Abstract

Objective:

Individuals are often inaccurate at estimating levels of intoxication following doses of alcohol. Previous research has shown that when required to estimate blood alcohol concentration (BAC) at different time points, participants often underestimate their BACs and amounts of alcohol consumed. The present study aimed to increase drinkers’ BAC estimation accuracy after drinking alcohol using mindfulness-based feedback to increase their awareness of the interoceptive cues associated with alcohol intoxication.

Method:

Thirty-three adults were given 0.65 g/kg of alcohol and received one of three training conditions: BAC feedback only, body scan exercise + BAC feedback and no treatment control. Those in the BAC feedback group received feedback concerning their observed BAC during dose exposure. Participants in the body scan group received BAC feedback and underwent a mindfulness exercise to enhance their perception of the acute subjective effects of alcohol. The control group received no BAC estimation training. Participants attended four study sessions: Two training sessions where participants underwent structured training based on their condition and two retention sessions to test for the lasting effects of the training exercises.

Results:

Retention tests showed that participants in both treatment groups were most accurate in estimating their BACs. There were no differences among the groups in their perceived levels of intoxication at post-training. The findings suggest that BAC feedback, alone and in combination with, mindfulness training can improve accuracy in estimating BACs.

Conclusions:

The findings provide preliminary support for the efficacy of mindfulness training in combination with BAC feedback to improve BAC estimation accuracy.

Keywords: Alcohol, Driving, Blood Alcohol Concentration, Mindfulness, Estimation

Introduction

Drinkers are poor estimators of their blood alcohol concentration (BAC) while drinking. Laboratory studies show that at low BACs (i.e., 20 mg/dL) participants tend to overestimate their BAC and at higher BACs (i.e., 50 mg/dL) they tend to underestimate their BAC (Cameron et al., 2018; Grant et al., 2012). Pharmacokinetic factors and acute tolerance to the subjective effects of alcohol likely contribute to drinkers’ poor BAC estimation (Beirness & Vogel-Sprott, 1984; Martin et al., 2013; Moskowitz & Robinson, 1988). The present study tested the efficacy of using mindfulness-based feedback to enhance accuracy of BAC estimation during intoxication.

BAC discrimination training (BDT) to increase self-awareness of alcohol intoxication involves training individuals to better estimate their BAC after drinking to be able to discriminate higher “risky” BAC levels from low “safe” levels. Research on BDT shows that individuals can learn to accurately estimate their BAC when given BAC feedback training in the laboratory. This training requires participants to estimate their BAC level repeatedly following a dose of alcohol. Following each estimate, participants receive feedback of their observed BAC. With repeated training, estimation accuracy improves markedly (Aston & Luguori, 2013; Bois & Vogel-Sprott, 1974; Ogurzdoff & Vogel-Sprott, 1976). The training effect is robust; however, it tends to be limited in generalizability to the situation where the BAC feedback is provided, which is in a laboratory setting (Aston et al., 2013, Meier et al., 1984). Once feedback is removed drinkers’ estimation accuracy quickly declines. This situational dependence might occur because BDT trains individuals to rely solely on the external BAC feedback in the situation to guide their estimations and not on any personal, subjective cues of intoxication that could also aid in appraising one’s BAC.

Mindfulness training, in combination with BDT, could offer additional skills necessary to help individuals accurately perceive their levels of intoxication during a drinking episode. Mindfulness involves intentionally and nonjudgmentally attending to one’s moment-to-moment experience while in a state of consciousness (Shapiro et al., 2006). The general aim of mindfulness based interventions (MBIs) is to increase awareness of one’s internal state, thoughts, and feelings to facilitate more skillful responses to stressors and distractions in daily life (Baer, 2003). The effectiveness of MBIs for the treatment of mental and physical clinical problems, such as chronic pain, mood disorders, and substance abuse, as well as for stress in healthy populations, has been well demonstrated (Chiesa & Serretti, 2014; Galante et al., 2013; Khoury et al., 2013; Sharma & Rush, 2014). Increasing awareness of interoceptive cues associated with alcohol intoxication could improve the accuracy of BAC estimation and its generalizability outside the laboratory. The “Body Scan” exercise is a mindfulness-based technique that trains individuals to focus attention to bodily sensations in a controlled systematic manner (Mirams et al., 2013; Ussher et al., 2014). It is widely used in pain, stress management, and other mental health applications of MBIs and designed to improve bodily awareness in general daily life. Its emphasis on structured attention to bodily sensations and its practical everyday use makes it an ideal technique to improve BDT. In conjunction with BDT, such enhanced bodily awareness of intoxication could improve BAC estimation by teaching individuals to focus on specific interoceptive cues of intoxication in relation to their BACs, allowing them to better appraise their intoxication level and risk in any drinking setting. The techniques provided through body scan MBIs could allow BDT to generalize beyond the laboratory to everyday drinking contexts, overcoming the major obstacle that has limited the practical application of BAC discrimination training techniques.

The present study tested the efficacy of mindfulness-based body scan training in conjunction with BDT to enhance the accuracy of BAC estimation during alcohol intoxication in adult alcohol drinkers. This experiment was a proof of concept study of the potential utility of MBI-based approaches to enhance self-perception of intoxication. Participants received a dose of alcohol during laboratory test sessions and were asked to estimate their BAC at various times throughout the test sessions. Participants were assigned to one of three training conditions designed to improve their BAC estimation accuracy: Body scan exercise + BAC feedback, BAC feedback only, and no treatment control. Those in the body scan group received guided instruction to focus their attention on interoceptive cues of intoxication in conjunction with feedback about their actual BAC. Those in the feedback only group received only the BAC feedback. It was predicted that the body scan group would perceive a higher magnitude of subjective effects of intoxication due to the mindfulness training that focused specifically on interoceptive cues of intoxication. It was also predicted that the accuracy of BAC estimation would improve during training in both treatment groups (body scan + BAC feedback and BAC feedback only) but that the body scan group would display the greatest retention of this training effect during follow up test sessions when training was no longer provided.

Method

Participants

Thirty-three adults (18 men; 15 women) between the ages of 21 and 33 years participated in this study (M age = 23.4, SD = 2.8). Participants self-identified as Asian (n = 2), African American/Black (n = 2), Hispanic/Latino (n = 3), Caucasian (n= 25), or as other (n = 1). Newspaper, web listings, community bulletin, and radio advertisements were used to recruit participants from the Lexington, Kentucky area and surrounding counties. Interested individuals called the laboratory and completed a telephone screening during which information on demographics, drinking habits, drug use, and physical and mental health was gathered. Volunteers were informed that they would be consuming alcohol during the study. Individuals reporting history of psychiatric disorder, CNS injury, or head trauma were excluded from participation. These individuals were excluded because the clinical conditions listed above present a high likelihood of impaired consent capacity or fluctuations in consent capacity. All volunteers were current consumers of alcohol, drinking more than twice a month with more than two drinks per occasion. Volunteers who reported risk for alcohol use disorder, as determined by a score of 5 or higher on the Short-Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (S-MAST; Selzer et al., 1975), were also excluded. The use of any psychoactive prescription medication and recent use of amphetamines (including methylphenidate), barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, opiates, and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) was assessed by means of urine analysis. Any volunteer testing positive for the presence of any of these drugs, except THC, during the sessions was excluded from participation. In the event of a positive test for THC, if the self-reported time of last use was greater than 24 hours the session continued as normal. If THC was used in the past 24 hours, the session was rescheduled to a later date. No female volunteers who were pregnant participated in the research, as determined by self-report and urine human chorionic gonadotrophin levels (Icon25 Hcg Urine Test, Beckman Coulter). Women who were breastfeeding were also excluded from participation as these criteria increase the vulnerability to risks associated with alcohol ingestion. Less than 20% of volunteers failed to pass screening. The University of Kentucky Medical Institutional Review Board approved the study. All study volunteers provided informed consent prior to participation for IRB: 44682 titled “Behavioral Dysregulation and Alcohol Sensitivity in Risky Drivers.”

Materials and Measures

Drinking Habits

Participants’ drinking habits were assessed using the Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992), which assessed daily drinking patterns over the past 3 months. For the TLFB, three measures of drinking habits were obtained: (a) total number of drinking days (drinking days), (b) total number of drinks consumed (total drinks), and (c) total number of days characterized by subjective drunkenness (drunk days).

Subjective Effects

Participants provided ratings of multiple subjective effects in response to the doses of alcohol administered during the study sessions including feelings of tingliness, dizziness, sedation, intoxication, concentration, warmth, restlessness, pleasure, relaxation, stimulation, and numbness. The subjective effects were marked on 100 mm visual-analogue scales ranging from 0 “not at all” to 100 “very much.” These scales have been used in other alcohol studies of driving and are sensitive to the effects of the drug (e.g., Harrison & Fillmore, 2005; Harrison et al., 2007; Van Dyke & Fillmore, 2015).

BAC Estimation

Participants provided estimations of their BACs on a BAC estimation scale. The scale consisted of a statement saying “The legal limit for driving is 0.08 percent. On the scale below, please circle the tick mark that best indicates your current blood alcohol level (BAL).” The scale ranged from 0.0 to 0.160 g/dL with a provided midpoint of the current legal driving limit (i.e., 0.08 g/dL).

Study Design and Procedure

The study was conducted in the Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory of the Department of Psychology at the University of Kentucky. All sessions began between 1:00 PM and 6:00 PM. All participants were required to abstain from alcohol for 24 hours and food for 4 hours prior to each session to ensure consistent BAC curve trajectory across participants. The alcohol dose was calculated based on participants’ body weight. Breath and urine samples were obtained prior to sessions to verify zero BACs, check for recent drug use, and confirm that women were not pregnant. Eleven participants were randomly assigned to one of three training conditions: Body scan exercise + BAC feedback, BAC feedback only, and no treatment control. Recruitment continued until 11 study-eligible participants were obtained in each of the three training conditions.

Training Sessions

Participants attended two identical training sessions in which they received a controlled dose of alcohol and underwent structured training based on their assigned training condition. At the beginning of each training session, participants received 0.65 g/kg alcohol. This dose was chosen because it produces an average peak BAC of 80 mg/dL (0.08%), which is the legal driving limit, yields robust subjective and behavioral effects, and there is established sensitivity of this dose from previous research (Van Dyke & Fillmore, 2017). The alcohol was mixed with a carbonated, non-caffeinated, lemon flavored soda and participants were to consume the beverage in six minutes. During each session, training exercises were completed twice on the ascending limb and twice on the descending limb when the participant’s BAC was ± 5 mg/dL of 4 target BACs: 45 mg/dL-ascending, 70 mg/dL-ascending, 70 mg/dL-descending, and 45 mg/dL-descending. The target BACs on the ascending and the descending limbs were approximately 50% and 75% of the peak BAC (rounded to 5 mg/dL increments). Timewise these exercises occurred at approximately 30 minutes, 50 minutes, 70 minutes, and 100 minutes post-alcohol administration. Throughout the training sessions, the experimenter insured participants were actively participating by observing them completing the training exercises. The two training sessions were scheduled at least 1 day apart but no further than 7 days apart (SD = 1.73).

BAC Feedback Only

This condition was modeled after BDT. Participants consumed the alcohol dose and then were asked to estimate their BAC on the BAC estimation scale. After each BAC estimation, they were immediately informed of their observed BAC obtained from a breath sample using an Intoxilyzer Model 400 (CMI Inc. Owensboro, KY). This information gave participants real-time feedback regarding the accuracy of their estimated BAC in relation to their observed BAC. This BAC feedback was presented to the participant immediately in graphic display depicting their estimated BAC in comparison to their observed BAC. This exercise was repeated four times during the time course of the alcohol dose.

Body Scan Exercise + BAC Feedback

This training condition was designed to train individuals to better estimate their BAC after drinking, not simply by using feedback about one’s observed BAC, but by improving ones’ ability to perceive and attend to specific interoceptive cues or sensations of intoxication that occur while drinking alcohol and learn what BACs are associated with these particular sensations. After receiving the alcohol dose, participants underwent a body scan mindfulness exercise aimed at teaching them to attend to alcohol-induced interoceptive cues in a controlled systematic manner. During the 10 minute exercise, participants listened to an audio recording that instructed them to sequentially focus their attention on individual interoceptive cues of intoxication (e.g., dizziness, sedation, warmth). They were instructed to experience each sensation without distraction from competing thoughts or emotions. The interoceptive cues chosen for training were those that onset at a BAC between 50 and 80 mg/dL (Chiesa et al., 2011; Holloway, 1995; Lutz et al., 2008; Weafer & Fillmore, 2016). This exercise was repeated four times during the time course of the alcohol dose.

This group also received BAC feedback about the accuracy of their BAC estimations, like the BAC feedback only condition. By integrating this BAC feedback with the body scan exercise, this condition aimed to improve participants’ accuracy of BAC estimation outside of the laboratory by increasing participants’ awareness of interoceptive cues of intoxication alongside BAC feedback inside of the laboratory.

No Treatment Control

Participants in the control condition underwent the same alcohol exposures as those in the other two conditions and estimated their BACs. However, they did not receive any feedback on the accuracy of their BAC estimation.

To equate for experimenter interaction among the three conditions, the participants in the control and feedback conditions also received a control mindfulness exercise. The control mindfulness exercise was a standard audio-guided exercise that focused on breathing and relaxation but with no reference to alcohol, its effects, or cues of intoxication.

Retention of Training Effects on BAC Estimation Accuracy

Retention of training effects on participants’ BAC estimation accuracy was assessed at two time points after training: one week and 30–40 days after the second training session. During each retention test session, participants received a total alcohol dose of 0.65 g/kg absolute alcohol delivered in three smaller amounts (i.e., drinks) during the post-training assessments: 50% of the dose at time 0, 25% of the dose at 45 minutes following the initial drink, and 25% of the dose again at 75 minutes post initial drink. This dosing procedure produced a different BAC time course function from the training sessions, one that slowly ascended throughout the session and therefore differed from training sessions where BAC ascended and then descended over the session. Because the time course function differed from the training sessions, participants could not just simply base their BAC estimations on what they learned from the feedback previously received during the training sessions, and thus allowed for the examination of the generalizability of the training to a new drinking experience. All participants completed the same BAC estimation and subjective effect ratings as in the training session but without any body scan mindfulness training or BAC feedback. The estimates and ratings were obtained at 20, 35, 65, and 95 minutes from the onset of the dose administration. Three out of the thirty-three participants, one participant from each condition, were unable to return to the lab for the 30–40 day follow-up.

Following all sessions, participants remained in a lounge area where they were provided food and nonalcoholic beverages until their BACs reached 20 mg/dL or below. Upon completion of the final session, participants were paid $160 for participation with an $80 completion bonus, and debriefed. Transportation home was provided after all sessions.

Criterion Measures and Data Analyses

BAC Estimation Error

Estimation errors were calculated for each BAC estimation during the training sessions and retention sessions to determine participants’ accuracy in BAC estimation. BAC estimation error was calculated by subtracting participants’ observed BAC from their estimated BAC (i.e., estimated BAC – observed BAC). A positive estimation error value indicated an overestimation of BAC at a given timepoint whereas a negative estimation error value indicated an underestimation.

Subjective Intoxication

Subjective intoxication was measured as participants’ subjective response to the statement “I feel intoxicated.” The subjective effect was marked on a 100 mm visual-analogue scale ranging from 0 “not at all” to 100 “very much” across the training sessions and post-training assessment sessions.

Data were analyzed by mixed model ANOVA with condition as the between-subjects effect and session as the within-subjects effect. The sample size per condition was determined by power calculations using pilot data which reliably detected significant group × time interactions, with large effect sizes for group differences in the time course of effects (ds > 0.6) and sample sizes previously presented in studies of BAC estimation training ranging from 5 to 12 subjects with an average of 10 subjects per condition (Aston & Liguori, 2013; Bois & Vogel-Sprott, 1974; Huber et al., 1976; Lipscomb & Nathan, 1980; Ogurzsoff & Vogel-Sprott, 1976). BACs were analyzed in all sessions for possible sex differences and none was observed. However, the study was not designed to test for sex differences, nor powered to do so. Therefore, sex as a factor was not included in the analyses of the dependent measures.

Results

Drinking and Demographic Information

Participants’ drinking habits and demographic information are presented in Table 1. The table shows no difference between the participants in the three conditions regarding level of education, weight, sex, or age. With respect to drinking habits, the TLFB shows no difference between the participants in the three conditions. No drug urine screens were positive at the time of testing.

Table 1.

Group Comparisons on Demographic Information and Drinking Habits

| Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Treatment Control (n = 11) | BAC Feedback Only (n = 11) | Body Scan Exercise + BAC Feedback (n = 11) | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | |

| Age | 25.0 | 4.2 | 22.3 | 1.1 | 23.0 | 1.5 | 3.2 |

| Sex (% male) | 54.0 | 36.4 | 72.7 | 1.5 | |||

| Weight (kg) | 73.7 | 18.0 | 67.8 | 11.5 | 76.2 | 15.2 | 0.9 |

| Education | 15.8 | 1.5 | 14.9 | 1.4 | 15.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Drinking Habits | |||||||

| TLFB | |||||||

| Drinking days | 36.4 | 23.1 | 38.8 | 20.5 | 24.7 | 20.3 | 1.4 |

| Total drinks | 220.4 | 325.0 | 176.4 | 133.6 | 108.7 | 132.7 | 0.7 |

| Drunk days | 7.8 | 9.0 | 13.3 | 8.9 | 7.7 | 9.4 | 1.3 |

Note. For all comparisons, N = 33, degrees of freedom = 30. Age and education are reported in years. TLFB = variables reported on the Timeline Follow-Back Procedure, which assessed daily drinking patterns over the past 90 days.

p < .05

Observed and Estimated Blood Alcohol Concentrations

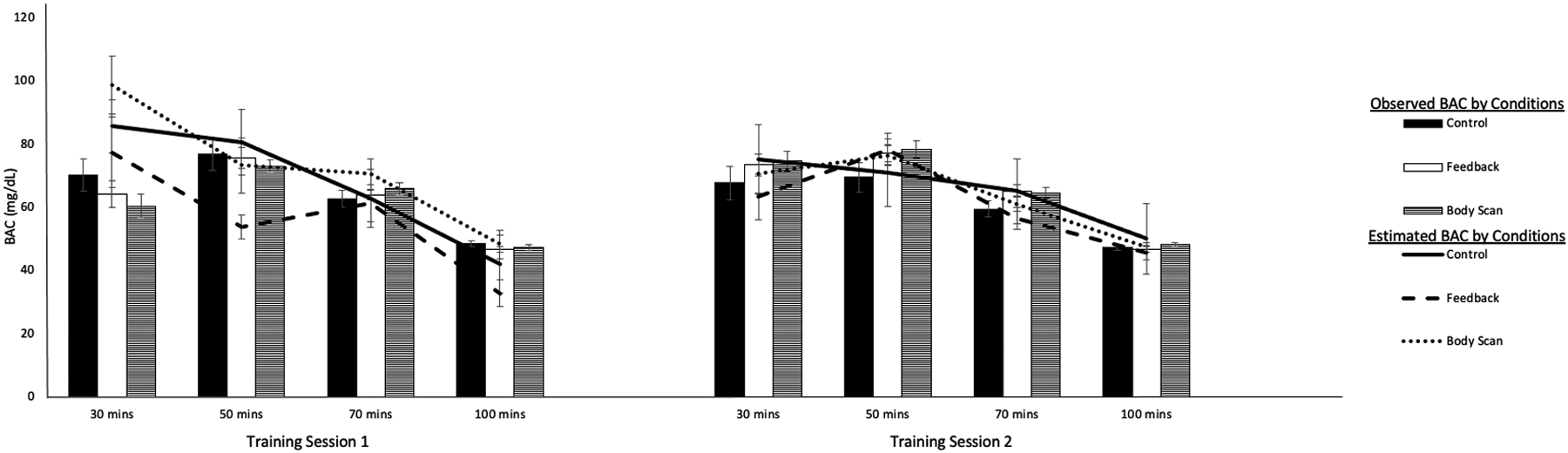

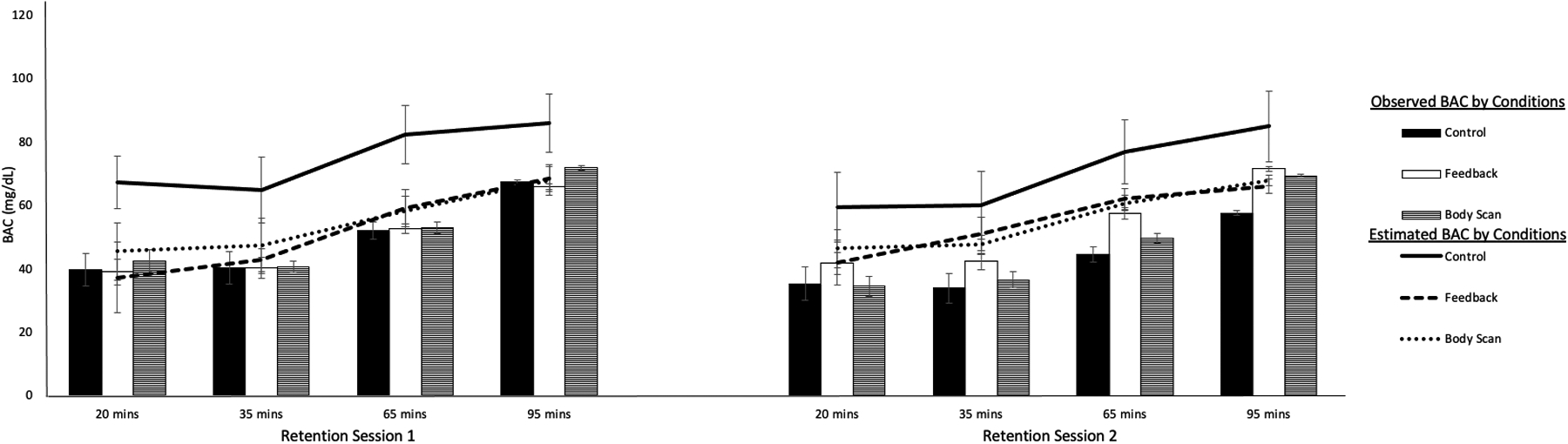

Figure 1a and 1b show the mean observed and estimated BACs in each condition during training and retention sessions. As expected, observed BACs were similar between conditions. During the training sessions, BACs rose to approximately 75 mg/dL and declined to approximately 50 mg/dL. During the retention sessions, observed BACs gradually increased to approximately 75 mg/dL across the sessions. With regard to estimated BACs, the figures show that participants were able to perceive change in BAC across a session such that their BAC estimations rose and declined with their observed BACs. During training, BAC estimations were similar to observed BACs in all conditions. However, the retention test at one week and one month after training shows control participants overestimating their BACs whereas those who received body scan + feedback and feedback reported BAC estimates that were highly similar to their to their observed BACs during retention.

Figure 1a.

Mean observed and estimated BACs at each time point during training sessions in each condition. Bars depict the participants’ observed BAC and lines depict the participants’ estimated BAC.

Figure 1b.

Mean observed and estimated BACs at each time point during retention sessions in each condition. Bars depict the participants’ observed BAC and lines depict the participants’ estimated BAC.

BAC Estimation Error

Pre-training Estimation Error

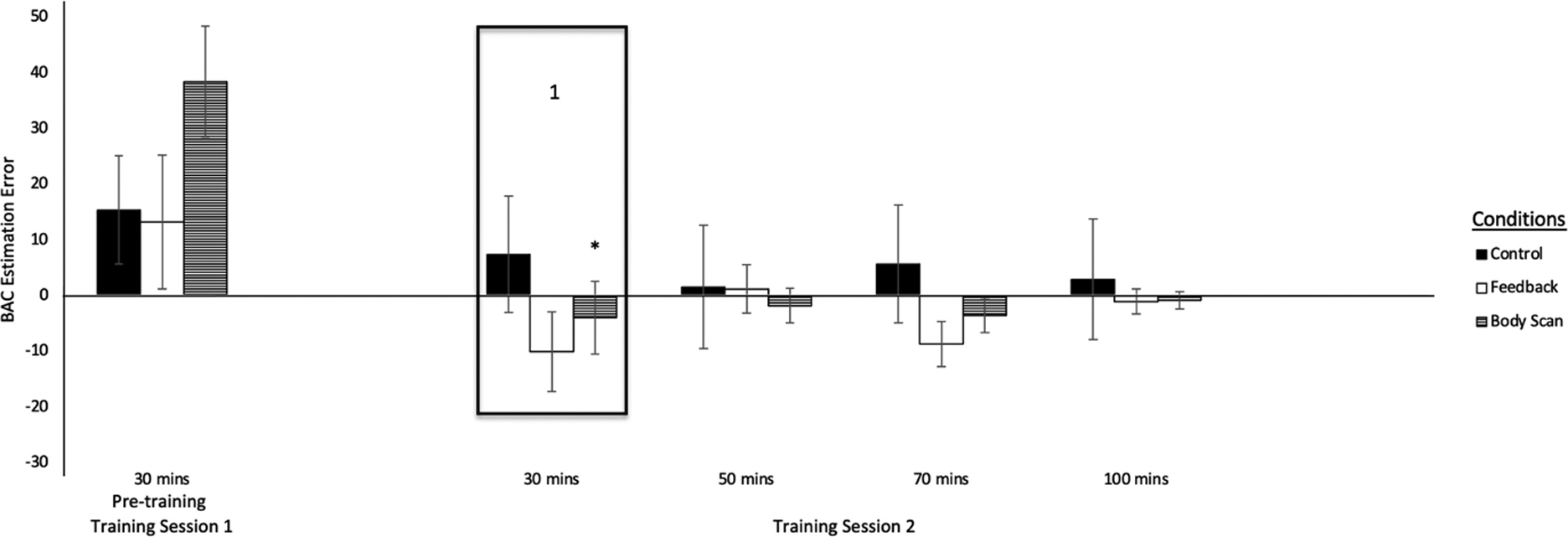

Pre-training error was the participants’ estimation error at the pre-training test (i.e., 30 minutes on training session one). The scores are considered “baseline” pre-training measures of BAC estimation error because participants reported this BAC estimation prior receiving any feedback regarding the accuracy of their reports. Figure 2a shows differences in the average estimation error in each condition but an ANOVA revealed no significant differences between conditions (ps > .05). At pre-training, the sample as a whole overestimated their BAC by a mean of 22.3 mg/dL (SD = 36.0) and a one-sample t test showed that this error was significantly greater than zero, t(32) = 3.56, p = .001, d z = 0.62. A correlation between participants’ pre-training estimated and observed BAC showed no significant relationship, r(31) = −0.05, p = 0.78. Thus, prior to treatment, there were no differences between conditions in BAC estimation, participants tended to overestimate their BAC, and their estimated BACs bore no relation to their observed BACs.

Figure 2a.

BAC estimation error at each time point during pre-training and training session 2 in each condition. Box 1 shows mean BAC estimation error for each condition during the second training session at a mean observed BAC most comparable to the observed BAC during the pre-training test. An asterisk indicates a significant reduction in error from the pre-training to the training session.

* p < .05

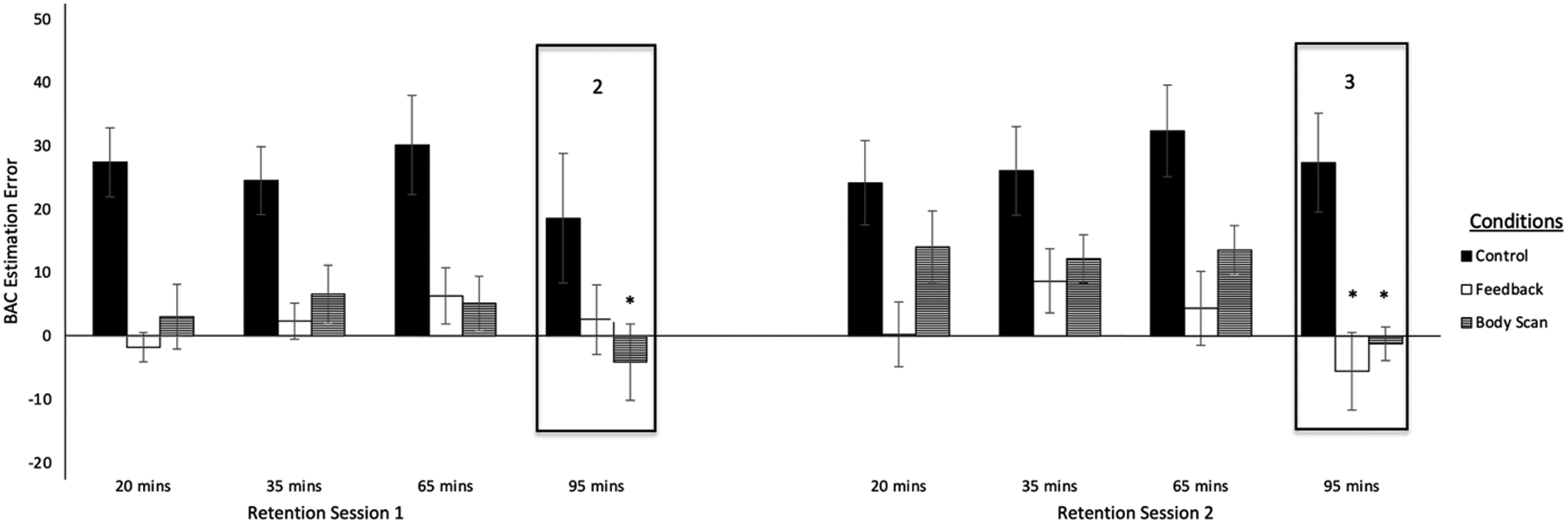

Training and Retention Error

Figures 2a and 2b show an overview of estimation error for the participants in each condition during the pre-training, training, and retention sessions. Estimation errors showed a notable reduction during training sessions regardless of condition. During one week and one month retention, participants continued to display reductions in error for those who received BAC feedback and the body scan exercise + BAC feedback, but not for those in the control condition.

Figure 2b.

BAC estimation error at each time point during retention sessions in each condition. Box 2 and 3 show mean BAC estimation error for each condition during the retention sessions at mean observed BACs most comparable to the observed BAC during the pre-training test. An asterisk indicates a significant reduction in error from the pre-training to the retention session.

* p < .05

Of the two training sessions, only the second session was analyzed to allow for training effects to accrue. To compare participants’ estimation errors at training and retention with their pre-training estimation error, we selected the training and retention tests for which the observed BAC being estimated was most comparable to the observed BAC estimated at pre-training. For the training session, the first test at 30 min post-alcohol administration best matched the observed BAC at pre-training (see Figure 1a). For the retention sessions, the best match was the fourth test at 95 minutes post-administration (see Figure 1b). These observed BACs were analyzed by a 3 (Condition) × 4 (Time: pre-training, training at 30 minutes, one-week retention at 95 minutes, one-month retention at 95 minutes) ANOVA. No significant main effects of condition, time or their interaction were obtained (ps > 0.05) thus demonstrating the comparability of the observed BAC across condition and session.

Effects of Training Condition during Training

Figure 2a box 1 shows less estimation error during training in all conditions compared with pre-training. A 3 (Condition) × 2 (Session: pre-training vs training session 2) ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F(1, 30) = 16.20, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.351, owing to participants showing less error during training compared to pre-training. There was no significant main effect of condition or interaction (ps > 0.05). Simple effects tests compared participants’ estimation error during training to their pre-treatment error and revealed a significant reduction in estimation error from pre-training to training for those in the body scan condition, t(10) = 4.26, p = .002, d z = 1.28, but not the control or feedback conditions (ps > 0.05).

Effects of Training Condition during Retention

Participants’ estimation error one week and one month after training can be seen in Figure 2b (i.e., boxes 2 and 3). Compared with pre-training, Figure 2b shows less error during retention sessions for those in the body scan + feedback and feedback only conditions and increased error for the controls. The effect of training condition on BAC estimation error at one week retention was tested with a 3 (Condition) × 2 (Session: pre-training vs retention session 1) ANOVA. The ANOVA revealed a main effect of session, F(1, 30) = 5.10, p = .031, ηp2 = 0.145, owing to the overall reduction in estimation error at retention and a Session × Condition interaction, F(2, 30) = 3.40, p = .047 ηp2 = 0.185. Simple effects comparisons revealed a significant reduction in error from pre-training to retention for those in the body scan condition, t(10) = 3.15, p = .010, d z = 0.95, but not the control or feedback condition (ps > 0.05). At one month retention, the ANOVA also revealed a main effect of session, F(1, 27) = 6.62, p = .016, ηp2 = 0.197 and Session × Condition interaction, F(2, 27) = 6.91, p = .004, ηp2 = 0.339. Simple effects tests revealed significant reductions in error from pre-training to one month retention for the body scan, t(9) = 2.33, p = .045, d z = 0.74, and feedback conditions, t(9) = 3.31, p = .009, d z = 1.05, but not the control condition (ps = .184. Figure 2b, box 3 shows that controls overestimated their BACs one month post-training whereas those in the treatment conditions were fairly accurate in their estimations.

The magnitude of final estimation error was also analyzed for each condition in terms of the error being significantly greater than zero (i.e., no error: estimated BAC = observed BAC). One-sample t tests showed that the final estimation error of those in the body scan and feedback conditions was not significantly different from 0 (ps > 0.05) whereas the error of those in the control condition was significantly greater than 0, F(1, 27) = 21.35, p = .001, ηp2= 0.442. Thus, at one month retention, those in the treatment groups reported near accurate BAC estimations whereas those in the control condition overestimated their BAC.

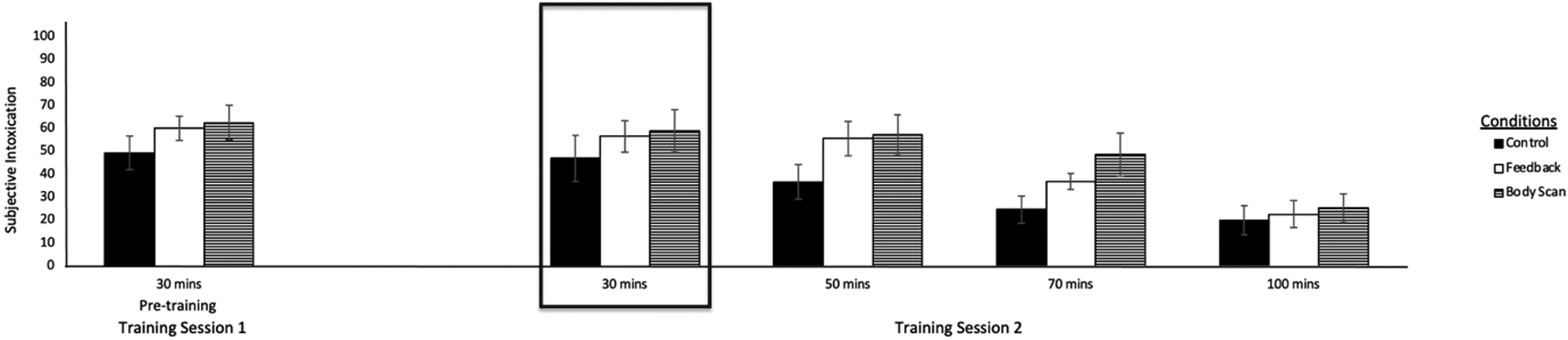

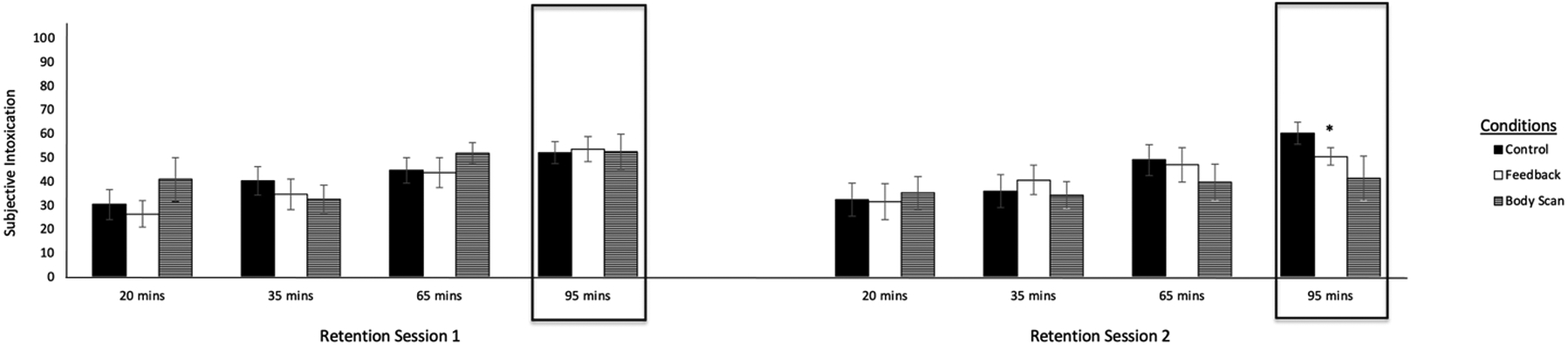

Subjective Intoxication

Figures 3a and 3b plot participants’ subjective intoxication by condition during the training and retention sessions. Treatment effects on subjective intoxication were examined by ANOVA. As stated above, only the second of the two training sessions was analyzed and specific tests during the training and retention sessions were selected to best match the observed BACs to pre-training (i.e., first test on training session one and fourth test on retention sessions one and two). An ANOVA of pre-training subjective intoxication revealed no condition effect (ps > 0.05). The effect of training on subjective intoxication was examined by a 3 (Condition) × 2 (Session: pre-training vs training session 2) ANOVA. The ANOVA revealed no main effects or interaction (ps > 0.05). A 3 (Condition) × 2 (Session: pre-training vs retention) ANOVA of subjective intoxication at one week retention revealed no main effects or interaction (ps > 0.05), but did show a significant Session × Condition interaction, F(2, 27) = 5.38, p = .011, ηp2 = 0.285, at one month. Simple effect tests compared subjective intoxication at pre-training to one month and revealed a significant reduction in subjective intoxication from pre-training to one month retention for those in the feedback condition, t(9) = 2.21, p = .054, d z = 0.70, but not the control or body scan conditions (ps > 0.05).

Figure 3a.

Subjective intoxication at each time point during pre-training and training session 2 in each condition. The box shows mean subjective intoxication for each condition during the pretraining and training sessions at a mean observed BAC most comparable to the observed BAC during the pre-training test.

Figure 3b.

Subjective intoxication at each timepoint during retention sessions in each condition. The boxes show mean subjective intoxication for each condition during the retention sessions at mean observed BACs most comparable to the observed BAC during the pre-training test. An asterisk indicates a significant reduction in error from the pre-training to the retention session.

* p < .05

Discussion

This study examined the efficacy of using experiential-based feedback to enhance accuracy of BAC estimation during intoxication.. At the start of the study, participants did not differ in their BAC estimation error. Before receiving any training, all the participants were poor BAC estimators and overestimated their BACs. Participants in the feedback and body scan groups showed substantial improvements in BAC estimation accuracy after completing the BAC estimation training exercises. Additionally, these improvements were retained over time resulting in those participants providing nearly accurate BAC estimations long after the training had been completed. The results show that one month after attending training, the participants in the body scan and feedback conditions were highly effective at accurately estimating their BACs compared to pre-training and provided nearly accurate BAC estimations while the control participants greatly overestimated their BACs. Furthermore, for those in the body scan and feedback conditions, final estimation error was not significantly different from zero meaning that one month after training, for the participants in the feedback and body scan groups estimates of their BACs were nearly error-free. Moreover, this effect was retained one month after training which has never been shown in the research of BAC training exercises.

It is unclear as to why participants in the feedback only group showed BAC estimation accuracy at one month. Typically BAC feedback does not generalize outside the training situation, such that once feedback is removed, estimation accuracy declines again. One possibility for the retention of their accuracy is that we provided BAC feedback in real time and across the study session, such that individuals were told their observed and estimated BAC as they were estimating their BAC and could reference previous observed and estimated BACs during the same session with a line graph. In previous studies of BAC feedback, participants were only verbally provided their observed BAC measurement in real time as BAC feedback (Bois & Vogel-Sprott, 1974; Ogurzdoff & Vogel-Sprott, 1976). It is possible that participants in the feedback only condition showed improved BAC estimation accuracy at retention because the participants had a visual image of their observed and estimated BACs from across the training sessions to recall during retention sessions.

Throughout the study, participants in the control condition did not show any significant change in BAC estimation error. However, Figure 2a shows that the control participants reduced their BAC estimation error during training even though the participants were not provided with any BAC estimation training exercises. This effect was unexpected, and it is unclear why they showed improved accuracy in BAC estimation during training despite not completing any training exercises. It is possible that even when people are asked to simply focus on the present moment through a general mindfulness exercise and estimate their BAC on a visual scale, participants can temporally improve their BAC estimation accuracy. However, this effect did not persist over time or outside of the training sessions as the control group greatly overestimated their BACs during the retention sessions and their BAC overestimation became more pronounced as more time passed after the training sessions.

The body scan mindfulness exercise was designed to increase participants’ ratings of subjective intoxication by having participants listen to an audio recording that instructed them to sequentially focus their attention on individual interoceptive cues of intoxication (e.g., dizziness, sedation, warmth). It was expected that the participants in the body scan condition would have rated themselves as having increased subjective intoxication because they completed the body scan mindfulness exercise that focused on interoceptive cues of alcohol intoxication during training whereas the participants in the feedback and control conditions completed a control mindfulness exercise. During the study, the groups only differed in their ratings of subjective intoxication at one month retention, where the feedback group showed a significant reduction in subjective intoxication. It is possible that the body scan group failed to report increased subjective intoxication because they never received any confirming feedback to support a perception of increased intoxication, such as evidence of alcohol’s impairing effect on their behavior. If individuals were to have received feedback showing that they were behaviorally impaired, they might have perceived themselves as more intoxicated and rated their subjective intoxication higher. However, because individuals knew from their BAC estimation training that they were below the legal limit and did not necessarily observe any overt behavioral impairment, they might have had little reason to increase their appraisal of intoxication. If a participant were to have participated in a field sobriety test to better recognize their impairment, the body scan condition could have reported increased subjective intoxication.

Some limitations of the study should be noted. Regarding the use of the body scan exercise outside the laboratory, we recognize that everyday drinking contexts involve many distractions that could compete with, and possibly undermine, one’s ability to attend to interoceptive cues of intoxication. Indeed, a primary instruction of the mindfulness-based body scan is to first focus attention away from such distractions to better focus attention inward to the targeted bodily sensations. However, we do acknowledge that in everyday drinking contexts where many distractions are present, such a level of attentional focus could be quite challenging. The findings are also limited with respect to level of intoxication that was examined. Only one alcohol dose was tested producing a peak BAC of 80 mg/dL. Although the dose regiment was varied across the training and retention sessions to simulate difference patterns of consumption between session, the consistency of training effects across a range of alcohol doses would be important to test as BAC estimation accuracy has been found to vary between higher and lower doses (Cameron et al., 2018; Grant et al., 2012). It is possible that the efficacy to improve BAC estimation accuracy might diminish at BACs above 80 mg/dL, as impairments of cognitive function, including the ability to allocate and sustain attention become more pronounced. The sample of this study was small precluding the ability to test for potential sex differences in BAC estimation accuracy and training effects. Additionally, the sample did not have a history of driving under the influence (DUI) due to DUI offenders being relatively difficult to retain and this training idea being new. Also, research indicates that heavier drinkers and individuals with alcohol use disorder respond differently to alcohol as compared to lighter and social drinkers, for example heavier drinkers are more likely to drive while intoxicated (Bujarski et al., 2015; King et al., 2011, 2021; LaBrie et al., 2011). Future research should consider observing the effects of these training techniques on different populations. Future research should also observe the impact of general mindfulness exercises on interoceptive awareness, individual’s understanding of BAC generally, the outcome of a body scan only condition, and responses to the question of how likely an individual would be to drive in the moment. It is important to consider the limitations of the training provided in this study and research the effects of those barriers with future studies.

Overall, this experiment was a proof of concept study designed to enhance drinkers’ self-perception of intoxication. The ability of this treatment to improve the accuracy of participants’ BAC estimation and retain this skill one month after treatment raises the possibility that such training might also improve one’s awareness of the risk associated with engaging in certain activities their current level of intoxication, such as driving an automobile. Indeed, DUI prevention research has identified risk perception as a key cognitive target to motivate behavior change in DUI offenders (Daugherty & Leukefeld, 2003; Miller & Rollnick, 2012; Petty & Briñol, 2008). Approaches to improve BAC estimation, such as those used in the current study, could offer the skills necessary to help DUI offenders accurately perceive their levels of intoxication during a drinking episode and make less risky decisions, such as driving after drinking.

Public Health Significance Statement.

Individuals have been shown to be poor estimators of BAC level while drinking. However, this study shows that after receiving feedback of their actual BACs and participating in a mindfulness exercise to increase interoceptive awareness of alcohol intoxication while drinking, participants learned to accurately estimate their BACs and retained this knowledge. These findings highlight how individuals can be taught to accurately estimate their BACs through mindfulness training and BAC feedback. The retention of the training effect after their removal suggests that such improved accuracy of BAC estimation might generalize to situations outside the laboratory.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded through National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant T32 AA027488 and R01 AA028447.

References

- Aston ER, & Liguori A (2013). Self-estimation of blood alcohol concentration: A review. Addictive Behaviors, 38(4), 1944–1951. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beirness D, & Vogel-Sprott M (1984). The development of alcohol tolerance: Acute recovery as a predictor. Psychopharmacology, 84(3), 398–401. 10.1007/BF00555220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bois C, & Vogel-Sprott M (1974). Discrimination of low blood alcohol levels and self-titration skills in social drinkers. Quarterly journal of studies on alcohol. 10.15288/qjsa.1974.35.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski S, Hutchison KE, Roche DJ, & Ray LA (2015). Factor structure of subjective responses to alcohol in light and heavy drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(7), 1193–1202. 10.1111/acer.12737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron MP, Roskruge MJ, Droste N, & Miller PG (2018). Judgement of breath alcohol concentration levels among pedestrians in the night-time economy—A street-intercept field study. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 53(3), 245–250. 10.1093/alcalc/agx118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, & Serretti A (2014). Are mindfulness-based interventions effective for substance use disorders? A systematic review of the evidence. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(5), 492–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Calati R, & Serretti A (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 449–464. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty R, & Leukefeld C (2003). Risk reduction strategies to prevent alcohol and drug problems in adulthood. In Gullotta T & Bloom M M (Eds.), The encyclopedia of primary prevention and health promotion (pp. 1079–1086). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Galante J, Iribarren SJ, & Pearce PF (2013). Effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Research in Nursing, 18(2), 133–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, & Lac A (2012). How drunk am I? Misperceiving one’s level of intoxication in the college drinking environment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(1), 51. 10.1037/a0023942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison EL, & Fillmore MT (2005). Are bad drivers more impaired by alcohol?: Sober driving precision predicts impairment from alcohol in a simulated driving task. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 37(5), 882–889. 10.1016/j.aap.2005.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison EL, Marczinski CA, & Fillmore MT (2007). Driver training conditions affect sensitivity to the impairing effects of alcohol on a simulated driving test. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 15(6), 588–598. 10.1037/1064-1297.15.6.588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway FA (1995). Low-dose alcohol effects on human behavior and performance. Alcohol, Drugs & Driving, 11(1), 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Huber H, Karlin R, & Nathan PE (1976). Blood alcohol level discrimination by nonalcoholics. The role of internal and external cues. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 37(1), 27–39. 10.15288/jsa.1976.37.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, Masse M, Therien P, Bouchard V, … & Hofmann SG (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, de Wit H, McNamara PJ, & Cao D (2011). Rewarding, stimulant, and sedative alcohol responses and relationship to future binge drinking. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(4), 389–399. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, Mirza T, & Lac A (2011). Identifying factors that increase the likelihood of driving after drinking among college students. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 43(4), 1371–1377. 10.1016/j.aap.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb TR, & Nathan PE (1980). Blood alcohol level discrimination: The effects of family history of alcoholism, drinking pattern, and tolerance. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37(5), 571–576. 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780180085010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A, Slagter HA, Dunne JD, & Davidson RJ (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(4), 163–169. 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TL, Solbeck PA, Mayers DJ, Langille RM, Buczek Y, & Pelletier MR (2013). A review of alcohol‐impaired driving: The role of blood alcohol concentration and complexity of the driving task. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 58(5), 1238–1250. 10.1111/1556-4029.12227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier SE, Brigham TA, & Handel G (1984). Effects of feedback on legally intoxicated drivers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 45(6), 528–533. 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2012). Meeting in the middle: motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 25. 10.1186/1479-5868-9-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirams L, Poliakoff E, Brown RJ, & Lloyd DM (2013). Brief body-scan meditation practice improves somatosensory perceptual decision making. Consciousness and Cognition, 22(1), 348–359. 10.1016/j.concog.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz H, & Robinson CD (1988). Effects of low doses of alcohol on driving-related skills: A review of the evidence (No. HS-807 280).

- Ogurzsoff S, & Vogel-Sprott M (1976). Low blood alcohol discrimination and self-titration skills of social drinkers with widely varied drinking habits. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 8(3), 232–242. 10.1037/h0081951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, & Briñol P (2008). Psychological processes underlying persuasion: A social psychological approach. Diogenes, 55(1), 52–67. 10.1177/0392192107087917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, & van Rooijen L (1975). A self-administered short Michigan alcoholism screening test (SMAST). Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 36(1), 117–126. 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, & Freedman B (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, & Rush SE (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: A systematic review. Journal of Evidence-based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 19(4), 271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L & Sobell M (1992). Timeline Follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In Litten R & Allen J (Eds.), Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods (pp. 41–72). Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ussher M, Spatz A, Copland C, Nicolaou A, Cargill A, Amini-Tabrizi N, & McCracken LM (2014). Immediate effects of a brief mindfulness-based body scan on patients with chronic pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(1), 127–134. 10.1007/s10865-012-9466-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke NA, & Fillmore MT (2017). Laboratory analysis of risky driving at 0.05% and 0.08% blood alcohol concentration. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 175, 127–132. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke NA, & Fillmore MT (2015). Distraction produces over-additive increases in the degree to which alcohol impairs driving performance. Psychopharmacology, 232(23), 4277–4284. 10.1007/s00213-015-4055-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, & Fillmore MT (2016). Low-dose alcohol effects on measures of inhibitory control, delay discounting, and risk-taking. Current Addiction Reports, 3(1), 75–84. 10.1007/s40429-016-0086- [DOI] [Google Scholar]