Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the course of interstitial lung disease (ILD) and the effects of nintedanib in patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (lcSSc).

Methods

In the SENSCIS trial, patients with SSc-ILD were randomized to receive nintedanib or placebo. Patients who completed the SENSCIS trial were eligible to enter SENSCIS-ON, in which all patients received open-label nintedanib.

Results

Among 277 patients with lcSSc treated in the SENSCIS trial, the rate (s.e.) of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC; ml/year) over 52 weeks was −74.5 (19.2) in the placebo group and −49.1 (19.8) in the nintedanib group (difference: 25.3 [95% CI −28.9, 79.6]). Among 249 patients with data at week 52, mean (s.e.) change in FVC at week 52 was −86.4 (21.1) ml in the placebo group and −39.1 (22.2) ml in the nintedanib group. Among 183 patients with lcSSc who participated in SENSCIS-ON and had data at week 52, mean (s.e.) change in FVC from baseline to week 52 of SENSCIS-ON was −41.5 (24.0) ml in patients who took placebo in the SENSCIS trial and initiated nintedanib in SENSCIS-ON and −45.1 (19.1) ml in patients who took nintedanib in the SENSCIS trial and continued it in SENSCIS-ON.

Conclusion

Patients with lcSSc may develop progressive fibrosing ILD. By targeting pulmonary fibrosis, nintedanib slows decline in lung function in patients with lcSSc and ILD.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov), NCT02597933 and NCT03313180

Keywords: antifibrotic agents, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary function tests, scleroderma, systemic

Video Abstract

A video abstract is available for this article and can be viewed at https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kead280.

Rheumatology key messages.

Patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (lcSSc) may develop pulmonary fibrosis.

Nintedanib slows the decline in lung function in patients with lcSSc and pulmonary fibrosis.

Prompt treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in patients with lcSSc is important to preserve lung function.

Introduction

SSc is a rare and heterogeneous autoimmune disease characterized by immune dysregulation, microvascular damage and progressive fibrosis of the skin and internal organs [1]. The majority of patients with SSc have the limited cutaneous form of the disease (lcSSc) [2–5], which is defined by skin fibrosis limited to the hands, forearms, face and feet [6]. Although interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) is more common in patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc), a substantial proportion of patients with lcSSc develop SSc-ILD [2–4, 7–9]. In an analysis of over 8000 patients with lcSSc in the EUSTAR database, 35% of patients had ILD on high-resolution CT (HRCT) or X-ray [3]. In a Spanish registry, ILD was reported as the cause of death in 12% of patients with lcSSc [8].

Clinical trials of investigational therapies for SSc often focus on patients with early dcSSc as this is the population that has the highest risk of organ manifestations with significant progression. Some recent trials of investigational therapies for SSc enrolled only patients with dcSSc and risk factors for progression [10–12]. Patients with lcSSc have been under-represented in clinical trials, limiting the data available on the clinical course and treatment of these patients [13]. This is important, as patients with lcSSc are at risk of developing ILD and of ILD progression [2–4, 7, 14].

Nintedanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties that target the progression of pulmonary fibrosis [15]. Nintedanib has been licenced for the treatment of SSc-ILD, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and other chronic fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype. In the SENSCIS trial in patients with SSc-ILD, nintedanib reduced the rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) (ml/year) over 52 weeks by 44% vs placebo [16]. The SENSCIS trial enrolled a broad population of patients with SSc-ILD, including patients with lcSSc. Thus, the SENSCIS trial and its open-label extension, SENSCIS-ON, provide an opportunity to investigate the course of ILD and the effects of treatment specifically among patients with lcSSc.

Methods

Trial designs

The design of the SENSCIS trial (NCT02597933) has been described and the protocol is publicly available [16]. Briefly, patients had SSc with first non-Raynaud symptom in the prior ≤7 years, an extent of fibrotic ILD ≥10% on HRCT (based on assessment of the whole lung), FVC ≥40% predicted, and diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) 30–89% predicted. Patients taking prednisone ≤10 mg/day and/or stable therapy with mycophenolate or methotrexate for ≥6 months were allowed to participate. Patients were randomized to receive nintedanib 150 mg twice daily (bid) or placebo stratified by the presence of anti-topoisomerase I antibody (ATA). Patients remained on blinded treatment until the last patient had reached week 52 but for ≤100 weeks.

Patients who completed the SENSCIS trial on treatment and attended a follow-up visit 28 days later, or who completed a drug–drug interaction study of nintedanib plus oral contraceptive in female patients with SSc-ILD, in which nintedanib was given for ∼14–28 days [17], were eligible to enter SENSCIS-ON (NCT03313180), in which all patients received open-label nintedanib [18]. In both the parent trials and in SENSCIS-ON, dose reductions to 100 mg bid and treatment interruptions were permitted to manage adverse events.

The trials complied with the protocol, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice of the International Conference on Harmonisation. The trials were approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board at every site. Patients provided written informed consent before trial entry.

Outcomes

We report analyses in patients with lcSSc in SENSCIS and SENSCIS-ON. Patients were classified as having lcSSc or dcSSc by the investigators at screening of the parent trial. There were no protocol-defined criteria for the classification of lcSSc or dcSSc, but the investigators were trained on how to obtain a modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) and informed how to classify patients as having lcSSc or dcSSc.

In the SENSCIS trial, we analysed the rate of decline in FVC (ml/year) over 52 weeks in all patients with lcSSc and in subgroups by baseline characteristics; the change from baseline in FVC (ml) at week 52; the proportions of patients with relative declines in FVC (ml) >5% and >10% and absolute declines in FVC >5% and >10% predicted at week 52; the time to absolute decline in FVC ≥10% predicted or death over 52 weeks; and the change in St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score [19] at week 52. In SENSCIS-ON, we analysed the change from baseline of SENSCIS-ON in FVC (ml) at week 52 and the proportions of patients with relative declines in FVC (ml) >5% and >10% and absolute declines in FVC >5% and >10% predicted at week 52.

Analyses

Except for the rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks in subgroups by baseline characteristics in the SENSCIS trial, the data in patients with lcSSc came from analyses performed in subgroups based on SSc subtype (lcSSc vs dcSSc) and the models included effects for SSc subtype. The rate of decline in FVC (ml/year) over 52 weeks in patients with lcSSc in the SENSCIS trial was analysed using a linear mixed-effects regression model (with random slopes and intercepts) with fixed categorical effects of ATA status and sex, fixed continuous effects of baseline FVC (ml), age and height and including baseline-by-time, treatment-by-subgroup (lcSSc vs dcSSc) and treatment-by-subgroup-by-time interaction terms. A similar model was used to assess the rate of decline in FVC (ml/year) over 52 weeks in subgroups by baseline characteristics, but with each baseline characteristic (instead of lcSSc vs dcSSc) included as the subgroup effect. Interaction tests were applied to assess potential heterogeneity in the effect of nintedanib among the subgroups, with no adjustment for multiple testing. The change in FVC (ml) at week 52 was based on observed data from patients with data at week 52 and is presented descriptively.

The proportions of patients with relative declines in FVC (ml) >5% and >10% and absolute declines in FVC >5% and >10% predicted at week 52 of the SENSCIS trial were analysed using a logistic regression model including terms for treatment, ATA status, subgroup (lcSSc vs dcSSc) and treatment-by-subgroup interaction. Missing values were imputed using a worst value carried forward approach. Odds ratios were estimated for the effect of treatment. The proportions of patients with relative declines in FVC (ml) >5% and >10% and absolute declines in FVC >5% and >10% predicted at week 52 of the SENSCIS-ON trial were based on observed data from patients with data at week 52 and are presented descriptively.

The time to absolute decline in FVC ≥10% predicted or death in the SENSCIS trial was assessed using a Cox regression model with terms for treatment, ATA status, subgroup (lcSSc vs dcSSc) and treatment-by-subgroup interaction. Change in SGRQ total score at week 52 of the SENSCIS trial was assessed using a mixed model for repeated measures with fixed categorical effects of ATA status, visit and treatment-by-subgroup (lcSSc vs dcSSc)-by-visit interaction and a fixed continuous effect of baseline SGRQ total score-by-visit. Data on adverse events in both trials are presented descriptively.

Analyses of data from SENSCIS-ON were performed in patients who had received nintedanib in the SENSCIS trial (‘continued nintedanib’ group) and in patients who received placebo in the SENSCIS trial and initiated nintedanib in SENSCIS-ON or who had received nintedanib for a short period in the drug–drug interaction study (‘initiated nintedanib’ group). These analyses were conducted post hoc except for the following analyses of data from the SENSCIS trial by SSc subtype: rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks, change in FVC (ml) at week 52, and adverse events.

Results

Patients with lcSSc in the SENSCIS trial

A total of 277 patients with lcSSc were treated in the SENSCIS trial (135 with nintedanib, 142 with placebo). Most patients (73.6%) were female. At baseline, mean (S.D.) age was 56.2 (11.7) years and mean time since first non-Raynaud symptom was 3.1 (1.7) years. Modified Rodnan skin score was 5.2 (4.1), 78.0% of patients were ANA positive, 51.3% were ATA positive and 29.2% had elevated inflammatory markers (based on C-reactive protein and/or platelet levels) (Table 1). The mean extent of fibrotic ILD on HRCT was 35.7 (21.2)%. Mean FVC was 74.8 (16.8)% predicted. Approximately 45% of patients were taking mycophenolate and 45% were taking glucocorticoids (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis and interstitial lung disease in the SENSCIS trial (n = 277)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 56.2 (11.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 204 (73.6) |

| Body mass index, mean (s.d.), kg/m2 | 26.3 (4.9) |

| Race, n (%)a | |

| White | 182 (65.7) |

| Asian | 78 (28.2) |

| Black/African American | 12 (4.3) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 2 (0.8) |

| Time since onset of first non-Raynaud symptom, mean (s.d.), years | 3.1 (1.7) |

| ANA positive, n (%)b | 216 (78.0) |

| ATA positive, n (%)b | 142 (51.3) |

| ARA positive, n (%)b | 22 (7.9) |

| ACA positive, n (%)b | 28 (10.1) |

| mRSS, mean (s.d.) | 5.2 (4.1) |

| Elevated inflammatory markers, n (%)c | 81 (29.2) |

| Extent of fibrotic ILD on HRCT, mean (s.d.), %d | 35.7 (21.2) |

| Presence of honeycombing on HRCT (yes/no), n (%) | 49 (17.7) |

| Presence of ground glass opacity on HRCT (yes/no), n (%) | 224 (80.9) |

| Presence of reticulation on HRCT (yes/no), n (%) | 257 (92.8) |

| FVC, mean (s.d.), % predicted | 74.8 (16.8) |

| DLCO, mean (s.d.), % predictede | 52.6 (14.1) |

| Cough, n (%)f | 219 (79.1) |

| Dyspnoea, n (%)f | 194 (70.0) |

| Internal organ involvement, n (%)g | |

| Peripheral vascular | 266 (96.0) |

| Upper gastrointestinal | 194 (70.0) |

| Cardiovascular | 124 (44.8) |

| Lower gastrointestinal | 107 (38.6) |

| Joint | 82 (29.6) |

| Muscular | 63 (22.7) |

| Taking mycophenolate, n (%) | 126 (45.5) |

Data from patients who selected one race. Four patients ticked >1 box.

Based on historical (local laboratory) information, as reported on the SSc-related medical history page of the case report form.

C-reactive protein ≥6 mg/l and/or platelets ≥330 × 109/l; data were missing from 23 patients.

Assessed in whole lung to nearest 5% by central review. Pure (non-fibrotic) ground glass opacity was not included.

Corrected for haemoglobin; data were missing from two patients.

Based on responses to SGRQ. Patients who ticked boxes for ‘most days a week’, ‘several days a week’ or ‘a few days a month’ in response to the question ‘Over the last month, I have coughed…’ or ‘Over the last month, I have had shortness of breath…’ were counted as having cough/dyspnoea.

Based on SSc-related medical history as reported in case report form.

ARA: anti-RNA polymerase III antibody; ATA: anti-topoisomerase I antibody; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; FVC: forced vital capacity; HRCT: high-resolution CT; mRSS: modified Rodnan skin score; SGRQ: St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

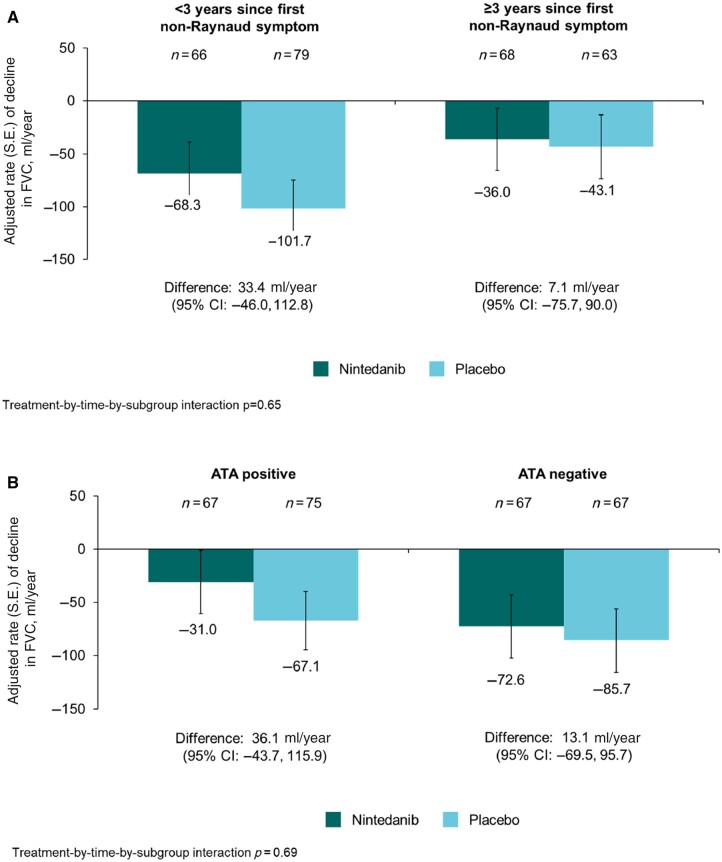

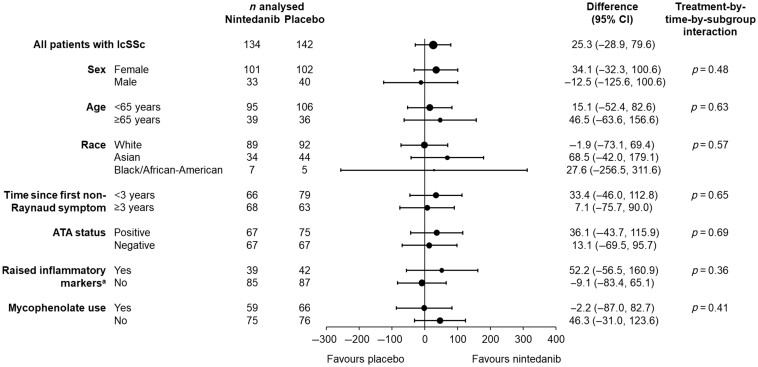

The rate (s.e.) of decline in FVC over 52 weeks in patients with lcSSc was −74.5 (19.2) ml/year in the placebo group and −49.1 (19.8) ml/year in the nintedanib group (difference: 25.3 [95% CI −28.9, 79.6] ml/year). Thus nintedanib reduced the rate of decline in FVC (ml/year) over 52 weeks by 34% vs placebo. In the placebo group, the rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks in patients with lcSSc was numerically greater in patients who had <3 years since first non-Raynaud symptom, were ATA negative, had raised inflammatory markers, or were not taking mycophenolate at baseline (Fig. 1). No heterogeneity was detected in the effect of nintedanib vs placebo on reducing the rate of FVC decline across subgroups based on baseline characteristics (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) (ml/year) over 52 weeks in patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (lcSSc) and interstitial lung disease in the SENSCIS trial in subgroups by (A) time since first non-Raynaud symptom, (B) anti-topoisomerase I antibody (ATA) status, (C) raised inflammatory markers, and (D) use of mycophenolate at baseline

Figure 2.

Rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) (ml/year) over 52 weeks in patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (lcSSc) and interstitial lung disease in subgroups by baseline characteristics in the SENSCIS trial. aC-reactive protein ≥6 mg/l and/or platelets ≥330 × 109/l. ATA: anti-topoisomerase I antibody

Figure 1.

(Continued)

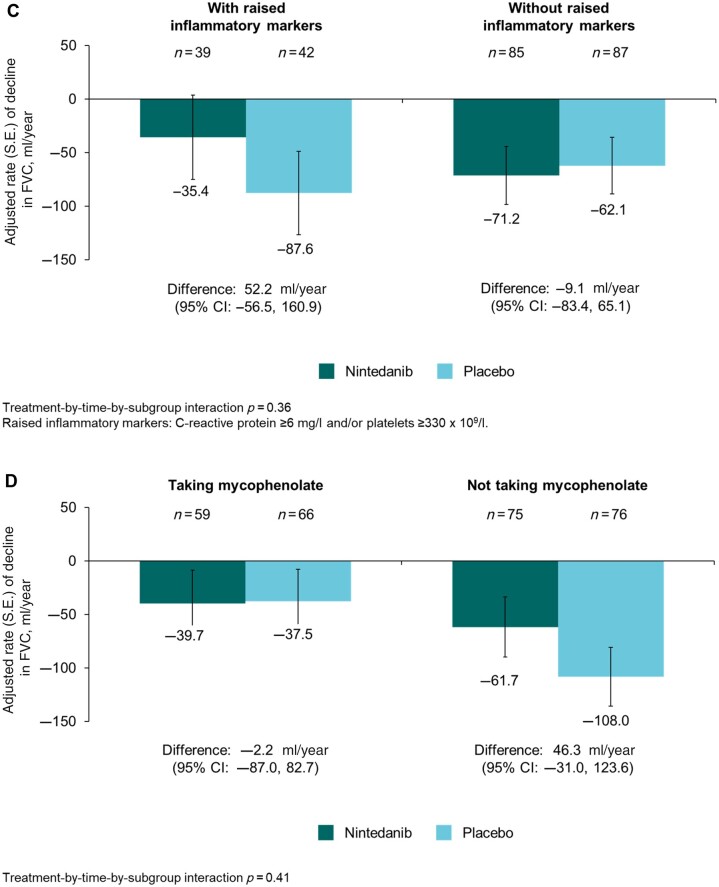

The mean (s.e.) change in FVC at week 52 was −39.1 (22.2) ml in the nintedanib group and −86.4 (21.1) ml in the placebo group (Fig. 3). The proportions of patients with relative declines in FVC (ml) >5% and >10% and absolute declines in FVC >5% and >10% predicted at week 52 were similar or lower in patients who received nintedanib vs placebo (Table 2). Over 52 weeks, an absolute decline in FVC ≥10% predicted or death occurred in 12.6% of patients in the nintedanib group and 21.8% of patients in the placebo group (hazard ratio: 0.55 [95% CI 0.30, 0.99]). The adjusted mean (s.e.) change in SGRQ total score at week 52 was 1.1 (1.3) in the nintedanib group and 0.5 (1.2) in the placebo group (difference: 0.6 [95% CI −2.9, 4.1]).

Figure 3.

Change from baseline in forced vital capacity (FVC) (ml) at week 52 in patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis and interstitial lung disease in the SENSCIS and SENSCIS-ON trials. Based on patients with data at week 52

Table 2.

Absolute and relative declines in FVC at week 52 in patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis and interstitial lung disease in the SENSCIS trial

| Nintedanib | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 134) | (n = 142) | ||

| Relative decline in FVC (ml) >5%, n (%) | 41 (30.6) | 57 (40.1) | |

| Odds ratio vs placebo (95% CI) | 0.66 (0.40, 1.08) | ||

| Relative decline in FVC (ml) >10%, n (%) | 19 (14.2) | 23 (16.2) | |

| Odds ratio vs placebo (95% CI) | 0.86 (0.44, 1.66) | ||

| Absolute decline in FVC >5% predicted, n (%) | 25 (18.7) | 40 (28.2) | |

| Odds ratio vs placebo (95% CI) | 0.59 (0.33, 1.04) | ||

| Absolute decline in FVC >10% predicted, n (%) | 12 (9.0) | 12 (8.5) | |

| Odds ratio vs placebo (95% CI) | 1.06 (0.46, 2.45) | ||

Based on logistic regression. Missing values were imputed using a worst value carried forward approach. FVC: forced vital capacity.

The most frequent adverse event was diarrhoea, which was reported in 77.0% and 30.3% of the nintedanib and placebo groups, respectively, over 52 weeks (Table 3). Over 52 weeks, 55 patients (40.7%) in the nintedanib group and five patients (3.5%) in the placebo group had ≥1 dose reduction and 51 patients (37.8%) in the nintedanib group and 15 patients (10.6%) in the placebo group had ≥1 treatment interruption. Adverse events led to treatment discontinuation in 18.5% and 8.5% of patients in the nintedanib and placebo groups, respectively.

Table 3.

Adverse events in patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis and interstitial lung disease in the SENSCIS and SENSCIS-ON trials

| SENSCIS |

SENSCIS-ON |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nintedanib | Placebo | Continued nintedanib | Initiated nintedanib | |

| (n = 135) | (n = 142) | (n = 98) | (n = 127) | |

| Any adverse event(s) | 134 (99.3) | 138 (97.2) | 96 (98.0) | 125 (98.4) |

| Most frequent adverse eventsa | ||||

| Diarrhoea | 104 (77.0) | 43 (30.3) | 70 (71.4) | 89 (70.1) |

| Nausea | 45 (33.3) | 20 (14.1) | 19 (19.4) | 32 (25.2) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 21 (15.6) | 29 (20.4) | 18 (18.4) | 23 (18.1) |

| Vomiting | 33 (24.4) | 16 (11.3) | 15 (15.3) | 31 (24.4) |

| Cough | 17 (12.6) | 25 (17.6) | 13 (13.3) | 8 (6.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 18 (13.3) | 19 (13.4) | 13 (13.3) | 18 (14.2) |

| Skin ulcer | 11 (8.1) | 18 (12.7) | 11 (11.2) | 14 (11.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 12 (8.9) | 16 (11.3) | 2 (2.0) | 12 (9.4) |

| Weight decreased | 20 (14.8) | 7 (4.9) | 7 (7.1) | 10 (7.9) |

| Headache | 17 (12.6) | 8 (5.6) | 8 (8.2) | 10 (7.9) |

| Fatigue | 16 (11.9) | 8 (5.6) | 3 (3.1) | 10 (7.9) |

| Hepatic adverse eventsb | 23 (17.0) | 3 (2.1) | 15 (15.3) | 24 (18.9) |

| Adverse event(s) leading to treatment discontinuation | 25 (18.5) | 12 (8.5) | 3 (3.1) | 21 (16.5) |

| Adverse event(s) leading to dose reduction | 47 (34.8) | 5 (3.5) | 17 (17.3) | 62 (48.8) |

| Serious adverse event(s)c | 30 (22.2) | 26 (18.3) | 22 (22.4) | 31 (24.4) |

| Fatal adverse event | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.1) | 2 (2.0) | 0 |

Data are n (%) of patients with ≥1 such event reported over 52 weeks (or until 28 days after last trial drug intake for patients who discontinued trial drug before week 52).

Adverse events were coded according to preferred terms in MedDRA. Events reported in >10% of patients in any of the groups shown are listed.

Based on the standardized MedDRA query ‘liver related investigations, signs and symptoms’ (broad definition).

Adverse events that resulted in death, were life-threatening, resulted in hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization, resulted in persistent or clinically significant disability or incapacity, were a congenital anomaly or birth defect, or were deemed serious for any other reason. MedDRA: Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

Patients with lcSSc in SENSCIS-ON

A total of 225 patients with lcSSc participated in SENSCIS-ON. Baseline characteristics at entry into SENSCIS-ON were generally similar between patients who continued and initiated nintedanib (Supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online).

The mean (s.e.) change in FVC from baseline to week 52 of SENSCIS-ON was −45.1 (19.1) ml in the continued nintedanib group, −41.5 (24.0) ml in the initiated nintedanib group and −43.3 (15.3) ml in all patients (Fig. 3). Changes in FVC over 52 weeks in SENSCIS and SENSCIS-ON are shown together in Supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online. The proportions of patients with relative declines in FVC (ml) >5% and >10% and absolute declines in FVC >5% and >10% predicted at week 52 of SENSCIS-ON were similar between the continued nintedanib group and the initiated nintedanib group (Supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online).

Diarrhoea was the most frequent adverse event over 52 weeks in patients with lcSSc in SENSCIS-ON, reported in 71.4% of patients who continued nintedanib and 70.1% who initiated nintedanib (Table 3). Over 52 weeks, 18 patients (18.4%) who continued nintedanib and 62 patients (48.8%) who initiated nintedanib had ≥1 dose reduction and 27 patients (27.6%) who continued nintedanib and 57 patients (44.9%) who initiated nintedanib had ≥1 treatment interruption.

Discussion

The SENSCIS and SENSCIS-ON trials provided an opportunity to investigate the course of ILD in patients with lcSSc. The patients with lcSSc and ILD enrolled in the SENSCIS trial had marked fibrosis on HRCT and considerable impairment in lung function. Despite this, ∼30% of these patients did not have dyspnoea and 20% did not have cough. This finding, which is consistent with analyses of the overall trial population [20], highlights that respiratory symptoms may be a late presentation of SSc-ILD, and supports the screening of all patients with SSc for ILD at diagnosis, including those with lcSSc and without respiratory symptoms, as recommended by experts [21].

There is some evidence to suggest that the risk of ILD progression is greater in patients with dcSSc than in those with lcSSc [7, 14], although this has not been observed in all studies [3, 22]. In the SENSCIS trial, the rate of decline in FVC in the placebo group was numerically greater in patients with dcSSc than lcSSc [23]. However, the patients with lcSSc and ILD still showed substantial loss of FVC, with a mean loss of 86 ml over 52 weeks, and an absolute decline in FVC >5% predicted observed in 30% of patients in the placebo group. Analyses of the EUSTAR database have also shown that a substantial proportion of patients with lcSSc and ILD experience progression over 1–5 years [3, 14, 24]. These findings indicate that patients with lcSSc may develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis soon after diagnosis of SSc, highlighting the importance of close monitoring of patients with SSc-ILD to ensure that progression can be identified and treated early [21].

About half of the patients with lcSSc in the SENSCIS trial were ATA positive. This a higher proportion than observed in registries and nationwide cohorts of patients with SSc [3–5, 24, 25] and SSc-ILD [8]. This might reflect a bias for enrolment into a clinical trial of patients with lcSSc whose ILD was severe or progressing, or who were deemed at greater risk of progression. Among patients with lcSSc, we detected no heterogeneity in the effect of nintedanib on reducing the rate of FVC decline between patients who were ATA-positive vs ATA-negative, consistent with analyses of the overall trial population [23]. About 22% of the patients with lcSSc and ILD in the SENSCIS trial were ANA-negative, a higher proportion than the 4–12% of patients with lcSSc reported to be ANA-negative in registries and other cohorts of patients with SSc [2–4, 24, 25] and SSc-ILD [8]. The reason for this observation is unclear.

Similar to the overall SENSCIS trial population, about half of the patients with lcSSc in the SENSCIS trial were taking mycophenolate at baseline. We detected no heterogeneity in the effect of nintedanib on reducing the rate of FVC decline between patients with lcSSc taking and not taking mycophenolate, consistent with analyses in the overall trial population [26]. Also consistent with analyses of the overall trial population [16, 23], among patients with lcSSc, no heterogeneity was detected in the effect of nintedanib on reducing the rate of FVC decline in subgroups based on sex, age or race, suggesting that the relative effect of nintedanib was consistent across these subgroups.

Over 52 weeks of the SENSCIS trial, there was no meaningful change in mean SGRQ total score in either treatment group [16]. Results observed in the subgroup of patients with lcSSc were consistent with the overall population. However, previous analyses of data from the SENSCIS trial suggest that meaningful changes in patient-reported outcomes could be detected in patients with large changes in FVC over 52 weeks, suggesting that slowing decline in lung function in patients with SSc-ILD may help to preserve quality of life in the long term [27].

Among patients with lcSSc, the change in FVC over 52 weeks of SENSCIS-ON was similar to the change in FVC over 52 weeks observed in patients with lcSSc who received nintedanib in the SENSCIS trial (−43.3 and −39.1 ml, respectively), suggesting a sustained benefit of nintedanib on slowing the progression of SSc-ILD. Consistent with the data from the overall population [18], the adverse event profile of nintedanib in patients with lcSSc over longer-term use in SENSCIS-ON was consistent with that reported over 52 weeks in the SENSCIS trial. These data are important given the limited longitudinal data on the treatment of patients with lcSSc-ILD.

Strengths of these analyses include the randomized placebo-controlled design of the SENSCIS trial, the large number of patients who participated in its open-label extension, and the standardized collection of data in the setting of clinical trials. Limitations include that the SENSCIS and SENSCIS-ON trials were not powered to assess outcomes in patients with lcSSc, that there was no placebo comparator in SENSCIS-ON, and that not all patients in the SENSCIS trial continued in SENSCIS-ON. The classification of dcSSc and lcSSc may vary across centres and regions and there may have been some misclassification.

In conclusion, these analyses of data from the SENSCIS trial indicate that patients with lcSSc may develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis within a few years of diagnosis of SSc. Over 52 weeks, the rate of decline in FVC in patients with lcSSc and ILD was lower in patients treated with nintedanib than placebo, with adverse events that could be managed by most patients. These findings support the screening of patients with lcSSc for ILD and the importance of prompt initiation of treatment in patients with lcSSc-ILD to preserve lung function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in the SENSCIS and SENSCIS-ON trials. The SENSCIS and SENSCIS-ON trials were supported by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH (BI). The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The authors did not receive payment for development of this manuscript. Elizabeth Ng and Wendy Morris of FleishmanHillard, London, UK, provided medical writing assistance, which was contracted and funded by BI. BI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Contributor Information

Yannick Allanore, Department of Rheumatology, Paris Cité University, APHP, Cochin Hospital, Paris, France.

Dinesh Khanna, Department of Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Vanessa Smith, Department of Rheumatology and Internal Medicine, Ghent University Hospital and Unit for Molecular Immunology and Inflammation, VIB Inflammation Research Center (IRC), Ghent, Belgium.

Martin Aringer, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine III, University Medical Center and Faculty of Medicine Carl Gustav Carus, Dresden, Dresden, TU, Germany.

Anna-Maria Hoffmann-Vold, Department of Rheumatology, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway.

Masataka Kuwana, Department of Allergy and Rheumatology, Nippon Medical School Graduate School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Peter A Merkel, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Informatics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Christian Stock, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Biberach, Germany.

Steven Sambevski, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany.

Christopher P Denton, Division of Medicine, Centre for Rheumatology and Connective Tissue Diseases, University College London, London, UK.

SENSCIS Trial Investigators:

M Bergna, G Casado, P Mannucci Walter, S Proudman, W Stevens, V Thakkar, L Troy, J Loeffler-Ragg, H Olschewski, B André, B Bondue, F Houssiau, V Smith, W Wuyts, V Azevedo, S Johnson, E Keystone, N Khalidi, M Levesque, R Maturana Rozas, A Silva Orellana, C Huang, J Li, Z Jiang, Y Liu, W Xiao, J Xu, X Zeng, Y Zheng, H Zou, R Becvar, H Madsen, K Søndergaard, M Kilpeläinen, M Myllärniemi, C Agard, Y Allanore, A Bourdin, V Cottin, B Crestani, E Diot, S Dominique, E Hachulla, S Jouneau, S Leroy, H Nunes, G Prevot, B Wallaert, L Wemeau, M Aringer, B Bewig, S Blaas, J Distler, J Ehrchen, R Ewert, S Gläser, J Henes, N Hunzelmann, R König, I Kötter, M Kreuter, A Prasse, H Schulze-Koops, P Sfikakis, P Vlachoyiannopoulos, G Losonczy, D Behera, H J Gayathri Devi, J Kadel, M Kawedia, D Kumar, U Kumar, R Lokhande, A Malpani, M Mohan, A Nalawade, U Parakh, R Swarnakar, V Shobha, B Thangakunam, Z Udwadia, M Henry, K O'Reilly, A Balbir-Gurman, M Kramer, I Litinsky, I Rosner, M Cutolo, A Gabrielli, L Iaccarino, A Pesci, V Riccieri, S Vettori, Y Funakubo, Y Inoue, A Kawakami, Y Kawaguchi, T Kawamura, Y Kondoh, M Kuwana, T Nanki, Y Nishioka, K Nozawa, T Ogura, M Okamoto, H Sano, R Sasai, N Sasaki, T Suda, H Takahashi, T Takeuchi, S Makino, S Tanaka, Y Yamasaki, S S Ch'ng, C Cheah, S Kan, R B Raja Mohamed, M Selman, J K de Vries-Bouwstra, L van den Toorn, M Vonk, A E Voskuyl, A M Hoffmann-Vold, M Seip, I Dankiewicz-Fares, R Olesiejuk, G Pulka, J Szepietowski, J Alves, M Bernardes, A Cordeiro, J Costa, S Neves, M J Salvador, J Alegre Sancho, P Carreira Delgado, I Castellví Barranco, J Cifrián Martínez, A Guillén del Castillo, J G Ovalles, F J López-Longo, A Rivera Gallego, M C Freire Dapena, J A Román Ivorra, A-K H Ekwall, B Maurer, C M Mihai, R Müller, A Mahakkanukrauh, K Nantiruj, B Siripaitoon, C P Denton, A Herrick, R Madhok, T M Maher, A West, D Antin-Ozerkis, R Bascom, G Criner, M E Csuka, J Dematte D'Amico, N Ettinger, A Fischer, A Gerbino, A Gerke, M Glassberg, C Glazer, J Golden, R Gripaldo, N Gupta, M Hamblin, K Highland, L Ho, J T Huggins, L Hummers, L Jones, M Kahaleh, D Khanna, H Kim, L H Lancaster, T Luckhardt, M Mayes, F Mendoza Ballesteros, J Mooney, P Mohabir, B Morrissey, T Moua, M Padilla, N Patel, R Perez, J Roman, M Rossman, T Russell, L Saketkoo, A Shah, O Shlobin, M B Scholand, R Simms, R Spiera, V Steen, S Veeraraghavan, and S Weigt

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Rheumatology online.

Data availability

To ensure independent interpretation of clinical study results and enable authors to fulfil their role and obligations under the ICMJE criteria, Boehringer Ingelheim grants all external authors access to relevant clinical study data. In adherence with the Boehringer Ingelheim Policy on Transparency and Publication of Clinical Study Data, scientific and medical researchers can request access to clinical study data after publication of the primary manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal, regulatory activities are complete and other criteria are met. Researchers should use https://vivli.org/ to request access to study data and visit https://www.mystudywindow.com/msw/datasharing for further information.

Funding

This work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH (BI). The authors did not receive payment for development of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement: Yannick Allanore reports consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) and Sanofi; fees for speaking from AbbVie, BI, Janssen; and has participated on Data Safety Monitoring Boards or Advisory Boards for BI, Chemomab, Curzion, Medsenic, Menarini, Prometheus, Sanofi. Dinesh Khanna reports grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Horizon Therapeutics, Pfizer; consulting fees from AbbVie, BI, Bristol Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Genentech, Horizon Therapeutics, Janssen, Prometheus, Talaris, Theraly; fees for speaking from AbbVie, BI, CSL Behring, Genentech, Horizon Therapeutics, Janssen; has received royalties or licences for the University of California Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium (SCTC) Gastrointestinal Tract instrument 2.0; holds a leadership or fiduciary role with Eicos; and owns stock in Eicos. Vanessa Smith reports grants paid to her institution from the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research in Rheumatic Diseases, BI, Janssen-Cilag, Research Foundation Flanders; consulting fees and fees for speaking paid to her and to her institution from BI and Janssen-Cilag; fees for speaking from Galapagos; support for travel from BI; fees for advisory board participation paid to her institution by Janssen-Cilag; she holds unpaid roles on ACR and EULAR study groups. Martin Aringer reports consulting fees for advisory boards and fees for lectures from BI and Roche. Anna-Maria Hoffmann-Vold reports grants from BI and Janssen; consulting fees from Arxx Therapeutics, Bayer, BI, Genentech, Janssen, Lilly, Medscape, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche; fees for speaking from Arxx Therapeutics, Bayer, BI, Janssen, Lilly, Medscape, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche; support for travel from BI, Medscape, Roche; she serves on the EULAR Quality of Care Committee, is the CTD-ILD ERS/EULAR convenor, and is the EULAR study group leader on the lung in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Masataka Kuwana reports grants paid to his institution from BI, MBL, Ono; royalties or licences from MBL; consulting fees from Argenx, AstraZeneca, BI, Chugai, Corbus, GlaxoSmithKline, Horizon Therapeutics, Kissei, Mochida; and fees for speaking from AbbVie, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Astellas, BI, Chugai, Eisai, Janssen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Ono. He was a member of the SENSCIS trial Steering Committee. Peter A. Merkel reports grants and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, BI, Bristol Myers Squibb, ChemoCentryx, CSL Behring, Dynacure, EMD Serono, Forbius, GlaxoSmithKline, Immagene, InflaRx, Janssen, Jubilant, Kyverna, Magenta, MiroBio, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Neutrolis, Novartis, NS Pharma, Otsuka, Q32 Bio, Regeneron, Sparrow, Takeda; royalties or licences from UpToDate; support for travel from ChemoCentryx; and owns stock in Kyverna. Christian Stock and Steven Sambevski are employees of BI. Christopher P. Denton reports grants from Arxx Therapeutics, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Inventiva, Servier; consulting fees from AbbVie, Acceleron, Bayer, BI, Corbus, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Horizon Therapeutics, Inventiva, Roche, Sanofi; and fees for speaking from BI, Corbus, Janssen.

References

- 1. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J. et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2737–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simeón-Aznar CP, Fonollosa-Plá V, Tolosa-Vilella C. et al. Registry of the Spanish network for systemic sclerosis: clinical pattern according to cutaneous subsets and immunological status. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012;41:789–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frantz C, Huscher D, Avouac J. et al. ; EUSTAR Co-authors. Outcomes of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis patients: results on more than 12,000 patients from the EUSTAR database. Autoimmun Rev 2020;19:102452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Freitas R, Martins P, Dourado E. et al. Clinical features and outcome of 1054 patients with systemic sclerosis: analysis of Reuma.pt/SSc registry. ARP Rheumatol 2022;1:21–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fretheim H, Halse AK, Seip M. et al. Multidimensional tracking of phenotypes and organ involvement in a complete nationwide systemic sclerosis cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:2920–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R. et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol 1988;15:202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nihtyanova SI, Schreiber BE, Ong VH. et al. Prediction of pulmonary complications and long-term survival in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:1625–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sánchez-Cano D, Ortego-Centeno N, Callejas JL. et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: data from the Spanish scleroderma study group. Rheumatol Int 2018;38:363–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffmann-Vold AM, Fretheim H, Halse AK. et al. Tracking impact of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis in a complete nationwide cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200:1258–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khanna D, Lin CJF, Furst DE. et al. ; focuSSced Investigators. Tocilizumab in systemic sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:963–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khanna D, Spino C, Johnson S. et al. Abatacept in early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: results of a phase II investigator-initiated, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:125–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spiera R, Kuwana M, Khanna D. et al. Phase 3 trial of lenabasum, a CB2 agonist, for the treatment of diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (dcSSc) [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:102–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Allanore Y. Limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis: the unfairly neglected subset. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2016;1:241–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoffmann-Vold AM, Allanore Y, Alves M. et al. ; EUSTAR Collaborators. Progressive interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease in the EUSTAR database. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:219–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wollin L, Distler JH, Denton CP, Gahlemann M.. Rationale for the evaluation of nintedanib as a treatment for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2019;4:212–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M. et al. ; SENSCIS Trial Investigators. Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2518–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vonk MC, Guillén-Del-Castillo A, Kreuter M. et al. A drug-drug interaction study to investigate the effect of nintedanib on the pharmacokinetics of Microgynon (ethinylestradiol and levonorgestrel) in female patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2022;47:81–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Allanore Y, Vonk MC, Distler O. et al. ; SENSCIS-ON Trial Investigators. Continued treatment with nintedanib in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: data from SENSCIS-ON. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:1722–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM.. The St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med 1991;85(Suppl B):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Volkmann ER, Kreuter M, Hoffmann-Vold AM. et al. Dyspnoea and cough in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease in the SENSCIS trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;61:4397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoffmann-Vold AM, Maher TM, Philpot EE. et al. The identification and management of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: evidence-based European consensus statements. Lancet Rheumatol 2020;2:e71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clements PJ, Roth MD, Elashoff R. et al. ; Scleroderma Lung Study Group. Scleroderma Lung Study (SLS): differences in the presentation and course of patients with limited versus diffuse systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1641–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuwana M, Allanore Y, Denton CP. et al. Nintedanib in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease: subgroup analyses by autoantibody status and modified Rodnan skin thickness score. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022;74:518–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zanatta E, Huscher D, Ortolan A. et al. ; EUSTAR Collaborators. Phenotype of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis patients with positive anti-topoisomerase I antibodies: data from EUSTAR cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;61:4786–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dougherty DH, Kwakkenbos L, Carrier ME. et al. ; SPIN Investigators. The Scleroderma Patient-Centered Intervention Network Cohort: baseline clinical features and comparison with other large scleroderma cohorts. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:1623–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Highland KB, Distler O, Kuwana M. et al. ; SENSCIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease treated with mycophenolate: a subgroup analysis of the SENSCIS trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kreuter M, Hoffmann-Vold AM, Matucci-Cerinic M. et al. Impact of lung function and baseline clinical characteristics on patient-reported outcome measures in systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2023;62:SI43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

To ensure independent interpretation of clinical study results and enable authors to fulfil their role and obligations under the ICMJE criteria, Boehringer Ingelheim grants all external authors access to relevant clinical study data. In adherence with the Boehringer Ingelheim Policy on Transparency and Publication of Clinical Study Data, scientific and medical researchers can request access to clinical study data after publication of the primary manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal, regulatory activities are complete and other criteria are met. Researchers should use https://vivli.org/ to request access to study data and visit https://www.mystudywindow.com/msw/datasharing for further information.