Significance

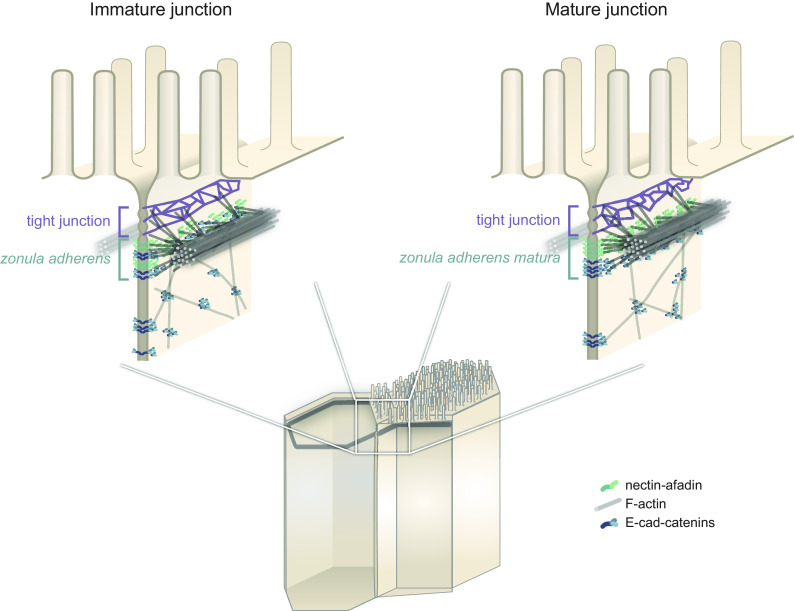

The zonula adherens (ZA), a fundamental module of epithelial cell–cell adhesion initially observed in intestinal cells, is believed to comprise a single contractile actin belt linked via E-cadherin (E-cad)-catenin to the ones of neighboring cells. Reevaluating this structure using super-resolution microscopy on intestinal samples, we show that the ZA consists of two distinct belts of adhesive complexes, a basal one with E-cad-catenin and an apical one with nectin–afadin. Contrary to the prevailing view, the major actin belt aligns with nectin and afadin, not E-cad-catenin. Genetic and physical perturbations show that afadin is essential for force transmission across cell junctions. Our work redefines the intestinal ZA architecture and prompts a reevaluation of how forces propagate within an epithelial sheet.

Keywords: epithelial cells, small intestine, zonula adherens, adhesive complexes, actin cytoskeleton

Abstract

Cell–cell apical junctions of epithelia consist of multiprotein complexes that organize as belts regulating cell–cell adhesion, permeability, and mechanical tension: the tight junction (zonula occludens), the zonula adherens (ZA), and the macula adherens. The prevailing dogma is that at the ZA, E-cadherin and catenins are lined with F-actin bundles that support and transmit mechanical tension between cells. Using super-resolution microscopy on human intestinal biopsies and Caco-2 cells, we show that two distinct multiprotein belts are basal of the tight junctions as the intestinal epithelia mature. The most apical is populated with nectins/afadin and lined with F-actin; the second is populated with E-cad/catenins. We name this dual-belt architecture the zonula adherens matura. We find that the apical contraction apparatus and the dual-belt organization rely on afadin expression. Our study provides a revised description of epithelial cell–cell junctions and identifies a module regulating the mechanics of epithelia.

The current description of epithelial apical junctions is based on the seminal work of Farquhar and Palade using electron microscopy (1), which defined three different areas in apical junctions of enterocytes: the most apical zonula occludens, also known as tight junctions, followed basally by the zonula adherens (ZA), with a wider intercellular space and the accumulation of cytoskeletal fibers, and the most basal macula adherens, consisting of desmosomes (2).

Molecular constituents were identified later, such as E-cadherin (E-cad) (3, 4), that was found on the lateral membrane, with an accumulation at the ZA (5). Identification of the E-cad/β-catenin/α-catenin complex followed shortly after (6), and because of α-catenin interaction with F-actin (6, 7), the E-cad–catenin complex anchoring the F-actin belt of apical epithelial cells is found in classical textbooks since the early 90s as the ZA and served as basic knowledge for several generations of biologists.

However, another major protein complex including a transmembrane protein and an actin-binding protein was discovered a decade later, the nectin–afadin complex (8, 9). This complex appears more specific to the ZA than the E-cad–catenin complex (9). Afadin is essential during development, including during the mechanically demanding phase of gastrulation, both in mice (10, 11) and Drosophila (12), and during ventral closure in Caenorhabditis elegans (13); afadin is also critical for epithelial apical constriction (11, 12). Similarly, nectin-2 was found to be crucial during epithelial apical constriction of the neural tube in Xenopus: nectin-2 depletion inhibits the epithelial apical constriction, whereas its overexpression enhances it (14). Together, this shows the functional importance of nectins and afadin for epithelia during organ development.

Interestingly, the E-cad–catenin complex and nectin–afadin complex interact through the binding of afadin to α-catenin (15–17). The interaction enhances the localization of the E-cad–catenin complex at nascent cell–cell adhesion sites (18), and it is necessary for the proper formation of the actomyosin apical belt, with only the afadin part binding to α-catenin being necessary (16).

In the last few years, the classical view of E-cad–catenin complex interaction with F-actin has been challenged. In mammary cells, F-actin organizes around E-cad clusters rather than connecting to them (19), and in vitro experiments showed that E-cad–catenin binds F-actin efficiently only under tension (20). To date, both E-cad and nectin-based protein complexes are described to be located at the ZA, and both have the potential to physically connect the actin meshwork from one cell to its neighbors at the apical junction.

To obtain a detailed view of this essential structure, we decided to use super-resolution microscopy and chose to investigate the supramolecular organization of the E-cad–catenin complex and nectin–afadin complex together with F-actin in human intestinal biopsies and human enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells (21). We imaged these samples with Stimulated Emission Depletion (STED) microscopy (22) and immunolabeling. STED improved the spatial resolution by threefold in the junctional plane, and, using cryosections, we could directly image junctions in the apico-basal axis to reach a sevenfold improvement in the spatial resolution along the apico-basal axis compared to approaches that would use confocal microscopy without physical sectioning. Although STED resolution is at least an order of magnitude lower than the electron microscopy resolution, which was used to define the morphology of epithelial apical junctions, the combination of STED with immunolabeling offers a venue for discovery, as multiple proteins can be efficiently labeled at the same time, a task that is much more difficult to achieve with electron microscopy.

Our approach allowed us to describe an unanticipated organization of apical junctions in intestinal cells compared to what is currently accepted. In intestinal cells lining villi and in Caco-2 cells grown on filter for 14 d, which can be seen in both cases as mature epithelial cells, we found that directly basal of the tight junction lies a belt where only nectins and afadin are found, lined with the F-actin belt; E-cad and catenins also form a belt, but they are found basal to the nectin–afadin–F-actin belt, with a much lower amount of F-actin. We also found that this organization is dependent on the maturation state of the cell, as the segregation between E-cad-rich and nectin-rich belts increases with maturation in vitro, which could partly explain why it was not found previously. To avoid confusion with other organizations of apical junctions found in the past, we name this dual belt of nectin–afadin–F-actin and E-cad–catenins the zonula adherens matura.

Results

Nectins–Afadin–F-Actin and E-cad–Catenins Form Separate Belts in Mature Intestinal Epithelia Both In Vivo and In Vitro.

To determine the organization of the apical junctions in intestinal cells, we started by observing the overall localization of the adhesion complexes and F-actin in human small intestine (ileum) biopsies. We found E-cad and catenins at the junctions of all epithelial cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and D), whereas nectins and afadin showed a different localization pattern. While we observed nectin-2 and afadin in all epithelial apical junctions, we found nectin-1 and nectin-3 only in the apical junctions of cells in crypts (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and D), similar to what has been reported in the Human Protein Atlas (23). The organization of F-actin was also drastically different between villi cells, where F-actin accumulates at the apical junction, and crypt cells, where such a junctional accumulation is not apparent (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). We focused our study on enterocytes in villi as they display more mature junctions than crypt enterocytes. Similarly to what has been observed several decades ago in intestinal cells (5, 24, 25), we found F-actin and E-cad on the lateral side of cells, and both accumulated at the most apical part, with F-actin often organized as a thick belt, of about 300 nm in width in the apico-basal direction (Fig. 1 A and B).

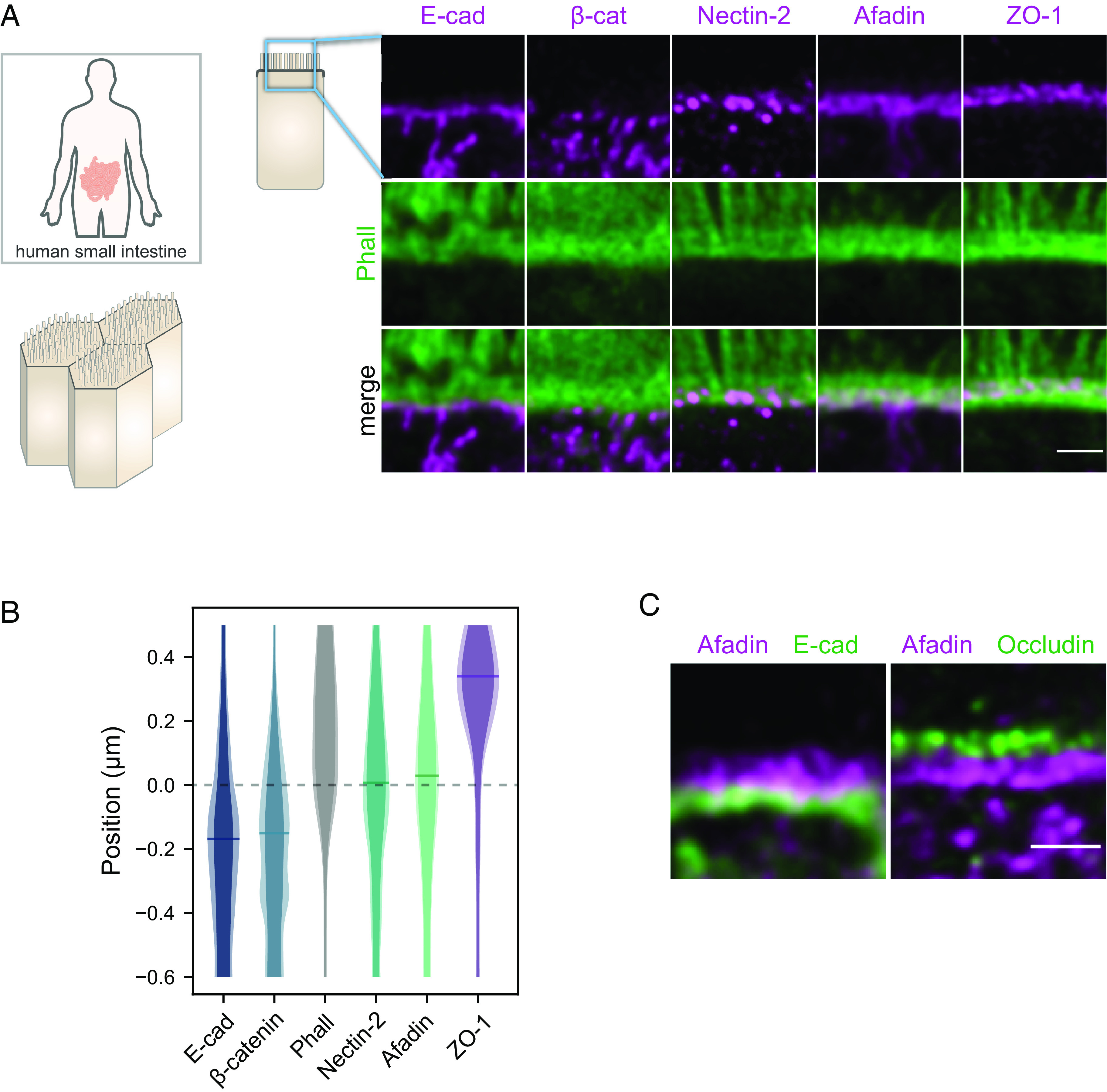

Fig. 1.

Segregation of adhesive complexes and their relative position compared to the F-actin belt in human ileum biopsies. (A) Side-view images of junctional complexes proteins (magenta) and F-actin (green). (B) Quantification of the position of adhesive complexes with respect to the F-actin belt on the apico-basal axis. The distributions represent the average intensity of a given protein labeling (plain color) and the average added with their SD (lighter color). Bars on distribution indicate the maxima of the distributions. Methodological details are given in the Materials and Methods. (C) Segregation of occludin (tight junction), afadin, and E-cad. (Scale bars 1 µm.) Details of replicates are given in SI Appendix, Table S1.

When focusing on the apical region of intestinal cells with STED, we found that E-cad accumulated basally from the F-actin belt, with the peak-to-peak distance between E-cad and F-actin distributions of about 180 nm (Fig. 1 A and B). These results are surprising because according to the classical model of the ZA, E-cad and catenins tie together the F-actin belts of neighboring cells and driven by mechanical balance should therefore localize at the same level. To confirm this result, we imaged β-catenin and made the same observation as for E-cad: The distribution of the E-cad–catenin complex was shifted about 180 nm basally from the distribution of the F-actin belt, with limited overlap between the distributions (Fig. 1 A and B). These unanticipated results made us wonder whether nectins rather than E-cad could line F-actin belts. When observing nectin-2 and afadin in intestinal cells, we found that both proteins were located at the position of the F-actin belt on the apico-basal axis (Fig. 1 A and B). Consistent with these results, we found that afadin and E-cad were present in distinct regions when imaged together, seemingly organized as belts, where afadin is apical of E-cad (Fig. 1C). The tight junction was present further apically, as occludin formed a distinct belt located apically of afadin (Fig. 1 A–C).

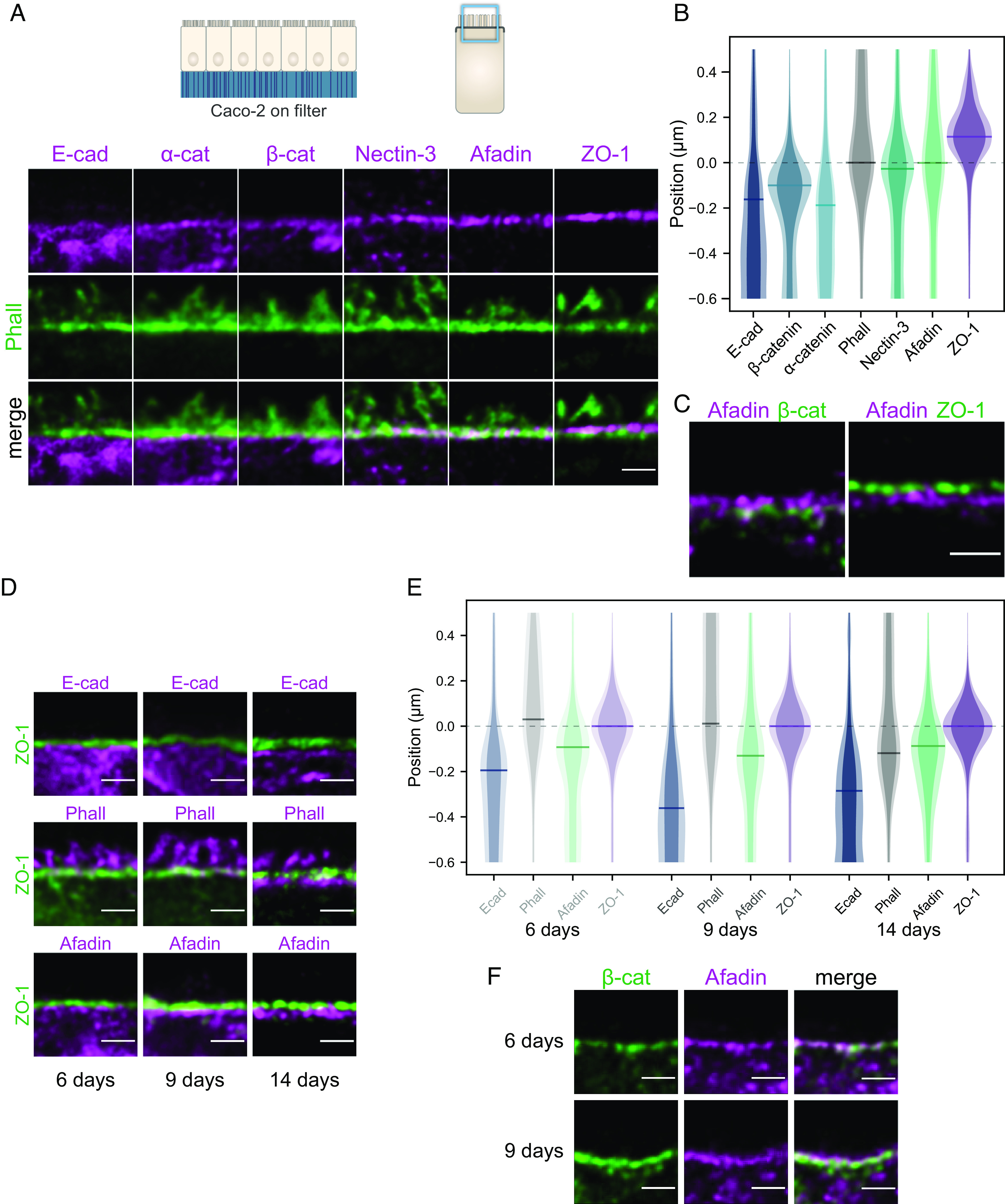

This unexpected segregation of E-cad and nectin complexes in human intestinal cells in vivo prompted us to investigate how E-cad and nectins are organized in vitro, where most of the research was achieved in the last decades. We used Caco-2 cells that we seeded on filters and grew over 14 d to allow differentiation (26). Similarly to what we observed in intestinal cells, we found F-actin and E-cad on the lateral side of cells, both accumulated at the most apical part, and the distribution of E-cad was shifted about 150 nm basally from the distribution of the F-actin belt, with limited overlap between the distribution (Fig. 2 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). E-cad overlapped with F-actin structures, but these structures had a staining intensity about 6 times weaker than the intensity of the F-actin belts when measuring along the apico-basal axis (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). To confirm this result, we imaged both α-catenin and β-catenin in Caco-2 cells and made the same observation as for E-cad: The distribution of the E-cad–catenin complex was shifted about 150 nm basally from the distribution of the F-actin belt (Fig. 2 A and B). Caco-2 cells express nectin-1, -2, and -3 (see below), and the best signal was obtained with antibodies against nectin-3; thus, we used nectin-3 for the super-resolution experiments. When observing nectin-3 and afadin in Caco-2 cells, we found that both proteins were precisely located at the position of the F-actin belt on the apico-basal axis (Fig. 2 A and B) and they colocalized (SI Appendix, Fig. S2E). As a confirmation, we found that afadin and β-catenin were present in distinct regions, where afadin was apical of β-catenin (Fig. 2C). The tight junction was present further apically, as ZO-1 formed a distinct belt located apically of afadin (Fig. 2 A–C). Vinculin and α-actinin are well-known interactors of the E-cad–catenin complex and F-actin (27, 28). We found both proteins are found in the region, but they did not localize preferentially with the E-cad–catenin complex, they were rather found where F-actin is located (in microvilli, F-actin belt, and cortical actin), with a preference for α-actinin for the basolateral membrane (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). The localization of vinculin at the level of afadin might be due to their common binding partner ponsin, which is also known to be located in the apical junction region in rat small intestine epithelia (29). We also detected nectin-1 and nectin-2 in the same region (SI Appendix, Fig. S2D).

Fig. 2.

Segregation of adhesive complexes and their relative position compared to the F-actin belt in Caco-2 cells. (A) Side-view images of junctional proteins (magenta) and F-actin (green). (B) Quantification of the position of adhesive complexes with respect to the F-actin belt on the apico-basal axis. The distributions represent the average intensity of a given protein labeling (plain color) and the average added with their SD (lighter color). Bars on distribution indicate the maxima of the distributions. Methodological details are given in the Materials and Methods. (C) Segregation of the tight junction (ZO-1), afadin, and β-catenin. (D) Side-view images of apical junctions comparing the tight junction (ZO-1) position to the position of E-cad, F-actin, and afadin at 6, 9, and 14 d. At 6 and 9 d, most of the F-actin signal is concentrated in microvilli. (E) Quantification of the position of the previous proteins with respect to ZO-1 on the apico-basal axis at 6, 9, and 14 d. (F) Afadin (magenta) and β-catenin (green) segregate as cells mature. (Scale bars 1 µm.) Details of replicates are given in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Altogether, these results show that two distinct belts of proteins are localized basally of the tight junction: the afadin and nectin belt that aligns with the F-actin belt along the apico-basal axis and the more basal E-cad and catenin belt. Each belt has a similar width of about 100 nm on average along the apico-basal axis. The tight junction and the E-cad–catenin belts are not devoid of filamentous actin but the signal is significantly weaker than at the nectin–afadin belt.

Nectin-3–Afadin–F-Actin and E-cad–Catenins Segregation Increases with Maturation.

Earlier studies have reported in intestinal samples and in cell culture that nectins and afadin localize in the same region as E-cad (8, 9) or that afadin is localized at the tight junction (30). The discrepancy between our findings and earlier studies may stem from two nonexclusive possibilities: the lower spatial resolution of the previously used techniques or the differentiation stage of the cells. Previous studies often used cell cultures that had just reached full confluence, a state obtained a few days after seeding cells on a substrate. At this differentiation stage cells have junctions, but these often do not recapitulate the functional characteristics found in vivo, which usually requires more time (26). To test whether this colocalization is due to a lack of resolution or to a potential maturation of the junctions during the epithelial layer differentiation, we seeded Caco-2 cells on filters and fixed them at intermediate stages of differentiation: just after they reached full confluence at 6 d and later at 9 d. In comparison, the results shown in Fig. 2 A–C were obtained from cells at 14 d (i.e., being fully confluent for 8 d). In cells that had just reached full confluence (6 d), E-cad and afadin were both located basally of the tight junction and their distribution along the apico-basal axis overlapped (Fig. 2 D and E). At 9 d, a clear gap between E-cad and the tight junction could be observed (Fig. 2D) and the distributions of E-cad and afadin were well separated. When imaged together, afadin and β-catenin were often difficult to separate at 6 d, whereas at 9 d they appeared partly segregated (Fig. 2F). F-actin was located at the level of the tight junction at 6 and 9 d, but it relocated to the level of the afadin-nectin complex at 14 d. Taking these results together, we found that as cells differentiate, the tight junction, the nectin-based and the E-cad-based junctions segregated while F-actin accumulated at the level of the nectin-based junction.

Afadin Is Necessary to Segregate Tight Junction, E-cad, and Nectin-3–F-Actin Belts.

Next, we wondered what is causing the belts of nectin–afadin–F-actin and E-cad–catenins to segregate. Both the E-cad–catenin complex and the nectin–afadin complex can interact with F-actin through α-catenin (6, 7) and afadin (8) respectively. As a result, the two complexes may compete to bind F-actin. Because F-actin lines the nectin–afadin belt, we hypothesized that the afadin link to F-actin was favored here, rather than the link between α-catenin and F-actin, resulting in the segregation of the nectin–afadin–F-actin and E-cad–catenins belts.

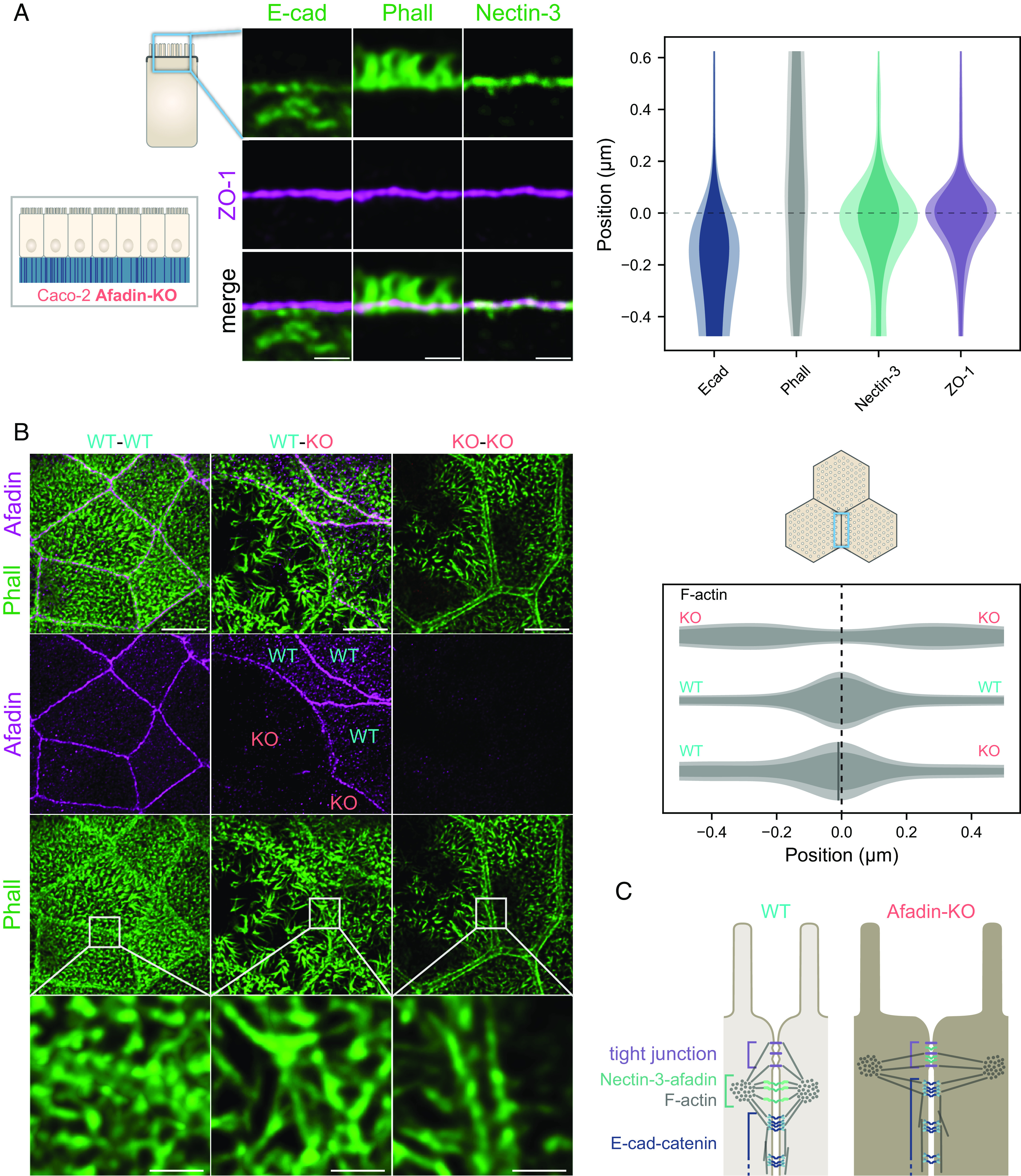

To test this hypothesis, we generated a CRISPR knockout (KO) of afadin in Caco-2 cells (Materials and Methods and SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6) and observed how the components of the belts, E-cad, nectin-3, F-actin, and ZO-1 would behave in mature cells, at 14 d. The zonula adherens matura was lost: We found nectin-3 at the level of ZO-1, which formed a first belt, E-cad organized in a separate belt basal of ZO-1 and nectin-3, and F-actin did not locate anymore at the level of nectins (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). In the absence of afadin, F-actin did not localize precisely at the tight junction or the E-cad belt, as the distribution of its localization on the apico-basal axis did not show any peak of concentration in the close vicinity of the tight junction (Fig. 3A). A simple explanation can be found by looking at individual junctions in afadin-KO cells: We observed a significant cell-to-cell variation in the apico-lateral localization of the F-actin belt, which could be identified at various positions around tight junctions (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), indicating again that its link to the junctional belts was hampered. In contrast, in WT (wild-type) cells, we found F-actin systematically at the nectin–afadin level (Fig. 2 A and B). The absence of afadin is likely to redefine the hierarchy of binding of adhesive complexes to the F-actin belt that then redistributes between the tight junction of the E-cad–catenin complex, this redistribution may be unbalanced and cell-to-cell dependent. The weaker apical tension as well as the larger distance to the apical junction may also relax the strict localization of the F-actin belt observed in WT cells. The absence of afadin did not affect the separation between E-cad and nectin-3. The localization of nectin-3 at the tight junction may be explained by the fact that nectins bind to PAR3 (31), which is found at the tight junction in cultured epithelial cells and in intestinal cells (32–34). PAR3 localization is not affected by the absence of afadin in MDCK cells (35).

Fig. 3.

Effect of the afadin KO on junctional proteins organization in Caco-2 cells. (A, Left) side-view images of E-cad, afadin, and F-actin (green) and the tight junction (ZO-1, magenta). (Scale bars 1 µm.) (Right) quantification of the position of the previous proteins with respect to ZO-1 on the apico-basal axis. The distributions represent the average intensity of a given protein labeling (plain color) and the average added with their SD (lighter color). (B, Left) top-view images of F-actin (green) and afadin (magenta) at the apical surface of wild-type and afadin-KO Caco-2 cell. (Bottom row) zooms of framed areas. (Scale bars, Top rows 5 µm, Bottom row 1 µm.) (Right) quantification of the position of F-actin perpendicular to the junction in the apical plane. Details of replicates are given in SI Appendix, Table S3. Cells were grown for 14 d. (C) Model of the enterocyte apical junction in afadin KO. Actin filaments in the terminal web and microvilli are not represented for clarity.

When we observed the organization of F-actin in the apical plane of afadin-KO cells, we found that indeed the link of the F-actin belt to the junction is affected (Fig. 3 B and C). The distance between F-actin belts of neighboring cells was much larger in afadin-KO cells when compared to WT cells. Moreover, F-actin belts of neighboring cells showed in most cases a large gap devoid of observable actin. Electron microscopy images of similar cases do not exhibit plasma membrane modification but a shift away from it of a dense structure reminiscent of actin (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This observation looks like what was already observed in an afadin KO in Eph4 mouse mammary gland epithelial cells, where the authors showed that F-actin belts enlarge significantly, although in this case separation from the plasma membrane is less obvious (16). Examples where the distance between the F-actin belt of neighboring cells was the largest made clear that the gap is devoid of microvilli, suggesting that the F-actin belt has moved from the vicinity of the lateral membrane to the edge of the terminal web, or that the terminal web was smaller than in WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). These results show that afadin is key to the segregation of tight junction, E-cad, and nectin-3–F-actin belts in the zonula adherens matura and for the localization of the F-actin belt close to the plasma membrane.

The Nectin–Afadin–Actin Belt Is a Key Component of the Apical Contraction Apparatus.

The alteration of the F-actin belt localization in the afadin KO led us to question the role of the nectin–afadin–F-actin belt in the zonula adherens matura. The F-actin belt is an important center of the epithelial apical mechanical tension in vertebrates and invertebrates (36, 37), most likely together with the terminal web in intestinal cells (24, 38). Because afadin links F-actin, we hypothesized that the alteration of the F-actin belt in afadin-KO cells could affect the apical tension, indicating that afadin could be a key component of the force transmission between mature intestinal cells.

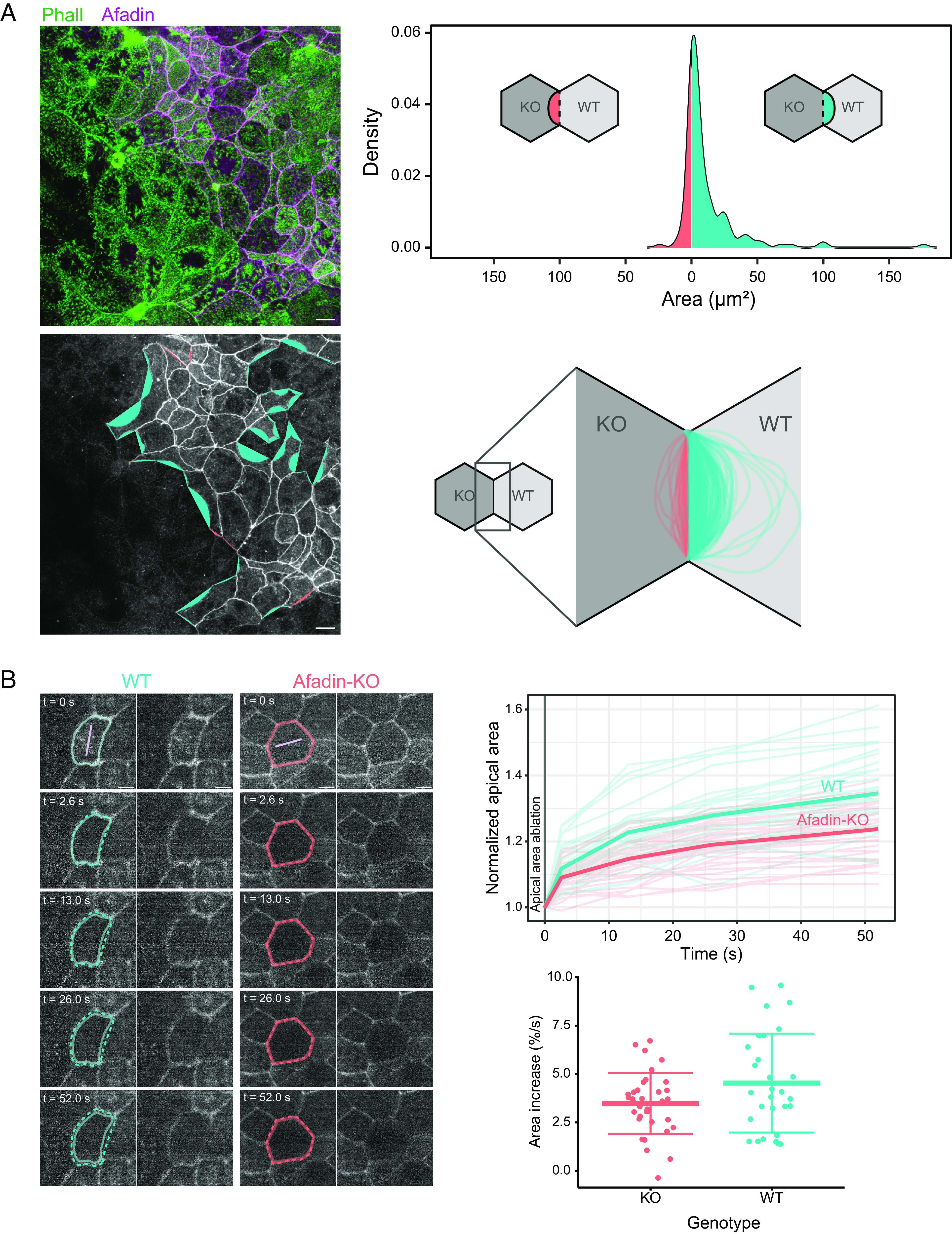

To test this hypothesis, we devised two experiments. In the first experiment, we cocultured WT and afadin-KO cells for 14 d and observed the shape of apical junctions at the interface between WT and afadin-KO cells. Out of 169 junctions observed, 128 (75.7%) were curved toward WT cells, 23 (13.6%) were curved toward afadin-KO cells, and 18 (10.7%) did not show a curvature toward a specific cell type (Fig. 4A). This result indicates that afadin-KO cells are more compliant than WT cells, but where does it stem from? Two non-mutually exclusive hypotheses can be suggested to explain our data: a lower apical surface tension in afadin-KO cells compared to WT cells or a higher interfacial tension between afadin-KO and WT cells compared to that between WT cells. To better understand the mechanics at play, we observed in a second set of experiments how cells respond to the laser ablation of their apical surface or their junctions. The apical domain consists mostly of the terminal web, the F-actin meshwork below the apical surface of intestinal cells. It is known to be part of the apical contraction apparatus of these cells together with the F-actin belt (24, 38). After laser ablation of the terminal web in WT and afadin-KO cells expressing GFP-occludin, we found that instantly after the ablation, the apical area of WT cells enlarged on average 30% faster than the one of afadin-KO cells, and we found that with the apical area enlargement after 50 s was about 50% larger in WT cells than in afadin-KO cells (Fig. 4B). When we used laser ablation on cell–cell junctions, we did not find a significant difference in the recoil velocity between cell–cell junctions of WT cells and afadin-KO cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C), indicating that these two types of junctions have a similar tension. Altogether these results indicate that afadin-KO cells have a lower apical tension than WT cells, but their junctional tension levels have no apparent differences. In afadin-KO cells, it is possible that the E-cad–catenin complex and the tight junction partly take over the role that the nectin–afadin complex has in WT cells. These results show that afadin is a key component of the apical contraction apparatus in epithelial cells, in which afadin seems to be implicated in the transmission of the apical tension of neighboring cells. While E-cad–catenin and the tight junction components such as ZO proteins also support force transmission between intestinal cells (39–41), our results suggest that in mature cells the nectin–afadin complex plays an important role in this process.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the afadin KO on the apical mechanics in Caco-2 cells. (A) Shapes of WT/afadin-KO cells junctions. Left, apical junctions of mixed WT and afadin-KO cells. (Top Left) F-actin (green), afadin (magenta), (Bottom Left) afadin (gray). (Bottom Left) areas are generated from the junction that would be hypothetically straight and the actual junction. When the area leans toward a WT cell, it is colored in cyan, whereas when it leans toward an afadin-KO cell, it is colored in red. (Top Right) distribution of the previously defined areas; positive areas are for areas toward WT cells and negative areas toward afadin-KO cells. (Scale bars 10 µm.) (Bottom Right) shapes of individual junctions; shapes toward WT cells in cyan, and afadin-KO cells in red. (B, Left) examples of terminal web laser ablation in WT and afadin-KO cells expressing GFP-occludin grown for 14 d. Location of ablation in light purple. The junction at t = 0 is represented by a full line (kept on all images), and the one at later time points is represented by a dashed line. (Scale bars 5 µm.) Movies of these examples are given in Movies S1 and S2. (Top Right) quantification of the evolution of the normalized apical surface area over time after ablation (t = 0) in WT (cyan) and afadin-KO (red) cells. Thin line, individual cell, thick line averaged over one cell type. For normalization, all cell areas are scaled to 1 at t = 0. (Bottom Right) relative value of initial area spreading measured as the relative area difference over time between t = 0 and t = 2.6 s. Details of replicates are given in SI Appendix, Table S4.

Discussion

Altogether, our results show that the apical junction of intestinal cells needs to be redefined. First, we found using STED microscopy both in vivo and in cell culture that the nectin–afadin complex is precisely located at the position of the F-actin belt on the apico-basal axis in intestinal epithelial cells (Figs. 1 and 2). In contrast, the E-cad–catenin complex is found more basally, segregated from nectins and afadin. Second, our cell culture time course demonstrated that the organization of the ZA depends on cell differentiation, as the segregation between nectin–afadin and E-cad–catenins intensifies over 14 d (Fig. 2). In immature junctions, it is likely that both E-cad and nectin adhesive complexes are mixed as one could conclude from previous reports (9). Third, our results showed that the nectin–afadin complex plays an important part in the apical contraction apparatus of mature cells (Figs. 3 and 4). Since the definition of the ZA by Farquhar and Palade (1), the region was redefined many times in different models by different authors. For this reason and because the organization we describe here in mature intestinal cells is drastically different from what was reported in the past, we name the dual-belt organization of nectins–afadin–F-actin and E-cad–catenins the zonula adherens matura (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Model of the immature and mature enterocyte apical junction. Actin filaments in the terminal web and microvilli are not represented for clarity.

Why is this organization present in differentiated epithelial cells? A possible explanation could lie in the way catenins and afadin interact with F-actin. When a junction is established, both nectin–afadin and E-cad–catenins are present and bind to F-actin (18). Because the E-cad–catenin complex binds F-actin efficiently only under tension (20), its association with the F-actin belt is likely dynamic. Interestingly, we find in zonula adherens matura that vinculin, which stabilizes the link between F-actin and the E-cad–catenin complex, is enriched at the level of the nectin–afadin-F-actin belt rather than the E-cad–catenin level (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), potentially because of ponsin, that binds both afadin and vinculin. Protein complexes other than E-cad–catenins with a more stable interaction with actin could take over as the junction matures. This more stable interaction could also provide enough stable anchor points necessary for the proper maturation of the actin network, as suggested by our results in the afadin-KO cells (Figs. 3 and 4). Interestingly, it was recently discovered in EpH4 mouse mammary gland epithelial cells that afadin binds to α-catenin and enhances its F-actin–binding activity when complexed with β-catenin (16). This phenomenon may also be at play in intestinal cells, but likely before the cell reaches a mature junction state, as we find afadin and catenins segregated in the zonula adherens matura. While the E-cad–catenin complex has been presented as the main adhesive complex at the ZA of epithelial cells, and in intestinal cells in particular, as presented in major textbooks (42), our work sheds light on this implication, and we show that the nectin–afadin complex should also be considered as a key adhesive complex transmitting tension at the ZA region in mature intestinal cells. The two adhesive complexes may both transmit tension, either through a direct link to the F-actin belt or through their potential interaction at the border between the two belts. However, that nectin–afadin is a key player of force transmission at the apical junction does not question the fact that most cell–cell adhesion takes place on the lateral side of intestinal cells where E-cad is present. The zonula occludens is also very likely to take part in the tension transmission between epithelial cells (41), which may depend on the maturation state of the junction.

Our functional results using the afadin KO in Caco-2 cells show that afadin is necessary for the establishment of the zonula adherens matura. We have shown that the apical contraction apparatus is perturbed, but what could be other consequences? The conditional knockout of afadin in mice small intestine showed that the loss of afadin increased the paracellular permeability of the epithelia (43). Even if the junctional architecture appeared to be preserved in this knockout, the proper organization of the junction likely impacts the tight junction organization or composition as nectins and afadin are necessary for the localization of claudins and JAM at the apical side of adherens junctions (44). Whether the maturation of the ZA is necessary for the proper organization of the tight junction will require further studies. A limit of our afadin KO cell line is that it tackles only a part of the nectin–afadin complex. While in epithelial cells nectins functions are usually in tight relation with afadin, the afadin coiled-coil domain alone, without binding capabilities to nectins, was shown recently to be crucial for the proper formation of the adherens junction (16). Because the coiled-coil domain of afadin interacts with α-catenin and cannot interact with other partners, such as ZO-1 for instance, it is unlikely that cells can form a proper ZA matura, nor that the tight junction is fully functional.

What is the nectin composition at the zonula adherens matura? We show that the nectin–afadin complex is a key player in force transmission at apical junctions, so the complex is very likely under force. Previous work has shown that nectins heterophilic trans-dimers form stronger cell–cell adhesion than homophilic trans-dimers (45, 46). The cell may take advantage of these properties at the zonula adherens matura to increase the mechanical stability of the junction. In Caco-2, we found nectin-1, nectin-2, and nectin-3 so such a mechanism may be at play. However, in the human intestine villi, we detected only nectin-3. Nectin-1 and nectin-2 are only present in crypts [SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and (23)] and nectin-4, the last member of the nectin family, is not expected to be located in the small intestine (23). Therefore, force transmission in the intestine villi likely occurs through nectin-3 homophilic trans-dimers.

Is there a link between F-actin and E-cad-catenin complex at the zonula adherens matura? This is an important question because the absence of a link of the complex to F-actin was shown in several contexts to disrupt the epithelial organization. Many cancers originating from epithelial tissues and resulting in the loss of epithelial organization correlate with the loss of α-catenin (47). In vitro, human colon cancer cell lines lacking α-catenin are invasive whereas those that do not lack it tend to have epithelial traits (48). The expression of α-catenin in human colon cancer cell line variant deficient for α-catenin rescue in great part the epithelial traits of the cells that are lost otherwise (49). The conditional deletion of α-catenin in developing surface and oral epithelia of mouse embryos leads to defects in adherens junction formation, intercellular adhesion, and epithelial polarity (50). These behaviors are likely to be linked to the fact that, at the molecular level, α-catenin competes with Arp2/3, the latter favoring cell invasion and proliferation (51). These results indicate that afadin and nectins alone are not sufficient to support epithelial adhesion, the E-cad-catenin complex is necessary. We observed that the E-cad-catenin complex is concentrated in a belt at the zonula adherens matura, but a significant part of the complex is also found basal of the apical region both in intestinal biopsies and in cell culture (Figs. 1 and 2). F-actin is strongly concentrated in the apical region, but more basal regions, including where the E-cad-catenin complex is concentrated, are not devoid of F-actin (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2). Therefore, it is possible that the E-cad-catenin complex does not bind directly to the zonula adherens matura F-actin belt, but it is very likely connected to the cortical actin meshwork to support the overall cell–cell adhesion all over the lateral membrane. The process of maturation may stabilize the connection of afadin to the F-actin belt which could then prevent the modification of the actin network by Arp2/3.

Could the zonula adherens matura be more complex than what we present here? We found that the zonula adherens matura is made of two belts, the E-cad–catenin one and the nectins–afadin–F-actin one. Many other proteins are potentially present in the region, including cingulin (52), MUPP1 (53, 54), ponsin (29), CASK (55–59), ADIP (60), which is thought to link afadin and α-catenin, and the transmembrane protein JAM-A (61), which binds to PAR-3, ZO-1, and afadin. Such proteins could also be organized as additional belts at the zonula adherens matura.

Why was the zonula adherens matura not observed before? As stated earlier, the first reason is likely technical. Super-resolution microscopy offers the advantage of using efficient multiprotein immunolabeling together with improved resolution compared to confocal microscopy. The sample preparation used here, and in particular cryosectioning of cultured cells, allows observations in the apico-basal direction that are more difficult to achieve when using a confocal stack. Therefore, cryosectioning together with STED allowed us to reach a resolution of about 80 nm in the apico-basal axis, where the reconstruction of a confocal stack along the apico-basal axis would be limited to a resolution of about 600 nm. The second reason is linked to the maturation state of the cells. Most research with cell culture is done at confluence, a state reached after a few hours to a few days after seeding cells, which in our case was not sufficient to recapitulate fully what we observed in human biopsies. Interestingly, Boller et al. observed with immunolabeling and electron microscopy in rat and mouse small intestines that E-cad is concentrated basally of the tight junction (5). Photo composition displays in this pioneering work show several examples of junctions where the E-cad label exhibits what seems to be a separation with the tight junction of 100 to 250 nm. Thus, a reread of these experiments highlights an undefined space coherent with the results we gathered and suggests that rat and mouse intestines display likely the zonula adherens matura organization. The last reason is more fundamental. Cellular junctions of epithelia share many similarities, but also many differences, from the tissue level to species. At the tissue level, apical junctions can vary strongly, such as in the inner ear where apical junctions vary in composition and height from a few hundred nanometers to a few microns (62–64), or in the vertebrate intestine, junctions between enterocytes and enterocyte-goblet cells are different (65). Apical junctions are not perfectly conserved throughout metazoans (66). Invertebrates usually lack tight junctions that are replaced by the septate junction (67, 68), just like in the widely studied Drosophila melanogaster (69). Therefore, apical junctions come in various forms and compositions, depending on species, localization, and function. Junctional architectures similar to the zonula adherens matura may be found in other tissues sharing similar functions and mechanical environments, such as simple cuboidal and columnar epithelia along the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, kidney, mammary glands, or salivary glands to name a few.

This study opens venues to understand how apical junctions function, how they sustain mechanical stresses, and how they mature. Our findings stress that the role of E-cad at apical junctions may need to be revisited and that its role as a mechanical link may not be as general as it is often thought. We hope these findings will benefit the mechanistic understanding of nectins implication in multiple human pathologies (70).

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

A clone of Caco-2 cells, TC7, was used in this study because differentiated TC7 cells form a regular monolayer (21). Cells were seeded at a low concentration of 105 cells on a 24-mm polyester filter with 0.4-µm pores (3450, Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% nonessential amino acids (Gibco, Waltham, MA), and cultured in 10% CO2/90% air. The medium was changed every 48 h.

TC7 cells knocked out for Afadin were obtained by CRISPR/Cas9 strategy according to Zhang and colleagues (71). Briefly, annealed primers coding for guide RNAs (gRNA) targeting AFDN either at Exon2 (5′-CTCTAGTTGTACAACTGAAT-3′) or Exon3 (5′-CTCTAGTTGTACAACTGAAT-3′) were inserted at the Bbs1 site of PX458 vector (Addgene #48138). Cells were transfected by Nucleofection (Amaxa, Lonza, Switzerland) according to the supplier recommendation (Kit L, prog B024). After 24 h later, green fluorescent protein-(GFP) positive cells were sorted out and cloned using an ARIA III (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, USA). Candidate clones obtained were screened by western blotting for Afadin expression. Clones of interest were further characterized by DNA genomic sequencing of AFDN exon targeted by gRNA and were considered only when two frameshift mutations leading to a premature stop codon were defined. In this study, we used an afadin-KO Caco-2 clone named 35A10 whose sequence reveals a deletion of 23 bases in exon 3 leading to a premature stop codon. Afadin expression in WT and afadin-KO Caco-2 cell extracts (5 µg) was monitored by western blot analysis as described in ref. 72. The description of the clones prepared for this study as well as their main F-actin organizational features are given in SI Appendix, Fig. S6. The clones whose names start with 33 were obtained by targeting AFDN exon 2 and those with 35 by targeting AFDN exon 3.

Stable WT and afadin-KO Caco-2 cells expressing GFP-occludin were obtained after transfection with LZRS-GFP-occludin-IRES-zeocin plasmid (73) by nucleofection (Amaxa, Lonza, Switzerland) according to the supplier recommendation (Kit T, prog T20), and zeocin selection (300 µg/mL). Cells were grown for 14 d before being used for laser ablation experiments.

Sample Preparation for Immunostaining.

Human sample preparation.

Human intestine biopsies were obtained under the agreement IPC-CNRS-AMU 154736/MB from the Paoli-Calmettes Institute Ethics Committee, Marseille France. Samples were deidentified before we used them in our study, and participants provided informed consent. Intestinal samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (from 32% PFA, Fischer Scientific) in phosphate buffer saline (PBS, Gibco) for 4 h at 4 °C. Biopsies were then cryoprotected with sucrose (10% sucrose in PBS for 45 min, 20% sucrose for 45 min followed by 30% sucrose overnight at 4 °C). Biopsies were finally embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT compound, VWR) and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Cell culture preparation for optical microscopy.

Cells were washed in PBS and then fixed in PFA 4% in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. When apico-basal orientation observations were needed, cells were sectioned along the apico-basal axis. Before sectioning, cells were embedded in OCT compound and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Samples sectioning.

All samples were sectioned with a cryostat (Leica CM 3050 S, Leica Biosystems). Before labeling, ten-micrometer thick sections were transferred to Superfrost Plus adhesive slides (Thermo Scientific).

Immunostaining.

Intestinal sections and cultured cells were prepared similarly. Samples were permeabilized in 1% Triton X100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 10 min. After washing with PBS, samples were saturated with 10% fetal bovine sera (Gibco) in PBS (“saturation buffer”) over an hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies were diluted in the saturation buffer and incubated overnight at 4 °C. We used the following antibodies: rabbit anti-ZO-1 (1/500, 61-7300, Invitrogen), mouse anti-occludin (1/500, 331500, Invitrogen), mouse anti-E-cad (1/500, 610181, BD Biosciences, used on Caco-2 cells), rat anti-E-cad (1/400, M108, Takara, used on human biopsies), rabbit anti-β-catenin (1/200, ab32572, Abcam), rabbit anti-alpha-catenin (1/200, 711200, Invitrogen), mouse anti-afadin (1/100, 610732, BD Biosciences, used on Caco-2 cells), rabbit anti-afadin (1/200, HPA030213, Sigma-Aldrich, used on human biopsies), mouse anti-nectin-1 and anti-nectin-3 (1/200, kind gifts of Marc Lopez), rabbit anti-nectin-2 (1/200, HPA012759, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-α-actinin (A5044, Merck), mouse anti-vinculin (MAB3574, Merck). Secondary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated antibodies raised against the mouse, rabbit, and rat and Alexa Fluor 532–conjugated antibodies raised against the mouse and rabbit (Invitrogen) were used at 1/200 dilution in the saturation media. Phalloidin Alexa Fluor A532 (Invitrogen) was mixed with secondary antibodies and used at 1/100 dilution. After each incubation, samples were rinsed 4 times with PBS. Samples were finally mounted in Prolong Gold antifade mounting media (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 45 min.

STED Microscopy.

Images of samples were acquired with a STED microscope (Leica TCS SP8 STED, Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), using a 100× oil immersion objective (STED WHITE, HC PL APO 100×/1.40, same supplier). Two-color STED was performed with Alexa Fluor 532 excited at 522 nm (fluorescence detection in the 532- to 555-nm window) and Alexa Fluor 568 excited at 585 nm (fluorescence detection in the 595- to 646-nm window). To minimize the effect of drifts on imaging, both dyes were imaged sequentially on each line of an image and depleted using the same 660-nm laser. Detection was gated to improve STED signal specificity.

Electron Microscopy.

Cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 2% PFA, and 0.1% tannic acid in sodium cacodylate 0.1 M solution for 30 min at room temperature. After washing steps, cells were postfixed in 1% osmium in sodium cacodylate 0.1 M solution for 30 min at room temperature and contrasted in 2% uranyl acetate in water solution for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then dehydrated in ethanol and embedded in EPON epoxy resin. Cells were observed with a transmission electron microscope, FEI Tecnai G2 200 kV (FEI, The Netherlands).

Laser Ablation on Caco-2 Cells.

Ablations were performed with a scanner-based module and a 355-nm laser (Rapp OptoElectronic, Germany), imaged with a confocal spinning disk microscope using a 60X oil immersion objective (UPLXAPO60XO 60×/1.42, Evident, Japan) with an exposure time of 200 ms.

Data Analysis.

Analysis of protein density.

To quantify the density of proteins along the apico-basal axis and their positions with respect to each other, we used custom-made ImageJ macros and Python programs. In brief, in each case, a reference protein was localized precisely, defining a reference position along the junction from which intensity measurement was done. The intensity of protein labeling was measured along the apico-basal axis for each position of the junction. In practice, every 10 nm along the junction, an algorithm drew a segment along the apico-basal axis to extract the intensity profile of both proteins studied. In the process, we used bilinear interpolation to obtain subpixel quantification. The results of analyses were then normalized for each junction to avoid junction-to-junction intensity variation. Because we used a reference protein for each junction, we could then align all results based on the reference position of the reference protein and pool all results into a single protein density plot.

In Fig. 1 (human ileum sections), the reference used was 100 nm above the most basal edge of the F-actin belt, determined by eye. Only enterocyte-to-enterocyte junctions were used in this study. In Figs. 2 and 3 (Caco-2 cells), the reference was the F-actin belt (Fig. 2 A and B) and ZO-1 (Figs. 2 D and E and 3). The position of the reference was found automatically with an ImageJ macro, determining the maximum intensity of the reference protein staining intensity along the apico-basal direction for each position along the junction.

Analysis of Junction Shape at WT versus Afadin-KO Caco-2 Cells.

To determine quantitatively how junctions were shaped at the interface between WT and afadin-KO cells, we traced manually junctions in ImageJ and retrieved their position with a custom macro. The area imbalance at these junctions was defined as depicted in Fig. 4, with the circumference defined by the junction looped with a segment between the nodes of the junction. To compare junction shapes in the Bottom Right of Fig. 4A, the length of the segment between the node of the junction was set to 1.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Example of the laser ablation of the apical area of WT Caco-2 cell. Image size: 30.44 μm, time difference between frames: 0.26 s.

Example of the laser ablation of the apical area of afadin-KO Caco-2 cell. Image size: 30.44 μm, time difference between frames: 0.26 s.

Example of the laser ablation of a junction of a WT Caco-2 cell. Image size: 20 × 20 μm, time difference between frames: 0.26 s.

Example of the laser ablation of a junction of an afadin-KO Caco-2 cell. Image size: 20 × 20 μm, time difference between frames: 0.26 s.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Marc Lopez for the gift of several antibodies and Flora Poizat for human biopsies. We are grateful to Raphaël Clément, Virgile Viasnoff, Stefan Harmansa, Emily Gehrels, Anaïs Bailles, Frank Schnorrer and his group, Le Bivic and Lenne groups for discussions. Biopsies were obtained with the agreement IPC-CNRS-AMU 154736/MB. We also thank Feng Zhang for sharing the pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) vector and the flow cytometry and cell sorting facility of the Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie de Marseille. We acknowledge the Institut de Biologie du Développement de Marseille (IBDM) imaging facility, member of the national infrastructure France-BioImaging supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR-10-INBS-04). P.M. was supported by Instituts thématiques multi-organismes (ITMO) Cancer (Plan Cancer), Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, and the French National Research Agency (ANR-T-JUST, ANR-17-CE14-0032, ANR-EvolAj, and ANR-21-CE13-0013-01). The project developed in institutes supported by the LabEx INFORM (ANR-11-LABX-0054) and of the A*MIDEX project (ANR-11-IDEX-0001-02), funded by the “Investissements d’Avenir” French Government program. P.M. is supported by Aix-Marseille Université, D.M.-H. and M.S. are supported by INSERM, and A.L.B. and P.-F.L. are supported by CNRS.

Author contributions

P.M., D.M.-H., M.S., A.L.B., and P.-F.L. designed research; P.M., D.M.-H., M.S., and F.R. performed research; P.M., D.M.-H., and M.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; P.M. analyzed data; and P.M., D.M.-H., M.S., A.L.B., and P.-F.L. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Pierre Mangeol, Email: pierre.mangeol@univ-amu.fr.

André Le Bivic, Email: andre.le-bivic@univ-amu.fr.

Pierre-François Lenne, Email: pierre-francois.lenne@univ-amu.fr.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Data and codes used to extract information from images and generate graphs are available on GitHub, at https://github.com/PierreMangeol/zonula_adherens_matura (74).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Farquhar M. G., Palade G. E., Junctional complexes in various epithelia. J. Cell Biol. 17, 375–412 (1963). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obland G. F., The fine structure of the interrelationship of cells in the human epidermis. J. Cell Biol. 4, 529–538 (1958). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyafil F., Morello D., Babinet C., Jacob F., A cell surface glycoprotein involved in the compaction of embryonal carcinoma cells and cleavage stage embryos. Cell 21, 927–934 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida C., Takeichi M., Teratocarcinoma cell adhesion: Identification of a cell-surface protein involved in calcium-dependent cell aggregation. Cell 28, 217–224 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boller K., Vestweber D., Kemler R., Cell-adhesion molecule uvomorulin is localized in the intermediate junctions of adult intestinal epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 100, 327–332 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozawa M., Baribault H., Kemler R., The cytoplasmic domain of the cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin associates with three independent proteins structurally related in different species. EMBO J. 8, 1711–1717 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rimm D. L., Koslov E. R., Kebriaei P., Cianci C. D., Morrow J. S., al(E)-Catenin is an actin-binding and -bundling protein mediating the attachment of F-actin to the membrane adhesion complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 5 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandai K., et al. , Afadin: A novel actin filament–binding protein with one PDZ domain localized at cadherin-based cell-to-cell adherens junction. J. Cell Biol. 139, 517–528 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi K., et al. , Nectin/PRR: An immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecule recruited to cadherin-based adherens junctions through interaction with afadin, a PDZ domain–containing protein. J. Cell Biol. 145, 539–549 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda W., et al. , Afadin: A key molecule essential for structural organization of cell-cell junctions of polarized epithelia during embryogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 146, 1117–1132 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhadanov A. B., et al. , Absence of the tight junctional protein AF-6 disrupts epithelial cell–cell junctions and cell polarity during mouse development. Curr. Biol. 9, 880–888 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawyer J. K., Harris N. J., Slep K. C., Gaul U., Peifer M., The Drosophila afadin homologue Canoe regulates linkage of the actin cytoskeleton to adherens junctions during apical constriction. J. Cell Biol. 186, 57–73 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall A. E., Klompstra D., Nance J., C. elegans Afadin is required for epidermal morphogenesis and functionally interfaces with the cadherin-catenin complex and RhoGAP PAC-1/ARHGAP21. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2023). 10.1101/2023.07.28.551013 (Accessed 30 July 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Morita H., et al. , Nectin-2 and N-cadherin interact through extracellular domains and induce apical accumulation of F-actin in apical constriction of Xenopus neural tube morphogenesis. Development 137, 1315–1325 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pokutta S., Drees F., Takai Y., Nelson W. J., Weis W. I., Biochemical and structural definition of the l-afadin- and actin-binding sites of α-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18868–18874 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakakibara S., et al. , Afadin regulates actomyosin organization through αE-catenin at adherens junctions. J. Cell Biol. 219, e201907079 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tachibana K., et al. , Two cell adhesion molecules, nectin and cadherin, interact through their cytoplasmic domain-associated proteins. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1161–1176 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato T., et al. , Regulation of the assembly and adhesion activity of E-cadherin by nectin and afadin for the formation of adherens junctions in madin-darby canine kidney cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5288–5299 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Y., Kanchanawong P., Zaidel-Bar R., Actin-delimited adhesion-independent clustering of E-cadherin forms the nanoscale building blocks of adherens junctions. Dev. Cell 32, 139–154 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckley C. D., et al. , The minimal cadherin-catenin complex binds to actin filaments under force. Science 346, 1254211 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chantret I., et al. , Differential expression of sucrase-isomaltase in clones isolated from early and late passages of the cell line Caco-2: Evidence for glucose-dependent negative regulation. J. Cell. Sci. 107, 213–225 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hell S. W., Wichmann J., Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: Stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 19, 780–782 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uhlén M., et al. , Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodewald R., Newman S. B., Karnovsky M. J., Contraction of isolated brush borders from the intestinal epithelium. J. Cell Biol. 70, 541–554 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drenckhahn D., Localization of myosin, actin, and tropomyosin in rat intestinal epithelium: Immunohistochemical studies at the light and electron microscope levels. J. Cell Biol. 86, 475–482 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinto M., et al. , Enterocyte-like differentiation and polarization of the human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2 in culture. Biol. Cell 47, 323–330 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Duc Q., et al. , Vinculin potentiates E-cadherin mechanosensing and is recruited to actin-anchored sites within adherens junctions in a myosin II–dependent manner. J. Cell Biol. 189, 1107–1115 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knudsen K. A., Soler A. P., Johnson K. R., Wheelock M. J., Interaction of alpha-actinin with the cadherin/catenin cell-cell adhesion complex via alpha-catenin. J. Cell Biol. 130, 67–77 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandai K., et al. , Ponsin/SH3P12: An l-afadin– and vinculin-binding protein localized at cell-cell and cell-matrix adherens junctions. J. Cell Biol. 144, 1001–1018 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto T., et al. , The Ras target AF-6 interacts with ZO-1 and serves as a peripheral component of tight junctions in epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 139, 785–795 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takekuni K., et al. , Direct binding of cell polarity protein PAR-3 to cell-cell adhesion molecule nectin at neuroepithelial cells of developing mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5497–5500 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Izumi Y., et al. , An atypical PKC directly associates and colocalizes at the epithelial tight junction with ASIP, a mammalian homologue of Caenorhabditis elegans polarity protein PAR-3. J. Cell Biol. 143, 95–106 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mangeol P., et al. , Super-resolution imaging uncovers the nanoscopic segregation of polarity proteins in epithelia. eLife 11, e62087 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan B., et al. , The mammalian crumbs complex defines a distinct polarity domain apical of epithelial tight junctions. Curr. Biol. 30, 2791–2804.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ooshio T., et al. , Cooperative roles of Par-3 and afadin in the formation of adherens and tight junctions. J. Cell Sci. 120, 2352–2365 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guillot C., Lecuit T., Mechanics of epithelial tissue homeostasis and morphogenesis. Science 340, 1185–1189 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lecuit T., Lenne P.-F., Cell surface mechanics and the control of cell shape, tissue patterns and morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 633–644 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mooseker M. S., Brush border motility. Microvillar contraction in triton-treated brush borders isolated from intestinal epithelium. J. Cell Biol. 71, 417–433 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fanning A. S., Jameson B. J., Jesaitis L. A., Anderson J. M., The tight junction protein ZO-1 establishes a link between the transmembrane protein occludin and the actin cytoskeleton. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29745–29753 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Itoh M., Nagafuchi A., Moroi S., Tsukita S., Involvement of ZO-1 in cadherin-based cell adhesion through its direct binding to α catenin and actin filaments. J. Cell Biol. 138, 181–192 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen T. P., et al. , Tight junction membrane proteins regulate the mechanical resistance of the apical junctional complex. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2023). 10.1101/2023.08.02.551232 (Accessed 4 August 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Alberts B., et al. , Molecular Biology of the Cell (Garland, New York, 1994), vol. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka-Okamoto M., et al. , Involvement of afadin in barrier function and homeostasis of mouse intestinal epithelia. J. Cell Sci. 124, 2231–2240 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuramitsu K., Ikeda W., Inoue N., Tamaru Y., Takai Y., Novel role of nectin: Implication in the co-localization of JAM-A and claudin-1 at the same cell–cell adhesion membrane domain. Genes Cells 13, 797–805 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez-Rico C., et al. , Separation force measurements reveal different types of modulation of E-cadherin-based adhesion by nectin-1 and -3. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4753–4760 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satoh-Horikawa K., et al. , Nectin-3, a new member of immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecules that shows homophilic and heterophilic cell-cell adhesion activities. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10291–10299 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benjamin J. M., Nelson W. J., Bench to bedside and back again: Molecular mechanisms of α-catenin function and roles in tumorigenesis. Sem. Cancer Biol. 18, 53–64 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vermeulen S. J., et al. , Transition from the noninvasive to the invasive phenotype and loss of α-catenin in human colon cancer cells1. Cancer Res. 55, 4722–4728 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsubara S., Ozawa M., Expression of α-catenin in α-catenin-deficient cells results in a reduced proliferation in three-dimensional multicellular spheroids but not in two-dimensional monolayer cultures. Oncogene 23, 2694–2702 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasioukhin V., Bauer C., Degenstein L., Wise B., Fuchs E., Hyperproliferation and defects in epithelial polarity upon conditional ablation of α-catenin in skin. Cell 104, 605–617 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drees F., Pokutta S., Yamada S., Nelson W. J., Weis W. I., α-catenin is a molecular switch that binds E-cadherin-β-catenin and regulates actin-filament assembly. Cell 123, 903–915 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Citi S., Sabanay H., Jakes R., Geiger B., Kendrick-Jones J., Cingulin, a new peripheral component of tight junctions. Nature 333, 272–276 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamazaki Y., Itoh M., Sasaki H., Furuse M., Tsukita S., Multi-PDZ domain protein 1 (MUPP1) is concentrated at tight junctions through its possible interaction with claudin-1 and junctional adhesion molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 455–461 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ullmer C., Schmuck K., Figge A., Lübbert H., Cloning and characterization of MUPP1, a novel PDZ domain protein. FEBS Lett. 424, 63–68 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bazzoni G., et al. , Interaction of junctional adhesion molecule with the tight junction components ZO-1, cingulin, and occludin. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20520–20526 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ebnet K., Schulz C. U., M.-K. M. zu Brickwedde, G. G. Pendl, D. Vestweber, Junctional adhesion molecule interacts with the PDZ domain-containing proteins AF-6 and ZO-1. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27979–27988 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ebnet K., et al. , The cell polarity protein ASIP/PAR-3 directly associates with junctional adhesion molecule (JAM). The EMBO J. 20, 3738–3748 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Itoh M., et al. , Junctional adhesion molecule (JAM) binds to PAR-3 a possible mechanism for the recruitment of PAR-3 to tight junctions. J. Cell Biol. 154, 491–498 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martínez-Estrada O. M., et al. , Association of junctional adhesion molecule with calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase (CASK/LIN-2) in human epithelial Caco-2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 9291–9296 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Asada M., et al. , ADIP, a novel afadin- and α-actinin-binding protein localized at cell-cell adherens junctions. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4103–4111 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martìn-Padura I., et al. , Junctional adhesion molecule, a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that distributes at intercellular junctions and modulates monocyte transmigration. J. Cell Biol. 142, 117–127 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gulley R. L., Reese T. S., Intercellular junctions in the reticular lamina of the organ of Corti. J. Neurocytol. 5, 479–507 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jahnke K., The fine structure of freeze-fractured intercellular junctions in the guinea pig inner ear. Acta Oto-Laryngolog. 80, 5–40 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nunes F. D., et al. , Distinct subdomain organization and molecular composition of a tight junction with adherens junction features. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4819–4827 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Madara J. L., Trier J. S., Structure and permeability of goblet cell tight junctions in rat small intestine. J. Membrain Biol. 66, 145–157 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Le Bivic A., Evolution and Cell Physiology. 4. Why invent yet another protein complex to build junctions in epithelial cells? Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 305, C1193–C1201 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noirot-Timothée C., Noirot C., “Septate and scalariform junctions in arthropods” in International Review of Cytology, Bourne G. H., Danielli J. F., Jeon K. W., Eds. (Academic Press, 1980), pp. 97–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wood R. L., Intercellular attachment in the epithelium of hydra as revealed by electron microscopy. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 6, 343–352 (1959). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knust E., Bossinger O., Composition and formation of intercellular junctions in epithelial cells. Science 298, 1955–1959 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mandai K., Rikitake Y., Mori M., Takai Y., “Nectins and nectin-like molecules in development and disease” in Current Topics in Developmental Biology, A. S. Yap, Ed. (Elsevier, 2015), pp. 197–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ran F. A., et al. , Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lemmers C., et al. , CRB3 binds directly to Par6 and regulates the morphogenesis of the tight junctions in mammalian epithelial cells. MBoC 15, 1324–1333 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reijerkerk A., et al. , Diapedesis of monocytes is associated with MMP- mediated occludin disappearance in brain endothelial cells. FASEB J. 20, 2550–2552 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mangeol P., et al. , zonula_adherens_matura. GitHub. https://github.com/PierreMangeol/zonula_adherens_matura. Deposited 2 February 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Example of the laser ablation of the apical area of WT Caco-2 cell. Image size: 30.44 μm, time difference between frames: 0.26 s.

Example of the laser ablation of the apical area of afadin-KO Caco-2 cell. Image size: 30.44 μm, time difference between frames: 0.26 s.

Example of the laser ablation of a junction of a WT Caco-2 cell. Image size: 20 × 20 μm, time difference between frames: 0.26 s.

Example of the laser ablation of a junction of an afadin-KO Caco-2 cell. Image size: 20 × 20 μm, time difference between frames: 0.26 s.

Data Availability Statement

Data and codes used to extract information from images and generate graphs are available on GitHub, at https://github.com/PierreMangeol/zonula_adherens_matura (74).