Abstract

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder diagnosed mainly in children, marked by inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity. The symptoms are highly variable, such as different ages of onset and potential comorbidities, contributing to frequent misdiagnoses. Professionals note a gap in modern diagnostic tools, making accurate identification challenging. To address this, recent studies recommend gamification for better ADHD diagnosis and treatment, though further research is essential to confirm its efficacy. This work aims to create a serious game, namely “Attention Slackline", to assess attention levels. The game, designed with expert input, requires players to concentrate on a specific point to recognize specific patterns while managing distractions. A controlled experiment tested its precision, and results were compared with established attention tests by a correlation analysis. Statistical analysis confirmed the game's validity, especially in tracking attention through correct responses and errors. Preliminary evidence suggests that “Attention Slackline" may serve as a credible instrument for the assessment of attentional capacities in individuals with ADHD, given that its outcomes have been empirically shown to correlate with those derived from a well-established attention assessment methodology.

Keywords: ADHD, Serious game, Attention, Assessment, Neuropsychology, Experiment, Children

Highlights

-

•

A computer game for measuring attention (ADHD) has been developed.

-

•

The game measures users' attention while gathering biometrical data.

-

•

The game has been empirically evaluated through a controlled experiment.

-

•

36 ADHD-affected children and 44 neurotypical ones participated in the evaluation.

-

•

There is a positive correlation between the game and a widely used attention test.

1. Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is defined as a neurodevelopmental disorder, which can be present from before the age of 12, characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that can be maladaptive and interfere with the patient's daily functioning [1,2]. According to the data reported by the American Psychological Association [1] ADHD could be present in between 4% and 13.3% of children and adolescents worldwide, depending on the assessment protocol and the number of informants involved in the diagnostic process [2,3] Specifically, a meta-analysis carried out in Spain estimates its prevalence to be 6.8% [4]. In relation to gender, recent studies have affirmed that, although ADHD seems to be more frequent in males in the general population, females are more likely to present inattentive traits [1].

According to these data, ADHD is a disorder with a high prevalence in the childhood and adolescent population, presenting significant difficulties associated with inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, emotional problems and cognitive deficits [5,6]. This disorder represents one of the most common reasons for children with conduct problems [5]. However, children with ADHD represent a population with a very heterogeneous range of symptoms, in age of onset, and also in comorbidity with other disorders [5]. There are three main types of ADHD: (1) a combined type, where both inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity criteria should be met; (2) predominant inattentive type, where only inattention criteria are met; and (3) predominant hyperactive/impulsive type, where only hyperactivity-impulsivity criteria are met [1].

Beyond the characteristic symptoms of ADHD, it has a negative impact on the quality of life of patients and their families [7]. In fact, recent research has shown a significant correlation between the presence of greater severity of ADHD symptoms and poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [7,8]. Recent studies show that there is a lower HRQoL, both overall and in its different dimensions, in the group of children with ADHD compared to the control group of healthy children, concluding that ADHD seriously compromises the quality of life of children who suffer from it. In this sense, children with a diagnosis of ADHD may suffer a significant deterioration in psychological, social and academic well-being. Therefore, based on these results, it is a public health problem of great magnitude given its high prevalence, as well as the comorbidity to which it may be associated and its chronicity.

In relation to the diagnosis of ADHD, it is essential to have assessment instruments that allow an appropriate differential diagnosis to be made due to the subjectivity of the symptoms reported by families and teachers, as well as the possible overlap of diagnostic criteria for other attentional and behavioral disorders [1,9] In this sense, neuropsychological assessment tests are a step forward as they are designed to report valid and reliable data to enable an appropriate diagnosis of individual patients [10,11]. Numerous studies have reported the development of standardized neuropsychological batteries that have been used in daily clinical practice in recent years and have been a turning point in the assessment and clinical diagnosis of ADHD. These neuropsychological batteries also allow for greater precision in the description of the cognitive deficits that may appear in children with ADHD, and thus provide support for decision-making in clinical treatment [11,12].

Another tool to support the diagnosis of ADHD is eye-tracking. This assessment technique can provide additional information on brain functioning, providing reliable information on higher-order processes such as learning, memory and attention [13]. Eye-tracking systems are shown to be versatile and can be applied in short sessions [14]. Several studies indicate that people with ADHD present greater difficulties in gaze fixation, as well as greater saccadic movements [15]. They also show longer reaction times and more errors in the direction of antisaccadic movements compared to the non-clinical population [13].

With the aforementioned in mind, the main goal of this work is to develop a new game able to measure users' attention while gathering additional biometrical data such as eye tracking data or electrodermal activity. Moreover, this game has been empirically evaluated, thus demonstrating that its users’ attention results can correlate with a widely used paper-and-pencil-based attention test. It is worth noting that, even though this tool has originally been designed to measure attention an ADHD-affected children and teenagers, it can be applied to neurotypical ones, as well as to other subjects suffering from different pathologies where attention is impaired, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. After this introduction, Section 2 summarizes the main related work. Next, Section 3 presents Attention Slackline, our proposal to measure users’ attentions though a computer game. After that, Section 4 presents the experiments used to evaluate the game. Finally, Section 5 ended this work by presenting out conclusions and further works.

2. Related works

To start with, computer game technologies have been utilized not only to identify the neuropsychological profile of children with ADHD but also for their treatment and rehabilitation. Such interventions have shown significant advantages over more traditional methodologies, reducing costs and time for diagnosis [16,17].

These tools enable the recreation of various real-world stimuli using an ecological approach and allow for the flexible customization of visual and auditory stimuli in a virtual environment, such as controlling the time, order, and type of stimuli [17]. The use of computer games has been validated as a reliable method for detecting cognitive functioning impairments [18].

Recent developments in the field have expanded the scope of these tools to include games that employ music and rhythm, which have been gaining attention for their therapeutic potential. In Ref. [19] authors provide a systematic review of the effects of music on ADHD and discuss the prospective application in serious video games. Their findings suggest that incorporating musical elements can enhance attention and engagement, which is a promising direction for the development of new therapeutic strategies for ADHD.

In addition, over the last few years, several investigations have been developed to evaluate the validity and reliability of gamified cognitive assessments for ADHD patients [[20], [21], [22]]. In this regard, as corroborated by a recent systematic review, some serious video games have exhibited higher rates of reliability and accuracy in the evaluation of characteristics of ADHD [21,23] However, most of them have been developed to be applied as an intervention to improve ADHD symptoms [21]. In this regard, little is known about gamified tools oriented to diagnosis. Regarding those developed for rehabilitation, some recent research has shown the effectiveness of serious games [24,25]. A recent study conducted by Ref. [25], tested the tool IAmHero, a serious game in which the patient is immersed in several scenarios through virtual reality and should develop several activities following diverse instructions. Authors applied the intervention in a cohort of children with ADHD for approximately 6 months, showing improvements in both ADHD symptoms and executive functioning [25]. Hence, a recent systematic review and metanalysis has demonstrated large effect sizes in favor of VR-based interventions on cognitive functioning, mainly in the case of attention and memory domains [24]. Other tools have also been developed specifically for the improvement of other core domains of ADHD symptoms, such as the Alfi program for the improvement of inhibitory control [26] or the Biofeedback Game DEEP for anxiety and disruptive behavior reduction [27].

In the case of ADHD symptoms assessment, some studies have been recently developed, such as those conducted by Ref. [28,29]. The research carried out by Ref. [28] employed a gamified task, called EPELI (Executive Performance in Everyday LIving), which reproduced an apartment in which the patient should develop several daily life scenarios. The tool was administered to 38 ADHD children and 38 typically developing controls. Obtained results showed higher concurrent and discriminant validity of the tool, demonstrating its accuracy in the evaluation of ADHD symptoms in children [28]. Furthermore, in another study in which the same tool was applied, the evaluation of eye movement pattern was also revealed as a significant variable for discrimination of ADHD symptoms, demonstrating that the combination of a computer game and eye movement could be employed for precise prediction of attention deficits [29]. Previously conducted research obtained similar results, demonstrating that computer games especially those replicate ecological contexts, could be useful for the evaluation of ADHD symptomatology [30,31]. In this sense, the AULA Nesplora, a virtual environment which replicates a school classroom, exhibited higher convergent validity when compared with standardized cognitive evaluation tools [30,32].

Although some recent studies are starting to show the benefits of this type of gamification for ADHD rehabilitation, the research is scarce and more studies are needed to evaluate the reliability and validity of serious games in the assessment and diagnosis of ADHD patients, both in behavioral and cognitive domains. One of the main reasons for the lack of VR-based tools for the diagnosis of ADHD is that the gathered data throughout the gaming have to be treated with modern Deep Learning solutions that allow us to have systems that automatically classifies a child with ADHD or not according with the obtained results. Thus, in a preliminary systematic review [33], we showed that there is an increasing interest in the use of these solutions in the diagnosis of ADHD. We should point out at this time that the work presented in this paper is part of the BALLADEER project, a project that aims to help professionals in the diagnosis of ADHD by using game-based tools and Deep Learning architectures that could enable us to achieve automatic ADHD classification [34].

3. Attention Slackline

In order to measure the attention level of children diagnosed with ADHD, or those who might be affected with such pathology, we started creating the Attention game series. These games have the goal of helping psychologists to diagnose children with ADHD, as well as serving as a tool to assess their evolution, by offering a gamified experience much more enjoyable than the current paper-and-pencil-based assessments. In addition to the core gameplay mechanics, the ‘Attention Slackline' series is equipped to integrate a suite of devices capable of capturing various biometric data from the player, including brain activity, electrodermal activity, heart rate, and gaze patterns. While this rich dataset is not utilized in the analyses presented within this current work, it is being meticulously recorded and will serve as a foundational resource for subsequent studies. The intent is to leverage this biometric data in future research to assist psychologists in the identification of potential ADHD patients and in monitoring the progression or improvement of those already diagnosed.

In this particular work, we are presenting Attention Slackline, being this game the first one of the Attention series. First of all, it should be noted that the game has been developed under the supervision of a group of researchers and clinicians with expertise in neuropsychology.

As far as the storytelling is concerned, the game is set in a snowy valley. Hence, the player's goal is to rescue a friend who is isolated on a far mounting (where the orange flag is placed). To do so, the character has to use a slackline to walk from the mountain where he/she (the character has no defined genre) is located towards the opposite mountain where the friend is as fast as possible. It is worth noting that in the storytelling, there was no reference to hazardous facts in order to make the game as children friendly as possible. Indeed, the character will never fall from the slackline.

3.1. Game mechanics

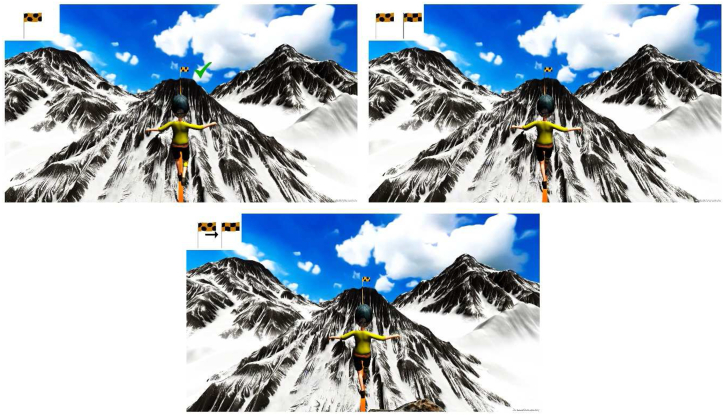

As it can be observed in Fig. 1, the player will always see in the top-left corner of the screen a target flag with a specific pattern. Besides, in the mountain far away, where the friend is supposed to be, several flags will also appear.

Fig. 1.

On the left, a player walking fast after selecting the correct flag. On the right, a player walking slowly after selecting an incorrect flag.

Therefore, the player has to press a button when the two flags have the same pattern. If this is done successfully, the character will walk. However, if the button is pressed when two different flags are shown, the character will walk slower. Each game level lasts for 5 min, and at the end, the player receives a motivational message. It should be noted that the message will always be positive, even if the game's outcome is not favorable.

3.2. Game blocks and levels

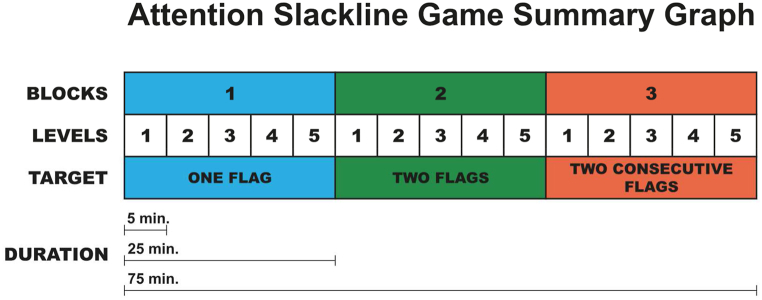

The game “Attention Slackline" is structured into three distinct blocks, each containing five levels of increasing complexity. The player is tasked with observing and responding to visual stimuli in the form of flags, which are critical to the game mechanics. This structure is summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Blocks, Levels, Target and duration of Attention Slackline Game.

Block 1 is designed to establish the fundamental task of pattern recognition. Displayed prominently in the top-left corner of the screen is a target flag bearing a unique pattern. Simultaneously, an array of flags is presented on a distant mountain within the game environment. The player's objective is to identify and match the single target flag with its counterpart among the flags on the mountain.

In Block 2, the task's complexity is elevated as the player is required to concurrently track two distinct target flags. These flags are displayed in the top-left corner, and the player is required to execute a response whenever either of the target flags appears on the distant mountain. This block tests the player's ability to divide their attention and respond to multiple stimuli.

Block 3, the concluding segment of the game, incorporates a sequential pattern recognition task, heightening the cognitive demand of the exercise. The player is now presented with a sequence of two target flags, which must be identified in the correct order among the flags on the mountain. A correct response is registered when the player presses the button following the appearance of the second flag in the sequence, indicating the successful completion of the sequence recognition. This block is designed to assess the player's working memory and sequential processing abilities. The flag position and mechanics of the three blocks is depicted in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Flags in Block 1 top-left, Block 2 top-right and Block 3 bottom.

As delineated previously, the game ‘Attention Slackline' is segmented into three blocks, each comprising five ascending levels of difficulty. The gradation between the levels within each block is systematically determined by the incremental introduction of distractors into the game environment. These distractors are specifically designed to divert the player's focus away from the target flags. A diverse array of distractors is employed, including visual stimuli such as flares, helicopters, planes, skydivers, and birds, as well as dynamic environmental factors like climatological variations and changes in the diurnal cycle, exemplified by a sunset (depicted in Fig. 4). Progression through the levels is characterized by a quantitative increase in the presence of distractors, commencing with a distractor-free environment at the first level and culminating in a highly distracting setting at the pinnacle level of each block.

Fig. 4.

Level 5 of the game showing a distractor (plane).

Owing to the potentially intricate nature of the game mechanics, an interactive tutorial is provided at the commencement of each level to facilitate player comprehension. Tailored to the specific demands of the level, the tutorial elucidates the requisite interactions within the game. This is achieved through a combination of voiceover instruction, which articulates the game mechanics, and an accompanying demonstration video that visually represents these actions (as illustrated in Fig. 5). Subsequent to the tutorial, players are afforded the opportunity to engage in a practice session, reinforcing their understanding of the gameplay before embarking on the actual level. The tutorial remains accessible and can be replayed as needed to ensure players are fully equipped with the knowledge to proceed.

Fig. 5.

Screenshot of Attention Slackline tutorial.

Regarding the game results, we record events which include the following data.

-

•

Whether or not the player reacted to the appearance of a flag.

-

•

The reaction time between the appearance of a flag and pressing the button.

-

•

Whether or not the player pressed the button when the correct flag was shown.

-

•

The pattern of the shown flag.

-

•

The elapsed time from the beginning of the game when the event was recorded.

-

•

Whether or not the player was looking at the mountain flag (see next sub-section to see how eye-tracking works).

By analyzing these events, we can calculate the following psychological indicators related with the player's attention.

-

•

Hits: The number of flags the player has selected correctly. This indicator is usually related to selective and sustained attention.

-

•

Omissions: The number of flags the player has skipped without pressing the button. Indicator related to selective attention, since committing many omissions indicates less selective attention.

-

•

Commissions: The number of flags the player has selected wrongly. Indicator related to the response style, reflecting the player's impulsiveness. If someone is very impulsive, he/she tends to make a lot of commissions. It is also related to the attentional part, since if the player has many commissions, the level of attention is also compromised.

3.3. Software and Hardware architecture

With the aim of making the game able to gather data from different devices, the Software and Hardware architecture shown in Fig. 6 was implemented. It is worth noting that such architecture was defined in order to be used not only by the Slackline game, but also by all the current and future games of the Attention series. That is the reason why we have developed a backend which will be in charge of gathering and storing all the produced data, thus making this task independent of the game. Indeed, the backend will expose a stringboard RESTfull API can be called by any Attention game to start and stop gathering data, and to automatically store it at the end of this process.

Fig. 6.

Software and Hardware architecture of Attention Slackline.

4. Evaluation

In this section we are going to evaluate Attention Slackline in order to assess whether or not it is able to measure attention. With this aim, we are coping to compare it with D2, a gold-standard pen and pencil test to measure widely used by psychologists to measure attention [35]. Hence, this test will be explained in the following and, after that, the experiment that assesses if Attention Slackline results corelate with D2 will be presented. However, in order to better understand the test Attention Slackline will be correlated to, such D2 test will be presented in the following.

4.1. The D2 Test of Attention and test on perception of differences

The d2-r test [35,36] measured the capacity to selectively focus on certain relevant aspects in a task, while ignoring other irrelevant ones, and doing it so quickly and accurately as well in individuals aged from 6 to 80. The application of the test lasted between 8 and 10 min. It was composed of fourteen lines with 57 elements each. These lines contained “d” and “p”, which could appear with one of two little dashes above or below each letter. The individuals had to check all the lines carefully from left to right, and they had to mark every letter “d” showing two little dashes (both above, below, or one above and one below). The individuals had 20 s for each line. The resulting scores were: i) general answer (GA, the number of elements tried on the fourteen lines); ii) the number of correct guesses (CG, the number of correct relevant elements); iii) omitted elements (O); and iv) commissions (C). Then, some indexes could be also calculated: working speed, accuracy and concentration. This test showed good psychometric properties for its application through an internal consistency Cronbach's alpha of GA = 0.94, CG = 0.95, O = 0.94, C = 0.93 [36].

4.2. Experimental context

As stated before, the main goal of this section is to empirically evaluate Attention Slackline (AS) and D2 in order to assess whether there are correlations between its results when trying to measure attention. This was performed by means of a controlled experiment, whose main features can be shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main features of the experiment.

| Null hypotheses | H0A: Results of level 1 of Attention Slackline and D2 do not positively correlate when measuring attention according to the number of hits. |

| H1A: ¬H0A | |

| H0B: Results of level 1 of Attention Slackline and D2 do not positively correlate when measuring attention according to the number of omissions. | |

| H1B: ¬H0B | |

| H0C: Results of level 1 of Attention Slackline and D2 do not positively correlate when measuring attention according to the number of commissions. | |

| H1C: ¬H0C | |

| H0D: Results of level 6 of Attention Slackline and D2 do not positively correlate when measuring attention according to the number of hits. | |

| H1D: ¬H0D | |

| H0E: Results of level 6 of Attention Slackline and D2 do not positively correlate when measuring attention according to the number of omissions. | |

| H1E: ¬H0E | |

| H0F: Results of level 6 of Attention Slackline and D2 do not positively correlate when measuring attention according to the number of commissions. | |

| H1F: ¬H0F | |

| H0G: Results of level 11 of Attention Slackline and D2 do not positively correlate when measuring attention according to the number of hits. | |

| H1G: ¬H0G | |

| H0H: Results of level 11 of Attention Slackline and D2 do not positively correlate when measuring attention according to the number of omissions. | |

| H1H: ¬H0H | |

| H0I: Results of level 11 of Attention Slackline and D2 do not positively correlate when measuring attention according to the number of commissions. | |

| H1I: ¬H0I | |

| Dependent variable | Number of hits, omissions and commissions |

| Independent variable | The used attention measurement test, namely D2, Level 1 of Attention Slackline (AS1), Level 6 of Attention Slackline (AS6) and Level 11 of Attention Slackline (AS11) |

| Location | University Institute for Computing Research (Alicante, Spain) |

| Date | From June 2022 to July 2023 |

| Subjects | 80 6-to-18-year-old children and teenagers divided into 2 groups:

|

As indicated in Table 1, the study encompassed a sample of 80 juvenile participants, comprising both children and adolescents. The age distribution of these subjects spanned from 6 to 18 years, with a mean age of 13 years. The gender composition of the sample was 51 males and 29 females. Furthermore, as it can be seen in Table 1, there was 36 ADHD-affected children and 44 Neurotypical children. For those underage participants, we asked for their parents’ permissions prior to their participation. Moreover, this experiment was approved by the ethical committee of the Alicante Institute for Health and Biomedical Research (ISABIAL).

4.3. Experimental design

As far as the design of the experiment is concerned, the participants performed the different parts of it this order.

-

•

D2 (15 min)

-

•

Attention Slackline level 1 (5 min)

-

•

Attention Slackline level 6 (5 min)

-

•

Attention Slackline level 11 (5 min)

It is worth noting that, before performing this experiment, the participants (or their parents in the event the participant was underaged) signed a consent form. Moreover, each participant passed a psychological assessment test in order to identify possible subjects unable to perform the experiment.

4.4. Conducting the experiment

During the experimental session, each participant was accompanied by at least one psychologist and a computer technician. During these sessions, the participants performed the D2 test in a table by using pencil and paper and, after that, they played the three different levels of AS in a high-end gaming computer. Moreover, the AS sessions were conducted while wearing the EEG headset and the EDA/HR wristband (see Fig. 7) in order to retrieve biometrical data that will be valuable in the near future.

Fig. 7.

Participant playing Attention Slackline during the experiment.

It should be highlighted that there were no notorious incidents during the experimental sessions, except for a few younger participants who complained about wearing the EEG headset. In these cases, it was decided to remove this device from the participants and keep on doing the session without gathering EEG data. The data from these particular experiments were specially marked to facilitate their identification during the training of our Deep Learning models for medium-term research.

4.5. Experiment results

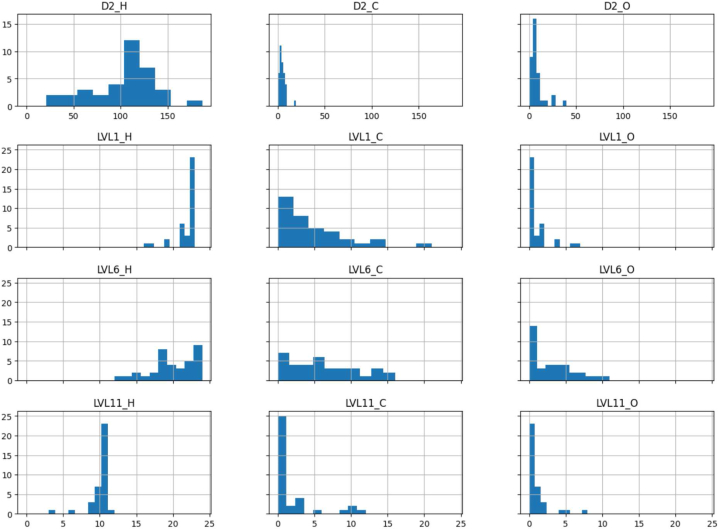

In Table 2, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, the summary of the experiment results in presented. Note that in the following we can see the obtained results for.

-

•

Hits (H): Registered when the user did the task successfully (crossing the right symbol in D2 or pressed the button when the right flag appeared in AS)

-

•

Omissions (O): Registered when the user did not do the task (skipped a symbol in D2 or not pressed the button when the right flag appeared in AS)

-

•

Commissions (C): Registered when the user did the task unsuccessfully (crossed the wrong symbol in D2 of not pressed the button when the wrong flag appeared in AS)

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for D2 and Attention Slackline experiments.

| test |

D2 |

AS1 |

AS6 |

AS11 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| var | H | O | C | H | O | C | H | O | C | H | O | C |

| Group 1 (ADHD) | ||||||||||||

| count | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| mean | 104.36 | 7.75 | 4.31 | 22.00 | 1.00 | 5.06 | 19.89 | 3.14 | 6.22 | 10.31 | 0.83 | 1.94 |

| std | 34.78 | 8.32 | 3.66 | 1.76 | 1.76 | 4.72 | 2.98 | 2.92 | 4.58 | 1.62 | 1.68 | 3.23 |

| min | 21 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 25% | 93 | 3.5 | 2 | 21 | 0 | 2 | 18 | 0.75 | 2.75 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 50% | 108 | 6 | 4 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 75% | 125 | 9.25 | 6 | 23 | 2 | 7.25 | 22.25 | 5 | 8.5 | 11 | 1 | 2.25 |

| max | 187 | 40 | 19 | 23 | 7 | 21 | 24 | 11 | 16 | 12 | 8 | 12 |

| Group 2 (Neurotypical) | ||||||||||||

| count | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 |

| mean | 130.34 | 9.41 | 3.25 | 22.73 | 0.30 | 2.02 | 20.48 | 2.57 | 4.61 | 10.23 | 0.75 | 0.93 |

| std | 49.96 | 8.33 | 3.23 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 2.07 | 2.52 | 2.45 | 4.52 | 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.07 |

| min | 24 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 25% | 97.75 | 4.75 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 1.75 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 50% | 130.5 | 8 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 21 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 75% | 168.25 | 11 | 5 | 23 | 0 | 3.25 | 23 | 4 | 5.25 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| max | 239 | 41 | 16 | 24 | 4 | 8 | 24 | 9 | 23 | 12 | 4 | 4 |

| Groups 1 + 2 (Whole experimental population) | ||||||||||||

| count | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| mean | 118.65 | 8.66 | 3.73 | 22.40 | 0.61 | 3.39 | 20.21 | 2.83 | 5.34 | 10.26 | 0.79 | 1.39 |

| std | 45.43 | 8.31 | 3.45 | 1.35 | 1.34 | 3.81 | 2.74 | 2.67 | 4.59 | 1.36 | 1.38 | 2.35 |

| min | 21 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 25% | 94 | 4 | 1 | 22 | 0 | 1 | 19 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 50% | 117 | 6.5 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 20.5 | 2.5 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 75% | 148.25 | 11 | 5 | 23 | 1 | 5 | 23 | 4 | 7.25 | 11 | 1 | 2 |

| max | 239 | 41 | 19 | 24 | 7 | 21 | 24 | 11 | 23 | 12 | 8 | 12 |

Fig. 8.

Histograms for D2 and attention slackline for group 1 (ADHD).

Fig. 9.

Histograms for D2 and attention slackline for group 2 (neurotypical).

Fig. 10.

Histograms for D2 and attention slackline for groups 1 + 2.

It is worth noting that the row “count” in Table 2, refers to the number of participants in each group. Moreover, when dealing with results from AS, the level the results come from will appear together with AS (AS1 for level 1, AS6 for level 6 and AS11 for level 11). Besides, in Figs. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, we can see the number of registered variables (hits, omissions and commissions) in the x-axis and the number of subjects in the y-axis. It is significant to observe that the full set of experimental results by subject can be seen in Table 4 from the Annex.

Just by examining the results, it can be observed that the scores from the D2 are considerably higher than those from the AS. This is expected, as the D2 involves a greater number of tasks compared to the AS. More specifically, the participants can deal with a total of 658 symbols in D2 and 24, 24 and 12 flags in levels 1, 6 and 11 from AS respectively. Indeed, this is the reason why the results from AS1 and AS6 are nearly double those from AS11. In the latter, users have to wait until they see a succession of two different flags, which reduces the total number of tasks to half compared to AS1 and AS6, where users can press the button after seeing just one flag.

4.6. Analysis of the results

One the results have been presented, they will be properly analyzed in order to accept or reject our initial hypotheses. Note that all the statistical analysis in this work has been performed by using the SciPy 1.11.1 [37] and Pandas 2.0.3 [38] Python libraries.

First at all, a correlation matrix was created in order to graphically find out the correlation among the dependent variables in the experiment. At first glance, we can see the most notorious result, that is the inverse correlation between hists and omissions within the same test. Beyond these trivial results, we can perceive that there is a positive correlation among the number of hits of the different tests. However, these correlations are not always that positive (indeed it can be even negative) among omissions and commissions. Therefore, in order to obtain more reliable results, a Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) will be calculated for different pair of variables to analytically compare the correlation among D2 and the different levels of AS regarding hits, omissions and commissions.

Table 3 presents the outcomes of the Pearson Correlation Coefficient analysis. This table delineates both the Pearson's r values and the associated p-values for each correlation examined. To enhance clarity and facilitate interpretation, the columns displaying the Pearson's r values are color-coded to reflect the magnitude of the correlations. Concurrently, the columns representing p-values are dichotomously colored, with green indicating statistically significant results.

Table 3.

Results for Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r).

In the case of Group 1, comprising individuals affected by ADHD, the analysis revealed that AS1 exhibited statistically significant positive correlations across all three dependent variables. Additionally, AS6 demonstrated positive correlations. However, it is noteworthy that the correlation pertaining to the number of commissions in AS6 did not reach statistical significance. Lastly, for AS11, while statistically significant positive correlations were observed for hits and commissions, a negative correlation was identified for omissions, although this correlation did not achieve statistical significance.

Regarding Group 2, which consisted of neurotypical subjects, AS1 and AS11 both exhibited statistically significant positive correlations for hits and commissions. Notably, the correlations observed in AS1 were more pronounced than those in AS11. However, in both activity sets, despite a positive correlation for omissions, the results did not attain statistical significance. In contrast, Activity Set 6 (AS6) yielded distinct outcomes, displaying positive correlations across all three dependent variables. Nonetheless, the p-value associated with hits in AS6 was such that the result did not meet the threshold for statistical significance.

Upon aggregating the data from both experimental groups, it becomes evident that AS1 and AS6 manifested notably positive correlations across all dependent variables, achieving statistical significance with p-values less than 0.0033. In contrast, the outcomes associated with Activity Set 11 (AS11) were less favorable. This set demonstrated a marginally negative correlation for omissions. However, this correlation did not reach the threshold for statistical significance.

Considering these findings, we are positioned to reject the null hypotheses H0A, H0B, H0C, H0D, H0E and H0F. This implies that the results from levels 1 and 6 of AS and D2 exhibit a positive correlation in the measurement of attention, as assessed by the number of hits, omissions, and commissions, with a 95% confidence level. Conversely, in the context of AS11, it is only feasible to reject null hypotheses H0F and H0H. This denotes that level 11 of AS and D2 positively correlate in gauging attention, but solely in terms of the number of hits and commissions, maintaining a 95% confidence level. However, based on these outcomes, we cannot endorse level 11 of AS11 as a reliable tool for measuring omissions.

4.7. Threats to the experimental validity

Next, the different threats to the validity of the experiment will be analyzed. Particularly, the four types of threats proposed by Ref. [39], namely conclusion, internal, external, and construct validity will be considered.

The threats to conclusion validity are factors that can lead to an incorrect conclusion about the observations. Eight out of our nine null hypotheses were contrasted by using Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) that indicated statistically significant p-values (at alpha = 0.05). Therefore, they supported the contrast of our initial hypotheses with enough degree of certainty.

Threats to internal validity are focused on the design of the study. More specifically, they are related to whether or not the results really do follow from the data. The first analyzed threat to the internal validity was instrumentation since erroneously designed instruments could affect the results of the experiment. Aimed at mitigating this threat, the development of the game and the definition of the experiment were constantly supervised by a team of researchers and clinicians with expertise in neuropsychology. Moreover, the experiment was approved by the ethical committee of the Alicante Institute for Health and Biomedical Research (ISABIAL) before performing it. Second, mortality occurs when participants drop out of the experiment. In our study, we attempted to mitigate this threat by scheduling the subjects' participation according to their availability. As a result, no participants dropped out of the experiment.

The threats to construct validity represent the extent to which the experiment settings or the measures chosen to reflect the construct under study. Therefore, in this experiment we used the variables defined in D2, which is a widely and well-known used test to measure users’ attention in order to avoid this thread. Moreover, AS was properly tested by a team of game developers, as well as pilot tested before performing the experiment.

Threats to external validity relate to whether or not the claims for the generality of the results are justified. The experiment was performed with participants aged from 6 to 18 years old. Therefore, we cannot fully generalize the results to participants of all ages. However, we enrolled both neurotypical subjects and those affected by ADHD, and we differentiated between them in the experimental results.

5. Conclusion and further works

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) remains a complex neurodevelopmental disorder, primarily diagnosed during childhood, marked by enduring symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that can substantially disrupt daily life. The variability in symptom presentation, age of onset, and comorbidities with other disorders underscores the intricate nature of ADHD. Hence, the primary aim of this paper endeavor was to pioneer a modern serious game, Attention Slackline, specifically designed to quantify the attention levels of individuals with ADHD, while simultaneously creating an infrastructure for collecting biometric data. In the Attention Slackline game, we devised a method to measure a player's attention by assessing their ability to press a button when presented with a flag bearing a pattern matching the reference flag. Subsequently, we meticulously documented the occurrences of hits, commissions, and omissions, providing granular insights into attentional behavior.

In our pursuit of scientific rigor and validation, we subjected the Attention Slackline's attention measurement to rigorous statistical scrutiny. These analyses included a comparison with an established assessment, namely the D2 Test of Attention. Our findings, supported by a 95% confidence level, affirm the utility of Attention Slackline as a reliable tool for quantifying users' attention, particularly in terms of hits and commissions.

In conclusion, this research presents a significant step toward leveraging computer games for assessing and rehabilitating ADHD patients. Our novel approach, as embodied by the Attention Slackline, demonstrates promise and validity in quantifying attention, but the path forward involves further enhancements and optimizations to meet the multifaceted challenges posed by ADHD assessment. This study encourages ongoing exploration in this dynamic field, as we endeavor to refine and expand the toolkit for ADHD evaluation and intervention.

Regarding future works, our research highlights the need for continuous refinement and expansion. Specifically, we acknowledge the necessity of devising an alternative mechanism for capturing user omissions within the Attention Slackline. Despite the game's success in measuring attention in other dimensions, we observed no significant positive correlation with D2 Test of Attention omissions in our experimental results for the level 11 of AS. Additionally, further experimentation will be performed in order to assess AS with users from a different age range (higher than 18 years old), as well as differentiating between neurotypicals and ADHD-affected ones. In long-term research, by using the biometrical data obtained during the experiment, several Deep Learning models will be created in order to classify the level of affection of the participants.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Miguel A. Teruel: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Javier Sanchis: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Nicolás Ruiz-Robledillo: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Data curation. Natalia Albaladejo-Blázquez: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Data curation. Rosario Ferrer-Cascales: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Juan Trujillo: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work has been co-funded by the BALLADEER (PROMETEO/2021/088) project, a Big Data analytical plat-form for the diagnosis and treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) featuring extended reality, funded by the ,Conselleria de Innovación, Universidades Ciencia y Sociedad Digital (Generalitat Valenciana), Grant RED2022-134656-T funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and Program for the Promotion of R + D + I (UAIND20-03B) by Vicerrectorado de Investigación y Transferencia de Conocimiento de la Universidad de Alicante, and by the AETHER-UA project (PID2020-112540RB-C43), a smart data holistic approach for context-aware data analytics: smarter machine learning for business modelling and analytics, funded by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

Contributor Information

Miguel A. Teruel, Email: materuel@dlsi.ua.es.

Javier Sanchis, Email: fjsanchis@dlsi.ua.es, sat@dissenymultimedia.com.

Nicolás Ruiz-Robledillo, Email: nicolas.ruiz@ua.es.

Natalia Albaladejo-Blázquez, Email: natalia.albaladejo@ua.es.

Rosario Ferrer-Cascales, Email: rosario.ferrer@ua.es.

Juan Trujillo, Email: jtrujillo@dlsi.ua.es.

Annex

Table 4.

Full set of experimental results by subject

| Group | Gender | Age | D2_H | D2_O | D2_C | AS1_H | AS1_O | AS1_C | AS6_H | AS6_O | AS6_C | AS11_H | AS11_O | AS11_C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 6 | 63 | 6 | 4 | 23 | 0 | 14 | 22 | 1 | 11 | 10 | 1 | 10 |

| 1 | M | 7 | 21 | 2 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 5 |

| 1 | M | 8 | 37 | 26 | 8 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | M | 9 | 79 | 6 | 7 | 23 | 0 | 8 | 18 | 5 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| 1 | M | 9 | 43 | 40 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 21 | 14 | 9 | 15 | 11 | 0 | 12 |

| 1 | M | 9 | 43 | 9 | 19 | 23 | 0 | 12 | 19 | 5 | 7 | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| 1 | M | 10 | 95 | 6 | 5 | 21 | 2 | 2 | 17 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 10 | 124 | 2 | 9 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 16 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 10 |

| 1 | M | 10 | 69 | 7 | 4 | 21 | 2 | 10 | 21 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | M | 10 | 105 | 11 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 5 | 19 | 4 | 14 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | M | 11 | 136 | 10 | 5 | 21 | 2 | 10 | 18 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | M | 11 | 129 | 10 | 2 | 19 | 4 | 7 | 20 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | M | 11 | 104 | 6 | 2 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 19 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 12 | 95 | 4 | 6 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 21 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 12 | 104 | 4 | 9 | 23 | 0 | 6 | 20 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 12 | 107 | 5 | 5 | 22 | 1 | 2 | 17 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| 1 | M | 12 | 101 | 4 | 5 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 13 | 117 | 0 | 3 | 22 | 1 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 16 | 9 | 2 | 9 |

| 1 | M | 14 | 114 | 1 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 18 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | M | 14 | 117 | 27 | 6 | 23 | 0 | 8 | 19 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 14 | 125 | 15 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | M | 14 | 148 | 7 | 2 | 21 | 2 | 6 | 20 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 14 | 87 | 4 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 23 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 15 | 187 | 7 | 6 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | M | 15 | 127 | 5 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 15 | 150 | 4 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 16 | 100 | 1 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 5 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 16 | 109 | 6 | 0 | 22 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 16 | 119 | 16 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | M | 17 | 113 | 0 | 7 | 23 | 0 | 3 | 24 | 0 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| 1 | M | 18 | 135 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 6 | 24 | 5 | 2 | 22 | 1 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | M | 7 | 46 | 41 | 1 | 22 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 8 | 79 | 9 | 6 | 22 | 1 | 5 | 18 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| 2 | M | 8 | 91 | 0 | 8 | 22 | 1 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | M | 8 | 78 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 1 | 3 | 22 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 9 | 71 | 6 | 6 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | M | 10 | 107 | 2 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 18 | 10 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | M | 11 | 78 | 23 | 9 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | M | 11 | 121 | 10 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | M | 12 | 153 | 4 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 13 | 127 | 15 | 5 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 15 | 156 | 5 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 17 | 199 | 1 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 6 | 21 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 18 | 161 | 5 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 5 | 19 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| 2 | M | 18 | 171 | 11 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 18 | 209 | 18 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 19 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 18 | 187 | 8 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | M | 18 | 108 | 10 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 19 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | M | 18 | 174 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | M | 18 | 187 | 17 | 5 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | F | 10 | 63 | 0 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 8 | 21 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | F | 14 | 125 | 1 | 6 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 3 |

| 1 | F | 14 | 106 | 7 | 4 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 0 |

| 1 | F | 16 | 143 | 10 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 22 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | F | 16 | 117 | 9 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 14 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | F | 8 | 68 | 5 | 5 | 22 | 1 | 5 | 19 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 8 | 84 | 8 | 5 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 3 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 8 | 30 | 18 | 16 | 19 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 8 | 23 | 7 | 4 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 8 | 85 | 5 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 9 | 105 | 6 | 11 | 23 | 0 | 8 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 11 | 149 | 6 | 7 | 23 | 0 | 3 | 22 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | F | 11 | 103 | 11 | 5 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 22 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 12 | 119 | 9 | 3 | 24 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 12 | 100 | 0 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | F | 12 | 112 | 0 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 13 | 118 | 7 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 13 | 136 | 17 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 13 | 115 | 11 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 3 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 14 | 168 | 3 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | F | 16 | 145 | 8 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 17 | 134 | 12 | 4 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 18 | 173 | 11 | 4 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 18 | 169 | 32 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 18 | 239 | 8 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 19 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 18 | 177 | 3 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 18 | 228 | 11 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 18 | 139 | 7 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 18 | 156 | 3 | 2 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 18 | 156 | 21 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . fifth ed. American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zulueta A., Díaz-Orueta U., Crespo-Eguilaz N., Torrano F. Virtual reality-based assessment and rating scales in ADHD diagnosis. Psicol. Educ. 2018;25(1):13–22. doi: 10.5093/psed2018a18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willcutt E.G. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(3):490–499. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catalá-López F., Peiró S., Ridao M., Sanfélix-Gimeno G., Gènova-Maleras R., Catalá M.A. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in Spain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. BMC Psychiatr. 2012;12(1):168. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barkley R.A. Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. fourth ed. The Guilford Press; 2015. History of ADHD; pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thome J., Ehlis A.-C., Fallgatter A.J., Krauel K., Lange K.W., Riederer P., Romanos M., Taurines R., Tucha O., Uzbekov M., Gerlach M. Biomarkers for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A consensus report of the WFSBP task force on biological markers and the World Federation of ADHD. World J. Biol. Psychiatr. 2012;13(5):379–400. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2012.690535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.López Villalobos J.A., Garrido Redondo M., Sacristán Martín A.M., Martínez Rivera M.T., López Sánchez M.V., Andrés de Llano J.M., Rodríguez Molinero L., Camina Gutiérrez A.B. Children's and adolescents' perception of quality of life in cases of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder with and without drug treatment and in controls. Rev. Neurol. 2018;67(6):195. doi: 10.33588/rn.6706.2017517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Usami M. Functional consequences of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on children and their families. Psychiatr. Clin. Neurosci. 2016;70(8):303–317. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snyder S.M., Rugino T.A., Hornig M., Stein M.A. Integration of an EEG biomarker with a clinician's ADHD evaluation. Brain and Behavior. 2015;5(4) doi: 10.1002/brb3.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koziol L.F., Budding D. Requiem for a diagnosis: attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Appl. Neuropsychol.: Child. 2012;1(1):2–5. doi: 10.1080/21622965.2012.665774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lange K.W., Hauser J., Lange K.M., Makulska-Gertruda E., Takano T., Takeuchi Y., Tucha L., Tucha O. Utility of cognitive neuropsychological assessment in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders. 2014;6(4):241–248. doi: 10.1007/s12402-014-0132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright A.J. Psychological and neuropsychological underpinnings of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder assessment. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatr. 2021;26(3):783–794. doi: 10.1177/1359104521996765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Ruiz J., Hakvoort Schwerdtfeger R.M., Alahyane N., Brien D.C., Coe B.C., Munoz D.P. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex hyperactivity during inhibitory control in children with ADHD in the antisaccade task. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2020;14(6):2450–2463. doi: 10.1007/s11682-019-00196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levantini V., Muratori P., Inguaggiato E., Masi G., Milone A., Valente E., Tonacci A., Billeci L. EYES are the window to the mind: eye-tracking technology as a novel approach to study clinical characteristics of ADHD. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldani S., Razuk M., Septier M., Barela J.A., Delorme R., Acquaviva E., Bucci M.P. The effect of dual task on attentional performance in children with ADHD. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2019;12 doi: 10.3389/fnint.2018.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H., Li Y., Yeh S.-C., Huang Y., Wu Z., Du Z. 2017 2nd International Conference on Information Technology (INCIT) 2017. ADHD assessment and testing system design based on virtual reality; pp. 1–5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan Y., Zhu D., Gao H., Lin T.-W., Wu H.-K., Yeh S.-C., Hsu T.-Y. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Cyber Physical Systems (ICPS) 2019. Virtual classroom: an ADHD assessment and diagnosis system based on virtual reality; pp. 203–208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neguț A., Matu S.-A., Sava F.A., David D. Virtual reality measures in neuropsychological assessment: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016;30(2):165–184. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2016.1144793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin-Moratinos M., Bella-Fernández M., Blasco-Fontecilla H. Effects of music on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and potential application in serious video games: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023;25 doi: 10.2196/37742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lumsden J., Edwards E.A., Lawrence N.S., Coyle D., Munafò M.R. Gamification of cognitive assessment and cognitive training: a systematic review of applications and efficacy. JMIR Serious Games. 2016;4(2):e11. doi: 10.2196/games.5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodrigo-Yanguas M., González-Tardón C., Bella-Fernández M., Blasco-Fontecilla H. Serious video games: angels or demons in patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? A quasi-systematic review. Front. Psychiatr. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.798480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sujar A., Bayona S., Delgado-Gómez D., Miguélez-Fernández C., Ardoy-Cuadros J., Peñuelas-Calvo I., Baca-García E., Blasco-Fontecilla H. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder assessment based on patient behavior exhibited in a car video game: a pilot study. Brain Sci. 2022;12(7):877. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12070877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen H., Asiry O., Babar M.A., Bednarz T. Evaluating the efficacy of using a novel gaze-based attentive user interface to extend ADHD children's attention span. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2023;169 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2022.102927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrigan N., Păsărelu C.-R., Voinescu A. Immersive virtual reality for improving cognitive deficits in children with ADHD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Virtual Real. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s10055-023-00768-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schena A., Garotti R., D'Alise D., Giugliano S., Polizzi M., Trabucco V., Riccio M.P., Bravaccio C. IAmHero: preliminary findings of an experimental study to evaluate the statistical significance of an intervention for ADHD conducted through the use of serious games in virtual reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2023;20(4):3414. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKay E., Kirk H., Coxon J., Courtney D., Bellgrove M., Arnatkeviciute A., Cornish K. Training inhibitory control in adolescents with elevated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder traits: a randomised controlled trial of the Alfi Virtual Reality programme. BMJ Open. 2022;12(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bossenbroek R., Wols A., Weerdmeester J., Lichtwarck-Aschoff A., Granic I., van Rooij M.M.J.W. Efficacy of a virtual reality Biofeedback game (DEEP) to reduce anxiety and disruptive classroom behavior: single-case study. JMIR Mental Health. 2020;7(3) doi: 10.2196/16066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seesjärvi E., Puhakka J., Aronen E.T., Lipsanen J., Mannerkoski M., Hering A., Zuber S., Kliegel M., Laine M., Salmi J. Quantifying ADHD symptoms in open-ended Everyday life contexts with a new virtual reality task. J. Atten. Disord. 2022;26(11):1394–1411. doi: 10.1177/10870547211044214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merzon L., Pettersson K., Aronen E.T., Huhdanpää H., Seesjärvi E., Henriksson L., MacInnes W.J., Mannerkoski M., Macaluso E., Salmi J. Eye movement behavior in a real-world virtual reality task reveals ADHD in children. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24552-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Díaz-Orueta U., Garcia-López C., Crespo-Eguílaz N., Sánchez-Carpintero R., Climent G., Narbona J. AULA virtual reality test as an attention measure: convergent validity with Conners' Continuous Performance Test. Child Neuropsychol. 2014;20(3):328–342. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2013.792332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neguț A., Jurma A.M., David D. Virtual-reality-based attention assessment of ADHD: ClinicaVR: classroom-CPT versus a traditional continuous performance test. Child Neuropsychol. 2017;23(6):692–712. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2016.1186617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iriarte Y., Diaz-Orueta U., Cueto E., Irazustabarrena P., Banterla F., Climent G. AULA—advanced virtual reality tool for the assessment of attention. J. Atten. Disord. 2016;20(6):542–568. doi: 10.1177/1087054712465335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivera M.J., Teruel M.A., Mate A., Trujillo J. Diagnosis and prognosis of mental disorders by means of EEG and Deep learning: a systematic mapping study. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022;55:1209–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10462-021-09986-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loh H.W., Ooi C.P., Barua P.D., Palmer E.E., Molinari F., Acharya U.R. Automated detection of ADHD: current trends and future perspective. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022;146 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bates M.E., Lemay E.P. The d2 Test of attention: construct validity and extensions in scoring techniques. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2004;10(3):392–400. doi: 10.1017/S135561770410307X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brickenkamp R., Schmidt-Atzert L., Liepmann D. first ed. TEA; 2022. D2-R. Revised Attention Test Assessment of Selective Attention and Concentration. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Virtanen P., Gommers R., Oliphant T.E., Haberland M., Reddy T., Cournapeau D., Burovski E., Peterson P., Weckesser W., Bright J., others SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods. 2020;17(3):261–272. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKinney W., others Pandas: a foundational Python library for data analysis and statistics. Python for High Performance and Scientific Computing. 2011;14(9):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wohlin C., Runeson P., Höst M., Ohlsson M.C., Regnell B., Wesslén A. first ed. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012. Experimentation in Software Engineering. [Google Scholar]