Abstract

mcl-1, a bcl-2 family member, was originally identified as an early gene induced during differentiation of ML-1 myeloid leukemia cells. In the present study, we demonstrate that Mcl-1 is tightly regulated by the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) signaling pathway. Upon deprivation of survival factor from TF-1 myeloid progenitor cells, Mcl-1 levels quickly dropped prior to visible detection of apoptosis of these cells. Upon restimulation of these deprived cells with GM-CSF, the mcl-1 mRNA was immediately induced and its protein product was accordingly resynthesized. Analysis with Ba/F3 cells expressing various truncation mutants of the GM-CSF receptor revealed that the membrane distal region between amino acids 573 and 755 of the receptor β chain was required for mcl-1 induction. Transient-transfection assays with luciferase reporter genes driven by various regions of the mcl-1 promoter demonstrated that the upstream sequence between −197 and −69 is responsible for cytokine activation of the mcl-1 gene. Overexpression of mcl-1 delayed but did not completely prevent apoptosis of cells triggered by cytokine withdrawal. Its down regulation by antisense constructs overcame, at least partially, the survival activity of GM-CSF and induced the apoptosis of TF-1 cells. Taken together, these results suggest that mcl-1 is an immediate-early gene activated by the cytokine receptor signaling pathway and is one component of the GM-CSF viability response.

Cytokines belong to a family of growth factors that play an important role in regulating the viability, differentiation, proliferation, and function of various hematopoietic cells (2). They function by binding to their cognate receptors and triggering a cascade of tyrosine phosphorylation of both various known intracellular signaling proteins and the STAT (signal transducers and activators of transcription) family of transcription factors (references 12 and 28 and references therein). In the absence of these cytokines, the majority of their dependent cells die, at least in culture, by apoptosis (51), which is one form of cellular suicide that occurs widely during animal development, tissue homeostasis, and various disease processes (references 36, 45, 46, and 50 and references therein). Apoptosis is characterized by distinct morphological changes including cellular shrinkage, blebbing of the plasma membrane, nuclear condensation, and endonucleolytic cleavage of the genomic DNA into nucleosome-length fragments (51).

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-3 (IL-3) are two hematopoietic cytokines produced by activated T cells and mast cells that are potent growth factors for multipotential hematopoietic progenitors as well as various other hematopoietic cells (2). These two cytokines, by binding to their receptors (composed of one cytokine-specific α subunit and one common β subunit also shared with the IL-5 receptor), generate both mitogenic and anti-apoptotic signals. By deletion analysis, GM-CSF has been shown to activate multiple sets of signaling events through distinct cytoplasmic domains of the receptor β subunit (39, 40). While the membrane-proximal domain mediates the induction of c-Myc and is important for cells to progress into the S phase, the distal cytoplasmic domain is essential for the activation of the Ras-Raf-mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway (40). The latter pathway is believed to be important for the anti-apoptotic activity of GM-CSF in hematopoietic cells (16). However, the exact signaling molecules involved in this pathway still remain unclear.

Mcl-1, isolated from the differentiating human myeloid leukemia cell line (19), has sequence similarity to Bcl-2 family members (18, 37, 47). Substantial studies have shown that overexpression of some members of this family, such as Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and A1, can inhibit apoptosis induced by various stimuli (3, 8, 24, 32, 43, 44, 48). Other members, such as Bax, Bad, and Bak, can actually accelerate apoptosis in cells deprived of survival factors (4, 7, 15, 33, 53). Mcl-1 belongs to the former category of the Bcl-2 family, since overproduction of this protein can delay apoptosis induced by various inducers such as c-Myc overexpression, growth factor withdrawal, and other cytotoxic agents (38, 58). Like other members of this family, Mcl-1 also contains two highly conserved regions designated the BH1 and BH2 domains, which have been shown to be required for the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-2 and for heterodimerization with Bax (56). Unlike Bcl-2, Mcl-1 contains a PEST sequence (19), which probably presents itself as a labile protein with an estimated half-life of 1 to 3 h (54). Other than being the product of an early gene activated during tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate TPA-induced differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells (54), the physiological function of Mcl-1 is still unknown. In this study, we show that Mcl-1 in GM-CSF-dependent TF-1 human myeloid progenitor cells is rapidly turned over upon depletion of survival factors from these cells, and that it can be immediately reinduced upon the addition of GM-CSF. Induction of Mcl-1 expression requires the membrane-distal region of the receptor β chain. We further provide evidence that down-regulation of endogenous Mcl-1 in TF-1 cells can overcome, at least partially, the survival activity of GM-CSF and induce apoptosis of these cells. The possible role of Mcl-1 in the GM-CSF signaling pathway is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

TF-1 cells (17) and their derivatives were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin G per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 1 ng of GM-CSF per ml. Human GM-CSF (hGM-CSF) was kindly provided by Schering-Plough Ltd. For GM-CSF depletion experiments, TF-1 cells were washed three times in medium without cytokine and seeded in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 0.5% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. During restimulation experiments, only GM-CSF (10 ng/ml) was added back to the cells that had been previously deprived of cytokine and placed in low-serum medium. TF/Bcl-2 and TF/neo are two TF-1 derivatives overexpressing Bcl-2 and Neo control, respectively. They were generated by infection with a recombinant retroviral vector carrying bcl-2 cDNA or the wild-type vector alone (pBabeneo [29]). These were used as a pooled mixture. Mcl10-1 and Mcl10-2 are two TF-1 lines overexpressing human Mcl-1 under the Tet-off system and were generated as specified by the manufacturer (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). TFtD1 is a control TF-1 cell line expressing tetracycline-responsive transcriptional activator (tTA) alone for this inducible system. Murine IL-3 (mIL-3)-dependent pro-B (BaF/3) cells expressing the human GM-CSF receptor α chain alone or in combination with the wild-type or c-terminally truncated receptor β chain were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% conditioned medium from WEHI 3B as a source of IL-3.

DNA fragmentation assay.

One million cells were collected after incubation in the desired medium for 24 h and analyzed as previously described (55). Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of the lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% Sarkosyl, 500 μg of proteinase K per ml) and incubated at 50°C for 3 h. A 10-μl volume of RNase A (2 mg/ml) was added to the lysates, and the tubes were incubated for an additional 1 h. This lysate was mixed well with 1 μl of ethidium bromide (20 μg/ml), extracted once with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform (1:1), and stored at 4°C after the addition of 20 μl of 1% low-melting-point agarose solution containing 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). The samples were melted at 70°C and allowed to solidify inside the well before electrophoresis was initiated.

Immunoblotting.

Cells to be analyzed were lysed in RIPA buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 1% deoxycholate. Cell extracts (50-μg portions) were resolved on an SDS-containing 12% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride nylon membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), and probed with antibodies specific to Bcl-2, Mcl-1, and Bax (all purchased from Santa Crutz Biotechnology, Santa Crutz, Calif.) or α-tubulin (Amersham, Little Chalfont, England). The membrane was then probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit antibody. The specific bands were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence Western blot system (Amersham).

Northern blotting.

Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells by a previously described method (25). A 20-μg portion of total RNA was resolved on a 1% formaldehyde–agarose gel and blotted onto a nitrocellulose filter by the standard procedure. The blot was then probed sequentially with various [α-32P]dCTP-labeled DNA fragments by the random-priming method. After overnight hybridization at 42°C with standard buffer containing 50% formamide, the blot was washed once in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% SDS and twice in 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 55°C and subjected to either autoradiography or direct quantitation with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Determination of the Mcl-1 half-life.

To measure the half-life (t1/2) of Mcl-1 in cells containing GM-CSF, 107 TF-1 cells in the rapidly growing phase were precultured for 30 min in 3 ml of methionine-free medium supplemented with 0.5% dialyzed FBS and 10 ng of GM-CSF per ml to deplete endogenous methionine. Pulse-labeling was initiated by adding 1 mCi of [35S]Met (Amersham; 10 mCi/ml, >1,000Ci/mmol). After 15 min at 37°C, the cells were chased in growth medium containing 0.5% FBS, 10 ng of GM-CSF per ml, and 10 mM methionine. At various times after the chase, the cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and immunoprecipitated with anti-Mcl-1 antibody. The immunoprecipitated complexes were resolved on an SDS-containing 10% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by fluorography. To measure the t1/2 of Mcl-1 in cells containing no GM-CSF, the same procedure was used but the cells were deprived of GM-CSF for 6 h prior to labeling and GM-CSF was omitted during the pulse-labeling and chasing steps. This modified procedure was necessary to ensure that only a minimal amount of GM-CSF was present during the pulse-labeling step to stimulate the synthesis of Mcl-1 and that this residual amount of cytokine could be thoroughly removed at the subsequent chasing step.

[3H]thymidine incorporation assay.

Ba/F3 transfectants were normally maintained in medium with murine IL-3 as described above. One day before the assay, they were seeded at a density of 105/ml in medium containing mIL-3, hGM-CSF, or no cytokine. To determine their mitogenic responses in these cytokines, 104 viable cells from each of these three populations were individually seeded into the 96-well culture plate by using the same medium in which these cells had been previously cultured for 24 h. The mitogenic assay was initiated by the addition of 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Amersham) to each well. After 20 min of pulse-labeling, the cells were lysed and analyzed as previously described (55). All assays were done in triplicate and repeated three times.

Plasmids.

PCDNA-3/bcl-2, PCDNA-3/m-mcl-1, and PCDNA-3/h-mcl-1 are mammalian expression vectors driving bcl-2 and mouse and human mcl-1 cDNA, respectively, under the control of cytomegalovirus promoters. PCDNA-3/bcl-2 was generated by PCR amplification of the coding region of the bcl-2 cDNA (in the BK-KS-H-Bcl-2 plasmid provided by Stanley J. Korsmeyer, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo.) with the following two primers: sense, 5′ GCGAATTCGTTGGCCCCGTTGCTTTT 3′; antisense, 5′ GCGTCGACAGGCATGTTGACTTCACT 3′. The amplified fragments were restricted with EcoRI and SalI and cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of the pCDNA-3 vector (Invitrogen). PCDNA-3/m-mcl-1 was constructed by subcloning the EcoRI-XbaI fragment of the mouse mcl-1 cDNA in pBluescript vector (provided by Stanley J. Korsmeyer) into the corresponding sites of the pCDNA-3 vector. The human mcl-1 cDNA encompassing the entire coding region (∼1.1 kb) was synthesized by reverse transcription-PCR amplification of mRNA isolated from TF-1 cells with the following two primers: sense, 5′ GCGGATCCACCATGTTTGGCCTCAAAAGA 3′; antisense, 5′GCGTCGACAGGCTATCTTATTAGATATGC 3′ (designed according to the published sequences) (19). Briefly, 1 μg of mRNA was reverse transcribed with recombinant Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (GIBCO-BRL) and the antisense primer listed above. The first-strand cDNA was then PCR amplified with these two primers and the Advantage KlenTag polymerase mix (Clontech). The PCR-amplified human mcl-1 cDNA fragment was digested with BamHI and SalI and cloned into the BamHI and XhoI sites of the pCDNA-3 vector. Both PCR-amplified bcl-2 and human mcl-1 cDNAs were confirmed by DNA sequencing to be free from mutations that would change the amino acid sequence of the encoded proteins. pUHD-mcl-1(S) and pUHD-mcl-1(AS) are two tetracycline-regulated expression vectors driving human mcl-1 cDNA in a sense or antisense orientation, respectively. They were generated by inserting the human mcl-1 cDNA in either direction into the EcoRI site of the pUHD10-3 vector (8a).

Cloning of the 5′-flanking region of the murine mcl-1 gene.

A murine ES cell (129/Sv) genomic library (in Lambda FIX II vector) was screened by the standard method (39a) with murine mcl-1 cDNA as a probe. A single positive clone was obtained from a screen of 2 × 105 recombinant phages. Southern blot analysis with distinct parts of the cDNA revealed that a 2.8-kb HindIII-SacI fragment derived from this phage insert (∼14 kb [49b]) contains the 5′ end of the coding sequences. Sequencing of this DNA fragment confirmed that it contains the first 399 bp of the open reading frame of the murine mcl-1 cDNA (GenBank accession no. U35623 and our unpublished data) and 2,434 bp of the 5′-flanking sequences.

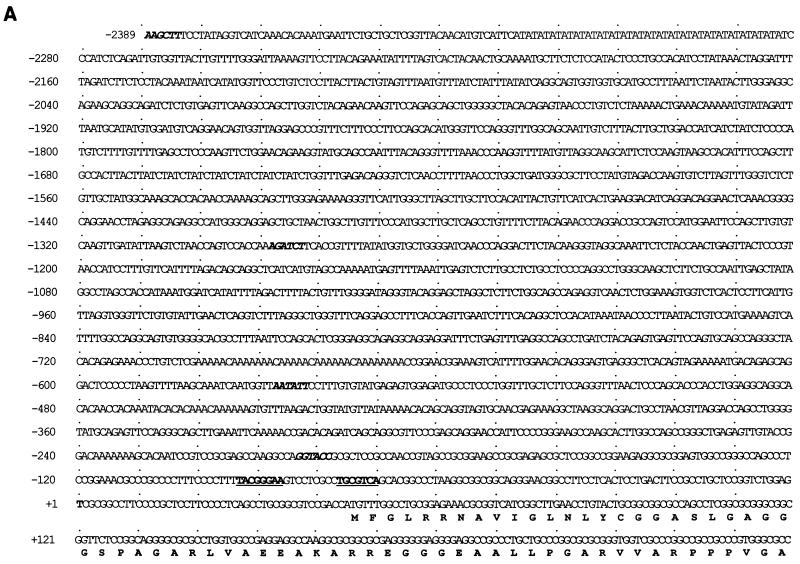

Primer extension analysis of transcriptional start sites.

The 5′ end of the mcl-1 mRNA was determined by the standard method as described previously (39a). Briefly, 40 μg of total RNA (or 2 μg of mRNA) isolated from BaF/3 cells stimulated with mIL-3 for 1 h was hybridized with the 5′-end-labeled ATG-38 primer at 30°C for 12 h before Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase was added to initiate the extension reaction. The resultant DNA fragment was resolved on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. The sequence of the ATG-38 primer is 5′ ATGACCGCGTTTCTCCGCAGGCCAAACATGGTCGGACG 3′.

Reporter plasmids and luciferase assay.

The mcl-1 genomic clone was digested with various restriction enzymes and the resultant DNA fragments were subcloned by standard methods into the multiple-cloning sites of the promoterless vector pGL-2-basic (Promega) to generate the reporter constructs p(−2389/+10)mcl-luc, p(−1288/+10)mcl-luc, p(−564/+10)mcl-luc, p(−203/+10)mcl-luc, p(−87/+10)mcl-luc, and p(−70/+10)mcl-luc. The numbers in parentheses indicate the nucleotide position with respect to the transcriptional initiation site shown in Fig. 5. pB-dl(−197/−69) was constructed by deleting the internal region (−197/−69) from p(−1288/+10)mcl-luc. During the construction of these reporter plasmids, some DNA fragments to be cloned were PCR amplified with appropriate primers and subcloned into pGL-2-basic. All plasmids constructed in this way were confirmed by sequencing to be free of base mutations in the amplified region. To analyze the promoter activity of these reporter genes, BaF3 or αβwt cells were transiently transfected with these plasmids by electroporation with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II RF Module system set at the following conditions: 300 V, 40 kHz, five bursts at 2 ms each, and 100% modulation. Electroporated cells were seeded in growth medium with or without mIL-3 (or hGM-CSF). At 12 h after reseeding, the cells were harvested and assayed for luciferase activity. A cytomegalovirus-driven chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter gene was cotransfected to correct for variations in transfection efficiency.

FIG. 5.

Mapping of the TI site of the murine mcl-1 promoter. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the murine mcl-1 gene promoter region. The numbering of the nucleotides is relative to the TI site at +1. The restriction enzyme sites used for generating luciferase reporter constructs are shown in italics. The SIF- and CRE-2-like sequences (see text) are underlined. (B) Primer extension of RNA isolated from Ba/F3 cells with the ATG-38 primer (see Materials and Methods). Extension products from 2 μg of mRNA or from 40 μg of total RNA are shown in lanes 3 and 4, respectively. Products of a control reaction in which cellular RNA was replaced with 200 μg of yeast tRNA are shown in lane 2. A sequencing reaction product from a reaction performed with the ATG-38 primer was also loaded onto the same denaturing gel to help assign the TI site. The DNA template used for sequencing was the HindIII-SacI genomic fragment as described in Materials and Methods.

Transient transfection and detection of Bcl-2 or Mcl-1 expression by flow cytometry.

Teo4, another line of TF-1 derivatives expressing tTA for the Tet-off inducible system, was transiently transfected with TRE (Tet-responsive element) vectors driving the bcl-2 or mcl-1 cDNA in a sense or antisense orientation by using a liposome-mediated gene transfer method. Briefly, DNA to be transfected (2 μg of the DNA construct of interest plus one-sixth the molar amount of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression vector) was gently mixed with 2.5 μl of DMRIE-C (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) to form the DNA-lipid complex. After 30 min, the preformed complexes were added to 106 cells which had been washed once with serum-free medium. Following a 4-h incubation in serum-free medium containing 2 ng of GM-CSF per ml, transfected cells were divided into two parts and each part was replaced with fresh growth medium containing or not containing tetracycline (2 μg/ml). At 20 to 42 h after transfection, the cells were analyzed for the expression of GFP and Mcl-1 (or Bcl-2) by flow cytometry. For this experiment, transfected cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. After a brief wash with PBS, fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% saponin for 15 min, washed once with PBS, and allowed to interact with rabbit antiserum specific to Bcl-2 or Mcl-1 (Santa Cruz). After a 1-h incubation with primary antibody, the cells were washed three times with PBS plus 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and further incubated with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Vector Laboratories) for a further 1 h. After three more washes in PBST, the cells were incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) for 30 min, washed three times with PBST, and analyzed by flow cytometry with a Becton Dickinson FACScan as specified by the manufacturer. For detection of cells expressing GFP, cells were analyzed with the FL-1 channel (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 530/30 nm). For Bcl-2 or Mcl-1 expression, cells were analyzed with the FL-2 channel (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 585/42 nm). All incubation steps were carried out at room temperature, and all antibodies were used at the dilutions recommended by the manufacturer.

Apoptosis detection by annexin-V staining.

Cells transiently transfected with constructs of interest plus expression vectors encoding GFP or a chimeric protein, CD16/CD7 (see below), were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min. After being rinsed with binding buffer (10 mM HEPES/NaOH [pH 7.4], 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2), fixed cells were incubated in the same buffer containing biotin-conjugated annexin-V (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) for another 20 min at room temperature. After several washes, the annexin-V-bound cells were revealed by binding to Texas red (Vector, Burlingame, Calif.)- or phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Zeiss) or flow cytometry, respectively. In experiments in which CD16/CD7 was used as a cotransfection marker, a monoclonal antibody recognizing the extracellular domain of CD16 (MCA1193; Serotec) was included in the staining procedure. Cells cotransfected with this surface marker were further stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above. The expression vector encoding CD16/CD7 fusion protein (the extracellular domain of the cell surface marker CD16 fused to the transmembrane domain of CD7) was derived from pEFCD16/7/Syk (27) by inserting a stop codon into the MluI site immediately downstream of the CD7 coding region. For measurement of apoptosis of nontransfected cells, the same staining procedure was used except that the fixing step was omitted and the annexin-V bound cells were quantified with CytoFluor 2350 fluorescence measurement system (Millipore).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper will appear in the GenBank database under accession no. AF063886.

RESULTS

GM-CSF stimulates Mcl-1 expression at both the protein and mRNA levels.

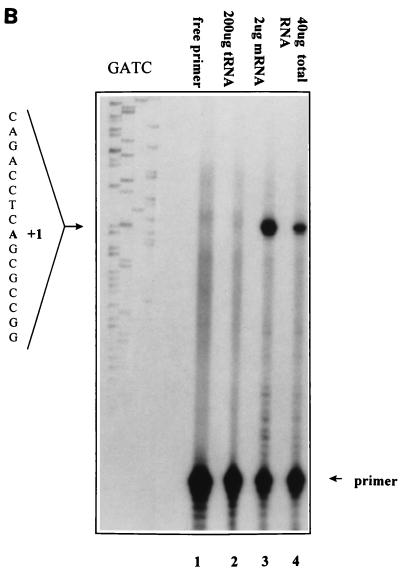

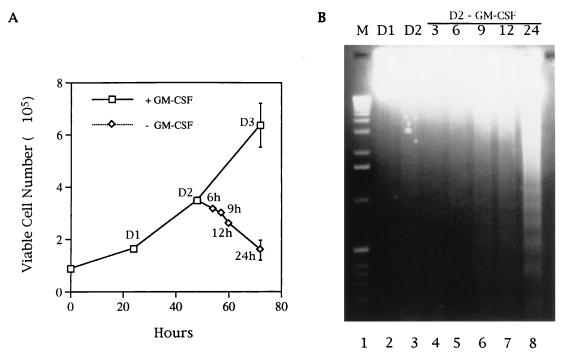

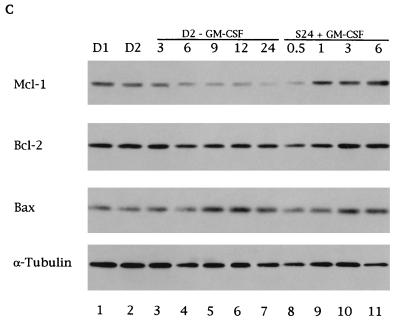

Both serum and GM-CSF are required for the long-term growth of the human myeloid progenitor cell line TF-1. Upon depletion of GM-CSF from the normal growth medium, the viability of TF-1 decreased with time and cells underwent apoptosis (55). However, if the cells were deprived of GM-CSF and subsequently placed in medium containing a low concentration of serum (0.5%), their death rate was greatly increased and more consistent from experiment to experiment when different batches of serum were used (data not shown). This was probably because serum also provided some survival activity to TF-1 cells and this survival activity varied among different batches of serum. For the sake of consistency, in all cytokine depletion and restimulation experiments carried out in this study, the cells were placed in medium with 0.5% serum. Under the conditions used in a standard depletion assay (Fig. 1A), the DNA ladder was not prominent until approximately 40% of the cells had lost their viability (∼20 to 24 h after cytokine depletion) and had undergone apoptosis (Fig. 1B). To investigate the role of Bcl-2 family proteins in this type of apoptosis, the expression patterns of this protein family at various times after factor removal were examined. In six independent experiments, we consistently observed that the level of Mcl-1 decreased rapidly and significantly following withdrawal of the survival factor from the culture medium (Fig. 1C). Upon readdition of GM-CSF to the growth factor-starved cells, the level of Mcl-1 protein was immediately increased (Fig. 1C, lanes 9 to 11). In contrast, even after a 24-h depletion of growth factors, the levels of other Bcl-2 family members such as Bcl-2, Bax (Fig. 1C), and Bcl-xL (data not shown) were not significantly affected (a less-than-twofold change). Furthermore, none of these three members could be immediately reinduced by GM-CSF as in the case of Mcl-1 (lanes 9 to 11 and data not shown). Of interest, A1, another member of this protein family previously shown to be induced by GM-CSF (23c), was hardly detectable in these cells (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Mcl-1 levels correlate with the survival of TF-1 cells. (A) Growth and death curves of TF-1 cells. TF-1 cells were seeded at a density of 105/ml in regular growth medium containing GM-CSF. At various times after seeding, the viable-cell number was determined by trypan blue exclusion. At 48 h after seeding, some cells were washed to remove GM-CSF and replated into low-serum (0.5%) medium without GM-CSF. The viable-cell number in this group was determined at various times after replating. (B and C) Cytokine depletion induces apoptosis in TF-1 cells. Half of the cells depleted of cytokine as described for panel A were harvested after counting, and their genomic DNA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The other half of the cells were harvested, and equal amounts (50 μg) of their protein lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for the expression of Mcl-1 and other proteins as indicated in the figure (C, lanes 1 to 7). Cells deprived of GM-CSF, placed in low-serum medium for 24 h, and restimulated with GM-CSF for 0.5, 1, 3, and 6 h were also prepared and analyzed (lanes 8 to 11). The data shown here are representative results from one of three independent experiments with very similar patterns. The standard deviation of the viable-cell number (A) is indicated by error bars. D1, D2, and D3 indicate cells at 24, 48 or 72 h, respectively, after the initial seeding in regular growth medium containing GM-CSF.

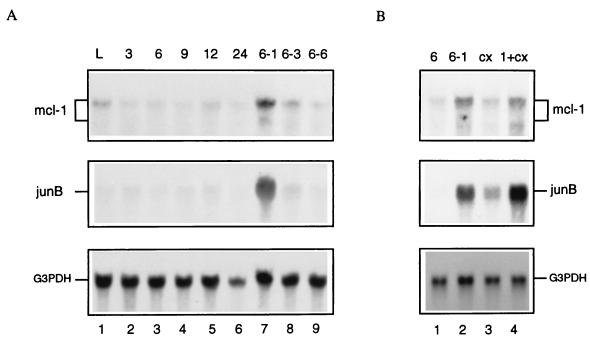

To examine if the rapid change of Mcl-1 protein levels as a result of the absence or presence of the survival factor was due to changes in the expression of its mRNA, total RNA isolated from cells during the actively growing phase, cells that had been depleted of survival factors for various times, or factor-deprived cells that had been restimulated by GM-CSF were analyzed by Northern blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 2A, the 3.9-kb transcript of mcl-1 mRNA quickly dropped to the baseline level within 3 to 6 h after growth factor removal (the 2.5-kb transcript is too weak to be detectable in this figure). However, upon restimulation of factor-deprived cells (depleted for 6 h) with GM-CSF only, the mcl-1 mRNA was rapidly induced. Its induction was transient and peaked at 1 h (ca. three- to fourfold induction for the 3.9-kb transcript [Fig. 2A, lane 7]) posttreatment. The mcl-1 mRNA was still induced by GM-CSF in the presence of cycloheximide, suggesting that de novo protein synthesis was not required for this process (Fig. 2B, lane 4). This induction pattern was similar to that of junB (Fig. 2), an immediate-early gene activated by various growth factors (9, 14, 23). These results indicated that mcl-1 is an immediate-early gene activated by the GM-CSF signaling pathway.

FIG. 2.

GM-CSF treatment increases mcl-1 mRNA levels. TF-1 cells treated under various conditions as described below were lysed, and their total RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blotting with an mcl-1-specific probe. The same blot was also stripped and sequentially reprobed with probes specific to junB and the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (G3PDH), respectively. (A) Lanes: 1, cells in logarithmic phase (L); 2 to 6, cells depleted of GM-CSF and serum for 3 to 24 h; 7 to 9, cells depleted of GM-CSF and serum for 6 h and restimulated with GM-CSF for 1, 3, and 6 h, respectively. (B) Lanes: 1 and 2, same treatment as described for lanes 3 and 7 of panel A, respectively; 3, cells depleted of GM-CSF and serum for 6 h and stimulated with 10 μg of cycloheximide (cx) per ml for 1 h; 4, same treatment as for lane 3 but stimulated with GM-CSF and cycloheximide (1+cx) for 1 h.

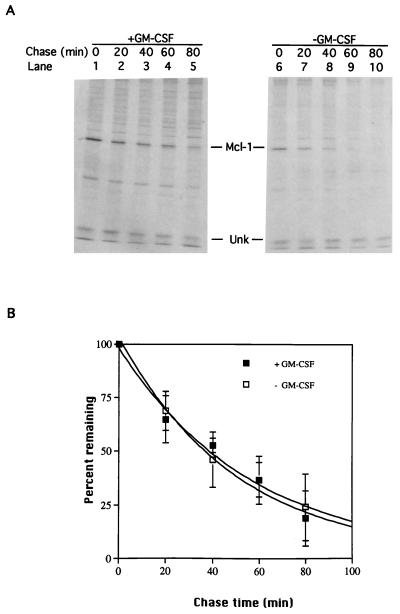

Mcl-1 was reported to be a labile protein probably due to the presence of PEST sequences (54). We were curious to know if depletion of GM-CSF would further facilitate the degradation of Mcl-1. To examine this, the half-life of Mcl-1 in cells fed or not fed with GM-CSF was determined. In five independent experiments, we consistently observed that the half-life of Mcl-1 in cells with GM-CSF was around 30 to 40 min (Fig. 3), which was similar to the previously reported half-life of ∼1 h for the upper band of Mcl-1 proteins (54). (In the system we used, we were unable to detect the lower band, which was reported to have a longer half-life of ∼3 h.) The half-life of Mcl-1 in cells depleted of GM-CSF was very similar to that of cells in the presence of GM-CSF (also ∼30 to 40 min [Fig. 3]), suggesting that the Mcl-1 protein levels affected by the GM-CSF signaling pathway were regulated mainly at the synthesis, not the degradation, step.

FIG. 3.

Mcl-1 half-lives in cells cultured with or without GM-CSF. TF-1 cells pulse-labeled with [35S]Met for 15 min and chased with excess amounts of cold methionine were thoroughly washed and reseeded in medium containing or not containing GM-CSF. (A) At various times after reseeding, total-cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with antibody specific to Mcl-1, and the immunoprecipitated complexes were resolved on an SDS-containing 10% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by fluorography. The Mcl-1-specific bands were quantified with a PhosphorImager. (B) After normalization to the amount of an unknown (Unk) protein whose levels remain constant during experimental period, the level of Mcl-1 at each time point was converted to the percentage of Mcl-1 level at the time zero point and plotted to determine the half-lives.

Induction of mcl-1 requires the membrane-distal domain of the receptor β subunit.

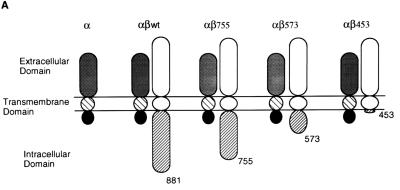

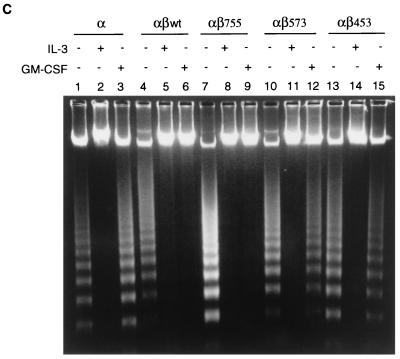

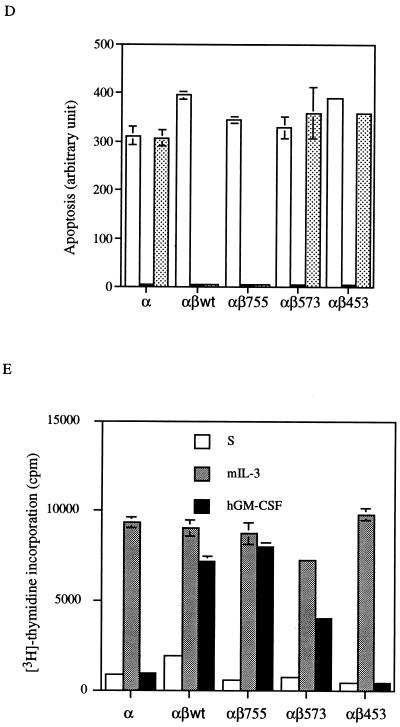

The β chain of the GM-CSF receptor plays the major role in transducing many signals generated by the activated receptor. We were interested in determining which domain of the β chain was important for the induction of mcl-1 by GM-CSF. To address this issue, mIL-3-dependent Ba/F3 cells were engineered to express the hGM-CSF receptor α chain alone or in combination with various C-terminal truncation mutants of the receptor β chain (Fig. 4A). This heterologous system proved to be useful to study the hGM-CSF receptor signaling pathway, because the introduction of the wild-type hGM-CSF receptor into Ba/F3 cells resulted in rapid growth of these cells in medium containing hGM-CSF but in only their usual general growth properties in medium containing mIL-3 or without any cytokine (40). As shown in Fig. 4B, while bcl-2 mRNA levels in all Ba/F transfectants were very low and were not significantly affected by mIL-3 or hGM-CSF (Fig. 4B), the regulation of mcl-1 mRNA in these cells by mIL-3 or hGM-CSF was quite discernible. mcl-1 mRNA was induced in all Ba/F3 derivatives cultivated in medium containing mIL-3, which supports the long-term growth of these cells. However, when these cells were cultivated in medium containing hGM-CSF, they had differential responses. Only αβwt (expressing wild-type hGM-CSF receptor α and β chains) and αβ755 (expressing α chain and β chain C-terminally deleted to amino acid [aa] 756) cells retained the ability to induce mcl-1 upon stimulation with hGM-CSF. The mcl-1 induction by hGM-CSF was abolished in cells expressing an α chain alone (Ba/Fα) or expressing α chain in combination with a β-chain mutant C-terminally deleted up to either aa 574 (αβ573) or aa 454 (αβ453). This result suggests that mcl-1 induction by hGM-CSF requires the membrane-distal region of the β chain between aa 573 and 755, a domain that is also important for the induction of other immediate-early genes such as jun, fos and myc (Fig. 4B). Of note, deletion of this region resulted in differential effects on the anti-apoptotic and mitogenic activities of the receptor. As shown in Fig. 4C and D, in medium containing hGM-CSF, αβ573 cells underwent apoptosis even though they still retained partial mitogenic activity (∼40 to 50% of the activity of the same cells in mIL-3) (Fig. 4E). To be able to quantitatively compare the apoptotic response of αβ573 cells in medium containing mIL-3 or hGM-CSF or without any factor, equal numbers of cells (2 × 106 in 10 ml) were seeded in various culture media. At 24 h after seeding, the numbers of viable and apoptotic cells were determined by trypan blue and annexin-V binding assays, respectively. Under these conditions, we always observed that cells seeded in mIL-3 could reach a density of (7.4 ± 0.2) × 105/ml whereas cells in hGM-CSF or without any factor reached only (2.0 ± 0.2) × 105 and (1.0 ± 0.1 × 105) per ml, respectively. Although cells seeded under the last two conditions had different amounts of viable cell numbers at the 24-h time point, they had similar numbers of apoptotic cells as reflected by the fluorescent units of annexin-V-bound cells (Fig. 4D) or by determination of the trypan blue-positive populations (∼2.5 × 105 per ml for both). This result suggests that deletion of the β chain between aa 573 and 755 resulted in complete loss of the anti-apoptotic activity while retaining partial mitogenic activity of the activated receptor.

FIG. 4.

Mcl-1 induction requires the membrane-distal domain of the GM-CSF receptor β chain. (A) Schematic representation of human GM-CSF receptor mutants transfected into Ba/F3 cells. (B) Ba/F3 cells expressing various receptor mutants were depleted of cytokine for 20 h before they were stimulated with mIL-3 or hGM-CSF. At various times after stimulation (0.5 to 3 h), the cells were lysed and their total RNA was analyzed by Northern blotting with specific probes as indicated in the figure. (C) Equal numbers (2 × 106) of Ba/F3 cells expressing various GM-CSF receptor mutants were seeded for 24 h in 10 ml of medium containing no cytokine, mIL-3, or hGM-CSF, and then their genomic DNA was extracted and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (2% agarose). (D) Cells treated as in panel C were stained with biotinylated annexin-V and Texas red-conjugated streptavidin as described in Materials and Methods. The positively stained (apoptotic) cells were quantified with Cytofluor 2350. The fluorescence units of the annexin-V-bound cells are plotted here to reflect the absolute numbers of apoptotic cells. □, S; , mIL-3; , hGM-CSF. (E) Mitogenic activity of Ba/F3 cells expressing various receptor mutants. Cells (104) cultured in medium containing no cytokine (S), mIL-3 or hGM-CSF were pulse-labeled with [3H]thymidine for 20 min and lysed, and the incorporated counts were measured with a β-counter.

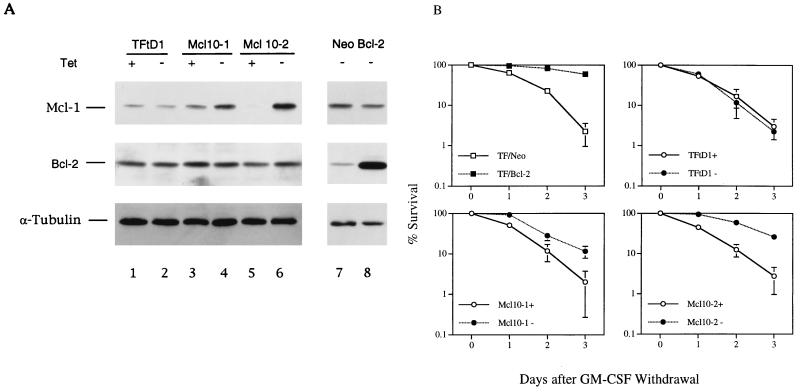

Cytokine activates the mcl-1 gene promoter.

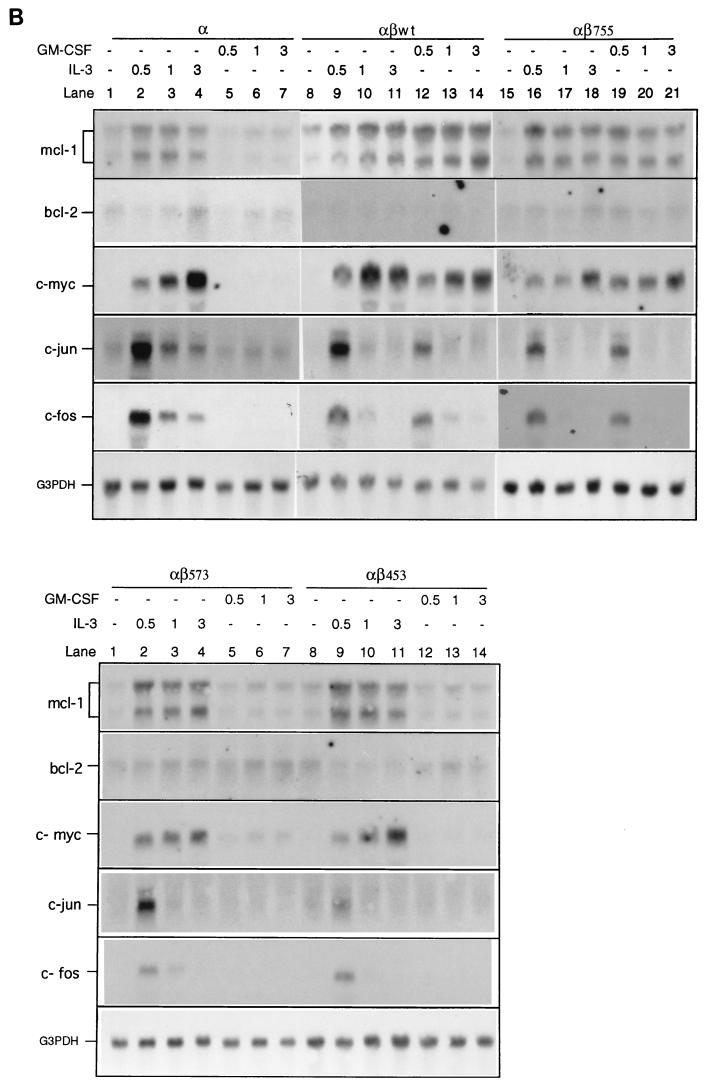

To examine if the induction of mcl-1 mRNA by GM-CSF or IL-3 (Fig. 4B) was regulated at the transcriptional level, the 5′-flanking region of the murine mcl-1 gene was isolated (see Materials and Methods) and sequenced (Fig. 5A). Primer extension (Fig. 5B) and S1-mapping (data not shown) analyses revealed that the transcriptional initiation site (TI) of this gene was located 45 nucleotides upstream of the first ATG of the open reading frame deduced from the murine mcl-1 cDNA. To examine if the cloned 5′-flanking DNA fragment immediately upstream of the TI site conferred any promoter activity, a luciferase reporter gene containing sequences between −2389 and +10, p(−2389/+10)mcl-luc, was analyzed. This reporter, when transfected into BaF/3 cells, manifested some promoter activity compared to the promoterless parental vector, pGL2-basic (Fig. 6B and C). Addition of IL-3 further increased the promoter activity by ∼threefold, which was similar to the fold increase at the mRNA level as a result of GM-CSF (Fig. 2) or IL-3 (Fig. 4B) addition. To map the promoter region that was responsible for cytokine inducibility, a series of reporters harboring various regions of the promoter DNA were analyzed (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B and C, IL-3 inducibility requires the presence of the DNA region between −197 and −69. An identical promoter region was mapped for the GM-CSF inducibility when these deletion mutants were analyzed in αβwt cells (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that cytokine induction of mcl-1 mRNA is regulated mainly at the transcriptional level.

FIG. 6.

Cytokine activates the mcl-1 gene promoter. (A) Schematic representation of luciferase reporter genes driven by various regions of the mcl-1 promoter. (B) BaF/3 cells transfected with various luciferase reporters as indicated were stimulated with IL-3 or not stimulated, and the lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity (in arbitrary units). Very similar results were obtained from four independent experiments, and the data shown here are from one representative assay. (C) The average fold induction (mean ± standard deviation, n = 4) by IL-3 for each construct analyzed in panel B. The luciferase activity generated from the expression of pUHC13-3 (a luciferase reporter driven by the minimal CMV promoter) was not affected by IL-3 and is included as a negative control.

Mcl-1 plays a role in the survival activity of the activated GM-CSF receptor.

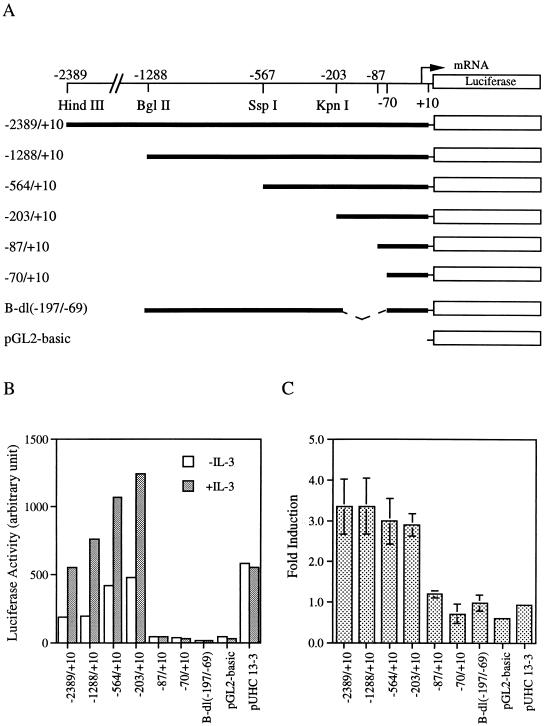

As shown above, mcl-1 mRNA was induced only in cells that could survive under that culture condition (i.e., all cells in the presence of mIL-3 and αβwt and αβ755 cells in the presence of hGM-CSF). This result suggested that Mcl-1 may play a role in the anti-apoptotic activity of the GM-CSF and IL-3 signaling pathway. To examine this possibility, the following experiments were performed. First, we examined if ectopic overexpression of Mcl-1 would prevent TF-1 cells from undergoing apoptosis upon depletion of their dependent cytokines. For this experiment, TF-1 cells conditionally overexpressing Mcl-1 were generated by using the Tet-off inducible system. Two independent clones (Mcl10-1 and Mcl10-2) were isolated, and their Mcl-1 levels in the presence or absence of tetracycline were analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig. 7A). Upon removal of tetracycline (Fig. 7A, lanes 4 and 6), Mcl-1 was induced approximately 2.5-fold in Mcl10-1 and 20-fold in Mcl10-2. When deprived of GM-CSF, these cells still died but at a rate significantly lower than under conditions where Mcl-1 was not overproduced (i.e., cultivated in the presence of tetracycline) (Fig. 7B). As more Mcl-1 was induced, more protection was observed. Although the Bcl-2 protein or mRNA levels did not fluctuate significantly with the GM-CSF and IL-3 signaling pathway, its ectopic overexpression still delayed factor withdrawal-induced apoptosis in TF-1 cells (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Overexpression of Mcl-1 delays GM-CSF withdrawal-induced apoptosis. (A) TF-1 cells stably overexpressing Mcl-1 under a Tet-off system were established. The Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 levels in these cells grown in medium with or without tetracycline were analyzed by immunoblotting. TFtD1, control TF-1 cells expressing tTA only. Mcl10-1 and Mcl10-2, two single clones derived from TFtD1 that overexpressed Mcl-1 in medium without tetracycline. A pool of TF-1 cells constitutively overexpressing Bcl-2 (lane 8) or control vector (Neo, lane 7) was also analyzed. (B) Death curves of TF-1 derivatives cultured in medium with or without tetracycline (+ and −, respectively). Cells grown to a density of 3 × 105/ml were washed to remove GM-CSF, and the viable-cell numbers were determined by trypan blue exclusion. The percent survival relative to those seeded is plotted against days after GM-CSF removal. Cells constitutively overexpressing Bcl-2 (TF/Bcl-2) or control vector (TF/Neo) were also analyzed.

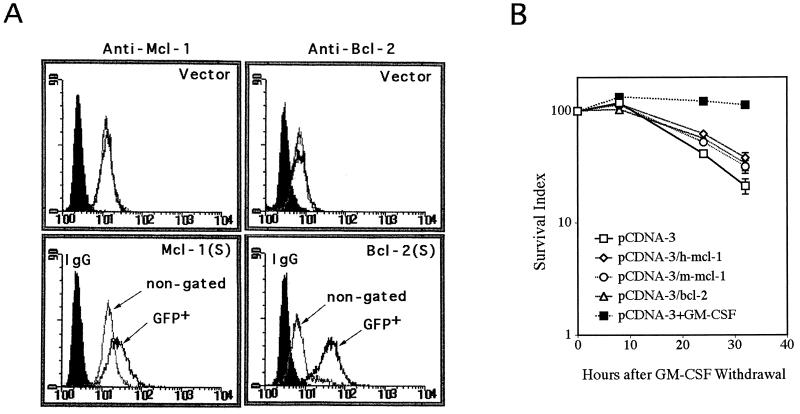

Next, we determined if a delay of apoptosis could also be observed in a transient-transfection assay. To examine this, TF-1 cells were transiently transfected with mcl-1 or bcl-2 expression vector along with one-sixth the molar amount of a GFP-expressing construct. Although GFP-positive cells disappeared slowly over time in the transient-transfection assay, removal of GM-CSF after transfection significantly accelerated this process (Fig. 8B). This was presumably due to an increased rate of apoptosis of all cells tested under this cytokine-free condition, and the GFP fluorescence tended to be lost in the apoptotic cells. To test the effect of Mcl-1 or Bcl-2 on cell death rate measured by this transient-transfection method, we examined specifically how fast the cells transiently expressing either of these two proteins (identified by their coexpression of GFP) would disappear following GM-CSF withdrawal. As illustrated in Fig. 8A, the bcl-2 or mcl-1 cDNA-transfected cells (GFP positive) indeed tended to express larger amounts of Bcl-2 or Mcl-1 proteins than did nontransfected cells as measured by flow cytometry. Under the same conditions, the empty control vector did not have any effect on the expression of these two proteins. In three independent experiments, we consistently observed that cells transiently overexpressing Mcl-1 or Bcl-2 had a delayed rate of disappearance of GFP-positive cells (and therefore a delayed rate of apoptosis) after transfected cells were stripped of GM-CSF (Fig. 8B). We noticed, however, that the protection effect of Mcl-1 (10 to 20%) in this transient-transfection experiment (Fig. 8) was not as efficient as that in the stable-cell-line assay (Fig. 7), even though the former assay usually yields higher levels of protein expression than the latter one. The exact mechanism is unknown but could be due to differences in the time point (24 to 30 h versus 2 to 3 days), the assay method (GFP versus trypan blue), and/or the amounts (a fraction versus all cells overexpressing Mcl-1) used in these two different systems.

FIG. 8.

TF-1 cells transiently overexpressing Mcl-1 or Bcl-2 delayed the disappearance of transfected cells (GFP marked) following removal of GM-CSF. (A) Cells were transiently transfected with pCDNA-3/h-mcl-1, pCDNA-3/m-mcl-1, pCDNA-3/bcl-2, or a control plasmid along with one-sixth the molar amount of GFP vectors. At 15 h after transfection, some cells were analyzed for their expression of Mcl-1 or Bcl-2 by flow cytometry; others were depleted of GM-CSF. The solid peaks indicate cells stained with control rabbit IgG, and the open peaks indicate cells stained with Mcl-1 (upper and lower left panels) or Bcl-2 antibody (upper and lower right panels). The open peaks in gray lines indicated total transfected cells (nongated), and black lines show the GFP positive populations. The transfection efficiency was 1 to 3%. (B) At various times after GM-CSF removal, the number of GFP positive cells in each transfectant was analyzed by flow cytometry and plotted against hours relapsed. Cells transfected with the control vector but placed in medium with GM-CSF (pCDNA-3+GM-CSF) were included as a control. The GFP numbers at time zero were taken as 100%, and the numbers at subsequent time points were plotted as the percentage relative to the initial numbers. This relative percentage was designated the survival index. Data shown here are means of three independent experiments.

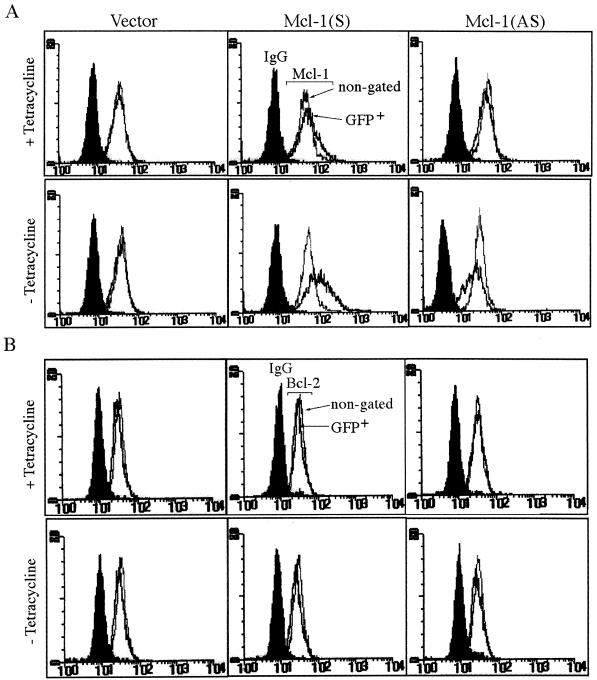

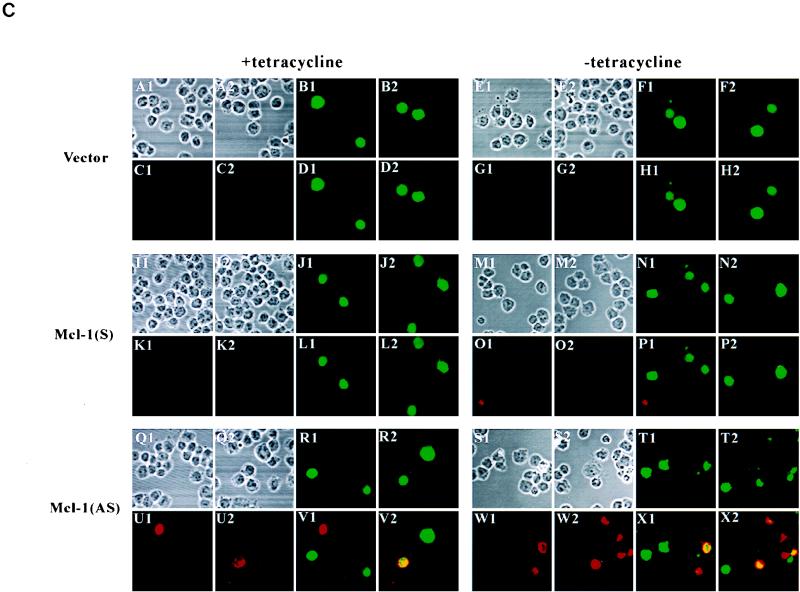

To further demonstrate that Mcl-1 indeed played a role in the anti-apoptotic activity of the GM-CSF signaling pathway, experiments were designed to reduce the endogenous amount of Mcl-1 and to examine its effect on the survival of affected cells. Our initial attempt was to establish a Tet-off inducible line in which the antisense mcl-1 cDNA could be induced in the absence of tetracycline. However, after several rounds of stable-cell-line selection, none of the clones that survived drug selection expressed antisense mcl-1 (data not shown). This was probably due to some leaky expression of the cytotoxic antisense mcl-1 in the presence of tetracycline (see below). We then performed transient-transfection assays (Fig. 9) to investigate this issue. In this experiment, the TeO4 cells (another TF-1 derivative stably overexpressing tTA for the Tet-regulated system) were transfected with a Tet-operator-controlled expression vector driving mcl-1 cDNA in a sense or antisense orientation. To mark the transfected cells, a vector driving the expression of GFP (at one-sixth the molar amount) was again cotransfected. After transfection, half of the cells were cultured in complete medium (containing GM-CSF) with tetracycline and half were cultured in the same medium without tetracycline. The Mcl-1 protein levels and the number of GFP-positive cells in each case were measured by flow cytometry 20 or 42 h after transfection, respectively. (Examination of the protein level at the early time point [20 h] was necessary, because cells transfected with the antisense vector tended to die and lose GFP fluorescence at later time points [see below].) As illustrated in Fig. 9A, in the presence of tetracycline the endogenous Mcl-1 levels were slightly (10 to 15%) affected by the transfected DNA, a result probably due to some leaky expression of these constructs. However, in its absence, the endogenous Mcl-1 levels were significantly affected. The sense construct tended to express more Mcl-1 protein (44% ± 3% of GFP-positive cells expressed more proteins than did the nongated controls), whereas the antisense vector tended to decrease the endogenous protein level (31% ± 3% of GFP-positive cells expressed less protein than did the nongated controls). None of these conditions affected the expression of the endogenous Bcl-2 proteins (Fig. 9B).

FIG. 9.

The Mcl-1 antisense construct induces apoptosis of TF-1 cells. (A and B) Flow cytometric analysis of Mcl-1 (A) or Bcl-2 (B) levels in cells transfected with various vectors. TeO4 cells transiently transfected with control vector, pUHD-mcl-1(S), or pUHD-mcl-1(AS) along with the GFP expression vector as described in Materials and Methods were treated with tetracycline for 20 h or not treated. At this point, some cells were fixed and analyzed for Mcl-1 or Bcl-2 expression by flow cytometry. For each transfection experiment, a total of 5,000 cells (gated for GFP+ or nongated) were analyzed. (C) The Mcl-1 antisense construct tended to overcome the survival activity of GM-CSF and induce apoptosis of TF-1 cells. As described for panel A, cells that remained GFP positive at the 42-h time point were stained with annexin-V and assessed for their apoptotic status. Annexin-V-positive (biotin-labeled) cells were recognized by Texas red-conjugated streptavidin and visualized by confocal microscopy. For all conditions, two different views are shown (views 1 and 2). For each panel, the upper left two images (A1, A2, E1, E2, I1, I2, M1, M2, Q1, Q2, S1, and S2) are transfected cells viewed under phase contrast; the upper right two views are the corresponding field that showed the GFP-positive cells (B1, B2, F1, F2, J1, J2, N1, N2, R1, R2, T1, and T2); the lower left two views (C1, C2, G1, G2, K1, K2, O1, O2, U1, U2, W1, and W2) are the same field that showed the annexin-V-positive cells (red); and the lower right two views (D1, D2, H1, H2, L1, L2, P1, P2, V1, V2, X1, and X2) are the superimposed results of the two fluorescent images. Yellow images are cells that were doubly positive for GFP and annexin-V. Magnification, ×308.

In three independent experiments (Table 1), we consistently observed that cells transfected with control vector and cultured in medium without tetracycline tended to retain slightly more GFP-positive cells than did the same transfected cells cultured in medium containing tetracycline (average increase of 5.1% ± 2.0%). If the cells were transfected with Mcl-1 sense vector, the number of GFP-positive cells in medium without tetracycline was further increased (average increase of 10.2% ± 1.3%). In contrast, when cells were transfected with Mcl-1 antisense vector, a significant loss of GFP-positive cells was observed upon removal of tetracycline (average decrease of 20.6% ± 2.8%). Based on the observation that GFP-positive cells gradually lost GFP fluorescence upon GM-CSF withdrawal (Fig. 8B), this lost fraction (from GFP-positive to GFP-negative cells) specifically seen in cells transfected with the antisense vector most probably represented those cells whose Mcl-1 protein levels were effectively reduced and had undergone apoptosis to the point at which the GFP fluorescence was lost (some of these cells, annexin-V positive but GFP negative, are shown in Fig. 9C, X2). On the other hand, under the same conditions, the transfected populations that remained identifiable by their GFP fluorescence tended to have more apoptotic cells than did those from cells transfected with control or sense vectors, as revealed by annexin-V staining and viewed under a confocal microscope (Fig. 9C, X1 and X2). This double-positive (GFP-positive and annexin-V-positive) population increased (∼12% [see Table 2]) in cells transfected with the antisense vector under induced conditions (lacking tetracycline) probably represented transfected cells that were dying but at the early stage of apoptosis when GFP fluorescence remained detectable. To quantify the percentage of these double-positive populations, an identical experiment to that described in Fig. 9 but replacing GFP DNA with an expression vector driving the synthesis of a chimeric protein expressed on the cell surface (CD16/CD7 [see Materials and Methods]) was carried out. Cotransfection with GFP or CD16/CD7 gave very similar results in terms of loss of transfected markers upon apoptosis (data not shown). However, CD16/CD7, after being stained with primary and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies, gave a much better signal than GFP did in the FL-1 channel of the flow cytometer. Table 2 shows that transfection with the vector control generated a background level (∼12%) of apoptotic cells (double positive for annexin-V and CD16) irrespective of the presence or absence of tetracycline in the culture medium, a result probably due to the toxicity of DMRIE-C used in the assay. A similar case was also observed in experiments with the mcl-1 sense vector. In contrast, introduction of the antisense vector under induced conditions (without tetracycline) significantly increased the percentage of this double-positive population that was at the early stage of apoptosis (average increase of 11.9% ± 6.1%). Taken together, these results and those in Fig. 9 and Table 1 clearly indicate that down-regulation of Mcl-1 by antisense constructs at least partially overcame the survival activity of GM-CSF and induced apoptosis of dependent cells.

TABLE 1.

Number of cells expressing GFP after cotransfection with various constructs

| Construct | Tetracycline addition | Expt 1

|

Expt

2

|

Expt 3

|

Average gain or loss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of GFP-positive cellsa | % Gain or lossb | No. of GFP-positive cells | % Gain or loss | No. of GFP-positive cells | % Gain or loss | |||

| Vector | + | 1,893 | 2,127 | 1,974 | ||||

| − | 1,942 | +2.6 | 2,237 | +5.2 | 2,123 | +7.5 | +5.1 ± 2.0 | |

| Mcl-1(S) | + | 2,925 | 2,941 | 3,690 | ||||

| − | 3,183 | +8.8 | 3,239 | +10.0 | 4,128 | +11.9 | +10.2 ± 1.3 | |

| Mcl-1(AS) | + | 1,633 | 1,770 | 1,917 | ||||

| − | 1,315 | −19.5 | 1,338 | −24.4 | 1,573 | −17.9 | −20.6 ± 2.8 | |

Number of cells expressing GFP detected by flow cytometry from 105 transfected cells.

[100 × (Number of GFP-positive cells in medium without tetracycline) − (number of GFP-positive cells in medium with tetracycline)]/(number of GFP-positive cells in medium with tetracycline).

TABLE 2.

Percentage of apoptotic cells after cotransfection with CD16/CD7 and various constructs

| Construct | Tetracycline addition | Expt

1

|

Expt 2

|

Expt 3

|

Average % differencec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of double-positive cellsa | % Differenceb | % of double-positive cells | % Difference | % of double-positive cells | % Difference | |||

| Vector | + | 13.5 | 12.6 | 12.6 | ||||

| − | 10.9 | −2.6 | 12.7 | +0.1 | 14.1 | +1.5 | −0.3 ± 1.7 | |

| Mcl-1(S) | + | 6.6 | 13.0 | 11.0 | ||||

| − | 7.9 | +1.3 | 11.8 | −1.2 | 10.5 | −0.5 | −0.1 ± 1.1 | |

| Mcl-1(AS) | + | 11.0 | 16.9 | 16.2 | ||||

| − | 21.7 | +10.7 | 36.8 | +19.9 | 21.0 | +5.2 | +11.9 ± 6.1 | |

After transfection, cells were stained with annexin-V and antibody to CD16 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Between 500 and 1,000 of CD16-positive cells from each condition were analyzed for their reactivity to annexin-V.

The percentage of double-positive cells cultured without tetracycline minus the percentage of double-positive cells cultured with tetracycline.

Average percent difference from the three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

mcl-1 was originally identified as an early gene induced during differentiation of ML-1 myeloid leukemia cells (19). Although overexpression of the Mcl-1 protein can protect against apoptosis triggered by various death inducers (38, 58), its physiological function is still unclear. In this report, we show that mcl-1 is an immediate-early gene activated by the GM-CSF signaling pathway. Furthermore, unlike other members of the Bcl-2 family protein, the Mcl-1 protein level was tightly regulated by this survival cytokine in TF-1 myeloid progenitor cells. Ectopic overexpression of Mcl-1 delayed the apoptosis of TF-1 cells triggered by GM-CSF withdrawal, whereas antisense blocking of endogenous Mcl-1 overcame, at least partially, the protective effect of GM-CSF and promoted the apoptosis of TF-1 cells. These results strongly suggest that Mcl-1 plays a role in the survival function of the GM-CSF signaling pathway.

Several lines of evidence suggest that Mcl-1, Bcl-2, and possibly other members of this protein family together mediate the anti-apoptotic function of IL-3 and GM-CSF. (i) Overexpression of Bcl-2 or Mcl-1 alone in the cell system used here delayed but did not completely prevent GM-CSF withdrawal-induced apoptosis. (ii) Zha et al. (57) reported that an IL-3-activated signal led to phosphorylation of Bad, which was then sequestered in the cytosol bound to 14-3-3. The serine-phosphorylated Bad failed to bind to Bcl-xL and therefore could not promote cell death. (iii) GM-CSF activated the expression of A1, whose overexpression was reported to retard cell death elicited by IL-3 withdrawal (24). (iv) Overexpression of Bax or Bak accelerated IL-3 removal-induced cell death (4, 15, 33). (v) the Bcl-xL mRNA levels were recently shown to be affected by IL-3 in bone marrow-derived BaF-3 cells (23b). Since the Bcl-2 protein family is known to function by forming a homodimer or heterodimer with its relatives (reviewed in reference 6), an IL-3- or GM-CSF-activated signal, with its effect on the induction of some members (e.g., Mcl-1 and A1) and on posttranslational modification of other members (e.g., Bcl-2 and Bad), will certainly change the ratios of complexes that prevent or promote cell death. Alternatively, upon cytokine withdrawal from cells like TF-1 cells, the rapid degradation of Mcl-1 could again shift the equilibrium toward the formation of complexes that promote cell death. The short half-life of Mcl-1, as well as its being an immediate-early gene product, supports the notion that Mcl-1 plays an important role in the IL-3- or GM-CSF-regulated cell death pathway. Since overexpression of Mcl-1 to a level that is comparable to (e.g., in Mcl10-1) or even higher than (e.g., in Mcl10-2) that in GM-CSF-stimulated cells alone did not completely prevent TF-1 cells from undergoing factor-withdrawal-induced apoptosis, some other signals activated upon IL-3 or GM-CSF binding to their receptors must also be necessary for the survival function of these cytokines. These extra signals may include signals that lead to the posttranslational modification of Mcl-1 protein itself (three noncharacterized forms of proteins have been observed [54]), signals that lead to the activation of some other Bcl-2 family proteins (as described above), and possibly signals that lead to activation of other, yet to be identified IL-3- or GM-CSF-regulated genes. Taken together, all these possibilities suggest that Mcl-1 is one important component of the GM-CSF viability response.

Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL can form a heterodimer with Bax (33a, 41, 42, 58). In yeast two-hybrid systems, Mcl-1 also interacts with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL at a much lower affinity than with Bax (41). However, after many attempts, we found no evidence that these interactions occurred in mammalian cells or that Mcl-1 existed as a homodimer (33a). It has been reported that the ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax determines the survival or death of IL-3-depleted FL5.12 cells (33). It is possible that Mcl-1 utilizes a mechanism similar to that of Bcl-2 to antagonize a death signal. Mcl-1 has a half-life of ∼30 to 40 min irrespective of the presence or absence of GM-CSF. When dependent cells are deprived of GM-CSF, the synthesis of Mcl-1 is immediately interrupted. The Mcl-1 molecule that has been synthesized, due to its short half-life, quickly degrades. The shortage of Mcl-1 could lessen the possibility of the formation of an Mcl-1–Bax heterodimer, which would promote the formation of a Bax-Bax homodimer and induce cell death. More experiments are required to check the accuracy of this possible scenario.

The ligand-conjugated GM-CSF receptor is known to activate many downstream signaling molecules (10, 13, 34, 35, 39, 40). We were interested in knowing which part of the activated receptor is responsible for the induction of Mcl-1. From characterization of Ba/F3 cells harboring various C-terminally truncated mutants of the GM-CSF receptor, we observed that induction of Mcl-1 required the membrane-distal region of the receptor β chain (aa 573 to 755). This region of the receptor, according to published results (40), is likely to be important for the activation of the Ras, Raf, MAP, and p70 S6 kinases and phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Several studies have shown that the activation of these signaling molecules is important for the survival activity of various growth factors (1, 16, 22, 26, 52). It is possible that induction of Mcl-1 synthesis is one result of these survival signals activated after GM-CSF binding to its own receptor. By promoter deletion analysis, we found that the upstream region between positions −197 and −69 is required for cytokine induction of the mcl-1 gene. This region of the promoter contains DNA binding sites similar to the consensus sequences recognized by SIF and CRE-2 binding proteins (11, 49a). The SIF binding site is important for GM-CSF activation of the c-fos promoter (36a). More experiments are required to delineate which transcriptional factor is responsible for IL-3 or GM-CSF activation of the mcl-1 gene and how the activity of this transcriptional factor is modulated by the membrane-distal region of the β chain.

The anti-apoptotic activity of αβ573 cells was completely lost in medium containing hGM-CSF, whereas the mitogenic response of these cells under the same condition was partially impaired. This result suggests that the membrane-distal region of the receptor β chain also plays a role in the mitogenic response and that the receptor-activated mitogenic and anti-apoptotic signaling pathways may not be completely independent as previously suggested (16). As in αβ573 cells, the induction of Mcl-1 by hGM-CSF was abolished. This may be the result of the following two likely explanations. First, Mcl-1 may play a partial role in the mitogenic response of the receptor. This is based on the observation that the partial loss (∼40 to 50%) of mitogenesis of αβ573 cells in medium containing GM-CSF correlates with the loss of Mcl-1 expression in these cells. Second, Mcl-1 may not play any role in mitogenesis. This possibility is based on the fact that the induction of several other genes, such as c-jun, c-fos, and c-myc, is also lost in αβ573 cells. It is possible that the partial loss of mitogenic ability of αβ573 cells in medium containing hGM-CSF is simply the result of loss of expression of these three and possibly other, yet to be identified genes. More experiments will be necessary to differentiate these two possibilities.

During TPA-induced differentiation of ML-1 human leukemia cells, Mcl-1 is rapidly induced within 3 h of treatment, and its level may gradually decline thereafter to a baseline level upon completion of differentiation (54). We also found that Mcl-1 levels increased in TPA-induced differentiating TF-1 cells but decreased dramatically in TPA-induced apoptotic cells (data not shown). While these results suggest that Mcl-1 plays an important role in myeloid cell differentiation, its exact role during this process is unclear. Fairbairn et al. (5) reported that overexpression of Bcl-2 suppressed IL-3 withdrawal-induced apoptosis of a multipotent hematopoietic cell line, which allowed differentiation and development of these cells in the absence of added growth factors. It is possible that Mcl-1 plays a role similar to Bcl-2 or other survival factors during hematopoietic cell differentiation. That is, its major role in the differentiation process is to suppress apoptosis and allow the intrinsically determined differentiation program to proceed (5).

Mice deficient in Bcl-2 or Bcl-x have different phenotypes. Bcl-2-deficient mice undergo normal embryonic development but have fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair (31, 49). Bcl-x-deficient mice show massive cell death of immature hematopoietic cells and neurons (30). These results suggest that although both Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL have anti-apoptotic activities, their effects vary in different tissues and during different developmental stages. Following the same line of reasoning, Mcl-1 may exert another type of regulation of apoptosis, since it is widely distributed in various tissues and cell types and its expression profile differs slightly from that of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (20, 21, 54). Generation of Mcl-1 knockout mice may help us understand the real role of Mcl-1 in the biological system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. H. Chen and Douglas Platt for their critical reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by an intramural fund from Academia Sinica and by grants NSC-83-0203-B-001-002 and NSC-85-2311-B-001-043 from the National Science Council of Taiwan to H.-F. Yang-Yen and by grant DOH85-HR507 from the Department of Health to Chen-Kung Chou.

J.-R. Chao and J.-M. Wang contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed N N, Grimes L, Bellacosa A, Chan T O, Tsichlis P N. Transduction of interleukin-2 antiapoptotic and proliferative signals via Akt protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3627–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai K, Lee F, Miyajima A, Arai N, Yokota T. Cytokines: coordinators of immune and inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:783–836. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boise L H, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Postema C E, Ding L, Lindsen T, Turka L A, Mao X, Nunez G, Thompson C B. Bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chittenden T, Harrington E A, O’Connor R, Flemington C, Lutz R J, Evan G I, Guild B C. Induction of apoptosis by the Bcl-2 homologue Bak. Nature. 1995;374:733–736. doi: 10.1038/374733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairbairn L J, Cowling G J, Reipert B M, Dexter T M. Suppression of apoptosis allows differentiation and development of a multipotent hemopoietic cell line in the absence of added growth factors. Cell. 1993;74:823–832. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90462-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrow S N, Brown R. New members of the Bcl-2 family and their protein partners. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:45–49. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)90009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrow S N, White J H M, Martinou I, Raven T, Pun K T, Grinham C J, Martinou J C, Brown R. Cloning of a bcl-2 homologue by interaction with adenovirus E1B 19K. Nature. 1995;374:731–733. doi: 10.1038/374731a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia I, Martinou I, Tsujimoto Y, Martinou J C. Prevention of programmed cell death of sympathetic neurons by the Bcl-2 proto-oncogene. Science. 1992;258:304–304. doi: 10.1126/science.1411528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg M E, Ziff E B. Stimulation of 3T3 cells induces transcription of the c-fos proto-oncogene. Nature. 1984;311:433–438. doi: 10.1038/311433a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanazono Y, Chiba S, Sasaki K, Mano H, Miyajima A, Arai K, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. c-fps/fes protein-tyrosine kinase is implicated in a signaling pathway triggered by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-3. EMBO J. 1993;12:1641–1646. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05809.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyman S E, Comb M, Lin Y-S, Pearlberg J, Green M R, Goodman H M. A common trans-acting factor is involved in transcriptional regulation of neurotransmitter genes by cyclic AMP. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4225–4233. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ihle J N, Kerr I M. Jaks and Stats in signaling by the cytokine receptor superfamily. Trends Genet. 1995;11:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89000-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanakura Y, Druker B, Dicarlo J, Cannistra S A, Griffin J D. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate inhibits granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation in a human factor-dependent hematopoietic cell line. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:490–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly K, Cochran B H, Stiles C D, Leder P. Cell-specific regulation of the c-myc gene by lymphocyte mitogens and platelet-derived growth factor. Cell. 1983;35:603–610. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiefer M C, Brauer M J, Powers V C, Wu L L, Umansky S R, Tomei D, Barr P J. Modulation of apoptosis by the widely distributed Bcl-2 homologue Bak. Nature. 1995;374:736–739. doi: 10.1038/374736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinoshita T, Yokota T, Arai K, Miyajima A. Suppression of apoptotic death in hematopoietic cells by signalling through the IL-3/GM-CSF receptors. EMBO J. 1995;14:266–275. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitamura T, Tange T, Terasawa T, Chiba S, Kuwaki T, Miyagawa K, Piao Y F, Miyazono K, Urabe A, Takaku F. Establishment and characterization of a unique human cell line that proliferates dependently on GM-CSF, IL-3, or erythropoietin. J Cell Physiol. 1989;140:323–334. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041400219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korsmeyer S J. Regulators of cell death. Trends Genet. 1995;11:101–105. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)89010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozopas K M, Yang T, Buchan H L, Zhou P, Craig R W. Mcl-1, a gene expressed in programmed myeloid cell differentiation has sequence similarity to Bcl2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3516–3520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krajewski S, Bodrug S, Krajewska M, Shabaik A, Gascoyne R, Berean K, Reed J C. Immunohistochemical analysis of Mcl-1 protein in human tissues: differential regulation of Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 protein production suggests a unique role for Mcl-1 in control of programmed cell death in vivo. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:1309–1319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krajewski S, Krajewski M, Shabaik A, Wang H G, Irie S, Fong L, Reed J C. Immunohistochemical analysis of in vivo patterns of Bcl-X expression. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5501–5507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulik G, Klippel A, Weber M J. Antiapoptotic signalling by the insulin-like growth factor I receptor, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase, and Akt. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1595–1606. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamph W W, Wamsley P, Sassone-Corsi P, Verma I M. Induction of proto-oncogene Jun/AP-1 by serum and TPA. Nature. 1988;334:629–631. doi: 10.1038/334629a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Lee, S.-F., and J. J.-Y. Yen. Unpublished data.

- 23b.Leverrier Y, Thomas J, Perkins G R, Mangeney M, Collins M K L, Marvel J. In bone marrow derived Baf-3 cells, inhibition of apoptosis by IL-3 is mediated by two independent pathways. Oncogene. 1997;14:425–430. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23c.Lin E Y, Orlofsky A, Berger M S, Prystowsky M M. Characterization of A1, a novel hemopoietic-specific early-response gene with sequence similarity to bcl-2. J Immunol. 1993;151:1979–1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin E Y, Orlofsky A, Wang H G, Reed J C, Prystowsky M B. A1, a Bcl-2 family member, prolongs cell survival and permits myeloid differentiation. Blood. 1996;87:983–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J-J, Chao J R, Jiang M C, Ng S Y, Yen J J, Yang-Yen H F. Ras transformation results in an elevated level of cyclin D1 and acceleration of G1progression in NIH 3T3 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3654–3663. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minshall C, Arkins S, Freund G G, Kelley K W. Requirement for phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase to protect hemopoietic progenitors against apoptosis depends upon the extracellular survival factor. J Immunol. 1996;156:939–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minami Y, Nakagawa Y, Kawahara A, Miyazaki T, Sada K, Yamamura H, Taniguchi T. Protein tyrosine kinase syk is associated with and activated by the IL-2 receptor: possible link with the c-myc induction pathway. Immunity. 1995;2:89–100. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyajima A, Kitamura T, Harada N, Yokota T, Arai K. Cytokine receptors and signal transduction. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:295–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.001455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgenstern J P, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motoyama N, Wang F, Roth K A, Sawa H, Nakayama K I, Nakayama K, Negishi I, Senju S, Zhang Q, Fujii S, Loh D Y. Massive cell death of immature haematopoietic cells and neurons in Bcl-x-deficient mice. Science. 1995;267:1506–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.7878471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayama K-I, Nakayama K, Negishi I, Kuida K, Shinkai Y, Louie M C, Fields L E, Lucas P J, Stewart V, Art F W, Loh D Y. Disappearance of the lymphoid system in Bcl-2 homozygous mutant chimeric mice. Science. 1993;261:1584–1588. doi: 10.1126/science.8372353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nunez G, London L, Hockenbery D, Alexander M, McKearn J P, Korsmeyer S J. Deregulated Bcl-2 gene expression selectively prolongs survival of growth factor-deprived hemopoietic cell lines. J Immunol. 1990;144:3602–3610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oltvai Z N, Milliman C L, Korsmeyer S J. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 1993;74:609–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90509-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33a.Peng, H.-W., and H.-F. Yang-Yen. Unpublished results.

- 34.Pratt J C, Weiss M, Sieff C A, Shoelson S E, Burakoff S J, Ravichandran K S. Evidence for a physical association between the Shc-PTB domain and the βc chain of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12137–12140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quelle F W, Sato N, Witthuhn B A, Inhorn R C, Eder M, Miyajima A, Griffin J D, Ihle J N. Jak2 associates with the βc chain of the receptor for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and its activation requires the membrane-proximal region. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4335–4341. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raff M C, Barres B A, Burne J F, Coles H S, Ishizaki Y, Jacobson M D. Programmed cell death and the control of cell survival: lessons from the nervous system. Science. 1993;262:695–700. doi: 10.1126/science.8235590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36a.Rajotte D, Sadowski H B, Haman A, Gopalbhai K, Meloche S, Liu L, Krystal G, Hoang T. Contribution of both STAT and SRF/TCF to c-fas promoter activation by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1996;88:2906–2916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reed J C. Double identity for proteins of the Bcl-2 family. Nature. 1997;387:773–776. doi: 10.1038/42867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds J E, Yang T, Qian L, Jenkinson J D, Zhou P, Eastman A, Craig R W. Mcl-1, a member of the Bcl-2 family, delays apoptosis induced by c-Myc overexpression in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6348–6352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakamaki K, Miyajima I, Kitamura T, Miyajima A. Critical cytoplasmic domains of the common b subunit of the human GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-5 receptors for growth signal transduction and tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1992;11:3541–3549. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39a.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato N, Sakamaki K, Terada N, Arai K, Miyajima A. Signal transduction by the high-affinity GM-CSF receptor: two distinct cytoplasmic regions of the common beta subunit responsible for different signaling. EMBO J. 1993;12:4181–4189. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato T, Hanata M, Bodrug S, Irie S, Iwama N, Boise L H, Thompson C B, Golemis E, Fong L, Wang H G, Reed J C. Interactions among members of the Bcl-2 protein family analyzed with a yeast two-hybrid system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9238–9242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sedlak T W, Oltvai Z N, Yang E, Wang K, Boise L H, Thompson C B, Korsmeyer S J. Multiple Bcl-2 family members demonstrate selective dimerizations with Bax. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7834–7838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sentman C L, Shutter J R, Hockenbery D, Kanagawa O, Korsmeyer S J. Bcl-2 inhibits multiple forms of apoptosis but not negative selection in thymocytes. Cell. 1991;67:879–888. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strasser A, Harris A W, Cory S. Bcl-2 transgene inhibits T cell death and perturbs thymic self-censorship. Cell. 1991;67:889–899. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steller H. Mechanisms and genes of cellular suicide. Science. 1995;267:1445–1449. doi: 10.1126/science.7878463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson C B. Apoptosis in the pathogenesis and treatment of disease. Science. 1995;267:1456–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.7878464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsujimoto Y, Croce C M. Analysis of the structure, transcripts, and protein products of bcl-2, the gene involved in human follicular lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5214–5218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaux D L, Cory S, Adams J M. Bcl-2 promotes the survival of haemopoietic cells and cooperates with c-myc to immortalize pre-B cells. Nature. 1988;335:440–442. doi: 10.1038/335440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veis D J, Sorenson C M, Shutter J R, Korsmeyer S J. Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell. 1993;75:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80065-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49a.Wagner B J, Hayes T E, Hoban C J, Cochran B H. The SIF binding element confers sis/PDGF inducibility onto the c-fas promoter. EMBO J. 1990;9:4477–4484. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40b.Wang, J.-M., and H.-F. Yang-Yen. Unpublished results.

- 50.Williams G T, Smith C A, McCarthy N J, Grimes E A. Apoptosis: final control point in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 1992;2:263–267. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90198-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyllie A H. Apoptosis: cell death in tissue regulation. J Pathol. 1987;153:313–316. doi: 10.1002/path.1711530404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yao R, Cooper G M. Requirement for phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase in the prevention of apoptosis by nerve growth factor. Science. 1995;267:2003–2006. doi: 10.1126/science.7701324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang E, Zha J, Jockel J, Boise L H, Thompson C B, Korsmeyer S J. Bad, a heterodimeric partner for Bcl-xL and Bcl-2, displaces Bax and promotes cell death. Cell. 1995;80:285–291. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang T, Kozopas K M, Craig R W. The intracellular distribution and pattern of expression of Mcl-1 overlap with, but are not identical to, those of Bcl-2. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1173–1184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yen J J-Y, Hsieh Y C, Yen C L, Chang C C, Lin S, Yang-Yen H F. Restoring the apoptosis suppression response to IL-5 confers on erythroleukemic cells a phenotype of IL-5-dependent growth. J Immunol. 1995;154:2144–2152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yin X-M, Oltvai Z N, Korsmeyer S J. BH1 and BH2 domains of Bcl-2 are required for inhibition of apoptosis and heterodimerization with Bax. Nature. 1994;369:321–323. doi: 10.1038/369321a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer S J. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not Bcl-xL. Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou P, Qian L, Kozopas K M, Craig R W. Mcl-1, a bcl-2 family member, delays the death of hematopoietic cells under a variety of apoptosis-inducing conditions. Blood. 1997;89:630–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]