Significance

Photon-controlled pyroptosis activation (PhotoPyro) holds promise for cancer immunotherapy by selectively triggering cell death. Here, we report that biomolecular photoredox catalysis in cells contributes to PhotoPyro. To substantiate this hypothesis, a molecular photocatalyst that absorbs at 730 nm, MLu, along with two analogs containing different central metal cations, MGd and MMn, were tested. Only MLu, in contrast to its analogs, produces reactive oxygen species and acts as a photocatalyst was found to trigger PhotoPyro. This study highlights the pivotal role of photoredox catalysis in PhotoPyro and sets the stage for the further development of photocatalytic approaches to anticancer therapy.

Keywords: photoredox catalysis, pyroptosis, NAD(P)H, NIR photocatalyst, PhotoPyro

Abstract

Photon-controlled pyroptosis activation (PhotoPyro) is a promising technique for cancer immunotherapy due to its noninvasive nature, precise control, and ease of operation. Here, we report that biomolecular photoredox catalysis in cells might be an important mechanism underlying PhotoPyro. Our findings reveal that the photocatalyst lutetium texaphyrin (MLu) facilitates rapid and direct photoredox oxidation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, and various amino acids, thereby triggering pyroptosis through the caspase 3/GSDME pathway. This mechanism is distinct from the well-established role of MLu as a photodynamic therapy sensitizer in cells. Two analogs of MLu, bearing different coordinated central metal cations, were also explored as controls. The first control, gadolinium texaphyrin (MGd), is a weak photocatalyst but generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) efficiently. The second control, manganese texaphyrin (MMn), is ineffective as both a photocatalyst and a ROS generator. Neither MGd nor MMn was found to trigger pyroptosis under the conditions where MLu was active. Even in the presence of a ROS scavenger, treating MDA-MB-231 cells with MLu at concentrations as low as 50 nM still allows for pyroptosis photo-activation. The present findings highlight how biomolecular photoredox catalysis could contribute to pyroptosis activation by mechanisms largely independent of ROS.

The development of photo-triggered modalities, such as photodynamic therapy (PDT) and photothermal therapy, has had a transformative impact on the biomedical landscape while opening up new avenues for research and therapeutic development (1–10). Among the various light-based therapeutic techniques currently being explored, especially appealing are those involving photoredox catalysis. Photoredox catalysis was initially employed in organic synthesis (11, 12); however, in recent years, efforts have been made to repurpose photoredox chemistry for biomedical applications. These efforts have led to a series of revolutionary advances, including inter alia photocatalytic cell tagging (13), proximity protein labeling (14–16), chromatin state tracking (17), and modulation of intracellular electron homeostasis for cancer cell eradication (18–20). Inspired by this, we and others are motivated to expand further the potency of artificial photoredox catalysis. Here, we show that photoredox catalysis can serve as a trigger for cancer cell pyroptosis. We also report that a specific near-infrared (NIR) photoredox catalyst (PC), referred to as MLu (Fig. 1D), induces pyroptosis via a biomolecular photoredox-based catalytic mechanism of action (MoA).

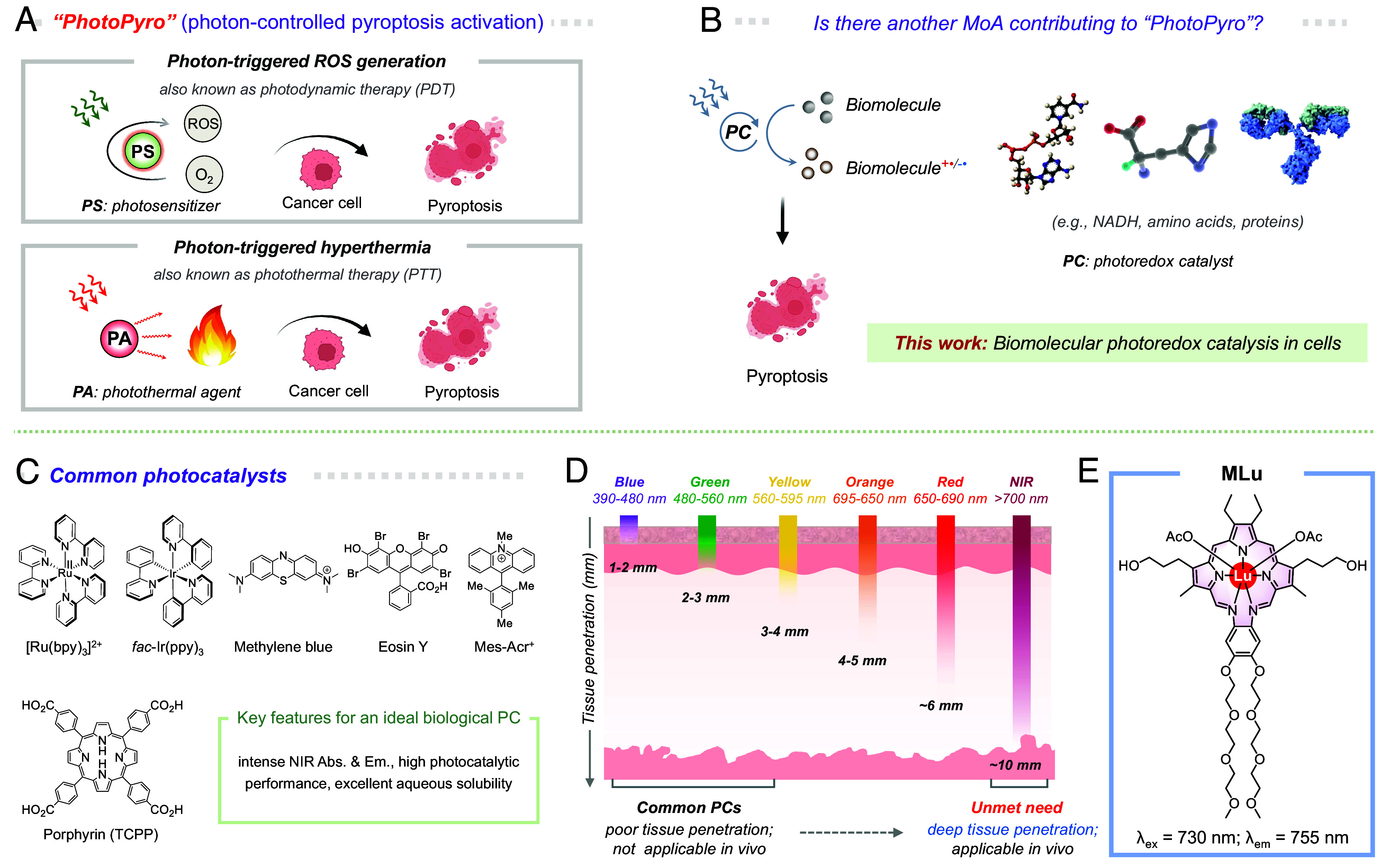

Fig. 1.

Cell pyroptosis activation by 730 nm light-induced photoredox catalysis in cells. (A) Schematic illustration of the common photochemical MoAs involved in PhotoPyro, including photon-triggered ROS generation and photon-triggered hyperthermia; however, (B) we suggest here that biomolecular photoredox catalysis may serve as an additional MoA contributing to PhotoPyro. Figure created with Biorender.com. (C) Illustration of commonly used photocatalysts in photoredox catalysis and the key features desired for an ideal biological PC. (D) Different wavelengths of light exhibit varying tissue penetration depths. Typically, high-energy light has limited tissue penetration, whereas longer-wavelength light, particularly in the NIR range, can penetrate deeper into tissues. This makes NIR photoillumination more suitable for biomedical applications. (E) Chemical structure of the NIR PC, MLu, and its key photophysical properties.

Pyroptosis is a distinct proinflammatory form of cell death that differs from conventional programmed cell death (PCD) modalities like apoptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis (21). It is characterized by the formation of pores on the cell membrane mediated by gasdermin proteins (GSDMs), which trigger cell swelling, membrane damage, and the release of intracellular components (22). Since the discovery of GSDMs as key mediators of pyroptosis in 2015 (23, 24), this unique form of cell death has garnered increasing attention, particularly in the field of cancer therapy, where it is being explored as a potential novel approach to antitumor immunotherapy (25–28). Compared with other forms of PCD like apoptosis, pyroptosis is more likely to elicit immune responses by triggering the release of intracellular proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1b and IL-18 (29). Not surprisingly, therefore, efforts are being devoted to the development of strategies to activate pyroptosis. However, pyroptosis is a double-edged sword. While pyroptosis induction can “heat” so-called “immune-cold” tumors to promote antitumor immunity, it can also trigger a “cytokine storm,” leading to tissue damage (26, 30). At present, methods to induce pyroptosis have mainly concentrated on chemotherapeutic agents like lobaplatin, paclitaxel, and metformin (31, 32). Unfortunately, many of these agents are plagued by serious side effects and are subject to drug resistance. There is thus a need for new modalities that allow for the accurate and controlled triggering of pyroptosis in vivo.

Recently, we and others have focused on the use of light to control pyroptosis induction (33–37), an approach we have termed “photon-controlled pyroptosis activation” or simply PhotoPyro (38). This technique holds great promise as being relatively noninvasive and allows for precise spatiotemporal control. However, in spite of its potential, the identification of effective PhotoPyro inducers remains a challenge. This may reflect our limited understanding of the potential MoAs of PhotoPyro. Currently, photon-controlled reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and photon-controlled hyperthermia (38) are viewed as being the primary triggers of PhotoPyro (cf., Fig. 1A). To the extent these MoAs dominate, it would largely restrict the design and development of PhotoPyro inducers to photosensitizers and photothermal agents. We thus questioned whether other MoAs might exist that could be harnessed to achieve PhotoPyro. The current investigation was initiated with the intention to answer this question. As detailed below, using the lutetium texaphyrin complex, MLu, as a PC, we have found that “biomolecular photoredox catalysis in cells” constitutes an under-explored MoA that can contribute to the activation of pyroptosis (Fig. 1B). In particular, we found that photo-activation of MLu induces the photoredox-based oxidation of key biomolecules, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and various amino acids (Fig. 2) and that the resulting alterations in cellular homeostasis contribute to PhotoPyro via a mechanism distinct from previous ROS- and hyperthermia-based MoAs. Specifically, at low dosages (e.g., 50 nM), MLu induces cancer cell pyroptosis upon 730 nm photoirradiation by activating the caspase 3/GSDME pathway. The present findings provide a proof-of-concept demonstration that photoredox catalysis can stimulate cell pyroptosis.

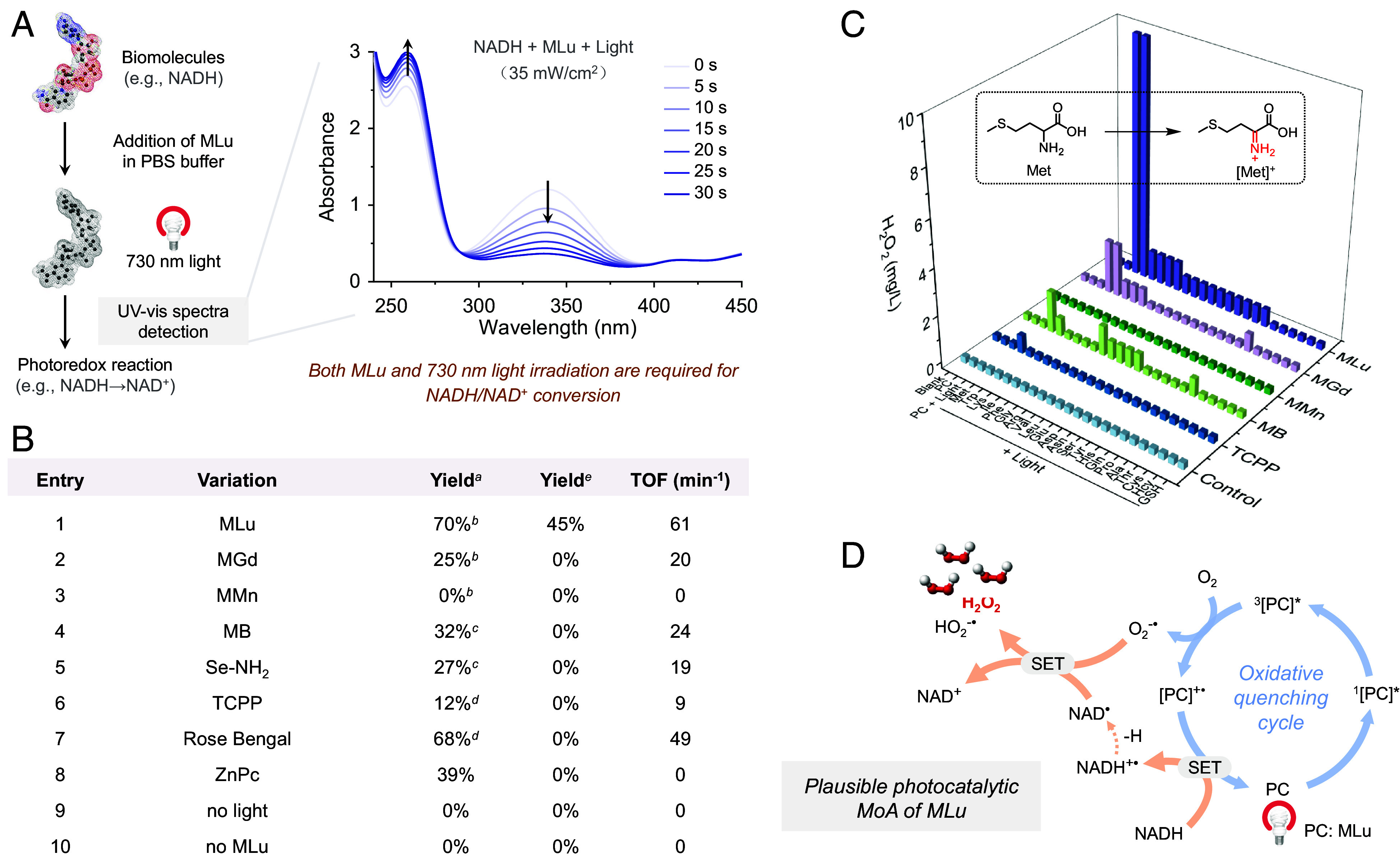

Fig. 2.

Photoredox catalytic properties of MLu. (A) UV-vis spectral studies provide support for the photocatalytic conversion of NADH to NAD+ by MLu. (B) Tests of various systems as PCs for the photocatalytic production of NAD+. aYield of NAD+ determined after 30 s photoirradiation of 180 μM NADH in the presence of 5 μM of the indicated PC in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (10 mM, pH ~ 7.4) containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) under air. bPhoton source: 730 nm LED lamp. cPhoton source: 660 nm LED lamp. dPhoton source: White LED lamp. Light power density: 35 mW/cm2. eYield of NAD+ determined after 120 s 808 nm photoirradiation (100 mW/cm2) of 180 μM NADH in the presence of 5 μM of the indicated PC in PBS (10 mM, pH ~ 7.4) containing 10% DMSO under air. (C) Photocatalytic reactions with amino acids were investigated by measuring H2O2 generation using H2O2 test sticks. (D) Proposed catalytic cycle. Abbreviations: TOF, turnover frequency; TCPP, tris(1-chloro-2-propyl)phosphate; ZnPc, zinc phthalocyanine; MB, methylene blue; Met, methionine; SET, single electron transfer.

Results and Discussion

Photoredox Catalytic Properties of MLu.

Photoredox catalysis requires, as the name implies, an effective photocatalyst. Most PCs in current use are based either on transition-metal complexes (e.g., Ru, Ir) or redox active dyes, such as methylene blue (MB), Eosin Y, and Mes-Acr+ (Fig. 1C) (12). Many of these PCs were originally developed for synthetic purposes and are characterized by visible wavelength absorption features. However, the relatively high energy nature of their absorption maxima limit their use in biological applications, including PhotoPyro (39). For in vivo use, absorption in the NIR spectral region (>700 nm) is preferred since better through-tissue light penetration can be achieved and the risk of acute photo-damaged is reduced (Fig. 1D). Unfortunately, the number of reported NIR PCs is limited (40–42). Here, we show that a water-solubilized lutetium texaphyrin, MLu (43–45) (for structure, see Fig. 1E), acts as an effective and benign PC that can catalyze photoredox reactions, including those associated with PhotoPyro, within living cells when subject to 730 nm photoexcitation.

We began our studies by reconfirming the photophysical properties of MLu. As summarized in SI Appendix, Fig. S1, in our hands, MLu displayed a large broad absorption band centered at 730 nm, with a molar extinction coefficient of 4.47 × 104 M–1 cm–1 when tested as a 5 μM solution in PBS (10 mM, pH ~ 7.4) containing 10% DMSO. Upon excitation at 730 nm, a fluorescence emission at 755 nm was seen. MLu also demonstrated good water solubility and high stability under model physiological conditions (PBS, 10 mM, pH ~ 7.4). For instance, no evidence of precipitation was seen after incubating for 5 d in PBS (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Moreover, negligible photolysis was seen when MLu was subject to photoirradiation for 30 min at 730 nm (35 mW/cm2) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

The photocatalytic activity of MLu was then investigated. Upon photoexcitation for 30 s at 35 mW/cm2 (730 nm), MLu produces ROS, including singlet oxygen (1O2, SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5) and superoxide radicals (O2•−, SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7) effectively. Such findings are in accord with prior studies of MLu as a possible PDT sensitizer (43). However, in contrast to what was noted earlier, we have now found that upon photoirradiation MLu can directly trigger various biomolecular transformations. For instance, subjecting MLu (5 μM in PBS containing 10% DMSO) to 30 s of photoirradiation (730 nm, 35 mW/cm2) induces the photoredox-based transformation of NADH (180 μM) into NAD+ (Fig. 2A), as inferred from the decline in the absorbance at 339 nm (a characteristic peak of NADH) and the corresponding increase in absorbance at 260 nm (a characteristic peak of NAD+) (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). A ln plot of the absorbance at 339 nm against the irradiation time demonstrated conformity with the kinetics of a first-order reaction (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). The TOF for this conversion was calculated to be approximately 61 min−1. This value is higher than that seen for conventional organic PCs, such as MB, Rose Bengal, tris(1-chloro-2-propyl)phosphate (TCPP), zinc phthalocyanine (ZnPc), and Se-NH2 (20) (cf., Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Control experiments carried out in the absence of MLu or 730 nm photoirradiation revealed no discernable production of NAD+ (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). When a longer wavelength 808 nm LED light source was used to illuminate the reaction mixture, photocatalytic conversion of NADH to NAD+ was still observed, albeit with a lower reaction rate (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S12). In addition to acting as a PC for NADH photooxidation, MLu was also found to facilitate the photoredox oxidation of other biomolecules, including NADPH (SI Appendix, Fig. S13) and certain amino acids, namely Met, Trp, Lys, and Phe (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Scheme S1). Considering the vital roles these molecules play in cellular functions, such as the prominent role of NAD(P)H in mediating oxidoreductase activity (46, 47) and the key role of amino acids in biosynthesis, we anticipated that the photoredox conversions triggered by MLu might translate into a PhotoPyro effect. We thus sought to explore its putative MoA in greater detail.

In general, for effective photocatalysis, an intermediate form of the catalyst must undergo conversion back to its initial active state (48). In the case of MLu, it was anticipated that dissolved O2 would act as an electron acceptor and react with photoexcited MLu to give the radical cation MLu+•, which would in turn extract one electron from NADH to regenerate the starting MLu while producing NAD+. The photocatalytic features of MLu were thus tested under deoxygenated conditions. In contrast to what was seen under a normal laboratory atmosphere, when an NADH-containing PBS solution of MLu was deaerated using N2 and subject to photoirradiation, nearly no NAD+ production was detected, with the TOF to be a mere 3.6 min−1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Based on these findings, we infer that the presence of O2 is imperative for the completion of the catalytic cycle. Considering previous studies (18), an O2-dependent oxidative quenching cycle operating via a SET mechanism is thus thought to account for the photoredox conversion of NADH to NAD+ in the presence of MLu and air (Fig. 2D).

Photoredox Catalysis of MLu in Cells.

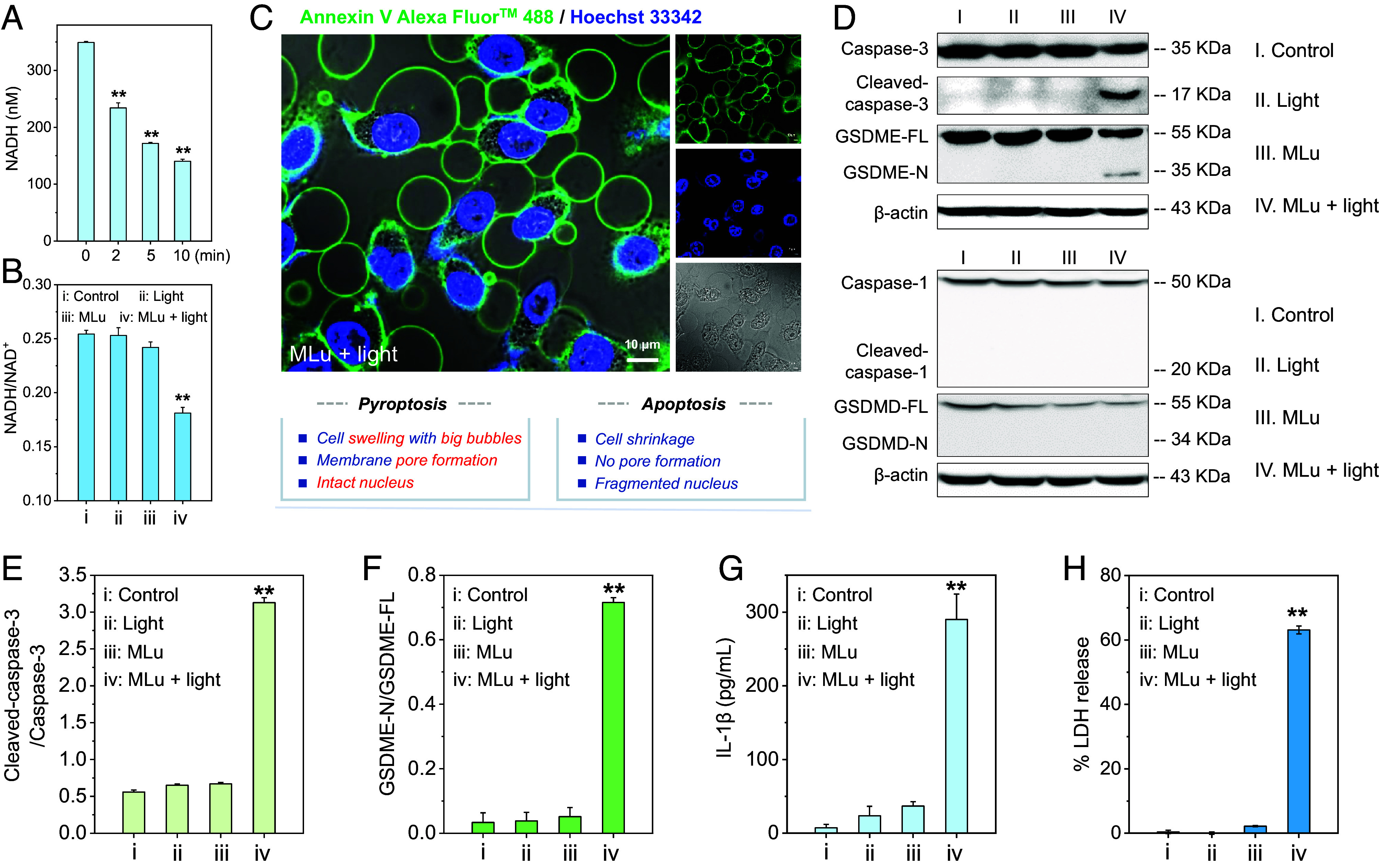

The photoredox mechanism was further investigated in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells, with a specific focus on the involvement of NADH and NAD+. At a concentration of 50 nM, MLu was found active as an NADH conversion photocatalyst, producing a statistically significant depletion of NADH levels in this cell line in a time-dependent manner (730 nm, 100 mW/cm2). For instance, a 32.9 ± 2.5% decrease in NADH was seen after 2 min of irradiation, with a 50.8 ± 0.5% decrease observed after 5 min (Fig. 3A). Consequently, the NADH/NAD+ ratio in cells declined. In contrast, treatment with MLu without photoirradiation produced a negligible effect on NADH levels (Fig. 3B). Replacing NADH with NADPH gave concordant results (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). An appropriate NADH/NAD+ balance is considered essential for the maintenance of crucial cellular processes, including cellular metabolism and the function of key organelles, such as the mitochondria (49). Given this, we speculated that the collapse of NADH levels induced by MLu-mediated photoredox catalysis would lead to cellular dysfunction thus triggering cell death. Consistent with this notion, cells treated with 50 nM MLu and exposed to 730 nm light irradiation for 2 min (100 mW/cm2) displayed reduced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. This was taken as evidence of disrupted mitochondrial respiration (SI Appendix, Fig. S16). A pronounced depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential was also observed by means of a JC-1 assay (SI Appendix, Fig. S17). These effects were, in turn, expected to give rise to a distinct antitumor MoA that differs from the acute ROS-mediated oxidative stress mechanisms that are the hallmarks of more conventional phototherapeutic modalities, such as PDT (50).

Fig. 3.

MLu-initiated cell pyroptosis activation. (A) Cellular NADH levels in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with MLu (50 nM) and subjected to light irradiation for different times (730 nm, 100 mW/cm2). (B) Change in the cellular NADH/NAD+ ratio seen under the indicated treatment protocols. MLu: 50 nM. Light: 730 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 2 min. (C) Confocal images of Annexin-V-Alexa FluorTM 488-positive bubbling vesicles in MDA-MB-231 cells observed after treatment with 50 nM MLu and 730 nm photoirradiation for 2 min (100 mW/cm2). The nucleus is labeled with Hoechst 33342. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (D) Immunoblot analysis of pyroptosis-related protein expression and corresponding statistical analysis of (E) cleaved-caspase 3 and (F) GSDME-N protein levels. (G) Release of IL-1β and (H) LDH in MDA-MB-231 cells following MLu-initiated pyroptosis activation. Light conditions for D–H: 730 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 2 min. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3), **P < 0.01.

Pyroptosis Activation via GSDME Cleavage.

In previous studies of MLu as a PDT sensitizer, cell death was primarily attributed to ROS-induced apoptosis (51, 52). However, we have now found evidence of pyroptosis activation when MDA-MB-231 cells are treated with MLu and exposed to photoirradiation (730 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 2 min). Specifically, confocal laser scanning microscopy revealed inter alia rapid peripheral swelling, bubbles originating from the cell membrane [as highlighted by green fluorescence staining using Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugate], and intact nuclei (as highlighted by blue fluorescence staining using Hoechst 33342) (Fig. 3C). These patterns differ from those characteristic of apoptosis, which include cell shrinkage, fragmented nuclei, and the formation of apoptotic bodies (53). MLu alone without 730 nm irradiation had a minimal impact on the cell morphology (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). Based on these results, we conclude that under phototherapy, MLu may trigger mechanisms of cell death that are more complex than originally appreciated.

Further analysis using a western blot assay revealed that MLu triggers pyroptosis through the activation of GSDME. The expression levels of the active form of caspase 3 (cleaved-caspase 3) and the N-terminal domain of GSDME (pore-forming domain) were increased in a statistically significant manner in MDA-MB-231 cells following presumed MLu-mediated PhotoPyro (Fig. 3 D–F). These findings are consistent with previous reports suggesting that cleaved-caspase 3 directly promotes the cleavage of GSDME (31). No cleaved-GSDMD (N-GSDMD) or cleaved-caspase 1 was observed upon treatment with MLu and subjecting to photoirradiation (Fig. 3D). This leads us to conclude that MLu-induced pyroptosis activation occurs through the caspase 3/GSDME pathway rather than the caspase 1/GSDMD pathway typically associated with pyroptosis activation.

Considering the expectation that GSDME pore formation on the cell membrane could trigger the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18 (54, 55), we tested whether excreted IL-1β was present in the cell culture supernatant of MDA-MB-231 cells under various test conditions. As expected, and in contrast to the relatively low level of IL-1β release in the control group (7.3 ± 4.7 pg/mL), a significant increase in IL-1β was seen in the culture medium after MLu + light treatment (290 ± 34.5 pg/mL), a finding we take as evidence for the formation of membrane pores (Fig. 3G). Additionally, intracellular lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), another hallmark of pyroptosis, was also observed to be released into the extracellular medium (~63.1 ± 1.2% release as seen for the MLu + light group; Fig. 3H). These findings provide support for the hypothesis that MLu is an effective PC that can induce PhotoPyro under conditions of NIR photoillumination, thus triggering pyroptosis in cancer cells.

Biomolecular Photoredox Catalysis Contributes to Pyroptosis Activation.

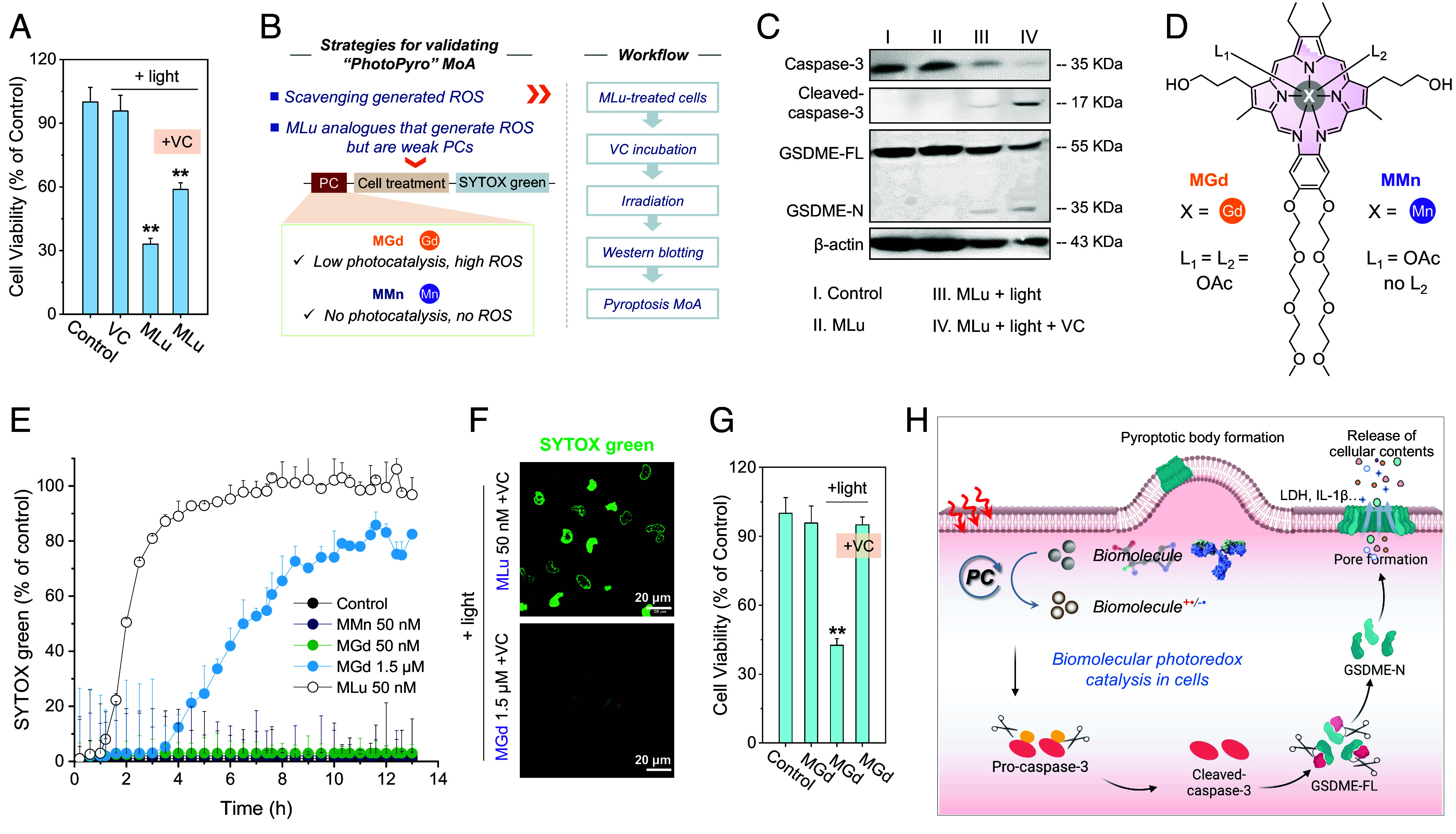

Next, we tested the antiproliferation effects of MLu and photoirradiation in MDA-MB-231 cells, employing a standard water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST-8) assay. As noted previously, upon photoirradiation, MLu sensitizes ROS production and promotes photoredox catalysis. Not surprisingly, therefore, the combination of MLu and light resulted in a robust antiproliferation effect in MDA-MB-231 cells. For instance, when MLu at a concentration of 50 nM was subject to 730 nm photoillumination (100 mW/cm2, 2 min), approximately 66.9% cell death was observed. A subsequent ROS scavenging assay using excess Vitamin C (VC) as a ROS scavenger (28) (10,000 equivalents relative to MLu) revealed that 25.8% of the cells were rescued, leading us to propose that MLu-mediated photoredox catalysis accounts for ~40% of the observed cell death (Fig. 4A). Again, this finding is consistent with the suggestion that biomolecular photoredox catalysis contributes to pyroptosis induction.

Fig. 4.

Biomolecular photoredox catalysis may contribute to PhotoPyro. (A) Cell viability of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with MLu (50 nM) and subjected to photoirradiation (730 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 2 min). Vitamin C (VC) was used as a ROS scavenger. (B) Strategy and control experiments were used to test the notion that biomolecular photoredox catalysis may be involved in PhotoPyro. (C) Western blot assay providing evidence for the activation of cell pyroptosis after scavenging photogenerated ROS in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with MLu (50 nM) and light (730 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 2 min). (D) Chemical structures of control molecules MGd and MMn. (E) Time-dependent SYTOX green uptake of MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with the indicated compound and subjecting to photoirradiation (730 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 2 min). SYTOX green is a membrane-impenetrable probe that is normally nonfluorescent but can penetrate damaged cells to locate in the nucleus and emit in the green fluorescence channel. (F) Confocal imaging of SYTOX green in MDA-MB-231 cells. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (G) Comparison of cell viability in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with MGd (1.5 μM) in the presence or absence of VC (0.5 mM). (H) Schematic representation of the proposed MoA of PhotoPyro involving biomolecular photoredox catalysis in cells. The figure was created using Biorender.com. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3), **P < 0.01.

Support for the above conclusion came from several proof-of-concept experiments. The first of these involved the use of VC to scavenge generated ROS. Following the workflow depicted in Fig. 4B, western blot analyses revealed that when the standard MLu photoirradiation studies were carried out in the presence of VC, cleavage of caspase 3 and GSDME was still observed (Fig. 4C). Such a finding is consistent with the overarching design hypothesis underlying the present study, namely that photoredox catalysis of biomolecules such as NAD(P)H and amino acids contribute to pyroptosis activation. Next, studies were carried out using analogs of MLu that were expected to be less effective photocatalysts (Fig. 4B), namely MMn and MGd (molecular structures in Fig. 4D). MMn is a recognized photothermal agent but is ineffective as a photocatalyst for the generation of ROS. In contrast, MGd generates ROS under conditions of redox cycling but is likewise ineffective as a PC (Fig. 2 B and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S19–S21). To compare these three texaphyrin derivatives, studies were carried out using SYTOX green as an indicator of membrane damage (27). While MLu at a concentration of 50 nM induced rapid membrane damage under the conditions of 730 nm light irradiation (100 mW/cm2, 2 min), as indicated by the sharp increase in the SYTOX green signal in cells (Fig. 4E and SI Appendix, Fig. S22), neither MMn nor MGd had a discernible effect under otherwise identical experimental conditions (Fig. 4E). When the dose of MGd was increased by 30× fold (i.e., to 1.5 μM), some evidence of possible pyroptosis induction was observed (Fig. 4E). However, the use of VC as a ROS scavenger resulted in a near-total rescue of this membrane damage (Fig. 4F and SI Appendix, Figs. S23 and S24), along with reduced cell death (Fig. 4G). This stands in marked contrast to the observations made in the case of MLu. As noted above, even in the presence of a ROS scavenger (VC), MLu still triggered pyroptosis (Fig. 4F and SI Appendix, Figs. S23 and S24). We thus conclude that the MoA for MLu under photoillumination involves, at least in part, biomolecular photoredox catalysis-mediated PhotoPyro, as suggested in Fig. 4H.

Anticancer Properties of MLu.

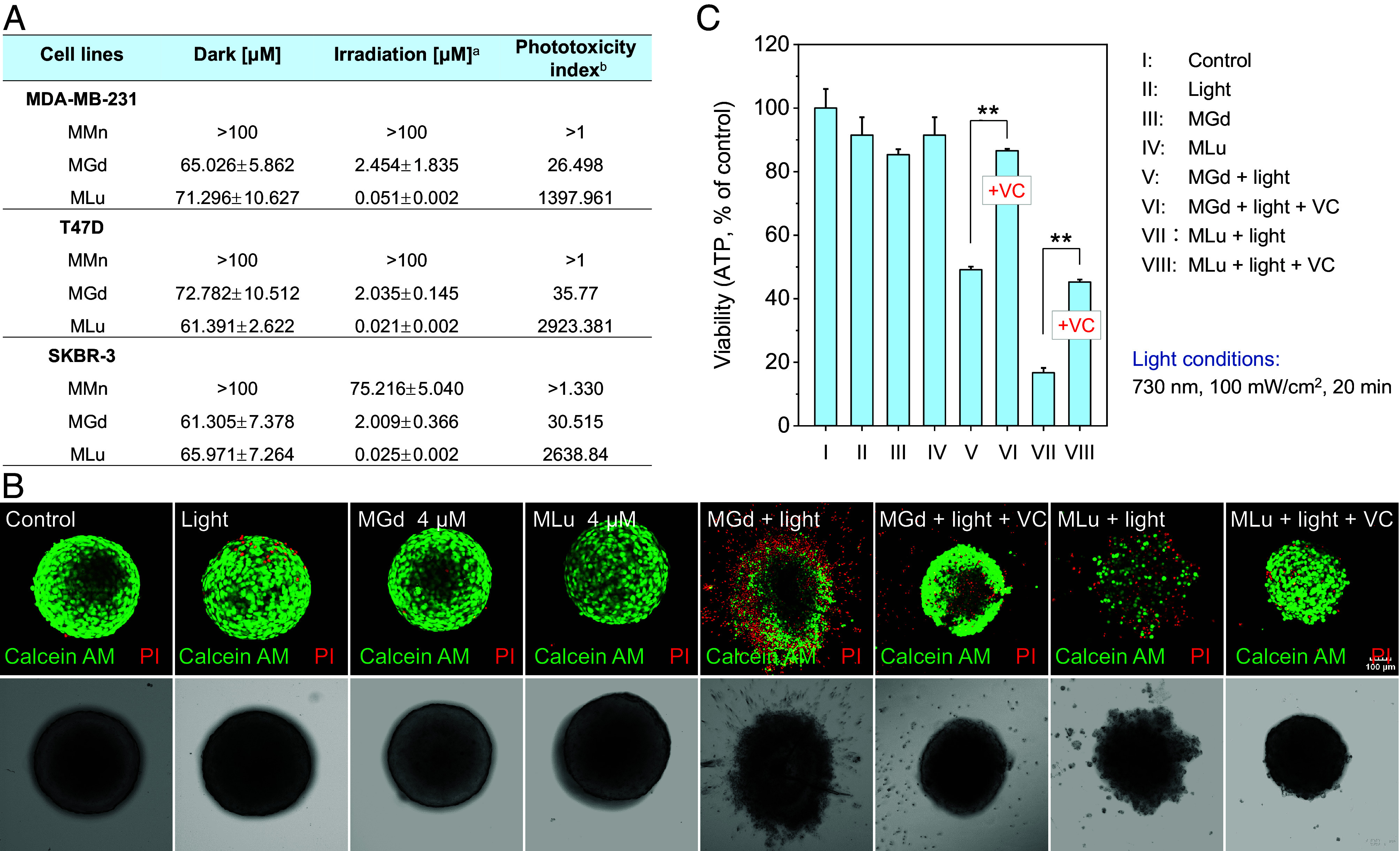

Encouraged by the above findings, we evaluated the anticancer activity of MLu in several breast cancer cell lines. In accord with our design expectations, MLu exhibited anticancer activity not only in the MDA-MB-231 cells but also in the T47D and SKBR-3 cell lines. The concentration required to achieve a 50% inhibition of cell growth (referred to as the IC50 value) proved to be in the nanomolar range (Fig. 5A). For example, under the conditions of 730 nm photoirradiation for 2 min (100 mW/cm2), an IC50 of 21 nM was recorded for MLu. This value is nearly 98-fold lower than that seen for MGd. The photocytotoxicity index, calculated as (IC50) dark/(IC50) light, an important parameter used to analyze phototherapeutics for possible clinical translation, was found to be as high as 2920 in T47D cells. This large value supports the contention that MLu would possess good biosafety in cells.

Fig. 5.

Anticancer properties of MLu. (A) Cytotoxicity (IC50, μM) of the tested compounds (MLu, MMn, and MGd) in the MDA-MB-231, T47D, and SKBR-3 breast cancer cell lines in the absence or presence of 730 nm photoirradiation. aIrradiation details: 730 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 2 min. bPhototoxicity index was calculated as the ratio of the dark IC50/light IC50. (B) Confocal imaging of live/dead cells in T47D 3D multicellular spheroids (MCSs) after the indicated treatments. Irradiation details: 730 nm, 100 mW/cm2, 20 min. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (C) Antiproliferative studies of MLu in T47D 3D MCSs as determined using an ATP luminescence assay kit. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3), **P < 0.01.

Three-dimensional (3D) mutilcellular spheroids (MCSs) have proven to be a valuable tool for studying antitumor drug discovery efforts due to their complexity that falls intermediate between that of 2D cell culture systems and in vivo tumor models. MCSs are thus of interest in terms of recapitulating the solid tumor microenvironment. In light of this, we evaluated the effect of MLu-mediated PhotoPyro on T47D 3D MCSs with a diameter ranging from 400 to 500 μm. Confocal imaging was employed to observe live cells (green fluorescence, stained by Calcein AM) and dead cells [red fluorescence, stained by propidium iodide (PI)] within the 3D spheroids. Due to their unlimited self-renewing characteristics, T47D cells readily formed 3D multicellular spheroids (Fig. 5B). When the resulting T47D 3D MCSs were treated with MLu followed by 730 nm photoirradiation (100 mW/cm2, 20 min), a collapse in the 3D structure was seen. Under these conditions, the PI signals increased significantly relative to various control groups, indicating the good antitumor ability of MLu. VC pretreatment did not influence markedly the antitumor performance of MLu (Fig. 5B). In the case of MGd, however, VC incubation largely inhibited its anti-MCS ability under conditions of light irradiation (Fig. 5 B and C). Considering these findings, we propose that the combination of MLu and light effectively ablates MCSs and that PhotoPyro induction underlies much of the observed antiproliferative effect.

Conclusion

In summary, we suggest that biomolecular photoredox catalysis in cells may contribute to PhotoPyro. Mechanistic studies revealed that upon excitation at 730 nm, MLu could initiate the photoredox-driven conversion of biomolecules, including NADH, NADPH, and various amino acids, such as Met, Trp, Lys, and Phe, to various daughter products. Given the critical role biomolecular homeostasis plays in governing cellular functions, it was expected that the combination of MLu and light would lead to a readily discernible alteration in cellular physiology and metabolism and likely trigger pyroptosis. Indeed, we found that at relatively low concentrations (e.g., 50 nM), MLu effectively induces cancer cell pyroptosis upon 730 nm photoirradiation and does so by activating the caspase 3/GSDME pathway. Two analogs of MLu, namely MGd and MMn, were tested as controls, with the results providing support for the conclusion that cancer cell pyroptosis activation, as opposed to simple ROS production, underlies in part the antiproliferative effects of MLu seen under conditions of photoirradiation. Based on the current findings, we suggest that photoredox catalysis may 1) serve as a catalytic MoA for photoirradiation-based pyroptosis activation (i.e., PhotoPyro) and 2) provide an entry into the design of next-generation cancer treatments. This research also highlights what could emerge as an important clinical application of MLu, namely as a trigger for photoinduced cancer immunotherapy.

Materials and Methods

SI Appendix of this work contains detailed information about the experimental protocols, including solution tests, photoredox biomolecular catalysis studies, cell culture analyses, and instrument specifications. Unless otherwise specified, commercially available reagents and assay kits were used directly without purification or other modifications.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support received from the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea (project nos. 2018R1A3B1052702, J.S.K. and RS-2023-00241100, Y.X.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project No. 82203050, Y.X.). We also thank the Brain Pool Program administered through the NRF of Korea (grant no. 2020H1D3A1A02080172, M.L.), Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22308220, M.L.), Shenzhen University Third-Phase Project of Constructing High-Level University (No. 000001032104, M.L.), Research Team Cultivation Program of Shenzhen University (No. 2023QNT005, M.L.), and the Shenzhen University 2035 Program for Excellent Research (00000225 to X.P.). The work in Austin was supported by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-0018 to J.L.S.) and the NIH (CA 68682, J.L.S.) subsequent to June of 2022.

Author contributions

Y.X., M.L., X.P., J.S.K., and J.L.S. designed research; Y.X., C.V.C., J.L., A.C.S., and L.Y., performed research; and Y.X., X.P., J.S.K., and J.L.S. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

J.L.S. is a cofounder of a new startup, InnovoTEX, Inc. As yet, the position in uncompensated, either with money or stock. However, in the near future an equity grant is anticipated. No funding from InnovoTEX comes to J.L.S.’s or any of the authors’ laboratories.

Footnotes

Reviewers: L.H., Nankai University; and G.L., Nantong University.

Contributor Information

Mingle Li, Email: limingle@szu.edu.cn.

Xiaojun Peng, Email: xjpeng@szu.edu.cn.

Jong Seung Kim, Email: jongskim@korea.ac.kr.

Jonathan L. Sessler, Email: sessler@cm.utexas.edu.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or provided in the SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Ryu K. A., Kaszuba C. M., Bissonnette N. B., Oslund R. C., Fadeyi O. O., Interrogating biological systems using visible-light-powered catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5, 322–337 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong H., et al. , Photo-controllable biochemistry: Exploiting the photocages in phototherapeutic window. Chem 9, 29–64 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hüll K., Morstein J., Trauner D., In vivo photopharmacology. Chem. Rev. 118, 10710–10747 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Y., et al. , Photodynamic Alzheimer’s disease therapy: From molecular catalysis to photo-nanomedicine. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 470, 214726 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li M., et al. , Superoxide radical photogenerator with amplification effect: Surmounting the Achilles’ heels of photodynamic oncotherapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2695–2702 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li M., et al. , De novo design of phototheranostic sensitizers based on structure-inherent targeting for enhanced cancer ablation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 15820–15826 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li G., et al. , Recent progress in the development of singlet oxygen carriers for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 478, 214979 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Z., Zhang L., Zhang Z., Liu Z., Advances in photosensitizer-related design for photodynamic therapy. Asian J. Pharm. 16, 668–686 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H., Qiao C., Guan Q., Wei M., Li Z., Nanoparticle-mediated synergistic anticancer effect of ferroptosis and photodynamic therapy: Novel insights and perspectives. Asian J. Pharm. 18, 100829 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi X., Duan Q.-Y., Wu F.-G., Low-temperature photothermal therapy: Strategies and applications. Research 2021, 9816594 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero N. A., Nicewicz D. A., Organic photoredox catalysis. Chem. Rev. 116, 10075–10166 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw M. H., Twilton J., MacMillan D. W. C., Photoredox catalysis in organic chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 81, 6898–6926 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oslund R. C., et al. , Detection of cell-cell interactions via photocatalytic cell tagging. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 850–858 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geri J. B., et al. , Microenvironment mapping via Dexter energy transfer on immune cells. Science 367, 1091–1097 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tay N. E. S., et al. , Targeted activation in localized protein environments via deep red photoredox catalysis. Nat. Chem. 15, 101–109 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li M., Xu Y., Rhee H.-W., Kim J. S., Deep-red-light photocatalytic protein proximity labeling. Chem 8, 3171–3174 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seath C. P., et al. , Tracking chromatin state changes using nanoscale photo-proximity labelling. Nature 616, 574–580 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang H., et al. , Targeted photoredox catalysis in cancer cells. Nat. Chem. 11, 1041–1048 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M., et al. , Photoredox catalysis may be a general mechanism in photodynamic therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2210504119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M., et al. , Conditionally activatable photoredox catalysis in living systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 163–173 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao W., Wang X., Zhou Y., Wang X., Yu Y., Autophagy, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis in tumor immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 7, 196 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao F., Gasdermins: Making pores for pyroptosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 620–621 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi J., et al. , Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 526, 660–665 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kayagaki N., et al. , Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature 526, 666–671 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L., et al. , Pyroptosis, a new bridge to tumor immunity. Cancer Sci. 112, 3979–3994 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minton K., Pyroptosis heats tumour immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 274–275 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z., et al. , Gasdermin E suppresses tumour growth by activating anti-tumour immunity. Nature 579, 415–420 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y., Zhen W., Wang Y., Song S., Zhang H., Na2S2O8 nanoparticles trigger antitumor immunotherapy through reactive oxygen species storm and surge of tumor osmolarity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 21751–21757 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou J., Hsu J.-M., Hung M.-C., Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis in inflammation and antitumor immunity. Mol. Cell 81, 4579–4590 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun W., Liu S., Huang X., Yuan R., Yu J., Cytokine storms and pyroptosis are primarily responsible for the rapid death of mice infected with pseudorabies virus. Roy. Soc. Open Sci. 8, 210296 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y., et al. , Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature 547, 99–103 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L., et al. , Metformin induces human esophageal carcinoma cell pyroptosis by targeting the miR-497/PELP1 axis. Cancer Let. 450, 22–31 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu M., et al. , Activation of pyroptosis by membrane-anchoring AIE photosensitizer design: New prospect for photodynamic cancer cell ablation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9093–9098 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu L., et al. , Photocatalytic superoxide radical generator that induces pyroptosis in cancer cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 11326–11337 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen B., et al. , A pyroptosis nanotuner for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 788–798 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li M., Kim J., Xu Y., Kim J. S., An acid-activatable nanosensitizer library realizes tunable pyroptosis activation in tumors. Matter 6, 15–18 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu X., et al. , Neutrophil camouflaged stealth nanovehicle for photothermal-induced tumor immunotherapy by triggering pyroptosis. Adv. Sci. 10, 2207456 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li M., et al. , Photon-controlled pyroptosis activation (PhotoPyro): An emerging trigger for antitumor immune response. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6007–6023 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mei L., Veleta J. M., Gianetti T. L., Helical carbenium ion: A versatile organic photoredox catalyst for red-light-mediated reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12056–12061 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravetz B. D., et al. , Photoredox catalysis using infrared light via triplet fusion upconversion. Nature 565, 343–346 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obah Kosso A. R., Sellet N., Baralle A., Cormier M., Goddard J.-P., Cyanine-based near infra-red organic photoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci. 12, 6964–6968 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ravetz B. D., et al. , Development of a platform for near-infrared photoredox catalysis. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 2053–2059 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sessler J. L., et al. , Biomedical applications of lanthanide(III) texaphyrins: Lutetium(III) texaphyrins as potential photodynamic therapy photosensitizers. J. Alloy. Compd. 249, 146–152 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young S. W., et al. , Lutetium texaphyrin (PCI-0123): A near-infrared, water-soluble photosensitizer. Photochem. Photobiol. 63, 892–897 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blumenkranz M. S., et al. , Lutetium texaphyrin (Lu-Tex): A potential new agent for ocular fundus angiography and photodynamic therapy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 129, 353–362 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiarugi A., Dölle C., Felici R., Ziegler M., The NAD metabolome—A key determinant of cancer cell biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 741–752 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li G., et al. , NAD(P)H: Quinone oxidoreductase 1 activatable toll-like receptor 7/8 agonist designed for precise immunotherapy. Chem. Commun. 59, 6343–6346 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li B. X., et al. , Site-selective tyrosine bioconjugation via photoredox catalysis for native-to-bioorthogonal protein transformation. Nat. Chem. 13, 902–908 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Navas L. E., Carnero A., NAD+ metabolism, stemness, the immune response, and cancer. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 6, 2 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li M., Xu Y., Peng X., Kim J. S., From low to no O2-dependent hypoxia photodynamic therapy (hPDT): A new perspective. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 3253–3264 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Renno R. Z., Delori F. C., Holzer R. A., Gragoudas E. S., Miller J. W., Photodynamic therapy using Lu-Tex induces apoptosis in vitro, and its effect is potentiated by angiostatin in retinal capillary endothelial cells. Invest. Ophth. Vis. Sci. 41, 3963–3971 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Z., et al. , Photodynamic therapy with motexafin lutetium induces redox-sensitive apoptosis of vascular cells. Arterioscl. Throm. Vas. 21, 759–764 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carneiro B. A., El-Deiry W. S., Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 395–417 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y., et al. , Gasdermin E-mediated target cell pyroptosis by CAR T cells triggers cytokine release syndrome. Sci. Immunol. 5, eaax7969 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou B., Abbott D. W., Gasdermin E permits interleukin-1 beta release in distinct sublytic and pyroptotic phases. Cell Rep. 35, 108998 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or provided in the SI Appendix.