Abstract

Complications of parasite infections, especially kidney disease, have been linked to poorer outcomes. Acute kidney damage, glomerulonephritis, and tubular dysfunction are the most prevalent renal consequences of Parascaris equorum infection. The purpose of this study was to determine the pharmacological effects of green-produced zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) on P. equorum infection in male Wistar rats. Thirty-six male rats were divided into two groups of 18 each: infected and non-infected. Both groups were separated into three subgroups, each of which received distilled water, 30 mg/kg ZnO NPs, and 60 mg/kg ZnO NPs. After 10 days of ZnO NPs administration, four larvae per gram of kidney tissue were present in the untreated infected group. While, no larvae were present in ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg) treated group, and one larva/g.tissue was present in ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) treated group compared to untreated infected animals. P. equorum infected rats had increased kidney biomarkers (creatinine, urea, uric acid), malondialdehyde, and nitric oxide, with a significant decrease in their antioxidant systems. On the other hand, infected treated rats with green-produced zinc oxide nanoparticles had a substantial drop in creatinine, urea, uric acid, malondialdehyde, and nitric oxide, as well as a significant rise in their antioxidant systems. P. equorum infection in rats caused severe degenerative and necrotic renal tissues. On the other hand, there were no detectable histopathological alterations in rats treated with ZnO NPs (30, 60 mg/kg) as compared to the infected untreated animals. When compared to infected untreated mice, immunohistochemical examination of nuclear factor-kappa B showed a significant decrease during treatment with ZnO NPs (30, 60 mg/kg). Green-produced zinc oxide nanoparticles are a viable therapeutic strategy for Parascaris equorum infection due to their potent anthelmintic activity, including a significant decrease in larval burden in infected treated rats.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, Anthelmintic, Parascaris equorum, Larvae

Introduction

Helminth infections are a big cause of illness and death in livestock animals around the world, which leads to long-term economic loss (Armstrong et al. 2014). Parascaris equorum is a parasitic roundworm that mostly affects the health of young horses and other equids such as zebras, donkeys, and mules. It is the most dangerous nematode for young horses, especially those under two years old (Morsy et al. 2019). Coughing, nasal discharge, weight loss, weakness, bristly hair coat, pneumonia, bronchial hemorrhage, colic, gastrointestinal issues and inappetence are clinical signs of equine ascariasis, but extensive infestations can lead to unthriftiness and, in rare cases, peritonitis and death due to small intestine rupture (Scala et al. 2021). Transmission of this nematode occurs via the fecal-oral route. Upon ingestion, second stage larvae penetrate intestinal mucosa and migrate to various tissues, including kidneys. Involvement of kidney in parasitosis is polymorphic, ranging from direct invasion to various types of glomerulonephritis (Jung et al. 2004). Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a relevant cause of acute kidney injury (AKI) that is considered as a form of hypersensitivity reaction. AIN as a heterogeneous disorder is uncommon in helminth infestation. Up to now only a few cases of AIN in parasitic infections (i.e. Ascaris lumbricoides and Giardia lamblia infection) have been recorded (De Pascalis and Buongiorno 2011). P. equorum infection in the renal tissues leads to permanent urogenital problems, renal failure, and malignancy because of its chronicity and tissue damage (Prastowo et al. 2014). In most cases, anthelmintic agents are highly efficacious, but drug resistance has been documented in many instances. The development of medication resistance and the detrimental effects on host animals enhance the demand for alternative medical agents with various mechanisms, despite the fact that chemical treatment is the most effective method for combating and removing helminth parasites (Ijaz 2018). Consequently, nanomaterials offer an alternative treatment for a number of parasitic infections that affect both human and animal health, particularly in terms of addressing the issue of resistance (Alajmi et al. 2019). Recently, nanoparticles have drawn considerable interest because of their special properties, such as high stability, wide bandgap, tiny size, and ability to penetrate biological barriers inside the body (Morsy et al. 2019). Zinc is an essential trace element that extensively exists in all body tissues, including brain, muscle, bone, skin, and so on. Also, Zn is the main component of various enzyme systems, it takes part in body metabolism and plays crucial roles in proteins and nucleic acid synthesis, hematopoiesis, and neurogenesis(Faisal et al. 2021). Zinc oxide nanoparticle (ZnO NP) is one of the most commonly applied nanomaterials in nanoelectronics, optoelectronics, field emissions, light-emitting diodes, photocatalysis, nanogenerators, and nanopiezotronics. ZnO NP, an ultraviolet light absorber, is applied in sunscreens as a nanomaterial, which is much more effective compared to the bulk materials(Khalil et al. 2023). In addition, ZnO nanoparticles have been reported to have strong anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, anthelmintic, anticancer, antimicrobial, and antiparasitic activities (Khatami et al. 2020). Traditional chemical techniques used to create nanomaterials cause hazardous substances to bind to their surfaces, potentially having detrimental medical effects (Morsy et al. 2019). Several studies indicated that eco-friendly techniques employing bioresources such as plants, fungi, or microbes for the synthesis of biogenic nanoparticles (NPs) are alternatives to conventional chemical synthesis methods. Bio-conjugated nanomaterials have a number of advantages for application in biomedical fields. Several biomolecules and proteins can facilitate the surface modification of synthesized nanomaterials for biomedical purposes (Karimzadeh et al. 2020). Egg white (albumen) is a suitable template for nanomaterials metal oxide synthesis. It acts as a stabilizer due to its solubility in water, capacity to bind with metal ions in solution, control particle growth, and decrease particle size. In addition, it has some functional properties like gelling, foaming and emulsifying with high nutrition qualities (Vijayakumar et al. 2020). This study aimed to evaluate the anthelmintic and renoprotective actions of eco-friendly synthesized ZnO NPs against P. equorum infection in rats.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced endogenously during mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, or they may result from interactions with exogenous sources like xenobiotic compounds (Ray et al. 2012). Overproduction of ROS results in an oxidative stress state that has been connected to a number of major disorders, including cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, ischemia/reperfusion damage, and even parasite infestation (Gupta et al. 2022). Recent studies have suggested intestinal parasitic infections can stimulate the excessive production of free radicals, provoking the occurrence of oxidative stress (Elmeligy et al. 2021). Lipid peroxidation (LP) is an ongoing physiological process caused by ROS that results in the disarrangement and disruption of cell membranes, which leads to necrotic death (Bildik et al. 2004). Since malondialdehyde (MDA) is a byproduct of lipid peroxidation, measuring its amount indirectly assesses the degree of LP and the quantity of ROS (Deger et al. 2009). Nitric oxide (NO) is a crucial mediator in biochemical reactions that are produced by numerous cell types in response to cytokine stimulation. Therefore, it plays a function in the immunologically mediated protection against a growing number of parasites (Deger et al. 2009; Shehata et al. 2022).

Materials and methods

Experimental design

Thirty-six male Wistar rats were allocated into two main groups: The first group (18 non-infected rats) was divided into 3 subgroups (6 rats per subgroup): Subgroup I (control group): Rats received a single oral dose of saline and then distilled water for 10 days. Subgroup II (ZnO NPs (1/20 LD50)): Rats orally received 30 mg/kg of ZnO NPs for 10 consecutive days. Subgroup III (ZnO NPs (1/10 LD50)): Rats orally received 60 mg/kg of ZnO NPs for 10 consecutive days.

The second group (18 P. equorum infected rats) received a single oral dose of 1000 P. equorum eggs (dos Santos et al. 2017) and was then divided into 3 subgroups (6 rats per subgroup). Subgroup I (vehicle): Rats received distilled water for 10 days. In the second day of infection, subgroup II (ZnO NPs (1/20 LD50): Rats orally administered 30 mg/kg of ZnO NPs for 10 consecutive days. Subgroup III (ZnO NPs (1/10 LD50): Rats orally administered orally 60 mg/kg of ZnO NPs for 10 consecutive days.

Animal handling and specimen collection

After 10 days, sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg body weight) was injected intraperitoneally to anesthetize the rats. Exsanguination was used to obtain blood samples. For biochemical analysis, serum from each rat was stored in sanitized microcentrifuge tubes and stored at -80 °C. The kidney samples were removed, cleaned with physiological saline, and divided into three sections: one for histopathological evaluation, one for recovering P. equorum larvae, and one for biochemical tests.

Green synthesis of ZnO NPs

In a 70 ml aqueous solution of 0.25 M zinc acetate, 30 ml of egg albumin was added gradually. The resultant solution was magnetically stirred at room temperature for twenty minutes to produce a colloidal solution. After adding 0.5 ml of NH3 solution with a pH of 7.0 and centrifugating at 2795 xg for 10 min, the precipitate formed. The obtained pellet was washed twice with sterile distilled water and dried in the vacuum oven for 6 h at 100 °C. After that, it was subjected to a 3-hour sintering process at 400 °C (Shoeb et al. 2013).

Purification of ZnO NPs

The nanoparticles were cleaned in a 1:5:1 volume fraction mixture of methanol, hexane, and isopropanol. ZnO NPs were added to methanol-producing ZnO methanol colloids. White ZnO nanoparticles precipitated after adding hexane and isopropanol to ZnO methanol colloids. The mixture was left at 0 °C overnight to complete the precipitation of ZnO NPs. The precipitated ZnO was redispersed in methanol by shaking after centrifugation and after removing the supernatant. The previous procedures were performed numerous times until all contaminants in ZnO NPs were eliminated by obtaining clean supernatant (Sun et al. 2007).

Characterization of ZnO NPs

The shape and size of ZnO NPs were assessed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at an accelerated voltage of 120 kV (JEM 2100 F; JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). (Electron Microscopy Unit, Faculty of Agriculture, Cairo University) (Faisal et al. 2021). X-ray diffraction pattern (XRD) was employed to assess the crystallographic characteristics of nanomaterials. At ambient temperature, ZnO NPs powder was subjected to XRD patterns using an analytical x’pert pro- X-ray diffractometer equipped with a nickel filter using copper (Cu) Ka radiation as an X-ray source (Karimzadeh et al. 2020). Ultra-violet–Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a simple and sensitive technique that can detect the optical absorbance (A) of ZnO NP suspensions. A double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1601) was used in the wavelength range of 200–700 nm and operated at an interval of 10 nm (Faisal et al. 2021).

Goodwin’s physiological solution preparation

Calcium chloride (0.20 g), glucose (5.0 g), magnesium chloride (0.10 g), potassium chloride (0.20 g), sodium bicarbonate (0.15 g), sodium chloride (8.0 g), and sodium hydrogen phosphate (0.5 g) were used to formulate Goodwin’s physiological solution. All compounds were dissolved in 1000 ml of distillated water. Calcium chloride was introduced after dissolving the other salts because it would precipitate the other salts if added prior to dissolution. To prevent fermentation, glucose was added shortly before use, and the solution was preheated to 37 °C before being placed in the warms (Nalule et al. 2013).

Collection of adult female worms

At Cairo University’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, digestive tracts from recently butchered Equus ferus caballus Linnaeus (1758) (Family Equidae) donkeys were gathered. Adult female worms were separated after the contents of the gastrointestinal tract were examined, and they were stored in Goodwin’s solution at 37 °C until further use.

Preparation of the parasite eggs

Female worms were dissected to obtain P. equorum eggs, which were then collected in acidic water (pH = 3). Centrifugation was used to concentrate the collected eggs for five minutes at 1,500 rpm. The newly extracted eggs were used for embryonation and the development of the infectious stage. A hydrophobic cotton plug was used to cover a beaker containing 0.5% formalin and was cultured for 20 days to produce embryonated eggs. For the production of third-stage larvae, this egg solution was manually stirred twice daily. The formalin solution was removed from the embryonated eggs by washing them three times in saline after the incubation period (Versteeg et al. 2020).

Animal housing

Male Wistar adult rats weighing between 150 and 160 g were bought from the National Research Center (NRC, Dokki, Giza), gathered, and housed in polypropylene cages in an animal facility with good ventilation. Rats were kept in a comfortable setting with a 12-hour light/dark cycle at ambient temperature (22–25 °C). Prior to the trial, they were given seven days to acclimate to their surroundings while being fed regular chow pellets and given unlimited access to water. The institution’s policies on the handling and use of animals in research were followed when using animals in experiments.

Acute toxicity study

According to Chinedu et al. (2013), eight male rats were used for the determination of the LD50. The rats were divided into four groups (A-D) of two animals each. Groups (A–D) were given orally different doses of ZnO NPs (10, 100, 300, and 600 mg/kg), respectively. The rats were observed for 1 h post-administration and then for 10 min at every 2-hour interval for 24 h for signs and symptoms of toxicity and death. The LD50 was calculated using the formula:

where M0 is the highest dose of biocompatible ZnO NPs that caused no mortality; M1 is the lowest dose of ZnO NPs that caused mortality.

Digestion technique to detect larvae in renal tissues

The fixed weight of renal tissues was placed into a digestive solution (2 ml of 0.5% HCL) and held to recover the larvae for 24 h at 37 °C. After the incubation period, infected tissues were removed, and the digestive solution containing larvae was centrifugated for 5 min at low speed. Then, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was examined under a light microscope (dos Santos et al. 2017).

Kidney homogenate preparation

M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) was used to homogenize kidney tissues (10% w/v) at ice-cold temperatures. The homogenate was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 40 °C, and the collected supernatant was applied to biochemical tests.

Biochemical assays

The manufacturer’s recommendations were followed for analyzing the collected sera for creatinine, urea, uric acid, calcium, and phosphorus using Biodiagnostic kits (Giza, Egypt).

Oxidative stress markers

The supernatant of the kidney homogenate was used for biochemical analysis according to the manufacturer’s instructions using Biodiagnostic kits (Giza, Egypt). Malondialdehyde (MDA), an index of lipid peroxidation (Colorimetric Kit), glutathione reduced (GSH) (Colorimetric Kit), glutathione-s-transferase (GST) (Kinetic Kit), nitric oxide (NO) (Colorimetric Kit), and catalase (CAT) (Kinetic Kit) were determined.

Histopathological examination

Kidney samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Bancroft and Stevens 1996).

Immunohistochemistry

Kidney tissue slices were cut for immunostaining. Briefly, an epitope retrieval phase was followed by peroxidase blocking on tissue slides. Slides were treated with primary anti-NF (Abcam kits, Waltham, United States) (diluted 1:100) for 2 h at room temperature, washed with phosphate buffer saline, and then the reaction was developed and seen using a Mouse/Rabbit Immuno-Detector DAB HRP kit from Bio SB in California, USA. Slides without the primary antibody were produced by skipping that stage. Using Cell Sens dimensions, positive expression was measured as a percentage of the area. Software from Olympus (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (Khalil et al. 2023).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was evaluated through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the least significant difference (Duncun) post hoc test used to compare the group means, data were presented as mean ± SE and p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Characterization of green synthesized ZnO NPs

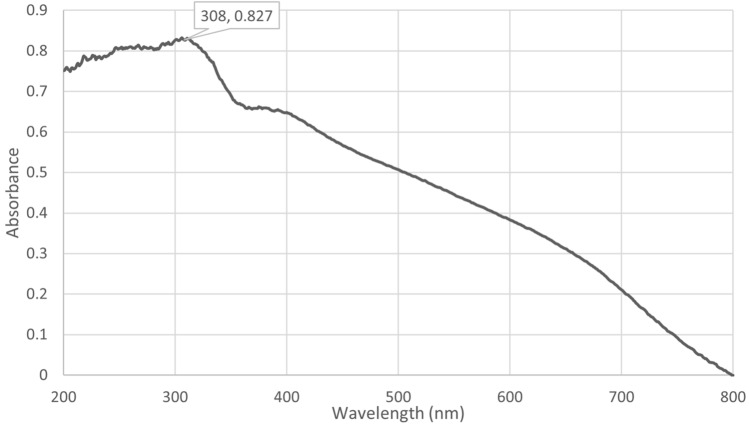

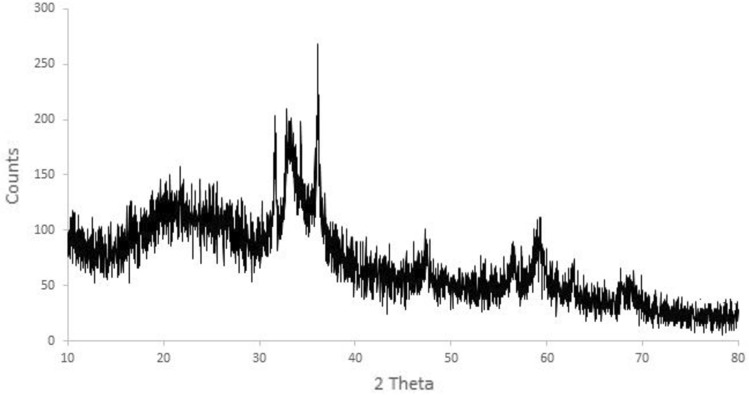

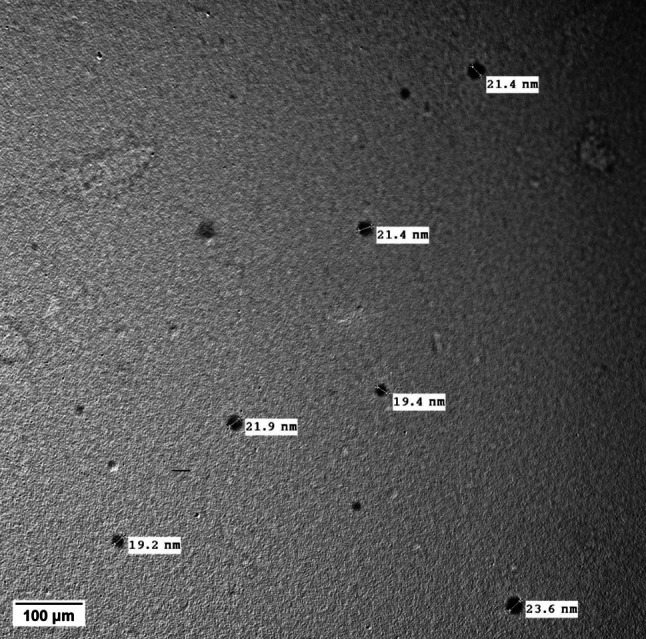

Figure 1 showed transmission electron micrograph of ZnO NPs that were almost homogeneously polygonal in shape with a particle size of less than 25 nm. The ultraviolet spectra indicated that ZnO NPs have characteristic peaks between 300 and 350 nm. The sample’s distinctive peak can be seen at 308 nm (Fig. 2). Figure 3 illustrated the X-ray diffraction pattern of green nanomaterials The peaks of XRD at 2 θ were equal to 31.49°, 32.88°, 34.14°, 35.96°, 47.20°, 56.21°, 58.82°, 62.47°, 65.92°, 67.47°, and 68.63°, which corresponded to the crystal plans 100, 002, 002, 101, 102, 110, 110, 103, 200, 201, and 202 of ZnO NPs. The obtained peaks suggested that ZnO NPs possessed a hexagonal crystal structure. There was a characteristic peak at 21.78°, suggesting the presence of egg albumin. The average crystallite size of ZnO NPs was found to be approximately 20 nm. The crystallite or particle size was calculated using the Debye-Scherrer equation for all diffraction peaks.

Fig. 1.

TEM image of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using egg white. Scale bar 100μm

Fig. 2.

UV-Vis spectroscopy of ZnO nanoparticles

Fig. 3.

XRD Pattern of ZnO NPs

Acute toxicity of ZnO NPs

ZnO NPs up to a dosage of 600 mg/kg did not produce any mortality. The median effective dose (ED50) was selected based on the proposed LD50 obtained from the acute toxicity study. Two doses were selected, which are 1/10 and 1/20 of the proposed LD50, that is, 600 mg/kg body weight.

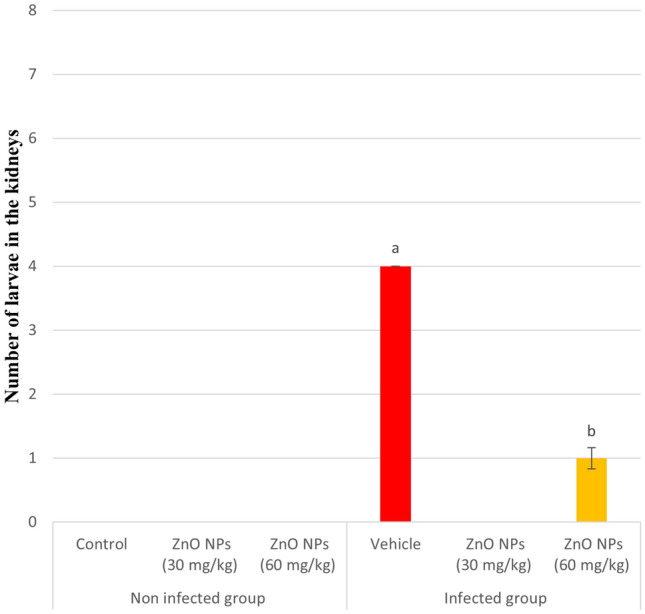

Counting the kidney’s recovered larvae

Figure 4 showed the effect of different concentrations of ZnO NPs (30 and 60 mg/kg) on rats infected with P. equorum larvae after 10 days of administration. Four larvae per gram of kidney tissue were present in the untreated infected group, no larvae were present in ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg), and one larva /g.tissue in ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) treated groups. The treatment with ZnO NPs (30,60 mg/kg) caused a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in larvae count compared to the untreated infected group and F-statistic equal 271.

Fig. 4.

Larval counts in infected kidney. Results are expressed as mean ± SE in each group. a : significant at (P < 0.05) compared to control group. b : significant compared to vehicle group

Biochemical findings

The rats infected with P. equorum showed a significant elevation (p < 0.05) in creatinine, urea, and uric acid levels in the vehicle group compared to control animals. Oral treatment of ZnO NPs (30 and 60 mg/kg) for 10 days caused a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the levels of creatinine, urea, and uric acid to nearly normal levels compared to the untreated infected group (Table 1). The F-statistic of creatinine, urea, and uric acid levels were equal 4,3,7 respectively.

Table 1.

Therapeutic effect of ZnO NPs on kidney function markers in P. equorum infected rats

| Groups | Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | Urea (mg/dl) | Uric acid (mg/dl) | ||

| Noninfected groups | Control | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 43.80 ± 3.58 | 1.92 ± 0.09 |

| ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg) | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 48.90 ± 2.37 | 1.67 ± 0.14 | |

| ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 44.82 ± 0.91 | 1.68 ± 0.09 | |

| Infected groups | Vehicle | 0.58 b ± 0.03 | 57.15 a ±2.64 | 2.68 a ± 0.21 |

| ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg) | 0.48 a ± 0.02 | 48.28 b ± 2.53 | 1.92 b ± 0.17 | |

| ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) | 0.46 a ± 0.02 | 45.65 b ± 1.74 | 1.78 b ± 0.09 | |

Oxidative stress markers

Data recorded in Table 2 showed a significant elevation in MDA and NO levels in the vehicle group compared to the control group. Contrarily, treatment with ZnO NPs caused a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in MDA and NO levels compared to the vehicle group. The F-statistic of MDA and NO levels were 600 and 36 respectively. A significant decline (p < 0.05) was observed in GSH, CAT, and GST levels in the vehicle group, as compared to the control group. There was a significant elevation (p < 0.05) in GSH, CAT, and GST levels after treatment with ZnO NPs (30 and 60 mg/kg), as compared to the vehicle group (Table 2). While the F-statistic of GSH, CAT, and GST levels were 61,503 and 389, respectively.

Table 2.

Therapeutic effect of ZnO NPs on some oxidative stress markers in P. equorum infected rats

| Groups | Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA (nM/g.tissue) | GSH (mM/g.tissue) | CAT (U/min/g.tissue) | GST (µM/g.tissue/min) | NO (µM/g.tissue) | ||

| Noninfected groups | Control | 5.21 ± 0.15 | 2.13 ± 0.05 | 959.78 ± 12.95 | 6.16 ± 0.14 | 2,539.93 ± 76.17 |

| ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg) | 5.59 ± 0.13 | 1.92 ± 0.05 | 887.09 ± 51.34 | 5.61 ± 0.20 | 2,293.96 ± 90.80 | |

| ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) | 5.53 ± 0.10 | 2.00 ± 0.01 | 903.13 ± 13.08 | 5.92 ± 0.03 | 2,392.06 ± 42.26 | |

| Infected groups | Vehicle | 7.98 a ± 0.16 | 1.14 a ± 0.04 | 239.61 a ± 9.16 | 1.67 a ± 0.04 | 3,150.54 a ± 13.28 |

| ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg) | 7.16 b ± 0.11 | 1.61 b ± 0.08 | 360.67 b ± 5.07 | 3.73 b ± 0.06 | 2,878.51b ± 93.02 | |

| ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) | 6.05 b ± 0.11 | 2.09 b ± 0.07 | 484.21 b ± 15.89 | 4.54 b ± 0.13 | 2,644.96 b ± 46.55 | |

aSignificant at (P < 0.05) compared to the control group. bSignificant compared to vehicle group

Histopathology

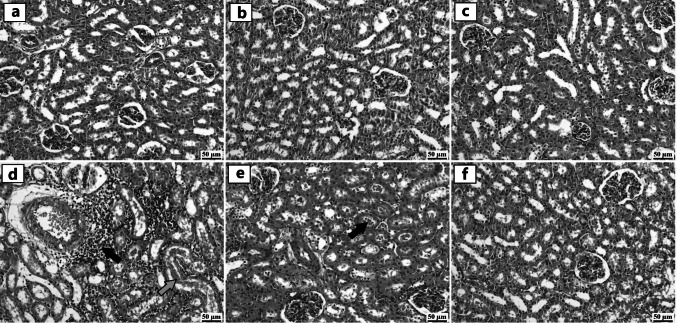

The control group revealed the normal histological structure of renal tubules and interstitial tissue in the renal cortex and medulla (Fig. 5a). Similar results were detected in the ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg) and ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) groups without any detectable histopathological alterations in the renal parenchyma (Fig. 5b and c). Administration of P. equorum eggs in the vehicle group revealed serious histopathological abnormalities in the renal tissue. The epithelial lining of renal tubules exhibited degeneration and necrosis with the accumulation of renal casts in the tubular lumen. The interstitium tissue showed mononuclear inflammatory cells infiltrating the renal cortex and medulla. The inter-tubular blood vessels exhibited congestion associated with perivascular edema and inflammatory cell aggregations (Fig. 5d). Moderate improvement was determined in infected rats with P. equorum eggs treated with ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg). This group was characterized by fewer inflammatory cells infiltrating the interstitial tissue in the renal parenchyma, accompanied by mild cloudy swelling of the lining epithelium and mild renal casts (Fig. 5e). The highest protective effect was detected in the group treated with ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg), which revealed normal renal parenchyma in almost all examined sections (Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5.

Photomicrographs of the kidney (hematoxylin and eosin stain). a control group, b ZnO NPs (30 mg/Kg) group, and c ZnO NPs (60 mg/Kg) group showing normal histological structure of renal tubules in the renal cortex without any detectable histopathological alterations in the renal parenchyma. d vehicle group showing perivascular edema and inflammatory cells infiltration (black arrow) with presence of renal cast in the tubular lumen (green arrow). e P. equorum + ZnO NPs (30 mg/Kg) group showing presence of renal casts in the tubular lumen (arrow). f P. equorum + ZnO NPs (60 mg/Kg) group showing apparently normal renal tissue

Immunohistochemistry

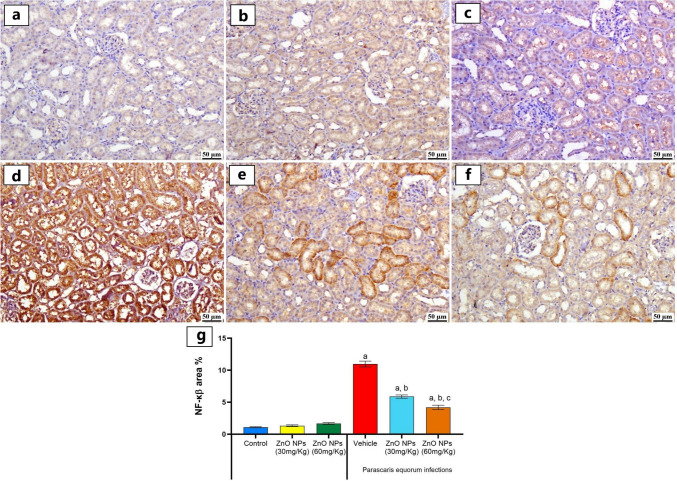

The expression levels of NF-kB in the kidneys of different experimental groups were determined by immunohistochemistry. The one-way ANOVA indicated that the vehicle group had histological alterations with a strong positive expression of NF-kB in the renal tubular epithelium of affected renal parenchyma in comparison with a normal expression that was detected in the control, P. quorum + ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg), and P. quorum + ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) groups. Moderate expression was detected in P. equorum + ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg), with markedly lower expression in the renal tubules of the P. equorum + ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) group (Fig. 6e and f). The vehicle group showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) when compared to other groups (Fig. 6d). Meanwhile, no significant difference was observed between the control, ZnO NPs (30 mg/kg), and ZnO NPs (60 mg/kg) groups (Fig. 6a, b, and c). While the F-statistic of NF-kB expression in the kidney tissue equal 205.

Fig. 6.

Photomicrographs of kidney (Immune staining). a control group showing normal negative to limited NF-κβ staining, b and c ZnO NPs (30, 60 mg/Kg) groups exhibiting normal amounts of NF-κβ. d vehicle group showing intense renal NF-κβ staining. e P. equorum + ZnO NPs (30 mg/Kg) group showing moderate positive expression. f P. equorum + ZnO NPs (60 mg/Kg) group showing mild positive staining. g Charts represent quantified NF-κβ expression as area %. Data presented as means ± SE. Significance considered at P˂0.05

Discussion

Creatinine, urea, and uric acid levels are considered the most accepted measures of kidney function. The current investigation revealed that inoculation of P. equorum eggs showed a marked elevation in creatinine, urea, and uric acid levels. The accumulation of worms in the renal tubules causes glomerular lesions, urinary abnormalities, and inflammatory reactions that lead to a decrease in glomerular filtration rate and an increase in creatinine, urea, and uric acid levels in the blood (Prastowo et al. 2014). Additionally, parasitosis infection causes conservation in body fluids, which increases metabolic waste materials in the blood such as creatinine, urea, and uric acid. The decrease in creatinine, urea, and uric acid levels to near normal levels in P. equorum-infected rats by the treatment with ZnO NPs indicates a possible protective effect of renal structures against degenerative processes due to parasitic infection (Bayoumy et al. 2020).

The present investigation showed a significant increase in the levels of MDA and NO following P. equorum infection in rats, suggesting that nematode infection induces oxidative stress (Espinoza et al. 2002). Intestinal parasites cause a reduction in the levels of protective endogenous antioxidants and inflammation when they penetrate the mucosa (Dkhil et al. 2017). Inflammatory reactions are accompanied by the generation of ROS, which may lead to the deterioration of vital functions and cell death (Sarma et al. 2012). ROS overproduction in the chain of biochemical reactions results in an increase in lipid peroxides as MDA, which is the most important product of lipid peroxidation (Bauomy 2020). On the other hand, treatment with ZnO NPs in the current study significantly decreased the MDA and NO levels in P. equorum-infected rats. Nanomaterials can protect cell membrane integrity against oxidative stress damage (Afifi et al. 2015). ZnO NPs can act through many antioxidant mechanisms, including the scavenging of active oxygen radicals and inhibition of lipid peroxidation (Shehata et al. 2022). Along the same line, ZnO NPs regulate the pathological conditions caused by the unwarranted generation of MDA and NO (Dkhil et al. 2017).

Antioxidants are compounds that neutralize and inactivate free radical activity, thus protecting against oxidative stress and cellular damage (Benerji et al. 2013). Endogenous antioxidants are GSH, SOD, CAT, glutathione peroxidase, and thioredoxin. While exogenous sources are essential nutrients such as vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene, selenium, bioflavonoids, proanthocyanidins, and N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) (Prabhu et al. 2021). The current study disclosed that GSH, CAT, and GST activities of P. equorum-infected rats decreased significantly after the experimental period. Intestinal parasitic infection impairs the antioxidant system by decreasing GSH levels and total antioxidant capacity. This decline was attributed to the increased cytotoxicity of H2O2 produced because of the inhibition of glutathione reductase, which keeps glutathione in a reduced state (MOAWAD et al. 2015). In addition, ROS produced by the parasites exhausts the host’s SOD, CAT, and GSH in the neutralization mechanism (Mahadappa and Dey 2018). In addition, parasitosis may lead to a decrease in vitamin E and C levels; the former acts as a chain-breaking lipophilic antioxidant and can protect membranes against the action of ROS. While the latter and hydrophilic antioxidants GSH play a role in the sparing of vitamin E (Kolodziejczyk et al. 2006). On the other hand, GSH level, CAT, and GST activities were improved after treatment with ZnO NPs in P. equorum-infected rats. Marreiro et al. (2017) indicated that zinc acts as a co-factor for important enzymes involved in the antioxidant defense system. Moreover, it protects cells against oxidative damage, acts in the stabilization of membranes, and inhibits the enzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NADPH-Oxidase). NADPH oxidase constitutes a family of enzymes whose function is to catalyze the transfer of electrons to O2 generating superoxide or H2O2 using NADPH as an electron donor (Faisal et al. 2021).

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) represents a frequent cause of acute kidney injury and is characterized by the presence of inflammatory infiltrates and edema within the interstitium, usually associated with an acute deterioration in renal function (Jung et al. 2004). Renal involvement in parasitic infections is polymorphic, ranging from direct invasion to various types of glomerulonephritis. AIN as a form of hypersensitivity reaction is an uncommon manifestation in the setting of human and animal parasitosis (De Pascalis and Buongiorno 2011). The current study showed that P. equorum-infected rats have serious histopathological abnormalities in the renal tissue, including degeneration and necrosis with the accumulation of renal casts in the tubular lumen. The interstitium tissue showed mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrates in the renal cortex and medulla. Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) transcription factors are evolutionarily conserved, coordinating regulators of immune and inflammatory responses (Tornatore et al. 2012). NF-kB plays a critical role in mediating responses to a remarkable diversity of external stimuli. Consequently, it is a pivotal element in multiple physiological and pathological processes and a powerful orchestrator of the immune response (Alhusseiny and El-Beshbishi 2021). There are many reports in the literature regarding the role of NF-kB during specific parasite infections. During helminth infections, it may be utilized as an inductor of a protective regulatory response (Bąska and Norbury 2022).

Conclusion

Administration of ZnO NPs improves renal function markers (creatinine, urea, and uric acid) and refines renal histopathological changes in P. equorum-infected rats, which confirmed that anthelmintic drugs such as ZnO NPs have ameliorative effects on parasite-induced kidney function impairment. The treatment with ZnO NPs in the current study improved oxidative stress status by decreasing MDA and NO levels and increasing antioxidant markers such as GSH content and GST and CAT activities in P. equorum infected rats, indicating that ZnO NPs can act through many antioxidant mechanisms, including the scavenging of active oxygen radicals and inhibition of lipid peroxidation. ZnO NPs were recommended as a potential alternative anthelmintic agent in parasitic infections.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by SBA, ASM and SRF. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ME-G and FA-G. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There was no outside funding or grants received that assisted in this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the content of this article. All the datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethical consideration

The protocol used in this study was accepted by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Egypt (CUI/F/85/20). The experimental procedures followed international guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

2/15/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s12639-024-01651-9

References

- Afifi M, Almaghrabi OA, Kadasa NM. Ameliorative effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on antioxidants and sperm characteristics in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat testes. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:1. doi: 10.1155/2015/153573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alajmi RA, et al. Anti-toxoplasma activity of silver nanoparticles green synthesized with Phoenix dactylifera and Ziziphus spina-christi extracts which inhibits inflammation through liver regulation of cytokines in Balb/c mice. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(5):BSR20190379. doi: 10.1042/BSR20190379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhusseiny S, El-Beshbishi S. Nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathways and parasitic Infections: an overview. Parasitol United J. 2021 doi: 10.21608/puj.2021.91389.1129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong SK, Woodgate RG, Gough S, Heller J, Sangster NC, Hughes KJ. The efficacy of ivermectin, pyrantel and fenbendazole against Parascaris equorum infection in foals on farms in Australia. Vet Parasitol. 2014;205(3–4):575–580. doi: 10.1016/J.VETPAR.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bąska P, Norbury LJ. The role of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in the immune response against parasites. Pathogens. 2022;11(3):310. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11030310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft JD, Stevens A (1996) Theory and practice of histological techniques. Churchill Levingstone

- Bauomy AA. Zinc oxide nanoparticles and l-carnitine effects on neuro-schistosomiasis mansoni induced in mice. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020;27(15):18699. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-08356-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayoumy AMS, Hamza HT, Alotabi MA. Histopathological and biochemical studies on immunocompetent and immunocompromised Hymenolepis nana infected mice treated with Commiphora molmol (Mirazid) J Parasit Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12639-020-01263-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benerji V, Babu F, Kumari R, Saha A. Comparative study of ALT, AST, GGT and uric acid levels in liver diseases. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2013 doi: 10.9790/0853-0757275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bildik A, Kargin F, Seryek K, Pasa S, Özensoy S. Oxidative stress and non-enzymatic antioxidative status in dogs with visceral Leishmaniasis. Res Vet Sci. 2004;77(1):63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinedu E, Arome D, Ameh FS. A new method for determining acute toxicity in animal models. Toxicol Int. 2013;20:224–226. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.121674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DdoN M, Cruz KJC, Morais JBS, Beserra JB, Severo JS, de Soares AR. Zinc and oxidative stress: current mechanisms. Antioxidants. 2017 doi: 10.3390/antiox6020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pascalis A, Buongiorno E. Acute interstitial Nephritis, a rare complication of giardiasis. Clin Pract. 2011 doi: 10.4081/cp.2012.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deger S, Deger Y, Bicek K, Ozdal N, Gul A. Status of lipid peroxidation, antioxidants, and oxidation products of nitric oxide in equine babesiosis: status of antioxidant and oxidant in equine babesiosis. J Equine Vet Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2009.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dkhil MA, Khalil MF, Diab MSM, Bauomy AA, Al-Quraishy S. Effect of gold nanoparticles on mice splenomegaly induced by schistosomiasis mansoni. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos SV, et al. Migration pattern of Toxocara canis larvae in experimentally infected male and female Rattus norvegicus. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2017;50(5):698–700. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0076-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmeligy E, et al. Oxidative stress in Strongylus spp. infected donkeys treated with piperazine citrate versus doramectin. Open Vet J. 2021 doi: 10.5455/OVJ.2021.v11.i2.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza E, Muro A, Sánchez Martín MM, Casanueva P, Pérez-Arellano JL. Toxocara canis antigens stimulate the production of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 by rat alveolar macrophages. Parasite Immunol. 2002;24(6):311–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2002.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal S, et al. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles using aqueous fruit extracts of Myristica fragrans: their characterizations and biological and environmental applications. ACS Omega. 2021;6(14):9709–9722. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta VK, Siddiqui NJ, Sharma B. Ameliorative impact of Aloe vera on Cartap mediated toxicity in the brain of Wistar rats. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12291-020-00934-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijaz M. Prevalence, hematology and chemotherapy of gastrointestinal helminths in camels. Pak Vet J. 2018 doi: 10.29261/pakvetj/2018.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung O, Ditting T, Gröne HJ, Geiger H, Hauser IA. Acute interstitial nephritis in a case of Ascaris lumbricoides infection. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimzadeh MR, Soltanian S, Sheikhbahaei M, Mohamadi N. Characterization and biological activities of synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using the extract of Acantholimon serotinum. Green Process Synth. 2020;9(1):722–733. doi: 10.1515/gps-2020-0058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil HMA, et al. Ashwagandha-loaded nanocapsules improved the behavioral alterations, and blocked MAPK and induced Nrf2 signaling pathways in a hepatic encephalopathy rat model. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2023;13(1):252–274. doi: 10.1007/s13346-022-01181-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatami M, et al. Greener synthesis of rod shaped zinc oxide NPs using Lilium ledebourii tuber and evaluation of their leishmanicidal activity. Iran J Biotechnol. 2020;18(1):1–5. doi: 10.30498/ijb.2020.119481.2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziejczyk L, Siemieniuk E, Skrzydlewska E. Fasciola hepatica: effects on the antioxidative properties and lipid peroxidation of rat serum. Exp Parasitol. 2006;113(1):43. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadappa P, Dey S. Effects of Toxocara canis Infection and albendazole treatment on oxidative/nitrosative stress and trace element status in dogs. Int J Livest Res. 2018 doi: 10.5455/ijlr.20170720111145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moawad M, Amin M, Hafez E. Role of ionizing radiation on controlling kidney changes in experimental infection with Toxocara canis. Assiut Vet Med J. 2015;61(147):87–94. doi: 10.21608/avmj.2015.170240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morsy K, Fahmy S, Mohamed A, Ali S, El-Garhy M, Shazly M. Optimizing and evaluating the antihelminthic activity of the biocompatible zinc oxide nanoparticles against the ascaridid nematode, Parascaris equorum in vitro. Acta Parasitol. 2019 doi: 10.2478/s11686-019-00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalule AS, Mbaria JM, Kimenju JW (2013) In vitro anthelmintic potential and phytochemical composition of ethanolic and water crude extracts of Euphorbia heterophylla Linn. J Med Plants Res 7(43): 3202–3210

- Prabhu S, Patharkar SA, Patil NJ, Nerurkar AV, Shinde UR, Shinde KU. Study of malondialdehyde level and glutathione peroxidase activity in patients suffering from malaria. J Pharm Res Int. 2021 doi: 10.9734/jpri/2021/v33i26a31469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prastowo J, Sahara A, Marganingsih C, Ariyadi B. Identification of renal parasite and its blood urea-creatinine profile on the Indonesian indigenous pigeons. Int J Poult Sci. 2014 doi: 10.3923/ijps.2014.385.389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ray PD, Huang BW, Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24(5):981. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma K, Saravanan M, Mondal DB, De UK, Kumar M. Influence of natural Infection of Toxocara vitulorum on markers of oxidative stress in Indian buffalo calves. Indian J Anim Sci. 2012;82(10):1142. doi: 10.56093/ijans.v82i10.24280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scala A, et al. Parascaris spp. eggs in horses of Italy: a large-scale epidemiological analysis of the egg excretion and conditioning factors. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s13071-021-04747-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehata O, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of thymol against Toxocara vitulorum in experimentally infected rats. J Parasit Dis. 2022;46(2):454–465. doi: 10.1007/s12639-022-01465-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoeb M, Singh BR, Khan JA, Khan W, Singh BN, Singh HB, Naqvi AH. ROS-dependent anticandidal activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by using egg albumen as a biotemplate. Adv Nat Sci NanoSci NanoTechnol. 2013;4(3):035015. doi: 10.1088/2043-6262/4/3/035015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Wong M, Sun L, Li Y, Miyatake N, Sue HJ. Purification and stabilization of colloidal ZnO nanoparticles in methanol. J Solgel Sci Technol. 2007;43(2):237–243. doi: 10.1007/s10971-007-1569-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tornatore L, Thotakura AK, Bennett J, Moretti M, Franzoso G. The nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway: integrating metabolism with inflammation. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22(11):557. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg L, et al. Protective immunity elicited by the nematode-conserved as37 recombinant protein against ascaris suum Infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(2):e0008057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar TS, Mahboob S, Bupesh G, Vasanth S, Al-Ghanim KA, Al-Misned F, Govindarajan M. Facile synthesis and biophysical characterization of egg albumen-wrapped zinc oxide nanoparticles: a potential drug delivery vehicles for anticancer therapy. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;60:102015. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.102015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]