Abstract

Calophyllum soulattri Burm.f. is traditionally used to treat skin infections and reduce rheumatic pain, yet genetic and genomic studies are still limited. Here, we present the first complete mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri. It is 378,262 bp long with 43.97% GC content, containing 55 genes (30 protein-coding, 5 rRNA, and 20 tRNA). Repeat analysis of the mitochondrial genome revealed 194 SSRs, mostly mononucleotides, and 266 pairs of dispersed repeats (30 bp) that were predominantly palindromic. There were 23 homologous fragments found between the mitochondrial and plastome genomes. We also predicted 345 C-to-U RNA editing sites from 30 protein-coding genes (PCGs) of the C. soulatrii mitochondrial genome. These RNA editing events created the start codon of nad1 and the stop codon of ccmFc. Most PCGs of the C. soulattri mitochondrial genome underwent negative selection, but atp4 and ccmB experienced positive selection. Phylogenetic analyses showed C. soulattri is a sister taxon of Garcinia mangostana. This study has shed light on C. soulattri’s evolution and Malpighiales’ phylogeny. As the first complete mitochondrial genome in Calophyllaceae, it can be used as a reference genome for other medicinal plant species within the family for future genetic studies.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Genetics

Subject terms: Cell biology, Genetics

Introduction

Calophyllum soulattri Burm.f. is a medicinally important evergreen tree belonging to the Calophyllaceae family of the order Malpighiales1. The natural distribution of this species extends from South Indo-China to the Caroline Islands (http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/). Its leaves, roots, and stem bark have been shown to exhibit antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and anti-obesity properties2,3. In C. soulattri, the most active secondary metabolites were calosubellinone, garsubellin B, and soulattrin4,5. Generally, the genus Calophyllum contains a diverse array of bioactive constituents, including xanthones and coumarins3.

Cellular respiration is a complex metabolic process involving the breakdown of sugar molecules in the presence of oxygen to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) which occurs in mitochondria6,7. Apart from their primary function in ATP production, mitochondria actively participate in several metabolic pathways. Notably, they are involved in the biosynthesis of specific amino acids, lipids, and heme–a crucial component of various enzymatic systems8. Moreover, mitochondria are thought to have originated from an ancient endosymbiotic event, wherein a free-living bacterium is engulfed by a eukaryotic cell9. This endosymbiotic theory accounts for the presence of a double membrane in mitochondria, along with their distinct circular DNA, resembling that of bacterial DNA10.

The plant mitochondrial genome typically consists of a circular DNA molecule, with sizes ranging from approximately 66 kb11 to about 11.7 Mb12 among the genomes sequenced to date. Nonetheless, subgenomic forms also exist because of repeat-mediated homologous recombination13. Conversely, plastomes have a more consistent regular structure characterized by a highly conserved arrangement of genes in a circular DNA molecule14. This is why the focus has predominantly been on plastomes in the realm of plant phylogenetic studies. In addition, the chloroplast genome of C. soulattri has been recently reported15. To date, the number of chloroplast genomes deposited in NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/browse#!/organelles/) is more than 9,000; along with more than 1,000 plastid genomes. In contrast, only more than 540 plant mitochondrial genomes are available in the database. However, no mitochondrial genome from the Calophyllaceae family has been included in the NCBI GenBank Organelle Genome repository. But several mitogenome studies have already been reported in the order Malpighiales such in Salix species, Bruguiera sexangula, Passiflora edulis, Populus species, and Garcinia mangostana16–20. The differences in the number of organelle genomes can be explained by the difficulties encountered during the assembly process. Mitochondrial genomes often possess repetitive regions and frequently undergo rearrangement events, which present challenges when traditional short-read sequencing methods are used for their assembly. Therefore, the process of obtaining complete and accurate mitochondrial genome sequences is more intricate than that of plastomes and often requires the application of advanced sequencing technologies21. Nevertheless, complete plant mitochondrial genomes have been successfully generated using traditional short reads22–24.

The number of protein-coding genes (PCGs) and introns in the mitochondrial genome are also highly diverse11,25–27. The angiosperm mitochondrial genome has two types of introns (Group I and Group II) that are distinguished based on their conserved folding structures and splicing mechanisms28. These introns undergo cis- or trans-splicing to generate continuous and functional transcripts29.

In this study, we successfully assembled the first complete mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri. This computationally feasible assembly, solely from Illumina short reads, enabled us to investigate and reveal genomic characteristics and structural features in detail. Our analysis examined the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) and repeat sequences. Additionally, we explored the intriguing possibility of chloroplast DNA transfer into the mitochondrial genome. We also compared the gene content of the mitochondrial genome with that of other closely related species of the order Malpighiales. Furthermore, we probed RNA editing sites and analyzed the selective pressure of PCGs. Finally, we studied the phylogenetic relationship of C. soulattri with other representative species from the order Malpighiales. The findings from this study provide valuable information regarding the evolutionary dynamics of Calophyllum species at the mitochondrial level. These results serve as a fundamental resource for the development of vital genetic tools for C. soulattri.

Results

The general structure and gene composition of C. soulattri mitochondrial genome

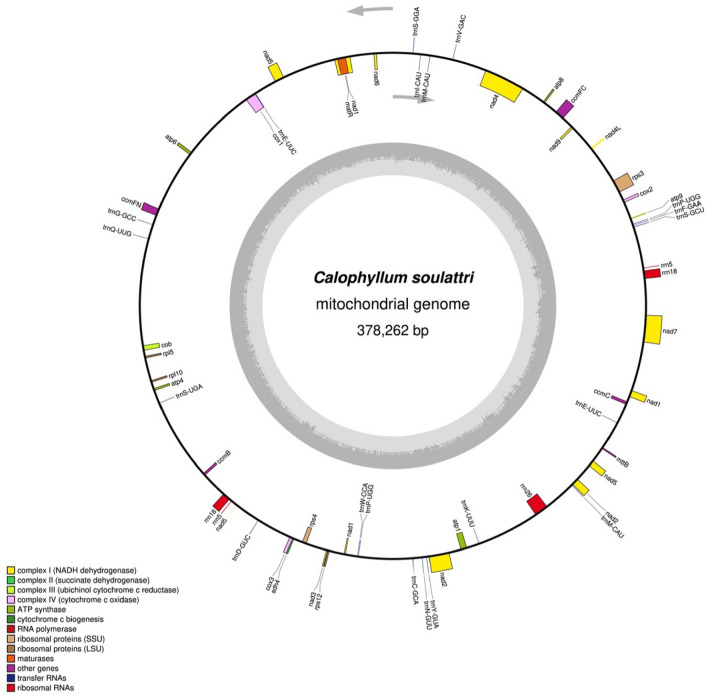

The mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri is circular and 378,262 base pairs (bp) in length with a total GC content of 43.97% (Fig. 1). This is the first complete mitochondrial genome of the species and in the Calophyllaceae family. The average sequencing depth of the genome was (Supplementary Figure S1c). It also contained 55 annotated genes of which 50 were unique (Table 1) and included 30 protein-coding genes (PCGs). The annotated core PCGs in the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri included five ATP synthase genes (atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, and atp9), four cytochrome biogenesis genes (ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc, and ccmFn), three cytochrome oxidase genes (cox1, cox2, and cox3), nine NADH dehydrogenase genes (nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, nad6, nad7, and nad9), one apocytochrome b gene (cob), one maturase R gene (matR), and one membrane transport protein gene (mttB). The annotated variable PCGs in the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri included the following: three small subunit of ribosomal proteins (rps3, rps4, and rps12), two large subunit of ribosomal proteins (rpl5 and rpl10), and one succinate dehydrogenase gene (sdh4). Furthermore, the mitochondrial genome harbored 17 distinct tRNA genes and three distinct rRNA genes, which were annotated. Some tRNA genes had two copies such as trnE-UUC, trnM-CAU, and trnP-UGG. Similarly, there were rRNA genes with two copies, in particular rrn18 and rrn5.

Figure 1.

The circular map of Calophyllum soulattri mitochondrial genome. The gray arrows show the direction of transcription. Genes inside the circle are transcribed clockwise while genes outside the circle are transcribed counterclockwise. The gray bars inside the circle represent the GC content of the sequence.

Table 1.

Annotation of genes in Calophyllum soulattri mitochondrial genome.

| Group | Genes |

|---|---|

| Subunit of ATPase | atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, atp9 |

| Cytochrome c biogenesis | ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc, ccmFn |

| Apocytochrome b | cob |

| Subunit of cytochrome c oxidase | cox1, cox2, cox3 |

| Maturase R | matR |

| Transport membrane protein | mttB |

| Subunit of NADH dehydrogenase | nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, nad6, nad7, nad9 |

| Small subunit of ribosome | rps12, rps3, rps4 |

| Large subunit of ribosome | rpl10, rpl5 |

| Subunit of succinate dehydrogenase | sdh4 |

| rRNA | rrn18 (), rrn26, rrn5 () |

| tRNA |

trnE-UUC (), trnM-CAU (), trnP-UGG (), trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnF-GAA, trnG-GCC, trnK-UUU, trnl-CAU, trnN-GUU, trnQ-UUG, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA, trnS-UGA, trnV-GAC, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA |

Among the 30 PCGs, nine had introns (Supplementary Figure S2). These included genes with a single cis-spliced intron, particularly ccmFc, cox1, rps3, and trnE-UUC. We also identified PCGs with many introns. Specifically, nad4 contains three cis-spliced introns, whereas nad5 contains two trans-spliced introns and two cis-spliced introns. On the other hand, nad7 contains four cis-spliced introns. Moreover, nad1 contains two trans-spliced introns and two cis-spliced introns while nad2 harbored one trans-spliced intron and three cis-spliced introns.

Comparison of gene content with other related Malpighiales mitochondrial genome

The gene content of C. soulattri was analyzed and compared with that of other species in the order Malpighiales (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S2). Our findings showed that all the core genes were present in every species. Additionally, it is evident that not all species contain the same set of large and small subunits of ribosome genes, as well as succinate dehydrogenase genes. Furthermore, the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri was found to have lost nine variable genes, namely, rpl2, rpl16, rps1, rps7, rps10, rps13, rps14, rps19, and sdh4.

Figure 2.

Distribution of protein-coding genes in the mitogenomes of representative species in the order Malpighiales. Red boxes indicate that the gene is present while white boxes indicate that the gene is absent. Calophyllum soulattri is labelled with an asterisk (*).

Analysis of codon usage bias

Codon usage analysis was conducted on 30 PCGs within the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S4). Codons exhibiting a relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) value greater than 1 were preferentially utilized by specific amino acids, revealing a prevalent universal codon usage pattern among mitochondrial PCGs. Interestingly, alanine (Ala) exhibited a pronounced preference for GCU codons, with the highest RSCU value observed among mitochondrial PCGs (RSCU = 1.57). This was followed by histidine (His) and proline (Pro), with a strong bias towards CAU and CCU codons, respectively (RSCU = 1.56). The codons UUU (Phe), AUU (Ile), and UUA (Leu) emerged as the most frequently used in C. soulattri. These observations suggest that codon preferences likely evolved through extensive selective pressures acting on C. soulattri over an extended evolutionary timeframe.

Figure 3.

Codon usage bias of the mitochondrial PCGs of Calophyllum soulattri. The RSCU refers to relative synonymous codon usage. Codon families are labelled on the x-axis. Values on top of the bars refer to amino acid usage.

Repeat elements of C. soulattri mitochondrial genome

Simple sequence repeats, also known as microsatellites or short tandem repeats (STR), are repetitive DNA sequences consisting of short units of nucleotides, typically 1-6 base pairs30. We identified 194 SSRs in C. soulattri mitochondrial genome. Most of these (137 repeat units) were mononucleotide repeats, accounting for 70.62% of the total SSRs (Fig. 4A). This was followed by tetranucleotides, which consisted of 20 repeat units (10.31%). In addition, we identified 17 dinucleotide repeat units, 15 trinucleotide repeat units, and 5 pentanucleotide repeat units, accounting for 8.76%, 7.73%, and 2.58% of the total SSRs, respectively.

Figure 4.

Repetitive elements in the mitochondrial genome of Calophyllum soulattri. (a) Abundance of simple sequence repeats (SSRs), and (b) the number and types of dispersed repeats (30bp) identified in C. soulattri mitochondrial genome.

Dispersed repeats were detected within the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri (Fig. 4B). The majority of repeats were comprised of both palindromic and forward sequences. There were 266 pairs of repetitive sequences, each with a length equal to or exceeding 30 bp. Among these pairs, 146 pairs were identified as palindromic repeats, 118 as forward repeats, and two as reverse repeats. However, no instances of complementary repeats have been identified in the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri.

Most dispersed repeats were shorter than 100 bp, with only nine repeats exceeding 100 bp. Notably, the longest forward repeat identified was 10,913 bp in length, followed by a forward repeat with a length of 1,140 bp (Supplementary Table S5). The combined length of these dispersed repeats was 23,456 bp, constituting 6.2% of the entire mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri. This observation underscores the prevalence of repeats in the mitochondrial genome.

Analysis of plastid DNA insertion in the mitochondrial genome

Mitochondrial plastid DNAs (MTPTs) are specific DNA fragments originating from chloroplasts that are present within the mitochondrial genome31. We identified 23 fragments in the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri that are highly homologous to the chloroplast genome. Figure 5 shows the locations of the identified MTPTs. Many complete chloroplast tRNA genes were found in MTPTs, including trnV-GAC, trnS-GGA, trnD-GUC, trnW-CCA, trnN-GUU, and trnM-CAU. Additionally, there is a chloroplast gene fragment, specifically rrn16, that is homologous to rrn18 in the mitochondrial genome. Nevertheless, there were homologous fragments without gene annotations (Supplementary Table S6) that warrant further studies.

Figure 5.

Circular map showing the distribution of MTPTs on the mitochondrial genome of Calophyllum soulattri. The blue and green outer arcs represent the mitochondrial genome (mt) and chloroplast genome (cp), respectively. The gray links in the inner circle represent the MTPTs on C. soulattri mitochondrial genome.

Analysis of RNA editing site

We identified several RNA editing events in 30 PCGs from the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri. Using Deepred-Mt with default parameters, we detected 345 potential RNA editing sites (Fig. 6). It is worth noting the substantial heterogeneity in the number of RNA editing sites among different genes. Among the PCGs, nad4 exhibited the highest number, with 35 RNA editing sites, which surpass all other genes. This was followed by the ccmB gene, which displayed 33 RNA editing sites. Conversely, the atp8, rpl10, and sdh4 genes displayed only one RNA editing site, whereas none of the atp9 and cob genes. All RNA editing in the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri was C-to-U editing (Supplementary Table S7).

Figure 6.

Number of RNA editing sites identified in the PCGs of Calophyllum soulattri mitochondrial genome. The abscissa shows the name of the genes, while the ordinate shows the number of edited sites.

Analysis of genes under selective pressure

In this study, we calculated the Ka (non-synonymous substitution rate) and Ks (synonymous substitution rate) substitution ratio (Ka/Ks) of 29 shared PCGs of C. soulattri and Passiflora edulis. The majority of PCGs exhibited Ka/Ks ratios below 1, indicating the prevalence of purifying selection (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table S8). This also suggests that a considerable portion of the mitochondrial genes underwent selective purification, which may contribute to the preservation of normal mitochondrial function. However, there were PCGs with Ka/Ks ratios greater than 1, particularly atp4 and ccmB. These genes were associated with the mitochondrial respiratory chain. The elevated Ka/Ks ratios in these genes suggest that positive selection had occurred, leading to the emergence of beneficial traits during evolution.

Figure 7.

The Ka/Ks ratios for 29 protein-coding genes of Calophyllum soulattri. The red broken line represents Ka/Ks ratio of 1.0, indicating neutral selection.

Phylogenetic analyses

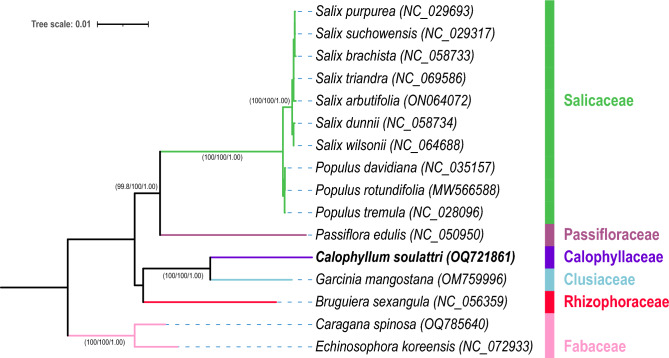

To elucidate the phylogenetic position of C. soulattri, we obtained the mitochondrial genome sequences of 14 Malpighiales species and two non-Malpighiales species as outgroups from the NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). We used all core PCGs and one shared variable gene (rps3) for the phylogenetic analyses. Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) phylogenetic analyses revealed the separation of 16 species into distinct taxonomic clusters based on their respective families (Fig. 8). Furthermore, the results indicated that C. soulattri is a sister taxon to G. mangostana, which is strongly supported by its high clade credibility (Shimodaira-Hasegawa-like approximate likelihood ratio test or SH-aLRT = 100, Ultrafast Bootstrap or UFBoot = 100, Posterior Probability or PP = 1.00). The phylogenetic tree also demonstrated concordance with the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV classification. This affirms the taxonomic position of C. soulattri in the family Calophyllaceae, which shares a close phylogenetic relationship with both Clusiaceae and Rhizophoraceae. Significantly, a substantial number of nodes exhibited high support values, indicating a high degree of confidence and reliability in phylogenetic analyses.

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic tree of 14 plant species from the order Malpighiales and two non-Malpighiales species inferred from IQ-TREE and MrBayes based on 25 concatenated orthologous mitochondrial PCGs with the best-fit partitioning strategy. Two species from Fabaceae (Caragana spinosa and Echinosophora koreensis) were used as outgroups. Values inside parenthesis beside branches are SH-aLRT/UFBoot/PP support. The tree scale indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. The mitochondrial genome obtained from this study was highlighted in bold.

Discussion

In this study, we sequenced and assembled the complete mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri, which was 378,262 bp long. Although we used only short reads to assemble the genome, we were still able to generate a computationally feasible mitochondrial genome assembly. It is also crucial to acknowledge the potential existence of isoforms and multi-chromosomal mitochondrial genome structure13. This structural diversity of the mitochondrial genome is evident in many medicinal and economically important plant species32–42.

The mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri comprises 24 core PCGs, similar to other typical angiosperms43–45, and six variable genes. It is also relatively larger than the mitochondrial genome of G. mangostana by 1.89%20. This disparity can be attributed to the presence of a greater number of ribosomal proteins and a succinate dehydrogenase gene in the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri (Fig. 2). During evolution, it is possible that some PCGs underwent loss and were subsequently transferred to the nuclear genome46,47. This phenomenon has been observed in the mitochondrial genomes of some angiosperms, such as Citrullus lanatus and Cucumis melo48.

Repeat analysis of the C. soulattri mitochondrial genome revealed 194 SSRs. Among these, the majority were mononucleotide (A/T) repeats similar to those reported in Gleditsia sinensis, Gentiana spp., and Camellia gigantocarpa49–51. The prevalence of these repeats may be attributed to the low GC content of the mitochondrial genome. This finding is consistent with observations made in the mitochondrial genomes of Phaseolus vulgaris and Pereskia aculeata32,39. In addition, we reported a significant presence of dispersed repeats within the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri. These dispersed repeats primarily consisted of forward and palindromic repeats. Interestingly, this finding is also similar to the mitochondrial genomes of Saposhnikovia divaricata, Artemisia giraldii, and Momordica charantia52–54.

Angiosperms exhibit significant inter-organelle communication of genetic material within their cells. This communication primarily involves the transfer of DNA from the chloroplasts to the mitochondrial genome55. Here, we discovered 23 MTPTs in the C. soulattri mitochondrial genome. Most of the MTPTs are tRNA genes. The existence of these chloroplast-derived tRNAs in the mitochondrial genome is likely due to horizontal gene transfer (HGT)56. Furthermore, MTPTs are also well reported in other angiosperms such as Salvia miltiorrhiza, Taraxacum mangolicum, and Abelmoschus esculentus37,38,41.

Eukaryotes usually employ a process called RNA editing to modify the coding regions of transcribed RNA by inserting, deleting, or converting nucleotide bases57. Extensive studies have demonstrated a wide prevalence of RNA editing in higher plant mitochondria58. RNA editing often plays a crucial role in gene expression in the mitochondrial genomes of plants59. Primarily, it involves a deamination reaction that converts cytosine (C) to uracil (U) at specific sites in most angiosperms60. RNA editing events in the mitochondrial genome have been reported in Prunus salicina and S. officinalis36,37. We documented 345 RNA editing events in the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri. Significantly, our study revealed that RNA editing events generated the start codon of nad1 and stop codon of ccmFc (Supplementary Table S3, Supplementary Table S7), which was also observed in G. mangostana20. The creation of new start and stop codons gives rise to proteins that exhibit high conservation and homology. This enhances gene expression in mitochondria61.

Analysis of Ka/Ks ratio yields valuable insights into the evolutionary dynamics of plant mitochondrial genes62. A Ka/Ks ratio of 1 signifies neutral mutation, whereas a Ka/Ks ratio indicates negative or purifying selection. Conversely, a Ka/Ks ratio suggests the influence of positive or diversifying selection. Here, most mitochondrial genes displayed a pronounced conservation pattern, indicative of neutral or negative selection. Nonetheless, our analysis revealed two specific genes, atp4 and ccmB, exhibiting a Ka/Ks ratio greater than 1.0, suggesting the likelihood of positive selection during their evolutionary history. The atp4 gene encodes a subunit of the F0 (F-type ATPase) sector and its protein product contributes to proton transmembrane transfer, which is fundamental to ATP synthesis. The F0 sector serves as a proton channel through which protons (H+) flow back into the mitochondrial matrix63. The F0 subunit encoded by atp4 forms part of the proton channel, allowing protons to flow back into the matrix through the ATP synthase complex64. The ccmB gene encodes a ccmB-like mitochondrial protein involved in the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes, which are essential components of electron transfer processes. The ccmB gene product, a ccmB-like mitochondrial protein, plays a key role in the transportation of heme to the mitochondrion65,66. Ensuring the proper export and integration of heme into c-type cytochromes is vital for the optimal functioning of these electron transfer proteins. These two genes (atp and ccmB) may have undergone adaptive changes, potentially developing new functions. These adaptations may have occurred in response to environmental or physiological pressures, possibly contributing to stress resistance. In contrast, atp9 experienced robust negative selection. The atp9 gene encodes a subunit of the ATP synthase complex. The ATP9 protein plays a significant role in proton-transporting ATP synthase activity. Moreover, it is very important in the regulation of proton translocation during proton transfer within the ATP synthase complex64. The pronounced purification and selection of this gene are likely due to its integral biological function in plants. Without functional atp9 genes and the ATP synthase complex, plants would be unable to efficiently generate ATP, leading to severe impairment of energy-dependent processes that are essential for their growth, development, and survival. These findings are consistent with observations in Scuttelaria tsinyunensis, where atp4 and ccmB showed evidence of positive selection, whereas atp9 exhibited strong purifying selection41. Furthermore, atp4 and ccmB were also found to be under positive selection in Salix wilsonii16.

The mitochondrial genome of vascular plants exhibits a slow evolutionary rate, characterized by significantly low mutation rates67. This distinctive feature renders it a valuable tool for phylogenetic research, facilitating the study of the evolutionary relationships among plant species. Our current phylogenetic analysis reveals that C. soulattri is closely related to G. mangostana and B. sexangula, confirming previous findings using plastid and nuclear DNA sequences15,68.

Conclusion

We successfully assembled and annotated the complete C. soulattri mitochondrial genome. The genome was circular and 378,262 bp in length, with a GC content of 43.97%. A detailed analysis of the genome provides valuable genetic resources for conducting phylogenetic studies on C. soulattri, and lays a solid foundation for future research on mitochondrial genomes within the Calophyllaceae family.

Methods

Plant material, total genomic DNA extraction, and sequencing

The fresh leaves of C. soulattri used in this study were collected from the forest trees germplasm of the Metallophytes Laboratory at the University of the Philippines, Los Baños, Laguna (). A leaf specimen was submitted to the Jose Vera Santos Memorial Herbarium at the Institute of Biology, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City and compared with accession number 14288. Leaf samples were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at – refrigerator prior to DNA extraction. High-quality total genomic DNA was extracted using a previously described protocol15. The processed total gDNA samples were submitted to a local distributor for outsourced next-generation sequencing to Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, South Korea). Briefly, paired-end libraries were generated using TruSeq DNA Nano Library Prep kit and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (San Diego, California, USA). The sequencing data were deposited in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under BioProject ID PRJNA891016.

Mitochondrial genome assembly and annotation

The mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri was assembled using GetOrganelle v1.7.6.169 using the following parameters: -R 20 -k 21,45,65,86,105 -p 1000000 -F embplant_mt. In addition, NOVOPlasty v4.3.170 was used to generate artificial long-reads or scaffolds. Briefly, makeblastdb was used to construct a database of the assembly generated by NOVOPlasty and then using the BLASTn program, contigs produced by GetOrganelle were searched against the database. Assessment and manual editing of the assembly to obtain a complete circular contig were done with the aid of Bandage v0.8.171. The assembled C. soulattri mitogenome was annotated using IPGMA (http://www.1kmpg.cn/mga). The assembled mitogenome of C. soulattri was also BLAST-searched against protein-coding genes (PCGs) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes deposited at NCBI to verify the annotation results. Subsequently, manual editing and correction of erroneous annotations were performed using Apollo software v1.11.872. The physical circular mitochondrial genome map of C. soulattri was generated using Organellar Genome DRAW (OGDRAW) v1.3.1 program with default parameters73. The mitochondrial genome sequence was deposited in GenBank through BankIt (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/WebSub/) and obtained the accession number OQ721861 or NC_079842.1.

Analysis of codon usage and selection pressure of mitochondrial protein-coding genes

We extracted the protein-coding genes (PCGs) using PhyloSuite v1.2.374 to parse the GenBank format file of C. soulattri mitochondrial genome. CodonW v1.4.2 (https://codonw.sourceforge.net/) was used to analyze the codon usage of mitochondrial PCGs by calculating RSCU values. The Ka/Ks_Calculator v2.075 with the MLWL method was used to calculate the Ka/Ks of shared mitochondrial PCGs of C. soulattri and P. edulis (Accession No. NC_050950) in the Passifloraceae family of the order Malpighiales was used as an outgroup.

Analysis of repeat elements

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were detected in the mitochondrial genome of C. soulattri using MISA-web (https://www.web-blast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/)76 with the following parameters: minimum number of repeats of mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotides were set as 8, 5, 4, 3, 3, and 3, respectively. For long repeat sequences, we used RePuter (https://www.bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer)77 to calculate forward, reverse, palindromic, and complementary repeat sequences with the following parameters: hamming distance of 3 and minimal repeat size of 30 bp, and e-value was limited to less than .

Analysis of mitochondrial plastic DNAs (MTPTs)

To identify DNA fragments that may have been transferred from the chloroplast genome, we downloaded the plastome of C. soulattri (Accession No. NC_068749) and compare it with the mitochondrial genome using BLAST in TBtools78 using the following parameters: e-value = , number of hits = 50000, and number of aligns = 25000. Then, we visualized the distribution of MTPTs using Circos plot implemented in TBtools79.

Analysis of RNA editing sites in the mitochondrial genome

We used Deepred-Mt80 in predicting C-to-U RNA editing based on the convolutional neural network (CNN) model. All protein-coding genes of C. soulattri were extracted from the mitochondrial genome and used for prediction. Results with probability values greater than 0.9 were selected for analysis.

Phylogenetic analyses

We retrieved the mitochondrial genomes of 14 closely related species and two non-Malpighiales species on NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) nucleotide database. A total of 26 protein-coding genes that are present in all these mitochondrial genomes were identified and extracted using PhyloSuite v1.2.374. Then, the sequences of each gene were aligned using MAFFT v7.47181 and concatenated into a data matrix. Subsequently, ModelFinder82 was used to find the best-fit substitution model and best partitioning scheme. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI). The ML tree was constructed using IQ-TREE v2.2.083. Furthermore, the Shimodaira-Hasegawa-like approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT)84 with 1000 replicates and ultrafast bootstrap (UFBoot)85 with 5000 replicates were used to assess clade support. The BI phylogenetic analysis was performed using MrBayes v3.2.7a86 with two independent runs using four MCMC chains. The trees were sampled every 1000 generations for 10,000,000 generations. Finally, all results were uploaded to iTOL viewer (https://www.itol.embl.de/)87 for editing and tree visualization.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has obtained permission to collect C. soulattri through the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR BMB Gratuitous Permit No. 299, 2019). We also conducted the study in accordance with relevant institutional, national and international guidelines and legislation.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the grants from the Department of Science and Technology - Philippine Council for Industry, Energy and Emerging Technology Research and Development (DOST-PCIEERD-GIA-04339). This research was carried out in part using DOST-Advanced Science and Technology Institute’s Computing and Archiving Research Environment (COARE). We would also like to acknowledge Jingling Li for the bioinformatics analysis support.

Author contributions

C.A.C. and J.R. designed the study; D.P. conducted the experiment and prepared Fig. 3; C.A.C. assembled, annotated, and analyzed the mitochondrial genome; C.A.C prepared the manuscript; J.R. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The complete mitochondrial genome sequence data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GenBank of NCBI database at (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the accession number OQ721861/NC_079842. The associated BioProject, SRA, and BioSample numbers are PRJNA891016, SRR22031315-SRR24822418, and SAMN31427486, respectively.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-55016-6.

References

- 1.Group et al. An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: Apg IV. Bot. J. Linnean Soc.181, 1–20 (2016).

- 2.Fajriaty I, et al. In vivo pharmacodynamics of Calophyllum soulattri as antiobesity with in silico molecular docking and ADME/pharmacokinetic prediction studies. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16:191. doi: 10.3390/ph16020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta, S. & Gupta, P. The genus Calophyllum: review of ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Bioactive Natural Prod. Drug Discovery 215–242 (2020).

- 4.Lim, C.-K., Hemaroopini, S., Say, Y.-H. & Jong, V. Y.-M. Cytotoxic compounds from the stem bark of Calophyllum soulattri. Natural Product Commun.12, 1934578X1701200922 (2017).

- 5.Mah SH, et al. Phylattrin, a new cytotoxic xanthone from Calophyllum soulattri. Molecules. 2012;17:8303–8311. doi: 10.3390/molecules17078303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Møller IM, Rasmusson AG, Van Aken O. Plant mitochondria-past, present and future. Plant J. 2021;108:912–959. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McBride HM, Neuspiel M, Wasiak S. Mitochondria: More than just a powerhouse. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:R551–R560. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spinelli JB, Haigis MC. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018;20:745–754. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. Mitochondrial evolution. Science. 1999;283:1476–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zachar I, Szathmáry E. Breath-giving cooperation: Critical review of origin of mitochondria hypotheses: Major unanswered questions point to the importance of early ecology. Biol. Direct. 2017;12:1–26. doi: 10.1186/s13062-017-0190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skippington E, Barkman TJ, Rice DW, Palmer JD. Miniaturized mitogenome of the parasitic plant Viscum scurruloideum is extremely divergent and dynamic and has lost all nad genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:E3515–E3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504491112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Putintseva, Y. A. et al. Siberian larch (Larix sibirica Ledeb.) mitochondrial genome assembled using both short and long nucleotide sequence reads is currently the largest known mitogenome. BMC Genomics21, 1–12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Kozik A, et al. The alternative reality of plant mitochondrial DNA: One ring does not rule them all. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1008373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobrogojski J, Adamiec M, Luciński R. The chloroplast genome: A review. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2020;42:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11738-020-03089-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pahayo, D. G., Cadorna, C. A. E., Quimado, M. O. & Rey, J. D. The complete chloroplast genome of Calophyllum soulattri Burm. f. (Calophyllaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B8, 607–611 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Han F, Qu Y, Chen Y, Xu L, Bi C. Assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of Salix wilsonii using PacBio HiFi sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 2022;13:1031769. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1031769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Bai H, Zhang Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of a mangrove plant: Bruguiera sexangula. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2020;5:1852–1853. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1750990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang, J. & Wang, X.-A. The complete mitochondrial genome of a yellow passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims. f. flavicarpa Deg.) in china and phylogenetic relationships. Mitochondrial DNA Part B5, 1598–1600 (2020).

- 19.Bi C, et al. Deciphering the multi-chromosomal mitochondrial genome of Populus simonii. Front. Plant Sci. 2022;13:914635. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.914635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wee, C.-C. et al. Mitochondrial genome of Garcinia mangostana L. variety Mesta. Sci. Rep.12, 9480 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Zou Y, Zhu W, Sloan DB, Wu Z. Long-read sequencing characterizes mitochondrial and plastid genome variants in Arabidopsis msh1 mutants. Plant J. 2022;112:738–755. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H-O, et al. Assembly of the mitochondrial genome in the Campanulaceae family using Illumina low-coverage sequencing. Genes. 2018;9:383. doi: 10.3390/genes9080383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z-F, Cao H-L. The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Aquilaria sinensis. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2021;6:381–383. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1869609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niu, Y. et al. Assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of three Macadamia species (M. integrifolia, M. ternifolia and M. tetraphylla). PLoS One17, e0263545 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Oda K, et al. Gene organization deduced from the complete sequence of liverwort Marchantia polymorpha mitochondrial DNA: A primitive form of plant mitochondrial genome. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;223:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90708-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo W, Mower JP. Evolution of plant mitochondrial intron-encoded maturases: Frequent lineage-specific loss and recurrent intracellular transfer to the nucleus. J. Mol. Evol. 2013;77:43–54. doi: 10.1007/s00239-013-9579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerke P, et al. Towards a plant model for enigmatic U-to-C RNA editing: The organelle genomes, transcriptomes, editomes and candidate RNA editing factors in the hornwort Anthoceros agrestis. New Phytol. 2020;225:1974–1992. doi: 10.1111/nph.16297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukhopadhyay J, Hausner G. Organellar introns in fungi, algae, and plants. Cells. 2021;10:2001. doi: 10.3390/cells10082001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu R, Sun C, Liu Y, Zhou R. Shifts from cis-to trans-splicing of five mitochondrial introns in Tolypanthus maclurei. PeerJ. 2021;9:e12260. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vieira MLC, Santini L, Diniz AL, Munhoz CdF. Microsatellite markers: What they mean and why they are so useful. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2016;39:312–328. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2016-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X-C, Chen H, Yang D, Liu C. Diversity of mitochondrial plastid DNAs (MTPTs) in seed plants. Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 2018;29:635–642. doi: 10.1080/24701394.2017.1334772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bi C, Lu N, Xu Y, He C, Lu Z. Characterization and analysis of the mitochondrial genome of common bean ( Phaseolus vulgaris) by comparative genomic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3778. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang, Z. et al. De novo assembly of the complete mitochondrial genome of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam) revealed the existence of homologous conformations generated by the repeat-mediated recombination. BMC Plant Biol. 22, 285 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Cao P, Huang Y, Zong M, Xu Z. De novo assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of Chaenomeles speciosa (Sweet) Nakai revealed the existence of two structural isomers. Genes. 2023;14:526. doi: 10.3390/genes14020526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, et al. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Photinia serratifolia. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:770. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24327-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang B, Li J, Zhao Q, Liang Y, Yu J. Assembly of the complete mitochondrial genome of Chinese plum (Prunus salicina): Characterization of genome recombination and RNA editing sites. Genes. 2021;12:1970. doi: 10.3390/genes12121970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang H, et al. De novo hybrid assembly of the Salvia miltiorrhiza mitochondrial genome provides the first evidence of the multi-chromosomal mitochondrial DNA structure of Salvia species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:14267. doi: 10.3390/ijms232214267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang H, et al. Mitochondrial genome sequence of Salvia officinalis (Lamiales: Lamiaceae) suggests diverse genome structures in cogeneric species and finds the stop gain of genes through RNA editing events. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:5372. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X, et al. Assembly of the complete mitochondrial genome of Pereskia aculeata revealed that two pairs of repetitive elements mediated the recombination of the genome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:8366. doi: 10.3390/ijms24098366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang M, Ni Y, Li J, Liu C. Characterisation of the complete mitochondrial genome of Taraxacum mongolicum revealed five repeat-mediated recombinations. Plant Cell Rep. 2023;42:775–789. doi: 10.1007/s00299-023-02994-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J, et al. Assembly of the complete mitochondrial genome of an endemic plant, Scutellaria tsinyunensis, revealed the existence of two conformations generated by a repeat-mediated recombination. Planta. 2021;254:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00425-021-03684-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of okra ( Abelmoschus esculentus): Using nanopore long reads to investigate gene transfer from chloroplast genomes and rearrangements of mitochondrial DNA molecules. BMC Genomics. 2022;23:481. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08706-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marienfeld J, Unseld M, Brennicke A. The mitochondrial genome of Arabidopsis is composed of both native and immigrant information. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:495–502. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(99)01502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makarenko MS, Omelchenko DO, Usatov AV, Gavrilova VA. The insights into mitochondrial genomes of sunflowers. Plants. 2021;10:1774. doi: 10.3390/plants10091774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu Y, Zhang F, Hu K. The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of an annual wild tobacco Nicotiana attenuata. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2017;2:924–925. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2017.1407686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams KL, Qiu Y-L, Stoutemyer M, Palmer JD. Punctuated evolution of mitochondrial gene content: High and variable rates of mitochondrial gene loss and transfer to the nucleus during angiosperm evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:9905–9912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042694899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams KL, Palmer JD. Evolution of mitochondrial gene content: Gene loss and transfer to the nucleus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;29:380–395. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cui H, et al. Comparative analysis of nuclear, chloroplast, and mitochondrial genomes of watermelon and melon provides evidence of gene transfer. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:1595. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang H, et al. Insights into molecular structure, genome evolution and phylogenetic implication through mitochondrial genome sequence of Gleditsia sinensis. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:14850. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93480-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ala KG, Zhao Z, Ni L, Wang Z. Comparative analysis of mitochondrial genomes of two alpine medicinal plants of Gentiana (Gentianaceae) PLoS ONE. 2023;18:e0281134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0281134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu C, Gao L-Z, Zhang Q-J. A high-quality genome assembly of the mitochondrial genome of the oil-tea tree Camellia gigantocarpa (Theaceae) Diversity. 2022;14:850. doi: 10.3390/d14100850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ni Y, et al. Comparative analysis of the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of Saposhnikovia divaricata revealed the possible transfer of plastome repeat regions into the mitogenome. BMC Genomics. 2022;23:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08821-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yue J, Lu Q, Ni Y, Chen P, Liu C. Comparative analysis of the plastid and mitochondrial genomes of Artemisia giraldii Pamp. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:13931. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-18387-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niu Y, et al. Analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of the bitter gourd ( Momordica charantia) Plants. 2023;12:1686. doi: 10.3390/plants12081686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang D, et al. Transfer of chloroplast genomic dna to mitochondrial genome occurred at least 300 MYA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:2040–2048. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Filip E, Skuza L. Horizontal gene transfer involving chloroplasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:4484. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hao W, et al. RNA editing and its roles in plant organelles. Front. Genet. 2021;12:757109. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.757109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Small ID, Schallenberg-Rüdinger M, Takenaka M, Mireau H, Ostersetzer-Biran O. Plant organellar RNA editing: What 30 years of research has revealed. Plant J. 2020;101:1040–1056. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Binder S, Brennicke A. Gene expression in plant mitochondria: Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2003;358:181–189. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ichinose M, Sugita M. RNA editing and its molecular mechanism in plant organelles. Genes. 2016;8:5. doi: 10.3390/genes8010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takenaka M, Verbitskiy D, van der Merwe JA, Zehrmann A, Brennicke A. The process of RNA editing in plant mitochondria. Mitochondrion. 2008;8:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hurst LD. The Ka/Ks ratio: Diagnosing the form of sequence evolution. Trends Genet. 2002;18:486–487. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02722-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chaux F, et al. Chloroplast ATP synthase biogenesis requires peripheral stalk subunits AtpF and ATPG and stabilization of atpE mRNA by OPR protein MDE1. Plant J. 2023;116:1582–1599. doi: 10.1111/tpj.16448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zancani M, Braidot E, Filippi A, Lippe G. Structural and functional properties of plant mitochondrial F-ATP synthase. Mitochondrion. 2020;53:178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Faivre-Nitschke SE, Nazoa P, Gualberto JM, Grienenberger JM, Bonnard G. Wheat mitochondria ccmb encodes the membrane domain of a putative ABC transporter involved in cytochrome c biogenesis. Biochim. et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Struct. Express. 2001;1519:199–208. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(01)00239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verrier PJ, et al. Plant ABC proteins-a unified nomenclature and updated inventory. Trends in Plant Sci. 2008;13:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palmer JD, et al. Dynamic evolution of plant mitochondrial genomes: Mobile genes and introns and highly variable mutation rates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:6960–6966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.6960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xi Z, et al. Phylogenomics and a posteriori data partitioning resolve the Cretaceous angiosperm radiation Malpighiales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:17519–17524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205818109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jin J-J, et al. Getorganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020;21:1–31. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. NOVOPlasty: De novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e18–e18. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wick RR, Schultz MB, Zobel J, Holt KE. Bandage: Interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3350–3352. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dunn NA, et al. Apollo: Democratizing genome annotation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019;15:e1006790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Greiner S, Lehwark P, Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3. 1: Expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W59–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xiang, C.-Y. et al. Using Phylosuite for molecular phylogeny and tree-based analyses. iMeta2, e87 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Yu J. KaKs\_Calculator 2.0: A toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinform. 2010;8:77–80. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(10)60008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beier S, Thiel T, Münch T, Scholz U, Mascher M. MISA-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kurtz S, et al. REPuter: The manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen C, et al. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant. 2020;13:1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen C, Wu Y, Xia R. A painless way to customize Circos plot: From data preparation to visualization using TBtools. iMeta. 2022;1:e35. doi: 10.1002/imt2.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Edera AA, Small I, Milone DH, Sanchez-Puerta MV. Deepred-Mt: Deep representation learning for predicting C-to-U RNA editing in plant mitochondria. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;136:104682. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K-I, Miyata T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TK, Von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Anisimova M, Gascuel O. Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: A fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Syst. Biol. 2006;55:539–552. doi: 10.1080/10635150600755453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Minh BQ, Nguyen MAT, Von Haeseler A. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:1188–1195. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The complete mitochondrial genome sequence data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GenBank of NCBI database at (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the accession number OQ721861/NC_079842. The associated BioProject, SRA, and BioSample numbers are PRJNA891016, SRR22031315-SRR24822418, and SAMN31427486, respectively.