Abstract

Purpose: To evaluate the efficacy of intraoral drainage of isolated submandibular space abscess as a minimally invasive surgical technique compared to the standard trans-cervical approach. Patients and Methods: This prospective study included 40 subjects with isolated submandibular space abscesses. They were randomly divided into 2 equal groups: trans-cervical surgical drainage (group A) and intra-oral surgical drainage (group B). The included data were demographics, repeated surgery requirement, postsurgical hospitalization duration, formation of scar, and complications. Results: Intraoral drainage (Group B) reduced the mean operative time by 15.25 min (P < 0.001) compared with trans-cervical incision (Group A). No considerable difference was found between the 2 groups in regarding hospitalization postoperatively. No weakness in marginal mandibular nerve was found in both groups. Three patients only have a cervical scar in a group (B) who required external drainage due to recollection. No recurrence was detected in a group (A). Conclusion: The current study demonstrated that isolated submandibular abscesses can be successfully managed with an intraoral drainage modality, and it is a better option than the trans-cervical approach regarding better cosmetic outcome and shorter operative time.

Keywords: Submandibular space, External approach, Intraoral, Abscesses

Introduction

The fascial spaces of the neck are sites of loose connective tissue occupying the areas between the superficial, middle, and deep layers of deep cervical fascia [1].

The submandibular space is surrounded inferiorly by the deep cervical fascia superficial layer that extends from the hyoid to the mandible, supero-laterally by the medial surface of the mandible below the mylohyoid ridge, antero-medially by the mouth mucosa and mylohyoid muscle, postero-medially by the floor of the mouth and hyoglossus muscle, antero-superiorly by the anterior belly of diagastric muscle, postero-superiorly by the posterior belly of diagastric muscle, stylohyoid and the stylopharyngeous muscle, and laterally by skin and platysma [2].

The submandibular space communicates medially and anteriorly to the submental space. Also, it communicates posteriorly and superiorly to the sublingual space around the mylohyoid muscle or through a defect in the mid-portion of the muscle (boutonnière defect) [3].

Moreover, it communicates inferiorly to the parapharyngeal space. As the submandibular space fills, the infection passes through the buccopharyngeal space to the parapharyngeal space, which then communicates with the mediastinum, permitting the spread of infection from the neck’superior part into the deeper neck spaces resulting in mediastinitis [4, 5].

There is no midline fascia dividing the two sides of the submandibular space (SMS). Lesion growth in SMS is therefore unhindered from side to side. The inclusion of bilateral neck spaces along with the submental space permits the spread of infection across the floor of the mouth and neck contributing to the clinical manifestation of Ludwig’s angina [6].

Patients with submandibular space infections may exhibit a range of symptoms, from relatively minor to extremely dangerous. A quick assessment of the situation is necessary. If the patient is toxic and exhibits central nervous system changes and airway compromise, then immediate hospitalization, airway protection, aggressive medical treatment, and aggressive surgical intervention (including extraction of the offending tooth or teeth, incision and drainage, or a combination of both) should be carried out [7].Incision and drainage with an external cervical approach is the cornerstone of managing submandibular space abscesses followed by broad-spectrum antibiotics [8]. Recently, intraoral drainage of such abscess has been adopted by some surgeons, since it is a minimally invasive technique with fewer postoperative morbidities [9]. In this study, a comparison between routine external cervical approach and intraoral drainage of the submandibular space abscess was performed.

Patients & Methods

This prospective observational study was performed on Forty patients who presented with submandibular space abscesses at a tertiary care institution, from the period of November 2020 to June 2022. All procedures were following the ethical criteria of the institutional research committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Approval was obtained from the institutional review board (permit number MD-16-2021).

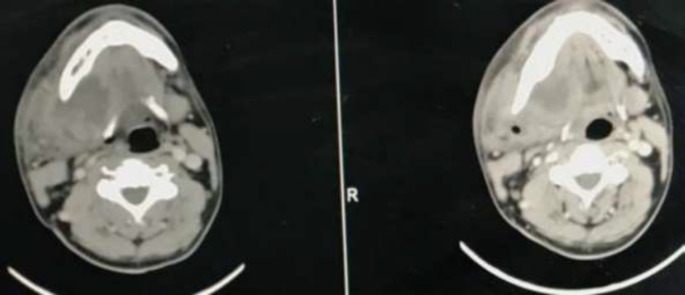

Patients presented with well-defined, unilocular submandibular space abscesses with pus appearing during aspiration and fluid collection in contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) more than 1 cm and less than 5 cm in the greatest dimension were included in this study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CECT scan of the neck shows the right submandibular abscess

Patients with extensive fascial space infections (more than two anatomical sites), Patients with either medical co-morbidities, simultaneous Ludwig’s angina, Pregnant, or any underlying condition had more than a moderate risk of general anaesthesia, Patients with evidence of compromised airway and patients refused to participate at the study were excluded.

All study participants were submitted on admission to clinical examination and laboratory tests. A neck and chest contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) was done to locate the potential focus of infection and to evaluate the extension of the suppurative process.

All medical records were reviewed for demographic characteristics, source of infection, the largest diameter of the abscess, length of hospital stay, medical treatment, type of surgical drainage (intra-oral or trans-cervical approach), operative time (the time between the start of the surgery and the finish of surgery excluding room and anaesthesia times) and postoperative complications.

Treatment Regimens

Forty patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were involved in this prospective study and were operated upon between November 2020 and June 2022.

Patients were randomised using a computer-generated table into two equal groups. These two categories involved patients treated with trans-cervical drainage of submandibular space abscess (Group A) and Intra-oral drainage of submandibular space abscess (Group B).

All surgeries were done under general anaesthesia. The patient was in the supine position with a shoulder roll placed to gently extend the neck. A head ring was placed to stabilise the head of the patient. The head was carefully turned to the contralateral side. The location of surgeon was on the right side of the operating table and may move to the head side of the operating table in case of intraoral drainage (Group B) for better visualisation.

Trans-cervical Approach (Group A) (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

(a) Skin incision site marked 2 fingers below mandible; (b) Skin incision; (c) dividing platysma; (d) Rubber drain inserted after trans-cervical I&D of the left submandibular abscess

Using a #15 blade, the skin incision was made with 2–3 cm of extension, according to Topazian and Goldberg criteria [10], affecting healthy skin, in a natural skin crease and in the most dependent area to allow for gravitational drainage.

The skin incision was made at the level of the hyoid bone, 2 finger-breadth below the mandible inferior border. The subcutaneous tissues and the platysma were then sharply incised. The superficial cervical fascia was cut in parallel to the mandible inferior border. The dissection was advanced in a superior-medial direction to entirely drain the submandibular space.

A sterile needle tube was used for pus extraction for bacterial culture. Pus was absorbed by a suction device and necrotic tissue in the cavity was cleaned up. Flushing of the abscess cavity was done frequently with 0.9% saline solution, diluted iodophor solution or hydrogen peroxide until no further turbidity was noted.

A corrugated rubber drain was placed in a dependent position in the abscess cavity and secured with a suture to facilitate dependent drainage. The platysma layer was partially closed with interrupted 3 − 0 vicryl, buried suture and the skin was partially closed, leaving an opened portion for the drain, in a simple interrupted manner with either 5 − 0 fast-absorb sutures or 5 − 0 prolene for paediatrics and adults, respectively. A “ghost” stitch may be placed where the drain exits to reapproximate the skin once the drain is removed.

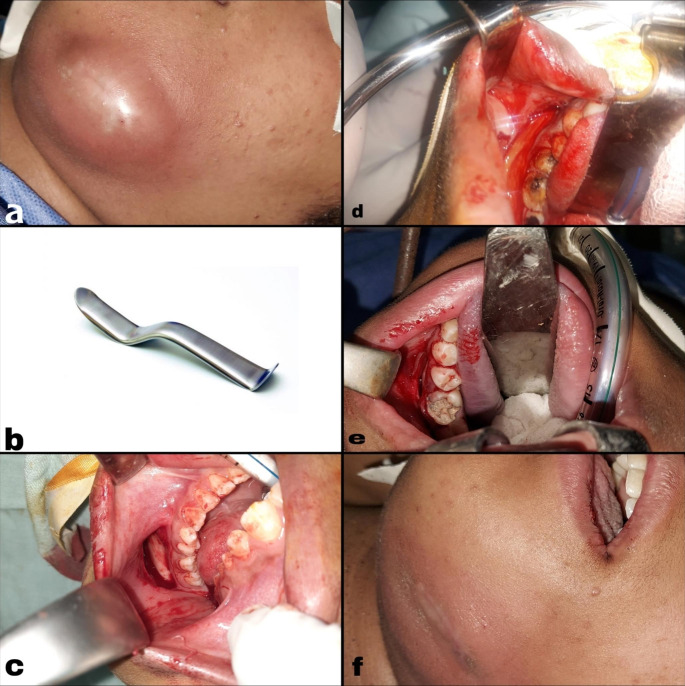

Intra-oral Approach (Group B) (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

(a) Preoperative view of left submandibular abscess; (b) Minnesota cheek retractor; (c) Site of intra-oral incision; (d) Intra-oral drainage of the pus; (e) The incision remains open to allow further drainage; (f) Submandibular area after drainage

An appropriately sized Boyle-Davis mouth gag was placed and suspended with Draffin’s bipod stand to displace the tongue and endotracheal tube inferiorly. Minnesota cheek retractor, plastic lip-cheek retractor or Langenbeck retractor was essentially used to keep the soft tissues away from the teeth and allow easy viewing of the inferior gingivo-buccal sulcus. The use of a throat pack was discouraged to eliminate the potential for a retained/airway foreign body. Using a #15 scalpel blade, an incision was performed laterally to the mandible in the inferior gingivo-buccal sulcus next to the second premolar tooth and extended posteriorly (to preserve the mental nerve). Then the incision was advanced to the periosteum of the mandible which was then elevated to the level of the mandible using a periosteal elevator. The mucogingival full-thickness flap was elevated. The submandibular space was accessed by tilting the instrument toward the medial side. The surgeon’s fingers performed a blunt dissection till the abscess was entirely drained. Once purulent exudate was detected, specimens were gathered for bacterial cultures. The cavity was flushed frequently with 0.9% saline solution, or diluted iodophor solution until no further turbidity was noted. If there was bleeding, gauze soaked in adrenaline 1 in 1,000 (1 mg/mL) can be applied in the submandibular space. The incision remained open to allow further drainage with no drain inserted and the patient was awakened from anaesthesia. Then, a balled-up sterile bandage should be placed at the submandibular region.

Postoperative care

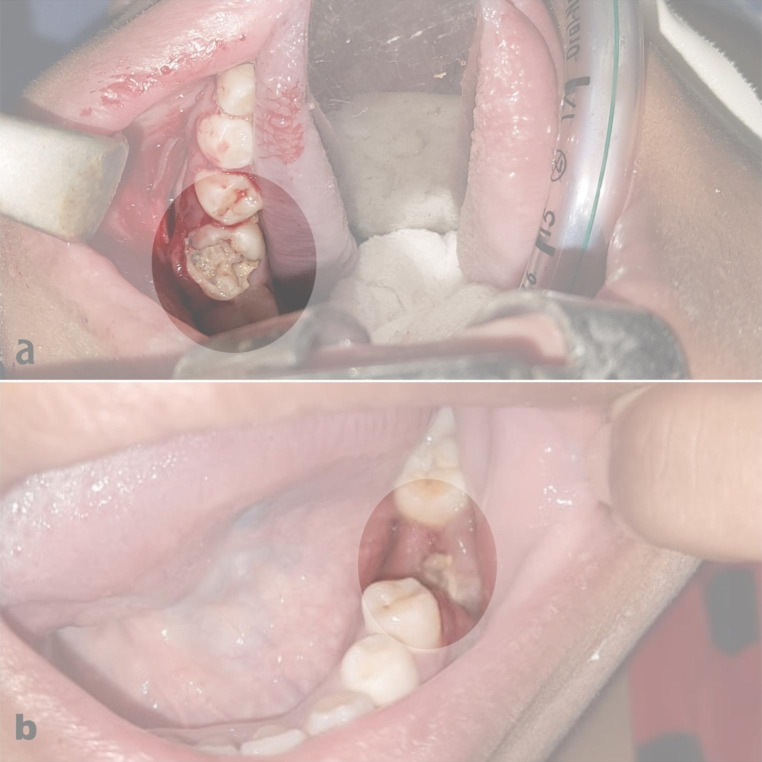

All patients with proven dental infection as the source of submandibular abscesses were sent to the dental care department for dental management (Fig. 4). All patients were admitted on intravenous antibiotics, including Ampicillin / Sulbactam in a dose of 1500 mg / 6 h and metronidazole in a dose of 500 mg / 8 h and once culture results were obtained, antibiotic therapy can be tailored according to the culture sensitivity and antibiogram.

Fig. 4.

(a) 1st lower molar dental caries as the source of infection; (b) Postoperative dental extraction

Regarding group (A), The drain was maintained until drainage decreased and then slowly backed out of the wound over days. Drains are maintained until drainage decreases and then are slowly backed out of the wound. Wounds are allowed to close by secondary intention.

Regarding group (B), mouthwash with chlorhexidine (1.25/ml) was prescribed. The patients were discharged after tolerating oral intake.

All patients were discharged on broad-spectrum antibiotics for 7 days. All patients fulfilled follow-up visits every 2 weeks for the first month, then after 3 months.

Data Analysis

Data were entered, coded and processed using the SPSS program version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative data were summarised using minimum, maximum, median, mean, and standard deviation, whereas number and relative frequency summarised qualitative data. Quantitative variables‘comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney and non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests. The Chi-square (χ2) compared between categorical data. An exact test was used instead when the expected frequency is less than 5. Correlations between quantitative variables were done using the Spearman correlation coefficient. P-values ˂0.05 were considered significant.

Results

In the Forty Patients constituting our cohort, age range was 10–67 years with a mean age of 29.65 ± 14.96 in a group (A) while in group (B) ages ranged between 16 and 34 with a mean age of 24.55 ± 7.41. Eighteen patients were males (45%) while twenty-two patients were females (55%). The differences in age and gender between the two categories were statistically insignificant (P = 0.414, P = 0.057, respectively).

In group A, all cases had a dental infection as the source of infection, while in group B, 18 cases had a dental infection as the source of infection, one case had submandibular lymphadenitis, and one case had an unspecified source of infection. No significant variation was found between the two groups with a P value of 0.48.

Only 30% of cases in group (A) showed bacterial growth compared to 55% in the group (B). Bacteria cultured showed many types including MRSA, proteus, alpha haemolytic streptococci, non-haemolytic streptococci, enterococci, and klebsiella with no considerable difference between the groups with P value (0.11).

Duration of surgery in the group (A) ranged between 20 and 60 min with a mean of 37.25 ± 9.93 while in group (B) duration range was 15 to 30 min with a mean duration of surgery of 22 ± 6.37 with a considerable difference between both groups with P value (< 0.001).

In group (A), no patients required revision surgery while in group (B), 3 patients showed recollection and underwent external drainage with no considerable difference between the groups with a P value of 0.231.

All patients in the external group had skin scars due to incision and drain placement in the wound, but no one in intraorally drained abscesses experienced such scars. Also, only three patients in group (B) had scars due to revision surgery with a marked significant difference between both categories with a P value < 0.001.

In group (A), days of hospital stay ranged from 4 to 8 days with mean hospitalization days of 5.6 ± 1.31. In group (B), hospitalization days ranged from 2 to 14 days with mean hospitalization days of 5.15 ± 3.25 with no considerable variation between both groups with a P value of 0.063.

In both groups, no affection of marginal mandibular nerve was noted with no statistically significant difference between both groups with a P value of 0.487.

Patients that needed revision surgery had mean hospitalization days of 9.33 while those who didn’t need revision surgery showed mean hospitalization days of 5.05 with a significant variation between both groups with a P value (0.014).

Discussion

Deep neck space infections typically include the submandibular space. Submandibular space abscesses are often treated with open surgical incision and drainage [11].

Recently, well-defined, unilocular submandibular abscesses have been treated with minimally invasive procedures in individuals who do not have compromised airways [9].

This study enrolled 40 patients with unilateral submandibular space abscesses. They were randomly divided into 2 equal groups. Twenty patients underwent classic trans-cervical surgical drainage (group A), while the other 20 patients underwent minimally invasive intra-oral surgical drainage (group B).

The male predominance of deep neck space infections (DNSI) patients has been recognised in many studies [1, 12, 13]. The distribution of 55% females in this study does not correspond with the majority of reviewed studies.

The most common aetiology in this study was odontogenic source (95%). The majority of previous studies highlighted the odontogenic factor as a primary origin of DNSI [14–16].

Regarding microbiology, out of 40 cases, only 17 cases showed bacterial growth on culturing the pus aspirate while 23 cases showed no bacterial growth. The spectrum of bacteria cultured involved 5 cases of Enterococci, 4 cases of alpha-haemolytic streptococci, 3 cases of mixed organisms (2 cases of MRSA & alpha haemolytic streptococci; one case of Klebsiella & non haemolytic streptococci), 2 cases of non-haemolytic streptococci, 2 cases of MRSA, and one case of Proteus Mirabilis. Patients‘distribution was according to microbiology in both groups is not significant (p = 0.11).

Several studies report consistently that Streptococcus, Staphylococcus and Enterococcus were the most common isolated pathogens in fascial space infections [17–20].

A close search of our findings demonstrates a significant variation between the two groups regarding operative time and scar formation (P < 0.001, each).

Intraoral drainage (Group B) reduced the mean operative time by 15.25 min (P < 0.001) compared with trans-cervical incision (Group A). Reducing operational time by 15 min per case results in a considerable decrease in health care delivery costs. Patients with submandibular space abscesses may experience associated comorbidities, which may elevate anaesthesia risk. Hence, one can easily appreciate the value of decreasing the operative time.

These results are reinforced by the findings of Amar and Manoukian and Choi et al. in their research of parapharyngeal abscesses which were successfully drained through an intraoral approach with shorter operative time than an external approach [8, 21].

Another benefit of the intraoral modality is the lack of a skin incision that can result in hypertrophic scars or keloids. Additionally, the risk of marginal mandibular nerve injury is eliminated. In this study, all patients who performed transcervical drainage had postoperative scars due to skin incision and drain placement. Only 3 patients of the intra-oral group had cervical scars due to recollection that necessitated revision external cervical drainage (P < 0.001).

The abscess recollection may be due to insufficient drainage in the primary procedure or postoperative recurrence. We believe that the postoperative recurrence in group (B) is due to a lack of gravitational drainage.

Similarly, in 2012, Mohamadi Ardehali and his colleagues conducted the first randomised controlled study to report the intra-oral approach for submandibular abscess drainage with no postoperative scar and abscess recurrence in the enrolled patients of their study [9].

Patients who underwent trans-cervical drainage stayed longer at the hospital with mean hospitalization days of 5.6 compared to those who underwent intra-oral drainage who had mean hospital stay days of 5.15. The marked variation between the 2 groups regarding the length of hospital stay was not identified (P = 0.063), these results attributed to the need for revision surgery in 3 patients who underwent an intra-oral approach.

Although the differences between the 2 groups regarding the need for revision surgery did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.231), Patients who underwent revision surgery stayed longer at the hospital with mean hospitalization days of 9.33 compared to those who were drained successfully from the first time.

In 2012, Mohamadi Ardehali and his team compared the external cervical modality with their novel minimally invasive approach of intraoral drainage for submandibular space abscesses. The patients needed an average of 5.5 and 5.4 days of hospital stay in the intraoral and external techniques, respectively. Although no chronic or recurrence of the abscess was detected in either group, considerable variation between the 2 groups regarding postoperative hospitalization could not be established in their study [9].

Furthermore, Galli and his colleagues conducted the minimally invasive intra-oral approach (MIIA) for 16 patients suffering from the submandibular abscess and noted that the patients who performed the MIIA surgery did not complain relapses during the follow-up. Additionally, MIIA can reduce the impact of the surgery, and as a result reduces the duration of hospitalization and health costs [22].

A few complications can occur due to intraoral drainage including vestibular sulcus blunting, fistula formation, early commencement of oral intake difficulties, injury to the mental nerve; however, none experienced by our patients.

Furthermore, the intraoral modality did not cause any vascular injuries. The efficacy and safety of similar procedures in parapharyngeal abscesses were also confirmed by Choi and his team in their studies [21].

Although no affection of marginal mandibular nerve was noted in both groups in our study (P = 0.487), Mohamadi Ardehali and his colleagues reported that 3 patients who performed the external modality suffered from marginal mandibular nerve palsy, that did not occur in the intraoral approach due to the nature of the modality [9].

The study limitations were firstly in its small sample size; this is attributed to the strict exclusion criteria as the majority of DNSI patients have multiple space involvements making them poor candidates for the new intraoral surgical technique. Furthermore, blinding was not possible. This may have incorporated patient and physician bias regarding discharge. So, studies including larger sample sizes may be needed to enforce our results and address these limitations.

The major strength is that this study was conducted prospectively. Moreover, it reports an appropriate number of patients who underwent a novel minimally invasive approach to drain the submandibular space abscess compared to other studies that addressed the same approach [22].

This study acknowledged that, in selected cases, intraoral drainage provides numerous benefits over the external approach.

Conclusion

The cornerstone of submandibular space abscesses management is open surgical incision and drainage.

This study demonstrates that isolated submandibular abscesses in chosen patients can be successfully managed with an intraoral drainage technique, which is a better option than the trans-cervical approach regarding cosmetic outcomes and shorter operative time.

Some of the advantages of the intra-oral approach are as follows: excellent healing rates; avoidance of injury to nerves and vessels in sensitive conditions; a shorter postoperative recovery; and a reduction in the length of hospitalization. But further studies are needed to draw a firm conclusion.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author Contribution

A A. N; made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the manuscript, data collection, drafted and revised the manuscript.

H O. I; designed the work and acquired data.

A.A.& M.H.; made substantial contributions to the data collection.

M A. A; made substantial contributions to the data collection and gave final approval of the manuscript version to be published.

All authors approve and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research did not receive any special grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study had already been included in this manuscript. Patient’s case file was retrieved from the medical record section of the institution. The clinical data had been collected from the prospectively maintained computerized database and the case file. The follow-up status was updated from the above-mentioned manner.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate: All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and / or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This Study was approved by the institutional review board (permit number MD-16-2021).

Consent for Publication

Written informed consent to publish the patient’s clinical details information was obtained from the study participant.

Competing Interests

None to declare.

This study was conducted using the available resources at Cairo University Hospitals.

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

No author identifying information is present anywhere in the blinded manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Velhonoja J, Lääveri M, Soukka T, Irjala H, Kinnunen I. Deep neck space infections: an upward trend and changing characteristics. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(3):863–872. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05742-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadig K, Taylor NG. Management of odontogenic infection at a district general hospital. Br Dent J. 2018;224(12):962–966. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaughran GR. Mylohyoid boutonniere and sublingual bouton. J Anat. 1963;97(Pt 4):565–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grodinsky M, Holyoke EA. The fasciae and fascial spaces of the head, neck and adjacent regions. Am J Anat. 1938;63(3):367–408. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000630303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paonessa DF, Goldstein JC. Anatomy and physiology of head and neck infections (with emphasis on the fascia of the face and neck) Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1976;9(3):561–580. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(20)32663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boscolo-Rizzo P, Da Mosto MC. Submandibular space infection: a potentially lethal infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(3):327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridder GJ, Technau-Ihling K, Sander A, Boedeker CC. Spectrum and management of deep neck space infections: an 8-year experience of 234 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(5):709–714. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amar YG, Manoukian JJ. Intraoral drainage: recommended as the initial approach for the treatment of parapharyngeal abscesses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(6):676–680. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ardehali MM, Jafari M, Hagh AB. Submandibular space abscess: a clinical trial for testing a new technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(5):716–718. doi: 10.1177/0194599811434381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR. Oral and maxillofacial infections. 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ALMEIDA LM. CUNHA KS, DA COSTA KA, ACCETTA A, ACCETTA R, JUNIOR AS, MILAGRES A. MULTIDISCIPLINARY TREATMENT IN LUDWIG’S ANGINA Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020;130(3):e234–e235. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2020.04.591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rega AJ, Aziz SR, Ziccardi VB. Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivities of head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(9):1377–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jevon P, Abdelrahman A, Pigadas N. Management of odontogenic infections and sepsis: an update. Br Dent J. 2020;229(6):363–370. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-2114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vytla S, Gebauer D. Clinical guideline for the management of odontogenic infections in the tertiary setting. Aust Dent J. 2017;62(4):464–470. doi: 10.1111/adj.12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kataria G, Saxena A, Bhagat S, Singh B, Kaur M, Kaur G. Deep neck space infections: a study of 76 cases. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;27(81):293–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammad Y, Neal TW, Schlieve T. Admission C-reactive protein, WBC count, glucose, and body temperature in severe odontogenic infections: a retrospective study using severity scores. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2022;133(6):639–642. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2021.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamiri B, Hashemi SB, Hashemi SH, Rafiee Z, Ehsani S. Prevalence of Odontogenic Deep Head and Neck Spaces infection and its correlation with length of Hospital Stay. J Dent. 2012;13(1):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tent PA, Juncar RI, Onisor F, Bran S, Harangus A, Juncar M. The pathogenic microbial flora and its antibiotic susceptibility pattern in odontogenic infections. Drug Metab Rev. 2019;51(3):340–355. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2019.1602630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beka D, Lachanas VA, Doumas S, Xytsas S, Kanatas A, Petinaki E, et al. Microorganisms involved in deep neck infection (DNIs) in Greece: detection, identification and susceptibility to antimicrobials. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):850. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4476-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen SL, Young CK, Tsai TY, Chien HT, Kang CJ, Liao CT, et al. Factors affecting the necessity of tracheostomy in patients with deep neck infection. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11(9):1536. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11091536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SS, Vezina LG, Grundfast KM. Relative incidence and alternative approaches for surgical drainage of different types of deep neck abscesses in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123(12):1271–1275. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900120015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galli M, Fusconi M, Federici FR, Candelori F, De Vincentiis M, Polimeni A, et al. Minimally invasive intraoral approach to submandibular lodge. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):2971. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study had already been included in this manuscript. Patient’s case file was retrieved from the medical record section of the institution. The clinical data had been collected from the prospectively maintained computerized database and the case file. The follow-up status was updated from the above-mentioned manner.