Abstract

Background

Radar-guided localization (RGL) offers a wire-free, nonradioactive surgical guidance method consisting of a small percutaneously-placed radar reflector and handheld probe. This study investigates the feasibility, timing, and outcomes of RGL for melanoma metastasectomy.

Methods

We retrospectively identified patients at our cancer center who underwent RGL resection of metastatic melanoma between December 2020-June 2023. Data pertaining to patients’ melanoma history, management, reflector placement and retrieval, and follow-up was extracted from patient charts and analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Twenty-three RGL cases were performed in patients with stage III-IV locoregional or oligometastatic disease, 10 of whom had reflectors placed prior to neoadjuvant therapy. Procedures included soft tissue nodule removals (8), index lymph node removals (13), and therapeutic lymph node dissections (2). Reflectors were located and retrieved intraoperatively in 96% of cases from a range of 2 to 282 days after placement; the last reflector was not able to be located during surgery via probe or intraoperative ultrasound. One retrieved reflector had migrated from the index lesion, thus overall success rate of reflector and associated index lesion removal was 21 of 23 (91%). All RGL-localized and retrieved index lesions that contained viable tumor (10) had microscopically negative margins. There were no complications attributable to reflector insertion and no unexpected complications of RGL surgery.

Conclusion

In our practice, RGL is a safe and effective surgical localization method for soft tissue and nodal melanoma metastases. The inert nature of the reflector enables implantation prior to neoadjuvant therapy with utility in index lymph node removal.

Keywords: melanoma, metastatic melanoma lymph node dissection, subcutaneous nodule, surgical guidance, tumor localization, cutaneous oncology, neoadjuvant therapy, adjuvant therapy, radar guided reflector, SAVI Scout

Plain language summary

There are a variety of tools available to localize melanoma that had spread to deep layers of the skin or lymph nodes that can guide surgeons to the cancer when the tumor cannot be felt. We evaluated a marker that reflects radar signals that has been studied in breast surgery but not in melanoma. The marker was placed in the tumor before surgery and was located during surgery using a handheld probe, guiding the surgeon to the correct location. An advantage of the radar-reflecting marker we studied is that since it is safe to stay in the body, it can be placed ahead of the use of cancer medications and can keep track of the tumor as it responds to treatment. In a review of 23 surgeries in which the radar-reflecting marker was used, there was one case where the marker migrated away from the tumor and one case where the marker was not able to be located. Monitoring or alternative definitive treatment was provided in each of these cases. Overall, we found the marker to be an effective tumor localization tool for surgeons and safe for patients. Other marker options available are unable or less suitable to be placed a long time in advance of surgery due to either technical or safety reasons, so the radar-reflecting marker is especially useful when it is placed in a tumor ahead of medical treatment leading up to planned surgical treatment.

Introduction

For isolated locoregional or distant metastatic melanoma such as in-transit disease, recurrent nodal disease, or oligometastatic stage IV disease, surgical resection either before adjuvant therapy or after neoadjuvant therapy is a recommended treatment option. 1 For clinically detectable resectable nodal disease, current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend complete therapeutic lymph node dissection (TLND), with or without neoadjuvant therapy. 1 In most cases of clinically detectable nodal metastatic disease, anatomic landmarks are sufficient to guide the lymphadenectomy. However, some metastasectomy procedures require or at least benefit from a guidance method (eg, intraoperative ultrasound or preoperative wire localization), generally due to a nonpalpable tumor.

One procedure that may benefit from the use of a guidance or localization method is targeted index lymph node (ILN) removal after neoadjuvant therapy. Recent studies have shown the potential for ILN removal after neoadjuvant therapy to obviate the need for TLND in some patients.2,3 In the PRADO trial, patients with stage III nodal disease were treated with 6 weeks of neoadjuvant ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 3 mg/kg followed by ILN removal. Patients found to have a major pathologic response (mPR) to preoperative therapy did not undergo TLND or postoperative adjuvant therapy. This group had better 24-month relapse-free survival and distant-metastasis free survival (93% and 98%, respectively) compared with those who had pathologic partial response and underwent TLND without adjuvant therapy (64% and 64%) as well as those who had pathologic non-response and underwent TLND with adjuvant systemic therapy with or without adjuvant radiotherapy (71% and 76%). The researchers concluded that using ILN response to tailor additional surgical and systemic (adjuvant) treatment is feasible and warrants further study as a personalized approach for melanoma patients who undergo neoadjuvant therapy. 2 Compared to either ILN removal or sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy, in which only one or a few preoperatively designated and intraoperatively localized nodes are removed, TLND has higher morbidity rates, including higher risk of lymphedema. 4 The PRADO trial saw significantly fewer overall surgery-related adverse events (P < .001) as well as a lower incidence of lymphedema (P < .001) in the ILN-only group compared with those who underwent TLND. 2 These data support the consideration of ILN removal in lieu of TLND for appropriately selected patients with nodal disease, and thus, there is an unmet need for an effective localization system so that the ILN may be identified weeks or months later, even if preoperative treatment results in marked tumor shrinkage. An ideal system would allow for placement prior to neoadjuvant therapy, not impede any imaging modalities that may be required prior to surgery, and not present risk with prolonged placement – including the possibility that the localized node would never be retrieved due to the development of severe toxicity or disease progression.

For resection of nonpalpable subcutaneous nodules, several guidance methods have been utilized to intraoperatively locate the tumor and facilitate incision placement. Most of the localization approaches used to date for melanoma are similar to those utilized by breast surgeons for nonpalpable breast lesions. Traditionally, wire localization or intraoperative ultrasound have been used for surgical guidance. Wires must be placed on the day of surgery and protrude from the skin, increasing patient discomfort and chance of dislodgement, and intraoperative ultrasound relies on the visibility of the lesion in contrast to the surrounding tissue, in many cases requiring a radiologist or ultrasound technologist to assist the surgeon in the operating room. Newer alternative localization methods use a marker that is placed in advance of surgery and may be located intraoperatively with a handheld probe, with options including radioactive, magnetic, and radar-reflecting markers.

Radar-guided localization (RGL) employs the use of a small percutaneously placed radar-reflecting clip that is located intraoperatively using a handheld detection probe, which emits micro-impulse radar and employs infrared light technology to activate and localize the reflector. 5 Visual and audible cues indicate the distance from the probe to the reflector. The reflector is non-radioactive and wire-free, about the size of a medium titanium surgical clip, and its relatively inert nature and lack of imaging artifact allows it to be placed well in advance of surgery, even in advance of neoadjuvant therapy. The SCOUT® system (Merit Medical, Jordan, UT), previously called SAVI Scout, is a RGL system with United States Food and Drug Administration 510(k) clearance as a Class II-regulated device for placement in soft tissue lesions for greater than 30 days to mark a site intended for surgical removal. The use of radar guidance with the SCOUT® system has been well-studied for use in breast surgery, where it has been shown to have lower re-resection rates 6 and similar rates of margin positivity as wire localization.7,8 RGL has also been used in resection of soft tissue sarcoma and thoracoscopically for lung nodules;9,10 however, published use of RGL for melanoma is limited to one case in which RGL was used to localize a subcutaneous in-transit metastasis in a stage IIIC melanoma patient. 11 Our study represents the largest institutional series describing the efficacy of RGL for melanoma metastasectomy.

Methods

After receiving an exempt determination from the Institutional Review Board (IRB #00000971), a retrospective study was performed that included patients age 16 and older with American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage III or IV melanoma who underwent a RGL melanoma metastasectomy between December 2020 and June 2023 at our cancer center. Patients meeting these criteria were selected consecutively, eliminating potential bias. Procedures were performed by surgical oncologists in the Department of Cutaneous Oncology. Patients deemed appropriate for RGL melanoma metastasectomy had radar reflectors placed prior to surgery in either a lymph node or other stage III or stage IV soft tissue site of metastasis. The reporting of this study conforms to STROBE guidelines. 12

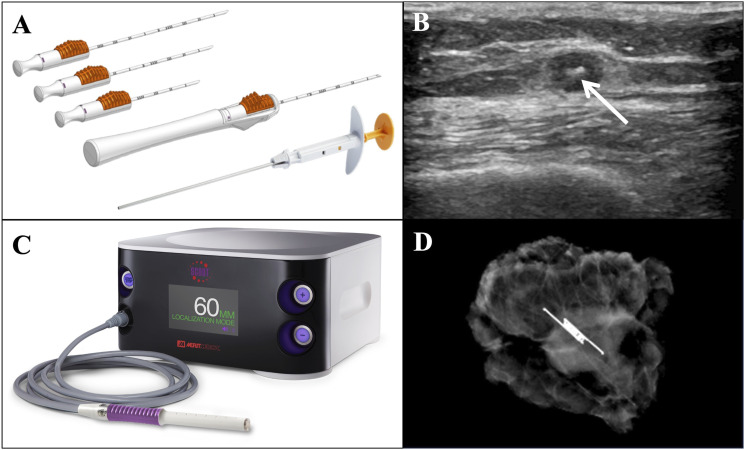

Our facility uses the SCOUT® system by Merit Medical (Jordan, UT). Reflectors are placed days to months ahead of surgery. In some cases with high suspicion of disease likely to require neoadjuvant therapy, reflectors are placed at the time of percutaneous needle biopsy. Reflector placement is performed by interventional or diagnostic radiology under local anesthesia. Using ultrasound guidance, the radiologist advances a 16-gauge needle preloaded with the radar reflector into the tumor and deploys the reflector (Figure 1A). Placement in the tumor is confirmed with at least one of the following: ultrasound imaging (Figure 1B), signal retrieval from the reflector, and/or radiography. Intraoperatively, the reflector is located using a handheld probe that emits radar signals and reflector-activating infrared light, and the system gives both auditory and visual cues to indicate distance between the probe and reflector, guiding the surgeon to the tumor (Figure 1C). The presence of the reflector in the excised tissue is confirmed using intraoperative specimen radiography (Figure 1D). All excised tissue is sent to in-house pathologists for histologic analysis.

Figure 1.

(A) SCOUT® deployment needles pre-loaded with radar reflector. Image used with permission from Merit Medical. (B) Ultrasound image after ultrasound-guided placement of radar reflector (white arrow) in subcutaneous nodule of metastatic melanoma located in the right anterior thigh. (C) SCOUT® console with handheld radar-emitting and detecting probe used intraoperatively for reflector localization. Image used with permission from Merit Medical. (D) Intraoperative specimen radiograph of subcutaneous nodule containing reflector, excised from the right hip 23 days after placement. Final pathology revealed metastatic melanoma with clear margins.

Data was collected retrospectively from patient charts and included demographics, primary melanoma characteristics, treatments prior to and after the RGL procedure, timing and characteristics of the RGL procedure, surgical pathology results, and recurrence and disease status at last follow-up. The surgical pathology report was used to assess margin status and presence of viable melanoma pathological response after neoadjuvant therapy. All patient data have been de-identified.

Staging is reported according to the AJCC eighth Edition guidelines. 13 Clear margins were defined as no microscopic disease present at the margins of the surgical specimen containing the reflector-marked nodule. For those who underwent neoadjuvant treatment, pathologic complete response (pCR) was defined as no viable tumor in the specimen, pathologic partial response (pPR) was defined as ≤50% viable tumor, and pathologic non-response (pNR) was defined as >50% viable tumor. Radiologic progression was defined as >25% enlargement of metastatic foci on imaging or development of new lesions.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics. Level of significance and power were not assigned due to study design and low sample size. For given variables, percentages or medians were used to describe central tendency, and ranges was used to describe measures of dispersion. Summary statistics are reported. Analyses were performed using Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 MSO (Version 2202 Build 14931.20660).

Results

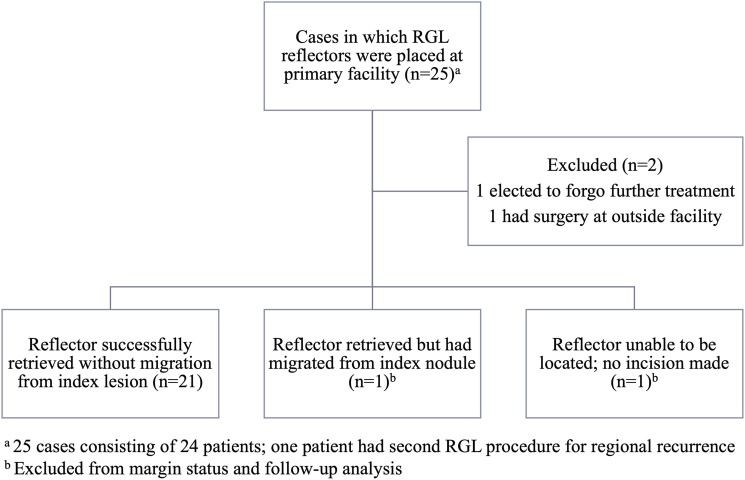

Over the course of this study, there were 25 cases in which 24 patients had radar reflectors placed in metastatic sites at our facility (one patient underwent a second RGL metastasectomy for a regional recurrence). All reflectors were placed successfully by radiology as confirmed on ultrasound, and there were no complications attributable to reflector insertion. Eight reflectors were placed on the same day as the initial needle biopsy of the metastasis due to high clinical or radiological suspicion of disease. Two cases were excluded from analysis; one patient elected to forego additional treatment after reflector placement, and another patient had their TLND performed at a different facility. Reflector placement and retrieval status, and resultant number of cases included for each portion of the analysis, are outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Summary of radar reflector placement, retrieval, and inclusion status. RGL: radar-guided localization.

Case Characteristics

Characteristics of each RGL case can be found in Table 1. All patients were white, and patients ranged in age from 16-84 years. At the time of their RGL metastasectomy, patients had either AJCC stage III (20; 87%) or IV disease (3; 13%), with stage IIIC being the most common at 39% of cases. The stage IV patients had evidence of only oligometastatic disease at the time of reflector placement. Four patients had not had a prior melanoma surgery.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Melanoma Metastasectomy Cases Performed With Radar-Guided Localization.

| Case | AJCC Stage at RGL | Sex | Age at RGL | RGL Reflector Placement Site | Metastasectomy Procedure | Neoadjuvant Therapy | Reflector Placed Before Neoadjuvant Initiated? | Days from Reflector Placement to Metastasectomy | Reflector Retrieved? | RGL Margin Status | Response to Neoadjuvant | Adjuvant Therapy | Progression or Recurrence Sites Post-RGL (if any) | Months from RGL to First Progression or Recurrence | Time to Follow-Up (Months) | Disease Status at Last Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | III | M | 79 | Axillary LN | ILNR | ICI | No | 50 | Yes | Clear | pNR | ICI | None | N/A | 4 | NED |

| 2 | IIIB | F | 83 | STN | STNR | None | N/A | 9 | Yes | Clear | N/A | ICI | R | 9 | 27 | AWD |

| 3 | IIIB | F | 84 | STN | STNR | None | N/A | 2 | Yes | Clear | N/A | ICI | R | 13 | 17 | AWD |

| 4 | IIIB | F | 84 | Axillary LN | ILNR | ICI | Yes | 223 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | ICI | None | N/A | 16 | NED |

| 5 | IIIB | M | 65 | Axillary LN | ILNR | ICI | Yes | 128 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | None | None | N/A | 19 | NED |

| 6 | IIIB | M | 50 | Inguinal LN | ILNR | ICI | Yes | 282 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | None | D | 1 | 3 | DoD |

| 7 | IIIB | F | 48 | Inguinal LN | ILNR | ICI, BRAF inhibitor | Yes | 190 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | None | R | 2 | 4 | AWD |

| 8 | IIIB | F | 53 | Cervical LN | ILNR | ICI | Yes | 134 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | None | None | N/A | 0 | NED |

| 9 | IIIC | F | 66 | STN | STNR | None | N/A | 23 | Yes | Clear | N/A | ICI | R | 8 | 16 | AWD |

| 10 | IIIC | F | 46 | Axillary LN | TLND | None | N/A | 14 | Yes | Clear | N/A | BRAF inhibitor | L, R, D | 9 | 26 | AWD |

| 11 | IIIC | F | 58 | STN | STNR | None | N/A | 20 | Yes | Clear | N/A | ICI | L, D | 5 | 30 | AWD |

| 12 | IIIC | M | 44 | Back LN | ILNR | None | N/A | 3 | Yes | Clear | N/A | ICI, XRT | None | N/A | 12 | NED |

| 13 | IIIC | F | 66 | Inguinal LN | ILNR | ICI | Yes | 137 | Yes | Clear | pPR | ICI (planned) | None | N/A | 3 | NED |

| 14 | IIIC | M | 59 | Axillary LN | ILNR | ICI | Yes | 163 | Yes | Clear | pNR | None | R, D | 3 | 13 | DoD |

| 15 | IIIC | F | 72 | Axillary LN | ILNR | ICI | Yes | 77 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | None | None | N/A | 8 | NED |

| 16 | IIIC | M | 16 | Inguinal LN | ILNR | ICI | Yes | 98 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | None | None | N/A | 0 | NED |

| 17 | IIIC | F | 61 | Cervical LN | ILNR | None | N/A | 71 | No | N/A c | N/A | None | None | N/A | 5 c | NED c |

| 18 | IIID | M | 76 | Inguinal LN | ILNR | None | N/A | 9 | Yes | NVT b | N/A | None | R | 4 | 22 | NED |

| 19 | IIID | F | 35 | Axillary LN | TLND | ICI | Yes | 96 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | None | None | N/A | 17 | NED |

| 20 | IIID | F | 67 | STN | STNR | None | N/A | 11 | Yes | N/A d | N/A | XRT d | None | N/A | 1 d | AWD d |

| 21 | IV | F | 22 | STN | STNR | None | N/A | 23 | Yes | Clear | N/A | None | D | 0 | 7 | DoD |

| 22 | IV | F | 59 | STN | STNR | BRAF inhibitor | No | 10 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | None | D | 2 | 9 | AWD |

| 23 | IV | M | 77 | STN | STNR | ICI | No | 7 | Yes | NVT a | pCR | None | None | N/A | 1 | NED |

Abbreviations: AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; AWD: alive with disease; ILNR: index lymph node removal; D: distant; M: male; DoD: dead of disease; L: local; F: female; LN: lymph node; NED: no evidence of disease; R: regional; NVT: no viable tumor; STN: soft tissue nodule; pCR: pathologic complete response; STNR: soft tissue nodule removal; pNR: pathologic non-response; TLND: therapeutic lymph node dissection; pPR: pathologic partial response; XRT: radiation therapy.

aNo viable tumor due to complete response to neoadjuvant therapy.

bNo viable tumor due to inconclusive biopsy pathology.

cReflector unable to be located intraoperatively; no incision was made. Excluded from margin status and follow-up analysis.

dReflector migrated and did not contain tumor upon excision; tumor was not excised. Patient received alternative treatment with XRT. Excluded from margin status and follow-up analysis.

The 23 metastasectomy cases consisted of 8 soft tissue nodule removals (35%), 13 targeted ILN removals (57%), and 2 TLNDs (9%). In 13 of 23 cases (57%), patients received neoadjuvant therapy leading up to metastasectomy, which consisted of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) alone (11; 85%), BRAF inhibitors alone (1; 8%), or ICIs followed by BRAF inhibitors (1; 8%). In 10 of the 13 neoadjuvant cases (77%), the reflector was placed in the index node or nodule ahead of neoadjuvant initiation. Three reflectors were placed after neoadjuvant initiation due to patient scheduling/transportation challenges (1) and placement deemed necessary after tumor shrinkage to aid in identifying the tumor at surgery (2). The median time from reflector placement to metastasectomy was 13 days for those who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy (range 2-71 days) and 128 days in those who received neoadjuvant therapy (range 7-282 days).

Reflector Retrieval, Migration Status, and Surgical Complications

Twenty-two of 23 reflectors (96%) were successfully retrieved during surgery. The reflector that was not retrieved was placed in a high level 2 cervical lymph node and was unable to be identified with radar probe or with intraoperative ultrasound, and therefore no incision was made. This patient’s index nodule had been inconclusive on initial biopsy when the reflector was placed, and imaging of the nodal basin via ultrasound has remained stable in the 5 months of close imaging follow-up. One of 22 retrieved reflectors had migrated from the site of metastasis, and as such, the tumor was not removed during the RGL removal procedure. This patient’s reflector was placed 11 days before surgery, and it is unclear at what point the reflector migrated away from the nonpalpable tumor. Stereotactic radiation to the single metastatic tumor nodule was performed in this case where the tumor was not removed with the RGL. The most common surgical complications of metastasectomy included seroma (11), surgical site pain (9), and surgical site erythema (4). Two patients experienced surgical site numbness, and 2 experienced cellulitis. Five patients reported no surgical complications. There were no unexpected complications of surgery attributable to RGL.

Margin Status, Response to Neoadjuvant Therapy, and Use of Adjuvant Therapy

As outlined in Figure 2, 21 reflectors were successfully retrieved along with the target lesion out of 23 planned procedures (91% success). Final surgical pathology results of these cases revealed negative margins (n = 10) or no viable tumor (n = 11). Of those with no viable tumor, 10 showed treatment response consistent with complete pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy, and 1 had inconclusive initial biopsy pathology which proved to be negative on final pathology when the index lesion was removed. Of the 13 patients who received neoadjuvant therapy, 10 had pCR (77%), 1 had pPR (8%), and 2 had pNR (15%). Eight patients underwent adjuvant therapy after their RGL metastasectomy with either ICIs alone (6; 75%), ICIs with radiation (1; 12.5%), or BRAF inhibitors (1; 12.5%).

Oncologic Follow-up

For the 21 successful metastasectomy cases, overall, 11 (52%) recurred or progressed at a range of 0-13 months post-procedure. Sites of progression/recurrence included one or more of local (2), regional (7), and distant (6) spread. Nine of 18 stage III patients (50%) and 2 of 3 stage IV patients (67%) progressed or recurred. By procedure type, progression or recurrence happened following 6 of 7 soft tissue removals (86%), 4 of 12 ILN removal cases (33%), and 1 of 2 TLND cases (50%). Of the 6 soft tissue removals with progression/recurrence, 5 did not receive neoadjuvant therapy, and 1 had neoadjuvant therapy with pCR; the soft tissue removal that did not recur had neoadjuvant therapy with pCR. Among all cases with neoadjuvant therapy, 4 of 13 (31%) progressed or recurred, including in 3 of 10 (30%) who had pCR (1 immunotherapy, 2 targeted therapy), zero of 1 (0%) who had pPR, and 1 of 2 (50%) who had pNR. In cases with adjuvant therapy, 5 of 8 (63%) recurred. Median survival time was not reached, and median follow-up time from surgery was 12 months. At last follow-up, 11 patients had no evidence of disease (52%), 7 were alive with disease (33%), and 3 were dead of disease (14%).

Discussion

In selecting a surgical guidance method, important factors to consider include timing of placement in relation to surgery, whether neoadjuvant therapy will be used, imaging needs, depth of the tumor, and intraoperative considerations such as instrumentation needs and availability of support for ultrasound interpretation. Traditional wire localization maintains the advantages of low cost and deep marking capability. However, wires must be placed the morning of surgery and have significant risk for dislodgment. 14 Other markers including radioactive, magnetic, and radar reflectors, in comparison, are placed ahead of surgery, which has the advantage of decoupling radiology and surgery schedules8,15 but the disadvantage if not placed on the day of biopsy of requiring an additional trip to the office for patients, some of whom live several hours away. Use of wires in the axilla has additional considerations, including proximity to sensitive structures and risk of dislodgement with arm movement. 14 With careful attention to prevent dislodgement, situations for which wire localization may be well-suited for use in melanoma include patients who have deep tumors or who do not benefit from having a marker placed in advance.

Publications on the use of localization techniques in melanoma are limited and are focused on wire localization,16-19 with few reports on use of the magnetic seed,3,20 radioactive seed, 21 and RGL. 11 In the context of breast surgery, RGL has been shown to have similar or better efficacy than alternatives including low migration rates.6,8,22 Two major advantages of RGL over alternative markers are its inert nature and lack of radiologic artifact, allowing it to remain in vivo indefinitely and not interfere with imaging or require polymer surgical instruments. While the radioactive seed and the magnetic seed may also be placed ahead of surgery, radioactive seeds present a regulatory burden in the operating room and should not remain in the body for more than 5-7 days due to radiation exposure, making placement ahead of neoadjuvant therapy impractical. 14 Magnetic seeds pose minimal safety risks and may be placed far in advance of surgery, but drawbacks include interference with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and preclusion of the use of metal surgical instruments for operating, at least while the magnetic detection probe is in use. 3 Intraoperative ultrasound has the advantage of not requiring placement of a marker, and a network meta-analysis found ultrasound guidance to have the decreased margin positivity rates (odds ratio .19, 95% confidence interval .11-.60) compared to localization techniques for breast cancer, including wire localization and radioactive seed localization; there was insufficient data on magnetic seeds and radar guidance. 23 However, drawbacks include reliance on the visibility of the lesion in contrast to the surrounding tissue and requirement of enhanced training or a radiologist or ultrasound technologist to assist the surgeon in the operating room. Ultrasound guidance may also be beneficial as contingency to have in rare cases that a pre-operatively placed marker is unable to be located with its probe.

In terms of implementation, the technical aspect of the RGL probe and system is intuitive for surgeons, as it is utilized similarly to gamma probes for SLN biopsies. The detector probe may be reused, and reflectors themselves are inexpensive, disposable, inert, nonpalpable, and not bothersome to the patient after placement. 14 When there is high suspicion of metastasis, the reflector may be placed at the time of biopsy and patients may benefit from fewer trips to the office and fewer procedures. Other studies have shown high patient and physician satisfaction with RGL in comparison with other localization methods.24-26 Though only anecdotal in our case, our surgeons report high satisfaction and ease of use of the technology.

As with all new technology, there are some limitations to use, and RGL is no exception. Rare but potential RGL complications include migration of the reflector and inability to detect the reflector secondary to either migration, deactivation, or depth exceeding the probe’s signal strength. Previous authors have reported when using RGL is deactivation by electrocautery.9,24 Lack of retrieval is also reported, but if the reflector is not removed, fortunately there are no known concerns with the reflectors remaining in the body indefinitely. With regard to deactivation, other authors have reported that by the time electrocautery was close enough to the reflector to deactivate it, the reflector had already served its purpose by guiding them to the tumor, and targeted removal could continue.9,24 In our case of inability to locate the reflector, it is unknown why the reflector deactivated, as no incision had been made, and it therefore could not have been deactivated by electrocautery. Cox et al. suggested that halogen lights (which emit in the infrared spectrum) may interfere with the detection of the reflector, but this may be mitigated with shielding, dimming, or redirecting the light, and many facilities now use LED lights which do not emit infrared radiation. 24 Migration of RGL reflectors is rare but does occur, and in one of our cases the reflector migrated from the tumor for unknown reason. An additional disadvantage of RGL is that depth restraints for attaining signal (6 cm) make it less suitable for deeper tumors. 24 The only known potential contraindication for SCOUT reflector placement is nickel allergy, as the SCOUT reflector contains a nickel alloy, nitinol. 27

The ability and safety of RGL to be placed well in advance of surgery are of increasing significance in light of the PRADO trial, which showed excellent outcomes for patients who were complete responders to neoadjuvant therapy and received ILN removal. 2 As more evidence arises supporting surgical de-escalation and fewer indications for TLND, identifying individual tumor-bearing nodes will become of high significance, and localization technologies such as RGL will play an increasingly important role in melanoma surgery. Additionally, with the growing evidence for improved outcomes with neoadjuvant therapy, 28 RGL has utility in marking tumors prior to neoadjuvant therapy, preserving the exact location of the specific node following response before resection.

Limitations of this study include small sample size, retrospective nature, single institution, and lack of a control group leading to low external validity. A prospective controlled study could shed more light on the effectiveness of RGL on achieving clear margins and keeping tumors marked without migration during the course of neoadjuvant treatment in melanoma patients. However, the success of RGL in breast surgery combined with the data presented in this manuscript lead us to conclude that RGL is a safe, effective, and efficient technique to localize and then resect metastatic melanoma lesions at any time, including after neoadjuvant treatment.

Conclusion

In our experience, RGL is a safe and effective surgical guidance method for melanoma metastasectomy with very few cases of surgical challenges. An important advantage of the technology is the inert nature of the reflector, allowing it to remain in the body indefinitely. This feature lends RGL to use in marking tumors ahead of neoadjuvant treatment, which in the case of response to treatment, keeps the shrinking tumor marked and localizable for eventual resection. As ILN removals rise in the wake of the PRADO trial, RGL may be applied to aid surgeons in removing only the index node(s). Additional advantages of RGL include decoupling of placement and surgery scheduling, ability to be placed at biopsy, infrequent reflector migration, lack of interference with MRI, and patient comfort. This study supports that RGL may be successfully used for melanoma metastasectomy, as it has been for several years in breast surgery.

Appendix.

Abbreviations

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- AWD

alive with disease

- D

distant

- DoD

dead of disease

- F

female

- ICI

immune checkpoint inhibitor

- ILN

index lymph node

- ILNR

index lymph node removal

- L

local

- LN

lymph node

- M

male

- MPR

major pathologic response

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NED

no evidence of disease

- NVT

no viable tumor

- pCR

pathologic complete response

- pNR

pathologic non-response

- pPR

pathologic partial response

- R

regional

- RGL

Radar-guided localization

- SLN

sentinel lymph node

- STN

soft tissue nodule

- STNR

soft tissue nodule removal

- TLND

therapeutic lymph node dissection

- XRT

radiation therapy

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Amod A Sarnaik is a co-inventor on a patent application with Provectus Biopharmaceuticals. Dr Sarnaik has received consulting fees from Iovance Biotherapeutics, Guidepoint, Defined Health, Huron Consulting Group, KeyQuest Health Inc, Istari, Rising Tide, and Gerson Lehrman Group. Dr Sarnaik has received speaker fees from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer, Physicians’ Educational Resource (PER) LLC, Medscape, and Medstar Health. Vernon K Sondak serves in a consulting or advisory role for Merck/Schering Plough, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Regeneron, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Alkermes, Ultimovacs, Genesis Drug Discovery and Development, and Sun Pharma. He has received research funding to the institution (Moffitt Cancer Center) from Neogene Therapeutics, Turnstone Bio, and Skyline Diagnostics, not related to this research. Jonathan S Zager has advisory board relationships with or has received fees from Merit Medical, Merck, Novartis, Philogen, Castle Biosciences, Pfizer, and Sun Pharma. He also received research funding from Amgen, Delcath Systems, Philogen, Provectus, and Novartis. He serves on the medical advisory board for Delcath Systems. John E Mullinax is an inventor on intellectual property that Moffitt Cancer Center has licensed to Iovance Biotherapeutics. He participates in sponsored research agreements with Iovance Biotherapeutics, Intellia Therapeutics, and SQZ Biotech that are not related to this research. He has received research support that is not related to this research from the following entities: NIH-NCI (K08CA252642), Ocala Royal Dames, and V Foundation. Dr Mullinax has received consulting fees from Merit Medical, Lyell Therapeutics, and Iovance Biotherapeutics. The remaining authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

IRB approval status: Reviewed and determined to be exempt by the institutional review board (Advarra, Columbia, MD, IRB #00000971, protocol MCC #21886, July 13, 2023).

Ethical Statement

Patient Consent

Due to the retrospective nature of this study, this manuscript has been determined to be exempt by the IRB with Waiver of Authorization in effect. All included data are de-identified.

ORCID iD

Kate E. Beekman https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3582-9252

References

- 1.NCCN . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Melanoma: Cutaneous. NCCN; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reijers ILM, Menzies AM, van Akkooi ACJ, et al. Personalized response-directed surgery and adjuvant therapy after neoadjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab in high-risk stage III melanoma: the PRADO trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(6):1178-1188. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01851-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schermers B, Franke V, Rozeman EA, et al. Surgical removal of the index node marked using magnetic seed localization to assess response to neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with stage III melanoma. Br J Surg. 2019;106(5):519-522. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vries M, Hoekstra HJ, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. Quality of life after axillary or groin sentinel lymph node biopsy, with or without completion lymph node dissection, in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(10):2840. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0602-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SCOUT® Surgical Guidance System Console Operation Manual; 2021. https://www.merit.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/SCOUT-Console-Operation-Manual_406025001_001.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasem I, Mokbel K. Savi Scout(R) radar localisation of non-palpable breast lesions: systematic review and pooled analysis of 842 cases. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(7):3633-3643. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chagpar AB, Garcia-Cantu C, Howard-McNatt MM, et al. Does localization technique matter for non-palpable breast cancers? Am Surg. 2022;88(12):2871-2876. doi: 10.1177/00031348211011135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srour MK, Kim S, Amersi F, Giuliano AE, Chung A. Comparison of multiple wire, radioactive seed, and savi Scout((R)) radar localizations for management of surgical breast disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(4):2212-2218. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-09159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broman KK, Joyce D, Binitie O, et al. Intraoperative localization using an implanted radar reflector facilitates resection of non-palpable trunk and extremity sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(6):3366-3374. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-09229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornella KN, Palafox BA, Razavi MK, Loh CT, Markle KM, Openshaw LE. SAVI SCOUT as a novel localization and surgical navigation system for more accurate localization and resection of pulmonary nodules. Surg Innov. 2019;26(4):469-472. doi: 10.1177/1553350619843757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke CJ, Schonberger A, Friedman EB, Berman RS, Adler RS. Image-guided radar reflector localization for small soft-tissue lesions in the musculoskeletal system. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2023;220(3):399-406. doi: 10.2214/AJR.22.28399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amin MBES, Greene F, Byrd DR, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed.. New York: Springer International Publishing: American Joint Commission on Cancer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods RW, Camp MS, Durr NJ, Harvey SC. A review of options for localization of axillary lymph nodes in the treatment of invasive breast cancer. Acad Radiol. 2019;26(6):805-819. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trent G, Tong C, Brooks AD, Goodacre R, Sataloff D, Englander B. Improving time from check-in to start with preoperative SCOUT localization. Breast J. 2021;27(6):564-566. doi: 10.1111/tbj.14223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voit C, Proebstle TM, Winter H, et al. Presurgical ultrasound-guided anchor-wire marking of soft tissue metastases in stage III melanoma patients. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27(2):129. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirley R, Uppal R, Vadodoria S, Powell B. Ultrasound-guided wire localisation for surgical excision of deep seated metastatic deposit of malignant melanoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(10):e411. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rostom M, Butterworth M. US guided wire localization of malignant melanoma subcutaneous metastases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70(9):1303-1304. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigues LK, Habib FA, Wilson M, Turek L, Kerlan RK, Leong SP. Resection of metastatic melanoma following wire localization guided by computed tomography or ultrasound. Melanoma Res. 1999;9(6):595. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clement C, Schops L, Nevelsteen I, et al. Retrospective cohort study of practical applications of paramagnetic seed localisation in breast carcinoma and other malignancies. Cancers. 2022;14(24):14246215. doi: 10.3390/cancers14246215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beniey M, Boulva K, Kaviani A, Patocskai E. Novel uses of radioactive seeds in surgical oncology: a case series. Cureus. 2019;11(9):e5706. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SN, Mango VL, Jadeja P, et al. Reflector-guided breast tumor localization versus wire localization for lumpectomies: a comparison of surgical outcomes. Clin Imag. 2018;47:14-17. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Athanasiou C, Mallidis E, Tuffaha H. Comparative effectiveness of different localization techniques for non-palpable breast cancer. A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48(1):53-59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox CE, Russell S, Prowler V, et al. A prospective, single arm, multi-site, clinical evaluation of a nonradioactive surgical guidance technology for the location of nonpalpable breast lesions during excision. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(10):3168. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5405-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wazir U, Mokbel K. De-escalation of breast cancer surgery following neoadjuvant systemic therapy. Eur J Breast Health. 2022;18(1):6-12. doi: 10.4274/ejbh.galenos.2021.2021-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tayeh S, Muktar S, Heeney J, et al. Reflector-guided localization of non-palpable breast lesions: the first reported European evaluation of the SAVI SCOUT(R) system. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(7):3915-3924. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper K, Allen E, Lancaster R, Woodard S. From the reading room to operating room: retrospective data and pictorial review after 806 SCOUT placements. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2022;51(4):460-469. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2021.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel SP, Othus M, Chen Y, et al. Neoadjuvant-adjuvant or adjuvant-only pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(9):813-823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2211437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]