Abstract

Individuals aged ≥65 yr will comprise ∼20% of the global population by 2030. Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death in the world with age-related endothelial “dysfunction” as a key risk factor. As an organ in and of itself, vascular endothelium courses throughout the mammalian body to coordinate blood flow to all other organs and tissues (e.g., brain, heart, lung, skeletal muscle, gut, kidney, skin) in accord with metabolic demand. In turn, emerging evidence demonstrates that vascular aging and its comorbidities (e.g., neurodegeneration, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, heart failure, and cancer) are “channelopathies” in large part. With an emphasis on distinct functional traits and common arrangements across major organs systems, the present literature review encompasses regulation of vascular ion channels that underlie blood flow control throughout the body. The regulation of myoendothelial coupling and local versus conducted signaling are discussed with new perspectives for aging and the development of chronic diseases. Although equipped with an awareness of knowledge gaps in the vascular aging field, a section has been included to encompass general feasibility, role of biological sex, and additional conceptual and experimental considerations (e.g., cell regression and proliferation, gene profile analyses). The ultimate goal is for the reader to see and understand major points of deterioration in vascular function while gaining the ability to think of potential mechanistic and therapeutic strategies to sustain organ perfusion and whole body health with aging.

Keywords: endothelial function, K+ channels, myoendothelial coupling, TRP channels, vascular aging

INTRODUCTION

With a level of intensity once elevated to that of published ad hominem attacks in the early 19th century (1), the desire to understand how the cardiopulmonary system delivers life throughout the body via an organized circulatory system is as old as the field of physiology itself. In hindsight as well as the present, this passion is understandable as cardiovascular disease remains the number one killer throughout the world (2) despite an approximate doubling in average life expectancy since then from ∼40 to ∼80 yr old. As a result, modern biomedical science and medicine primarily revolve around the process of aging and the development of comorbidities that accompany it such as sarcopenia, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and dementia [(3); Fig. 1]. At a fundamental level, aging has been an inexorable process defined primarily by nuclear telomere shortening, mitochondrial DNA mutations, lysosomal dysfunction, and deficiencies in nutrient/caloric sensing (4, 5). Such molecular and cellular alterations likely manifest most overtly as an initial impairment in cardiopulmonary function and then development of stiffness of the aorta and large, conduit arteries (6, 7). As a result, a lack of optimal attenuation in pulse pressure as bulk blood flow travels from the heart to other organs will ultimately damage the parenchymal microcirculation throughout the body over time (7, 8). Although not covered here in detail, recent studies indeed demonstrate biological sex-based differences for the development of arterial stiffness during advancing age with a key role for G protein-coupled estrogen receptors (9, 10). Almost all basic science investigation and data surrounding vascular aging have been focused on pathological impacts on isolated cell and organ systems (e.g., brain, skeletal muscle, gut) using reductionist in vitro and ex vivo methods. In addition, there are other groups who are continuously working to adapt the signaling pathways and experimental interventions that have emerged in such studies to living human subjects (e.g., Refs. 11–16).

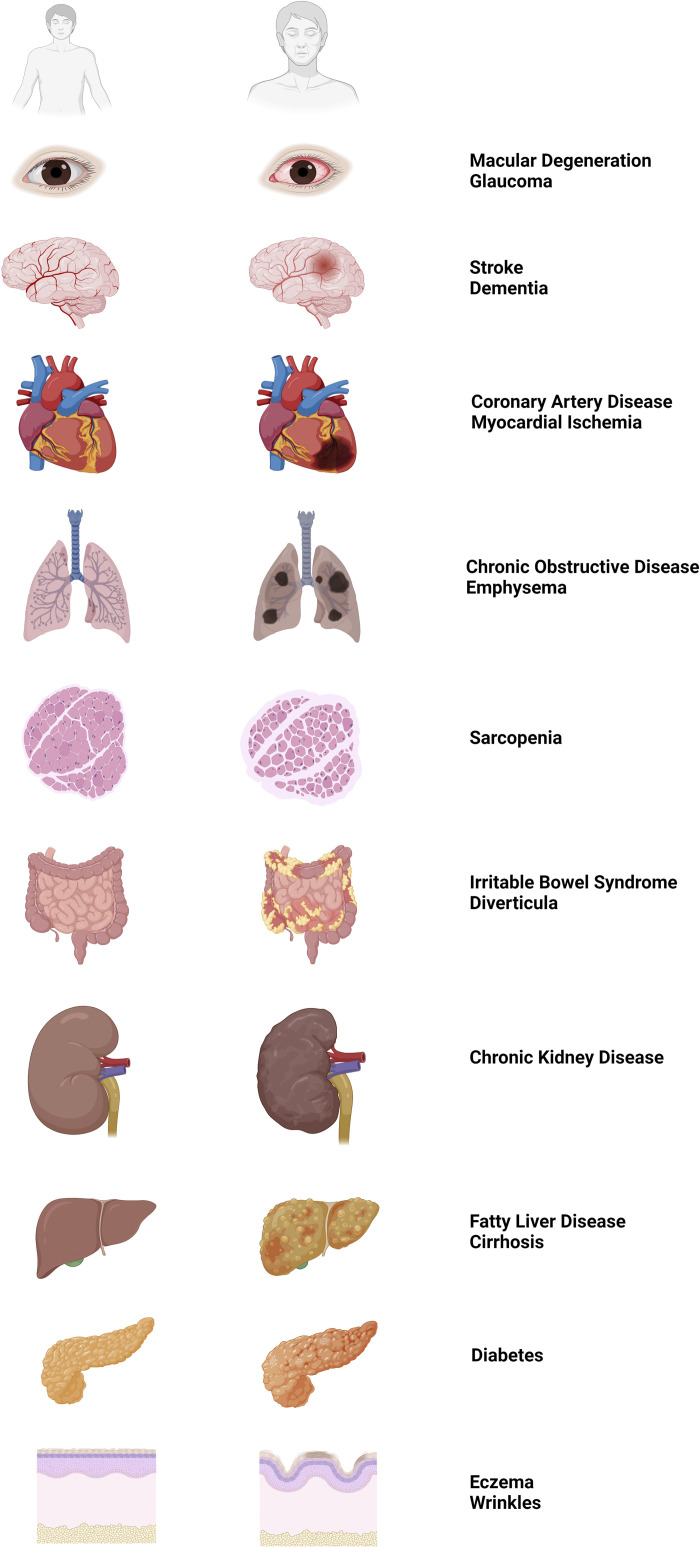

Figure 1.

Aging and the development of chronic diseases among organs throughout the body. Left: cartoon illustrations of healthy organs during young adult age (≈25 yr) as eye, brain, heart, lungs, skeletal muscle, gut, kidney, liver, pancreas, and skin (top to bottom). Middle: corresponding illustrations of diseased organs during old adult age (≥65 yr). Right: list of common diseases that become more prevalent aging as associated with the disease states of each organ illustrated in middle. Images were created with a licensed version of Biorender.com.

In the context of molecular, cellular, and integrative physiology, the current literature review is a concise effort to assemble the most recent data accompanied by refined perspective for the interplay of vascular receptors and ion channels during aging. Prior reviews have examined the biophysical interactions of key vascular ion channels [e.g., calcium-activated K+ (KCa) and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels] and handling of Ca2+ and electrical signals during aging (17–21). Currently, we seek to address distinct functional traits and common arrangements across major organs systems and the role of biological sex where possible as key knowledge gaps. Endothelial cells (ECs) are notably vulnerable with the aging process (22, 23) and thus, the narrative of this review is biased toward endothelial function as a well-coupled cellular network with regard to coordination of both second messengers and electrical signals (17). An overview of classic myoendothelial coupling mechanisms of resistance arteries is presented with updates across major organ systems regarding aging. Furthermore, local and conducted vascular signaling arrangements are discussed in the context of aging and/or chronic disease. Although equipped with awareness of knowledge gaps in the vascular aging field, a section has been included to encompass general feasibility, role of biological sex, additional considerations for cell regression and proliferation, informative value of gene profile analyses, and data interpretation. This manuscript concludes with a sample of numerous outstanding questions that remain for cellular mechanisms underlying optimal balance of discrete and conducted vascular signaling modes to meet metabolic demands throughout the body. The ultimate goal is for the reader to see and understand major points of deterioration in vascular function while gaining the ability to think of potential mechanistic and therapeutic strategies to sustain organ perfusion and whole body health with aging. References to “young” and “old” age throughout the manuscript correspond to rodent ages of ∼3–6 mo (humans: 20–30 yr old) and 22–26 mo (humans: 65–75 yr), respectively (24). Furthermore, unless noted otherwise, discussed data and findings were collected from male animals or where biological sex was not specified for a given study.

CLASSIC SIGNALING ANATOMY OF RESISTANCE ARTERIES

Vascular supply throughout the body is crucial to sustain life through the delivery of oxygen to meet metabolic demand, whereby smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and ECs of the vascular wall regulate resistance to blood flow as vascular dilation or constriction in response to hormones, transmitters, intravascular pressure, and/or shear forces (25). As fully recognized since the 1980s (see Refs. 26–28 for historical perspective), the endothelium lining the intima of the resistance vasculature plays a central role as an intermediary organ that “feeds” all other organs via ≥100 km of blood circulation throughout the body (29, 30). Beginning with an overview, the EC layer communicates with surrounding SMCs to relax and thereby increase blood flow to regions of increased metabolic demand (17). The major endothelium-dependent signaling pathways underlying vasodilation entail 1) production and diffusion of soluble compounds, such as nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), prostaglandins, and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs); and 2) an electrical signal in the form of an intracellular negative charge (hyperpolarization) that conducts through gap junctions between ECs, ECs to SMCs, and vice versa (17) (Fig. 2). Regulation of blood flow to meet tissue metabolic demand involves coordination of vasodilation and constriction over millimeters along the vascular wall within and across different precapillary networks (19, 27). As an electrical property unique to blood vessels (vs. “excitable” cardiac myocytes or neurons), ECs generate a hyperpolarizing signal that is transmitted to surrounding SMCs through myoendothelial gap junctions in an electrotonic manner, a process called endothelium-derived hyperpolarization (EDH) (17).

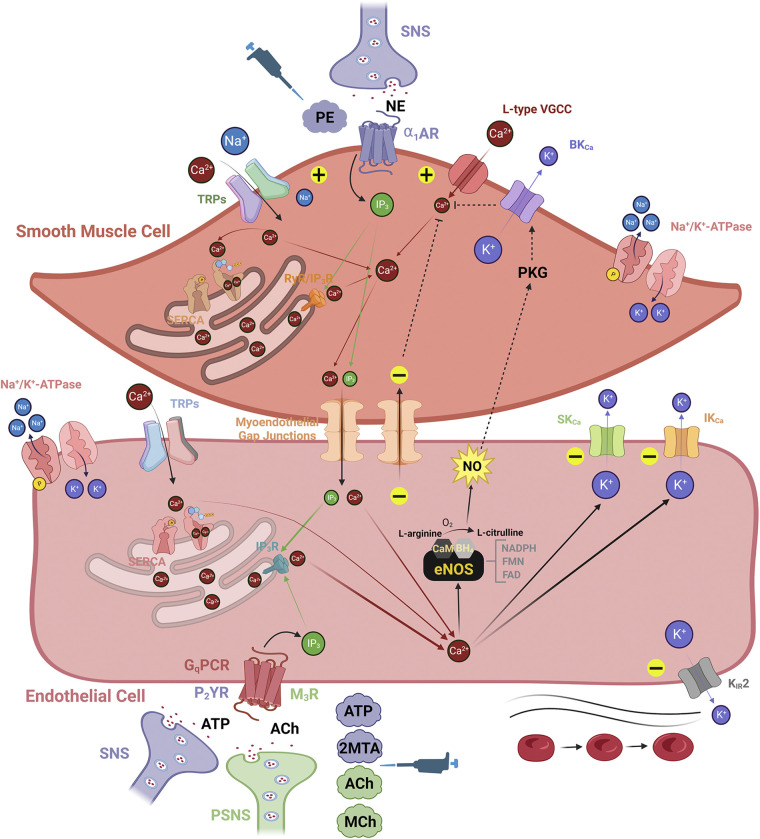

Figure 2.

Classic fundamental anatomy of vascular signaling within resistance arteries: an endothelial perspective. Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) serve the mechanical compliance function of the vascular wall for controlling resistance to blood flow, whereas endothelial cells (ECs) transduce stimuli evoked by signaling molecules carried in the blood within the vascular lumen. The level of [Ca2+]i among cell types in the vascular wall plays a dichotomous role, whereby its global increase in SMCs and ECs generates vasodilation and vasoconstriction, respectively. Either as a cause or effect of increased [Ca2+]i in the vascular wall, vasoconstriction and vasodilation are associated with membrane potential (Vm), indicated as depolarization (“+” sign) and hyperpolarization (“−” sign), respectively. SMC: the primary contributors to elevations in SMC [Ca2+]i are norepinephrine (NE)-stimulated α1-adrenergic receptors (α1ARs) sourced from the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs), and Ca2+-permeant transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (e.g., TRPC3, TRPV3, TRPV4). Also, Na+-permeant TRP channels (e.g., TRPM4) can depolarize SMC Vm and activate L-type VGCCs. A distinct event known as Ca2+ “sparks” in SMCs released from endoplasmic reticulum ryanodine receptors (RyRs) will selectively activate high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels to hyperpolarize SMC Vm while deactivating L-type VGCCs. Note that α1ARs can also be activated by the experimental agonist phenylephrine (PE, see pipettor icon). EC: the contributors to increased EC [Ca2+]i are Gq protein-coupled receptors (GqPCRs; purinergic, P2YR and muscarinic, M3R) activated by adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or acetylcholine (ACh) and Ca2+-permeant TRP channels (e.g., TRPV4). Increased EC [Ca2+]i primarily generates nitric oxide (NO) via endothelial NO synthase (eNOS, see main text for more information) and activates small- and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SKCa and IKCa) channels. In addition to activated SKCa and IKCa channels, hyperpolarization of EC Vm can occur through direct activation of inward-rectifying K+ (KIR) channels via the shear of blood flow or elevated extracellular K+ (6–15 mM). Experimental agonists for P2YRs (2-methylthioadenosine diphosphate or 2MTA) and M3Rs (methacholine or MCh) are also used to mimic actions of the SNS and parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS), respectively (see pipettor icon). Myoendothelial feedback: activation of SMC α1ARs by NE generates inositol-trisphosphate (IP3) to elicit Ca2+ release through IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and thereby produce constriction. When elevated in SMCs for a prolonged period, IP3 and Ca2+ diffuse through myoendothelial gap junctions into the endothelium to activate SKCa and IKCa channels and/or NO production, providing negative feedback to smooth muscle contraction (see broken lines indicating signaling from EC back to SMC). Images were created with a licensed version of Biorender.com.

SMCs and ECs share second messenger signaling molecules such as Ca2+, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) via myoendothelial gap junctions. Electrogenic ions (e.g., Na+, K+, or Cl−) are also distributed from ECs to SMCs in response to stimulation of EC GqPCRs (e.g., muscarinic, M3R; purinergic, P2YR) (31, 32), or vice versa subsequent to SMC α1-adrenergic receptor (α1AR) stimulation (25). Following EC GqPCR activation, IP3 is produced, which in turn activates IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) to release Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) into the cytosol. ER Ca2+ release is observed as the initial “peak” response in the increase in [Ca2+]i (33, 34). The ER Ca2+ stores are filled or refilled through the uptake of Ca2+ from the cytoplasm into the ER through smooth sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) pumps to support repetitive physiological signals. The influx of Ca2+ occurs through TRP channels [e.g., canonical family, TRPC1/3/4/5/6; vanilloid, TRPV1/3/4; ankyrin, TRPA1; melastatin, TRPM3/8; and polycystin, TRPP2 (35–37)] to help refill ER Ca2+ stores and/or sustain elevated [Ca2+]i signals while integral to the secondary “plateau” phase of the Δ[Ca2+]i response following GqPCR stimulation (33, 34). Similar to a Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release mechanism in neurons governed by voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) and ryanodine receptors (RyRs) (38), direct pharmacological activation of TRPV4 channels can trigger a cellular influx of Ca2+ that is then amplified by intracellular Ca2+ release via ER IP3Rs in ECs (39) or RyRs in SMCs (40).

As the central mediator of vascular reactivity, Ca2+ plays opposing roles in SMCs versus ECs for vasoconstriction and vasodilation. Depolarization of SMC membrane potential (Vm) sequentially activates VGCCs [L-type, CaV1.2 and/or T-type, CaV3.1–3.2 (41, 42)] and increases cytoplasmic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) via Ca2+ influx into the cell interior to activate myosin light-chain kinase for myosin light-chain phosphorylation and vasoconstriction. In contrast, following G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) stimulation, EC [Ca2+]i increases activate EC NO synthase (eNOS) and the production of NO concomitant with stimulation of small- and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SKCa and IKCa) channels for EDH, resulting in overall myosin light-chain dephosphorylation and vasodilation. In a process known as myoendothelial “feedback” (43–45), activation of SMC α1ARs increases SMC [Ca2+]i and IP3, whereby excess Ca2+ ions and/or IP3 molecules will pass from SMCs to ECs to activate EC IP3Rs, increase EC [Ca2+]i, and cease further constriction (46). The differential vasoactive responses to increased [Ca2+]i among respective cell layers in combination with open cross talk via myoendothelial gap junctions prevent extreme variations in blood flow up to potential hemorrhage or ischemia.

The production of NO is dependent on the conversion of l-arginine to l-citrulline in the presence of O2 via eNOS activity. The eNOS enzyme contains oxygenase [binds l-arginine, heme, Zn2+, and tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)], calmodulin (CaM; binds Ca2+), and reductase [binds with reducing agents nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), flavin mononucleotide (FMN), and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)] domains (47). SMC relaxation to NO occurs via soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) to produce cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and thereby activate cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKGI) for phosphorylation of several ion pumps and channels including T-type VGCCs (48), sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases (SERCAs) (49), and high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels (50). In such a manner, the relaxant effects of NO can occur as a result of reduced [Ca2+]i (49, 51), hyperpolarized Vm (52, 53), and/or direct interaction with myosin light-chain phosphatase (54, 55) to ultimately decrease myosin light-chain phosphorylation in SMCs. Note that such signaling events at the plasma membrane and throughout the cytoplasm for vascular mechanical movement are rapidly occurring while interdigitated on a timeframe of milliseconds. Thus, their magnitude and sequence of occurrence are extremely difficult to delineate and thus, findings and interpretations among studies may differ in accord with vascular size (e.g., aorta vs. parenchymal arteriole) and/or approach for measuring vascular reactivity (e.g., preconstriction via α1AR activation vs. spontaneous tone due to intravascular pressure alone).

In addition to NO, there are novel gasotransmitters to influence vascular ion channel activity as CO and H2S. CO is generated from heme oxygenases [HO-1, inducible and HO-2, constitutive; expressed in both ECs and SMCs (56)] as a by-product of heme degradation and, like NO, CO stimulates the sGC/cGMP/PKGI pathway (57). Endogenous production of CO favors endothelium-dependent dilation (58), whereby activators include NO (59), cAMP (60), platelet-derived growth factor (61), and glutamate (62). CO can also cause inhibition of SMC T-type VGCCs (CaV3.2) (63) while enhancing the coupling of RyR-generated Ca2+ “sparks” with activation of BKCa channels (64, 65). Note that SMC T-type VGCCs, RyRs, and BKCa channels operate in “microdomains” to influence Vm hyperpolarization while acting as a brake to arterial constriction (66, 67). In contrast to oxidizing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), H2S is a biological reducing agent sourced enzymatically from thiosulfate (cystathionine-γ-lyase), homocysteine (cystathionine-β-synthase), and cysteine (3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase) (68) and nonenzymatically via sulfate-reducing bacteria in the gut (69). H2S has been shown to regulate cardiovascular function at the level of the central nervous system (CNS; hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, rostral and caudal ventrolateral medulla, nucleus tractus solitarius, nucleus ambiguus, intermediolateral medulla; decreased mean arterial pressure and heart rate, increased baroreflex sensitivity), peripheral nerve bodies (sympathetic ganglia; reduced catecholamine release), heart (decreased rate and contractility), and isolated blood vessels (sustained EC function) (reviewed in Ref. 70). Similar to CO, H2S also influences the coupling of cytoplasmic Ca2+ signals with Vm hyperpolarization via sulfhydration of TRPV4 channels (Ca2+ influx) and subsequent activation of BKCa channels (71).

SKCa and IKCa channels are abundantly expressed in arteries and arterioles for blood flow control (72). As demonstrated thus far for the brain in particular, SKCa and IKCa channels are virtually absent in capillary ECs (72, 73) where direct exchange of nutrients and metabolites with metabolically active neurons takes place. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ binds to free CaM which is then tethered to CaM-binding domains of respective carboxyl termini of SKCa (74) and IKCa (75) channels to open their pores and thereby allow for K+ efflux from the cellular interior. Through this mechanism, hyperpolarization of EC Vm occurs in response to sequential ER Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx, notably during treatment with a GqPCR agonist [e.g., acetylcholine (ACh)]. The resulting hyperpolarization of EC Vm transmits to the SMCs via myoendothelial gap junctions (76, 77), whereby L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are deactivated, and similar to the outcome of the NO/cGMP/PKGI pathway, SMC [Ca2+]i is reduced to promote vasodilation (78). Note that when KCa channel function is absent as in ECs of capillaries in the brain (73) or collecting lymphatics of the popliteal fossa (79), an otherwise rapid Vm hyperpolarization response converts into slow Vm depolarization because of accumulation of intracellular positive charges in the form of Na+ and Ca2+ having entered through activated nonselective cation channels containing TRPV4. Consequently, there may be an impairment in the electrical coordination of capillary to precapillary vasodilation and/or production of Ca2+-dependent NO that will relax pericytes for a local increase in capillary blood flow only (80). A similar set of mechanisms for shaping discrete versus conducted vascular signals may guide contraction waves among collecting lymphatics to propel lymph flow as well (79).

IMPACT OF AGING ON RESISTANCE ARTERY FUNCTION: RECEPTOR AND ION CHANNEL FUNCTION ACROSS MAJOR ORGAN SYSTEMS

Old age has been associated with decreased vascular NO bioavailability since the early 2000s across vascular types of several different organs such as the brain, heart, skeletal muscle, and gut (reviewed in Ref. 81). A key mechanism is described by deficiencies in l-arginine and/or BH4 that result in eNOS “uncoupling,” whereby superoxide (O2•−) is produced instead of NO (82). O2•− is directly converted to H2O2 via superoxide dismutase or peroxynitrite (ONOO−) upon reacting with NO (83). In turn, ONOO− will oxidize BH4 to trihydrobiopterin radical (BH3•) and decay to dihydrobiopterin (BH2) to sustain uncoupled eNOS as well (84). The production of ONOO− in tandem with formation of H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals (HO•) also upregulates SKCa and IKCa channel function through direct and indirect mechanisms (17). A multitude of known effects on ion channel function during aging is primarily due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling as illustrated in Fig. 3. Increased SKCa and IKCa channel function during old age sustains local vasodilatory signals. However, at the same time, the consequence of enhanced ion channel activity is the “leak” of electrical charge through the plasma membrane of reduced input resistance and a restricted spatial domain of conducted signaling (reviewed in Ref. 17). As illustrated in Fig. 4, this working paradigm effectively explains dyscoordination of blood flow control along entire vascular resistance networks during aging and development of chronic disease.

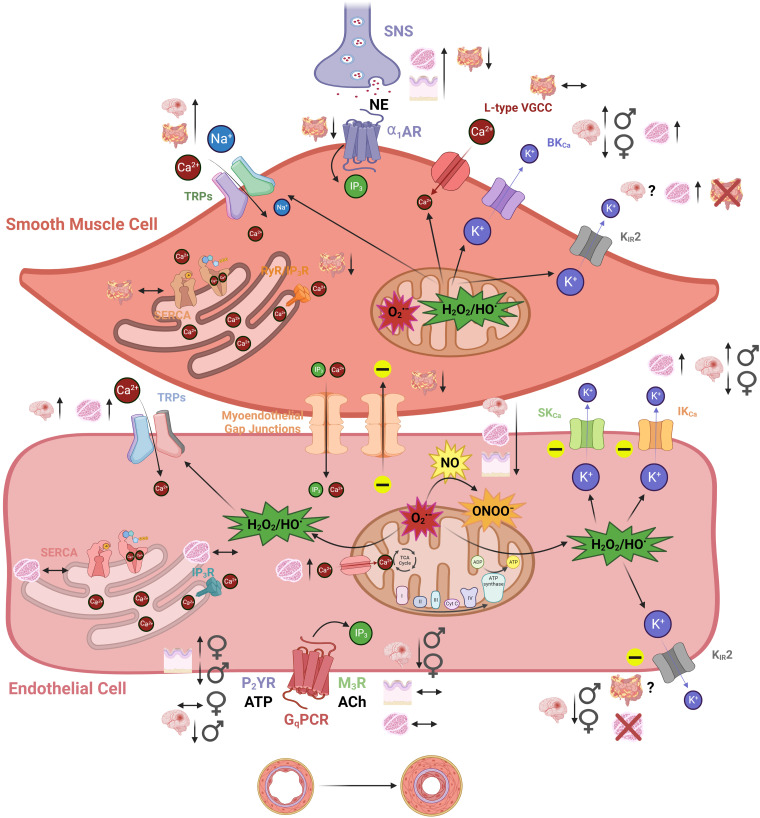

Figure 3.

The impact of aging on classical signaling components within the vascular wall of resistance arteries. There are increases (↑), decreases (↓), or stability (↔) among various smooth muscle cell (SMC) and endothelial cell (EC) receptors and ion channels that govern vascular reactivity during old vs. young age. With brain, gut, skeletal muscle, and skin blood vessels most prominently used for aging studies, various vascular types (and biological sex where applicable/known) are illustrated for both SMCs and ECs. Note that KIR2 channels in particular are expressed in both cell types in brain arteries but not skeletal muscle (SMCs only) or gut (ECs only). Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species signaling via superoxide (O2•−), and hydrogen peroxide/peroxyl radicals (H2O2/HO•) play more of a role during and old age and impact various Ca2+-permeant pathways (e.g., TRP channels) and K+ channels (e.g., SKCa and IKCa). Although not illustrated, other major sources of O2•− include the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases and uncoupled eNOS (see main text). Note that nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability is decreased during old age because of a greater propensity for uncoupled endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) and the reaction of O2•− with NO form peroxynitrite (ONOO−). A primary consequence of altered signaling during aging could be elevated basal constriction and higher vascular resistance as the basis for hypertension. Another outcome may be sustained discrete reactivity to metabolites and neurotransmitters with a decrease in the spatial domain along the vascular wall for conducted signals through endothelial and myoendothelial gap junctions among capillaries, precapillary arterioles, and arteries (see Fig. 4). Images were created with a licensed version of Biorender.com.

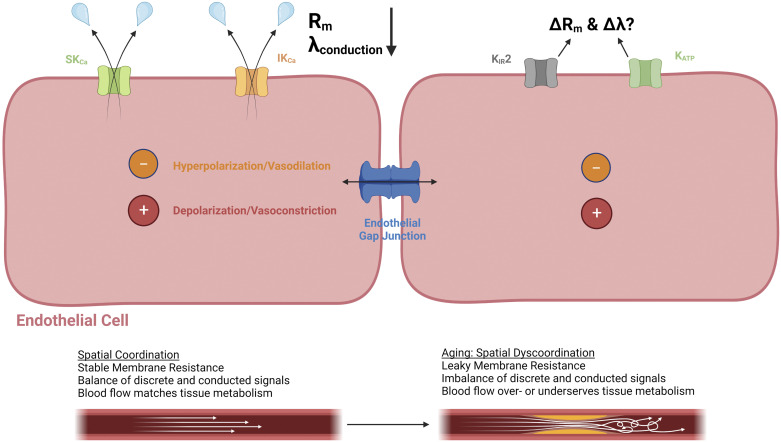

Figure 4.

Conducted vascular signaling and the endothelium as an electrical conduit: leaky ion channels and a restricted spatial domain with aging. In addition to modes of discrete/local changes in vasoreactivity, conducted signaling along the endothelium through gap junctions is crucial for coordinating vascular resistance among arteries, arterioles, and capillaries to match tissue metabolism. With aging, ion channels such as small- and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SKCa and IKCa) channels become “leaky” because of reactive oxygen species and enhanced Ca2+ entry through transient receptor potential channels (TRPs). Where applicable, changes in modulators of KIR2 (phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate or PIP2, cholesterol) and ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP) channels (ATP, H2S) with aging may influence optimal distribution of charge (hyperpolarization, depolarization) and corresponding vasoreactivity (vasodilation, vasoconstriction) as well. The length constant of conduction (λ) is favored by a high membrane resistance (Rm) and low-axial resistance as defined by the open-state probability of ion channels and gap junctions, respectively. The consequences of leaky ion channels with aging are a decrease in Rm and thereby a restricted spatial domain for optimally coordinating changes in vascular resistance to blood flow to meet metabolic demand. Images were created with a licensed version of Biorender.com.

Our view of EC respiration has seen a substantial shift from a glycolysis-centered one (85) to our current understanding, whereby mitochondrial production of ATP is indispensable for the control of vascular tone (86). Especially during old age, EC mitochondria also engage in cytoplasmic Ca2+ buffering and production of ROS (85, 87). It is worth noting that high concentrations of H2O2 (≥100 µM) can depolarize mitochondria and inhibit IP3Rs to altogether decrease mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, resulting in less production of O2•−/H2O2 as well as ATP (88). During aging, the structure for vascular mitochondria becomes relatively larger, immobile, and elongated (89) with increased Ca2+ buffering capacity (33) relative to young adult animals. With recent remarkable breakthroughs in high-throughput cell respiration assays (90, 91) and imaging (92), the research area of vascular mitochondrial signaling and mitophagy (93) requires additional investigation in the context of aging and the development of cardiovascular disease.

With aging, there are also differences in modes of vascular signaling across organs to consider such as how skeletal muscle ECs display robust, sustained [Ca2+]i signals following GqPCR stimulation, whereas [Ca2+]i signals in cerebral artery ECs are relatively low in amplitude and transient (94). Furthermore, there are ion channel expression differences to be aware of such as inward-rectifying K+ (KIR2.1) channels differentially expressed on ECs and/or SMCs depending on vascular type. In the brain, both cell layers express KIR2.1 (95), whereas they are located primarily in only SMCs of skeletal muscle (96) and only ECs in mesentery (97). Note that the KIR2.2 isoform is primarily expressed in arterial SMCs of mouse skeletal muscle (96) and brain (98). However, in young rats, SMC KIR2.1 remains dominant with an absence of SMC KIR2.2 mRNA transcripts in basilar, coronary, and mesenteric arteries (99). In addition, there may be varying degrees of myoendothelial coupling among vascular types and disease states. Although not covered in this review in detail, there are also structural changes to consider such as arterial stiffening, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and an increased wall-to-lumen ratio (100–104) that may manifest differently across organs and further challenge known receptor and ion channel function deficiencies during aging. Indeed, as metabolic demands are different among various organs, the mode of EC function is tailored accordingly, especially when comparing across the microcirculation among the CNS and periphery. For example, blood flow to skeletal muscle is highly dynamic when shifting from rest to exercise (≥50-fold increase) as has been shown throughout numerous demonstrations of robust EC function in cellular, vascular, and integrated study models (17), whereas cerebral blood flow remains relatively stable upon transition to physical activity (105). Thus, it is reasonable to expect an array of differences and similarities in ion channel function among major organ systems during aging as discussed next. A summary of representative studies for altered function of vascular TRP and K+ channels during aging and/or associated diseases across brain, eye, skeletal muscle, mesentery, heart, lung, kidney, and skin is illustrated in Table 1. Accordingly, Figs. 3, 4, and 5 provide visual complementarity as to how vascular receptors and ion channels are impacted by aging.

Table 1.

A summary of representative studies illustrating how aging and associated diseases impact vascular TRP and K+ channels that govern moment-to-moment blood flow across major organ systems

| Animal Model/Species/Age/Sex(es) | Vascular Type | Physiological Approach and Ion Channel Pharmacological Intervention(s) |

Outcome: Ion Channel Function, Old (or diseased) vs. Young (or Healthy Control) |

Reference No. and PMID |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | |||||

| Aging | Mouse C57BL/6N mCAT mouse 4 to 6, 12 to 16, 24 to 28 mo Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Posterior cerebral artery | *Endothelial tubes; sharp electrode Vm recordings and [Ca2+]i photometry *NS309, elevated [K+]o, H2O2 |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂↑; ♀↓ TRP channels: ♂↑; ♀↓ KIR2 channels: ♂↓; ♀↓ |

(94) 31760422 |

| Aging | Rat Sprague-Dawley 3 to 5 and 22 to 26 mo Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Middle cerebral artery | *Intravascular pressure myography, patch clamp *NS1619, IbTX, paxilline, 4-AP |

Smooth muscle BKCa channels: ♂↑; ♀↓ |

(106) 31738403 |

| Aging, hypertension | Mouse C57BL/6N 3 and 24 mo ± ANG II Male ♂ |

Middle cerebral artery | *Intravascular pressure myography *SKF96365, IbTX |

Smooth muscle TRP channels: ♂↑ |

(107) 24097425 |

| Hypertension | Mouse C57BL/6 20 to 23 wk ± ANG II Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Cerebral parenchymal arteriole | *Behavior, cerebral blood flow, intravascular pressure myography *GSK1016790A, NS309, TRAM-34, apamin |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂↔; ♀↔ TRPV4 channels: ♂↓; ♀↔ |

(108) 36897751 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Mouse 3xTg-AD 1 to 2, 4 to 5, 6 to 8, 12 to 15 mo Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Posterior cerebral artery | *Endothelial tubes; sharp electrode Vm recordings and [Ca2+]i photometry *NS309, elevated [K+]o |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂↑; ♀↔ TRP channels: ♂↑; ♀↔ KIR2 channels: ♂↓; ♀↓ |

(109) 32651315 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Mouse 5xFAD and B6SJLF1/J 4 to 5 mo Male ♂ and Female♀ Mouse |

Posterior communicating artery, parenchymal arteriole | *Intravascular pressure myography, en face [Ca2+]i imaging *NS309, apamin, TRAM-34 |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂+♀↔ |

(110) 34465229 |

| Alzheimer’s disease |

5xFAD and B6SJLF1/J 12 to 13 mo Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Capillary | *Cerebral blood flow (whisker stimulation) and patch clamp *diC16-PIP2, elevated [K+]o, BaCl2 |

Endothelium | (111) 33763649 |

| KIR2 channels: ♂+♀↓ | |||||

| Alzheimer’s disease,cerebrovascular inflammation | Mouse hAPP and C57BL/6J TGF-β1 and C57BL/6J hAPP/TGF-β1 and C57BL/6J 3 to 6 mo Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Posterior cerebral artery | *Intravascular pressure myography *GSK1016790A, HC-067047, NS309, apamin, ChTX, SOD, CAT |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂+♀↔ TRPV4 channels: ♂+♀↓ |

(112) 23889563 |

| Alzheimer’s disease,cerebrovascular inflammation | Mouse hAPP and C57BL/6J TGF-β1 and C57BL/6J 3 to 4 and 7 to 10 mo Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Posterior and middle cerebral arteries | *Neuronal activity, cerebral blood flow and intravascular pressure myography *Elevated [K+]o, BaCl2, ML133, CAT, indomethacin |

Smooth muscle and endothelium KIR2 channels: ♂+♀↓ |

(113) 34820829 |

| Eye | |||||

| Diabetic retinopathy | Rat Sprague-Dawley ± STZ Trpv2+/− 3 wk, 3 mo, and 1 yr Male ♂ |

Retinal arterioles | *Electroretinography, intravascular pressure myography, patch clamp *TRPV2 pore-blocking antibodies |

Smooth muscle TRPV2 channels: ♂↓ |

(114) 36134661 |

| Skeletal muscle | |||||

| Aging | Mouse C57BL/6N 4 to 6, 12 to 14, 24 to 26 mo Male ♂ |

Superior epigastric arteries | *Sharp electrode Vm measurements of endothelial tubes *NS309, apamin, ChTX, H2O2, CAT |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂↑ local Vm hyperpolarization to ACh or NS309; conducted hyperpolarization/ depolarization↓ |

(115) 23723370 |

| Aging | Mouse C57BL/6N 3 to 4 and 24 to 26 mo Male ♂ |

Superior epigastric arteries | *Intravascular pressure myography, patch clamp *Paxilline, IbTX, TEA |

Smooth muscle BKCa channels: ♂↑ |

(102) 24705555 |

| Aging | Mouse C57BL/6N 3 to 4 and 24 to 26 mo Male ♂ |

Superior epigastric arteries | *Intravascular pressure myography, patch clamp *Elevated [K+]o, BaCl2 |

Smooth muscle KIR2 channels: ♂↑ |

(96) 28432059 |

| Aging | Rat Fischer 344 4 and 24 mo Male ♂ |

Soleus arterioles (oxidative, slow twitch) Gastrocnemius arterioles (glycolytic, fast twitch) |

*Intravascular pressure myography *4-AP, IbTX |

Smooth muscle BKCa channels: ♂↑ (soleus only) Kv1 channels: ♂↑ (soleus and gastrocnemius) |

(116) 19407249 |

| Obesity | Rat Sprague-Dawley ± high-fat diet 24 to 28 wk Male ♂ |

Saphenous arteries | *Intravascular pressure myography *1-EBIO, CyPPA, apamin, TRAM-34 |

Endothelium IKCa channels: ♂↑ |

(117) 20671071 |

| Heart | |||||

| Aging | Human < 64 and ≥64 yr Male ♂ and Female♀; 83% ♂ (25/30 subjects) |

Coronary arteriole of right atrium | *Intravascular pressure myography *Apamin, TRAM-34 |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂+♀↑ as local vasodilation to bradykinin; conducted vasodilation↓ |

(118) 24778172 |

| Aging, oxidative stress | Mouse C57BL/6 129S4/SvJae × C57BL/6 CerS2 null GPX1/CAT double KO 15 to 25 and 75 to 100 wk Male ♂ and/or Female♀; not specified |

Thoracic aorta | *Wire myography, ROS fluorescence of ECs *1-EBIO, CAT |

Endothelium IKCa channels↑ |

(119) 27363720 |

| Obesity | Rat Obese Zucker and Lean Zucker 17 to 18 wk Male ♂ |

Second-order branches of the left anterior descending coronary artery | *Wire myography, EC [Ca2+]i photometry *GSK1016790A, NS309, apamin, TRAM-34 |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂↑ |

(120) 25302606 |

| Diabetes | Canine Mongrel dogs Age not specified Male ♂ and/or Female♀; not specified |

Subepicardial collateral coronary arteries and arterioles | *Intravital vascular diameter measurements *Apamin, ChTX |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ↑ as compensation to decrease in NO signaling |

(121) 29665152 |

| Lung | |||||

| Chronic hypoxia | Sheep High altitude (3,801 m) and normal altitude (720 m); >100 days Adult; ∼2 yr Female♀ |

Pulmonary artery (4th to 5th branch order) |

*wire myography, [Ca2+]i imaging *TEA |

Smooth muscle BKCa channels: ♀↓ |

(122) 29513562 |

| Chronic hypoxia and pulmonary arterial hypertension | Rat Wistar; hypoxic and normoxic Age not specified Male ♂ |

Pulmonary artery | *wire myography, patch clamp of SMCs *IbTX |

Smooth muscle BKCa channels: ♂↓ |

(123) 14613862 |

| Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension | Human patients with IPAH ∼40 to 50 yr Male ♂ and Female ♀ |

Pulmonary artery | *Pulmonary hemodynamic measurements, patch-clamp of SMCs (single and whole cell) *correolide, bepridil |

Smooth muscle Kv1.5 channels: ♂+♀↓ via KCNA5 gene sequence mutations/single nucleotide polymorphisms |

(124) 17267549 |

| Inherited and idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension | Human patients with PAH <1 to 79 yr Male ♂ and Female ♀ |

Pulmonary artery | *Gene profiling of patients with PAH and whole-cell patch clamp of COS-7 cells with SUR1 variants *Diazoxide, glibenclamide |

Smooth muscle and endothelium KIR6.2 + SUR1 (KATP) channels: ♂+♀↓ via ABCC8 gene sequence mutations/single nucleotide polymorphisms |

(125) 30354297 |

| Inherited and idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension | Human patients with PAH 8 to 49 yr Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Pulmonary artery | *Gene profiling of patients with PAH and whole-cell patch clamp of COS-7 cells with KCNK3 variants *pH < 7.4>, ONO-RS-082 |

Smooth muscle and endothelium K2P channels: ♂+♀↓ via KCNK3 gene sequence mutations/single nucleotide polymorphisms |

(126) 23883380 |

| Mesentery | |||||

| Aging | Mouse C57BL/6 5 to 6 and 29 to 30 mo Male ♂ |

Mesenteric arteries | *[Ca2+]i photometry *Zero to 2 mM [Ca2+]o, CPA, caffeine |

Smooth muscle TRP channels: ♂↑ |

(127) 19017540 |

| Hypertension | Rat Spontaneously hypertensive Wistar–Kyoto 5 mo Male ♂ |

Mesenteric arteries (2nd order) | *Isometric tension myography *NS309, UCL-1684, TRAM-34, ChTX, NS1619, IbTX |

Endothelium and smooth muscle SKCa channels: ♂↓ IKCa channels: ♂↑ BKCa channels: ♂↔ |

(128) 19766962 |

| Hypertension | Rat Spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar-Kyoto 12, 36, and 64 wk Male ♂ |

Mesenteric arteries | *Isometric tension myography, patch clamp *IbTX |

Smooth muscle BKCa channels: ♂↑ |

(129) 29093563 |

| Diabetes | Rat Zucker diabetic fatty and Zucker lean 18 wk Male ♂ |

Mesenteric arteries (3rd order) | *Intravascular pressure myography *1-EBIO, apamin, ChTX, TRAM-34, NS1619, IbTX |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂↑ BKCa channels: ♂↔ |

(130) 25128173 |

| Diabetes and hyperglycemia | Mouse db/db (leptin KO) and C57BLKS/J 11 to 18 wk Male ♂ and/or Female♀; not specified |

Mesenteric artery (feed artery + two side branches) |

*Intravascular pressure myography *Apamin, TRAM-34 |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ↔ as locally stimulated by SLIGRL; conducted vasodilation↓ |

(131) 29339138 |

| Kidney | |||||

| Hypertension | Rat Spontaneous hypertensive Normotensive Sprague–Dawley ∼13 to 16 wk Male ♂ and/or Female♀; not specified |

Renal blood circulation, renal interlobular artery |

*Ultrasonic flow probe, wire myography *(l-NAME and indomethacin; remaining dilation/flow |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ↔ |

(132) 31368238 |

| Diabetes | Rat Wistar ± STZ 16 to 17 wk Male ♂ |

Renal blood circulation | *Ultrasonic flow probe *Apamin, ChTX |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂↔ |

(133) 18635451 |

| Diabetes | Rat Sprague–Dawley ± STZ 10 to 12 wk Male ♂ |

Renal afferent arteriole |

*In vitro blood-perfused juxtamedullary nephron *BaCl2, tertiapin-Q, glibenclamide |

Smooth muscle and endothelium KIR and KATP channels: ♂↑ |

(134) 22252401 |

| Skin | |||||

| Aging | Human 18 to 30 and 60 to 80 yr Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Microcirculation of the ventral forearm | *Microdialysis, Laser Doppler *TEA |

Endothelium KCa channels: ♂+♀↑ |

(14) 32401629 |

| Diabetes | Human 18 to 75 yr; diabetic and nondiabetic Male ♂ and Female♀ |

Subcutaneous artery | *Wire myography *UCL1684, TRAM-34 |

Endothelium SKCa/IKCa channels: ♂ +♀↑ |

(135) 26768833 |

Each row illustrates a select assortment of individual studies that used a specific aging/disease study model; biological sexes (male and/or female); vascular type and segment (arteries, arterioles, or capillaries); physiological approach and use of pharmacological interventions; primary outcome as to whether the function of an endothelial or smooth muscle TRP or K+ channel goes up, down, or remains the same with aging/disease; and the manuscript reference number with accompanying PMID. Note that this table is not necessarily exhaustive of all studies involved in vascular aging and associated pathology. As most abundant and consistent throughout the literature for aging and disease, only salient information for vascular TRP and K+ channel function has been included. Furthermore, this table does not necessarily include all approaches/experiments performed for each study, whereby some studies may have also included use of novel pharmacological agents (s-equol, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol), gene transfection, molecular expression assays, histology, and examination of other types of receptors (e.g., N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors) and ion channels (e.g., epithelial Na+ channels). Also, due their general stability with aging/disease relative to TRP and K+ channels while controversial for interrogation via various pharmacological and genetic tools (136, 137), information for potential alterations in vascular gap junction function has not been included. See Figs. 3, 4, and 5 and corresponding text for additional complementary information regarding altered functions of select GPCRs and organellar channels/pumps with aging. ACh, acetylcholine; ANG II, angiotensin II; 4-AP, 4-aminopyridine; BKCa channels, high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels; CAT, catalase; CerS2, ceramide synthase 2; ChTX, charybdotoxin; GSK1016790A, N-[(1S)-1-[[4-[(2S)-2-[[(2,4-dichlorophenyl)sulfonyl]amino]-3-hydroxy-1-oxopropyl]-1-piperazinyl]carbonyl]-3-methylbutyl]benzo[b]thiophene-2-carboxamide; [Ca2+]i, intracellular Ca2+ concentration; [Ca2+]o, extracellular Ca2+ concentration; CPA, cyclopiazonic acid, CyPPA, N-Cyclohexyl-N-[2-(3,5-dimethyl-pyrazol-1-yl)-6-methyl-4-pyrimidinamine; diC16-PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate diC16; 1-EBIO, 1-ethyl-2-benzimidazolinone; GPX1, glutathione peroxidase 1; hAPP, human amyloid precursor protein; HC-067047, 2-methyl-1-[3-(4-morpholinyl)propyl]-5-phenyl-N-[3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxamide; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; IbTX, iberiotoxin; IKCa channels, intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels; IPAH, idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; KO, knockout; l-NAME, NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride; [K+]o, extracellular K+ concentration; KATP channels, ATP-sensitive K+ channels; KIR channels, inward-rectifying K+ channels; KATP channels, ATP-sensitive K+ channels; K2P channels, two-pore domain K+ channels; Kv channels, voltage-gated K+ channels; mCAT mouse, mitochondrial catalase overexpressing mouse; ML133, N-[(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-1-naphthalenemethanamine hydrochloride; NS1619, 1,3-dihydro-1-[2-hydroxy-5-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-5-(trifluoromethyl)-2H-benzimidazol-2-one; SKF96365, 1-[2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxy]ethyl-1H-imidazole hydrochloride; NS309, 6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione 3-oxime; ONO-RS-082, 4-chloro-2-[[(2E)-1-oxo-3-(4-pentylphenyl)-2-propen-1-yl]amino]-benzoic acid; SKF96365, 1-[2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxy]ethyl-1H-imidazole hydrochloride; SKCa channels, small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels; SLIGRL, Ser-Leu-Ile-Gly-Arg-Leu-NH2; SOD, superoxide dismutase; STZ, streptozotocin; TEA, tetraethylammonium; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β1; TRAM-34, 1-[(2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazole; TRP channels, transient receptor potential channels; TRPV channels, TRP vanilloid channels; UCL-1684, 6,12,19,20,25,26-hexahydro-5,27:13,18:21,24-trietheno-11,7-metheno-7H-dibenzo [b,n] [1,5,12,16]tetraazacyclotricosine-5,13-diium dibromide; ΔVm, change in membrane potential.

Figure 5.

Novel perivascular nerve interactions to influence Ca2+ and K+ channel activity during aging. A role for afferent (sensory) nerve-signaling mechanisms has recently emerged during aging as a vasodilatory counterbalance to sympathetic (vasoconstrictive) input (209, 211) (see main text). A diminishment in sensory nerve density and signaling [via calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and its receptor] occurs in tandem with enhanced sympathetic activity [via α1-adrenergic receptor (α1AR)]. Consequently, smooth muscle cell (SMC), Ca2+ “waves” dominate versus “spark” events and thereby enhance cross-bridge interaction of actin and myosin fibers for constriction while inhibiting SMC hyperpolarization via high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa). As shown in mesenteric arteries, myoendothelial coupling is reduced during old age as well, potentially precluding the vasodilatory influence of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors (CGRPRs) on endothelial cells (ECs) via activated K+ channels (KATP, SKCa, and IKCa). Although not as well known in the context of aging and competition with sympathetic nerves, note that substance P and its receptor are also important for mediating perivascular sensory nerve signals particularly via KCa channels and nitric oxide (NO) production. Images were created with a licensed version of Biorender.com.

Brain

Aside from the heart itself, the brain is a highly demanding organ as it commands a constant ∼20% of the body’s cardiac output and oxygen delivery, albeit only ∼2% of the total body weight (140). As young adults (∼20–40 yr), 21% of the cardiac output is allocated to the brain in female subjects versus 15% for males (141). With advancing age, this cerebral blood flow-to-cardiac output ratio decreases linearly by ∼1.7% in females versus ∼0.9% in males per decade of life throughout middle (mid-40s to early 60s) and old (mid-60s to 80 yr) age and is associated with decreases in cerebral blood flow despite a stable cardiac output (141). Remarkably, the pattern of decrease in EC KIR2 channel function in posterior cerebral arteries of aging C57BL/6N mice follows this general trend (94). As expressed on both SMC and EC layers (95, 142), KIR2 channels are indeed integral to cerebral blood flow control at rest and during functional hyperemia (73, 143). Note that EC KIR2 channels are highly sensitive to membrane levels of lipids, including phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) (111) and cholesterol (144) as demonstrated in cerebral vessels of animal models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). PIP2 degrades into IP3 and diacylglycerol following activation of Gq protein-coupled receptors and is known to facilitate KIR2 activity (145, 146), whereas cholesterol mediates KIR2 inactivation (146, 147). Loss of cholesterol homeostasis, in particular, is known to underlie atherosclerosis during aging (148). A consequence of reduced EC KIR2 channel function is impaired vasodilation, either initiated at capillaries (conducted to arterioles) or directly at the arteriolar level (73). Consequently, impaired blood flow distribution throughout cerebrovascular resistance networks during metabolic demand leaves active cell types of the parenchyma (e.g., neurons, astrocytes) at risk of aberrant excitability or death. Evidence shows that exogenous PIP2 (111) or methyl-β-cyclodextrin (144) restores EC KIR2 channel function of brain capillaries and arteries, respectively, in mouse models of AD. Furthermore, oxidative stress and inflammation associated with AD pathology also impair cerebrovascular KIR2 channels and can be targeted using catalase and indomethacin, respectively (113). How combination interventions for dyslipidemia, oxidative stress, and inflammation can be modulated to stabilize KIR2 channel activity and cerebral blood flow control with aging and dementia is a topic of future investigation.

Prior literature reviews have highlighted the role of vascular TRP channels during health (149) and age-related vascular cognitive impairment and dementia (150). TRP channels are not cation-selective, whereby Ca2+ and/or Na+ can enter cells to influence vasoreactivity via activation of K+ channels and direct Vm depolarization, respectively. In general, SMC TRP currents are higher in the middle cerebral arteries of old versus young male mice (107). In response to H2O2 as a primary signaling molecular of vascular aging, the vulnerability of SMCs in posterior cerebral arteries of male mice may center on TRPC3-containing channels in particular, an effect that is mitigated via myoendothelial coupling with ECs (151). In posterior cerebral ECs, TRP-induced Ca2+ influx in response to Vm hyperpolarization progressively increases and decreases with aging in males and females, respectively (94). This sensitization of Ca2+ entry to Vm hyperpolarization is prominent in male AD mice as well, whereas it is relatively stable among both Pre-AD and AD conditions in females (109). Additional studies have underscored the importance of TRPV4 channels during the dilation of cerebral parenchymal arterioles and maintenance of cognitive function (152). Angiotensin II-induced hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg) diminishes TRPV4 channel function in cerebral parenchymal arterioles of young male C57BL/6 mice, whereas females maintain TRPV4 channel function regardless of hypertension (108). Also, during conditions of cerebrovascular amyloidosis and inflammation, impaired EC TRPV4 channel has been observed in posterior cerebral arteries among male and female mice combined (112). Note that although PIP2 supports KIR2 channel function (145), it can also inhibit TRPV4 channel function in capillary ECs and thereby support capillary-to-arteriole signaling to coordinate cerebral perfusion (80). Thus, biological sex, vascular segment (capillaries, arterioles, arteries), local versus conducted vascular signaling, and severity of pathology associated with aging are important factors to bear in mind for experimental design and development of treatment strategies. Altogether, at least in males, Ca2+ overload through heightened vascular TRP channel activity in the brain may impair neurovascular coupling and blood-brain barrier integrity (150).

In the brain, KCa channels appear to be minimally impacted relative to KIR2 and TRP channels. In male cerebral arteries (94), the underlying components of EDH signaling (i.e., increased [Ca2+]i and SKCa and IKCa channel function) may be enhanced in old age (≥24 mo) because of increased levels and basal activity of H2O2. Indeed, Vm hyperpolarization of posterior cerebral ECs to a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50, ≈1 µM) of the potent SKCa and IKCa channel opener 6,7-dichloro-1H-indole-2,3-dione-3-oxime (NS309) in old mitochondrial catalase-overexpressing (mCAT) mice was reduced by ∼30% relative to old wild-type mice (94). Also, note that EDH is decreased in posterior cerebral arteries of old females relative to young females and old males (94). Note that for conditions of AD versus healthy controls, EDH is enhanced in males, whereas relatively stable in females (109, 110). As consistent with EC SKCa and IKCa channels, SMC BKCa channel function is decreased in females but increased in males in middle cerebral arteries of old rats as well (106). Although, BKCa channel function may be less sensitive in the middle cerebral arteries of old versus young male rats following pharmacological modulation of certain GPCRs, such as in the case of isoproterenol activation of β-adrenergic receptors and phosphorylation of BKCa channels via protein kinase A (PKA) (153). For overall EDH signaling in the brain, females appear to favor GqPCR (purinergic) signaling versus K+ channel function for males during aging (94) and conditions of AD (109). As a widespread appreciation for neurovascular support of healthy cognition continues to emerge (154, 155), additional work will further illuminate the myoendothelial interactions of cerebral blood vessels in the aging brain.

Eye

Age-related diseases associated with the impaired vascular health of the eye include glaucoma (156) and diabetic retinopathy (157). In addition, retinal imaging has also been developed as a noninvasive method for monitoring the development of a major cognitive disorder such as Alzheimer’s disease (158, 159). A multitude of studies have focused on enhanced proliferation and migration of ECs via vascular endothelial growth factor (160, 161) and inflammatory signaling itself regarding the arrangement of vascular receptors and ion channels and how they alter with aging. It is known that retinal arterioles contain the standard voltage-gated K+ (e.g., BKCa) and Cl− [e.g., Ca2+-activated Cl− (ClCa)] channels (162) and VGCCs (T-type, CaV3.1) (163) for myogenic autoregulation. With respect to differences among vascular segments, capillaries and arterioles of the eye are enriched in ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels and VGCCs, respectively (164, 165). With going in the direction from retinal arterioles (containing ECs and SMCs) to distal capillaries (ECs and pericytes) of pressurized whole retinas ex vivo, elegant electrophysiology measurements demonstrate progressively declining participation of VGCCs and slowing constriction speed to increasing pressure (20–100 mmHg) at the ophthalmic artery inlet (165). Other studies have highlighted how various TRP family members (canonical, melanostatin, mucolipin, and vanilloid) are expressed among the corneal epithelium, lens, ciliary body, trabecular meshwork, and retina of the eye (reviewed in Ref. 166). In particular, Ca2+-permeant TRPV channels (e.g., TRPV2, TRPV4) govern vascular autoregulation of retinal arterioles (166, 167), whereby loss in TRP channel function generally underlies diabetic neuropathy (114, 166). A deficiency in caveolin-1 as a key regulator of intravascular pressure-induced myogenic tone (168) accelerates age-related loss of contractile SMCs of retinal arterioles (169). Furthermore, per conditions of central serous chorioretinopathy, aldosterone will activate mineralocorticoid receptors to upregulate choroid EC SKCa (KCa2.3) channel expression and thereby cause excessive vascular dilation and leak underneath the retina (170).

Electrotonic mapping of retinal arterioles and capillaries demonstrated that decay in axially spreading changes in Vm (depolarization) occur at ∼5% per 100 μm of vascular distance along capillaries, tertiary arterioles and secondary arterioles (171). This calculation matches well with the decay rate observed for the endothelium of skeletal muscle (superior epigastric) arteries as ∼4.4% per 100 μm (172). In the presence of angiotensin II as a key indicator of vascular aging and hypertension (173), this decay along the retinal microcirculation increases 10-fold from ∼5% to ∼50% decay per 100 μm (171), likely because of an impairment in axial EC-to-EC transmission of charge and not local EC-to-SMC coupling or SMC-to-SMC conduction (164). Note that these studies were performed using acute applications of angiotensin II (500 nM; ∼5-min exposure) in microvasculature isolated from young rats, whereby detectable changes in membrane resistance (Rm) were not observed using hyperpolarization pulses (20 mV) via the perforated-patch configuration of intact vessels (171). Instead of a profound alteration in plasma membrane ion channel activity to influence Rm, a potential difference in connexin (Cx) composition among endothelial and myoendothelial junctions and their respective sensitivity to angiotensin II treatment has been speculated for these findings (164). Exploring this possibility has been complicated by the controversial nature of pharmacological and genetic tools intended to interrogate gap junctions (136, 137). The vascular biophysics underlying coordination of blood flow throughout the eye during youth, healthy aging, and pathogenesis require further investigation. In addition, the eye as an extension of the brain and CNS may have prognosticative value for development of neurodegenerative disease (174), further reinforcing its importance for diagnosing and treating dementia in addition to impairment in sight.

Skeletal Muscle

The impact of aging on skeletal muscle arteries has been described in detail throughout prior reviews (17–19). In brief, skeletal muscle arteries contain robust EDH signaling whereby classic M3R stimulation with ACh evokes a “peak” Δ[Ca2+]i response (IP3 binds to IP3R and release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum) that is followed by a secondary “plateau” Δ[Ca2+]i phase (Ca2+ influx through TRPs) (17). In tandem, SKCa and IKCa channels are activated and hyperpolarization is present and proportional to the elevated [Ca2+]i signal during exposure to ACh (17). In males, the “peak” Δ[Ca2+]i response is maintained during old age but the TRP channel contribution during the “plateau” phase is elevated (33). Because of heightened H2O2 signaling, basal activity of SKCa and IKCa channels is elevated during old age whereby EC conduction of both hyperpolarization and depolarization through gap junctions is impaired [(115); Fig. 4]. In turn, robust Vm hyperpolarization to H2O2 (200 µM, 20 min) has been demonstrated in an SKCa and IKCa channel-dependent manner, whereby electrical conduction was abolished (115) similar to what is observed during a maximal concentration (10 µM) of the SKCa and IKCa channel opener NS309 (172). Remarkably, prolonged treatment of superior epigastric arteries with H2O2 (200 µM, 50 min) evokes less cell death in old versus young animals whereby ECs are more resilient than SMCs (175). Follow-up studies have revealed that vascular cells of females are significantly more protected against H2O2 than vascular cells of males, whereby interleukin-10 (IL-10) and a caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway mediate cell death (176).

General increases in SMC K+ channel function occur in male skeletal muscle arteries (96, 102) and arterioles (116) during advanced age as well. Enhanced BKCa (102) and KIR2 channel (96) function has been observed in superior epigastric arteries of old versus young animals. With regard to muscle fiber during old age (177), both BKCa and voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channel activities oppose myogenic tone in arterioles of soleus as an oxidative, slow-twitch muscle type with a high mitochondrial content (116). With a negligible contribution of BKCa channels in both young and old animals, arteriolar myogenic tone within the gastrocnemius (glycolytic, fast twitch) is predominantly regulated by KV channels during old age (116).

Note that enhanced KCa function is also present in skeletal muscle arteries during obesity (117) and that impaired conducted hyperpolarization and vasodilator signals occur during conditions of hypertension (178) and hyperhomocysteinemia (179). Also, in response to chronic hypobaric hypoxia (380 Torr; 48 h), the expression of BKCa emerges in ECs with microdomains formed among caveolin-1, TRPV4, and BKCa channels in male rat gracilis arteries (180). With relevance to sarcopenia and osteoporosis with advancing age, uncoupling of eNOS and higher levels of ONOO− have also been found in old versus young male rats in tandem with elevated superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1), and NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) (181).

Heart

The myocardium of the heart extracts ∼70–80% of the oxygen contained within coronary blood flow (182). Similar to skeletal muscle, many of the same trends are observed with coronary arteries or aorta during aging (119) or chronic disease such as obesity (120) and diabetes (121) as generally elevated KCa channel function in the face of decreased NO signaling coupled with an impairment in conducted vasodilation via gap junctions (118). In addition, fundamental work and insight has emerged for the interaction among KIR and KATP channels in capillaries among pericytes and ECs as primary “electrometabolic” sensors of blood flow regulation (see Ref. 183 for a comparative analysis among the heart and brain). In addition, other groups are actively researching mineralocorticoid receptor signaling and EC Na+ channels per their contribution to cardiovascular fibrosis and arterial stiffness with aging and insulin resistance (184).

Lung

As recently reviewed in detail (185), numerous receptor and ion channel components govern the tone of pulmonary arteries as they receive the entire cardiac output of deoxygenated blood from the heart’s right ventricle in a high-flow, low-resistance system with a mean pressure of ∼14 mmHg (reference: ∼100 mmHg for systemic arteries). This arrangement is appropriate for the purpose of the lungs to extract oxygen from the environment via alveoli and replenish oxygen within the pulmonary circulation to be returned to the left atrium of the heart via the pulmonary veins. As a factor to consider for potential dysregulation of blood pH (e.g., acidosis), the lungs normally remove excess carbon dioxide carried within the entryway of the pulmonary circulation back out into the environment. In such manner, the pulmonary vasculature is especially sensitive to mechanical stretch and shear stress of EC membranes that then transmit intracellular signals to command movement of SMCs to influence vasoreactivity of the entire vascular wall.

Pulmonary arteries contain primary receptor and ion channel components such as TRPV4 (186), SKCa and IKCa channels (187), and Cx40 (188) for EDH. However, in contrast, to mesenteric arteries, for example, TRPV4 channel signaling in pulmonary arteries favors coupling with eNOS and NO production in a negative feedback loop manner versus SKCa and IKCa channel activation (186). Pulmonary EC TRPV4 channels are generally colocalized with eNOS while containing negligible levels of hemoglobin α (Hbα; NO scavenger) at myoendothelial gap junctions (189). However, with challenges of decreased EC NO levels and NO-mediated dilation, pharmacological activators of SKCa and IKCa channels may still be used to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH; mean pressure > 20 mmHg) (187). Not surprisingly, mechanosensitive TRPC6 and PIEZO1 channels in arterial ECs have also emerged as primary contributors to Ca2+ influx and associated increases in [Ca2+]i (190). Chronically elevated EC (191) and SMC (192) PIEZO1 channel function in particular contributes to Ca2+-induced cell proliferation that is representative of the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. As PIEZO1 channels are also permeant to Na+ (193), prolonged depolarization and vascular constriction will accompany such structural remodeling as well.

Impaired function of various SMC K+ channels susceptible to hypoxia such as KV1.5 (124, 194), BKCa (122, 123, 195), KATP (196, 197), and two-pore domain K+ (K2P) (198, 199) accompanies and/or exacerbates PAH. One molecular mechanism entails a high expression of microRNAs that negatively regulate KCNA5 (KV1.5 mRNA) and KCNMB1 (BKCa β1 subunit mRNA) as miR-29b, miR-138, and miR-222 (200). Loss-of-function mutations of ABCC8 [KATP sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1) subunit] (125) or enhanced endothelin signaling (201) can directly counteract normal KATP channel expression and function, respectively. Outwardly rectifying K2P channels are pH sensitive and set K+ background currents in pulmonary arteries (reviewed in Ref. 138), whereby their loss of function leads to pulmonary vasoconstriction and PAH (126), because of a depolarized resting Vm of SMCs and activation of L-type VGCCs (202). Another novel therapeutic target of PAH responsible for SMC depolarization includes a ClCa channel as TMEM16A as a plasma membrane gateway for the efflux of Cl− ions (139). Downregulation in an EC gap junction component as Cx40 in response to chronic hypoxia (10% O2; 4 wk) relative to normoxia (21% O2) also contributes to PAH via a decline in the spread of ACh-induced EDH (188). Note that gap junctions containing Cx40 are instrumental or conducted depolarization and vasoconstriction in response to acute hypoxia (1% O2; 10 min) as well (203), underscoring the dichotomous role of EC-to-EC coupling for modulating pulmonary vascular resistance throughout health and disease. Note that in the case of endothelin exposure and Ca2+ activation of rho kinase [i.e., Ca2+ “sensitization” for myosin light-chain phosphatase inhibition (204)], Vm depolarization is not necessarily required for vasoconstriction in response to chronic hypoxia (205).

Finally, general features of perivascular innervation of the pulmonary vasculature as sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory are known across several species including rodents and humans (reviewed in Ref. 206). However, as is the case with other organs, there is a paucity of knowledge as to how various nerves and their receptors interact to sculpt exchange of electrical signals and second messengers among pulmonary artery ECs and SMCs (Fig. 5). A foundational study has carefully separated examination of SMCs and ECs to reveal that sensory nerve signaling via CGRP receptors and KATP channels are present on both cell layers of male and female mouse pulmonary arteries (207). Progressive concentrations of CGRP (100 pM to 1 µM) evoke up to ∼20-mV hyperpolarization in a like manner for both SMCs and ECs that is dependent on PKA and activation of KATP channels (207). Referring back to the central importance of KATP channels for pulmonary blood flow during health and PAH (125, 201), such studies will expand considerations for the depth of integrative vascular signaling and the therapeutic toolbox accordingly. Unfortunately, how biological sex and aging influence receptor and ion channel function in the pulmonary vessels is altogether unknown, and thus, studies are desperately needed in this area of research.

Mesentery

In the mesentery, an accumulated body of novel research has revealed competing contributions of sympathetic versus sensory perivascular nerves during aging in the context of SMC and EC ion channels, Ca2+ signaling, and myoendothelial coupling (208–212) (Fig. 5). Overall, note that the density and function of perivascular nerves are diminished with advancing age in mesenteric arteries (211, 212). Sympathetic nerves release norepinephrine and activate αARs, and with treatment of phenylephrine as a selective α1AR agonist, the potency of αAR activation has been shown to diminish with old age (211). Sensory nerves release respective transmitters as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) (44). There are differential effects of respective agents among ECs and SMCs. Substance P hyperpolarizes both ECs and SMCs via KCa channels while also involving endothelium-derived NO signaling for the relaxation of smooth muscle (208). In response to CGRP, SMC and EC hyperpolarization require KATP and KCa channels, respectively (208). Note that vasodilation to CGRP is diminished with old age in male rodents (212), whereby myoendothelial coupling among SMCs and ECs is substantially reduced (210). Furthermore, sympathetic induction of SMC Ca2+ events is also unbalanced for local Ca2+ “sparks” that underlie vasodilation versus global intracellular Ca2+ “waves” producing vasoconstriction (209). Altogether, these data highlight an example of the interaction of vasodilatory (sensory) and vasoconstrictor (sympathetic) perivascular nerve pathways to regulate blood flow and how this balance is impacted with aging.

In contrast to dominant NO signaling in pulmonary arteries, TRPV4 channels of mesenteric ECs favor activation of SKCa and IKCa channels (186) with the additional presence of NO-scavenging Hbα at myoendothelial gap junctions (189). As consistent with other organs during aging, KCa channel function is generally increased during chronic disease conditions such as hypertension (128, 129) and diabetes (130). Furthermore, with local EDH unaffected, conducted hyperpolarization/vasodilation to the peptide SLIGRL (selective protease-activated receptor agonist) along mesenteric arteries is impaired during chronic hyperglycemia [(131); 40 mM glucose, nonfasting blood glucose level in young diabetic db/db mice lacking functional leptin receptors) as likely influenced by SMC BKCa and KV channel activity (213). The function of L-type VGCCs is preserved (214), whereby SMC TRP currents are generally higher (127) during old versus young age. The coupling of SMC T-type VGCCs and RyRs may also alter with advancing age to influence EC function (215, 216). In contrast to the microcirculation of the eye (171), angiotensin II infusion (4 ng/min; raised mean arterial blood pressure by 6 ± 2 mmHg) enhances conducted, but not local, vasoconstriction to local norepinephrine or electrical stimulation treatments in rat mesenteric arterioles in vivo (217). This finding is most consistent with a broad downregulation of the expression and/or function of various SMC K+ channels (e.g., KV, KIR, and BKCa) in response to angiotensin II and an increased SMC Rm (reviewed in Ref. 218). Note that local vasoreactivity is sustained during angiotensin II in mesenteric arterioles (217) as similar to the eye (171). The differential effects of angiotensin II on Rm and/or axial resistance (Ra) among vascular types to shape an overall decline or enhancement in conducted electrical signals along and between respective SMC and EC layers requires further examination. With a large, informative body of work constructed for the gut microcirculation nonetheless (77), additional studies are also needed in the context of aging, biological sex, and the emerging gut-brain axis research field (219) for investigation.

Kidney

Similar to the brain, the kidney occupies only ∼1% of the total body weight and receives a constant ∼20% of the cardiac output to maintain renal perfusion and the blood-urine filtration interface for elimination of excess metabolites (e.g., NH4+, H+; via glomerular filtration and tubular excretion) while retaining nutritive glucose, amino acids, and ions (e.g., HCO3−; via tubular reabsorption and venous return) for maintaining overall fluid and electrolyte homeostasis (220). The anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of the renal microcirculation have been covered in depth elsewhere (reviewed in Refs. 221, 222) but, in brief, afferent arterioles branching off of the interlobular artery feed into glomeruli and regulate glomerular hydrostatic pressure and filtration. During healthy conditions, there is autoregulatory cross talk among the inherent myogenic reactivity of the afferent arterioles and changes in Na+, K+, and Cl− sensed by Na+:2Cl−:K+ cotransporters on macula densa cells of the thick ascending limb and distal convoluted tubule junction (i.e., “tubuloglomerular feedback”) to ultimately determine an optimal glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (223). For example, an increased NaCl concentration detected by the macula densa will evoke acute constriction of the afferent arteriole and a brief decrease in GFR. Chronic disruptions in the autoregulation of afferent arteriolar tone as sustained vasodilation or vasoconstriction underly the progression of nephropathy and the development of systemic hypertension and diabetes (224). Furthermore, the convergence of systemic and intrarenal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone signaling, sympathetic and sensory nerves, and intravascular fluid-shear forces detected by primary cilia also shape vascular tone among afferent and efferent arterioles of the pre- and postglomerular apparatus, respectively (222).

As a result of limited accessibility to the blood microcirculation contained within the renal parenchyma (221), information for mechanisms of vascular cell-specific receptor and ion channel function of the kidney is relatively scarce among conditions of both health and disease (virtually nothing for aging). Starting with the interlobar arteries of male and female mice, it is known that a functional EDH mechanism is present with the inclusion of SKCa/IKCa and KIR channels, Na+/K+-ATPases, and patent myoendothelial gap junctions that contain Cx40 (225). The presence of Cx40 is crucial for transmission of the tubuloglomerular response in afferent arterioles (226). Furthermore, EDH signaling via SKCa/IKCa function also appears to be present in afferent but not in efferent arterioles (227), pointing to distinct differences in EC ion channel function in the pre- versus postglomerular apparatus. Remarkably, both arterioles contain functional KIR2.1 channels, whereby stimulating KIR2 currents enough to evoke ∼10 mV of hyperpolarization has a negligible effect on vascular diameter in efferent versus >5 µm vasodilation in afferent arterioles preconstricted with angiotensin II (228). Thus, note that, even with a known similarity in K+ channel expression/function, the close coupling of electrical responses (changes in Vm) with mechanical vasodilation and vasoconstriction is indeed a consistent feature of afferent but not efferent arterioles (229). As determined by renal blood flow measurements in vivo and/or isolated interlobar arteries ex vivo, SKCa/IKCa function is maintained throughout conditions of both hypertension (132) and diabetes (133), whereas NO-dependent dilation is impaired. Additional studies using an in vitro blood-perfused juxtamedullary nephron technique have demonstrated a threefold higher contribution of KIR channels [sensitive to BaCl2 and/or tertiapin-Q (KIR1.1, KIR2.1, KIR3.x)] to vasodilation of afferent arterioles in male diabetic versus nondiabetic rats (134, 230). With current priorities centered on renin-angiotensin, oxidative, and sympathetic nerve signaling (221, 222, 224), a focus on diseases of chronic aging and biological sex will pave an exciting future for new mechanisms and therapy surrounding renal pathophysiology.

Skin

Due to their noninvasive nature, skin blood flow studies are common for assessing the vascular function of human subjects. For cutaneous vasodilation, old age augments and attenuates purinergic receptor function in human females (231) and males (232), respectively, with no apparent effect on muscarinic receptors. As consistent with the observation of increased EDH throughout organ systems in rodents, general K+ channel-dependent EC function is enhanced in older (∼65 yr) versus younger (∼25 yr) mixed male and female human subject cohorts (14). Furthermore, EDH also compensates for reduced NO activity during diabetic conditions in the subcutaneous arteries of humans (135). Note that novel vascular agents such as menthol (putative opener of Ca2+-permeant TRPM8 channels; theoretically stimulates both EDH and NO signaling) are being explored as therapeutic agents in randomized controlled trials of human subjects (233–235). The capacity for cutaneous vasodilation by menthol in particular is preserved across conditions of normotension and hypertension in both men and women (15).

VASCULAR AGING STUDIES: CONSIDERATIONS FOR GENERAL FEASIBILITY, ROLE OF BIOLOGICAL SEX, CELL REGRESSION VERSUS PROLIFERATION, GENE PROFILE ANALYSES, AND DATA INTERPRETATION

Biological aging has been recognized as the most prominent risk factor for the development of major chronic disorders as cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and cancer (236). However, there are significant logistical limitations to consider for a research environment that is preparing for, or conducting, aging studies. There is a time and husbandry issue concerning the experimental animals themselves, by which investigators may or may not be able to procure animals at approximate ages throughout the animal’s lifespan upon demand. Typically (and with permission of agencies such as the National Institute on Aging) only wild-type animals of the C57BL6 and Fischer 344 lineages have been available for purchase in an “as needed” basis. Most to all other animal types suitable for studying cardiovascular disease will require breeding and local housing at the investigator’s institution for up to 2 years or longer (24). Consequently, because of availability of animal study models at any one time, aging research may encounter problems of diminished scientific rigor while limited to “observational” or “phenomenology” studies that lack critical mechanistic insight. Thus, at least with respect to mammalian models, biology of aging investigators must be more encompassing with their efforts for fundamental studies using young, healthy animals and dedicated models of disease as well. In the aggregate, perhaps the strongest experimental design for understanding cardiovascular disease is indeed one that examines models of poor, normal, and optimal aging models in parallel. In turn, the investigator increases their chances of capturing subtle mechanistic transitions from physiology to pathology. Accordingly, the scope and timing of preparing individual manuscripts for peer review must be decided carefully and in a highly organized manner as well.

Studies focused on the role of biological sex have been a persistent problem with what was once determined in 2009 as ∼70% of studies focused on a single sex or were unspecified (237). As of the most recent meta-analysis in 2019, this overarching number has decreased to ∼50% (238) but progress or improvements in this regard depend on interpretation concerning discipline while addressing the greatest need for data collection among females in particular. For example, there has been a specified increase in the inclusion of both sexes among studies in physiology (from 13 to 36%) but the use of males only remained the same (51% throughout), whereas the percentage of female-only studies actually decreased (14 to 4%) within that time frame (238). As a much more dire outcome, the field of pharmacology has shown an overall decrease in studies specifying inclusion of both sexes (from 33 to 29%), with an increase in male only (from 50 to 58%) and stability of a low participation (10% throughout) in female-only research (238). Thus, sex as a biological variable and inclusion of females remains a primary priority for improvement among biomedical research. However, with referring to a key limitation of aging research (availability across multiple time points throughout the animal’s lifespan), this consideration effectively doubles the number of animals required relative to the majority of prior efforts and can thereby constrain financial and logistical resources further.