Abstract

Aims:

Methadone metabolism and clearance are determined principally by polymorphic cytochrome P4502B6 (CYP2B6). Some CYP2B6 allelic variants affect methadone metabolism in vitro and disposition in vivo. We assessed methadone metabolism by CYP2B6 minor variants in vitro. We also assessed the influence of CYP2B6 variants, and P450 oxidoreductase (POR) and CYP2C19 variants, on methadone clearance in surgical patients in vivo.

Methods:

CYP2B6 and P450 oxidoreductase variants were coexpressed with cytochrome b5. Metabolism of methadone racemate and enantiomers was measured at therapeutic concentrations and intrinsic clearances determined. Adolescents receiving methadone for surgery were genotyped for CYP2B6, CYP2C19 and POR, and methadone clearance and metabolite formation clearance determined.

Results:

In vitro, CYP2B6.4 was more active than wild type CYP2B6.1. CYPs 2B6.5, 2B6.6, 2B6.7, 2B6.9, 2B6.17, 2B6.19 and 2B6.26 were less active. CYPs 2B6.16 and 2B6.18 were inactive. CYP2B6.1 expressed with POR variants POR.28, POR.5, and P228L had lower rates of methadone metabolism than wild-type reductase. In vivo, methadone clinical clearance decreased linearly with the number of CYP2B6 slow metabolizer alleles, but were not different in CYP2C19 slow or rapid metabolizer phenotypes, or in carriers of the POR*28 allele.

Conclusions:

Several CYP2B6 and POR variants were slow metabolizers of methadone in vitro. Polymorphisms in CYP2B6, but not CYP2C19 or P450 reductase, affected methadone clearance in vivo. CYP2B6 polymorphisms 516G>T and 983T>C code for canonical loss of function variants, and should be assessed when considering genetic influences on clinical methadone disposition. These complementary translational in vitro and in vivo results inform on pharmacogenetic variability affecting methadone disposition in patients.

Registered by Dr.Anshuman Sharma, ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01990573

Keywords: methadone, CYP2B6, cytochrome P4502B6, CYP2B6 polymorphisms

Introduction

Methadone is a utilitarian mu opioid receptor agonist with clinical effectiveness in neonates, children, adolescents, and adults, and application for abstinence and withdrawal syndromes, opioid agonist therapy for opioid use disorder, and treatment of acute, surgical, cancer, nociceptive, and neuropathic pain.1–7 It is used in most countries as a racemate, can be administered orally, intravenously, subcutaneously, nasally and rectally, and has an advantage of a long elimination half-life (1–2 days) which confers sustained duration of effect and need for infrequent dosing. Nevertheless, there is considerable inter- and intra-individual variability in methadone metabolism and clearance, and susceptibility to drug interactions.8, 9 This complex pharmacologic profile necessitates appropriate knowledge of methadone disposition for safe use,10 due to the risk of unanticipated accumulation and toxicity, particularly for oral use in chronic non-cancer pain.11

Methadone disposition is frequently studied, oft reviewed, and yet habitually misunderstood if not misrepresented.12, 13 The major route of methadone systemic clearance is hepatic N-demethylation to the inactive metabolite 2-ethyl-1,5-dimethyl-3,3-diphenylpyrrolidine (EDDP), and both clearance and EDDP formation are stereoselective. It is now clear that the major P450 determinant of clinical methadone metabolism is CYP2B6. This clarity, and the resolution of ambiguities and frank misperceptions, owes to high quality data, derived from human drug interaction and genetic studies in vitro and in vivo, informing on the role of various CYPs.9, 13–15

The CYP2B6 gene is highly polymorphic, with at least 38 allelic variants (https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP2B6), of which 25 are considered important, and 8 are common or unique in at least one racial or ethnic population.16, 17 We previously evaluated methadone demethylation in vitro by some expressed human CYP2B6 variants, which helped inform pharmacogenetic variability in clinical methadone metabolism and clearance.18, 19 The variants CYP2B6*6 and CYP2B6*4 are associated with altered methadone metabolism and clearance in vivo.20, 21

The obligatory redox partner in P450 catalysis, NADPH–cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR), is also polymorphic, with at least 48 allelic variants described to date (https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/POR). POR mutations may result in diseases related to diminished steroid biosynthesis and decreased activity of other P450-mediated reactions, although the influence of specific POR mutations is P450 isoform- and substrate-specific.22, 23 CYP2B6.1 activity has been reported to be decreased, unchanged, or increased by various POR variants in vitro and in vivo.22, 24, 25 The influence of POR variants on human methadone metabolism, both in vitro and in vivo, is unknown.

Owing to the importance of CYP2B6 in methadone metabolism and clearance, the current investigation pursued both in vitro and in vivo complementary approaches to further explicate the role of genetics in methadone metabolism and disposition. In vitro characterization of CYP2B6 variants included a broader range - CYPs 2B6.7, 2B6.16, 2B6.17 2B6.19, and 2B6.26. We also tested the influence of POR variants on methadone metabolism in vitro. The influence of CYP2B6 and POR polymorphisms on methadone disposition in vivo was assessed in adolescents undergoing major surgery, where full formal clearance determinations could be performed. Because the methadone drug label states that it is metabolized principally by CYP2C19, and subject to CYP2C19 drug interactions, we also assessed the influence of CYP2C19 polymorphisms on clinical methadone disposition.

Methods

Materials

Racemic methadone hydrochloride was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). rac-EDDP perchlorate and EDDP-d3 were from Cerilliant (Round Rock, Texas). R- and S-methadone were from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD). Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells and Sf-900 III SFM culture media were from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). Trichoplusia ni (Tni) cells and ESF AF culture media were from Expression Systems (Davis, CA). All other reagents were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Generation of baculovirus constructs and recombinant proteins expression

Construction of plasmids for CYP2B6, P450 reductase (POR) and cytochrome b5, site-directed mutagenesis for making CYP2B6 variants and POR variants, and generation of recombinant baculoviruses were carried out as described previously.19 Expression of recombinant proteins of CYP2B6 variants, POR variants and cytochrome b5 were carried out in insect cells by triple infection.19, 26 All CYP2B6 variants were coexpressed with POR and cytochrome b5. All CYP variants were expressed with wild-type POR and b5. All POR variants were expressed with wild-type CYP2B6 and b5. P450, POR and b5 contents for expression of each polymorphic variant were the same as reported previously.26 For each variant, protein contents of CYP2B6, POR and b5 were measured as described previously.26, 27

Methadone metabolism in vitro

All incubations were carried out in triplicate in 96-well PCR plates with raised wells in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), as adapted from published protocols with modifications.19 Racemic substrate RS-methadone, or enantiomeric substrate R- or S-methadone, was mixed with CYP2B6/POR/b5. Final concentrations of methadone enantiomers were 0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 12.5, 25, 50, 125, 250, 500 μM. Final CYP2B6 concentration was 10 pmol/ml and total reaction volume was 200 μL. After preincubation for 5 min at 37°C, the reaction (10 min, 37°C) was initiated with NADPH regenerating system (final concentrations: 10 mM glucose 6-phosphate, 1 mM ß-NADP, 1 U/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 5 mM magnesium chloride, preincubated at 37°C for 10 min)and terminated with 40 μL 20% TCA containing internal standard EDDP-d3 (final concentration 1.6 ng/ml). The plate was centrifuged (2500 rpm, 5 min) to remove precipitated proteins, and the supernatant was subjected to solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis. Preliminary experiments showed that under the assay conditions methadone demethylation was linear with time and CYP2B6 concentration.

Analysis of methadone demethylation by HPLC/tandem mass spectrometry

Calibration samples were prepared using standard of rac-EDDP. Aqueous working stock solutions of rac-EDDP were prepared at concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 μg/mL, by diluting the certified methanolic stock solution (1 mg/mL) in deionized water. Calibration standards (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000 ng/mL EDDP enantiomers) were prepared from the working stocks. Calibration standards were treated with 20% TCA containing internal standard EDDP-d3 as described above for incubation samples. Both incubation calibration samples were processed by solid-phase extraction using Strata-X-C-33 μm polymeric strong cation 96 well plate (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) as described.19, 28

To 200 μL samples in a 96-well 2.2 mL deep well plate was added 0.4 mL 5% phosphoric acid, and mixed on a titer plate shaker (Lab-Line Instruments, Melrose Park, IL). Solid-phase extraction plate was conditioned with 1 mL of methanol, and then 1 mL of 0.1 N HCl. Samples were loaded under soft vacuum (5 mmHg) at 0.5 mL /min, and the plate was washed with 1 mL of 0.1 N HCl and 1 mL of methanol. The plate was then dried under high vacuum (10 to 15 mmHg) for 1 min. Analytes were eluted with 2 × 0.5 mL of 5% ammonium hydroxide in methanol under soft vacuum, and then evaporated to dryness under nitrogen at 40 °C. Samples were reconstituted with 150 μL 20 mM ammonium formate at pH 5.7.

EDDP chiral analysis was performed on an ultra-fast liquid chromatography system (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD) composed of two LC-20AD XR pumps, DGU20A3 degasser, CBM-20A system controller, CTO-20A column oven, FCV-11AL solvent selection valve, and a SIL-20AC autosampler, coupled to an API 4000 QTrap LC-MS/MS linear ion trap triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA). Chiral chromatographic separation of EDDP was achieved by using a ChiralPak AGP analytical column (100 × 2.0mm, 5μm) equipped with a chiral AGP guard cartridge (10 × 2.0mm) (Chiral Technologies, West Chester, PA). A 0.25 μm inline filter was placed prior to the sample entering the column. The column oven was at ambient temperature and autosampler at 4 °C. Sample injection volume was 20 μL and run time 10 min. The mobile phase (0.22 mL/min) was 20 mM aqueous ammonium formate, pH 5.7 (A) and methanol (B), with a gradient program of 25% B for 3 min, linear gradient to 50% B over one min, held at 50% B for 3 min, immediately decreased to 25% B, then the column is re-equilibrated at 25% B for 2.9 min. Under these conditions, retention times for R- and S-EDDP were 4.6 and 6.3 min, respectively. The mass spectrometer was operated with a turbo spray ion source in the positive mode (ESI+) with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). Analytes were detected with the MRM transition of m/z 278.2 > 234.2 for R- and S-EDDP, and m/z 281.2 > 234.2 for R- and S-EDDP-d3. Mass spectrometry parameters were optimized as follows: curtain gas 20 psig, ion spray voltage 5500 V, source tem-perature 450°C, Gas 1 30 psig, and Gas 2 40 psig.

Clinical Studies

We report focused pharmacokinetic and pharmacogenetic data from two clinical investigations of methadone in adolescents undergoing major surgery for correction of spinal scoliosis. A venous blood sample was obtained from those subjects consenting for genetic testing.

Cohort 1 was previously reported (except for the genetic data).29 The investigation was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board and patients’ parents or legal guardian provided written informed consent, and patients provided written assent. Registration was not required. Children without history of liver and kidney disease were eligible. Methadone doses and subject ages (mean ± SD, males:females) were 0.1 mg/kg (14 ± 2 yr, 6.1 ± 1.3 mg, n=10, 2:8), 0.2 mg/kg (13 ± 2 yr, 9.9 ± 1.4 mg, n=10, 6:4), and 0.3 mg/kg (14 ± 2 yr, 17.4 ± 2.3 mg, n=11, 2:9). Methadone administration occurred 27 ± 20 min after induction of anesthesia. The remainder of the anesthetic care was per anesthesia practitioner and postoperative care was not altered for study purposes. Venous blood samples were obtained before and at 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after methadone dosing, and plasma frozen at −80°C for later analysis. Plasma methadone and EDDP concentrations were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.29, 30 Urine samples were not obtained.

Cohort 2 has not been previously reported. The protocol was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board and registered (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01990573) in 2013. Children without history of liver and kidney disease were eligible. Parents provided written informed consent and patients provided written assent. Methadone doses and subject ages (mean ± SD, males:females) were 0.3 mg/kg ideal body weight (14±2 yr, 15.8 ± 3.2 mg, n=20, 6:14) and 0.4 mg/kg ideal body weight (15±2 yr, 22.4 ± 3.1 mg, n=14, 3:11). Venous blood samples were obtained before and 0.08, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after methadone dosing, and plasma frozen at −80°C for later analysis. Urine was collected continuously for 96 hr after surgery, and an aliquot frozen at −80°C for later analysis.

Plasma methadone concentrations were quantified by solid-phase extraction and chiral liquid chromatography tandem electrospray mass spectrometry with modification of the previous method.29 Plasma (500 μl of patient plasma, calibrator, or quality controls) was acidified with 1 ml 5% phosphoric acid containing 12.5 ng methadone-D9 (Cerilliant, Round Rock, TX). . Strata X-C 33 μ Polymeric Strong Cation 30 mg plates were conditioned with 1 ml methanol. Acidified plasma was loaded, and plates washed with 1 ml 0.1N HCl then 1 ml 100% methanol, and the plate dried (full vacuum, 2–5 minutes). Samples were eluted with 0.5 ml 5% ammonium hydroxide in methanol and dried under nitrogen stream (30°C, 60 min). Samples were resuspended in 100 μl freshly prepared 20 mM ammonium formate (pH 5.7). Plasma quality control samples were 2, 10, 40, and 400 ng/ml racemic methadone. Interday coefficients of variation were 5, 4, 7, and 4% for 1, 5, 20, and 200 ng/ml R-methadone and 7, 4, 4, and 3 % for 1, 5, 20, and 200 ng/ml S-methadone.

Urine concentrations of methadone and EDDP were quantified with modification of the previous method.29 After thawing urine, a freshly prepared internal standard aqueous solution (25μl) containing 150ng/ml methadone-d9 and EDDP-d3 was added, and samples loaded onto the plates, each well acidified with 410μl of 2.5% phosphoric acid, and the sample washed with 1ml 0.1N HCl and I ml methanol. Samples were eluted with 1 ml 5% ammonium hydroxide in methanol and dried under nitrogen stream (40°C, 60 min). Samples were resuspended in 250μl freshly prepared 20mM ammonium formate (pH 5.7). Analyst 1.4.2 software (AB Sciex) was utilized for instrument control, data acquisition, and analyte mass spectrometric parameter optimization. Multiquant 3.0.1(AB Sciex) was utilized for peak integration and data analysis. Coefficients of variation were 14, 3 and 0% for 25, 150, and 500 ng/ml R-methadone and 2,1 and 0% for 25, 150, and 500 ng/ml S-methadone. Coefficients of variation were 31, 1 and 2%, for 25, 150, and 500 ng/ml R-EDDP and 14, 2 and 2% for 25, 150, and 500 ng/ml S-EDDP.

Pharmacokinetic data for both cohorts were analyzed using noncompartmental methods. (WinNonlin, Pharsight Corp, Mountain View, CA).31 Data were pooled for further analysis because the study cohorts were similar and methadone pharmacokinetics not are dose-dependent.

Genotyping

Genetic polymorphism in CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and P450 oxidoreductase alleles was determined for 58 patients (26 from cohort 1 and 32 from cohort 2). Blood samples were genotyped for the CYP2B6 polymorphisms 516G>T (rs3745274), 785A>G (rs2279343), 983T>C (rs28399499), and 1459C>T (rs3211371) to permit detection of CYP2B6*1,*4,*6,*7,*9,*16 and *18 alleles as described,21 except that CYP2B6*16 has since been consolidated into CYP2B6*18 because 983T>C is the core variant17 (although no CYP2B6*16 carriers were identified in our cohort). Subjects were assigned CYP2B6 metabolizer phenotypes based on diplotypes (https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/cyp2b6RefMaterials).32 CYP2C19 variants were measured as described.33 We assessed the 618G>A (rs4244285, CYP2C19*2), 636G>A (4986893, CYP2C19*3) and 806C>T (rs12248560, CYP219*17) variants. CYP2C19 phenotypes were based on diplotypes: ultra-rapid metabolizers (*17*17), rapid metabolizer (*1/*17), normal metabolizer (*1/*1), intermediate metabolizer (*1/*2, *1/*3, *2/*17, *3/*17), and poor metabolizers (*2/*2, *2/*3, *3/*3).34–36 Subjects were also genotyped for cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) 859G>C (rs121912974, POR*5), 541T>G (rs72552771, POR*8), 1508C>T (rs1057868, POR*28), and intron g.6593 A>G (rs2868177) variants. All genotyping was performed by the Washington University in St. Louis Genome Technology Access Center.

Data Analysis

Incubation results are the mean ± SD (three replicates). Formation of EDDP by variants was compared to wild-type by analysis of variance followed by the Holm-Sidak test, or by pairwise permutation tests with false discovery correction for multiple comparisons. EDDP formation versus substrate concentration data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis using either Michaelis-Menten model or Adair-Pauling model as described previously.18, 19, 37, 38 Results are reported as the parameter estimate ± standard error of the estimate. In vitro intrinsic clearance (Clint) was Vmax/Km.

Clinical studies were evaluated using analysis of variance followed by the Holm-Sidak test. Relationships between methadone formation or EDDP formation clearance and the number of slow metabolizer alleles were evaluated using linear regression analysis, with the null hypothesis that the slope is equal to zero.

Results

Methadone metabolism in vitro

To test CYP2B6 variants under clinically relevant conditions, racemic methadone N-demethylation was evaluated at 0.25, 0.5 and 1.25 μM. Racemic methadone blood concentrations were 100–1000 ng/mL (0.3 – 3.2 μM) in patients receiving low dose methadone for pain treatment (typically 10–20 mg) or high dose for methadone maintenance therapy for opioid dependency (50–100 mg).39 Activities of CYP2B6 variants varied widely for both R-EDDP and S-EDDP formation from racemic methadone at therapeutic concentrations (Figure 1). CYP2B6.4 showed the highest activity, which was 2-fold greater than wild-type CYP2B6.1, while all other variants had activity similar to or less than CYP2B6.1, while CYP2B6.16 and CYP2B6.18 were essentially catalytically inactive. Relative activities of the CYP2B6 variants for R-EDDP formation at therapeutic concentrations were CYP2B6.4>CYP2B6.1≥CYP2B6.5≈CYP2B6.17>CYP2B6.6≈CYP2B6.7≈CYP2B6.9≈CYP2B6.19≈CYP2B6.26>>CYP2B6.16≈CYP2B6.18. For S-EDDP formation, the order was similar except that CYP2B6.19 and CYP2B6.26 had activity comparable to CYP2B6.5 and CYP2B6.17. Methadone N-demethylation by CYP2B6 was stereoselective, with S-methadone metabolism 1.4 to 2-fold greater than R-methadone at therapeutic concentrations, and this stereoselectivity was preserved with all CYP2B6 variants.

Figure 1.

Metabolism of racemic methadone by CYP2B6 variants at therapeutic concentrations of methadone enantiomers. Results are the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations. *P<0.05 vs CYP2B6.1

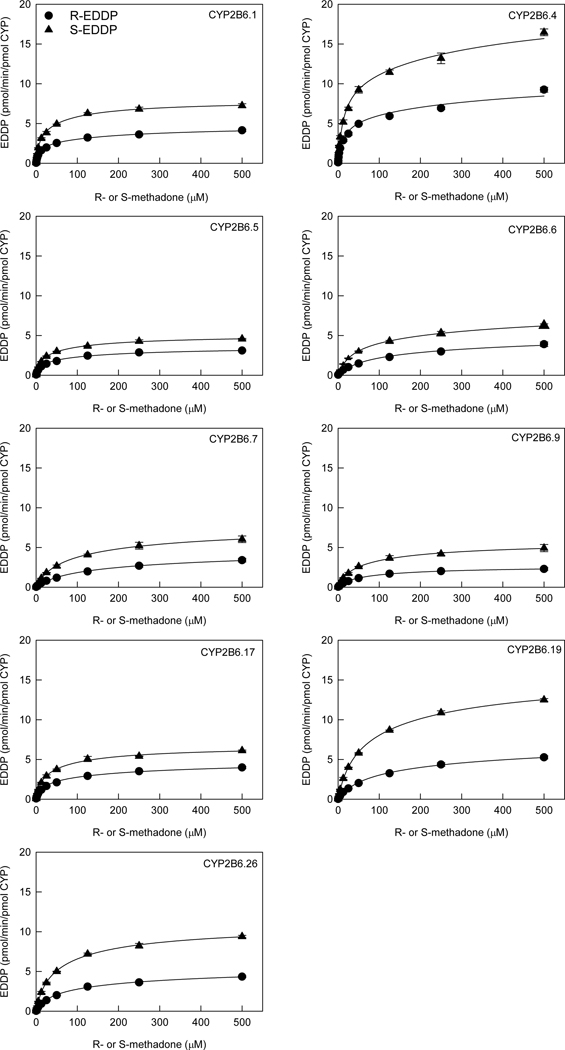

Measurement of methadone metabolism over a large concentration range enabled determination of kinetic parameters. S-EDDP formation exceeded that of R-EDDP at all substrate concentrations when racemic methadone was the substrate (Figure 2). There was a 4-fold range in Vmax values for both R- and S-EDDP formation, and Km varied 9-fold (R-EDDP) or 6-fold (S-EDDP) for the active variants (Table 1). Intrinsic clearance (Clint) for S-EDDP formation was always higher (about 2-fold) than for R-EDDP. Based on Clint values, relative activities of CYP2B6 variants for both R- and S-EDDP formation were CYP2B6.4> CYP2B6.1>CYP2B6.5≈CYP2B6.17>CYP2B6.19≈CYP2B6.26>CYP2B6.6≈CYP2B6.7≈CYP2B6.9.

Figure 2.

Metabolism of racemic methadone to EDDP by CYP2B6 variants. Symbols are R-EDDP (circles) and S-EDDP (triangles) formation from racemic methadone. Lines are predicted concentrations based on kinetic parameters obtained by nonlinear regression analysis of measured concentrations.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for EDDP formation from recemate RS-methadone catalyzed by CYP2B6 polymorphic variants.

| CYP2B6 variant | R-EDDP formation from racemic methadone | S-EDDP formation from racemic methadone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Vmax (pmol/min/pmol) | Km (μM) | Clint (ml/min/nmol) | Vmax (pmol/min/pmol) | Km (μM) | Clint (ml/min/nmol) | |

| CYP2B6.1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 14.6 ± 1.0 | 0.33 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 12.3 ± 0.5 | 0.64 |

| CYP2B6.4 | 11.1 ± 2.0 | 24.4 ± 7.4 | 0.45 | 20.5 ± 2.7 | 25.0 ± 5.3 | 0.82 |

| CYP2B6.5 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 19.6 ± 1.4 | 0.18 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 15.9 ± 0.6 | 0.32 |

| CYP2B6.6 | 5.8 ± 3.9 | 107 ± 83 | 0.054 | 8.6 ± 1.2 | 58 ± 10 | 0.15 |

| CYP2B6.7 | 5.2 ± 3.1 | 131 ± 83 | 0.040 | 7.8 ± 0.6 | 70.6 ± 5.8 | 0.11 |

| CYP2B6.9 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 50.3 ± 3.7 | 0.054 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 43.6 ± 3.4 | 0.13 |

| CYP2B6.17 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 30.2 ± 2.8 | 0.16 | 6.7 ± 0.2 | 20.6 ± 1.1 | 0.33 |

| CYP2B6.19 | 7.6 ± 1.3 | 102 ± 18 | 0.075 | 15.8 ± 0.4 | 60.0 ± 1.6 | 0.26 |

| CYP2B6.26 | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 58.8 ± 5.1 | 0.097 | 10.9 ± 0.2 | 39.0 ± 1.2 | 0.28 |

Gain of function variants are relatively rare for cytochrome P450s, and CYP2B6.4 has shown greater activity than wild-type CYP2B6.1 for some but not all substrates. Therefore methadone N-demethylation by CYP2B6.1 and CYP2B6.4 were analyzed using individual enantiomers (R- and S-methadone) (Figure 3) in addition to racemic RS-methadone (Figure 2). With individual enantiomers, unlike the racemate, S-EDDP formation exceeded that of R-EDDP at lower substrate concentrations (<4 μM), but this selectivity switched at higher substrate concentrations. CYP2B6.1-catalyzed EDDP formation from R-methadone in the racemate was much less than from R-methadone alone, with Vmax less than half that with the single enantiomer (Table 2). In contrast, S-EDDP formation from racemic substrate displayed much smaller differences from single enantiomer S-methadone. This suggests asymmetric but mutual stereoselective enantiomeric interactions in which S-methadone inhibits R-methadone demethylation, while R-methadone causes minor changes to S-methadone metabolism. This CYP2B6.4 result concords with previous observations with CYP2B6.1.37 For R-methadone, differences in both Km and Vmax for CYP2B6.4 vs CYP2B6.1 were greater for single enantiomer metabolism (~3-fold) than for the racemate (~2-fold), although both Km and Vmax were greater thus Clint values were less affected. Overall, greater metabolism of both methadone enantiomers by CYP2B6.4 contributes to greater metabolism of the racemate by CYP2B6.4 compared with CYP2B6.1.

Figure 3.

Metabolism of single enantiomers R- or S-methadone and racemate RS-methadone to EDDP catalyzed by CYP2B6.1 (left) and CYP2B6.4 (right). Symbols are R-EDDP (circles) and S-EDDP (triangles) formation from single enantiomers (blue) or racemate (black). Lines are predicted concentrations based on kinetic parameters obtained by nonlinear regression analysis of measured concentrations.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for EDDP formation from methadone enantiomers catalyzed by CYP2B6.1 and CYP2B6.4.

| CYP2B6 variant | EDDP formation from R-methadone | EDDP formation from S-methadone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Vmax (pmol/min/pmol) | Km (μM) | Clint (ml/min/nmol) | Vmax (pmol/min/pmol) | Km (μM) | Clint (ml/min/nmol) | |

| CYP2B6.1 | 13.3 ± 0.2 | 30.4 ± 1.0 | 0.44 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 0.63 |

| CYP2B6.4 | 44.5 ± 22.0 | 93.2 ± 53.0 | 0.48 | 11.8 ± 0.6 | 15.4 ± 1.3 | 0.77 |

The activity of POR variants was determined with co-expressed wild-type CYP2B6 and cytochrome b5. At therapeutic methadone concentrations, all three POR variants – POR.5 (859G>C, A287P), POR.28 (1508C>T, A503V), POR.P228L, were less active in racemic methadone demethylation compared with the wild type POR (Fig 4). Methadone metabolism over a full concentration range is shown in Fig 5 and kinetic parameters provided in Table 3. Clint values for all three POR variants POR.5, POR.28 and POR P228L were one-half to one-third those for wild type POR. The difference in Clint was mainly due to Km differences, as Vmax was less affected.

Figure 4.

Metabolism of racemic methadone catalyzed by POR variants at therapeutic concentrations of methadone enantiomers. Results are the mean ± SDof triplicate determinations. *P<0.05 vs POR.1

Figure 5.

Metabolism of racemic methadone to EDDP catalyzed by POR polymorphic variants. Symbols are R-EDDP (circles) and S-EDDP (triangles) formation from racemic methadone. Lines are predicted concentrations based on kinetic parameters obtained by nonlinear regression analysis of measured concentrations.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters for EDDP formation from racemic methadone catalyzed by POR variants.

| POR variant | R-EDDP formation from racemic methadone | S-EDDP formation from racemic methadone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Vmax (pmol/min/pmol) | Km (μM) | Clint 9(ml/min/nmol) | Vmax (pmol/min/pmol) | Km (μM) | Clint (ml/min/nmol) | |

| POR.1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 14.6 ± 1.0 | 0.33 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 12.3 ± 0.5 | 0.64 |

| POR.5 | 7.0 ± 1.1 | 45 ± 10 | 0.16 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 24.6 ± 1.3 | 0.32 |

| POR.28 | 7.5 ± 2.9 | 68 ± 32 | 0.11 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 37.0 ± 4.5 | 0.25 |

| POR P228L | 6.0 ± 1.3 | 43 ± 11 | 0.14 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 19.1 ± 1.9 | 0.35 |

Methadone disposition and genetic variability in patients

Genetic polymorphism in CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and P450 oxidoreductase alleles was determined in a sample (those patients consenting for DNA analysis) of 58 adolescents undergoing major surgery for correction of scoliosis, in which methadone was administered intraoperatively and methadone concentrations were measured for approximately 4 days and pharmacokinetic parameters formally determined. Cohort 1 (28 subjects) measured plasma methadone and EDDP concentrations, and cohort 2 (29 subjects) measured plasma methadone and urine methadone and EDDP concentrations.

Wild type CYP2B6*1/*1 was the most common allele, found in 47% of the patients. Common variants included CYP2B6*6 and one patient with the uncommon CYP2B6*18 null allele (Figure 6, A and B). Methadone enantiomer clearance was highest in wild type CYP2B6, moderately less in CYP2B6*6 carriers, and lowest in the patient with the CYP2B6*1/18 genotype, which was more apparent for S- than R-methadone. Methadone clearance was also grouped by CYP2B6 metabolizer phenotype (Fig 6, C and D), using the assignment scheme recently published (https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/cyp2b6RefMaterials).32 Grouping by the presence of a poor metabolizer allele (Fig 6, E and F) revealed a significant relationship between S- but not R-methadone clearance and the number of poor metabolizer alleles. Some subjects had urine EDDP concentrations measured, enabling the calculation of EDDP formation clearance (Fig 6, G-J). Differences in EDDP enantiomer formation clearance with genotype or allele frequencies did not reach statistical significance (P=0.058), although the sample size for this analysis was small.

Figure 6.

Relationship between CYP2B6 allelic variants and clearance of R- and S-methadone clearance and EDDP formation clearance. CYP2B19 phenotypes were based on diplotypes, as described in Methods. CYP2B6 slow metabolizer alleles in the stdy population included *6,*7,*9,*18.

Neither CYP2C19 phenotype nor P450 oxidoreductase diplotype were associated with any measure of methadone enantiomers metabolism or clearance. Methadone clearance was not significantly different in rapid, ultrarapid, intermediate or poor CYP2C19 metabolizers (Figure 7 A and B). There was no significant relationship between R- or S-methadone clearance and the number of CYP2C19 slow metabolizer alleles (P= 0.122 and 0.260, respectively, not shown). EDDP formation clearance was not significantly different in rapid, ultrarapid, intermediate or poor CYP2C19 metabolizers (Figure 7 C and D). There was no significant relationship between R- or S-EDDP formation clearance and the number of CYP2C19 slow metabolizer alleles (P= 0.721 and 0.657, respectively, not shown). There was no significant relationship between R- or S-methadone clearance and the P450 oxidoreductase diplotype, or between R- or S-EDDP formation clearance and P450 reductase diplotype.

Figure 7.

Relationship between CYP2C19 and P450 oxidoreductase allelic variants and clearance of R- and S-methadone clearance and EDDP formation clearance. CYP2C19 phenotypes were based on diplotypes, as described in Methods.

Discussion

The first major finding of this investigation was the identification of additional CYP2B6 variants with diminished R- and S-methadone N-demethylation, stereoselective aspects of variants metabolism, and additional mechanistic insights into increased methadone metabolism by CYP2B6.4. The second major finding was the considerable interindividual variability in clinical methadone metabolism and clearance, influenced by CYP2B6 polymorphism, but not by that of CYP2C19 or P450 oxidoreductase variants.

CYP2B6 variants selection was based on allele frequency and consequence. The 516G>T polymorphism (Q172H, CYP2B6*6, *7, *9, *13, *19, *20, *26, *34, *36, *37, *38) and the 785G>T polymorphism (K262R, CYP2B6*4, *6, *7, *13, *18, *19, *20, *26, *34, *36, *37, *38) are common (https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/cyp2b6RefMaterials). We studied variants with these mutations (CYP2B6*4, *6, *7, *9, *16, *19, *26), including some more common ones and those with more minor population frequency, and also other variants with relatively high allele frequency (CYP2B6*5) or of importance to specific populations (African-Americans; CYP2B6*17, *18).

CYP2B6 allelic variants exhibited altered and diverse activities towards methadone demethylation compared with wild type CYP2B6, for both R- and S-EDDP formation. Based on activity at therapeutic methadone concentrations and intrinsic clearances, CYP2B6.4 showed the highest activity among all CYP2B6 variants, and was more active than wild type CYP2B6.1. CYP2B6.5, CYP2B6.17, CYP2B6.19 and CYP2B6.26 were somewhat less active than CYP2B6.1, while CYP2B6.6, CYP2B6.7 and CYP2B6.9 had the lowest activities of the enzymatically active variants, with 12–23% of wild type activity. CYP2B6.16 and CYP2B6.18 were essentially inactive. Lower activities of methadone metabolism by CYP2B6.5, CYP2B6.6, CYP2B6.9, and CYP2B6.18 were analogous to those reported previously.18, 19 Stereoselective methadone metabolism (S>R) was observed for all CYP2B6 variants, similar to CYP2B6.1 Greater metabolism of RS-methadone by CYP2B6.4 was attributable to greater N-demethylation of both individual enantiomers.

Structure-activity relationships may exist for several key CYP2B6 mutations. The 516G>T polymorphism (Q172H, glutamine>histidine) is present in the diminished activity variants including CYP2B6.9, CYP2B6.6, CYP2B6.7, CYP2B6.19, and CYP2B6.26. Thus 516G>T may be a canonical mutation responsible for diminished methadone metabolism. Crystal structures of CYP2B6 in complex with inhibitor40 or substrate analog41 have been deduced, but it is not clear how the Q172H mutation affects catalysis in the active site. Glutamine172 is remotely positioned in the H helix, far (15Å) from the heme. It does however interact with the polar residue glutamic acid301 in the I helix, which may be involved in ligand binding. Glutamic acid301 is in the middle between glutamine172 and the substrate binding site. The Q172H mutation could affect ligand binding indirectly via interaction with glutamic acid301.

CYP2B6.4 (785A>G, K262R, lysine>arginine) is the only variant with methadone N-demethylation activity higher than CYP2B6.1. Lysine262 is at the end of a loop connecting the G and H helices, far (24Å) from the heme. The crystal structure of CYP2B6 (with engineered mutation of K262R, as in CYP2B6.4) bound with an efavirenz analog shows the arginine262 side chain in close contact with the side chains of neighboring threonine255 (G helix) and aspartic acid 266 (H helix) to form hydrogen bonding, which appears to be a part of a hydrogen bonding network with G helix histidine252 and H helix aspartic acid 263, and this network seems to link the G and H helices together.41 In wild type CYP2B6.1, the lysine262 side chain is not able to form similar hydrogen bonds with the neighboring residues. This may account for the differences in methadone metabolism by CYPs 2B6.1 and 2B6.4. Apparently the gain-of-function conferred by 785A>G exists only when K262R exists in isolation, as combination of 785A>G with other, loss-of-function mutations (as in CYP2B6.6, CYP2B6.7, CYP2B6.16, CYP2B6.19 and CYP2B6.26), resulted in lower activity.

The CYP2B6.16 and CYP2B6.18 variants were essentially inactive toward methadone. These share a common polymorphism (983T>C, I328T, isoleucine>threonine) in the J-helix. This structural change is relayed to C- and I-helices that are directly involved in ligand/heme recognition,42 and as a result, heme binding is disrupted and proteins are expressed as apoproteins only, without heme, leading to abolition of catalytic activity. In addition, the volume of the CYP2B6.18 ligand binding pocket is reduced to 14 Å3, compared with 78 Å3 for wild type CYP2B6.1.42 It is likely therefore that 983T>C is also a canonical loss of function variant for methadone metabolism, although no other variants containing this polymorphism have been identified. Of note, CYP2B6*16 was recently removed as a core allele and now is a suballele of CYP2B6*18, hence *18 may have an A or G (formerly *16) at position 785 (https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/cyp2b6RefMaterials).

CYP2B6 variant activities towards methadone were generally similar to those for other CYP2B6 substrates, for the loss of function variants but not CYP2B6.4.26, 27, 43, 44 CYP2B6.5, CYP2B6.6, CYP2B6.7, CYP2B6.9, CYP2B6.19 and CYP2B6.26 were generally less active than CYP2B6.1, and CYP2B6.16 and CYP2B6.18 were essentially inactive, towards ketamine, bupropion, and efavirenz. CYP2B6.26 (499C>G; 516G>T; 785A>G) had lesser activity than CYP2B6.1 towards R- and S-methadone, R- and S-ketamine, S-nicotine, and R- and S-bupropion. CYP2B6.4 had greater activity than CYP2B6.1 towards methadone, efavirenz,27 artemether,45 and selegiline,46 but not bupropion,44 ketamine,26 nicotine,43 cyclophosphamide,47, 48 and ifosfamide.49, 50 CYP2B6 variant activity for methadone appears most similar to that for efavirenz, among the various CYP2B6 substrates evaluated.

Influences of polymorphisms in POR, which transfers electrons from NADPH to the P450 heme in P450-catalyzed metabolism, are both substrate- and CYP isoform-dependent.22, 23 Three POR variants were studied based on allele frequency or potential mechanistic implication. POR.28 (1508C>T, A503V, alanine>valine) is the most common variant, with allele frequencies ranging from 16% in Africans to 28% in Europeans and 39% in East Asians.22 POR.28 shows somewhat less activity with CYPs 1A2, 2D6, 3A4, and 17A1, but not 2C1923 or CYP2B6 (ketamine,26 bupropion44) compared with wild-type POR. POR.5 (859G>C A287P, alanine>proline) is a common disease-causing mutation found Europeans. Alanine287 is considered critical for maintaining structural integrity, and POR.5 shows diminished binding of both FAD and FMN, and markedly less or no activity with CYPs 1A2, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4, 17A1,23 and less with S-ketamine26 but not R-ketamine or bupropion.44 POR 683C>T (P228L, proline>leucine) is rare (1–2% in Europeans), found in isolation, and does not have an allele designation, but is a component of POR*36 (683C>T, 1508C>T) and was studied because the affected residue is located in the C-terminal side of helix F connecting to the pivotal hinge region. Structural restriction caused by a proline inside the α helix might influence the connection between helix F and the hinge which is important for the conformational change needed for electron transfer.51 In the present study, all three POR variants showed lower in vitro intrinsic clearances compared with wild-type POR.1, due mainly to higher Km, for both R- and S-methadone. These results reinforce the substrate- and CYP isoform-dependent consequences of POR polymorphisms.

In adolescents undergoing major spine surgery, we observed considerable interindividal variability in methadone metabolism and clearance. Such variability has been often described. The variability in S-methadone clearance was significantly associated with CYP2B6 polymorphisms, specifically the number of CYP2B6 slow metabolizer alleles. The lowest methadone clearance was observed in a CYP2B6*18 carrier, and R- and S-EDDP formation clearance appeared numerically but not statistically lower in CYP2B6*6 carriers. These observations are consistent with previous observation that both CYP2B6*6 and CYP2B6*18 alleles conferred diminished methadone clearance.21, 52 For example, intravenous S-methadone clearance in CYP2B6*1/*6 and CYP2B6*6/*6 subjects (1.2 ± 0.4 and 0.96 ± 0.33 ml/kg/min, respectively) was significantly less than in CYP2B6*1 homozygotes (1.5 ± 0.3). R-methadone clearances in CYP2B6*6 carriers were not significantly different from CYP2B6*1/*1 subjects. Although CYP2B6*18 has been associated with increased efavirenz plasma concentrations, CYP2B6*1/*18 was considered an intermediate metabolizer phenotype.32 Nevertheless, for methadone it appeared to be a poor metabolizer in both patients. Since the first descriptions of methadone metabolism by CYP2B6,28, 53 drug interaction studies to establish the role of CYP2B6 in clinical methadone metabolism and clearance,9, 12–15, 28 and pharmacogenetic association20, 54–56 and cohort21 studies, the most reproducible result is association between the CYP2B6*6 allele and S-methadone, and to a lesser extent R-methadone, plasma concentrations.57 The present clinical results, together with the in vitro findings, are consistent with existing data on CYP2B6 polymorphisms and methadone metabolism, clearance, and plasma concentrations.

Commercial and investigational CYP2B6 genotyping in conjunction with methadone therapy often focuses on the 516G>T polymorphism, to identify slow metabolizers and risk for drug accumulation. While 516G>T is often considered a canonical CYP2B6 mutation,58 and may be the only polymorphism routinely assessed in patients or clinical studies, it appears that 983T>C is also a canonical loss of function variant, and should also be assessed along with 516G>T, if testing is performed.

The present clinical investigation found no influence of POR polymorphisms on clinical methadone metabolism or clearance. The absence of any POR variant effect in vivo contrasts with lesser metabolism in vitro by CYP2B6.1 co-expressed with POR variants (POR.5, POR.28). Both of these results are in even starker contrast to the reportedly 14–20% greater clearance of R- and S-methadone in POR*28 homozygotes, which was based on population modeling of steady-state trough or estimated peak methadone plasma concentrations.56

The present clinical investigation also found no influence of CYP2C19 polymorphisms, either loss of function (*2, *3) or gain of function (*17), as assessed by metabolizer phenotype, on clinical methadone metabolism or clearance. This was similar to a previous lack of association between CYP2C19*2 and plasma methadone concentrations,59 and between CYP2C19*2 or *3 and R- or S-EDDP/methadone ratios or S-methadone dose-corrected plasma concentrations, although higher R-methadone/dose rations were reported in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers.60 In aggregate, these clinical observations are at variance with the methadone label, which, based only on in vitro data, states that CYP2C19 is a principal determinant of methadone disposition.

Most studies of methadone disposition, including those evaluating genetic influences, use dose requirements, single-point steady-state trough plasma methadone or EDDP concentrations, or concentration/dose ratio, as clearance surrogates, or perhaps EDDP/methadone ratios as metabolism surrogates. Some use limited sampling strategies, owing to the challenges in measuring plasma concentrations for the duration needed (>4–5 days) for formal clearance determinations, because of the long methadone elimination half-life (1–2 days). This investigation measured plasma methadone, and in one cohort urine EDDP, for 96 hr, for formal determination of methadone clearance and metabolite formation clearance. The major limitation in the present investigation was the relatively small number of subjects studied, and even fewer for the outcome of EDDP formation clearance. This was more consequential for the highly polymorphic gene CYP2B6, resulting in small numbers in each genotype group. Study power was greater for the less polymorphic CYP2C19 and POR genes, which had larger gene group sizes.

In summary, combined in vitro and in vivo investigations identify CYP2B6 allelic variants with diminished methadone N-demethylation, and supports the conclusion that genetic variation in CYP2B6, but not CYP2C19 or P-450 reductase, affects methadone clearance after a single dose. The CYP2B6 polymorphisms 516G>T and 983T>C code for canonical loss of function variants, and should be assessed if considering genetic influences on clinical methadone disposition.

What is already known about this subject

Methadone is principally metabolized in vitro by cytochrome P4502B6 (CYP2B6), and CYP2B6 is the major determinant of clinical methadone clearance and metabolism.

CYP2B6 is a highly polymorphic enzyme, and some CYP2B6 allelic variants have altered activity.

Methadone is also metabolized in vitro by CYP2C19.

What this study adds

Several CYP2B6 variants were identified as slow or non-metabolizers of methadone in vitro.

Methadone clinical clearance decreased linearly with the number of CYP2B6 slow metabolizer alleles.

Methadone clinical clearance and metabolism were not different in CYP2C19 slow or rapid metabolizer phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Cooter Wright for statistical assistance

Funding statement:

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-DA042985 and R01-DA14211 to Dr. Kharasch and by the Division of Clinical and Translation Research in the Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University in St. Louis to Dr. Sharma

Footnotes

The authors confirm that the Principal Investigator for the clinical portion of this paper is Dr. Anshuman Sharma, and he had direct clinical research responsibility for study patients, and all study procedures were conducted according to Good Clinical Practice.

Competing Interests

No author has any competing interests

Conflict of interest disclosure: None

Ethics approval statement: Approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board

Patient consent statement: Parents provided written informed consent, and patients provided written assent

Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01990573

Contributor Information

Pan-Fen Wang, Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University,.

Anshuman Sharma, Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Care, University of California, San Francisco.

Michael Montana, Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis

Alicia Neiner, Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Lindsay Juriga, University of Missouri.

Kavya Narayana Reddy, Department of Pediatric Anesthesiology, Arkansas Children’s Hospital

Dani Tallchief, Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Jane Blood, Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Evan D. Kharasch, Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Hanna V, Senderovich H. Methadone in pain management: A systematic review. J Pain. 2021;22:233–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oesterle TS, Thusius NJ, Rummans TA, Gold MS. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid-use disorder. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:2072–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strang J, Volkow ND, Degenhardt L, et al. Opioid use disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kharasch ED. Intraoperative methadone: rediscovery, reappraisal, and reinvigoration? Anesth Analg. 2011;112:13–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy GS, Szokol JW. Intraoperative methadone in surgical patients: A review of clinical investigations. Anesthesiology. 2019;131:678–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tobias JD. Methadone: applications in pediatric anesthesiology and critical care medicine. J Anesth. 2021;35:130–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habashy C, Springer E, Hall EA, Anghelescu DL. Methadone for pain management in children with cancer. Paediatr Drugs. 2018;20:409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrari A, Coccia CP, Bertolini A, Sternieri E. Methadone--metabolism, pharmacokinetics and interactions. Pharmacol Res. 2004;50:551–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volpe DA, Xu Y, Sahajwalla CG, Younis IR, Patel V. Methadone metabolism and drug-drug interactions: In vitro and in vivo literature review. J Pharm Sci. 2018;107:2983–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou R, Cruciani RA, Fiellin DA, et al. Methadone safety: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society and College on Problems of Drug Dependence, in collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society. J Pain. 2014;15:321–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, Jones CM. Vital signs: risk for overdose from methadone used for pain relief - United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:493–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenblatt DJ. Drug interactions with methadone: Time to revise the product label. Clinical Pharmacol in Drug Dev. 2014;3:249–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kharasch ED. Current concepts in methadone metabolism and transport. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2017;6:125–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Younis IR, Lakota EA, Volpe DA, Patel V, Xu Y, Sahajwalla CG. Drug-drug interaction studies of methadone and antiviral drugs: Lessons learned. J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;59:1035–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kharasch ED, Greenblatt DJ. Methadone disposition: Implementing lessons learned. J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;59:1044–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Y, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Lauschke VM. Worldwide distribution of cytochrome P450 alleles: A meta-analysis of population-scale sequencing projects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102:688–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desta Z, El-Boraie A, Gong L, et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2B6. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;110:82–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gadel S, Crafford A, Regina K, Kharasch ED. Methadone N-demethylation by the common CYP2B6 allelic variant CYP2B6.6. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:709–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gadel S, Friedel C, Kharasch ED. Differences in methadone metabolism by CYP2B6 variants. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43:994–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crettol S, Deglon JJ, Besson J, et al. Methadone enantiomer plasma levels, CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9 genotypes, and response to treatment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kharasch ED, Regina KJ, Blood J, Friedel C. Methadone pharmacogenetics: CYP2B6 polymorphisms determine plasma concentrations, clearance, and metabolism. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:1142–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkhard FZ, Parween S, Udhane SS, Fluck CE, Pandey AV. P450 oxidoreductase deficiency: Analysis of mutations and polymorphisms. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;165:38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller WL. Steroidogenic electron-transfer factors and their diseases. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2021;26:138–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Pan LQ, Naranmandura H, Zeng S, Chen SQ. Influence of various polymorphic variants of cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) on drug metabolic activity of CYP3A4 and CYP2B6. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao LC, Liu FQ, Yang L, et al. The P450 oxidoreductase (POR) rs2868177 and cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2B6*6 polymorphisms contribute to the interindividual variability in human CYP2B6 activity. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72:1205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang PF, Neiner A, Kharasch ED. Stereoselective ketamine metabolism by genetic variants of cytochrome P450 CYP2B6 and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:756–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang PF, Neiner A, Kharasch ED. Efavirenz metabolism: Influence of polymorphic CYP2B6 variants and stereochemistry. Drug Metab Dispos. 2019;47:1195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kharasch ED, Hoffer C, Whittington D, Sheffels P. Role of hepatic and intestinal cytochrome P450 3A and 2B6 in the metabolism, disposition and miotic effects of methadone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:250–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma A, Tallchief D, Blood J, Kim T, London A, Kharasch ED. Perioperative pharmacokinetics of methadone in adolescents. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:1153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whittington D, Sheffels P, Kharasch ED. Stereoselective determination of methadone and the primary metabolite EDDP in human plasma by automated on-line extraction and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. J Chrom B. 2004;809:313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kharasch ED, Bedynek PS, Park S, Whittington D, Walker A, Hoffer C. Mechanism of ritonavir changes in methadone pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. I. Evidence against CYP3A mediation of methadone clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desta Z, Gammal RS, Gong L, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for CYP2B6 and efavirenz-containing antiretroviral therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106:726–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kharasch ED, Crafford A. Common polymorphisms of CYP2B6 influence stereoselective bupropion disposition. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;105:142–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hicks JK, Bishop JR, Sangkuhl K, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium (CPIC) guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;98:127–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hicks JK, Sangkuhl K, Swen JJ, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline (CPIC) for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of tricyclic antidepressants: 2016 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caudle KE, Dunnenberger HM, Freimuth RR, et al. Standardizing terms for clinical pharmacogenetic test results: consensus terms from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC). Genet Med. 2017;19:215–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Totah RA, Allen KE, Sheffels P, Whittington D, Kharasch ED. Enantiomeric metabolic interactions and stereoselective human methadone metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:389–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Totah RA, Sheffels P, Roberts T, Whittington D, Thummel K, Kharasch ED. Role of CYP2B6 in stereoselective human methadone metabolism. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:363–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Probes LM. Opioid blood levels in chronic pain management. Practical Pain Management. 2005. https://www.practicalpainmanagement.com/treatments/pharmacological/opioids/opioid-blood-levels-chronic-pain-management. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gay SC, Roberts AG, Halpert JR. Structural features of cytochromes P450 and ligands that affect drug metabolism as revealed by X-ray crystallography and NMR. Future Med Chem. 2010;2:1451–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah MB, Zhang Q, Halpert JR. Crystal structure of CYP2B6 in complex with an efavirenz analog. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobayashi K, Takahashi O, Hiratsuka M, et al. Evaluation of influence of single nucleotide polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 2B6 on substrate recognition using computational docking and molecular dynamics simulation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bloom AJ, Wang PF, Kharasch ED. Nicotine oxidation by genetic variants of CYP2B6 and in human brain microsomes. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2019:e00468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang PF, Neiner A, Kharasch ED. Stereoselective bupropion hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 CYP2B6 and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase genetic variants. Drug Metab Dispos. 2020;48:438–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Honda M, Muroi Y, Tamaki Y, et al. Functional characterization of CYP2B6 allelic variants in demethylation of antimalarial artemether. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:1860–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe T, Sakuyama K, Sasaki T, et al. Functional characterization of 26 CYP2B6 allelic variants (CYP2B6.2-CYP2B6.28, except CYP2B6.22). Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20:459–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ariyoshi N, Ohara M, Kaneko M, et al. Q172H replacement overcomes effects on the metabolism of cyclophosphamide and efavirenz caused by CYP2B6 variant with Arg262. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:2045–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raccor BS, Claessens AJ, Dinh JC, et al. Potential contribution of cytochrome P450 2B6 to hepatic 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide formation in vitro and in vivo. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zanger UM, Klein K. Pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6): advances on polymorphisms, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Front Genet. 2013;4:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calinski DM, Zhang H, Ludeman S, Dolan ME, Hollenberg PF. Hydroxylation and N-dechloroethylation of Ifosfamide and deuterated Ifosfamide by the human cytochrome P450s and their commonly occurring polymorphisms. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43:1084–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang M, Roberts DL, Paschke R, Shea TM, Masters BS, Kim JJ. Three-dimensional structure of NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase: prototype for FMN- and FAD-containing enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8411–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Talal AH, Ding Y, Venuto CS, et al. Toward precision prescribing for methadone: Determinants of methadone disposition. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0231467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerber JG, Rhodes RJ, Gal J. Stereoselective metabolism of methadone N-demethylation by cytochrome P4502B6 and 2C19. Chirality. 2004;16:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crettol S, Déglon JJ, Besson J, et al. ABCB1 and cytochrome P450 genotypes and phenotypes: Influence on methadone plasma levels and response to treatment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:668–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eap CB, Crettol S, Rougier JS, et al. Stereoselective block of hERG channel by (S)-methadone and QT interval prolongation in CYP2B6 slow metabolizers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:719–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Csajka C, Crettol S, Guidi M, Eap CB. Population genetic-based pharmacokinetic modeling of methadone and its relationship with the QTtc interval in opioid-dependent patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2016;55:1521–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crist RC, Clarke TK, Berrettini WH. Pharmacogenetics of opioid use disorder treatment. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:305–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Packiasabapathy S, Aruldhas BW, Horn N, et al. Pharmacogenomics of methadone: a narrative review of the literature. Pharmacogenomics. 2020;21:871–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carlquist JF, Moody DE, Knight S, et al. A possible mechanistic link between the CYP2C19 genotype, the methadone metabolite ethylidene-1,5-dimethyl-3,3-diphenylpyrrolidene (EDDP), and methadone-induced corrected QT interval prolongation in a pilot study. Mol Diagn Ther. 2015;19:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang SC, Ho IK, Tsou HH, et al. Functional genetic polymorphisms in CYP2C19 gene in relation to cardiac side effects and treatment dose in a methadone maintenance cohort. OMICS. 2013;17:519–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.