Abstract

Purpose

To assess the available evidence to support a genetic contribution and define the role of common and rare variants in tinnitus.

Methods

After a systematic search and quality assessment, 31 records including 383,063 patients were selected (14 epidemiological studies and 17 genetic association studies). General information on the sample size, age, sex, tinnitus prevalence, severe tinnitus distribution, and sensorineural hearing loss was retrieved. Studies that did not include data on hearing assessment were excluded. Relative frequencies were used for qualitative variables to compare different studies and to obtain average values. Genetic variants and genes were listed and clustered according to their potential role in tinnitus development.

Results

The average prevalence of tinnitus estimated from population-based studies was 26.3% for any tinnitus, and 20% of patients with tinnitus reported it as an annoying symptom. One study has reported population-specific differences in the prevalence of tinnitus, the white ancestry being the population with a higher prevalence. Genome-wide association studies have identified and replicated two common variants in the Chinese population (rs2846071; rs4149577) in the intron of TNFRSF1A, associated with noise-induced tinnitus. Moreover, gene burden analyses in sequencing data from Spanish and Swede patients with severe tinnitus have identified and replicated ANK2, AKAP9, and TSC2 genes.

Conclusions

The genetic contribution to tinnitus is starting to be revealed and it shows population-specific effects in European and Asian populations. The common allelic variants associated with tinnitus that showed replication are associated with noise-induced tinnitus. Although severe tinnitus has been associated with rare variants with large effect, their role on hearing or hyperacusis has not been established.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10162-024-00925-6.

Keywords: Tinnitus, Heritability, Genetics, GWAS, Prevalence, Rare variation

Introduction

Tinnitus has been considered an annoying symptom usually associated with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) or anxiety commonly found in the aging population [1]; its origin is multifactorial, but it is attributed mostly to environmental factors, noise exposure being the best-known risk factor [2]. Although tinnitus prevalence studies across different populations are scarce, multiple epidemiological studies in large cohorts of individuals with tinnitus, including twins [3, 4], adoptees [5], and familial aggregation studies [6] have reported evidence to support a significant tinnitus heritability, particularly for severe bilateral tinnitus [3, 7]. This hidden inheritance is explained by genetic variation in the DNA sequence and different genetic studies have reported common and rare variants associated with different tinnitus phenotypes [7–11].

A precise phenotype definition is an essential requisite for genetic association studies in complex traits, since the effect size of common and rare variants on the phenotype is small or large according to their allelic frequency [12]. For rare variants, the effect can be large, small, or negligible, but for common variants, the effect only can be small or moderate. As a result, the frequency of the tinnitus phenotype is related to the expected additive effect of common and rare variants, determining the effect size associated with the phenotype [13, 14].

The term “tinnitus disorder” has been proposed for a rare form of tinnitus reported in around 1–2% of the population that is associated with emotional distress, cognitive dysfunction, and/or autonomic arousal, leading to behavioral changes and functional disability [15]. These patients also report SNHL and hyperacusis [16] and should be considered a severe form of tinnitus requiring a multidisciplinary intervention for its management [17–19].

The aim of this systematic review is to assess the available evidence to support a genetic contribution and define the role of common and rare variants in the human genome to tinnitus.

Methods

This review has followed the guidelines from “Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” [20] (Annex 1). The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023440491).

Study Design

According to the methodology for systematic reviews, the items related to the PICO question are listed as follows, so the studies have been selected according to the following characteristics:

Participants: patients with a diagnosis for tinnitus, or referring it as a relevant symptom.

Intervention: determination of the prevalence of tinnitus, estimation of familial aggregation of this symptom, and measurement of concordance rate between twins. Description of genetic variants potentially linked to the development of chronic tinnitus

Controls: controlled and uncontrolled studies

Main outcomes: tinnitus prevalence across different populations, according to the ethnicity and genetic variants associated with tinnitus.

Study designs: case–control studies, population-based studies, family aggregation studies, and twin studies.

Search Strategy

The bibliographic search was conducted on 15 May 2023. PubMed and Scopus databases were used with the following combination of MesH terms: (“tinnitus”) AND (“prevalence” OR “inheritance” OR “heritage” OR “heritability” OR “genes” OR “genetics” OR “families” OR “familial” OR “twins”), and it was limited to original articles published in the last 10 years.

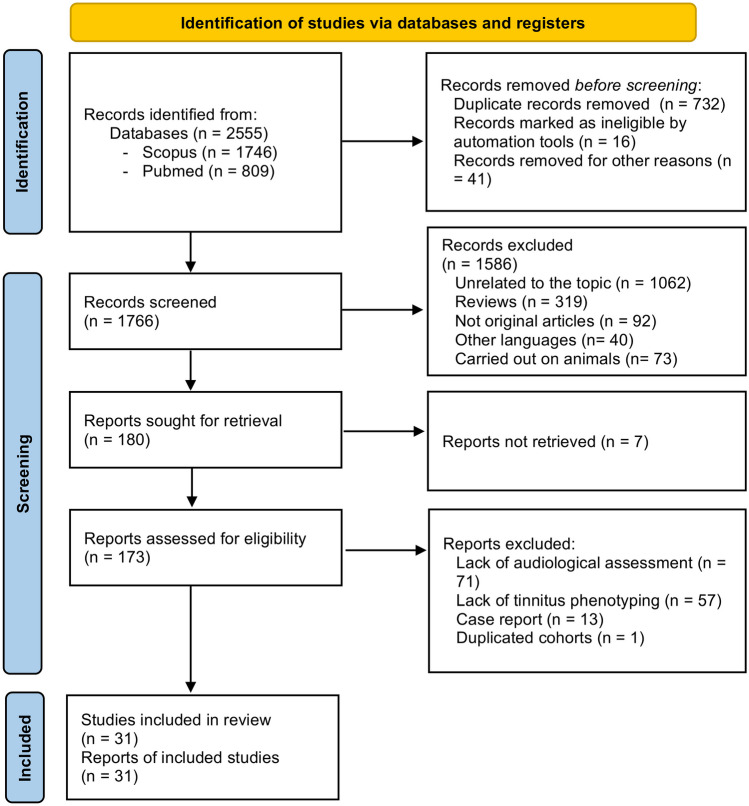

Once the search was performed in both databases, duplicates were eliminated and articles whose title or abstract did not adjust to the objectives of the review were discarded. The selected records were read and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The flowchart with the steps followed in this search is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for study selection

Exclusion Criteria

Studies without any audiological information (pure tone audiometry, auditory brain responses, self-report hearing loss…)

Studies with self-reported tinnitus without additional phenotyping by psychometric questionnaires

Animal studies

Studies published in other languages than English or Spanish

Single case reports

Data Extraction

Two reviewers (PP-C, AGM) independently extracted study characteristics and outcomes from all the included studies, and data were compared. A third reviewer (JALE) was consulted when a consensus could not be reached.

Each article was reviewed to extract the most relevant information according to the objective of this review. For population-based studies, information was collected on authors, year of publication, country and continent, target population, years of registry, sample size, and tinnitus prevalence for each study. Information on severe/bothersome tinnitus was retrieved for each record, according to open questions to patients, or quality-of-life questionnaires. In the familial aggregation studies, the information retrieved was as follows: authors and year of publication, sample size, number of relatives with chronic tinnitus, and the total number of siblings in each family. To sum up, in the genetic studies, we include the reference, country, study design, objective, sample size, sex, mean age, and main results of each study.

Data Synthesis

General information on the sample size, age, sex, tinnitus prevalence, severe tinnitus distribution, and SNHL was recorded. Qualitative variables are presented as relative frequencies to compare them among studies and to obtain average values. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviations (SD). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics package v22 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Quality Assessment

The quality of each study was analyzed according to the type of study. The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Exposure (ROBINS-E) tool [21] was used for observational epidemiology studies (prevalence studies) and candidate gene studies. GWAS studies were not assessed through the risk of bias, as no proper tool is available for such aim. The seven domains in this tool include the following: (1) bias due to confounding, (2) bias in the measurement of the exposure, (3) bias in the selection of participants into the study, (4) bias due to post-exposure interventions, (5) bias due to missing data, (6) bias in the measurement of outcomes, and (7) bias in the selection of the reported results. However, domain 4 was not relevant in this review and was excluded. The risk of bias ranged from “Low” to “Moderate,” “High,” or “Very High,” and the overall risk of bias was established based on the judgement for all the domains. A color scale was used to summarize it (green, low risk; yellow, moderate risk; red, high risk; black, very high risk). This has been summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment according to the risk of bias in non-randomized studies of exposures (ROBINS-E) tool. GWAS studies were excluded from this analysis*

*No specific tool is available for such aim

Results

According to the eligibility criteria, 31 studies (383,063 patients) were included (14 prevalence studies and 17 genetic studies). The following flowchart details the selection process and filtering of the included articles (Fig. 1).

Prevalence Studies for Tinnitus

Fourteen studies were selected to estimate the prevalence of tinnitus, including 88,920 subjects. Three were performed in North America, two of them in the USA [22, 23] and one in Canada [24], and eight were performed in Europe, including studies from Poland [25, 26], UK [27], Netherlands [28], Sweden [4], Germany [29, 30], and Denmark [31], and three in Asia (South Korea) [32–34]. The age ranged from 11 to 99 years, with 46.3 ± 15.2 years old.

The mean prevalence for hearing loss was 25% for all the population-based studies, and 34.7% in the subgroup of patients with self-reported tinnitus, based on pure tone audiograms. The hearing thresholds were 15.6 ± 10 dB HL (pure tone average, PTA) in subjects without tinnitus and 24.4 ± 19.3 dB HL in patients with tinnitus, respectively.

In terms of self-reported tinnitus, the mean prevalence from all the population-based studies was 26.9%, and 20.7% of patients with tinnitus described it as an annoying symptom, based on different phenotyping tools, such as THI, TFI, or a direct question about it burden level.

Next, we compared the prevalence of tinnitus in European, North American, and Asian studies, according to the ethnic background. European studies registered a mean prevalence of tinnitus of 37.3%, with a mean prevalence of 44.2% for SNHL and a mean age of 35.4 ± 26.4 years old. Studies based on the North American population recorded a mean prevalence of tinnitus of 19.1%, with a mean prevalence of 29.2% for SNHL and a mean age of 42.8 ± 1.2 years, and studies in the Asian population a mean prevalence of 20%, with a mean prevalence of 12.3% for SNHL and a mean age of 53.5 ± 3.7 years (Table 1). Two studies analyzed African American populations with a prevalence of 21.6% (mean age 53.7 ± 11.5 years old.

Table 1.

Summary of the main findings in tinnitus prevalence studies

| Reference | Country | Study population | Period of registration | Sample size | Average age in years (SD) | Tinnitus prevalence | Severe tinnitus | Hearing loss prevalence | Mean PTA values (dB HL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bogo et al. [4] | Sweden | Male mono- and dizygotic twin cohort | 1991–1995 | 1084 | 49.5 (34–78) | 13.5% | 2.8% | N/A |

No tinnitus: 8.48 dB Tinnitus: 14.15 dB |

| Dziendziel et al. [25] | Poland | Otosclerosis cohort | 2017 | 460 | 48 (± 11.5) | 64.8% | 22.8% | 66%* |

56.5 dB (AC); 26.7 dB (BC) |

| Hackenberg et al. [29] | Germany | Population-based cohort study | 2017–2020 | 8539 | 60.7 (± 13.7) | 28% | 40.4%e | 63.6%e | N/A |

| 41%f | 48.7%f | ||||||||

| 41.6%g | 51%g | ||||||||

| Hackenberg et al. [30] | Germany | Population-based cohort study | 2017–2020 | 4942 | 61 (± 13.3) | 26.1% | 37.6% | N/A |

No tinnitus: 17.17 dB Tinnitus: 22.67 dB |

| Humphriss et al. [27] | UK | 11-year-old children cohort study | 2013 | 7092 | 11 | 17.5% | 1.9% | N/A |

No tinnitus: 3.63 dB Tinnitus: 5.54 dB |

| Lima et al. [26] | Poland | Otosclerosis cohort | 2019 | 66 | 48.7 (± 9.1) | 72.7% | 33.3% | N/A |

49.4 ± 12.1 dB (AC); 23.1 ± 8.2 dB (BC) |

| Nemholt et al. [31] | Denmark | Longitudinal school-based cohort study | 2014 | 501 | 13.7 (± 1.1) | 54.3% | 34.6% | 8% | N/A |

| Oosterloo et al. [28] | Netherlands | Population-based cohort study | 2011–2016 | 6098 | 61.8 (± 11.5) | 21.4% | 12.3% |

29.2% (no tinnitus) 43.2% (tinnitus) |

No tinnitus: 29.1 dB (± 16.5) Tinnitus: 35.4 dB (± 19.2) |

| Park et al. [33] | South Korea | Population-based cohort study | 2009–2011 | 21,893 |

57.23 h 53.68i |

19.7% | 29.3% | 15.2% | N/A |

| Park et al. [34] | South Korea | Population-based cohort study | 2009–2011 | 10,061 | 49.7 (± 15.8) | 21.36% | 34.24% | 15.2% | N/A |

| Choi et al. [32] | South Korea | Population-based cohort study | 2010–2012 | 16,630 | N/A (12–99) |

20% (normal hearing) 18.8% (SNHL) |

5.65% | 6.4% | N/A |

| Choi et al. [22] | USA | Population-based cross-sectional study | 2011–2012 | 3669a | 43.8 (± 14.4)a | 16.5%a | 6.6%a | 8–26.1%a | N/A |

| 530b | 41.4 (± 13.9)b | 6.6%b | 2.4%b | 6.2–21.5%b | |||||

| 1329c | 43.2 (± 13.9)c | 18.8%c | 5.7%c | 9.9–28%c | |||||

| 1047d | 45.5 (± 14.9)d | 13.6%d | 4%d | 6.7–24.5%d | |||||

| 763e | 40 (± 14.4)e | 11.9%e | 16.7%e | 7.8–27.9%e | |||||

| House et al. [23] | USA | African-American cohort study | 2008–2014 | 1314 | 61.8 (± 11.5) | 29.5% | 35.4% | N/A |

No tinnitus: 19.4 dB (± 10.2) Tinnitus: 23.4 dB (± 11.8) |

| Ramage-Morin et al. [24] | Canada | Population-based cohort study | 2012–2015 | 6571 | NA (19–79) | 36.6% | 6.5% |

23.5% (SNHL) 14.5% (tinnitus + SNHL) |

N/A |

AC air conduction, BC bone conduction, PTA pure tone average, SD standard deviation, SNHL sensorineural hearing loss

aStudy cohort

bAsian American

cWhite

dBlack

eHispanic

fEuropean standard population 2013

gGerman standard population 2021

hmean age for the tinnitus group

imean age for the non-tinnitus group

*conductive/mixed hearing loss

Genetic Studies

Seventeen genetic studies were included [8, 9, 35–49], with a global sample size of 294,143 subjects (45.4% males), and 55,267 patients with tinnitus (18.8% males).

All the studies included reported no significant differences in terms of age between subgroups. Three studies excluded patients with SNHL [36, 42, 47], two studies reported no significant differences in audiograms between tinnitus and control subjects [39, 40], six studies included subjects with some degree of hearing impairment, including SNHL [8, 37, 45, 49], presbycusis [35], or noise-induced hearing loss [41], and the rest of them failed to report information on hearing stage [9, 38, 43, 44, 46, 48].

These genetic studies included four genome-wide association studies (GWAS) using genotyping arrays [9, 41, 46, 47], nine candidate gene studies [35, 36, 38–40, 42, 43, 45, 48], two sequencing studies using exome sequencing [8] and genome-sequencing data [49], and one mitochondrial DNA sequencing study [37]. Besides, there was a methylation study in the BDNF and GDNF genes [44].

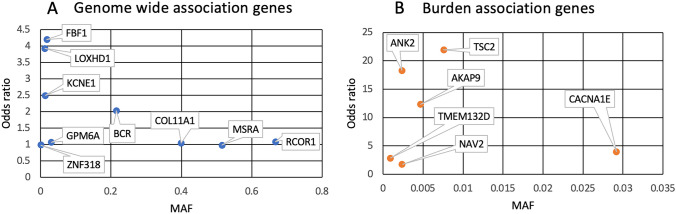

All of them sought to find genetic variants associated with the development of tinnitus (Table 2 and Supplementary information). Figure 2 summarizes the main genes reported in GWAS and gene burden analyses. None of the candidate gene studies was replicated.

Table 2.

Summary of the main findings in the genetic association studies obtained

| Reference | Country | Design | Genes | Main objective | Sample size | Sex (male/female) | Average age (years) | Tinnitus prevalence | SNHL prevalence | Results | Replication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amanat et al. [8] | Spain | WES | ANK2, TSC2, AKAP9 | To identify rare variants in synaptic genes by exome sequencing in patients with severe tinnitus | n = 91; cases: 59; controls: 32 | Cases: 42 M–17F; controls: unknown; replication cohort (cases: 42 M–55F; controls: unknown) | N/A | Cases: 100% (persistent tinnitus); controls: 0% (fluctuating tinnitus) |

Reference cohort: N/A Replication cohort: 64% |

Enrichment of rare missense variants in 24 synaptic genes in a Spanish cohort (more significant in PRUNE2, AKAP9, SORBS1, ITGAX, ANK2, KIF20B and TSC2 (p < 2E − 04)), compared with reference datasets. It was replicated for ANK2 in a Swedish cohort, and in a subset of 34 Swedish patients with severe tinnitus for ANK2, AKAP9 and TSC2 (p < 2E − 02). This association was not significant in a third cohort of 701 generalized epilepsy individuals without tinnitus |

Yes Independent WGS Swedish cohort (TIGER) n = 97 Cases: 34; controls: 63 Independent epilepsy WES cohort (CoGIE) n = 701 Cases: 152 Control: 549 |

| Bhatt et al. [48] | USA | Panel | KCNQ1, KCNE1 | To examine the relationship between selected genetic variants and measures of tinnitus in a sample of young musicians | n = 186; cases: 106; controls: 80 | Cohort: 99 M–87F | 20.3 | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | N/A | Individuals with at least one minor allele of rs163171 (C > T) in KCNQ1 exhibit significantly higher odds of reporting tinnitus compared to individuals carrying the major allele of rs163171. KCNE1 rs2070358 revealed a suggestive association (p = 0.049) with tinnitus, but the FDR corrected p-value did not achieve statistical significance (p < 0.05) | No |

| Bhatt et al. [9] | UK | GWAS | GPM6A | To conduct a GWAS analysis in the UK Biobank, adjusting for known environmental risk factors, and interrogating the genetic underpinnings of tinnitus-related distress | n = 132,438; cases: 38,525; controls: 93,013 | Cohort: 61,646 M–70,792F | 40– > 70 | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | N/A | A genomic region containing SNP (rs71595470) near GPM6A revealed a significant association with tinnitus, and 19 SNPs showed suggestive associations with tinnitus. Fifteen SNPs showed association with tinnitus-related distress. The enrichment analysis with FUMA identified 23 gene sets associated with tinnitus | No |

| Gallego-Martinez et al. [49] | Sweden | WGS | CACNA1E, NAV2, TMEM132D | To explore the association of rare single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), large structural variations (LSVs), and copy number variants (CNVs) in the genome of Swedish patients with severe tinnitus | n = 97 (TIGER cohort) |

TIGER cohort: 43 M–54F; Replication cohort: 146 M–152F |

46 ± 12.86 (TIGER cohort) 47 ± 11.52 (replication cohort) |

100% (TIGER cohort) 72.2% (replication cohort) |

64% (TIGER cohort; 79% in severe tinnitus cohort) 56% (replication cohort) |

Enrichment of rare missense variants in 6 and 8 high-constraint genes in SEVTIN and TIGER cohorts, respectively. There is also an enrichment of missense variants in the CACNA1E in both SEVTIN and TIGER. The burden of missense variants was replicated in 9 high-constrained genes in the JAGUAR cohort, including the NAV2, compared with NFE. Moreover, LSVs in constrained regions overlapping CACNA1E, NAV2, and TMEM132D were observed in TIGER and SEVTIN |

Yes Independent Swedish WES cohort (JAGUAR) n = 298; cases: 143; control: 155 |

| Haider et al. [35] | Portugal | Genotyping Cohort vs reference population | GRM7 | To study the relationships between presbycusis, tinnitus, co-morbidities, and the genotypes of GRM7 and NAT2, in a sample of older Portuguese adults | n = 78 | 33 M–45F | 64.6 (± 5.58) | 64.1%, 24% (severe tinnitus) | 24% | For GRM7 gen, individuals with a T/T genotype have a higher risk for age-related HL and 33% lower risk for tinnitus, compared to individuals with A/A and A/T genotype, respectively. Allele AT of GRM7 can have a statistically significant influence toward the severity of tinnitus | No |

| Jeong et al. [36] | South Korea | Genotyping Case–control study | BDNF, HTTLPR | To investigate the association of BDNF Val66Met or 5-HTTLPR polymorphisms with tinnitus and the mediating effects of psychological distress |

n = 338 Cases: 86; controls: 252 |

Cases: 41 M–45F; controls: 132 M–120F | Cases: 53.5 ± 13.7; controls: 53.1 ± 10.4 | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | SNHL patients were excluded | No association were found between groups regarding BDNF Val66Met (p = 0.142) and 5-HTTLPR (p = 0.054). The mean THI score was significantly higher in patients with the s/s genotype (47.9 (18.9)) than in those with l/s or l/l genotype (38.2 (25.5)) of 5-HTTLPR (p = 0.024) | No |

| Lechowicz et al. [37] | Poland | MiDNA sequencing Case–control study | Mitochondrial genes | To investigate the prevalence of tinnitus among Polish HL patients with identified pathogenic mtDNA variants | n = 114; cases: 17; controls: 97 | Cases: 7 M–10F; controls: N/A | N/A | Cases: 17.6%; control: 100% | Cases: 100%; controls: 69% | There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of tinnitus between HL patients with mtDNA variants and the general Polish population. There were no statistically significant differences in tinnitus annoyance (VAS-A) between al the subgroups of tinnitus patients. In Polish HL patients with tinnitus, m.7511 T > C was significantly more frequent than in patients without tinnitus (p = 0.0441) | No |

| Orenay-Boyacioglu et al. [38] | Turkey | Genotyping case–control study | GDNF | To investigate the role of GDNF polymorphisms in tinnitus pathophysiology | n = 94; cases: 52; controls: 42 | Cases: 33 M–19F; controls: 29 M–13F | Cases: 43.6 ± 10.7; controls: 39.3 ± 9.8 | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | N/A | No association was found for rs884344 and rs3812047 and subjects with tinnitus. Heterozygosity was significantly lower for GDNF rs1110149 polymorphism in tinnitus subjects compared to the controls (p = 0.02) | No |

| Orenay-Boyacioglu et al. [44] | WGBS specific regions | BDNF, GDNF |

To study the relationship between the promotor methylation of BDNF and GDNF genes and chronic tinnitus in peripheral blood samples |

n = 110; cases: 60; controls: 50 | Cases: 39 M–21F; controls: 31 M–19F | Cases: 36.5 (21–52); controls: 38.5 (23–54) | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | N/A | Statistically significant differences were detected between BDNF CpG6 and GDNF CpG3-5–6 methylation ratios in the comparison of control group and the chronic tinnitus patients (p = 0.002, 0.0005, 0.00003, and 0.0029, respectively) | No | |

| Rottenberg et al. [45] | Slovenia | Genotyping case–control study | GABA(A) beta-3 subunit gene | To explore associations between manifestation of tinnitus, auditory evoked potentials and genetic background of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA(A) receptors) to support the disinhibited feedback hypothesis of tinnitus generation | n = 131 | Cohort: 61 M–71F | Cohort: 52 ± 13.8 | Cohort: 100% | Cohort: 100% | Statistically significant difference in the tinnitus score in relation to the genotype of (CA)n tandem repeat of the GABRß3 receptor subunit gene (p = 0.002) | No |

| Urbanek et al. [47] | UK | GWAS | WDPCP | To define underlying genes that may preclude tinnitus, through a GWAS in the UK Biobank | n = 23,742; cases: 526; control: 19,047 | Cases: 226M300F; controls: 7315 M–11,732F | 40–70 | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | Self-reported SNHL patients were excluded | Seventeen suggestive SNP (p < 1e − 5) spanning 13 genes were identified in two sex-separated cohorts reporting chronic, bothersome tinnitus. A significant missense mutation in WDPCP (p = 3.959e − 10) was identified in the female cohort | No |

| Vanneste et al. [39] | USA | Genotyping case–control study | COMT | To study the role of COMT polymorphisms in the activity in the ventromedial PFC/anterior cingulate cortex and its effect on tinnitus perception | n = 60; cases: 40; controls: 20 | Cases: 28 M–12F; controls: 13 M–7F | Cases: 45.97 ± 14.19; controls: 45.6 ± 16.27 | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | No significant differences in audiograms between healthy controls and tinnitus patients | An interaction between the SNHL degree and the COMT Val158Met polymorphism can increase susceptibility to the clinical manifestation of tinnitus (loudness). No significant was observed in THI scores between the Val/Val genotype and Met carriers | No |

| Vanneste et al. [40] | USA | Genotyping case–control study | BDNF | To study the effect of BDNF Val/Met carriers and Val-homozygotes and perception of distress due to tinnitus | n = 110; cases: 55; controls: 55 | Cases: 38 M–17F; controls: 36 M–19F | Cases: 54.49 ± 15.3; controls: 54.63 ± 12.7 | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | No significant differences in audiograms between healthy controls and tinnitus patients | Val/Met carriers have a higher stress level in comparison to Val homozygotes (controls: F(1,106) = 66.97, p < 0.001; cases: F(1,106) = 54.68, p < 0.001). For the tinnitus group, we further show that there is a significant effect between Val homozygotes and Val/Met carriers for tinnitus-related distress (F(1,53) = 8.45, p = 0.005) | No |

| Watabe et al. [43] | Japan | Genotyping case–control study | BCR | To study the association between the grade of tinnitus distress and the genetic background, to identify prognostic markers | n = 138 | Cohort: 59 M–79F | Cohort: 61.3 ± 13.1 | Cohort: 100% | N/A | rs131702 of BCR is independent of depression in this study and is, therefore, a prognostic factor unique to tinnitus | No |

| Wells et al. [46] | UK | GWAS | RCOR1 | To conduct a GWAS analysis using self-reported tinnitus in the UK Biobank | n = 134,429; cases: 14,829; controls: 119,600 | Not defined | N/A | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | N/A | Three variants in close proximity to the RCOR1 gene reached genome wide significance: rs4906228 (p = 1.7E − 08), rs4900545 (p = 1.8E − 08) and 14:103042287_CT_C (p = 3.50E − 08) | No |

| Xie et al. [41] | China | GWAS | TNFRSF1A | To identify novel loci related to the risk of noise-induced tinnitus in the Chinese population | n = 298; cases: 65; controls: 233 | 100% males | Cases: 23.8 (1.6 SD); controls: 23.4 (1.6 SD) cases: 26.4 (3.9 SD)* controls: 24.5 (2.9 SD)* | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% | Cases: 100%; controls: 0% (noise exposure 100% subjects) | Two SNVs: rs2846071 (OR = 2.14 (1.96–3.4), combined p = 4.9 × 10−6); rs4149577 in the intron of TNFRSF1A gene at 12p13.31 (OR = 2.05 (1.9–2.51), combined p = 6.9 × 10−6), are associated to noise-induced tinnitus |

Yes Independent case and control cohort n = 413 Cases: 34; control: 379 |

| Yüce et al. [42] | Turkey | Genotyping case–control study | ACE; ADD1 | To investigate the relationship between severe chronic tinnitus and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) I/D and α-adducin (ADD1) G460W gene polymorphisms | n = 193; cases: 89; control: 104 | Cases: 41 M–48F; controls: 54 M–50F | Cases: 48.1 ± 13.5; controls: 45 ± 16 | Cases: 100% (severe tinnitus); controls: 0% | SNHL patients were excluded | Combined genotype frequencies for both ACE and ADD1 allelic variants were higher in the patient group than in the control group (p = 0.007) | No |

NFE non-Finnish European, (SN)HL (sensorineural) hearing loss

Fig. 2.

The genetic landscape of tinnitus. The effect of the variants associated with tinnitus as a function of their allelic frequency was observed in tinnitus genomic studies. A Blue dots represent OR for common variants associated with self-reported tinnitus in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Odds ratios from GWAS studies were calculated from beta values from their respective studies. Some studies have not been included since information on neither beta nor odds ratio was published. B Orange dots represent OR for genes enriched in rare missense variants in exome/genome sequencing studies selecting an individual with tinnitus extreme phenotype or specific population cohorts through burden test analysis. Odds ratios represent the entire gene enrichment, not a single variant. However, the MAF value represents the MAF of the most common variant reported in the analysis. If variants were not reported, the higher MAF values were used

The allelic variants and genes reported were associated with the following mechanisms:

Regulation of the neural activity, including the auditory pathway, such as the BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) gene and the GDNF (glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor) gene, both involved in the early development of central auditory pathway and the inner ear; the ANK2 (Ankyrin 2) gene, which encodes two different polypeptide including giant Ankyrin-2, a neuro-specific isoform variant expressed broadly in the central nervous system that keeps connectivity and neural activity in the CNS; the GPM6A (glycoprotein M6A) gene, which encodes neural glycoprotein M6a and plays an essential role in neural growth; the NAV2 (neuron navigator 2) gene, which is involved in neuronal and different sensory organs development; the TMEM132D (transmembrane protein 132D) gene, which encodes a transmembrane protein known for its capacity to act as a cell-surface marker for oligodendrocyte differentiation and neuronal morphogenesis; BCR (breakpoint cluster region) gene, which encodes the Rho family low molecular weight G-protein, abundantly expressed in the central nervous system and crucial for neurogenesis; and RCOR1 (REST corepressor 1) gene which encodes a component of a transcriptional repressor complex which represses neuronal gene expression in non-neuronal cells.

Receptors or transporters of neurotransmitters, including the polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) of the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4; the GRM7 gene, which encodes the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 7 (mGluR7); and the GABRB3 (GABA(A) beta-3 subunit) gene, which encodes a receptor for neuromediators involved in the descending part of the auditory pathways.

Metabolism and enzymatic pathways, such as the AKAP9 (A-kinase anchoring protein 9) gene, whose known function is binding to the protein kinase A (PKA) regulatory subunit to enclose it to different parts of the cell where phosphorylation is needed; the COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) gene, which inactivates dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine neurotransmitters in the mammalian brain; and the ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) gene, which encodes a crucial enzyme in the renin-angiotensin system and is related to the cardiovascular and body water regulation.

Voltage-gated channels and cellular homeostasis mediators, such as the TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis complex 2) gene, which encodes a tumor suppressor protein part of the TSC involved in the negative regulation of mTORC1 (mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1) activity; the CACNA1E (calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 subunit E) gene, which encodes a part of the “high-voltage activated” channel involved in the firing patterns modulation of neurons important for information processing, the ADD1 (α-adducin) gene, which is related to the volume and sodium homeostasis by interacting with the epithelial sodium channel; the KCNQ1 (potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1); and KCNE1 (potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily E regulatory subunit 1), which form a voltage-gated potassium channel expressed in the marginal cell membrane of the stria vascularis.

Inflammation, such as the TNFRSF1A (tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A) gene, which encodes a member of the TNF receptor superfamily of proteins involved in the TNF pathway. Two non-coding variants showed an association and were replicated in the Chinese population associated with noise-induced tinnitus (rs2846071; rs4149577).

Structural genes, such as WDPCP (WD repeat containing planar cell polarity) gene, which is related to the PCP effector proteins to regulate ciliogenesis during development and regulation of the actin cytoskeleton.

Mitochondrial DNA variants related to hearing loss.

Although four studies replicated their findings in another cohort, with similar characteristics to the discovery cohort [8, 9, 41, 49], none of the other studies replicated their findings in a second independent cohort.

Quality Assessment of Studies

The detailed analysis based on the seven domains of ROBINS-E is summarized in Table 3. According to this, fifteen of the studies had a moderate risk of bias [8, 22, 24–27, 29, 30, 35–37, 39–42], and twelve studies were evaluated to have a high risk of bias [4, 23, 28, 31–34, 38, 43–45, 48].

Discussion

Tinnitus is a multifactorial condition and a growing health problem associated with hearing loss. It is related to a wide variety of comorbidities, such as anxiety, hyperacusis, SNHL, headache and some otologic and neurologic conditions [50]. Moreover, tinnitus has a significant impact on the lives of patients who suffer from it and represents an economic burden for the health system [51].

Tinnitus has a significant heritability according to twins [3, 4], adoptees [5], and familial aggregation studies [6]; however, tinnitus heterogeneity and its association with several comorbidities make it difficult to decipher the genetic variation contributing to tinnitus. This challenge is higher with common variants located in non-coding regions that may show small effect by regulating multiple genes in different pathways. In this work, we have reviewed the records published in the last 10 years, on the genetic basis of tinnitus, after establishing a search strategy focused on prevalence studies to compare differences across different populations, genetic association studies, and familial aggregation studies.

One of the novel approaches of this systematic review is to consider the evaluation of the hearing as an essential part of the tinnitus phenotyping, as both conditions have a strong association [52]. For this reason, we have limited the selection to genetic studies that included the hearing thresholds of participants to control the confounding effect of genetic variants associated with hearing loss in tinnitus [53]. This has led to the exclusion of some GWAS reporting genetic associations with tinnitus; however, these genetic findings should be considered with caution, since these studies did not include hearing loss data and/or included military veterans with a history of noise exposure as replication cohort [8, 11, 49].

Several GWAS using biobank datasets have reported few common variants with significant associations with tinnitus [9, 11, 46, 47]; however, these studies were based on the participant responses to general health questionaries where tinnitus was self-reported, without a confirmed diagnosis in digital health records. Furthermore, these studies did not include the hearing thresholds, and it is difficult to determine if the reported associations are mediated by the underlying hearing loss, which is associated with tinnitus in the general population, particularly those over 50 years old. Finally, most of these studies did not include an independent replication cohort, and these associations have not been confirmed in later studies using other UK Biobank datasets [46, 47].

Prevalence and Tinnitus Phenotype

Tinnitus can receive different definitions, but there are some major characteristics, like its duration, that help to define this symptom. According to the latest clinical practice guidelines [54], chronic tinnitus is defined by a duration of at least 6 months. Most of the genetic studies present a homogeneous distribution of tinnitus patients, based on the duration criteria for chronic tinnitus. However, this information could be missed in some prevalence studies based on self-reported questionnaires [55].

Tinnitus disorder is a condition with a lower frequency in the general population. A more precise definition of tinnitus is needed for clinical and genomic research studies.

A standard approach to investigate the combined effect of environmental and genetic contributions in complex disorders is to compare prevalence across different populations with different ancestry living in the same geographical area or a specific population migrating to another continent. Here, we have compared the prevalence of tinnitus to determine the effect of ethnicity and population structure on tinnitus. The genetic uniformity, based on the reproduction between similar individuals or subjects with common ancestors, results in a decrease in the genetic diversity with a lower allele enrichment and less responsiveness to environmental changes [7].

Most studies report conservative tinnitus prevalence rates to be between 10 and 19% of adults [52, 56]. In addition, annoying tinnitus usually affects a low percentage of these patients [57]. Our results show slightly higher rates for both tinnitus prevalence (26.3%) and bothersome tinnitus (20%), which could be partly explained by the approach of the questions regarding tinnitus, in a self-reported questionnaire. Of note, the study of Choi et al. [22] performed in the USA reported a prevalence three times higher in white European compared to the Asian population and intermediate values for Hispanic and African-American individuals. Further prevalence studies in ethnically diverse countries are needed to compare tinnitus incidence in the same geographical areas according to ancestry.

Genetic Signature of Tinnitus

Some recent studies have integrated genetic knowledge into the tinnitus background, using different techniques. The main approaches focus on single variation and association analysis. GWAS have identified and replicated common variants in patients self-reporting tinnitus and noise-induced hearing loss, as well as tinnitus related to misophonia in population-based cohorts [9, 11, 41, 46, 47, 58]. GWAS studies have been useful in targeting potential regulators in tinnitus development in large population cohorts. UK Biobank has been demonstrated to be a valuable resource for association analysis using both self-reported questionnaires for tinnitus and genetic data. Different studies using this cohort have successfully pinpointed potential biomarkers for tinnitus; however, most of these studies lack a replication cohort to conclusively identify the causal genes, and these markers are common variants with a small effect [59, 60]. Of note, Trpchevska et al. [61] performed a large tinnitus GWAS including 723,166 participants from different cohorts, but no signal reached GWAS significance.

An alternative approach consists of selecting individuals with extreme phenotype (individuals with severe or mild symptoms at the ends of the phenotype distribution) and using omics data to identify rare and ultrarare variants by gene burden analysis [62]. This approach leads to more accurate identification of candidate genes. An enrichment of rare variants in patients with severe tinnitus has allowed the identification of target genes, which were replicated in an independent cohort [8]. Burden tests for rare biomarkers have been used successfully to identify potential genes with different rare variants enriched in tinnitus cohorts, using both exome and genome data [8, 49]. However, this overload of rare variation in certain genes may be a population-specific effect, and functional analyses of these rare variants are needed using cellular and animal models. Population stratification can be reasonably ruled out by segregation analysis of rare variants in multiple unrelated individuals.

A third approach is the combination of multiple bioinformatic tools analyzing different types of rare variants (i.e., single nucleotide variants, short indels, large structural variants, or copy number variants), as it has been described in other brain disorders [63, 64]. The identification of genes such as CACNA1E or NAV2, showing enrichment of missense and large structural variants in patients with tinnitus may lead to defining new druggable targets for tinnitus. However, this approach is limited by the clinical information of the cohort, in order to control the effect of other associated comorbidities.

A better understanding of the genetic structure of tinnitus may lead to explaining the difference in the phenotype. Though tinnitus may be a common symptom, tinnitus disorder, in its current definition as a condition associated with emotional, cognitive, or behavioral changes, may be considered a rare disease (less than 1–2% of the general population compared with tinnitus as a symptom). The differences between both may be the result of the combined effect of multiple common and rare variants, with an additive or epistatic effect leading to a complete or severe phenotype.

Limitations

This systematic review has some limitations. As most of the prevalence studies were performed by retrieving data from population-based registries, the information available for tinnitus phenotyping, including its time of evolution, laterality, or psychoacoustic characteristics, is incomplete. Tinnitus is a heterogeneous symptom, so it is essential to perform a deep phenotyping of this condition, including all the reported comorbidities to control association biases.

A second limitation is the low sample size associated with the tinnitus extreme phenotype approach that limits statistical power and cannot avoid population-specific effects. However, the main concern for most of the genetic studies is the lack of a second independent cohort to replicate genetic associations.

Since most of the reviewed studies exhibited a moderate to high risk of bias, the conclusions must be considered with caution, and future genetic studies should include a more precise selection of tinnitus individuals and a validation cohort.

Conclusions

The genetic contribution to tinnitus is mediated by common and rare variations, and it is likely to have population-specific effects.

Common allelic variants associated with tinnitus with a small effect have been associated with noise-induced tinnitus.

Rare missense variants with a large effect have been associated with severe tinnitus, although their effect on other comorbidities such as hearing or hyperacusis has not been established.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions PP-C is funded by the Andalusian Health Government (Grant RH-0150–2020). JAL-E has received funding from GNP-182 GENDER-Net Co-Plus Fund including support from “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434), under agreement LCF/PR/DE18/52010002, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, Grant Agreement No. 848261, and The University of Sydney to support research on genetics of Meniere disease (K7013_B3413 Grant). AG-M is funded by the Andalusian Health Government (Grant DOC_01677).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Patricia Perez-Carpena, Email: percarpena@ugr.es.

Jose A. Lopez-Escamez, Email: jose.lopezescamez@sydney.edu.au

References

- 1.Jafari Z, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. Age-related hearing loss and tinnitus, dementia risk, and auditory amplification outcomes. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;56:100963. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le TN, Straatman LV, Lea J, Westerberg B. Current insights in noise-induced hearing loss: a literature review of the underlying mechanism, pathophysiology, asymmetry, and management options. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;46(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s40463-017-0219-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maas IL, Brüggemann P, Requena T, Bulla J, Edvall NK, Hjelmborg JVB, Szczepek AJ, Canlon B, Mazurek B, Lopez-Escamez JA, Cederroth CR. Genetic susceptibility to bilateral tinnitus in a Swedish twin cohort. Genet Med. 2017;19(9):1007–1012. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogo R, Farah A, Karlsson KK, Pedersen NL, Svartengren M, Skjönsberg A. Prevalence, incidence proportion, and heritability for tinnitus: a longitudinal twin study. Ear Hear. 2017;38(3):292–300. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cederroth CR, PirouziFard M, Trpchevska N, Idrizbegovic E, Canlon B, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, Zöller B. Association of genetic vs environmental factors in Swedish adoptees with clinically significant tinnitus. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(3):222–229. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trpchevska N, Bulla J, Prada Hellberg M, Edvall NK, Lazar A, Mehraei G, Uhlen I, Schlee W, Canlon B, Gallus S, Lopez-Escamez JA, Cederroth CR. Sex-dependent aggregation of tinnitus in Swedish families. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12):3812. doi: 10.3390/jcm9123812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amanat S, Gallego-Martinez A, Lopez-Escamez JA. Genetic inheritance and its contribution to tinnitus. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2021;51:29–47. doi: 10.1007/7854_2020_155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amanat S, Gallego-Martinez A, Sollini J, Perez-Carpena P, Espinosa-Sanchez JM, Aran I, Soto-Varela A, Batuecas-Caletrio A, Canlon B, May P, Caderroth CR, Lopez-Escamez JA. Burden of rare variants in synaptic genes in patients with severe tinnitus: an exome based extreme phenotype study. EBioMedicine. 2021;66:103309. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt IS, Wilson N, Dias R, Torkamani A. A genome-wide association study of tinnitus reveals shared genetic links to neuropsychiatric disorders. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):22511. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-26413-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boussaty EC, Friedman RA, Clifford RE. Hearing loss and tinnitus: association studies for complex-hearing disorders in mouse and man. Hum Genet. 2022;141(3–4):981–990. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02317-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifford RE, Maihofer AX, Stein MB, Ryan AF, Nievergelt CM. Novel risk loci in tinnitus and causal inference with neuropsychiatric disorders among adults of European ancestry. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(11):1015–1025. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Escamez JA, Bibas T, Cima RF, Van de Heyning P, Knipper M, Mazurek B, Szczepek AJ, Cederroth CR. Genetics of tinnitus: an emerging area for molecular diagnosis and drug development. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:377. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan PF, Geschwind DH. Defining the genetic, genomic, cellular, and diagnostic architectures of psychiatric disorders. Cell. 2019;177(1):162–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visscher PM, Yengo L, Cox NJ, Wray NR. Discovery and implications of polygenicity of common diseases. Science. 2021;373(6562):1468–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.abi8206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Ridder D, Schlee W, Vanneste S, Londero A, Weisz N, Kleinjung T. Tinnitus and tinnitus disorder: theoretical and operational definitions (an international multidisciplinary proposal) Prog Brain Res. 2021;260:1–25. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cederroth CR, Lugo A, Edvall NK, Lazar A, Lopez-Escamez JA, Bulla J, et al. Association between hyperacusis and tinnitus. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2412. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henton A, Tzounopoulos T. What’s the buzz? The neuroscience and the treatment of tinnitus. Physiol Rev. 2021;101(4):1609–1632. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langguth B, Elgoyhen AB, Cederroth CR. Therapeutic approaches to the treatment of tinnitus. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;59:291–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langguth B, Kreuzer PM, Kleinjung T, De Ridder D. Tinnitus: causes and clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(9):920–930. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins J, Morgan R, Rooney A, Taylor K, Thayer K, Silva R et al (2022) Risk of bias in non-randomized studies of -exposure (ROBINS-E). Retrieved from https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/robins-e-tool

- 22.Choi JS, Yu AJ, Voelker CCJ, Doherty JK, Oghalai JS, Fisher LM. Prevalence of tinnitus and associated factors among Asian Americans: results from a national sample. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(12):E933–e940. doi: 10.1002/lary.28535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.House L, Bishop CE, Spankovich C, Su D, Valle K, Schweinfurth J. Tinnitus and its risk factors in African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(7):1668–1675. doi: 10.1002/lary.26964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramage-Morin PL, Banks R, Pineault D, Atrach M. Tinnitus in Canada. Health Rep. 2019;30(3):3–11. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x201900300001-eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dziendziel B, Skarżyński PH, Rajchel JJ, Gos E, Skarżyński H. Prevalence and severity of tinnitus in Polish otosclerosis patients qualified for stapes surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(6):1585–1590. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05317-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lima AF, Moreira FC, Costa IE, Azevedo C, Mar F, Dias L. Tinnitus and otosclerosis: an exploratory study about the prevalence, features and impact in daily life. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;26(3):e390–e395. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1739967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humphriss R, Hall AJ, Baguley DM. Prevalence and characteristics of spontaneous tinnitus in 11-year-old children. Int J Audiol. 2016;55(3):142–148. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2015.1120890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oosterloo BC, Croll PH, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Ikram MK, Goedegebure A. Prevalence of tinnitus in an aging population and its relation to age and hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(4):859–868. doi: 10.1177/0194599820957296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hackenberg B, Döge J, O’Brien K, Bohnert A, Lackner KJ, Beutel ME, et al. Tinnitus and its relation to depression, anxiety, and stress—a population-based cohort study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):1169. doi: 10.3390/jcm12031169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hackenberg B, O’Brien K, Döge J, Lackner KJ, Beutel ME, Münzel T, et al. Tinnitus prevalence in the adult population—results from the Gutenberg Health Study. Medicina (Lithuania) 2023;59(3):620. doi: 10.3390/medicina59030620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nemholt S, Schmidt JH, Wedderkopp N, Baguley DM. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence and factors associated with tinnitus and/or hyperacusis in children. Ear Hear. 2019;41(2):344–355. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi JE, Ahn J, Park HW, Baek SY, Kim S, Moon IJ. Prevalence of minimal hearing loss in South Korea. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0171635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park KH, Lee SH, Koo JW, Park HY, Lee KY, Choi YS, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of tinnitus: data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2011. J Epidemiol. 2014;24(5):417–426. doi: 10.2188/jea.je20140024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park RJ, Moon JD. Prevalence and risk factors of tinnitus: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010–2011, a cross-sectional study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2014;39(2):89–94. doi: 10.1111/coa.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haider HF, Flook M, Aparicio M, Ribeiro D, Antunes M, Szczepek AJ, et al. Biomarkers of presbycusis and tinnitus in a Portuguese older population. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:346. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeong JE, Jeon S, Han JS, Cho EY, Hong KS, Park SN, Kim JJ. The mediating effect of psychological distress on the association between BDNF, 5-HTTLPR, and tinnitus severity. Psychiatry Investig. 2021;18(3):187–195. doi: 10.30773/pi.2020.0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lechowicz U, Pollak A, Raj-Koziak D, Dziendziel B, Skarżyński PH, Skarżyński H, Ołdak M. Tinnitus in patients with hearing loss due to mitochondrial DNA pathogenic variants. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275(8):1979–1985. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-5028-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orenay-Boyacioglu S, Coskunoglu A, Caki Z, Cam FS. Relationship between chronic tinnitus and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor gene rs3812047, rs1110149, and rs884344 polymorphisms in a Turkish population. Biochem Genet. 2016;54(4):552–563. doi: 10.1007/s10528-016-9741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanneste S, Alsalman O, De Ridder D. COMT and the neurogenetic architecture of hearing loss induced tinnitus. Hear Res. 2018;365:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanneste S, Mohan A, De Ridder D, To WT. The BDNF Val(66)Met polymorphism regulates vulnerability to chronic stress and phantom perception. Prog Brain Res. 2021;260:301–326. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie C, Niu Y, Ping J, Wang Y, Yang C, Li Y, Zhou G. Genome-wide association study identifies new loci associated with noise-induced tinnitus in Chinese populations. BMC Genom Data. 2021;22(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12863-021-00987-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yüce S, Sancakdar E, Bağci G, Koç S, Kurtulgan HK, Bağcı B, Doğcan M, Uysal IÖ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) I/D and alpha-adducin (ADD1) G460W gene polymorphisms in Turkish patients with severe chronic tinnitus. J Int Adv Otol. 2016;12(1):77–81. doi: 10.5152/iao.2016.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watabe T, Kanzaki S, Sato N, Matsunaga T, Muramatsu M, Ogawa K. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in tinnitus patients exhibiting severe distress. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13023. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69467-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orenay-Boyacioglu S, Caliskan M, Boyacioglu O, Coskunoglu A, Bozkurt G, Cam FS. Chronic tinnitus and BDNF/GDNF CpG promoter methylations: a case–control study. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46(4):3929–3936. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-04837-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rottenberg J, Zallmann M, Kostrica R, Jurajda M, Talach T. The significance of (CA)n tandem repeat in GABA(A) beta-3 subunit gene in tinnitus manifestation. Ceska a Slovenska Neurologie a Neurochirurgie. 2014;77(4):473–478. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wells HRR, Abidin FNZ, Freidin MB, Williams FMK, Dawson SJ. Genome-wide association study suggests that variation at the RCOR1 locus is associated with tinnitus in UK Biobank. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6470. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85871-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urbanek ME, Zuo J. Genetic predisposition to tinnitus in the UK Biobank population. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):18150. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97350-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhatt IS, Dias R, Torkamani A. Association analysis of candidate gene polymorphisms and tinnitus in young musicians. Otol Neurotol. 2021;42(9):e1203–e1212. doi: 10.1097/mao.0000000000003279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallego-Martinez A, Escalera-Balsera A, Trpchevska N, Robles-Bolivar P, Roman-Naranjo P, Frejo L, Perez-Carpena P, Bulla J, Gallus S, Canlon B, Cederroth CR, Lopez-Escamez JA. Using coding and non-coding rare variants to target candidate genes in patients with severe tinnitus. NPJ Genom Med. 2022;7(1):70. doi: 10.1038/s41525-022-00341-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yew KS. Diagnostic approach to patients with tinnitus. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(2):106–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tziridis K, Friedrich J, Brüeggemann P, Mazurek B, Schulze H. Estimation of tinnitus-related socioeconomic costs in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):10455. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191610455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Axelsson A, Ringdahl A. Tinnitus–a study of its prevalence and characteristics. Br J Audiol. 1989;23(1):53–62. doi: 10.3109/03005368909077819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elmer S, Schmitt R, Giroud N, Meyer M. The neuroanatomical hallmarks of chronic tinnitus in comorbidity with pure-tone hearing loss. Brain Struct Funct. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00429-023-02669-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cima RFF, Mazurek B, Haider H, Kikidis D, Lapira A, Noreña A, Hoare DJ. A multidisciplinary European guideline for tinnitus: diagnostics, assessment, and treatment. HNO. 2019;67:10–42. doi: 10.1007/s00106-019-0633-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monacelli G, Zhang L, Schlee W, Langguth B, Ward TE, Murphy TB. Adaptive data collection for intraindividual studies affected by adherence. Biom J. 2023;65:e2200203. doi: 10.1002/bimj.202200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jarach CM, Lugo A, Scala M, van den Brandt PA, Cederroth CR, Odone A, et al. Global prevalence and incidence of tinnitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(9):888–900. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hallberg LR, Erlandsson SI. Tinnitus characteristics in tinnitus complainers and noncomplainers. Br J Audiol. 1993;27(1):19–27. doi: 10.3109/03005369309077885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smit DJA, Bakker M, Abdellaoui A, Hoetink AE, Vulink N, Denys D. A genome-wide association study of a rage-related misophonia symptom and the genetic link with audiological traits, psychiatric disorders, and personality. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:971752. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.971752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cresswell M, Casanova F, Beaumont RN, Wood AR, Ronan N, Hilton MP, Tyrrell J. Understanding factors that cause tinnitus: a Mendelian randomization study in the UK Biobank. Ear Hear. 2022;43(1):70–80. doi: 10.1097/aud.0000000000001074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dawes P, Fortnum H, Moore DR, Emsley R, Norman P, Cruickshanks K, et al. Hearing in middle age: a population snapshot of 40- to 69-year olds in the United Kingdom. Ear Hear. 2014;35(3):e44–e51. doi: 10.1097/aud.0000000000000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trpchevska N, Freidin MB, Broer L, Oosterloo BC, Yao S, Zhou Y, Nagtegaal AP, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies 48 risk variants and highlights the role of the stria vascularis in hearing loss. Am J Hum Genet. 2022;109(6):1077–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Amanat S, Requena T, Lopez-Escamez JA. A systematic review of extreme phenotype strategies to search for rare variants in genetic studies of complex disorders. Genes (Basel) 2020;11(9):987. doi: 10.3390/genes11090987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Halvorsen M, Huh R, Oskolkov N, Wen J, Netotea S, Giusti-Rodriguez P, et al. Increased burden of ultra-rare structural variants localizing to boundaries of topologically associated domains in schizophrenia. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1842. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15707-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Monlong J, Girard SL, Meloche C, Cadieux-Dion M, Andrade DM, Lafreniere RG, et al. Global characterization of copy number variants in epilepsy patients from whole genome sequencing. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(4):e1007285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.