg). The mixture was purged with hydrogen and then stirred with 1 atm hydrogen for 6 h at rt. The mixture was purged with nitrogen, filtered over celite, concentrated, and purified with silica gel chromatography in dichloromethane and methanol to afford the desired product (0.28 g, 51% over 4 steps) as an orange brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.36 – 7.25 (m, 2H), 7.18 – 7.07 (m, 2H), 7.06 – 6.80 (m, 3H), 6.33 (dd, J = 3.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.11 (dd, J = 3.0, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 4.49 (s, 2H), 4.20 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 162.50, 160.06, 154.96, 152.43, 149.24, 147.42, 142.35, 137.77, 135.20, 135.18, 131.70, 131.66, 130.99, 130.97, 129.24, 129.16, 126.51, 125.96, 125.45, 125.41, 124.19, 124.17, 124.15, 124.08, 122.57, 122.41, 119.71, 119.57, 116.55, 114.94, 114.73, 114.18, 114.04, 110.39, 107.21, 32.09, 22.26; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C24H18F2N4O2 [M + H]+ m/z 433.1471 found 433.1454; HPLC 95.0% (AUC at 254 nm) 6.57 min (Luna C8, water/ACN 0.1%TFA).

Spectral analysis of Antares and furimazine analogs.

A single colony of Antares plasmid in KRX E. coli cells was used to inoculate a liquid culture in LB broth, which was grown for 18 h at 37 °C. The culture was then diluted 1:100 into a flask containing 500 mL of Terrific Broth and grown for an additional 4 h at 37 °C. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.1% rhamnose with growth for 65 h at 15 °C. Cells were pelleted and re-suspended in a buffer containing Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.2 mg/mL lysozyme. Cells were lysed by three freeze-thaw cycles. After the final thaw, 0.001U/mL RNAse-free DNase (RQ1, Promega) was added and the sample was incubated on ice for 30 min. The lysate was centrifuged, and the cleared supernatant was loaded to a 1-mL nickel-Sepharose column and then washed with 6 column volumes of buffer. 1-mL fractions were collected and pooled. The pooled fractions were loaded onto a 5-mL Phenyl Sepharose (High Sub) column (GE Healthcare) for hydrophobic interaction chromatography. Fractions were orange coloration were collected, and the pooled fractions were loaded to a 1-mL HiTrap Q column (GE Healthcare) for anion exchange chromatography. Fractions with orange coloration were collected, and the pooled material was quantitated and stored at –20 °C.

To measure emission spectra with furimazine and new substrates, the purified Antares protein was diluted to 100 pM in Dulbecco’s Phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Life Technologies 14190) with 0.01% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Life Technologies). Each substrate was diluted to 25 μM into DPBS with 0.01% FBS. 50 μL of the Antares dilution was combined with 50 μL of each substrate in triplicate. Finally, the spectral profile from 400 to 700 nm was acquired using an Infinite M-1000 luminometer (TECAN).

Enzymatic analysis of Antares and furimazine analogs.

A single colony of Antares plasmid in KRX E. coli was grown for 18 h at 37 °C in LB broth. The overnight culture was diluted 1:100 into a flask containing 50 mL of Terrific Broth and grown for 4 h at 37 °C. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.1% Rhamnose with growth for 24 h at 15°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and then resuspended in 9 mL of 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5 with 0.001U/mL RQ1 DNase (Promega M6101). Cells were lysed by the addition of 1ml of 10× FastBreak Cell Lysis Reagent (Promega V8571) and then placed on a rotating mixer for 1 h at 4 °C. A cleared lysate was prepared by centrifugation at 7000 revolutions per min for 15 min. The cleared lysate was then purified using further using the MagneHis Protein Purification System (Promega V8500) according to the manufacturer protocols.

To quantify luminescence as a function of substrate concentration, purified Antares protein was diluted to 100 pM in DPBS with 0.01% FBS. Substrates were diluted to 25 μM and then serially diluted in two-fold steps into DPBS with 0.01% FBS in triplicate. 50 μL of diluted Antares protein was then combined with 50 μL of each substrate dilution. Luminescence was measured immediately using a GloMax-Multi+ luminometer (Promega). Kinetic parameters of KM and Vmax were calculated using the Michaelis-Menten non-linear regression function in the program Prism (GraphPad).

To monitor signal decay over time, purified Antares protein was diluted to 100 pM in DPBS with 0.01% FBS. Each substrate was diluted to 25 μM into DPBS with 0.01% FBS in triplicate. 50 μL of the Antares dilution was combined with 50 μL each substrate dilution. Luminescence was measured immediately using the GloMax-Multi+ luminometer, and then samples were measured every two minutes for 60 minutes to monitor signal decay over time.

Substrate stability.

Each substrate was diluted to 25 μM in either DPBS or DPBS with 10% FBS. Aliquots of the diluted substrates were made in wells of a thin walled 96-well PCR tray, which was then placed in a thermocycler set to incubate at 37 °C. At various times, 10 μL of each sample was added to 90 μL of a diluted NanoLuc solution in triplicate. When the luminescence measurements were complete, the half-life of each substrate was calculated by fitting to a one-phase decay function in the program Prism with asymptope set to zero.

Solubility testing.

To compare the solubility of Fz analogues in the injectable formulation of 10% ethanol (v/v), 10% glycerol(v/v), 10% 2-Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPBCD, w/v), 35% PEG-300 (v/v) in water, pre-weighed compound was dissolved or suspended in ethanol and then combined with a mixture of the other components, followed by 15 min of agitation on a vortex mixer, to create a 28 mM solution or suspension. Suspensions with undissolved solids were heated to 50 °C for 15 min to promote solubilization. More dilute solutions or suspensions were created by dilution into pre-mixed injectable formulation.

Solid formulation for use in whole-animal imaging.

Stock samples of solid formulated hydrofurimazine (HFz) and fluorofurimazine (FFz) were prepared as follows. 120 mg of poloxamer-407 (Pluronic F127) were placed into a glass, screw-cap vial. The polymer was then heated to 80 °C in a water bath until melted. HFz or FFz (18 mg) dissolved in 400 μL of ethanol was added to the hot polymer, mixing well with a thin spatula. Additional rinses of HFz or FFz in ethanol was added to the hot polymer for quantitative transfer. The solvent was then removed under vacuum. This concentrated sample was diluted with 4.5 mL of water to make a master stock of ~9 mM HFz or FFz in water. 480 μL of this aqueous stock was then aliquoted into glass vials, frozen, and lyophilized overnight to give a yellow cake. For an intraperitoneal injection into mice, 480 μL water was added to the vial and vortexed to create a clear solution, giving a single dose of 12 mg poloxamer-407 and 4.3 μmole HFz, or 3 doses of 4 mg poloxamer-407 and 1.3 μmole FFz.

Generation of luciferase-expressing stable tumor cell lines

HeLa cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamate, 100U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. EW8 or MG63.3 cell lines were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 (RPMI) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamate and 25 mM HEPES (Gibco), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 5 μg/mL plasmocin. HeLa cells and EW8 cells were lentiviral transfected with pLL3.7m-CMV-Antares-P2A-AkaLuc-WPRE, pLL3.7m-CMV-Antares-P2A-Blasticidin or pLL3.7m-CMV-AkaLuc-P2A-Blasticidin, MG63.3 cells were retroviral transfected with pMSCV-AkaLuc-mNeonGreen or pMSCV-Antares-mNeonGreen. 72 h after transfection, cells were dissociated with trypsin and re-suspended in DMEM, and then changed to PBS. Suspended cells were sorted for the top 5% brightest population on a FACSJazz cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Stable polyclonal cell lines were generated after ~ 1–2 weeks with 1–3 times of cell sorting. Flow cytometry data were analyzed on FlowJo software.

Retroviral vector production and T cell transduction.