Abstract

Abstract

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) caused by porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), is an acute and highly infectious disease, resulting in substantial economic losses in the pig industry. Given that PEDV primarily infects the mucosal surfaces of the intestinal tract, it is crucial to improve the mucosal immunity to prevent viral invasion. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) oral vaccines offer unique advantages and potential applications in combatting mucosal infectious diseases, making them an ideal approach for controlling PED outbreaks. However, traditional LAB oral vaccines use plasmids for exogenous protein expression and antibiotic genes as selection markers. Antibiotic genes can be diffused through transposition, transfer, or homologous recombination, resulting in the generation of drug-resistant strains. To overcome these issues, genome-editing technology has been developed to achieve gene expression in LAB genomes. In this study, we used the CRISPR-NCas9 system to integrate the PEDV S1 gene into the genome of alanine racemase-deficient Lactobacillus paracasei △Alr HLJ-27 (L. paracasei △Alr HLJ-27) at the thymidylate synthase (thyA) site, generating a strain, S1/△Alr HLJ-27. We conducted immunization assays in mice and piglets to evaluate the level of immune response and evaluated its protective effect against PEDV through challenge tests in piglets. Oral administration of the strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 in mice and piglets elicited mucosal, humoral, and cellular immune responses. The strain also exhibited a certain level of resistance against PEDV infection in piglets. These results demonstrate the potential of S1/△Alr HLJ-27 as an oral vaccine candidate for PEDV control.

Key points

• A strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 was constructed as the candidate for an oral vaccine.

• Immunogenicity response and challenge test was carried out to analyze the ability of the strain.

• The strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 could provide protection for piglets to a certain extent.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas9, Lactic acid bacteria, Genome expression, PEDV S1 gene, Oral vaccine

Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) is an intestinal infectious disease caused by the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV). It is characterized by vomiting, severe diarrhea, and high mortality in piglets (Sun et al. 2019). The PEDV S protein is the main envelope glycoprotein of PEDV and is composed of S1 and S2 domains. The S1 gene enables viral particles to invade the body and stimulate immune cells to produce neutralizing antibodies; therefore, it is an excellent antigen candidate for vaccine production (Sun et al. 2021). Several studies have used the S1 gene to develop vaccines against PEDV, with promising results (Wen et al. 2018; Egelkrout et al. 2020). PEDV primarily invades mucosal surfaces, especially the intestinal mucosal epithelial surfaces; thus, it is crucial to develop an oral mucosal vaccine that can induce effective mucosal immune responses (Zhang et al. 2017). Many studies have used lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as delivery vectors to produce oral mucosal vaccines against intestinal pathogens, owing to their safety, absence of side effects, and non-specific immune adjuvant effects. Furthermore, LAB have many advantages, such as enhancing the non-specific immune ability of the body, regulating the immune response by stimulating cytokine synthesis, reducing inflammatory response signals, regulating dendritic cell functions, and regulating secreted levels of SIgA (Hartanti 2010, Wang et al. 2016, Zhang et al. 2017). Among the LAB, Lactobacillus paracasei (L. paracasei) has great potential as an antigen delivery host. Studies have shown that L. paracasei can persist in intestinal and vaginal tissues, as well as reduce the presence of pathogenic Escherichia coli and Shigella in the human intestinal microflora (Zampieri et al. 2012). Muhammed et al. utilized L. paracasei (DUP-13076; LP), Lactobacillus rhamnosus (nrrlb442; LR), and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (NRRLB548; LD) to immunize chickens, and the results showed that all three strains could be well colonized in chickens, effectively reducing the adhesion and invasion ability of Salmonella in intestines and reduce the expression of Salmonella virulence genes (Muyyarikkandy et al. 2017). Zeng et al. used L. paracasei as oral carrier to deliver exendin-4 peptide and successfully realized the secretion expression of foreign protein, replacing expensive chemical synthesis and inconvenient injection administration (Zeng et al. 2016).

LAB employ plasmids as a medium to deliver foreign antigens and use antibiotic genes as selective markers (Wang et al. 2019). However, there are many defects associated with the plasmid expression system. The presence of antibiotic genes can be diffused through transposition, transfer, or homologous recombination during operation and use, resulting in the emergence of drug-resistant strains (Whittle et al. 2002). Replication of the plasmid via the rolling circle mechanism leads to the appearance of an unstable single-chain intermediate in the middle link, leading to deletions in the genetic process (Douglas and Klaenhammer 2011; Evdokimova et al. 2019). Although high copy number plasmids might offer certain advantages for antigen expression, plasmid instability and the antibiotic selective pressure make their application in animals challenging (Song et al. 2014b; Zhao et al. 2020). Researchers have shifted their focus to the LAB genome (Russell and Klaenhammer 2001; Yang et al. 2015). Integrating genes into chromosomes through gene-editing technology for expression is expected to eliminate the use of antibiotic markers and guarantee the stable inheritance of foreign genes.

As research progresses, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) sequences, an adaptive immune response, have been effectively developed as a gene-editing technology to facilitate convenient and rapid genome manipulation processes (Seo et al. 2023). Researchers have successfully utilized the CRISPR/Cas system to knock out and insert genes in a variety of animals and bacteria (Agarwal and Gupta 2021). However, there have been limited studies on the application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system on LAB. This system cuts the genome to induce double-stranded DNA breaks (DSB), but it has been observed to exhibit high lethality in some bacteria (Ran et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2015). Therefore, gene knockout and insertion operations in the genome of LAB still rely on the classical homologous recombination and double-crossover strategy, which is rather laborious and time-consuming (Biswas et al. 1993, Song et al. 2014a, 2014b). Recently, researchers have optimized the CRISPR/Cas9 system to successfully perform genetic manipulation in LAB. In 2014, Oh et al. combined the CRISPR/Cas9 system with ssDNA recombination to successfully edit the genome of Lactobacillus reuteri (Oh and van Pijkeren 2014). Guo et al. utilized an ssDNA recombineering technique with a modified CRISPR-Cas9 counterselection to successfully knock out the UPP gene in Lactococcus lactis (Guo et al. 2019). Song et al. applied an optimized CRISPR-NCas9 system to cut single DNA strands to overcome bacterial cell death caused by DNA double-strand breaks (Song et al. 2017).

In the study, we used the CRISPR-NCas9 system to construct the gene-editing plasmid pLCNICK-S1, which was employed to generate an alanine-deficient L. paracasei S1/△Alr HLJ-27 expressing the PEDV S1 gene in the genome of L. paracasei △Alr HLJ-27. Immunogenicity upon administration was analyzed based on the levels of anti-PEDV IgG and mucosal IgA antibody responses in mice and piglets. Additionally, a challenge test was performed to further explore the immune protection provided by the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 strain in piglets.

Materials and methods

Strains, plasmids, and virus

Auxotrophic L. paracasei △Alr HLJ-27 was constructed (Li et al. 2022) based on the wild strain HLJ-27, isolated from the intestine of large landrace piglets and cultured in de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth supplemented with an additional 200 μg/mL d-alanine for stationary culture. The stability of this strain was evaluated, and then subjected to the expression of the VP4 gene in a previous study (Li et al. 2022). The homology of the alr and thyA gene was more than 99% with the engineered strain L. paracasei W56. The plasmid pLCNICK (Song et al. 2017), including the thermosensitive replicon, NCas 9 protein, and sgRNA sequence, was generously provided by Yang Sheng (a researcher at the Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences). Plasmids pMD-19Ts-P776 (Yin et al. 2016), pMD-19Ts-RBS, and pMD-19Ts-S1 (Xiao et al. 2022) were preserved in our laboratory. The PEDV LJB2019 strain was isolated from clinical samples and stored at − 140 °C to maintain its virulence. This strain could be reasonably obtained from Dr. Xiaona Wang.

Construction and identification of the mutant strain S1/△AlrHLJ-27 expressing the PEDV S1 gene genomically

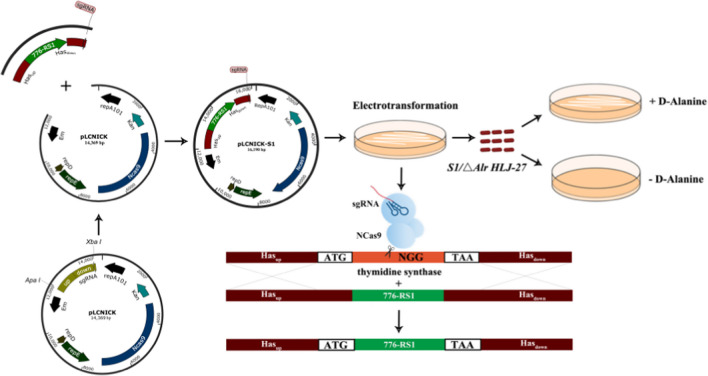

The gene-editing plasmid construction strategy is shown in Fig. 1. The genes encoding the promoters P776, RBS, and S1 (the accession number, OR496609) were amplified using the standard PCR procedure with the plasmids pMD-19Ts-P776, pMD-19Ts-RBS, and pMD-19Ts-S1 as templates, respectively. The amplified fragments were then fused into one fragment, P776-RBS-S1 (P776-RS1), in the order of P776, RBS, and S1, via fusion PCR with the homologous sequence of the primers (P776-F, S1-R). The detailed primer sequences are listed in Table 1. The fragment Hasup and Hasdown-sgRNA were obtained from the genome of L. paracasei HLJ-27 using PCR amplification (Hasup-F/R and Hasdown-sgRNA-F/R as the primers). The fragment Hasup-P776-RS1-Hasdown-sgRNA was then obtained by fusion PCR using the genes Hasup, P776-RS1, and Hasdown-sgRNA as templates (Hasup-F and Hasdown-sgRNA-R as the primers) and inserted into the vector pMD-19 T-simple, generating the plasmid pMD-19Ts-Hasup-P776-RS1-Hasdown-sgRNA (pMD-19Ts-S1). pMD-19Ts-S1 and the gene-editing framework pLCNICK were digested using Apa I and Xba I enzymes, resulting in the recombinant plasmid pLCNICK-S1 with T4 ligase ligation. Plasmids were identified through sequential analysis.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the construction of gene-editing plasmid pLCNICK-S1 and the gene-editing process CRISPR-Cas9D10A system. The gene-editing plasmid pLCNICK-S1 was constructed as showing as the steps. The fragment P776 promoter, RBS, and S1 were purified and fused into one fragment, generating the gene P776-RBS-S1 (P776-RS1); the fragment Hasup, P776-RS1, and Hasdown-sgRNA were amplified by the fusion PCR to yield the gene Hasup-P776-RS1-Hasdown-sgRNA, then ligated with the pMD19T-Simple, producing the cloning plasmid pMD19Ts-Hasup-P776-RS1-Hasdown-sgRNA (pMD19Ts-S1). The plasmid pMD19Ts-S1 was digested and then inserted into the temperature-sensitive vector pLCNICK at Apa I and Xba I sites, generating the gene-editing plasmid pLCNICK-S1. The pLCNICK-S1 was electrotransformed into competent cells △Alr HLJ-27 to initiate the gene-editing process, yielding the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 with substituting the P776-RS1 gene for thymidine synthase (thyA) at the genome, and only growing with exogenous addition of d-alanine

Table 1.

The sequence of primers

| Genes | ID | Primers sequences |

|---|---|---|

| Hasup | Hasup-F | tctttttctaaactagggcccGGATCCCATTCAGATCGCCA |

| Hasup-R | tatgcTGTCTTCTTCCCTCCAGTGGG | |

| P776 | P776-F | ggagggaagaagacaGCATATTACAAAAAAGTCCTCTGCTC |

| P776-R | tatcgtcactcctAAGGCACGTCCTTCTTTAATGG | |

| RBS | RBS-F | gtgccttAGGAGTGACGATAAAGATGAAATTAAA |

| RBS-R | agcgaagcTCCATCAGCTTTAACTGTTGTGGC | |

| S1 | S1-F | GgaTGCATTGGTTATGCTGCCAA |

| S1-R | gcttcgtCTACTTATCGTCGTCATCCTTGTAATCGTAAAAGAAACCAGGCAACT | |

| Hasdown | Hasdown-F | cgacgataagtagACGAAGCACATGCTTGGGC |

| Hasdown-R |

aaggatgatatcacctctaga

GTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC

GTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC

|

|

| thyA | thyA-F | CAAAGAAGAAAACAAAACTGAC |

| thyA-R | ACGAACTACAAATGCACATAAC | |

| pLCNICK | XA-F | CGAACCGTCTTATCTCCCAT |

| XA-R | TTGCCTTTTCCGTCCAGAGC |

Restriction enzyme recognition sites applied for cloning are shown in italics. Homologous sequence and sgRNA sequence were shown in bold and red words, respectively

To obtain the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27, △Alr HLJ-27 competent cells were prepared and electroporated according to a previously described method (Wang et al. 2018). In brief, 1 mL of bacterial liquid was inoculated into 100 mL of MRS medium, which included 1% glycine and 200 μg/mL d-alanine, for static culturing at 37 °C until the OD600 reached 0.4 to 0.8. The cells were then pre-cooled on ice for 20 min and then harvested via centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting precipitate was washed and resuspended in 2 mL of ice-cold solution II containing 10% glycerol and 17% sucrose. Aliquots of 200 μL of competent cells were prepared in individual tube and preserved at 80 °C until further use. The gene-editing plasmid pLCNICK-S1 was prepared prior to electroporation. The plasmids were gently mixed with △Alr HLJ-27 competent cells, and the mixture was transferred into a pre-cooled Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) disposable cuvette (inter-electrode distance of 0.4 cm), then subjected to a single electric pulse (2.2 V; 200 Ω; 25 µF) using the Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad). The electrotransformed strains were then cultured statically at 30 °C and identified through genome PCR using thyA-F/R as primers.

The process of genome manipulation using gene-editing plasmids in bacteria is shown in Fig. 1. To obtain the pure strain S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27, the ΔAlr HLJ-27 strain containing the editing plasmid was streaked on MRS plates supplemented with 200 μg/mL d-alanine and cultured at 37 °C for three to five generations. The edited plasmid was removed during this process. Once the purified strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 was obtained, its requirement for d-alanine was verified. The strain was then inoculated into MRS broth medium supplemented with 200 μg/mL d-alanine, or basic MRS broth medium, or streaked on MRS solid medium supplemented with 200 μg/mL d-alanine or basic MRS medium to observe its growth. To test the genetic stability of the inserted gene S1, the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 was streaked on MRS plates supplemented with 200 μg/mL d-alanine and serially passaged for 20 generations. The genome was extracted every two generations, and PCR and sequencing were used for identification. To evaluate the plasmid elimination, plasmids from the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 of both F1 and F20 generations were extracted and identified using PCR amplification with XA-F/R as primer pairs.

Detecting the expression of the S1 protein

The mutant strain S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27 was cultured overnight in MRS medium supplemented with 200 μg/mL d-alanine, and the bacterial precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 2 min. The precipitate was incubated with 1% lysozyme and sonicated for 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) detection and western blotting. SDS-PAGE was used to separate the proteins in the mixture, which were then transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Milford, MA, USA) using a mouse anti-S1 monoclonal antibody (mAb cell supernatant) prepared in our laboratory as the primary antibody (Xiao et al. 2022). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Sigma, Ronkonkoma, NY, USA) was used as the secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:5000. The results were evaluated using a chemiluminescent substrate reagent (Thermo Scientific, Durham, NC, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To determine the stability of S1 gene expression in the mutant strain S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27, protein samples for the western blot assay were obtained with every five generations of the strain within 20 generations. The strain ΔAlr HLJ-27 was used as a negative control.

Oral immunization procedure and sample collection

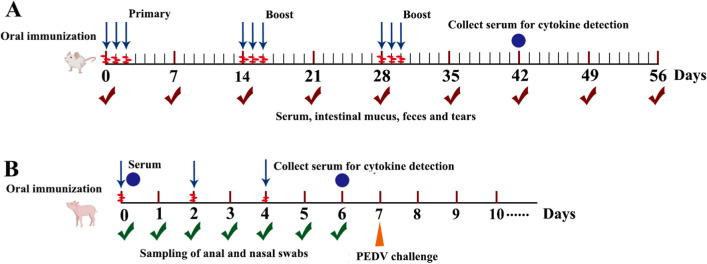

All animal experimentation protocols were approved by the Institutional Committee of the Northeast Agricultural University for Animal Experiments (2016NEFU-315; April 13, 2017) in Harbin, China. Four-week-old female specific pathogen-free (SPF) BALB/c mice (n = 90, 30 per group) were obtained from Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Liaoning, China). The mutant strain S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27 was cultured overnight for 16 h, and the cells were then harvested by centrifugation to adjust the concentration to 1 × 1010 CFU/mL. The mice in the experimental group were orally administered 200 µL of the mutant strain S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27. Meanwhile, the other two groups of mice were orally administered 200 µL of ΔAlr HLJ-27 and PBS as control groups, respectively. The procedure is shown in Fig. 2A.

Fig. 2.

The procedure of mice (A) or piglets (B) with oral immunization and sampling. A Serum, intestinal mucus, feces, and tears were collected at the day of 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, and 56. The mice were 90 in total, for 30 mice per group, and each sampling was repeated three times (three mice). Cytokine detection was carried out on 42 days post primary immunization with gathering the serum from the eyeball. The immunization procedure adopts continuous immunization for the interval time with 2 weeks between twice booster immunization and each immunization continuously for 3 days; B Large landrace piglets were 15 in total, including S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27 group (n = 6), ΔAlr HLJ-27 group (n = 3) and PBS group (n = 6). Piglet serum was collected on days 0 and 6 post immunization. Anal and nasal swabs were collected daily and soaked in PBS. The piglet immunization procedure was immunized for 2 days at a time, with a total of three immunizations. The cytokine levels in sera were measured on day 6 post immunization and challenged the piglets with PEDV to determine the immune protection of mutant S1/△Alr HLJ-27 with each group three piglets

Mice were orally immunized once every 14 days for a total of three times, consecutively for 3 days each time. Serum, feces, intestinal mucus, genital tract rinse, and tears were collected every 7 days for a duration of 56 days following the initial immunization. All samples were collected and stored at − 40 °C until further use. Serum was collected from the eyeball and diluted with 5% skim milk. The mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation, and 0.5 g of intestinal mucus was scraped, mixed with 500 µL of PBS, and subjected to shaking and centrifugation to obtain the supernatant, which served as the primary antibody. Fecal pellets weighing 0.1 g were treated with 500-µL PBS containing 0.05 mmol EDTANa2 and lysed for 16 h at 4 °C to obtain the supernatant for detection. The genital tract and the tears were acquired with 500 µL PBS washing mouse vagina or eyes, respectively, then to used directly as primary antibodies.

Large landrace piglets 0 days after birth, which had not been vaccinated with the PEDV vaccine, were purchased from the A’cheng Experimental Practice Base of Northeast Agricultural University. These piglets were kept in an isolation device and provided with fresh water and sterile milk. A total of 15 piglets were randomly divided into three groups; the piglets were orally immunized with 2 mL of 1 × 1010 CFU/mL of the mutant strain S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27 (n = 6), 2 mL of 1 × 1010 CFU/mL of ΔAlr HLJ-27 (n = 3) and 2 mL of PBS (n = 6), respectively, using the same strain treatment method employed in mice. The immunization protocol for the piglets was based on previous research in piglets, with slight optimizations. The neonatal piglets received three immunizations at 0, 2, and 4 days, respectively (Fig. 2B). Serum was collected from the anterior vena cava of the piglets on days 0 and 6. From days 0 to 6, anal and nasal swabs were collected and soaked in 1 mL of PBS, and the supernatant was obtained through centrifugation and used as the primary antibody to detect specific SIgA levels. The samples were collected and preserved at − 80 °C until further analysis.

Six days after piglet immunization, a challenge test was performed. The piglets in the S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27 (n = 3), ΔAlr HLJ-27 (n = 3), and PBS (n = 3) groups were challenged with 1 mL of PEDV LJB2019 small intestinal tissue ground sample (1 mL of PEDV LJB2019 small intestinal tissue ground sample) using oral-gastric gavage. The remaining piglets in the PBS group (n = 3) served as negative controls, while the piglets in the S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27 group (n = 3) were co-housed in the same cage with these challenge groups. Weight changes and the mental state of piglets were monitored daily. Piglets on the verge of death were immediately subjected to necropsy to analyze the protective effects provided by the mutant strain S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27.

Analysis of IgG and SIgA levels

To detect the levels of IgG and SIgA antibodies, serum and mucosal samples were collected at corresponding time points and determined using the indirect ELISA method. The PEDV LJB2019 strain was coated on 96 polystyrene microtiter plates as the antigen, and then washed thrice with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), blocked with 5% skim milk, and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After washing, the samples were added to the microplate with three repetitions and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h, serving as the primary antibody, while (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse/pig IgG or IgA served as the secondary antibody and was incubated for 1 h. The TMB chromogenic solution (Sigma, Ronkonkoma, NY, USA) was mixed with A + B in equal proportions for visual detection at an absorbance of 490 nm.

To assess the neutralizing capacity of antibodies induced by the mutant strain S1/ΔAlr HLJ-27 against virions, the levels of antibody neutralization in mouse or piglet serum were measured while maintaining a constant virus concentration. Serum samples (50 µL) were serially diluted by twofold and mixed with 50 µL of PEDV with a viral titer of 100 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50); the mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 100 µL of the mixture, with eight repetitions, was added to vero cell monolayers, which had been grown to a density of 80% and incubated for 1 h. Next, 100 µL of maintenance solution was added to each well, and the plate was placed in a 5% CO2 37 °C incubator for 72 h to observe cytopathic effects (CPE). Statistical analysis of the experimental results was performed using the Reed-Muench method.

Cytokine assay

On day 42 after immunization, two mice from each group were euthanized to collect serum from the eyeball, and ELISA kits were used to measure cytokine levels (BioSource International, USA). Piglet serum was also assessed on day 6 after the initial immunization. Each sample was replicated three times, and blank wells were used as controls. The detected cytokines included interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and the cytokine concentrations were analyzed by drawing a standard curve to calculate the numerical values for each ELISA plate. After euthanization, piglet serum was collected to assess the inflammatory factors, including IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-10.

qRT-PCR analysis

Real-Time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to determine the viral load in intestinal tissues using the ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with SYBR green fluorescent dye. Prior to the assay, a standard curve was established for the absolute quantification of the virus. A standard plasmid with an initial concentration of 1 × 1010 copies/μL was subjected to a tenfold dilution, and each dilution was repeated five times for qRT-PCR. Using the logarithm of the dilution of the plasmid standard as the x-axis and the corresponding Ct value (cycle threshold) as the y-axis, a quantitative standard curve corresponding to the plasmid copy number and Ct value was constructed. Total RNA was extracted from 0.1 g of intestine samples and reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was diluted to the same level and prepared for qRT-PCR using a SYBR® qPCR Mix Reagent Kit (Takara) to test the PEDV copy number in the intestine samples.

Gross lesion and histopathological examinations

Small intestinal tissues from the area with significant jejunal lesions were subjected to histopathological examination. Tissue samples were fixed in 4% polyformaldehyde, embedded into paraffin blocks, and sectioned at 3 µm. Hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining was utilized to observe the morphological changes of intestinal villi under a light microscope.

Statistical analysis

The statistics were presented as mean ± SE of three replicates per test in an independent experiment. GraphPad Prism 8 and Excel 2010 were used to analyze data discrepancies. The significance between the experimental and control groups was determined using two-way and one-way analysis of variance, along with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. * represents p < 0.05, indicating significance, while ** represents p < 0.01, indicating high significance.

Results

Construction and identification of the mutant strain S1/△AlrHLJ-27

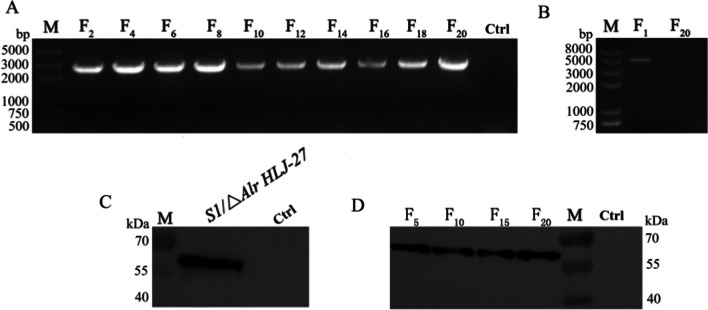

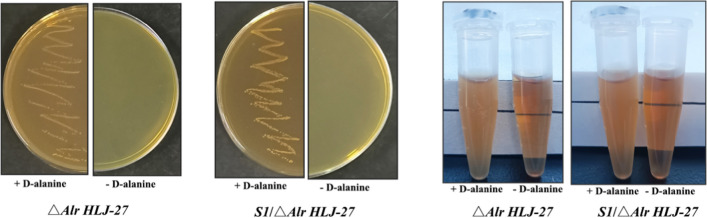

The plasmid pLCNICK-S1 was electroporated into L. paracasei △Alr HLJ-27 competent cells to generate the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27, in which the thymidylate synthase (thyA) gene was replaced by the P776-RS1 gene in the LAB genome. Genetic stability and plasmid elimination in strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 were detected. The strain was streaked on MRS plates containing 200 μg/mL d-alanine for 20 continuous passages, and genomic DNA was extracted every two generations for PCR identification. As shown in Fig. 3A, agarose gel electrophoresis showed that the genomic PCR amplification of the F1-F20 generation strains was 3415 bp bands, and the sequencing results confirmed the genetic stability of the locus, with no reverse mutation. Considering the passive effects of resistance gene residues in animals and humans, we conducted a PCR amplification test to examine the elimination of the gene-editing plasmid pLCNICK-S1, as shown in Fig. 3B. A 3956 bp band was observed in the F1 generation strain, in line with the expected size. Conversely, no band appeared in the F20 generation strain, indicating that the plasmid content decreased to undetectable levels or was completely eliminated. Based on the characteristics of the strain △Alr HLJ-27, the d-alanine requirement of the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 was tested. The strain was streaked on MRS plates containing 200 μg/mL d-alanine or basic MRS medium or inoculated in MRS broth supplemented with 200 μg/mL d-alanine or basic MRS medium for culturing. The results showed that the strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 could grow only when d-alanine was added, in line with its auxotrophic characteristics (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The gene hereditary, the plasmid elimination, and the stability of protein expression were detected of mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 (A, B, C). The genome of the strain was extracted every two generation within 20 generations to determine the stability of the gene inheritance by PCR amplification with thy-F/R as the primers and sequencing (A), M: Trans 2 k plus DNA marker; F2-F20: The F2-F20 generation strains of S1/△Alr HLJ-27; Ctrl: the strain of △Alr HLJ-27. The plasmid elimination situation of F1 and F20 generation strains was evaluated by plasmid PCR amplification with XA-F/R as the primers and sequencing (B), M: Trans 2 k plus II DNA marker; F1/F20: The F1/F20 generation strain of S1/△Alr HLJ-27. The expression of interest protein was detected by western blotting with mouse anti-S1 monoclonal antibody as a primary antibody (C). The stability of protein expression every five generation was determined (D)

Fig. 4.

The demand test of the mutant strain of S1/△Alr HLJ-27. The growth results as the strain streaking on the MRS plate (A) and in the MRS liquid (B). “ + ” represent the MRS with the d-alanine; “ − ” represent the MRS without the d-alanine

Expression of the target protein of S1 gene in strain S1/△AlrHLJ-27

The S1/△Alr HLJ-27 strain was inoculated into MRS medium supplemented with 200 μg/mL d-alanine and cultured at 37 °C for 16 h. Subsequently, the cells were harvested using lysozyme and ultrasonication to analyze the expression of the S1 protein through western blotting. Mouse anti-S1 monoclonal antibody was used as the primary antibody. As shown in Fig. 3C, a specific immunoreactive band of about 60 kDa was observed in the lysate of the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27, as expected, but not in △Alr HLJ-27, showing that S1 was expressed successfully by strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27. Moreover, to test the stability of S1 protein expression in the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 strain within 20 generations, protein samples were analyzed by western blotting every five generations (Fig. 3D). A specific band was detected in each generation of the strain, indicating the stable expression of the inserted foreign gene S1 in the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27.

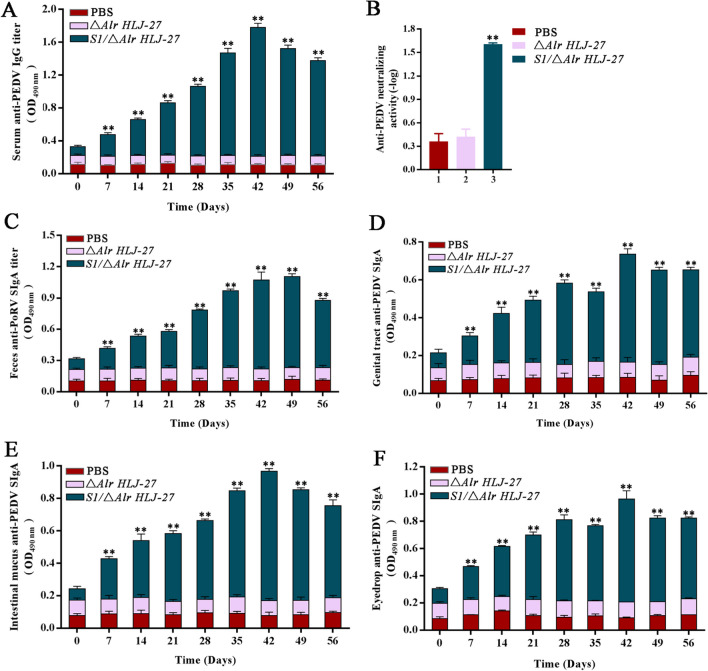

Detection of anti-PEDV IgG and SIgA levels, and analysis of PEDV-neutralizing activity of antibodies induced by the mutant strain S1/△AlrHLJ-27 via oral immunization in mice

To determine IgG and SIgA levels induced by the strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27, serum and the mucosal samples, including feces, intestinal mucus, genital tract rinse, and tears, were collected on days 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, and 56 after the initial immunization and determined using indirect ELISA. Seven days after the initial vaccination, IgG (Fig. 5A) and SIgA (Fig. 5C–F) levels induced by the mutant strain increased gradually, reaching a peak at 42 days, and then started to decrease. During the entire process of monitoring antibody levels, the levels of IgG and SIgA produced by strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 were significantly higher than those in the △Alr HLJ-27 and PBS groups. Two booster immunizations were administered on days 14 and 28. Subsequently, there were significant changes in the SIgA or IgG levels in the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 group.

Fig. 5.

Determination of anti-PEDV levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) (A) and secreted immunoglobulin A (SIgA) (C–F) in mice (n = 3 per group) with oral immunization the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27. Meanwhile, the neutralizing antibody activity of serum IgG was measured by the method for immobilizing viral load and to dilute antibodies (B). The supernatant of fecal lysis and intestinal mucus by centrifugation, eyedrop, genital tract rinse, and serum diluting with 5% skim milk were used as the primary antibodies. Bars represent the mean ± standard error value of each group (**p < 0.01 compared to the control groups PBS and △Alr HLJ-27)

The anti-PEDV-neutralizing activity induced by the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 was assessed while maintaining the number of viral particles (Fig. 5B). Compared to the △Alr HLJ-27 group (1:3) and the PBS group (1:2), the level of neutralizing antibodies produced in the serum of mice stimulated by the mutant bacteria group S1/△Alr HLJ-27 (1:40) was significantly increased. As expected, the strain effectively elicited an immune response against PEDV in vivo.

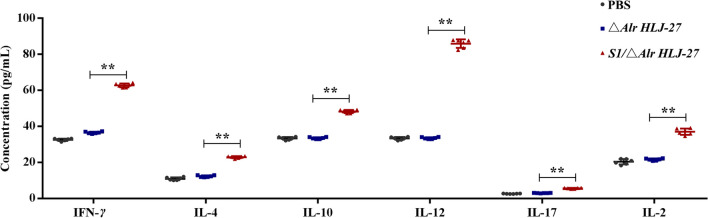

Determination of cytokine responses in mice

Fourteen days after the secondary booster immunization, serum was collected from the eyeball from two mice per group to assess the cytokine levels induced by S1/△Alr HLJ-27, as shown in Fig. 6. Based on the serum test, there was a significantly increase in IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, and IFN-γ level in the mutant S1/△Alr HLJ-27 group compared with the △Alr HLJ-27 and PBS groups.

Fig. 6.

Detection of the levels of serum cytokines. The cytokines from the mice (n = 3 per group) were analyzed with oral immunization of the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27. Bars represent the mean ± standard error value of each group (**p < 0.01 compared to the control groups PBS and △Alr HLJ-27)

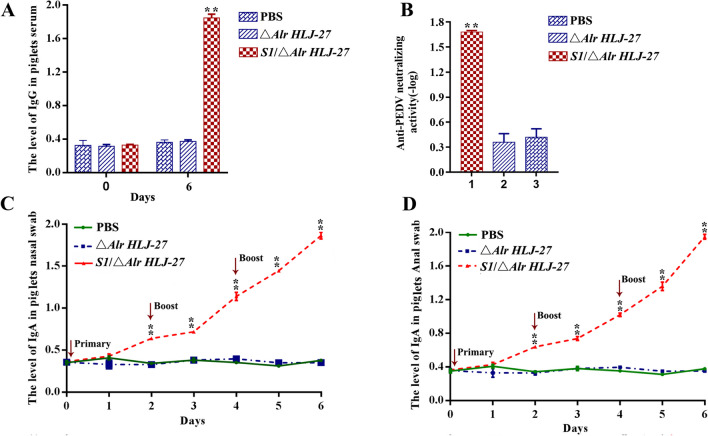

Detection of anti-PEDV IgG and SIgA levels and analysis of PEDV-neutralizing activity of antibodies induced by the mutant strain S1/△AlrHLJ-27 via oral immunization in piglets

To measure the SIgA antibody levels in piglets stimulated by S1/△Alr HLJ-27, anal and nasal swabs were collected from 0 to 6 days, and the supernatant was obtained through centrifugation for detection. The results are shown in Fig. 7C–D. SIgA levels in anal and nasal swabs gradually increased with the number of days of immunization. On day 6 after the primary immunization, the group receiving the strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 exhibited a significant increase in specific SIgA compared to the control groups. Following two booster immunizations, SIgA levels increased significantly, whereas before immunization, there was no significant statistical change in any of the groups. These results demonstrate that oral immunization with strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 induces a mucosal immunity response in piglets.

Fig. 7.

Determination of anti-PEDV levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) (A) and secreted immunoglobulin A (SIgA) (C–D) in piglets (n = 3 per group) with oral immunization the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27. Meanwhile, the neutralizing antibody activity of serum IgG was measured by the method for immobilizing viral load and to dilute antibodies (B). The supernatant of anal and nasal swabs by centrifugation and serum diluting with 5% skim milk was used as the primary antibodies to detect the levels of SIgA and IgG. Bars represent the mean ± standard error value of each group (**p < 0.01 compared to the control groups PBS and △Alr HLJ-27)

Serum was collected from the piglets via the anterior vena cava on days 0 and 6 to detect IgG antibody levels (Fig. 7A). Previously, there was no discrepancy in data between the △Alr HLJ-27 and PBS groups and test group S1/△Alr HLJ-27. On day 6, the IgG level in the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 group was markedly higher than that of the control group, indicating that the mutant strain could induce humoral immune response in piglets. These results show that antibodies induced by oral administration of the mutant strain in piglets could resist not only the virus particles in the gut but also the virus in vivo. The neutralizing activity in the serum induced by strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 in piglets was detected to evaluate the ability of the antibody to neutralize viruses (Fig. 7B). The level of neutralizing antibodies clearly increased in the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 group (1:64) compared with that in the △Alr HLJ-27 group (1:3) and the PBS group (1:2), indicating that S1/△Alr HLJ-27 could activate an effective immune response.

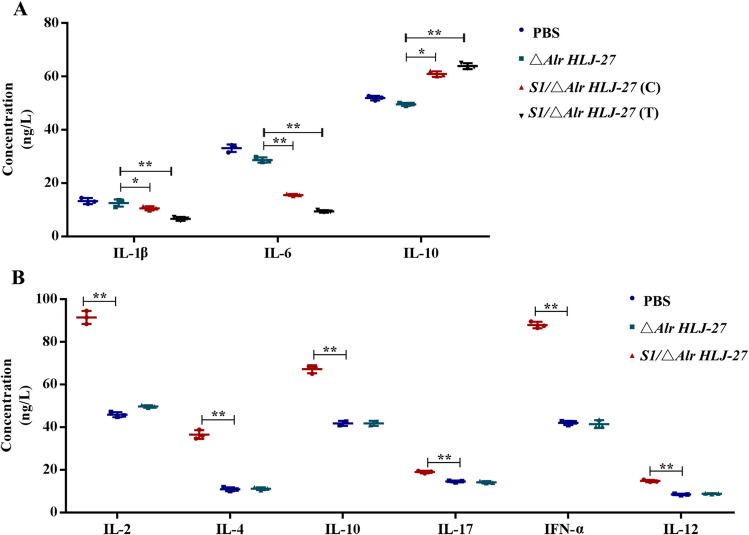

Determination of cytokine responses in piglets

During the oral immunization of piglets, serum samples were collected from the anterior vena cava on day 6 after the initial immunization and cytokine levels were examined using ELISA kits. Compared with the △Alr HLJ-27 and PBS groups, the IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, and IFN-γ levels of the mutant S1/△Alr HLJ-27 group were significantly increased, consistent with the experimental results found for mice (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Detection of the levels of serum cytokines (piglets: n = 3 per group). The cytokines pre-challenge (B) and post-challenge (A) in piglets with oral immunization the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 were analyzed. C represents the challenge experiments groups, and T represents the piglets, housed in the same cage with the challenge groups. Bars represent the mean ± standard error value of each group (**p < 0.01 compared to the control groups PBS and △Alr HLJ-27)

In the challenge test, weight changes and the mental state of piglets were monitored. In the PBS and △Alr HLJ-27 challenge groups, piglets developed a marked watery diarrhea, along with mental depression and extreme emaciation. In the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 challenge group, piglets manifested mild diarrhea, slight weight loss, and good mental state. In the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 co-cage infected group, a few piglets showed soft stools, good mental state, and normal appetite. An autopsy was performed immediately as the piglets were on the verge of death, and serum was collected simultaneously to detect cytokines related to the development of an inflammatory response (Fig. 8A). In this study, we examined the cytokine levels associated with the pro-inflammatory factors, IL-6, IL-1β, and the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10. After the piglets were challenged with PEDV, the IL-6 and IL-1β levels were significantly decreased in both the challenge and cohabitation infection groups with oral administration of the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27. Furthermore, the levels in the cohabitation infection group were lower than those in the challenge group. The IL-10 level showed a noticeable rise in both the challenge group and the cohabitation infection group with the strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27, and the cohabitation infection group exhibited higher levels than the challenge group. These results reveal that oral administration of the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 relieved the inflammatory response and elicited PEDV infection to some extent.

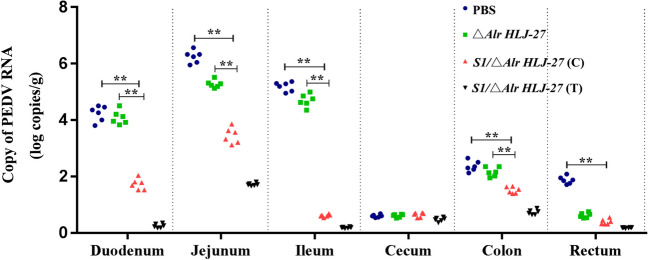

Determination of the viral load of intestinal tissue

To detect the viral load in each intestinal tissue of piglets challenged with PEDV, the tissue was ground to extract RNA, reverse-transcribed to cDNA, and tested using RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 9, compared to the △Alr HLJ-27 and PBS groups, the viral load in the intestinal tissues of the challenge group and the cohabitation infection group with the orally administered S1/△Alr HLJ-27 was markedly decreased, and the viral load in the cohabitation infection group was lower than that in the challenge group. These results revealed that oral administration of strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 had a protective effect on piglets.

Fig. 9.

Detection of viral load in different intestinal tissue in piglets (n = 3 per group) after challenge with PEDV. The piglets were administered infection with 1 mL of PEDV intestines crude extract at 6 days post primary immunization. C represents the challenge experiments groups, and T represents the piglets, housed in the same cage with the challenge groups. With the death of the piglets, necropsy was performed immediately to collect each intestinal fragment for virus detection. Bars represent the mean ± standard error value of each group (**p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared to the control groups PBS and △Alr HLJ-27)

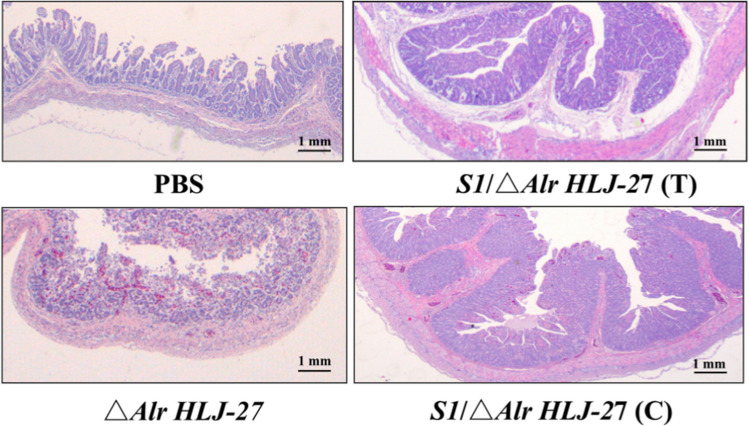

Gross Lesion and Histopathological Examinations

Small intestinal tissues from different treatment groups were collected for histopathological analysis (Fig. 10). Lesion on small tissues in PBS and △Alr HLJ-27 groups was more serious than that in S1/△Alr HLJ-27 groups, either the challenge experiments group or the co-cage infection group. Samples from the PBS group showed that the small intestinal villi were highly atrophic, necrotic, and even disaggregated and shed; the number of villi was significantly reduced; and some mucosal epithelial cells were shed. In △Alr HLJ-27 group, the villi of the small intestine were significantly atrophic, and the mucous epithelial cells degenerated and shed. Compared with PBS and △Alr HLJ-27 groups, the degree of villus atrophy in the small intestine of S1/△Alr HLJ-27 group was not obvious. The small intestinal villi were more intact in the cocage infected group than in the direct infected group.

Fig. 10.

Histopathological analysis of the strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 protective effect on immunized piglets. Histopathological examination of H&E-stained small intestinal tissues. The tissues were acquired from the groups administered PBS, △Alr HLJ-27 and S1/△Alr HLJ-27, post-challenge with 1 mL of PEDV intestines crude extract (RNA copy number of 1.0 × 106). “C” represents the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 challenge experiments groups, and “T” represents the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 piglets, housed in the same cage with the challenge groups. With the death of the piglets, necropsy was performed immediately to collect each intestinal for analysis. Original magnifications: 1 mm

Discussion

LAB are widely used as live vaccine carriers due to their safety, adjuvant properties, and weak immunogenicity (Xu et al. 2019). Traditional vaccines include inactivated vaccines and attenuated vaccines, but they all have certain defects. The immune response induced by intramuscular injection of inactivated vaccine takes a long time and could not effectively stimulate the mucosal immune response dominated by sIgA (Kim et al. 2023). The attenuated vaccine could induce the production of specific antibodies quickly and at high levels, yet there is a potential risk of reversion and enhancement of virulence (Teng et al. 2022). Researchers are committed to develop LAB oral vaccines, using plasmids to express heterologous proteins (Yang et al. 2018, Maqsood et al. 2018). Plasmid expression systems are often used to deliver foreign genes and antibiotics as selective markers, but this approach can cause issues such as the emergence of residual resistance genes and genetic instability (Douglas and Klaenhammer 2011), so to attempt to integrate foreign genes into the LAB genome to overcome these limitations.

Gene integration in LAB genome generally utilizes a double crossover recombination system, but the efficiency is low and the operation is complex (Goh et al. 2009, Hols et al. 1994). The development of the CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized gene editing in LAB, enabling convenient and rapid expression of foreign genes within the genome (Wang et al. 2021). In this study, the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 was constructed using a thermosensitive plasmid pLCNICK as the skeleton with the CRISPR-NCas9 system. This system performed a point mutation procedure on the Ruv C or HNH nuclease domains of Cas9 (Gasiunas et al. 2012). The mutated Cas9 protein (NCas9) cleaves only one strand of DNA, and a single incision is made without causing double-strand breaks in the DNA (Wu et al. 2022). Song et al. successfully employed the CRISPR-NCas9 system to perform four-gene knockout and insert the foreign gene EGFP into the genome with an efficiency range of 25–62% (Song et al. 2017). In our study, the S1 gene was integrated into the genome of △Alr HLJ-27 at the thyA site with an efficiency of 50% (the data was not shown), consistent with previous findings. Oh et al. showed that combining the CRISPR-Cas9 system with ssDNA recombination enhanced the efficiency of editing Lactobacillus reuteri to 100% (Oh and van Pijkeren 2014). Similarly, Guo et al. integrated optimized ssDNA recombination with the CRISPR/Cas9 system and successfully achieved sequential point mutation targeting the upp and galK gene loci, improving the gene-editing efficiency to 75% (Guo et al. 2019). These results provide new insights into gene editing in LAB.

In this study, thyA, encoding thymidylate synthase, was selected as the target site for genome integration. Lothar Steidler et al. substituted the IL-10 gene for thyA in the Lactococcus lactis genome and developed a validated therapy for chronic colon disease, which showed promising initial results (Steidler and Rottiers 2006). Zhou et al. successfully expressed bovine lactoferrin peptide with thyA site, and the results revealed that it was well resistant to pathogenic Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus infection (Zhou et al. 2018). In the present study, we introduced a combination of P776, the promoter of the pyruvate hydratase gene, along with S1, to replace the thyA locus. Yin et al. demonstrated through microarray experiment analysis that the pyruvate hydratase gene could be constitutively and efficiently expressed in the genome of L. casei, and this gene shares a high homology of up to 90% with many other LAB species. Researchers further utilized this site to integrate the VP4 gene of rotavirus into the LAB genome, with the promoter initiating the transcription of foreign genes, indicating that heterologous proteins could be expressed stably and efficiently in the host bacteria (Yin et al. 2016). The expression of the S1 gene was successfully detected by western blot analysis and proved the exogenous protein could be stably inherited within 20 generations, further validating the operability of the above findings.

Subsequently, the plasmid residues of the mutant strain were tested by extracting plasmids of the 1st and 20th generation strains, and PCR amplification results showed that the plasmid was either undetectable or completely eliminated, consistent with the study by Song et al. (Song et al. 2014a, 2014b), precluding the negative influence of antibiotics as screening markers. The strain △Alr HLJ-27, which was developed in our laboratory to restore growth through d-alanine supplementation (Li et al. 2022), was selected as the host bacteria. The mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27, generated in this study, retained this characteristic. There was a great significance for the artificial control of strains and the protection of intellectual property rights. The construction of △Alr HLJ-27 was based on the original wild-type strain HLJ-27, isolated from the intestine of large landrace piglets, as previous studies have shown that Lactobacillus isolated from the intestine of piglets has stronger colonization ability than Lactobacillus from other sources (Liu et al. 2014).

PEDV primarily destroys the intestinal epithelial tissue of piglets, highlighting the crucial role of mucosal immune SIgA in their defense to viral invasion. SIgA acts as a vital barrier against pathogen invasion in the gastrointestinal tract and neutralizes virions in the gut (Wang et al. 2018). Several studies have investigated the preparation of oral vaccines against PEDV. Wang et al. devised a mucosal DC-targeted oral vaccine using L. casei as the host to express DCpep and the COE gene of PEDV. Mice orally immunized with this vaccine exhibited effective induction of SIgA and IgG production (Wang et al. 2017). Li et al. applied alanine racemase-deficient L. casei W56 as the host strain and a complementary plasmid as a vector to express the neutralizing antigen COE of PEDV. After the oral immunization of mice, both SIgA and IgG levels increased significantly (Li et al. 2021). In this study, the protective antigen S1 gene of PEDV was inserted into the genome of the strain △Alr HLJ-27 to construct the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27. Mice and piglets were orally immunized with the strain to evaluate its immune effect.

In the mouse immunization experiment, we detected SIgA levels in tears, genital tract washing fluid, feces, and intestinal mucus. The results showed that the levels of SIgA in each index increased significantly, indicating that the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 in mice could elicit an effective mucosal immune response. Jiang et al. used L. casei W56 to present H antigen of canine distemper virus, then orally immunized mice to induce effective mucosal immune responses (Jiang et al. 2019). A piglet immunization experiment was performed, and we observed a significant increase in SIgA level in anal and nasal swabs of piglets immunized with the mutant strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27, as compared with the groups administered PBS and △Alr HLJ-27. The immune results in piglets were consistent with those observed in mice, indicating that the strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 could elicit mucosal immune responses in animals. SIgA antibody production was also detected in the experimental results of the nasal and anal swabs of Jiang and Hou et al. (Hou et al. 2018; Jiang et al. 2016). The mouse immune experiment served as a preliminary experiment for the development of the PEDV oral vaccine and laid the foundation for subsequent immune experiments on piglets. However, SIgA antibodies represent the primary defensive mechanism of mucosal immunity, while serum IgG level also plays a role in preventing pathogen invasion of the intestinal mucosa and systemic transmission, replenishing the mucosal protective mechanisms supplied by SIgA (Wells and Mercenier 2008). In the present study, a significant and sustained anti-PEDV IgG response was observed in S1/△Alr HLJ-27 mice, which peaked at 6 weeks post-immunization. Similar results were obtained in piglets, with a significant increase in serum IgG levels after oral immunization with the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 strain. Oral LAB vaccines can elicit antigen-specific humoral immune responses in animal models. Yu et al. demonstrated that the LAB oral vaccine could also induce humoral immunity. Recombinant L. casei was constructed by expressing protective antigens such as PEDV, TGEV, and eGFP as reporter genes. Serum IgG levels in mice increased significantly after oral immunization with the recombinant strain (Yu et al. 2017). The production of neutralizing antibodies is an important indicator of the ability of a LAB vaccine to provide immune protection. Neutralizing antibody levels in the serum of immunized mice and piglets were evaluated on days 42 and 6. Compared to the control groups, oral administration of the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 strain led to a significant rise in neutralizing antibody levels, indicating that the engineered strain was capable of inducing the production of neutralizing antibodies. Yin et al. successfully detected the presence of neutralizing antibodies in L. casei oral vaccine immunization experiments using mice as a model animal (Yin et al. 2016). Thereby providing effective protection for mice and piglets.

Analyzing secreted cytokines is vital for assessing the capacity of a genetically engineered vaccine to stimulate Th1 or Th2 responses (Rasquinha et al. 2021). IL-12 facilitates the differentiation of CD4+ T helper (Th0) cells into Th1 and Th2 cells, which produce cytokines and participate in immune regulatory functions, including the generation of neutralizing antibodies and the modulation of cellular immune responses (Mailliard et al. 2019). Cytokines secreted by Th1 cells, such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, are closely associated with cellular immune responses, whereas cytokines produced by Th2 cells, such as IL-4 and IL-10, are relevant to humoral immune responses (Nan et al. 2007). During this experiment, statistically significant changes were observed in the IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, and IFN-γ cytokines, indicating that the strain S1/△Alr HLJ-27 successfully induced Th1, Th2, and Th17 cellular immune responses in orally immunized mice and piglets. Xiao et al. utilized the strain L. casei deficient in the upp gene to express the PEDV S1 protein, orally immunized mice, and measured cytokine levels. The data revealed the successful induction of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell immune responses (Xiao et al. 2022). Zhang et al. developed the alanine racemase-deficient L. casei complementary system to express the VP4 gene of porcine rotavirus. The obtained results were consistent with the research of Xiao (Zhang et al. 2022). Recently, the activation of SIgA secretion to combat invasion by pathogenic microorganisms was demonstrated to be a T-cell-dependent immune response (Fagarasan et al. 2010). In this study, the S1 gene expressed by △Alr HLJ-27 was able to elicit high levels of SIgA secretion and both Thl- and Th2-type immune responses simultaneously, confirming the critical role of efficient T-cell–mediated immunity in SIgA production.

PEDV primarily infects the intestinal tract of piglets (Zhang et al. 2020); therefore, the development of an oral vaccine would play a key role in combating viral invasion. In previous studies, a recombinant L. casei W56 strain expressing a dendritic cell-targeting peptide fused with the PEDV COE antigen was developed to assess its immune protective effect in piglets. The genetically engineered strain could provide protection at a rate of 60% (Hou et al. 2018). To analyze the protective effect of the immune response induced by oral immunization with S1/△Alr HLJ-27 in piglets, we performed a challenge experiment. The piglets administered S1/△Alr HLJ-27 were divided into two groups: one group was carried out the challenge test, and the other was raised in the same cage. Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR was used to detect the copy number of PEDV RNA in each group of small intestinal tissues. Compared to the control groups, the immunized group showed a significant decrease in PEDV copy number. The copy number of PEDV in the cohabitation infection group of piglets immunized with the S1/△Alr HLJ-27 strain was the lowest among all groups. Histopathological results showed that compared with PBS and △Alr HLJ-27 groups, the extent of PEDV disruption to the small intestine was significantly reduced, and the villi were relatively intact. Hou and Wang et al. also showed that oral administration of recombinant lactobacilli expressing heterologous proteins could effectively protect the small intestinal villi from viral destruction (Hou et al. 2018, Wang et al. 2019). These results indicate the ability of specific SIgA and IgG antibodies to neutralize PEDV virus particles and contribute to immune protection in piglets to some extent.

During viral invasion, PEDV inflicts severe pathological damage on small intestine tissue, and its progression is closely related to the inflammatory response (Chen et al. 2020). Abnormal expression of proinflammatory factors in the gut, with abnormal elevation, results in a cascade of inflammation, tissue damage, and increased permeability of the intestinal barrier (Wu et al. 2016). In this study, we evaluated the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 in the serum of piglets in a challenge experiment. IL-1β and IL-6 served as typical inflammatory factors, while IL-10 represents the main anti-inflammatory factor in the intestines (Trapecar et al. 2014; Martin and Ales 2014, Roselli et al. 2016). Song et al. used mice as a model of acute colitis to study the therapeutic effect of bovine antimicrobial peptides; they measured the indexes of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 related to the inflammatory response (Song et al. 2019). Xie et al. also analyzed the corresponding inflammatory factor indexes IL-1β, IL-12, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 in the process of recombinant Lactobacillus reuteri against pathogenic Escherichia coli invasion using piglets as a model (Wang et al. 2021; Xie et al. 2021). Our findings showed that the levels of IL-1β and IL-6 in the serum of piglets significantly increased following PEDV challenge. After oral administration of genetically engineered strains to piglets, however, this secretion trend was ameliorated, and the level of IL-10 increased, suggesting a positive effect on the inflammatory status of the piglets. In piglets treated with the orally administered engineered strain, the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 in the co-infection group were lower than those in the challenge group, indicating that the inflammatory response caused by PEDV was milder in the co-infection group. This finding further supports the conclusion that recombinant bacteria provide immune protection for piglets.

To develop an oral vaccine against PEDV, we constructed a recombinant strain, L. paracasei S1/△Alr HLJ-27, using the CRISPR-NCas9 system. Our results indicate that S1/△Alr HLJ-27 could effectively activate mucosal, humoral, and cellular immune responses in mice and piglets following oral administration providing certain degree of protection against PEDV infection in piglets.

Acknowledgements

The gene-editing plasmid pLCNICK was kindly presented by Yang Sheng, Research Fellow, Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Shanghai Institute of Life Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author contribution

F. L., X. W., Y. L., H. Z., and S. L. conceived and designed the study. F. Y., X. L., G. G., J. L., Y. J., and W. C. performed the experiments. W. C. and Z. S. contributed new reagents or analytical tools. Z. S., H. Z., L. W., X. Q., and L. T. analyzed the data. F. L. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the Heilongjiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China Joint Guidance Project (LH2021C043), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; Grant 32102707 and Grant 31972718), and the Science and Technology Research Project of colleges and universities in Hebei province (BJK2023012).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Xiaona Wang, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Animal experiments were performed on the basis of the recommendations in the institutional and national guidelines for animal care and use. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China (2016NEFU-315; 13 April 2017). All procedures were carried out under ether anesthesia with the minimize suffering. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Fengsai Li, Haiyuan Zhao, and Ling Sui are joint first authors.

The original version of this article was revised. The affiliation links have been corrected.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/24/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s00253-024-13192-5

Contributor Information

Xiaona Wang, Email: xiaonawang0319@163.com.

Yijing Li, Email: yijingli@163.com.

References

- Agarwal N, Gupta R (2021) History, evolution and classification of crispr-cas associated systems-sciencedirect. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 179:11–76. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2020.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas I, Gruss A, Ehrlich SD, Maguin E (1993) High-efficiency gene inactivation and replacement system for gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol 175(11):3628–3635. 10.1007/BF02186240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Cui Y, Wang Z, Liu G (2020) Identification and characterization of PEDV infection in rat crypt epithelial cells. Vet Microbiol 249:108848. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas GL, Klaenhammer TR (2011) Directed chromosomal integration and expression of the reporter gene gusA3 in Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. AEM 77(20):7365–7371. 10.1128/AEM.06028-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelkrout E, Hayden C, Fake G, Keener T, Arruda P, Saltzman R, Walker J, Howard J (2020) Oral delivery of maize-produced porcine epidemic diarrhea virus spike protein elicits neutralizing antibodies in pigs. Plant Cell Tiss Org 142(1):79–86. 10.1007/s11240-020-01835-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evdokimova OV, Chindareva MA, Valentovich LN (2019) Characteristic of plasmids of Bacillus pumilus isolated in Belarus. Proc Nat Acad Sci Belarus Biol Series 64(3):292–301. 10.29235/1029-8940-2019-64-3-292-301 [Google Scholar]

- Fagarasan S, Kawamoto S, Kanagawa O, Suzuki K (2010) Adaptive immune regulation in the gut: t cell—dependent and t cell-independent iga synthesis. Annu Rev Immunol 28(1):243–273. 10.1146/annurev-Immunol-030409-101314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V (2012) Cas9–crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109(39):15539–15540. 10.1073/pnas.1208507109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh Y, Azcárate-Peril M, OFlaherty S, Durmaz E, Valence F, Jardin J, Lortal S, Klaenhammer T (2009) Development and application of a upp-based counterselective gene replacement system for the study of the S-layer protein SlpX of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. AEM 75(10):3093–3105. 10.1128/AEM.02502-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Xin Y, Zhang Y, Gu X, Kong J (2019) A rapid and versatile tool for genomic engineering in Lactococcus lactis. Microb Cell Fact 18(1):22. 10.1186/s12934-019-1075-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartanti A W (2010) Evaluation on anti-Diarrhea activity of Lactobacillus isolates from breast milk. Dissertation, Bogor Agricultural university

- Hols P, Ferain T, Garmyn D, Bernard N, Delcour J (1994) Use of homologous expression-secretion signals and vector-free stable chromosomal integration in engineering of Lactobacillus plantarum for alpha-amylase and levanase expression. AEM 60(5):1401–1413. 10.1128/aem.60.5.1401-1413.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X, Jiang X, Jiang Y, Tang L, Xu Y, Qiao X, Min L, Wen C, Ma G, Li Y (2018) Oral immunization against PEDV with recombinant Lactobacillus casei expressing dendritic cell-targeting peptide fusing COE protein of PEDV in piglets. Viruses 10(3):106. 10.3390/v10030106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Hou X, Tang L, Jiang Y, Ma G, Li Y (2016) A phase trial of the oral Lactobacillus casei vaccine polarizes Th2 cell immunity against transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus infection. AMB 100(17):7457–7469. 10.1007/s00253-016-7424-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Jia S, Zheng D, Li F, Wang S, Wang L, Qiao X, Cui W, Tang L, Xu Y, Xia X, Li Y (2019) Protective immunity against canine distemper virus in dogs induced by intranasal immunization with a recombinant probiotic expressing the viral H protein. Vaccines 7(4):213. 10.3390/vaccines7040213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HW, Ko MiKyeong, Park SH, Shin S, Kim SuMi, Park JongHyeon, Lee MJ (2023) Bestatin, a pluripotent immunomodulatory small molecule, drives robust and long-lasting immune responses as an adjuvant in viral vaccines. Vaccines 11(11):1690. 10.3390/vaccines11111690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Wang X, Fan X, Sui L, Zhang H, Li Y, Zhou H, Wang L, Qiao X, Tang L, Li Y (2021) immunogenicity of recombinant-deficient lactobacillus casei with complementary plasmid expressing alanine racemase gene and core neutralizing epitope antigen against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Vaccines 9(10):1084. 10.3390/vaccines9101084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Mei Z, Ju N, Sui L, Fan X, Wang Z, Li J, Jiang Y, Cui W, Shan Z, Zhou H, Wang L, Qiao X, Tang L, Wang X, Li Y (2022) Evaluation of the immunogenicity of auxotrophic Lactobacillus with CRISPR-Cas9D10A system-mediated chromosomal editing to express porcine rotavirus capsid protein VP4. Virulence 13(1):1315–1330. 10.1080/21505594.2022.2107646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Pieper R, Tedin L, Martin L, Meyer W, Rieger J, Plendl J, Vahjen W, Zentek J (2014) Effect of dietary zinc oxide on jejunal morphological and immunological characteristics in weaned piglets. JAS 92(11):5009. 10.2527/jas.2013-6690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailliard RB, Egawa S, Cai Q, Kalinska A, Bykovskaya SN, Lotze MT, Kapsenberg ML, Storkus WJ, Kalinski P (2019) Complementary dendritic cell-activating function of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells: helper role of CD8+ T cells in the development of T helper type 1 responses. J Exp Med 195(4):473–483. 10.1084/jem.20011662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maqsood I, Shi W, Wang L, Wang X, Han B, Zhao H, Nadeem A, Moshin B, Saima K, Jamal S, Din M, Xu Y, Tang L, Li Y (2018) Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of orally administered recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum expressing VP2 protein against IBDV in chicken. J Appl Microbiol 125(6):1670–1681. 10.1111/jam.14073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyyarikkandy M, Amalaradjou M (2017) Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus paracasei attenuate Salmonella enteritidis, Salmonella Heidelberg and Salmonella typhimurium colonization and virulence gene expression in vitro. Int J Mol Sci 18(11):2381. 10.3390/ijms18112381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan CL, Lei ZL, Zhao ZJ, Shi LH, Ouyang YC, Song XF, Sun QY, Chen DY (2007) Increased Th1/Th2 (IFN-gamma/IL-4) cytokine mRNA ratio of rat embryos in the pregnant mouse uterus. J Reprod Dev 53(2):219–228. 10.1262/jrd.18073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JH, van Pijkeren JP (2014) CRISPR-Cas9-assisted recombineering in Lactobacillus reuteri. Nucleic Acids Res 42(17):e131. 10.1093/nar/gku623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Trevino AE, Scott DA, Inoue A, Matoba S, Zhang Y, Zhang F (2013) Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell 154(6):1380–1389. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasquinha MT, Sur M, Lasrado N, Reddy J (2021) IL-10 as a Th2 Cytokine: differences between mice and humans. JI Medline 9:207. 10.4049/jimmunol.2100565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli M, Finamore A, Hynönen U, Palva A, Mengheri E (2016) Differential protection by cell wall components of Lactobacillus amylovorus DSM 16698T against alterations of membrane barrier and NF-kB activation induced by enterotoxigenic F4+ Escherichia coli on intestinal cells. BMC Microbiol 16(1):226. 10.1186/s12866-016-0847-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell WM, Klaenhammer TR (2001) Efficient system for directed integration into the Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus gasseri chromosomes via homologous recombination. AEM 67(9):4361–4361. 10.1128/AEM.67.9.4361-4364.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo PW, Gu DH, Kim JW, Kim JH (2023) Park SY and Kim JS (2023) Structural characterization of the type I-B CRISPR Cas7 from Thermobaculum terrenum. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 1871(3):140900. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2023.140900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song BF, Ju LZ, Li YJ, Tang LJ (2014a) Chromosomal insertions in the Lactobacillus casei upp gene that are useful for vaccine expression. AEM 80(11):3321–3326. 10.1128/AEM.00175-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Cui H, Tang L, Qiao X, Liu M, Jiang Y, Cui W, Li Y (2014b) Construction of upp deletion mutant strains of Lactobacillus casei and Lactococcus lactis based on counterselective system using temperature-sensitive plasmid. J Microbiol Methods 102:37–44. 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Huang H, Xiong Z, Ai L, Yang S (2017) CRISPR-Cas9D10A nickase-assisted genome editing in Lactobacillus casei. AEM 83(22):e01259-e1317. 10.1128/AEM.01259-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Xie W, Liu Z, Guo D, Zhao D, Qiao X, Wang L, Zhou H, Cui W, Jiang Y, Li Y, Xu Y, Tang L (2019) Oral delivery of a Lactococcus lactis strain secreting bovine lactoferricin-lactoferrampin alleviates the development of acute colitis in mice. AMB 103(15):6169–6186. 10.1007/s00253-019-09898-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidler L, Rottiers P (2006) Therapeutic drug delivery by genetically modified Lactococcus lactis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1072:176–186. 10.1196/annals.1326.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Fahd Q, Li Y, Sun Y, Li J, Qaria MA, He ZS, Fan Y, Zhang Q, Xu Q, Yin Z, Xu X, Li Y (2019) Transcriptomic analysis of small intestinal mucosa from porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infected piglets. Microb Pathog 132:73–79. 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.04.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Tang Y, Yan K, Chen H, Zhang H (2021) Inactivated Pseudomonas PE (△III) exotoxin fused to neutralizing epitopes of PEDV S proteins produces a specific immune response in mice. Anim Dis 1(1):22. 10.1186/s44149-021-00021-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Z, Meng L, Yang J, He Z, Chen X, Liu Y (2022) Bridging nanoplatform and vaccine delivery, a landscape of strategy to enhance nasal immunity. J Control Release 351:456–475. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.09.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapecar M, Goropevsek A, Gorenjak M, Gradisnik L, SlakRupnik M (2014) A co-culture model of the developing small intestine offers new insight in the early immunomodulation of enterocytes and macrophages by Lactobacillus spp. through STAT1 and NF-kB p65 translocation. PLoS ONE 9(1):e86297. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wang L, Chen Z, Ma X, Yang X, Zhang J, Jiang Z (2016) In vitro evaluation of swine-derived Lactobacillus reuteri: probiotic properties and effects on intestinal porcine epithelial cells challenged with Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88. Microbiol Biotechnol 26(6):1018–1025. 10.4014/jmb.1510.10089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang L, Huang X, Ma S, Yu M, Shi W, Qiao X, Tang L, Xu Y, Li Y (2017) Oral delivery of probiotics expressing dendritic cell-targeting peptide fused with porcine epidemic diarrhea virus COE antigen: a promising vaccine strategy against PEDV. Viruses 9(11):312. 10.3390/v9110312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang L, Zheng D, Chen S, Shi W, Qiao X, Jiang Y, Tang L, Xu Y, Li Y (2018) Oral immunization with a Lactobacillus casei-based anti-porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus (PEDV) vaccine expressing microfold cell-targeting peptide Co1 fused with the COE antigen of PEDV. J Appl Microbiol 124(2):368–378. 10.1111/jam.13652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Xia T, Guo T, Ru Y, Jiang Y, Cui W, Zhou H, Qiao X, Tang L, Xu Y, Li Y (2019) Recombinant Lactobacillus casei expressing capsid protein VP60 can serve as vaccine against rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus in rabbits. Vaccines 7(4):172. 10.3390/vaccines7040172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Yi Y, Lv X (2021) CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing platform for companilactobacillus crustorum to reveal the molecular mechanism of its probiotic properties. J Agr Food Chem 69(50):15279–15289. 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c05389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J, Mercenier A (2008) Mucosal delivery of therapeutic and prophylactic molecules using lactic acid bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 6(5):349–362. 10.1038/nrmicro1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Xu Z, Zhou Q, Li W, Wu Y, Du Y, Chen L, Zhang Y, Xue C, Cao Y (2018) Oral administration of coated PEDV-loaded microspheres elicited PEDV-specific immunity in weaned piglets. Vaccine 36(45):6803–6809. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle G, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA (2002) The role of Bacteroides conjugative transposons in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Cell Mol Life Sci 59(12):2044–2054. 10.1007/s000180200004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zhu C, Chen Z, Chen Z, Zhang W, Ma X, Wang L, Yang X, Jiang Z (2016) Protective effects of Lactobacillus plantarum on epithelial barrier disruption caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in intestinal porcine epithelial cells-ScienceDirect. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 172:55–63. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WH, Ma XM, Huang JQ, Lai Q, Jiang FN, Zou CY, Chen LT, Yu L (2022) CRISPR/Cas9 (D10A) nickase-mediated Hb CS gene editing and genetically modified fibroblast identification. Bioengineered 13(5):13398–13406. 10.1080/21655979.2022.2069940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Wang X, Li Y, Li F, Zhao H, Shao Y, Zhang L, Ding G, Li J, Jiang Y, Cui W, Shan Z, Zhou H, Wang L, Qiao X, Tang L, Li Y (2022) Evaluation of the immunogenicity in mice orally immunized with recombinant Lactobacillus casei expressing porcine epidemic diarrhea virus S1 protein. Viruses 14(5):890. 10.3390/v14050890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Song L, Wang X, Xu Y, Liu Z, Zhao D, Wang S, Fan X, Wang Z, Gao C, Wang X, Wang L, Qiao X, Zhou H, Cui W, Jiang Y, Li Y, Tang L (2021) A bovine lactoferricin-lactoferrampin-encoding Lactobacillus reuteri CO21 regulates the intestinal mucosal immunity and enhances the protection of piglets against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88 challenge. Gut Microbes 13(1):1956281. 10.1080/19490976.2021.1956281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Li Y, Shi Z, Hemme CL, Li Y, Zhu Y, Van Nostrand JD, He Z, Zhou J (2015) Efficient genome editing in clostridium cellulolyticum via CRISPR-Cas9 nickase. Appl Environ Microbiol 81(13):4423–4431. 10.1128/AEM.00873-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Cui L, Tian C, Zhang G, Huo G, Tang L, Li Y (2019) Immunogenicity of recombinant classic swine fever virus cd8 t lymphocyte epitope and porcine parvovirus VP2 antigen coexpressed by lactobacillus casei in swine via oral vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18(11):1979–1986. 10.1128/CVI.05204-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Wang J, Qi Q (2015) MOESM4 of Prophage recombinases-mediated genome engineering in Lactobacillus plantarum. Microb Cell Fact 14:154. 10.1186/s12934-015-0344-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Yang G, Zhao L, Jin Y, Jiang Y, Huang H, Shi C, Wang J, Wang G, Kang Y, Wang C (2018) Lactobacillus plantarum displaying conserved M2e and HA2 fusion antigens induces protection against influenza virus challenge. AMB 102(12):5077–5088. 10.1007/s00253-018-8924-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J, Guo C, Wang Z, Yu M, Gao S, Bukhari S, Tang L, Xu Y, Li Y (2016) Directed chromosomal integration and expression of porcine rotavirus outer capsid protein VP4 in Lactobacillus casei ATCC393. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100(22):9593–9604. 10.1007/s00253-016-7779-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Wang L, Ma S, Wang X, Wang Y, Xiao Y, Jiang Y, Qiao X, Tang L, Xu Y, Li Y (2017) Immunogenicity of eGFP-marked recombinant lactobacillus casei against transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Viruses 9(10):274. 10.3390/v9100274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampieri N, Camoglio F, Scire G, Laconi F, Pietrobelli A (2012) A38 Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei F-19 and intestinal failure: use in stage 1 of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC). Early Hum Dev 88(2):S113. 10.1016/S0378-3782(12)70064-6 [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Yu R, Zuo F, Zhang B, Peng D, Ma H, Chen S (2016) Heterologous expression and delivery of biologically active exendin-4 by Lactobacillus paracasei L14. PLoS ONE 11(10):e0165130. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HP, Wei GU, An-Qi JU, Jian-Fei BI, Lei QU, Cheng L, Chen L, Kang YH, Shan XF, Qian AD (2017) Effects of non-specific immunity and disease resistance of feeding Lactobacillus casei on common carp. Chin J Cardiovasc Med 53(7):85–88 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Cao Y, Yang Q (2020) Transferrin receptor 1 levels at the cell surface influence the susceptibility of newborn piglets to PEDV infection. PLoS Pathog 16(7):e1008682. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhao H, Zhao Y, Sui L, Li F, Zhang H, Li J, Jiang Y, Cui W, Ding G, Zhou H, Wang L, Qiao X, Tang L, Wang X, Li Y (2022) Auxotrophic Lactobacillus expressing porcine rotavirus VP4 constructed using CRISPR-Cas9D10A system induces effective immunity in mice. Vaccines 10(9):1510. 10.3390/vaccines10091510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Xu J, Tan M, Zhen J, Shu W, Yang S, Ma Y, Zheng H, Song H (2020) High copy number and highly stable Escherichia coli-Bacillus subtilis shuttle plasmids based on pWB980. Microb Cell Fact 19(1):25. 10.1186/s12934-020-1296-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Li X, Wang Z, Yin J, Tan H, Wang L, Qiao X, Jiang Y, Cui W, Liu M, Li Y, Xu Y, Tang L (2018) Construction and characterization of thymidine auxotrophic (ΔthyA) recombinant Lactobacillus casei expressing bovine lactoferricin. BMC Vet Res 14(1):206. 10.1186/s12917-018-1516-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Xiaona Wang, upon reasonable request.