Abstract

Purpose

This study was designed to analyze correlations between the uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (UHR) and peripheral nerve conduction velocity (NCV) among type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients.

Patients and Methods

This was a single-center cross-sectional analysis of 324 T2DM patients. All patients were separated into a group with normal NCV (NCVN) and a group with abnormal NCV (NCVA). Patients were also classified into groups with low and high UHR values based on the median UHR in this study cohort. Neurophysiological data including motor and sensory conduction velocity (MCV and SCV, respectively) were measured for all patients.

Results

Relative to patients with low UHR values, those in the high UHR group presented with greater NCVA prevalence (P = 0.002). UHR remained negatively correlated with bilateral superficial peroneal nerve SCV, bilateral common peroneal nerve MCV, bilateral ulnar nerve SCV, and bilateral right median nerve MCV even after adjustment for confounding factors. UHR was identified as an NCVA-related risk factor, with a 1.370-fold increase in NCVA prevalence for every unit rise in UHR (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

These results identify UHR as a risk factor associated with NCVA that was independently negatively associated with NCV among T2DM patients.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes mellitus, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, peripheral nerve conduction velocity, uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is an increasingly common metabolic disease such that it represents one of the most important global public health challenges in the 21st century.1 The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) predicts that T2DM prevalence will rise to 10.9% by the year 2045, with the highest number of T2DM patients residing in China with approximately 116.4 affected individuals2–4 Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) is a complex yet common complication of T2DM that causes chronic issues in affected patients such that it represents a pressing health issue throughout the world. DPN patients can experience pain, numbness, nociceptive hypersensitivity, and other forms of discomfort,5,6 and the late diagnosis of this condition can lead to higher rates of diabetic foot ulcers, gangrene, and amputation procedures that can have serious negative effects on patient quality of life while also imposing a significant economic burden.1 As DPN is generally characterized by a nonspecific insidious onset, diagnosing it at an early stage is challenging such that missed diagnoses can occur.7 Early screening for DPN can entail analyses of nerve conduction velocity (NCV), which primarily reflects myelin sheath function,8 and entails analyses of both motor NCV (MCV) and sensory NCV (SCV).9–11

Serum uric acid (SUA) is the primary end product of the purine metabolism pathway. Elevated levels of SUA are associated with vascular dysfunction and irreversible damage with the potential to result in tissue ischemia and the impairment of peripheral nerve function.12 SUA has been demonstrated to be related to the pathogenesis of DPN in several studies, albeit with some inconsistent findings.13–15 One meta-analysis found that there is a significant association between hyperuricemia and a greater risk of DPN incidence and that DPN patients exhibit significant increases in their SUA concentrations.14 Consistently, Zhang et al16 observed similar results in a Mendelian randomization study. A separate cross-sectional analysis, however, revealed that low SUA levels can also serve as a risk factor for DPN development among T2DM patients, potentially influencing tibial nerve motor fiber function in a manner independent of the effects of HbA1c.15,17 The plasma lipoprotein high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) exhibits beneficial antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity. The SUA to HDL-C ratio (UHR) has recently been reported to offer utility as a novel metabolic and inflammatory biomarker,18 with several studies documenting an association between this ratio and diabetic nephropathy (DKD), and an increase in diabetic retinopathy (DR) risk,19,20 and diabetic control.18 UHR values can also strongly predict visceral fat area, metabolic syndrome, and the incidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

To date, there has been little research focused on the relationship between the UHR and DPN, and controversy persists with respect to the association between SUA and DPN in T2DM patients. This study was thus designed to probe the association between UHR and NCV in T2DM patients to better enable the early-stage identification of NCV-associated risk factors in order to facilitate screening for and prevention of NCV abnormalities.

Materials and Methods

Research Subjects

This was a retrospective analysis conducted in the Department of Endocrinology of Hebei Provincial People’s Hospital. Analyzed subjects consisted of 324 T2DM patients who attended this hospital between December 2020 and December 2021. Enrolled patients were those individuals who met the 1999 World Health Organization diagnostic standards for diabetes mellitus and underwent NCV testing. Patients were excluded if they had type 1 diabetes or any other type of diabetes; were pregnant or lactating; had experienced acute diabetic complications; exhibited severe lesions in vital organs including the brain, heart, kidneys, or liver; had any malignant tumors; were experiencing acute flare-ups of gout; had used diuretics, lipid-lowering drugs, or drugs with the potential to affect the absorption or excretion of uric acid within the last 3 months; or were diagnosed with any diseases with the potential to impact nerve conduction speeds, including demyelinating, hereditary, or multifocal neuropathies. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee at Hebei General Hospital (NO.2023110), and all participants completed informed consent forms before recruitment. This study was performed as per the Helsinki Declaration.

Demographic, Clinical, and Biochemical Data

All participants completed questionnaires that provided basic information including age, gender, and duration of disease. A trained professional measured the weight, height, body mass index (BMI), and systolic/diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) of each participant two times, recording the mean values. Samples of blood were collected from subjects after fasting for 8 h and processed with a fully automated biochemical analyzer in the laboratory to analyze parameters including total cholesterol, triglyceride (TG) levels, HDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), UA levels, fasting blood glucose (FBG), albumin (ALB), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), azelaic aminotransferase (AST), and creatinine (SCr). A nuclear medicine laboratory physician measured patient glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and vitamin D levels via an electrochemiluminescence approach. The UHR (%) was calculated as follows: UA (μmol/L)/HDL-C (mmol/L) × 100%.

All neurophysiological analyses were performed by a specialized neurologist who conducted NCV studies that included measurements of MCV for the bilateral median, ulnar, and common peroneal nerves as well as measurements of SCV for the bilateral median, ulnar, and superficial peroneal nerves.

Patient Grouping

All participants in this study were classified into two groups based on whether or not they exhibited normal NCV values (See Table 1), including a normal peripheral nerve conduction (NCVN) group and an abnormal peripheral nerve conduction (NCVA) group.7 Participants were additionally classified into two groups based on the median UHR into those with a high UHR (UHR ≥ 0.22) and those with a low UHR (UHR < 0.22).

Table 1.

The Specific Normal Value of the Nerve Conduction Velocity

| Dantec Keypoint Normal Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75–84 |

| Ulnar MCV (m/s) | 61 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 58 | 52 |

| Media MCV (m/s) | 56 | 55 | 54 | 52 | 51 | 50 | 50 |

| Common peroneal MCV (m/s) | 43 | ||||||

| Ulnar SCV (m/s) | 47.4 | 46.6 | 45.8 | 45 | 44.2 | 43.3 | 42.9 |

| Media SCV (m/s) | 49.5 | 48.6 | 47.5 | 46.5 | 45.4 | 44.4 | 43.4 |

| Superficial peroneal SCV (m/s) | 40 |

Notes: If the nerve conduction velocity is less than the above indexes, the conduction velocity is abnormal.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0. Distribution normality testing was performed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and continuous variables were presented as means ± SD or medians (interquartile range). Categorical variables were instead presented as numbers (%). Biochemical parameters were compared using Student’s t-tests or Mann–Whitney U-tests, whereas chi-square tests were used when comparing categorical variables. Spearman or Pearson correlation analyses were used to probe the relationship between UHR and NCV, while the status of UHR as a risk factor for abnormal peripheral nerve conduction was assessed through logistic regression analyses. Independent correlations between UHR and NCV measures were also assessed through multiple linear regression analyses. P < 0.05 was regarded as being statistically significant.

Results

Participant Characteristics

This study enrolled 324 T2DM participants (215 male, 109 female), with a mean age of 56.00 years, a mean T2DM duration of 7 years, and a mean BMI of 26.19 kg/m2. These participants also exhibited a mean UA of 307.50 µmol/L, a mean HDL-C of 1.13 mmol/L, a mean FBG of 8.00 mmol/L, a mean HbA1c of 8.50%, and a mean vitamin D level of 16.16 ng/mL. Of these patients, 146 (45.06%) were classified into the NCVA group whereas 178 (54.94%) were in the NCVN group. In addition, 162 patients (50.00%) exhibited high UHR values, and the overall mean UHR was 0.22 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of General Information and Clinical Indicators of All Participants

| Characteristics | Subjects (n=324) |

|---|---|

| Male (%) | 215 (66.36%) |

| Age (year) | 56.00 (47.25,66.00) |

| DM duration (year) | 7.00 (2.00,14.00) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.19 (23.77,28.24) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 133.00 (120.00,146.75) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 82.00 (74.00,90.00) |

| ALB (g/L) | 41.00 (38.70,43.68) |

| ALT (U/L) | 18.60 (13.73,27.28) |

| AST (U/L) | 19.25 (15.90,24.50) |

| SCr (mmol/L) | 71.92 (64.10,81.20) |

| UA (μmol/L) | 307.50 (247.95,361.18) |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.40 (4.50,6.50) |

| GFR (mL/min) | 93.85 (83.67,104.37) |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.76 (4.04,5.50) |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.43 (1.05,2.10) |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.85 (1.64,3.44) |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.13 (0.92,1.54) |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 8.00 (6.40,10.88) |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.50 (7.20,10.08) |

| VitaminD (ng/mL) | 16.16 (13.00,20.53) |

| UHR (%) | 0.22 (0.17,0.30) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ALB, albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; SCr, scrum creatinine; UA, uric acid; BUN, urea nitrogen; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; UHR, uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio.

Comparisons of NCVN and NCVA Patient Characteristics

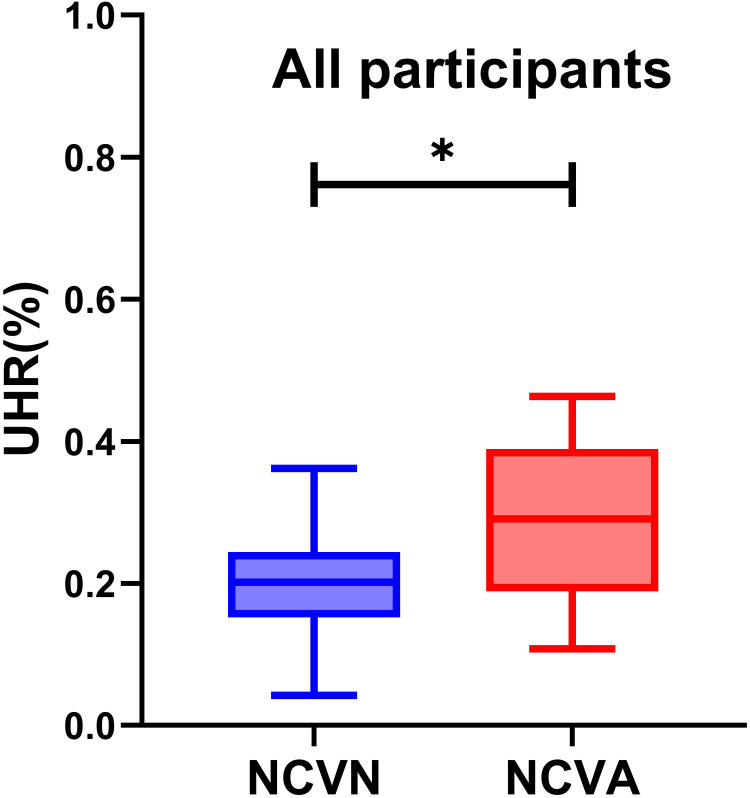

A higher proportion of males was evident in the NCVA group relative to the NCVN group (P=0.002). Patients exhibited significantly higher mean age, DM duration, UA, and HbA1c levels in the NCVA group relative to the NCVN group (P<0.05), whereas the opposite was true for ALB, ALT, AST, and HDL-C levels (P < 0.05). The UHR levels of NCVA group patients were significantly higher than those of NCVN group patients (P<0.001) (Table 3). Variations in UHR levels between these two groups of patients are presented in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Comparison of Indicators Between the NCVN and NCVA Groups

| Variable | NCVN (n=178) | NCVA (n=146) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male (113,63.48%) | Male (103,70.55%) | 0.002* |

| Age | 54.99±11.93 | 58.87±11.67 | 0.023* |

| DM duration | 6.00 (2.00,13.00) | 10.00 (3.00,16.00) | 0.012* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.23±3.91 | 26.41±3.55 | 0.665 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 133.68±20.50 | 134.79±20.36 | 0.418 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 81.50 (75.00,89.75) | 81.26±13.35 | 0.399 |

| ALB (g/L) | 41.81±3.08 | 40.17±3.93 | <0.001* |

| ALT (U/L) | 20.05 (14.53,29.73) | 17.35 (12.20,25.45) | 0.020* |

| AST (U/L) | 20.10 (16.50,24.98) | 18.65 (14.70,23.75) | 0.042* |

| SCr (mmol/L) | 71.20 (64.61,79.98) | 73.40 (63.46,83.20) | 0.031* |

| UA (μmol/L) | 310.54±89.17 | 314.31±91.69 | 0.316 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.50 (4.60,6.40) | 5.40 (4.40,6.59) | 0.690 |

| GFR (mL/min) | 96.65 (87.05,105.55) | 91.92 (78.88,103.23) | 0.067 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.78 (4.04,4.78) | 4.71 (4.03,5.45) | 0.498 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.42 (1.02,2.08) | 1.52 (1.07,2.19) | 0.808 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.79 (1.55,3.39) | 2.88 (2.02,3.49) | 0.392 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.20 (0.95,1.76) | 1.05 (0.88,1.43) | 0.006* |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 7.75 (6.34,10.28) | 8.71 (7.00,8.71) | 0.070 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.20 (7.00,9.60) | 8.80 (7.83,10.63) | <0.001* |

| VitaminD (ng/mL) | 16.58 (13.41,21.42) | 15.88 (12.83,19.48) | 0.101 |

| UHR (%) | 0.20 (0.15,0.24) | 0.30±0.14 | <0.001* |

Note: *Denotes significance at a P value of <0.05.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ALB, albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; SCr, scrum creatinine; UA, uric acid; BUN, urea nitrogen; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; UHR, uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of UHR levels in normal peripheral nerve conduction group and abnormal peripheral nerve conduction group in patients with T2DM.*Denotes significance at a P value of <0.05.

Comparisons of the Characteristics of Patients with High and Low UHR Values

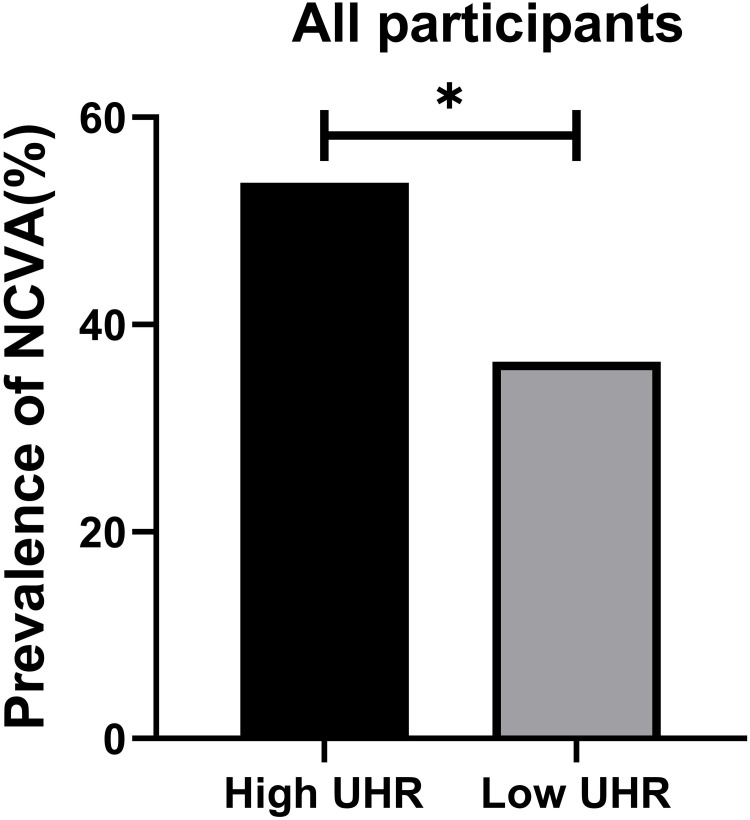

There were significantly more males in the high UHR patient group compared to the low UHR group (P<0.001). High UHR patients also presented with significantly lower age, TC, and HbA1c levels relative to the low UHR group, whereas the opposite was true for BMI, ALB, ALT, SCr, UA, BUN, TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C levels (P<0.05). As expected, significantly higher UHR values were evident in the high UHR group (P<0.001). NCVA prevalence was also significantly greater in the high UHR group (P=0.002) (Table 4). Differences in the prevalence of NCVA between the high and low UHR groups are presented in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Comparison of Indicators Between the Low UHR and High UHR Groups

| Variable | High UHR (n=162)2 | Low UHR (n=162)1 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male (124, 76.54%) | Male (91, 56.17%) | <0.001* |

| Age | 54.99±12.88 | 58.00 (51.00,66.00) | 0.010* |

| DM duration | 7.50 (2.75,13.00) | 7.00 (2.00,15.00) | 0.934 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.05±3.48 | 25.55 (22.98,27.67) | <0.001* |

| SBP (mmHg) | 134.41±18.73 | 133.92±21.95 | 0.610 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 83.00 (75.00,91.00) | 80.00 (73.00,88.00) | 0.086 |

| ALB (g/L) | 41.47±3.42 | 40.77±3.66 | 0.020* |

| ALT (U/L) | 20.00 (14.58,32.55) | 17.65 (12.35,24.55) | 0.008* |

| AST (U/L) | 19.85 (16.10,26.73) | 19.30 (15.93,23.78) | 0.224 |

| SCr (mmol/L) | 75.19 (67.24,83.20) | 68.75 (61.73,77.73) | <0.001* |

| UA (mmol/L) | 348.85 (296.86,401.17) | 255.20 (209.55,23.80) | <0.001* |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.53 (4.71,6.70) | 5.35 (4.40,6.35) | 0.031* |

| GFR (mL/min) | 94.71 (81.18,106.91) | 95.04 (86.18,102.78) | 0.930 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.67 (3.97,5.30) | 5.02±1.32 | 0.022* |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.69 (1.15,2.57) | 1.32 (0.96,1.79) | <0.001* |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.06±0.79 | 2.17 (1.13,3.24) | <0.001* |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.95 (0.84,1.07) | 1.51 (1.20,3.10) | <0.001* |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 7.95 (6.55,10.35) | 8.19 (6.45,11.90) | 0.253 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.25 (7.10,9.78) | 8.80 (7.43,10.38) | 0.035* |

| VitaminD (ng/mL) | 17.13±5.84 | 16.01 (13.34,20.55) | 0.792 |

| UHR (%) | 0.31 (0.25,0.39) | 0.18 (0.11,0.21) | <0.001* |

| Prevalence of NCVA | NCVA 87 (53.70%) | NCVA 59 (36.41%) | 0.002* |

Notes: *Denotes significance at a P value of <0.05.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ALB, albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; SCr, scrum creatinine; UA, uric acid; BUN, urea nitrogen; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; UHR, uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of prevalence of abnormal peripheral nerve conduction in the High UHR group and Low UHR group for all participants. *Denotes significance at a P value of <0.05.

Correlations Between UHR and NCV in T2DM Patients

A negative correlation between UHR and bilateral ulnar nerve MCV, right median nerve MCV, bilateral common peroneal nerve MCV, right ulnar nerve SCV, and bilateral superficial peroneal nerve SCV was detected in all participants (P < 0.05). In contrast, UHR values were not correlated with left median nerve MCV, left ulnar nerve SCV, or bilateral median nerve SCV (Table 5).

Table 5.

The Correlation of UHR and NCV in Patients with T2DM

| UHR | ||

|---|---|---|

| Left ulnar nerve MCV | r-value | −0.206 |

| P-value | <0.001* | |

| Right ulnar nerve MCV | r-value | −0.180 |

| P-value | 0.001* | |

| Left median nerve MCV | r-value | −0.046 |

| P-value | 0.441 | |

| Right median nerve MCV | r-value | −0.120 |

| P-value | 0.031* | |

| Left common peroneal nerve MCV | r-value | −0.192 |

| P-value | 0.001* | |

| Right common peroneal nerve MCV | r-value | −0.133 |

| P-value | 0.017* | |

| Left ulnar nerve SCV | r-value | −0.027 |

| P-value | 0.637 | |

| Right ulnar nerve SCV | r-value | −0.126 |

| P-value | 0.026* | |

| Left median nerve SCV | r-value | −0.104 |

| P-value | 0.068 | |

| Right median nerve SCV | r-value | −0.050 |

| P-value | 0.384 | |

| Left superficial peroneal nerve SCV | r-value | −0.165 |

| P-value | 0.005* | |

| Right superficial peroneal nerve SCV | r-value | −0.129 |

| P-value | 0.027* | |

Note: *Denotes significance at a P value of <0.05.

Abbreviations: MCV, motor conduction velocities; SCV, sensory conduction velocities.

Multiple Linear Correlation Analyses of the Relationship Between NCV and UHR

In the overall patient population included in this study, when using the unadjusted model 1 (Table 6), model 2 (adjusted for age, BMI, DM duration, SBP, Alb) (Table 7), and model 3 (additionally adjusted for SCr, BUN, TG, TC, LDL-C, HbA1c) (Table 8), UHR values were negatively correlated with bilateral ulnar nerve MCV, right median nerve MCV, bilateral common peroneal nerve MCV, right ulnar nerve SCV, and bilateral superficial peroneal nerve SCV. UHR remained unrelated to left median nerve MCV, left ulnar nerve SCV, or bilateral median nerve SCV under any of these models.

Table 6.

Correlation of UHR with Different Nerve Conduction Velocities in Patients with T2DM in Model 1

| B (95% CI) | Std.Error | Beta | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left ulnar nerve MCV | −0.857 (−1.347, −0.367) | 0.249 | −0.190 | −3.444 | 0.001* |

| Right ulnar nerve MCV | −0.836 (−1.311, −0.361) | 0.241 | −0.191 | −3.463 | 0.001* |

| Left median nerve MCV | −0.253 (−0.658, 1.580) | 0.207 | −0.068 | −1.206 | 0.229 |

| Right median nerve MCV | −0.498 (−0.904, −0.092) | 0.206 | −0.135 | −2.417 | 0.016* |

| Left common peroneal nerve MCV | −0.780 (−1.178, −0.382) | 0.202 | −0.215 | −3.861 | <0.001* |

| Right common peroneal nerve MCV | −0.585 (−0.979, −0.191) | 0.205 | −0.164 | −2.290 | 0.004* |

| Left ulnar nerve SCV | −0.048 (−0.580, 0.484) | 0.270 | −0.010 | −1.179 | 0.858 |

| Right ulnar nerve SCV | −0.594 (−1.113, −0.055) | 0.273 | −0.124 | −2.117 | 0.031* |

| Left median nerve SCV | −0.552 (−1.178, −0.382) | 0.328 | −0.096 | −1.682 | 0.094 |

| Right median nerve SCV | −0.240 (−0.928, 0.448) | 0.349 | −0.040 | −0.687 | 0.493 |

| Left superficial peroneal nerve SCV | −0.843 (−1.385, −0.301) | 0.275 | −0.180 | −3.065 | 0.002* |

| Right superficial peroneal nerve SCV | −0.666 (−1.267, −0.064) | 0.305 | −0.128 | −2.178 | 0.003* |

Note: *Denotes significance at a P value of <0.05.

Table 7.

Correlation of UHR with Different Nerve Conduction Velocities in Patients with T2DM in Model 2

| B (95% CI) | Std.Error | Beta | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left ulnar nerve MCV | −0.911 (−1.406, −0.416) | 0.251 | −0.202 | −3.622 | <0.001* |

| Right ulnar nerve MCV | −0.920 (−1.396, −0.445) | 0.242 | −0.211 | −3.807 | <0.001* |

| Left median nerve MCV | −0.285 (−0.692, 1.208) | 0.206 | −0.077 | −1.383 | 0.168 |

| Right median nerve MCV | −0.526 (−0.924, −0.127) | 0.202 | −0.143 | −2.598 | 0.010* |

| Left common peroneal nerve MCV | −0.834 (−1.221, −0.446) | 0.196 | −0.230 | −4.239 | <0.001* |

| Right common peroneal nerve MCV | −0.645 (−1.029, −0.262) | 0.194 | −0.181 | −3.316 | 0.001* |

| Left ulnar nerve SCV | −0.245 (−0.753, 0.262) | 0.258 | −0.052 | −0.952 | 0.342 |

| Right ulnar nerve SCV | −0.785 (−1.315, −0.256) | 0.269 | −0.163 | −2.920 | 0.004* |

| Left median nerve SCV | −0.517 (−1.133, −0.099) | 0.313 | −0.090 | −1.650 | 0.100 |

| Right median nerve SCV | −0.283 (−0.942, 0.375) | 0.334 | −0.047 | −0.848 | 0.397 |

| Left superficial peroneal nerve SCV | −0.942 (−1.483, −0.401) | 0.274 | −0.201 | −3.427 | 0.001* |

| Right superficial peroneal nerve SCV | −0.808 (−1.406, −0.211) | 0.303 | −0.156 | −2.665 | 0.008* |

Note: *Denotes significance at a P value of <0.05.

Table 8.

Correlation of UHR with Different Nerve Conduction Velocities in Patients with T2DM in Model 3

| B (95% CI) | Std.Error | Beta | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left ulnar nerve MCV | −1.316 (−1.889, −0.744) | 0.290 | −0.292 | −4.527 | <0.001* |

| Right ulnar nerve MCV | −1.346 (−1.898, −0.793) | 0.344 | −0.280 | −4.795 | <0.001* |

| Left median nerve MCV | −0.640 (−1.104, −0.180) | 0.2337 | −0.174 | −2.741 | 0.106 |

| Right median nerve MCV | −0.998 (−1.463, −0.533) | 0.236 | −0.271 | −4.225 | <0.001* |

| Left common peroneal nerve MCV | −0.778 (−1.240, −0.315) | 0.235 | −0.214 | −3.309 | 0.001* |

| Right common peroneal nerve MCV | −0.484 (−0.935, −0.033) | 0.229 | −0.135 | −2.112 | <0.001* |

| Left ulnar nerve SCV | −0.332 (−0.934, 0.288) | 0.310 | −0.069 | −1.039 | 0.300 |

| Right ulnar nerve SCV | −0.708 (−1.347, −0.069) | 0.324 | −0.147 | −2.184 | 0.030* |

| Left median nerve SCV | −0.570 (−1.302, 0.162) | 0.372 | −0.099 | −1.533 | 0.126 |

| Right median nerve SCV | −0.164 (−0.947, 0.618) | 0.397 | −0.027 | −0.414 | 0.679 |

| Left superficial peroneal nerve SCV | −0.770 (−1.419, −0.120) | 0.329 | −0.164 | −2.336 | 0.020* |

| Right superficial peroneal nerve SCV | −0.412 (−1.129, 0.304) | 0.364 | −0.168 | −1.132 | 0.020* |

Note: *Denotes significance at a P value of <0.05.

Binary Logistic Regression Analyses of the Association Between NCV and UHR

Here, binary logistic regression analyses were used to probe the associations between UHR and NCV. This model incorporated age, T2DM duration, Alb, HbA1c, and UHR, and it revealed that UHR was a risk factor for NCVA, with a 1.370-fold rise in NCVA risk for each unit increase in UHR (P < 0.001) (Table 9).

Table 9.

Dichotomous Logistic Regression of Risk Factors for Abnormal Peripheral Nerve Conduction Velocity in T2DM Patients

| B (95% CI) | Std.Error | Wald | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.021 (1.003,1.040) | 0.009 | 5.128 | 0.148 |

| DM duration | 1.052 (1.014,1.091) | 0.019 | 7.279 | 0.007* |

| ALB (g/L) | 0.862 (0.797,0.933) | 0.040 | 3.658 | <0.001* |

| HbA1c (%) | 1.308 (1.138,1.504) | 0.071 | 4.301 | <0.001* |

| UHR | 1.370 (1.065,1.632) | 0.344 | 3.511 | <0.001* |

Note: *Denotes significance at a P value of <0.05.

Discussion

T2DM is emerging as an increasingly serious threat to global health, and DPN is among the most common, difficult-to-manage, and serious complications affecting T2DM patients.21 DPN is associated with a greater risk of ulcer formation, food infections, and noninvasive amputations resulting in long term disability, greater treatment costs, and a loss of normal function that impose a large societal burden.22 The pathogenesis entails chronic neurological damage as a result of a range of injuries to endothelial cells, glia, and axons.3 While further work is necessary to fully clarify the mechanisms underlying DPN development and progression, prior reports have demonstrated that a range of inflammatory and metabolic insults stemming from dysregulated polyol and inositol metabolism, abnormal glucolipid metabolism, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammatory factor activation contribute to neurological dysfunction in affected patients.5

The UHR has previously been validated as a stable inflammation-related biomarker that is closely associated with the control of DR,18 in addition to predicting MS onset.23 Here, T2DM patients exhibiting high UHR values were found to be at a greater risk of NCVA development, with UHR levels being independently and negatively associated with NCV. In line with results reported previously by Lin et al24 the present study confirmed the utility of high UHR values as an independent risk factor for NCVA incidence. There are several potential mechanisms underlying this relationship that are discussed below.

High UA levels may increase the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS),25 with ROS-mediated oxidative stress potentially resulting in DNA damage and membrane lipid peroxidation in neuronal cells, in line with evidence that Schwann cells can undergo apoptotic death when exposed to oxidative stress.26 This mechanism may culminate in the death of neurons and the consequent incidence of neurological dysfunction. In one report, SUA levels were shown to promote inflammatory pathway activation, with elevated levels of SUA being positively correlated with the levels of inflammatory mediators including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and C-responsive protein.27,28 SUA is also capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier and triggering NFκB pathway-mediated inflammation,29 leading to inflammatory neuronal injury that may underlie the incidence of DPN. Khosla et al found that neuroendothelial cell nitric oxide (NO) production was influenced by levels of UA in the blood,30 resulting in the dilation of blood vessels and the enhancement of local tissue perfusion, with insufficient NO potentially resulting in nerve ischemia and hypoxia, thereby contributing to the dysfunction of endothelial cells and the incidence or progression of DPN.31

HDL-C is generally regarded as a protective factor associated with a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease, exhibiting anti-thrombotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-atherosclerotic, antioxidant, and cholesterol transport reversing activities.32,33 Several recent reports have noted that lower HDL-C levels are related to greater T2DM prevalence such that they can be used to predict T2DM risk. Smith et al also noted that neuropathy occurrence was correlated to the levels of both LDL-C and HDL-C.34 Higher cholesterol levels may offer particular value for the stimulation of injuries to the peripheral nervous system, particularly for myelinated large fibers. HDL-C, as a cholesterol carrier, can protect against neuroglial apoptosis as a result of cholesterol accumulation through its ability to transport cholesterol within these cells.24 One experiment demonstrated that impaired lipid metabolism can drive localized mitochondrial dysfunction together with the induction of local and systemic oxidative stress responses, contributing to neurological damage and DPN.35

Aktas et al additionally noted a strong positive relationship between UHR values and HbA1c levels, concluding that HR can be used to predict glycemic control in male T2DM patients. Effective glycemic control can lead to improvements in NCV and vibrational sensitivity, whereas individuals with levels of blood glucose that are poorly controlled may exhibit advanced glycation end product (AGE) formation and receptor activity, in turn driving the production of high nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) levels.36 This can subsequently activate the poly(ADP ribose) polymerase, hexosamine, and protein kinase C(PKC) pathways,37 worsening oxidative stress and associated inflammation and neuronal dysregulation, thus impacting endothelial cell function and contributing to NCV deterioration.18,38

This study is also subject to multiple limitations. For one, as a single-center retrospective cross-sectional analysis, these results were subject to hospitalization bias and do not offer insight into the causal link between UHR and NCV. Second, this study did not take the glucose-lowering regimens of individual patients into account despite the possible effects of these regimens on SUA levels, despite the potential impact of metformin on these levels and neuropathy risk. Similarly, other T2DM complications were not evaluated. Moreover, the treatment regimens for hyperuricemia and DPN were insufficiently evaluated, potentially confounding the results of these analyses as one prior study of T2DM patients that did not receive UA-lowering treatment found that lower SUA levels were associated with greater DPN risk, with reduced SUA concentrations potentially impacting tibial neuromotor fiber function. This latter point contradicts the findings of the present study. Additional large-scale multicenter prospective cohort studies will thus be essential to gather detailed information regarding T2DM patient treatment regimens so that the potential mechanistic link between UHR values and NCV can be probed with greater detail, thereby aiding diagnostic and treatment efforts.

Conclusion

In summary, the present results revealed that the UHR levels of T2DM patients with DPN were significantly increased as compared to patients without this diabetic complication. UHR values and NCV remained negatively correlated even with adjustment for relevant confounding factors, with greater NCVA prevalence among individuals with a high UHR. NCVA incidence rose by 1.370-fold for each unit increase in UHR, emphasizing the status of this ratio as a risk factor for abnormal nerve conduction. Additional prospective research, however, will be vital to validate and characterize the relationship linking UHR and DPN.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Li Y, Teng D, Shi X, et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American Diabetes Association: national cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369:m997. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reed J, Bain S, Kanamarlapudi V. A review of current trends with type 2 diabetes epidemiology, aetiology, pathogenesis, treatments and future perspectives. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2021;14:3567–3602. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S319895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sher EK, Prnjavorac B, Farhat EK, Palić B, Ansar S, Sher F. Effect of diabetic neuropathy on reparative ability and immune response system. Mol Biotechnol. 2023. doi: 10.1007/s12033-023-00813-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C, Wang W, Ji Q, et al. Prevalence of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a nationwide cross-sectional study in mainland China. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2023;198:110602. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sloan G, Selvarajah D, Tesfaye S. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management of diabetic sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(7):400–420. doi: 10.1038/s41574-021-00496-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zilliox LA. Diabetes and peripheral nerve disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2021;37(2):253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2020.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, Gao Y, Jia Y, Chen S. Correlation between hemoglobin glycosylation index and nerve conduction velocity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2021;14:4757–4765. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S334767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X-J, Wang X-F, Pan Z-C. Nerve conduction velocity is independently associated with bone mineral density in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1109322. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1109322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castelli G, Desai KM, Cantone RE. Peripheral neuropathy: evaluation and differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(12):732–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Won JC, Park TS. Recent advances in diagnostic strategies for diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Endocrinol Metab. 2016;31(2):230. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2016.31.2.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma S, Rayman G. Frontiers in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in diabetic sensorimotor neuropathy (DSPN). Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1165505. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1165505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kırça M, Oğuz N, Çetin A, Uzuner F, Yeşilkaya A. Uric acid stimulates proliferative pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells through the activation of p38 MAPK, p44/42 MAPK and PDGFRβ. J Recept Signal Transduction Res. 2017;37(2):167–173. doi: 10.1080/10799893.2016.1203941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhuang Y, Huang H, Hu X, Zhang J, Cai Q. Serum uric acid and diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a double-edged sword. Acta Neurol Belg. 2023;123(3):857–863. doi: 10.1007/s13760-022-01978-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu S, Chen Y, Hou X, et al. Serum uric acid levels and diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(2):1045–1051. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9075-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Vladmir C, Zhang Z, et al. Serum uric acid levels are related to diabetic peripheral neuropathy, especially for motor conduction velocity of tibial nerve in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. J Diabetes Res. 2023;2023:3060013. doi: 10.1155/2023/3060013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Tang Z, Tong L, Wang Y, Li L. Serum uric acid and risk of diabetic neuropathy: a genetic correlation and Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1277984. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1277984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piko P, Jenei T, Kosa Z, et al. Association of HDL subfraction profile with the progression of insulin resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(17):13563. doi: 10.3390/ijms241713563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aktas G, Kocak MZ, Bilgin S, Atak BM, Duman TT, Kurtkulagi O. Uric acid to HDL cholesterol ratio is a strong predictor of diabetic control in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aging Male. 2020;23(5):1098–1102. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2019.1678126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Y, Zhang H, Zheng H, et al. Association between serum uric acid/HDL-cholesterol ratio and chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study based on a health check-up population. BMJ Open. 2022;12(12):e066243. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xuan Y, Zhang W, Wang Y, et al. Association between uric acid to HDL cholesterol ratio and diabetic complications in men and postmenopausal women. DMSO. 2023;16:167–177. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S387726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ban J, Pan X, Yang L, et al. Correlation between fibrinogen/albumin and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023;16:2991–3005. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S427510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Javed S, Hayat T, Menon L, Alam U, Malik RA. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy in people with type 2 diabetes: too little too late. Diabet Med. 2020;37(4):573–579. doi: 10.1111/dme.14194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kocak MZ, Aktas G, Erkus E, Sincer I, Atak B, Duman T. Serum uric acid to HDL-cholesterol ratio is a strong predictor of metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2019;65(1):9–15. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.65.1.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin X, Xu L, Zhao D, Luo Z, Pan S. Correlation between serum uric acid and diabetic peripheral neuropathy in T2DM patients. J Neurol Sci. 2018;385:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gherghina ME, Peride I, Tiglis M, Neagu TP, Niculae A, Checherita IA. Uric acid and oxidative stress—relationship with cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal impairment. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(6):3188. doi: 10.3390/ijms23063188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y-P, Shao S-J, Guo H-D. Schwann cells apoptosis is induced by high glucose in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Life Sci. 2020;248:117459. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong Q, Liu J, Xu Y. Effects of uric acid on diabetes mellitus and its chronic complications. Int J Endocrinol. 2019;2019:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2019/9691345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L, Li B, Chen B, et al. Thymoquinone alleviates the experimental diabetic peripheral neuropathy by modulation of inflammation. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):31656. doi: 10.1038/srep31656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu W, Xu Y, Shao X, et al. Uric acid produces an inflammatory response through activation of NF-κB in the hypothalamus: implications for the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):12144. doi: 10.1038/srep12144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khosla U M, Zharikov S, Finch J L, Nakagawa T, Roncal C, Mu W, Krotova K, Block E R, Prabhakar S and Johnson R J. (2005). Hyperuricemia induces endothelial dysfunction. Kidney International, 67(5), 1739–1742. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00273.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi Y, Yoon Y, Lee K, et al. Uric acid induces endothelial dysfunction by vascular insulin resistance associated with the impairment of nitric oxide synthesis. FASEB j. 2014;28(7):3197–3204. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-247148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kjeldsen EW, Nordestgaard LT, Frikke-Schmidt R. HDL cholesterol and non-cardiovascular disease: a narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4547. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Endo Y, Fujita M, Ikewaki K. HDL functions-current status and future perspectives. Biomolecules. 2023;13(1):105. doi: 10.3390/biom13010105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith AG, Singleton JR. Obesity and hyperlipidemia are risk factors for early diabetic neuropathy. J diabet complicat. 2013;27(5):436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hur J, Dauch JR, Hinder LM, et al. The metabolic syndrome and microvascular complications in a murine model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(9):3294–3304. doi: 10.2337/db15-0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo L, Zhou WH, Cai JJ, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies downregulation of the neurotrophin-MAPK signaling pathway in female diabetic peripheral neuropathy patients. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2017/8103904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kandimalla R, Dash S, Kalita S, et al. Bioactive Fraction Of Annona Reticulata Bark (or) Ziziphus jujuba Root Bark along with insulin attenuates painful diabetic neuropathy through inhibiting NF-κB inflammatory cascade. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pai YW, Lin CH, Lee IT, Chang MH. Variability of fasting plasma glucose and the risk of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metabolism. 2018;44(2):129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]