Keywords: flow-mediated dilation, glycocalyx, type 2 diabetes, zanamivir

Abstract

Neuraminidases cleave sialic acids from glycocalyx structures and plasma neuraminidase activity is elevated in type 2 diabetes (T2D). Therefore, we hypothesize circulating neuraminidase degrades the endothelial glycocalyx and diminishes flow-mediated dilation (FMD), whereas its inhibition restores shear mechanosensation and endothelial function in T2D settings. We found that compared with controls, subjects with T2D have higher plasma neuraminidase activity, reduced plasma nitrite concentrations, and diminished FMD. Ex vivo and in vivo neuraminidase exposure diminished FMD and reduced endothelial glycocalyx presence in mouse arteries. In cultured endothelial cells, neuraminidase reduced glycocalyx coverage. Inhalation of the neuraminidase inhibitor, zanamivir, reduced plasma neuraminidase activity, enhanced endothelial glycocalyx length, and improved FMD in diabetic mice. In humans, a single-arm trial (NCT04867707) of zanamivir inhalation did not reduce plasma neuraminidase activity, improved glycocalyx length, or enhanced FMD. Although zanamivir plasma concentrations in mice reached 225.8 ± 22.0 ng/mL, in humans were only 40.0 ± 7.2 ng/mL. These results highlight the potential of neuraminidase inhibition for ameliorating endothelial dysfunction in T2D and suggest the current Food and Drug Administration-approved inhaled dosage of zanamivir is insufficient to achieve desired outcomes in humans.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This work identifies neuraminidase as a key mediator of endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes that may serve as a biomarker for impaired endothelial function and predictive of development and progression of cardiovascular pathologies associated with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Data show that intervention with the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir at effective plasma concentrations may represent a novel pharmacological strategy for restoring the glycocalyx and ameliorating endothelial dysfunction.

INTRODUCTION

Endothelial dysfunction is consistently manifested in type 2 diabetes (T2D) and represents a primary pathological feature in the development and progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD), the number one cause of death in diabetics (1, 2). Indeed, CVD complications account for over 70% of T2D-associated mortality (3, 4). Consequently, many functional and structural features of the vascular endothelium have been targeted in research aimed at deciphering the association between T2D and CVD (5). Under physiological conditions, a major function of the vascular endothelium is to produce vasodilators and vasoconstrictors that control vascular diameter and maintain vascular wall homeostasis. However, under pathological conditions, such as those encountered in T2D, there is a reduced capacity of the endothelium to induce vasodilation. This endothelial dysfunction is strongly linked to insulin resistance (6), as well as to an increased risk for life-threatening cardiovascular events (7). Thus, there is a considerable need to identify therapies that improve endothelial function in T2D.

A major physiological stimulus that causes the endothelium to induce vasodilation is blood flow-induced shear stress. The mechanism responsible for this flow-mediated dilation (FMD) involves a process in which the endothelial glycocalyx participates in the mechanosensation and mechanotransduction of shear that leads to the production of the vasodilator, nitric oxide (NO). The endothelial glycocalyx is a thin layer of glycoproteins and proteoglycans interwoven with one another that form a luminal mesh separating the endothelial cell membrane from the flowing blood (8–10). One consequence of the constant shear caused by blood flow on the glycocalyx is the continuous shedding of its components, which are replaced via the biosynthesis of new glycans (11). These dynamic degradation and restoration cycles are compromised under conditions of inflammation (12), oxidative stress (13), and hyperglycemia (14), which are common features of T2D. In addition, cleavage of glycocalyx constituents by enzymes such as neuraminidase, hyaluronidase, and heparinase is associated with diminished FMD (15, 16), a clinically relevant indicator of endothelial dysfunction in T2D (17–19).

Previously, we demonstrated that plasma neuraminidase activity is increased in a mouse model of Western diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance (20). This is consistent with reports indicating that circulating neuraminidase activity is elevated in patients with T2D (21–24). The primary action of neuraminidase enzymes is to cleave sialic acid from glycoproteins and glycolipids, including those contained within the endothelial glycocalyx. Accordingly, it has been shown that serum concentrations of sialic acid are elevated in patients with diabetes (21, 22, 24–32). Moreover, in agreement with the notion that the glycocalyx functions as a shear stress mechanosensor and mechanotransducer to induce vasodilation via activation of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), reports indicate that a negative correlation exists between concentrations of serum sialic acid and NO in patients with diabetes (33, 34). These data, coupled with observations indicating that the volume of the endothelial glycocalyx is reduced in diabetes (14, 35), led us to hypothesize that circulating neuraminidase is implicated in the degradation of the glycocalyx and diminished FMD associated with T2D, and that inhibition of neuraminidase activity would restore shear mechanosensation and endothelial function in the setting of T2D.

METHODS

Cross-Sectional and Interventional Human Studies

All experimental procedures involving human subjects were approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before participation in the studies. Each subject represented an experimental unit for all outcomes assessed.

In the cross-sectional study (IRB No. 2008181), 20 subjects with a self-reported clinical diagnosis of noninsulin-dependent T2D, along with 20 age- and sex-matched healthy control subjects were included. Subject characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, anthropometrics, hemodynamic measurements, blood profile parameters, as well as femoral artery FMD methods have been previously published (36).

In the interventional study (IRB No. 2038203), registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04867707), a separate cohort of men (n = 8) and women (n = 6) with a clinical diagnosis of T2D and between the ages of 45 and 60 yr were studied. Exclusion criteria included history of recent (<12 mo) cardiovascular events, uncontrolled hypertension (≥180 mmHg systolic or 100 mmHg diastolic), autoimmune diseases, renal or hepatic diseases, active cancer, use of immunosuppressant therapy, excessive alcohol consumption (>14 drinks/wk for men; >7 drinks/wk for women), current tobacco use, or pregnancy (confirmed by negative pregnancy test on the morning of the first visit in the study). The characteristics of the subjects enrolled in the interventional study are provided in Table 1. Brachial artery FMD and perfused boundary region (PBR) of the sublingual microcirculation were assessed before and after patients underwent a 5-day zanamivir (Relenza, GlaxoSmithKline) treatment regimen during which zanamivir (10 mg) was inhaled every 12 h, according to the recommended dosage on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) label (37). Plasma samples were also collected before and after the intervention. All outcomes were assessed at the University of Missouri Clinical Research Center after an overnight fast.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Sex (females/males), n/n | 6/8 |

| Age, yr | 53.0 ± 1.3 |

| Weight, kg | 98.5 ± 4.8 |

| Height, cm | 174.35 ± 2.18 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32.20 ± 1.16 |

| Medications, n | |

| Hypoglycemic medications | |

| Biguanides | 11 |

| Sulfonylureas | 5 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 6 |

| GLP-1 agonists | 7 |

| Insulin | 7 |

| Cardiovascular medications | |

| ACE inhibitors | 3 |

| ARBs | 5 |

| Diuretics | 8 |

| Beta blockers | 6 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 3 |

| Statins | 9 |

| Thyroid medications | 4 |

| Aspirin | 2 |

| Anticonvulsants | 4 |

| Muscle relaxant | 1 |

| NSAID | 1 |

| Dopamine agonist | 1 |

| Antidepressant | 1 |

Values are means ± SE. BMI, body mass index; SGLT2, sodium glucose transporter 2; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Human Plasma Analyses

To measure neuraminidase activity in human plasma, 100 µL of plasma was added to 100 µL of buffer containing 150 µM sodium acetate pH 4.5, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 1.0 mM 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid sodium salt hydrate (M8639, Sigma), for 90 min at 37°C. Fluorescence end point measurements obtained with wavelengths of 377 nm for excitation and 450 nm for emission detection were collected using a BioTek Synergy H1 Plate Reader.

Plasma nitrite was used as a surrogate of NO and assessed using an ozone-based reductive chemiluminescence NO analyzer (CLD88, Eco Physics) according to the manufacturer guidelines and as previously described (38). Plasma samples (150 µL) were injected in duplicate into a purge vessel containing an acidified iodide solution (50 mg of potassium iodide dissolved in 1 mL of filtered ddH2O + 4 mL of glacial acetic acid), which was then purged with pure nitrogen in-line with the CLD88 gas-phase NO analyzer. Using eDAQ ChartTM v5.5.27 software, the chemiluminescence signal was acquired and NO was quantified using the flow injection analysis (FIA) software extension (ADInstruments, Australia). The area under the curve for each sample peak was calculated with the FIA software, which was then converted to a concentration using a calibrated standard curve of known sodium nitrite standards.

The Proteomics Center at the University of Missouri was used for mass spectrometry services to measure zanamivir concentrations in plasma. Samples were extracted and analyzed according to the “low range” protocol by Lindegardh et al. (39) with the following modifications: 1) Biotage Isoelute SCX SPE (50 mg × 1 mL; Part No. 530-005-A; Batch No. 530-0-04; Biotage LLC, Charlotte, NC) was conducted manually using a Supelco vacuum manifold; 2) cone and collision energies for published transitions for zanamivir (Sigma SKU No. SML0492-50MG; Lot No. 0000190459); and 13C, 15N zanamivir (Cayman Chemical Cat. No. 30733; Batch No. 0662383-1) were optimized on a Waters Xevo TQS mass spectrometer; 3) samples and standards (10-µL injections in triplicate) were separated on a ZIC-HILIC column (SeQuant 5 cm × 2.1 mm × 5 µm); and 4) zanamivir peaks were quantified using Targetlynx (Waters Corp) with default parameters for peak peaking and integration.

Brachial Artery FMD

The assessment of FMD in the brachial artery was performed using two-dimensional/Doppler ultrasound (GE Logiq P5), as we previously described and according to published guidelines (40, 41). Briefly, an 11-MHz linear array transducer was placed over the brachial artery and secured with a clamp. A rapid inflating cuff (Hokanson) was placed on the forearm ∼5 cm distal to the antecubital fossa. Simultaneous diameter and velocity signals were obtained in duplex mode at a pulsed frequency of 5 MHz and corrected with an insonation angle of 60°. Sample volume was adjusted to encompass the entire lumen of the vessel without extending beyond the walls, and the cursor was set at midvessel. Two minutes of ultrasound imaging were recorded using a real-time capture software (Elgato Video Capture, Elgato, CA), and the cuff was then inflated to a pressure of 250 mmHg for 5 min. Three minutes of ultrasound imaging were collected following cuff deflation. Recordings of vascular variables were analyzed off-line using specialized edge-detection software (Cardiovascular Suites 4, Quipu srl, Pisa, Italy). FMD percent change was calculated as:

where Dpeak and Dbl are peak and baseline diameter reported in mm. Shear rate was estimated as:

where γ is shear rate reported in s−1, υ is mean blood velocity in cm/s, and is the diameter in cm.

In Vivo Glycocalyx Thickness

Integrity of the endothelial glycocalyx was assessed via bedside intravital microscopy using a side-stream dark field camera (CapiScope HVCS, KK Technology, Honiton, UK) to visualize the sublingual microvasculature, as previously published (42). This method is currently the gold standard for in vivo noninvasive assessment of glycocalyx integrity (43). Briefly, side-stream dark field video microscopy allows for the detection of hemoglobin found in moving red blood cells within the sublingual microcirculation via green light emitting stroboscopic diodes (540 nm). Image acquisition and analysis were automatically performed using a GlycoCheck system (MicroVascular Health Solutions, Alpine, UT) after predefined criteria (motion, intensity, and focus) were established. Following analysis, thickness of the endothelial glycocalyx in microvessels ranging from 5 to 25 μm in internal diameter was reported as PBR. PBR represents the distance that separates flowing red blood cells from the physical width of the negatively charged glycan structures (glycosaminoglycans and sialic acid) that comprise the glycocalyx. An increased PBR indicates deeper penetration of red blood cells into the glycocalyx, denoting its degradation and thinning (44). This technique has been used and validated in previous publications (44–48).

Cell Culture Studies

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, CC-2519, Lonza) were cultured in complete VascuLife EnGS medium (LL-0002, Lifeline Cell Technologies), EGM medium (CC-3124, Lonza). Cells were propagated in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 and used between passages 5 and 6. HUVECs (5 × 104 cells/well) were seeded onto 15-well μ-slides (81506, Ibidi) and cultured for 24 h at 37°C under 5% CO2. Cells were then treated with 100 mU/mL neuraminidase (N2876, Sigma) or vehicle control for 48 h. Following treatments, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (15710, Electron Microscopy Sciences) in preparation for immunofluorescence staining and imaging. To assess the effects of neuraminidase on the shedding of syndecan-1 from the cell surface, HUVECs were treated with 125 mU/mL neuraminidase or vehicle control for 1 h followed by exposure to laminar shear stress (15 dyn/cm2) for 1 h in an Ibidi pump system (10902, Ibidi) and prepared for immunofluorescence imaging. Treatments were randomly allocated to cell wells or chambers, and each well or chamber was considered an experimental unit.

Cell Immunofluorescence Imaging

To assess endothelial coverage by glycocalyx structures, fixed cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated for 30 min with 3 µg/mL of Alexa-488-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA-Alexa-488, W11261, Molecular Probes) or 20 µg/mL of Cy3-conjugated Maackia amunrensis lectin 1 and 2 (MAA/MAL I + II, 21511110-1, bioWORLD). For assessing the presence of specific proteins, fixed cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and blocked for 1 h in antibody blocking buffer, containing 10% goat serum + 0.05% Triton X-100 + 1% bovine serum albumin, at room temperature. Hyaluronan was detected with a biotinylated hyaluronan binding protein (HABP, 385911, Millipore Sigma) at 1:200 dilution while syndecan-1 was detected with a primary monoclonal antibody that binds its ectodomain (SDC1, ab34164, Abcam), at 1:100 dilution. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C in a buffer (2% goat serum + 0.05% Triton X-100 + 1% BSA) containing HABP or SDC1 primary antibody. Goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 (A11001, Molecular probes) secondary antibody was applied for 1 h at room temperature to detect the primary antibody, while 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to stain cell nuclei. A blinded investigator captured images in triplicate using a Leica SPE confocal microscope with a ×20/0.60 numerical aperture oil objective and excitation lasers emitting light at 408 nm and 488 nm. Imaris software v9.0 was used to quantify the mean fluorescence intensity generated by the bound lectins, bound HABP, or SDC1 bound antibody. The number of cells (nuclei) in the images was used to normalize the fluorescence signal.

Animal Studies

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Missouri and performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. C57BL/6J and db/db male mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were fed with standard chow (5053-PicoLab Rodent Diet 20, LabDiet) and had ad libitum access to water. Mice were housed two per cage, under 12-h:12-h dark/light cycles. Mouse health was monitored daily by animal care takers. All animal procedures were noninvasive and none of the mice in the study experienced an adverse event. Mice were euthanized while under surgical plane anesthesia with 2% isoflurane (AKORN Animal Health) via inhalation with room air (250 mL/min) followed by pneumothorax and exsanguination. Blood was collected for plasma analyses and arteries excised for functional and mechanical testing. Each mouse represented an experimental unit for all outcomes assessed.

Neuraminidase Infusion

To examine the impact of exogenous neuraminidase infusion on endothelial glycocalyx integrity and FMD responses, 16-wk-old C57BL/6J male mice were injected (intravenously) via the tail vein with 400 mU of neuraminidase (Cat. No. 9001-67-6 Sigma) every 24 h for 48 h (2 injections for a total dose of 800 mU). Neuraminidase was diluted in a total volume of 100 µL of sterile saline for each bolus injection. An additional group of mice was injected with vehicle and served as control. Animals were euthanized 24 h after the last injection for tissue collection, which included aortae for atomic force microscope (AFM) assessment of glycocalyx length and mesenteric arteries for assessment of FMD using pressure myography.

Zanamivir Treatment

To determine the plasma bioavailability of zanamivir (Relenza, GlaxoSmithKline) in mice after its aerosolization and inhaled administration, 11-wk-old C57BL/6J male mice were given two inhaled doses of zanamivir (5 mg) 12 h apart. Zanamivir was aerosolized using a rubber bulb attached to a hose and placed over the snout of the animal to facilitate inhalation of the powder. One hour after the second dose, mice were euthanized and plasma samples were analyzed for their content of zanamivir at the Gehrke Proteomics Center in the University of Missouri. To determine the effects of neuraminidase inhibition on the endothelial glycocalyx and vascular function in diabetic mice, 11-wk-old db/db male mice were randomly assigned to be administered 5 mg of zanamivir or the same amount of lactose as vehicle control via inhalation every 12 h for 5 days. This dosage corresponds to ∼100 mg/kg in a db/db mouse model and has been demonstrated to reduce plasma neuraminidase activity in C57BL/6J mice by >50% at 6-h postdelivery (49). The powdered drug or lactose vehicle was aerosolized as indicated earlier to facilitate inhalation of the treatments. All subsequent in vivo and ex vivo assessments were performed by investigators blinded to the treatment status of the mice.

Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity

To assess arterial stiffness in vivo, measurements of aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV) were obtained using Doppler ultrasound (Indus Mouse Doppler System, Webster, TX), as we have previously described (50, 51). Briefly, on the day of euthanasia, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (1.75% in 100% oxygen stream) and placed in a supine position on a heating board with their limbs secured onto electrocardiogram (ECG) electrodes. PWV was determined based on the transit time method, calculated as the difference in arrival times of pulse waves at the descending aorta proximal to the aortic arch followed by measurement at the descending aorta proximal to the iliac bifurcation. Each pulse wave arrival time was measured as the time from the peak of the ECG-R wave to the leading foot of the pulse wave at which time velocity begins to rise in the start of systole. The distance between the thoracic and abdominal aorta was measured with a ruler to the nearest 0.1 cm and then divided by transit time. Data are expressed in meters per second. The investigator analyzing pulse waveforms was blinded to the treatment interventions that the mice received.

Mouse Plasma Neuraminidase Activity

A blood sample from each mouse was obtained and collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-coated tubes (Cardinal Health) at the time of euthanasia, which took place ∼12 h after the last zanamivir dose. Neuraminidase activity was determined in plasma using an Amplex Red Neuraminidase Assay Kit (A22178, Molecular Probes). Duplicate plasma samples (5 μL each) were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in Amplex Red reaction mixture and end-point fluorescence was determined in a Biotek Synergy HT microplate reader using excitation at 530 nm and detection at 590 nm. End-point fluorescence was averaged for each sample, and mean values were determined for mice in the vehicle and zanamivir treatment cohorts. Though the pharmacokinetics of the inhibitory effect of zanamivir in mice are not fully determined, published data indicate that the plasma neuraminidase inhibitory action of the drug peaks at ∼6-h postdosage and drops by roughly 50% at 12 h (49). Animals were euthanized ∼12-h postadministration of the final zanamivir dosage, thus the assessment of plasma neuraminidase activity in this study corresponds to lower levels of inhibitory activity relative to the maximum inhibitory peak over the duration of zanamivir treatment.

Ex Vivo Arterial Vasomotor and Mechanical Responses

Following euthanasia, femoral arteries were collected for determination of vascular functional and mechanical responses via pressure myography, as we have previously described (20, 51). Isolated arteries were cannulated and mounted onto pressure myographs set at an intraluminal pressure of 70 mmHg and exposed to a series of sequential 10−5 M phenylephrine preconstrictions followed by increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (10−9 to 10−5 M), insulin (10−9 to 10−5 M), or sodium nitroprusside (10−8 to 10−4 M) in half log increments every 2 min to assess endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilatory responses. Following vasodilatory assessment, the cannulated vessels were exposed to calcium-free buffer containing 2 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid and 0.1 mM adenosine to achieve passive conditions. Intraluminal pressures were then changed from 5 to 120 mmHg at intervals of 2 min and internal diameter as well as wall thickness was recorded to assess vascular remodeling and stiffness, as we have previously described (20, 51). For a detailed description of the equations and parameters used to assess mechanical and biophysical properties of arteries see the study by Wenceslau et al. (52). Each artery came from one mouse and were exposed or not (vehicle control) to specific treatments followed by outcome assessments. Outcomes were also measured before and after treatment in femoral arteries for paired comparisons.

Ex Vivo FMD

To assess FMD in isolated vessels, cannulated, pressurized, and preconstricted femoral or mesenteric arteries were exposed to increasing rates of luminal flow while maintaining mean intravascular pressure at 70 mmHg via pressure myography, as previously described (53). Luminal diameters were obtained at each flow rate and used to calculate endothelial shear stress according to the following formula:

where τ is shear stress reported in dyn/cm2, μ is perfusate viscosity in dyn·s/cm2, Q is flow rate in cm3/s and Di is the internal diameter of the vessel in cm. Values obtained with this formula were used to construct shear stress versus FMD curves for the vehicle, neuraminidase, and zanamivir-treated cohorts. Femoral FMD was also obtained in vessels isolated from contemporaneous db/+ mice in conjunction with the zanamivir treated db/db mice.

To determine the acute effect of neuraminidase exposure on FMD, we exposed femoral and mesenteric resistance arteries from untreated control C57BL/6J male mice intraluminally to 100 mU/mL of neuraminidase (N2876, Sigma) or vehicle control for 1 h and then to increasing rates of luminal flow. In an additional experiment, FMD was assessed in femoral arteries before and after the 1-h exposure to the enzyme.

Ex Vivo Endothelial Stiffness

The elastic modulus (stiffness) of the aortic endothelial surface was measured in thoracic aortic explants from db/db mice using an atomic force microscope (AFM) MFP-3D AFM 89 (Asylum Research, Goleta, CA), as previously described (51, 54). Briefly, a segment of the thoracic aorta was opened longitudinally and glued onto a glass slide using Cell-Tak adhesive. Repeated cycles of nanoindentation and retraction were applied to the endothelial surface of samples maintained at room temperature (∼25°C). The generated indentation curves were analyzed with a custom MATLAB script to calculate force curves and obtain the elastic modulus of the endothelial surface using the Hertz model:

where F is force reported in nN, α is the opening angle for the tip in radians, ν is the Poisson’s ratio of the sample (for soft biological sample is generally set to 0.5 in arbitrary units), δ is the indentation depth into the sample in nm, and E is the Young’s modulus in kPa.

Ex Vivo Glycocalyx Integrity

To measure the endothelial glycocalyx length in aortic explants, tissues were prepared as earlier, and AFM nanoindentation experiments performed with an MFP-3D AFM 89 (Asylum Research Inc. Goleta, CA) using a 5.0-µm spherical probe attached to the cantilever (NovaScan), which had a spring constant of 0.02 N/m. The code generated to perform the curve analysis for glycocalyx length was implemented following the recommendations described by Targosz-Korecka et al. (55). For each aortic explant of 2 mm2, a minimum of 50 nanoindentation curves were obtained at seven random locations within the sample. The nanoindentation curves were recorded for a maximal loading force of 1.0 nN at a speed of 0.25 µm/s. Curves that did not follow the model (mathematically determined, i.e., unbiased) were discarded.

To assess glycocalyx coverage and integrity on the endothelial surface of isolated femoral arteries, excised vessels were cannulated, and blood flushed out from their lumen using cold (∼4°C) physiological saline solution. The left and right femoral arteries from the same animal were warmed to 37°C, pressurized to 70 mmHg, and exposed intraluminally at a flow rate of 1 mL/h to 3 µg/mL of Alexa-555-conjugated WGA (W32464, Molecular Probes) and 2 µg/mL of Alexa Fluor 633 Hydrazide (A30634, Molecular Probes) for 30 min. WGA was used to identify the glycocalyx and Alexa Fluor 633 Hydrazide to identify elastic lamina (56, 57). After washing for an additional 30 min in physiological saline at a flow rate of 1 mL/h, arteries were immediately imaged using a Leica Stellaris 8 confocal microscope with a ×25/0.95 numerical aperture water objective to assess the level of WGA binding to the endothelial glycocalyx. The cannulated arteries were then incubated intraluminally at a flow rate of 1 mL/h with vehicle control or 100 mU/mL of neuraminidase (N2876, Sigma) for 1 h. This was followed by intraluminal washing with physiological saline and acquisition of a confocal image as before. This procedure allowed for comparisons between images taken before (pretreatment) and after (posttreatment) exposure to vehicle or neuraminidase. Fluorescent images were analyzed with a Python script that allowed for unbiased measurements of WGA volume. The script isolated the endothelial-specific WGA signal using the internal elastic lamina as a mask and then quantified the WGA volume in the luminal portion of the vessel as the number of WGA positive voxels. The difference in pre- to posttreatment WGA volumes was compared between conditions.

Statistical Analyses

For the clinical trial, based on variability and treatment effect from a previously published study using brachial artery FMD (58), we determined that 12 subjects (experimental units) would be sufficient to detect significant differences in FMD. We enrolled 14 subjects to account for any potential dropouts. For the animal studies, variability from our previously published assessments of FMD (59) in isolated arteries indicated we needed five mice (experimental units) per group to detect a difference of 29.5% between groups. Cell culture experiments were performed using an initial number of five experimental units followed by power analyses to determine if additional experimental units were needed based on the initially observed numerical difference. All power analyses used an α of 0.05 and 80% power. All data are presented as means ± SE and were tested for normality of distribution before statistical analyses were performed. Statistical analyses consisted of Student’s t tests, Mann–Whitney U test, or two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test when appropriate and as indicated in the figure legends. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, v.9. A P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Subjects with T2D Have Increased Plasma Neuraminidase Activity That Coincides with Decreased Plasma Nitrite and Reduced FMD

It has been previously shown that neuraminidase activity is elevated in patients with T2D and that this coincides with increased circulating concentrations of its substrate, sialic acid, suggesting glycocalyx degradation (21–24). To determine if increased plasma neuraminidase activity in patients with T2D also coincides with endothelial dysfunction, we measured neuraminidase activity and nitrite (a surrogate of NO) in existing plasma samples from a cohort of healthy subjects and subjects with T2D from which we previously reported mean femoral artery FMD data (36). The characteristics of the subjects, including their medication use, anthropometrics, fasting blood glucose, and insulin concentrations were also previously published (36). Further analyses of plasma samples from those subjects revealed that, compared with healthy controls, subjects with T2D had greater plasma levels of neuraminidase activity (Fig. 1A) and decreased concentrations of nitrite (Fig. 1B). Notably, these plasma changes in subjects with T2D coincided with impaired FMD, denoting endothelial dysfunction (Fig. 1C) (36). Further analyses indicated that plasma neuraminidase activity was negatively correlated with plasma nitrite and FMD and that, as expected, FMD was positively correlated with plasma nitrite (Fig. 1, D–F). These results indicate that subjects with T2D have increased plasma levels of the glycocalyx-degrading enzyme, neuraminidase, in association with endothelial dysfunction characterized by reduced markers of NO bioavailability and impaired FMD.

Figure 1.

Human subjects with type 2 diabetes (T2D) have increased plasma neuraminidase activity and decreased endothelial function. A: plasma neuraminidase activity expressed as fold difference from healthy controls (open circles, n = 20) and subjects with T2D (red circles, n = 18, plasma samples from two subjects were completely used in previous assays). B: plasma nitrite concentration in healthy controls (open circles, n = 12, plasma samples from eight subjects had been completely used in previous assays) and subjects with T2D (red circles, n = 15, plasma samples from five subjects had been completely used in previous assays). C: femoral artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) expressed as percent change in arterial diameter in healthy controls (open circles, n = 20) and subjects with T2D (red circles, n = 15, borders of the arterial wall for 5 subjects were not sufficiently resolved for accurate diameter measurements). D–F: Pearson correlations between plasma neuraminidase activity with FMD (D), plasma neuraminidase activity with plasma nitrite (E), and plasma nitrite with FMD (F). Data are expressed as means ± SE or Pearson’s coefficient (r). *P ≤ 0.05, T2D vs. healthy controls as determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (A and C) and Mann–Whitney U test (B).

Neuraminidase Impairs FMD in Isolated Mouse Mesenteric and Femoral Arteries

To determine the direct effect of neuraminidase on vascular endothelial function, we exposed the lumen of resistance and muscular feed arteries isolated from C57BL/6J male mice to neuraminidase or vehicle control and subsequently assessed FMD. Mesenteric resistance arteries treated intraluminally for 1 h with neuraminidase displayed significantly reduced FMD responses compared with vehicle-treated vessels at all intraluminal flow rates and shear stress levels above zero (Fig. 2, A and B). The same vessels were also assessed for receptor-mediated vasodilation with acetylcholine and endothelial-independent vasodilation with sodium nitroprusside. In contrast to the FMD results, there were no significant differences in vasodilatory responses to acetylcholine or sodium nitroprusside between vehicle versus neuraminidase-treated vessels (Fig. 2, C and D).

Figure 2.

Exposure to exogenous neuraminidase blunts arterial flow-mediated dilation (FMD). A: cannulated and pressurized small mesenteric arteries isolated from C57BL/6J male mice were exposed intraluminally to either vehicle (control, n = 5, 1 isolated vessel did not respond to preconstriction with phenylephrine) or neuraminidase (Neu, n = 6) for 1 h and subsequently preconstricted with phenylephrine and subjected to increasing intraluminal flow rates to augment wall shear stress and induce FMD. FMD at each intraluminal flow rate (mL/h) is expressed as percent dilation from the maximal phenylephrine preconstriction. B: same FMD data as in A, plotted against the shear stress achieved at each intraluminal flow rate used. C and D: vasodilatory responses of the same mesenteric arteries, preconstricted with phenylephrine and exposed to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (C) or sodium nitroprusside (D). E: cannulated and pressurized femoral arteries isolated from C57BL/6J male mice (n = 4) were subjected to increasing levels of intraluminal flow before (pretreatment) and after (posttreatment) a 1-h exposure to neuraminidase (Neu). Femoral FMD at each intraluminal flow rate (mL/h) is expressed as percent dilation from the maximal phenylephrine preconstriction in response to increasing levels of flow rate. F: same FMD data as in E, plotted against the shear stress achieved at each intraluminal flow rate used. G: representative images taken before (pretreatment) and after (posttreatment) a 1-h intraluminal exposure to neuraminidase in which the glycocalyx was stained with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, green at top, and white at bottom), and the internal elastic lamina was stained with Alexa Fluor 633 hydrazide (red); scale bar = 50 µm (n = 5). Image contrast was adjusted equally for visualization purposes, and analyses were performed using raw data. H: quantification of change in WGA content is expressed as fold difference from control in the same femoral arteries as in G. I: C57BL/6J male mice were injected twice over 48 h with either a bolus of 16.6 U/mL of Clostridium perfringens Neu (n = 6) or vehicle control (n = 6) and euthanized 24 h after the second injection. Their isolated mesenteric arteries were cannulated, pressurized, and subsequently preconstricted with phenylephrine and exposed to increasing intraluminal flow rates to augment wall shear stress and induce FMD. FMD at each intraluminal flow rate (mL/h) is expressed as percent dilation from the maximal phenylephrine preconstriction. One isolated vessel from each group did not respond to preconstriction with phenylephrine. J: same FMD data as in I, plotted against the shear stress achieved at each intraluminal flow rate used. K: schematic representation of atomic force microscopy (AFM) generated force curves used to measure glycocalyx length of aortic en face samples from the same mice as in I. L: endothelial glycocalyx length as assessed by AFM in aortic explants isolated from the same mice as in I. Data are expressed as means ± SE. *P ≤ 0.05, Neu vs. vehicle or control as determined by two-way ANOVA (repeated measurements) main effect of treatment (A, E, and I) or by two-tailed, paired (H) or unpaired (L) Student’s t test.

We also assessed FMD in a paired fashion, before and after exposure to neuraminidase for 1 h in femoral arteries. Similar to the results observed in mesenteric resistance arteries, treatment of femoral arteries with neuraminidase significantly dampened FMD responses (Fig. 2, E and F). We used additional paired segments of femoral arteries to determine the effect of intraluminal neuraminidase exposure on coverage of the endothelial surface with glycocalyx structures. This was achieved by staining the endothelial glycocalyx with Alexa-555 WGA. Results show that treatment with neuraminidase reduced glycocalyx coverage of the endothelium by 109% compared with segments of femoral arteries exposed to vehicle control (Fig. 2, G and H).

To determine if similar effects would be observed in vivo, we infused C57BL/6J male mice with two intravenous boluses of neuraminidase (400 mU each), or vehicle control, 24 h apart and euthanized the mice 24 h after infusion of the second bolus. We excised segments of the thoracic aortae to measure the endothelial glycocalyx using AFM on en face preparations of the artery. Mesenteric arteries were also excised to assess FMD responses ex vivo. Data showed that in vivo intravenous infusion of neuraminidase degraded endothelial glycocalyx structures and impaired FMD (Fig. 2, I–L). All these results indicate that ex vivo and in vivo intraluminal neuraminidase activity has deleterious effects on the endothelial glycocalyx in both conduit and small arteries, and that it reduces the capacity of the vascular endothelium to induce vasodilation in response to flow-induced shear stress.

Neuraminidase Facilitates Shedding of Glycocalyx Components in Cultured Endothelial Cells

To interrogate the role of neuraminidase on the degradation of specific endothelial glycocalyx components, we treated cultured endothelial cells with neuraminidase and assessed their surface for glycocalyx structures (using WGA), sialic acid (using MAA/MAL I + II), hyaluronan (using HAPB), and syndecan-1 (using SDC1) content. We chose to measure those components of the glycocalyx because sialic acid is the specific substrate of neuraminidase and because both hyaluronan and syndecan-1 have been implicated in mechanosensation of shear stress in endothelial cells (10, 60–62). Neuraminidase-treated cells had significantly less glycocalyx structures with sialic acid coverage of the cell surface as assessed with binding of WGA (a fluorophore-labeled lectin that binds sialic acid-containing glycoconjugates and oligosaccharides) (63) or MAA/MAL I + II per cell compared with controls (Fig. 3, A–D). Similarly, there was a significant reduction in the content of hyaluronan and syndecan-1 ectodomain on cells treated with neuraminidase compared with controls (Fig. 3, E–H). These data demonstrate that neuraminidase activity diminishes diverse glycocalyx structures on endothelial cells that have been previously associated with mechanosensation of shear stress.

Figure 3.

Exposure of cultured endothelial cells to neuraminidase (Neu) reduces presence of cell surface glycocalyx structures. A: representative fluorescence images of glycocalyx stained with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, green) and nuclei stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue) in human endothelial cells; scale bar = 50 µm. Cells were treated for 1 h with either vehicle (control, n = 5), or neuraminidase (Neu, n = 5). B: quantification of WGA fluorescence intensities normalized by the number of cells and expressed as fold difference from control. C: representative fluorescence images of glycocalyx sialic acid stained with Maackia amunrensis lectin 1 and 2 (MAA/MAL I + II, green) and nuclei stained with DAPI (blue); scale bar = 50 µm. Cells were treated for 1 h with either vehicle (control, n = 5), or neuraminidase (Neu, n = 5). D: quantification of MAA/MAL I + II fluorescence intensities normalized by the number of cells and expressed as fold difference from control. E: representative fluorescence images of glycocalyx hyaluronan stained with hyaluronan acid binding protein (HABP, green) and nuclei stained with DAPI (blue); scale bar = 50 µm. Cells were treated for 1 h with either vehicle (control, n = 5), or neuraminidase (Neu, n = 5). F: quantification of HABP fluorescence intensities normalized by the number of cells and expressed as fold difference from control. G: representative images of immunofluorescence staining of syndecan-1 (SDC1, green) and nuclei staining with DAPI (blue), scale bar = 50 µm. Cells were treated for 1 h with either vehicle (control, n = 12) or neuraminidase (Neu, n = 12) and subsequently exposed to 15 dyn/cm2 shear stress for 1 h. H: quantification of SDC1 fluorescence intensities normalized by the number of cells and expressed as fold difference from Control. Data are expressed as means ± SE. *P ≤ 0.05, neuraminidase vs. control as determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (B, D, and F) or Mann–Whitney U test (H).

Neuraminidase Inhibition with Zanamivir Improves Endothelial Function in db/db Mice

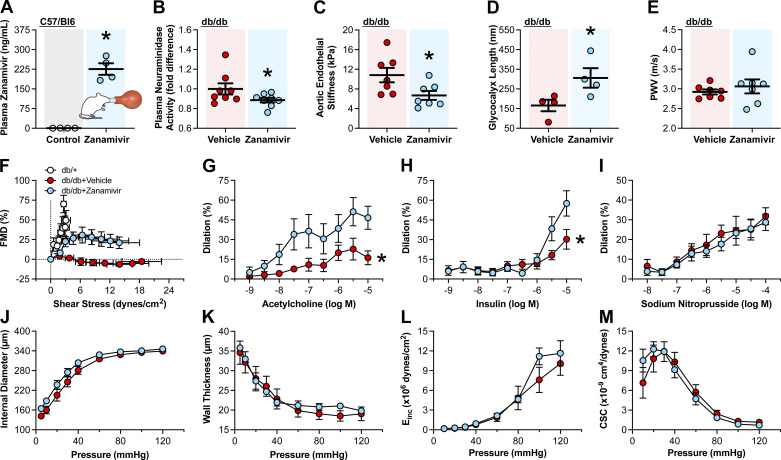

As we chose inhaled zanamivir to assess the therapeutic value of neuraminidase inhibition to improve endothelial function, we first determined the capacity of zanamivir inhalation to increase the concentration of the inhibitor in the plasma of 11-wk-old C57BL/6J male mice. We found that two doses (5 mg/dose) of zanamivir inhalation significantly increased the levels of the inhibitor in plasma compared with untreated controls (Fig. 4A). We subsequently treated 11-wk-old db/db mice with either vehicle control or zanamivir for 5 days followed by euthanasia. Treatment with zanamivir diminished plasma neuraminidase activity compared with that of vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 4B). This reduction in plasma neuraminidase activity was associated with a significant reduction in stiffness of the aortic endothelium and a concomitant increase in glycocalyx length, as assessed by AFM in isolated aortic explants (Fig. 4, C and D). No significant changes in aortic stiffness were observed as determined in vivo via PWV (Fig. 4E). Notably, significant improvements in ex vivo femoral artery endothelium-dependent FMD, acetylcholine- and insulin-induced vasodilatory responses were observed (Fig. 4, F–H) in zanamivir-treated mice. Treatment with zanamivir did not affect endothelium-independent vasodilatory responses induced by the NO donor, sodium nitroprusside (Fig. 4I), or induced any changes in vascular remodeling or stiffness of the femoral arteries (Fig. 4, J–M). These data indicate that neuraminidase inhibition in vivo with zanamivir can improve vascular endothelial responses to mechanical and humoral stimuli in the setting of T2D.

Figure 4.

In vivo neuraminidase inhibition improves endothelial function in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. A: plasma zanamivir concentrations as assessed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in male C57BL/6J mice exposed (zanamivir, n = 4) or not (control, n = 4) to two doses of 5 mg zanamivir inhalation 12 h apart. B: plasma neuraminidase activity in male db/db mice administered zanamivir (n = 8) or vehicle (n = 8) via inhalation for 5 days. Plasma neuraminidase activity is expressed as fold difference from vehicle. C: endothelial stiffness in aortic explants isolated from zanamivir-treated mice (n = 7) and vehicle-treated controls (n = 7), as assessed by atomic force microscopy (AFM). D: glycocalyx length in aortic explants isolated from zanamivir-treated mice (n = 4) and vehicle-treated controls (n = 4) as assessed by AFM. E: aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV) in zanamivir-treated mice (n = 7) and vehicle-treated controls (n = 7). F–I: isolated femoral artery vasodilatory responses to intraluminal flow-induced shear stress (F), acetylcholine (G), insulin (H), or sodium nitroprusside (I). Vasodilation is expressed as percent change in diameter from the preconstriction induced by phenylephrine in arteries isolated from zanamivir-treated mice (n = 5–7) and vehicle-treated controls (n = 6–7). J–M: zanamivir treatment does not affect the mechanical characteristics of femoral arteries isolated from db/db mice and tested under passive conditions. J: internal diameter. K: mean wall thickness. L: incremental modulus of elasticity (Einc). M: cross-sectional compliance (CSC). Vehicle (n = 7)- and zanamivir (n = 7)-treated mice. Data are expressed as means ± SE. *P ≤ 0.05, zanamivir vs. control (vehicle) as determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (A, C, and D), one-tailed Mann–Whitney U test (B), and two-way ANOVA (repeated measurements) for the interaction between main effects followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test (G and H).

Inhaled Zanamivir Treatment Does Not Decrease Plasma Neuraminidase Activity or Improve Glycocalyx and FMD in Patients with T2D

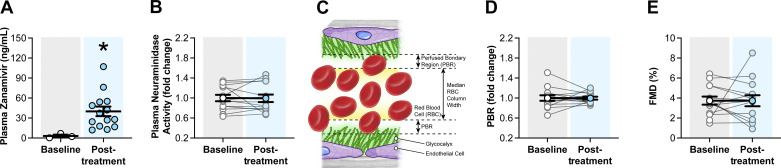

To assess the translatability of our neuraminidase inhibition findings in mice to humans, we performed a clinical trial in which zanamivir was administered to subjects with T2D via inhalation for 5 days as currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of influenza. We decided to assess outcomes before and after treatment using a single-arm design. This decision was driven by the unavailability of a placebo that fully recapitulates the characteristics of the medication used (Relenza, GlaxoSmithKline), and by the expected lack of a 5-day time effect (64). Outcomes included measurements of plasma levels of zanamivir, neuraminidase activity, brachial artery FMD, and GlycoCheck-assessed PBR. No sex differences were detected in the outcomes. Thus, data from both sexes were combined for analysis. After 5 days of treatment, zanamivir reached a concentration of 40.0 ± 7.2 ng/mL in plasma (Fig. 5A). This modest increase in plasma zanamivir following treatment was not associated with changes in blood pressure (Table 2), a reduction in plasma neuraminidase activity, or with an increase in glycocalyx thickness (as assessed by PBR) or endothelial function (as assessed by FMD) (Fig. 5, B–E). These results suggest that use of zanamivir at its currently FDA-approved inhaled dosage for the treatment of influenza is not capable of reducing plasma neuraminidase activity or affecting vascular endothelial function in T2D humans.

Figure 5.

Inhaled zanamivir does not decrease plasma neuraminidase activity or improve noninvasive measurements of vascular function in humans with type 2 diabetes (T2D). A: plasma zanamivir concentrations as assessed with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in subjects with T2D before treatment (baseline, open circles, n = 3) and following treatment (posttreatment, blue circles, n = 14) with inhaled zanamivir. B: plasma neuraminidase activity in subjects with T2D before treatment (baseline, open circles, n = 14) and following treatment (posttreatment, blue circles, n = 14). Plasma neuraminidase activity is expressed as fold change from baseline. C: schematic illustration of the perfused boundary region (PBR) created by the separation between the endothelial glycocalyx and flowing red blood cells in the lumen of an artery. D: PBR as determined with side-stream dark field video microscopy in subjects with T2D before treatment (baseline, open circles, n = 14) and following treatment (posttreatment, blue circles, n = 14) with inhaled zanamivir. PBR is expressed as fold change from baseline. E: brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) expressed as percent change in arterial diameter in subjects with T2D before treatment (baseline, open circles, n = 14) and following treatment (posttreatment, blue circles, n = 14) with inhaled zanamivir. Data are expressed as means ± SE. *P ≤ 0.05, posttreatment vs. baseline as determined by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test (A).

Table 2.

Brachial artery characteristics during flow-mediated dilation and blood pressure before and after zanamivir treatment

| Characteristics | Baseline | Posttreatment |

|---|---|---|

| Brachial artery | ||

| Baseline diameter, mm | 3.88 ± 0.10 | 3.89 ± 0.10 |

| Time-to-peak dilation, s | 71 ± 6 | 66 ± 8 |

| Peak diameter, mm | 4.03 ± 0.10 | 4.03 ± 0.10 |

| Absolute change in diameter, mm | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| Mean shear rate, s−1 | 136 ± 17 | 132 ± 23 |

| Shear rate AUC, AU | 38,079 ± 8,861 | 34,456 ± 6,902 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | ||

| Systolic | 129.00 ± 3.66 | 128.79 ± 3.69 |

| Diastolic | 76.93 ± 1.65 | 79.21 ± 1.47 |

| MAP | 94.29 ± 1.94 | 95.74 ± 1.91 |

Values are means ± SE. AUC, area under the curve; AU, arbitrary units; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

DISCUSSION

The primary findings of this study are that treatment with inhaled zanamivir reduces plasma neuraminidase activity, increases glycocalyx length, and improves endothelial function in diabetic db/db mice. Our results further indicate that human patients with T2D have increased plasma neuraminidase activity that correlates with endothelial dysfunction, but that inhaled zanamivir in its current FDA-approved dosage of 10 mg twice a day for 5 days is not sufficient for reducing plasma neuraminidase activity or improving endothelial function in patients with T2D. Data further show that neuraminidase activity sheds multiple components of the endothelial glycocalyx and that such glycocalyx degradation impairs FMD and is a likely contributor to endothelial dysfunction in T2D.

A large body of evidence indicates that diabetes is a major risk factor for CVD and CVD-related mortality (3, 4). From a clinical perspective, effective treatment of CVD in T2D is complicated by the complex multifactorial manner in which diabetes affects the cardiovascular system. However, regarding disease progression, endothelial dysfunction is considered a common early pathological feature linking T2D to CVD (65–69). Indeed, endothelial dysfunction is closely associated with insulin resistance and is itself a risk factor for CVD and adverse cardiovascular events (6, 70, 71). The pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes is not fully known, but has been attributed to multiple factors such as hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance (72). Interestingly, the defining pathophysiological signs of endothelial dysfunction, including reduced FMD and increased vascular permeability, are also pathologies associated with endothelial glycocalyx degradation (16, 73, 74). Moreover, numerous factors implicated in mediating endothelial dysfunction in T2D also have deleterious effects on glycocalyx structure and function. For example, it has been demonstrated that acute hyperglycemia reduces glycocalyx volume by ∼50% and simultaneously impairs endothelium-dependent FMD in healthy volunteers (14). Furthermore, endothelial glycocalyx volume is reduced in individuals with T2D (75), and this coincides with impaired endothelial function (17–19, 76). Therefore, we posit that degradation of the glycocalyx contributes to endothelial dysfunction in diabetes, and is thus a potential target for therapeutic interventions to ameliorate cardiovascular complications in T2D.

We have previously shown that plasma neuraminidase activity is increased in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance (20). It has also been reported that circulating neuraminidase activity is elevated in animal models of diabetes as well as in human subjects with diabetes (20–24). Moreover, serum concentrations of sialic acid, the enzymatic byproduct of neuraminidase, are elevated in patients with diabetes (21, 22, 24–32). How upregulation of plasma neuraminidase activity occurs in T2D is not known. However, it was recently reported that in rat hepatoma cells expressing wild-type human insulin receptor, exogenously applied insulin dose dependently increases neuraminidase activity (77). That report, coupled with our previous observation that plasma neuraminidase is significantly elevated in hyperinsulinemic mice (20), suggests that hyperinsulinemia may drive the upregulation of neuraminidase in patients with T2D. Additional studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

Herein, we corroborated that plasma neuraminidase activity is increased in subjects with T2D, and extended that finding by providing evidence that those same subjects have reduced NO bioavailability and endothelial dysfunction as determined by the presence of diminished plasma nitrite concentrations and impaired FMD (36). The correlation of those variables further indicates that as plasma neuraminidase activity increases there is a reduced capacity of the endothelium to produce NO in response to shear. Taken together, this confirms that in human subjects there is an association between T2D, increased circulatory neuraminidase activity, presence of glycocalyx degradation components in circulation, reduced vascular NO bioavailability, and a dysfunctional capacity of the arterial endothelium to induce vasodilation in response to blood flow-induced shear stress.

To demonstrate a direct effect of neuraminidase in reducing the capacity of the endothelium to induce vasodilation in response to increased shear stress, we exposed isolated femoral and small mesenteric arteries intraluminally to exogenous neuraminidase. We chose those arteries as both resistance (small mesenteric arteries) and conduit muscular (femoral) vessels are highly responsive to FMD (78). Our results indicate that intraluminal exposure to neuraminidase markedly blunts the capacity of both small mesenteric and femoral arteries to respond with vasodilation upon increasing the levels of flow-induced shear stress, and that this is associated with a reduction in the amount of glycocalyx covering the luminal surface of the arterial endothelium. As the glycocalyx is in a constant cycle of degradation and synthesis, we wanted to corroborate that neuraminidase activity in vivo also degrades the endothelial glycocalyx and reduces FMD responses. This is particularly important when considering that sialic acid, the main substrate of neuraminidase, could be readily reincorporated into glycocalyx structures in vivo. For this purpose, we infused mice with two intravenous boluses of exogenous neuraminidase 24 h apart and subsequently (24 h later) euthanized the animals and excised their aortae and femoral arteries. AFM assessment of aortic en face preparations showed that in vivo neuraminidase shortened the length of the endothelial glycocalyx and that this was prevalent 24 h after exposure to the enzyme. Others have also shown that neuraminidase treatment of isolated rabbit or porcine femoral arteries reduces FMD with a concomitant reduction in NO generation (79, 80). Herein, we further show that these effects of neuraminidase are not readily dampened in vivo. Consistent with our findings, there are reports indicating that a negative correlation exists between serum sialic acid and NO levels in patients with diabetes (33, 34). All these results indicate that circulating neuraminidase activity can induce endothelial dysfunction manifested as diminished FMD. They further suggest that the mechanism by which elevated neuraminidase activity results in depressed FMD responses involves endothelial glycocalyx degradation. A damaged glycocalyx impairs the endothelium capability for mechanosensation of shear and increases vascular permeability, both of which are associated with reduced NO bioavailability and are hallmarks of T2D-associated endothelial dysfunction (14, 16, 73, 74).

To determine if neuraminidase reduces cell surface glycocalyx structures that have been associated with shear mechanosensation by the endothelium, we exposed endothelial cells in culture to exogenous neuraminidase and subsequently measured the cell surface for the presence of 1) lectin-binding glycocalyx components or the moiety, sialic acid, using WGA and MAA/MAL I + II; 2) the glycosaminoglycan, hyaluronan, using a versican core protein that binds the disaccharide that comprises hyaluronan via two proteoglycan tandem repeats within its G1 domain; and 3) the glycocalyx proteoglycan, syndecan-1, using an antibody that binds an ectodomain epitope of this heparan-sulfate proteoglycan. Our results show that neuraminidase diminishes the presence of these components of the glycocalyx on the surface of endothelial cells. These findings are supported by previous publications demonstrating that neuraminidase-treated mouse mesenteric arteries display a reduction in lectin binding to their endothelium, indicative of sialic acid release and a reduction in glycocalyx volume (81). As mentioned, the glycocalyx is a thin layer of matrix proteins containing glycans that are, for the most part, sialylated during transit through the secretory pathway (11). These sugar additions are susceptible to enzymatic cleavage by neuraminidase, which hydrolyzes the glycosidic linkages of sialic acid with proteins, lipids, and other sugars (49). As such, our observation that treatment of endothelial cells with neuraminidase decreases the binding of WGA or MAA/MAL I + II to the cell surface is consistent with the notion that neuraminidase activity results in shedding of sialic acid from the endothelial glycocalyx. Exposure to neuraminidase also led to shedding of syndecan-1 and hyaluronan from the endothelial surface, which agrees with previous reports indicating that neuraminidase activity reduces the thickness of the glycocalyx present on endothelial cells (82). We chose to measure hyaluronan and syndecan-1 because their relative abundance on the endothelial cell surface has been posited to reflect the integrity of the glycocalyx and because both have been associated with the glycocalyx mechanosensitive capacity (60, 61, 83). Our results clearly show that exposure to neuraminidase induced shedding of hyaluronan and syndecan-1 from the surface of endothelial cells. However, the specific mechanisms by which neuraminidase causes shedding of these glycocalyx components remain to be fully elucidated.

In addition to the depletion of mechanosensitive structures within the glycocalyx, the release of degradation components and subsequent activation of downstream signaling pathways may also play a role in reducing arterial vasodilatory function. Notably, the targets of neuraminidase activity are sialylated proteins and lipids. Cleavage of sialic acid from these structures liberates the molecule from within the endothelium and allows for entry into the circulation, where it can bind downstream effectors, such as sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectins. These sialic acid receptors, termed siglecs, are mainly involved in the negative regulation of immune responses; however, there is evidence that siglec activation can lead to the production and release of inflammatory cytokines including various interleukins (IL) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (84). These inflammatory cytokines have in turn been implicated in the downregulation of eNOS generated NO. For example, IL-6 inhibits eNOS activity via increased expression of caveolin-1, which subsequently binds and inhibits eNOS activation (85). TNF-α has as well been shown to cause endothelial dysfunction via multiple pathways including its reducing eNOS mRNA stability and decreasing eNOS protein production (86). Herein, we also demonstrate that neuraminidase reduces the presence of hyaluronan on the cell surface, which presumably leads to the release of both small and large hyaluronan fragments into the circulation. These fragments are generally characterized as low- and high-molecular weight hyaluronan. The larger polymers are implicated in maintaining vascular integrity and barrier function, whereas the smaller fragments are proinflammatory and immunostimulatory (87, 88). There is also evidence that low-molecular weight hyaluronan promotes RhoA-GTP formation and activation of Rho kinase leading to formation of actin stress fibers (87, 88). Cellular increase in F-actin content has in turn been shown to promote arterial stiffening and reduce endothelium-dependent vasodilatory responses (89, 90). Although these reports suggest that glycocalyx fragments in circulation may participate in promoting endothelial dysfunction and reducing FMD responses, our results in isolated vessels indicate that neuraminidase-induced reductions in endothelial glycocalyx content are sufficient to impair FMD responses. In our experiments, vessels were pretreated +/− neuraminidase in the presence of flow and shed components of the glycocalyx removed from the system before FMD assessment as the perfusate was not recirculated. Naïve perfusate was then used to assess vasodilatory responses to increasing increments of flow. We observed a significant reduction in flow-induced vasodilatory responses in the neuraminidase-treated cohort and this was in the absence of shed components within the perfusate.

Based on the aforementioned results, we hypothesized that neuraminidase inhibition with zanamivir would improve endothelial function in diabetes. We chose zanamivir as the neuraminidase inhibitor because it is currently an FDA-approved neuraminidase inhibiting drug with one of the highest IC50 for mammalian neuraminidases (91). To test our hypothesis, we treated male db/db mice with zanamivir (5 mg) twice a day for 5 days via inhalation. The dosage regimen of zanamivir was chosen to increase the translatability of our findings, as zanamivir inhalation twice a day for 5 days is the currently approved prescription for the treatment of influenza. Male db/db mice were chosen as a model because these mice develop overt diabetes by ∼8 wk of age and exhibit pathologies consistent with glycocalyx degradation and endothelial dysfunction including diminished vasodilatory responses to flow-induced shear stress (92–98). In addition, male diabetic mice present with endothelial dysfunction in resistance vessels more prevalently than females (99) and our previous data indicate obesity in male mice is associated with increased plasma neuraminidase activity (20). In support of our hypothesis, we found that zanamivir treatment for 5 days reduced plasma neuraminidase activity and increased endothelial glycocalyx length (thickness) with associated improvements in several indices of endothelial function (i.e., reduced endothelial cell stiffness and augmented endothelium-dependent vasodilation). Our observations that endothelial glycocalyx length and FMD were increased in zanamivir-treated mice suggests that improved mechanosensation by a restored glycocalyx was the mechanism by which zanamivir enhanced FMD in the diabetic mice. We also observed increased vasodilatory responses to acetylcholine and insulin. As it has been previously shown that mechanosensation of shear stress increases eNOS expression (100), these findings suggest that endothelial glycocalyx restoration in zanamivir-treated mice increased shear mechanosensation and potentially promoted eNOS expression, thus improving vasodilatory responses to acetylcholine and insulin, which are NO dependent. Indeed, neuraminidase activity has been shown to promote cell transmigration and has deleterious effects on cell viability (101, 102). In comparison, laminar shear stress improves overall endothelial function by inducing the synthesis and translocation of cellular components that enhance NO production (103, 104). This supports our postulate that in addition to protecting mechanosensitive structures in the endothelium, inhibition of endogenous neuraminidase activity in the setting of diabetes improves overall endothelial health. Our results suggest that a 1-h exposure to neuraminidase was sufficient to shed sialic acid from the cell surface but not long enough to cause negative effects on ACh or insulin-mediated vasodilation. In contrast, the 5-day treatment with zanamivir was sufficient to improve endothelial cell function by likely facilitating the beneficial effects of shear stress to take place subsequent to improvements in mechanosensation and mechnotransduction. We did not compare ACh or insulin-mediated vasodilatory responses between zanamivir and vehicle-treated mice with those of heterozygous (db/+) or wild type mice, which limited the capacity of our study to determine the level of endothelial restoration achieved by neuraminidase inhibition on those specific functions. Because enhanced endothelial function is typically associated with reduced arterial stiffness (105, 106), we expected aortic PWV and femoral artery modulus of elasticity to decrease in zanamivir-treated mice. However, this did not occur, most likely because of the short duration of treatment. It remains to be determined if prolonged neuraminidase inhibition can reduce stiffness of the vascular wall in diabetic mice.

To begin translation of our findings in db/db mice to human subjects, we implemented a clinical trial in which subjects with T2D received zanamivir (10 mg) via inhalation twice a day for 5 days. This zanamivir treatment regimen did not reduce plasma neuraminidase activity, increase FMD, or improve glycocalyx integrity. Importantly, zanamivir concentrations in circulation only reached 40.0 ± 7.2 ng/mL in these subjects, whereas in mice detectable concentrations of plasma zanamivir attained 225.8 ± 22.0 ng/mL. This is likely the result of differences in the amount of drug powder reaching the alveolar epithelium after inhalation, which would have been greater in mice than in humans. The end result was that the dosing regimen of zanamivir successfully reduced plasma neuraminidase activity in mice but not in humans. Additional experiments are needed to determine if increasing the dosage or modifying the route of administration would increase zanamivir in plasma to concentrations capable of reducing neuraminidase activity, increase glycocalyx thickness, and improve endothelial function in humans with T2D.

Zanamivir has a higher IC50 versus mammalian neuraminidase-3 when compared with other FDA-approved neuraminidase inhibitors and neuraminidase-3 is the most prevalent isoform found in human plasma and the most prominent sheddase of sialic acid residues found on the cell surface (49, 107). Therefore, although the neuraminidase activity assay we used in this study does not differentiate between enzyme isoforms, it is likely that the enzyme activity we measured in plasma was that of neuraminidase-3. Use of animals with specific neuraminidase isoform deletion or overexpression should determine the role of the different enzyme isoforms in promoting endothelial glycocalyx degradation in the setting of T2D whereas use of a neuraminidase-3- or mammalian-specific neuraminidase inhibitor should produce more robust endothelial function improvements in animal models of T2D and potentially effective results in human subjects.

In aggregate, our data indicate that, in the setting of T2D, elevated circulating neuraminidase can increase the desialylation of glycoproteins and proteoglycans that comprise the endothelial glycocalyx (Fig. 6A). We posit that this, in turn, shifts the equilibrium of glycocalyx biosynthesis and degradation to favor degradation, resulting in a reduced mechanosensing capacity of the endothelium that consequently decreases endothelial-dependent production of NO and FMD (Fig. 6B). This decrease in shear mechanotransduction signaling may contribute to endothelial dysfunction in T2D and may be ameliorated by neuraminidase inhibition.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the model whereby increased plasma neuraminidase activity in type 2 diabetes (T2D) causes endothelial dysfunction. A: increased plasma neuraminidase activity in T2D sheds sialic acid from the luminal surface of the endothelium and favors glycocalyx degradation over glycocalyx synthesis. B: representative confocal image of the endothelial glycocalyx stained with fluorescently tagged wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, green) and cell nuclei with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue) in a control mouse mesenteric artery and an artery treated intraluminally with exogenous neuraminidase; scale bar = 50 µm. The decreased amount of glycocalyx caused by neuraminidase activity is proposed to reduce the mechanosensation capacity of the endothelium to blood flow-induced shear stress and thus diminish shear generated nitric oxide and flow-mediated dilation in T2D.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01 HL153264 (to L.A.M.-L. and J.P.), R01 HL137769 (to J.P.), R01 HL136386 (to S.B.B.), R01 HL142770 (to C.M.-A. and Diversity Supplement to T.G.), and R01 HL088105 (to L.A.M.-L.) and National Science Foundation Grant CBET-1403228 (to L.A.M.-L.).

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Pending US patent Application, Serial No. 16/754,814. Entitled: Neuraminidase Inhibition to Improve Glycocalyx Volume and Function to Ameliorate Cardiovascular Diseases in Pathologies Associated with Glycocalyx Damage (filed, 9 April 2020; Ref. No. 17UMC103).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.A.F., F.I.R.-P., J.P., and L.A.M.-L. conceived and designed research; C.A.F., F.I.R.-P., J.A.S., T.G., M.M.-Q., N.J.M., M.A.A., G.P., K.B., and A.R.A. performed experiments; C.A.F., F.I.R.-P., J.A.S., T.G., M.M.-Q., N.J.M., M.A.A., G.P., K.B., and A.R.A. analyzed data; C.A.F., F.I.R.-P., S.B.B., C.M.-A., J.P., and L.A.M.-L. interpreted results of experiments; C.A.F. and F.I.R.-P. prepared figures; C.A.F. and F.I.R.-P. drafted manuscript; C.A.F., F.I.R.-P., J.A.S., T.G., M.M.-Q., N.J.M., M.A.A., G.P., K.B., A.R.A., S.B.B., C.M.-A., J.P., and L.A.M.-L. edited and revised manuscript; C.A.F., F.I.R.-P., J.A.S., T.G., M.M.-Q., N.J.M., M.A.A., G.P., K.B., A.R.A., S.B.B., C.M.-A., J.P., and L.A.M.-L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Gehrke Proteomics Center at the University of Missouri for measuring zanamivir concentrations in plasma samples and the nursing team at the Clinical Research Center for support. This work was also supported, in part, by the use of resources and facilities at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans Hospital in Columbia, MO.

REFERENCES

- 1. Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev 93: 137–188, 2013. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes 54: 1615–1625, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laakso M. Cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: challenge for treatment and prevention. J Intern Med 249: 225–235, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Laakso M. Cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes from population to man to mechanisms: the Kelly West Award Lecture 2008. Diabetes Care 33: 442–449, 2010. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roberts AC, Porter KE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res 10: 472–482, 2013. doi: 10.1177/1479164113500680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cersosimo E, DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction: the road map to cardiovascular diseases. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 22: 423–436, 2006. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lerman A, Zeiher AM. Endothelial function: cardiac events. Circulation 111: 363–368, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153339.27064.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tarbell JM, Pahakis MY. Mechanotransduction and the glycocalyx. J Intern Med 259: 339–350, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yen W, Cai B, Yang J, Zhang L, Zeng M, Tarbell JM, Fu BM. Endothelial surface glycocalyx can regulate flow-induced nitric oxide production in microvessels in vivo. PLoS One 10: e0117133, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Foote CA, Soares RN, Ramirez-Perez FI, Ghiarone T, Aroor A, Manrique-Acevedo C, Padilla J, Martinez-Lemus L. Endothelial glycocalyx. Compr Physiol 12: 3781–3811, 2022. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c210029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lipowsky HH. Microvascular rheology and hemodynamics. Microcirculation 12: 5–15, 2005. doi: 10.1080/10739680590894966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Henry CB, Duling BR. TNF-α increases entry of macromolecules into luminal endothelial cell glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H2815–H2823, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vink H, Constantinescu AA, Spaan JA. Oxidized lipoproteins degrade the endothelial surface layer: implications for platelet-endothelial cell adhesion. Circulation 101: 1500–1502, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.13.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nieuwdorp M, van Haeften TW, Gouverneur MC, Mooij HL, van Lieshout MH, Levi M, Meijers JC, Holleman F, Hoekstra JB, Vink H, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. Loss of endothelial glycocalyx during acute hyperglycemia coincides with endothelial dysfunction and coagulation activation in vivo. Diabetes 55: 480–486, 2006. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huxley VH, Williams DA. Role of a glycocalyx on coronary arteriole permeability to proteins: evidence from enzyme treatments. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1177–H1185, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelly R, Ruane-O'Hora T, Noble MI, Drake-Holland AJ, Snow HM. Differential inhibition by hyperglycaemia of shear stress- but not acetylcholine-mediated dilatation in the iliac artery of the anaesthetized pig. J Physiol 573: 133–145, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ravikumar R, Deepa R, Shanthirani C, Mohan V. Comparison of carotid intima-media thickness, arterial stiffness, and brachial artery flow mediated dilatation in diabetic and nondiabetic subjects (The Chennai Urban Population Study [CUPS-9]). Am J Cardiol 90: 702–707, 2002. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02593-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bhargava K, Hansa G, Bansal M, Tandon S, Kasliwal RR. Endothelium-dependent brachial artery flow mediated vasodilatation in patients with diabetes mellitus with and without coronary artery disease. J Assoc Physicians India 51: 355–358, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henry RM, Ferreira I, Kostense PJ, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, Kamp O, Bouter LM, Stehouwer CD. Type 2 diabetes is associated with impaired endothelium-dependent, flow-mediated dilation, but impaired glucose metabolism is not; The Hoorn Study. Atherosclerosis 174: 49–56, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Foote CA, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Ramirez-Perez FI, Jia G, Hill MA, Reyes-Aldasoro CC, Sowers JR, Martinez-Lemus LA. Arterial stiffening in western diet-fed mice is associated with increased vascular elastin, transforming growth factor-β, and plasma neuraminidase. Front Physiol 7: 285, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roozbeh J, Merat A, Bodagkhan F, Afshariani R, Yarmohammadi H. Significance of serum and urine neuraminidase activity and serum and urine level of sialic acid in diabetic nephropathy. Int Urol Nephrol 43: 1143–1148, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9891-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Merat A, Arabsolghar R, Zamani J, Roozitalab M. Serum levels of sialic acid and neuraminidase activity in cardiovascular, diabetic and diabetic retinopathy patients. Iran J Med Sci 28: 123–126, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hirano F, Honjo K, Uehara S, Hirayama A. Clinical significance of erythrocyte membrane sialic acid and serum sialidase activity in patients with diabetic mellitus. J Jpn Diabetes Soc 33: 125–130, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rasool M, Malik A, Khan KM, Iqbal S, Qazi MH, Imran M, Naseer MA. Time dependent changes in circulating biomarkers during diabetic pregnancies: a perspective case study. Life Sci J 11: 91–96, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prathiroopa, Kavyashree SJ, Ashwitha KM, Suresh Babu TV, Shantaram M. Serum l-fucose, total sialic acid and ceruloplasmin levels in type II diabetic subjects of Somwarpet Taluk—a preliminary study. Int J Pharm Biol Sci 2: 14–20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26. K P, Kumar J A, Rai S, Shetty SK, Rai T, Begum M, Md S. Predictive value of serum sialic acid in type-2 diabetes mellitus and its complication (nephropathy). J Clin Diagn Res 7: 2435–2437, 2013. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6210.3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Crook MA, Tutt P, Pickup JC. Elevated serum sialic acid concentration in NIDDM and its relationship to blood pressure and retinopathy. Diabetes Care 16: 57–60, 1993. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ekin S, Mert N, Gunduz H, Meral I. Serum sialic acid levels and selected mineral status in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biol Trace Elem Res 94: 193–201, 2003. doi: 10.1385/BTER:94:3:193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen JW, Gall MA, Yokoyama H, Jensen JS, Deckert M, Parving HH. Raised serum sialic acid concentration in NIDDM patients with and without diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care 19: 130–134, 1996. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nayak SB, Bhaktha G. Relationship between sialic acid and metabolic variables in Indian type 2 diabetic patients. Lipids Health Dis 4: 15, 2005. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Subzwari J, Qureshi MA. Relationship between sialic acid and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomedica 28: 131, 2012. [Google Scholar]