Abstract

Background

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a debilitating chronic disease of significant public health and clinical importance. It affects multiple systems in the body and has neuro-immunological characteristics. The disease is characterized by a prominent symptom called post-exertional malaise (PEM), as well as abnormalities in the immune-inflammatory pathways, mitochondrial dysfunctions and disturbances in neuroendocrine pathways. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of ME/CFS on the mental health and secondary psychosocial manifestations of patients, as well as their coping mechanisms.

Method

In 2021, a descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in Switzerland. A self-administered paper questionnaire survey was used to gather data from 169 individuals diagnosed with ME/CFS.

Results

The majority of the patients (90.5%) reported a lack of understanding of their disease, resulting in patients avoiding talking about the disease due to disbelief, trivialization and avoidance of negative reactions. They felt most supported by close family members (67.1%). Two thirds of the patients (68.5%) experienced stigmatization. ME/CFS had a negative impact on mental health in most patients (88.2%), leading to sadness (71%), hopelessness for relief (66.9%), suicidal thoughts (39.3%) and secondary depression (14.8%). Half of the male patients experienced at least one suicidal thought since clinical onset. Factors significantly associated with depression were the lack of cure, disabilities associated with ME/CFS, social isolation and the fact that life was not worth anymore with ME/CFS. The three main factors contributing to suicidal thoughts were (i) being told the disease was only psychosomatic (89.5%), (ii) being at the end of one's strength (80.7%) and (iii) not feeling being understood by others (80.7%).

Conclusion

This study provided first time significant insights into the mental and psychological well-being of ME/CFS patients in Switzerland. The findings highlight the substantial experiences of stigmatization, secondary depression and suicidal thoughts compared to other chronic diseases, calling for an urgent need in Switzerland to improve ME/CFS patient's medical, psychological and social support, in order to alleviate the severe mental health burden associated with this overlooked somatic disease.

Keywords: Depression, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome, Stigmatization, Suicidal ideations, Switzerland

Highlights

-

•

First time study on mental health and well-being among M/CFS patients in Switzerland.

-

•

High level (68.5%) of stigmatization reported due to ME/CFS.

-

•

Overall, ME/CFS led to a third of the patients and to half of the male patients to have suicidal thoughts.

-

•

ME/CFS led to secondary depression in 14.8% of the patients.

-

•

Lack of disease recognition and adequate patient support.

1. Introduction

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a severe multi-systemic disease, of unknown etiology. It is characterized by profound cognitive and physical fatigue and malaise, which typically worsen several hours or on the following days after cognitive and/or physical efforts, and is not relieved by sleep or rest. Additional prominent symptoms include pain, impaired cognitive function, muscle pain and weakness, gastrointestinal problems and sleep disturbances [[1], [2], [3]]. Even minor daily stressors resulting from minimal physical or cognitive effort can trigger an exacerbation of these symptoms. This hallmark symptom, known as post-exertional malaise (PEM), can persist for several days or weeks [1]. The pooled prevalence of ME/CFS is estimated to be around 0.4% of the adult population [4,5]. In Switzerland, this equates to approximately 34′548 individuals affected by ME/CFS, indicating that the disease is not rare.

ME/CFS is still not well-known or fully understood by medical professionals [1], despite the existence of diagnostic criteria and definitions [2,3,6]. The absence of biomarker, coupled with the relatively nonspecific clinical presentation, presents challenges in making an accurate diagnosis. ME/CFS has a global impact on patients, causing a significant reduction in their health-related quality of life, ranging from significant impairment to complete bed-riddenness. It also affects the quality of life of family members [7,8].

Furthermore, the misattribution of ME/CFS to psychological factors, misconceptions and incorrect medical decisions, often result in inadequate medical care and support for patients [9,10], as well as the application of inappropriate and potentially harmful treatments [11,12]. Patients with ME/CFS frequently report experiencing stigmatization from both the medical community and the general population, with rates ranging from 60 to 95%. These levels of stigma are significantly higher compared to several other chronic diseases [[13], [14], [15]]. The experience of stigma and invalidation can have profound impact on the mental health of patients [13,16,17]. This phenomenon is not unique to ME/CFS but is also observed in in other “invisible diseases”, such as Lyme disease, multiple sclerosis, fibromyalgia and Ehlers-Danlos-Syndrome [[18], [19], [20]]. Those affected by these conditions face a double burden, as their symptoms are often compounded by a lack of understanding from others.

However, ME/CFS is not a psychiatric disorder. It is officially classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a neuro-immunological disease. The condition involves a multitude of somatic dysfunctions and impairments that affect various systems simultaneously. These include the autonomous system [21], the hypothalamic pituitary-adrenal axis [22], the central and peripheral neurological system [23], the immune system [[24], [25], [26]], the microbiome [[27], [28], [29]], the mitochondria and its energy production [[30], [31], [32]], among others. It is a complex illness with a wide range of physiological disruptions.

Despite the severity, disabling nature, and non-rarity of the condition, there is currently a lack of official data or studies on ME/CFS patients in Switzerland, to the best of our knowledge. This paper focuses on describing the mental health burden, coping mechanisms, perceived stigmatization and secondary psychological consequences experienced by Swiss patients living with ME/CFS. It is worth noting that the psychosocial burden of the disease remains an under-researched area worldwide. Therefore, our results are not only relevant and significant within in Switzerland, but also have the potential to provide insights into the global challenges faced by ME/CFS patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design, participants and study tool

Data pertaining to the impact on quality of life, mental health, and coping mechanisms were extracted and analyzed from a comprehensive epidemiological research study conducted in Switzerland. The detailed methodology of this study can be found in Tschopp et al., 2023 [33]. The data collection took place between June and September 2021. Participants were selected for inclusion in the study based on their diagnosis of ME/CFS by health care providers, and/or if their symptoms met the criteria outlines in one of the three case definitions (CCC, ICC, IOM). As a purposive sampling strategy was employed, no sample size calculations or randomization procedures were necessary. Upon obtaining informed consent, patients were provided with an anonymized paper questionnaire and requested to self-administer it as part of the data collection process. The questionnaire was prepared in German and French, and had a mixture of closed and open-ended questions. In addition, an open section allowed participants to add any additional information or comments regarding their disease.

2.2. Data management and statistical analysis

Questionnaire data were entered into Microsoft Access and analyzed using STATA software version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, USA). Descriptive statistical analysis was used to describe the study population and group comparisons with p < 0.05 showing a statistical difference among groups. Additional qualitative data collected in the questionnaire were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed descriptively. Quotations were used to illustrate some of the relevant quantitative data.

2.3. Ethical clearance

This research received approval from the Ethics Committee of Northwestern and Central Switzerland (EKNZ, Switzerland, Basec nr. 2021–01098). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

A total of 169 ME/CFS patients participated in the survey. The majority of participants were females (N = 122; 72.2%), middle-aged between 45 and 64 years (N = 89; 52.7%), living alone (single, divorce, widower) (N = 94; 55.6%) and not working (N = 92; 59.7 %).

3.2. Coping with the disease

3.2.1. Disease knowledge and discussion about ME/CFS

The great majority of participants (N = 153; 90.5%) reported that people in their social circles have limited knowledge and understanding of their disease, or are completely unaware of it. Participants indicated that they primarily discussed their disease and its implications with their immediate family members, such as parents, siblings, and spouses/partners (N = 142; 84%). Additionally, a smaller number of participants reported discussing their condition with a few close friends (N = 135; 79.9%). Only a minority of participants (37; 21.9%) mentioned talking to their co-workers about their disease, with a small group (six participants; 4.9%) reported not informing anyone about their disease. Statistical analysis did not reveal any significant difference in the choice of discussion partners based on gender or age group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Discussion partners (N = 169) of participants regarding ME/CFS, by gender and age group.

| Discussion partner |

Overall (N = 169) |

Gender |

Age group in years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (N = 122) | Male (N = 47) | p-value | 13-18 (N = 4) | 19-24 (N = 8) | 25-44 (N = 59) | 45-64 (N = 89) | ≥65 (N = 9) | p-value | ||

| Family | 142 (84) | 105 (86) | 37 (78.7) | 0.243 | 4 (100) | 6 (75) | 53 (89.8) | 71 (79.8) | 8 (88.9) | 0.395 |

| Friends | 135 (79.9) | 101 (82.8) | 34 (72.3) | 0.129 | 2 (50.0) | 6 (75) | 52 (88.1) | 67 (75.3) | 8 (88.9) | 0.167 |

| Co-workers | 37 (21.9) | 24 (19.7) | 13 (27.6) | 0.261 | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (32.2) | 17 (19.1) | 0 (0.00) | 0.067 |

| Nobody | 9 (5.3) | 6 (4.9) | 3 (6.4) | 0.704 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (1.7) | 7 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.376 |

Sixty-three respondents provided reasons for not talking to people about their disease (Table 2). Misunderstandings/disbelief about the disease (N = 49, 77.8%) and avoidance of negative reactions in people (N = 28, 44.4%) were most frequently mentioned.

Table 2.

List of reasons provided by ME/CFS participants on why they do not discuss their disease with other people (N = 63).

| Reasons | Number | Patients quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Misunderstanding about the disease | 49 | |

| Disbelief and lack of understanding of the disease by other people | 37 | “They do not understood and they often say “you are not sick".” (ID 94, F, 41) |

| “I fear of not being understood; it is a too complicated disease to explain; It is tiring to always tell the same story; if I had cancer they would understand.” (ID 170, F, 52) | ||

| “I fear of not being taken seriously by people. I gave my medical report to my GP written by a physician in London who diagnosed me with ME/CFS. My GP then said that ME/CFS did not exist.” (ID 64, F, 51) | ||

| “People cannott believe that appointments lead to me being bed for one day; activities, such as big cleaning up, puts me to bed for one to two weeks.” (ID 203, F, 47) | ||

| Receiving advises on what to do | 7 | “People always say I just need some more will-power.” (ID 69, F, 18) “People don't understand the disease but they all want to advise me on what to do.” (ID 141, M, 23) |

| Trivialization of the disease (not taken seriously, belittled) | 4 | “People tell me that I look good from the outside and that everybody is a bit tired. I had to stop working for 10 years due to my severe disability.” (ID 75, F, 62) “People see me only during the days when I am feeling better, so they cannot understand that I am so sick.” (ID 60, M, 58) “For people it is hard to understand the severity of the disease, because they see me only during my better days.” (ID 82, M, 44) |

| Experiencing prejudice | 1 | “The doctor said that since I have a university diploma, I was well able to work 100%.” (ID 93, F, 54) |

| Avoidance of negative reactions | 28 | |

| Fear of perceived stigmatization | 7 | “I don't want to complain, of fear of what people would think.” (ID 64, F, 51) “It would be too stigmatizing at work if I talked about my disease.” (ID 36, F, 33) “People don't understand when I talk about my disease. As a result they distance from me” (ID 146, F, 52) |

| Hurtful experiences of humiliation, guilt, shame and embarrassement | 7 | “My boss sees me only during the good days when my symptoms are mild, hence he accuses me of being lazy, which constantly makes me feel guilty.” (ID 131, F, 31) “People tell me that I am just lazy and I don't want to work.” (ID 124, F, 52) “People belittle me, they ignore my symptoms and act as if it is nothing.” (ID 122, F, 53) |

| Fear of negative consequences at work | 4 | “I was fired from my job because of long sick leave due to ME/CFS.” (ID 166, F, 55) “I fear negative consequences at work if people know about my disease.” (ID 151, F, 46) |

| Being considered to be a psychological issue | 4 | “It is hard when people always think you are mentally ill. The psychological stigmatization affects me.” (ID 82, M, 44) |

| Ignorance | 4 | “When you have ME/CFS, you realize that your life is gradually destroyed and ignored. It is frightening that this disease seems to be virtually not recognized as if it does not exist.” (ID 54, M, 30) “The worst aspect about the disease is the ignorance. It is offending and it is a disregard of the most basic human rights”. (ID 37, M, 52) “I was left unsupported and isolated by everyone … family, friends, physicians - because nobody knew ME/CFS” (ID 146, F, 52) |

| Being judged, experiencing blame | 2 | “People give me the blame for my symptoms.” (ID 124, F, 52) |

| Conversations leading to distress | 10 | |

| Difficulty to explain the disease; invisible illness from the outside | 7 | “It is a complex disease, on the outside I don't look sick. We should wear a T-shirt saying “The club of the good-looking sick” to avoid stigmatization.” (ID 203, F, 47) |

| Not wanting to be a burden to the family | 2 | “It is hard for a mother not to be able to participate in activities with your children. I also feel guilty towards my husband.” (ID 89, F, 46) “I don't want to be a burden to my family.” (ID 6, F, 34) |

| People feel uncomfortable talking about it | 1 | “I always feel people get uncomfortable when I talk about my disease.” (ID 70, F, 49) |

| Conversations being stressful or exhausting | 8 | |

| Too weak to speak; exhaustion linked to long explanatory conversations | 4 | “Instead of investing my time in promoting my health and saving my strength, I have instead to constantly fight for acceptance and belief.” (ID 52, F, 24) “The disease is difficult to explain and it leads to long exhausting explanatory conversations; I am often judged as well.” (ID 178, M, 37) |

| Not wanting to think about the disease once feeling well enough to interact with people. | 2 | “I don't want to think or talk about my disease when I have the chance to spend some positive time with a friend or family member.” (ID 185, F, 22) |

| Constantly having to justify yourself | 2 | “It takes me so much energy to fight for acceptance, also when dealing with social services.” (ID 203, F, 47) “I always have to tell the same story, over and over again and people still do not understand the disease.” (ID 200, F, 47) |

3.2.2. Support and help seeking behavior

All participants stated they needed support to cope with ME/CFS. The majority of respondents (N = 143; 84.6%) used a combination of different support sources. Close family members provided the biggest support (N = 112; 67.1%), followed by very close friends (N = 67; 40.1%), physicians (N = 49; 29.3%), faith/spirituality (N = 39; 23.3%), the Swiss ME/CFS association (N = 39; 23.3%), psychologists (N = 35; 21.0%), ME/CFS support groups (N = 21; 12.6%) and other unspecified sources (N = 19; 11.4%). Seventeen participants (10.2%) cited that there was no support available for them at all.

Table 3 shows the different support sources used by gender, age-groups and disease duration. The longer the disease duration, the more participants did turn to church/faith/spirituality, to the Swiss ME/CFS association and to psychologists.

Table 3.

Help seeking sources for Swiss ME/CFS patients by gender, age-group and disease duration.

| None | Family | Friends | Church/faith | ME/CFS association | ME/CFS support groups | Psychologists | Doctors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 167) | Female (N = 121) | 14 (11.6) | 82 (67.8) | 55 (45.4) | 27 (22.3) | 27 (22.3) | 15 (12.4) | 27 (22.3) | 39 (32.2) |

| Male (N = 46) | 6 (13.0) | 30 (65.2) | 12 (26.1) | 12 (26.1) | 12 (26.1) | 6 (13.0) | 12 (26.1) | 17 (36.9) | |

| p-value | 0.793 | 0.754 | 0.023 | 0.607 | 0.607 | 0.910 | 0.607 | 0.563 | |

| Age Group (n = 167) | 13-18 (N = 4) | 0 (0) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) |

| 19-24 (N = 8) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25.0) | |

| 25-44 (N = 59) | 1 (1.7) | 45 (76.3) | 25 (42.4) | 12 (20.3) | 10 (16.9) | 10 (16.9) | 14 (23.7) | 19 (32.2) | |

| 45-64 (N = 87) | 14 (16.1) | 54 (62.0) | 37 (42.5) | 22 (25.3) | 26 (29.9) | 11 (12.6) | 20 (23.0) | 33 (37.9) | |

| ≥65 (N = 9) | 4 (44.4) | 3 (33.3) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | |

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.050 | 0.613 | 0.627 | 0.270 | 0.400 | 0.797 | 0.521 | |

| Disease duration (years) (n = 165) | 1-3 (N = 23) | 1 (4.3) | 15 (65.2) | 11 (47.8) | 6 (26.1) | 3 (13.0) | 3 (13.0) | 9 (39.1) | 10 (43.5) |

| 4-10 (N = 50) | 8 (16.0) | 36 (72.0) | 19 (38.0) | 8 (16.0) | 5 (10.0) | 5 (10.0) | 12 (24.0) | 14 (28.0) | |

| 11-20 (N = 57) | 8 (14.0) | 40 (70.2) | 19 (33.3) | 11 (19.3) | 16 (28.1) | 9 (15.8) | 8 (14.0) | 16 (28.1) | |

| 21-30 (N = 22) | 1 (4.5) | 13 (59.1) | 9 (40.9) | 7 (31.8) | 8 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 4 (18.2) | 10 (45.4) | |

| >30 (N = 13) | 2 (15.4) | 6 (46.1) | 8 (61.5) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (38.5) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (46.1) | 5 (38.5) | |

| p-value | 0.475 | 0.405 | 0.374 | 0.046 | 0.026 | 0.244 | 0.041 | 0.403 |

3.2.3. Mental health impacts

ME/CFS had in most respondents a negative impact on mental health (N = 149; 88.2%). Male patients (N = 45, 95.7%) reported more often to be mentally affected by ME/CFS than women (N = 104, 85.2%; p = 0.05). Age and disease duration did not affect participant's mental health status (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Reported negative impact of ME/CFS on Swiss patients' mental health by gender, age-groups and disease duration.

A 49-year-old female patient described: “I have a lot of negative feelings towards the disease: There is no therapy available, the disease is not recognized, there is no specific diagnostic marker and there is no chance for healing. ME/CFS makes me lonely and socially isolated.” (ID 184).

An 18-year-old female student also stated: “It's not easy to see everyone enjoying their lives and having fun while my life is derailed due to ME/CFS. I would so much love to live a life like all the other people. I do not want to worry about finances, doctor's appointments, education, job and family life. I don't want to just survive; I want to live.” (ID 69).

Patients were then asked to describe the feelings that contributed to the negative mental health impacts (Table 4). Sadness (N = 103, 71%), followed by feeling hopeless for possible relief (N = 97, 66.9%) were the two major negative feelings. Fifty-seven respondents (39.3%) stated to have experienced at least once suicidal thoughts (N = 57, 39.3%). The majority of the patients stated ME/CFS made them feel depressed (N = 56, 38.6%), experience fear (N = 56, 38.6%), anger/frustration (N = 19, 13.1%) and other undescribed feelings (N = 19, 13.1%).

Table 4.

Types of feelings reported with negative impact on Swiss ME/CFS respondents’ mental health.

| Variables | Category | Sadness | Hopelessness | Depression | Fear | Suicidal | Anger | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 145) | Female (n = 102) | 77 (75.5) | 68 (66.7) | 37 (36.3) | 41 (40.2) | 35 (34.3) | 16 (15.7) | 12 (8.0) |

| Male (n = 43) | 26 (60.5) | 29 (67.4) | 19 (44.2) | 15 (34.9) | 22 (51.2) | 3 (7.0) | 8 (18.6) | |

| p-value | 0.06 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.07 | |

| Age-groups (n = 143) | 13-18 (n = 3) | 3 (100) | 2 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) |

| 19-24 (n = 8) | 6 (75.0) | 7 (87.5) | 5 (62.5) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 25-44 (n = 46) | 34 (73.9) | 31 (67.4) | 12 (26.1) | 18 (39.1) | 16 (34.8) | 5 (10.9) | 12 (26.1) | |

| 45-64 (n = 80) | 56 (70.0) | 53 (66.2) | 36 (45.0) | 29 (36.2) | 35 (43.7) | 11 (13.7) | 6 (7.5) | |

| ≥65 (n = 8) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 1 (12.5) | 2 [25] | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | |

| p-value | 0.520 | 0.629 | 0.047 | 0.442 | 0.554 | 0.859 | 0.030 | |

| Disease duration (years) | 1-3 (n = 19) | 16 (84.2) | 11 (57.9) | 4 (21.0) | 8 (42.1) | 5 (26.3) | 3 (15.8) | 3 (15.8) |

| 4-10 (n = 44) | 31 (70.4) | 32 (72.7) | 20 (45.4) | 17 (38.6) | 18 (40.9) | 4 (9.0) | 5 (11.4) | |

| 11-20 (n = 49) | 29 (59.2) | 33 (67.3) | 20 (40.8) | 20 (40.8) | 22 (44.9) | 5 (10.2) | 9 (18.4) | |

| 21-30 (n = 21) | 17 (80.9) | 13 (61.9) | 6 (28.6) | 5 (23.8) | 6 (28.6) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (9.5) | |

| >30 (n = 10) | 8 (80.0) | 6 (60.0) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0 (0) | |

| p-value | 0.179 | 0.772 | 0.299 | 0.611 | 0.308 | 0.444 | 0.536 |

A 48-year-old female described: “Becoming dependent on other people and knowing that there is not cure made me become depressed as a consequence of ME/CFS.” (ID 104).

Table 5 shows the types of feelings experienced by gender, age groups and disease duration. Men reported more often suicidal thoughts than women did (p = 0.05). Half of the men experienced at least once suicidal ideations (N = 22, 51.2%). Four out of the 169 patients (2.4%) reported that ME/CFS led them to register with EXIT (Organized Society under Swiss Law for physician-assisted suicides) and one additional patient reported to do so if the disease would worsen. A 50-year-old male for example stated: “After becoming sick with ME/CFS, I have registered with EXIT. I will not let it happen that I end in bed being fed by somebody else.” (ID 101).

Table 5.

Reasons associated with negative mental health by gender and age-group among participants.

| Category |

Overall |

Gender |

Age group in years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (N = 105) | Male (N = 44) | p-value | 13-18 (N = 4) | 19-24 (N = 8) | 25-44 (N = 59) | 45-64 (N = 89) | ≥65 (N = 9) | p-value | ||

| Loss of worth | 37 (24.8) | 24 (22.8) | 13 (29.5) | 0.389 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (25.0) | 9 (18.4) | 22 (27.2) | 3 (37.5) | 0.711 |

| Constant pains | 61 (40.9) | 44 (41.9) | 17 (38.6) | 0.711 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (25.0) | 19 (38.8) | 36 (44.4) | 3 (37.5) | 0.834 |

| Unable to do what wanted | 119 (79.9) | 83 (79.0) | 36 (81.8) | 0.700 | 2 (66.7) | 6 (75) | 42 (85.7) | 63 (77.8) | 6 (75) | 0.768 |

| Social isolation | 86 (57.7) | 61 (58.1) | 25 (56.8) | 0.886 | 3 (100) | 4 (50.0) | 28 (57.1) | 49 (60.5) | 2 (25.0) | 0.187 |

| Lack of understanding | 101 (67.8) | 75 (71.4) | 26 (59.1) | 0.142 | 2 (66.7) | 7 (87.5) | 32 (65.3) | 54 (66.7) | 6 (75) | 0.772 |

| Lack of support | 65 (43.6) | 46 (43.8) | 19 (43.2) | 0.944 | 1 (33.3) | 5 (62.5) | 22 (44.9) | 35 (43.2) | 2 (25.0) | 0.653 |

| Financial stress | 86 (57.7) | 59 (56.2) | 27 (61.4) | 0.560 | 3 (100) | 3 (37.5) | 28 (57.1) | 51 (63) | 1 (12.5) | 0.025 |

| Be at the end of owns strength | 119 (79.9) | 85 (80.9) | 34 (77.3) | 0.609 | 3 (100) | 5 (62.5) | 36 (73.5) | 68 (84) | 7 (87.5) | 0.327 |

| Life not worth living with the disease | 80 (53.7) | 53 (50.5) | 27 (61.4) | 0.224 | 2 (66.7) | 6 (75) | 26 (53.1) | 43 (53.1) | 3 (37.5) | 0.640 |

| Other | 13 (8.7) | 11 (10.5) | 2 (4.5) | 0.242 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (12.2) | 7 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 0.630 |

There was a notable difference in the emotional experiences related to ME/CFS between age groups. Younger participants (13–24 year) reported experiencing feeling of depression, fear and anxiety about the future, hopelessness and sadness more frequently compared to older age groups. Specifically, a higher percentage of younger participants (66.7%) reported feelings of anxiety and fear, whereas this percentage decreased as age increased. In the oldest age category, only 25% of respondents reported experiencing anxiety and fear related to their ME/CFS.

A 30-year-old male described: “ME/CFS destroys your life, you have to live with constant pains and severe symptoms and you have no support, because nobody knows the disease and that is a big mental health burden. In addition, since the disease is not recognized, you know there will be no financial or social support and that makes me fearing the future.” (ID 54).

Duration of the disease did not affect the types of experienced feelings (Table 4). However, suicidal thoughts (N = 6, 60%), the feelings of being depressed (N = 5, 50%), feeling fear (N = 5, 50%) and anger (N = 3, 30%) were stated most frequently by the patients having lived with the disease for over 30 years.

Reasons underlying these feelings are shown in Table 5 (N = 149). Overall, the great majority of respondents (N = 119, 79.9%) stated that they were not able anymore to do what they wanted/what they had planned in life and that they constantly felt being at the end of their strength.

Over half of the patients stated that social isolation (N = 86, 57.7%), financial stress (N = 86, 57.7%) and their life not being worth living with this disease (N = 80, 53.7%) led to negative mental health impact. There were no statistical differences by gender.

A 48-year-old female describes: “It is hard to deal with a disease, when you have to also carry the burden of being dependent on others, being in need of care, having to see how your health constantly deteriorates instead of getting better and the battle of acceptance by doctors and insurances. With all this, I do not see any perspective anymore for the future, the helplessness is huge.” (ID 104).

A 42-year-old male likewise stated “I am the sole bred earner of the family and I am constantly anxious and stressed about the future financial security of the family, which does not help my health.” (ID 72).

3.2.4. Depression and suicidal thoughts

At the initial onset of ME/CFS, thirteen participants (7.7%) reported experiencing mild depression or anxiety. Among these participants, ten were female (8.2%) and three were male (6.4%). However, the difference in gender distribution was not statistically significant (p = 0.692). The occurrence of these mild depression or anxiety was often associated with a specific notable event, such as an accident, the loss of a loved one, unemployment, or a relationship break-up/divorce). Among the six individuals (3.6%) stated they no longer experienced depressive thoughts after the onset of the disease. On the other hand, seven participants (4.1%) continued to experience depressive symptoms after the onset of ME/CFS.

At the time of the interview (after suffering from ME/CFS for various numbers of years), 32 respondents (18.9%) stated suffering from depression; 22 were women (18%) and ten were males (21.3%). Twenty-five respondents (78.12%) stated that they have never been depressed before the onset of ME/CFS.

When describing the feeling after the diagnosis, a 53-year-old female patient stated:

“Once I received the diagnosis ME/CFS I knew there was no use to go to the doctors, since there is no therapy available, and nobody can help you. I became depressive as a consequence of ME/CFS.” (ID 56)

In the sub-population of individuals who developed depression after the onset of ME/CFS (reactive depression), associations between various factors and clinical depression were explored (N = 25) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors associated with the development of depression after the onset of ME/CFS in 25 participants.

| Secondary Depression | Categories | Total number | Number of depressed patient (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmatization | None | 49 | 8 (16.3) | ||

| Yes | 103 | 15 (14.6) | 0.777 | ||

| Feelings associated with ME/CFS | Suicidal thoughts | None | 84 | 11 (13.1) | |

| Yes | 50 | 14 (28.0) | 0.032 | ||

| Fear (worsening of symptoms, dependency) | None | 84 | 10 (11.9) | ||

| Yes | 50 | 15 (30.0) | 0.009 | ||

| Sadness | None | 39 | 6 (15.4) | ||

| Yes | 95 | 19 (20.0) | 0.533 | ||

| Hopelessness for relief (no therapy, no support, poor prognosis) | No | 46 | 4 (8.7) | ||

| Yes | 88 | 21 (23.9) | 0.032 | ||

| Anger | No | 116 | 22 (19.0) | ||

| Yes | 18 | 3 (16.7) | 0.816 | ||

| ME/CFS outcomes | Feeling of becoming less since the disease | No | 105 | 14 (13.3) | |

| Yes | 33 | 11 (33.3) | 0.009 | ||

| Chronic pains | No | 84 | 16 (19.0) | ||

| Yes | 54 | 9 (16.7) | 0.723 | ||

| Cannot do what I want anymore | No | 29 | 7 (24.1) | ||

| Yes | 109 | 18 (16.5) | 0.343 | ||

| Social isolation | No | 59 | 6 (10.1) | ||

| Yes | 79 | 19 (24.0) | 0.036 | ||

| Disease/patient not understood | No | 46 | 6 (13.0) | ||

| Yes | 92 | 19 (20.6) | 0.274 | ||

| Lack of support | No | 79 | 16 (20.2) | ||

| Yes | 59 | 9 (15.2) | 0.451 | ||

| Financial stress | No | 60 | 9 (15.0) | ||

| Yes | 78 | 16 (20.5) | 0.405 | ||

| Be at the end of one's strength | No | 27 | 3 (11.1) | ||

| Yes | 111 | 22 (19.8) | 0.292 | ||

| Life has become worthless | No | 67 | 5 (7.5) | ||

| Yes | 71 | 20 (28.2) | 0.002 | ||

| Lack of communication (no sharing with others about CFS) | No | 147 | 23 (15.6) | ||

| Yes, no communication | 9 | 2 (22.2) | 0.602 | ||

| Be told by doctors that it is only psychosomatic | No | 15 | 1 (6.7) | ||

| Yes | 141 | 24 (17.0) | 0.299 | ||

| Having children | No | 96 | 14 (14.6) | ||

| Yes | 60 | 11 (18.3) | 0.534 | ||

| Sex | Female | 112 | 17 (15.2) | ||

| Male | 44 | 8 (18.2) | 0.645 | ||

| Workload | No work/not able to work anymore | 87 | 18 (20.7) | ||

| Fulltime work | 6 | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Part-time work | 54 | 6 (11.1) | 0.177 | ||

| Marital status | Single (incl. widowhood, divorcee) | 86 | 18 (20.9) | ||

| Married/partnership | 70 | 7 (10.0) | 0.064 | ||

| Disease severity | Bed-bound | No | 138 | 23 (16.7) | |

| Yes | 11 | 2 (18.2) | 0.897 | ||

| House and/or bed-bound | No | 69 | 9 (13.0) | ||

| Yes | 80 | 16 (20.0) | 0.257 |

Several factors were found to be associated with depression in this subgroup. These included: 1) fear of the future (e.g. fear of becoming socially and/or financially depended on other people; lack of support; concerns about the worsening of symptoms over time), 2) hopelessness about the future due to poor ME/CFS prognosis (including the lack of available treatments or therapies that could provide relief), 3) feeling diminished due to the disabilities causing limitations to engage in previously enjoyed activities and fulfill goals and dreams, 4) social isolation (symptoms limiting the participation in social activities and maintain relationships) and 5) belief that life is not worth anymore with ME/CFS.

For example, a 42-year-old female said: “The most thing difficult to handle is to know that there is no treatment and hence it will never get better.” (ID 8).

Another participant added: “What worries me the most is to be totally dependent on my 75 year old mother and have no other support; I fear the future.” (ID 110).

Table 7 shows potential factors associated with suicidal thoughts. Being told the disease is only psychosomatic was the factor that contributed the most to suicidal thoughts in ME/CFS patients (N = 51, 89.5%). This was followed by constantly being at the end of one's strength (80.7%), not being understood (80.7%), the inability to do what one's wants to do/having to give up loved activities (79%), seeing life with this severe disease becoming worthless (77.2%), being stigmatized as a result of ME/CFS (76.8%), not being able to work anymore (65%), to become socially isolated (64.9%), to experience financial stress (64.9%) and the feeling of not being supported (54.4%).

Table 7.

Factors associated with reported suicidal thoughts after the onset of ME/CFS (N = 57).

| Factor | Category | Total number | Number of suicidal patients (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmatization | No | 43 | 13 (30.2) | 0.139 |

| Yes | 99 | 43 (43.4) | ||

| Disease severity- bed bound cases | No | 128 | 50 (39.0) | 0.315 |

| Yes | 11 | 6 (54.5) | ||

| Workload | Not able to work anymore | 86 | 36 (41.9) | 0.602 |

| Full time | 5 | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Part time | 47 | 18 (38.3) | ||

| Being told it is psychosomatic | No | 13 | 6 (46.1) | 0.596 |

| Yes | 132 | 51 (38.6) | ||

| Clinical depression | No | 114 | 39 (34.2) | |

| Yes | 31 | 18 (58.0) | 0.032 | |

| Chronic pains | No | 84 | 29 (34.5) | 0.142 |

| Yes | 60 | 28 (46.7) | ||

| Social isolation | No | 60 | 20 (33.3) | 0.195 |

| Yes | 84 | 37 (44.0) | ||

| Cannot do what one's want anymore (giving up loved activities) | No | 28 | 12 (42.8) | 0.693 |

| Yes | 116 | 45 (38.8) | ||

| Be at the end of one's strength | No | 28 | 11 (39.3) | 0.971 |

| Yes | 116 | 46 (39.6) | ||

| Financial stress | No | 60 | 20 (33.3) | 0.195 |

| Yes | 84 | 37 (44.0) | ||

| Not be understood | No | 44 | 11 (25.0) | 0.018 |

| Yes | 100 | 46 (46.0) | ||

| Feeling of not being supported | No | 79 | 26 (32.9) | 0.071 |

| Yes | 65 | 31 (47.7) | ||

| Worthless life | No | 65 | 13 (20.0) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 79 | 44 (55.7) |

A 63-year-old female participant stated: “What bothers me the most is to be excluded from everything and not being able to take part in life.” (ID 149).

A 30-year-old male described: “The scary part about living with the disease is that you are left alone with constant pains, severe symptoms and, additionally you have to deal with doctors who don't take you seriously, with a lack of recognition, and with no financial and social support. I have existential fear. All this, is a huge mental burden to deal with, besides the disease.” (ID 54).

A 38-year-old female described: “I know a lot of people, but due to my severe condition I can only interact with a small circle of friends. I have to isolate myself most of the time at home alone.” (ID 12).

A 52-year-old female stated: “I am bedbound since 25 years and constantly socially isolated due to my severe condition. I live alone at home, but I need help with cleaning, washing, preparing meals, etc. Due to the disease, I am afraid of the future and started developing panic attacks and depression.” (ID 181).

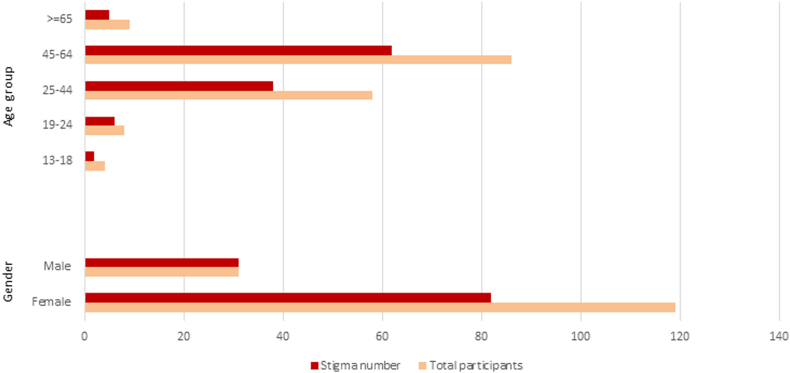

3.2.5. Stigmatization

Two thirds of the patients (N = 113, 68.5%) reported experiencing stigmatization (Fig. 2). There were no differences based on gender or age-group. Among these participants, 107 listed the types of perceived stigmatization, which were categorized into four main groups: misperception about the disease (N = 88, 82.2%), blame and judgement (N = 45, 42.2%), discriminatory behavior (N = 29, 27.1%) and inappropriate behavior (N = 13, 12.1%) (Table 8).

Fig. 2.

Perceived stigmatization reported by gender and age-group in 150 Swiss ME/CFS participants.

Table 8.

Self-reported types of perceived stigmatization by 107 ME/CFS patients.

| Misperception about the disease | 88 |

|---|---|

| Not be taken seriously, lack of understanding, | 40 |

| Mistaken for being mentally ill, being a liar, a simulator; the disease is thought to be imaginary | 22 |

| Giving senseless or counterproductive advice/comments | 13 |

| Disbelief in the severity of the condition, trivializing symptoms | 12 |

| Belief that symptoms are due to the misuse of drugs/alcohol (brain fog) | 1 |

| Blame and judgment | 45 |

| Considered to be a “social parasite"/freeloader, accused of being lazy/avoiding work in purpose | 21 |

| Accused of being weak, hypersensitive and told to complain less | 10 |

| Accused of exaggerating the symptoms, being a hypochondriac | 6 |

| Being judged by the activity level | 5 |

| Be blamed for the disease | 3 |

| Discriminatory behavior | 29 |

| Social avoidance/rejection | 21 |

| People around patients change their behavior | 5 |

| Other people make patient feel diminished | 2 |

| Patients are considered as unfriendly | 1 |

| Inappropriate behavior | 13 |

| Paternalizing and patronizing behavior | 7 |

| Overwhelmed in dealing with the condition | 5 |

| Forgeting the limitations of the disease | 1 |

4. Discussion

Although ME/CFS is recognized to be a serious organic illness [1,3], the misconception and belief that it is a mental illness or is “not real”, is still a widespread belief around the world [16,34]. Lack of awareness and disease knowledge as well as the absence of disease-specific markers are known to increase stigmatization in society [1,34], which was also observed in Long-/Post-COVID-Syndrome cases [35] and other chronic invisible diseases [[18], [19], [20]].

Our study provides compelling evidence of the considerable negative impact that ME/CFS has on mental health and overall mental well-being of patients in Switzerland. The ability to share and discuss the disease and its impact plays a crucial role in patients' coping mechanisms. One significant finding is that the majority of participants (90.5%) reported a lack of disease knowledge among physicians and within the broader community. Consequently, their discussion opportunities were primarily limited to close family members such as spouses, parents or siblings (84%), along with a few very close friends (79.9%). Notably, women (45.4%) were observed to engage in these discussions with friends more frequently than men (26.1%). Our results emphasize the significant importance of family support in navigating the challenges posed by ME/CFS, particularly among in young adult patients. Having a stable, supportive, and understanding family environment is crucial for ME/CFS patients’ wellbeing. However, it is important to recognize that families themselves-who are often sole caregivers-also struggle when a member is affected by ME/CFS [8,36]. The impact of the condition extends beyond the individual patient and can strain familial relationships considering potential shifts in professional work decision, additional burden of caregiving, financial burden, and constant patient support. Families would greatly benefit from external support and understanding. Respondents in our study highlighted the disheartening experiences of encountering disbelief, and trivialization of their disease by others. They reported facing prejudiced reactions, and engaging in stressful or exhausting conversations that ultimately led to distress. These negative experiences further discouraged patients from discussing their conditions with others, thus intensifying feelings of loneliness and social isolation. Given these challenges, it is evident that ME/CFS patients and their families require additional support systems providing understanding, empathy and guidance, that extend beyond their immediate circles.

Overall, most study participants perceived widespread stigmatization (68.9%), suspicion and disbelief, not only by healthcare professionals and medical institutions, but also by relatives and society. Our data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Long-/Post-COVID-Syndrome cases gained attention in the general population, the press and the medical community. The increased awareness of the potential for severe exhaustion following even minimal exertion as a consequence of an infectious disease could potentially contribute to the comparatively lower stigma reported in our study, when compared to previous research [37]. Nevertheless, the stigmatization perceived by ME/CFS patients remains significantly higher than that reported by patients with other chronic diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, epilepsy or Parkinson's disease [15,34].

Patients who experience stigmatization and a lack of disease knowledge within society are forced to continually struggle for acceptance, understanding, and access to adequate medical care as shown in our previous study [12]. This uphill battle is often compounded by a lack of financial support. The consequences are far-reaching, including social isolation, traumatic experiences, reduced satisfaction with health and social systems, existential fear and further detrimental effects on overall health status. This psychosocial impact is not unique to ME/CFS. It is also observed in other chronic diseases such as multiple sclerosis [38], where stigma has been associated with a decline in both physical and mental quality of life as well as heightened symptoms of anxiety and depression.

The great majority of the participants (88.2%) reported that the disease negatively affected their mental health. This was more frequently reported by male participants. Among the various emotions associated with ME/CFS, feelings of sadness (71%) and a sense of hopelessness regarding relief and cure (66.9%) were the most commonly reported, particularly among younger patients. However, the qualitative data provided valuable insights suggesting that these negative feelings were not constant but rather fluctuated over time. They were observed to intensify, especially when the patient experienced severe worsening of all symptoms during a so called “crash” or episode that can lead up to being house-wheelchair or even bed-bound.

Participants highlighted two main reasons that contributed to their experience of negative feelings associated with ME/CFS. First, there was a profound sense of frustration and disappointment stemming from their inability to pursue the activities and life plans they had envisioned (79.9%). Second, the persistent and debilitating fatigue left them constantly feeling depleted and exhausted (79.9%). A similar situation is observed among patients with multiple sclerosis [39], a condition that often affects individuals at a young age. Fatigue and rapid exhaustion are common and distressing symptoms, which also hinders their social interaction with family and friends. This high burden of fatigue has a profound impact on the daily lives of these patients, leading to further negative effects on their relationships and their psychological wellbeing.

More than half of the respondents in our study emphasized several additional factors that negatively impacted their mental well-being in relation to ME/CFS. These factors included a lack of understanding for the disease from society and medical services, social isolation and financial stress. Particularly in younger age groups, there was a heightened sense of financial stress and fear regarding future livelihood opportunities.

Our previous study, aligning with international findings, revealed that two-thirds of ME/CFS patients were unable to work due to the disease [33]. Furthermore, half of the patients (53.7%) expressed the sentiment that a life with ME/CFS was not truly worth living. Our qualitative data shed light on the fact that these patients did not necessarily desire death itself, but rather conveyed the exhaustion, pain, debilitation and profound socio-economic consequences brought about by the disease. This toll on the patient's lives has been similarly reported in other international studies [40,41] examining chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, Parkinson's disease, cerebrovascular diseases, arthritis and chronic pain disorders in general.

Psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression are potential co-morbid conditions observed not only in ME/CFS patients [1,42] but also in other chronic diseases where a cure is not currently available [43] Our results indicate that the majority of ME/CFS patients (81.1%) were not depressed and had no reported co-existing psychiatric disorders, irrespective of the severity of their disease. Prior to the onset of ME/CFS, 7.7% of our patients had a history of depression. This prevalence is not significantly higher than the lifetime prevalence of depression in the general population [[44], [45], [46]] or the rates observed in other chronic diseases [42,47].

However, some patients may experience a secondary depressive reaction or an emotional response to the profound impact of their chronic illness. The majority (78.1%) of the 32 patients who reported depression during the interviews developed this condition after the onset of ME/CFS. This observation aligns with the increased prevalence of anxiety or depression observed in other debilitating chronic medical conditions [41,48].

It is important to acknowledge that the frequency of depression reported in our study may be underestimated, as we did not conduct specific psychological evaluations. However, our data support existing evidence that psychological symptoms in ME/CFS patients are likely to be reactive in nature. The vast majority of participants (96%) who reported experiencing depression at the time of the study (96%) attributed their depression to the severity of the disease and various disease-related external factors.

These factors included the lack of understanding from others, including society and medical services, the stigmatization encountered from physicians, the inability to work leading to financial instability, social isolation resulting in confinement to the home or bed and being told that their disease was psychosomatic. Depression, sadness and fear as a response to ME/CFS has been described in various studies conducted in North America, Asia, Europe and Australia. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting a higher risk for depression in patients with lower incomes or inadequate social support [42,49].

The statistically significant factors associated with a secondary depression in our study were fear of becoming dependent due to a progressive deterioration of symptoms, lack of support, a sense of hopelessness regarding the future without a cure or effective therapy, social isolation, and the perception that life is not worth living with ME/CFS. These factors differed from classical depression symptoms, which typically involve feelings of worthlessness, guilt, low self-esteem, loss of interest in activities that were previously enjoyed, lack of motivation and diminished interest in friendships/relationships [50]. All these classical symptoms were not observed in our ME/CFS patients.

A significant majority of the participants in our study (79.9%) experienced emotional distress stemming from their inability to pursue the activities they desired in life due to the debilitating symptoms of ME/CFS, which often rendered them house- or bed-bound. In ME/CFS patients, symptoms worsen significantly after physical or mental exertion, contrasting with individuals with depression who typically experience improvement after engaging in physical or social activities [50]. ME/CFS patients are known for “pushing through” and attempting to engage in activities beyond their physical strength, despite experiencing a lack of energy (e.g. due to mitochondrial impairment). This behavior often leads to a subsequent crash or exacerbation of symptoms [1].

Therefore, our study aligns with a growing body of international research that highlights the distinct causal, symptomatic and therapeutic response differences between depression and ME/CFS [12,50,51].

Interestingly, we found that the severity of the disease did not have a significant impact on whether a patient experienced depression or not. Surprisingly, 23 out of the 25 severely bed-bound patients (92%) reported not being depressed. This finding aligns with previous conducted studies from North America that demonstrated that house-bound patients were three times more likely to die by suicide compared to those who were more severely affected and bedridden [52]. Severely ill bedridden patients, who have been in that state for months or even years, might encounter less stigmatization and have access to greater financial and social support compared to those who are “only” homebound. The latter group may face more challenges justifying themselves in society, at work or when dealing with medical services and insurance companies.

Although ME/CFS is not considered a psychogenetic disorder, it is noteworthy that approximately one-third of all ME/CFS patients (33.7%) reported experiencing suicidal thoughts, which is consistent with a recent study performed by McManimen et al. (2018) [13]. Alarmingly, suicide has been identified as one of the leading causes of death among ME/CFS patients, alongside cancer and heart disease [[1], [53]]. Half of the men in our cohort reported having suicidal thoughts at least once due to ME/CFS (51.2%). This prevalence is considerably higher compared to the rates of suicidal thoughts reported among the general male population in Europe and Switzerland, which range from 2.3% to 14.6% [54,55]. This phenomenon may be attributed to the additional social pressure experienced by men, particularly as the traditional male role revolves around being the main breadwinner and professional activity and career. The increased risk of suicidal thoughts and suicide deaths among individuals with ME/CFS underscores the urgent need for preventive measures and enhanced support in ME/CSF patients, not only in Switzerland but worldwide.

Interestingly, our study revealed a significant association between experiencing suicidal ideation and not having a clinical diagnosis of depression. This suggests that the higher prevalence of suicidal thoughts among individuals with ME/CFS is not explained by possible psychiatric comorbidity, but rather by other external factors. This observation is consistent with other international studies, which similarly found that the majority of patients with suicidal thoughts did not meet the criteria for clinical depression [13]. Our study shed light on several external factors that were associated with suicidal thoughts among ME/CFS patients. These factors included being constantly told that the disease is only psychosomatic (89.5%), experiencing a lack of understanding from others (80.7%), facing stigmatization (76.8%), financial stress (64.9%), and lacking social and medical support (54.4%). These findings align with research conducted in other countries, which similarly highlight inadequate medical treatment, job and relationship losses, challenging interactions with physicians, financial instability and dependence on family as factors contributing to increased suicidal thoughts [56]. It is wildly recognized that individuals with chronic diseases and those experiencing unrelieved chronic pain are at higher risk for suicide [40,[56], [57], [58], [59]]. Our qualitative data revealed instances where the level of desperation and hopelessness for relief was so overwhelming, and the overall quality of life so severely impaired that several of the patients opted to register with in an organized society under Swiss law for physician-assisted suicides (EXIT).

Our study had several limitations that should be taken into consideration. Firstly, there was a potential selection bias as the study only included patients from the ME/CFS association were included, which may not be representative for the entire ME/CFS population in Switzerland.

Given these limitations, further large-scale and in-depth studies are needed to corroborate and expand upon our exploratory findings regarding the mental health impact of ME/CFS. Future research should aim to include diverse and representative samples, utilize validated measurement tools, and account for the full spectrum of disease severity to enhance the validity and generalizability of the results.

Secondly, the study lacked validation scores for mental health measurement. We did not utilize established measurement scales such as the Beck Inventory for Depression and Anxiety [60]. This study was a secondary analysis of a larger project that primarily focused on epidemiology data. Thirdly, the specific criteria used by healthcare providers for diagnosing ME/CFS, such as the CCC (Canadian Consensus Criteria), IOM (Institute of Medicine) criteria, or ICC (International Consensus Criteria), were not known to the researchers, which could introduce variability in the study population.

Finally, there may have been a bias towards individuals with more severe disease manifestations in our study. Since membership in the ME/CFS association may be more common among individuals with greater illness severity, our findings may not fully represent the experiences of individuals who are less severely affected. The inclusion of severely affected bed-bound individuals who may not have been able to complete the questionnaire due to their condition could also contribute to potential bias in our results.

However, our study had strengths as well. The use of self-administrated questionnaires allowed patients to work at their own pace over an extended period, accommodating the needs of homebound patients and capturing a more comprehensive picture of their experiences. We acknowledge that further large scale and in-depth studies on the mental health impact of ME/CFS are warranted to corroborate our exploratory findings.

5. Conclusion

This study highlighted the profound impact of the added mental strain resulting from ME/CFS, primarily stemming from widespread stigmatization, disbelief, a lack of understanding, inadequate medical support and limited disease awareness. In addition to enduring physical distress, patients have to fight with the historical and name-related stigmatization associated with the disease and its mischaracterization as a psychological condition. Our findings provide further support for the notion that comorbid depression observed in certain ME/CFS patients arises as a consequence of the disease rather than being the primary cause of the patient's symptoms as is commonly misdiagnosed. Given the absence of effective treatment for ME/CFS, the condition's severity, and its often life long duration, it is crucial to minimize external factors that exacerbate the mental health burden of patients and increase the risk of suicide.

There is an urgent need, not only in Switzerland but also in many other countries, for enhanced medical and societal support, improved awareness and acceptance among health professionals and society at large, fostering a more supportive and inclusive environment, long-term patient follow up, and a reduction in stigmatization within this under-researched field. This study provides valuable insights that clinicians should be aware of to facilitate the improvement of future care systems for ME/CFS patients.

Funding statement

This study was funded by Swiss TPH and by the Stanley Thomas Johnson Foundation.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Ethics declarations

This study was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Northwestern and Central Switzerland (EKNZ, Switzerland), with the approval number: Basec nr. 2021–01098.

All participants/patients (or their proxies/legal guardians) provided informed consent to participate in the study.

All participants/patients (or their proxies/legal guardians) provided informed consent for the publication of their anonymized case details.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Rahel Susanne König: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. Daniel Henry Paris: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Marc Sollberger: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal analysis. Rea Tschopp: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used Poe software in order to edit some of the language following the revision process. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27031.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press (US); Washington (DC): 2015. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carruthers B.M., Sande M.I. van de, Meirleir K.L. de, Klimas N.G., Broderick G., Mitchell T., Staines D., Powles A.C.P., Speight N., Vallings R., et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: international Consensus criteria. J. Intern. Med. 2011;270:327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nacul L., Authier F.J., Scheibenbogen C., Lorusso L., Helland I.B., Martin J.A., Sirbu C.A., Mengshoel A.M., Polo O., Behrends U., et al. European network on myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (EUROMENE): expert Consensus on the diagnosis, service provision, and care of people with ME/CFS in Europe. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021;57:510. doi: 10.3390/medicina57050510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim E.-J., Ahn Y.-C., Jang E.-S., Lee S.-W., Lee S.-H., Son C.-G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) J. Transl. Med. 2020;18:100. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02269-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jason L.A., Mirin A.A. Updating the National Academy of Medicine ME/CFS prevalence and economic impact figures to account for population growth and inflation. Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior. 2021;9:9–13. doi: 10.1080/21641846.2021.1878716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carruthers B.M., Jain A.K., De Meirleir K.L., Peterson D.L., Klimas N.G., Lerner A.M., Bested A.C., Flor-Henry P., Joshi P., Powles A.C.P., et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols. J. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2003;11:7–115. doi: 10.1300/J092v11n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hvidberg M.F., Brinth L.S., Olesen A.V., Petersen K.D., Ehlers L. The health-related quality of life for patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vyas J., Muirhead N., Singh R., Ephgrave R., Finlay A.Y. Impact of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) on the quality of life of people with ME/CFS and their partners and family members: an online cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Froehlich L., Hattesohl D.B.R., Jason L.A., Scheibenbogen C., Behrends U., Thoma M. Medical care situation of people with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in Germany. Medicina. 2021;57:646. doi: 10.3390/medicina57070646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunnquist M., Nicholson L., Jason L.A., Friedman K.J. Access to medical care for individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome: a call for centers of excellence. Mod. Clin. Med. Res. 2017;1:28–35. doi: 10.22606/mcmr.2017.11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geraghty K., Jason L., Sunnquist M., Tuller D., Blease C., Adeniji C. The ‘cognitive behavioural model’ of chronic fatigue syndrome: critique of a flawed model. Health Psychol. Open. 2019;6 doi: 10.1177/2055102919838907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tschopp R., König R.S., Rejmer P., Paris D.H. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences; 2023. Health System Support Among Patients with ME/CFS in Switzerland. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McManimen S.L., McClellan D., Stoothoff J., Jason L.A. Effects of unsupportive social interactions, stigma, and symptoms on patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Community Psychol. 2018;46:959–971. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fennell P.A., Dorr N., George S.S. Elements of suffering in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: the experience of loss, grief, stigma, and trauma in the severely and very severely affected. Healthcare. 2021;9:553. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9050553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Looper K.J., Kirmayer L.J. Perceived stigma in functional somatic syndromes and comparable medical conditions. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004;57:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickson A., Knussen C., Flowers P. Stigma and the delegitimation experience: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of people living with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychol. Health. 2007;22:851–867. doi: 10.1080/14768320600976224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu L., Elliott M., Stein E., Jason L.A. Identifying and managing suicidality in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9:629. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9060629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakin L., Davis B.E., Binns C.C., Currie K.M., Rensel M.R. Comprehensive approach to management of multiple sclerosis: addressing invisible symptoms-A narrative review. Neurol. Ther. 2021 Jun;10(1):75–98. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00239-2. Epub 2021 Apr 20. PMID: 33877583; PMCID: PMC8057008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hündersen F., Forst S., Kasten E. Neuropsychiatric and psychological symptoms in patients with Lyme disease: a study of 252 patients. Healthcare. 2021;9(6):733. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9060733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palomo-Toucedo I.C., Leon-Larios F., Reina-Bueno M., Vázquez-Bautista M.D.C., Munuera-Martínez P.V., Domínguez-Maldonado G. Psychosocial influence of ehlers-danlos syndrome in daily life of patients: a qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020 Sep 3;17(17):6425. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176425. PMID: 32899328; PMCID: PMC7503231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newton J.L., Okonkwo O., Sutcliffe K., Seth A., Shin J., Jones D.E.J. Symptoms of autonomic dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. QJM. 2007;100:519–526. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papadopoulos A.S., Cleare A.J. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012;8:22–32. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wirth K.J., Scheibenbogen C., Paul F. An attempt to explain the neurological symptoms of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2021;19:471. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-03143-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenu E.W., van Driel M.L., Staines D.R., Ashton K.J., Ramos S.B., Keane J., Klimas N.G., Marshall-Gradisnik S.M. Immunological abnormalities as potential biomarkers in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. J. Transl. Med. 2011;9:81. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sotzny F., Blanco J., Capelli E., Castro-Marrero J., Steiner S., Murovska M., Scheibenbogen C. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome – evidence for an autoimmune disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018;17:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steiner S., Becker S.C., Hartwig J., Sotzny F., Lorenz S., Bauer S., Löbel M., Stittrich A.B., Grabowski P., Scheibenbogen C. Autoimmunity-related risk variants in PTPN22 and CTLA4 are associated with ME/CFS with infectious onset. Front. Immunol. 2020:11. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giloteaux L., Goodrich J.K., Walters W.A., Levine S.M., Ley R.E., Hanson M.R. Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome. 2016;4 doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0171-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lupo G.F.D., Rocchetti G., Lucini L., Lorusso L., Manara E., Bertelli M., Puglisi E., Capelli E. Potential role of microbiome in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelits (CFS/ME) Sci. Rep. 2021;11:7043. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86425-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.König R.S., Albrich W.C., Kahlert C.R., Bahr L.S., Löber U., Vernazza P., Scheibenbogen C., Forslund S.K. The gut microbiome in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) Front. Immunol. 2022;12:5616. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.628741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong C.W., McGregor N.R., Lewis D.P., Butt H.L., Gooley P.R. Metabolic profiling reveals anomalous energy metabolism and oxidative stress pathways in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Metabolomics. 2015;11:1626–1639. doi: 10.1007/s11306-015-0816-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris G., Maes M. Mitochondrial dysfunctions in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome explained by activated immuno-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways. Metab. Brain Dis. 2014;29:19–36. doi: 10.1007/s11011-013-9435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Missailidis D., Annesley S.J., Allan C.Y., Sanislav O., Lidbury B.A., Lewis D.P., Fisher P.R. An isolated complex V inefficiency and dysregulated mitochondrial function in immortalized lymphocytes from ME/CFS patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1074. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tschopp R, König RS, Protazi R, Paris D. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): a Preliminary Survey Among Patients in Switzerland. Heliyon.In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Baken D.M., Harvey S.T., Bimler D.L., Ross K.J. Stigma in myalgic encephalomyelitis and its association with functioning. Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior. 2018;6:30–40. doi: 10.1080/21641846.2018.1419553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pantelic M., Ziauddeen N., Boyes M., O'Hara M.E., Hastie C., Alwan N.A. 2022. Long Covid Stigma: Estimating Burden and Validating Scale in a UK-based Sample. 2022.05.26.22275585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brittain E., Muirhead N., Finlay A.Y., Vyas J. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): major impact on lives of both patients and family members. Medicina. 2021;57:43. doi: 10.3390/medicina57010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.EFNA . 2020. Survey on Stigma and Neurological Disorder.https://www.efna.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/SurveyReport2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tworek Grace, Thompson Nicolas R., Kane Alexa, Sullivan Amy B. The impact of stigma on perceived quality of life and experience of anxiety and depression in individuals diagnosed with MS. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2023;72 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2023.104591. ISSN 2211-0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penner Iris-Katharina, McDougall Fiona, Michelle Brown T., Slota Christina, Doward Lynda, Julian Laura, Belachew Shibeshih, Miller Deborah. Exploring the impact of fatigue in progressive multiple sclerosis: a mixed-methods analysis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2020;43 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102207. ISSN 2211-0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newton-John T.R.O. Negotiating the maze: risk factors for suicidal behavior in chronic pain patients. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18:447. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0447-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Mental health and chronic diseases, CDC fact sheet. 2012. https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/tools-resources/pdfs/issue-brief-no-2-mental-health-and-chronic-disease.pdf (Accessed 15 December 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krupp L.B., Sliwinski M., Masur D.M., Friedberg F., Coyle P.K. Cognitive functioning and depression in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 1994;51:705–710. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540190089021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeJean D., Giacomini M., Vanstone M., Brundisini F. Patient experiences of depression and anxiety with chronic disease: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2013 Sep 1;13(16):1–33. PMID: 24228079; PMCID: PMC3817854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bijl R.V., Ravelli A., van Zessen G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the general population: results of The Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS) Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1998;33:587–595. doi: 10.1007/s001270050098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobi F., Wittchen H.-U., Holting C., Höfler M., Pfister H., Müller N., Lieb R. Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS) Psychol. Med. 2004;34:597–611. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schuler D., Tuch A., Peter C. 2020. Psychische Gesundheit in der Schweiz.file:///C:/Users/rahel/Downloads/Obsan%20Bericht%2015_20_Psychische%20Gesundheit%20in%20der%20Schweiz.%20Monitoring%202020..pdf [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patten S.B., Berzins S., Metz L.M. Challenges in screening for depression in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2010;16:1406–1411. doi: 10.1177/1352458510377770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kingdon C.C., Bowman E.W., Curran H., Nacul L., Lacerda E.M. Functional status and well-being in people with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome compared with people with multiple sclerosis and healthy controls. PharmacoEconomics Open. 2018;2:381–392. doi: 10.1007/s41669-018-0071-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fuller-Thomson E., Nimigon J. Factors associated with depression among individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome: findings from a nationally representative survey. Fam. Pract. 2008;25:414–422. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffith J.P., Zarrouf F.A. A systematic review of chronic fatigue syndrome: don't assume it's depression. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2008;10:120–128. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v10n0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Constant E.L., Adam S., Gillain B., Lambert M., Masquelier E., Seron X. Cognitive deficits in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome compared to those with major depressive disorder and healthy controls. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2011;113:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson M.L., Cotler J., Terman J.M., Jason L.A. Risk factors for suicide in chronic fatigue syndrome. Death Stud. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1776789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jason L.A., Corradi K., Gress S., Williams S., Torres-Harding S. Causes of death among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Health Care Women Int. 2006;27(7):615–626. doi: 10.1080/07399330600803766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peter C., Tuch A. Suizidgedanken und Suizidversuche in der Schweizer Bevölkerung (Obsan Bulletin 7/2019) Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium (Obsan) 2019 https://www.obsan.admin.ch/de/publikationen/2019-suizidgedanken-und-suizidversuche-der-schweizer-bevoelkerung [Google Scholar]

- 55.Casey P.R., Dunn G., Kelly B.D., Birkbeck G., Dalgard O.S., Lehtinen V., Britta S., Ayuso-Mateos J.L., Dowrick C., Group O. Factors associated with suicidal ideation in the general population: five-centre analysis from the ODIN study. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2006;189:410–415. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Devendorf A.R., McManimen S.L., Jason L.A. Suicidal ideation in non-depressed individuals: the effects of a chronic, misunderstood illness. J. Health Psychol. 2018;25:2106–2117. doi: 10.1177/1359105318785450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pederson C.L., Gorman-Ezell K., Hochstetler-Mayer G. Invisible illness increases risk of suicidal ideation: the role of social workers in preventing suicide. Health Soc. Work. 2017;42:183–186. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlx029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ratcliffe G.E., Enns M.W., Belik S.-L., Sareen J. Chronic pain conditions and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: an epidemiologic perspective. Clin. J. Pain. 2008;24:204–210. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31815ca2a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hassett A.L., Aquino J.K., Ilgen M.A. The risk of suicide mortality in chronic pain patients. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18:436. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beck A.T., Ward C.H., Menselson M., Mock J., Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.